Beyond Suzhou: Region and Memory in the Gardens of Sichuan

Author(s): Jerome Silbergeld

Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 86, No. 2 (Jun., 2004), pp. 207-227

Published by: CAA

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3177415

Accessed: 17-04-2020 15:44 UTC

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3177415?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

CAA is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Beyond Suzhou: Region and Memory in the Gardens

of Sichuan

Jerome Silbergeld

Bo (Li Bai), who wrote, "It would be easier to climb to

The title of Maggie Keswick's book The Chinese Garden, which

Heaven than to walk the Sichuan Road, / And those who

has served as American readers' most popular introduction

hear the tale of it turn pale with fear."8 Readily accessible only

to this topic since 1978, provides both a label and a limit for

through the treacherous Yangzi River gorges,9 Sichuan was

the study of Chinese gardens.' Put in the singular, it suggests

the nearly impregnable stronghold to which the Chinese

an isolated species so self-contained, so coherent and distinct

from other varieties, that little or no internal differentiation

government retreated for safety during its twentieth-century

need be discerned by the armchair audience.2 The titlewar

of with Japan. In earlier centuries, Sichuan became indeOsvald Siren's earlier classic on the subject (1949), which

pendent of the rest of China during nearly every major

Keswick's book supplanted, suggested otherwise: Gardens

national

of

upheaval, including the third, the tenth, the thirteenth, and the seventeenth centuries.10 In each of these

China. Yet Siren's first chapter, entitled "The Chinese Garden-A Work of Art in Forms of Nature," brings us right back

periods, as China experienced decline, Sichuan flourished,

benefiting from all those who fled the turmoil of the national

to the point, as does the very first sentence of his text, which

capital

begins, "The Chinese garden, considered as a special type

of and other cultural centers and filled Sichuan's cities

with refugee artists and poets."l Its cultural history resembles

landscape gardening..."3 To give them their due, these

books and various others of their class do differentiate, and

a light flickering on and off, sparkling when the rest of China

they recognize not just one type of garden but two: imperial

goes dark and dimming while the rest of China glows. Si-

gardens and scholars' gardens. This duality is based not

chuan

so (or Shu) has been described as a kingdom within a

much on historical evolution or geographic diversity as itkingdom,

is

and the Chinese have an expression about its hison royal versus private patronage and the predictable differtorical cycle of dynastic rise and fall: "When the nation has

ential in physical scale and degree of visual grandeur-in

not yet rebelled, Sichuan has already begun to rebel; when

other words, a sumptuary distinction.4 Only coincidentallythe

do nation is back at peace, Sichuan is the last to be pacified

two different regions tend to provide the essential examples

[Tianxia wei luan, Shu xian luan; Tianxia yi zhi, Shu hou zhi]."

The Chinese also have a familiar term for what we would

of these two different types: in the north, capital sites along

the Wei and Yellow River valleys, Xi'an and Luoyang, origicall a hick or a country bumpkin, and that is a xiali Ba ren,

nally offered up the grand imperial style, now hard to reconliterally, a "villager from Ba," or eastern Sichuan. This sug-

struct, while Beijing and the Manchu summer palacesgests

at how remote and provincial Sichuan might seem to the

Chengde today supply the only actual surviving examples;rest

in of China, its local customs poorly understood and its

the south, the Yangzi River delta towns give us the smaller,

history poorly recorded, so "quaint" that until a couple of

more austere private gardens, ranging from Yangzhouyears

to ago its famous river gorges appeared on a low-denomHangzhou, with Suzhou at their center. Siren wrote inination

his

bill with a Tibetan woman and Moslem man on the

reverse (Fig. 2). Yet Sichuan is scarcely a cultural backwater.

preface, "The present work is not the result of any systematic

The poets who came from or dwelt for periods of time i

preliminary studies, it has not been prompted by the ambiSichuan illuminate-even dominate-China's literary hall of

tion of scientific research, but is simply a resume of memories

including Sima Xiangru (179-117 B.C.E.), Yang Xion

I have preserved from former years of wandering abroad,fame,

of

(53 B.C.E.-18 C.E.), Chen Zi'ang (661-702), Li Bo (701-762

impressions I received in the course of rambles in Peking

Du Fu (712-770), Yuan Zhen (779-831), Su Shi (1037parks and the gardens of Suzhou."5 Later writers have been

1101), and Lu You (1125-1210). As for its architecture, at

scarcely less circumscribed in their wanderings, and this includes Chinese writers as well. As demonstrated by the map

first glance, it appears strikingly different from everything

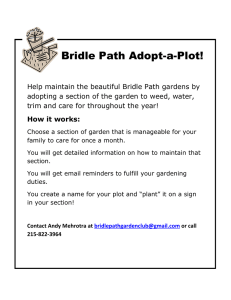

one is taught about traditional styles and techniques-isofrom Peng Yigang's excellent Zhongguo gudian yuanlin fensi

[Analysis of the traditional Chinese garden] (Fig. 1), lated

the Sichuan preserving in its architecture some strange

as exotic to the traveler from another province as it is

author has made his way south to a few of the gardens in jewel,

the

to the foreigner already acclimated to China. Yet nationalist

Guangzhou area, but vast areas of China remain unexplored

by him and by others.6

pride after 1949 displaced regional awareness, and only with

itsofgradual revival since Mao Zedong's death in 1976 have

There's a hole where Sichuan ought to be in this map

conditions become ripe for Sichuan locals once again to

our architectural knowledge, so it is a map of our present

appreciate their distinctive cultural heritage and for a handignorance as well. It is also a reminder of the historical

ful of specialists to begin developing a crude index of Siisolation of this huge province: traditionally, larger in area

and population than any European country, it is walledchuan's

off early surviving architecture.

Before defining and interpreting a distinctive "Sichuan

from the rest of China in all directions by impassable mounstyle" (or what later will more accurately be refined into a

tains, like a huge Switzerland, and distinct in its own history

style"), something should first be said of the other

and regional customs.7 Sichuan's landlocked isolation "Chengdu

has

been famously described by the mid-eighth-century poet styles

Li

that are already well understood. The northern impe-

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

208 ART BULLETIN JUNE 2004 VOLUME LXXXVI NUMBER 2

BB ""e *S L

l {bjmm M.,I:m. ~J-ra~, ?r. ta ft<a) /.t a-MM

. B*I. Bl* ?('-t{,tf}. iff. .ffl1- ^ fl *t,

'lmtbl. tFR!-w,. Mllbt-i. -nWRl~ ftf. #iskt.

wittsB. IrNI--rrwttit$t <totfi,. ?pu l <w*>. -, >K-

st*..

. MMSOX0

6 XBMPtlItNAb

hlf

9}lA W).

f . WMEB

. 1r8t'TWft *,

iyj t<tPB4+?*

X-b;I. * mj?i. abql* ioBH -w1<'PeS1.ij t .v wS

AR:. I~lJO?. 'it'. wMK1 t;--. w MS. '"i',^^ '

S~Ir--Slt. 111* Y;f*'M'll~l~lgita~o H; 9t' 1 ~ !1~

lAqfiffrtA-i. ?:-^w?*ft.?B. wtt

tkt *AWJ, . Bw B.E* ?

?1Jrt<hrlt ~i ?a < t8f ff t . ItMAf. 1t0fcP 4 , 't411

rm ; m <fr t7jt<al(k^. I hmi h llS't' J lfl

_K,C ~ c, f 13f 1 Map of China showing areas where

garden research has been undertaken

*:"-'. j* .4 (from Peng Yigang, Zhongguo gudian

* Gc. Ot < Bat Ryuanlin fensi, 56)

2 Five-yuan note depicting the

Kuimen Gorge of the Yangzi River,

~:;:.i *;77'i ^?^ 1980

rial gardens, most scholars today believe, had their typological origins as long ago as three thousand years in vast royal

them of success in politics. The design of those gardens gave

hunting parks, in combination zoological, botanical, and

geological gardens (theme parks, in the most literal sense),

voices in Sima Xiangru's poem, knights from three different

parts of China (including Chu, just to the east of what is now

Sichuan), went on and on about their respective lords' royal

which both figuratively and literally were understood to rep-

later poets ample fuel for verbal extravagance; the three

resent the entire terrestrial realm. As microcosms now be-

parks, each proclaiming theirs the grandest, like three

lieved to have been constructed in order to legitimize

the braggarts on their barstools.'3 What we know of

drunken

authority of their royal owners, these vast parks aroseroyal

evenparks in the most recent thousand years suggests that

before the first emperor sat on the throne of a unified

China

they

pale in comparison with those earlier prototypes. The

in the late third century B.c.E.12 From early literaturefactors

like that led to this decline would not have been singular,

Sima Xiangru's famous "Zi xu," or "Sir Fantasy," we can

guess

but

the rise of private gardens must have helped to strip the

that the various regional rulers of early China competed

royal parks of their unique aura. We should also imagine, I

almost as much through the magnificence of their parks

andthat the rise of private gardens was met with efforts by

think,

their palaces as they did on the field of battle, confident

China's rulers to maintain their architectural exclusivity, but

perhaps that success in the architectural realm would assure

as the royal prerogative became increasingly less enforceable,

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION AND MEMORY IN TIIE GARDENS OF SICI-UAN 209

3 Copy after Wang Wei (699-759), Wang River Villa, section of a handscroll, ink and colors on silk, Ming

Museum (from Harry Trubner et al., Asiatic Art in the Seattle Art Museum [Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1

sumptuary laws were negotiated to minimize served

the rate

as a and

sacred precinct on which was set a Chinese-styled

scale of encroachment.

eight-sided, nine-story pagoda, drawing the focus of the othe

The earliest private "garden" sites, it is thought, werebuildings

found

away from them and their courtyard interiors.16

rather than built, exemplified by the Bamboo Grove of

NanThe

secular, aristocratic gardens of the late Heian and K

jing's famous "Seven Sages" (a group of celebrated individumakura periods known to us through surviving screen paint

alists from the third century C.E.), or at least relativelyings,

simple,

such as the Jing6ji's Senzui bybbu (Landscape foldin

like Wang Xizhi's (303-361) waterside Orchid Pavilion

(Lan- retained much of this open, pond-oriented layo

screen),

ting) on the slopes of Mt. Lanzhu in Kuaiji Prefecture

(near

even

as the buildings themselves were being converted t

modern-day Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province) and Tao accommodate

Yuannative Japanese structural traditions.17

ming's (365-427) humble eastern fence, five willows,

and

The

next step historically, which generated the privat

chrysanthemum beds planted by his own hand somewhere

in as we know it in later times in Suzhou, gradual

garden

the shadow of Mt. Lu.14 It did not take long for the private

shifted the balance toward prioritizing mountains over water

garden to evolve from such humble means into privately

yang over yin, or at least toward equalizing the two, by fig

owned estates like Wang Wei's (699-759), which sprawled

ratively transporting the mountains into and distributin

along the banks of the Wang River south of Xi'an, with

them throughout the garden and representing them not by

rambling villas and thatched halls, a deer park, and even the

islands within water but by large chunks of rugged rock. Roy

site of an ancient temple ruin (Fig. 3).1 Recorded for posparks led the way, and in no royal park was this more elabo

terity in his own painting and poetry, and perhaps the most

rately carried out than in that of the early-twelfth-century

famous garden of all time, Wang Wei's Wang River Villa dates

emperor Huizong (Zhao Ji, 1082-1135, r. 1101-26), the

to the 730s and 740s, and by then private gardens ran both

Genyue (Gen Mountain) Garden in Bianliang (modern

large and small. Regardless of scale, they often shared a

Kaifeng). Motivated by the pronouncement of the royal fangstructural concept developed along the lines of emerging

shi (soothsayer) at the outset of Huizong's reign that for him

fengshui ideals like those that YangYunsong (ca. 840-ca. 888)

to breed male heirs, which he then lacked, he needed to

formalized soon afterward. This employed a classic pattern of

supply gen-indicated by the seventh of the Book of Divinamountains to the rear (meaning the north), water flowing

(the Yijing) eight trigrams, literally, a yangline over two

southward through the property and pooling in thetion's

front,

yin

lines,

reduplicated, and the fifty-second of the book's

and buildings well protected within a so-called dragon's lair,

sixty-four

hexagrams, standing for mountain and stability-in

making pooled waters central to the design and proximate

to

thedoform of more rockery in the northeastern part of the

the inhabitants, while mountains were peripheral to the

capital

main, with architecture opening outward to receive them

as city.18 Huizong went to work massively importing

rocks from

"borrowed scenery." Such pond-centered, outward-looking

the south of China and became infatuated with

the kind of rocks found in the acid waters of Lake Tai near

gardens typified a high Tang style found not just in private

Suzhou. With the help of flotillas that plied the Grand Canal

Chinese gardens but also in palace architecture and Buddhist

ferrying

temples, in China, Korea, and Japan, like the Hosshoji

in mountains of rock, his enterprise became known

from 1105 on as the Flower and Rock Network. This was

Kyoto, built on a grand scale by the Heian-period emperor

shortly afterward by Zhang.Hao (ca. 1180-12

Shirakawa from 1077 onward (Fig. 4). Here, a low-lyingdescribed

grassy

island set within the lake symbolized a world-mountain

who

andwrote, without much exaggeration:

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

210 ART BUI,I,ITIN JUNE 2004 VOLUME LXXXVI NUMBER 2

I

_-

I

I I

I

I

- a;

I. C

!nl,

4 Hossh6ji, Kyoto, reconstr

ground plan, ca. 1083 (from

Kobayashi, Japanese Architec

The expenses involved... are easily

stones of

reckoned

scholars' gardens to

with be

mineral

alpigments, as in the

most infinite in number. Common

were

handscrollpeople

attributed to

Xie Huandis(act. 1426-52) depicting a

patched to search around cliffs and

sift famous

through

swamps.

historically

ninth-century

gathering but in a garden

Shrouded and secret locales were not disregarded.

... Mountains were hacked to pieces and rocks were

carted away.... every possible scheme was used in order

design that one might guess was brought thoroughly up-to-

to get the rocks out and to their destination.... The boats

continued, one after the other, day and night, without a

of the Chinese scholars' paintings, calligraphies, poems, mu-

break.... Still, they did not supply enough.19

Quite literally, Huizong broke the royal bank with these

enterprises and got into such political trouble for it that

neither he nor his dynasty could get out of it again. One

might think that the collapse of the Northern Song dynasty in

1126-27-with the sack of the capital city byJurched Tartars,

date (Fig. 5). Such gatherings are also a reminder that the

garden-based studio was the site where a substantial portion

sical compositions, and philosophical essays were produced

over the centuries, inspired by the garden's aesthetics and

energized by the gathered yang and yin forces placed at the

disposal of the painter-writer-musician. Paths of stone lead in

and around exotic rockery gathered from Lake Tai, erected

in the garden as miniature mountains, simulacra of the real

thing. Inside the studio, where the scholar executes a poem

or a painting-perhaps a painting-within-a-painting or a

the capture of Huizong and the Song royal family, and the

flight of a rump court south to Hangzhou-might forever

poem descriptive of this very garden-we also see the minia-

have given intensive gardening a bad name in China, but the

continued evolution of garden style toward petromania went

on unabated. It is not, however, in the increasingly conserva-

collectible items,20 we might regard such stones today as an

ture mountains further miniaturized into the form of a small

desk-top stone. Increasingly valuable in their own day as

tive traditions of palace gardens that this development cul-

early form of "found art" but for the fact, frequently over-

minates but rather in private scholars' gardens.

From the fourteenth century on, one increasingly finds the

visual celebration of rockery, of yang, wherever one turns to

whose intent was to thoroughly disguise their unnatural ef-

gaze on the garden. Some paintings rendered the gathered

include this material, this is what became of the high art of

looked, that they were often very carefully worked by artisans

forts. Although modern books on Chinese sculpture never

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION AN)D iMEMORY IN iTHE GARDENS OF SICIIUAN 211

5 Xie Huan, Ming dynasty (1368-1644), The Nine Elders of the Mountain of Fragrance, detail of a handscroll, i

height 12 in. (30.6 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. A. Dean Perry, 1997.99 (photo

Museum of Art)

Chinese sculpture in the last millennium, an abstract equivalent to The Three Graces and other masterworks of the West-

ern classical tradition (Fig. 6). All these stones-taihu from

Suzhou, lingbi from Anhui, yingstones from Guangdong, and

so forth-allowed painters to model their landscapes without

having to leave their studios at all.21 Sliced marble from Dali

in deep southern Yunnan Province produced an accidental

landscape once every hundred slices or so, more valued the

closer they came to styles of landscape actually practiced by

painters. These were set into furniture or displayed on the

walls (Figs. 7, 8). Lovely examples were framed and hung, like

minimalist paintings. Outside the studio, terraces of inset

stones, selected for common size, color, and shape, dazzled

and directed the eye. Bridges of stone, elevated, imitate the

bridges leading to heaven and immortality-or imitated the

paintings of such bridges. A hierarchy of stone types was

6 Snow on Mount Yi, white marble scholar's rock, Qing dynasty.

established; a terrace could be built up of lesser quality yellow

Collection of Richard Rosenblum (from Robert Mowry, Worlds

stone (huang shi), with flanking stones made of so-called

within Worlds, no. 56)

bamboo shoot rockery guarding a central stone from Lake

Tai, very much like a Buddhist temple altar with guardian

deities flanking a central icon (Figs. 9, 10). The analogy was

With the bringing of mountains-as stones-directly into

undoubtedly intentional and the veneration of great rocks

the courtyard came the development of an architectural array

very real; their power-male, yang, phallocentric-was no less

that no longer turned outward toward some borrowed scenpotent than that of anthropomorphic icons, and no less

ery of distant mountains but rather looked inward, addressgenuine than their own aesthetic impact.

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

212 ART BUI.'LETIN JUNE 2004 VOIUME I,XXXVI NUMBER 2

7 Marvelous Peaks, Blue and Green, framed marble from Dali,

Yunnan Province. Suzhou, Liu Garden

8 Ma Shirong (active ca. 1132-62), Landscape, fan painting,

ink and colors on silk. Beijing, Palace Museum (from Song ren

hua ci [Beijing: Zhongguo gudianjishu chubanshe, 1957],

ing the miniature mountains close at hand. And with an no. 32)

increasingly self-enclosed and inward-oriented garden, urban, small in scale, and intimate, outer and internal walls

came to matter immensely, defining space as a more complex and surprise, diminished and exaggerated emotions: in other

matter than ever before. Made semipermeable by elaborately words, visual melodrama, but of an intellectually discriminatshaped doorways and uniquely patterned lattice windows that ing sort. A typical view revealed only bits and pieces of a

ultimately became a decorative end in themselves (Fig. 11), complex and convoluted world, an effect comparable to gazthey took a space already small and made it even smaller ining through a crystal on a world in fragments, ongoing and

order to diversify it and thereby make it seem larger. Every endless. The spatial organization dizzied the eye, engaged the

garden became a series of minigardens, each different from senses, and involved the mind, like the multidimensional,

its minineighbors, all spatially interpenetrating (Fig. 12). multimedia display of a great Baroque cathedral-this in

These gardens operated through the principles of gradual contrast to the Renaissance-like clarity set forth in earlier,

disclosure and played on viewer expectations-anticipationsimpler pre-Song gardens.

9 Liu Garden, Suzhou, rocks in the

design of a temple altar

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION AND MEMORY IN THE GARDENS OF SIICHUAN 213

11 Zhuozheng Garden, Suzhou, lattice win

10 Toshodaiji, Kondo (Golden Hall), Nara, main altar, ca. 759

(from Minoru Ooka, Temples of Japan and Their Art [New York:

Weatherhill / Heibonsha, 1973], pl. 43)

';i<8-.1"s

f

-

,/

'

--

-

'2'

T 11

' 9) 0 0 0

-' 0 o o c

0

0

oo s o

0

0

0

0

O

. S o o

-., 'o o o o

.' , o OO

Nets, Suzhou, ground plan (from

Keswick, Gardens of China, 1978, 17)

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A

214 ART BU. LLETIN JUNE 2004 VOIUME LXXXVI NUMBER 2

c

4

4

4

4.

I,

z

-?.--

.,e

z

s

z

5

II,

-L

-?I

-L?

bLLilu

13

Du

Fu

Thatched

Hall,

Much

of

this

sense

of

attention

to

(1301-1374)

engaging

the

visitor's

im

and

Wen

Zh

tional

expectations

with

1551

depictin

a

pavilion

conventionally

of

Chinese

ga

of

the

garden,

disclosing

Suzhou's

so-c

viding

the

tourist

a

prim

products

of

m

garden.

But

in

Suzhou'

Nets,

a

pavilion

the

is

twentiet

hauled

ings

is

as

pe

half,

and

plastered

up

ag

a

pavilion

to

dating

facilitate

of

bui

a

g

date

of

a

pain

here

dislodged,

and

the

r

like

an

icon

nese

in

a

painter

templ

gardens

of

detailed

Suzhou

are

subje

f

eve

prises,

moresurpassed

often

than

n

alter

such

su

Figuring

out

how

quic

and

how

to modern

date

archite

hist

with

accuracy

den's

continuing

evolutio

historian

a increasingly

series

of

co

made

of

wooden

The

Chinese

modul

necessity

dictates.24

in

supplying

Aft

all

of

one

age

sites.

but

In

a

bioni

sur

the

rockery,

easier

the

water

and

mo

fe

relevant

text

of

a

garden.

Dated

pain

gardens

serve

matters.

as

valuable

It

is,

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION ANI) MEMORY IN THE GARDENS OF SICHUAN 215

.

?

.

.

-

?

.

i~'~" .. , , . ~ ~,, e .~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~.

.

-.

X,

1

> > r + ^<-tw , - .i':'., ' ' '-' ,~[..''i.: '?' . ' '- -

: i~~~~~~~~~~~i

14 Shrine of the Three Sus, Meishan, schematic drawing (from

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.-

_ t ,~Z .RI

*?1,~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~[~ ::'.~-~.~y. r ..:

15 River Viewing Tower Park,

Chengdu, rockery

All the

of this

is general background based on

that it is easier to describe with some accuracy

differenSuzhou

model but essential to appreciate before

tiation by place, region by region, in Chinese

architectural

Even

the most cursory look at the lay

history than it is to account for the subtleSichuan.27

changes in

style

over relatively short periods of time.

du's Du Fu Thatched Hall (Du Fu cao tang, na

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

216 \AR BUIIETIN JUNE 2004 VOI.UMEE I.XXXVI NUMBER 2

16 Shrine of the Three Sus, Hall of

the Wooden Miniature Mountain

17 Du Fu Thatched Hall, Water Gate (Shui Hsien, foreground) and Droplets-of-Dew and Wind-in-the-Leaves Veranda

Fengye Zhi Xuan, background)

Tang poet Du Fu) or Meishan's Shrine of the Three Sus

(Sanor by conscious archaism preserving an open-styl

vation

Su ci, named for the Song poet Su Shi, his father,architectural

and

design reminiscent of classic Tang garden

brother) reveals the historically conservative aspect(Figs.

of Si13, 14). Unlike Suzhou's urban gardens, which turne

chuan-style garden layout, whether by uninterrupted inward

preser- on a mere half acre to an acre of land, these gardens

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION ANI) MEMO)RY IN THE (AR)DENS OF SICIIUAN 217

18 Du Fu Thatched Hall, Water

Bamboo Dwelling (Shui Zhu Ji), view

from the interior

19 Huanxiu Garden, Suzhou, limestone garden rock

20 Shrine of the Three Sus, black walls

are often suburban or rural and sprawl over five or six acres,

tion, often unkempt and including thick stands of tall bam-

like an aristocratic Tang estate (Fig. 3). Their architectural

boo (Figs. 18, 36), adds a visual density to the garden not

array, rather than dense and crowded, is sparse, their courtprovided by the architecture itself. Partly as a result, the

yards large and loosely compounded. Each main compound

entire palette by which Sichuan gardens are colored differs

tends to retain its structural independence. Water is brought

from that of Suzhou or Beijing as conventionally as the

in from sources to the north, drawn down the west side and Venetian palette did from the Florentine or the Roman.

sometimes the east, and pools in front of the main halls. In The palette of royal architecture in Beijing, like that in

Chengdu's or nearby Meishan's gardens, the mountains reTang-period Chang'an, was grand, loaded with deeply satumain far outside the garden; the stones inside are few, rela-rated reds, greens, blue, and gold. Suzhou wall colors, by

tively unimportant, and mostly of local varieties that a Suzhou

contrast, are plain, simple, and elegant: uniformly whiteconnoisseur would consider provincial and inferior (Fig. 15).washed stucco-covered walls contrast cleanly with brownish

Their near absence takes us back to an earlier era. The most

red lacquered columns and doors, pale stone, and gray-tiled

conspicuous miniature mountain (jia shan, "false mounroofs. Limestone set against lime-painted stucco walls protains") at the Shrine of the Three Sus is made not of stone

ducesbut

a beautiful tonal minimalism (Fig. 19). In Sichuan, on

the other hand, as in Meishan's Shrine of the Three Sus,

of wood (Fig. 16). The horticulture in Suzhou's gardens

today is carefully limited and distributed, much of it semior

black lacquer

columns, doors, and windows, gray roof tiles,

fully miniaturized, just as the rockery is. In contrast,

Si- some black- and gray-colored walls all plunge the

and even

chuan's gardens settle beneath a spreading canopy architecture

of fullinto reclusively deep shadow (Fig. 20). And in

scale vegetation, far wider in variety and collectively casting

a

the maintenance

of these gardens, one finds water deep

darker shadow over the gardens (Figs. 17, 18). The green,

vegetadark and fertile as compared with Suhzou's garden

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

218 ART BULLETIN JUNE 2004 VOLUME LXXXVI NUMBER 2

21 Wu Hou Ci, Chengdu, red wall with carved calligraphic inscription by Yue Fei (1103-1141)

22 River Viewing Tower

culture today (Fig. 17). The occasional use of dark red walls

in some of these gardens, a peculiarity I will come back to

shortly, further adds to the tonal depth (Figs. 21, 35, 36),

as do the shadows cast by multisided, multistoried towers

(lou)--an architectural element not to be confused with the

Buddhist pagoda (ta), though not unrelated-almost never

seen in Suzhou gardens (Fig. 22). The circular (one-sided),

square (four-sided, not rectangular), or polygonal (eight- or

twelve-sided) building, with conical or pyramidal roof, is rare

in China, almost always seen either as state temples, as Bud-

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION AND IMEMORY IN T-IE GARDENS OF SICHUAN 219

dhist pagodas, or as single-story garden pavilions (ting) and

towers (lou).28 The dual appearance of such structures in

temple and in garden architecture reinforces an awareness of

the garden's religious overtones. Sichuan's multistoried towers, reaching heavenward, invoke this relation even more

strongly than the ordinary garden pavilion.

The dark naturalism of Sichuan's gardens matches the

character of the province, heralded in its own poetry as

"luxuriant," "secluded," "dangerous," and "heroic."29 This

rustic preference for rugged, primitive naturalism rather

than urbane elegance is pursued in Sichuan's finest garden

architecture, from its general aspect down to its smallest

details. The placement of roof tiles, which in most Suzhou

buildings typically includes a smooth sheathing layer of flat

tile and a layer of mud beneath the double layer of trough

and seam-covering tiles, in Sichuan is structurally much sim- 23 Du Fu Thatched Hall, bamboo gate and fence

pler, more primitive: the lower layers of sheathing and mud

are completely omitted, with the trough (yin) tiles slung

directly onto the rafters, visibly hanging down between them,_ . t7..?, ' -

and with small amounts of mud troweled between them and

the thin strip of each rafter to hold them in place. All the tiles - "i'are thinner than in Suzhou, the roof weight considerably less, '

and the whole affair technically less polished, with leaking

rainwater a much more common problem and replacement

more frequent. In Sichuan gardens, one finds primitive bamboo gateways and wattle fences that a Japanese gardener

might feel at home with (Fig. 23) but unlike those that are

usually found in Suzhou or Beijing, Xi'an or Guangzhou. On

Mt. Qingcheng, the sacred mountain chain west of Chengdu,

where institutionalized Daoism found its first home in the

first century C.E., one finds pavilions so primitive they look

almost like a bird's nest stuck together with twigs, or at least

like a man-made birdcage (Fig. 24). The timbers are not even

stripped of their bark. This reversion to the primordial ori-

gins of human architecture touches aesthetic bedrock and

resonates compellingly with Daoist fundamentals. Ironically,

then, this simple structure constitutes one of Sichuan's most

esteemed works of architecture.

Most importantly, most Sichuan buildings are engineered

in an entirely different way from Chinese buildings elsewhere, the two systems as different as Gothic was from Ro-

manesque but with region as well as chronology shaping the 24 Hillside pavilion, Mt. Qingcheng (photo: Jim Dawson)

, o t4?4?

25 Tailiang construction (from L - XL

Andrew Boyd, Chinese Architecture and

Town Planning [London: Alec Tiranti,

1962], 29)

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

220 ART BUI.ILETIN JUNE 2004 VOILUME IXXXVI NUNMBER 2

26 Du Fu Thatched Hall, Water

Bamboo Dwelling, view from the rear

27 North Hotsprings Park, Chongqing, chuandou construction

28 Wu Hou Ci, roof-ridge decoration

difference. Best known throughout most of China, the tai- virtually no architectural renderings from Sichuan exist to

liang or liangzhu system of stacked and elevated tie beams and steer architectural historians toward a dated history, and

struts used for suspending the roof beam, purlins, and rafters Chinese painters everywhere tend to shy away from depicting

is efficient, reducing the need for tall timber (Fig. 25). But

the gable end-the informal but structurally more revealing

Sichuan's chuandou system uses tall timber from ground to

side of buildings.) Other features found consistently throughroof, often placed at close intervals along the gable end and

out this architecture include radically upturned corners with

tied together with horizontal beams that penetrate the holhigh ridges made of sculpted clay;3l ridge beams tiled with

lowed-out posts (Fig. 26). When repeated through the length sacred jewel patterns, derived from the pearl-and-flame motif

of the building, this arrangement of posts breaks the interior of Buddhist architecture but typically found on even the

space into small rooms, so the system is no more efficient in humblest domestic buildings (Fig. 28) ;32 decorative sus-

expanding space than it is in conserving raw materials, but pended plumbs carved in floral designs (occasionally found

elsewhere in China but consistently used only here); the

until recently, rugged Sichuan has had timber to spare. The

tailiang system is basically designed for efficiency but operates

within a narrower range of variables, both structurally and

visually, providing little aesthetic variety. Sichuan's chuandou

system, on the other hand, leaves the architect free to use the

frequent use of stilts to support second-story storage rooms

and sometimes whole hillside buildings; the rarity of brackets,

which elsewhere serve as a defining feature of institutional

architecture; and diagonal struts, often carved with symbolic

gable ends of the building like a painter's canvas, creating patterns, extending upward from the columns to the eaves

patterns that emerge, like Piet Mondrian's designs, in seem-

purlins and taking over the function of the missing brackets

ingly endless variation (Fig. 27).30 (As mentioned earlier, (Fig. 29).

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION AND MEMORY IN TI-IE GARDENS OF SIC-IUAN 221

30 Ise Shinto Shrine, Yojoden (photo: Yoshio Watanabe, from

Kenzo Tange et al., Ise: Prototype ofJapanese Architecture, 136)

I

29

I

Du

I

Fu

bearing

Thatched

Hall,

W

struts

31 Farmhouse

northwest of Chengdu

If

Sichuan's

architectur

viving

Japanese

architec

coincidental.

There

is

a

logical remnant

of a distant past that might be supplanted

needs

to

be

explored

at

by a more sophisticated technology

but notShin

surpassed aesJapan's

national

Ise

thetically. Historically,

I propose this thesis: that Sichuan's

distinguishing

features

architecture

preceded China's tailiang;

that itsh

(chigi)

and chuandou

a

series

of

once spread over most(Fig.

of China; that tailiang was

develcalled

katsuogi

30).

these

"have

oped in

a

the early

function,

centuries before the Common Era to

not structural,"33 but on thatched farmhouses near

cope with northern China's gradual deforestation, emergChengdu, we find strikingly similar features, with bundles ing more or less together with dougong bracketing; and that

of rice thatch that help lash down the ridge beam and over the succeeding centuries, chuandou gradually reattach the roofing thatch (Fig. 31). In one of Sichuan's treated to southern and southwestern China with the refinest old buildings, the Water Bamboo Dwelling at the Ducession of China's vanishing woodlot of tall evergreen

Fu Thatched Hall (with a remarkable under-the-floor sys-study of the posthole pattern in ancient raised-founda

tem of ventilation), the latticed windows, full-length along remains dating all the way back to the Shang dynasty

three sides of the building (Fig. 32), bring to mind Ise's 1600-ca. 1035 B.C.E.) in north-central China (Fig. 33),

Yojoden, the latter building probably derived in form from arrayed in depth across the gable end of buildings, supa stable for Japan's sacred horses, and one can readily ports this possibility, complemented by the persistence

imagine that its Chengdu counterpart, if not original tointo recent times of occasional chuandou engineering in

the eighth century, was at least inspired by the memory of the north. The presence of chuandou-like inserted tie

beams and multiple gable-end ground-to-roof columns in

Du Fu's great love for horses and horse paintings.34

Overall, Sichuan's style is both primitive and sophisti-early-eighth-century Japan in buildings like the Horyuji's

cated-like a Gothic cathedral or, like Ise itself, an ontoDenpodo (at Ikaruga, Nara Prefecture, originally a secular

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

222 ART BUI.I.ETIrN JUNE 2004 VOLUME LXXXVI NUMBER 2

33 Schematic reconstruction of ceremonial structure at

Anyang, Henan Province, ca. 1250 B.C.E. (drawing by Shi

Zhangru, from Kwang-chih Chang, The Architecture of Ancient

China, 2nd ed. [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968],

fig. 81)

.

,

4

.

these gardens, a different pattern of usage, and a different

mode of patronage. Whereas Suzhou's finest gardens were

typically private landholdings whose wealthy owners were

32 Du Fu Thatched Hall, Water Bamboo Dwelling, view of

main entrance

often historically marginal figures,3" the major Sichuan

gardens are associated with revered contributors to Sichuan's regional society and literature. Among them are

the brilliant hydrologist Li Bing (early third century

residence, donated and converted in 739 into a Buddhist

B.C.E.), who tamed and reshaped Sichuan's river system as

lecture hall) suggests that chuandou, at least in a hybridized governor of the Shu Commandery under Qin authority,37

form, was still available for transmission from the southern and his son Erlang, the tamer of Sichuan's forests-the two

coast of China at that relatively late date (Fig. 34).35

deified and worshiped together at the Two Kings Shrine, at

In all, then, Sichuan's chuandou architecture is like starDujiangyan;38 or the early-third-century burial ground of

light that allows us to peer into China's distant architec- the ruler Liu Bei (162-223) of the Shu-Han Kingdom and

tural past. This does not imply simply some laggard con- the shrine of his minister, the immensely talented and

servatism, for in decorative details Sichuan has readily popular Zhuge Liang (181-234), who chose to be buried

blended native features with southern Chinese, Southeast

outside the province rather than upstage his own ruler

Asian, and even Tibetan elements into its art of building, (the two figures were subsequently conjoined at the Zhaotogether with northern and northeastern features broughtlie Miao and Wu Hou Ci in Chengdu, Figs. 21, 28, 35);39

in during the various early politically driven migrations the Zither Terrace of the poet Sima Xiangru and the

into the province. But there is a core traditionalism in itsfamous well at which he and his wife Zhuo Wenjun made

approach, evident in the chuandou engineering system andtheir humble living producing wine, in Qiongthe classically Tang-like arrangement of buildings within lai; Chen Zi'ang's study on Jinhua Mountain; Chengdu's

the landscape, and additionally coded by the red stucco Thatched Hall of the eighth-century poet Du Fu, probably

walls mentioned earlier: red stucco used sometimes for

dating back to about the tenth century (Figs. 13, 17, 18, 23,

26, 29,for

32); the Longxi Garden of the eighth-century poet

buildings, sometimes for freestanding walls, sometimes

the long, curving walkways unique to Sichuan's

Ligardens

Bo, in Qinglian Xian; the River Viewing Tower Park,

(Figs. 21, 35). Elsewhere, red walls are normally which

limited

overlooks

to

Chengdu's Brocade River, dedicated to

royal palaces, temples, and shrines, as well as for

the

enshrinninth-century female poet Xue Tao (768/781-831/

ing workers' factories in the Communist era. Their

832), now

preswith its famous assortment of bamboo (Figs. 22,

ence in Sichuan gardens signals the distinctive function

36);40 theof

Shrine of the Three Sus at Meishan: the great

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION AND MEMORY IN THE GARDENS OF SICHUAN 223

:

? s-;li ??

.liEliE

*?- ???

:? ?-

?!; ' . ?;,?,

??: ?r

.? _i :

34 Horyilji, Ikaruga, Nara Prefecture, Denpodo, early 8th

century (from Kakichi Suzuki, Early Buddhist Architecture in

Japan, pl. 90)

eleventh-century poet-statesman-calligrapher painter Su

Shi, his father Su Xun (943-1047), and his younger

brother Su Che (1039-1112) (Figs. 14, 20); the shrine of

poet Lu You at the Yanhua Pool where he served in

Shuzhou (now called Chongqing, southwest of Chengdu); 35 Wu Hou Ci, red-walled walk, behind the Tomb of Liu Bei

and others.41

(Hui Ling)

As suggested earlier, the dating of these garden sites and

their architecture is particularly challenging, and only more

recent dates can sometimes accurately be provided. For ex-with her famous papermaking, was first established in the

ample, the poet Wei Zhuang (836?-910), boating down

Ming dynasty (1368-1644), although it was not originally

Chengdu's Washing Flowers Stream (Huanhua xi), noted in named after Xue Tao, while the stone stela inscribed "Xue

verse that "the column bases still remain" from Du Fu's

Tao's Well" (Fig. 36) was written in 1644 by the mayor of

thatched hall on the west side of town, meaning, of

Chengdu,

course,Bei Yingxiong. The three pavilions of Poetry-chantthat nothing more survived-other than a solitary

ing,

thatched

Paper-washing, and Brocade-washing were not built until

room, which he recorded as hovering over the ruins.42

1814 His(the first of these three authorized by the provincial

torical records demonstrate that in the Northern

governor

Song peand city mayor) and then were rebuilt after burning

downrebuilt

in the early 1850s, and the landmark three-story tower

riod (960-1127), Li Dafang, the prefect of Chengdu,

Du Fu's thatched hall and hung his portrait and for

that

which

local

the garden was later given its name, in 1953, was

builtfunds

in 1889 (Fig. 22). The "tomb of Xue Tao" is hardly likely

officials in the early Southern Song (1127-1279) raised

be hers.44

to extend the hall, add courtyards, and plant trees, to

flowers,

As these two examples suggest, while some of Sichuan's

and bamboo. But how this or the approximately seventeen

recorded further restorations of the next threegarden

dynasties

sites may be original to their owners, others may

been selected and developed only long centuries after

reflected a Tang dynasty original style or is retainedhave

in today's

the death

style is not easily demonstrated.43 In the war with Japan,

theof those they honor (individual buildings are no

to date but are typically much younger than the site

entire site was horribly damaged and required easier

near-total

restoration after the Chinese civil war ended in 1949. In the

itself). But they all function as memorial sites. Thus, their

redand

walls (Figs. 21, 35), thus, the strong presence of meyears since 1981, I have seen both significant erasures

morial tablets, memorial halls, memorial images, and mewholesale additions. The River Viewing Tower Park associmorial

ated with the poetess Xue Tao is built on the wrong side

of stelae (Fig. 36). More like public parks, these were

town, as her known dwelling place was on the east side

sitesof

where the general public could come to venerate

Chengdu rather than the west (she was a near neighbor those

of Du great men and women of culture who had risen

Fu's estate). The well that can be seen there today, associated

among them. Like Beijing's royal gardens and unlike Su-

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

224 \ARI BULL.ETIN JUNE 2004 VOLUME ILXXXVI NUMBER 2

36 River Viewing Tower Park, "Xue

Tao's Well" Stela

great yet

agrarian plain to the west (the Red Basin) and Ba in

zhou's private ones, Sichuan's gardens are institutional,

narrow valley district to the east, domains centered

before this century they were more public than the

either,

despite the fact that most if not all of them actually

de-Chengdu and Chongqing, respectively. Today, this

around

scend from once-private estates. Functionally, these

garancient

political divide has been reestablished with the

dens lie as much in the domains of tomb architecture and

removal in 1998 of Chongqing from the province of Siof Daoist temples and shrines as in that of domestic

garchuan

and the establishment of a Chongqing special ecodens. Some of their patrons who paid for their upkeep

and

nomic

zone that reports not to the provincial governor

development were probably actual descendants, likebut

the

Su

directly

to the State Council (Guowuyuan) in Beijing.

family of Meishan, which sports a huge population

today

Technically,

this makes Chongqing the largest municipalclaiming descent from the famous Su Shi. Otherwise,

paity in

the world, with a population of about thirty million

tronage seems to have been picked up by the civic

and anand

area

the size of Austria. What has been described

financial leaders of the community. The single-ownership

here as "Sichuan style" more closely conforms to a cla

and restricted urban scale of Suzhou's gardens allowed

Chengdu style than to the gardens of hilly Chongqin

periodically for the coherent refurbishing of an inherited

whose profiles are even more rugged and elevations m

design and account for the relative stylistic consistency

ofand whose collective architectural history bey

varied,

each as seen today. The varied architectural assemblage

the mid-nineteenth century is even murkier than that of

within any one Sichuan garden-set on a large and sprawlcounterpart in Chengdu.

ing site, probably with a longer history and more diversiFurther study of institutional records may contribute t

fied patronage than any of Suzhou's gardens-reveals a

further differentiation, but it can still be expected to re

range of visual expression and mixture of details closely

force the general characteristics described here. Sich

juxtaposed, often impossible to sort out by date yet whose

style presumably also overlaps significantly with the

striking inconsistency speaks to a constant change around

gional styles ofYunnan to the south and Hunan to the

the stylistic edges even as the basic system appears to have

Still, just as the gourmet can readily differentiate betwee

remained unchanged. As described earlier, chuandou itself

the spicy cuisines of Sichuan and Hunan for which eac

seems to have encouraged such variation. The conservaequally

renowned, distinguishing what they do not

tism of Sichuan's garden style, then, can be explained not

share

from

what they do, there is a core style in Sichuan's

merely by the general conservatism of this landlocked

garden

architecture,

a particular function and a patronage

geographic bastion but more importantly by the special

pattern

that

come

together

to render Sichuan distinctive

tenacity with which Sichuan, long ignored in the public

in its garden heritage. The presence of such significant

record of China, has chosen to memorialize its favored

regional variation within the Chinese architectural domain

ancestors as a display of regional pride.

may not entirely negate the formulation of an essential

With regional differentiation as a central topic, it would

be inadequate here to essentialize "Sichuan" itself, for "Chinese garden," but it draws attention to the greater

complexity to be found within China's family of gardens

Sichuan is huge and internally differentiated, and aspects

of its style spread beyond the dotted lines of any map. and

In suggests further new horizons for regionally based

architectural study.

ancient times, the region was divided between Shu on the

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

REGION AND MEMORY IN THE GARDENS OF SICHUAN 225

from

Jerome Silbergeld is the P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Professor

of the Southern Song capital at Hangzhou through the Yangzi River

gorges into Sichuan to take up an official post at Kuizhou: "Ru Shu ji

Chinese Art History at Princeton University and director of Prince(Record of Going into Sichuan)," in The Old Man Who Does as He Pleases:

ton's Tang Center for East Asian Art. He has written six booksPoems

on

and Prose by Lu Yu, trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia

University Press, 1973), 68-121.

traditional and modern Chinese painting and Chinese cinema (most

10. Throughout its long history, the area that constitutes modern-day Si-

recently, Hitchcock with a Chinese Face, forthcoming) [Departchuan has undergone repeated transformations in its political and cartographic identity, not until the late 13th century achieving a somewhat stable

ment of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J.

existence under the name Sichuan (literally, the "Four Rivers," counting the

Min, Tuo,Jialing, and either the Qian, the Fou, or the Yangzi River). Looking

back into its tangled history prior to its conquest by the state of Qin in 316

B.C.E. (which later achieved the first unification of China), the region was

08544].

divided into two contending political-ethnic groups, one known as Shu,

centered around modern Chengdu in the west, the other called Ba, centered

Notes

in what is now Chongqing in the east. When China divided into three

contending regions following the fall of the Han dynasty in the early 3rd

century, one of these occupied the southwest, with Chengdu as its capital (far

This research was conducted in the context of helping to design the first

extensive in territory than modern Sichuan) and adopted the name

Sichuan-style garden in the West, for the city of Seattle: the Xi Hua Yuan, more

a

Shu-Han; when China was again disunited in the 10th century after the fall of

project begun in 1986 and still under way. I am greatly indebted to many

the Tang dynasty, Chengdu was the capital of the Qian (Former) Shu Kingmembers of the Garden Bureau of the Chongqing Municipal Bureau of Parks

dom and then of the Hou (Latter) Shu Kingdom (both states fairly close in

and Greenery and especially to vice-director Kuang Ping, who have helped to

stimulate renewed interest in this subject in their own native province, andscale

to to that of modern Sichuan Province). In a 1955 transformation, Sichuan

received the eastern portion of Xikang Province, primarily Tibetan in ethnicmany colleagues in the Seattle Chinese Garden Society, chartered by the

ity, the remainder of which was restored to Tibet. Sichuan remains the most

Seattle City Council, particularly to Jim Dawson, for many years the president

ethnically diverse province in China today.

of the society, as well as to Stella Chien for her cultural leadership. For the

11. For evidence of this among imperial court artists of the early Song

opportunity to present various aspects of this material and receive valuable

period, for example, see the essay by Wai-kam Ho, "Aspects of Chinese

responses to it, I am grateful to Professors Robert Bagley and Yoshi Shimizu

Painting from 1100 to 1350," in Eight Dynasties of Chinese Painting: The Collecof Princeton University, Lothar von Falkenhausen of the University of Calitions of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, and the Cleveland Museum

fornia at Los Angeles, Mike Wan of Notre Dame University, Nancy Steinhardt

of Art, ed. Wai-kam Ho et al. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art; Bloomand Julie Davis of the University of Pennsylvania, and Robert Harrist of

ington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1980).

Columbia University, and to Judith Whitbeck at the Staten Island Chinese

Scholars' Garden, as well as to various faculty and scholars of Lewis and Clark12. On the antiquity of Chinese royal parks, see Edward Schafer, "Hunting

Parks and Animal Enclosures in Ancient China," Journal of the Economic and

College in Portland, Oregon, the University of Washington in Seattle, the Asia

Social History of the Orient 11 (1968): 318-43.

Society in New York City, and the Institute for Advanced Study and American

Institute of Archaeologists in Princeton. I am also deeply grateful to two 13. Sima Xiangru, "Sir Fantasy," in Chinese Rhyme-Prose: Poems in the Fu

anonymous Art Bulletin readers for their probing and helpful comments. Form from the Han and Six Dynasties Periods, trans. and ed. Burton Watson

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1971), 29-54. For an extensive

The photographs in this article were taken by the author except where

collection of such poetry, see Xiao Tong, Wen xuan, or Selections of Refined

noted otherwise. Unless otherwise indicated, translations are by the author.

Literature, vol. 2, Rhapsodies on Sacrifices, Hunting, Travel, Sightseeing, Palaces

1. Maggie Keswick, The Chinese Garden: History, Art, and Architecture (London:

and Halls, Rivers and Seas, trans. David Knechtges (Princeton: Princeton

Academy Editions; New York: St. Martin's Press, 1978; 2nd ed., Cambridge,

University Press, 1987).

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003).

2. Keswick, 1978 (as in n. 1), 24, 2003 (as in n. 1), 37, mentions Sichuan 14. For studies of the Bamboo Grove illustrations, comprising four sets of

tiles from the late 4th to late 5th centuries, at least three of these

only three times during the course of her book, and only in the contextexcavated

of

from royal tombs (showing figures in simplified landscape settings, which

horticulture. Referring especially to Sichuan's azaleas and rhododendrons,

represented the beginnings of the cult of personality in Chinese portraiture),

she writes, "Indeed, in the end, obscure hills and valleys in Yunnan and

Sichuan did more to transform the horticultural traditions of the West than

see EllenJohnston Laing, "Neo-Taoism and the 'Seven Sages of the Bamboo

the designs of all the great pleasure gardens of China-and their underlying Grove' in Chinese Painting," Artibus Asiae 36 (1974): 5-54; and Audrey Spiro,

Contemplating the Ancients: Aesthetic and Social Issues in Early Chinese Portraiture

philosophy-put together."

3. Osvald Siren, Gardens of China (New York: Ronald Press, 1949), 3, my (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990). On the historical background

and arts associated with the Orchid Pavilion gathering of 353, see Marshall

emphasis.

4. Very little research has been undertaken on art and the sumptuary laws

of China. See Craig Clunas, "The Regulation of Consumption and the Institution of Correct Morality by the Ming State," in Norms and the State, ed.

Chun-chieh Huang and Erik Ziircher (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1993), 39-49;

unfortunately, this does not cover architecture. However, in his book Fruitful

Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China (London: Reaktion Books, 1996),

51, Clunas argues that by its conspicuous absence from Ming dynasty sump-

tuary legislation, which otherwise "encompassed every aspect of material

culture that it was possible to view as an object of consumption, from garments to dwellings to furniture and tableware," gardens must have been

viewed "as being something conceptually allied to production, rather than as an

object of luxury consumption," hence not specifically regulated. Such study

extended into other periods of time has yet to be undertaken.

5. Siren (as in n. 3), iii.

6. Peng Yigang, Zhongguo gudian yuanlin fensi [Analysis of the traditional

Chinese garden] (Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe, 1986).

Stanislaus Fung's useful "Guide to Secondary Sources on Chinese Gardens,"

Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 18, no. 3 (July-Sept.

1998): 269-86, confirms this: Beijing-Chengde and the Jiangnan region

(Yangzhou-Suzhou-Nanjing-Hangzhou) dominate both Chinese and Western

Pei-sheng Wu, The Orchid Pavilion Gathering: Chinese Paintingfrom the University

of Michigan Museum of Art (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Art,

2000), vol. 1, 102-9, vol. 2, 43-46. For later illustrations of Tao Yuanming's

homestead, see Elizabeth Brotherton, "Beyond the Written Word: Li Gonglin's Illustrations to Tao Yuanming's Returning Home," Artibus Asiae 59, nos.

3-4 (2000): 225-63; and Susan Nelson, "Catching Sight of South Mountain:

Tao Yuanming, Mount Lu, and the Iconographies of Escape," Archives of Asian

Art 52 (2000-2001): 11-43. Each of these themes is rich in literary associations and linked to traditions of reclusion and political dissent. Unfortunately,

in all of this material nothing remains to reveal the authentic rudiments of

China's earliest garden designs.

15. From the considerable but fragmentary literature about the Wang River

Villa in art and verse, see 0 I (Wang Wei), in Bunjinga Suihen (Tokyo: Chuo

Koransha, 1974), vol. 1; and Roderick Whitfield et al., In Pursuit of Antiquity

(Princeton: Art Museum, Princeton University, 1969), 180-89, 199-211,

incorporating a translation by Chang Yin-nan and Lewis C. Walmsley of Wang

Wei's set of twenty poems.

16. On the sacred signification of the mountain, see Kiyohiko Munakata,

"Concepts of Lei and Kan-lei in Early Chinese Art Theory," 105-31, and

Lothar Ledderose, "The Earthly Paradise: Religious Elements in Chinese

Landscape Art," 165-83, in Theories of the Arts in China, ed. Susan Bush and

Christian Murck (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983); Rolf Stein, The

dong Province; no mention is made of Sichuan.

World in Miniature: Container Gardens and Dwellings in Far Eastern Religious

7. I am referring here to Sichuan as constituted for many centuries prior to

Thought, trans. Phyllis Brooks (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990); and

1998, after which a large eastern sector of the province was administratively

Kiyohiko Munakata, Sacred Mountains in Chinese Art (Chicago: Krannert Art

removed and designated as a special economic zone. For an account of

Museum; Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1991). Today, the Hosshoji

Sichuan's early cultural history, see Michael Nylan, "The Legacies of the

can be reconstructed only from texts. Perhaps the finest example that can be

Chengdu Plain," in Ancient Sichuan: Treasures from a Lost Civilization, ed.

reconstructed from actual archaeological remains, excavated from 1954 to

Robert Bagley (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum; Princeton: Princeton University

1958, is the Motsuji in Hiraizumi, an early-12th-century construction by the

Press, 2001), 309-23.

Fujiwara family in its waning years, and especially Motsuji's subtemple Enryuji,

8. Translation adapted from Arthur Waley; for the full poem, see which follows a pattern very similar to that of Hosshoji; see Fujishima Ganjiro,

Waley, The Poetry and Career of Li Po (701-762) (London: Allen and Unwin,

Hiraizumi: Chusonji, Motsuji no zenjo (Hiraizumi-cho: Chusonji and Motsuji,

1950), 38-40.

1986). The finest surviving example of this type is undoubtedly the famous

9. See Lu You's remarkable account of his five-month journey in 1170

Phoenix Hall (Hoodo) of the Byodoin in Uji, southeast of Kyoto.

writing; in Chinese, a few publications can be found for the Lingnan (Guangzhou) area, and singular publications appear for Taiyuan, Wuhan, and Shan-

This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Fri, 17 Apr 2020 15:44:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

226 ART BULLETIN JUNE 2004 VOLUME LXXXVI NUMBER 2

17. See Masao Hayakawa, The Garden Art of Japan (New York: Weatherhill;

Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1973), 34-37, fig. 76; and Bunji Kobayashi, Japanese Architecture (Tokyo: Sagami Shobo, 1957), pl. 42. For a textbook account of this era,

in English, see Alexander Soper, "Domestic Architecture of the Kamakura

Period," in The Art and Architecture ofJapan, by Robert Treat Paine and Soper,

ledge near his pond. But, based on Wen Zhengming's painting, we cannot

know how large it was or what it looked like. Artists, who were either painting

their own garden or a close friend's, emphasized the meaning of the garden

not its appearance. Ming scholar-officials were more concerned with the ideas

in a garden than physical attributes."

27. The most influential of all studies of Suzhou gardens has now been

rev. ed. (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1975), 407-14. For a slightly earlier,

translated into English: Liu Dunzhen, Chinese Classical Gardens of Suzhou, trans.

Heian-period example, see the scaled model of the shinden-style Fujiwara

Chen Lixian (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992).

family residence, the Tosanj6den, in Bunji Kobayashi, pl . 37.

28. For literature on state temples (mingtang), quasi observatories with

18. See The I Ching [ Yijing] or Book of Changes, trans. Richard Wilhelm

and Cary F. Baynes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), 200- astrological functions, emphatic seasonal, monthly, and complex numerical

associations that court advisers argued passionately and sometimes endlessly

204, 652-56. James Hargett, "Huizong's Magic Marchmount: The

Genyue Pleasure Park of Kaifeng," Monumenta Serica 38 (1988-89): 8,

describes this trigram as the "symbol for a son and, by extension, for

male fertility."

19. The largest of Huizong's rocks, brought to the capital in 1123,

required a special boat, new water gates, bridges, and city walls to be

constructed, and called for one thousand laborers to complete thejob. See

Hargett (as in n. 18), 12; also, James Hargett, "The Pleasure Parks of

Kaifeng and Lin'an during the Song (960-1279)," Chinese Culture 30, no.

1 (Mar. 1989): 61-78.

20. Craig Clunas, 1996 (as in n. 4), 75, writes, "Although modern writers

have often concentrated on the cosmological connections of rocks, and their

links with deeply held views about the nature of the universe, Ming writers are

as likely to associate them with the luxury consumption of the age." Most of

these Ming examples, more precisely, represented writers disassociating them-

selves from the luxury consumers of their day, antisnob snobs perhaps,

whatever their own actual economic practices may have been. See also the

numerous entries for "rocks" indexed in Clunas, Superfluous Things: Material

Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China (Urbana, Ill.: University of

over, and their successors down to the present day struggled to reconstruct or

merely understand, see Edward Soothill, Hall of Light: A Study of Early Chinese

Kingship (London: Lutterworth Press, 1951); and Nancy Steinhardt, "The Han

Ritual Hall," in Chinese Traditional Architecture (New York: China Institute,

1984), 70-77. See also Alexander Soper, "The 'Dome of Heaven' in Asia," Art

Bulletin 24 (1947): 225-48.

29. Rhyming in the original ("Emei Tianxia xiu / Qingcheng Tianxia yu /

Jianmen Tianxia xian / Kuimen Tianxiajian"), Sichuan's (anonymous) logo

poem names the province's four most famous sites, all of them dark and

dangerous, including theJianmen (Sword Gate) Pass ("so narrow that a single

swordsman could hold off an army of ten thousand"), which leads into the

Chengdu Plain from the north, and ending with the Yangzi River's Kuimen

Gorge (Fig. 2), which leads into the province from the east: "Mt. Emei, most

luxuriant place on earth / Mt. Qingcheng, most secluded place on earth /

Jianmen Pass, most dangerous place on earth / Kuimen Gorge, most heroic

place on earth."

30. Indicative of his lack of exposure to Sichuan architecture, the mod-

ern founder of Chinese architectural history, Liang Sicheng, makes no

mention of chuandou in the volume that summarized his pioneering

Chicago Press, 1991).

21. For the Chinese classic on the connoisseurship of stones, see Tu Wan's

career, A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: A Study of the Development of

Stone Catalogue of Cloudy Forest, trans. Edward Schafer (Berkeley: University of

Its Structural System and the Evolution of Its Types (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

California Press, 1961). Among the excellent emergent contemporary works

on "scholar's stones," see especiallyJohn Hay, Kernels of Energy, Bones of Earth:

The Rock in Chinese Art (NewYork: China House Gallery, 1985); Robert Mowry,

Worlds within Worlds: The Richard Rosenblum Collection of Chinese Scholars' Rocks

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Art Museums, 1997); David Sensabaugh, "Fragments of Mountain and Chunks of Stone: The Rock in the

Chinese Garden," Oriental Art 44, no. 1 (spring 1998): 18-27; and Stephen

Little, Spirit Stones of China: The Ian and Susan Wilson Collection of Chinese Stones,

Paintings, and Related Scholars' Objects (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago;

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). On the depiction of gardens

and garden stones in painting, see, for example, Keswick (as in n. 1), chap. 5,

"The Painter's Eye"; Jan Stuart, "Ming Dynasty Gardens Reconstructed in

Words and Images," Journal of Garden History 10, no. 3 (1990): 162-72;June Li

andJames Cahill, Paintings of Zhi Garden by ZhangHong: Revisiting a Seventeenth-

Century Chinese Garden (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art,

1996); Robert Harrist, Painting and Private Life in Eleventh-Century China:

Mountain Villa by Li Gonglin (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998); and

Philip Hu, "The Shao Garden of Mi Wanzhong (1570-1628): Revisiting a Late

Ming Landscape through Visual and Literary Sources," Studies in the History of

Press, 1984). But evidence of chuandou's antiquity does appear there,

unlabeled, in Liang's drawing, fig. 14, of a ceramic house model from a

Han dynasty tomb, lst-2nd century c.E., from Changsha, which then as

now lay one province to the east of Sichuan. Evidence of chuandou architecture's still more ancient roots in Sichuan itself is found in a cluster of

houses from about 1000 B.C.E. from Shi'erqiao, where Chengdu now

stands, whose long end beams (drilled at regular horizontal intervals) and

planks of wood, walls of bamboo, and straw roofs were sufficiently well

preserved when excavated in the late 1980s to permit a reasonable recon-

struction; see "Chengdu Shi'erqiao Shangdai jianzhu yizhi diyiqi fajue

jianbao" [Preliminary report on the excavation of the first-period architectural remains from the Shang Dynasty at Shi'erqiao, Chengdu], Wenwu

379, no. 12 (Dec. 1987): 1-23, fig. 11, pl. 2.1; and Jay Xu, "Sichuan before

the Warring States Period," in Bagley (as in n. 7), 34-35, fig. 10.

31. This curvature becomes increasingly pronounced as one travels south

from Chengdu toward Yunnan Province, suggesting Southeast Asian origins.

32. In 2001, retracing the ancient path of Emperor Minghuang's (r. 71356) famous flight from insurrectionist troops in 756 from the northern capital

at Chang'an into Sichuan, I observed these decorative ridge tiles suddenly

Gardens and Designed Landscapes 19, nos. 3-4 (July-Dec. 1999): 314-42. On

the literary lore of rocks, see Judith T. Zeitlin, "The Secret Life of Rocks:

Objects and Collectors in the Ming and Qing Imagination," Orientations 30,

begin to appear within the first five miles or so south of the Shaanxi-Sichuan

border and thereon continue with great regularity. Rarely in architecture

no. 5 (May 1999): 40-47.

does regionalism so closely approximate political boundaries.

33. Noboru Kawazoe, in Kenzo Tange, Noboru Kawazoe, and Yoshio Wa-

22. This particular scene is re-created in the Astor Court of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, but minus the rock and thus without the most

tanabe, Ise: Prototype of Japanese Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press,

1965), 168.

important point. See Alfreda Murck and Wen Fong, "A Chinese Garden

Court: The Astor Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art," Metropolitan

Museum of Art Bulletin 38, no. 3 (winter 1980-81): 1-64 (in particular, cover

photograph and fig. 31).

23. In the Garden of the Master of Fishing Nets, the view from the main hall

to the central lake is blocked by a two-story-tall pile of rocks, turning the eye

instead to the narrow, shaded, "backyard," which in turn focuses attention on

the garden's signature (net-shaped) lattice windows. This rock pile is referred

to by name as the Barrier of Clouds, transforming yanginto yin. A second-story

library must be accessed outdoors by yet another pile of "clouds." A rare,

black-painted wall serves as a night sky, turning an open moon-gate into a

white shining orb, beside which is planted a cassia tree, Chinese symbol of the

moon (the largest rock of all). A half dozen other "tricks" become apparent,

but perhaps only on one's fourth or fifth visit to the garden.

24. Lothar Ledderose, "Building Blocks, Brackets, and Beams," chap. 5 in

Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 2000).

25. For the handscroll by Ni Zan and Zhao Yuan, see Osvald Siren, Chinese

Painting, Leading Masters and Principles (London: Lund, Humphries, 1958),

vol. 6, pl. 102. For Wen Zhengming's 1551 album of eight leaves, now in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art, see Whitfield et al. (as in n. 15), 66-75; and

Richard Edwards et al., The Art of Wen Cheng-ming (1470-1559) (Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Museum of Art, 1976), entry no. 51.

26. A study of some of Wen Zhengming's Zhuozheng Garden illustrations

has ledJan Stuart (as in n. 21), 171, to conclude, "The only evidence that Wen

Zhengming's album can provide about the physical appearance of the

[Zhuozheng Garden] is that [owner] Wang Xianchen must have had a rock

34. For discussion of some of Du Fu's renowned poems on the horse

paintings of his day, especially those by Cao Ba (act. mid-8th century) and

Han Gan (ca. 715-after 781), who were said to set the standard for all time,

see Wang Bomin, ed., Li Bo, Du Fu lun hua shi sanji [Miscellaneous notes on

poems by Li Bo and Du Fu about painting] (Shanghai: Xiling yinshe, 1983),

78-90;Joseph Lee, "Tu Fu's Art Criticism and Han Kan's Painting," Journal of

the American Oriental Society 90, no. 3 (July-Sept. 1970): 449-61; and David

Hawkes, A Little Primer of Tu Fu (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), 133-44.

35. Several similarly constructed buildings still exist from that moment in

time, little altered despite periodic reconstructions, including the sutra re-

pository and belfry in the main compound of Horyuji's west precinct,

Kairyuoji's west Kondo (Nara), and the Tegaimon from Todaiji (also Nara).

See Mary Neighbour Parent's detailed study The Roof in Japanese Buddhist

Architecture (New York: Weatherhill; Tokyo: Kaijima, 1983), 28-32, 44-47.