Aliza S. Wong - Race and the Nation in Liberal Italy, 1861-1911 Meridionalism, Empire, and Diaspora (Italian & Italian American Studies) (2006)

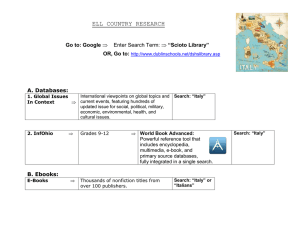

advertisement