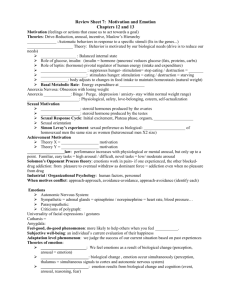

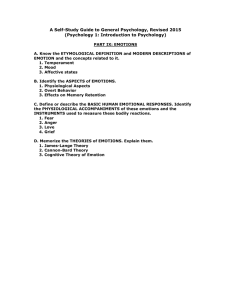

CHAPTER 10 MOTIVATION AND EMOTION Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly When your clock goes off in the morning, do you jump out of bed, eager to face the day, or do you bury your head in the blankets? Once you’re at your job or on campus, do you always do your best, or do you work just hard enough to get by? Are you generally happy? Do you sometimes worry or feel sad? In this chapter, we explore the physical, mental and social factors that motivate behaviour in areas ranging from eating to sexuality to achievement. We also examine what emotions are and how they are expressed. LEARNING OBJECTIVES On completion of this chapter, you should be able to: 10.1 describe the different theories of motivation 10.2 understand the control of hunger and eating 10.3 understand human sexual behaviour 10.4 outline the importance of achievement in goal setting 10.5identify the roles of social and cultural influences on emotion 10.6 describe the different theories of emotion 10.7 outline the role of emotion in communication. APPLYING PSYCHOLOGY 1 Do people tend to eat less or more depending on how the people around them are eating? 2 Is changing lifestyle factors such as eating habits and exercise patterns useful in effectively losing weight? 3 Is it possible to enhance people’s achievement motivation through childhood training and even later in life? Express 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 476 Bring your learning to life with interactive study and exam preparation tools that support your textbook. CourseMate Express includes quizzes, videos, concept maps and more. 26/07/17 11:20 AM 477 Introduction PSYCHOLOGICAL LITERACY AND GRADUATE ATTRIBUTES (GAs) ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ● this chapter, you would challenge any of the following statements, rather than accepting them at face value: The main signals for hunger and satiety come from the stomach. Children raised by homosexual parents are more likely to be homosexual themselves. The main problem with obese people is their lack of willpower. Significant positive events such as winning a lottery lead to a lasting increase in happiness. Polygraph lie detector tests are highly accurate. Facial expressions across the world convey the same emotions. Will you feel morally obliged to use your communication and interpersonal skills (GA5) to convince the person who made such statements that they need to rethink them, in light of what is known about motivation and emotion? If that person is you, will you have the motivation to update your opinion or misconception in light of your new knowledge? These dispositions are a crucial component of psychological literacy. ly In this chapter you are introduced to the topics of motivation and emotion, specifically: (GA 1) Discipline knowledge and its application: This chapter introduces you to the major theories, methods and findings regarding the complex topics of motivation and emotion. What factors drive our behaviour? What purposes do emotions serve? (GA 2) Research methods: This chapter introduces a variety of research methods utilised in the study of motivation and emotion, such as twin studies of sexual orientation, and facial micro-expressions in lie detection. The ‘Focus on research methods’ section first asks whether and how a methodologically sound survey of human sexual behaviour can be undertaken, and then reports the results and limitations of the research. (GA 3) Critical and creative thinking: The ‘Thinking critically’ section considers whether human sexual orientation is genetically based. In terms of GA4 (values and ethics) and GA6 (learning and application), we ask you whether, knowing something about the nature of motivation and emotion after reading ● INTRODUCTION Every March, thousands of Australians participate in the World’s Greatest Shave, an event in which they shave, colour or wax their hair to raise funds for the Leukaemia Foundation (see the Snapshot ‘Is shaving your head “brave?”’). The money raised provides service for patients and their families, and primarily supports research into blood cancer treatment. Individuals endure the effects of their participation, both socially and personally, for several months afterwards as a result of the change in their appearance. So why do so many people undergo this experience for seemingly no self-benefit? This is a question about motivation, the factors that influence the initiation, direction, intensity and persistence of behaviour (Reeve, 1996). Like the study of how people and other animals behave and think, the puzzle of why they do so has intrigued psychologists for many decades. Why do we help others or ignore them, eat what we want or stick to a diet, visit art museums or hang out in sleazy bars, attend university or drop out of high school? Why, for that matter, do any of us do whatever it is that we do? Psychologists who study motivation have noticed that behaviour is based partly on the desire to feel certain emotions, such as the joy that comes with winning a contest or climbing a mountain or becoming a parent. They’ve also found that motivation affects emotion, as when hunger makes you irritable. In short, motivation and emotion are closely intertwined. Let’s consider what psychologists have learned so far about motivation and emotion. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 477 CHAPTER OUTLINE ●● ●● ●● ●● ●● ●● ●● Concepts and theories of motivation Hunger and eating Sexual behaviour Achievement motivation The nature of emotion Theories of emotion Communicating emotion motivation the influences that account for the initiation, direction, intensity and persistence of behaviour 26/07/17 11:20 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Is shaving your head ‘brave’? Snapshot Suppose that a man works two jobs, refuses party invitations, wears old clothes, drives a beat-up car, eats food that others leave behind at lunch, never gives to charity, and keeps his house at 15 degrees Celsius in the dead of winter. To explain why he does what he does, you could propose a separate reason for each of his behaviours, or you could suggest a motive, a reason or purpose that provides a single explanation for this man’s diverse and apparently unrelated behaviours. That unifying motive might be his desire to save as much money as possible. This example illustrates the fact that motivation cannot be observed directly. We have to infer, or presume, that motivation is present from what we can observe. So psychologists think of motivation, whether it be hunger or thirst or love or greed, as an intervening variable – something that is used to explain the relationships between environmental stimuli and behavioural responses. The three different responses shown in Figure 10.1, for example, can be understood as being guided by a single unifying motive: thirst. In order to be considered a motive, an intervening variable must have the power to change behaviour in some way. For example, suppose that we arrange for some party guests to eat only salted peanuts and other guests to eat only unsalted peanuts. The people who ate salted peanuts would probably drink more than those who ate the unsalted nuts. In this situation, we can use the motive known as thirst to explain the observed differences in drinking. Figure 10.1 shows that motives can help explain why different stimuli can lead to the same response and why the same stimulus can elicit different responses. Motivation also helps explain why behaviour varies over time. For example, many people cannot manage to lose weight, quit smoking or exercise until they have a heart attack or symptoms of other serious health problems. At that point, these people may suddenly start to eat a healthier diet, work out regularly and give up tobacco (Keenan, 2009; West & Sohal, 2006). In other words, because of changes in motivation, particular stimuli – such as ice-cream, cigarettes and health clubs – trigger different responses at different times. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On These two 11-yearold girls decided to raise money for the World’s Greatest Shave, an event which supports research into blood cancers. What were their motivations for doing so when having no hair at such an age may open them up to all sorts of negative perceptions by others, particularly their peers? 10.1 CONCEPTS AND THEORIES OF MOTIVATION ly 478 motive a reason or purpose for behaviour FIGURE 10.1 Motives as intervening variables Motives can explain the links between stimuli and responses that in some cases might seem unrelated. In this example, inferring the motive of thirst provides an organising explanation for why each stimulus triggers the responses shown. Dry mouth Drinking from a water fountain Dry mouth Salty food Stopping to purchase a soft drink Salty food Perspiration following exercise 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 478 Noticing an outdoor ad for orange juice Perspiration following exercise Drinking from a water fountain Thirst Stopping to purchase a soft drink Noticing an outdoor ad for orange juice 26/07/17 11:20 AM 479 10.1 Concepts and theories of motivation Sources of motivation Snapshot In the woodland of East Africa, vervet monkeys use alarm calls to signal the threat of predators to the other individuals in the troop. For example, if a leopard is approaching, they bark; when an eagle is visible, they cough. The instinct doctrine and its descendants In the early 1900s, many psychologists explained motivation in terms of the instinct doctrine, which highlights the instinctive nature of behaviour. Instinctive behaviours are automatic, involuntary behaviour patterns that are consistently triggered, or ‘released’, by particular stimuli (Tinbergen, 1989). Such behaviours, originally called fixed-action patterns, are unlearned, species-typical responses to specific ‘releaser’ stimuli. For example, releaser stimuli such as a male bird’s coloured plumage and behaviour can cause a female bird of the same species to join him in a complex mating dance (see the Snapshot ‘Fixed-action patterns’). Early theories In 1908, William McDougall listed 18 human instinctive behaviours, including self-assertion, reproduction, pugnacity (aggressiveness) and gregariousness (sociability).Within a few years, McDougall and others had named more than 10 000, prompting one critic to suggest that his colleagues had ‘an instinct to produce instincts’ (Bernard, 1924). The problem was that instincts had become labels that did little more than describe behaviour. Saying that someone gambles because of a gambling instinct or works hard because of a work instinct explains nothing about how these behaviours develop or why they appear in some people and not others. Applying the instinct doctrine to human motivation also seemed problematic because people display few, if any, instinctive fixed-action patterns. Today, psychologists continue to investigate the role of inborn tendencies in human motivation. Their work has been inspired partly by findings that a number of human behaviours are present at birth. Among these are sucking and other reflexes, certain facial expressions such as grimacing at bitter tastes (Steiner et al., 2001), and as described in Chapter 5, ‘Learning’, a tendency towards learning to fear snakes and other potential dangers (Öhman & Mineka, 2003). But psychologists’ thinking about instinctive behaviours is more sophisticated now than it was a century ago. These inborn tendencies are now viewed as more flexible than early versions of instincts. So-called fixed-action patterns – even 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 479 iStock.com/Biscut Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly The number of possible motives for human behaviour seems endless, but psychologists have found it useful to organise them into four somewhat overlapping categories: 1 Human behaviour is motivated by basic physiological factors, such as the need for food and water. 2 Emotional factors are another source of motivation. Panic, fear, anger, love and hatred can influence behaviour ranging from selfless giving to brutal murder. 3 Cognitive factors can motivate behaviour. People behave in certain ways – becoming arrogant or timid, for example – partly because of these cognitive factors, which include their perceptions of the world, their beliefs about what they can or cannot do, and their expectations about how others will respond to them. Cognitive factors help explain why it is that some of the least musical contestants who try out for talent shows, such as X Factor and Australia’s Got Talent, seem utterly confident in their ability to perform. 4 Motivation may stem from social factors, including the influence of parents, teachers, siblings, friends, television and other sociocultural forces. Have you ever bought a jacket or tried a particular hairstyle not because you liked it but because it was in fashion? This is just one example of how social factors can affect almost all human behaviour. Various combinations of all four of these motivational sources appear in four prominent theories of human motivation. None of these theories can fully explain all aspects of why we behave as we do, but each of them – the instinct doctrine, drive reduction theory, arousal theory and incentive theory – helps tell part of the story. Fixedaction patterns instinct doctrine a view that explains human behaviour as motivated by automatic, involuntary and unlearned responses instinctive behaviours innate, automatic dispositions towards responding in a particular way when confronted with a specific stimulus 26/07/17 11:21 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Evolution at work? Snapshot Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On The marriage of Donald Trump to Melania KnaussTrump, a former model who is 24 years his junior, illustrates the worldwide tendency for older men to often prefer younger women and for younger women to prefer older men. This tendency has been interpreted as evidence supporting an evolutionary explanation of mate selection, but sceptics see social and economic forces at work in establishing these preference patterns. the simple ones, such as baby chicks pecking for seeds – vary quite a bit among individuals and can be modified by experience (Deich, Tankoos & Balsam, 1995). Therefore, these tendencies are now often referred to as modal action patterns. Psychologists also recognise that even though certain behaviours reflect inborn motivational tendencies, those behaviours may or may not actually appear, depending on each individual’s experience. So although we might be biologically prepared to learn to fear snakes, that fear won’t develop if we never see a snake. In other words, inherited tendencies can influence motivation, but that doesn’t mean that all motivated behaviour is genetically determined. It can still be shaped, amplified or even suppressed by experience and other factors operating in particular individuals. Psychologists who take an evolutionary approach to behaviour suggest that a wide range of behavioural tendencies have evolved partly because over the centuries, those tendencies were adaptive for promoting individual survival in particular circumstances. The individuals who possessed these behavioural tendencies and expressed them at the right times and places were the ones who were more likely than others to survive to produce offspring. As the descendants of those ancestral human survivors, our ancestors’ behavioural tendencies were transmitted genetically, and thus we may have inherited similar tendencies. Evolutionary psychologists also argue that many aspects of human social behaviour, such as helping and aggression, are motivated by inborn factors – especially by the desire to maximise our genetic contribution to the next generation (Buss, 2004a). ly 480 The instinct doctrine and mate selection The evolutionary approach suggests, for example, that people’s choice of a marriage partner or sexual mate is influenced by the consequences of the choices made by their ancestors over countless generations. For instance, research across generations in many different cultures shows that both men and women express a strong preference for a partner who is dependable, emotionally stable and intelligent – all characteristics associated with creating a good environment for having and raising children (Buss et al., 1990). Craig Barritt/Getty Images Sex differences in mate preference 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 480 Some evolutionary psychologists also point to sex differences in mating preferences and strategies. They argue that because women can produce relatively few children in their lifetimes, they are more psychologically invested than men in the survival and development of those children. This greater investment is said to motivate women to be choosier than men when selecting mates. So although women tend to prefer athletic men with symmetrical (‘handsome’) faces and deep voices, this preference is strongest at the point in the menstrual cycle when fertility peaks and mating with these ‘genetically fit’ men would most likely result in pregnancy (Barber, 1995; Gangestad et al., 2007; Garver-Apgar, Gangestad & Thornhill, 2008; Puts, 2005). More generally, say evolutionary psychologists, women are drawn to men whose intelligence, maturity, ambition and earning power demonstrate the ability to amass resources and mark them as ‘good providers’ who will help raise children and ensure their survival (see the Snapshot ‘Evolution at work’). It takes some time to assess these resource-related characteristics (He drives an expensive car, but can he afford it?), which is why, according to the evolutionary view, women are more likely than men to prefer a period of courtship prior to mating. Men tend to be less selective and to want to begin a sexual relationship sooner than women (Buss, 2004b; Buss & Schmitt, 1993) because compared with their female partners, they have little to lose from doing so. On the contrary, their eagerness to engage in sex early in a relationship is seen as reflecting their evolutionary ancestors’ tendency towards opportunistic sex as a means of maximising their genetic contribution to the next generation. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that the desire to produce as many children as possible motivates males’ attraction to women whose fertility and good health are signalled by factors generally associated with physical beauty, such as clear skin and a low waist-to-hip ratio (Buss, 2009). 26/07/17 11:21 AM 481 10.1 Concepts and theories of motivation These ideas have received some support. For instance, preference ratings from several thousand people in more than three dozen cultures reveal that males generally prefer physical attractiveness and good health in prospective mates and that females generally prefer mates with higher levels of social status and financial resources (Shackelford, Schmitt & Buss, 2005). This sex difference is reflected, too, in the fact that men are far more likely than women to specify body type preferences in Internet personals ads (Glasser et al., 2009). Cultural considerations Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Critics argue that such preferences stem from cultural traditions, not genetic predispositions. The traditional roles of Australian Aboriginal women are evident in early pictures depicting foodgathering tasks, as opposed to the roles of Aboriginal men, who hunted larger animals. It was the role of women to collect vegetables and fruits, grind seeds, dig for roots and cook damper (Berndt & Berndt, 1996). Similarly, Māori women were responsible for food preparation and handling tasks like weaving (Heuer, 1969). The fact that women have been systematically denied economic and political power in many cultures may account for their tendency to rely on the security and economic power provided by men (Eagly, Wood & Johannesen-Schmidt, 2004; Silverstein, 1996). Indeed, an analysis of data from 37 cultures showed that women valued potential mates’ access to resources far more in cultures that sharply limited women’s reproductive freedom and educational opportunities (Kasser & Sharma, 1999). Evolutionary theorists acknowledge the role of cultural forces and traditions in shaping behaviour (as discussed in Chapter 16, ‘Culture and psychology’), but they ask whether evolutionary factors might contribute to the appearance of these forces and traditions, including the relative ease with which certain gender roles and mate preferences emerge (Geher, Camargo & O’Rourke, 2008; Hrdy, 1997, 2003; Swami & Furnham, 2008). Drive reduction theory Like the instinct doctrine, drive reduction theory emphasises internal factors, but it is based on the concept of homeostasis. Homeostasis is the tendency to keep physiological systems at a steady level, or equilibrium, by constantly making adjustments in response to change – much as a thermostat functions to maintain a constant temperature in a house. We describe a version of this concept in Chapter 3, ‘Biological aspects of psychology’, in relation to feedback loops that keep hormones at desirable levels. According to drive reduction theory, any imbalances in homeostasis create needs, which are biological requirements for wellbeing. The brain responds to needs by creating a psychological state called a drive – a feeling of arousal that prompts an organism to take action, restore the balance, and as a result, reduce the drive (Hull, 1943). For example, if you have had no water for some time, the chemical balance of your body fluids is disturbed, creating a biological need for water. One consequence of this need is a drive – thirst – that motivates you to find and drink water. After you drink, the need for water is met, so the drive to drink is reduced. In other words, drives push people to satisfy needs, thereby reducing the drives and the arousal they create (see Figure 10.2). Early drive reduction theorists made a distinction between two types of drives. The first kind, called primary drives, stems from inborn physiological needs, such as for food or water, that people do not have to learn (Hull, 1951). The second kind, known as secondary drives, is learned through experience. They motivate us to act as if we have unmet basic needs. For example, as people learn to associate money with the ability to buy things to satisfy primary drives for food, shelter and so on, having money becomes a secondary drive. Having too little money then motivates many behaviours – from hard work to stealing – to obtain more funds. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 481 drive reduction theory a theory of motivation stating that motivation arises from imbalances in homeostasis homeostasis the tendency for organisms to keep their physiological systems at a stable, steady level by constantly adjusting themselves in response to change needs biological requirements for wellbeing that are created by an imbalance in homeostasis drive a psychological state of arousal created by an imbalance in homeostasis that prompts an organism to take action to restore the balance and reduce the drive primary drives drives that arise from basic biological needs secondary drives drives that arise through learning and can be as motivating as primary drives 26/07/17 11:21 AM 482 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion FIGURE 10.2 Drive reduction theory and homeostasis The mechanisms of homeostasis, such as the regulation of body temperature or food and water intake, are often compared to thermostats. If the temperature in a house drops below the thermostat setting, the heating comes on and brings the temperature up to that preset level, achieving homeostasis. When the temperature reaches the preset point, the heating shuts off. Need (biological disturbance) Unbalanced equilibrium Drive (psychological state that provides motivation to satisfy need) Equilibrium restored Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Arousal theory ly Behaviour that satisfies need and reduces drive physiological arousal a general level of activation that is reflected in several physiological systems arousal theory a theory of motivation stating that people are motivated to behave in ways that maintain what is for them an optimal level of arousal Drive reduction theory can account for a wide range of motivated behaviours. But humans and other animals are also motivated to do things that don’t appear to reduce drives. Consider curiosity. People, rats, monkeys, dogs and many other creatures explore and manipulate their surroundings, even though these activities do not lead to drive reduction (Bergman & Kitchen, 2009; Hughes, 2007; Kaulfuss & Mills, 2008). They will also exert considerable effort simply to enter a new environment, especially if it is complex and full of new or unusual objects (Loewenstein, 1994). We go to a new shopping centre, watch builders work, surf the Internet and travel the world just to see what there is to see. Some of us also go out of our way to ride roller-coasters, skydive, drive race cars and do countless other things that, like curiosity-motivated behaviours, do not reduce any known drive. In fact, these behaviours cause an increase in physiological arousal, a general level of activation that is reflected in the state of several physiological systems, including the brain, heart, lungs and muscles (Plutchik & Conte, 1997). The realisation that we sometimes act in ways that increase arousal and sometimes act in ways that decrease it has led some psychologists to argue that people are motivated to regulate arousal so that it stays at roughly the same level most of the time. Specifically, according to arousal theory, we are motivated to behave in ways that maintain or restore an ideal, or optimal, level of arousal (Hebb, 1955). In other words, we try to increase arousal when it is too low and decrease it when it is too high. So after a day of boring chores, you may want to see an exciting movie, but if your day was spent playing football, debating a political issue or helping a friend move, an evening of quiet relaxation may seem ideal. What level of arousal is enough? Where is the optimal level of arousal? In general, people perform best, and may feel best, when arousal is moderate (Teigen, 1994; see Figure 10.3). Too much arousal can hurt performance, as when test anxiety interferes with some students’ ability to recall what they have studied, or when some athletes ‘choke’ so badly that they miss an easy catch or a simple shot at goal (Mesagno & Marchant, 2013). Underarousal, too, can cause problems, as you probably know if you have ever tried to work, drive or study when you are sleepy. So the optimal level of arousal lies somewhere between these extremes, but exactly where that level is can vary from person to person. People whose optimal arousal is relatively high try to keep it there, so they are more likely than other people to smoke, drink alcohol, engage in frequent sexual activity, listen to loud music, eat spicy foods and do things that are novel 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 482 26/07/17 11:21 AM 483 10.1 Concepts and theories of motivation and risky (Farley, 1986; Zuckerman, 1979, 1996); see the Snapshot ‘Arousal and personality’. The resulting increase in arousal activates brain regions associated with reward (Joseph et al., 2009).Those with relatively low optimal arousal try to keep it low, so they tend to take fewer risks and behave in ways that are not overly stimulating. Most of these differences in optimal arousal have a strong biological basis and, as discussed in Chapter 13, ‘Personality’, may help shape other characteristics, such as whether we tend to be introverted or extraverted (Eysenck, 1990). According to arousal theory, boldness, shyness and other personality traits and behavioural tendencies reflect individual differences in the level of arousal that people find ideal for them. As described in Chapter 13, ‘Personality’, differences in arousal arise largely from inherited differences in the nervous system (Eysenck, 1990). Deep sleep Increasing emotional disturbances, anxiety Point of waking Level of arousal Easy task Difficult task Shutterstock.com/Henrique Daniel Araujo Optimal level Increasing alertness, interest, positive emotion Efficiency of performance Efficiency of performance Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Notice in part A that performance is poorest when arousal is very low or very high, and best when arousal is at a moderate level. When you are either sleepy or overly excited, for example, it may be difficult to think clearly or to be physically coordinated. In general, optimal performance comes at a lower level of arousal on difficult or complex tasks and at a higher level of arousal on easy tasks, as shown in part B. Even a relatively small amount of overarousal can cause students to perform far below their potential on difficult tests (Sarason, 1984). Because animal research early in this century by Robert Yerkes and his colleagues provided supportive evidence, this arousal–performance relationship is sometimes referred to as the Yerkes–Dodson law, even though Yerkes never actually discussed performance as a function of arousal (Teigen, 1994). Snapshot ly FIGURE 10.3 The arousal–performance relationship Arousal and personality Level of arousal General relationship between performance and arousal level Relationship between performance and arousal level on difficult vs easy tasks (A) (B) Incentive theory Instinct, drive reduction and arousal theories of motivation all focus on internal processes that prompt people to behave in certain ways. By contrast, incentive theory is a theory of motivation stating that behaviour is directed towards attaining desirable stimuli and avoiding unwanted stimuli. Incentive theory emphasises the role of external stimuli that can motivate behaviour by pulling us towards them or pushing us away from them. More specifically, people are said to behave in order to get positive incentives and avoid negative incentives. According to incentive theory, then, differences in behaviour from one person to another, or in the same person from one situation to another, can be traced to the incentives available and the value a person places on them at the time. If you expect that some behaviour (such as buying a lottery ticket or apologising for a mistake) will lead to a valued outcome (winning money or reducing guilt), you will be motivated to engage in that behaviour (Bastian, Jetten, & Fasoli, 2011; Cooke et al., 2011). The value of an incentive is influenced by physiological as well as cognitive and social factors – or as drive reduction theorists might put it, by both primary and secondary drives. For example, food is a more motivating incentive when you are hungry than when you are full (Chein et al., 2011; DeVoe & Iyengar, 2010). As for cognitive and social influences, notice that the value of some things we eat 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 483 incentive theory a theory of motivation stating that behaviour is directed towards attaining desirable stimuli and avoiding unwanted stimuli 26/07/17 11:21 AM 484 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion and drink – such as communion wafers or protein shakes – isn’t determined by hunger but by what we have learned in our culture about spirituality, health or attractiveness. Wanting and liking Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly It may seem obvious that people are motivated to approach things they like and to avoid things they don’t like, but the story of incentive theory is not quite that simple. Psychologists have found that people sometimes work hard for some incentives only to find that they don’t enjoy having them nearly as much as they thought they would (Gilbert, 2006). Furthermore, motivation theorists have highlighted the distinction between wanting and liking. Wanting is the process of being attracted to incentives, whereas liking is the immediate evaluation of how pleasurable a stimulus is (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2008). Studies with laboratory animals have shown that these two systems involve activity in different parts of the brain, and they involve different neurotransmitters (Peciña, 2008). For example, the wanting system appears to be activated by dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with experiencing the pleasure of sex, drugs and gambling. Some evidence for this idea comes from a study that found an unusual increase in compulsive gambling among people who had begun taking dopamine-enhancing drugs for Parkinson’s disease (Dodd et al., 2005). It appears, too, that the wanting system can compel behaviour to a far greater extent than the liking system does. For instance, the drug-seeking efforts made by addicted people are often far more intense than the actual pleasure of drug use (Robinson & Berridge, 2003). Furthermore, the operation of the wanting system, in particular, varies according to whether an individual has been deprived (Nader, Bechara & Van der Kooy, 1997). So although you might like pizza, your motivation to eat some would be affected by different brain regions, depending on whether the pizza is served at the start of a meal, when you are hungry, or at the end of a big meal, when you are full (Jiang et al., 2008). The theories of motivation we have outlined (see the section ‘In review: Concepts and theories of motivation’) complement one another. Each emphasises different sources of motivation, and each has helped guide research into motivated behaviours, including eating, sex and achievement-related activities, which are the topics of the next three sections. IN REVIEW Concepts and theories of motivation PHYSIOLOGICAL FACTORS DESCRIPTION Needs Food, water or sleep Emotional factors Feelings, such as happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise or disgust Cognitive factors Perceptions and beliefs about yourself and the consequences of your actions Social and environmental factors Influence of other people or situations THEORY MAIN POINTS Instinct doctrine Innate biology produces instinctive behaviour. Drive reduction theory Behaviour is guided by biological needs and learned ways of reducing drives arising from those needs. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 484 26/07/17 11:21 AM 485 10.2 Hunger and eating THEORY MAIN POINTS Arousal theory People seek to maintain an optimal level of physiological arousal, which differs from person to person. Maximum performance occurs at optimal arousal levels. Incentive theory Behaviour is guided by the lure of positive incentives and the avoidance of negative incentives. Cognitive factors influence expectations of the value of various rewards and the likelihood of attaining them. Check your understanding 1 Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly The fact that some people like roller-coasters and other scary amusement park rides has been cited as evidence theory of motivation. for the . 2 Evolutionary theories of motivation are modern outgrowths of theories based on , and factors. 3 The value of incentives can be affected by 10.2 HUNGER AND EATING At first glance, hunger and eating seem to be a simple example of drive reduction. You get hungry when you haven’t eaten for a while. Much as a car needs petrol, you need fuel from food. But what bodily mechanism acts as a ‘petrol gauge’ to signal your need for fuel? What determines which foods you eat, and how do you know when to stop? The answers to these questions involve interactions between the brain and the rest of the body, but they also involve learning, social and environmental factors (Hill & Peters, 1998; Pinel, Lehman & Assand, 2002). Biological signals for hunger and satiation A variety of mechanisms underlie hunger, the general state of wanting to eat, and satiation, the satisfaction of a need such as hunger. Satiation leads to satiety, the state in which we no longer want to eat. In order to maintain body weight, we must have ways of regulating food intake over the short term (a question of how often we eat and when we stop eating a given meal) and to regulate the body’s stored energy reserves (fat) over the long term. Signals from the stomach The stomach would seem to be a logical source of signals for hunger and satiety. After all, people say they feel ‘hunger pangs’ from an ‘empty’ stomach, and they complain of a ‘full stomach’ after overeating. It is true that the stomach does contract during hunger pangs, and that increased pressure in the stomach can reduce appetite (Cannon & Washburn, 1912; Houpt, 1994). But people who have lost their stomachs due to illness still get hungry when they don’t eat, and they still eat normal amounts of food (Janowitz, 1967). So stomach cues affect eating, but they do not play a major role in the normal control of eating.These cues appear to operate mainly when you are very hungry or very full. The small intestine, too, is involved in the regulation of eating (Maljaars et al., 2008). It is lined with cells that detect the presence of nutrients and send neural signals to the brain about the need to eat (Capasso & Izzo, 2008). Part of the signalling process even involves bacteria that normally live in a healthy gastrointestinal system. These ‘gut’ microorganisms generate chemicals in response to the food they encounter 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 485 hunger the general state of wanting to eat satiation the satisfaction of a need such as hunger satiety the condition of no longer wanting to eat LINKAGES How does your brain know when you are hungry? (a link to Chapter 3, ‘Biological aspects of psychology’) 26/07/17 11:21 AM 486 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion (Stilling, Dinan & Cryan, 2014). Psychologists are just starting to study this chemical signalling, but the process appears to have far-reaching consequences, affecting digestion and a desire to eat or stop eating, as well as influencing emotions, learning and stress responses (Cryan & Dinan, 2012; Li et al., 2009; Ridaura et al., 2013). Signals from the blood Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Still, most important signals about the body’s fuel level and nutrient needs are sent to the brain from the blood. The brain’s ability to ‘read’ bloodborne signals about the body’s nutritional needs was shown years ago when researchers deprived rats of food and then injected them with blood from rats that had just eaten. When offered food, the injected rats ate little or nothing (Davis et al., 1969); something in the injected blood of the well-fed animals apparently signalled the hungry rats’ brains that there was no need to eat. What sent that satiety signal? More recent research has shown that the brain constantly monitors both the level of food nutrients absorbed into the bloodstream from the stomach and the level of hormones released into the blood in response to those nutrients and from stored fat (Burdakov, Karnani, & Gonzalez, 2013; Parker & Bloom, 2012). The nutrients that the brain monitors include glucose (the main form of sugar used by body cells), fatty acids (from fats) and amino acids (from proteins). When the level of blood glucose drops, eating increases sharply (Chaput & Tremblay, 2009; Mogenson, 1976). The brain also monitors hormone levels to regulate hunger and satiety. For example, when a lack of nutrients is detected by the stomach, the hormone ghrelin is released into the bloodstream and acts as a ‘start eating’ signal when it reaches the brain (Pradhan, Samson & Sun, 2013). When glucose levels rise, the pancreas releases insulin, a hormone that most body cells need in order to use the glucose they receive. Insulin itself may also provide a satiety signal by acting directly on brain cells (Brüning et al., 2000; Lakhi, Snow & Fry, 2013). The hormone leptin (from the Greek word for ‘thin’) appears to be a key satiety signal to the brain (Feve & Bastard, 2012). Unlike glucose and insulin, whose satiety signals help us know when to end a particular meal, leptin appears to be involved mainly in the long-term regulation of body fat (Huang & Li, 2000). The process works like this: cells that store fat normally have genes that produce leptin. As the fat supply in these cells increases, leptin enters the blood and reduces food intake (Tamashiro & Bello, 2008). Mice with defects in these genes make no leptin and are obese (Bouret, Draper, & Simerly, 2004). When these animals are given leptin injections, though, they rapidly lose weight and body fat but not muscle tissue (Forbes et al., 2001). Leptin injections can also produce the same changes in normal animals (Priego et al., 2010). Some cases of human obesity are due to leptin dysregulation (for example, Müller et al., 2009), but for most of us, leptin is not a ‘magic bullet’ against obesity. Although leptin injections help those rare people whose fat cells make no leptin (Kelesidis et al., 2010), this treatment is far less effective in people who are obese due to eating a high-fat diet (Heymsfield et al., 1999). In these far more common cases of obesity, the brain appears to have become less sensitive to leptin’s satiety signals (for example, Lustig et al., 2004). Hunger and the brain Many parts of the brain contribute to the control of hunger and eating, but research has focused on several regions of the hypothalamus that may play primary roles in detecting and reacting to the blood’s signals about the need to eat. Some regions of the hypothalamus detect leptin and insulin; these regions generate signals that either increase hunger and reduce energy expenditure or else reduce hunger and increase energy expenditure (Créptin et al., 2014; Kanoski et al., 2013). At least 20 neurotransmitters and neuromodulators – substances that modify the action of neurotransmitters – convey these signals to networks in other parts of the hypothalamus and in the rest of the brain (Cota et al., 2006). 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 486 26/07/17 11:21 AM 487 10.2 Hunger and eating Activity in a part of the network that passes through the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus tells an animal that there is no need to eat. So if a rat’s ventromedial nucleus is electrically or chemically stimulated, the animal will stop eating (Kent et al., 1994). However, if the ventromedial nucleus is destroyed, the animal will eat continuously, increasing its weight up to threefold (see the Snapshot ‘One fat mouse’). The lateral hypothalamus contains networks that stimulate eating. When the lateral hypothalamus is electrically or chemically stimulated, rats eat huge quantities, even if they just had a large meal (Stanley et al., 1993). When the lateral hypothalamus is destroyed, however, rats stop eating almost entirely. Set point theory Snapshot After surgical destruction of its ventromedial nucleus, this mouse ate enough to triple its body weight. Such animals become picky eaters, choosing only foods that taste good and ignoring all others. Richard Howard Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Decades ago, these findings suggested that activity in the ventromedial and lateral areas of the hypothalamus interact to maintain some homeostatic level, or set point, based on food intake, body weight or other eating-related signals (Powley & Keesey, 1970). According to this application of drive reduction theory, normal animals eat until their set point is reached, then stop eating until desirable intake falls below the set point and hunger appears again (Cabanac & Morrissette, 1992). This theory turned out to be too simplistic. More recent research shows that the brain’s control of eating involves more than just the interaction of a pair of ‘stop-eating’ and ‘start-eating’ areas in the brain (Winn, 1995). For example, the paraventricular nucleus in the hypothalamus also plays an important role. As with the ventromedial nucleus, stimulating the paraventricular nucleus results in reduced food intake. Damaging it causes animals to become obese (Leibowitz, 1992). In addition, hunger – and the eating of particular types of food – is related to the effects of various neurotransmitters on certain neurons in the brain. One of these neurotransmitters, called neuropeptide Y, stimulates increased eating of carbohydrates (Kishi & Elmquist, 2005; Kuo et al., 2007). Another one, serotonin, suppresses carbohydrate intake. Galanin motivates the eating of high-fat food (Krykouli et al., 1990), whereas enteristatin reduces it (Lin et al., 1998). Endocannabinoids stimulate eating in general, especially the eating of tasty foods (DiPatrizio et al., 2011). They affect the same hypothalamic receptors as the active ingredient in marijuana, which may account for the ‘munchies’, a sudden hunger that marijuana use often creates (Cota et al., 2003; Di Marzo et al., 2001). Peptide YY3-36 causes a feeling of fullness and reduces food intake (Batterham et al., 2002, 2003). In other words, several brain regions and many chemicals help regulate hunger and food selection. These internal regulatory processes are not set in stone, however. They are themselves shaped, and sometimes overridden, by social, cultural and other factors. One fat mouse Flavour, sociocultural experience and food selection One factor that can override a set point is the flavour of food – the combination of its taste and smell. In one experiment, some animals were offered just a single type of food, whereas others were offered foods of several different flavours. The group getting the varied menu ate nearly four times more than the one-food group. As each new food appeared, the animals began to eat voraciously, regardless of how much they had already eaten (Peck, 1978). Humans behave in similar ways. All things being equal, people eat more food during a multicourse meal than when only one food is served (Remick, Polivy & Pliner, 2009). Apparently, the flavour of any particular food becomes less enjoyable as more of it is eaten (Swithers & Hall, 1994). In one study, for example, people rated how much they liked four kinds of food. Then they ate one of the foods and rated all four again. The food they had just eaten now got a lower rating, whereas liking increased for all the rest (Johnson & Vickers, 1993). 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 487 26/07/17 11:21 AM 488 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Appetite Specific hunger ly Another factor that can override bloodborne signals about satiety is appetite, the motivation to seek food’s pleasures (Zheng et al., 2009). For example, the appearance and aroma of certain foods create conditioned physiological responses – such as secretion of saliva, gastric juices and insulin – in anticipation of eating those foods. (The process is based on the principles of classical conditioning described in Chapter 5, ‘Learning’.) These responses then increase appetite. So merely seeing a pizza on television may prompt you to order one – even if you hadn’t been feeling hungry – and if you see a delicious-looking biscuit, you do not have to be hungry to start eating it. As described in Chapter 1, ‘Introducing psychology’, brain-damaged patients who can’t remember anything for more than a minute will eat a full meal 10–30 minutes after finishing one just like it. They may even start a third meal 10–30 minutes later, simply because the food looks good (Rozin et al., 1998). In other words, people eat not only to satisfy nutritional needs but also to experience enjoyment (Lundy, 2008; Stroebe, Papies & Aarts, 2008). Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Alamy Stock Photo/steven roe Eating can also be influenced by specific hungers, or desires for particular foods at particular times. These hungers appear to reflect the biological need for the nutrients contained in certain foods. In one study, for example, rats were given three bowls of tasty, protein-free food and one bowl of food that tasted bad but was rich in protein. The rats learned to eat enough of the bad-tasting food to get a proper supply of dietary protein (Galef & Wright, 1995). These results are remarkable in part because protein and many other nutrients such as vitamins and minerals have no taste or odour. So how can these nutrients guide food choices? As with appetite, learning is probably involved.The taste and odour of food appears to become associated with the food’s Snapshot nutritional value. Evidence for this kind of learning comes from experiments in which rats received Food infusions of liquid directly into their stomachs. Some of these infusions consisted of plain water; others tourism included nutritious oil or carbohydrate. Each kind of infusion was paired with a different flavour in How has the increase the animals’ normal supply of drinking water. Later, water of both flavours was made available. When in food-based shows like MasterChef and the animals got hungry, they drank more of the water whose flavour had been associated with the television channels nutritious infusions (Yiin, Ackroff & Sclafani, 2004). Related research shows that children come to dedicated to food prefer flavours that have been associated with high-fat ingredients (Johnson, McPhee & Birch, 1991). affected how we think about food? Many people now have a more sophisticated way of talking about and describing food. Food shows even target children, and so we see a greater focus on the kinds of food children are now exposed to. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 488 Learning The role of learning is also seen when we start to eat in response to sights, sounds and places that have been associated with eating in the past (Epstein et al., 2009). If you usually eat when reading or watching television, for example, you may find yourself wanting a snack as soon as you sit down with a book or to watch your favourite show.The same phenomenon has been demonstrated in a laboratory study in which, for several days in a row, hungry rats heard a buzzer just before they were fed. The buzzer eventually became so strongly associated with eating that the rats would start eating when it sounded, even if they had just eaten their fill (Weingarten, 1983). Similarly, even after finishing a big meal, children have been found to resume eating if they enter a room where they have previously had snacks (Birch et al., 1989). Such food-related cues tend to have an especially strong effect on people who are concerned about their weight (Coelho et al., 2009). The food industry has applied research on learning to increase demand for its products (see the Snapshot ‘Food tourism’). For example, the flavourings that fast-food chains routinely add to French fries and hamburger buns have little or no nutritional value, but after becoming associated with those items, these flavourings can trigger strong and distracting cravings for them (Kemps, Tiggemann & Grigg, 2008; Schlosser, 2001). 26/07/17 11:21 AM 489 10.2 Hunger and eating Social and cultural influences Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On The definition of ‘delicacy’ differs from culture to culture. At this elegant restaurant in Cairns, Queensland diners pay to feast on salt-and-pepper prawns and crocodile, grilled kangaroo with quandong chilli glaze, wattleseed pavlova and other dishes that some people from other cultures would not eat even if the restaurant paid them. TRY THIS To appreciate your own food culture, make a list of foods that are traditionally valued by your family or cultural group but that people from other groups do not eat or might even be unwilling to taste. o people tend to D eat less or more depending on how the people around them are eating? Snapshot Ochre Restaurant Bon appétit! APPLYING PSYCHOLOGY ly People also learn social rules and cultural traditions that influence eating. Eating popcorn at the movies and pies at football games are examples from Australian culture (see the snapshot ‘Bon appétit!’) of how certain social situations can stimulate appetite for particular food items. Similarly, how much you eat may depend on what others do. Courtesy or custom may lead you to eat foods you would otherwise avoid. The mere presence of other people, even strangers, tends to increase our food consumption (Redd & de Castro, 1992). Most people consume 60–75 per cent more food when they are with others than when eating alone (Clendenen, Herman & Polivy, 1995); the same effect has been observed in other species, from monkeys to chickens (Galloway et al., 2005; Keeling & Hurink, 1996). Furthermore, if others stop eating, we may do the same even if we are still hungry – especially if we want to impress them with our self-control (Herman, Roth & Polivy, 2003). Eating and food selection are central to the way people function within their cultures. Celebrations, holidays, vacations and even daily family interactions often revolve around food and what has been called a food culture (Rozin, 2007). As any world traveller knows, there are wide cultural variations in foods and food selection. For example, Indian mothers will often feed their small children hot (chilli- and curry-based) foods, whereas this is not as popular in Western cultures. In China, people in urban areas eat a high-cholesterol diet rich in animal meat, whereas those in rural areas eat so little meat as to be cholesterol-deficient (Tian et al., 1995). Insects known as palm weevils are a popular food for people in Papua New Guinea (Paoletti, 1995) but are regarded as disgusting to eat by many Westerners (Springer & Belk, 1994). Meanwhile, the beef that Westerners enjoy is morally repugnant to devout Hindus in India. Even within the same culture, different groups may have sharply contrasting food traditions. Bush tucker (for example, wattle seeds, native berries, emu meat, grubs) might not be found on most dinner tables in Australia, but it was long a staple part of the Australian Aboriginal diet and is still considered a delicacy by some today. This is not the case, however, with the kumara, or sweet potato, which is a traditional Māori food and is also eaten all over New Zealand – and, in fact, the rest of the world. Culture also plays a role in the amount of food we eat. For example, portion sizes in restaurants, fruit and vegetable shops, and even cookbook recipes tend to be smaller in France, Britain and other European countries than in other Western countries (Rozin et al., 2003). Europeans also tend to eat more slowly, which allows satiety signals to reach their brains before they have overindulged. Some of these differences between ‘slow-food’ and ‘fast-food’ cultures might account for why residents of some countries eat less than those in other countries but feel equally satisfied (Geier, Rozin & Doros, 2006; Slow Food Movement, 2001). In summary, eating serves functions that go well beyond nutrition – functions that remind us of who we are and with whom we identify. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 489 26/07/17 11:21 AM 490 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Unhealthy eating Problems in the processes regulating hunger and eating may cause eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, or a level of food intake that leads to obesity. obesity a condition in The World Health Organization defines obesity as a condition in which a person’s body mass index, or BMI, is greater than 30. BMI is determined by taking a person’s weight in kilograms and dividing that number by the square of the person’s height in metres. So someone who is 1.6 metres tall and weighs 85 kilograms would be classified as obese. People whose BMI is between 25 and 29.9 are considered overweight. (Keep in mind, though, that a given volume of muscle weighs more than the same volume of fat, so very muscular individuals may have an elevated BMI without being overweight.) BMI calculators appear on various websites; for example, the Australian Government’s Healthy Weight site (www.healthyactive.gov.au/internet/healthyactive/publishing.nsf/Content/your-bmi). In Australia in 2014, it was reported that, according to the BMI criterion, some 35 per cent of adults were classified as overweight and 28 per cent of adults were classified as obese. In addition, around 25 per cent of Australian children aged 5–18 years were considered to be either overweight or obese. The percentages are even higher for those exposed to greater disadvantage – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are nearly twice as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to suffer from obesity (Australian National Preventive Health Agency Report, 2014). These trends are mirrored in New Zealand (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2015). Obesity has become so common in some parts of the globe that commercial jets now have to burn excess fuel to carry heavier loads, parents of obese young children have trouble finding car safety seats to fit them, and the funeral industry has to offer larger-than-normal coffins and buy wider hearses (Dannenberg, Burton & Jackson, 2004; Saint John, 2003;Trifiletti et al., 2006).The problem is especially severe in much of the Western world. An analysis of data from 106 countries in Asia, Europe, South America and Africa – comprising about 88 per cent of the world’s population – found that 23.2 per cent of adults are overweight and another 10 per cent are obese. Projections based on present trends suggest that by 2030, there will be over one billion obese people living in these countries (Kelly et al., 2008). Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly which a person is severely overweight, as measured by a body mass index greater than 30 Obesity Obesity and health Obesity increases the risk of death (Flegal et al., 2013), with life expectancy reduced by an average of six to seven years (Haslam & James, 2005), in part by creating more risk of Type 2 diabetes, respiratory disorders, high blood pressure, cancer, heart attack and stroke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). In Australia, it’s believed that obesity soon will be responsible for more deaths than smoking. If the current trend continues, it’s predicted that by the age of 20, Australian children will have a shorter life expectancy than previous generations. Especially in adolescence, obesity is associated with the development of anxiety and depression (Anderson et al., 2007; Baumeister & Härter, 2007; BeLue, Francis & Colaco, 2009; Gariepy, Nitka & Schmitz, 2010; Kasen et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2009), although it is not yet clear whether the relationship is causal and, if it is, which condition might be causing which problem (Atlantis & Baker, 2008; Kivimäki et al., 2009; Scott et al., 2008). A recent review of numerous longitudinal studies suggests that the relationship may be bidirectional; that is, obesity can lead to depression, and depression can lead to obesity (Luppino et al., 2010). Possible causes of the obesity epidemic The precise reasons for this obesity epidemic are unknown, but possible causes include big portion sizes at fast-food outlets, greater prevalence of high-fat foods, and less physical activity associated 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 490 26/07/17 11:21 AM 491 10.2 Hunger and eating A radical approach to obesity Snapshot The popularity of bariatric surgery in Australia has been fuelled to a certain extent by the example of celebrities such as Mikel Mason ‘Mikey’ Robins, a media personality, comedian and writer who is best known for his performances on the satirical TV game show Good News Week. Robins underwent the procedure and experienced dramatic weight loss. The surgery is not risk-free, though, and so is recommended mainly for extreme and life-threatening cases of obesity. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly with both work and recreation (for example, Adachi-Mejia et al., 2007; Slentz et al., 2004). These are important factors because the body maintains a given weight through a combination of food intake and energy output (Keesey & Powley, 1986). Obese people get more energy from food than their body metabolises, or ‘burns up’; the excess energy, measured in kilojoules, is stored as fat. Metabolism declines during sleep and rises with physical activity. Because women tend to have a lower metabolic rate than men, even when equally active, they tend to gain weight more easily than men with similar diets (Ferraro et al., 1992). Most obese people have normal resting metabolic rates, but they tend to eat too much high-kilojoule, tasty foods and too little low-kilojoule foods (Kauffman, Herman & Polivy, 1995). Furthermore, some obese people are less active than lean people, a pattern that often begins in childhood (Jago et al., 2005; Marshall et al., 2004; Strauss & Pollack, 2001). Spending long hours watching television or playing video games is a major cause of the inactivity seen in overweight children (for example, Bickham et al., 2013), which may partly explain why children who have a TV in their bedrooms are more likely to be overweight than those who don’t (Gilbert-Diamond et al., 2014). In short, inadequate physical activity combined with overeating – especially of the high-fat foods so prevalent in most Western cultures – has a lot to do with obesity (Arsenault et al., 2010). But not everyone who is inactive and eats a high-fat diet becomes obese, and some obese people are as active as lean people, so other factors must also be involved (Blundell & Cooling, 2000; Parsons, Power & Manor, 2005). Some people probably have a genetic predisposition toward obesity (for example, Frayling et al., 2007; Llewellyn et al., 2014). For example, although most obese people have the genes to make leptin, they may not be sensitive to its weight-suppressing effects, perhaps because of genetic codes in leptin receptors in the hypothalamus. Brain-imaging studies also suggest that obese people’s brains may be slower to ‘read’ satiety signals coming from their blood, thus causing them to continue eating when leaner people would have stopped (Morton et al., 2006; Thorens, 2008). These genetic factors, along with the presence in the body of viruses associated with the common cold and other infectious diseases (Dhurandhar et al., 2000;Vasilakopoulou & LeRoux, 2007), may help explain obese people’s tendency to eat more, to accumulate fat, and to feel more hunger than lean people. For most people, and especially for people who are obese, it is a lot easier to gain weight than to lose it and keep it off. The problem arises partly because our evolutionary ancestors – like nonhuman animals in the wild today – could not always be sure that food would be available. Those who survived lean times were the ones whose genes created tendencies to build and maintain fat reserves (for example, King, 2013; Wells, 2009). These ‘thrifty genes’ are adaptive in famine-plagued environments, but they can be harmful and even deadly in affluent societies in which overeating is unnecessary and in which bakeries and fast-food restaurants are easily accessible (DiLeone, 2009). Furthermore, if people starve themselves to lose weight, their bodies may burn kilojoules more slowly. This drop in metabolism saves energy and fat reserves and slows weight loss (Leibel, Rosenbaum & Hirsch, 1995). As restricted eating enhances activation of the brain’s ‘pleasure centres’, when a hungry person merely looks at energy-rich foods (Siep et al., 2009), restraint becomes even more difficult. That is why health and nutrition experts warn that obese people (and others) should not try to lose a great deal of weight quickly by dramatically cutting food intake (Carels et al., 2008). Given the complexity of factors leading to obesity and the seriousness of its health consequences, it is not surprising that many treatment approaches have been developed. The most radical of these is bariatric surgery (Hamad, 2004), which restructures the stomach and intestines so that less food energy is absorbed and stored (Vetter et al., 2009). Despite its costs and risks – postoperative mortality 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 491 Newspix/Noel Kessel Possible solutions to the obesity epidemic 26/07/17 11:21 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion APPLYING PSYCHOLOGY Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Is changing lifestyle factors such as eating habits and exercise patterns useful in effectively losing weight? rates are between 0.1–2 per cent (Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery Consortium, 2009; Morino et al., 2007) – bariatric surgery is performed on thousands of people a year in Australia, with many who really need assistance unable to afford it (Korda et al., 2012); see the Snapshot ‘A radical approach to obesity’. Millions of other people are taking medications designed either to suppress appetite or to increase the ‘burning’ of fat (Fernstrom & Choi, 2008; Kolonin et al., 2004; Neovius & Narbro, 2008). Though they may seem to offer relatively quick and easy options, neither medication nor surgery alone is likely to solve the problem of obesity. In fact, no single anti-obesity treatment is likely to be a safe, effective solution that works for everyone. To achieve the kind of gradual weight loss that is most likely to last, obese people are advised to make lifestyle changes instead of, or in addition to, seeking medical solutions.The weight-loss programs that are most effective in the long term include components designed to reduce food intake, change eating habits and attitudes towards food, and increase energy expenditure through regular exercise (Bray & Tartaglia, 2000; Dombrowski et al., 2014; Stice & Shaw, 2004; Wadden et al., 2001). These changes can be as simple as limiting the number of available foods, eating from smaller plates, buying lower-fat foods in smaller packages, and fasting one day a week (Levitsky, Iyer & Pacanowski, 2012). ly 492 Prevention of obesity Of course, the ultimate remedy for the obesity epidemic is prevention. To accomplish that goal, parents and other caregivers must begin to promote exercise and healthy eating habits in their children from an early age (Karnik & Kanekar, 2015). The social ecological environment is being targeted in many studies to determine the best time to intervene in the life of children. Some studies are now looking at school curricula as prime areas to target the broad population (Skouteris et al., 2014). We have a long way to go, but Australia and New Zealand can take the lead in this area (Swinburn & Wood, 2013). Changing these habits and preferences will not be easy, but the need to do so is obvious and urgent. anorexia nervosa an eating disorder characterised by self-starvation and dramatic weight loss 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 492 Anorexia nervosa In stark contrast to the problem of obesity is the eating disorder called anorexia nervosa. It is characterised by a combination of self-starvation, self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise and laxative use that results in a body weight that is below 85 per cent of normal (Kaye et al., 2000). According to the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (2004), anorexia affects about 0.5 per cent of young females and 0.1 per cent of young males in Australia and New Zealand, and it is a significant problem in many other industrialised nations as well. About 95 per cent of people with anorexia are young females. These individuals often feel hungry, and many are obsessed with food and its preparation, yet they refuse to eat. Anorexic self-starvation causes serious and often irreversible physical damage, including a reduction in bone density that enhances the risk of fractures (Grinspoon et al., 2000).The health dangers may be especially high in dancers, gymnasts and other female athletes with anorexia because the combination of self-starvation and excessive exercise increases the risk of stress fractures and heart problems (Davis & Kapstein, 2006; Sherman & Thompson, 2004). It has been estimated that 20 per cent of those who suffer severe anorexia eventually die of starvation, biochemical imbalances or suicide. Their death rate is 12 times higher than that of other young women (Suokas et al., 2013). After obesity and asthma, anorexia is the third most common chronic illness for young women, and as many as one in 200 young girls and women will be affected (Garvan Institute, 2012). In New Zealand, approximately 68 000 people, or 1.7 per cent of the population, will suffer in their lifetime from an eating disorder (Oakley-Brown, Wells & Scott, 2006). 26/07/17 11:21 AM 493 10.2 Hunger and eating Possible causes of anorexia In Western cultures today, thinness is a much-sought-after ideal, especially among young women who are dissatisfied with their appearance. That ideal is seen in fashion models and some celebrities, whose BMI has decreased from the ‘normal’ range of 20–25 in the 1920s to an ‘undernourished’ 18.5 more recently (Rubinstein & Caballero, 2000; Voracek & Fisher, 2002). In Australia, nearly 80 per cent of teenage girls diet (Garvan Institute, 2012). Correlational studies suggest that many of these children’s efforts to lose weight may have occurred in response to criticism from family members (Barr Taylor et al., 2006a); for some, the result is anorexia nervosa. To help combat the problem, some fashion shows have now established a minimum BMI for all models. iStock.com/egorr Snapshot Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Thin is in ly Anorexia has been attributed to many factors, including genetic predispositions, hormonal and other biochemical imbalances, social influences (see the Snapshot ‘Thin is in’) and psychological problems (for example, Kaye et al., 2013; Treat & Viken, 2010; Wasylkiw, MacKinnon & MacLellan, 2012). Psychological factors that may contribute to the problem include a self-punishing, perfectionistic personality and a culturally reinforced obsession with thinness and attractiveness (APA Task Force on the Sexualisation of Girls, 2007; Cooley et al., 2008; Dittmar, Halliwell & Ive, 2006; Dohnt & Tiggemann, 2006; Grabe, Ward & Hyde, 2008; Wilksch & Wade, 2010). There is also some research to suggest that genetic factors are shared between anorexia, major depression and suicide attempts (Thornton et al., 2016). Individuals with anorexia appear to develop a fear of being fat, which they take to dangerous extremes; many continue to view themselves as fat or misshapen even as they are wasting away. Treatment of anorexia Drugs, hospitalisation and psychotherapy are all used to treat anorexia. In many cases, treatment brings recovery and maintenance of normal weight (Brewerton & Costin, 2011a, 2011b; Steinglass et al., 2012), but more effective treatment and early intervention methods are still needed. Prevention programs being tested with women at high risk of developing anorexia are showing mixed results (Black Becker et al., 2008; Loucas et al., 2014). Bulimia Like anorexia, bulimia involves an intense fear of being fat, but the person may be thin, normal in weight, or even overweight. Bulimia (also referred to as bulimia nervosa) involves eating huge amounts of food (say, several boxes of biscuits, a litre of ice-cream and burgers) and then getting rid of the food through self-induced vomiting or strong laxatives. These ‘binge-purge’ episodes may occur as often as twice a day (Weltzin et al., 1995). Bulimia shares many features with anorexia (Fairburn et al., 2008). For instance, most people with bulimia are female, and like anorexia, bulimia usually begins with a desire to be slender. However, bulimia and anorexia are quite different disorders (Eddy et al., 2008). For one thing, most people with bulimia see their eating habits as problematic, whereas most individuals with anorexia do not. In addition, bulimia nervosa is usually not life-threatening (Thompson, 1996). There are health consequences, however, including dehydration, nutritional problems and intestinal damage. Many people with bulimia develop dental problems from the acids associated with vomiting. Frequent vomiting and the insertion of objects to trigger it can also cause damage to the throat. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 493 bulimia an eating disorder that involves eating massive amounts of food and then eliminating the food by self-induced vomiting or the use of strong laxatives 26/07/17 11:21 AM 494 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly It has been estimated that 3–5 per cent of the Australian and New Zealand populations are affected by bulimia (Eating Disorders Victoria, 2016), but others have suggested that many cases in the community remain undetected. Furthermore, the incidence of bulimia is actually higher – at one in five – in the general student population (Centre of Excellence in Eating Disorders, 2011). The combinations of factors that contribute to bulimia include perfectionism, low self-esteem, stress, a culturally encouraged preoccupation with being thin, and depression and other emotional problems. Problems in the brain’s satiety mechanisms may also be involved (Crowther et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2007; Stice & Fairburn, 2003; Zalta & Keel, 2006). Treatment for bulimia typically includes individual or group therapy and sometimes antidepressant drugs. These treatments help about 72 per cent of people with bulimia eat more normally; more refined approaches are still needed to help those who do not improve (Herzog et al., 1999; Le Grange et al., 2007; Steinhausen & Weber, 2009). A recent study suggests that we need to regulate information that represents a ‘pro’ eating disorder environment as this may be detrimental to parts of the population (Rodgers et al., 2016). For a summary of the processes involved in hunger and eating, see the section ‘In review: Hunger and eating’. IN REVIEW Hunger and eating STIMULATE EATING INHIBIT EATING Biological factors Glucose and insulin in the blood provide signals that stimulate eating; neurotransmitters affecting neurons in the hypothalamus also stimulate eating and influence hungers for specific kinds of foods. Stomach contractions are associated with subjective feelings of hunger but don’t play a major role in the stimulation of eating. Hormones released into the bloodstream produce signals that inhibit eating; hormones such as leptin, CCK and insulin act as neurotransmitters or neuromodulators and affect neurons in the hypothalamus and inhibit eating. The ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus may be a ‘satiety centre’ that monitors these hormones. Nonbiological factors The sights and smells of particular foods elicit eating because of prior associations; family customs and social occasions include norms for eating in particular ways. Stress also is often associated with eating more. Values in contemporary society encourage thinness and thus can inhibit eating. Check your understanding 1 People may continue eating when they are full, suggesting that eating is not controlled by alone. know that they have a problem; those with an eating disorder 2 People with an eating disorder called tend not to. called as well as improved eating habits. 3 The best strategy for lasting weight loss includes regular 10.3 SEXUAL BEHAVIOUR Unlike food, sex is not necessary for an individual’s survival, but it is obviously vital for improving the chances that an individual’s genes will be represented in the next generation. The various factors shaping sexual motivation and behaviour differ in strength across species, but they often include a combination of the individual’s physiology, learned behaviour, and the physical and social environment. For example, one species of desert bird requires adequate sex hormones, a suitable mate and a particular 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 494 26/07/17 11:21 AM 10.3 Sexual behaviour sexual arousal physiological responses that arise from sexual contact or erotic thoughts Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly environment before it begins sexual behaviour. During the dry season, it shows no interest in sex, but within 10 minutes of the first rain shower, the birds vigorously court and then copulate. Rainfall is obviously much less influential as a sexual trigger for humans. People show an amazing diversity of sexual scripts, or patterns of behaviour that lead to sex. Surveys of university-age men and women identified 122 specific acts and 34 different tactics used for promoting sexual encounters (Greer & Buss, 1994; Meston & Buss, 2007).What actually happens during sex? The matter is difficult to address scientifically because most people are reluctant to respond to specific questions about their sexual practices, let alone to allow researchers to observe their sexual behaviour. Yet having valid information about the nature of human sexual behaviour is a vital first step for psychologists and other scientists who study such topics as individual differences in sexuality, gender differences in sexual motivation and behaviour, sources of sexual orientation, types of sexual dysfunctions, and the pathways through which HIV and other sexually transmitted infections reach new victims. This information can also help people to think about their own sexual behaviour in relation to trends in the general population. 495 FOCUS ON RESEARCH METHODS A survey of human sexual behaviour The first extensive studies of sexual behaviour in the United States were done by Alfred Kinsey during the late 1940s and early 1950s (Kinsey, Pomeroy & Martin, 1948; Kinsey et al., 1953). These were followed in the 1960s by the work of William Masters and Virginia Johnson (1966). Kinsey conducted surveys of people’s sex lives; Masters and Johnson actually recorded volunteers’ sexual arousal, their physiological responses to erotic stimuli that arose during natural or artificial stimulation in a laboratory. Together, these studies broke new ground in the exploration of human sexuality, but the people who volunteered for them were probably not a representative sample of the adult population. Accordingly, the results – and any conclusions drawn from them – may not apply to people in general. Furthermore, the data are now so old that they may not reflect sexual practices today. Unfortunately, the results of more recent surveys, such as reader polls in Cosmopolitan and other magazines, are also flawed by the use of unrepresentative samples (for example, Davis & Smith, 1990). What was the researchers’ question? Is it possible to gather data on sexual behaviour that are more representative and therefore more revealing about people in general? Researchers at the University of Chicago believe it is, so they undertook the National Health and Social Life Survey, the first extensive survey of sexual 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 495 behaviour in the United States since the Kinsey studies (Laumann et al., 1994). How did the researchers answer the question? This survey included important design features that had been neglected in most other surveys of sexual behaviour. First, the study did not depend on self-selected volunteers. The researchers sought out a carefully constructed sample of 3432 people, ranging in age from 18 to 59. Second, the sample reflected the sociocultural diversity of the US population in terms of gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographical location and the like. Third, unlike previous mail-in surveys, the Chicago study was based on face-to-face interviews. This approach made it easier to ensure that the participants understood each question and had the opportunity to explain their responses. To encourage honesty, the researchers allowed participants to answer some questions anonymously by placing written responses in a sealed envelope. What did the researchers find? The researchers found that people in the United States have sex less often and with fewer people than had been assumed. For most, sex occurs about once a week and only between partners in a stable relationship. About a third of the participants reported having sex only a few times, or not at all, in the past year. In contrast 26/07/17 11:21 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion to certain celebrities’ splashy tales of dozens or even hundreds of sexual partners per year, the average male survey participant had only six sexual partners in his entire life. The average female respondent reported a lifetime total of two. Furthermore, the survey data suggested that people in committed, one-partner relationships had the most frequent and the most satisfying sex. Although a wide variety of specific sexual practices were reported, the overwhelming majority of heterosexual couples said they tend to engage mainly in penis–vagina intercourse. Many of these findings are consistent with the results of more recent surveys conducted by other researchers (for example, National Center for Health Statistics, 2007). Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On What do the results mean? around the world (Youm & Laumann, 2002). They have found, for example, that nearly one-quarter of US women prefer to achieve sexual satisfaction without partners of either sex. And although people in the United States tend to engage in a wider variety of sexual behaviours than those in Britain, there is less tolerance in the United States of disapproved sexual practices (Laumann & Michael, 2000; Michael et al., 1998). They have found, too, that although sexual activity declines with advancing age, it by no means disappears. About 26 per cent of people in the 75–85 age group – especially men – reported that they were still sexually active (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010; Lindau et al., 2007). Other researchers have found a number of consistent gender differences in sexuality (Basson, 2001; Schmitt & Kistemaker, 2015). For example, men are more likely than women to mistake another person’s friendliness for sexual interest (Perilloux, Easton & Buss, 2012). This may be because men tend to have a stronger interest in and desire for sex than women, whereas women are more likely than men to associate sexual activity with love and to be affected by cultural and situational influences on sexual attitudes and behaviour (for example, Diamond, 2008; Petersen & Hyde, 2010). Many such differences are actually quite small, and, according to some studies, not necessarily significant (Conley et al., 2011). The results of even the best survey methods – like the results of all research methods – usually raise as many questions as they answer. When do people become interested in sex, and why? How do they choose to express these desires, and why? What determines their sexual likes and dislikes? How do learning and sociocultural factors modify the biological forces that seem to provide the raw material of human sexual motivation? These are some of the questions about human sexual behaviour that a survey cannot easily or accurately explore (Benson, 2003). ly 496 The Chicago survey challenges some of the cultural and media images of sexuality in the United States. In particular, it suggests that people in the United States may be more sexually conservative than one might think on the basis of magazine reader polls and discussions on daytime talk shows. What do we still need to know? Many questions remain. The Chicago survey did not ask about some of the more controversial aspects of human sexuality, such as the effects of pornography, the prevalence of paedophilia (sexual attraction to children), and the role in sexual activity of sexual fetishes such as shoes or other clothing. Had the researchers asked about such topics, their results might have painted a less conservative picture. Furthermore, because the original Chicago survey focused on people in the United States, it told us little or nothing about the sexual practices, traditions and values of people in the rest of the world. The Chicago team has continued to conduct interviews, and the results are beginning to fill in the picture of sexual behaviour in the United States and sexual response cycle the pattern of physiological arousal during and after sexual activity 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 496 The biology of sex Observations in Masters and Johnson’s laboratory led to important findings about the sexual response cycle, the pattern of physiological arousal during and after sexual activity (see Figure 10.4). People’s motivation to engage in sexual activity has biological roots in sex hormones.The female sex hormones include oestrogens and progestational hormones (also called progestins; the main ones are oestradiol and progesterone). The male hormones are androgens; the main one is testosterone. 26/07/17 11:21 AM 497 10.3 Sexual behaviour FIGURE 10.4 The sexual response cycle As shown in the left-hand graph, Masters and Johnson (1966) found that men display one main pattern of sexual response. Women display at least three different patterns from time to time; these are labelled A, B and C in the right-hand graph. For both men and women, the excitement phase begins with sexual stimulation from the environment or one’s own thoughts. Continued stimulation leads to intensified excitement in the plateau phase, and if stimulation continues, to the intensely pleasurable release of tension in the orgasmic stage. During the resolution phase, both men and women experience a state of relaxation. Following resolution, men enter a refractory phase, during which they are unresponsive to sexual stimulation. Women are capable of immediately repeating the cycle. Orgasm Plateau Excitement Excitement B Resolution Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Plateau A C ly Orgasm Refractory period Resolution Cycle in men Resolution Resolution Resolution Cycle in women Adapted from Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1996). Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. Each sex hormone flows in the blood of both sexes, but the average man has more male than female hormones, and the average woman has more female than male hormones. Sex hormones have both organisational and activational effects on the brain: The organisational effects are permanent changes that alter the brain’s response to hormones. The activational effects are temporary behavioural changes that last only as long as a hormone level remains elevated, such as during puberty or in the ovulation phase of the monthly menstrual cycle. In mammals, including humans, the organisational effects of hormones occur around the time of birth, when certain brain areas are sculpted into a ‘malelike’ or ‘femalelike’ pattern. These areas are described as sexually dimorphic. In rodents, for example, a sexually dimorphic area of the hypothalamus appears to underlie specific sexual behaviours. When these areas are destroyed in male gerbils, the animals can no longer copulate; yet damage to other nearby brain regions does not affect sexual behaviour (Yahr & Jacobsen, 1994). Sexually dimorphic areas also exist in the human hypothalamus and elsewhere in the brain (Breedlove, 1994; Kimura, 1999). For example, an area of the hypothalamus called the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BnST) is generally smaller in women than in men. Its possible role in some aspects of human sexuality was suggested by a study of transsexual men – genetic males who feel like women and who may request surgery and hormone treatments in order to appear more female. The BnST in these men was smaller than in other men; in fact, it was about the size usually seen in women (Zhou et al., 1995). Rising levels of sex hormones during puberty have activational effects, resulting in increased sexual desire and interest in sexual behaviour. Generally, oestrogens and androgens stimulate females’ sexual interest (Burleson, Gregory & Trevarthen, 1995; Sherwin & Gelfand, 1987). Androgens raise males’ sexual interest (Davidson, Camargo & Smith, 1979). The activational effects of hormones are also seen in reduced sexual motivation and behaviour among people whose hormone-secreting ovaries or testes have been removed for medical reasons. Injections of hormones help restore these people’s sexual interest and activity. ●● ●● 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 497 sex hormones chemicals in the blood of males and females that have both organisational and activational effects on sexual behaviour oestrogens sex hormones that circulate in the bloodstream of both men and women; more oestrogens circulate in women than in men progestational hormones sex hormones that circulate in the bloodstream of both men and women, also known as progestins; more progestins circulate in women than in men androgens sex hormones that circulate in the bloodstream of both sexes; more androgens circulate in men than in women 26/07/17 11:21 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Snapshot Social influences on sexual behaviour In humans, sexuality is shaped by a lifetime of learning and thinking that modifies the biological ‘raw materials’ provided by hormones. For example, children learn some of their sexual attitudes and behaviours as part of the development of gender roles, which we discuss in Chapter 11, ‘Human development’. The specific attitudes and behaviours learned depend partly on the nature of those gender roles in a particular culture (Baumeister, 2000; Hyde & Durik, 2000; Peplau, 2003; Petersen & Hyde, 2010). Over 19 000 Australians were surveyed about their sexual experiences by La Trobe University (Smith et al., 2002) in one of the largest surveys conducted in the country. The results indicated that there had been a change in behaviour and experiences since the 1950s. For example, the age of first intercourse declined from 19 to 16 years, while the use of contraception at first intercourse increased from less than 30 per cent of men and women to over 90 per cent. Gender and culture There are gender differences, too, in what people find sexually appealing. For example, in many cultures, men are far more interested in and responsive to pornographic films and other erotic stimuli than women are (Herz & Cahill, 1997; Petersen & Hyde, 2010; Symons, 1979). The difference in responsiveness was demonstrated in an MRI study that scanned the brain activity of males and females while they looked at erotic photographs (Hamann et al., 2004). As expected, the males showed greater activity in the amygdala and hypothalamus than the females. But even though there were gender differences in brain activity, the male and female participants rated the photos as equally appealing and arousing. In another study, when men reported sexual arousal in response to erotic films, they also showed signs of physiological arousal. For women, self-reports of arousal were not strongly correlated with signs of physiological arousal (Chivers et al., 2004). Furthermore, though men and women both show more sexual arousal to more intensely erotic films, the level of women’s arousal may not depend as much as men’s does on whether the actors are males or females (Chivers, Seto & Blanchard, 2007). A third study found that women were aroused by a wider range of sexual stories than men were (Suschinsky & Lalumière, 2011). These are just a few examples of the fact that sexuality is a product of a complex mixture of factors (see the Snapshot ‘Social influences on sexual behaviour’). Each person’s learning history, cultural background and perceptions of the world interact so deeply with such a wide range of physiological processes that – as in many other aspects of human behaviour and mental processes – it is impossible to separate their influence on sexuality. Nowhere is this point clearer than in the case of sexual orientation. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Newspix/Ross Swanborough Sexual behaviour is shaped by many sociocultural forces. For example, concern over teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS, has prompted schoolbased educational programs to encourage premarital sexual abstinence or ‘safe sex’ using condoms. These efforts have helped change young people’s sexual attitudes and practices (for example, Jemmott, Jemmott & Fong, 2010). Social and cultural factors in sexuality ly 498 sexual orientation the nature of a person’s enduring emotional, romantic or sexual attraction to others heterosexuality sexual motivation that is focused on members of the other sex homosexuality sexual motivation that is focused on members of one’s own sex bisexuality sexual motivation that is focused on members of both sexes 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 498 Sexual orientation Sexual orientation refers to the nature of a person’s enduring emotional, romantic or sexual attraction to others (American Psychological Association, 2002; Ellis & Mitchell, 2000).The most common sexual orientation is heterosexuality, in which the attraction is to members of the other sex.When attraction focuses on members of one’s own sex, the orientation is called homosexuality; male homosexuals are referred to as gay men and female homosexuals as lesbians. Bisexuality refers to people who are attracted to members of both sexes. Sexual orientation involves feelings that may or may not be translated into corresponding patterns of sexual behaviour (Diamond, 2008; Pathela et al., 2006). For example, some people whose orientation is gay, lesbian or bisexual may have sex only with opposite-sex partners. Similarly, people whose orientation is heterosexual may have had one or more same-sex encounters. In many cultures, heterosexuality has long been regarded as a moral norm, and homosexuality has been cast as a disease, a mental disorder, or even a crime (Hooker, 1993). Yet attempts to alter 26/07/17 11:21 AM 499 10.3 Sexual behaviour Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly the sexual orientation of gay men and lesbians – using psychotherapy, brain surgery or electric shock – have usually been ineffective (American Psychiatric Association, 1999; Smith, Bartlett & King, 2004). In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association dropped homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, thus ending its official status as a form of psychopathology. The same change was made by the World Health Organization in its International Classification of Diseases in 1993, by Japan’s psychiatric organisation in 1995, and by the Chinese Psychiatric Association in 2001. Nevertheless, some people still disapprove of homosexuality. Many gays, lesbians and bisexuals are often the victims of discrimination and even hate crimes, and are reluctant to let their sexual orientation be known (Bernat et al., 2001; Meyer, 2003). It is difficult, therefore, to paint an accurate picture of the mix of heterosexual, homosexual and bisexual orientations in a population. In the Chicago sex survey mentioned earlier, 1.4 per cent of women and 2.8 per cent of men identified themselves as exclusively homosexual (Laumann et al., 1994), figures much lower than the 10 per cent found in Kinsey’s studies. However, the Chicago survey’s face-to-face interviews did not allow respondents to give anonymous answers to questions about sexual orientation. Some researchers suggest that if anonymous responses to those questions had been permitted, the prevalence figures for gay, lesbian and bisexual orientations would have been higher (Bullough, 1995). In fact, studies that have allowed anonymous responding estimate that gay, lesbian and bisexual people may make up to 21 per cent of the populations in Australia, the United States, Canada and Western Europe (Aaron et al., 2003; Hayes et al., 2012; Savin-Williams, 2006). THINKING CRITICALLY What shapes sexual orientation? The question of where sexual orientation comes from is a topic of intense debate in scientific circles, on talk shows, on the Internet, and in everyday conversations. What am I being asked to believe or accept? Some people believe that genes exert a major influence on our sexual orientation. According to this view, we do not learn a sexual orientation but rather are born with a strong predisposition to develop a particular orientation. What evidence is available to support the assertion? In 1995, a report by a respected research group suggested that one kind of sexual orientation – namely, that of gay men – is associated with a particular gene on the X chromosome (Hu et al., 1995). This finding was not supported by later studies (Rice et al., 1999), but a growing body of evidence from research in behavioural genetics suggests that genes may indeed influence sexual orientation (Kendler et al., 2000; Pillard & Bailey, 1998). One study examined pairs of monozygotic male twins (whose genes 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 499 are identical), non-identical twin pairs (whose genes are no more alike than those of any brothers) and pairs of adopted brothers (who are genetically unrelated). To participate in this study, at least one brother in each pair had to be gay. As it turned out, the other brother was also gay or bisexual in 52 per cent of the identical-twin pairs. This was the case in only 22 per cent of the non-identical twin pairs and in just 11 per cent of the pairs of adopted brothers (Bailey & Pillard, 1991). Similar findings have been reported for male identical twins raised apart, whose shared sexual orientation cannot be attributed to the effects of a shared environment (Whitam, Diamond & Martin, 1993). The few available studies of female sexual orientation have yielded similar results (Bailey & Benishay, 1993; Bailey, Dunne & Martin, 2000). Other evidence for the role of biological factors in sexual orientation comes from research on the impact of sex hormones. In adults, differences in the levels of these hormones are not generally associated with differences in sexual orientation. However, hormonal differences during prenatal development may be involved in the shaping of 26/07/17 11:21 AM 500 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Snapshot A committed relationship, with children ly 2007). We don’t yet know exactly how prenatal hormonal influences might operate to affect sexual orientation, but studies of non-human animals have found that such influences alter the structure of the hypothalamus, a brain region known to underlie some aspects of sexual functioning (Swaab & Hofman, 1995). Finally, a biological basis for sexual orientation is suggested by the fact that sexual orientation is not predicted by environmental factors. Several studies have shown, for example, that the sexual orientation of children’s caregivers has little or no effect on those children’s own sexual orientation (see the Snapshot ‘A committed relationship, with children’). Several studies have shown that children adopted by gay or lesbian parents are no more or less likely to have a homosexual orientation than children raised by heterosexual parents (Anderssen, Amlie & Ytteroy, 2002; Bailey et al., 1995; Stacey & Biblarz, 2001; Tasker & Golombok, 1995). Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On sexual orientation (Lalumière, Blanchard & Zucker, 2000; Lippa, 2003; Williams et al., 2000), and the influences may differ for men and women (Mustanski, Chivers & Bailey, 2002). For example, one study found that women – but not men – who had been exposed to high levels of androgens during their foetal development were much more likely to report bisexual or homosexual behaviours or fantasies than relatives of the same sex who had not been exposed (Hines, Brook & Conway, 2004; Meyer-Bahlburg et al., 2008). Another line of research focuses on the possibility that previous pregnancies may permanently affect a woman’s hormones in ways that influence the sexual orientation of her next child (Blanchard, 2001). Some evidence for this hypothesis comes from a study showing that the more older biological brothers a man has, the higher the probability that he will have a homosexual orientation (Blanchard & Lippa, 2007; Bogaert, Blanchard & Crosthwait, 2007). These results appear to reflect mainly hormonal rather than mainly environmental influences because the number of non-biological (adopted) brothers that the men had was not predictive of their sexual orientation. Furthermore, because sexual orientation in women was not predicted by the number and gender of their older biological siblings, it was thought that the hormonal consequences of carrying male foetuses might influence only males’ sexual orientation. The picture is not that simple. Other researchers have found that women’s sexual orientation, too, is related to the number of older biological brothers they have (McConaghy et al., 2006), and still others have reported a relationship between men’s sexual orientation and the number of older biological sisters they have (Francis, 2008; Vasey & VanderLaan, ONOKY – Fabrice LEROUGE/Brand X Pictures/Getty Images Like heterosexual relationships, gay and lesbian relationships can be brief and stormy or stable and permanent (Kurdek, 2005). These gay men are committed to each other for the long haul, as can be seen in their decision to adopt two children together. The strong role of biological factors in sexual orientation is supported by research showing that their children’s orientation will not be influenced much, if at all, by that of their adoptive parents (for example, Anderssen, Amlie & Ytteroy, 2002; Patterson, 2004; Stacey & Biblarz, 2001). 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 500 Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence? Like all correlational data, correlations between genetics and sexual orientation are open to alternative interpretations. As discussed in Chapter 2, ‘Research in psychology’, a correlation describes the strength and direction of a relationship between variables, but it does not guarantee that one variable is actually influencing the other. Consider again the data showing that brothers who shared the most genes (identical twins) were also most likely to share a gay sexual orientation. It is possible that what the brothers shared was not a ‘gay gene’ but rather a set of genes that influenced the boys’ activity levels, emotionality, aggressiveness and the like. One example is 26/07/17 11:21 AM 501 10.3 Sexual behaviour ly various sexual orientations. In studying these topics, researchers will want to know more not only about the genetic characteristics of people with different sexual orientations, but also about their mental and behavioural styles. Are there personality characteristics associated with different sexual orientations? If so, do those characteristics have a strong genetic component? To what extent are gay men, lesbians, bisexuals and heterosexuals similar – and different – in terms of cognitive styles, biases, coping skills, developmental histories and the like? Are there any differences in how sexual orientation is shaped in males versus females (Bailey, Dunn & Martin, 2000)? The more we learn about sexual orientation in general, the easier it will be to interpret data relating to its origins. But even defining sexual orientation is not simple because people do not always fall into discrete categories (American Psychological Association, 2002; Diamond, 2008; Savin-Williams, 2006; Thompson & Morgan, 2008; Worthington et al., 2008). Should a man who identifies himself as gay be considered bisexual because he occasionally has heterosexual daydreams? What sexual orientation label would be appropriate for a 40-year-old woman who experienced a few lesbian encounters in her teens but has engaged in exclusively heterosexual sex since then? Progress in understanding the origins of sexual orientation would be enhanced by a generally accepted system for describing and defining exactly what is meant by the term sexual orientation. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On gender conformity or non-conformity in childhood – the tendency for children to either conform or not conform to the behaviours, interests and appearance that are typical for their gender in their culture (Bailey, Dunn & Martin, 2000; Knafo, Iervolino & Plomin, 2005). These general aspects of their temperaments or personalities in childhood – and other people’s reactions to them – could influence the likelihood of a particular sexual orientation (Bem, 2000). In other words, sexual orientation could arise as a reaction to the way people respond to a genetically determined but non-sexual aspect of personality. Prenatal hormone levels, too, could influence sexual orientation by shaping aggressiveness or other nonsexual aspects of behaviour. It is also important to look at behavioural genetics evidence for what it can tell us about the role of environmental factors in sexual orientation. When we read that both members of identical twin pairs have a gay sexual orientation 52 per cent of the time, it is easy to ignore the fact that the orientation of the twin-pair members was different in 48 per cent of the cases. Viewed in this way, the results suggest that genes do not tell the entire story of sexual orientation. Indeed, evidence that sexual orientation has its roots in biology does not mean that it is determined by unlearned genetic forces alone. As described in Chapter 3, ‘Biological aspects of psychology’, the brains and bodies we inherit are quite responsive to environmental influences. The behaviours we engage in and the environmental experiences we have often result in physical changes in the brain and elsewhere (Wang et al., 1995). Every time we form a new memory, for example, changes occur in the brain’s synapses. So differences in the brains of people with differing sexual orientations could be the effect, not the cause, of their behaviour or experiences. What additional evidence would help evaluate the alternatives? Much more evidence is needed about the role of genes in shaping sexual orientation. We also have much to learn about the extent to which genes and hormones shape physical and psychological characteristics that lead to 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 501 What conclusions are most reasonable? The evidence available so far suggests that genetic factors, probably operating through prenatal hormones, create differences in the brains of people with different sexual orientations. However, the manner in which a person expresses a genetically influenced sexual orientation will be profoundly shaped by what that person learns through social and cultural experiences (Bancroft, 1994). In short, as is true of so many other psychological phenomena, sexual orientation most likely results from the complex interplay of both genetic and non-genetic mechanisms – both nature and nurture. 26/07/17 11:21 AM 502 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion IN REVIEW Sexual behaviour ASPECTS DESCRIPTION Sex is not necessary for an individual’s survival, but it is vital for improving the chances that an individual’s genes will be represented in the next generation. Sexual scripts Sexual scripts are patterns of behaviour that lead to sex. Social and cultural factors in sexuality Sexual attitudes and behaviours are part of the development of gender roles. There are gender differences in what people find sexually appealing. Biology of sex Sex hormones are chemicals in the blood of males and females: Oestrogens – sex hormones that circulate in the bloodstream of both men and women; more oestrogens circulate in women than in men Progestational hormones – sex hormones that circulate in the bloodstream of both men and women, also known as progestins; more progestins circulate in women than in men Androgens – sex hormones that circulate in the bloodstream in both sexes; more androgens circulate in men than in women. Testosterone is the main one. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Role of sex The nature of a person’s enduring emotional, romantic or sexual attraction to others: Heterosexuality – sexual motivation that is focused on members of the other sex. Homosexuality – sexual motivation that is focused on members of one’s own sex. Bisexuality – sexual motivation that is focused on members of both sexes. Sexual orientation Check your understanding 1 Each person’s learning history, cultural background and perceptions of the world interact to influence and effects on the brain. 2 Sex hormones have 3 Some studies indicate that estimates of gay, lesbian and bisexual people in some populations are at . per cent. 10.4 ACHIEVEMENT MOTIVATION This sentence was written at 6 a.m. on a beautiful Sunday morning. Why would someone get up that early to work on a weekend? Why do people take their work seriously and try to do the best that they can? People work hard partly due to extrinsic motivation, a desire for external rewards such as money.Work and other human behaviours also reflect intrinsic motivation, a desire to attain internal satisfaction (Deci, Koestner & Ryan, 2001), including the kind that has been described by some psychologists as flow (Hektner, Schmidt & Csikszentmihalyi, 2007). If you have ever lost track of time while utterly absorbed in some intensely engaging work or recreation or athletics or creative activity, you have experienced flow, or what some people call being ‘in the zone’. The next time you visit someone’s home or office, look at the mementos displayed there. You may see framed degrees and awards, trophies and ribbons, and photos of children and grandchildren. These badges of achievement affirm that a person has accomplished tasks that merit approval or establish worth. Much of our behaviour is motivated by a desire for approval, admiration and achievement – in short, for esteem – from others and from ourselves. In this section, we examine two of the most common avenues to esteem: achievement in general and a job in particular. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 502 26/07/17 11:21 AM 503 10.4 Achievement motivation Need for achievement Many athletes who already hold world records still train intensely; many people who built multimillion-dollar businesses still work 14-hour days. What motivates these people? Some psychologists suggest that the answer is a desire for mastery or effectance (Kusyszyn, 1990; Surtees et al., 2006; White, 1959), the motivation to behave competently. These terms are similar to an earlier concept described by Henry Murray (1938) as need achievement. People with a high achievement motivation seek to master tasks – be they sports, business ventures, intellectual puzzles or artistic creations – and obtain intense satisfaction from doing so. They strive for excellence, enjoy themselves in the process, and take great pride in achieving at a high level. Individual differences which a person establishes specific goals, cares about meeting those goals, and experiences feelings of satisfaction by doing so Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly How do people with strong achievement motivation differ from others? To find out, researchers gave children a test to measure their need for achievement and then asked them to play a ring-toss game. Children scoring low on the need achievement test usually stood either so close to the ring-toss target that they couldn’t fail or so far away that they couldn’t succeed. In contrast, children scoring high on the need achievement test stood at a moderate distance from the target, making the game challenging but not impossible (McClelland, 1958). These and other experiments suggest that people with high achievement motivation tend to set challenging but realistic goals for themselves. They are interested in their work, actively seek success, take risks when necessary, and are intensely satisfied when they succeed (Eisenberger et al., 2005). If they feel they have tried their best, people with high achievement motivation are not too upset by failure. Those with low achievement motivation also like to succeed, but instead of joy, success tends to bring them relief at having avoided failure (Winter, 1996).There is some evidence that the differing emotions – such as anticipation versus worry – that accompany the efforts of people with high and low achievement motivation can affect how successful those efforts will be (Pekrun, Elliot & Maier, 2009). achievement motivation the degree to Learning goals Differences in achievement motivation also appear in the kinds of goals people seek in achievementrelated situations (Corker & Donnellan, 2012). Some people tend to adopt learning goals. When they play golf, take piano lessons, work at puzzles and problems, go to school and get involved in other achievement-oriented activities, they do so mainly to get better at those activities. Realising that they may not yet have the skills necessary to achieve at a high level, they tend to learn by watching others and to struggle with problems on their own rather than asking for help (Mayer & Sutton, 1996).When they do seek help, people with learning goals are likely to ask for explanations, hints and other forms of task-related information, not for quick, easy answers that remove the challenge from the situation. Performance goals In contrast, people who adopt performance goals are usually more concerned with demonstrating the skill they believe they already possess. They tend to seek information about how well they have performed compared with others rather than about how to improve their performance (Butler, 1998). When they seek help, it is usually to ask for the right answer rather than for tips on how to find that answer themselves. As their primary goal is to demonstrate their competence, people with performance goals tend to avoid new challenges if they are not confident that they will be successful, and they tend to quit in response to failure (Grant & Dweck, 2003). Those with learning goals tend to be more persistent and less upset when they don’t immediately perform well (Niiya, Crocker & 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 503 26/07/17 11:21 AM 504 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Bartmess, 2004); having learning goals also predicts better adjustment among students who are going to school in an unfamiliar culture (Gong & Fan, 2006). Development of achievement motivation Achievement motivation develops in early childhood, under the influence of both genetic and environmental forces. Parental influence Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Is it possible to enhance people’s achievement motivation through childhood training and even later in life? ly APPLYING PSYCHOLOGY As described in Chapter 13, ‘Personality’, children inherit general behavioural tendencies, such as impulsiveness and emotionality, and these tendencies may support or undermine the development of achievement motivation. The motivation to achieve is also shaped by what children learn from watching and listening to others, especially their parents. Evidence for the influence of parental teachings about achievement comes from a study in which young boys were given a difficult task at which they were sure to fail. Fathers whose sons scored low on achievement motivation tests often became annoyed as they watched their boys struggle.They discouraged them from continuing, interfered or even completed the task themselves (Rosen & D’Andrade, 1959). A different pattern of behaviour appeared among parents of children who scored high on tests of achievement motivation. Those parents tended to encourage the child to try difficult tasks, especially new ones; give praise and other rewards for success; encourage the child to find ways to succeed rather than merely complaining about failure; and prompt the child to go on to the next, more difficult challenge (McClelland, 1985). Research with adults shows that even the slightest cues that bring a parent to mind can boost people’s efforts to achieve a goal (Shah, 2003), and that university students – especially those who have learning goals – feel closer to their parents while taking exams (Moller, Elliot & Friedman, 2008). Cultural influences More general cultural influences also affect the development of achievement motivation. For example, subtle messages about a culture’s view of how achievement occurs often appear in the books children read and the stories they hear. Does the story’s main character work hard and overcome obstacles, thus creating expectations of a pay-off for persistence? Or does a lazy main character drift aimlessly and then win the lottery, suggesting that rewards come randomly, regardless of effort? If the main character succeeds, is it the result of personal initiative, as is typical of stories in individualist cultures? Or is success based on ties to a cooperative and supportive group, as is typical of stories in collectivist cultures? Is the role of parents important to the academic achievement of Indigenous Australians? These themes appear to act as blueprints for reaching culturally approved goals. It should not be surprising, then, that ideas about how people achieve differ from culture to culture. In a study by Boon (2008), the role of parenting variables was significant for protecting against future problem behaviours and achieving academically in Indigenous adolescents. Achievement motivation is also influenced by how much a particular culture values and rewards achievement. For example, the motivation to excel is likely to be especially strong in cultures in which demanding standards lead students to fear rejection if they fail to attain high grades (Eaton & Dembo, 1997). In short, achievement motivation is strongly influenced by social and cultural learning experiences, as well as by the beliefs about oneself that these experiences help create (see the Snapshot ‘Helping them do their best’). People who come to believe in their ability to achieve are more likely to do so than those who expect to fail (Dweck, 1998; Greven et al., 2009; Tuckman, 2003; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 504 26/07/17 11:21 AM 505 10.4 Achievement motivation Snapshot Helping them do their best Newspix/Bryan Lynch Learning-oriented goals are especially appropriate in classrooms, where students typically have little knowledge of the subject matter. This is why most teachers tolerate errors and reward gradual improvement. They do not usually encourage performance goals, which emphasise doing better than others and demonstrating immediate competence (Reeve, 1996). Still, to help students do their best in the long run, teachers sometimes promote performance goals too. The proper combination of both kinds of goals may be more motivating than either kind alone (Barron & Harackiewicz, 2001). ly Goal setting and achievement motivation Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Why are you reading this chapter instead of watching television or hanging out with your friends? Your motivation to study is probably based on your goal of doing well in a psychology course, which relates to broader goals, such as earning a degree, having a career and the like. Psychologists have found that we set goals when we recognise a discrepancy between our current situation and how we want that situation to be (Oettingen, Pak & Schnetter, 2001). Establishing a goal motivates us to engage in behaviours designed to reduce the discrepancy we have identified. The kinds of goals we set can influence the amount of effort, persistence, attention and planning we devote to a task (Morisano et al., 2010). In general, the more difficult the goal, the harder people will try to reach it (see the Snapshot ‘“Maybe they didn’t try hard enough”’). This rule assumes, of course, that the goal is seen as realistic. Goals that are impossibly difficult may not motivate us to exert maximum effort.The rule also assumes that we value the goal. If a difficult goal is set by someone else – as when a parent assigns a teenager to keep a large lawn and garden trimmed and weeded – people may not accept it as their own and may not work very hard to attain it. Setting goals that are clear and specific tends to increase people’s motivation to persist at a task (Locke & Latham, 2002). For example, you are more likely to keep reading this chapter if your goal is to ‘read the motivation section of the motivation and emotion chapter today’ than if it is to ‘do some studying’. Clarifying your goal makes it easier to know when you have reached it and when it is time to stop. Without clear goals, a person can be more easily distracted by fatigue, boredom or frustration, and more likely to give up before completing a task. Clear goals also tend to focus people’s attention on creating plans for pursuing them, on the activities they believe will lead to goal attainment, and on evaluating their progress. In short, the process of goal setting is more than just wishful thinking. It is an important first step in motivating all kinds of behaviour. Snapshot ‘Maybe they didn’t try hard enough’ Al Ross/The New Yorker Collection/ www.cartoonbank.com Children raised in environments that support the development of strong achievement motivation tend not to give up on difficult tasks – even if all the king’s horses and all the king’s men do! 'Maybe they didn't try hard enough.' 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 505 26/07/17 11:22 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Success in the workplace Snapshot In the workplace, there is usually less concern with employees’ general level of achievement motivation than with their motivation to work hard during business hours. In fact, employers tend to set up jobs in accordance with their ideas about how intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation combine to shape their employees’ performance (Riggio, 1989). Employers who see workers as lazy, dishonest and lacking in ambition tend to offer highly structured, heavily supervised jobs that give employees little say in deciding what to do or how to do it. These employers assume that workers are motivated mainly by extrinsic rewards – money in particular. So they tend to be surprised when, despite good wages, employees sometimes express dissatisfaction with their jobs and show little motivation to work hard (Diener & Seligman, 2004; Igalens & Roussel, 1999). Influences on job satisfaction If good pay alone doesn’t bring job satisfaction and the desire to excel on the job, what does? In Western cultures, low worker motivation comes largely from the feeling of having little or no control over the work environment (Rosen, 1991). Compared with those in rigidly structured jobs, workers tend to be more satisfied and productive if they are encouraged to participate in decisions about how work should be done; given problems to solve, without being told how to solve them; taught more than one skill; given individual responsibility; and given public recognition, not just money, for good performance (Fisher, 2000). Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On iStock.com/Drazen Lovric Some Australian companies recognise individual contributions to the success of the company. The goal is to increase productivity and job satisfaction by rewarding employees who solve problems and make decisions about how best to do their jobs. Individuals are publicly recognised for outstanding work and often their picture is placed in a public domain. Achievement and success in the workplace ly 506 Goal setting Allowing people to set and achieve clear goals is one way of increasing both job performance and job satisfaction (Maynard, Joseph & Maynard, 2006). As suggested by our earlier discussion, some goals are especially effective at maintaining work motivation (Katzell & Thompson, 1990). First, effective goals are personally meaningful. When a letter from a remote administrator tells employees that they should increase production, the employees tend to feel manipulated and not particularly motivated to meet the goal. Before assigning difficult goals, good managers try to ensure that employees accept those goals (Klein et al., 1999). They include employees in the goal-setting process, make sure that the employees have the skills and resources to reach the goal, and emphasise the benefits to be gained from success – perhaps including financial incentives (Locke & Latham, 1990). Second, effective goals are specific and concrete (Locke & Latham, 2002).The goal of ‘doing better’ is usually not a strong motivator because it provides no direction about how to proceed and fails to specify when the goal has been met. A specific target, such as increasing sales by 10 per cent, is a far more motivating goal. It can be measured objectively, allowing feedback on progress, and it tells workers whether the goal has been reached. Finally, goals are most effective if management supports the workers’ own goal setting, offers special rewards for reaching goals, and gives encouragement for renewed efforts after failure (Kluger & DeNisi, 1998). In summary, motivating jobs offer personal challenges, independence, and both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards (see the Snapshot ‘Success in the workplace’). They provide enough satisfaction for people to feel excitement and pleasure in working hard (Burke & Fiksenbaum, 2009). For employers, the rewards are more productivity, less absenteeism and greater employee loyalty (Ilgen & Pulakos, 1999). Achievement and wellbeing Some people believe that the more they achieve at work and elsewhere, and the more money and other material goods they amass as a result, the happier they will be. Are they right? Researchers in 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 506 26/07/17 11:22 AM 10.4 Achievement motivation the field of positive psychology have become increasingly interested in the systematic study of what it actually takes to achieve happiness, or more formally, wellbeing (Seligman et al., 2005; Sheldon & King, 2001). Wellbeing (also known as subjective wellbeing) is a combination of a cognitive judgement of satisfaction with life and the frequent experiencing of positive moods and emotions (Samuel, Bergman & Hupka-Brunner, 2013). Impact of events wellbeing a combination of a cognitive judgement of satisfaction with life and the frequent experiencing of positive moods and emotions: also known as subjective wellbeing Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Research on wellbeing indicates that, as you might expect, people living in extreme poverty or in war-torn or politically chaotic countries are not as happy as people in better circumstances (Diener et al., 2010). People everywhere react to good or bad events with corresponding changes in mood. As described in Chapter 12, ‘Health, stress and coping’, for example, severe or long-lasting stressors – such as the death of a loved one – can lead to psychological and physical problems. Although events do have an impact, the depressing or elevating effects of major changes, such as being promoted or fired, or even being imprisoned, seriously injured or disabled, tend not to last as long as we might think they would (Abrantes-Pais et al., 2007; Gilbert et al., 2004). In other words, how happy you are may have less to do with what happens to you than you might expect (Bartels, 2015). Most event-related changes in mood subside within days or weeks, and most people then return to their previous level of happiness (Suh, Diener & Fujita, 1996). Even when events create permanent changes in circumstances, most people adapt by changing their expectancies and goals, not by radically and permanently changing their baseline level of happiness (for example, Smith et al., 2009). For example, people may be thrilled after getting a big salary increase, but as they get used to having it, the thrill fades, and they may eventually feel just as underpaid as before. In fact, although there are exceptions (Fujita & Diener, 2005; Lucas, 2007), most people’s level of subjective wellbeing tends to be remarkably stable throughout their lives. This baseline level may be related to temperament or personality, and it has been likened to a set point for body weight (Lykken, 1999). 507 Influence of genetics Like many other aspects of temperament, our baseline level of happiness may be influenced by genetics. Twin studies have shown, for example, that individual differences in happiness are more strongly associated with inherited personality characteristics than with environmental factors such as money, popularity or physical attractiveness (Lykken, 1999; Tellegen et al., 1988). Other influences on wellbeing Beyond inherited tendencies, the things that appear to matter most in generating happiness are close social ties (including friends and a satisfying marriage or partnership), religious faith, and having the resources necessary to allow progress towards one’s goals (Diener, 2000; Mehl et al., 2010; Myers, 2000). So you don’t have to be a rich, physically attractive high achiever to be happy, and it turns out that most people in Western cultures are relatively happy (Stone et al., 2010). These results are consistent with the views expressed over many centuries by philosophers, psychologists and wise people in all cultures (Ekman et al., 2005). As discussed in Chapter 13, ‘Personality’, for example, Abraham Maslow (1970) noted that when people in Western cultures experience unhappiness and psychological problems, those problems can often be traced to a deficiency orientation. He said that these people seek happiness by trying to acquire the goods and reach the status they don’t currently have – but think they need – rather than by appreciating life itself and the material and non-material riches they already have. Others have amplified this point, suggesting that efforts to get more of the things we think will bring happiness may actually contribute to unhappiness if what we get is never ‘enough’ (Diener & Seligman, 2004; Luthar & Latendresse, 2005; 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 507 26/07/17 11:22 AM 508 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Nickerson et al., 2003; Quoidbach et al., 2010). Indeed, the old saying that ‘life is a journey, not a destination’ suggests that we are more likely to find happiness by experiencing full engagement in what we are doing rather than by focusing on what we are or are not getting. Relations and conflicts among motives Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Maslow’s ideas about deficiency motivation were part of his more general view of human behaviour as reflecting a hierarchy of needs, or motives (see Figure 10.5). Needs at the lowest level of the hierarchy, he said, must be at least partially satisfied before people can be motivated by higher-level goals. From the bottom to the top of Maslow’s hierarchy, these five needs are as follows: 1 physiological, such as the need for food, water, oxygen and sleep 2 safety, such as the need to be cared for as a child and have a secure income as an adult 3 belongingness and love, such as the need to be part of groups and to participate in affectionate sexual and non-sexual relationships 4 esteem, such as the need to be respected as a useful, honourable individual 5 self-actualisation, which means reaching one’s fullest potential – people motivated by this need explore and enhance relationships with others; follow interests for intrinsic pleasure rather than for money, status or esteem; and are concerned with issues affecting all people, not just themselves. FIGURE 10.5 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs Abraham Maslow (1970) saw human needs or motives as organised in a hierarchy in which those at lower levels take precedence over those at higher levels. According to this view, self-actualisation is the essence of mental health, but Maslow recognised that only rare individuals, such as Mother Teresa or Martin Luther King Jr, approach full self-actualisation. TRY THIS Take a moment to consider which level of Maslow’s hierarchy you are focused on at this point in your life. Which level do you ultimately hope to reach? Self-actualisation (i.e., maximising one's potential) Esteem (e.g., respect) Belongingness and love (e.g., acceptance, affection) Safety (e.g., nurturance, money) Physiological (e.g., food, water, oxygen) Adapted from Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. Maslow’s hierarchy has been very influential over the years, partly because the needs associated with basic survival and security do generally take precedence over those related to self-enhancement or personal growth (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Critics, however, see the hierarchy as far too simplistic (Hall, Lindzey & Campbell, 1998; Neher, 1991). It does not predict or explain, for example, the motivation of people who starve themselves to death to draw attention to political or moral causes. Furthermore, people may not have to satisfy one kind of need before addressing others; we can seek several needs at once. Finally, the ordering of needs within the survival and security category and the enhancement and growth category differs from culture to culture, suggesting that there may not be a single, universal hierarchy of needs. Alternatives to Maslow’s theory To address some of the problems in Maslow’s theory, Clayton Alderfer (1969) proposed existence, relatedness and growth theory (ERG theory), which places human needs into just three categories: existence needs (such as for food and water), relatedness needs (for example, for social interactions and 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 508 26/07/17 11:22 AM 509 10.4 Achievement motivation LINKAGES Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Conflicting motives and stress ly attachments) and growth needs (such as for developing one’s capabilities). Unlike Maslow, Alderfer doesn’t assume that these needs must be satisfied in a particular order. Instead, he sees needs in each category as rising and falling from time to time and from situation to situation. When a need in one area is fulfilled, or even if it is frustrated, a person will be motivated to pursue some other needs. For example, if a break-up frustrates relatedness needs, a person might focus on existence or growth needs by eating more or volunteering to work late. More recently, Douglas Kenrick and his colleagues (2010) have proposed that Maslow’s original hierarchy should be expanded and adjusted rather than discarded. They offer a revised hierarchy based on evolutionary theory in which the need for self-actualisation is replaced by three others: the need to find a mate, the need to keep a mate, and the need to become a parent. As in the case of hunger strikes, in which the desire to promote a cause is pitted against the desire to eat, human motives can sometimes conflict. The usual result is some degree of discomfort. For example, imagine that you are alone and bored on a Saturday night, and you think about going to the local shop to buy some snacks. What are your motives? Hunger might prompt you to go out, as might the prospect of increased arousal that a change of scene will provide. Even sexual motivation might be involved as you fantasise about meeting someone exciting in the snack food aisle. However, safety-related motives may also kick in: Is your neighbourhood safe enough for you to go out alone at night? An esteem motive might come into play, too, making you hesitate to be seen on your own on a weekend night. These are just a few motives that may shape a trivial decision. When the decision is more important, the number and strength of motivational pushes and pulls are often greater, creating far more internal conflict. Four basic types of motivational conflict have been identified (Elliot, 2008; Miller, 1959): 1 Approach–approach conflicts. When a person must choose only one of two desirable activities – say, going with friends to a movie or to a party – an approach– approach conflict exists. 2 Avoidance–avoidance conflicts. An avoidance–avoidance conflict arises when a person must pick one of two undesirable alternatives. Someone forced either to sell the family home or to declare bankruptcy faces an avoidance–avoidance conflict. 3 Approach–avoidance conflicts. If someone you dislike had tickets to your favourite group’s sold-out concert and invited you to come LINKAGES along, what would you do? When a single event or Can motivational activity has both attractive conflicts cause stress? (a link to and unattractive features, Chapter 12, ‘Health, an approach–avoidance stress and coping’) conflict is created. 4 Multiple approach–avoidance conflicts. Suppose that you must choose between two jobs. One offers a good salary with a well-known company, but it requires long hours and relocation to a less preferable climate. The other boasts advancement opportunities, fringe benefits and a better climate, but also lower pay and an unpredictable work schedule. This is an example of a multiple approach–avoidance conflict, in which two or more alternatives each have both positive and negative features. Such conflicts are difficult to resolve partly because it may be hard to compare the features of each option. For example, how much more money per year does it take to compensate you for living in a climate you hate? In fact, all of these conflicts can be difficult to resolve and can create significant emotional arousal and other signs of stress, a topic described in Chapter 12, ‘Health, stress and coping’ (also see the Snapshot ‘A stressful conflict’). Most people in the midst of motivational conflicts are tense, irritable and more vulnerable than usual to physical and psychological problems. These reactions are especially likely when none of the choices available is obviously ‘right’, when conflicting motives have approximately equal strength, and when the final choice can have serious >>> 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 509 26/07/17 11:22 AM 510 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion consequences (as in decisions about marrying, splitting up or placing an elderly parent in a nursing home). People may take a long time to resolve these conflicts, or they may act impulsively and thoughtlessly, if only to end the discomfort of uncertainty. Even after resolving a conflict on the basis of careful thought, people may continue to experience stress responses such as worrying about whether they made the right decision or blaming themselves for bad choices. These and other consequences of conflicting motives can even lead to depression or other serious disorders. Snapshot ly Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On TRY THIS Think back to the time when you were deciding about which university to attend, or whether you could or should go to university at all. Was the decision easy and obvious, or did it create a motivational conflict? If there was a conflict, was it an approach–approach, approach– avoidance, avoidance–avoidance or multiple approach– avoidance conflict? What factors were most important in deciding how to resolve the conflict, and what emotions and signs of stress did you experience during and after the decision-making process? Alamy Stock Photo/Marmaduke St. John A stressful conflict Opponent processes, motivation and emotion Resolving approach–avoidance conflicts is often complicated by the fact that some behaviours have more than one emotional effect, and those effects may be opposite to one another. People who ride roller-coasters or skydive, for example, often say that the experience is scary but also thrilling. How do they decide whether or not to repeat these behaviours? One answer lies in the changing value of incentives and the regulation of arousal described in Richard Solomon’s opponent-process theory, which is discussed in Chapter 5, ‘Learning’. Opponent-process theory is based on two assumptions. The first is that any reaction to a stimulus is followed by an opposite reaction, called the opponent process. For example, being startled by a sudden sound is typically followed by relaxation and relief. Second, after repeated exposure to the same stimulus, the initial reaction weakens and the opponent process becomes quicker and stronger. Research on opponent-process theory has revealed a predictable pattern of emotional changes that helps explain some people’s motivation to repeatedly engage in arousing but fearsome activities, such as skydiving. Before each of their first few jumps, people usually experience stark terror, followed by intense relief when they reach the ground. With more experience, however, the terror becomes mild anxiety, and what had been relief grows to a sense of elation that may start to appear during the activity (Solomon, 1980). As a result, said Solomon, some people’s motivation to pursue skydiving and other ‘extreme sports’ can become a virtual addiction. Opponent-process theory has also been used to improve our understanding of the effects of pain-relieving drugs (Leknes et al., 2008;Vargas-Perez et al., 2007). The emotions associated with motivational conflicts and with the operation of opponent processes provide just two examples of the close ties between motivation and emotion. Motivation can intensify emotion, as when a normally calm but extremely hungry person makes an angry phone call about a late pizza delivery. Emotions can also create motivation (Brehm, Miron & Miller, 2009). So let’s take a closer look at emotions. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 510 26/07/17 11:22 AM 511 10.5 The nature of emotion IN REVIEW Achievement motivation ASPECTS DESCRIPTION Definition and development Achievement motivation is the degree to which a person establishes specific goals, cares about meeting those goals, and experiences feelings of satisfaction by doing so. Achievement motivation develops in early childhood, under the influence of both genetic and environmental (parental and cultural) forces. Goal setting and achievement motivation Differences in achievement motivation appear in the kinds of goals people seek in achievementrelated situations. ly Achievement and success Factors include the importance of job satisfaction and extrinsic rewards such as money. in the workplace Clear goals are one way of increasing both job performance and job satisfaction. Relations and conflicts among motives Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs are as follows: physiological, such as the need for food, water, oxygen and sleep safety, such as the need to be cared for as a child and have a secure income as an adult belongingness and love, such as the need to be part of groups and to participate in affectionate sexual and non-sexual relationships esteem, such as the need to be respected as a useful, honourable individual self-actualisation, which means reaching one’s fullest potential. Opponent processes Any reaction to a stimulus is followed by an opposite reaction; for example, being startled by a sudden sound is typically followed by relaxation and relief. After repeated exposure to the same stimulus, the initial reaction weakens and the opponent process becomes quicker and stronger. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Achievement and wellbeing Wellbeing is a combination of a cognitive judgement of satisfaction with life and the frequent experiencing of positive moods and emotions (also called subjective wellbeing). Events impact on wellbeing – we react to good or bad events with corresponding changes in mood – as do genetics, in terms of temperament. Also important are social ties (including friends and a satisfying marriage or partnership), religious faith and having the resources necessary to allow progress towards one’s goals. Check your understanding 1 There is some evidence that differing emotions such as and can affect how successful our efforts are in relation to achievement motivation levels. when we recognise a discrepancy between our current situation and how we 2 Psychologists have found that we want that situation to be. can be replaced by three other needs: the need to find a mate, the need to keep a 3 In revising Maslow’s model, mate, and the need to become a parent. 10.5 THE NATURE OF EMOTION Everyone seems to agree that joy, sorrow, anger, fear, love and hate are emotions, but it is hard to identify exactly what it is that makes these experiences emotions rather than, say, thoughts or impulses. In fact, some cultures see emotion and thought as the same thing. The Chewong of Malaysia, for example, consider the liver the seat of both what we call thoughts and feelings (Russell, 1991). 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 511 26/07/17 11:22 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Winners and losers Snapshot Most psychologists in Western cultures see emotions as organised psychological and physiological reactions to changes in our relationship to the world. These reactions are partly private, or subjective, experiences and partly objective, measurable patterns of behaviour and physiological arousal. The subjective experience of emotion has several characteristics: 1 Emotion is usually temporary; it tends to have a relatively clear beginning and end, as well as a relatively short duration. Moods, by contrast, tend to last longer. 2 Emotional experience can be positive, as in joy, or negative, as in sadness. It can also be a mixture of both, as in the bittersweet feelings parents experience when watching their child leave for the first day of kindergarten. 3 Emotional experience alters thought processes, often by directing attention towards some things and away from others. Negative emotions, such as fear, tend to narrow attention. So anxiety about terrorism, for example, might lead you to focus your attention on potential threats in airports and other public places (Nobata, Hakoda & Ninose, 2010;Yovel & Mineka, 2005). Positive emotions tend to widen our attention, which makes it easier to take in a broader range of visual information and perhaps to think more broadly too (Fredrickson et al., 2008). 4 Emotional experience triggers an action tendency, the motivation to behave in certain ways. Positive emotions, such as joy, contentment and pride, often lead to playfulness, creativity and exploration of the environment (Cacioppo, Gardner & Berntson, 1999; Fredrickson, 2001). These behaviours, in turn, can generate further positive emotions by creating stronger social ties, greater skill at problem solving, and the like. The result may be an ‘upward spiral’ of positivity (Burns et al., 2008). Negative emotions, such as sadness and fear, often promote withdrawal from threatening situations, whereas anger might lead to actions aimed at revenge or constructive change. Grieving parents’ anger, for example, might motivate them to harm their child’s killer. For John Walsh, whose son was kidnapped and murdered, grief led him to help prevent such crimes by creating America’s Most Wanted, a TV show dedicated to bringing criminals to justice. 5 Emotional experiences are passions that you feel, usually whether you want to or not.You can exert at least some control over emotions in the sense that they depend partly on how you interpret situations (Gross, 2001). For example, your emotional reaction might be less extreme after a car accident if you remind yourself that no-one was hurt and that you are insured. Still, such control is limited.You cannot decide to experience joy or sorrow; instead, you ‘fall in love’ or ‘explode in anger’ or are ‘overcome by grief ’. In other words, the subjective aspects of emotions are both triggered by the thinking self and felt as happening to the self. They reveal each of us as both agent and object, both I and me, both the controller of thoughts and the recipient of passions. The extent to which we are ‘victims’ of our passions versus rational designers of our emotions is a central dilemma of human existence, as much a subject of philosophy and literature as of psychology. The objective aspects of emotion include learned and innate expressive displays and physiological responses. Expressive displays – such as a smile or a frown – communicate feelings to others. Physiological responses – such as changes in heart rate – are the biological adjustments needed to perform the action tendencies generated by emotional experience. If you throw a tantrum or jump for joy, your heart must deliver additional oxygen and fuel to your muscles (see the Snapshot ‘Winners and losers’). In summary, emotions are temporary experiences with either positive, negative or mixed qualities. People experience emotion with varying intensity, as happening to them, as generated in part by a mental assessment of situations, and accompanied by both learned and innate physical responses.Through emotion, whether they mean to or not, people communicate their internal states Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Getty Images/Stringer Emotional experiences depend in part on our interpretation of situations and how those situations relate to our goals. A single event – the announcement of the results of this match – triggered drastically different emotional reactions in the contestants, depending on whether it made them the winner or the loser. Similarly, an exam score of 75 per cent may thrill you if your best previous score had been 50 per cent, but it may upset you if you had never before scored below 90 per cent. Defining characteristics ly 512 emotions transitory positive or negative experiences that are felt as happening to the self, are generated in part by cognitive appraisal of a situation, and are accompanied by both learned and innate physical responses 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 512 26/07/17 11:22 AM 10.5 The nature of emotion 513 and intentions to others. Emotion often disrupts thinking and behaviour, but it also triggers and guides thinking, and organises, motivates and sustains behaviour and social relations (Izard, 2007). The biology of emotion The role of biology in emotion can be seen in mechanisms of the central nervous system and the autonomic nervous system. In the central nervous system, several brain areas are involved in the generation of emotions, as well as in our experience of those emotions (Barrett & Wager, 2006). The autonomic nervous system gives rise to many of the physiological changes associated with emotional arousal. Brain mechanisms Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Although many questions remain, researchers have described three main aspects of how emotion is processed in the brain. These are in the limbic system, through facial expressions, and involving the cerebral cortex. Response in the limbic system First, it appears that activity in the limbic system, especially in the amygdala, is central to emotion (Kensinger & Corkin, 2004; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; see Figure 10.6). Normal functioning in the amygdala appears critical to learning emotional associations, recognising emotional expressions, and perceiving emotionally charged words (for example, Anderson & Phelps, 2001; Suslow et al., 2006). In one brain-imaging study, when researchers paired an uncomfortably loud noise with pictures of faces, the participants’ brains showed activation of the amygdala while the noise– picture association was being learned (LaBar et al., 1998). In another study, victims of a disease that destroys only the amygdala were found to be unable to judge other people’s emotional states by looking at their faces (Adolphs et al., 1994). Faces that normal people rated as expressing strong negative emotions were rated by the amygdala-damaged individuals as approachable and trustworthy (Adolphs, Tranel & Damasio, 1998). FIGURE 10.6 Brain regions involved in emotions Incoming sensory information alerts the brain to an emotion-evoking situation. Most of the information goes through the thalamus. The cingulate cortex and hippocampus are involved in the interpretation of this sensory input. Output from these areas goes to the amygdala and hypothalamus, which control the autonomic nervous system via brain-stem connections. There are also connections from the thalamus directly to the amygdala. The locus coeruleus is an area of the brain stem that causes both widespread arousal of cortical areas and changes in autonomic activity. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 513 Frontal cortex Basal ganglia Thalamus Hypothalamus Pituitary Cingulate cortex Hippocampus Amygdala Sensory input Locus coeruleus Spinal cord Activation of autonomic nervous system 26/07/17 11:22 AM 514 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Facial expressions The cerebral cortex ly A second aspect of the brain’s involvement in emotion is its control over emotional and nonemotional facial expressions. TRY THIS Take a moment to look in a mirror and put on your best fake smile.The voluntary facial movements you just made, like all voluntary movements, are controlled by the pyramidal motor system, a brain system that includes the motor cortex (see Figure 3.12 and Figure 3.13 in Chapter 3, ‘Biological aspects of psychology’). However, a smile that expresses genuine happiness is involuntary.That kind of smile, like the other facial movements associated with emotions, is governed by the extrapyramidal motor system, which depends on areas beneath the cortex. Brain damage can disrupt either system. People with pyramidal motor system damage show normal facial expressions during genuine emotion, but they cannot fake a smile. In contrast, people with damage to the extrapyramidal system can pose facial expressions at will, but they remain expressionless even when feeling joy or sadness (Hopf, Muller & Hopf, 1992). Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On A third aspect of the brain’s role in emotion is revealed by research on the cerebral cortex and particularly on differences in the activity of its two hemispheres in relation to emotional experience. For example, after suffering damage to the right but not the left hemisphere, people no longer laugh at jokes, even though they can still understand the jokes’ words, their logic (or illogicality) and their punchlines (Critchley, 1991). Brain-imaging studies of sports fans watching their favourite team in action have revealed greater activation in the left hemisphere when their team is ahead and more activation in the right hemisphere when their team is behind (Park et al., 2009).There is also evidence that the experience of anger and depression is associated with greater brain activity on the right side than on the left (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Herrington et al., 2010). So the brain’s two hemispheres appear to make somewhat different contributions to the perception, experience and expression of emotion (Davidson, 2000; Davidson, Shackman & Maxwell, 2004). Furthermore, different brain areas can be involved in displaying and experiencing positive and negative emotions (Harmon-Jones, 2004; Harmon-Jones & Sigelman, 2001; Heller, 1993). As a result, it is extremely challenging for neuroscientists to map the brain’s role in emotion (Bourne, 2010; Root, Wong & Kinsbourne, 2006;Vingerhoets, Berckmoes & Stroobant, 2003). Mechanisms of the autonomic nervous system sympathetic nervous system the subsystem of the autonomic nervous system that usually prepares the organism for vigorous activity parasympathetic nervous system the subsystem of the autonomic nervous system that typically influences activity related to the protection, nourishment and growth of the body 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 514 The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is involved in many of the physiological changes that accompany emotions (see Figure 10.7). If your hands get cold and clammy when you are nervous, it is because the ANS has increased perspiration and decreased the blood flow in your hands. As described in Chapter 3, ‘Biological aspects of psychology’, the ANS carries information between the brain and most organs of the body – the heart and blood vessels, the digestive system and so on. Each of these organs has its own ongoing activity, but ANS input increases or decreases this activity. By doing so, the ANS coordinates the functioning of these organs to meet the body’s general needs and to prepare it for change. If you are aroused to take action – to run to catch a bus, say – you need more glucose to fuel your muscles. The ANS frees needed energy by stimulating secretion of glucose-generating hormones and promoting blood flow to the muscles. Organisation of the ANS As shown in Figure 10.7, the autonomic nervous system is organised into two divisions: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. Emotions can activate either of these divisions, both of which send axon fibres to each organ in the body. Generally, 26/07/17 11:22 AM 515 10.5 The nature of emotion FIGURE 10.7 The autonomic nervous system Emotional responses involve activation of the autonomic nervous system, which includes sympathetic and parasympathetic subsystems. TRY THIS Look at the bodily responses depicted here and make a list of the ones that you associate with emotional experiences. Dilates pupil Stimulates salivation Inhibits salivation Sympathetic ganglion Slows respiration Increases respiration Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Noradrenaline released ly Constricts pupil Target organ Acetylcholine released Parasympathetic ganglion Slows heartbeat Accelerates heartbeat Stimulates gallbladder Stimulates glucose release Stimulates digestion Inhibits digestion Secretes adrenaline and noradrenaline Contracts bladder Relaxes bladder Stimulates genitals Inhibits genitals the sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres have opposite effects on these target organs. Axons from the parasympathetic system release acetylcholine onto target organs, leading to activity related to the protection, nourishment and growth of the body. For example, parasympathetic activity increases digestion by stimulating movement of the intestinal system so that more nutrients are taken from food.Axons from the sympathetic system release a different neurotransmitter, noradrenaline, onto target organs, helping prepare the body for vigorous activity. When one part of the sympathetic system is stimulated, other parts are activated ‘in sympathy’ with it. For example, input from sympathetic neurons to the adrenal medulla causes that gland to release noradrenaline and adrenaline into the bloodstream, thereby activating all sympathetic target organs (see Figure 12.3 in Chapter 12, ‘Health, stress and coping’).The result is the fight–flight syndrome (also called the fight-or-flight reaction), a pattern of increased heart rate and blood pressure, rapid or irregular breathing, dilated pupils, perspiration, dry mouth, increased blood sugar, piloerection (‘goosebumps’) and other changes that help prepare the body to combat or run from a threat. The ANS is not directly connected to brain areas involved in consciousness, so sensations about organ activity reach the brain at a non-conscious level.You may hear your stomach grumble, but you can’t actually feel it secrete acids. Similarly, you can’t consciously experience the brain mechanisms 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 515 fight–flight syndrome (fight-or-flight reaction) a physical reaction triggered by the sympathetic nervous system that prepares the body to fight or to run from a threatening situation 26/07/17 11:22 AM 516 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion that alter the activity of your autonomic nervous system. This is why most people don’t have direct, conscious control over blood pressure or other aspects of ANS activity. However, there are things you can do to indirectly affect the ANS. For example, to create autonomic stimulation of your sex organs, you might imagine an erotic situation. To raise your blood pressure, you might hold your breath or strain your muscles; to lower it, you can lie down, relax and think calming thoughts, or engage in various forms of meditation (Greeson, 2009; see Chapter 8, ‘Consciousness’). IN REVIEW ASPECTS The subjective experience of emotion has several characteristics: emotion is usually temporary emotional experience can be positive or negative emotional experience alters thought processes emotional experience triggers an action tendency emotional experiences are passions that you feel. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Defining characteristics DESCRIPTION ly The nature of emotion The biology of emotion Brain mechanisms: the amygdala is central to emotion control over emotional and non-emotional facial expressions differences in the activity of the two hemispheres of the cerebral cortex in relation to emotional experience Autonomic nervous system mechanisms: sympathetic nervous system usually prepares the organism for vigorous activity parasympathetic nervous system typically influences activity related to the protection, nourishment and growth of the body Check your understanding 1 2 The 3 The are temporary experiences with positive, negative or mixed qualities. is involved in many of the physiological changes that accompany emotions. helps prepare the body to combat or run from a threat. 10.6 THEORIES OF EMOTION How does activity in the brain and the autonomic nervous system relate to the emotions we experience? Are autonomic responses to events enough to create the experience of emotion, or are those responses the result of emotional experiences that begin in the brain? And how are emotional reactions affected by the way we think about events? For over a century, psychologists have searched for the answers to these questions. In the process, they have developed a number of theories that explain emotion primarily in terms of biological or cognitive factors. The main biological theories are those of William James and Walter Cannon. The most prominent cognitive theories are those of Stanley Schachter and Richard Lazarus. In this section, we review these theories, along with some research designed to evaluate them. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 516 26/07/17 11:22 AM 10.6 Theories of emotion 517 James’ peripheral theory Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly When you go camping and find a snake in your tent, you would probably be afraid and run away. But would you run because you are afraid, or would you be afraid because you ran? The example and the question come from William James, who in the late 1800s offered one of the first formal accounts of how physiological responses relate to emotional experience. James argued that you are afraid because you run.Your running and the physiological responses associated with it, he said, follow directly from your perception of the snake.Without these physiological responses, you would feel no fear, because, said James, recognition of physiological responses is fear. James saw activity in the peripheral nervous system as the cause of emotional experience, and his theory is known as a peripheral theory of emotion. At first, James’ theory might seem ridiculous; it doesn’t make sense to run from something unless you already fear it. James (1890) concluded otherwise after examining his own mental processes. He decided that once you strip away all physiological responses, nothing remains of the experience of an emotion. Emotion, he reasoned, must therefore be the result of experiencing a particular set of physiological responses. A similar argument was offered by Carl Lange, a Danish physician, so James’ view is sometimes called the James–Lange theory of emotion. Observing peripheral responses Figure 10.8 outlines the components of emotional experience, including those emphasised by James. First, a perception affects the cerebral cortex, said James; ‘then quick as a flash, reflex currents pass down through their pre-ordained channels, alter the condition of muscle, skin and viscus; and these alterations, perceived, like the original object, in as many portions of the cortex, combine with it in consciousness and transform it from an object-simply-apprehended into an object-emotionally-felt’ (James, 1890, p. 759). In other words, the brain interprets a situation and automatically directs a particular set of peripheral physiological changes – a racing heart, sinking stomach, facial grimace, perspiration and certain patterns of blood flow.We are not conscious of the process, said James, until we become aware of these bodily changes; at that point, we experience an emotion. One implication of this view is that each particular emotion is created by a particular pattern of physiological responses. For example, fear would follow from one pattern of bodily responses, and anger would follow from a different pattern. Notice that according to James’ view, emotional experience is not generated by activity in the brain alone. There is no special ‘emotion centre’ in the brain where the firing of neurons creates a direct experience of emotion. If this theory is accurate, it might account for the difficulty we sometimes have in knowing our true feelings: we must figure out what emotions we feel by perceiving slight differences in specific physiological response patterns (Katkin, Wiens & Öhman, 2001). Evaluating James’ theory The English language includes more than 500 labels for emotions (Averill, 1980). Does a different pattern of physiological activity precede each of these specific emotions? Probably not, but research shows that certain emotional states are indeed associated with certain patterns of autonomic activity (Christie & Friedman, 2004; Craig, 2002; Damasio et al., 2000). For example, blood flow to the hands and feet increases in association with anger and declines in association with fear (Levenson, Ekman & Friesen, 1990). So fear involves ‘cold feet’; anger does not. A pattern of activity associated with disgust includes increased muscle activity but no change in heart rate. Even when people mentally relive different kinds of emotional experiences, they show patterns of autonomic activity associated with those emotions (Ekman, Levenson & Friesen, 1983).These emotion-specific patterns of physiological activity have been found in widely different cultures (Levenson et al., 1992). It has even been suggested that the ‘gut feelings’ that cause us to approach or avoid certain situations might 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 517 26/07/17 11:22 AM 518 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion FIGURE 10.8 Components of emotion Emotion is associated with activity in the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord), as well as with responses elsewhere in the body (called peripheral responses), and with cognitive interpretations of events. Emotion theorists have differed about which of these components is essential for emotion. William James focused on the perception of peripheral responses, such as changes in heart rate. Walter Cannon said that emotion could occur entirely within the brain. Stanley Schachter emphasised cognitive factors, including how we interpret events and how we label our peripheral responses to them. 2. Cognitive interpretation (That snake can kill me!) 3. Activation of CNS and peripheral nervous system (Cannon) Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly 1. Sensation/perception (It's a snake!) 5. Perception of peripheral responses (James) 6. Cognitive interpretation of peripheral responses (Schachter) 4. Peripheral responses (e.g., increase in heart rate, change in facial expression) be the result of physiological changes that are perceived without conscious awareness (Bechara et al., 1997; Damasio, 1994; Katkin, Wiens & Öhman, 2001; Winkielman & Berridge, 2004). Autonomic activity and facial expressions Different patterns of autonomic activity are closely tied to specific emotional facial expressions. In one study, when participants were asked to make certain facial movements, autonomic changes occurred that resembled those normally accompanying emotion (Ekman, Levenson & Friesen, 1983; see Figure 10.9). Almost all these participants also reported feeling the emotion – such as fear, anger, disgust, sadness or happiness – associated with the expression they had created, even though they could not see their own expressions and did not realise that they had portrayed a specific emotion. To get an idea of how facial expressions can alter – as well as express – emotion, look at TRY THIS 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 518 26/07/17 11:23 AM 10.6 Theories of emotion 0.3 0.2 4 Change Change 5 3 0 2 –0.1 1 Heart rate Finger temperature (A) (B) 0.6 0.012 0.5 0.008 0.4 0.004 Change Change 0.1 Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On In this experiment, facial movements characteristic of different emotions produced different patterns of change in (A) heart rate; (B) peripheral blood flow, as measured by finger temperature; (C) skin conductance; and (D) muscle activity (Levenson, Ekman & Friesen, 1990). For example, making an angry face caused heart rate and finger temperature to rise, whereas making a fearful face raised heart rate but lowered finger temperature. 6 ly FIGURE 10.9 Physiological changes associated with different emotions 519 0.3 0 0.2 –0.004 0.1 –0.008 Skin conductance Muscle activity (D) (C) Anger Sadness Happiness Fear Disgust Surprise From Levenson, R. W., Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1990). Voluntary facial action generates emotion-specific autonomic nervous system activity. Psychophysiology, 27, 363–384. a photograph of someone whose face is expressing a strong emotion and try your best to imitate it. Did this create in you the same feelings that the other person appears to be experiencing? The emotional effects of this kind of ‘face making’ appear strongest in people who are the most sensitive to internal bodily cues. Physiology and emotion James’ theory implies that the experience of emotion would be blocked if a person were unable to detect physiological changes occurring in the body’s periphery. So spinal cord injuries that reduce feedback from peripheral responses should reduce the intensity of emotional experiences. Indeed, some people with such injuries have reported reductions in the intensity of their emotions, especially if the injuries are at higher points in the spinal cord, which cuts off feedback from more areas of the body (Hohmann, 1966). Brain-imaging studies, too, show differences in the processing of emotional stimuli by people with spinal cord injuries (Nicotra et al., 2006). However, most studies show that when people with spinal injuries continue to pursue their life goals, they experience a full range of emotions, including as much happiness as non-injured people (for example, Bermond et al., 1991; Cobos et al., 2004).These people report that their emotional experiences are just as intense as before their injuries, even though they notice less intense physiological changes associated with their emotions. Lie detection James’ view that different patterns of physiological activity are associated with different emotions forms the basis for the lie detection industry. If people experience anxiety or guilt when they lie, specific patterns of physiological activity accompanying these emotions should be detectable on 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 519 26/07/17 11:23 AM 520 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Accuracy of measurement ly instruments, called polygraphs, that record heart rate, breathing, perspiration and other autonomic responses (Granhag & Stromwall, 2004; Iacono & Patrick, 2006). To examine a criminal suspect using the control question test, a polygraph operator would ask questions specific to the crime, such as, ‘Did you stab anyone on 6 November 2016?’ Responses to such relevant questions are then compared with responses to control questions, such as, ‘Have you ever lied to get out of trouble?’ Innocent people may have lied at some time in the past and might feel guilty when asked about it, but they should have no reason to feel guilty about what they did on 6 November 2016. So an innocent person should have a stronger emotional response to control questions than to relevant questions (Rosenfeld, 1995). Another approach, called the directed lie test, compares a person’s physiological reactions when asked to lie about something and when telling what is known to be the truth. Finally, the guilty knowledge test seeks to determine if a person reacts in a notable way to information about a crime that only the criminal would know (Ben-Shakhar, Bar-Hillel & Kremnitzer, 2002). Most people do have emotional responses when they lie, but statistics about the accuracy of polygraphs are difficult to obtain. Estimates vary widely, from those suggesting that polygraphs detect 90 per cent of guilty, lying individuals (Gamer et al., 2006; Honts & Quick, 1995; Kircher, Horowitz & Raskin, 1988; Raskin, 1986) to those suggesting that polygraphs mislabel as many as 40 per cent of truthful, innocent people as guilty liars (Ben-Shakhar & Furedy, 1990; Saxe & Ben-Shakhar, 1999). Obviously, the results of a polygraph test are not determined entirely by whether a person is telling the truth.What people think about the act of lying and about the value of the test can also influence the accuracy of its results. For example, people who consider lying acceptable –and who do not believe in the power of polygraphs – are unlikely to display emotion-related physiological responses while lying during the test. However, an innocent person who believes in such tests and who thinks that ‘everything always goes wrong’ might show a large fear response when asked about a crime, thus wrongly suggesting guilt (Lykken, 1998b). Fooling the polygraph Polygraphs can catch some liars, but most researchers agree that a guilty person can ‘fool’ a polygraph and that some innocent people can be mislabelled as guilty (Ruscio, 2005). After reviewing the relevant research literature, a panel of distinguished psychologists and other scientists in the United States expressed serious reservations about the value of polygraph tests in detecting deception and argued against their use as evidence in court or in employee screening and selection (Committee to Review the Scientific Evidence on the Polygraph, 2003); in Australia and New Zealand, meanwhile, the use of polygraphs has not been tested within each country’s high court. Scientists are now working on other lie-detecting techniques that focus on brain activity and brief facial ‘microexpressions’ to assist in areas of law and security (Yan et al., 2013). Cannon’s central theory James said the experience of emotion depends on feedback from physiological responses occurring outside the brain, but Walter Cannon disagreed. According to Cannon (1927), you feel fear at the sight of a snake even before you start to run. He said that emotional experience starts in the central nervous system – specifically, in the thalamus, the brain structure that relays information from most sense organs to the cortex. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 520 26/07/17 11:23 AM 10.6 Theories of emotion 521 According to Cannon’s central theory (also known as the Cannon–Bard theory, in recognition of Philip Bard’s contribution), when the thalamus receives sensory information about emotional events and situations, it sends signals to the autonomic nervous system and – at the same time – to the cerebral cortex, where the emotion becomes conscious. So when you see a snake, the brain receives sensory information about it, perceives it as a snake, and directly creates the experience of fear while at the same time sending messages to the heart, lungs and muscles to do what it takes to run away. In other words, Cannon said that the experience of emotion appears directly in the brain, with or without feedback from peripheral responses (see Figure 10.8). Updating Cannon’s theory Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Research conducted since Cannon proposed his theory indicates that the thalamus is actually not the ‘seat’ of emotion, but that through its connections to the amygdala (see Figure 10.6), the thalamus does participate in some aspects of emotional processing (Lang, 1995). For example, studies of laboratory animals and humans show that the emotion of fear is generated by connections from the thalamus to the amygdala (Anderson & Phelps, 2000; LeDoux, 1995). The implication is that strong emotions can sometimes bypass the cortex without requiring conscious thought to activate them (Feinstein, Duff & Tranel, 2010). One study showed, for example, that people presented with stimuli such as angry faces display physiological signs of arousal even if they are not conscious of seeing those stimuli (Morris et al., 1998). The same processes might explain why people find it so difficult to overcome an intense fear, or phobia, even though they may consciously know the fear is irrational. An updated version of Cannon’s theory suggests that in humans and other animals, activity in specific brain areas is experienced as either enjoyable or aversive and produces the feelings of pleasure or discomfort associated with emotion. In humans, these areas have extensive connections throughout the brain (Fossati et al., 2003). As a result, the representation of emotions in the brain probably involves activity in widely distributed neural circuits, not just in a narrowly localised emotion ‘centre’ (Derryberry & Tucker, 1992). Still, there is evidence to support the main thrust of Cannon’s theory: that emotion occurs through the activation of specific circuits in the central nervous system. What Cannon did not foresee is that different parts of the central nervous system may be activated for different emotions and for different aspects of the total emotional experience. Cognitive theories of emotion Suppose that you are about to be interviewed for your first job or go out on a blind date or take your first ride in a hot-air balloon. In situations such as these, it is not always easy to know exactly what you are feeling. Is it fear, excitement, anticipation, worry, happiness, dread or what? Stanley Schachter suggested that the emotions we experience every day are shaped partly by how we interpret the arousal we feel. His cognitive theory of emotion, known as the Schachter–Singer theory in recognition of the contributions of Jerome Singer, took shape in the early 1960s, when many psychologists were raising questions about the validity of James’ theory of emotion. Schachter argued that the theory was essentially correct – but required a few modifications (Cornelius, 1996). Schachter–Singer theory In Schachter’s view, feedback about physiological changes may not vary enough to create the many shades of emotion that people can experience. He argued instead that emotions emerge from a 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 521 26/07/17 11:23 AM 522 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion combination of feedback from peripheral responses and our cognitive interpretation of the nature and cause of those responses (Schachter & Singer, 1962). Cognitive interpretation first comes into play, said Schachter, when you perceive the stimulus that leads to bodily responses (‘It’s a snake!’). Interpretation occurs again when you identify feedback from those responses as a particular emotion (see Figure 10.8). The same physiological responses might be given many different labels, depending on how you interpret those responses. So, according to Schachter, when that snake approaches your tent, the emotion you experience might be fear, excitement, astonishment or surprise, depending on how you label your bodily reactions. Attribution Schachter also said that the labelling of arousal depends on attribution, the process of identifying the cause of an event. Physiological arousal might be attributed to one of several emotions, depending on the information available about the situation. If you are watching the final seconds of a close Rugby match, you might attribute your racing heart, rapid breathing and perspiration to excitement.You might attribute the same physiological reactions to anxiety if you are waiting for a big exam to begin. Schachter predicted that our emotional experiences will be less intense if we attribute arousal to a non-emotional cause. So if you notice your heart pounding before an exam but say to yourself, ‘Sure my heart’s racing – I just drank five cups of coffee!’ then you should feel ‘wired’ from caffeine rather than afraid or worried. This prediction has received some support (Mezzacappa, Katkin & Palmer, 1999; Sinclair et al., 1994), but other aspects of Schachter’s theory have not. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On of explaining the causes of an event ly attribution the process Excitation transfer theory excitation transfer theory the theory that physiological arousal stemming from one situation is carried over to and enhances emotional experience in an independent situation 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 522 The Schachter–Singer theory stimulated an enormous amount of valuable research, including studies of excitation transfer theory, the theory that physiological arousal stemming from one situation is carried over to and enhances emotional experience in an independent situation (Reisenzein, 1983; Zillmann, 1998). For example, people who have been aroused by physical exercise become more angry when provoked or experience more intense sexual feelings when in the company of an attractive person than people who have been less physically active (Allen et al., 1989). Arousal from fear, like arousal from exercise, can also enhance emotions, including sexual feelings. One study of this transfer took place in Canada, near a deep river gorge. The gorge could be crossed either by a shaky swinging bridge or by a more stable wooden one. A female researcher asked men who had just crossed each bridge to respond to a questionnaire that included pictures from the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), a projective test where the strength of a person’s achievement motivation is inferred from the stories they tell about TAT pictures. The amount of sexual content in the stories these men wrote about the pictures was much higher among those who met the woman after crossing the more dangerous bridge than among those who had crossed the stable bridge. Furthermore, they were more likely to rate the researcher as attractive and to attempt to contact her afterwards (Dutton & Aron, 1974). When the person giving out the questionnaire was a male, however, the type of bridge crossed had no effect on sexual imagery. To test the possibility that the men who crossed the dangerous bridge were simply more adventurous in both bridge crossing and heterosexual encounters, the researcher repeated the study, but with one change. This time, the woman approached the men farther down the trail, long after arousal from the bridge crossing had subsided. Now the apparently adventurous men were no more likely than others to rate the woman as attractive. So it was probably excitation transfer, not just differing amounts of adventurousness that produced the original result. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 10.6 Theories of emotion 523 Other theories Labelling arousal Schachter’s cognitive theory of emotion predicts that these people will attribute their physiological arousal to the game they are watching and will label their emotion ‘excitement’. Furthermore, as described in Chapter 12, ‘Health, stress and coping’, the emotions they experience will also depend partly on their cognitive interpretation of the outcome (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). If their team loses, those who see the defeat as a disaster will experience more negative emotions than those who think of it as a challenge to improve. Snapshot Getty Images/Chris Jackson Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Schachter focused on the cognitive interpretation of our bodily responses to events, but other theorists have argued that it is our cognitive interpretation of events themselves that is most important in shaping emotional experiences (see the Snapshot ‘Labelling arousal’). For example, as we mentioned earlier, a person’s emotional reaction to receiving exam results can depend partly on whether the score is seen as a sign of improvement or a grade worthy of shame. According to Richard Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, these differing reactions can be best explained by how we think exam scores, job interviews, blind dates, snake sightings and other events will affect our personal wellbeing. According to Lazarus (1966, 1991), the process of cognitive appraisal, or evaluation, begins when we decide whether or not an event is relevant to our wellbeing. That is, do we even care about it? If we don’t, as might be the case if an exam doesn’t count towards our grade, we are unlikely to have an emotional experience when we get the results. If the event is relevant to our wellbeing, we will experience an emotional reaction to it. That reaction will be positive or negative, said Lazarus, depending on whether we see the event as advancing our personal goals or obstructing them. The specific emotion we experience depends on our individual goals, needs, standards, expectations and past experiences. As a result, a particular exam score can create contentment in one person, elation in another, mild disappointment in a third person, and despair in someone else. Individual differences in goals and standards are at work, too, when a second-place finisher in a marathon experiences bitter disappointment at having ‘lost’, while someone at the back of the pack may be thrilled just to have completed the race (Larsen et al., 2004). The section ‘In review: Theories of emotion’ summarises key elements of the theories we have discussed. In short, emotion is probably both in the heart and in the head (including the face). The most basic emotions probably occur directly within the brain, whereas the many shades of emotions probably arise from attributions, categorisation and other cognitive interpretations of physiological responses and environmental events (Barrett et al., 2007). No theory has completely resolved the issue of which component of emotion, if any, is primary. However, the theories we have discussed have helped psychologists better understand how these components interact to produce emotional experience. Cognitive appraisal theories, in particular, have been especially useful in studying and treating stress-related emotional problems (see Chapter 12, ‘Health, stress and coping’, and Chapter 14, ‘Psychological disorders and treatment’). 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 523 26/07/17 11:23 AM 524 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion IN REVIEW Theories of emotion THEORY SOURCE OF EMOTIONS EXAMPLE Emotions are created by awareness of specific patterns of peripheral (autonomic) responses. Anger is associated with increased blood flow in the hands and feet; fear is associated with decreased blood flow in these areas. Cannon–Bard The brain generates direct experiences of emotion. Stimulation of certain brain areas can create pleasant or unpleasant emotions. Cognitive (Schachter–Singer; Lazarus) Cognitive interpretation of events and of physiological reactions to them shapes emotional experiences. Autonomic arousal can be experienced as anxiety or excitement, depending on how it is labelled. A single event can lead to different emotions, depending on whether it is perceived as threatening or challenging. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly James–Lange Check your understanding 1 Research showing that there are pleasure centres in the brain has been cited in support of the theory of emotions. 2 The use of polygraphs in lie detection is based on the theories of emotions. 3 The process of attribution is most important to theory of emotions. 10.7 COMMUNICATING EMOTION So far, we have described emotion from the inside, as people experience their own emotions. Let’s now consider how people communicate emotions to one another. One way they do this is through words. Some people describe their feelings relatively simply, mainly in terms of pleasantness or unpleasantness. Others include information about the intensity of their emotions (Barrett, 1995; Barrett et al., 2001). In general, women are more likely than men to talk about their emotions and the complexity of their feelings (Barrett et al., 2000; Kring & Gordon, 1998). Humans also communicate emotion through the movement and posture of their bodies (de Gelder et al., 2004; Hadjikhani & de Gelder, 2003), through their tone of voice (Simon-Thomas et al., 2009), and especially through their facial movements and expressions. Imagine a woman watching television.You can see her face but not what she sees on the screen. She might be engaged in complex thought, perhaps comparing her investments with those of the experts on a business channel. Or she might be thinking of nothing at all as she loses herself in a rerun of Friends. In other words, you won’t be able to tell much about what the woman is thinking. But if the TV program creates an emotional experience, you will be able to make a reasonably accurate guess about what she is feeling simply by looking at the expression on her face.The human face can create thousands of different expressions, and people – especially females – are good at detecting them (McClure, 2000; Zajonc, 1998). Observers can notice even tiny facial movements – a twitch of the mouth or eyebrow can carry a lot of information (Ambadar, Schooler & Cohn, 2005; Ekman, 2009). Are emotional facial expressions innate, or are they learned? And how are they used in communicating emotion? Innate expressions of emotion Charles Darwin (1872) observed that some facial expressions seem to be universal. He proposed that these expressions are genetically determined, passed on biologically from one generation to the next. The facial expressions seen today, said Darwin, are those that have been most effective at telling 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 524 26/07/17 11:23 AM 525 10.7 Communicating emotion What are they feeling? Snapshot People’s emotions are usually ‘written on their faces’. Jot down TRY THIS the emotions you think these people are feeling, and then look at the footnote at the bottom of this page to see how well you ‘read’ their emotions. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly others something about how a person is feeling. If someone is scowling with teeth clenched, for example, you will probably assume that he or she is angry, and you will be unlikely to choose that particular moment to ask for a loan (Marsh, Ambady & Kleck, 2005). Infants provide one source of evidence that some facial expressions are innate. Newborns do not need to be taught to grimace in pain or to smile in pleasure or to blink when startled (Balaban, 1995). Even blind infants, who cannot imitate adults’ expressions, show the same emotional expressions as sighted infants (Goodenough, 1932). A second line of evidence for innate facial expressions comes from studies showing that for the most basic emotions, people in all cultures show similar facial responses to similar emotional stimuli (Hejmadi, Davidson & Rozin, 2000; Matsumoto & Willingham, 2006; Zajonc, 1998). Participants in these studies look at photographs of people’s faces and then try to name the emotion each person is feeling (see the Snapshot ‘What are they feeling?’).Though there may be some subtle differences from culture to culture (Marsh, Elfenbein & Ambady, 2003), the overall pattern of facial movements we call a smile, for example, is universally related to positive emotions. Sadness is almost always accompanied by slackened muscle tone and a ‘long’ face. Likewise, in almost all cultures, people contort their faces in a similar way when shown something they find disgusting. A furrowed brow is frequently associated with frustration, and pride is often associated with a slight smile accompanied by a slight backwards tilt of the head (Ekman, 1994; Tracy & Robins, 2008). Anger is also linked with a facial expression recognised by almost all cultures. Expression of emotion People learn how to express certain emotions in particular ways, as specified by cultural rules. Suppose you say, ‘I just bought a new car’, and all your friends stick their tongues out at you. In Australia, this would mean that they are envious or resentful. However, in some regions of China, Traditional Ta Moko tattoos Snapshot The Māori in New Zealand apply the Ta Moko as a form of facial processing. It may also connect to a person’s whānau (family and community). Alamy Stock Photo/age fotostock Not all emotional expressions are innate or universal, however (Ekman, 1993). Some are learned through contact with a particular culture, and all of them, even innate expressions, are flexible enough to change as necessary in the social situations in which they occur (Fernández-Dols & Ruiz-Belda, 1995). For example, facial expressions become more intense and change more frequently while people are imagining social scenes as opposed to solitary scenes (Fridlund et al., 1990). Similarly, facial expressions in response to odours tend to be more intense when others are watching than when people are alone (Jancke & Kaufmann, 1994). Furthermore, although some basic emotional facial expressions are recognised by all cultures (Hejmadi, Davidson & Rozin, 2000), even these can be interpreted differently, depending on body language and environmental cues. For example, research participants interpreted a particular expression as disgust when it appeared on the face of a person who was holding a dirty nappy, but that same expression was seen as anger when it was digitally superimposed on a person in a fighting stance (Aviezer et al., 2008). There is even a certain degree of cultural variation when it comes to recognising some emotions (Russell, 1995). In one study, for example, Japanese and North American people agreed about which facial expressions signalled happiness, surprise and sadness, but they frequently disagreed about which faces showed anger, disgust and fear (Matsumoto & Ekman, 1989). Members of preliterate cultures, such as the Fore of New Guinea, agree even less with people in Western cultures on the labelling of facial expressions (Russell, 1994). In addition, there are variations in how people in different cultures interpret emotions expressed by tone of voice (Mesquita & Frijda, 1992). For instance, Taiwanese participants were best at recognising a sad tone of voice, whereas Dutch participants were best at recognising happy tones (Van Bezooijen, Otto & Heenan, 1983). Shutterstock.com/Ilike Social and cultural influences on emotional expression Did you identify frustration, anger, stress, annoyance, hurt, pain, sadness, disappointment? 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 525 26/07/17 11:23 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion The universal smile Snapshot such a display expresses surprise. An integral part of Māori society in New Zealand is the Ta Learning about emotions Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Tom Cockrem/Lonely Planet Images/Getty Image The idea that some emotional expressions are innate is supported by the fact that the facial movement pattern we call a smile is related to happiness, pleasure and other positive emotions in cultures throughout the world. Moko (see the Snapshot ‘Traditional Ta Moko tattoos’), a traditional tattoo worn by both males and females as a way of communicating information. Males wear it on the face and buttocks, while females wear it on the chin and the lips. The Ta Moko impacts on identity, gender and facial processing. Even smiles can vary as people learn to use them to communicate certain feelings (see the Snapshot ‘The universal smile’). Paul Ekman and his colleagues categorised 17 types of smiles, including ‘false smiles’, which fake enjoyment, and ‘masking smiles’, which hide unhappiness. They called the smile that occurs with real happiness the Duchenne smile, after the French researcher who first noticed a difference between spontaneous, happy smiles and posed smiles. A genuine Duchenne smile includes contractions of the muscles around the eyes (creating a distinctive wrinkling of the skin in these areas), as well as of the muscles that raise the lips and cheeks. Most people are not able to contract the muscles around the eyes during a posed smile, so this feature can be used to distinguish ‘lying smiles’ from genuine ones (Frank, Ekman & Friesen, 1993). ly 526 The effects of learning are seen in a child’s growing range of emotional expressions. Although infants begin with an innate set of emotional responses, they soon learn to imitate facial expressions and use them for more and more emotions. In time, these expressions become more precise and personalised, so that a particular expression conveys a clear emotional message to anyone who knows that person well. Operant shaping (described in Chapter 5, ‘Learning’) probably helps keep emotional expressions within certain limits. If you could not see other people’s facial expressions or observe their responses to yours, you might show fewer, or less intense, facial signs of emotion. In fact, there is some evidence that among people blind from birth, those who are older tend to show less animated facial expressions than those who are younger (Izard, 1977; Matsumoto & Willingham, 2009). Craig Lovell/Photoshot Emotion culture 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 526 As children grow, they learn an emotion culture – rules that govern what emotions are appropriate in what circumstances and what emotional expressions are allowed. These rules can vary between genders and from culture to culture (LaFrance, Hecht & Paluck, 2003; Tsai, Levenson & McCoy, 2006). For example, Australian TV news cameras have shown that soldiers leaving for duty in a war zone tend to keep their emotions in check as they say goodbye to wives, girlfriends and parents. However, in Italy – where mother–son ties are particularly strong – many male soldiers wail with dismay and weep openly as they leave. Emotion cultures shape how people describe and categorise feelings, resulting in both similarities and differences across cultures (Russell, 1991). At least five of the seven basic emotions listed in an ancient Chinese book called the Li Chi – joy, anger, sadness, fear, love, liking and dislike – are considered primary emotions by most Western theorists. Yet even though English has more than 500 emotion-related words, some emotion words in other languages have no English equivalent. Similarly, other cultures have no equivalent for some English emotion words. Many cultures do not see anger and sadness as different, for example. The Ilongot tribe in the Philippines have only one word, liget, for both anger and grief (Russell, 1991). Tahitians have words for 46 different types of anger but no word for sadness and, apparently, no concept of it. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 10.7 Communicating emotion 527 Social referencing Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Facial expressions, tone of voice, body postures and gestures can do more than communicate emotion. They can also influence others’ behaviour, especially the behaviour of people who are not sure what to do. An inexperienced chess player, for instance, might reach out to move the queen, catch sight of a spectator’s grimace, and infer that another move would be better. The process of letting another person’s emotional state guide our own behaviour is called social referencing (Campos, 1980). The visual-cliff studies described in Chapter 4, ‘Sensation and perception’, have been used to create an uncertain situation for infants. To reach its mother, an infant in these experiments must cross the visual cliff. If the apparent drop-off is very small or very large, there is no question about what to do: a 1-year-old knows to crawl across in the first case and to stay put in the second case. However, if the apparent drop-off is just large enough (say, half a metre) to create uncertainty, the infant relies on its mother’s facial expression to decide what to do. In one study, mothers were asked to make either a fearful or a happy face. When the mothers made a fearful face, no infant crossed the glass floor. But when they posed a happy face, most infants crossed (Sorce et al., 1981). Here is yet another example of the adaptive value of sending and receiving emotional communications. IN REVIEW Communicating emotion EXPRESSION OF EMOTION Innate expressions of emotions Social and cultural influences on emotional expression THEORY KEY FINDINGS Darwin argues for universality of facial expression; that is, that emotional expressions are genetically determined and passed on biologically from one generation to the next. Infants show evidence of emotions in facial expressions. Cultural evidence also suggests that there are basic facial emotional expressions across different groups of people. It is argued that not all emotional expressions are innate or universal. Some are learned and some change depending on social situations and interactions. While some emotional expressions are the same across cultures, they can be interpreted differently. People learn about cultural rules of emotional expression. As we develop, we learn and observe others’ emotional expression and this shapes our own expression. We learn what our emotion culture is. Check your understanding 1 The emotions of sadness, anger and happiness have all been shown to have facial responses to emotional stimuli. . 2 The process of letting another person’s emotional state guide our own behaviour is referred to as to assist them in evaluating their response. 3 The visual-cliff studies provided evidence that babies use their 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 527 26/07/17 11:23 AM 528 CHAPTER REVIEW LINKAGES stress and coping’). The ‘Linkages’ diagram shows ties to two other subfields as well, and there are many more ties throughout the book. Looking for linkages among subfields will help you see how they all fit together and help you better appreciate the big picture that is psychology. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly As noted in Chapter 1, ‘Introducing psychology’, all of psychology’s subfields are related to one another. Our discussion of conflicting motives and stress illustrates just one way in which the topic of this chapter, motivation and emotion, is linked to the subfield of health psychology (which is discussed in Chapter 12, ‘Health, CHAPTER 10 Motivation and emotion LINKAGES How does your brain know when you are hungry? Can motivational conflicts cause stress? What role does arousal play in aggression? CHAPTER 3 Biological aspects of psychology CHAPTER 12 Health, stress and coping CHAPTER 15 Social cognition and influence ONLINE STUDY RESOURCES Express Express Visit http://login.cengagebrain.com and use the access code that comes with this book for 12 months access to the resources and study tools for this chapter. The CourseMateExpress website contains: ●● ●● ●● ●● revision quizzes concept maps graduate attribute information videos 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 528 ●● ●● ●● web links flashcards and more. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 529 Summary SUMMARY Motivation refers to factors that influence the initiation, direction, intensity and persistence of behaviour. Emotion and motivation are often linked: motivation can influence emotion, and people are often motivated to seek certain emotions. CONCEPTS AND THEORIES OF MOTIVATION ●● ●● ●● ●● ●● evolutionary accounts of helping, aggression, mate selection and other aspects of social behaviour. Drive reduction theory is based on homeostasis, a tendency to maintain equilibrium in a physical or behavioural process. Primary drives are unlearned; secondary drives are learned. According to arousal theory, people are motivated to behave in ways that maintain a level of physiological arousal that is optimal for their functioning. Incentive theory highlights behaviours that are motivated by attaining desired stimuli (positive incentives) and avoiding undesirable ones (negative incentives). Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ●● Focusing on a motive often reveals a single theme within apparently diverse behaviours. Motivation is said to be an intervening variable, a way of linking various stimuli to the behaviours that follow them. The many sources of motivation fall into four categories: biological factors, emotional factors, cognitive factors and social factors. An early argument held that motivation follows from instinctive behaviours, which are automatic, involuntary and unlearned action patterns consistently ‘released’ by particular stimuli. Modern versions of the instinct doctrine are seen in ly ●● HUNGER AND EATING ●● ●● ●● Eating is controlled by a complex mixture of learning, culture and biology. The desire to eat (hunger) and the satisfaction (satiation) of that desire (satiety) that leads us to stop eating depends primarily on signals from bloodborne substances such as cholecystokinin (CCK), glucose, insulin and leptin. Activity in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus results in satiety, whereas activity in the lateral hypothalamus results in hunger. These brain regions act together to maintain ●● ●● a set point of body weight, but control of eating is more complex than that. Eating may also be influenced by the flavour of food and by appetite for the pleasure of food. Obesity has been linked to overconsumption of certain kinds of foods, to low energy metabolism, and to genetic factors. People with anorexia nervosa starve themselves. Those with bulimia engage in binge eating, followed by purging through self-induced vomiting or laxatives. SEXUAL BEHAVIOUR ●● ●● Sexual motivation and behaviour result from a rich interplay of biology and culture. Sexual stimulation generally produces sexual arousal, which appears in a stereotyped sexual response cycle of physiological arousal during and after sexual activity. Sex hormones, which include androgens, oestrogens and progestational hormones, occur in different relative amounts in both sexes. ●● ●● Gender-role learning and educational experiences are examples of cultural factors that can bring about variations in sexual attitudes and behaviours. Sexual orientation – heterosexuality, homosexuality or bisexuality – is increasingly viewed as a sociocultural variable that affects many other aspects of behaviour and mental processes. Though undoubtedly shaped by a lifetime of learning, sexual orientation appears to have strong biological roots. ACHIEVEMENT MOTIVATION ●● ●● ●● People gain esteem from achievement in many areas, including the workplace. The motive to succeed has been called mastery, effectance and need for achievement. Individuals with high achievement motivation strive for excellence, persist despite failures, and set challenging but realistic goals. Goals influence motivation, especially the amount of effort, persistence, attention and planning we devote to a task. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 529 ●● ●● Workers are most satisfied when they are working towards their own goals and are getting concrete feedback. Jobs that offer clear and specific goals, a variety of tasks, individual responsibility and other intrinsic rewards are the most motivating. People tend to have a characteristic level of happiness, or wellbeing, which is not necessarily related to the attainment of money, status or other material goals. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 530 ●● Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion actualisation. Needs at the lowest levels, according to Maslow, must be at least partly satisfied before people can be motivated by higher-level goals. Human behaviour reflects many motives, some of which may be in conflict. Abraham Maslow proposed a hierarchy of five classes of human motives or needs, from meeting basic biological requirements to attaining a state of self- THE NATURE OF EMOTION ●● various aspects of emotion. The expression of emotion through involuntary facial movement is controlled by the extrapyramidal motor system. Voluntary facial movements are controlled by the pyramidal motor system. The brain’s right and left hemispheres play somewhat different roles in emotion. Emotions are temporary experiences with positive or negative qualities that are felt with some intensity as happening to the self, are generated in part by a cognitive appraisal of a situation, and are accompanied by both learned and innate physical responses. Several brain mechanisms are involved in emotion. The amygdala, in the limbic system, is deeply involved in ly ●● ●● ●● Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On THEORIES OF EMOTION William James’ theory of emotion holds that peripheral physiological responses are the primary source of emotion, and that awareness of these responses constitutes emotional experience. James’ theory is supported by evidence that, at least for several basic emotions, physiological responses are distinguishable enough for emotions to be generated in this way. Distinct facial expressions are linked to particular patterns of physiological change. Walter Cannon’s theory of emotion proposes that emotional experience occurs independently of peripheral physiological responses, and that there is a direct experience of emotion ●● based on activity of the central nervous system. Updated versions of this theory suggest that various parts of the central nervous system may be involved in different emotions and different aspects of emotional experience. And specific parts of the brain appear to be responsible for the feelings of pleasure or pain in emotion. Stanley Schachter’s modification of James’ theory proposes that physiological responses are primary sources of emotion, but that the cognitive labelling of those responses – a process that depends partly on attribution – strongly influences the emotions we experience. COMMUNICATING EMOTION ●● ●● Humans communicate emotions mainly through facial movement and expressions, but also through voice tones and bodily movements. Charles Darwin suggested that certain facial expressions of emotion are innate and universal, and that these expressions evolved because they effectively communicate one creature’s emotional condition to other creatures. Some facial ●● expressions of basic emotions, such as happiness, do appear to be innate. Many emotional expressions are learned, and even innate expressions are modified by learning and social contexts. As children grow, they learn an emotion culture – the rules of emotional expression appropriate to their culture. TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE Select the best answer for each of the following questions, then check your responses against the ‘Answer key’ at the end of the book. 1 Although most researchers do not believe in instinct theories of motivation, psychologists who advocate theory argue that many aspects of human behaviour are motivated by efforts to pass on our genes to the next generation. a drive reduction b evolutionary c arousal d incentive 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 530 2 Steve is cold, so he turns on the heating. As soon as it starts to get too warm, the thermostat shuts off the heater. This process is similar to the biological concept of . a homeostasis b secondary drive c incentive d arousal 26/07/17 11:23 AM 531 Talking points a drive reduction b incentive c evolutionary d arousal 4 Ahmed is desperate to lose weight. To keep from eating, he buys an electrical device that allows him to stimulate various areas of his brain. Which areas should he stimulate if he wants his brain to help him reduce food intake? a Ventromedial nucleus and paraventricular nucleus b Lateral hypothalamus and ventromedial nucleus Lateral hypothalamus and paraventricular nucleus Eve wants her son, Eddie, to develop high achievement motivation and to be successful in life. According to research on the need for achievement, Eve should do all of the following except . a encourage Eddie to try difficult tasks b encourage Eddie to avoid failure at all costs c give praise and rewards for success d read achievement-oriented stories to him 8 Which of the following is not a characteristic associated with . emotions? They a tend to last a relatively short time b can be triggered by thoughts c are always intense d can motivate behaviour Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On c 7 ly 3 Monica wants her daughter to get high grades, so she offers her $10 for each A that she earns and $5 for each B. Monica appears to believe in the theory of motivation. d Thalamus and pineal gland 5 Tonia is on a diet – again! She is most likely to eat less food . if she a eats only with friends, never alone b eats only one or two kinds of food at each meal c changes her food culture d focuses on the flavour of what she eats 6 Dr Stefan is working in the emergency room when a very dehydrated young woman comes in. She is of normal weight, but a medical exam reveals nutritional imbalances and intestinal damage. The woman is most likely suffering from . a anorexia nervosa 9 After she finished a vigorous workout, Lee saw Ryan walk into the gym and instantly fell in love. This is an example , which is consistent with theory of of emotion. a social referencing; James’ b social referencing; Schachter’s c excitation transfer; James’ d excitation transfer; Schachter’s 10 Suppose that some friendly space aliens landed in your backyard. They tell you they want to learn how to communicate their emotions so that humans will understand them. What should you focus on teaching them? a Body postures b bulimia b Facial movements c c binge eating disorder d ventromedial disorder Hand gestures d Voice inflections TALKING POINTS Here are a few talking points to help you summarise this chapter for family and friends without giving a lecture. 1 You can’t actually see motives such as love or hatred or greed, but you can use them to help understand the reasons for people’s behaviour. 2 Motivation and emotion are linked. Hunger can make you irritable, and being in love can motivate you to do almost anything for a loved one. 3 The arousal theory of motivation has been used to help explain why some people are introverts and others are extroverts. 4 Crash diets are not the best way to lose weight and keep it off. The key is to increase fat-burning through regular exercise while also reducing food intake. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 531 5 Sexual orientation is shaped by biological factors as well as social influences. 6 Achieving success in school, at work and elsewhere is more likely if we have a sense of control and a set of clear and challenging but not impossible goals. 7 The emotions we experience in a particular situation depend partly on how we think about that situation; adjusting our view of an event can change our emotional reaction to it. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 532 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion FURTHER READING Now that you have finished reading this chapter, how about exploring some of the topics and information that you found most interesting. Here are some places to start. RECOMMENDED BOOKS Antonio R. Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (Penguin, 2005) – an exploration of the biology of emotion and reason and how they’re intertwined in the brain. Gelsey Kirkland, Dancing on My Grave (Doubleday, 1987) – eating disorders. Dalai Lama and Paul Ekman, Emotional Awareness: Overcoming the Obstacles to Psychological Balance and Compassion (Times Books, 2008) – conversations between Paul Ekman and the Dalai Lama about the experiences and meanings of emotions and human interaction. Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (Viking Press, 2002) – wide-ranging description of evolutionary and genetic explanations of motivation. CHAPTER REFERENCES Australian National Preventive Health Agency (2014) Obesity: Prevalence trends in Australia. Report prepared by The Boden Institute of Obesity, Nutrition, Exercise & Eating Disorders and the Menzies Centre for Health Policy, University of Sydney for the Australian National Preventive Health Agency. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Aaron, D. J., Chang, Y.-F., Markovic, N., & LaPorte, R. E. (2003). Estimating the lesbian population: A capture-recapture approach. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 207–209. Aldert Vrij, Detecting Lies and Deceit: The Psychology of Lying and Implications for Professional Practice (Wiley, 2000) – a summary of various approaches. ly David Goldstein (ed.), The Management of Eating Disorders and Obesity (Humana Press, 2005) – a summary of research on and treatment of eating disorders. David Lykken, Happiness: The Nature and Nurture of Joy and Contentment (Griffin, 2000) – a summary of research on the ‘happiness set point’ and other aspects of wellbeing. Abrantes-Pais, F. de N., Friedman, J. K., Lovallo, W. R., & Ross, E. D. (2007). Psychological or physiological: Why are tetraplegic patients content? Neurology, 69, 261–267. Adachi-Mejia, A. M., Longacre, M. R., Gibson, J. J., Beach, M. L., et al. (2007). Children with a TV in their bedroom at higher risk for overweight. International Journal of Obesity, 31, 644–651. Averill, J. S. (1980). On the paucity of positive emotions. In K. R. Blankstein, P. Pliner, & J. Polivey (Eds.), Advances in the study of communication and affect: Vol. 6. Assessment and modification of emotional behavior. New York: Plenum. Aviezer, H., Hassin, R. R., Ryan, J., Grady, C., et al. (2008). Angry, disgusted, or afraid? Studies on the malleability of emotion perception. Psychological Science, 19, 724–732. Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1998). The human amygdala in social judgment. Nature, 393, 470–474. Bailey, J. M., & Benishay, D. S. (1993). Familial aggregation of female sexual orientation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 272–277. Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (1994). Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature, 372, 669–672. Bailey, J. M., Bobrow, D., Wolfe, M., & Mikach, S. (1995). Sexual orientation of adult sons of gay fathers. Developmental Psychology, 31, 124–129. Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4, 142–175. Allen, J. B., Kenrick, D. T., Linder, D. E., & McCall, M. A. (1989). Arousal and attraction: A response-facilitation alternative to misattribution and negative-reinforcement models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 261–270. Ambadar, Z., Schooler, J. W., & Cohn, J. F. (2005). Deciphering the enigmatic face. Psychological Science, 16, 403–410. American Psychiatric Association. (1999). Position statement on psychiatric treatment and sexual orientation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1131. American Psychological Association. (2002). Answers to your questions about sexual orientation and homosexuality. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pubinfo/answers .html#whatis Anderson, A. K., & Phelps, E. A. (2000). Expression without recognition: Contributions of the human amygdala to emotional communication. Psychological Science, 11, 106–111. Anderson, A. K., & Phelps, E. A. (2001). Lesions of the human amygdala impair enhanced perception of emotionally salient events. Nature, 411, 305–309. Anderson, S. E., Cohen, P., Naumova, E. N., Jacques, P. F., & Must, A. (2007). Adolescent obesity and risk for subsequent major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder: Prospective evidence. Psychosomatic Medicine 69, 740–747. Anderssen, N., Amlie, C., & Ytteroy, E. A. (2002). Outcomes for children with lesbian or gay parents: A review of studies from 1978 to 2000. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43, 335–351. APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Arsenault, B. J., Rana, J. S., Lemieux, I., Despres, J.-P., et al. (2010). Physical inactivity, abdominal obesity and risk of coronary heart disease in apparently healthy men and women. International Journal of Obesity, 34, 340–347. Atlantis, E., & Baker, M. (2008). Obesity effects on depression: Systematic review of epidemiological studies. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 881–891. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 532 Bailey, J. M., Dunne, M. P., & Martin, N. G. (2000). Genetic and environmental influences on sexual orientation and its correlates in an Australian twin sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 524–536. Bailey, J. M., & Pillard, R. C. (1991). A genetic study of male sexual orientation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1086–1096. Balaban, M. T. (1995). Affective influences on startle in five-month-old infants: Reactions to facial expressions of emotion. Child Development, 66(1), 28–36. Bancroft, J. (1994). Homosexual orientation: The search for a biological basis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 437–440. Barber, N. (1995). The evolutionary psychology of physical attractiveness: Sexual selection and human morphology. Ethology and Sociobiology, 16, 395–424. Barrett, L. F. (1995). Valence focus and arousal focus: Individual differences in the structure of affective experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 153–166. Barrett, L. F., Gross, J., Christensen, T. C., & Benvenuto, M. (2001). Knowing what you’re feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion, 15, 713–724. Barrett, L. F., Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L., & Schwartz, G. E. (2000). Sex differences in emotional awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1027–1035. Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2007). The experience of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 373–403. Barrett, L. F., & Wager, T. D. (2006). The structure of emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 79–83. Barron, K. E., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2001). Achievement goals and optimal motivation: Testing multiple goal models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 706–722. Barr Taylor, C., Bryson, S., Celio Doyle, A. A., Luce, K. H., et al. (2006a). The adverse effect of negative comments about weight and shape from family and siblings on women at high risk for eating disorders. Pediatrics, 118, 731–738. Bartels, M. (2015). Genetics of wellbeing and its components satisfaction with life, happiness, and quality of life: A review and meta-analysis of heritability studies. Behavior genetics, 45(2), 137-156. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 533 Further reading Bastian, B., Jetten, J., & Fasoli, F. (2011). Cleansing the soul by hurting the flesh: The guilt-reducing effect of pain. Psychological Science, 22(3), 334–335. doi:10.1177/0956797610397058. Basson, R. (2001). Human sex-response cycles. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 27, 33–43. Batterham, R. L., Cohen, M. A., Ellis, S. M., Le Roux, C. W., et al. (2003). Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY3-36. New England Journal of Medicine, 349, 941–948. Bouret, S. G., Draper, S. J., & Simerly, R. B. (2004). Trophic action of leptin on hypothalamic neurons that regulate feeding. Science, 304, 108–110. Bourne, V. J. (2010). How are emotions lateralised in the brain? Contrasting existing hypotheses using the Chimeric Faces Test. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 903–911. doi:10.1080/02699930903007714 Bray, G. A., & Tartaglia, L. A. (2000). Medicinal strategies in the treatment of obesity. Nature, 404, 672–677. Batterham, R. L., Cowley, M. A., Small, C. J., Herzog, H., et al. (2002). Gut hormone PYY3-36 physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature, 418, 650–654. Breedlove, S. M. (1994). Sexual differentiation of the human nervous system. Annual Review of Psychology, 45, 389–418. Baumeister, H., & Härter, M. (2007). Mental disorders in patients with obesity in comparison with healthy probands. International Journal of Obesity, 31, 1155–1164. Brehm, J. W., Miron, A. M., & Miller, K. (2009). Affect as a motivational state. Cognition and Emotion, 23, 1069–1089. Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 347–374. Brewerton, T. D., & Costin, C. (2011a). Long-term outcome of residential treatment for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 19(2), 132–144. doi:10.1080/10640266.2011.551632 Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. Brewerton, T. D., & Costin, C. (2011b). Treatment results of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in a residential treatment program. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 19(2), 117–131. doi:10.1080/10640266.2011.551629 BeLue, R., Francis, L. A., & Colaco, B. (2009). Mental health problems and overweight in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: Effects of race and ethnicity. Pediatrics, 123, 697–702. Brüning, J. C., Gautam, D., Burks, D. J., Gillette, J., et al. (2000). Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science, 289, 2122–2125. Bullough, V. L. (1995, August). Sex matters. Scientific American, pp. 105–106. Bem, D. J. (2000). Exotic becomes erotic: Interpreting the biological correlates of sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29, 531–548. Burdakov, D., Karnani, M. M., & Gonzalez, A. (2013). Lateral hypothalamus as a sensor- regulator in respiratory and metabolic control. Physiology & Behavior, 121, 117–124. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On ly Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275, 1293–1295. Ben-Shakhar, G., Bar-Hillel, M., & Kremnitzer, M. (2002). Trial by polygraph: Reconsidering the use of the guilty knowledge technique in court. Law and Human Behavior, 26, 527–541. Ben-Shakhar, G., & Furedy, J. J. (1990). Theories and applications in the detection of deception: A psychophysiological and international perspective. New York: Springer-Verlag. Benson, E. (2003). Sex: The science of sexual arousal. Monitor on Psychology, 34, 50. Bergman, T. J., & Kitchen, D. M. (2009). Comparing responses to novel objects in wild baboons (Papio ursinus) and geladas (Theropithecus gelada). Animal Cognition, 12, 63–73. Bermond, B., Fasotti, L., Nieuwenhuyse, B., & Schuerman, J. (1991). Spinal cord lesions, peripheral feedback and intensities of emotional feelings. Cognition and Emotion, 5, 201–220. Bernard, L. L. (1924). Instinct. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Bernat, J. A., Calhoun, K. S., Adams, H. E., & Zeichner, A. (2001). Homophobia and physical aggression toward homosexual and heterosexual individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 179–187. Berndt, R. M., & Berndt C. H. (1996). The world of the first Australians. Aboriginal traditional life: Past and present. London: Angus & Robertson. (Original published 1964). Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2008). Affective neuroscience of pleasure: Reward in humans and animals. Psychopharmacology, 199, 457–480. Bickham, D. S., Blood, E. A., Walls, C. E., Shrier, L. A., & Rich, M. (2013). Characteristics of screen media use associated with higher BMI in young adolescents. Pediatrics, 131(5), 935–941. Birch, L. L., McPhee, L., Sullivan, S., & Johnson, S. (1989). Conditioned meal initiation in young children. Appetite, 13, 105–113. Black Becker, C., Bull, S., Smith, L. M., & Ciao, A. C. (2008). Effects of being a peerleader in an eating disorder prevention program: Can we further reduce eating disorder risk factors? Eating Disorders, 16, 444–459. Blanchard, R. (2001). Fraternal birth order and the maternal immune hypothesis of male homosexuality. Hormones and Behavior, 40, 105–114. Blanchard, R., & Lippa, R. A. (2007). Birth order, sibling sex ratio, handedness, and sexual orientation of male and female participants in a BBC Internet research project. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 163–176. Blundell, J. E., & Cooling, J. (2000). Routes to obesity: Phenotypes, food choices and activity. British Journal of Nutrition, 83, S33–S38. Bogaert, A. F., Blanchard, R., & Crosthwait, L. (2007). Interaction of birth order, handedness, and sexual orientation in the Kinsey interview data. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121, 845–853. Boon, H. J. (2008) Family, motivational and behavioural links to Indigenous Australian adolescents’ achievement. Proceedings of AARE 2007 International Educational Research Conference: Research Impacts: Proving or Improving?, 25–29 November, 2007, Fremantle, WA. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 533 Burke, R. J., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Work motivations, work outcomes, and health: Passion versus addiction. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(Suppl. 2), 257–263. Burleson, M. H., Gregory, W. L., & Trevarthen, W. R. (1995). Heterosexual activity: Relationship with ovarian function. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 20, 405–421. Burns, A. B., Brown, J. S., Sachs-Ericsson, N., Plant, E. A., et al. (2008). Upward spirals of positive emotion and coping: Replication, extension, and initial exploration of neurochemical substrates. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 360–370. Buss, D. M. (2004a). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Buss, D. M. (2004b). The evolution of desire: Strategies of human mating. New York: Basic Books. Buss, D. M. (2009). The great struggles of life: Darwin and the emergence of evolutionary psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 140–148. Buss, D. M., Abbott, M., Angleitner, A., Biaggio, A., et al. (1990). International preferences in selecting mates. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 21, 5–47. Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232. Butler, R. (1998). Information seeking and achievement motivation in middle childhood and adolescence: The role of conceptions of ability. Developmental Psychology, 35, 146–163. Cobanac, M., & Morrissette, J. (1992). Acute, but not chronic, exercise lowers the body weight set-point in male rats. Physiology and Behavior, 52, 1173–1177. Cacioppo, J. T., Gardner, W. L., & Berntson, G. G. (1999). The affect system has parallel and integrative processing components: Form follows function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 839–855. Campos, J. J. (1980). Human emotions: Their new importance and their role in social referencing. Research and Clinical Center for Child Development: 1980–81 Annual Report, 1–7. Cannon, W. B. (1927). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage: An account of recent researches into the function of emotional excitement. New York: Appleton. Cannon, W. B., & Washburn, A. L. (1912). An explanation of hunger. American Journal of Physiology, 29, 444–454. Capasso, R., & Izzo, A. A. (2008). Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake: General aspects and focus on anandamide and oleoylethanolamide. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 20(Suppl. 1), 39–46. Carels, R. A., Young, K. M., Coit, C., Clayton, A. M., et al. (2008). Can following the caloric restriction recommendations from the dietary guidelines for Americans help individuals lose weight? Eating Behaviors, 9, 328–335. Carver, C. S., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 183–204. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 534 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Overweight and obesity. http:// www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/facts.html. Updated April 24, 2014. Centre of Excellence in Eating Disorders. (2011). Facts and findings. Retrieved from http://www.ceed.org.au/facts-and-findings/w1/i1001246/for consumers and carers Chaput, J.-P., & Tremblay, A. (2009). The glucostatic theory of appetite control and the risk of obesity and diabetes. International Journal of Obesity, 33, 46–53. Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14(2), F1–F10. doi:10.1111/j.1467–7687.2010.01035.x Davidson, J. M., Camargo, C. A., & Smith, E. R. (1979). Effects of androgen on sexual behavior in hypogonadal men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinological Metabolism, 48, 955–958. Davidson, R. J. (2000). Affective style, psychopathology, and resilience: Brain mechanisms and plasticity. American Psychologist, 55, 1196–1214. Davidson, R. J., Shackman, A. J., & Maxwell, J. S. (2004). Asymmetries in face and brain related to emotion. Trends in Cognitive Science, 8, 389–391. Davis, C., & Kapstein, S. (2006). Anorexia nervosa with excessive exercise: A phenotype with close links to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research, 142, 209–217. Davis, J. A., & Smith, T. W. (1990). General social surveys, 1972–1990: Cumulative codebook. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center. Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., & Blanchard, R. (2007). Gender and sexual orientation differences in sexual response to sexual activities versus gender of actors in sexual films. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 1108–1121. Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627–668. Christie, I. C., & Friedman, B. H. (2004). Autonomic specificity of discrete emotion and dimensions of affective space: A multivariate approach. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 51, 143–153. de Gelder, B., Snyder, J., Greve, D., Gerard, G., & Hadjikhani, N. (2004). Fear fosters flight: A mechanism for fear contagion when perceiving emotion expressed by a whole body. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101, 16 701–16 706. Clendenen, V. I., Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1995). Social facilitation of eating among friends and strangers. Appetite, 23, 1–13. Deich, J. D., Tankoos, J., & Balsam, P. D. (1995). Systematic changes in gaping during the ontogeny of pecking in ring doves (Streptopelia risoria). Developmental Psychobiology, 28, 147–163. Derryberry, D., & Tucker, D. M. (1992). Neural mechanisms of emotion. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 329–338. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Cobos, P., Sánchez, M., Pérez, N., & Vila, J. (2004). Effects of spinal cord injuries on the subjective component of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 18, 281–287. ly Chivers, M. L., Rieger, G., Latty, E., & Bailey, J. M. (2004). A sex difference in the specificity of sexual arousal. Psychological Science, 15, 736–744. Coelho, J. S., Jansen, A., Roefs, A., & Nederkoorn, C. (2009). Eating behavior in response to food-cue exposure: Examining the cue-reactivity and counteractivecontrol models. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23, 131–139. Committee to Review the Scientific Evidence on the Polygraph. (2003). The polygraph and lie detection. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., Ziegler, A., & Valentine, B. A. (2011). Women, men, and the bedroom: Methodological and conceptual insights that narrow, reframe, and eliminate gender differences in sexuality. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 20(5), 296–300. doi:10.1177/0963721411418467 Cooke, L. J., Chambers, L. C., Añez, E. V., Croker, H. A., Boniface, D., Yeomans, M. R., & Wardle, J. (2011). Eating for Pleasure or Profit: The Effect of Incentives on Children’s Enjoyment of Vegetables. Psychological Science, 22(2), 190–196. doi:10.1177/0956797610394662. Cooley, E., Toraya, T., Wanga, M. C., & Valdeza, N. N. (2008). Maternal effects on daughters’ eating pathology and body image. Eating Behaviors, 9, 52–61. Corker, K. S., & Donnellan, M.B. (2012). Setting lower limits high: The role of boundary goals in achievement motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 138–149. Cornelius, R. R. (1996). The science of emotion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Cota, D., Marsicano, G., Lutz, B., Vicennati, V., et al. (2003). Endogenous cannabinoid system as a modulator of food intake. International Journal of Obesity, 27, 289–301. Cota, D., Proulx, K., Smith, K. A. B., Kozma, S. C., et al. (2006). Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science, 312, 927–930. Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3, 655–666. Crépin, D., Benomar, Y., Riffault, L., Amine, H., Gertler, A., & Taouis, M. (2014). The overexpression of miR-200a in the hypothalamus of ob/ob mice is linked to leptin and insulin signaling impairment. Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology, 384(1–2), 1–11. Critchley, E. M. (1991). Speech and the right hemisphere. Behavioural Neurology, 4, 143–151. Crowther, J. H., Sanftner, J., Bonifazi, D. Z., & Shepherd, K. L. (2001). The role of daily hassles in binge eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 449–454. Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701–712. Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam. Damasio, A. R., Grabowski, T. J., Bechara, A., Damasio, H., et al. (2000). Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self-generated emotions. Nature Neuroscience, 3, 1049–1056. Dannenberg, A. L., Burton, D. C., & Jackson, R. J. (2004). Economic and environmental costs of obesity: the impact on airlines. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(3), 264. Darwin, C. E. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: Murray. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 534 DeVoe, S. E., & Iyengar, S. S. (2010). Medium of exchange matters: What’s fair for goods is unfair for money. Psychological Science, 21(2), 159–162. doi:10.1177/ 0956797609357749 Dhurandhar, N. V., Israel, B. A., Kolesar, J. M., Mayhew, G. F., et al. (2000). Increased adiposity in animals due to a human virus. International Journal of Obesity, 24, 989–996. Di Leone, R. J. (2009). The influence of leptin on the dopamine system and implications for ingestive behavior. International Journal of Obesity, 33, S25–S29. Di Marzo, V., Goparaju, S. K., Wang, L., Liu, J., et al. (2001). Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature, 410, 822–825. Diamond, L. M. (2008). Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 44, 5–14. Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43. Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., & Arora, R. (2010). Wealth and happiness across the world: Material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 52–61. Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Towards an economy of wellbeing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31. DiPatrizio, N. V., Astarita, G., Schwartz, G., Xiaosong, L., & Piomelli, D. (2011). Endocannabinoid signal in the gut controls dietary fat intake. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(31), 12904–12908. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104675108 Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., & Ive, S. (2006). Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-yearold girls. Developmental Psychology, 42, 283–292. Dodd, M. L., Klos, K. J., Bower, J. H., Geda, Y. E., et al. (2005). Pathological gambling caused by drugs used to treat Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology, 62, 1377–1381. Dohnt, H., & Tiggemann, M. (2006). The contribution of peer and media influences to the development of body satisfaction and self-esteem in young girls: A prospective study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 929–936. Dombrowski, S. U., Knittle, K., Avenell, A., Araujo-Soares, V., & Sniehotta, F. F. (2014). Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2646 Dutton, D. G., & Aron, A. P. (1974). Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 510–517. Dweck, C. S. (1998). The development of early self-conceptions: Their relevance for motivational processes. In J. Heckhausen & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Motivation and selfregulation across the life span. New York: Cambridge University Press. Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C. (2004). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: Implications for the partner preferences of women and 26/07/17 11:23 AM 535 Further reading Eating Disorders Victoria. (2015). Bulimia nervosa: fact sheet. Retrieved from https:// www.eatingdisorders.org.au/eating-disorder-fact-sheets Eaton, M. J., & Dembo, M. H. (1997). Differences in the motivational beliefs of Asian American and non-Asian students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 433–440. Eddy, K. T., Dorer, D. J., Franko, D. L., Tahilani, K., et al. (2008). Diagnostic crossover in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Implications for DSM-V. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 245–250. Eisenberger, R., Jones, J. R., Stinglhamber, F., Shanock, L., & Tenglund, A. (2005). Optimal flow experiences at work: For high need achievers alone? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 755–775. Ekman, P. (1993). Facial expression and emotion. American Psychologist, 48, 384–392. Ekman, P. (1994). Strong evidence for universals in facial expressions: A reply to Russell’s mistaken critique. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 268–287. Ekman, P. (2009). Lie catching and micro expressions. In C. W. Martin (Ed.), The philosophy of deception (pp. 118–138). New York: Oxford University Press. Frayling, T. M., Timpson, N. J., Weedon, M. N., Zeggini, E., et al. (2007). A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science, 316, 889–894. Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226. Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062. Fridlund, A., Sabini, J. P., Hedlund, L. E., Schaut, J. A., et al. (1990). Audience effects on solitary faces during imagery: Displaying to the people in your head. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 14, 113–137. Fujita, F., & Diener, E. (2005). Life satisfaction set point: Stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 158–164. Galef, B. G., & Wright, T. J. (1995). Groups of naive rats learn to select nutritionally adequate foods faster than do isolated rats. Animal Behaviour 49, 403–409. Galloway, A. T., Addessi, E., Fragaszy, D. M., & Visalberghi, E. (2005). Social facilitation of eating familiar food in tufted capuchins (Cebus appella): Does it involve behavioral coordination? International Journal of Primatology, 26, 181–189. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J., Ricard, M., & Alan, W. B. (2005). Buddhist and psychological perspectives on emotions and well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 59–63. Frank, M. G., Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1993). Behavioral markers and recognizability of the smile of enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 83–93. ly men. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (2nd ed., pp. 269–295). New York: Guilford Press. Ekman, P., Levenson, R. W., & Friesen, W. V. (1983). Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science, 221, 1208–1210. Elliot, A. J. (Ed.). (2008). Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation. New York: Psychology Press. Ellis, A. L., & Mitchell, R. W. (2000). Sexual orientation. In L. T. Szuchman & F. Muscarella (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on human sexuality (pp. 196–231). New York: Wiley. Epstein, L. H., Temple, J. L., Roemmich, J. N., & Bouton, M. E. (2009). Habituation as a determinant of human food intake. Psychological Review, 116, 384–407. Eysenck, H. J. (1990). Biological dimensions of personality. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 244–276). New York: Guilford. Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Shafran, R., Wilson, G. T., & Barlow, D. H. (2008). Eating disorders: A transdiagnostic protocol. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 578–614). New York: Guilford Press. Farley, F. (1986). The big T in personality. Psychology Today, 20, 44–52. Feinstein, J. S., Duff, M. C., & Tranel, D. (2010). Sustained experience of emotion after loss of memory in patients with amnesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 7674–7679. Fernández-Dols, J.-M., & Ruiz-Belda, M.-A. (1995). Are smiles a sign of happiness? Gold medal winners at the Olympic Games. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 1113–1119. Fernstrom, J. D., & Choi, S. (2007). The development of tolerance to drugs that suppress food intake. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 117, 105–122. Ferraro, R., Lillioja, S., Fontvieille, A. M., Rising, R., et al. (1992). Lower sedentary metabolic rate in women compared with men. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 90, 780–784. Fève, B., & Bastard, J. P. (2012). From the conceptual basis to the discovery of leptin. Biochimie, 94(10), 2065–2068. Fisher, C. D. (2000). Mood and emotion while working: Missing pieces of job satisfaction? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 185–202. Flegal, K. M., Kit, B. K., Orpana, H., & Graubard, B. I. (2013). Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 309(1), 71–82. Forbes, S., Bui, S., Robinson, B. R., Hochgeschwender, U., & Brennan, M. B. (2001). Integrated control of appetite and fat metabolism by the leptin-proopiommelanocortin pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98, 4233–4237. Fossati, P., Hevenor, S. J., Graham, S. J., Grady, C., et al. (2003). In search of the emotional self: An fMRI study using positive and negative emotional words. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1938–1945. Francis, A. M. (2008). Family and sexual orientation: The family-demographic correlates of homosexuality in men and women. Journal of Sex Research, 45, 371–377. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 535 Gamer, M., Rill, H.-G., Vossel, G., & Godert, H. W. (2006). Psychophysiological and vocal measures in the detection of guilty knowledge. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 60, 76–87. Gangestad, S. W., Garver-Apgar, C. E., Simpson, J. A., & Cousins, A. J. (2007). Changes in women’s mate preferences across the ovulatory cycle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 151–163. Gariepy, G., Nitka, D., & Schmitz, N. (2010). The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Obesity, 34, 407–419. Garvan Institute. (2012). Anorexia. Retrieved from http://www.garvan.org.au/research /our-work/anorexia?gclid=CIjU7oDR9qsCFSZNpgodCT00-Q Garver-Apgar, C. E., Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (2008). Hormonal correlates of women’s mid-cycle preference for the scent of symmetry. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 223–232. Geher, G., Camargo, M. A., & O’Rourke, S. D. (2008). Mating intelligence: An integrative model and future research directions. In G. Geher & G. Miller (Eds.), Mating intelligence: Sex, relationships, and the mind’s reproductive system (pp. 395–424). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Geier, A. B., Rozin, P., & Doros, G. (2006). Unit bias: A new heuristic that helps explain the effect of portion size on food intake. Psychological Science, 17, 521–525. Gilbert, D. T. (2006). Stumbling on happiness. New York: Knopf. Gilbert, D. T., Morewedge, C. K., Risen, J. L., & Wilson, T. D. (2004). Looking forward to looking backward: The misprediction of regret. Psychological Science, 15, 346–350. Gilbert-Diamond, D., Li, Z., Adachi-Mejia, A. M., McClure, A. C., & Sargent, J. D. (2014). Association of a television in the bedroom with increased adiposity gain in a nationally representative sample of children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(5), 427–434. Glasser, C. L., Robnett, B., & Feliciano, C. (2009). Internet daters’ body type preferences: Race–ethnic and gender differences. Sex Roles, 61(1–2), 14–33. Gong, Y., & Fan, J. (2006). A longitudinal examination of the role of goal orientation in cross-cultural adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 176–184. Goodenough, F. L. (1932). Expression of the emotions in a blind-deaf child. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27, 328–333. Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460–476. Granhag, P.-A. & Stromwall, L. (2004). The detection of deception in forensic contexts. New York: Cambridge University Press. Grant, H., & Dweck, C. S. (2003). Clarifying achievement goals and their impact. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 541–553. Greer, A. E., & Buss, D. M. (1994). Tactics for promoting sexual encounters. Journal of Sex Research, 31, 185–201. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 536 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Greeson, J. M. (2009). Mindfulness research update, 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14, 10–18. Houpt, T. R. (1994). Gastric pressure in pigs during eating and drinking. Physiology and Behavior, 56, 311–317. Greven, C. U., Harlaar, N., Kovas, Y., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Plomin, R. (2009). More than just IQ: School achievement is predicted by self-perceived abilities—but for genetic rather than environmental reasons. Psychological Science, 20, 753–762. Hrdy, S. B. (1997). Raising Darwin’s consciousness: Female sexuality and the prehominid origins of patriarchy. Human Nature, 8, 1–49. Gross, J. J. (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 214–219. Hadjikhani, N., & de Gelder, B. (2003). Seeing fearful body expressions activates the fusiform cortex and amygdala. Current Biology, 13, 2201–2205. Hall, C. S., Lindzey, G., & Campbell, J. P. (1998). Theories of personality (4th ed.). New York: Wiley. Hamad, G. G. (2004). The state of the art in bariatric surgery for weight loss in the morbidly obese patient. Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 31, 591–600. Hamann, S., Herman, R. A., Nolan, C. L., & Wallen, K. (2004). Men and women differ in amygdala response to sexual stimuli. Nature Neuroscience, 7, 411–416. Hrdy, S. B. (2003). The optimal number of fathers: Evolution, demography, and history in the shaping of female mate preferences. In S. J. Scher & F. Rauscher (Eds.), Evolutionary psychology: Alternative approaches (pp. 111–133). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer. Hu, S., Patatucci, A. M. L., Patterson, C., Li, L., et al. (1995). Linkage between sexual orientation and chromosome Xq28 in males but not females. Nature Genetics, 11, 248–256. Huang, L., & Li, C. (2000). Leptin: A multifunctional hormone. Cell Research, 10, 81–92. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.014 Hughes, R. N. (2007). Neotic preferences in laboratory rodents: Issues, assessment, and substrates. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 31, 441–464. Hull, C. L. (1943). Principles of behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. Hull, C. L. (1951). Essentials of behavior. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ly Grinspoon, S., Thomas, E., Pitts, S., Gross, E., et al. (2000). Prevalence and predictive factors for regional osteopenia in women with anorexia nervosa. Annals of Internal Medicine, 133, 790–794. Hyde, J. S., & Durik, A. M. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: Evolutionary or sociocultural forces? Comment on Baumeister (2000). Psychological Bulletin, 126, 375–379. Harmon-Jones, E., & Sigelman, J. (2001). State anger and prefrontal brain activity: Evidence that insult-related relative left prefrontal activation is associated with experienced anger and aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 797–804. Iacono, W. G., & Patrick, C. J. (2006). Polygraph (‘lie detector’) testing: Current status and emerging trends. In I. B. Weiner & A. K. Hess (Eds.), The handbook of forensic psychology (3rd ed., pp. 552–588). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Haslam, D. W., & James, W. P. T. (2005). Obesity. Lancet, 366(9492), 1197–1209. Igalens, J., & Roussel, P. (1999). A study of the relationships between compensation package, work motivation, and job satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 1003–1025. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Harmon-Jones, E. (2004). On the relationship of frontal brain activity and anger: Examining the role of attitude toward anger. Cognition and Emotion, 18, 337–361. Hayes, J., Chakraborty, A. T., McManus, S., Bebbington, P., Brugha, T., Nicholson, S., & King, M. (2012). Prevalence of same-sex behavior and orientation in England: results from a national survey. Archives of sexual behavior, 41(3), 631–639. Hebb, D. O. (1955). Drives and the CNS (conceptual nervous system). Psychological Review, 62, 243–254. Hejmadi, A., Davidson, R. J., & Rozin, P. (2000). Exploring Hindu Indian emotion expressions: Evidence for accurate recognition by Americans and Indians. Psychological Science, 11, 183–187. Hektner, J. M., Schmidt, J. A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2007). Experience sampling method: Measuring the quality of everyday life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Heller, W. (1993). Neuropsychological mechanisms of individual differences in emotion, personality, and arousal. Neuropsychology, 7, 486–489. Herman, C. P., Roth, D. A., & Polivy, J. (2003). Effects of the presence of others on food intake: A normative interpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 873–886. Herrington, J. D., Heller, W., Mohanty, A., Engels, A. S., et al. (2010). Localization of asymmetric brain function in emotion and depression. Psychophysiology, 11, 11. Herz, R. S., & Cahill, E. D. (1997). Differential use of sensory information in sexual behavior as a function of gender. Human Nature, 8, 275–286. Herzog, D. B., Dorer, D. J., Keel, P. K., Selwyn, S. E., et al. (1999). Recovery and relapse in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: A 7.5-year follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 829–837. Heuer, B. N. (1969). Maori women in traditional family and tribal life. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 78(4), 448-494. Heymsfield, S. B., Greenberg, A. S., Fujioa, K., Dixon, R. M., et al. (1999). Recombinant leptin for weight loss in obese and lean adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 1568–1575. Ilgen, D. R., & Pulakos, E. D. (Eds.). (1999). The changing nature of performance: Implications for staffing, motivation, and development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Izard, C. E. (1977). Human emotions. New York: Plenum. Izard, C. E. (2007). Basic emotions, natural kinds, emotion schemas, and a new paradigm. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 260–280. Jago, R., Baranowski, T., Baranowski, J. C., Thompson, D., & Greaves, K. A. (2005). BMI from 3–6 years of age is predicted by TV viewing and physical activity, not diet. International Journal of Obesity, 29, 557–564. James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology. New York: Holt. Jancke, L., & Kaufmann, N. (1994). Facial EMG responses to odors in solitude and with an audience. Chemical Senses, 19, 99–111. Janowitz, H. D. (1967). Role of gastrointestinal tract in the regulation of food intake. In C. F. Code (Ed.), Handbook of physiology: Vol. 6. Alimentary canal. Washington, DC: American Physiological Society. Jemmott, J. B., Jemmott, L. S., & Fong, G. T. (2010). Efficacy of a theory-based abstinence-only intervention over 24 months: A randomized controlled trial with young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164, 152–159. Jiang, T., Soussignan, R., Rigaud, D., Martin, S., et al. (2008). Alliesthesia to food cues: Heterogeneity across stimuli and sensory modalities. Physiology and Behavior, 95, 464–470. Johnson, J., & Vickers, Z. (1993). Effects of flavor and macronutrient composition of food servings on liking, hunger, and subsequent intake. Appetite, 21, 25–39. Johnson, S. L., McPhee, L., & Birch, L. L. (1991). Conditioned preferences: Young children prefer flavors associated with high dietary fat. Physiology and Behavior, 50, 1245–1251. Hill, J. O., & Peters, J. C. (1998). Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science, 280, 1371–1374. Joseph, J. E., Liu, X., Jiang, Y., Lynam, D., & Kelly, T. (2009). Neural correlates of emotional reactivity in sensation seeking. Psychological Science, 20, 215–223. Hines, M., Brook, C., & Conway, G. (2004). Androgen and psychosexual development: Core gender identity, sexual orientation, and recalled childhood gender role behavior in women and men with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Journal of Sex Research, 41, 75–81. Kanoski, S. E., Fortin, S. M., Ricks, K. M., & Grill, H. J. (2013). Ghrelin signaling in the ventral hippocampus stimulates learned and motivational aspects of feeding via PI3KAkt signaling. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 915–923. Hohmann, G. W. (1966). Some effects of spinal cord lesions on experienced emotional feelings. Psychophysiology, 3, 143–156. Honts, C. R., & Quick, B. D. (1995). The polygraph in 1996: Progress in science and the law. North Dakota Law Review, 71, 997–1020. Karnik, S., & Kanekar, A. (2015). Childhood obesity: a global public health crisis. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(1), 1–7. Kasen, S., Cohen, P., Chen, H., & Must, A. (2008). Obesity and psychopathology in women: A three-decade prospective study. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 558–566. Hooker, E. (1993). Reflections of a 40-year exploration: A scientific view on homosexuality. American Psychologist, 48, 450–453. Kasser, T., & Sharma, Y. S. (1999). Reproductive freedom, educational equality, and females’ preference for resource-acquisition characteristics in mates. Psychological Science, 10, 374–377. Hopf, H. C., Muller, F. W., & Hopf, N. J. (1992). Localization of emotional and volitional facial paresis. Neurology, 42, 1918–1923. Katkin, E. S., Wiens, S., & Öhman, A. (2001). Nonconscious fear conditioning, visceral perception, and the development of gut feelings. Psychological Science, 12, 366–370. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 536 26/07/17 11:23 AM 537 Further reading Katzell, R. A., & Thompson, D. E. (1990). Work motivation: Theory and practice. American Psychologist, 45, 144–153. Kring, A. M., & Gordon, A. H. (1998). Sex differences in emotion: Expression, experience, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 686–703. Kauffman, N. A., Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1995). Hunger-induced finickiness in humans. Appetite, 24, 203–218. Krykouli, S. E., Stanley, B. G., Seirafi, R. D., & Leibowitz, S. F (1990). Stimulation of feeding by galanin: Anatomical localization and behavioral specificity of this peptide’s effects in the brain. Peptides, 11, 995–1001. Kaye, W. H., Klump, K. L., Frank, G. K., & Strober, M. (2000). Anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Annual Review of Medicine, 51, 299–313. Kaye, W. H., Wierenga, C. E., Bailer, U. F., Simmons, A. N., & Bischoff-Grethe, A. (2013). Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels: The neurobiology of anorexia nervosa. Trends in Neurosciences, 36(2), 110–120. Keeling, L. J., & Hurink, J. F. (1996). Social facilitation acts more on the consummatory phase on feeding behaviour. Animal Behaviour, 52, 11–15. Keenan, P. S. (2009). Smoking and weight change after new health diagnoses in older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169, 237–242. Keesey, R. E., & Powley, T. L. (1986). The regulation of body weight. Annual Review of Psychology, 37, 109–133. Kelesidis, T., Kelesidis, L., Chou, S., & Mantzoros, C. S. (2010). The role of leptin in human physiology: Emerging clinical applications. Annals of Internal Medicine, 152, 93–100. Kurdek, L. A. (2005). What do we know about gay and lesbian couples? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 251–254. Kusyszyn, I. (1990). Existence, effectance, esteem: From gambling to a new theory of human motivation. International Journal of the Addictions, 25, 159–177. LaBar, K. S., Gatenby, J. C., Gore, J. C., LeDoux, J. E., & Phelps, E. A. (1998). Human amygdala activation during conditioned fear acquisition and extinction: A mixed-trial fMRI study. Neuron, 20, 937–945. LaFrance, M., Hecht, M. A., & Paluck, E. L. (2003). The contingent smile: A metaanalysis of sex differences in smiling. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 305–334. Lakhi, S., Snow, W., & Fry, M. (2013). Insulin modulates the electrical activity of subfornical organ neurons. NeuroReport, 24(6), 329–334. Lalumière, M. L., Blanchard, R., & Zucker, K. J. (2000). Sexual orientation and handedness in men and women: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 575–592. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Kelly, T., Yang, W., Chen, C.-S., Reynolds, K., & He, J. (2008). Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 1431–1437. Kuo, L. E., Kitlinska, J. B., Tilan, J. U., Li, L., et al. (2007). Neuropeptide Y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature Medicine, 13, 803–811. ly Kaulfuss, P., & Mills, D. S. (2008). Neophilia in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and its implication for studies of dog cognition. Animal Cognition, 11, 553–556. Kemps, E., Tiggemann, M., & Grigg, M. (2008). Food cravings consume limited cognitive resources. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 14, 247–254. Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M., Gilman, S. E., & Kessler, R. C. (2000). Sexual orientation in a U.S. national sample of twin and nontwin sibling pairs. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1843–1846. Lang, P. J. (1995). The emotion probe: Studies of motivation and attention. American Psychologist, 50, 372–385. Larsen, J. T., McGraw, A. P., Mellers, B. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). The agony of victory and thrill of defeat: Mixed emotional reactions to disappointing wins and relieving losses. Psychological Science, 15, 325–330. Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 292–314. Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Kensinger, E. A., & Corkin, S. (2004). Two routes to emotional memory: Distinct neural processes for valence and arousal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101, 3310–3315. Laumann, E. O., & Michael, R. T. (Eds.). (2000). Sex, love, and health in America: Private choices and public policies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill. Kent, S., Rodriguez, F., Kelley, K. W., & Dantzer, R. (1994). Reduction in food and water intake induced by microinjection of interleukin-1b in the ventromedial hypothalamus of the rat. Physiology and Behavior, 56, 1031–1036. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press. Kimura, D. (1999). Sex and cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. King, B. M. (2013). The modern obesity epidemic, ancestral hunter-gatherers, and the sensory/reward control of food intake. American Psychologist, 68(2), 88–96. Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: Saunders. Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia: Saunders. Kircher, J. C., Horowitz, S. W., & Raskin, D. C. (1988). Meta-analysis of mock crime studies of the control question polygraph technique. Law and Human Behavior, 12, 79–90. Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. LeDoux, J. E. (1995). Emotion: Clues from the brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 46, 209–235. le Grange, D., Crosby, R. D., Rathouz, P. J., & Leventhal, B. L. (2007). A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(9), 1049-1056. Leibel, R. L., Rosenbaum, M., & Hirsch, J. (1995). Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. New England Journal of Medicine, 332, 621–628. Leibowitz, S. F. (1992). Neurochemical-neuroendocrine systems in the brain controlling macronutrient intake and metabolism. TINS, 15, 491–497. Kishi, T., & Elmquist, J. K. (2005). Body weight is regulated by the brain: A link between feeding and emotion. Molecular Psychiatry, 10, 132–146. Leknes, S., Brooks, J. C. W., Wiech, K., & Tracey, I. (2008). Pain relief as an opponent process: A psychophysical investigation. European Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 794–801. Kivimäki, M., Lawlor, D. A., Singh-Manoux, A., Batty, D., et al. (2009). Common mental disorder and obesity: Insight from four repeat measures over 19 years: Prospective Whitehall II cohort study. British Medical Journal, 339, b3765. Levenson, R. W., Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1990). Voluntary facial action generates emotion-specific autonomic nervous system activity. Psychophysiology, 27, 363–384. Klein, H. J., Wesson, M. J., Hollenbeck, J. R., & Alge, B. J. (1999). Goal commitment and the goal-setting process: Conceptual clarification and empirical synthesis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 885–896. Levenson, R. W., Ekman, P., Heider, K., & Friesen, W. V. (1992). Emotion and autonomic nervous system activity in the Minangkabau of West Sumatra. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 972–988. Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1998). Feedback interventions: Toward the understanding of a double-edged sword. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 7, 67–72. Levitsky, D. A., Iyer, S., & Pacanowski, C. R. (2012). Number of foods available at a meal determines the amount consumed. Eating Behaviors, 13(3), 183-187. Knafo, A., Iervolino, A. C., & Plomin, R. (2005). Masculine girls and feminine boys: Genetic and environmental contributions to atypical gender development in early childhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 400–412. Li, W., Dowd, S. E., Scurlock, B., Acosta-Martinez, V., & Lyte, M. (2009). Memory and learning behavior in mice is temporally associated with diet-induced alterations in gut bacteria. Physiology & Behavior, 96(4–5), 557–567. Kolonin, M. G., Saha, P. K., Chan, L., Pasqualini, R., & Arap, W. (2004). Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue. Nature Medicine, 10, 625–632. Lin, L., Umahara, M., York, D. A., & Bray, G. A. (1998). Beta-casomorphins stimulate and enterostatin inhibits the intake of dietary fat in rats. Peptides, 19, 325–331. Korda, R. J., Joshy, G., Jorm, L. R., Butler, J. R., & Banks, E. (2012). Inequalities in bariatric surgery in Australia: findings from 49,364 obese participants in a prospective cohort study. Medical Journal of Australia, 197(11), 631-6. Lindau, S. T., & Gavrilova, N. (2010). Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: Evidence from two U.S. population based cross-sectional surveys of ageing. British Medical Journal, 340, c810. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 537 26/07/17 11:23 AM 538 Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Lindau, S. T., Schumm, L. P., Laumann, E. O., Levinson, W., et al. (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 762–774. McClelland, D. C. (1958). Risk-taking in children with high and low need for achievement. In J. W. Atkinson (Ed.), Motives in fantasy, action, and society (pp. 306–321). Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand. Lippa, R. A. (2003). Are 2D:4D finger-length ratios related to sexual orientation? Yes for men, no for women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 179–188. McClelland, D. C. (1985). Human motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman. Locke, E. A., & Latham G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal-setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57, 705–717. Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 75–98. Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. (2009). Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. New England Journal of Medicine, 361, 445–454. Loucas, C. E., Fairburn, C. G., Whittington, C., Pennant, M. E., Stockton, S., & Kendall, T. (2014). E-therapy in the treatment and prevention of eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 63, 122–131. McClure, E. B. (2000). A meta-analytic review of sex differences in facial expression processing and their development in infants, children, and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 424–453. McConaghy, N., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Stevens, C., Manicavasagar, V., et al. (2006). Fraternal birth order and ratio of heterosexual/homosexual feelings in women and men. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 161–174. Mehl, M. R., Vazire, S., Holleran, S. E., & Clark, C. S. (2010). Eavesdropping on happiness: Well-being is related to having less small talk and more substantive conversations. Psychological Science, 21, 539–541. Mesagno, C., & Marchant, D. (2013). Characteristics of polar opposites: An exploratory investigation of choking-resistant and choking-susceptible athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 25(1), 72-91. Mesquita, B., & Frijda, N. H. (1992). Cultural variations in emotions: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 179–204. ly Llewellyn, C. H., Trzaskowski, M., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Plomin, R., & Wardle, J. (2014). Satiety mechanisms in genetic risk of obesity. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(4), 338–344. Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 477–507. Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. Lundy, R. F., Jr. (2008). Gustatory hedonic value: Potential function for forebrain control of brainstem taste processing. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32, 1601–1606. Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Dolezal, C., Baker, S., & New, M. (2008). Sexual orientation in women with classical or nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia as a function of degree of prenatal androgen excess. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 85–99. Luppino, F. S., de Wit, L. M., Bouvy, P. F., Stijnen, T., et al. (2010). Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 220–229. Mezzacappa, E. S., Katkin, E. S. & Palmer, S. N. (1999). Epinephrine, arousal and emotion: A new look at two-factor theory. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 181–199. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: Does happiness change after major life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 75–79. Lustig, R. H., Sen, S., Soberman, J. E., & Velasquez-Mieyer, P. A. (2004). Obesity, leptin resistance, and the effects of insulin reduction. International Journal of Obesity, 28, 1344–1348. Luthar, S. S., & Latendresse, S. J. (2005). Children of the affluent. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 49–53. Lykken, D. T. (1998). A tremor in the blood: Uses and abuses of the lie detector. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. Lykken, D. T. (1999). Happiness: What studies on twins show us about nature, nurture, and the happiness set point. New York: Golden Books. Maljaars, P. W. J., Peters, H. P. F., Mela, D. J., & Masclee, A. A. M. (2008). Ileal brake: A sensible food target for appetite control—a review. Physiology and Behavior, 95, 271–281. Marsh, A. A., Ambady, N., & Kleck, R. E. (2005). The effects of fear and anger facial expressions on approach- and avoidance-related behaviors. Emotion, 5, 119–124. Marsh, A. A., Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2003). Nonverbal ‘accents’: Cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. Psychological Science, 14, 373–377. Marshall, S. J., Biddle, S. J., Gorely, T., Cameron, N., & Murdey, I. (2004). Relationships between media use, body fatness and physical activity in children and youth: A metaanalysis. International Journal of Obesity, 28, 1238–1246. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row. Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human sexual response. Boston: Little, Brown. Matsumoto, D., & Ekman, P. (1989). American-Japanese cultural differences in intensity ratings of facial expressions of emotion. Motivation and Emotion, 13, 143–157. Matsumoto, D., & Willingham, B. (2006). The thrill of victory and the agony of defeat: Spontaneous expressions of medal winners of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 568–581. Michael, R. T., Wadsworth, J., Feinleib, J., Johnson, A. M., et al. (1998). Private sexual behavior, public opinion, and public health policy related to sexually transmitted diseases: A U.S.-British comparison. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 749–754. Miller, N. E. (1959). Liberalization of basic S-R concepts: Extensions to conflict behavior, motivation, and social learning. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of science (Vol. 2, pp. 196–292). New York: McGraw-Hill. Mogenson, G. J. (1976). Neural mechanisms of hunger: Current status and future prospects. In D. Novin, W. Wyrwicka, & G. Bray (Eds.), Hunger: Basic mechanisms and clinical applications. New York: Raven. Moller, A. C., Elliot, A. J., & Friedman, R. (2008). When competence and love are at stake: Achievement goals and perceived closeness to parents in an achievement context. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1386–1391. Morino, M., Toppino, M., Forestieri, P., Angrisani, L., et al. (2007). Mortality after bariatric surgery: Analysis of 13,871 morbidly obese patients from a national registry. Annals of Surgery, 246, 1002–1007. Morisano, D., Hirsh, J. B., Peterson, J. B., Pihl, R. O., & Shore, B. M. (2010). Setting, elaborating, and reflecting on personal goals improves academic performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 255–264. Morris, J. S., Friston, K. J., Buchel, C., Frith, C. D., et al. (1998). A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain, 121, 47–57. Morton, G. J., Cummings, D. E., Baskin, D. G., Barsh, G. S., & Schwartz, M. W. (2006). Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature, 443, 289–295. Müller, T. D., Föcker, M., Holtkamp, K., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., & Hebebrand, J. (2009). Leptin-mediated neuroendocrine alterations in anorexia nervosa: Somatic and behavioral implications. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18(1), 117–129. Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford University Press. Matsumoto, D., & Willingham, B. (2009). Spontaneous facial expressions of emotion of congenitally and noncongenitally blind individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 1–10. Mustanski, B. S., Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2002). A critical review of recent biological research on human sexual orientation. Annual Review of Sex Research, 13, 89–140. Mayer, F. S., & Sutton, K. (1996). Personality: An integrative approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Myers, D. G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55, 56–57. Maynard, D. C., Joseph, T. A., & Maynard, A. M. (2006). Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 509–536. Nader, K., Bechara, A., & Van der Kooy, D. (1997). Neurobiological constraints on behavioral models of motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 85–114. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 538 26/07/17 11:23 AM 539 Further reading National Center for Health Statistics. (2007). Sexual behavior and selected health measures: Men and women 15–44 years of age, United States, 2002. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Powley, T. L., & Keesey, R. E. (1970). Relationship of body weight to the lateral hypothalamic feeding syndrome. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 70, 25–36. Neher, A. (1991). Maslow’s theory of motivation: A critique. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 31, 89–112. Pradhan, G., Samson, S. L., & Sun, Y. (2013). Ghrelin: Much more than a hunger hormone. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 16(6), 619–624. Neovius, M., & Narbro, K. (2008). Cost-effectiveness of pharmacological anti-obesity treatments: A systematic review. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 1752–1763. Priego, T., Sánchez, J., Palou, A., & Picó, C. (2010). Leptin intake during the suckling period improves the metabolic response of adipose tissue to a high-fat diet. International Journal of Obesity, 34, 809–819. Nickerson, C., Schwarz, N., Diener, E., & Kahneman, D. (2003). Zeroing in on the dark side of the American dream: A closer look at the negative consequences of the goal for financial success. Psychological Science, 14, 531–536. Nicotra, A., Critchley, H. D., Mathias, C. J., & Dolan, R. J. (2006). Emotional and autonomic consequences of spinal cord injury explored using functional brain imaging. Brain, 129, 718–728. Niiya, Y., Crocker, J., & Bartmess, E. N. (2004). From vulnerability to resilience: Learning orientations buffer contingent self-esteem from failure. Psychological Science, 15, 801–805. Nobata, T., Hakoda, Y., & Ninose, Y. (2010). The functional field of view becomes narrower while viewing negative emotional stimuli. Cognition & Emotion, 24(5), 886–891. Quoidback, J., Dunn, E. W., Petrides, K. V., & Mikolajczak, M. (2010). Money giveth, money taketh away: The dual effect of wealth on happiness. Psychological Science, 21, 759–763. Raskin, D. C. (1986). The polygraph in 1986: Scientific, professional, and legal issues surrounding applications and acceptance of polygraph evidence. Utah Law Review, 1, 29–74. Redd, M., & de Castro, J. M. (1992). Social facilitation of eating: Effects of social instruction on food intake. Physiology and Behavior, 52, 749–754. Reeve, J. M. (1996). Understanding motivation and emotion. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Reisenzein, R. (1983). The Schachter theory of emotion: Two decades later. Psychological Bulletin, 94, 239–264. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Oakley Browne, M. A., Wells, J. E., & Scott, K. M. (Eds). (2006). Te rau hinengaro: The New Zealand mental health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Puts, D. A. (2005). Mating context and menstrual phase affect female preferences for male voice pitch. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 388–397. ly New Zealand Ministry of Health. 2015. Annual Update of Key Results 2014/15: New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Oettingen, G., Pak, H., & Schnetter, K. (2001). Self-regulation of goal setting: Turning free fantasies about the future into binding goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 736–753. Öhman, A., & Mineka, S. (2003). The malicious serpent: Snakes as a prototypical stimulus for an evolved module of fear. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 5–9. Paoletti, M. G. (1995). Biodiversity, traditional landscapes, and agroecosystem management. Landscape and Urban Planning, 31, 117–128. Park, H. J., Li, R. X., Kim, J., Kim, S. W., et al. (2009). Neural correlates of winning and losing while watching soccer matches. International Journal of Neuroscience, 119, 76–87. Parker, J. A., & Bloom, S. R. (2012). Hypothalamic neuropeptides and the regulation of appetite. Neuropharmacology, 63(1), 18–30. Parsons, T. J., Power, C., & Manor, O. (2005). Physical activity, television viewing and body mass index: A cross-sectional analysis from childhood to adulthood in the 1958 British cohort. International Journal of Obesity, 29, 1212–1221. Pathela, P., Hajat, A., Schillinger, J., Blank, S., et al. (2006). Discordance between sexual behavior and self-reported sexual identity: A population-based survey of New York City men. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145, 416–425. Patterson, C. J. (2004). Lesbian and gay parents and their children: Summary of research findings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http:// www.apa.org/pi/parent.html Peciña, S. (2008). Opioid reward ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ in the nucleus accumbens. Physiology and Behavior, 94, 675–680. Peck, J. W. (1978). Rats defend different body weights depending on palatability and accessibility of their food. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 92, 555–570. Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2009). Achievement goals and achievement emotions: Testing a model of their joint relations with academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 115–135. Peplau, L. A. (2003). Human sexuality: How do men and women differ? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 37–40. Perilloux, C., Easton, J., & Buss, D. (2012). The misperception of sexual interest. Psychological Science, 23(2), 146–151. Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 21–38. Phelps, E. A., & LeDoux, J. E. (2005). Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: From animal models to human behavior. Neuron, 48, 175–187. Pillard, R. C., & Bailey, J. M. (1998). Human sexual orientation has a heritable component. Human Biology, 70, 347–365. Pinel, J. P. J., Lehman, D. R., & Assanand, S. (2002). Eating for optimal health: How much should we eat? Comment. American Psychologist, 57, 372–373. Plutchik, R., & Conte, H. R. (Eds.). (1997). Circumplex models of personality and emotions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 539 Remick, A. K., Polivy, J., & Pliner, P. (2009). Internal and external moderators of the effect of variety on food intake. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 434–451. Rice, G., Anderson, C., Risch, H., & Ebers, G. (1999). Male homosexuality: Absence of linkage to microsatellite markers at Xq28. Science, 284, 665–667. Ridaura, V. K., Faith, J. J., Rey, F. E., Cheng, J., Duncan, A. E., Kau, A. L., et al. (2013). Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science, 341(6150), 1241214. Riggio, R. E. (1989). Introduction to industrial/organizational psychology. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman. Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2003). Addiction. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 54, 25–53. Rodgers, R. F., Lowy, A. S., Halperin, D. M., & Franko, D. L. (2016). A meta-analysis examining the influence of pro-eating disorder websites on body image and eating pathology. European Eating Disorders Review, 24(1), 3–8. Root, J. C., Wong, P. S., & Kinsbourne, M. (2006). Left hemisphere specialization for response to positive emotional expressions: A divided output methodology. Emotion, 6, 473–483. Rosen, B. C., & D’Andrade, R. (1959). The psychosocial origins of achievement motivation. Sociometry, 22, 188–218. Rosen, R. (1991). The healthy company. Los Angeles: Tarcher. Rosenfeld, J. P. (1995). Alternative views of Bashore and Rapp’s (1993) alternatives to traditional polygraphy: A critique. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 159–166. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practices Guidelines Team. (2004). Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 659–670. Rozin, P. (2007). Food and eating. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (pp. 391–416). New York: Guilford Press. Rozin, P., Dow, S., Moscovitch, M., & Rajaram, S. (1998). The role of memory for recent eating experiences in onset and cessation of meals. Evidence from the amnesic syndrome. Psychological Science, 9, 392–396. Rozin, P., Kabnick, K., Pete, E., Fischler, C., & Shields, C. (2003). The ecology of eating: Smaller portion sizes in France than in the United States help explain the French paradox. Psychological Science, 14, 450–454. Rubinstein, S., & Caballero, B. (2000). Is Miss America an undernourished role model? Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 1569. Ruscio, J. (2005). Exploring controversies in the art and science of polygraph testing. Skeptical Inquirer, 29, 34–39. Russell, J. A. (1991). Culture and the categorization of emotions. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 426–450. Russell, J. A. (1994). Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expression? A review of the cross-cultural studies. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 102–141. Russell, J. A. (1995). Facial expressions of emotion: What lies beyond minimal universality? Psychological Bulletin, 118, 379–391. 26/07/17 11:23 AM Chapter 10: Motivation and emotion Saint John, W. (2003, September 28). In U.S. funeral industry, triple-wide isn’t a trailer. New York Times, p. 1. Samuel, R., Bergman, M. M., & Hupka-Brunner, S. (2013). The interplay between educational achievement, occupational success, and well-being. Social Indicators Research, 111(1), 75-96. Sarason, I. G. (1984). Stress, anxiety, and cognitive interference: Reactions to tests. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 929–938. Savin-Williams, R. C. (2006). Who’s gay? Does it matter? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 40–44. Saxe, L., & Ben-Shakhar, G. (1999). Admissibility of polygraph tests: The application of scientific standards post-Daubert. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 5, 203–223. Schachter, S., & Singer, J. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review, 69, 379–399. Schlosser, E. (2001). Fast food nation: The dark side of the all-American meal. New York: Houghton Mifflin. Schmidt, A. F., & Kistemaker, L. M. (2015). The sexualized-body-inversion hypothesis revisited: Valid indicator of sexual objectification or methodological artifact?. Cognition, 134, 77-84. Solomon, R. L. (1980). The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: The costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. American Psychologist, 35, 691–712. Sorce, J., Emde, R., Campos, J., & Klinnert, M. (1981, April). Maternal emotional signaling: Its effect on the visual cliff behavior of one-year-olds. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Boston. Springer, K., & Belk, A. (1994). The role of physical contact and association in early contamination sensitivity. Developmental Psychology, 30, 864–868. Stacey, J., & Biblarz, T. J. (2001). (How) Does the sexual orientation of parents matter? American Sociological Review, 66, 159–183. Stanley, B. G., Willett, V. L., Donias, H. W., & Ha-Lyen, H. (1993). The lateral hypothalamus: A primary site mediating excitatory amino-acid-elicited eating. Brain Research, 63, 41–49. Steiner, J. E., Glaser, D., Hawilo, M. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2001). Comparative expression of hedonic impact: Affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 25, 53–74. Steinglass, J., Albano, A. M., Simpson, H. B., Carpenter, K., Schebendach, J., & Attia, E. (2012), Fear of food as a treatment target: Exposure and response prevention for anorexia nervosa in an open series. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45, 615–621. doi:10.1002/eat.20936 Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Scott, K. M., Bruffaerts, R., Simon, G. E., Alonso, J., et al. (2008). Obesity and mental disorders in the general population: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 192–200. Smith, G. T., Simmons, J. R., Flory, K., Annus, A. M., & Hill, K. K. (2007). Thinness and eating expectancies predict subsequent binge-eating and purging behavior among adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 188–197. ly 540 Seligman, M. E. P., Berkowitz, M. W., Catalano, R. F., Damon, W., et al. (2005). The positive perspective on youth development. In D. L. Evans, E. Foa, R. Gur, H. Hendrin, et al. (Eds.), Treating and preventing adolescent mental health disorders: What we know and what we don’t know (pp. 499–529). New York: Oxford University Press. Shackelford, T. K., Schmitt, D. P., & Buss, D. M. (2005). Universal dimensions of human mate preference. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 447–458. Shah, J. (2003). Automatic for the people: How representations of significant others implicitly affect goal pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 661–681. Sheldon, K. M., & King, L (2001). Why positive psychology is necessary. American Psychologist, 56, 216–217. Sherman, R. T., & Thompson, R. A. (2004). The female athlete triad. Journal of School Nursing, 20, 197–202. Sherwin, B. B., & Gelfand, M. M. (1987). The role of androgen in the maintenance of sexual functioning in oophorectomized women. Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 397–409. Siep, N., Roefs, A., Roebroeck, A., Havermans, R., et al. (2009). Hunger is the best spice: An fMRI study of the effects of attention, hunger and calorie content on food reward processing in the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex. Behavioural Brain Research, 198, 149–158. Silverstein, L. B. (1996). Evolutionary psychology and the search for sex differences. American Psychologist, 51, 160–161. Simon-Thomas, E. R., Keltner, D. J., Sauter, D., Sinicropi-Yao, L., & Abramson, A. (2009). The voice conveys specific emotions: Evidence from vocal burst displays. Emotion, 6, 838–846. Sinclair, R. C., Hoffman, C., Mark, M. M., Martin, L. L., & Pickering, T. L. (1994). Construct accessibility and the misattribution of arousal. Psychological Science, 5, 15–19. Skouteris, H., Edwards, S., Rutherford, L., Cutter-MacKenzie, A., Huang, T., & O’Connor, A. (2014). Promoting healthy eating, active play and sustainability consciousness in early childhood curricula, addressing the Ben10™ problem: A randomised control trial. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1. Slentz, C. A., Duscha, B. D., Johnson, J. L., Ketchum, K., et al. (2004). Effects of the amount of exercise on body weight, body composition, and measures of central obesity: STRRIDE—a randomized controlled study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164, 31–39. Slow Food Movement. (2001). Slow food: Collected thoughts on taste, tradition, and the honest pleasures of food. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green. Smith, A., Rissel, C., Richter, J., Grulich, A., & de Visser, R. (2002). Sex in Australia: Summary findings of the Australian Study of Health and Relationships. La Trobe University http://www.latrobe.edu.au/ashr/papers/Sex%20In%20Australia%20 Summary.pdf Smith, D. M., Loewenstein, G., Jankovic, A., & Ubel, P. A. (2009). Happily hopeless: Adaptation to a permanent, but not to a temporary, disability. Health Psychology, 28, 787–791. Smith, G., Bartlett, A., & King, M. (2004). Treatments of homosexuality in Britain since the 1950s—an oral history: the experience of patients. BMJ, 328(7437), 427. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 540 Steinhausen, H.-C., & Weber, S. (2009). The outcome of bulimia nervosa: Findings from one-quarter century of research. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 1284–1293. Stice, E., & Fairburn, C. G. (2003). Dietary and dietary-depressive subtypes of bulimia nervosa show differential symptom presentation, social impairment, comorbidity, and course of illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 1090–1094. Stice, E., & Shaw, H. (2004). Eating disorder prevention programs: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 206–227. Stilling, R. M., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2014). Microbial genes, brain and behavior: Epigenetic regulation of the gut–brain axis. Genes, Brain & Behavior, 13(1), 69–86. Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Broderick, J. E., & Deaton, A. S. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 9985–9990. Strauss, R. S., & Pollack, H. A. (2001). Epidemic increases in childhood overweight, 1986–1998. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 2845–2848. Stroebe, W., Papies, E. K., & Aarts, H. (2008). From homeostatic to hedonic theories of eating: Self-regulatory failure in food-rich environments. Applied Psychology, 57(Suppl. 1), 172–193. Suh, E., Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1996). Events and subjective well-being: Only recent events matter. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1091–1102. Suokas, J. T., Suvisaari, J. M., Gissler, M., Löfman, R., Linna, M. S., Raevuori, A., & Haukka, J. (2013). Mortality in eating disorders: A follow-up study of adult eating disorder patients treated in tertiary care, 1995–2010. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1101–1106. Surtees, P. G., Wainwright, N. W., Luben, R., Khaw, K. T., & Day, N. E. (2006). Mastery, sense of coherence, and mortality: Evidence of independent associations from the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Cohort Study. Health Psychology, 25, 102–110. Suschinsky, K. D., & Lalumière, M. L. (2011). Prepared for anything? An investigation of female genital arousal in response to rape cues. Psychological Science, 22(2), 159–165. doi:10.1177/0956797610394660 Suslow, T., Ohrmann, P., Bauer, J., Rauch, A. V., et al. (2006). Amygdala activation during masked presentation of emotional faces predicts conscious detection of threatrelated faces. Brain and Cognition, 61, 243–248. Swaab, D. E., & Hofman, M. A. (1995). Sexual differentiation of the human hypothalamus in relation to gender and sexual orientation. Trends in Neuroscience, 18, 264–270. Swami, V., & Furnham, A. (2008). The psychology of physical attraction. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. Swinburn, B., & Wood, A. (2013). Progress on obesity prevention over 20 years in Australia and New Zealand. Obesity Reviews, 14(S2), 60–68. Swithers, S. E., & Hall, W. G. (1994). Does oral experience terminate ingestion? Appetite, 23, 113–138. Symons, D. (1979). The evolution of human sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 26/07/17 11:23 AM 541 Further reading Tamashiro, K. L. K., & Bello, N. T. (Eds.). (2008). Special issue on leptin. Physiology and Behavior, 94(5). Weltzin, T. E., Bulik, C. M., McConaha, C. W., & Kaye, W. H. (1995). Laxative withdrawal and anxiety in bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17, 141–146. Tasker, F., & Golombok, S. (1995). Adults raised as children in lesbian families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 203–215. West, R., & Sohal, T. (2006). ‘Catastrophic’ pathways to smoking cessation: Findings from national survey. British Medical Journal, 332, 458–460. Teigen, K. H. (1994). Yerkes-Dodson: A law for all seasons. Theory and Psychology, 4, 525–547. Whitam, F. L., Diamond, M., & Martin, J. (1993). Homosexual orientation in twins: A report on 61 pairs and three triplet sets. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 22, 187–206. Tellegen, A., Lykken, D. T., Bouchard, T. J., Wilcox, K. J., et al. (1988). Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1031–1039. White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66, 297–333. Thorens, B. (2008). Glucose sensing and the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Obesity, 32, S62–S71. Thornton, L. M., Welch, E., Munn-Chernoff, M. A., Lichtenstein, P., & Bulik, C. M. (2016). Anorexia nervosa, major depression, and suicide attempts: shared genetic factors. Suicide and Life-threatening Behaviour, 46(5), 525–534. Tian, H.-G., Nan, Y., Hu, G., Dong, Q.-N., et al. (1995). Dietary survey in a Chinese population. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 49, 27–32. Tinbergen, N. (1989). The study of instinct. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Wilksch, S. M., & Wade, T. D. (2010). Risk factors for clinically significant importance of shape and weight in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 206–215. Williams, T. J., Pepitone, M. E., Christensen, S. E., Cooke, B. M., et al. (2000). Fingerlength ratios and sexual orientation. Nature, 404, 455–456. Winkielman, P., & Berridge, K. C. (2004). Unconscious emotion Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 120–123. Winn, P. (1995). The lateral hypothalamus and motivated behavior: An old syndrome reassessed and a new perspective gained. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 182–187. Winter, D. G. (1996). Personality: Analysis and interpretation of lives. New York: McGraw-Hill. Sa m Ce pl ng e a Co ge py On Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2008). The nonverbal expression of pride: Evidence for cross-cultural recognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 516–530. Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81. ly Thompson, E. M., & Morgan, E. M. (2008). ‘Mostly straight’ young women: Variations in sexual behavior and identity development. Developmental Psychology, 44, 15–21. Treat, T. A., & Viken, R. J. (2010). Cognitive processing of weight and emotional information in disordered eating. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 81–85. Trifiletti, L. B., Shields, W., McDonald, E., Reynaud, F., & Gielen, A. (2006). Tipping the scales: Obese children and child safety seats. Pediatrics, 117, 1197–1202. Tsai, J. L., Levenson, R. W., & McCoy, K. (2006). Cultural and temperamental variation in emotional response. Emotion, 6, 484–497. Tuckman, B. W. (2003). The effect of learning and motivation strategies training on college students’ achievement. Journal of College Student Development, 4, 430–437. Van Bezooijen, R., Otto, S. A., & Heenan, T. A. (1983). Recognition of vocal expression of emotion: A three-nation study to identify universal characteristics. Journal of CrossCultural Psychology, 14, 387–406. Vargas-Perez, H., Ting-a-Kee, R. A., Heinmiller, A., Sturgess, J. E., & van der Kooy, D. (2007). A test of the opponent-process theory of motivation using lesions that selectively block morphine reward. European Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 3713–3718. Vasey, P. L., & VanderLaan, D. P. (2007). Birth order and male androphilia in Samoan fa’afafine. Proceedings of the Royal Society London, B, 274, 1437–1442. Vasilakopoulou, A., & Le Roux, C. W. (2007). Could a virus contribute to weight gain? International Journal of Obesity, 31, 1350–1356. Vetter, M. L., Cardillo, S., Rickels, M. R., & Iqbal, N. (2009). Narrative review: Effect of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150, 94–103. Vingerhoets, G., Berckmoes, C., & Stroobant, N. (2003). Cerebral hemodynamics during discrimination of prosodic and semantic emotion in speech studied by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. Neuropsychology, 17, 93–99. Voracek, M., & Fisher, M. L. (2002). Shapely centrefolds? Temporal change in body measures: Trend analysis. British Medical Journal, 325, 1447–1448. Wadden, T. A., Berkowitz, R. I., Sarwer, D. B., Prus-Wisniewski, R., & Steinberg, C. (2001). Benefits of lifestyle modification in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity: A randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 218–227. Wang, X., Merzenich, M. M., Sameshima, K., & Jenkins, W. M. (1995). Remodelling of hand representation in adult cortex determined by timing of tactile stimulation. Nature, 378, 71–75. Woods, S. C., Schwartz, M. W., Baskin, D. G., & Seeley, R. J. (2000). Food intake and the regulation of body weight. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 255–277. Worthington, R. L., Navarro, R. L., Savoy, H. B., & Hampton, D. (2008). Development, reliability, and validity of the Measure of Sexual Identity Exploration and Commitment (MOSIEC). Developmental Psychology, 44, 22–33. Yahr, P., & Jacobsen, C. H. (1994). Hypothalamic knife cuts that disrupt mating in male gerbils sever efferents and forebrain afferents of the sexually dimorphic area. Behavioral Neuroscience, 108, 735–742. Yan, W. J., Wu, Q., Liang, J., Chen, Y. H., & Fu, X. (2013). How fast are the leaked facial expressions: The duration of micro-expressions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 37(4), 217–230. Yiin, Y.-M., Ackroff, K., & Sclafani, A. (2004). Flavor preferences conditioned by intragastric nutrient infusions in food restricted and unrestricted rats. Physiology and Behavior, 84, 217–231. Youm, Y., & Laumann, E. O. (2002). Social network effects on the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 29, 689–697. Yovel, I., & Mineka, S. (2005). Emotion-congruent attentional biases: The perspective of hierarchical models of emotional disorders. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 785–795. Zajonc, R. B. (1998). Emotions. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 591–634). New York: McGraw-Hill. Zalta, A. K., & Keel, P. K. (2006). Peer influence on bulimic symptoms in college students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 185–189. Zhao, G., Ford, E. S., Dhingra, S., Li, C., et al. (2009). Depression and anxiety among U.S. adults: Associations with body mass index. International Journal of Obesity, 33, 257–266. Zheng, H., Lenard, N. R., Shin, A. C., & Berthoud, H.-R. (2009). Appetite control and energy balance regulation in the modern world: Reward-driven brain overrides repletion signals. International Journal of Obesity, 33, S8–S13. Zhou, J.-N., Hofman, M. A., Gooren, L. J. G., & Swaab, D. F. (1995). A sex difference in the human brain and its relation to transsexuality. Nature, 378, 68–70. Zillmann, D. (1988). Cognition-excitation interdependencies in aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 14, 51–64. Wasylkiw, L., MacKinnon, A., & MacLellan, A. (2012). Exploring the link between selfcompassion and body image in university women. Body Image, 9(2), 236–245. Zuckerman, M. (1979). Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Weingarten, H. P. (1983). Conditioned cues elicit feeding in sated rats: A role for learning in meal initiation. Science, 220, 431–433. Zuckerman, M. (1996). ‘Conceptual clarification’ or confusion in ‘The study of sensation seeking’ by J. S. H. Jackson and M. Maraun. Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 111–114. Wells, J. C. K. (2009). Thrift: A guide to thrifty genes, thrifty phenotypes and thrifty norms. International Journal of Obesity, 33, 1331–1338. 10_bernstein_sb_86302_txt.indd 541 26/07/17 11:23 AM