WHO - Response to measles outbreaks in measleas mortality reduction settingeng

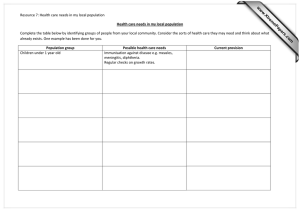

advertisement