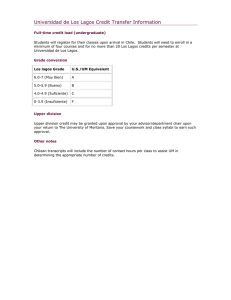

Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (LAMATA) Draft for use in the Leaders in Urban Transport Planning (LUTP) Program In the summer of 2011 officials in the Nigerian state of Kano were considering establishing a metropolitan area transportation authority modeled after LAMATA, the Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority. Cities all over the developing world were struggling with increasing traffic congestion caused by a combination of rapid urban population growth and a steady shift by urban passengers from walking or riding public transportation to driving private motorcycles and cars. The cities seemed to be losing their battle in part because they lacked institutions that had the authority and the capacity to promote public transportation in an integrated fashion. Responsibilities for public transportation were typically shared by local, provincial, and national levels of government. At each level of government, moreover, different public agencies licensed and regulated bus operators; built and maintained the roads, bus lanes, terminals and other facilities they used; controlled the traffic lights and rules, and enforced those rules. In addition, the staffs of these agencies were typically paid modest salaries and, as a result, had little training and experience. Lagos was the only major city in Sub-Saharan Africa, and one of the few in the developing world, to have a metropolitan area public transportation authority with broad powers, independent resources and a staff of international quality. Held up as a model by the World Bank and others, LAMATA had scored some early victories by repairing the main roads used by Lagos’ public transport operators and building a popular bus rapid transit (BRT) system of exclusive bus lanes. But other agencies were expanding their roles, raising the question of how LAMATA’s success could be maintained and replicated. This case was written by Professor José A. Gómez-Ibáñez, Professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy at Harvard University. It is intended for classroom use only and not as a primary source of information about the Lagos Metropolitan Area Transportation Authority (LAMATA). The preparation of this case was supported in part by the World Bank and the author is grateful for the cooperation of officials from LAMATA and other Nigerian transport agencies. The case does not necessarily reflect the views of either the World Bank, LAMATA or any of the other agencies consulted. The author is solely responsible for the accuracy of the information in the case. (Revised December 18, 2011) Copyright © 2011 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. The World Bank’s Leaders in Urban Transport Planning (LUTP) Program has received permission to use this document in its workshops. No part of this publication may be reproduced, revised, translated, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without further written permission of the Case Program. For orders and copyright permission information, please visit our website at www.ksgcase.harvard.edu or send a written request to Case Program, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 79 John F. Kennedy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. 1 The Origins of LAMATA Lagos is the commercial capital and largest city in Nigeria with a metropolitan area population of 15 million growing at 6 percent per year. Most of the population lives within Lagos State, one of the country’s 36 states. Nigeria’s economy has been highly dependent on oil exports ever since the mid-1970s when an oil price boom encouraged the country to neglect its agriculture and light manufacturing base. Heavy-handed state intervention in the economy, neglect of infrastructure, political instability and a strong reputation for corruption further discouraged nonpetroleum investment during the 1980s and 1990s. Prospects have improved since the restoration of democratic rule in 1999, but progress in diversifying the economy and reducing corruption has been slow so that in 2010 Nigeria’s per capita income was only US$ 2,748, falling behind neighboring Ghana at US$ 10,748 and Cameroon at US$ 10,758. Lagos is extremely congested thanks to its rapid population growth, decades of under investment and under maintenance in its road system, and its informal and chaotic public transportation system. The formal public transportation system began to decline in the early 1970s, after the owners of the city’s private bus company sold it to the Lagos State government. The now-defunct State bus company soon began to operate at a loss, which made it hard for the government to expand services as the city grew. The vacuum was filled by private yellow minibuses carrying 12-14 passengers called danfos and medium size buses for 20 to 25 passengers called molues. Minibuses soon became the most important mode of transport in Lagos, eclipsing even walking. Studies suggested that in 2008 Lagos residents made 17.5 million trips on a typical weekday of which 7.6 million (42 percent) were by bus, 7 million (40 percent) by walking, 2 million (11 percent) by car and 1 million (5 percent) by motorcycle taxi.1 An estimated 83,000 minibuses plied the city’s streets, almost all danfos. While the minibuses were widely used, they were not widely liked. Many of their problems stemmed from the fact that most minibus owners had only one or two vehicles, so that in effect the city was served by thousands of independent minibus companies that competed aggressively for passengers. Two unions, one of drivers and one of owners, determined the minibus routes, assigned vehicles to them and exercised some control over the dispatching vehicles from the bus terminals at the ends of the routes. But aggressive driving was common, as buses raced each other to stops in search of passengers. And drivers would stop to pick up or drop off passengers in the middle of the road, blocking traffic. Fares were relatively high and passenger loads relatively low, in part because the unions had financial incentives to encourage membership. And the marginal profitability meant that the vehicles were typically decrepit and highly polluting.2 The World Bank had become concerned about growing congestion in Lagos and the state of the city’s buses in the 1980s, and funded the preparation of an urban transport plan that called for, among other things, improved public transportation overseen and coordinated by a metropolitan transportation authority modeled on those of many cities in developed countries. New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority planned and operated most of the subway, commuter rail and bus services for the region, for example, while London and Paris had similar agencies. The Bank withdrew from lending for Nigeria after the military staged a coup in 1984, but when civilian rule returned in 1999 the Bank reengaged with Nigeria and revived the old plan, including the idea of creating a metropolitan transportation authority. Launching LAMATA The World Bank proposal appealed to Lagos State Governor Bola Ahmed Tinubu, who had just won his post in the first elections after the end of military rule. Governor Tinubu, who would serve two four-year terms (from 1999 to 2007), came from a distinguished Lagosian family with a square near the city center named in its honor. Tinubu 1 The figures for bus include 315,000 passenger trips in conventional 13-meter buses operating on the Bus Rapid Transit system that opened that year. Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority, Strategic Transport Master Plan for the Lagos Metropolitan Area, December 2009, p. 35 2 The typical danfo was a Volkswagen van imported used from Europe. The original seating for 8 was ripped out and replaced with wooden benches seating 12 to 14. The side sliding door was often removed for easier boarding and alighting. 2 wanted to leave a legacy from his governorship and he targeted public transportation and solid waste collection and disposal, two city services that were in deplorable shape. In 2001 Governor Tinubu recruited Dayo Mobereola, a Nigerian-born transportation specialist working in Britain for British Petroleum, to become his special advisor on transportation and help draft the law creating LAMATA. The law was passed in 2002 and the authority launched the next year with Mobereola as its first managing director. That same year (check) the World Bank and the Lagos State government launched the Lagos Urban Transport Project (LUTP) providing more than $100 million in World Bank loans for capacity building at LAMATA, improvements on the main roads used by public transport and regulatory reforms for buses and ferries. LAMATA became the executing agency for LUTP and, as such, had to follow World Bank procurement rules. The 2002 law gave the LAMATA broad powers, some of which had been a condition of the World Bank loan. The Authority was to “coordinate and implement the transport policies, programs and actions of all transport related agencies in Lagos State.”3 The act identified a 635-kilometer network of “declared roads” that were used heavily by the public transportation system and gave LAMATA special authority and responsibility to manage, maintain and improve them. LAMATA was to be governed by a Board of Directors appointed by the Governor and reporting directly to him rather than to the Commissioner of Transport. (In Nigeria the head of a federal ministry is called a minister but the head of a state ministry is called a commissioner.) LAMATA’s Managing Director was the Board’s only full-time member but he was joined by 12 part-time members representing other relevant state ministries, transport operators, unions, the business community and the general public.4 LAMATA was not bound by civil service rules but had the flexibility to establish the employee pay scales and conditions of service it saw fit. LAMATA would use its flexibility in employee compensation to recruit a professional staff of international quality. The organization was lean given its responsibilities and activities, with a staff of only approximately 70 in 2011 of whom 25 were professionals with training in transportation planning or related fields. Appointments were made on merit rather than connections, and for the more senior positions the searches extended outside the country. Several key staff members were recruited from the Nigerian Diaspora, including the Director of Public Transport who had been planning and managing key public transport projects at Transport for London, one of the world’s most respected metropolitan transportation authorities. To attract such qualified staff LAMATA paid salaries that were comparable to the private sector in Nigeria and competitive internationally, which meant that professional staff members were often paid several times more than their counterparts in the Lagos State ministries. Early Achievements LAMATA realized that it would be helpful to have an “early win” to demonstrate the capabilities of the new agency. In the long run it was essential to reorganize the bus industry by replacing the minibuses with full-size, 13-meterlong buses that used street capacity more efficiently, by changing operator incentives so that they drove safely and provided more reliable service and by coordinating routes and fare collection to facilitate transfers among buses and between buses and other forms of public transportation. Negotiating and implementing such radical changes in the city’s bus system would take time, however, so LAMATA looked for other opportunities to more quickly demonstrate progress. Road Repairs. LAMATA decided to improve the quality of its declared road network first, even as it began to work on the longer-term problem of reorganizing the bus industry. The quality of the road surface greatly influenced bus speeds and vehicle maintenance costs. And Nigeria’s roads were often in terrible shape, in part because the federal and state ministries of works focused more on constructing new roads or major rebuilding of existing roads than on 3 As quoted in the 2007 revision of the law at section 6 of “A Law to Re-establish the Lagos Metropolitan Area Transportation Authority, Provide for the Management and Regulation of Transport and related Services and for Connected Matters”, Lagos State of Nigeria Official Gazette, vol. 40, no. 28 (April 16, 2007). 4 The part-time members included a chairman, two representatives of the operators; one each representing the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economic Planning and Budget, Ministry of Works, the Lagos Chamber of Commerce, and the state transport union plus two knowledgeable members of the general public. 3 routine maintenance. Some ministries used their own employees for construction, a practice that was usually slow and very costly. But when ministries contracted with private construction companies to do the work, their contract supervision was so poor or corrupt that the projects often dragged on for years or were never completed. By 2005 and 2006 LAMATA had rehabilitated some important segments of the declared network. It had to start with road segments that were part of the Lagos State road system since the Federal Ministry of Works was reluctant to cede much control over federal roads. The declared network included almost all of the most heavily-travelled roads in the metropolis, however, and the improvements were very noticeable and brought popular praise for Governor Tinubu and LAMATA. Moreover, LAMATA had brought the projects in at a cost one-fifth to one-third less than comparable projects supervised by the Lagos State Ministry of Works, an achievement that was noted by the Bank and other funders. There was some concern on LAMATA’s part, however, that the public might not understand that the Authority was responsible only for the declared network and not for conditions on the rest of the city’s roads. Bus Rapid Transit. The second major early achievement was the opening of Lagos’ first bus rapid transit (BRT) line in March 2008. LAMATA decided to experiment with bus reform in two corridors instead of trying to tackle the whole city at once. In one corridor the Authority would try a “pilot exclusive franchise” scheme in which the hundreds of minibus operators serving the corridor would be replaced by a single bus company operating full-size buses. The road surface would be improved and terminals at the ends of the corridor and stops along the way would be built. The second corridor also involved an exclusive franchise for big buses, new stops and terminals but had the added feature that the buses would operate in special lane for much of the length of the corridor. Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) had been pioneered in Curitiba, Brazil and Bogota, Colombia and involves operating a bus service something like a rail line so as to increase speeds and capacity. The heart of the BRT system is the use of exclusive bus lanes to protect the buses from traffic congestion. But many cities add measures to speed boarding such as fare payment at the station rather than on the vehicle, multiple doors on each bus and high station platforms that align with the bus floor. LAMATA would christen its BRT line as “BRT Lite” since it enjoyed exclusive lanes on only 65 percent of the 22kilometer corridor and had advance payment in the stations before boarding but few of the other refinements found in more elaborate schemes. LAMATA would work with the drivers’ union in the pilot exclusive bus corridor and the owners’ union in the pilot BRT corridor, but the two unions were essentially similar because many drivers were owners and vice versa.5 The BRT corridor advanced fastest, perhaps because the owners’ union had already persuaded Ashok Leyland, an Indian truck and bus manufacturer, to finance 100 new buses over 18 months. The union had planned to use the vehicles in intercity service, but it recognized the need to reform urban bus services and were persuaded of the opportunity posed by the corridor.6 In 2006 the World Bank took officials from state government and the unions on a study tour of BRT systems in Latin America. On their return LAMATA and the union worked out a scheme whereby the union organized a new company, the First BRT Cooperative of Nigeria (FBC), to lease the buses and operate them on the BRT corridor. They persuaded a private bank to finance the buses for 24 months by giving it the right to collect all the bus fares, deduct its leasing fee first, and return the balance to the company to pay its costs. 7 LAMATA , the 5 The drivers union was the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW) and the owners union was the Road Transport Employers’ Association of Nigeria. 6 The drivers’ union was supportive of BRT because it thought BRT would improve drivers’ lives. They expected employment not to decline despite the fact that the buses were larger because there would be two shorter daily shifts per bus rather than one longer shift. The job would improve, moreover, because shifts would be shorter, there would be less pressure to drive aggressively and the drivers would have greater job security and health and other benefits. The owners’ union supported BRT because it gave would persuade the banks to finance new vehicle purchases, something they had been reluctant to do before. 7 The bank (Ecobank) printed the bus tickets and sold them through agents at the stations who earned a 4.5 percent commission. A stub on the ticket was collected at the gate to the station and then the ticket its self was cancelled by the conductor on the bus. Inspectors made random checks to insure that all passengers had properly cancelled tickets. For a more complete description see Integrated Transport Planning Limited, “Evaluation and Documentation of Lagos BRT-Lite”, report prepared for LAMATA, April 2009, pp. 23-27. 4 bank and the union collectively negotiated a fare of 100 naira (US$ 0.67) to travel the length of the corridor and 50 naira for shorter trips. The BRT corridor opened in March 2008 and was much more successful than anyone had imagined. The compromises in the BRT Lite design reduced the costs of building the busway to US$ 1.7 million per kilometer, well below the US$ 5 or 10 million per kilometer typical of more elaborate schemes. But the scheme was sufficient to greatly speed the buses so that the ridership rose to 150,000 passengers per weekday when LAMATA had forecast only 60,000. FBC was forced to lease an extra 120 buses from Lagos State government and easily paid off the leases for the original 100 vehicles in 24 months as scheduled. The cooperative was not obliged to open its accounts to the government and wouldn’t, but it was rumored to be grossing 3 billion naira (US$ 20 million) a year, an extraordinary amount for a bus line. The BRT line was so successful that every corridor in the city began to clamor for one and the World Bank sent LAMATA and union officials to BRT workshops in other countries to explain the advantages of the simple BRT Lite design, the feasibility of bank finance and the leadership of the union in forming the operating company. LAMATA began working on plans for two additional BRT corridors. The Transport Fund. A final achievement during the early years was to amend LAMATA’s authorizing legislation in 2007 to provide it with a secure funding source. The World Bank funding for LAMATA under LUTP was scheduled to phase out soon and there was a gubernatorial election scheduled for 2007. Governors in Nigeria can serve only two terms so Tinubu could not stand for re-election in 2007. And while the new governor would almost certainly come from Tinubu’s party (the Action Congress of Nigeria, which dominated Lagos politics), there was no assurance that he would support LAMATA with the same enthusiasm. LAMATA persuaded the Governor Tinubu that 50 percent of the motor vehicle registration and license fees collected by the Motor Vehicle Agency, a dependency of the Ministry of Transport, should be deposited in a special Transport Fund that LAMATA could use for its expenses and projects. The Fund’s share of the fees amounted to US$ 5 to 6 million per year of which approximately US$ 2 million was needed for LAMATA’s normal administrative expenses and the rest could be used for projects. The 2007 election was won by Babatunde Raji Fashola, a lawyer who had begun his political career by serving as Governor Tinubu’s chief of staff in 2002. Governor Fashola came to office determined to make Lagos a model mega city for Africa by improving public services and encouraging more orderly urban development. In his first term, for example, he created the Lagos Water Corporation to alleviate the city’s shortage of clean water and cleared the informal markets that used to block the city’s streets. Although he was sometimes criticized for haste and impatience, his energy and commitment to reform earned him a landslide 81 percent of the vote in his 2011 reelection and the accolade as “a rare good man” from a distinguished international news magazine. 8 Supporters hoped that Fashola would run for Nigeria’s presidency when his second gubernatorial term was up in 2015, but the Governor dismissed such talk as premature. Relations with Other Agencies The Two Ministries. An on-going challenge for LAMATA was managing its relationships with the other agencies that had responsibilities in transportation, most obviously the Lagos State Ministries of Transport and of Works. In theory the Ministry of Transport was responsible for policy while LAMATA was responsible for planning, management and implementation, but the line between policy and planning was often hard to draw. And the Ministry of Works was traditionally responsible for building roads, but LAMATA had similar responsibilities, especially on the declared road network. The overlap could result in petty resentments. Officials at the Ministry of Transport were irked that LAMATA was invited to but never attended the Ministry’s monthly management meeting, for example, while LAMATA staff complained that Transport officials sometimes skipped inter-ministerial meetings it had called. Occasionally the overlaps with the two ministries led to more serious problems, however, as in the case of the pilot franchise bus corridor. In this major east-west corridor LAMATA and the Ministry worked with the drivers’ rather than the owners’ union, but they came to an essentially similar arrangement. The union formed a cooperative (the 8 “Nigeria’s Business Capital: A Rare Good Man”, The Economist, May 7, 2001, p. 55. 5 Ebenezar Cooperative Society) that leased 100 Ashok-Leyland buses from another bank9 on a 24-month term by giving the bank the first lien on the revenues. In this corridor, however, the Ministry of Works insisted that it rather than LAMATA be responsible for carrying out the works to improve road surface while LAMATA would build the bus stops and terminals. The resurfacing was delayed for years, in part because the Ministry lacked funding, and the cooperative finally was forced to begin service in early 2011 with the works incomplete so that it could earn revenues to meet its lease obligations. It was too soon to tell, but there were some concerns that the incomplete works would reduce the expected ridership, potentially threatening the cooperative’s ability to pay its leases and still cover its operating costs. LAGBUS. An arguably more serious challenge for LAMATA was the pressure to create new transportation agencies, particularly to operate buses. The public was convinced that Nigeria’s cities needed more full-size busses—the press often quoted an international consultant as saying that Lagos alone needed 6,000, a figure that seemed low if the goal was to retire all the minibuses. As a result, promises of buses were an important “sweetener” in election campaigns in Lagos and other states. And, before LAMATA’s BRT and pilot bus corridors seemed to prove otherwise, there was also a long-standing conviction in the bus industry that the major barrier to their deploying full-size buses was the unwillingness of banks and other lenders to finance vehicles on reasonable terms. Operators could recover their costs from the fares, the industry argued, but only if the financing terms were reasonable. These arguments led Tinubu’s Deputy Governor to champion the creation in 2004 of a new state-owned company called LAGBUS Asset Management that reported to the Ministry of Transport. As its name implied, LAGBUS’ assignment was narrowly focused: to use Lagos State’s borrowing power to acquire and lease buses to operators on reasonable terms and to establish a bus assembly plant to feed high-capacity buses to the Lagos and Nigeria market. In February 2006 the agency began to receive the first of an order of 200 buses it had negotiated with a Brazilian bus builder. LAGBUS found no takers for its buses, however, because it set a price of 25 million naira (US$ 167,000) per bus when the list price of an Ashok-Leyland was only 9 million naira (US$ 60,000). It has never been clear why the LAGBUS vehicles were so expensive—LAGBUS defenders argue that the agency was trying to build the cost of infrastructure improvements into the bus price while skeptics suspect there were too many parties involved in the transaction each receiving “commissions” of various forms. In any event, the buses sat parked for a year until a few months before the 2007 gubernatorial election, when LAGBUS was ordered to get them on the street quickly. LAGBUS worked with the unions to identify and train the most skilled minibus drivers and got about 60 buses in service before election day. The election eve deployment marked the transition of LAGBUS from a bus lessor to a bus operator. LAGBUS continued to buy busses, with its fleet eventually reaching 550 vehicles. A small number were given to the unions to operate, with LAGBUS assuming the revenue risk and paying the unions a fee per vehicle-mile driven. LAGBUS operated most of the fleet itself with its own drivers, however, and it did not even consult LAMATA about what routes to offer, despite the fact that the LAMATA law was quite specific about the Authority’s powers to regulate bus routes. Some of LAGBUS’ decisions seem to be amateurish, such as its attempt to make an exclusive bus lane by painting lines on the pavement without a physical barrier or other measures to discourage violations. LAGBUS claimed to be profitable, but its accounts were not public and there were suspicions that it was earning just enough to cover the cost of fuel and crews, but not enough to properly maintain or renew its fleet. Whatever LAGBUS’ failings the company seemed to enjoy the government’s support, perhaps because it was putting so much service on the street. The dispute over LAMATA’s powers to regulate LAGBUS dragged on until late 2010, when LAMATA was pressed to grant LAGBUS a “universal service license” that allowed the bus company or its sub-contractors to operate any service, other than BRT services, it thought suitable. LASWA. A new agency was also created for ferry services, which are thought to have great potential in Lagos because the central business district is on an island connected to the mainland by only three bridges. The existing ferry 9 The bank in this case was Unity. Banks had become more willing to lend to bus operators after the successful experience of the BRT Lite corridor 6 services were limited and provided by old and unsafe boats with poor connections to the bus services. Governor Fashola had promised to improve ferries during the 2007 election, and met with LAMATA to review its plans soon afterward. But in 2008 he created Lagos State Waterways Authority (LASWA) to prepare the necessary infrastructure and contract with private operators to provide service. At least in this case LAMATA’s authority to plan was not directly challenged, even if it was no longer directly supervising the operators or providing infrastructure. Moreover, LAMATA was playing an increasingly important role in planning and executing investments. Long Term Planning and Investments The Strategic Transport Master Plan. LAMATA’s senior management thought it important that the acclaim the agency was winning for its BRT Lite and road maintenance did not obscure the agency’s larger responsibility to plan the entire public transport system. Accordingly, LAMATA devoted considerable resources to developing a Strategic Transport Master Plan (STMP) for Lagos. The plan, released in December 2009, was the product of extensive consultation with stakeholders coupled with state-of-the-art models to forecast future travel patterns and the benefits and costs of alternative policies. The number of weekday person trips was projected to increase from 17.5 million in 2008 to approximately 30 million in 2020, with potentially disastrous consequences for congestion. To cope with the increase the plan set out three overarching goals, seven areas of action and 25 specific policies. But the heart of the plan was ten key decisions:10 1. Develop a fully integrated mass rapid transit system (MRT). 2. Establish a full-scale transport authority for the Lagos metropolitan area with its first phase as public transport authority. 3. Construct a high-standard full ring road around Lagos metropolitan area with connections to the current main road network through new and improved links. 4. Clear and remove all bus parks and market activities that impede road right-of-way and relocate to them to off-street facilities. 5. Introduce a common ticketing regime for all formal and regulated public transport modes to ensure uniformity and fare integration. Passengers should be able to use a single ticket for one journey on multiple modes. 6. Establish an integrated passenger information system to provide passengers with real-time trip information at bus stops, terminals, websites and call centers. 7. Develop a full network of water commuter routes to supplement land-based MRT systems. 8. Widen at grade intersections, install traffic signals and manage traffic through a modern traffic control center. 9. Require all new construction developments in the metropolitan area to obtain a building permit only after conducting a traffic impact assessment and fulfilling traffic mitigation measures. 10. Develop rational investment plans based on rigorous cost-benefit analysis and attract significant privatesector financing through viable Public-Private Partnership (PPP) schemes 10 This list is a slightly edited version of the one appearing at Lagos Area Metropolitan Transport Authority, Strategic Transport Master Plan, p. 6. 7 The plan went on to outline an ambitious investment program whose benefits exceeded its costs including: • • • • Nine new BRT lines totaling 183 kilometers at a projected cost of US$ 5 to 10 million per kilometer, Seven new rail MRT lines and a monorail totaling 266 kilometers at a cost of US$ 30 to 40 million per kilometer, Ten ferry routes totaling 156 kilometers at a cost of US$ 2 to 10 million per route, and Sixteen new road projects including a fourth mainland bridge and the 100-kilometer ring road at a cost of US$ 3.6 to 4.0 million per kilometer. The Blue Line. Governor Fashola had decided that rail lines and expressways should be the legacy of his second term so LAMATA’s ambitious investment program must have pleased him. But Lagos State did not have the resources, even using PPPs, to pursue all the projects LAMATA had outlined, so priorities had to be established. In 2008, when the strategic master plan was still in draft, the Governor decided to build the Blue MRT Line first and gave LAMATA the responsibility for executing the project. MRT lines to Lagos Island would provide badly needed capacity to the central business district (which was located on the island) and two such lines, the Blue and the Red, were on the top of everyone’s list. The Red Line had higher forecast ridership because it travelled north from Lagos Island through some of Lagos’ major residential and commercial areas. But the Red Line required the cooperation of the federal government since it exploited an underutilized line of the national railway. And cooperation was not always forthcoming because the Lagos State and the federal government were traditionally controlled by competing political parties. The Blue Line had fewer forecast riders, but it travelled west from Lagos Island in the median of an existing highway and the federal government had already consented to its development, so there was little risk that the federal government would hold up the project. The Blue Line had to be done in phases, however, because of the high cost. The entire line of 27 kilometers was projected to require an investment of US$ 1.8 billion, more than Lagos State could easily finance. In the end the Governor decided to start with a first phase consisting of the seven kilometers of track closest to the island but without a bridge to cross to the island itself. The rail bridge would be built in a later phase, but until then passengers would switch to a bus and cross over one of the highway bridges in order to complete their journey to the central business district. Phase one was itself broken into two parts to increase the chances that service would commence before the 2015 elections. The basic civil works were already under construction by a Chinese company under a negotiated contract and funded from general revenue of Lagos State government. Meanwhile, the government and LAMATA were negotiating with a consortium of Nigerian investors and international operators and suppliers for a PPP to build the signals and power distribution systems, procure the rolling stock and operate the line for 25 years. The government was likely to have to pay the operator a fee during the first phase of operations since the fares paid by Blue Line riders were unlikely to be enough to support the PPP. Lagos Urban Transport Project Two. The government had approached the World Bank about participating in the financing of the Blue Line, but eventually abandoned the idea in part because of difficulties meeting the Bank’s stringent procurement rules. But in 2010 LAMATA received a vote of confidence when the World Bank approved a follow-on to the original Lagos Urban Transport Project. LUTP2, as the new project was known, would have US$ 290 million in donor funding, more than double the funding of the original project. Approximately US$ 50 million would be used for improvements to the original BRT Lite line, US$ 170 million to build a new 30-kilometer BRT line and the rest for capacity improvement and traffic management. A Model? Meanwhile in Kano, the main commercial city in Northern Nigeria which had a population of 5 million, a new governor had just been elected on a platform of reducing unemployment and improving public transportation. Responsibilities for public transport were divided among the state Ministry of Works and Transport, the Urban 8 Planning Department, the Vehicle Registration Agency, and the Traffic Enforcement Bureau, among others. And the Public Transport Department in the Ministry of Works and Transport had an ambiguous mandate and few resources. Kano viewed LAMATA as a model, but LAMATA and its leadership had been frustrated to some extent. In what respects had LAMATA been a success and in what resects a disappointment? What accounted for the successes and what for the disappointments? And what were the key lessons that Kano and other metropolitan areas should draw from LAMATA’s experience? Exhibit 1: Map of Lagos Metropolitan Area with proposed mass rapid transit lines Source: Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority, Strategic Transport Master Plan for the Lagos Metropolitan Area, December 2009. 9