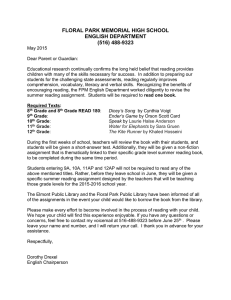

COMMENT NATIONAL OPINION Robots aren't stealing jobs: truth behind claim scaring pants off our graduates By Ross Gittins Updated December 13, 2017 — 1.19am, first published December 12, 2017 — 3.30pm A 118 A A View all comments For me, one of the most significant economic developments of this year was realising how pessimistic many of our youth have become about their prospects of ever landing a decent full-time job. To be sure, some degree of frustration on their part is understandable. Although it's true we avoided a severe recession following the global financial crisis of 2008, it's equally true that, until recently, employment growth has been weaker than usual in the years since then. Illustration: Simon Letch And the burden of this weaker growth has fallen disproportionately on young people leaving education to look for their first full-time job. What's less understandable is the way older, and supposedly more knowledgeable, people have sought to demonstrate how with-it and future-focused they are by spreading wildly exaggerated predictions about how many jobs will be taken by robots, scaring the pants off our youth and convincing them they're doomed to a life of "precarious employment" in the "gig economy". Illustration: Andrew Dyson I'm sorry to say that the otherwise-worthy Committee for Economic Development of Australia was responsible for writing on many young minds the near certitude that 40 per cent of jobs in Australia are likely to be automated in the next 10 to 15 years. The good news, however, is that, for once, economists were moved by all the amateur analysis they were hearing to join the debate about the future of work. Dr Alexandra Heath, of the Reserve Bank, dug out the hard evidence about how the nature of work is changing and Dr David Gruen, of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, put worries about the shrinking number of jobs into their historical context. But the charge has been led by Professor Jeff Borland, of the University of Melbourne, one of our top labour-market economists. With a colleague, Dr Michael Coelli, Borland examined the papers behind the claim of 40 per cent of jobs being lost to robots, and found it built on questionable foundations. In their figuring, the 40 per cent was likely to be nearer 9 per cent. Workers assemble robots at a factory in Shenyang, China. While technology takes jobs away, it also creates complex tasks, leading to new roles. YUYANG LIU And last week Gruen rejoined the fray, giving a big speech about it in, of all places, Jakarta. Predictions about what will happen in the economy can be based on the belief that it will respond to new developments in much the same way it responded in the past to similar developments, or on the belief that "this time is different". People who know little economic history are always tempted, as many people are now, to assume this time is different. But economists have learnt the hard way that this time is rarely very different. The fact is, people have been predicting that the latest technology would reduce the number of jobs since the Luddites at the start of the Industrial Revolution. Gruen reminds us that, in 1953, the great Russian-American economist Wassily Leontief wrote that "labour will become less and less important ... More and more workers will be replaced by machines." Borland notes that, in the 1960s, Lyndon Johnson established a presidential commission to investigate fears that automation was permanently reducing the amount of work available. In 1978, Monash University held a symposium on the implications of new technologies, with the convenor predicting that, by 1988, at least a quarter of the Australian workforce would be made redundant by technological change. Then there was Labor legend Barry Jones' prediction in his bestselling Sleeper Wake! that "in the 1980s, new technologies can decimate labour force in the goods producing sectors of the economy". Gruen admits that "there is no doubt that, over the past two centuries, waves of technological change have eliminated jobs, and rendered some jobs obsolete. "But they have also facilitated the creation of new jobs to take their place – either directly, or indirectly as a result of rising standards of living generating new demands." There are two processes at work, he says. One is that technology takes jobs away – this is the bit we can all see. What we can't see is the second process, the invention of new complex tasks, leading to new jobs. The history of technological advance over the past 200 years has shown the second process has broadly kept pace with the first. Computers have been changing the way businesses do their business – and destroying jobs – since the early 1980s. If that's all there was to it, there ought to be far fewer jobs today. But the number of Australians with jobs has increased by a factor of 2.7 since the mid-1960s, while the average number of hours worked per person has remained broadly stable. Fact. Like the economists, I find it hard to believe this relationship is about to break down because "this time is different". What's true is that the nature of work has been changing – slowly – for the past 30 years or so, and this trend is likely to continue. It may accelerate, but it hasn't yet. Using research by Heath, Gruen says routine cognitive jobs (such as office assistants, sales agents, brokers and drivers) and routine manual jobs (factory workers, construction, mechanics) are in less demand, whereas non-routine manual jobs (nurses, waiters, security staff) and non-routine cognitive jobs (engineers, management, healthcare, designers) are in increasing demand. It's the changing nature of work, not a fall in the amount of it, we should be preparing for. Ross Gittins is the Herald's economics editor. Ross Gittins Ross Gittins is the Economics Editor of The Sydney Morning Herald.