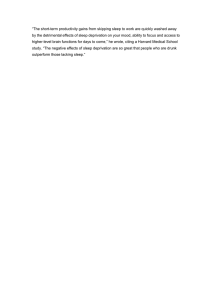

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Sleep and academic performance: measuring the impact of sleep Shelley Hershner Sleep impacts academic performance. Past studies focused on the negative influence of shorter sleep duration and poor sleep quality on GPA. New novel sleep measures have emerged. Sleep consistency measures how likely a student is to be awake or asleep at the same time each day. Students with greater sleep consistency have better academic performance. A morning circadian preference and earlier classes are associated with higher grades. Later high school start times may increase sleep duration, but do not consistently increase GPA, but improve mood and well-being. If a student is struggling academically, screening for a sleep disorder is vital. Devices are under development which may allow students to better monitor their sleep habits, sleep consistency, chronotype and sleep behaviors. For the proactive student, these devices may enhance sleep behaviors and academic performance. Schools need to develop sleep friendly policies and interventions to promote healthy sleep for their students. tasks allow a better understanding of the complex association of sleep, learning and memory. Address Sleep Disorders Center, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States This article will explore the implication of different sleep measures and their impact on GPA and academic performance. Grade point average (GPA) is not a direct measurement of learning or memory. A students’ GPA involves a complex interaction between the student and their environment [2]. Intelligence, motivation, work ethic, personality, socioeconomic status, health problems, current and past school systems, course load, academic program, and test-taking abilities all influence GPA. Research on sleep and GPA evaluate specific sleep aspects with the understanding that these measures will not accommodate the full physiologic facets of sleep. Associations with GPA and sleep measures exist; however, the results are inconsistent [1]. Commonly researched sleep measures include sleep duration, sleep quality, sleep regularity, sleep timing, and sleep disorders (Figure 1). Corresponding author: Hershner, Shelley (shershnr@umich.edu) Sleep duration Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2019, 33:51–56 This review comes from a themed issue on Cognition and perception - *sleep and cognition* Edited by Michael Chee and Philippe Peigneux https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.11.009 2352-1546/ã 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction Sleep is a biologic necessity. Why we sleep is not entirely known but it is a phenomenon observed in some form in all animals. Sleep is a vital component of learning and memory consolidation. Conceptually it is important to understand how research on memory and sleep is performed. Research protocols operate by teaching participants a simplified task, for example, visual processing, and then testing the subject following a night of reduced sleep duration [1]. The change in performance is attributed to the impact of sleep duration. These tasks are often not real-world examples of the activities we perform in our jobs or academically, but the narrowed focus of the www.sciencedirect.com Adequate sleep duration is individual and dependent on age. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine [3] recommends seven or more hours of nightly sleep for adults, while the National Sleep Foundation [4] recommends adolescents obtain 8–10 hours of sleep and younger children significantly more. Ultimately everyone’s sleep requirement is individual and the best gauge of sufficient sleep is waking refreshed and feeling alert during the day. The majority of students obtain inadequate sleep [5,6]. Insufficient sleep is the limited opportunity for sleep rather than the inability to sleep. Insomnia is the inability to fall or stay asleep and should not be equated with insufficient sleep [7]. Short sleep duration is associated with cognitive effects [1,8], performance decrements, cardiovascular disease [9], obesity [10], diabetes, all-cause mortality, hypertension, decreased mood [11], increased risk-taking behaviors and substance use [6]. Shorter sleep duration is associated with lower GPAs [6,12,13]. Among university students those with a GPA <3.0 had the shortest sleep duration [12]. This study also demonstrated lower examination scores based on the prior night’s sleep duration [12], although other studies have not replicated this finding [13]. One of the first studies on GPA showed adolescents aged 13–19 with Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2020, 33:51–56 52 Cognition and perception - *sleep and cognition* Figure 1 Sleep Disorders Timing Quality Sleep Regularity sleep quality are problematic as poor sleep quality can be manifestations of different aspects of sleep and daytime dysfunction. Improvement in poor sleep quality requires a more thorough evaluation from sleep latency, sleep disturbance, sleep hygiene behavior, as well as daytime dysfunction. This is difficult at an individual student level and nearly unattainable at the school level. So although sleep quality is an important measure, it is complicated to design interventions which improve sleep quality. Sleep regularity Duration Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences Sleep measures which impact academic performance and grade point average. average grades of a Cs went to bed later and obtained 3 hours less sleep per week than higher scoring students (B’s and higher) [14]. Other cross-sectional and prospective studies have found variable results of the association of shorter sleep duration and lower academic performance [6,12]. Some of this variability linking GPA and sleep duration may occur as some studies included other sleep measure such as circadian preference and sleep quality. Overall the data, much of it older, suggest that shorter sleep duration is associated with lower grades, but other sleep measures can have an impact. Sleep regularity is a novel sleep measure with growing evidence of importance. It measures how consistent a person’s sleep and wake schedule is across the week. An example of this measure is the Sleep Regularity Index (SRI) [24] which calculates the percentage probability of an individual being in the same state (asleep versus awake) at any two time-points 24-hours apart. The index is scaled such that an individual who sleeps and wakes at the same times daily scores a 100, and an individual who sleeps and wakes at random scores 0. The SRI does not require a main daily sleep episode and therefore can be used among populations with higher sleep variability such as college students. Utilizing the SRI college students were categorized into two groups: Regular and Irregular sleepers (upper and bottom quartile of the SRI respectively). Total sleep duration was not different between the groups. Sleep regularity was positively associated with a higher GPA. An increase of 10 in SRI was associated with an increase of 0.1 in the GPA. At the end of the 30day study there was a significant difference in GPA ( p < 0.02) between Irregular (3.42 0.34) and Regular (3.72 0.24) groups. Factors such as circadian misalignment and light exposure contribute to the impact of sleep irregularity on academic performance. Sleep quality Sleep quality is one of the most frequently utilized measures in sleep research. There are multiple validated sleep quality surveys with the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index [15] being one of the most common measures. Sleep quality per Buysse et al. [15] is difficult to define as it is a subjective report on sleep duration, sleep latency, number of arousals and perceived depth of sleep. Poor sleep quality is frequently reported by students [16,17]. Multiple studies have shown an association with poor sleep quality and decreased academic performance among almost all subsets of students [5,13,18,19,20]. In a study among adolescent males, internet use was a mediator between sleep quality and GPA [21]. Overall it appears that sleep quality [15,21,22] might have a stronger association with GPA than sleep duration [23,24]. The subjective experience of sleep, or sleep quality, influences GPA. The challenging issue with sleep quality is its subjective nature. Interventions to increase sleep duration can be developed, but interventions to improve Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2020, 33:51–56 A study utilizing commercially wearable wrist devices found that greater consistency of sleep, sleep quality, and longer duration correlated with better grades [13]. Many devices are available, but studies are challenging as models, program algorithms, and even the commercial availability of these wrist devices change frequently. Wearable devices measureheart rate, steps, and movements. These devices uses movement and heart-rate patterns to estimate sleep. In other words, less movement and heart rate variability are deemed sleep periods and specific sleep stages are based on proprietary algorithms. A recent study found the accuracy of the automated algorithm for sleep was 69%, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.52 0.14 [25]. This particular study tested 100 students in an introductory college chemistry class and used measures of sleep duration, quality, and sleep inconsistency before examinations and assignments. Sleep inconsistency was defined as the standard deviation of the participant’s daily sleep duration with a larger standard deviation www.sciencedirect.com Sleep and GPA Hershner 53 indicating greater sleep inconsistency. Sleep inconsistency correlated with lower academic performance [13]. These studies highlight that the consistency of sleep and wake patterns have an impact on academic performance. Consistency of sleep is particularly challenging for college students who have variable sleep and wake patterns based on having different daily schedules [12]. High school students typically have a fixed wake up time, with ‘catch up sleep’ on the weekends. Sleep educational programs should highlight sleep consistency, while individual college-aged students may want to limit the variability in their class start times. Sleep timing A person’s bed and rise time reflect two aspects: external obligations and circadian preference. External obligations which impact the timing of sleep are typically the first obligation of the day, which for most students is the start of school. When considering sleep specific measures, school start time could be categorized under sleep duration or sleep timing. For this paper it will be considered under sleep timing. A recent study investigated timing of classes and GPA [37]. Data from nearly two million students from Los Angeles County showed a higher grade in the first two classes of the day. The first class was 8 AM. The math GPA increased by 0.072 (SD 0.006) and English GPA by 0.032 (SD 0.006). This has an effect size equivalent to increasing teacher quality by one-fourth standard deviation or half of the gender gap. Analysis was controlled for gender, age, parental education, and low-performing and high-performing students. At least three mechanisms could contribute the difference between morning and afternoon classes: changes in teachers’ teaching quality, changes in students’ learning ability (stamina), or differences in morning and afternoon class attendance. Chronotype was not measured in this study. Similarly, college students have lower grades in later classes despite a longer sleep duration [27]. Each hour of every that classes started later, GPA declined by 0.022 points. A later school start time is beneficial from a mood, behavioral and well-being perspective, but from an academic stand point, the jury is still out. Circadian preference School start time Student’s rise time is often dictated by school start time, employment, or sports practice [12,26,27]. This review will focus on school start time which is an area of robust growth in the literature, legislature, and popular press. Legislatively, in 2019 California passed Senate Bill 328 to mandate a later school start time. Part of the momentum for this law is that multiple studies have shown improvement in mood [28–30], substance use [29], tardiness and disciplinary actions [31], and motor vehicle accidents [32] when high school start times are delayed. Conflicting data exist if a later school start time results in improved academic performance (GPA and standardized tests) and sleep duration. A Cochrane review found no clear association with an improvement in GPA as two studies reported significant positive associations [33,34], one study reported a nonsignificant negative association [35], while another study reported a significant negative association [36]. Other reviews have also shown inconsistent results in regards to academic performance [30]. The Cochrane review found 4 studies with an increase in sleep duration with a later school start time; however, these results should be interpreted cautiously due to variability in research design and methodological limitations [34]. In a study on nine schools with variable school start times, those schools with a later start time students slept longer [29]. Another study demonstrated that a 45-min delay in high school start time initially had a longer sleep duration which did not persist later in the semester [31]. www.sciencedirect.com Circadian preference is a manifestation of a person’s intrinsic internal clock and simplistically can be considered as a spectrum from ‘morning lark to night owl.’ This means that at certain times of the day a student will be more alert or less alert. A commonly used instrument to measure circadian preference is the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire. Circadian preference or chronotype can influence sleep timing and GPA. Conceptually chronotype has an impact on academic performance through several domains: sleep duration, alertness, performance, as well on potentially less measured aspects like conscientiousness and class attendance [38]. The general the pattern has been that evening chronotypes are associated with lower academic performance [38–41] despite adequate performance on measures of memory, processing speed, and cognitive ability [42]. In a study of Iranian students, chronotype (more morning-type) was positively associated with GPA [43]. Chronotype correlated with school achievement even after adjustment for the effects of intelligence and gender. A morning chronotype was associated with increased conscientiousness [38]. The timing of sleep and individual circadian preference influence grade point average. Overall the data suggest morning classes and students with a morning preference have an academic advantage. For students who are significant night owls, interventions targeting students’ ability to fall asleep earlier is a crucial intervention. Further research on school start time is needed with the realization that even if academic performance is not enhanced, improvement in other measures such as mood, wellCurrent Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2020, 33:51–56 54 Cognition and perception - *sleep and cognition* Figure 2 100 90 80 70 60 % 50 GPA<2 GPA>2 40 30 20 10 0 OSA/Snoring RLS/PLMD Insomnia CRSD Hypersomnia Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences Risk of academic failure (GPA < 2.0) based on screening positive for a sleep disorder [39]. being, and motor vehicle accidents indicates successful and essential metrics. Sleep disorders Sleep disorders are classified into multiple domains: sleep related breathing disorders, central disorders of hypersomolence, circadian rhythm sleep wake disorders, sleep related movement disorders, insomnia, and parasomnias [7]. Students with sleep disorders are more likely to have a lower GPA [23,44]. In a study among college students, 27% were at risk for at least one sleep disorder [39], including obstructive sleep apnea, insomnia, hypersomolence, and restless legs syndrome, and circadian rhythm sleep wake disorders. Student who did not screen positive for a sleep disorder had a higher GPA (mean GPA = 2.82, SD = 0.88) than those who reported at least one sleep disorder (mean GPA = 2.65, SD = 0.99 p < 0.01). Students at risk of academic peril (GPA < 2.0) were more likely to screen positive for a sleep disorder (Figure 2). In a longitudinal study of entering college freshman, screening positive for a sleep disorder resulted in a lower GPA and approached significance for a higher likelihood of dropping out of school within three-years [41]. A study evaluating sleep disturbances defined as insufficient or non-restorative sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, poor sleep maintenance and sleep onset insomnia found lower class retention and GPA [45]. Each additional day per week with sleep disturbances increased the probability that a first year student would drop a course by 14% and lowered the GPA approximately 0.02. Among students of different ages, the sensation of ‘restless/aching legs when falling asleep,’ a symptom concerning for restless legs syndrome, occurred more frequently among students categorized with a lower Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2020, 33:51–56 GPA [20]. In this study, snoring, a sign of obstructive sleep apnea, was not significant for a lower academic performance among 6th grade through college-aged students, although the sample size was small. Other studies have found obstructive sleep apnea in school-age children to be associated with poorer academic performance with the best evidence of a negative impact on core domains of math, language arts, and science [46]. Attention Deficient Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity can be the consequence of insufficient, poor-quality sleep, or sleep disorders [47]. ADHD has been associated with restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements, iron deficiency, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea [47,48]. A sleep disorder impacts academic success through several different means such as excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased mood, poorer general health, lower motivation, decreased executive function or directly through the sleep disorder itself [41]. These studies highlight that when a student is struggling academically, screening for a sleep disorder should be considered. Among children presenting with an ADHD symptoms or an ADHD diagnosis, screening for a co-morbid sleep disorder should occur. Future directions Students have responsibility for their sleep patterns. Devices are under development which help students be more accountable for their sleep. A study using commercially available wearables developed specific algorithms to investigate sleep regularity, sleep quality, sleepiness, and chronotype [49]. The purpose of this study was for students www.sciencedirect.com Sleep and GPA Hershner 55 to better understand their own sleep measures to best determine learning strategies, studying habits and behavior decisions. This study did not investigate if sleep awareness changed grade point average, but it is an intriguing concept for students to self-align sleep measure with their own academic goals. Interventions are needed to improve sleep. For example, a recent study with an 8-hour sleep challenge gave extra credit for those students who slept more during the five days of final examinations [50]. Study participants slept 98 min more each night than nonincentivized students with equal academic performance despite a decrease on average of 490 min of wakefulness as compared to the nonincentivized students. Among the students who participated in the challenge, those students with a more consistent sleep schedule performed better academically on the final examination than students with a more erratic sleep schedule. This study highlights that students can embrace positive sleep-related behavioral changes even at a disadvantaged time of the semester. Conclusion There are multiple ways to measure sleep and academic performance. Much of the initial sleep and GPA literature focused on sleep duration and sleep quality, with mixed results. There are limitations to these sleep measuresspecifically sleep duration is typically by self-report and sleep quality is subjective. Recently novel measures of sleep have emerged. When we sleep and how consistently we sleep may have the greatest impact on academic performance. Knowledge of which sleep measures influence GPA is vital. Institutions have a responsibility to develop interventions and policies to help students’ sleep behaviors. Students are not immune to responsibility and should improve their sleep behaviors to the best of their ability. The sleep community, educators, and students need to understand which sleep measures have greatest impact and encourage their implementation among their schools and students. Conflict of interest statement Nothing declared. References and recommended reading Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as: of special interest 1. de Bruin EJ, Van Run C, Staaks J, Meijer AM: Effects of sleep manipulation on cognitive functioning of adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2017, 32:45-57. 2. Soh KC: Grade point average: what’s wrong and what’s the alternative? J Higher Educ Policy Manage 2010, 33:27-36. 3. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, Hall WA, Kotagal S, Lloyd RM, Malow BA, Maski K, Nichols C, Quan SF et al.: Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American academy of sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2016, 12:785-786. www.sciencedirect.com 4. Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Katz ES, Kheirandish-Gozal L et al.: National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 2015, 1:40-43. 5. Kroshus E, Wagner J, Wyrick D, Athey A, Bell L, Benjamin HJ, Grandner MA, Kline CE, Mohler JM, Roxanne Prichard J et al.: Wake up call for collegiate athlete sleep: narrative review and consensus recommendations from the NCAA Interassociation task force on sleep and wellness. Br J Sports Med 2019, 53:731736. 6. Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O: Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2014, 18:75-87. 7. American Academy of Sleep Medicine: International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnositic and Coding Manual. edn 3. Westchester, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. 8. Javaheipour N, Shahdipour N, Noori K, Zarei M, Camilleri JA, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, Eickhoff CR, Rosenzweig I et al.: Functional brain alterations in acute sleep deprivation: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2019, 46:64-73. 9. Deng HB, Tam T, Zee BC, Chung RY, Su X, Jin L, Chan TC, Chang LY, Yeoh EK, Lao XQ: Short sleep duration increases metabolic impact in healthy adults: a population-based cohort study. Sleep 2017, 40. 10. Reutrakul S, Van Cauter E: Sleep influences on obesity, insulin resistance, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 2018, 84:5666. 11. Pires GN, Bezerra AG, Tufik S, Andersen ML: Effects of acute sleep deprivation on state anxiety levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med 2016, 24:109-118. 12. Raley H, Naber J, Cross S, Perlow M: The impact of duration of sleep on academic performance in university students. Madridge J Nurs 2016, 1:11-18. 13. Okano K, Kaczmarzyk JR, Dave N, Gabrieli JDE, Grossman JC: Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students. Sci Learn 2019, 4:16. 14. Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA: Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev 1998, 69:875-887. 15. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiat Res 1989, 28:193-213. 16. Norbury R, Evans S: Time to think: subjective sleep quality, trait anxiety and university start time. Psychiat Res 2019, 271:214219. 17. Becker SP, Jarrett MA, Luebbe AM, Garner AA, Burns, GL, Kofler MJ: Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health 2018, 4:174-181. 18. Adelantado-Renau M, Beltran-Valls MR, Migueles JH, Artero EG, Legaz-Arrese A, Capdevila-Seder A, Moliner-Urdiales D: Associations between objectively measured and self-reported sleep with academic and cognitive performance in adolescents: DADOS study. J Sleep Res 2019, 28:e12811. 19. Turner RW, Vissa K, Hall C, Poling K, Athey A, Alfonso-Miller P, Gehrels J-A, Grandner MA: Sleep problems are associated with academic performance in a national sample of collegiate athletes. J Am Coll Health 2019:1-8. This is the first task force paper directed at sleep of student athletes. It provides a review of four topics central to collegiate athlete sleep: (1) sleep patterns and disorders among collegiate athletes; (2) sleep and optimal functioning among athletes; (3) screening, tracking and assessment of athlete sleep; and (4) interventions to improve sleep. It also presents five consensus recommendations for colleges to improve athletes’ sleep. 20. Pagel J, Kwiatkowski C: Sleep complaints affecting school performance at different educational levels. Front Neurol 2010, 1. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2020, 33:51–56 56 Cognition and perception - *sleep and cognition* 21. Adelantado-Renau M, Diez-Fernandez A, Beltran-Valls MR, Soriano-Maldonado A, Moliner-Urdiales D: The effect of sleep quality on academic performance is mediated by Internet use time: DADOS study. Jornal de pediatria 2019, 95:410-418. 22. Lemma S, Berhane Y, Worku A, Gelaye B, Williams MA: Good quality sleep is associated with better academic performance among university students in Ethiopia. Sleep Breath 2014, 18:257-263. 23. Gaultney JF: College students with ADHD at greater risk for sleep disorders. J Postsecondary Educ Disabil 2014, 27:5-18. 24. Phillips AJK, Clerx WM, O’Brien CS, Sano A, Barger LK, Picard RW, Lockley SW, Klerman EB, Czeisler CA: Irregular sleep/wake patterns are associated with poorer academic performance and delayed circadian and sleep/wake timing. Sci Rep 2017, 7:3216. The authors use a novel measure of sleep, the Sleep Regularity Index to measure the consistency of a students’ sleep and wake periods. The study determined that the regularity of a students’ sleep and wake pattern was associated with GPA, while sleep duration was not. Students with lower SRI scores had lower GPAs. 25. Beattie Z, Oyang Y, Statan A, Ghoreyshi A, Pantelopoulos A, Russell A, Heneghan C: Estimation of sleep stages in a healthy adult population from optical plethysmography and accelerometer signals. Physiol Meas 2017, 38:1968-1979. 26. Martin JS, Gaudreault MM, Perron M, Laberge L: Chronotype, light exposure, sleep, and daytime functioning in high school students attending morning or afternoon school shifts: an actigraphic study. J Biol Rhythm 2016, 31:205-217. 27. Onyper SV, Thacher PV, Gilbert JW, Gradess SG: Class start times, sleep, and academic performance in college: a path analysis. Chronobiol Int 2012, 29:318-335. depending on their school start times? Coll Antropol 2014, 38:889-894. 37. Pope NG: How the time of day affects productivity: evidence from school schedules. Rev Econ Stat 2016, 98:1-11. 38. Tonetti L, Natale V, Randler C: Association between circadian preference and academic achievement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chronobiol Int 2015, 32:792-801. 39. Gaultney JF: The prevalence of sleep disorders in college students: impact on academic performance. J Am Coll Health 2010, 59:91-97. 40. Sivertsen B, Glozier N, Harvey AG, Hysing M: Academic performance in adolescents with delayed sleep phase. Sleep Med 2015, 16:1084-1090. 41. Gaultney JF: Risk for sleep disorder measured during students’ first college semester may predict institutional retention and grade point average over a 3-year period, with indirect effects through self-efficacy. J Coll Stud Retention Res Theory Pract 2015, 18:333-359. 42. Schmidt C, Collette F, Cajochen C, Peigneux P: A time to think: circadian rhythms in human cognition. Cogn Neuropsychol 2007, 24:755-789. 43. Rahafar A, Randler C, Vollmer C, Kasaeian A: Prediction of school achievement through a multi-factorial approach – the unique role of chronotype. Learn Individ Differ 2017, 55:69-74. 44. Meyer M, Hahn EG, Ficker JH, Wiest GH, Lehnert G: Are snoring medical students at risk of failing their exams? Sleep (New York, NY) 1999, 22:205-209. 30. Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, Croft JB: School start times, sleep, behavioral, health, and academic outcomes: a review of the literature. J School Health 2016, 86:363-381. 45. Hartmann ME, Prichard JR: Calculating the contribution of sleep problems to undergraduates’ academic success. Sleep Health 2018, 4:463-471. The authors demonstrate in this study that sleep disturbance is associated with class retention and GPA. Each additional day per week with sleep disturbances increased the probability that a first year student would drop a course by 14% and lowered the GPA approximately 0.02. Stress, binge drinking, marijuana and other illicit drug use had similar or relatively smaller negative associations with academic success as compared to disturbed sleep. This study could be used by college health providers to encourage institutions to utilize more resources to promote healthy sleep on campus. 31. Thacher PV, Onyper SV: Longitudinal outcomes of start time delay on sleep, behavior, and achievement in high school. Sleep 2016, 39:271-281. 46. Galland B, Spruyt K, Dawes P, McDowall PS, Elder D, Schaughency E: Sleep disordered breathing and academic performance: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 136:e934-46. 32. Vorona RD, Szklo-Coxe M, Lamichhane R, Ware JC, McNallen A, Leszczyszyn D: Adolescent crash rates and school start times in two central Virginia counties, 2009-2011: a follow-up study to a southeastern Virginia study, 2007-2008. J Clin Sleep Med 2014, 10:1169-1177. 47. Sciberras E, Heussler H, Berthier J, Lecendreux M: Chapter 4 epidemiology and etiology of medical sleep problems in ADHD. In Sleep and ADHD. Edited by Hiscock H, Sciberras E. Academic Press; 2019:95-117. Sleep problems are frequent in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is can be difficult to determine the relationship between medical sleep problems and ADHD given the overlap in symptoms between conditions. This paper provides an update on the prevalence, and etiology of sleep disorders in children with ADHD. 28. Owens JA: Impact of delaying school start time on adolescent sleep, mood, and behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010, 164:608-614. 29. Wahlstrom KL, Berger AT, Widome R: Relationships between school start time, sleep duration, and adolescent behaviors. Sleep Health 2017, 3:216-221. 33. Edwards F: Early to rise? The effect of daily start times on academic performance. Econ Educ Rev 2012, 31:970-983. 34. Marx R, Tanner-Smith EE, Davison CM, Ufholz LA, Freeman J, Shankar R, Newton L, Brown RS, Parpia AS, Cozma I et al.: Later school start times for supporting the education, health, and well-being of high school students. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 7:Cd009467. This paper present the best evidence to date of the impact of high school start time on multiple domains including academic performance, mood, and well-being. 35. Hinrichs P: When the bell tolls: the effects of school starting times on academic achievement. Educ Finance Policy 2011, 6:486-507. 36. Milic J, Kvolik A, Ivkovie M, Cikes AB, Labak I, Bensie M, Ilakovac V, Zibar Lada, Heffer Marija: Are there differences in students’ school success, biorhythm, and daytime sleepiness Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2020, 33:51–56 48. Wajszilber D, Santiseban JA, Gruber R: Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: impact and management challenges. Nat Sci Sleep 2018, 10:453-480. 49. de Arriba-Pérez F, Caeiro-Rodrı́guez M, Santos-Gago JM: How do you sleep? Using off the shelf wrist wearables to estimate sleep quality, sleepiness level, chronotype and sleep regularity indicators. J Ambient Intell Hum Comput 2018, 9:897917. 50. King E, Scullin MK: The 8-hour challenge: incentivizing sleep during end-of-term assessments. J Inter Des 2019, 44:85-99. A novel and effective intervention that resulted in improved sleep behaviors even during final examinations. www.sciencedirect.com