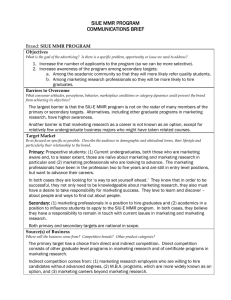

European Journal of Physiotherapy ISSN: 2167-9169 (Print) 2167-9177 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iejp20 A qualitative study among women immigrants from Somalia – experiences from primary health care multimodal pain rehabilitation in Sweden Bruno Semedo, Britt-Marie Stålnacke & Gunilla Stenberg To cite this article: Bruno Semedo, Britt-Marie Stålnacke & Gunilla Stenberg (2020) A qualitative study among women immigrants from Somalia – experiences from primary health care multimodal pain rehabilitation in Sweden, European Journal of Physiotherapy, 22:4, 197-205, DOI: 10.1080/21679169.2019.1571101 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2019.1571101 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 18 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1602 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=iejp20 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSIOTHERAPY 2020, VOL. 22, NO. 4, 197–205 https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2019.1571101 ORIGINAL ARTICLE A qualitative study among women immigrants from Somalia – experiences from primary health care multimodal pain rehabilitation in Sweden Bruno Semedoa , Britt-Marie Stålnackeb and Gunilla Stenberga a Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiotherapy, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; bCommunity Medicine and Rehabilitation, Rehabilitation Medicine, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Background: Immigrants often experience difficulties with acculturation and post migratory stress after arrival in a host country and studies report poor health, chronic pain and depression. This is a challenge for primary health care and interventions need to be evaluated. Objectives: To explore the experiences of a group of women from Somalia who took part in a multimodal pain rehabilitation programme in primary healthcare in Northern Sweden. Methods: Seven individual interviews a few months after participation, and a focus group discussion one year after the programme were conducted and analysed with Grounded theory. Results: A core category regained life emerged from the data. This was described as a process in two categories: panic and connection. The participants experienced that the programme was helpful and that the pain was reduced. They became more open-minded; got new ideas and knowledge; were helped to improve their societal adaptation and integration; experienced that they were not alone; and learned that there is benefits when a group of people share experiences and feelings. Conclusions: Multimodal pain rehabilitation can be helpful for women immigrants from Somalia. The programme triggered positive changes in their lives and they received knowledge about how to manage pain and improved their self-confidence and health. Received 3 August 2018 Revised 7 January 2019 Accepted 12 January 2019 Published online 15 February 2019 KEYWORDS Primary healthcare; group treatment; team treatment; chronic pain; musculoskeletal pain Abbreviation: MMR: multimodal rehabilitation Introduction Chronic pain is one of the most disabling and costly afflictions in the developed world, but its burden is equally or more important in the developing world [1–3]. Approximately, 20% of the world’s population suffers from chronic pain [3]. In Sweden, chronic pain is more common among women than men and among immigrants [4]. According to Statistics Sweden, approximately 53,987 emigrants came to Sweden from Somalia between 2000 and 2014 [5] and around 7200 Somalis received Swedish citizenship between 2000 and 2011 [6]. These immigrants are passing or have passed through a process called acculturation. Acculturation is the changes that occur as a result of contact with culturally different people, groups and social influences [7], even if these changes occur as a result of intercultural contact [8]. Migrants (immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers) often experience difficulties with acculturation and post migratory stress after arrival in a host country. This stress may be related to language barriers, unemployment, cultural differences, lack of social support, and experiences of discrimination, xenophobia or racism [9,10]. These factors place migrants at risk for physical and mental disorders [11]. Some migrants report their health to be good or very good before moving to the host country [12]. However, this CONTACT Gunilla Stenberg gunilla.stenberg@umu.se can change completely after migration, with subsequent reports of poor health and feelings of depression and loneliness [12]. Moreover, migrants report poorer health when compared with local inhabitants [11]. If gender is taken in consideration during the migrant’s acculturation, women tend to be at a higher disadvantage when compared to men. The disadvantage makes female migrants even more prone to depression or feelings of loneliness [12,13]. One reason for this may be a lack of higher education which makes it more difficult for women to compete with men in the labour market [12,13]. In addition, having chronic pain further complicates the situation and leads to loss of control [14,15]. Healthcare does not always support immigrant women in finding a way forward, but rather holds them back [15]. According to International Association for the Study of Pain [16], ‘pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’. Pain syndromes are distinguished on the basis of duration, site and pattern [17,18]. Chronic pain is not transitory like acute pain, and persists more than three to six months [18]. Manifestations of plastic and biological changes, which may be permanent, are responsible for pain transmission to the neural pathways and other tissues, and will be partly responsible for that pain became Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiotherapy, Umeå University, Umeå 90187, Sweden ß 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. 198 B. SEMEDO ET AL. Table 1. Background data for the participants. Settings Participant Age (years) Number of children Individual interview Focus group P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P6 P7 38 51 44 51 39 43 51 2 1 1 1 3 1 6 冑 冑 冑 冑 冑 冑 冑 冑 x 冑 冑 x 冑 冑 冑: present; x: not present. chronic [17,19]. However, psychological factors (such as depression, anxiety, fear, lack of self-confidence, and inability to handle different negative situations or events) also play an important role in pain experience [17,20] and chronic pain negatively affects quality of life when about 1/3 of those who suffer from chronic pain are less able or unable to maintain an independent lifestyle [21]. Therefore, it is important to determine appropriate treatment, focussing on the original cause of the pain and taking into consideration all the other factors that contribute to perpetuation of the pain. Scientific evidence shows that multimodal rehabilitation (MMR) can be more effective than separate interventions to reduce pain, increase return to work, give a more active life, and shorten sick leave [17]. Since 2011, national guidelines in Sweden for selection criteria are available to support assessment of patients with chronic pain, and thereby offer MMR on the appropriate level (specialist vs. primary healthcare) [22]. MMR programmes typically consist of psychological interventions combined with physical therapy, exercise or activity. MMR is based on a biopsychosocial model [23] that assumes that successful treatment must take in consideration somatic, psychosocial, environmental and personality factors. MMR involves interventions that proceed from a holistic perspective, combining behavioural psychological approaches and physical activity or relaxation exercises. MMR involves several methods to manage pain, as well as education about pain and physical activity. MMR is a process, and consists of well-planned and coordinated actions led by a team of professionals with a common goal [24]. The professionals who may be involved in the multimodal team include a medical doctor, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker and psychologist. There is a need to examine chronic pain, together with psychosocial points of view, especially with regard to immigrants and refugees who suffer from chronic pain and usually have more difficulty accessing healthcare [13]. These groups have not been included in previous studies of MMR and it is important to let the patients’ voices be heard. Therefore, we performed a qualitative study that aimed to explore the experiences of a group of women from Somalia who took part in a multimodal pain rehabilitation programme in primary healthcare in Northern Sweden. Methods A qualitative approach with emergent design was used with individual interviews and one focus group discussion. Grounded theory [25] was used for the data analysis. A group of Somalian women underwent an MMR programme with a biopsychosocial approach in a healthcare centre in Northern Sweden. The programme took place during the autumn of 2013. Women with some type of chronic musculoskeletal pain (mostly joint and muscle pain) were invited to take part in the programme. Eight women participated. The programme consisted of six weekly group sessions. Each session lasted up to two hours. There were one nurse, two physiotherapists, and one medical doctor involved in the programme. One of the physiotherapists had further education in cognitive behavioural therapy. The MMR programme consisted of physical activities like outdoor group walks and swimming lessons, and theoretical interventions like counselling about diet, body awareness, how to cope with pain, and women’s health. Study participants were originally from Somalia. Somalia has suffered from many internal problems since its authoritarian socialist regime collapsed in 1991 and resulted in many refugees. Participants reported that they were active in Somalia and did not have pain or difficultly performing their normal activities when they lived there. The age of the participants varied from 34 to 52 years old (Table 1) and they lived in Sweden. Five participants were married but only two lived with their husbands. All the participants had children and lived with their children. Five were searching for a job, one was on sick leave, and one was a student. Four had never worked in Somalia. Three had 3–10 years of education, and the rest had not frequented school before they emigrated to Sweden. Data collection The inclusion criterion was patients who participated in an MMR programme for women from Somalia. They were informed about the study and asked to participate by one of the professionals in the MMR team. If they answered, they received an invitation letter by the first author at the beginning of 2014. The letter was written in two languages, Swedish and Somali. Seven participants were included and one declined to participate. The individual interviews took place during February to April 2014. An interview guide with open ended questions was created for the individual interviews by the research team. The questions were open-ended and mainly about the participant’s experiences from the programme, e.g. if and what help they got from the MMR programme, and what could have been done to have a better programme. The first question was always ‘How do you feel being part of the programme?’ All individual interviews were conducted in the meeting room at the healthcare centre where the MMR programme took place. Three people were present during the interviews, the participant, the interviewer (BS) and an interpreter. Three different interpreters were used; one woman interpreted for five of the individual interviews and the focus group discussion. The interpreter was asked to be as explanatory as EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSIOTHERAPY 199 Figure 1. The model describes the process experienced by the participants. On the top is the core category that resulted from the whole process. The large circles represent the categories, and the smaller circles the subcategories. Both large circles are connected by the MMR programme which triggered the process of change. possible when translating the questions. The reason for this was to promote a clear understanding of the questions for the participant. The interpreter was also asked to interpret the answers word by word, as nearly as possible to the original, so that loss of the original information would be kept to a minimum. The length of the interviews was from 15 to 60 minutes. As a second step to deepen the analysis, a focus group discussion was carried out. All women who participated in the MMR-programme were asked to participate in a focus group discussion at a one year follow-up. A new invitation letter was sent and a new interview guide was created to fit the focus group discussion. The questions in the interview guide related to how the programme affected participants during the past year. Five participants gathered for the focus group discussion in November 2014 in the conference room at the same primary health care centre as before. The first author (BS) led the group discussion. One particular team member (the nurse) was asked to be present. She was present during all of the MMR sessions and therefore had an important role during the MMR project. The participants were acquainted with her, and thought to be more at ease to interact during the discussion. Another member of the research team (GS) was present at the focus group discussion to help with the moderation if needed. All the participants sat around an oval table, and the focus group was held for an hour and 20 minutes. Data analyses The interviews and focus group discussion were recorded using an MP3 recorder and transcribed using verbatim transcription. Analyses of the transcribed data were done using Open Code version 4.01 [26]. The analysis was done in several steps, starting with open coding, then focussed coding, and selective coding [25,27]. After these steps, subcategories started to emerge, followed by categories and the main category. Triangulation of the data was made by three persons (BS, GS, MR). The analyses were made independently and then negotiated in the research team to increase the credibility and validity of the results. Finally, a model was created to illustrate the process (Figure 1). Ethical considerations During the course of this study, general ethical principles regarding research were followed and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Umeå University (document number 2013-192-31 M). The letters of invitation clearly stated the objectives of the study and informed the participants that participation in the study would be completely voluntary. The participants were informed that possible future treatments at the healthcare centre would not be influenced by their participation (or lack of participation) in the study. All written information was explained verbally before the individual interviews and focus group discussion. It was also explained that their answers would be confidential, and that there would be no right or wrong answers. After being ensured of the study intentions, the participants signed an informed consent. Results One core category regained life emerged from the interviews and the focus group. The core category represents a process that positively influenced participants’ lives. This process was experienced from the beginning of the MMR programme and continued one year after the end (Figure 1). The main result from the whole process was that participants became more open-minded. They acquired new ideas and knowledge, obtained help to improve their adaptation and 200 B. SEMEDO ET AL. Table 2. Core category, categories, subcategories and examples of open codes. Core category Categories Subcategories Open codes Regained life Panic Life crisis Big shock in the body Life suddenly became different Unemployment creates chaos Was always in the bed Isolation makes us sicker Felt almost imprisoned Had pain in the whole body Was very tired Not possible to walk Whole musculature was tense Thought that I had a serious disease Searched for medical help weekly Got a lot of treatments Expensive healthcare before the programme Good experiences in the programme Interesting and useful programme Programme encourages and gives a lot Programme gives more in the group Group promoted interaction We learn from each other We participated together in the activities We got a lot of useful information Learned how to perform activities better Learned how to exercise, train and walk Learned the consequences of inactivity Got to understand better how our bodies work Know that is important to take care of the body Made us handle (things) without the doctor We got to know how to help ourselves Forward the information to others Can help to promote the programme to others Tried to help others I got my health again Feel better and healthier after the programme Pain became easier to handle I feel younger Isolation Experienced poor health Constant search for medical help Connection Positive experiences in the programme Good interaction as a group Attained knowledge Self-management and self confidence Willingness to share Improved health integration in the society, realised that they were not alone with their problems, and recognised that there was something to gain if a group of people share their experiences and feelings. When the participants described their experiences before the programme, they often used the word I, defining the participants as individual entities. These individual entities changed to we (the group of participants) when they described their experiences during and after the programme. Two categories were associated with the core category: panic and connection. Four subcategories were associated with the category panic, and six subcategories with the category connection (Table 2). The core category, categories, subcategories and examples of codes are presented in Table 2. The relations between the theme, categories and subcategories are presented in Figure 1. Explanations of each category are presented in the text below. Subcategories are marked in italics. Quotations from the participants are presented, indented in the text. Panic The category panic was related to participant experiences and feelings before attending the programme. The subcategory life crisis was related to experiences and feelings that participants had in their personal life before the start of the MMR programme. The differences between Somalia and Sweden (e.g. culture, language, food, weather) made it difficult for participants to be acquainted with Swedish settings. It is a great change when moving from one’s own country to another completely different (one). It feels like a shock in the body and it takes time to gain roots. It takes several years for one to understand how to survive. (P2) The participants felt as if they had lost their identities when they came to Sweden. Some reported that they were used to interacting with other people in Somalia but since they moved to Sweden, they were not able to interact with the local inhabitants because of language barriers. This led to difficulties in finding a job and being self-sufficient. Unemployment and the barriers to being active in Swedish society led to what the participants expressed as troubles in their lives. … it’s the unemployment that is the worst and therefore creates chaos. (P4) Weather differences between Somalia and Sweden were negative in the participants’ lives. They reported missing the sunny and warm climate of Somalia, and felt that the short and cold winter days in Sweden made them feel depressed. … we were used to be in a sunny country and suddenly we came to a country that hardly has sun during the winter, and it causes the body to be in shock. (P3) The participants experienced isolation and felt loneliness. They sometimes felt like they were imprisoned, alone and EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSIOTHERAPY misplaced. Some even had feelings of hopelessness. This lead to feelings of fear, stress, anxiety and depression, and these contributed to poorer reported health. This was further intensified if the participants had children to care for. Over time, these feelings resulted in a vicious spiral. More fear, stress and anxiety led to isolation and desire to only stay in bed. It’s not good to be isolated and to be alone. One becomes more ill. (P6) Participants experienced poor health in general before the MMR programme. Some participants also reported fatigue. This was permanent, and sometimes on such a large scale that it impeded performance of being active and their normal daily activities. I had pain in the whole body and a lot of tiredness during that time, indeed. (P2) Some participants reported stomach pain. They related the pain and poor health to stress and poor eating habits that they acquired when they came to Sweden. This was because of difficulty in accessing fresh and familiar foods, as well as the high price of food (especially fresh food) in Sweden compared to Somalia. Stomach pain and musculoskeletal pain made some of the participants feel desperate. I had pain and was so tense that I thought that I had a serious disease. (P2) Participants stated that their health started to deteriorate significantly when they moved to Sweden. The subcategory constant search for medical care represented experiences the participants had in their search and need for healthcare. Before the start of the MMR programme, the participants searched for medical help at their local healthcare centre. The participants stated that the medical staff could not find any relevant problems with them. Even if the medical staff tried to explain that there was nothing wrong with the participants’ bodies, the staff prescribed medicines for the pain. The permanence and worsening of symptoms, and lack of answers for the patient’s problems led to feelings of frustration and insecurity. … . I almost thought that I had something broken, and visited the doctor so many times. (P1) According to the participants, the situation was like an endless loop. They only searched for medical help more frequently, and in some cases, they ‘visited the doctor once a week’. Another reported aspect was the expense of the medical care and prescribed medicines. Even though Sweden has a state-delimited annual limit for healthcare expenses, these were an extra burden on their limited incomes. The participants stated that before coming to Sweden they rarely searched for medical help. Connection The category ‘connection’ was related to participant experiences and feelings during and after the programme. 201 Participants had positive experiences regarding the MMR programme that they expressed as interesting, useful and helpful. The most valued were judged to be the diet classes and physical activities. All parts of the programme stimulated, motivated and encouraged the participants to be active. This was something that had not happened since they moved from Somalia. For example, the group walks were a fun, efficient and inexpensive way for them to be active. Contact with the water during swimming classes was especially appreciated. Some of the participants claimed that they could ‘go further with their lives’, and that the programme experiences helped them to ‘get their lives back again’. What is good is that everything that I got here has helped me to live today. (P1) Participants were unanimous about the programme being very good and useful. However, there were some topics raised that were said could be improved, such as too few swimming lessons, and problems with being together with participants who already knew how to swim. Some participants wanted further development of the programme, and asked for a continuation (like a Step 2). Good interaction as a group was another subcategory that emerged. The participants reported being pleased with the experiences they had in the group created for the programme. The opportunity to share their experiences, opinions, ideas, knowledge and feelings with the rest of the group and the staff promoted an important interaction that would be impossible if the programme was held only on an individual level. They stated that training in group was not only therapeutic, but also fun. The fact that the participants shared a similar cultural background, language and problems, was also pointed out as positive. These common factors promoted an easier and better interaction. One learns and gets a lot from each other. One learns about experiences and opinions. It provides much more if there are many (people) compared to just one. (P2) Attained knowledge represented the general knowledge that the participants obtained from the programme. This knowledge was related to several aspects, such as information about diet, different training options, pain, body awareness and women’s health. All the information that I got here has helped me to live today. (P1) Information about diet was commended by all participants. They improved and adapted their diet, learned how to access and prepare food, how to combine different foods, and about the need to ingest dietary sources of vitamin D. They talked about food with us … it was good to be there and to learn how to eat properly. (P4) Information about exercise and physical activity as a way to reduce pain symptoms and maintain good health was also appreciated. Participants reported that walking was an activity that they often performed in their home country. However, they had become less physical active since they moved to Sweden. Interval training instructions were 202 B. SEMEDO ET AL. experienced as fun, and helped them to be more active. Participants liked learning to swim and especially having contact with water since it is relaxing and fun. They appreciated the opportunity to swim indoors during the cold and dark winter months. Participants reported having to learn about training in the gym as a way to be physical active and to improve their health. Gym training was something new for some of the women. They assessed gym training as a good alternative, especially during the winter months, since it becomes challenging and difficult to train and be active outdoors. It was also clear that participants were willing to share their knowledge with other people who might be in the same situation they were before the programme. The participants emphasised a strong willingness to promote the programme and provided some ideas about how to do it. They even presented the possibility of being available to talk about their experiences to anyone who wanted information about the programme and might be interested in participating. I started to go to the gym, and that was something that I didn’t care about or wanted to do before. (P2) … . we are ready, and prove that they will become healthier with the program. (P3) Discussions of body awareness were also an appreciated topic. The participants reported that they started to feel their bodies in a different way, started to realise that their pain was not related to serious disease, and that the pain could be manageable. Some participants reported that they were afraid of exhaustion before the programme, since they thought that a rapid heartbeat could result in major heart problems or even death. During the programme, they learned that higher heart beats and becoming tired are due to poor physical condition, and this was something that could be improved. Improved health. This subcategory represented the participant’s own assessed state of health after the MMR programme. Participants generally reported that their pain was reduced, reduced to some extent, or completely resolved after the programme. I learned that if the heart beats fast and I become breathless it is not something serious, it is just bad physical condition. (P3) The subcategory self-management and self-confidence showed how the participants acquired ability to take care of themselves and their own health, and they started to be more confident. The knowledge attained helped them realise that they did not need to visit the doctor every time a little problem occurred. They learned that they could reduce their need and search for medical help. I visited the doctor once a week before … .Nowadays, I haven’t come here for almost a year. We (participant and healthcare staff) haven’t met because of this program. (P1) This confidence led the participants to perform their daily activities more effectively. The association of factors like understanding of their bodies, less need and search for medical help, and better ability to perform the daily activities, influenced the willingness and motivation to participate in activities, meet other people, get a job, integrate into society, and reach their goals. … . we can continue with our lives! (P2) Directly after the MMR programme, some participants asked questions about problems in finding a place to be physically active after the end of the programme. At one year follow up, the participants enthusiastically said that they had solved this themselves by renting a place where they could have dancing lessons together, and also bring other friends. Willingness to share represented the willingness of participants to share their programme experiences and knowledge with others. In some cases, the participants stated that they had influenced others, e.g. family and friends, to be more active. We have learned interval training. I started to do that with my husband. (P3) My pain is completely gone, thanks to the program. (P7) The participants generally reported that their health was improved and some participants reported that they felt younger and even had regained their health. The state of health that participants referred to was the one they had in their home country, before the war, and before coming to Sweden. I got my health again! (P1) However, there were also exceptions. One participant said that her main disease had already been treated with specific medical help before the MMR programme, and therefore did not notice any changes in her health with the MMR programme. Discussion This qualitative study provides insights into the feelings and experiences that a group of women immigrants with chronic pain expressed in connection with a multimodal pain rehabilitation programme. The programme triggered a process that changed the participants and their lives in a positive way when they attained knowledge about pain, diet and how to exercise, became capable to taking care of themselves, and improved their self-confidence. Most participants improved their health as well. The participants expressed this as they regained life. Before the programme started, the participants reported that their lives were in crisis and chaos, and that they were mostly isolated from the rest of the society. These results are in accordance with previous research [12,14,15,28,29], in which female immigrant pain patients reported loss of their identities and social network. They developed emotional distress, were depressed, and lost their ability to carry out the daily activities that they were used to performing. The participants in our study experienced their health as poor before the MMR programme. Many immigrants experience their health as poor or very poor when they come to a host country, and report physical disabilities due to pain which EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSIOTHERAPY includes persistent suffering, fatigue, limited endurance [12,13,28–30] and mental ill-health [14,15]. This often led to healthcare visits. Constant or frequent searches for help and health care before the MMR programme was a topic raised by the participants in our study. Other studies also describe this behaviour [14,15,28,29,31]. In the current study, the participants were unanimous about the usefulness of knowledge attained from the MMR programme. Ekhammar et al. report factors such as coping with pain or understanding their bodies and their respective limitations or problems as useful knowledge acquired from MMR programmes [31]. The programme also led to improvement in their health. These results are supported by other studies of MMR, which show long-term positive effects on pain and disability [31,32]. The MMR programme trigged a change that led to a new course in the participants’ lives. In their own words, as they ‘got their life back’. This is in agreement with another study where MMR led to feelings of empowerment and regained hope [31]. Other long-term effects on depression and several domains of life satisfaction are seen after MMR [32]. The increase in self-management was another topic raised by participants. Some studies support this, in that participants report having more confidence in themselves, and better strategies for coping with pain [28,32]. Another important result was the lesser need and search for healthcare after the programme. In another study, MMR programme participants had fewer negative beliefs about recovery, and were therefore less frequently referred back to primary health care for follow-up compared to participants of an individual rehabilitation programme [32]. Patients participating in MMR programmes are commonly included in a group. According to our participants, it was beneficial and this is also described in other studies of MMR [32,33]. Patients in group rehabilitation reported reduced anxiety and depression, and improved body image [28]. However, others report no differences when group rehabilitation is compared to individual rehabilitation [34]. Similar to other studies, the immigrant women felt isolated and missed the social interaction from their host country [14,29]. As our MMR group was adapted so that participants shared a similar language, background and culture, they had the opportunity to express themselves and share their own experiences with the group. The interaction between group members resulted in them becoming we instead of I. This may have contributed to the programme’s positive results. After the MMR programme, participants reported a willingness to share their acquired knowledge from the MMR programme with others like their family and friends. There are studies about patients who started to socialise more, and had more willingness to interact with the surrounding society after MMR. For example, they interacted more with their families or searched for a job [31,32]. Even if the results from these studies do not precisely support our study results, they are similar in the way the participants were willing to interact more with others after the MMR programmes. 203 Participants reported that they liked their lives in Somalia even if there were problems there, and they would not want to emigrate if it wasn’t for the war. The participants pointed out that when they lived in Somalia, they had a job, a house, a family, a social network, fresh food on the table, good weather, and most importantly, good health and no signs of depression. These topics are in accordance with those already documented in the literature [12,29], where immigrants reported having good health, no signs of depression, and no feelings of loneliness before moving to the host country. Some participants expressed difficulties in finding a place to do physical activities after the programme. Even if they participated in the programme and had positive results, they need to have proper stimulation to continue to have an active life. This is important to be aware of since physical activity has a positive long-term influence on many diseases [35]. In a study by Stenberg et al., some health care professionals doubted the appropriateness of group rehabilitation for immigrants due to the need for an interpreter and different cultural views on pain [36,37]. In this study, immigrants found MMR to be beneficial even if an interpreter was used. Norrefalk et al. found that interdisciplinary rehabilitation in an 8-week programme for patients with chronic pain was beneficial to the same extent for immigrants as for native Swedes in terms of return-to-work [36]. However, it has been reported that the healthcare ‘one size fits all system’ does not work for our multicultural society [7]. Our healthcare systems and healthcare providers have to evolve and adapt to the different situations that arise when those that search for help have very different backgrounds and cultures [15]. This study can serve as an encouragement to set up MMR programmes for immigrants with chronic pain in primary health care. However, there is a need to further study the rehabilitation process among both women and men immigrated from different parts of the world. Methodological discussion Individual interviews are good for participants who are not talkative, because they can take their time in answering [38,39]. In this study, the participants had no problems criticising the least good aspects of the programme. Even the less talkative participants had enough time to express their experiences and thoughts. Some of the participants were a little apprehensive about expressing their feelings and opinions to someone they did not know, especially at the beginning of the interviews. This could also be because the interviewer was a man. It is possible that a woman would get the answers more promptly. To overcome these difficulties, and since some of the interviews were short, we decided to add a focus group interview. A focus group interview is useful to perform explorative studies in a new field because the lively collective interaction can generate spontaneous, expressive and emotional perceptions on a higher scale than the individual interview [39]. In that way, focus group worked very well in this study. However, the 204 B. SEMEDO ET AL. participants did not report any negative experiences of programme like they sometimes did during individual interviews. Some difficulties of using a man as interviewer were noticed during the focus group discussion. Even when there was a lot of positive energy from the group, the answers and questions posed by the participants were usually directed to other MMR group members, to the woman member of the MMR team, or the woman member of the research team, and not to the interviewer. The interviews and focus group discussion were held in Swedish because the interviewer was unable to speak Somali. The participants had very limited knowledge of Swedish and an interpreter had to be used. The way in which the experiences and ideas were formulated and expressed could have been affected to a greater or lesser extent. Some sentences had to be paraphrased in the transcriptions to make them more fluent. All the coding was then directly written into English for the final paper. There is a risk for translation bias when translating from Somali to Swedish and then to English. This is a challenging problem and not new to this study [35]. However, it was not possible to find an interpreter that could translate from Somali direct to English. The first author has a physiotherapy degree as clinical background and academic training in qualitative research. He also has his own experiences of moving from one country and culture to another. This was a positive experience when talking about relevant topics to be included in the interview guide, and also led to sensitivity when conducting the interviews. There may be a risk of taking one’s own experiences into the analysis, if one is being subjected to the same phenomena that is under study. The first author was aware and reflected on this during the research process. To enhance trustworthiness, triangulation was used with several researchers involved in the analysis and negotiating the result. The second author (BMS) has extensive experience in the specialty care of chronic pain patients. The third author (GS) has clinical experience in primary health care. Both second and third authors have academic experience in qualitative research. The participants’ mainly positive experiences in this study could be due to cognitive dissonance [40]. This phenomenon suggests that one seeks psychological consistency between personal expectations and reality. Even if the participants did not seem to have difficulties expressing their opinions, they may have accepted some lesser attractive approaches/ideas during the programme’s course in order to find the necessary psychological consistency. This acceptance may have been further exacerbated since the programme was held in a group, as one is more prone to accept something less pleasant if others also accept it [40]. Conclusions This study provides insight into the experiences that a group of immigrant women had as participants in a MMR programme. The participants pointed out that their experiences were very positive, and the programme triggered positive changes in their lives. They learned about pain, diet and how to exercise, became capable of taking care of themselves, and improved their self-confidence, health and reduced their pain. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing their stories. Thanks to Marta Ramos (MR) who assisted with the triangulation and analysis. Disclosure statement The authors report no declarations of interest. Funding This work is supported Agency, REHSAM. by the Swedish Social Insurance ORCID Bruno Semedo Gunilla Stenberg http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2916-0628 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9231-3594 References [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287. Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organization supports global effort to relieve chronic pain; 2004 [cited 2018 Aug 01]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/ releases/2004/pr70/en/ €m P, Ho €gstro €m K, et al. Chronic musculoskelBergman S, Herrstro etal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1369–1377. €r Myndigheten fo samh€allsbeskydd och beredskap. S€akerhetspolitik. Sverige och Somalia. [Security. Sweden and Somalia]; 2014 [cited 2018 Aug 01]. Available from: http://www. sakerhetspolitik.se/Konflikter/Somalia/ Sweden Statistics. Invandringar och utvandringar efter €delseland och ko €n. År 2000–2015 [Immigration and emigrations fo by country of birth and gender 2000–2015]; [cited 2018 Aug 01]. Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101J/ImmiEmiFod/?rxid¼2c9b596406f9-4f54-b24c-40378c39010a Gibson MA. Immigrant adaptation and patterns of acculturation. Hum Dev. 2001;44:19–23. Arnett JJ. The psychology of globalization. Am Psychol. 2002;57: 774. ^te D. Intercultural communication in health care: challenges Co and solutions in work rehabilitation practices and training: a comprehensive review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:153–163. Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, et al. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am Psychol. 2010;65:237. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSIOTHERAPY [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] Beiser M. The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Can J Public Health/Rev Can Sante’e Publiq. 2005;96:S30–S44. Sethi B. Service delivery on rusty health care wheels: implications for visible minority women. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2013;10: 522–532. Sethi B. Newcomers health in Brantford and the counties of Brant, Haldimand and Norfolk: perspectives of newcomers and service providers. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2013;15:925–931. M€ ullersdorf M, Zander V, Eriksson H. The magnitude of reciprocity in chronic pain management: experiences of dispersed ethnic populations of Muslim women. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25: 637–645. Zander V, M€ ullersdorf M, Christensson K, et al. Struggling for sense of control: everyday life with chronic pain for women of the Iraqi diaspora in Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41: 799–807. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) taxonomy; 2017; [cited 2018 Aug 01]. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain. org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber¼1698&navItemNumber ¼576#Pain Ahlberg M, Axelsson S, Eckerlund I, et al. Rehabilitering vid €versikt. Stockholm: SBUlångvarig sm€arta: En systematisk litterturo €r medicinisk utv€ardering; 2010. Statens beredning fo Merksey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. p. 59–71. Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152:S2–S15. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Lee S, et al. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain. 2007;129:332–342. Harstall C, Ospina M. How prevalent is chronic pain. Pain Clin Updates. 2003;11:1–4. Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR). €r multimodal rehabilitering vid långvarig sm€arta Indikationer fo [National Medical Indications 2011. Indications for multimodal rehabilitation for patients with chronic pain]; 2011 [cited 2018 Aug 01] Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Site CollectionDocuments/nationella-indikationer-multimodal-rehabilit ering.pdf Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, et al. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:581. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, et al. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69:119–130. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE; 2006. ICT Services and System Development and Division of Epidemiology and Global Health. OpenCode 3.4. Umeå: Umeå [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] 205 University; 2013; [cited 2018 Oct]. Available from: http://www. phmed.umu.se/english/units/epidemiology/research/open-code/ Dahlgren L, Emmelin M, Winkvist A, et al. Umeå universitet. €r folkh€alsa och klinisk medicin. Epidemiologi. Institutionen fo Qualitative methodology for international public health. 2nd ed. Umeå: Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University; 2007. 218 pp. Michae€lis C, Kristiansen M, Norredam M. Quality of life and coping strategies among immigrant women living with pain in Denmark: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008075. Nyen S, Tveit B. Symptoms without disease: exploring experiences of non-Western immigrant women living with chronic pain. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39:322–342. Nortvedt L, Hansen HP, Kumar BN, et al. Caught in suffering bodies: a qualitative study of immigrant women on long-term sick leave in Norway. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:3266–3275. Ekhammar A, Melin L, Thorn J, et al. A sense of increased living space after participating in multimodal rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:2445–2454. Merrick D, Sundelin G, Stålnacke B-M. One-year follow-up of two different rehabilitation strategies for patients with chronic pain. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:764–773. Pietil€a EH, Stålnacke B-M, Enthoven P, et al. "The acceptance" of living with chronic pain—an ongoing process: a qualitative study of patient experiences of multimodal rehabilitation in primary care. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50:73–79. Dufour N, Thamsborg G, Oefeldt A, et al. Treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized, clinical trial comparing groupbased multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation and intensive individual therapist-assisted back muscle strengthening exercises. Spine. 2010;35:469–476. Reiner M, Niermann C, Jekauc D, et al. Long-term health benefits of physical activity – a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:813. Norrefalk J-R, Ekholm K, Linder J, et al. Evaluation of a multiprofessional rehabilitation programme for persistent musculoskeletal-related pain: economic benefits of return to work. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:15–22. Stenberg G, Pietil€a Holmner E, Stålnacke B-M, et al. Healthcare professional experiences with patients who participate in multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary care – a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:2085–2094. King N. Horrocks C. Interviews in qualitative research. London: Sage; 2010. Wibeck V. Fokusgrupper: om fokuserade gruppintervjuer som €kningsmetod. 2. Uppdaterade och uto €k. uppl. ed. Lund: underso Studentlitteratur; 2010. Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford (CA): Stanford U.P.; 1957.