Chinese Students' Beliefs on Collaborative Learning & Teacher Role

advertisement

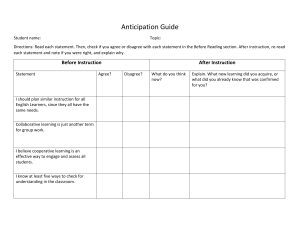

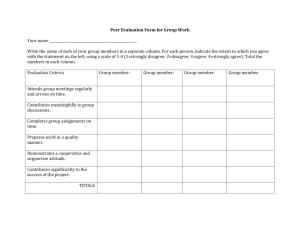

PRC SCHOLARS’ BELIEFS IN COLLABORATIVE LEARNING, PEER FEEDBACK AND THE ROLE OF THE TEACHER ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Ever since the communicative approach to language learning became extremely popular, collaborative learning has become a major movement in mainstream education. This is because group work not only provides opportunities for input that is modified by interaction and negotiations, it also creates a low anxiety context and provides a chance for language practise and comprehensible output. However, many assumptions behind collaborative learning, particularly those related to the desirability of learner autonomy are framed on ‘Western’ ideas of learning. What holds true in L1 teaching settings may not apply in the ESL context as these students from different cultural backgrounds may have perceptions and attitudes that are different from their Western counterparts. Students’ preferences cannot be ignored as the beliefs and attitudes they hold have a profound influence on their learning behaviours. This paper reports on a research project carried out at a university in Singapore. The aims of this study are to examine Chinese students’ views on collaborative learning, peer feedback and the role of the teacher. A questionnaire consisting of 30 statements were administered to 144 Chinese students. The findings suggest that most of them are motivated and enjoy working in groups, the reasons being that collaborative learning is fun, makes the students feel more relaxed and also helps them to think of better ideas. In addition, the students are both confident and receptive to giving and receiving peer feedback. However, they are unsure whether the teacher should be the authoritative figure 1 in class, though most of them obey their teacher’s instructions and expect her to be responsible in assessing their progress. 2 Introduction From December 1993, some five hundred students from the People’s Republic of China arrive in Singapore every year to study at the National University of Singapore and the Nanyang Technological University under the Ministry of Education scholarship scheme. These students have a choice of either engineering or computer-related courses; two key disciplines identified by the Singapore government to be lacking in skilled manpower. Upon completion of their degree, the students are bonded and are expected to work in Singapore in any field or sector for a minimum of six years. Unlike universities in UK, USA, Australia or New Zealand, the universities here do not insist on a minimum IELTS or TOEFL score. Instead these Chinese scholars are admitted purely on the grounds of their academic excellence. Both the National University of Singapore and the National Institute of Education run a six-month intensive language programme specially tailored for these Chinese scholars before they begin their degree courses. The aim of this six-month intensive English for Academic Purposes programme is to raise the students’ English proficiency and communication skills. This bridge course is offered to the Chinese scholars because a good command of the English Language is vital to their success in their education in Singapore. Unlike the Singapore education system where English is used as the medium of instruction, English is taught only as a foreign language in the People’s Republic of China. There, students 3 only begin to learn English when they enter middle school. However, according to Goh (1998), this situation is slowing changing. Some schools in the bigger cities have started to introduce English as a subject for students at Primary 4. English is also taught in a handful of “experimental schools” in the first year of primary education. The Importance of the Study The rationale for this study is the desire to better understand and meet the needs of Chinese students. The reasons for the use of collaborative learning and its benefits will be discussed in detail in the literature review section. However, it must be stressed that these benefits can only be reaped if students regard group work as a valuable learning tool. As for the role of the teacher, studies by Bergman (1984), Haughton and Dickinson (1988) and Kumaravadivelu (1991) provide evidence showing mismatch occurring in classrooms due to differing perceptions of the roles of teachers and learners held by teachers and learners, respectively. Learners’ expectation of teacher authority and as the source of knowledge can be problematic for teachers who desire their learners to assume responsibility for their learning (Cotterall, 1995). With regard to peer feedback, the evidence is less conclusive. Zhang (1995) argues that although there are benefits to be reaped from peer feedback in the L1 context, what holds true in L1 settings may not apply to the ESL situation. In fact, he finds that ESL students have a strong preference in obtaining feedback from their teachers than from their peers. However, in various studies carried out on Taiwanese and Hong Kong university students in writing courses, Jacobs et al (1998) finds that these students’ preference from 4 obtaining feedback from teachers is not overwhelming. While these students preferred teacher feedback, they also valued peer feedback. It is hoped the PRC students studying in Singapore will have a more enriching and beneficial learning experience if their needs were better understood and met, which is the prime motivation of this study. Aim and Research Questions The aim of this study is to investigate Chinese students’ beliefs in the following areas: collaborative learning peer feedback the role of the teacher The research questions are: 1. Do students like to participate in collaborative learning? If so, what are their reasons for doing so? 2. Is peer feedback a valuable learning strategy to the students? 3. What is their opinion of the role of the teacher? Having provided the background information, rationale and aim of this study, a section on literature review is presented next. Following this, information on the participants and the method used in collecting data are provided. The findings and discussion will then be considered collectively. From this, conclusions are drawn, out of which several recommendations are made. 5 Literature Review Since the communicative approach to language learning came into vogue, collaborative learning has become a major movement in mainstream education. As defined by Nunan (1992: 3), collaborative learning is said to take place when students work together to achieve some common learning goals. In this study, the terms ‘group work’, ‘collaborative learning’ and ‘cooperative learning’ are used interchangeably although Jacobs (1998) does make a distinction between traditional group activities and cooperative learning. The main difference between CL [cooperative learning] and traditional group activities is that traditionally students were given a task and asked to work on it in groups with no attention paid to group functioning. Whereas, with CL, educators’ attempt to maximise the effectiveness are informed by what theory and research say, filtered through each educator’s own beliefs, experiences, and context. In other words, the difference is between just asking students to work together and carefully preparing, planning, monitoring, and intervening. Jacobs (1998: 179) In particular, Jacobs (1998) illustrates the contrast between traditional group activities and cooperative learning in terms of: Group formation Seating arrangements Collaborative skills Duration of groups Group solidarity Individual participation and learning Teachers’ roles and Solidarity beyond the group 6 For a fuller discussion, please refer to Jacobs (1998), Sharan (1980) and Slavin (1990). Among the several advantages of collaborative learning, one commonly cited reason is that group work provides opportunities for input that is modified by interaction and negotiations. Another is that it creates a low anxiety context and provides a chance for language practise and comprehensible output (Long and Porter, 1985; Pica, Young and Doughty, 1987; Swain and Lapkin, 1989; Wong-Fillmore, 1991). It is beyond the scope of this paper to provide an extensive review of the benefits of collaborative learning and under the kinds of conditions these benefits can be achieved. Neither is it the aim to enter into a debate as to whether the benefits of group work can only be realised if all or some of these conditions are met. My prime concern here however, focuses on the mismatch that can occur between the expectations of teachers and learners in terms of the learner’s and the teacher’s role, respectively. Group activities to a large extent, require learners to work independently of the teacher. Thus, there is a need for learners to become autonomous and to re-define their views of the role of teacher and learners (Ho and Crookall, 1995). However, the development of learner autonomy must be considered within the framework of culture. This is because the way learners interact and whether they feel comfortable interacting in class depends on broad social and cultural factors (Sullivan, 1996). Many assumptions behind collaborative learning, particularly those related to the desirability of learner autonomy are framed on ‘Western’ ideas of learning (Liu, 1998; 7 Roskams, 1999). Indeed, to speak of ‘Western’ cultures of learning is to generalise (Jin and Cortazzi, 1998:102). But the vast majority of Chinese still believe that ‘Western’ cultures of learning share a different set of norms, perceptions and ideals from theirs, even though real differences do exist between native speakers from different countries (Jin and Cortazzi, 1998). The Chinese culture of learning a language can be thought of as being fundamentally concerned with the mastery of knowledge of grammar and vocabulary, mainly from the teacher and textbook (Cortazzi and Jin, 1996). On the other hand, in current Western cultures of learning, the social and pedagogic relations are thought of in quite different terms. The major focus is on the development of skills for communication and much attention is paid to learning contexts and the students’ needs. Student participation and classroom interaction are ways to help learners develop skills related to the functions and uses of languages (Jin and Cortazzi, 1998: 103). Collaborative learning activities such as group discussion in class may be positively valued by Western cultures of learning. But according to Jin and Cortazzi (1998: 104) many Chinese students consider group discussions to be fruitless and a waste of time as they risk learning errors from their peers. In order to use class time with the teacher to the best advantage, the students prefer that group language practice should only be carried out after class. 8 Asian students are also often perceived as passive and coming from a culture with a long tradition of unconditional obedience to authority. The teacher is expected to take charge, is seen to be providing the source of learning and regarded as a fount of knowledge rather than a facilitator (Liu, 1998). One explanation for this stems from the teaching of Confucius which is still influential today (Louie, 1984). The verb ‘teach’ in Chinese is ‘jiao shu’ which means ‘teach the book’. The teacher and textbook are thus regarded as authoritative sources of knowledge (Cortazzi and Jin 1998: 102). Another explanation offered by Jin and Cortazzi, (1998) is that Chinese learners’ hold a different perspective with regard to the term, ‘active participation’. Despite remaining quiet in class, they thought of themselves as actively participating by listening, thinking, and by asking questions and discussing with peers after class. Chinese students preferred to remain quiet and not raise any questions in class because they were shy or afraid of making mistakes. Furthermore, they didn’t want to lose face by asking foolish questions. What is considered even more unacceptable is that their questions may be too difficult for the teacher to answer, causing the teacher to lose face. In their view, a good teacher is one who is able to predict questions and answer them unasked. One important issue which has been raised in collaborative learning is the tension between the social unacceptability of public disagreement in many cultures versus the need for honest feedback for peer learning to take place. If students come from a culture 9 where they are taught the importance of maintaining group harmony, then the full benefits of collaborative learning, such as peer feedback, cannot be fully exploited. This is because these students may be unwilling to give honest feedback to their classmates for fear that this may affect their relationship with one another. Taking into account the contrastive view between Western and Chinese cultures of learning, Roskams (1999:83) reiterates that “cultural beliefs and assumptions have an important influence on learning outcomes because they exert an importance influence on learning behaviour including the social dimensions of learning which are obviously important in collaborative tasks”. It is thus not difficult to appreciate the need and importance in finding out our learners’ views and beliefs before a particular classroom strategy is adopted, since whether a learning activity is beneficial or not, depends on whether the learners involved in such a learning activity accept it as a valid and valuable means of learning. To sum up in Cotterall’s (1995: 195) words, “the beliefs and attitudes learners hold have a profound influence on their learning behaviours”. Having reviewed some literature which contrasts the views between Western and Chinese cultures of learning, a small scale empirical study which I carried out to better understand the needs of Chinese students is presented in the next section. The Empirical Study For the academic year beginning December 2001, a total of 168 Chinese students who have completed their Senior Middle School were offered scholarships to study in 10 Singapore. These students who mainly come from provincial areas, had in fact been admitted to universities in China, after completing the demanding and rigorous National College Entrance Examination. However, they decided to give up their place in China when offered the chance to study here. The students involved in this study only began learning English when they entered middle school. English is taught as a foreign language where on average, the students received about 50 minutes a day of English instruction. According to Kohn (1992: 115), much emphasis is placed on the teaching of grammar rules, the close reading of texts and the use of translation exercises in the teaching of English in foreign language classrooms in China. The practice of close reading of texts has prompted learners to pay careful attention to detail and to try to understand every word. Huang (1991) also observed that many middle school English learners have the habit of translating what they read into Mandarin. At the National Institute of Education, these students are put through a six-month intensive English for Academic Purposes programme, with an average contact time of 25 hours per week. It aims to help PRC students communicate more confidently and effectively in all skill areas for everyday purpose and develop communication and learning skills needed for academic purposes 11 The programme is organised around the four core skills: listening, speaking, reading and writing. The modules are: Introduction to Computer Skills Academic Oral Communication/ Listening & Speaking Academic Reading Comprehension Academic Writing Skills Tutorial/ Self Access In order to cultivate learner independence, a one-hour weekly session is scheduled for students to visit the Self-Access Lab. Computers, audio-visual equipment and software as well as books are available to them for self-study purposes. With regard to assessments, the students are gauged mainly through class assignments, projects and tests. A pre- and post-test is administered at the beginning and the end of the programme, respectively. A mid-semester test is also administered to provide teachers and students feedback regarding the students’ progress at the end of the first term. Method Based on the results of a pre-test that was conducted at the beginning of the course, eight students whose scores were in the mid-range, were selected for the pilot test. The reason for selecting these students for the pilot study is that they are deemed to be a fairer representation of the entire cohort, in terms of their language proficiency. 12 Before the students attempted the questionnaire, they were told to circle or underline words, phrases or sentences in which the meanings were vague or unclear. At the end of the session when all the students had completed the questionnaire, they were asked to elaborate on the reason(s) why those highlighted portions presented problems. Alternative words and paraphrases were suggested and these students were consulted as to whether these alternatives were clearer and less ambiguous. After gathering feedback from these eight students, the following minor amendments were made to the questionnaire (refer to Appendix A). 1. Question 7 – ‘When working in groups, I like to help maintain a friendly and harmonious atmosphere.’ was rephrased as ‘I like to help maintain a friendly and good working relationship when working in groups.’ 2. Question 15 – ‘In class, I will not challenge the teacher’s authority.’ was rephrased as ‘In class, I usually obey my teacher’s instructions.’ 3. As for questions 17, 27 and 30, the word, ‘comments’ was added next to the term, ‘feedback’ in parenthesis. The nature of the study and the venue in which the study was to take place was made known to the students one week earlier. In a bid to encourage the students to participate in the study, it was stressed that their identity would remain anonymous and their responses kept confidential. A written consent was also obtained from them and this was collected separately from the completed questionnaire. 13 Excluding the eight who took part in the pilot study, 144 out of the remaining 160 students took part in the study, giving an overall response rate of ninety per cent. Three students’ responses, however, had to be discarded; two students missed out the second page of the questionnaire and another gave a ‘neutral’ response to all the sixteen questions in the second page of the questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of thirty sentences in random order. The students were asked to indicate whether they ‘strongly agreed’, ‘agreed’, ‘neutral’, ‘disagreed’ or ‘strongly disagreed’ with each of the statements. In addition, they were encouraged to write any additional comments they have on group work, peer feedback and the role of the teacher at the end of the questionnaire. A descriptive analysis was performed on the data using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS). Limitation The research design of this study was simple in that it consisted of a questionnaire survey. One flaw of questionnaires is that they often reveal ‘publicly acceptable’ beliefs rather than true beliefs or actual behaviour. Despite this, it is thought to be the most economical method of administrating a large-scale study. Furthermore, group dynamics do not lend itself easily to scrutiny. No accurate conclusion can be made through direct observation, as to whether a student’s refusal to participate in a group discussion is the result of his reluctance, selfishness, lack of ability or that the student was simply taking 14 the time to think, analyse and reflect on the discussion. With regard to the use of interviews and journals, the same problem as the questionnaire surfaces since subjects can simply respond with only ‘acceptable’ answers. Results and Discussion The findings of the study are discussed and presented here. It is divided into four main sections. The first section discusses the students’ views on collaborative learning. This is followed by a discussion of their views on peer feedback and the role of the teacher. As mentioned earlier, the students were also encouraged to write any additional comments they have on group work, peer feedback and the role of the teacher at the end of the questionnaire. Their comments are summarised and presented in the last section. i. Collaborative Learning The students’ views on collaborative learning in terms of their attitude, preference, reasons, motivation and relationship are summarized and presented in this section. Table 1. Attitudes towards collaborative learning Statement Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 1. I like activities where 2. I like being part of a 4. I prefer to work alone. there is a lot of group working towards discussion with my some common goal(s). classmates in small groups (of between 3 and 5 students). 0 0 18 (12.8%) 4 (2.8%) 3 (2.1%) 41 (29.1%) 17 (12.1%) 21 (14.9%) 59 (41.8%) 78 (55.3%) 77 (54.6%) 16 (11.3%) 42 (29.8%) 40 (28.4%) 7 (5%) 15 In table 1 above, 85.1% and 83% of the students agreed or strongly agreed with statements 1 and 2 respectively. As for statement 3, 41.9% of the students disputed with it while 41.8% of them were either indifferent or unsure of their response. Based on these figures, it can be concluded that the students are generally keen and have a positive attitude towards collaborative learning. This could perhaps be attributed to a number of reasons. First, when working in groups, students engage in discussion with one another, thereby providing them more opportunities to use the language (Long and Porter, 1985). Second, working in groups also give them a sense of belonging and identity as the students work towards some common purpose. Although the benefits of collaborative learning have been recognised, there are limitations associated with it as well. Two of the common problems are social loafing and the division of labour (Jacobs, 1998; Roskams, 1999). Based on their experiences working in groups, the students could have been aware of the problems associated with collaborative learning, which perhaps explain why a significant number (41.8%) of them turned in a neutral response. Table 2(i). Preference for collaborative learning Statement Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 5. I don’t like working in a group because I usually end up doing most of the work. 19 (13.5%) 87 (61.7%) 25 (17.7%) 7 (5%) 3 (2.1%) 6. I don’t like working in a group because my friends do not put in as much effort as I do. 31 (22%) 81 (57.4%) 21 (14.9%) 8 (5.7%) 0 16 In table 2 (i) above, it can be concluded that the students prefer to work in groups despite being aware of common problems associated with collaborative learning such as the unfair division of work. More than three-quarters of the students disagreed with the above two statements. Table 2(ii). Preference for collaborative learning Statement 18. I enjoy working in groups because it is fun. 19. I enjoy working in groups because I feel more relaxed. Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 2 (1.4%) 13 (9.2%) 31 (22%) 67 (47.5%) 28 (19.9%) 3 (2.1%) 23 (16.3%) 35 (24.8%) 57 (40.4) 23 (16.3%) 20. I feel more comfortable in voicing my views in group discussions than in front of the entire class. 4 (2.9%) 9 (6.5%) 45 (32.4%) 67 (48.2%) 14 (10.1%) In addition, as shown in table 2 (ii) on the following page, 67.4% of the students find working together to be fun while 56.7% of them regard group work as relaxing. 58.3% of them also feel less threatened compared to the situation in which they have to answer a question in the presence of the teacher and the entire class. Table 3. Reasons for engaging in collaborative learning Statement Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 8. Working in groups helps me to think of better ideas. 2 (1.4%) 4 (2.8%) 24 17%) 71 (50.4%) 40 (28.4%) 9. Working in groups helps me score a better grade. 2 (1.4%) 11 (7.8%) 47 (33.3%) 64 (45.4%) 17 (12.1%) 10. Working in groups slow me down. 20 (14.3%) 88 (62.%) 25 (17.9%) 7 (5%) 0 11. Working in groups helps me learn better. 0 2 (1.4%) 35 (24.8%) 79 (56%) 25 (17.7%) 17 As shown in table 3 above, most students also believe that working together with their peers can help them achieve better results as they can think of better ideas, which in turn facilitate their learning. Even though they have to discuss and consult with one another, 76.3% of them believe that this does not slow them down in the completion of their work. Table 4(i) Motivation towards collaborative Learning Statement 12. I am willing to work hard even though my own success benefits other students as well me. Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 0 3 (2.1%) 20 (14.2%) 79 (56%) 39 (27.7%) 28. I will not want to contribute any valuable knowledge/ideas during a class discussion for fear that my classmates will score a better grade than I. 48 (34.3%) 76 (54.3%) 6 (4.3%) 7 (5%) 3 (2.1%) Table 4(i) above shows that most students are motivated to work hard even though their effort benefits others as well as themselves. The tendency for social loafing is therefore minimised. Most of them (83.7%) claim that they would not be inhibited in contributing towards the completion of the group task, even though this success benefits others. This finding is consistent with Salili’s (1996) in that Chinese students are more motivated when working together. They also work harder in groups and they exhibit less social loafing than their American counterparts. A significant 88.6% of them claimed that they are unfazed that their ideas or contribution will result in their peers scoring a better grade than them. 18 Table 4(ii) Motivation towards collaborative Learning Statement Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 13. I will put in extra effort in a group project if all the group members were not awarded the same grade. 1(0.7%) 7 (5%) 46 (32.6%) 67 (47.5%) 20 (14.2%) 22. I don’t mind getting the same grade as the other members when we work as a group. 1(0.7%) 10 (7.1%) 33 (23.4%) 82 (58.2%) 15 (10.6%) 23. Each group member could be given a different grade even though we work as a group. 5 (3.5%) 18 (12.8%) 38 (27%) 57 (40.4%) 23 (16.3%) Table 4(ii) above indicates that the students are somewhat indifferent or do not have a strong opinion as to whether all the group members working in the same project should obtain the same grade. 68.8% of the students do not mind being awarded the same grade as their peers while 56.7% believe that the teacher could consider awarding each group member a different grade despite it being a group effort. However to spur them to work harder, the teacher could consider awarding different grades to different students when students engage in a group project as 61.7% of them claim that they will work harder if this grading system was implemented. Table 5. Relationship in Collaborative Learning Statement Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 3. It is more important for me to score a good grade than to form a good relationship with my classmates. 36 (25.5%) 52 (36.9%) 35 (24.8%) 15 (10.6%) 3 (2.1%) 7. I like to help maintain a friendly and good working relationship when working in groups. 0 5 (13.5%) 5 (13.5%) 85 (60.3%) 46 (32.6%) 24. I feel comfortable to disagree with my classmates during group discussions. 3 (2.1%) 27 (19.1%) 57 (40.4%) 45 (31.9%) 9 (6.4%) Table 5 above indicates that for 62.4% of these Chinese scholars, forming a good relationship with their classmates is their priority. In addition, an overwhelming 92.9% of 19 them are keen to maintain a friendly and harmonious atmosphere when working in groups. This is not surprising since all of them are overseas students. As such, many of them are keen to maintain their newly formed friendships which explains why a significant number, 40.4% of them are somewhat unsure as to whether they feel comfortable to disagree with their peers during group discussions. Similar results were also obtained in an earlier study that I conducted (Chia, 2000) involving fee-paying Asian students who were studying in a university in New Zealand. The keenness to form good relationships with peers can pose a problem when the students are made to engage in collaborative learning. This is especially so if the maintenance of group harmony is at the expense of disagreement, giving negative feedback and expressing opposing views. The full value of collaborative learning cannot then be realised, as one of the aims is for the students working as a group, to examine their different views. This is a real issue that confronts students as Johnson (1995) found that before commencing group work, a few of his students expressed apprehension with the following statement: “We may disagree with each other”, implying that any disagreement which occurs in collaborative learning is negative. 20 ii. Peer Feedback The students’ views on peer feedback of their confidence level and truthfulness in providing feedback, as well as their views on teacher feedback are summarized and presented in this section. Table 6. Confidence in peer feedback Statement 25. I feel confident giving my group members feedback (comments) on their work. Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 1 (0.7%) 10 (7.1%) 52 (36.9%) 71 (50.4%) 7 (5%) 26. I am confident that my group members are capable of providing me with feedback on my work. 0 8 (5.7%) 49 (34.8%) 73 (51.8%) 11 (7.8%) 30. The feedback provided by my groups members on my work is helpful 2 (1.4%) 3 (3.5%) 21 (14.9%) 91 (64.5%) 24 (17%) Table 6 above shows that 55.4% of the students express confidence in giving feedback to their peers while 59.6% of them are confident with regard to their peers’ ability to give them feedback on their work. 81.5% also find peer feedback useful. Table 7. Truthfulness in providing feedback Statement Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 27. I will only give negative feedback to my group members whom I know well. 14 (9.9%) 78 (55.3%) 34 (24.1%) 13 (9.2%) 2 (1.4%) Despite indicating that they are keen to maintain a good working relationship with their peers when working in groups, table 7 above shows that almost two-thirds (65.2%) of the students are willing to give honest negative feedback to their peers. 21 As mentioned earlier, the willingness to provide honest negative feedback is important as one of the aims of collaborative learning is to allow students to explore different viewpoints which require a certain degree of frankness. Table 8. Feedback from teacher Statement Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree 17. I prefer to get feedback on 29. I believe my teacher’s my work from my teacher than feedback on my language from my group members. learning is most helpful. 10 (7.1%) 23 (16.4%) 54 (38.6%) 45 (32.1%) 8 (5.7%) 1 (0.7%) 11 (7.8%) 34 (24.1%) 78 (55.3%) 17 (12.1%) The students do not exhibit an overwhelming preference in obtaining feedback from their teacher, as only 37.8% of them indicated that they prefer this. Despite this, 67.4% of them believe that feedback obtained from the teacher regarding their language is most the helpful. The above findings could be explained by the following reasons. First, these students may hold the view that whether the feedback comes from the teacher or their peers, obtaining another viewpoint and getting some feedback is better than none. Second, they could have realised that with a class of more than twenty students, it is impossible for the teacher to be providing them with individual feedback throughout their group discussion. In his study on Chinese EFL students’ attitudes to peer feedback and peer assessment, Roskams (1999:92) also obtained similar findings. He found that although most Chinese students preferred teacher feedback to partner feedback, this does not imply that the students did not value peer feedback. The findings obtained from this study and that of Roskams’s (1999) seem to contradict that of Ho and Crookall’s (1995), 22 who believe that one difficulty in implementing collaborative learning in a Chinese setting is due to the students’ preference in getting feedback from their teacher. iii. Role of the Teacher The students’ views on the role the teacher assumes are summarized and presented in this section. Table 9. Role of the Teacher Statement 14. I expect the 16. I believe that teacher (rather the teacher is than myself) to be responsible for responsible for imparting assessing how knowledge to me much I have learnt. rather than having to discover it myself. Strongly Disagree 5 (3.5%) 11 (7.9%) Disagree 15 (10.4%) 49 (35%) Neutral 33 (23.4%) 53 (37.9%) Agree 67 (47.5%) 24 (17.1%) Strongly Agree 21 (14.9%) 3 (2.1%) 15. In class, I usually obey my teacher’s instructions. 0 12 (8.5%) 22 (15.6%) 86 (61%) 21 (14.9%) 21. In class, I see the teacher as someone in charge. 6 (4.3%) 32 (22.7%) 56 (39.7%) 43 (30.5%) 4 (2.8%) The students’ responses in Table 9 show that there is a tendency for the students, almost two-thirds (62.4%), to expect their teacher to assess their progress. Littlewood (2000) also found that Asian students have a slightly stronger preference for the teacher to play a greater role in evaluating their learning. However, a significant number are either unsure (37.9%) or disagree (42.9%) that the teacher should be the sole provider of learning. This is inconsistent with the findings of Liu (1998) and Forestier (1998) on Asian students, where the teacher is expected to be the source of knowledge. Although more than threequarters (75.9%) indicated that they are willing to obey the teacher’s instructions, the 23 students are however, unsure that the teacher should be the authoritative figure in the classroom, with 33.3% agreeing with the statement and 39.7% unsure of their response. Additional Comments Other than having to respond to thirty statements, the Chinese students were asked for their additional comments regarding group work, peer feedback and the teacher of the teacher. Their responses are summarized below. i. Group Work The following paragraph discusses the other reasons that the students mentioned as to why they are keen to participate in group discussion and the advantages associated with group activities. One reason for favouring group work is that the students believe that working collaboratively prepares them for the future. As a result of the one-child policy in China, the majority of the students come from families in which they are the only child. Perhaps they are aware that they lack opportunities to interact with others and thus view group work as a way of enhancing their social skills. Furthermore, the students will begin their mainstream degree course in six months’ time and are perhaps anxious, since they have to work with both Singapore students and other foreign students. Working in groups can also better prepare them for the work situation where teamwork is the norm. 24 Another common reason mentioned by the students is that group work is a good way of getting to know peers well. By working towards some common goal, they regard this as a way of building solidarity among them. On the practical aspect, the students also cited division of labour as another compelling reason for favouring group work. Roskams (1999) also found that many of his Chinese students were fairly pragmatic about this aspect of collaborative learning. The other reasons for collaborative learning include more opportunities to practise English, learning from others and helping one another. By being able to express their views freely and in a more relaxed manner also help them improve their confidence. Despite these advantages, the students have some reservations as well. They claimed that not of all them know how to participate in group work. They also see it as the teacher’s responsibility to teach them how to participate in group work in order to prevent the discussion from being dominated by a few students. The other problems stated are unfair division of workload, loafing and selfishness. In addition, the students believe that it is important that the teacher allocate adequate time for discussion and that time should be given for the students to plan and reflect individually so as to better prepare themselves before they get together in their group activities. Many students also expressed apprehension in group activities as many of them have a tendency to use Mandarin in their discussions. There isn’t an easy solution to this problem as language choice and use is closely related to one’s identity. As one student 25 aptly puts it, “It is unnatural for me to use a foreign language such as English to converse with my friends”. ii. Peer Feedback Peer feedback is also highly valued by most as it acts as a mirror as to whether the students are heading in the right direction. Not only can peers help to point out one another’s shortcomings, it is also a good learning experience as one learns through teaching others. One potential conflict however is that students may not know how to handle different in points of view. In a student’s words “When I do not agree with my friends’ point of view, I just do things in my own way”. Another area is the lack of time. A student cited that he does not wish to have to rush through giving and receiving feedback from his peers. As teachers, we have to help students to manage their time or be more focused so that they concentrate only in giving feedback on some areas. iii. Teacher’s Role The most commonly expressed view is that a teacher should be more of a friend than a ruler. Related to this are qualities of a teacher such as not being too strict and that of an adviser rather than a rule-enforcer. Though she is a source of knowledge, a teacher shouldn’t spoon-feed. Instead she is expected to guide students in discovering knowledge for themselves, giving clear directions and promoting independent learning. She has to make learning interesting and provide the ‘best’ way of learning and the most effective 26 study methods. On the other hand, a teacher is expected to strike a balance and not be too prescriptive. Students shouldn’t be told what to do but instead be provided with the means to complete a task. A teacher is also responsible in promoting thinking skills and has to provide accurate feedback regarding students’ progress. Conclusion To sum up, the following conclusions about PRC students who participated in this study can be made. First, they have a positive attitude towards collaborative learning and are also motivated to work towards a collective goal in a friendly and harmonious manner. However, the benefits of collaborative learning may not be fully realised if the maintenance of group harmony becomes a stumbling block in that it makes the students apprehensive in voicing their honest views. Second, the students are both confident and receptive to giving and receiving peer feedback. Most believe that this is useful to them in their learning. Third, with regard to the role of the teacher, the students are unsure whether the teacher should be the authoritative figure in class, though most of them will obey their teacher’s instructions. They also expect her to be responsible in assessing their progress. Based on these conclusions, the following recommendations are made. 1. The rationale for making students work in groups could be emphasized at the beginning so as to allow the students to envisage the numerous benefits that can be reaped from working collaboratively; 27 2. It may be necessary to ‘prepare’ the students before actually making them engage in group work. One way is to get them to voice their apprehensions and to anticipate problems that may result from group discussions. The students can then think of possible solutions or ways to circumvent these problems; 3. The students must also be made aware that it is completely acceptable to put forth an opposing view when working in groups, as long as this is done with tact. The difference between being aggressive and assertive could also be highlighted; 4. Before engaging in peer review, the students should be provided with a checklist. This not only allows them to be aware of the areas that they are to review but also to remain focussed; 5. Teachers are no longer only viewed as the source of learning but a facilitator and friend, providing the means to enhance student learning. Other than ensuring that we help our students achieve academic excellence, a genuine interest in their well-being and progress is also necessary. Further Research Despite the often mentioned benefits associated with collaborative learning and peer review in L1 setting, it is beyond the scope of this study to investigate whether students studying a second language could reap similar benefits. This is an area which requires further investigation. Another area is the issue of using a mix of L1 and L2 in group discussions and peer review. Will this hinder or help students in their learning of L2? Answers to this question could provide valuable insights to teachers in our quest to facilitate our students’ learning of a foreign language. In addition, it is not known if 28 factors such as the setting and country in which the instruction takes place, the subject matter learnt and the students’ perception of the instructors teaching the course, do affect students’ responses, and if so, to what extent. This is another area that warrants further investigation. (5525 words) 29 Appendix A – Questionnaire 1 Dear Student I am interested to find out about your views in learning English. In particular, I would like to know your views on group work, peer feedback and the role of the teacher. This feedback is important as it will enable your teachers to plan lessons to better suit your needs. There are no right or wrong answers to these questions. Your answer depends on your point of view and I am interested in what you think. The questionnaire consists of two parts. Please read the instructions at the beginning of each part and concentrate on answering each question as truthfully as you can. You do not need to write your name on the questionnaire when completing it. Your views will be kept confidential and your identity anonymous. You are welcome to discuss any of these issues after you have completed it. If you agree to participate in this survey, please write your full name, date and sign below. Thank you. Christian Chia Tel: 790 3477 Name: _____________________________________ Date: ___________ Signature: __________________________________ 30 PART A Instructions: Cancel the incorrect option. Q1. What is your gender? Male/ Female PART B Instructions: After each statement, please tick only one option that best describes you. The options are: SA=Strongly Agree; A=Agree; N=Neutral; D=Disagree; SD= Strongly Disagree SA A 1. I like activities where there is a lot of discussion with my classmates in a small group (of between 3 and 5 students). 2. I like being part of a small group (of between 3 and 5 students) working towards some common goal(s). 3. It is more important for me to score a good grade than to form a good relationship with my classmates. 4. I prefer to work alone. 5. I don’t like working in a group because I usually end up doing most of the work. 6. I don’t like working in a group because my friends do not put in as much effort as I do. 7. I like to help maintain a friendly and good working relationship when working in groups. 8. Working in groups helps me think of better ideas. 9. Working in groups helps me score a better grade. N D SD 10. Working in groups slows me down. 11. Working in groups helps me learn better. 12. I am willing to work hard even though my own success benefits other students as well as me. 13. I will put in extra effort in a group project if all the group members were not awarded the same grade. 31 SA A N D SD 14. I expect the teacher (rather than myself) to be responsible for assessing how much I have learnt. 15. In class, I usually obey my teacher’s instructions. 16. I believe that the teacher is responsible for imparting knowledge to me rather than having to discover it myself. 17. I prefer to get feedback (comments) on my work from my teacher than from my group members. 18. I enjoy working in groups because it is fun. 19. I enjoy working in groups because I feel more relaxed. 20. I feel more comfortable in voicing my views in group discussions than in front of the entire class. 21. In class, I see the teacher as someone in charge. 22. I don’t mind getting the same grade as the other members when we work as a group. 23. Each group member could be given a different grade even though we work as a group. 24. I feel comfortable to disagree with my classmates during group discussions. 25. I feel confident giving my group members feedback (comments) on their work. 26. I am confident that my group members are capable of providing me with feedback on my work. 27. I will only give negative feedback (comments) to my group members whom I know well. 28. I will not want to contribute any valuable knowledge/ideas during a class discussion for fear that my classmates will score a better grade than I. 29. I believe that my teacher’s feedback (comments) on my language learning is most helpful. 30. The feedback provided by my group members on my work is helpful. 32 Please write any additional comments on peer feedback and group work here: _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Please write any additional comments on the teacher’s role here: _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Thank you for your participation 33 References Bergman, V. 1984. English as a foreign language in the People’s Republic of China: Student and teacher perspectives, expectations and perceptions. Unpublished Ph.D thesis. Claremont Graduate School. Chia, C. S. C. 2001. How receptive are Asian students towards inductive grammar learning? Paper presented at the 36th RELC International Seminar - Grammar in the language classroom: Changing approaches and practices, 23 – 25 April 2001, Singapore. Cortazzi, M. and Jin, L. 1996. Changes in learning English vocabulary in China. In Coleman and Cameron (eds). Change and Language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Cotterall, S. 1995. Readiness for autonomy: Investigating learner beliefs. System 23, 2: 195-205. Forestier, K. 1998. Asian crisis spurs lesson in learning. South China Morning Post. 11 August. Goh, C. C. M. 1998. Strategic processing and metacognition in Second Language Listening: Examining comprehension strategies and tactics, metacognitive knowledge and listening ability. Unpublished Ph.D thesis. Lancaster University. Haughton, G. and Dickinson, L. 1988. Collaborative assessment by masters’ candidates in a tutor based system. Language Testing 5: 233-246. Ho, J. and Crookall, D. 1995. Breaking with Chinese cultural traditions: Learning autonomy in English language teaching. System 23, 2: 235-243. Huang, L. 1991. A discussion of fast reading teaching. Teaching English in China 23: 122-124. Jacobs, G. M. 1998. Cooperative learning or just grouping students: The difference makes a difference. In Renandya and Jacobs (eds). Learners and language learning. RELC Anthology Series 39, 172 – 193. Jacobs, G., Curtis, A., Braine, G. and Huang, S. 1998. Feedback on student writing: Taking the middle path. Journal of Second Language Writing, 7, 3:307- 317. Johnson, K. 1995. Understanding communication in second language classrooms. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 34 Jin, L. and Cortazzi, M. 1998. The culture the learner brings: a bridge or a barrier? In Byram and Fleming (eds). Language Learning in intercultural perspective: Approaches through drama and ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kohn, J. 1992. Literacy strategies for Chinese university learners. In F. Dubin & N. Kuhlman (eds.) Kumaravadivelu, B. 1991. Language-learning tasks: teacher intention and learner interpretation. ELT Journal 45: 98 –107. Littlewood, W. 2000. Do Asian students really want to listen and obey? ELT Journal 54, 1: 31-36. Long, M.H. and Porter, P.A. 1985. Group work, interlanguage talk, and second language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly 19, 207-228. Louie, K. 1984. Salvaging Confucian education (1949 – 1983). Comparative Education 20, 1: 27-38. Liu, D. 1998. Ethnocentrism in TESOL: Teacher education and the neglected needs of international TESOL students. ELT Journal 52, 1: 3-10. Nunan, D. 1992. Collaborative language learning and teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pica, T., Young, R. and Doughty, C. 1987. The impact of interaction on comprehension. TESOL Quarterly 21: 737-758. Roskams, T. 1999. Chinese EFL students’ attitudes to peer feedback and peer assessment in an extended pairwork setting. RELC Journal 30, 1: 79-123. Sharan, S. 1980. Cooperative learning in the small groups: Recent methods and effects on achievement, attitudes and ethnic relations. Review of Education Research 50: 241- 271. Slavin, R. E. 1990. Cooperative learning: theory, research and practice. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. Sullivan, P. 1996. Sociocultural influences on classroom interaction styles. TESOL Journal 6, 1: 32-34. Swain, M. and Lapkins, S. 1989. Canadian immersion and adult second language teaching: What is the connection? Modern Language Journal 73: 150-159. Wong-Fillmore, L. 1991. Second language learning in children: A model of language learning in social context. In E. Bailystok (ed.), Language Processing in Bilingual Children: 49-69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 35 Zhang, S. 1995. Re-examining the affective advantage of peer feedback in the ESL writing class. Journal of Second Language Writing 4, 3: 209-222. 36