Sales and Distribution Management Decisions, Strategies, and Cases by Richard R. Still, Edward W. Cundliff, Normal A. P Govoni, Sandeep Puri compressed

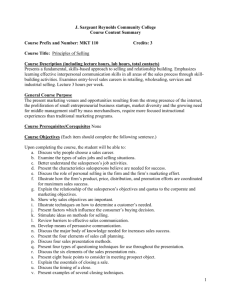

advertisement