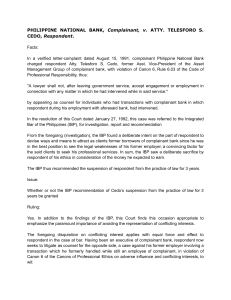

G.R. No. 100113 September 3, 1991 RENATO CAYETANO, petitioner, vs. CHRISTIAN MONSOD, HON. JOVITO R. SALONGA, COMMISSION ON APPOINTMENT, and HON. GUILLERMO CARAGUE, in his capacity as Secretary of Budget and Management, respondents. members of the Philippine Bar who have been engaged in the practice of law for at least ten years.' (Emphasis supplied) Regrettably, however, there seems to be no jurisprudence as to what constitutes practice of law as a legal qualification to an appointive office. Black defines "practice of law" as: We are faced here with a controversy of far-reaching proportions. While ostensibly only legal issues are involved, the Court's decision in this case would indubitably have a profound effect on the political aspect of our national existence. The 1987 Constitution provides in Section 1 (1), Article IX-C: There shall be a Commission on Elections composed of a Chairman and six Commissioners who shall be natural-born citizens of the Philippines and, at the time of their appointment, at least thirty-five years of age, holders of a college degree, and must not have been candidates for any elective position in the immediately preceding -elections. However, a majority thereof, including the Chairman, shall be members of the Philippine Bar who have been engaged in the practice of law for at least ten years. (Emphasis supplied) The aforequoted provision is patterned after Section l(l), Article XII-C of the 1973 Constitution which similarly provides: There shall be an independent Commission on Elections composed of a Chairman and eight Commissioners who shall be natural-born citizens of the Philippines and, at the time of their appointment, at least thirty-five years of age and holders of a college degree. However, a majority thereof, including the Chairman, shall be The rendition of services requiring the knowledge and the application of legal principles and technique to serve the interest of another with his consent. It is not limited to appearing in court, or advising and assisting in the conduct of litigation, but embraces the preparation of pleadings, and other papers incident to actions and special proceedings, conveyancing, the preparation of legal instruments of all kinds, and the giving of all legal advice to clients. It embraces all advice to clients and all actions taken for them in matters connected with the law. An attorney engages in the practice of law by maintaining an office where he is held out to be-an attorney, using a letterhead describing himself as an attorney, counseling clients in legal matters, negotiating with opposing counsel about pending litigation, and fixing and collecting fees for services rendered by his associate. (Black's Law Dictionary, 3rd ed.) The practice of law is not limited to the conduct of cases in court. (Land Title Abstract and Trust Co. v. Dworken, 129 Ohio St. 23, 193 N.E. 650) A person is also considered to be in the practice of law when he: ... for valuable consideration engages in the business of advising person, firms, associations or corporations as to their rights under the law, or appears in a representative capacity as an advocate in proceedings pending or prospective, before any court, commissioner, referee, board, body, committee, or commission constituted by law or authorized to settle controversies and there, in such representative capacity performs any act or acts for the purpose of obtaining or defending the rights of their clients under the law. Otherwise stated, one who, in a representative capacity, engages in the business of advising clients as to their rights under the law, or while so engaged performs any act or acts either in court or outside of court for that purpose, is engaged in the practice of law. (State ex. rel. Mckittrick v..C.S. Dudley and Co., 102 S.W. 2d 895, 340 Mo. 852) This Court in the case of Philippine Lawyers v.Agrava, (105 Phil. 173,176-177) stated: Association The practice of law is not limited to the conduct of cases or litigation in court; it embraces the preparation of pleadings and other papers incident to actions and special proceedings, the management of such actions and proceedings on behalf of clients before judges and courts, and in addition, conveying. In general, all advice to clients, and all action taken for them in matters connected with the law incorporation services, assessment and condemnation services contemplating an appearance before a judicial body, the foreclosure of a mortgage, enforcement of a creditor's claim in bankruptcy and insolvency proceedings, and conducting proceedings in attachment, and in matters of estate and guardianship have been held to constitute law practice, as do the preparation and drafting of legal instruments, where the work done involves the determination by the trained legal mind of the legal effect of facts and conditions. (5 Am. Jr. p. 262, 263). (Emphasis supplied) Practice of law under modem conditions consists in no small part of work performed outside of any court and having no immediate relation to proceedings in court. It embraces conveyancing, the giving of legal advice on a large variety of subjects, and the preparation and execution of legal instruments covering an extensive field of business and trust relations and other affairs. Although these transactions may have no direct connection with court proceedings, they are always subject to become involved in litigation. They require in many aspects a high degree of legal skill, a wide experience with men and affairs, and great capacity for adaptation to difficult and complex situations. These customary functions of an attorney or counselor at law bear an intimate relation to the administration of justice by the courts. No valid distinction, so far as concerns the question set forth in the order, can be drawn between that part of the work of the lawyer which involves appearance in court and that part which involves advice and drafting of instruments in his office. It is of importance to the welfare of the public that these manifold customary functions be performed by persons possessed of adequate learning and skill, of sound moral character, and acting at all times under the heavy trust obligations to clients which rests upon all attorneys. (Moran, Comments on the Rules of Court, Vol. 3 [1953 ed.] , p. 665-666, citing In re Opinion of the Justices [Mass.], 194 N.E. 313, quoted in Rhode Is. Bar Assoc. v. Automobile Service Assoc. [R.I.] 179 A. 139,144). (Emphasis ours) The University of the Philippines Law Center in conducting orientation briefing for new lawyers (1974-1975) listed the dimensions of the practice of law in even broader terms as advocacy, counselling and public service. One may be a practicing attorney in following any line of employment in the profession. If what he does exacts knowledge of the law and is of a kind usual for attorneys engaging in the active practice of their profession, and he follows some one or more lines of employment such as this he is a practicing attorney at law within the meaning of the statute. (Barr v. Cardell, 155 NW 312) Practice of law means any activity, in or out of court, which requires the application of law, legal procedure, knowledge, training and experience. "To engage in the practice of law is to perform those acts which are characteristics of the profession. Generally, to practice law is to give notice or render any kind of service, which device or service requires the use in any degree of legal knowledge or skill." (111 ALR 23) The following records of the 1986 Constitutional Commission show that it has adopted a liberal interpretation of the term "practice of law." MR. FOZ. Before we suspend the session, may I make a manifestation which I forgot to do during our review of the provisions on the Commission on Audit. May I be allowed to make a very brief statement? THE PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. Jamir). qualifications provided for by Section I is that "They must be Members of the Philippine Bar" — I am quoting from the provision — "who have been engaged in the practice of law for at least ten years". To avoid any misunderstanding which would result in excluding members of the Bar who are now employed in the COA or Commission on Audit, we would like to make the clarification that this provision on qualifications regarding members of the Bar does not necessarily refer or involve actual practice of law outside the COA We have to interpret this to mean that as long as the lawyers who are employed in the COA are using their legal knowledge or legal talent in their respective work within COA, then they are qualified to be considered for appointment as members or commissioners, even chairman, of the Commission on Audit. This has been discussed by the Committee on Constitutional Commissions and Agencies and we deem it important to take it up on the floor so that this interpretation may be made available whenever this provision on the qualifications as regards members of the Philippine Bar engaging in the practice of law for at least ten years is taken up. MR. OPLE. Will Commissioner Foz yield to just one question. MR. FOZ. Yes, Mr. Presiding Officer. MR. OPLE. Is he, in effect, saying that service in the COA by a lawyer is equivalent to the requirement of a law practice that is set forth in the Article on the Commission on Audit? The Commissioner will please proceed. MR. FOZ. This has to do with the qualifications of the members of the Commission on Audit. Among others, the MR. FOZ. We must consider the fact that the work of COA, although it is auditing, will necessarily involve legal work; it will involve legal work. And, therefore, lawyers who are employed in COA now would have the necessary qualifications in accordance with the Provision on qualifications under our provisions on the Commission on Audit. And, therefore, the answer is yes. as professional corporations and the members called shareholders. In either case, the members of the firm are the experienced attorneys. In most firms, there are younger or more inexperienced salaried attorneyscalled "associates." (Ibid.). MR. OPLE. Yes. So that the construction given to this is that this is equivalent to the practice of law. The test that defines law practice by looking to traditional areas of law practice is essentially tautologous, unhelpful defining the practice of law as that which lawyers do. (Charles W. Wolfram, Modern Legal Ethics [West Publishing Co.: Minnesota, 1986], p. 593). The practice of law is defined as the performance of any acts . . . in or out of court, commonly understood to be the practice of law. (State Bar Ass'n v. Connecticut Bank & Trust Co., 145 Conn. 222, 140 A.2d 863, 870 [1958] [quoting Grievance Comm. v. Payne, 128 Conn. 325, 22 A.2d 623, 626 [1941]). Because lawyers perform almost every function known in the commercial and governmental realm, such a definition would obviously be too global to be workable.(Wolfram, op. cit.). MR. FOZ. Yes, Mr. Presiding Officer. MR. OPLE. Thank you. ... ( Emphasis supplied) Section 1(1), Article IX-D of the 1987 Constitution, provides, among others, that the Chairman and two Commissioners of the Commission on Audit (COA) should either be certified public accountants with not less than ten years of auditing practice, or members of the Philippine Bar who have been engaged in the practice of law for at least ten years. (emphasis supplied) Corollary to this is the term "private practitioner" and which is in many ways synonymous with the word "lawyer." Today, although many lawyers do not engage in private practice, it is still a fact that the majority of lawyers are private practitioners. (Gary Munneke, Opportunities in Law Careers [VGM Career Horizons: Illinois], [1986], p. 15). At this point, it might be helpful to define private practice. The term, as commonly understood, means "an individual or organization engaged in the business of delivering legal services." (Ibid.). Lawyers who practice alone are often called "sole practitioners." Groups of lawyers are called "firms." The firm is usually a partnership and members of the firm are the partners. Some firms may be organized The appearance of a lawyer in litigation in behalf of a client is at once the most publicly familiar role for lawyers as well as an uncommon role for the average lawyer. Most lawyers spend little time in courtrooms, and a large percentage spend their entire practice without litigating a case. (Ibid., p. 593). Nonetheless, many lawyers do continue to litigate and the litigating lawyer's role colors much of both the public image and the self perception of the legal profession. (Ibid.). In this regard thus, the dominance of litigation in the public mind reflects history, not reality. (Ibid.). Why is this so? Recall that the late Alexander SyCip, a corporate lawyer, once articulated on the importance of a lawyer as a business counselor in this wise: "Even today, there are still uninformed laymen whose concept of an attorney is one who principally tries cases before the courts. The members of the bench and bar and the informed laymen such as businessmen, know that in most developed societies today, substantially more legal work is transacted in law offices than in the courtrooms. General practitioners of law who do both litigation and non-litigation work also know that in most cases they find themselves spending more time doing what [is] loosely desccribe[d] as business counseling than in trying cases. The business lawyer has been described as the planner, the diagnostician and the trial lawyer, the surgeon. I[t] need not [be] stress[ed] that in law, as in medicine, surgery should be avoided where internal medicine can be effective." (Business Star, "Corporate Finance Law," Jan. 11, 1989, p. 4). In the course of a working day the average general practitioner wig engage in a number of legal tasks, each involving different legal doctrines, legal skills, legal processes, legal institutions, clients, and other interested parties. Even the increasing numbers of lawyers in specialized practice wig usually perform at least some legal services outside their specialty. And even within a narrow specialty such as tax practice, a lawyer will shift from one legal task or role such as advice-giving to an importantly different one such as representing a client before an administrative agency. (Wolfram, supra, p. 687). By no means will most of this work involve litigation, unless the lawyer is one of the relatively rare types — a litigator who specializes in this work to the exclusion of much else. Instead, the work will require the lawyer to have mastered the full range of traditional lawyer skills of client counselling, advice-giving, document drafting, and negotiation. And increasingly lawyers find that the new skills of evaluation and mediation are both effective for many clients and a source of employment. (Ibid.). Most lawyers will engage in non-litigation legal work or in litigation work that is constrained in very important ways, at least theoretically, so as to remove from it some of the salient features of adversarial litigation. Of these special roles, the most prominent is that of prosecutor. In some lawyers' work the constraints are imposed both by the nature of the client and by the way in which the lawyer is organized into a social unit to perform that work. The most common of these roles are those of corporate practice and government legal service. (Ibid.). In several issues of the Business Star, a business daily, herein below quoted are emerging trends in corporate law practice, a departure from the traditional concept of practice of law. We are experiencing today what truly may be called a revolutionary transformation in corporate law practice. Lawyers and other professional groups, in particular those members participating in various legal-policy decisional contexts, are finding that understanding the major emerging trends in corporation law is indispensable to intelligent decision-making. Constructive adjustment to major corporate problems of today requires an accurate understanding of the nature and implications of the corporate law research function accompanied by an accelerating rate of information accumulation. The recognition of the need for such improved corporate legal policy formulation, particularly "modelmaking" and "contingency planning," has impressed upon us the inadequacy of traditional procedures in many decisional contexts. In a complex legal problem the mass of information to be processed, the sorting and weighing of significant conditional factors, the appraisal of major trends, the necessity of estimating the consequences of given courses of action, and the need for fast decision and response in situations of acute danger have prompted the use of sophisticated concepts of information flow theory, operational analysis, automatic data processing, and electronic computing equipment. Understandably, an improved decisional structure must stress the predictive component of the policy-making process, wherein a "model", of the decisional context or a segment thereof is developed to test projected alternative courses of action in terms of futuristic effects flowing therefrom. the business issue raised. (Business Star, "Corporate Finance Law," Jan. 11, 1989, p. 4). Although members of the legal profession are regularly engaged in predicting and projecting the trends of the law, the subject of corporate finance law has received relatively little organized and formalized attention in the philosophy of advancing corporate legal education. Nonetheless, a crossdisciplinary approach to legal research has become a vital necessity. Despite the growing number of corporate lawyers, many people could not explain what it is that a corporate lawyer does. For one, the number of attorneys employed by a single corporation will vary with the size and type of the corporation. Many smaller and some large corporations farm out all their legal problems to private law firms. Many others have in-house counsel only for certain matters. Other corporation have a staff large enough to handle most legal problems in-house. Certainly, the general orientation for productive contributions by those trained primarily in the law can be improved through an early introduction to multi-variable decisional context and the various approaches for handling such problems. Lawyers, particularly with either a master's or doctorate degree in business administration or management, functioning at the legal policy level of decisionmaking now have some appreciation for the concepts and analytical techniques of other professions which are currently engaged in similar types of complex decisionmaking. Truth to tell, many situations involving corporate finance problems would require the services of an astute attorney because of the complex legal implications that arise from each and every necessary step in securing and maintaining In our litigation-prone country, a corporate lawyer is assiduously referred to as the "abogado de campanilla." He is the "big-time" lawyer, earning big money and with a clientele composed of the tycoons and magnates of business and industry. A corporate lawyer, for all intents and purposes, is a lawyer who handles the legal affairs of a corporation. His areas of concern or jurisdiction may include, inter alia: corporate legal research, tax laws research, acting out as corporate secretary (in board meetings), appearances in both courts and other adjudicatory agencies (including the Securities and Exchange Commission), and in other capacities which require an ability to deal with the law. At any rate, a corporate lawyer may assume responsibilities other than the legal affairs of the business of the corporation he is representing. These include such matters as determining policy and becoming involved in management. ( Emphasis supplied.) In a big company, for example, one may have a feeling of being isolated from the action, or not understanding how one's work actually fits into the work of the orgarnization. This can be frustrating to someone who needs to see the results of his work first hand. In short, a corporate lawyer is sometimes offered this fortune to be more closely involved in the running of the business. Such corporate legal management issues deal primarily with three (3) types of learning: (1) acquisition of insights into current advances which are of particular significance to the corporate counsel; (2) an introduction to usable disciplinary skins applicable to a corporate counsel's management responsibilities; and (3) a devotion to the organization and management of the legal function itself. Moreover, a corporate lawyer's services may sometimes be engaged by a multinational corporation (MNC). Some large MNCs provide one of the few opportunities available to corporate lawyers to enter the international law field. After all, international law is practiced in a relatively small number of companies and law firms. Because working in a foreign country is perceived by many as glamorous, tills is an area coveted by corporate lawyers. In most cases, however, the overseas jobs go to experienced attorneys while the younger attorneys do their "international practice" in law libraries. (Business Star, "Corporate Law Practice," May 25,1990, p. 4). These three subject areas may be thought of as intersecting circles, with a shared area linking them. Otherwise known as "intersecting managerial jurisprudence," it forms a unifying theme for the corporate counsel's total learning. This brings us to the inevitable, i.e., the role of the lawyer in the realm of finance. To borrow the lines of Harvardeducated lawyer Bruce Wassertein, to wit: "A bad lawyer is one who fails to spot problems, a good lawyer is one who perceives the difficulties, and the excellent lawyer is one who surmounts them." (Business Star, "Corporate Finance Law," Jan. 11, 1989, p. 4). Today, the study of corporate law practice direly needs a "shot in the arm," so to speak. No longer are we talking of the traditional law teaching method of confining the subject study to the Corporation Code and the Securities Code but an incursion as well into the intertwining modern management issues. Some current advances in behavior and policy sciences affect the counsel's role. For that matter, the corporate lawyer reviews the globalization process, including the resulting strategic repositioning that the firms he provides counsel for are required to make, and the need to think about a corporation's; strategy at multiple levels. The salience of the nation-state is being reduced as firms deal both with global multinational entities and simultaneously with sub-national governmental units. Firms increasingly collaborate not only with public entities but with each other — often with those who are competitors in other arenas. Also, the nature of the lawyer's participation in decisionmaking within the corporation is rapidly changing. The modem corporate lawyer has gained a new role as a stakeholder — in some cases participating in the organization and operations of governance through participation on boards and other decision-making roles. Often these new patterns develop alongside existing legal institutions and laws are perceived as barriers. These trends are complicated as corporations organize for global operations. ( Emphasis supplied) Regarding the skills to apply by the corporate counsel, three factors are apropos: The practising lawyer of today is familiar as well with governmental policies toward the promotion and management of technology. New collaborative arrangements for promoting specific technologies or competitiveness more generally require approaches from industry that differ from older, more adversarial relationships and traditional forms of seeking to influence governmental policies. And there are lessons to be learned from other countries. In Europe, Esprit, Eureka and Race are examples of collaborative efforts between governmental and business Japan's MITI is world famous. (Emphasis supplied) First System Dynamics. The field of systems dynamics has been found an effective tool for new managerial thinking regarding both planning and pressing immediate problems. An understanding of the role of feedback loops, inventory levels, and rates of flow, enable users to simulate all sorts of systematic problems — physical, economic, managerial, social, and psychological. New programming techniques now make the system dynamics principles more accessible to managers — including corporate counsels. (Emphasis supplied) Following the concept of boundary spanning, the office of the Corporate Counsel comprises a distinct group within the managerial structure of all kinds of organizations. Effectiveness of both long-term and temporary groups within organizations has been found to be related to indentifiable factors in the group-context interaction such as the groups actively revising their knowledge of the environment coordinating work with outsiders, promoting team achievements within the organization. In general, such external activities are better predictors of team performance than internal group processes. In a crisis situation, the legal managerial capabilities of the corporate lawyer vis-a-vis the managerial mettle of corporations are challenged. Current research is seeking ways both to anticipate effective managerial procedures and to understand relationships of financial liability and insurance considerations. (Emphasis supplied) Second Decision Analysis. This enables users to make better decisions involving complexity and uncertainty. In the context of a law department, it can be used to appraise the settlement value of litigation, aid in negotiation settlement, and minimize the cost and risk involved in managing a portfolio of cases. (Emphasis supplied) Third Modeling for Negotiation Management. Computerbased models can be used directly by parties and mediators in all lands of negotiations. All integrated set of such tools provide coherent and effective negotiation support, including hands-on on instruction in these techniques. A simulation case of an international joint venture may be used to illustrate the point. [Be this as it may,] the organization and management of the legal function, concern three pointed areas of consideration, thus: Preventive Lawyering. Planning by lawyers requires special skills that comprise a major part of the general counsel's responsibilities. They differ from those of remedial law. Preventive lawyering is concerned with minimizing the risks of legal trouble and maximizing legal rights for such legal entities at that time when transactional or similar facts are being considered and made. Managerial Jurisprudence. This is the framework within which are undertaken those activities of the firm to which legal consequences attach. It needs to be directly supportive of this nation's evolving economic and organizational fabric as firms change to stay competitive in a global, interdependent environment. The practice and theory of "law" is not adequate today to facilitate the relationships needed in trying to make a global economy work. Organization and Functioning of the Corporate Counsel's Office. The general counsel has emerged in the last decade as one of the most vibrant subsets of the legal profession. The corporate counsel hear responsibility for key aspects of the firm's strategic issues, including structuring its global operations, managing improved relationships with an increasingly diversified body of employees, managing expanded liability exposure, creating new and varied interactions with public decision-makers, coping internally with more complex make or by decisions. This whole exercise drives home the thesis that knowing corporate law is not enough to make one a good general corporate counsel nor to give him a full sense of how the legal system shapes corporate activities. And even if the corporate lawyer's aim is not the understand all of the law's effects on corporate activities, he must, at the very least, also gain a working knowledge of the management issues if only to be able to grasp not only the basic legal "constitution' or makeup of the modem corporation. "Business Star", "The Corporate Counsel," April 10, 1991, p. 4). The challenge for lawyers (both of the bar and the bench) is to have more than a passing knowledge of financial law affecting each aspect of their work. Yet, many would admit to ignorance of vast tracts of the financial law territory. What transpires next is a dilemma of professional security: Will the lawyer admit ignorance and risk opprobrium?; or will he feign understanding and risk exposure? (Business Star, "Corporate Finance law," Jan. 11, 1989, p. 4). Respondent Christian Monsod was nominated by President Corazon C. Aquino to the position of Chairman of the COMELEC in a letter received by the Secretariat of the Commission on Appointments on April 25, 1991. Petitioner opposed the nomination because allegedly Monsod does not possess the required qualification of having been engaged in the practice of law for at least ten years. On June 5, 1991, the Commission on Appointments confirmed the nomination of Monsod as Chairman of the COMELEC. On June 18, 1991, he took his oath of office. On the same day, he assumed office as Chairman of the COMELEC. Challenging the validity of the confirmation by the Commission on Appointments of Monsod's nomination, petitioner as a citizen and taxpayer, filed the instant petition for certiorari and Prohibition praying that said confirmation and the consequent appointment of Monsod as Chairman of the Commission on Elections be declared null and void. Atty. Christian Monsod is a member of the Philippine Bar, having passed the bar examinations of 1960 with a grade of 86-55%. He has been a dues paying member of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines since its inception in 1972-73. He has also been paying his professional license fees as lawyer for more than ten years. (p. 124, Rollo) After graduating from the College of Law (U.P.) and having hurdled the bar, Atty. Monsod worked in the law office of his father. During his stint in the World Bank Group (1963-1970), Monsod worked as an operations officer for about two years in Costa Rica and Panama, which involved getting acquainted with the laws of member-countries negotiating loans and coordinating legal, economic, and project work of the Bank. Upon returning to the Philippines in 1970, he worked with the Meralco Group, served as chief executive officer of an investment bank and subsequently of a business conglomerate, and since 1986, has rendered services to various companies as a legal and economic consultant or chief executive officer. As former Secretary-General (1986) and National Chairman (1987) of NAMFREL. Monsod's work involved being knowledgeable in election law. He appeared for NAMFREL in its accreditation hearings before the Comelec. In the field of advocacy, Monsod, in his personal capacity and as former CoChairman of the Bishops Businessmen's Conference for Human Development, has worked with the under privileged sectors, such as the farmer and urban poor groups, in initiating, lobbying for and engaging in affirmative action for the agrarian reform law and lately the urban land reform bill. Monsod also made use of his legal knowledge as a member of the Davide Commission, a quast judicial body, which conducted numerous hearings (1990) and as a member of the Constitutional Commission (1986-1987), and Chairman of its Committee on Accountability of Public Officers, for which he was cited by the President of the Commission, Justice Cecilia Muñoz-Palma for "innumerable amendments to reconcile government functions with individual freedoms and public accountability and the party-list system for the House of Representative. (pp. 128-129 Rollo) ( Emphasis supplied) Just a word about the work of a negotiating team of which Atty. Monsod used to be a member. In a loan agreement, for instance, a negotiating panel acts as a team, and which is adequately constituted to meet the various contingencies that arise during a negotiation. Besides top officials of the Borrower concerned, there are the legal officer (such as the legal counsel), the finance manager, and an operations officer (such as an official involved in negotiating the contracts) who comprise the members of the team. (Guillermo V. Soliven, "Loan Negotiating Strategies for Developing Country Borrowers," Staff Paper No. 2, Central Bank of the Philippines, Manila, 1982, p. 11). (Emphasis supplied) After a fashion, the loan agreement is like a country's Constitution; it lays down the law as far as the loan transaction is concerned. Thus, the meat of any Loan Agreement can be compartmentalized into five (5) fundamental parts: (1) business terms; (2) borrower's representation; (3) conditions of closing; (4) covenants; and (5) events of default. (Ibid., p. 13). In the same vein, lawyers play an important role in any debt restructuring program. For aside from performing the tasks of legislative drafting and legal advising, they score national development policies as key factors in maintaining their countries' sovereignty. (Condensed from the work paper, entitled "Wanted: Development Lawyers for Developing Nations," submitted by L. Michael Hager, regional legal adviser of the United States Agency for International Development, during the Session on Law for the Development of Nations at the Abidjan World Conference in Ivory Coast, sponsored by the World Peace Through Law Center on August 26-31, 1973). ( Emphasis supplied) Loan concessions and compromises, perhaps even more so than purely renegotiation policies, demand expertise in the law of contracts, in legislation and agreement drafting and in renegotiation. Necessarily, a sovereign lawyer may work with an international business specialist or an economist in the formulation of a model loan agreement. Debt restructuring contract agreements contain such a mixture of technical language that they should be carefully drafted and signed only with the advise of competent counsel in conjunction with the guidance of adequate technical support personnel. (See International Law Aspects of the Philippine External Debts, an unpublished dissertation, U.S.T. Graduate School of Law, 1987, p. 321). ( Emphasis supplied) A critical aspect of sovereign debt restructuring/contract construction is the set of terms and conditions which determines the contractual remedies for a failure to perform one or more elements of the contract. A good agreement must not only define the responsibilities of both parties, but must also state the recourse open to either party when the other fails to discharge an obligation. For a compleat debt restructuring represents a devotion to that principle which in the ultimate analysis is sine qua non for foreign loan agreements-an adherence to the rule of law in domestic and international affairs of whose kind U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. once said: "They carry no banners, they beat no drums; but where they are, men learn that bustle and bush are not the equal of quiet genius and serene mastery." (See Ricardo J. Romulo, "The Role of Lawyers in Foreign Investments," Integrated Bar of the Philippine Journal, Vol. 15, Nos. 3 and 4, Third and Fourth Quarters, 1977, p. 265). Interpreted in the light of the various definitions of the term Practice of law". particularly the modern concept of law practice, and taking into consideration the liberal construction intended by the framers of the Constitution, Atty. Monsod's past work experiences as a lawyereconomist, a lawyer-manager, a lawyer-entrepreneur of industry, a lawyer-negotiator of contracts, and a lawyer-legislator of both the rich and the poor — verily more than satisfy the constitutional requirement — that he has been engaged in the practice of law for at least ten years. Besides in the leading case of Luego v. Civil Service Commission, 143 SCRA 327, the Court said: Appointment is an essentially discretionary power and must be performed by the officer in which it is vested according to his best lights, the only condition being that the appointee should possess the qualifications required by law. If he does, then the appointment cannot be faulted on the ground that there are others better qualified who should have been preferred. This is a political question involving considerations of wisdom which only the appointing authority can decide. (emphasis supplied) No less emphatic was the Court in the case of (Central Bank v. Civil Service Commission, 171 SCRA 744) where it stated: It is well-settled that when the appointee is qualified, as in this case, and all the other legal requirements are satisfied, the Commission has no alternative but to attest to the appointment in accordance with the Civil Service Law. The Commission has no authority to revoke an appointment on the ground that another person is more qualified for a particular position. It also has no authority to direct the appointment of a substitute of its choice. To do so would be an encroachment on the discretion vested upon the appointing authority. An appointment is essentially within the discretionary power of whomsoever it is vested, subject to the only condition that the appointee should possess the qualifications required by law. ( Emphasis supplied) The appointing process in a regular appointment as in the case at bar, consists of four (4) stages: (1) nomination; (2) confirmation by the Commission on Appointments; (3) issuance of a commission (in the Philippines, upon submission by the Commission on Appointments of its certificate of confirmation, the President issues the permanent appointment; and (4) acceptance e.g., oath-taking, posting of bond, etc. . . . (Lacson v. Romero, No. L-3081, October 14, 1949; Gonzales, Law on Public Officers, p. 200) The power of the Commission on Appointments to give its consent to the nomination of Monsod as Chairman of the Commission on Elections is mandated by Section 1(2) Sub-Article C, Article IX of the Constitution which provides: The Chairman and the Commisioners shall be appointed by the President with the consent of the Commission on Appointments for a term of seven years without reappointment. Of those first appointed, three Members shall hold office for seven years, two Members for five years, and the last Members for three years, without reappointment. Appointment to any vacancy shall be only for the unexpired term of the predecessor. In no case shall any Member be appointed or designated in a temporary or acting capacity. Anent Justice Teodoro Padilla's separate opinion, suffice it to say that his definition of the practice of law is the traditional or stereotyped notion of law practice, as distinguished from the modern concept of the practice of law, which modern connotation is exactly what was intended by the eminent framers of the 1987 Constitution. Moreover, Justice Padilla's definition would require generally a habitual law practice, perhaps practised two or three times a week and would outlaw say, law practice once or twice a year for ten consecutive years. Clearly, this is far from the constitutional intent. Upon the other hand, the separate opinion of Justice Isagani Cruz states that in my written opinion, I made use of a definition of law practice which really means nothing because the definition says that law practice " . . . is what people ordinarily mean by the practice of law." True I cited the definition but only by way of sarcasm as evident from my statement that the definition of law practice by "traditional areas of law practice is essentially tautologous" or defining a phrase by means of the phrase itself that is being defined. Justice Cruz goes on to say in substance that since the law covers almost all situations, most individuals, in making use of the law, or in advising others on what the law means, are actually practicing law. In that sense, perhaps, but we should not lose sight of the fact that Mr. Monsod is a lawyer, a member of the Philippine Bar, who has been practising law for over ten years. This is different from the acts of persons practising law, without first becoming lawyers. Justice Cruz also says that the Supreme Court can even disqualify an elected President of the Philippines, say, on the ground that he lacks one or more qualifications. This matter, I greatly doubt. For one thing, how can an action or petition be brought against the President? And even assuming that he is indeed disqualified, how can the action be entertained since he is the incumbent President? We now proceed: The Commission on the basis of evidence submitted doling the public hearings on Monsod's confirmation, implicitly determined that he possessed the necessary qualifications as required by law. The judgment rendered by the Commission in the exercise of such an acknowledged power is beyond judicial interference except only upon a clear showing of a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction. (Art. VIII, Sec. 1 Constitution). Thus, only where such grave abuse of discretion is clearly shown shall the Court interfere with the Commission's judgment. In the instant case, there is no occasion for the exercise of the Court's corrective power, since no abuse, much less a grave abuse of discretion, that would amount to lack or excess of jurisdiction and would warrant the issuance of the writs prayed, for has been clearly shown. Additionally, consider the following: (1) If the Commission on Appointments rejects a nominee by the President, may the Supreme Court reverse the Commission, and thus in effect confirm the appointment? Clearly, the answer is in the negative. Finally, one significant legal maxim is: We must interpret not by the letter that killeth, but by the spirit that giveth life. Take this hypothetical case of Samson and Delilah. Once, the procurator of Judea asked Delilah (who was Samson's beloved) for help in capturing Samson. Delilah agreed on condition that — No blade shall touch his skin; No blood shall flow from his veins. When Samson (his long hair cut by Delilah) was captured, the procurator placed an iron rod burning white-hot two or three inches away from in front of Samson's eyes. This blinded the man. Upon hearing of what had happened to her beloved, Delilah was beside herself with anger, and fuming with righteous fury, accused the procurator of reneging on his word. The procurator calmly replied: "Did any blade touch his skin? Did any blood flow from his veins?" The procurator was clearly relying on the letter, not the spirit of the agreement. In view of the foregoing, this petition is hereby DISMISSED. SO ORDERED. (2) In the same vein, may the Court reject the nominee, whom the Commission has confirmed? The answer is likewise clear. (3) If the United States Senate (which is the confirming body in the U.S. Congress) decides to confirm a Presidential nominee, it would be incredible that the U.S. Supreme Court would still reverse the U.S. Senate. B.M. No. 2540 September 24, 2013 Roll of Attorneys lost its urgency and compulsion, and was subsequently forgotten."9 IN RE: PETITION TO SIGN IN THE ROLL OF ATTORNEYS MICHAEL A. MEDADO, Petitioner. We resolve the instant Petition to Sign in the Roll of Attorneys filed by petitioner Michael A. Medado (Medado). Medado graduated from the University of the Philippines with the degree of Bachelor of Laws in 19791 and passed the same year's bar examinations with a general weighted average of 82.7.2 On 7 May 1980, he took the Attorney’s Oath at the Philippine International Convention Center (PICC) together with the successful bar examinees.3 He was scheduled to sign in the Roll of Attorneys on 13 May 1980,4 but he failed to do so on his scheduled date, allegedly because he had misplaced the Notice to Sign the Roll of Attorneys5 given by the Bar Office when he went home to his province for a vacation.6 Several years later, while rummaging through his old college files, Medado found the Notice to Sign the Roll of Attorneys. It was then that he realized that he had not signed in the roll, and that what he had signed at the entrance of the PICC was probably just an attendance record.7 By the time Medado found the notice, he was already working. He stated that he was mainly doing corporate and taxation work, and that he was not actively involved in litigation practice. Thus, he operated "under the mistaken belief that since he had already taken the oath, the signing of the Roll of Attorneys was not as urgent, nor as crucial to his status as a lawyer";8 and "the matter of signing in the In 2005, when Medado attended Mandatory Continuing Legal Education (MCLE) seminars, he was required to provide his roll number in order for his MCLE compliances to be credited.10 Not having signed in the Roll of Attorneys, he was unable to provide his roll number. About seven years later, or on 6 February 2012, Medado filed the instant Petition, praying that he be allowed to sign in the Roll of Attorneys.11 The Office of the Bar Confidant (OBC) conducted a clarificatory conference on the matter on 21 September 201212and submitted a Report and Recommendation to this Court on 4 February 2013.13 The OBC recommended that the instant petition be denied for petitioner’s gross negligence, gross misconduct and utter lack of merit.14 It explained that, based on his answers during the clarificatory conference, petitioner could offer no valid justification for his negligence in signing in the Roll of Attorneys.15 After a judicious review of the records, we grant Medado’s prayer in the instant petition, subject to the payment of a fine and the imposition of a penalty equivalent to suspension from the practice of law. At the outset, we note that not allowing Medado to sign in the Roll of Attorneys would be akin to imposing upon him the ultimate penalty of disbarment, a penalty that we have reserved for the most serious ethical transgressions of members of the Bar. In this case, the records do not show that this action is warranted. For one, petitioner demonstrated good faith and good moral character when he finally filed the instant Petition to Sign in the Roll of Attorneys. We note that it was not a third party who called this Court’s attention to petitioner’s omission; rather, it was Medado himself who acknowledged his own lapse, albeit after the passage of more than 30 years. When asked by the Bar Confidant why it took him this long to file the instant petition, Medado very candidly replied: Mahirap hong i-explain yan pero, yun bang at the time, what can you say? Takot ka kung anong mangyayari sa ‘yo, you don’t know what’s gonna happen. At the same time, it’s a combination of apprehension and anxiety of what’s gonna happen. And, finally it’s the right thing to do. I have to come here … sign the roll and take the oath as necessary.16 For another, petitioner has not been subject to any action for disqualification from the practice of law,17 which is more than what we can say of other individuals who were successfully admitted as members of the Philippine Bar. For this Court, this fact demonstrates that petitioner strove to adhere to the strict requirements of the ethics of the profession, and that he has prima facie shown that he possesses the character required to be a member of the Philippine Bar. Finally, Medado appears to have been a competent and able legal practitioner, having held various positions at the Laurel Law Office,18 Petron, Petrophil Corporation, the Philippine National Oil Company, and the Energy Development Corporation.19 All these demonstrate Medado’s worth to become a full-fledged member of the Philippine Bar.1âwphi1 While the practice of law is not a right but a privilege,20 this Court will not unwarrantedly withhold this privilege from individuals who have shown mental fitness and moral fiber to withstand the rigors of the profession. That said, however, we cannot fully exculpate petitioner Medado from all liability for his years of inaction. Petitioner has been engaged in the practice of law since 1980, a period spanning more than 30 years, without having signed in the Roll of Attorneys.21 He justifies this behavior by characterizing his acts as "neither willful nor intentional but based on a mistaken belief and an honest error of judgment."22 We disagree. While an honest mistake of fact could be used to excuse a person from the legal consequences of his acts23 as it negates malice or evil motive,24 a mistake of law cannot be utilized as a lawful justification, because everyone is presumed to know the law and its consequences.25 Ignorantia factiexcusat; ignorantia legis neminem excusat. Applying these principles to the case at bar, Medado may have at first operated under an honest mistake of fact when he thought that what he had signed at the PICC entrance before the oath-taking was already the Roll of Attorneys. However, the moment he realized that what he had signed was merely an attendance record, he could no longer claim an honest mistake of fact as a valid justification. At that point, Medado should have known that he was not a full-fledged member of the Philippine Bar because of his failure to sign in the Roll of Attorneys, as it was the act of signing therein that would have made him so.26 When, in spite of this knowledge, he chose to continue practicing law without taking the necessary steps to complete all the requirements for admission to the Bar, he willfully engaged in the unauthorized practice of law. Under the Rules of Court, the unauthorized practice of law by one’s assuming to be an attorney or officer of the court, and acting as such without authority, may constitute indirect contempt of court,27 which is punishable by fine or imprisonment or both.28 Such a finding, however, is in the nature of criminal contempt29 and must be reached after the filing of charges and the conduct of hearings.30 In this case, while it appears quite clearly that petitioner committed indirect contempt of court by knowingly engaging in unauthorized practice of law, we refrain from making any finding of liability for indirect contempt, as no formal charge pertaining thereto has been filed against him. transgression of the prohibition against the unauthorized practice of law, we likewise see it fit to fine him in the amount of ₱32,000. During the one year period, petitioner is warned that he is not allowed to engage in the practice of law, and is sternly warned that doing any act that constitutes practice of law before he has signed in the Roll of Attorneys will be dealt with severely by this Court. Knowingly engaging in unauthorized practice of law likewise transgresses Canon 9 of 'the Code of Professional Responsibility, which provides: WHEREFORE, the instant Petition to Sign in the Roll of Attorneys is hereby GRANTED. Petitioner Michael A. Medado is ALLOWED to sign in the Roll of Attorneys ONE (1) YEAR after receipt of this Resolution. Petitioner is likewise ORDERED to pay a FINE of ₱32,000 for his unauthorized practice of law. During the one year period, petitioner is NOT ALLOWED to practice law, and is STERNLY WARNED that doing any act that constitutes practice of law before he has signed in the Roll of Attorneys will be dealt will be severely by this Court. CANON 9 -A lawyer shall not, directly or indirectly, assist in the unauthorized practice of law. Let a copy of this Resolution be furnished the Office of the Bar Confidant, the Integrated Bar While a reading of Canon 9 appears to merely prohibit lawyers from assisting in the unauthorized practice of law, the unauthorized practice of law by the lawyer himself is subsumed under this provision, because at the heart of Canon 9 is the lawyer's duty to prevent the unauthorized practice of law. This duty likewise applies to law students and Bar candidates. As aspiring members of the Bar, they are bound to comport themselves in accordance with the ethical standards of the legal profession. of the Philippines, and the Office of the Court Administrator for circulation to all courts in the country. Turning now to the applicable penalty, previous violations of Canon 9have warranted the penalty of suspension from the practice of law.31 As Medado is not yet a full-fledged lawyer, we cannot suspend him from the practice of law. However, we see it fit to impose upon him a penalty akin to suspension by allowing him to sign in the Roll of Attorneys one (1) year after receipt of this Resolution. For his SO ORDERED. A.C. No. 5118 September 9, 1999 (A.C. CBD No. 97-485) MARILOU vs. ATTY. DOROTHEO CALIS, respondent. SEBASTIAN, complainant, For unlawful, dishonest, immoral or deceitful conduct as well as violation of his oath as lawyer, respondent Atty. Dorotheo Calis faces disbarment. The facts of this administrative case, as found by the Commission on Bar Discipline of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP), 1 in its Report, are as follows: Complainant (Marilou Sebastian) alleged that sometime in November, 1992, she was referred to the respondent who promised to process all necessary documents required for complainant's trip to the USA for a fee of One Hundred Fifty Thousand Pesos (P150,000.00). On December 1, 1992 the complainant made a partial payment of the required fee in the amount of Twenty Thousand Pesos (P20,000.00), which was received by Ester Calis, wife of the respondent for which a receipt was issued. From the period of January 1993 to May 1994 complainant had several conferences with the respondent regarding the processing of her travel documents. To facilitate the processing, respondent demanded an additional amount of Sixty Five Thousand Pesos (P65,000.00) and prevailed upon complainant to resign from her job as stenographer with the Commission on Human Rights. On June 20, 1994, to expedite the processing of her travel documents complainant issued Planters Development Bank Check No. 12026524 in the amount of Sixty Five Thousand Pesos (P65,000.00) in favor of Atty. D. Calis who issued a receipt. After receipt of said amount, respondent furnished the complainant copies of Supplemental to U.S. Nonimmigrant Visa Application (Of. 156) and a list of questions which would be asked during interviews. When complainant inquired about her passport, Atty. Calis informed the former that she will be assuming the name Lizette P. Ferrer married to Roberto Ferrer, employed as sales manager of Matiao Marketing, Inc. The complainant was furnished documents to support her assumed identity.1âwphi1.nêt Realizing that she will be travelling with spurious documents, the complainant demanded the return of her money, however she was assured by respondent that there was nothing to worry about for he has been engaged in the business for quite sometime; with the promise that her money will be refunded if something goes wrong. Weeks before her departure respondent demanded for the payment of the required fee which was paid by complainant, but the corresponding receipt was not given to her. When complainant demanded for her passport, respondent assured the complainant that it will be given to her on her departure which was scheduled on September 6, 1994. On said date complainant was given her passport and visa issued in the name of Lizette P. Ferrer. Complainant left together with Jennyfer Belo and a certain Maribel who were also recruits of the respondent. Upon arrival at the Singapore International Airport, complainant together with Jennyfer Belo and Maribel were apprehended by the Singapore Airport Officials for carrying spurious travel documents; Complainant contacted the respondent through overseas telephone call and informed him of by her predicament. From September 6 to 9, 1994, complainant was detained at Changi Prisons in Singapore. On September 9, 1994 the complainant was deported back to the Philippines and respondent fetched her from the airport and brought her to his residence at 872-A Tres Marias Street, Sampaloc, Manila. Respondent took complainant's passport with a promise that he will secure new travel documents for complainant. Since complainant opted not to pursue with her travel, she demanded for the return of her money in the amount of One Hundred Fifty Thousand Pesos (P150,000.00). On June 4, 1996, June 18 and July 5, 1996 respondent made partial refunds of P15,000.00; P6,000.00; and P5,000.00. On December 19, 1996 the complainant through counsel, sent a demand letter to respondent for the refund of a remaining balance of One Hundred Fourteen Thousand Pesos (P114,000.00) which was ignored by the respondent. Sometime in March 1997 the complainant went to see the respondent, however his wife informed her that the respondent was in Cebu attending to business matters. In May 1997 the complainant again tried to see the respondent however she found out that the respondent had transferred to an unknown residence apparently with intentions to evade responsibility. Attached to the complaint are the photocopies of receipts for the amount paid by complainant, applications for U.S.A. Visa, questions and answers asked during interviews; receipts acknowledging partial refunds of fees paid by the complainant together with demand letter for the remaining balance of One Hundred Fourteen Thousand Pesos (P114,000.00); which was received by the respondent. 2 Despite several notices sent to the respondent requiring an answer to or comment on the complaint, there was no response. Respondent likewise failed to attend the scheduled hearings of the case. No appearance whatsoever was made by the respondent. 3 As a result of the inexplicable failure, if not obdurate refusal of the respondent to comply with the orders of the Commission, the investigation against him proceeded ex parte. On September 24, 1998, the Commission on Bar Discipline issued its Report on the case, finding that: It appears that the services of the respondent was engaged for the purpose of securing a visa for a U.S.A. travel of complainant. There was no mention of job placement or employment abroad, hence it is not correct to say that the respondent engaged in illegal recruitment. The alleged proposal of the respondent to secure the U.S.A. visa for the complainant under an assumed name was accepted by the complainant which negates deceit on the part of the respondent. Noted likewise is the partial refunds made by the respondent of the fees paid by the complainant. However, the transfer of residence without a forwarding address indicates his attempt to escape responsibility. In the light of the foregoing, we find that the respondent is guilty of gross misconduct for violating Canon 1 Rule 1.01 of the Code of Professional Responsibility which provides that a lawyer shall not engage in unlawful, dishonest, immoral or deceitful conduct. WHEREFORE, it is respectfully recommended that ATTY. DOROTHEO CALIS be SUSPENDED as a member of the bar until he fully refunds the fees paid to him by complainant and comply with the order of the Commission on Bar Discipline pursuant to Rule 139-B, Sec. 6, of the Rules of Court. 4 Pursuant to Section 12, Rule 139-B of the Rules of Court, this administrative case was elevated to the IBP Board of Governors for review. The Board in a Resolution 5 dated December 4, 1998 resolved to adopt and approve with amendment the recommendation of the Commission. The Resolution of the Board states: RESOLVED to ADOPT and APPROVE, as it is hereby ADOPTED and APPROVED, the Report and Recommendation of the Investigating Commissioner in the above-entitled case, herein made part of this Resolution/Decision as Annex "A"; and, finding the recommendation fully supported by the evidence on record and the applicable laws and rules, with an amendment that Respondent Atty. Dorotheo Calis be DISBARRED for having been found guilty of Gross Misconduct for engaging in unlawful, dishonest, immoral or deceitful conduct. We are now called upon to evaluate, for final action, the IBP recommendation contained in its Resolution dated December 4, 1998, with its supporting report. After examination and careful consideration of the records in this case, we find the Resolution passed by the Board of Governors of the IBP in order. We agree with the finding of the Commission that the charge of illegal recruitment was not established because complainant failed to substantiate her allegation on the matter. In fact she did not mention any particular job or employment promised to her by the respondent. The only service of the respondent mentioned by the complainant was that of securing a visa for the United States. We likewise concur with the IBP Board of Governors in its Resolution, that herein respondent is guilty of gross misconduct by engaging in unlawful, dishonest, immoral or deceitful conduct contrary to Canon I, Rule 101 of the Code of Professional Responsibility. Respondent deceived the complainant by assuring her that he could give her visa and travel documents; that despite spurious documents nothing untoward would happen; that he guarantees her arrival in the USA and even promised to refund her the fees and expenses already paid, in case something went wrong. All for material gain. Deception and other fraudulent acts by a lawyer are disgraceful and dishonorable. They reveal moral flaws in a lawyer. They are unacceptable practices. A lawyer's relationship with others should be characterized by the highest degree of good faith, fairness and candor. This is the essence of the lawyer's oath. The lawyer's oath is not mere facile words, drift and hollow, but a sacred trust that must be upheld and keep inviolable. 6 The nature of the office of an attorney requires that he should be a person of good moral character. 7 This requisite is not only a condition precedent to admission to the practice of law, its continued possession is also essential for remaining in the practice of law. 8 We have sternly warned that any gross misconduct of a lawyer, whether in his professional or private capacity, puts his moral character in serious doubt as a member of the Bar, and renders him unfit to continue in the practice of law. 9 It is dismaying to note how respondent so cavalierly jeopardized the life and liberty of complainant when he made her travel with spurious documents. How often have victims of unscrupulous travel agents and illegal recruiters been imprisoned in foreign lands because they were provided fake travel documents? Respondent totally disregarded the personal safety of the complainant when he sent her abroad on false assurances. Not only are respondent's acts illegal, they are also detestable from the moral point of view. His utter lack of moral qualms and scruples is a real threat to the Bar and the administration of justice. The practice of law is not a right but a privilege bestowed by the State on those who show that they possess, and continue to possess, the qualifications required by law for the conferment of such privilege. 10 We must stress that membership in the bar is a privilege burdened with conditions. A lawyer has the privilege to practice law only during good behavior. He can be deprived of his license for misconduct ascertained and declared by judgment of the court after giving him the opportunity to be heard. 11 Here, it is worth noting that the adamant refusal of respondent to comply with the orders of the IBP and his total disregard of the summons issued by the IBP are contemptuous acts reflective of unprofessional conduct. Thus, we find no hesitation in removing respondent Dorotheo Calis from the Roll of Attorneys for his unethical, unscrupulous and unconscionable conduct toward complainant. Lastly, the grant in favor of the complainant for the recovery of the P114,000.00 she paid the respondent is in order. 12 Respondent not only unjustifiably refused to return the complainant's money upon demand, but he stubbornly persisted in holding on to it, unmindful of the hardship and humiliation suffered by the complainant. WHEREFORE, respondent Dorotheo Calis is hereby DISBARRED and his name is ordered stricken from the Roll of Attorneys. Let a copy of this Decision be FURNISHED to the IBP and the Bar Confidant to be spread on the personal records of respondent. Respondent is likewise ordered to pay to the complainant immediately the amount of One Hundred Fourteen Thousand (P114,000.00) Pesos representing the amount he collected from her.1âwphi1.nêt SO ORDERED. AC No. 99-634 June 10, 2002 DOMINADOR P. vs. ATTY. ALBERTO C. MAGULTA, respondent. Alberto C. Magulta, copy of the Receipt attached as Annex B, upon the instruction that I needed the case filed immediately; BURBE, complainant, "That a week later, I was informed by Atty. Alberto C. Magulta that the complaint had already been filed in court, and that I should receive notice of its progress; The Case Before us is a Complaint for the disbarment or suspension or any other disciplinary action against Atty. Alberto C. Magulta. Filed by Dominador P. Burbe with the Commission on Bar Discipline of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) on June 14, 1999, the Complaint is accompanied by a Sworn Statement alleging the following: "x x x xxx xxx "That in connection with my business, I was introduced to Atty. Alberto C. Magulta, sometime in September, 1998, in his office at the Respicio, Magulta and Adan Law Offices at 21-B Otero Building, Juan de la Cruz St., Davao City, who agreed to legally represent me in a money claim and possible civil case against certain parties for breach of contract; "That consequent to such agreement, Atty. Alberto C. Magulta prepared for me the demand letter and some other legal papers, for which services I have accordingly paid; inasmuch, however, that I failed to secure a settlement of the dispute, Atty. Magulta suggested that I file the necessary complaint, which he subsequently drafted, copy of which is attached as Annex A, the filing fee whereof will require the amount of Twenty Five Thousand Pesos (P25,000.00); "That having the need to legally recover from the parties to be sued I, on January 4, 1999, deposited the amount of P25,000.00 to Atty. "That in the months that followed, I waited for such notice from the court or from Atty. Magulta but there seemed to be no progress in my case, such that I frequented his office to inquire, and he would repeatedly tell me just to wait; "That I had grown impatient on the case, considering that I am told to wait [every time] I asked; and in my last visit to Atty. Magulta last May 25, 1999, he said that the court personnel had not yet acted on my case and, for my satisfaction, he even brought me to the Hall of Justice Building at Ecoland, Davao City, at about 4:00 p.m., where he left me at the Office of the City Prosecutor at the ground floor of the building and told to wait while he personally follows up the processes with the Clerk of Court; whereupon, within the hour, he came back and told me that the Clerk of Court was absent on that day; "That sensing I was being given the run-around by Atty. Magulta, I decided to go to the Office of the Clerk of Court with my draft of Atty. Magulta's complaint to personally verify the progress of my case, and there told that there was no record at all of a case filed by Atty. Alberto C. Magulta on my behalf, copy of the Certification dated May 27, 1999, attached as Annex C; "That feeling disgusted by the way I was lied to and treated, I confronted Atty. Alberto C. Magulta at his office the following day, May 28, 1999, where he continued to lie to with the excuse that the delay was being caused by the court personnel, and only when shown the certification did he admit that he has not at all filed the complaint because he had spent the money for the filing fee for his own purpose; and to appease my feelings, he offered to reimburse me by issuing two (2) checks, postdated June 1 and June 5, 1999, in the amounts of P12,000.00 and P8,000.00, respectively, copies of which are attached as Annexes D and E; "That for the inconvenience, treatment and deception I was made to suffer, I wish to complain Atty. Alberto C. Magulta for misrepresentation, dishonesty and oppressive conduct;" xxx xxx x x x.1 On August 6, 1999, pursuant to the July 22, 1999 Order of the IBP Commission on Bar Discipline,2 respondent filed his 3 Answer vehemently denying the allegations of complainant "for being totally outrageous and baseless." The latter had allegedly been introduced as a kumpadre of one of the former's law partners. After their meeting, complainant requested him to draft a demand letter against Regwill Industries, Inc. -- a service for which the former never paid. After Mr. Said Sayre, one of the business partners of complainant, replied to this letter, the latter requested that another demand letter -- this time addressed to the former -- be drafted by respondent, who reluctantly agreed to do so. Without informing the lawyer, complainant asked the process server of the former's law office to deliver the letter to the addressee. Aside from attending to the Regwill case which had required a threehour meeting, respondent drafted a complaint (which was only for the purpose of compelling the owner to settle the case) and prepared a compromise agreement. He was also requested by complainant to do the following: 1. Write a demand letter addressed to Mr. Nelson Tan 2. Write a demand letter addressed to ALC Corporation 3. Draft a complaint against ALC Corporation 4. Research on the Mandaue City property claimed by complainant's wife All of these respondent did, but he was never paid for his services by complainant. Respondent likewise said that without telling him why, complainant later on withdrew all the files pertinent to the Regwill case. However, when no settlement was reached, the latter instructed him to draft a complaint for breach of contract. Respondent, whose services had never been paid by complainant until this time, told the latter about his acceptance and legal fees. When told that these fees amounted to P187,742 because the Regwill claim was almost P4 million, complainant promised to pay on installment basis. On January 4, 1999, complainant gave the amount of P25,000 to respondent's secretary and told her that it was for the filing fee of the Regwill case. When informed of the payment, the lawyer immediately called the attention of complainant, informing the latter of the need to pay the acceptance and filing fees before the complaint could be filed. Complainant was told that the amount he had paid was a deposit for the acceptance fee, and that he should give the filing fee later. Sometime in February 1999, complainant told respondent to suspend for the meantime the filing of the complaint because the former might be paid by another company, the First Oriental Property Ventures, Inc., which had offered to buy a parcel of land owned by Regwill Industries. The negotiations went on for two months, but the parties never arrived at any agreement. Sometime in May 1999, complainant again relayed to respondent his interest in filing the complaint. Respondent reminded him once more of the acceptance fee. In response, complainant proposed that the complaint be filed first before payment of respondent's acceptance and legal fees. When respondent refused, complainant demanded the return of the P25,000. The lawyer returned the amount using his own personal checks because their law office was undergoing extensive renovation at the time, and their office personnel were not reporting regularly. Respondent's checks were accepted and encashed by complainant. Respondent averred that he never inconvenienced, mistreated or deceived complainant, and if anyone had been shortchanged by the undesirable events, it was he. The IBP's Recommendation In its Report and Recommendation dated March 8, 2000, the Commission on Bar Discipline of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) opined as follows: "x x x [I]t is evident that the P25,000 deposited by complainant with the Respicio Law Office was for the filing fees of the Regwill complaint. With complainant's deposit of the filing fees for the Regwill complaint, a corresponding obligation on the part of respondent was created and that was to file the Regwill complaint within the time frame contemplated by his client, the complainant. The failure of respondent to fulfill this obligation due to his misuse of the filing fees deposited by complainant, and his attempts to cover up this misuse of funds of the client, which caused complainant additional damage and prejudice, constitutes highly dishonest conduct on his part, unbecoming a member of the law profession. The subsequent reimbursement by the respondent of part of the money deposited by complainant for filing fees, does not exculpate the respondent for his misappropriation of said funds. Thus, to impress upon the respondent the gravity of his offense, it is recommended that respondent be suspended from the practice of law for a period of one (1) year."4 The Court's Ruling We agree with the Commission's recommendation. Main Misappropriation of Client's Funds Issue: Central to this case are the following alleged acts of respondent lawyer: (a) his non-filing of the Complaint on behalf of his client and (b) his appropriation for himself of the money given for the filing fee. Respondent claims that complainant did not give him the filing fee for the Regwill complaint; hence, the former's failure to file the complaint in court. Also, respondent alleges that the amount delivered by complainant to his office on January 4, 1999 was for attorney's fees and not for the filing fee. We are not persuaded. Lawyers must exert their best efforts and ability in the prosecution or the defense of the client's cause. They who perform that duty with diligence and candor not only protect the interests of the client, but also serve the ends of justice. They do honor to the bar and help maintain the respect of the community for the legal profession.5 Members of the bar must do nothing that may tend to lessen in any degree the confidence of the public in the fidelity, the honesty, and integrity of the profession.6 Respondent wants this Court to believe that no lawyer-client relationship existed between him and complainant, because the latter never paid him for services rendered. The former adds that he only drafted the said documents as a personal favor for the kumpadre of one of his partners. owe entire devotion to the interest of the client, warm zeal in the maintenance and the defense of the client's rights, and the exertion of their utmost learning and abilities to the end that nothing be taken or withheld from the client, save by the rules of law legally applied.10 We disagree. A lawyer-client relationship was established from the very first moment complainant asked respondent for legal advice regarding the former's business. To constitute professional employment, it is not essential that the client employed the attorney professionally on any previous occasion. It is not necessary that any retainer be paid, promised, or charged; neither is it material that the attorney consulted did not afterward handle the case for which his service had been sought. Similarly unconvincing is the explanation of respondent that the receipt issued by his office to complainant on January 4, 1999 was erroneous. The IBP Report correctly noted that it was quite incredible for the office personnel of a law firm to be prevailed upon by a client to issue a receipt erroneously indicating payment for something else. Moreover, upon discovering the "mistake" -- if indeed it was one -respondent should have immediately taken steps to correct the error. He should have lost no time in calling complainant's attention to the matter and should have issued another receipt indicating the correct purpose of the payment. If a person, in respect to business affairs or troubles of any kind, consults a lawyer with a view to obtaining professional advice or assistance, and the attorney voluntarily permits or acquiesces with the consultation, then the professional employment is established.7 The Practice Profession, Not a Business Likewise, a lawyer-client relationship exists notwithstanding the close personal relationship between the lawyer and the complainant or the nonpayment of the former's fees.8 Hence, despite the fact that complainant was kumpadre of a law partner of respondent, and that respondent dispensed legal advice to complainant as a personal favor to the kumpadre, the lawyer was duty-bound to file the complaint he had agreed to prepare -- and had actually prepared -- at the soonest possible time, in order to protect the client's interest. Rule 18.03 of the Code of Professional Responsibility provides that lawyers should not neglect legal matters entrusted to them. This Court has likewise constantly held that once lawyers agree to take up the cause of a client, they owe fidelity to such cause and must always be mindful of the trust and confidence reposed in them.9 They of Law -- a In this day and age, members of the bar often forget that the practice of law is a profession and not a business.11Lawyering is not primarily meant to be a money-making venture, and law advocacy is not a capital that necessarily yields profits.12 The gaining of a livelihood is not a professional but a secondary consideration.13 Duty to public service and to the administration of justice should be the primary consideration of lawyers, who must subordinate their personal interests or what they owe to themselves. The practice of law is a noble calling in which emolument is a byproduct, and the highest eminence may be attained without making much money.14 In failing to apply to the filing fee the amount given by complainant - as evidenced by the receipt issued by the law office of respondent - the latter also violated the rule that lawyers must be scrupulously careful in handling money entrusted to them in their professional capacity.15 Rule 16.01 of the Code of Professional Responsibility states that lawyers shall hold in trust all moneys of their clients and properties that may come into their possession. year, effective upon his receipt of this Decision. Let copies be furnished all courts as well as the Office of the Bar Confidant, which is instructed to include a copy in respondent's file. Lawyers who convert the funds entrusted to them are in gross violation of professional ethics and are guilty of betrayal of public confidence in the legal profession.16 It may be true that they have a lien upon the client's funds, documents and other papers that have lawfully come into their possession; that they may retain them until their lawful fees and disbursements have been paid; and that they may apply such funds to the satisfaction of such fees and disbursements. However, these considerations do not relieve them of their duty to promptly account for the moneys they received. Their failure to do so constitutes professional misconduct.17 In any event, they must still exert all effort to protect their client's interest within the bounds of law. SO ORDERED. If much is demanded from an attorney, it is because the entrusted privilege to practice law carries with it correlative duties not only to the client but also to the court, to the bar, and to the public.18 Respondent fell short of this standard when he converted into his legal fees the filing fee entrusted to him by his client and thus failed to file the complaint promptly. The fact that the former returned the amount does not exculpate him from his breach of duty. On the other hand, we do not agree with complainant's plea to disbar respondent from the practice of law. The power to disbar must be exercised with great caution. Only in a clear case of misconduct that seriously affects the standing and the character of the bar will disbarment be imposed as a penalty.19 WHEREFORE, Atty. Alberto C. Magulta is found guilty of violating Rules 16.01 and 18.03 of the Code of Professional Responsibility and is hereby SUSPENDED from the practice of law for a period of one (1) A.C. No. 6387 GABINO V. TOLENTINO and FLORDELIZA C. TOLENTINO, Complainants vs. ATTY. HENRY B. SO and ATTY. FERDINAND L.ANCHETA, Respondents This resolves a disbarment case against respondent Atty. Henry B. So for neglect in handling a case, and respondent Atty. Ferdinand L. Ancheta for extorting ₱200,000.00 from a client. Complainant Flordeliza C. Tolentino was the defendant in Civil Case No. SC-2267 entitled "Benjamin Caballes v. Flordeliza Caballes," a case involving recovery of possession of a parcel of land.1 On June 24, 1991, Branch 26 of the Regional Trial Court of Sta. Cruz, Laguna, rendered the Decision2 against complainant Flordeliza ordering her to vacate the land. The case was appealed3 to the Court of Appeals through complainant Flordeliza's counsel, Atty. Edilberto U. Coronado (Atty. Coronado). While the appeal was pending, Atty. Coronado was replaced by Atty. Henry B. So (Atty. So), a lawyer of the Bureau of Agrarian Legal Assistance of the Department of Agrarian Reform.4 Complainants Flordeliza and Gabino V. Tolentino, her husband, afterwards learned that the Court of Appeals affirmed5 the Regional Trial Court Decision against complainant Flordeliza. Complainants contend that Atty. So did not inform them nor take the necessary action to elevate the case to this Court.6 Thus, they were compelled to secure the legal services of Atty. Ferdinand L. Ancheta (Atty. Ancheta), whom they paid ₱30,000.00 as acceptance fee.7 Atty. Ancheta allegedly promised them that there was still a remedy against the adverse Court of Appeals Decision, and that he would file a "motion to reopen appeal case."8 Atty. Ancheta also inveigled them to part with the amount of ₱200,000.00 purportedly to be used for making arrangements with tlie Justices of the Court of Appeals before whom their case was pending.9 Initially, complainants did not agree to Atty. Ancheta's proposal because they did not have the money and it was against the law.10 However, they eventually acceded when Atty. Ancheta told them that it was the only recourse they had to obtain a favorable judgment.11 Hence, in January 2003, they deposited ₱200,000.00 to Atty. Ancheta's Bank Account No. 1221275656 with the United Coconut Planters Bank.12 Complainants were surprised to learn that no "motion to reopen case" had been filed,13 and the Court of Appeals Decision had become final and executory.14 Hence, complainants sought to recover the amount of ₱200,000.00 from Atty. Ancheta. Through a letter dated September 10, 200315 by their new counsel, complainants demanded for the return of the ₱200,000.00. However, Atty. Ancheta did not heed their demand despite receipt of the letter. On May 17, 2004, complainants filed their Sinumpaang Sakdal16 praying for the disbarment of Atty. So for neglect in handling complainant Flordeliza's case, and Atty. Ancheta for defrauding them of the amount of ₱200,000.00. Atty. So counters that he was no longer connected with the Bureau of Agrarian Legal Assistance of the Department of Agrarian Reform when the Court of Appeals Decision was promulgated on July 16, 2001.17 He alleges that he worked at the Bureau from 1989 to 1997, and that he resigned to prepare for the elections in his hometown in Western Samar.18 It was a procedure in the Bureau that once a handling lawyer resigns or retires, his or her cases are reassigned to other lawyers of the Bureau.19 Atty. Ancheta did not file a comment despite due notice. Hence, in this Court's Resolution dated February 23, 2011,20 he was deemed to have waived his right to file a comment. This Court referred the case to the Integrated Bar of the Philippines for investigation, report, and recommendation.21 On June 8, 2011, the Commission on Bar Discipline of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines directed the parties to appear for mandatory conference at 10:00 a.m. on July 6, 2011.22 However, on July 6, 2011, only Atty. So appeared.23 Since there was no showing on record that complainants and Atty. Ancheta were notified, the mandatory conference was reset to August 10, 2011 at 10:00 a.m.24 In the August 10, 2011 mandatory conference, complainant Flordeliza was represented by her daughter, Arlyn Tolentino, together with counsel, Atty. Restituto Mendoza.25 Arlyn Tolentino informed the Commission that complainant Gabino V. Tolentino had already died.26 Respondents did not appear despite due notice.27 Hence, the mandatory conference was terminated, and the parties were directed to submit their respective verified position papers within a non-extendible period of 10 days from notice. After, the case would be submitted for report and recommendation.28 On September 19, 2011, complainant Flordeliza filed as her position paper, a Motion for Adoption of the Pleadings and their Annexes in this Case,29 including the relevant documents30 in Criminal Case No. SC-1191 (for estafa) against Atty. Ancheta, which she filed. Atty. So filed his Position Paper31 on September 15, 2011. Atty. Ancheta did not file any position paper.32 The Commission on Bar Discipline recommended33 that Atty. So be absolved of the charge against him for insufficiency of evidence.34 As to Atty. Ancheta, the Commission found him guilty of serious misconduct and deceit and recommended his disbarment.35 In the Resolution36 dated December 14, 2014, the Integrated Bar of the Philippines Board of Governors adopted and approved the findings and recommendations of the Investigating Commissioner. On January 11, 2016, the Board of Governors transmitted its Resolution to this Court for final action, pursuant to Rule 139-B of the Rules of Court.37 This Court accepts and adopts the findings of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines Board of Governors. I The Integrated Bar of the Philippines correctly absolved Atty. So of the charge of negligence in the performance of his duties as counsel of complainant Flordeliza. Complainants fault Atty. So for failing to inform them about the Court of Appeals Decision and for not taking the necessary steps to elevate their case to this Court.38 However, it is undisputed that Atty. So was no longer employed at the Bureau of Agrarian Legal Assistance when the Court of Appeals Decision was rendered on July 16, 2001. Atty. So had resigned in 1997, four (4) years before the Decision was promulgated.39 Atty. So handled the appeal of complainant Flordeliza in his capacity as a government-employed legal officer of the Bureau of Agrarian Legal Assistance of the Department of Agrarian Reform. In his Notice of Appearance40 dated August 11, 1993 and Motion to Admit Additional Evidence41 dated November 22, 1993 filed before the Court of Appeals, Atty. So affixed his signature under the representation of the Bureau of Agrarian Legal Assistance. Atty. So's appearance for complainant Flordeliza may be likened to that of a lawyer assigned to handle a case for a private law firm's client. If the counsel resigns, _the firm is simply bound to provide a replacement.42 Similarly, upon Atty. So's resignation, the Director of the Bureau merely reassigned his case assignment to other lawyers in the Bureau even without complainants' consent. It would have been prudent for Atty. So to have informed complainants about his resignation and the eventual reassignment of their case to another lawyer, although this was not required. Still, Atty. So's omission is not of such gravity that would warrant his disbarment or suspension. The serious consequences of disbarment or suspension should follow only where there is a clear preponderance of evidence of the respondent's misconduct affecting his standing and moral character as an officer of the court and member of the bar.43 On the other hand, complainants were not entirely blameless. Had complainants been indeed vigilant in protecting their rights, they should have followed up on the status of their appeal; thus, they would have been informed of Atty. So's resignation. Atty. So resigned four (4) years before the Court of Appeals Decision was promulgated.44 Thus, complainants had ample time to engage the services of a new lawyer to safeguard their interests if they chose to do so. A party cannot blame his or her counsel for negligence when he or she is guilty of neglect.45 II The same conclusion cannot be made with regards Atty. Ancheta. We agree with the Integrated Bar of the Philippines' recommendation that he should be disbarred. Atty. Ancheta's repeated failure to comply with several of this Court's Resolutions requiring him to comment on the complaint lends credence to complainants' allegations. It manifests his tacit admission. Hence, we resolve this case on the basis of complainants' Sinumpaang Sakdal and its Annexes. It was established by the evidence on record that (1) Atty. Ancheta received the acceptance fee of ₱30,000.00 on December 9, 2002;46 and (2) complainants deposited on January 17, 200347 the amount of ₱200,000.00 to Atty. Ancheta's bank account. Atty. Ancheta made false promises to complainants that something could still be done with complainant Flordeliza's case despite the Court of Appeals Decision having already attained finality on September 22, 2001.48 Worse, he proposed bribing the Justices of the Court of Appeals in order to solve their legal dilemma. Atty. Ancheta should have very well known that a decision that has attained finality is no longer open for reversal and should be respected.49 A lawyer's duty to assist in the speedy administration of justice50 demands recognition that at a definite time, issues must be laid to rest and litigation ended.51 As such, Ancheta should have advised complainants to accept the judgment of the Court of Appeals and accord respect to the just claim of the opposite party. He should have tempered his clients' propensity to litigate and save them from additional expense in pursuing their contemplated action. Instead, he gave them confident assurances that the case could still be reopened and even furnished them a copy of his prepared "motion to reopen case." Despite his representation that he would file the motion, however, he did not do so.52 Atty. Ancheta's deceit and evasion of duty is manifest. He accepted the case though he knew the futility of an appeal. Despite receipt of the ₱30,000.00 acceptance fee, he did not act on his client's case. Moreover, he prevailed upon complainants to give him ₱200,000.00 purportedly to be used to bribe the Justices of the Court of Appeals in order to secure a favorable ruling, palpably showing that he himself was unconvinced of the merits of the case. "A lawyer shall not, for any corrupt motive or interest, encourage any suit or proceeding or delay any man's cause."53Atty. Ancheta's misconduct betrays his lack of appreciation that the practice of law is a profession, not a moneymaking trade.54 As a servant of the law, Atty. Ancheta's primary duty was to obey the laws and promote respect for the law and legal processes.55Corollary to this duty is his obligation to abstain from dishonest or deceitful conduct,56 as well as from "activities aimed at defiance of the law or at lessening confidence in the legal system."57 Atty. Ancheta's advice involving corruption of judicial officers tramps the integrity and dignity of the legal profession and the judicial system and adversely reflects on his fitness to practice law. Complainants eventually found out about his duplicity and demanded for the return of their money.58 Still, Atty. Ancheta did not return the ₱200,000.00 and the ₱30,000.00 despite his failure to render any legal service to his clients..59 Atty. Ancheta breached the following duties embodied in the Code of Professional Responsibility: CANON 7 - A LA WYER SHALL AT ALL TIMES UPHOLD THE INTEGRITY AND DIGNITY OF THE LEGAL PROFESSION AND SUPPORT THE ACTIVITIES OF THE INTEGRATED BAR. .... CANON 15 -A LAWYER SHALL OBSERVE CANDOR, FAIRNESS AND LOYALTY IN ALL HIS DEALINGS AND TRANSACTIONS WITH HIS CLIENTS. .... Rule 15.05. - A lawyer, when advising his client, shall give a candid and honest opinion on the merits and probable results of the client's case, neither overstating nor understating the prospects of the case. Rule 15.06. - A lawyer shall not state or imply that he is able to influence any public official, tribunal or legislative body. Rule 15.07. - A lawyer shall impress upon his client compliance with the laws and the principles of fairness. .... CANON 16 -A LAWYER SHALL HOLD IN TRUST ALL MONEYS AND PROPERTIES OF HIS CLIENT THAT MAY COME INTO HIS POSSESSION. Rule 16.01. - A lawyer shall account for all money or property collected or received for or from the client. .... Rule 16.03. - A lawyer shall deliver the funds and property of his client when due or upon demand .... .... CANON 17 - A LAWYER OWES FIDELITY TO THE CAUSE OF HIS CLIENT AND HE SHALL BE MINDFUL OF THE TRUST AND CONFIDENCE REPOSED IN HIM. CANON 18 - A LAWYER SHALL SERVE HIS CLIENT WITH COMPETENCE AND DILIGENCE. .... Rule 18.03. - A lawyer shall not neglect a legal matter entrusted to him, and his negligence in connection therewith shall render him liable. A lawyer "must at no time be wanting in probity and moral fiber, which are not only conditions precedent to his entrance to the Bar but are likewise essential demands for his continued membership therein."60 Atty. Ancheta's deceit in dealing with his clients constitutes gross professional misconduct61 and violates his oath, thus justifying his disbarment under Rule 138, Section 2762 of the Rules of Court. Furthermore, his failure to heed the following Resolutions of the Court despite notice aggravates his misconduct: (1) Resolution63 dated June 21, 2004, requiring him to comment on the complaint; 64 (2) Resolution dated October 16, 2006, directing him to show cause why he should not be disciplinarily dealt with or held in contempt for failure to comply with the June 21, 2004 Resolution; (3) Resolution65 dated January 21, 2009, imposing upon him the penalty of ₱l,000.00 for failure to comply with the June 21, 2004 and October 16, 2006 Resolutions; (4) Resolution66 dated January 27, 2010, imposing an additional fine of ₱2,000.00 or a penalty of imprisonment of 10 days for failure to comply with the January 21, 2009 Resolution; and (5) Resolution67 dated January 12, 2011, ordering his arrest and directing the National Bureau of Investigation to arrest and detain him for five (5) days and until he complied with the previous Resolutions. Atty. Ancheta's cavalier attitude in repeatedly ignoring the orders of this Court constitutes utter disrespect of the judicial institution. His conduct shows a high degree of irresponsibility and betrays a recalcitrant flaw in his character. Indeed, his continued indifference to this Court's orders constitutes willful disobedience of the lawful orders of this Court, which, under Rule 138, Section 2768 of the Rules of Court, is in itself a sufficient cause for suspension or disbarment. The maintenance of a high standard of legal proficiency, honesty, and fair dealing69 is a prerequisite to making the bar an effective instrument in the proper administration of justice.70 Any member, therefore, who fails to live up to the exacting standards of integrity and morality exposes himself or herself to administrative liability.71 Atty. Ancheta's violations show that he is unfit to discharge the duties of a member of the legal profession.1âwphi1 Hence, he should be disbarred.72 WHEREFORE, the complaint against respondent Atty. Henry B. So is DISMISSED for insufficiency of evidence. On the other hand, this Court finds respondent Atty. Ferdinand L. Ancheta GUILTY of gross misconduct in violation of the Lawyer's Oath and the Code of Professional Responsibility and hereby DISBARS him from the practice of law. The Office of the Bar Confidant is DIRECTED to remove the name of Ferdinand L. Ancheta from the Roll of Attorneys. Respondent Ancheta is ORDERED to return to complainants Gabino V. Tolentino and Flordeliza C. Tolentino, within 30 days from receipt of this Resolution, the total amount of ₱230,000.00, with legal interest at 12% per annum from the date of demand on September 10, 2003 to June 30, 2013, and at 6% per annum from July 1, 2013 until full payment. Respondent Ancheta is further DIRECTED to submit to this Court proof of payment of the amount within 10 days from payment. Let copies of this Resolution be furnished to the Office of the Bar Confidant, the Integrated Bar of the Philippines, and the Office of the Court Administrator for dissemination to all courts in the country. This Resolution takes effect immediately. SO ORDERED. A.C. No. 11316 PATRICK A. CARONAN, Complainant vs. RICHARD A. CARONAN a.k.a. "ATTY. PATRICK A. CARONAN," Respondent The Facts Complainant and respondent are siblings born to Porferio2 R. Caronan, Jr. and Norma A. Caronan. Respondent is the older of the two, having been born on February 7, 1975, while complainant was born on August 5, 1976.3 Both of them completed their secondary education at the Makati High School where complainant graduated in 19934 and respondent in 1991.5 Upon his graduation, complainant enrolled at the University of Makati where he obtained a degree in Business Administration in 1997.6 He started working thereafter as a Sales Associate for Philippine Seven Corporation (PSC), the operator of 7-11 Convenience Stores.7 In 2001, he married Myrna G. Tagpis with whom he has two (2) daughters.8 Through the years, complainant rose from the ranks until, in 2009, he was promoted as a Store Manager of the 7-11 Store in Muntinlupa.9 Meanwhile, upon graduating from high school, respondent enrolled at the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila (PLM), where he stayed for one (1) year before transferring to the Philippine Military Academy (PMA) in 1992.10 In 1993, he was discharged from the PMA and focused on helping their father in the family's car rental business. In 1997, he moved to Nueva Vizcaya with his wife, Rosana, and their three (3) children.11 Since then, respondent never went back to school to earn a college degree.12 In 1999, during a visit to his family in Metro Manila, respondent told complainant that the former had enrolled in a law school in Nueva Vizcaya.13 Subsequently, in 2004, their mother informed complainant that respondent passed the Bar Examinations and that he used complainant's name and college records from the University of Makati to enroll at St. Mary's University's College of Law in Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya and take the Bar Examinations.14 Complainant brushed these aside as he did not anticipate any adverse consequences to him.15 In 2006, complainant was able to confirm respondent's use of his name and identity when he saw the name "Patrick A. Caronan" on the Certificate of Admission to the Bar displayed at the latter's office in Taguig City.16 Nevertheless, complainant did not confront respondent about it since he was pre-occupied with his job and had a family to support.17 Sometime in May 2009, however, after his promotion as Store Manager, complainant was ordered to report to the head office of PSC in Mandaluyong City where, upon arrival, he was informed that the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) was requesting his presence at its office in Taft Avenue, Manila, in relation to an investigation involving respondent who, at that point, was using the name "Atty. Patrick A. Caronan."18 Accordingly, on May 18, 2009, complainant appeared before the Anti-Fraud and Computer Crimes Division of the NBI where he was interviewed and asked to identify documents including: (1) his and respondent's high school records; (2) his transcript of records from the University of Makati; (3) Land Transportation Office's records showing his and respondent's driver's licenses; (4) records from St. Mary's University showing that complainant's transcript of records from the University of Makati and his Birth Certificate were submitted to St. Mary's University's College of Law; and (5) Alumni Book of St. Mary's University showing respondent's photograph under the name "Patrick A. Caronan."19 Complainant later learned that the reason why he was invited by the NBI was because of respondent's involvement in a case for qualified theft and estafa filed by Mr. Joseph G. Agtarap (Agtarap), who was one of the principal sponsors at respondent's wedding.20 Realizing that respondent had been using his name to perpetrate crimes and commit unlawful activities, complainant took it upon himself to inform other people that he is the real "Patrick A. Caronan" and that respondent's real name is Richard A. Caronan.21 However, problems relating to respondent's use of the name "Atty. Patrick A. Caronan" continued to hound him. In July 2013, PSC received a letter from Quasha Ancheta Peña & Nolasco Law Offices requesting that they be furnished with complainant's contact details or, in the alternative, schedule a meeting with him to discuss certain matters concerning respondent.22 On the other hand, a fellow churchmember had also told him that respondent who, using the name "Atty. Patrick A. Caronan," almost victimized his (church-member's) relatives.23 Complainant also received a phone call from a certain Mrs. Loyda L. Reyes (Reyes), who narrated how respondent tricked her into believing that he was authorized to sell a parcel of land in Taguig City when in fact, he was not.24 Further, he learned that respondent was arrested for gun-running activities, illegal possession of explosives, and violation of Batas Pambansa Bilang (BP) 22.25 Due to the controversies involving respondent's use of the name "Patrick A. Caronan," complainant developed a fear for his own safety and security.26 He also became the subject of conversations among his colleagues, which eventually forced him to resign from his job at PSC.27 Hence, complainant filed the present Complaint-Affidavit to stop respondent's alleged use of the former's name and identity, and illegal practice of law.28 In his Answer,29 respondent denied all the allegations against him and invoked res judicata as a defense. He maintained that his identity can no longer be raised as an issue as it had already been resolved in CBD Case No. 09-2362 where the IBP Board of Governors dismissed30 the administrative case31 filed by Agtarap against him, and which case had already been declared closed and terminated by this Court in A.C. No. 10074.32 Moreover, according to him, complainant is being used by Reyes and her spouse, Brigadier General Joselito M. Reyes, to humiliate, disgrace, malign, discredit, and harass him because he filed several administrative and criminal complaints against them before the Ombudsman.33 On March 9, 2015, the IBP-CBD conducted the scheduled mandatory conference where both parties failed to appear.34 Instead, respondent moved to reset the same on April 20, 2015.35 On such date, however, both paiiies again failed to appear, thereby prompting the IBP-CBD to issue an Order36 directing them to file their respective position papers. However, neither of the parties submitted any.37 The IBP's Report and Recommendation On June 15, 2015, IBP Investigating Commissioner Jose Villanueva Cabrera (Investigating Commissioner) issued his Report and Recommendation,38 finding respondent guilty of illegally and falsely assuming complainant's name, identity, and academic records.39 He observed that respondent failed to controvert all the allegations against him and did not present any proof to prove his identity.40 On the other hand, complainant presented clear and overwhelming evidence that he is the real "Patrick A. Caronan."41 Further, he noted that respondent admitted that he and complainant are siblings when he disclosed upon his arrest on August 31, 2012 that: (a) his parents are Porferio Ramos Caronan and Norma Atillo; and (b) he is married to Rosana Halili-Caronan.42 However, based on the Marriage Certificate issued by the National Statistics Office (NSO), "Patrick A. Caronan" is married to a certain "Myrna G. Tagpis," not to Rosana Halili-Caronan.43 The Investigating Commissioner also drew attention to the fact that the photograph taken of respondent when he was arrested as "Richard A. Caronan" on August 16, 2012 shows the same person as the one in the photograph in the IBP records of "Atty. Patrick A. Caronan."44 These, according to the Investigating Commissioner, show that respondent indeed assumed complainant's identity to study law and take the Bar Examinations.45 Since respondent falsely assumed the name, identity, and academic records of complainant and the real "Patrick A. Caronan" neither obtained the bachelor of laws degree nor took the Bar Exams, the Investigating Commissioner recommended that the name "Patrick A. Caronan" with Roll of Attorneys No. 49069 be dropped and stricken off the Roll of Attorneys.46He also recommended that respondent and the name "Richard A. Caronan" be barred from being admitted as a member of the Bar; and finally, for making a mockery of the judicial institution, the IBP was directed to institute appropriate actions against respondent.47 On June 30, 2015, the IBP Board of Governors issued Resolution No. XXI-2015-607,48 adopting the Investigating Commissioner's recommendation. After a thorough evaluation of the records, the Court finds no cogent reason to disturb the findings and recommendations of the IBP. As correctly observed by the IBP, complainant has established by clear and overwhelming evidence that he is the real "Patrick A. Caronan" and that respondent, whose real name is Richard A. Caronan, merely assumed the latter's name, identity, and academic records to enroll at the St. Mary's University's College of Law, obtain a law degree, and take the Bar Examinations. As pointed out by the IBP, respondent admitted that he and complainant are siblings when he disclosed upon his arrest on August 31, 2012 that his parents are Porferio Ramos Caronan and Norma Atillo.49 Respondent himself also stated that he is married to Rosana Halili-Caronan.50 This diverges from the official NSO records showing that "Patrick A. Caronan" is married to Myrna G. Tagpis, not to Rosana Halili-Caronan.51 Moreover, the photograph taken of respondent when he was arrested as "Richard A. Caronan" on August 16, 2012 shows the same person as the one in the photograph in the IBP records of "Atty. Patrick A. Caronan."52 Meanwhile, complainant submitted numerous documents showing that he is the real "Patrick A. Caronan," among which are: (a) his transcript of records from the University of Makati bearing his photograph;53 (b) a copy of his high school yearbook with his photograph and the name "Patrick A. Caronan" under it;54 and (c) NBI clearances obtained in 2010 and 2013.55 The Issues Before the Court The issues in this case are whether or not the IBP erred in ordering that: (a) the name "Patrick A. Caronan" be stricken off the Roll of Attorneys; and (b) the name "Richard A. Caronan" be barred from being admitted to the Bar. The Court's Ruling To the Court's mind, the foregoing indubitably confirm that respondent falsely used complainant's name, identity, and school records to gain admission to the Bar. Since complainant - the real "Patrick A. Caronan" - never took the Bar Examinations, the IBP correctly recommended that the name "Patrick A. Caronan" be stricken off the Roll of Attorneys. The IBP was also correct in ordering that respondent, whose real name is "Richard A. Caronan," be barred from admission to the Bar. Under Section 6, Rule 138 of the Rules of Court, no applicant for admission to the Bar Examination shall be admitted unless he had pursued and satisfactorily completed a pre-law course, VIZ.: Section 6. Pre-Law. - No applicant for admission to the bar examination shall be admitted unless he presents a certificate that he has satisfied the Secretary of Education that, before he began the study of law, he had pursued and satisfactorily completed in an authorized and recognized university or college, requiring for admission thereto the completion of a four-year high school course, the course of study prescribed therein for a bachelor's degree in arts or sciences with any of the following subject as major or field of concentration: political science, logic, english, spanish, history, and economics. (Emphases supplied) In the case at hand, respondent never completed his college degree. While he enrolled at the PLM in 1991, he left a year later and entered the PMA where he was discharged in 1993 without graduating.56 Clearly, respondent has not completed the requisite pre-law degree. The Court does not discount the possibility that respondent may later on complete his college education and earn a law degree under his real name.1âwphi1 However, his false assumption of his brother's name, identity, and educational records renders him unfit for admission to the Bar. The practice of law, after all, is not a natural, absolute or constitutional right to be granted to everyone who demands it.57 Rather, it is a privilege limited to citizens of good moral character.58 In In the Matter of the Disqualification of Bar Examinee Haron S. Meling in the 2002 Bar Examinations and for Disciplinary Action as Member of the Philippine Shari 'a Bar, Atty. Froilan R. Melendrez,59the Court explained the essence of good moral character: Good moral character is what a person really is, as distinguished from good reputation or from the opinion generally entertained of him, the estimate in which he is held by the public in the place where he is known. Moral character is not a subjective term but one which corresponds to objective reality. The standard of personal and professional integrity is not satisfied by such conduct as it merely enables a person to escape the penalty of criminal law. Good moral character includes at least common honesty.60 (Emphasis supplied) Here, respondent exhibited his dishonesty and utter lack of moral fitness to be a member of the Bar when he assumed the name, identity, and school records of his own brother and dragged the latter into controversies which eventually caused him to fear for his safety and to resign from PSC where he had been working for years. Good moral character is essential in those who would be lawyers.61 This is imperative in the nature of the office of a lawyer, the trust relation which exists between him and his client, as well as between him and the court.62 Finally, respondent made a mockery of the legal profession by pretending to have the necessary qualifications to be a lawyer. He also tarnished the image of lawyers with his alleged unscrupulous activities, which resulted in the filing of several criminal cases against him. Certainly, respondent and his acts do not have a place in the legal profession where one of the primary duties of its members is to uphold its integrity and dignity.63 WHEREFORE, respondent Richard A. Caronan a.k.a. "Atty. Patrick A. Caronan" (respondent) is found GUILTY of falsely assuming the name, identity, and academic records of complainant Patrick A. Caronan (complainant) to obtain a law degree and take the Bar Examinations. Accordingly, without prejudice to the filing of appropriate civil and/or criminal cases, the Court hereby resolves that: (1) the name "Patrick A. Caronan" with Roll of Attorneys No. 49069 is ordered DROPPED and STRICKEN OFF the Roll of Attorneys; (2) respondent is PROHIBITED from engaging in the practice of law or making any representations as a lawyer; (3) respondent is BARRED from being admitted as a member of the Philippine Bar in the future; (4) the Identification Cards issued by the Integrated Bar of the Philippines to respondent under the name "Atty. Patrick A. Caronan" and the Mandatory Continuing Legal Education Certificates issued in such name are CANCELLED and/or REVOKED; and (5) the Office of the Court Administrator is ordered to CIRCULATE notices and POST in the bulletin boards of all courts of the country a photograph of respondent with his real name, " Richard A. Caronan," with a warning that he is not a member of the Philippine Bar and a statement of his false assumption of the name and identity of "Patrick A. Caronan." Let a copy of this Decision be furnished the Office of the Bar Confidant, the Integrated Bar of the Philippines, and the Office of the Court Administrator. SO ORDERED.