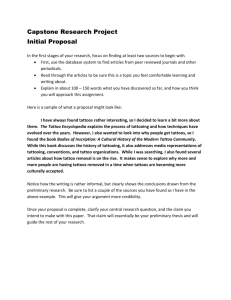

Body Image 8 (2011) 245–250 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Body Image journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bodyimage Tattoos and piercings: Bodily expressions of uniqueness? Marika Tiggemann ∗ , Louise A. Hopkins Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Received 3 November 2010 Received in revised form 29 March 2011 Accepted 29 March 2011 Keywords: Body modification Need for uniqueness Tattoos Body piercing Appearance investment The study aimed to investigate the motivations underlying the body modification practices of tattooing and piercing. There were 80 participants recruited from an Australian music store, who provided descriptions of their tattoos and piercings and completed measures of need for uniqueness, appearance investment and distinctive appearance investment. It was found that tattooed individuals scored significantly higher on need for uniqueness than non-tattooed individuals. Further, individuals with conventional ear piercings scored significantly lower on need for uniqueness than individuals with no piercings or with facial and body piercings. Neither appearance investment nor distinctive appearance investment differed significantly among tattoo or piercing status groups. Strength of identification with music was significantly correlated with number of tattoos, but not number of piercings. It was concluded that tattooing, but not body piercing, represents a bodily expression of uniqueness. © 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction Tattoos and piercings represent two increasingly common forms of body modification practices in contemporary society. Tattooing involves the insertion of coloured pigment into the dermal layer through a series of punctures of the skin in order to create a permanent marking. Currently, this is achieved using a rapid-injecting electrical device. Body piercing involves the insertion and threading of a metal bar or ring through an opening in the skin produced by a needle or specially designed piercing gun. In the past, both have been viewed as acts of rebellion or deviance associated with marginal groups in society (Benson, 2000). More recently, however, both have become increasingly popular across a broader segment of the population. Indeed, many celebrities now sport a visible tattoo or piercing. Although there are no definitive current incidence figures, an earlier large-scale Australian survey (Makkai & McAllister, 2001) reported that 10% of respondents had a tattoo, 32% had ear piercings and 7% had other body piercings. Smaller studies in the United States (Laumann & Derick, 2006) and Germany (Stirn, Hinz, & Brähler, 2006) have furnished similar estimates. More recently, a survey of more than 10,000 English adults estimated that 10% had a body piercing (Bone, Ncube, Nichols, & Noah, 2008), while in the United States, the Pew Research Center (2010) found that 23% of their sample had a tattoo and 8% a non-ear lobe piercing. In a recent German-speaking sample, 15% had a tattoo and 20% a body piercing (Stieger, Pietschnig, Kastner, Voracek, & Swami, 2010). In ∗ Corresponding author at: School of Psychology, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide, Australia. Tel.: +61 8 8201 2482; fax: +61 8 8201 3877. E-mail address: Marika.Tiggemann@flinders.edu.au (M. Tiggemann). 1740-1445/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.03.007 general, estimates are considerably higher in younger than older age groups. For example, among 18–29 year-olds (Millenials), 38% had a tattoo and 23% a body piercing (Pew Research Center, 2010). Parallel to this demographic shift over time, much of the earlier research focused on risk-taking behaviours, and concluded that tattooing and piercing were associated with behaviours such as smoking, alcohol consumption, shop lifting, traffic violations, drug use and other illegal activities (Armstrong, Roberts, Owen, & Koch, 2004; Brooks, Woods, Knight, & Shrier, 2003; Deschesnes, Fines, & Demers, 2006; Drews, Allison, & Probst, 2000; Forbes, 2001; Greif, Hewitt, & Armstrong, 1999; Roberts, Auinger, & Ryan, 2004). More recent research has also found associations between body modifications and earlier or more frequent sexual activity and a greater number of sexual partners (Koch, Roberts, Armstrong, & Owen, 2005, 2007, 2010; Skegg, Nada-Raja, Paul, & Skegg, 2007). Yet body modifications like tattooing (and to a lesser extent, piercing) are rarely performed impulsively and in fact tend to be carefully planned in advance, especially among adults (Forbes, 2001). Although tattooing and piercing do carry some health risks, such as infection, transmission of blood-borne diseases, and allergic skin reaction to the dye or metallic insert, Huxley and Grogan (2005) found no difference in health behaviours or health value between their tattooed and non-tattooed, or pierced and non-pierced, college student participants. Furthermore, although some studies find personality differences between body modification groups on traits such as agreeableness and sensation-seeking (Nathanson, Paulus, & Williams, 2006; Stirn et al., 2006; Wohlrab, Stahl, Rammsayer, & Kappeler, 2007), overall these differences can be judged as minor (Tate & Shelton, 2008). As remarked by Forbes (2001), when significant numbers of well-educated middle class people begin to display tattoos and piercings, it becomes difficult to maintain a view of 246 M. Tiggemann, L.A. Hopkins / Body Image 8 (2011) 245–250 these body modifications as signs of personal psychopathology or social marginalization. Some studies of college students have explicitly asked participants their motivations for getting a tattoo or piercing, although it should be noted that the samples of individuals with body modifications in these studies have been small. Greif et al. (1999) reported the most common reasons for both to be self-expression, followed by “just wanted one”, while Forbes (2001) reported selfexpression and “just like the looks of it” as the most common. In accord, Armstrong et al. (2004) concluded that the most popular reasons for getting a tattoo or piercing were based around selfexpression and identity, rather than deviancy or rebellion. There have been fewer studies of adults older than college students, but Millner and Eichold (2001) found that the most popular reasons given by a community sample recruited through tattoo and body art parlours similarly concerned individual expression and art. More recently, Tiggemann and Golder (2006) found that a sample recruited through tattoo studios nominated “to express myself” and “because they look good” as clearly the most important reasons for obtaining a tattoo. Nevertheless, there are a variety of other reasons for obtaining a tattoo or piercing, included group membership, celebration, perception of sexiness, and friends having one. Indeed, in their review of the literature, Wohlrab, Stahl, and Kappeler (2007) identified ten different motivational domains. As the literature above suggests that the most common motivations for tattooing and piercing are based around self-expression and a sense of identity or uniqueness, Tiggemann and Golder (2006) sought to apply the theoretical framework provided by the Theory of Uniqueness (Snyder & Fromkin, 1977, 1980; Snyder & Lopez, 2002). The term ‘uniqueness’ refers to a positive striving for different-ness compared to other people (Snyder & Fromkin, 1977). The basic premise underlying the Theory of Uniqueness is that, in addition to a need for similarity, people have a need to be distinctive and special. In fact, they seek to establish a moderate level of self-distinctiveness, because perceptual judgements of either extreme similarity or extreme dissimilarity to others are experienced as aversive. While everyone has a need (or desire) to be moderately dissimilar to others, the theory proposes that there are individual differences in this need (Snyder & Fromkin, 1980). Accordingly, people higher in the need for uniqueness will be more motivated to establish a level of perceived self-distinctiveness, for example, by obtaining or purchasing an item that is unique to them (Lynn & Snyder, 2002). Tiggemann and Golder (2006) reasoned that tattooing provides individuals with a means to achieve distinctiveness through body modification, and in support, found that tattooed individuals scored higher on need for uniqueness than non-tattooed individuals. This finding was also replicated by Tate and Shelton (2008) in a large college sample. Among nontattooed individuals, Tiggemann and Golder (2006) found need for uniqueness predicted future likelihood of getting a tattoo, with this relationship being largely mediated by need for a distinctive appearance. As tattooing is a permanent appearance-altering behaviour that requires considerable investment in terms of time, cost, and discomfort, Tiggemann and Golder (2006) also predicted that tattooed individuals would score higher on appearance investment than their non-tattooed counterparts. Appearance investment refers to the extent of cognitive, behavioural and emotional investments in the body and its importance for self-evaluation (Cash, 2002; Cash, Melnyk, & Hrabosky, 2004). However, contrary to their expectation, Tiggemann and Golder (2006) found no significant difference in appearance investment between their tattooed and non-tattooed participants. Although they speculated that perhaps the measure of appearance investment (ASI-R, Cash et al., 2004) captures primarily investment in “normative” aspects of appearance associated with current societal ideals of beauty such as weight and shape, a more obvious possibility, tested here, relates to the visibility and placement of tattoos. For example, an individual with a small discrete Chinese character tattooed on their hip and rarely seen by anyone else is unlikely to be motivated by appearance, in contrast to an individual who chooses a large readily visible dragon or mermaid tattooed on their forearm or side of their face. Thus we predicted that individuals with readily visible tattoos would score higher on appearance investment than individuals with easily concealed tattoos. While much of the literature has conceptualized tattoos and piercings as parallel modes of body modification, there are likely differences in their motivation and meaning. In fact, Wohlrab, Stahl, and Kappeler (2007) concluded their review by recommending that future research should investigate explicitly differences in motivation, a recommendation adopted by the present study. Specifically, we reasoned that tattooing is a practice that usually involves considerably more time, pain and cost than piercing, which can often be accomplished in a few seconds. Importantly, tattooing results in permanent body alteration, whereas piercings can usually be easily removed to enable the hole in the skin to heal over (Armstrong, Roberts, Koch, Saunders, & Owen, 2007). Finally, there are an almost infinite number of tattoo images that can be chosen or even individually designed by the bearer to be unique, in contrast to the more limited range of rings, studs and metal inserts available for piercings. Accordingly, as also remarked by Wohlrab, Stahl, and Kappeler (2007), tattoos are likely to be imbued with considerably more personal meaning than are piercings. The present study was conducted among shoppers in a music store. This setting was chosen as it was thought likely to give rise to a reasonable proportion of participants with and without body modifications, recruited from the same source and therefore directly comparable. It also allowed exploration of the relationship between musical identity and body modification practices. Like body modifications, styles of music can convey particular messages and act as a form of self-expression (Abbey & Davis, 2003). Certainly members of various youth sub-cultures (e.g., punk, Goth) display their membership by the music they listen to and the presence and form of their body art, in addition to their general dress, hair style and behaviour (Langman, 2008; Moore, 2009; Nathanson et al., 2006). In sum, the present study sought to investigate underlying motivations for tattooing and body piercing. Specifically, we hypothesized that tattooed and pierced individuals would score higher on need for uniqueness than their respective comparison non-tattooed and non-pierced counterparts. Second, we hypothesized that individuals with highly visible tattoos and piercings would score higher on appearance investment and distinctive appearance investment than individuals with less visible tattoos and piercings. Third, it was predicted that tattoos would be more motivated by self-expression and identity, relative to piercings which would be more related to general adornment. Finally, the relationship with music identity was explored. Method Participants Participants were 80 shoppers (29 men and 51 women) recruited in a music store in the Central Business District of Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia. Their mean age was 25.61 years (range 16–53, SD = 7.76). Of the 80 participants, 45 (56.3%) were tattooed, and 60 (75.0%) had at least one piercing, including pierced ears. M. Tiggemann, L.A. Hopkins / Body Image 8 (2011) 245–250 Measures Participants completed a questionnaire entitled ‘Music, Identity and Body Adornment’. The questionnaire contained measures of (in order) music preference, need for uniqueness, body modifications, reasons for body modifications, appearance investment and distinctive appearance investment. Music preference. Participants were provided with a list of 20 music styles (e.g., rock, metal, classical) and asked to indicate the genres that they listened to most frequently. They were asked which one of the above they identified with most strongly, and then to rate on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much) how important this style of music was to their identity. Extent of tattoos and piercings. Participants were first asked whether or not they had any tattoos (yes/no) and, if so, how many. Two participants who answered ‘lots’ were awarded a score of 30 (the highest actual score obtained). They then completed a grid which asked about the location (where is it?), imagery (what is it?), and size of their tattoo (space was provided for up to 8 tattoos). A similar set of questions and grid [excluding size] asked about piercings separately. As an accurate description of tattoos and piercings was integral to the study, the facing page depicted schematic outlines of the front and back views of a human figure, on which participants were asked to draw likenesses of their tattoos and piercings. From the drawings and descriptions, measures of visibility and percentage of body covered by tattoos were ascertained. Tattoo visibility, on the basis of the most visible tattoo, was classified on a 5-point scale (1 = rarely visible, 2 = only visible in underwear or bathers, 3 = visible in shorts, t-shirt and open shoes, 4 = visible in long pants, long sleeves and covered shoes, 5 = always visible). Both visibility and percentage of body covered by tattoos were coded by two independent judges, resulting in reasonable inter-rater reliability for both measures (visibility, r = .89; percentage body covered, r = .97). Reasons for obtaining tattoos and piercings. Participants with body modifications were asked to rate each of 20 possible reasons separately for their obtaining a tattoo and obtaining a piercing on 5-point scales from 1 (not a reason) to 5 (very strong reason). The list contained the 19 reasons used by Tiggemann and Golder (2006), with the addition of the item ‘to increase sexual pleasure’, as particularly relevant for intimate body piercing (Caliendo, Armstrong, & Roberts, 2005). Need for uniqueness. Need for uniqueness was measured by the Uniqueness Scale developed by Snyder and Fromkin (1977) to quantify individual differences in the desire to create and maintain a sense of uniqueness. This scale emphasises public and social displays of uniqueness (Lynn & Snyder, 2002). Participants rate 32 statements relating to need for uniqueness (e.g., “It bothers me if people think I am too unconventional”(R); “When I am in a group of strangers, I am not afraid to express my opinion publicly”) on a 5point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The total score is the sum of all 32 items (with appropriate recoding) and ranges from 32 to 160, with higher scores indicating greater need for uniqueness. Snyder and Fromkin (1977) reported test–retest reliabilities of .91 over two months and .68 over four months. In the current study, internal consistency was adequate (˛ = .79). Appearance investment. Investment in appearance was measured by the Appearance Schema Inventory-Revised (ASI-R) of Cash et al. (2004). This 20-item scale assesses beliefs or assumptions about the importance, meaning, and influence of appearance in 247 one’s life, and encompasses both the extent to which one’s appearance is important to self-worth (self-evaluative salience) and the motivation invested in maintaining or improving one’s appearance (motivational salience). Participants rate statements about appearance (e.g., “What I look like is an important part of who I am”) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The final score is the mean of the items (after some reverse coding). Thus scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater investment in appearance. Cash et al. (2004) reported good internal consistency for the total scale for both men (.90) and women (.88). In the current study internal consistency was similarly high (˛ = .87). Distinctive appearance investment. Investment in specifically a distinctive appearance was measured by the Distinctive Appearance Investment Scale of Tiggemann and Golder (2006). This consists of 6 items that address individuals’ desire to look different and to stand out (e.g., ‘Before going out, I make sure I look like an individual’). The scale was constructed to provide some integration of the concepts of need for uniqueness and appearance investment, i.e., to assess need for distinctiveness in specifically the appearance domain. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) and the final score is the mean of the items. Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher distinctive appearance investment. Tiggemann and Golder (2006) reported that the scale was uni-dimensional and had high internal consistency (˛ = .92). Further, scores were only modestly correlated with scores on need for uniqueness (r = .40, p < .05) and appearance investment (r = .19, p = .06), indicating that it was measuring a distinct construct. In the present sample, internal consistency was reasonable (˛ = .86). Procedure Participants were recruited via a notice displayed at the store counter of a music store situated in the Central Business District of a medium-sized city, Adelaide. This notice invited shoppers over the age of 18 years to participate in a study on music, identity and body adornment. Interested individuals were given a letter of introduction and a questionnaire which they completed either in the store or at home in their own time, and then returned by post in a sealed reply-paid envelope. Participants who wished were entered into a raffle for a $50 music store voucher. This procedure was approved by the University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee. Results Characteristics of the Sample Of the 45 tattooed participants, 19 were male and 26 were female. Most had one tattoo (n = 20), followed by two tattoos (n = 8). There was no significant gender difference in number of tattoos (men M = 6.53, SD = 10.52; women M = 3.42, SD = 4.85), t(43) = 1.33, p > .05, 2p = .04. The most common tattoo position was the upper arm (n = 18), followed by the back of the shoulder (n = 14), foot or ankle (n = 14), and wrist (n = 13). Tattoos covered a wide range of size and image: from a small (<1 cm) star on the thigh, to a 35 cm × 20 cm elaborate picture of an opened bible with wings, rose, olive wreath and wording on the chest. Forty percent (n = 18) of tattooed participants had tattoos that could be ‘easily concealed’ in that they were not able to be seen while wearing a t-shirt and shorts (visibility ratings of 1 or 2), while 60% (n = 27) had ‘readily visible’ tattoos that could be seen in this type of clothing (visibility ratings ≥ 3). The average percentage of body covered was signifi- 248 M. Tiggemann, L.A. Hopkins / Body Image 8 (2011) 245–250 Table 1 Mean scores for reasons for obtaining tattoos and piercings. Differences Between Tattooed Groups Tattoos (n = 45) Piercings (n = 60) Ear only Face/body They celebrate an occasion/person To feel independent To look attractive To express myself To be an individual To be unique To control my body To be fashionable To be creative Because they look good Because my friends are tattooed/pierced To rebel To look tough To feel better about myself To stand out in a crowd Because I like to take risks To feel mature To have a beauty mark To show commitment to a group To increase sexual pleasure 4.00 2.60 2.05 3.77 2.69 2.85 2.14 1.88 2.98 3.50 1.48 1.36 1.26 1.71 1.71 2.02 1.45 1.64 1.67 1.24 2.00 1.85 3.70 2.30 1.80 1.75 1.55 3.30 2.05 3.86 1.75 1.05 1.05 1.65 1.15 1.15 1.95 1.15 1.05 1.15 1.65 2.33 2.47 3.03 2.50 2.35 2.24 2.18 2.18 3.41 1.35 1.53 1.24 2.09 1.79 1.94 1.41 1.74 1.03 1.29 Note. Values above 3.00 are shown in bold. cantly greater for tattooed men (12.47%) than for women (4.75%), t(43) = 2.26, p = .029, 2p = .11. Of the 60 pierced participants, there were 46 women and 14 men. Of these, 17 women and 1 man had only (conventional) single soft ear lobe piercings. Another 8 participants (7 women, 1 man) had only multiple soft lobe or other ear piercings. The most common other piercings were of the nose (n = 12) and navel (n = 13). The mean number of piercings among pierced individuals was 4.10 (SD = 3.73), with no significant gender difference (men M = 2.57, SD = 1.95; women M = 4.57, SD = 4.03), t(58) = 1.78, p > .05, 2p = .05. Participants were classified into one of the three categories: none (n = 20), ear only (n = 26) [excluding ‘fleshies’ or ‘gauging’ in which a large circular disc is inserted in the ear lobe], and other facial or body piercing (n = 34). Only 3 participants had single body piercings (nipples, genitals) which were generally concealed; all other participants had piercings that were generally visible. Reasons for Body Modification Table 1 provides the mean scores for reasons for obtaining tattoos and piercings. It can be seen that, in general, a greater variety of reasons were endorsed for tattoos. The most common reasons for obtaining a tattoo were “they celebrate an occasion or person”, “to express myself” and “because they look good”, followed by “to be creative”. It is interesting to note that the reason “because they look good” seems to mean something different from “to look attractive” in this context. For piercings, participants were divided into those who had only ear piercings, and those who had other facial or body piercings. The most common reasons for ear piercing were “because they look good”, “to be attractive” and “to be fashionable”. For other piercings, the only moderately endorsed (>3.0) reasons were “because they look good” and “to express myself”. In order to test the prediction that tattoos would be relatively more motivated by self-expression than would be piercings, endorsement of the specific reason “to express myself” was compared for those rating their tattoos and for those rating their body piercings. As predicted, this reason was significantly more highly endorsed for tattoos (M = 3.77, SD = 1.12) than for body piercings (M = 3.03, SD = 1.29), t(75) = 2.70, p = .008, 2p = .09. Table 2(a) provides the means and standard deviations for need for uniqueness, appearance investment, and distinctive appearance investment for participants with no tattoos, easily covered tattoos and readily visible tattoos. Results were analysed by a univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with gender entered as a covariate. This covariate proved non-significant in this and the subsequent analyses. For need for uniqueness, there was a significant difference by tattoo status, F(2,76) = 4.10, p = .020, 2p = .10. Follow-up analyses confirmed what can be seen from the means. Participants with tattoos (both visible and concealed) had significantly higher need for uniqueness than participants without tattoos, respectively t(60) = 2.77, p = .007, 2p = .10, and t(51) = 2.23, p = .030, 2p = .06, with no significant difference between the tattooed groups, t(43) = 0.31, p > .05, 2p = .00. Across the whole sample, need for uniqueness was associated with number of tattoos, r = .27, p = .015, and percentage of body tattooed, r = .22, p = .047. In contrast, there was no significant effect of tattoo status on appearance investment, F(2,76) = 0.84, p > .05, 2p = .02. Likewise, although the pattern for distinctive appearance investment parallels that for need for uniqueness (see means in Table 2), there was no significant overall effect for distinctive appearance investment, F(2,76) = 1.54, p > .05, 2p = .04. Differences Between Pierced and Non-Pierced Participants Table 2(b) provides the means and standard deviations for need for uniqueness, appearance investment, and distinctive appearance investment for participants with no piercings, ear piercings only, and other facial and body piercings. There was a significant overall difference between groups on need for uniqueness, F(1,76) = 4.70, p = .012, 2p = .11. As can be seen in the table, here the difference lay with those with ear piercings only, who scored significantly lower on need for uniqueness than either individuals with no piercings, t(44) = 2.19, p = .034, 2p = .06, or those with facial and body piercings, t(58) = 3.43, p = .001, 2p = .14. There was no difference between individuals with no piercings and those with body piercings, t(52) = 0.83, p > .05, 2p = .01. The means also indicate that individuals with only ear piercings tended to score higher on appearance investment, but lower on distinctive appearance investment, than the other two groups. However, these differences were not statistically significant for either appearance investment, F(1,76) = 1.20, p > .05, 2p = .03, or distinctive appearance investment, F(1,76) = 1.81, p > .05. 2p = .05. Identification with Music The most commonly listened-to music genre was rock (79%), followed by alternative (56%), and pop music (54%). These were also the specific genres with which participants most frequently identified (respective ns = 16, 15, 10). Irrespective of musical genre, tattooed participants identified more strongly with their chosen musical style (M = 3.61, SD = 0.91) than did non-tattooed participants (M = 3.14, SD = 1.14), t(78) = 2.04, p = .045, 2p = .05. Further, among tattooed participants, strength of identification with music was significantly correlated with number of tattoos, r = .37, p = .012, visibility of tattoos, r = .36, p = .014, and percentage of body covered, r = .38, p = .010. In contrast, there was no significant difference in level of identification according to piercing status, F(2,77) = 0.70, p > .05, 2p = .02, and strength of identification was not significantly related to number of piercings among pierced individuals, r = .19, p > .05. M. Tiggemann, L.A. Hopkins / Body Image 8 (2011) 245–250 249 Table 2 Means (standard deviations in parentheses) for the dependent variables by (a) tattoo status, and (b) piercing status. (a) Tattoo status Need for uniqueness Appearance investment Distinctive appearance investment None (n = 35) Easily concealed (n = 18) Moderately visible (n = 27) 101.44 (12.94) 3.32 (0.60) 2.49 (0.71) 109.42 (11.14) 3.22 (0.80) 2.91 (0.80) 110.57 (12.72) 3.21 (0.67) 2.80 (1.02) (b) Piercing status Need for uniqueness Appearance investment Distinctive appearance investment None (n = 20) Ear only (n = 26) Face or body (n = 34) 107.88 (11.87) 2.97 (0.66) 2.76 (0.76) 99.50 (13.53) 3.39 (0.65) 2.40 (0.81) 110.61 (11.50) 3.22 (0.67) 2.87 (0.90) Discussion Taken together, the results of this study support the conceptualization of tattooing as a bodily expression of uniqueness. We replicated, in a quite different sample of shoppers at a music store, the previous findings of Tiggemann and Golder (2006) and Tate and Shelton (2008) that tattooed participants score higher on need for uniqueness than do their non-tattooed counterparts. The present study also found that this was irrespective of the degree of visibility of the tattoo. According to the Theory of Uniqueness (Snyder & Fromkin, 1980), which provided the theoretical framework for the present study, such need for uniqueness reflects a positive wish for different-ness, a wish to be distinctive and special. Hence this perspective sees tattooing as providing positive psychological benefit to the individual, rather than as indicating any maladjustment or pathology (Snyder & Lopez, 2002). In addition, this perspective is consistent with the reasons provided for obtaining a tattoo. The two most highly rated reasons, celebrating a person or event, and as a means of self-expression, clearly support Wohlrab, Stahl, and Kappeler (2007) suggestion that tattoos contain a great deal of personal meaning for the individual. The prominence of self-expression as an underlying motivation replicates the conclusions of a number of previous studies (Armstrong et al., 2004; Forbes, 2001; Greif et al., 1999; Millner & Eichold, 2001; Tiggemann & Golder, 2006). Here we also demonstrated, as predicted, that self-expression was a more highly endorsed motivation for obtaining a tattoo than a body piercing. A final supporting finding comes from the exploratory analysis of the relationship between musical identity and body modification practices. Not only did tattooed individuals identify more strongly with their chosen music genre than non-tattooed individuals, but among the former group, strength of identification correlated with number and visibility of tattoos, as well as percentage of body covered. Thus this finding offers a different and novel form of evidence that tattooing is related to issues of self-expression and identity. More generally, it supports the notion that styles of music and body art can both serve as mechanisms for constructing and presenting the self (Abbey & Davis, 2003; Langman, 2008; Moore, 2009). However, in contrast to our prediction, the results do not support the conceptualization of tattooing (or piercing) as investment in appearance. Although tattooing certainly does involve considerable investment in terms of time, cost and discomfort, and produces a permanent alteration to appearance, there was no significant difference in appearance investment between tattooed and non-tattooed participants. More tellingly, the lack of significant difference between readily concealed and visible tattoos confirms that tattooing is not really about appearance. In this light, reasons like “just like the looks of it” (Forbes, 2001) and “because they look good” (the present study), which previous research has simply assumed to reflect appearance motives (Tiggemann & Golder, 2006), need to be reinterpreted. Most likely these reasons tap the perceived beauty or creativity of the tattoo itself, rather than that of the bearer. Most previous research that has included both tattooing and piercings has treated them as more-or-less interchangeable forms of body art (e.g., Forbes, 2001; Greif et al., 1999; Millner & Eichold, 2001). However, the separate analyses here produced a different pattern of results, indicating that the underlying motivations and purposes served are likely to be different. Although there was a significant difference on need for uniqueness in piercing status groups, participants with facial or bodily piercings did not score more highly on need for uniqueness than did their non-pierced counterparts. Rather, it was participants with ear piercings only who scored significantly lower on need for uniqueness. This reflects the fact that soft ear lobe piercings have become a conventional form of body adornment, so much so that they are often not ‘counted’ as piercing at all (Bone et al., 2008; Stirn et al., 2006). As can be seen here, however, these participants do provide a very useful comparison group. Their endorsement of the reasons “to be fashionable” and “to look attractive” is consistent with ear piercings carrying much less individual meaning than tattoos (or other facial or body piercings). Overall, the results support Wohlrab, Stahl, and Kappeler (2007) suggestion that piercings as a whole have become less personally relevant and more of a fashion accessory than tattoos. More generally, the results also speak to the conceptualization and measurement of appearance investment. It does seem that the measure (ASI-R) is more sensitive to traditional or normative appearance investment in aspects of appearance such as weight, shape and societal ideals of attractiveness, and the degree to which these facets of appearance motivate people in their lives. The present results clearly indicate that these are not the facets that motivate individuals to obtain a tattoo. In accord, another study found no difference in the incidence of eating disorders between tattooed or pierced individuals and their non-tattooed or nonpierced counterparts (Preti et al., 2006). In this light, however, the lack of difference between tattoo (and piercing) status groups on distinctive appearance investment is more difficult to explain. One possibility is that having a tattoo or piercing satisfies the need for a distinctive appearance, in that it provides clear and tangible evidence that one is special and distinct, and perhaps therefore obviates the need to invest further time or effort into looking different. Both measures of appearance investment focus on on-going everyday grooming and behaviours, and so do not really encompass one-off behaviours like obtaining a tattoo or piercing. Future research might seek to further delimit the reach of the construct and measure of appearance investment (as well as distinctive appearance investment). The results need to be interpreted within a number of limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small and so the study may have been under-powered to detect significant results. Second, the sample was one of conveniences, restricted to shoppers in one particular music store. However, this strategy also allowed the 250 M. Tiggemann, L.A. Hopkins / Body Image 8 (2011) 245–250 recruitment of a non-college sample of both tattooed (or pierced) and non-tattooed (or non-pierced) individuals from a single source, in contrast to the few previous studies of adults which have often recruited tattooed participants from tattoo studios, and have therefore either had no comparison (non-tattooed) group (Millner & Eichold, 2001) or have had to recruit them from a separate source (Tiggemann & Golder, 2006). Further, unlike recruitment from a tattoo studio, participants were recruited in the context of music, and so any potential demand effects from a focus on body modification would have been minimized. Finally, the study used a cross-sectional correlational design and assessed participants at a single point in time. Thus, although it makes sense to think of need for uniqueness as a motivation for tattooing rather than vice versa, the study design cannot definitively establish whether particular motives or characteristics precede or are a consequence of tattooing. Despite these limitations, the study has contributed to a greater understanding of the motivations underlying body modification practices. It has clearly established tattooing as a bodily expression of identity and uniqueness, in a way that does not seem to be the case for body piercing. Accordingly, scholars interested in body art need to recognise that different forms of body modification may be differently motivated and carry different meaning. Tattooing, in particular, should be understood as providing the bearer with positive psychological benefit. Future longitudinal research might usefully address whether such psychological benefit is maintained over the longer term, particularly in the face of potential changes in identity. References Abbey, E., & Davis, P. C. (2003). Constructing one’s identity through music. In I. J. Josephs (Ed.), Dialogicality in development (pp. 69–86). Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood. Armstrong, M. L., Roberts, A. E., Koch, J. R., Saunders, J. C., & Owen, D. C. (2007). Investigating the removal of body piercings. Clinical Nursing Research, 16, 103–118. Armstrong, M. L., Roberts, A. E., Owen, D. C., & Koch, J. R. (2004). Contemporary college students and body piercing. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 58–61. Benson, S. (2000). Inscriptions of the self: Reflections on tattooing and piercing in contemporary Euro-America. In J. Caplan (Ed.), Written on the body (pp. 234–254). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Bone, A., Ncube, F., Nichols, T., & Noah, N. D. (2008). Body piercing in England: A survey of piercing sites other than earlobe. British Medical Journal, 336, 1426–1428. Brooks, T. L., Woods, E. R., Knight, J. R., & Shrier, L. A. (2003). Body modification and substance use in adolescents: Is there a link? Journal of Adolescent Health, 32, 44–49. Caliendo, C., Armstrong, M. L., & Roberts, A. E. (2005). Self-reported characteristics of women and men with intimate body piercings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49, 474–484. Cash, T. F. (2002). Body image: Cognitive behavioral perspectives on body image. In T. F. Cash & T. Pruzinsky (Eds.), Body images: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice (pp. 38–46). New York: Guilford Press. Cash, T. F., Melnyk, S. E., & Hrabosky, J. I. (2004). The assessment of body image investment: An extensive revision of the Appearance Schemas Inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 305–316. Deschesnes, M., Fines, P., & Demers, S. (2006). Are tattooing and body piercing indicators of risk-taking behaviours among high school students? Journal of Adolescence, 29, 379–393. Drews, D. R., Allison, C. K., & Probst, J. R. (2000). Behavioral and self-concept differences in tattooed and nontattooed college students. Psychological Reports, 86, 475–481. Forbes, G. B. (2001). College students with tattoos and piercings: Motives, family experiences, personality factors, and perception by others. Psychological Reports, 89, 774–786. Greif, J., Hewitt, W., & Armstrong, M. L. (1999). Tattooing and body piercing: Body art practices among college students. Clinical Nursing Research, 8, 368–385. Huxley, C., & Grogan, S. (2005). Tattooing, piercing, healthy behaviours and health value. Journal of Health Psychology, 10, 831–841. Koch, J. R., Roberts, A. E., Armstrong, M. L., & Owen, D. C. (2005). College students, tattoos, and sexual activity. Psychological Reports, 97, 887–890. Koch, J. R., Roberts, A. E., Armstrong, M. L., & Owen, D. C. (2007). Frequencies and relations of body piercing and sexual experience in college students. Psychological Reports, 101, 159–162. Koch, J. R., Roberts, A. E., Armstrong, M. L., & Owen, D. C. (2010). Body art, deviance, and American college students. Social Science Journal, 47, 151–161. Langman, L. (2008). Punk, porn and resistance. Current Sociology, 56, 657–677. Laumann, A. E., & Derick, A. J. (2006). Tattoos and body piercings in the United States: A national data set. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 55, 413–421. Lynn, M., & Snyder, C. R. (2002). Uniqueness seeking. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 395–410). New York: Oxford University Press. Makkai, T., & McAllister, I. (2001). Prevalence of tattooing and body piercing in the Australian community. Communicable Diseases Intelligence, 25, 67–72. Millner, V. S., & Eichold, B. H. (2001). Body piercing and tattooing perspectives. Clinical Nursing Research, 10, 424–441. Moore, R. (2009). Sells like teen spirit: Music youth culture and social crisis. New York: New York University Press. Nathanson, C., Paulus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2006). Personality and misconduct correlates of body modification and other cultural deviance markers. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 779–802. Pew Research Center. (2010). Millenials: A portrait of generation next. Retrieved from. http://www.pewresearch.org/millenials Preti, A., Pinna, C., Nocco, S., Mulliri, E., Pilia, S., Petretto, D. R., et al. (2006). Body of evidence: Tattoos, body piercings, and eating disorder symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61, 561–566. Roberts, T. A., Auinger, P., & Ryan, S. A. (2004). Body piercing and high-risk behaviour in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34, 224–229. Skegg, K., Nada-Raja, S., Paul, C., & Skegg, D. C. G. (2007). Body piercing, personality, and sexual behaviour. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 36, 47–54. Snyder, C. R., & Fromkin, H. L. (1977). Abnormality as a positive characteristic: The development and validation of a scale measuring need for uniqueness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86, 518–527. Snyder, C. R., & Fromkin, H. L. (1980). Uniqueness: The human pursuit of difference. London, New York: Plenum Press. Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2002). Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. Stieger, S., Pietschnig, J., Kastner, C. K., Voracek, M., & Swami, V. (2010). Prevalence and acceptance of tattoos and piercings: A survey of young adults from the southern German-speaking area of central Europe. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 110, 1065–1074. Stirn, A., Hinz, A., & Brähler, E. (2006). Prevalence of tattooing and body piercing in Germany and perception of health, mental disorders, and sensation seeking among tattooed and body-pierced individuals. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60, 531–534. Tate, J. C., & Shelton, B. L. (2008). Personality correlates of tattooing and body piercing in a college sample: The kids are alright. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 281–285. Tiggemann, M., & Golder, F. (2006). Tattooing: An expression of uniqueness in the appearance domain. Body Image, 3, 309–315. Wohlrab, S., Stahl, J., & Kappeler, P. M. (2007). Modifying the body: Motivations for getting tattooed and pierced. Body Image, 4, 87–95. Wohlrab, S., Stahl, J., Rammsayer, T., & Kappeler, P. M. (2007). Differences in personality characteristics between body-modified and non-modified individuals: Associations with individual personality traits and their possible evolutionary implications. European Journal of Personality, 21, 931–951.