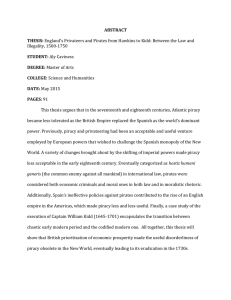

LRP Long Range Planning 37 (2004) 459–475 long range planning www.lrpjournal.com Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? Deli Yang, Mahmut Sonmez and Derek Bosworth This article illustrates the causes of piracy and pinpoints piracy associated with registrations and with production and distribution. Based on interviews with British and American multinational managers working in China, the authors elaborate 10 corporate actions to counter the spread of the ‘inevitable curse’. In order to implement these 10 strategies, the authors recommend that firms treat piracy as a challenge, be corporately proactive, be aware of the repertoire of possible strategies, investigate co-operative action with other companies, agencies and government and be continuously alert to the dynamic nature of piracy. The problems reflected here are common to multinationals operating businesses around the world, and the destructive nature of piracy is likely to encourage more academic study to yield further insights for practice. Q 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction With the rapid expansion of international business, piracy—‘the crime of the 21st-century’ is flourishing and becoming globalised.1 Piracy here refers to ‘the unauthorized use or reproduction of another’s work’, such as a registered trademark. It has much broader meaning than counterfeiting, which means ‘to imitate exactly something valuable or important’, such as counterfeited money, with intent to defraud or deceive.2 The bogus products vary from apparel, toys and DVDs in Asia, pharmaceuticals in the Latino world and luxury goods in Europe to technological bootleg, such as auto and aircraft parts in North America. Piracy is noticeably pernicious in the under-developed and developing world of intellectual property (IP) systems. Multinationals therefore tend to pay particular attention to the protection of IP (including patents and trademarks), when doing business in these countries, because the legal protection 0024-6301/$ - see front matter # 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2004.07.009 of their original inventions and long established trademarks secure them competitive advantages over their rivals. Piracy undermines multinationals’ cross-border businesses. It is commonly alleged that the People’s Republic of China (China) is one of the countries in which much piracy occurs. In 2001, for example, the Chinese government destroyed 11,000 piracy factories, and confiscated US$2.8 million worth of shoddy products, but the figure of actual piracy is far more appalling, including $160 million worth of DVDs, and $47 million worth of CDs and cassettes,3 and counterfeiting has undermined China’s position in terms of attracting businesses from foreign countries. Staunch supporters of IP have dubbed China as the ‘Centre of Counterfeiting’ and ‘the International Capital of Piracy’ for a number of reasons.4 Firstly, the country is presently a centre for global business: multinationals have established themselves in variety of different sectors, and their concerns about piracy attract media and organisational attention. The US trade representatives (USTR), for example, repeatedly files corporate complaints on countries with inadequate IP protection to the US government, and China appeared on their ‘USTR Priority Watch Lists’ in both 1992 and 1995.5 Secondly, the booming of international business in the most populous country on earth also attracts high levels of imitation. Such a lucrative market invites speculators to explore the unsatisfied markets created by low consumer incomes and limited knowledge about the crime. Thirdly, the gap between developed countries and China in IP development attracts great discussion and research attention. This article aims to provide strategic solutions to the problems associated with piracy that British and American multinationals have encountered in China. With this aim in mind, the article will first reveal the major piracy problems, and then briefly explain the data source that has contributed to the research results. The main part of the article then presents an analysis of the strategic solutions to these problems. Finally, the broad implications from the study will be applied to the strategic management context for managers and academics. [The] lucrative market [of the world’s most populous country] invites speculators to explore unsatisfied markets created by low consumer incomes. Piracy: the inevitable curse—problems, causes and effects Piracy problems Pirated production and distribution Three types of production- and distribution-related piracy have been prevalent alongside the booming of global production in China: counterfeiting, licensing overrun, and forgery. Counterfeiting in the form of imitation of designs, fabric, badges, and colours has been common. For example, according to the trademark manager of Manchester United (MU) plc., at least six Chinese cottage factories have been involved in such production with most of the output sold in China and Southeast Asia. Licensing overrun exists where licensed producers exceed stipulated production levels, allowing firms to sell the ‘overrun’ products unofficially in China at a lower price, and even export them to other countries in Southeast Asia. Such goods are, in effect, identical to the real products (except for guarantees and the retail outlet involved): the principal victim is the licensor. Finally, forgery of well-known marks: uses appear to be at first sight the original trademarks, but in a new design, colour, material and/or other details.6 460 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? Piracy associated with registrations British and American multinationals operating in China have encountered piracy associated with the registration of trademarks. Local firms intent on piracy are well aware of both the long established multinational-owned trademarks and the difficulties local agencies have in protecting them due to the size of the country. They can often stay one step ahead of the multinationals, and have well-known trademarks registered to them before the multinationals can establish their rights. For example, a leading pharmaceutical firm applied for patent protection. While the patent application was still pending, two local pharmaceutical factories started manufacturing the compound. Such unscrupulous acts can only be eliminated if the true owner of the trademark can establish, protect and benefit from his rights in both legal and public-reputation terms. Curiously, the international regulations (mainly the trade related aspects of intellectual property (TRIPS) agreement and the Paris convention) do not specifically stipulate the rules on the verification of well-known trademarks.7 Consequently, it is not surprising that this problem is also seen in China, where such a non-integrated standard has resulted in significant levels of abuse, with local firms adding phrases such as ‘famous trademark’ or ‘well-known trademark’ to their own trademarks, such ‘self awards’ leading to widespread confusion for consumers. The situation can be exacerbated when the relevant authority treats such marks inconsistently. For example, MU plc. has been doing business with China since 1993 in the form of licensing. The company, triumphant on the football pitch and also very successful off the field in business, has registered its corporate trademark in different product categories, but five of the seven applications have been approved either with only ‘United’ or without the name (see Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2), although two applications applied for at almost the same time were approved in the full original form. Applications for trademark registrations in different product categories are often directed to different departments in the trademark office. As a result, one department may approve the original mark while another may not. Such inconsistency often results from a lack of knowledge about the application of trademark law—especially a failure to research the standing of the mark in the global context—as well as poor communication between the departments. Such problems seem to be aggravated by the relatively new legal framework in China, and the complexities of and inconsistencies between different departments and government organisations. Where there is a brand there is a fake A number of factors have contributed to the prevalence of piracy in most developing countries, including China. First, the popularity of branded products has created a market demand that is Table 1. Registrations of the MU Trademarks in China 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Original Mark Registration results Manchester United Football Club Same as application No wording Class 18 28 25 33 9 Words ‘Manchester Football 24 Club’ omitted 21 only ‘United’ left Goods Registration Number Date Sports and travelling bags Sporting articles except clothing lothing and footwear Alcoholic drinks Photographic film and transparencies Curtains, towels, banners, flags, and valances Sponges (not for surgical use) 791335 1240536 787396 1243372 1261395 1263245 14/01/95 21/01/99 28/10/95 28/01/99 07/04/99 14/04/99 1265610 21/04/99 Source: compiled by Yang based on the interview and MU’s trademark registrations in China. Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 461 Figure 1. The original mark. Source: obtained from and permitted by the MU Trademark Office. only partially satisfied, especially when the set price is out of reach to the majority of potential buyers. Second, the value of the brand (derived from long-term advertising, brand maintenance and product design costs) increases the price gap between original and pirated products, providing a financial incentive for pirates to satisfy the latent demand. Thus, pirates are able to undercut the price, attracting some customers that cannot afford the official merchandise. Third, the geographical size of China limits the ability of both government and manufacturers to exercise effective control of piracy, and control of piracy in one area will not prevent infringements breaking out elsewhere. Fourth, the piracy problem can be exacerbated when operational contracts between Sino-foreign partners are not sufficiently specific about the issue of infringement to stop or even curtail it. In such circumstances, given the limitations of resources and vast geographical size, Chinese government enforcement of trademark law has to rely largely on the aggrieved party providing evidence. The penalties are still relatively lenient and administrative in nature, such as warnings, public apologies, fines and compensation, although Figure 2. One of the marks registered in China. Source: obtained from the MU Trademark Office, Manchester United plc. 462 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? the fines have progressively been increased.8 What is lacking are criminal convictions—as pirates tend not to keep records of their sales, it is difficult for the relevant authority to impose criminal liability. If the Chinese government remains unwilling to be proactive in ending piracy, and companies neglect taking sufficiently robust actions, it seems inevitable that infringement will continue. Finally, the public awareness of the deleterious effects on consumers of such pirated products as fake spirits and shoddy drugs takes time to evolve. Although in recent years, education on the significance of IP has been widely campaigned in China and most developing countries, many consumers are still not clear why piracy is a victim game. Piracy—a victim game Piracy is not a victimless game as so many people think, but an unscrupulous practice requiring continuous surveillance and resolution. Host countries, multinationals, and consumers are all victims of piracy. The host nation will have to bear the cost of allocating resources to handle the piracy issue, enforce legal powers to curb piracy, and bear the cost of lost tax revenue and unemployment (although piracy can create illegal employment, albeit with limited tax payments for government and uncertainty for the workers involved). For example, the reduction of every 10 percentage points in the piracy rate is estimated to have generated 13,170 direct and indirect jobs for the software industry in China, and US$78 million in Chinese government revenues in 1998.9 In terms of production and services, global piracy amounts to approximately 5–8 per cent of total world output.10 For consumers, the pirated products provide no warranty, after-sale services or sense of security, and fake products often mislead or confuse consumers with their low quality and low prices. Multinationals with IP ownership are the most direct victims and bear the weight of piracy speculation both to their finances and reputations. The damage is clearly reflected in swift decline of sales, affecting corporate employment, market share, undermining long-term R&D incentives and the intangible loss of the brand devaluation. Corporate competitiveness is also affected, with firms sometimes having to bear legal liability for bogus products following consumer complaints, as well as the costs of educating consumers and countering piracy. For example, MU plc. indicates that it is very difficult to precisely estimate the losses in figures in individual countries, but the ‘guesstimate’ is that it loses £3 million annually in Asia due to piracy. (This figure does not include the costs of anti-piracy action by MU, which is confidential information.) Procter and Gamble also spends $3 million annually dealing with piracy.11 Given that piracy poses such an array of threats to host country, consumers and multinationals alike, it is apparent that firms cannot treat piracy as a curse only; corporate actions need to be taken to challenge this blight and seek effective remedies. MU plc. ‘guesstimates’ it loses £3 million annually in Asia due to piracy. Methodological note Table 2 provides a brief summary of the methodology underlying this article: details of sample selection, collection procedure and analysis are given in the Appendix. The corporate strategies recommended in this article are based on the valid responses from 51 British and American companies with manufacturing activities in China in 2002–3. Questionnaire responses were received via email and clarified if necessary by telephone. The authors selected the manufacturing firms because they accounted for 86 per cent of the foreign operations (by value) amongst the top 10 industrial sectors in China.12 Moreover, piracy is more prevalent in this sector than in any others in China.13 The interviewees were executives in charge of IP or technology and development (86 per cent of respondents), or corporate lawyers, chief executives or their assistants. All the managers wished to preserve their anonymity, and although a Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 463 Table 2. Summary of interviewee profile Number of initial contacts 183 Number of valid responses Company types Nationality distribution of respondents Value range of foreign IP Revelation of respondent identity Revelation of corporate identity Positions of the respondents 51 US, UK firms with IP activities in China 21 British; 30 American £0.1–£3000 million No 2 Yes; 49 no 21 IP or technology managers 14 Development manager 9 Regional managing directors 7 Lawyers, CEO or CEO assistants Chemical; pharmaceutical; software; memorabilia, machinery and equipment; computer Various from 1984 to 1998 Manufacturing Year of establishments Source: based on the interview data. few consented to their corporate identity being revealed, in the most part this study (which represents their interests) maintains the anonymity of both individuals and their companies. The interviews were based on a semi-structured questionnaire with a problem–cause–solution framework exploring the extent of piracy, the causes and corporate solutions. This article focuses on the solutions adopted by different companies to tackle the prevalence of piracy. Each of the 10 strategies outlined below is illustrated with examples, and the costs and benefits of adopting the strategies are discussed. Strategies to challenge piracy It can be concluded from this research that effective multinationals are those willing to counter the arduous corporate challenge of piracy with strategic responses. The authors broadly taxonomise the strategic responses from the firms into three broad categories: proactive approaches, defensive weapons, and networking means under which 10 specific strategies can interact to form the integral and effective actions for multinationals to counter current and future piracy (see Figure 3). Strategy 1: the Budweiser strategy—technical solutions The most commonly adopted anti-piracy strategy is effective labelling and featured packaging allowing consumers, distributors, retailers and owners to identify authentic products easily. Budweiser has been very successful in using this strategy (which has thus been named after the firm). It has produced a special type of beer can with fluted edges, which makes imitation very difficult.14 The majority of the interviewed companies have introduced individually numbered security labels, anti-tamper foil labels, tanglio printing (commonly used for preventing fake currency) and holograms (a three-dimensional logotype transposed into labels) for their products. The digitalised labels help companies to trace the production date and manufacturer, identify the fakes from the genuine (no single number appears twice for a product), and prevent counterfeits from entering the official channels. Companies tend to combine a number of labelling techniques for their products. Some of the authentication techniques are deliberately made easily visible for consumers to verify, while others are not as they are intended for inspection by firms and other authoritative organs. For example, MU plc. uses an ample light test—ultra-violet sensitive signs that counterfeiters cannot afford to replicate—to verify if the 464 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? Figure 3. Taxonomy to form corporate strategies. Source: created by the authors. products entering their official stores are authentic. Such devices are not available to consumers, and the authentic labelling cannot be seen with the naked eye. This strategy has its merits and drawbacks. It is an effective strategy in restricting pirated goods from entering the official channels and preventing licensees from overrunning production of the authentic products by supplying only limited amounts of authentic labels. Firms, distributors, retailers, and consumers can now more easily identify the authentication of a product. This strategy is more preventative than curtailing, which is particularly effective in piracy-prevalent countries like China, Thailand, and Turkey. But while such strategies will be effective against less-proficient pirates, they will fail against more sophisticated counterfeiters with the expertise to replicate authentic marks unless firms can constantly anticipate them by raising or replacing technical barriers, with the obvious implications for financial and manpower resources. Visible labelling provides information to pirates which can, given time, be copied to continue to confuse consumers. But less identifiable labels and technical solutions may also create problems, as consumers cannot tell the fakes from the genuine, leaving pirates the opportunity to provide the market with confusing replicas. Furthermore, such hidden solutions may need special reading devices or other aids, resulting in additional costs for the retailers. Strategy 2: the partnership strategy—contractual surveillance Reaching a well-specified contract between Chinese firms and their foreign partners at the outset is the key to reducing the likelihood of IP violations, and can also assist in resolving disputes and avoid partners having to resort to the legal process, which many managers considered unviable in terms of cost and time. A tight contract should also have specific stipulations on the punishment for any party violating the contract. There should be leeway for flexibility to modify the contract based on the circumstances to allow ‘the benefit accruing to the [relevant] party’, as one manager explained. This strategy addresses the differing cultural views on contracts between Western and Chinese business people. While western managers perceive contracts as legal binding, Chinese managers deem that partners should rely on trust and respect to do business, with a contract as a general guideline only. The fact that most Sinoforeign partnerships were established between Chinese firms under state and/or collective ownership and privately owned foreign firms has further aggravated the contractual situation. Thus conformity to a contractual agreement has become important tool in preventing commercial misdemeanours, forcing relevant parties to abide by the contractual conditions and particularly effective in preventing overruns in licensed production. However, given the difference in understanding contractual functions between the Chinese and Western mentality, negotiating a Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 465 quality contract is often a lengthy process. As a manager said: ‘It is better to go through the pain early [contractual negotiation] than later [piracy overrun and other potential problems].’ Chinese managers deem partnership should rely on trust and respect, with a contract as a general guideline only. Strategy 3: the Coca Cola strategy—narrowing price gaps This strategy is to lower product price in order to narrow price-gap between the authentic and fake products. Coca Cola China is a good example of successfully adopting this strategy. The firm has adopted a low pricing strategy for its Cola drinks in China, allowing little room for pirates to make illegal income. (Microsoft China has also used this strategy to promote its products by lowering prices many times.) Key to pirates’ lucrative business is targeting a particular niche market by exploiting the authentic owners’ high R&D, advertising and services costs. The availability of cheap replicas certainly attracts a large number of ‘conscious’ consumers, i.e. those who are knowingly buying fake products. Attractive products, such as a Prada handbag, may be technically uncomplicated for pirates to replicate, and confer immensely high prestige to buyers. Customers may feel their only risk is whether such ‘symbolic’ products, highly visible in society, will appear genuine or be recognized as shoddy imitations.15 The reduction of pricing gaps between the fake and the genuine can certainly gain firms many consumers, including some conscious consumers. The main attraction for consumers buying a fake product is the price. Their expectation is low, as they understand the risk that the fake may not function properly. If the authentic firms promote their products at a competitive price—even if it is higher than the fake—the excellent quality and brand image, together with the availability of an attractive after-sale warranty, will attract consumers to buy the genuine article rather than the fake. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of this strategy is limited by a number of variables depending on the company concerned. Firstly, this strategy may have little influence on most conscious consumers, who believe that cheap is beautiful and authentic firms are exploiting them. Therefore, this strategy should be combined with other corporate tactics, such as education campaigns, in order to have the best effects on a wider range of consumers. Secondly, this strategy may not work well in high R&D firms. Taking Coca Cola and Microsoft China as examples, the difference between the Coca Cola drink and Microsoft software is the high input of Microsoft R&D in software, which needs to be recouped through sales. In comparison, the Cola drinks are based on the inherited ‘secret ingredients’ (held by only four top executives in the company) and the long established brand, and its R&D costs are likely to be minimal.16 Even if Microsoft lowered its price to the minimum, pirates can still make profits by free riding the costly R&D and advertising expenses. Such a strategy could be employed, for example, by MU plc. The current cost of a Manchester United home jersey is £35,17and while this may be seen as expensive for ordinary British consumers, it is certainly beyond even the imagination of most Chinese consumers. Given the low cost of production (materials, labour) and its millions of fans, MU may be well advised to adopt a localised pricing strategy to curtail piracy and to attract consumers. Strategy 4: the Microsoft strategy—monitoring and private eye Monitoring markets and relevant products is also a widely adopted strategy, and Microsoft China is a pioneer in upgrading their strategy effectively as circumstances change. This strategy has a broad meaning. First, it can involve liaison with customs, to prevent fake products from entering the home country, utilising cooperation between importers, exporters, licensers and customs officers to maintain checks and controls on pirated products. Second, it can also mean 466 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? that company employees survey the market to ensure that any fakes are detected and sales prevented. Third, monitoring by regular inspection of relevant manufacturing bases can help to prevent production from overrunning. Finally, on-line piracy has in recent years added a new wrinkle to an already aggravated situation. For example, large amounts of fake products are auctioned alongside authentic products on major auction sites, such as e-Bay, Adobe, Yahoo, etc. Consumers posting files to share with the public, especially for music, and software products, further exacerbate the piracy situation. As an example of implementing a monitoring strategy in this area, Microsoft has now adopted on-line monitoring on a round-the-clock basis. When fakes are detected, the posters are warned, the buyers of the fakes informed, and offenders notified to withdraw their on-line piracy activities within 24 hours or risk further actions being taken by the company. As part of the monitoring process, private investigators are often hired to collect evidence and undertake undercover investigations on behalf of a company. Unlike the USA (which has 39,000 private investigators), this is a relatively new profession in China, where it is often undertaken often as an affiliated responsibility by IP agents, or by small-scale firms or retired police officers.18 However, their presence has accelerated the investigation of pirated products by focusing on suspected cases. Microsoft has adopted on-line monitoring on a round-the-clock basis. In-the-field and virtual monitoring strategies protect the interests of legitimate firms and consumers who wish to buy authentic products, but it is an expensive strategy, especially when a wide spread of monitoring is carried out. Large multinationals like Microsoft may have the financial capacity to deal with the geographical spread of piracy. But most mini-multinationals (small- and medium-sized companies), while they may monitor their home country intensively to preventing fake products entering retail channels from production countries, can only afford to handle such situations in foreign countries on a case-by-case basis. The costs of monitoring in a vast country such as China are much more substantial than in smaller countries like Thailand. The Internet auction of fake products and posting for on-line sharing are both borderless crimes, and offenders can make detection more difficult by operating from fake addresses. Strategy 5: the commercial settlement strategy The corporate managers interviewed for this survey confirmed that financial settlements with pirates can also be a quick cure for counterfeiting. This strategy is based on the Chinese cultural background and the managers’ low level of confidence about legal enforcement. One IP manager indicated that the pirates’ cultural background means a demand for a public apology may well lead to them choosing to offer financial compensation and cessation of activities, rather than risk the loss of public face involved in an apology. Instigating a lawsuit is a lengthy procedure to go through, and the result can often be unpredictable. A private financial settlement with an offender can give an aggrieved party a much more efficient and effective way to resolve cases of piracy, with a possibility of recouping some of the losses incurred. Such a settlement requires firms to take a proactive role to approach their ‘enemies’ directly, or through the assistance of a third party. Even though such settlements may fail in the end if offenders refuse to pay, direct negotiations between the aggrieved party and pirates can provide a mechanism for firms to construct a case by gaining evidence during the negotiations which they can use later when seeking support from the authorities. Strategy 6: the acquiring strategy The managers interviewed for this research also identified acquisition as an effective and overall non-cost solution when a pirate is detected. Specifically, when a pirated product is detected Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 467 in the market, the firm will trace the source of production. During the investigation process, the firm can evaluate whether the pirates have the necessary quality to become part of the authentic firm. When all the primary evidence is available, the aggrieved party can approach the piracy factory. The reaction from the pirated factories is usually mixed. On the one hand, they are often shocked at what one respondent manager called the ‘discovery and courage of the original firm’. On the other hand, managers report that firms are generally both overwhelmed by and also pleased with such offers, not because of the chance of financial benefits, but with the prestige of being part of a brand firm and the pleasure of doing legitimate business that flows from such a situation. The benefits of such an action are substantial. It allows an aggrieved party to prevent the production of pirated products, acquire the pirate firm to be part of the authentic firm and use its quality standards to provide authentic, but cheaper, products to the market, perhaps deterring similar products from other pirates. This action also allows firms to prepare relevant evidence in the negotiating process. If the piracy firm does not agree on the acquisition, (which is unlikely, given that the pirate firm has been given no alternative) the authentic firm will have already acquired enough evidence to report the pirate to the relevant administrative organisations for a raid, which would eliminate the pirate operation immediately. Thus, acquiring is a win-win strategy—whatever the result, the firm can benefit from the action. However, a number of conditions must exist for such an acquisition to happen. The pirate firms must have skilled workers, a strong marketing network, and good sourcing markets for supplies. And the authentic firms must have the intention and financial resources to handle the initial costs of such a ‘special’ expansion. Pirates are shocked at the ‘discovery and courage of the original firm’. Strategy 7: the DuPont strategy—reapplication This strategy is called the DuPont strategy following its first adopter, E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Co.19 In 1983, the Trademark Office in China refused DuPont’s application to register its trademark ‘Freon’ because consumers and manufacturers in China had already widely adopted the phonemic translation of this foreign word for refrigerants. The trademark was also not registered because the Trademark Office was not familiar with all the well-known trademarks in the world. A mark may be well known in one country, but generic in another.20 In the reapplication, the firm adopted a very persuasive tactic with convincing evidence to demonstrate that DuPont was the originator of ‘Freon’, and had been using the mark since 1931. The mark had been registered in 91 countries, and Freon had even been listed in the Collin’s Dictionary as a well-known trademark. As a result, the Chinese government not only approved the trademark after review, but also urgently notified the firms concerned and the general public in China to stop using Freon as a generic name, and adopt the substitute ‘Fluorine refrigerant’ for relevant products. As discussed earlier, MU plc. is a successful example of a firm adopting the DuPont Strategy. The company has applied the strategy to reapply the Class 25 products (see Table 1) with a demonstration of the validity of the case. Specifically, the company substantiated the inconsistency of the trademark registrations by comparing the original mark and marks registered in error. The firm has also proved that the words ‘Manchester United Football Club’ and the logo are inseparable, and as a mark, had over 100 years of history and been registered in over 40 countries as a symbol of the firm’s business. At the time of writing, MU plc. has successfully had its Class 25 trademark re-registered in China. Other inaccurately registered marks were also reapplied for. In order to correct these marks, MU trademark attorneys made trips to China to persuade and convince the Trademark Office. 468 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? This strategy is effective in dealing with the registrations associated with piracy, including early registrations from unscrupulous firms and incorrect or inaccurate registrations granted by relevant organisations. To a great extent, the effectiveness of this strategy lies in the proof provided by the trademark owner, although the final decision depends on the relevant bodies in China. Moreover, the overall environment in China has been improved to the advantage of well-known trademarks since China’s entry into the WTO. The 2001 amendment to the trademark law may help trademark owners whose marks are well known in other countries but not in China, as applicants are now allowed to apply for corrections of ‘obvious errors’ made by the Trademark Office.21 Under the amended trademark law, firms can seek redress in court when the second application fails, thus leaving final decisions to the court instead of an administrative body: this improvement is in line with the TRIPS agreement. However, the DuPont strategy is a ‘Hobson’s Choice’, as well as being unpredictable, costly and time-consuming for firms. There is no choice but to re-apply to the trademark office (as the highest authority on registration) but the outcome cannot be relied on. This strategy is time-consuming because the procedure to have a mark registered is long-drawn out, and each application means extra costs for firms. For example, the reapplication for the Class 25 mark cost MU plc. £6,000 (including fees) to persuade and convince the government, adding up to almost £30,000 if the five marks were to be re-registered. Furthermore, the costs and risks could be substantially increased if the company went to court after a second attempt failed. This would include fees for a lawyer, the risk of failure in court at the first instance and on appeal, and the possible price to pay for withdrawing the business from China and transferring to another country if both failed. However, given the reality of the lucrative market, the low cost production and skilful labour, companies would rather take the risk and bear the costs to fight their chance for success. The DuPont strategy is a ‘Hobson’s Choice’, as well as being unpredictable, costly and time-consuming. Strategy 8: the MU strategy—communicating with aggrieved firms This strategy is to establish communications with a network of other ‘brand name’ firms operating in China and take collective measures to exert pressure jointly both on pirates and on relevant organisations to take administrative actions. MU plc.’s actions have been a model for such a strategy: the firm has established communications with a network of ‘brand name’ companies, such as Puma and Levis, who meet regularly to discuss their experiences of countering piracy, including the problems they have encountered and appropriate measures to solve them. Such alliances allow the companies to learn from one another, in particular in sharing successful experiences and planning joint actions. Collective actions also strengthen firms’ persuasive powers with governments, save costs with collective sharing and reinforce anti-piracy measures. External pressures on governments in liaison with non-government organisations, such as the International Anti-Counterfeiting Coalition, can often be forceful and effective. In forthcoming meetings with the companies, for example, MU plc. will alert members to the severe impact of Internet piracy, and discuss what collective actions could be taken to curb the rapid spread of this new form of piracy. The advantage of this strategy is that cost sharing certainly alleviates the financial burden for firms, and it works not only for multinationals, but also for mini-multinationals with limited financial budgets. The only burden is to coordinate such communications, and to increase corporate persuasiveness on governments to accelerate the policy-making process. Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 469 Strategy 9: the government hand strategy All the survey firms emphasised the vital importance of cooperating with and seeking support from government, as well as maintaining close cooperation with government administration and enforcement agencies. Relevant government authorities can be very co-operative in tackling piracy, such as organising a raid or an injunction, etc. However, government decisions and action rely on aggrieved companies providing hard evidence. Microsoft China is a very good example of cooperation with government. It has put IP protection as its top objective in China. To assist government in fighting IP violations, Microsoft has trained government officials and established training institutes to increase knowledge awareness of IP in China, and this will tend to exert long-term external pressure on government to tighten legal enforcement on piracy.22 Such government actions not only emphasise the gravity of piracy to the public, but also function as free advertising for the aggrieved party in the brand promotion. While this strategy can be bureaucratic, managers still think that it is a better route than immediately instigating legal proceedings. To be productive, the strategy relies on firms jointly providing detailed evidence to the relevant organisations as part of persuading the government of the essential importance of action. While the decision to act rests with governments, firms should proactively seek support from them by taking action to cooperate with governments. Although the government may be inhibited from investigating individual cases due to the limitations of time, human resources and the vast geographical spread, managers felt that, once evidence is provided, it was willing to pursue and prove the truthfulness of the matter, and to take further action. Strategy 10: consumer campaigns Increasing consumer awareness and improving consumer relations is a long-term brand building strategy in various ways. The most direct means is to incorporate advertising including piracy education into peak time TV programmes, including text and images designed to alert consumers about piracy, and emphasise authentication certificates and ways for consumers to verify the genuineness of products. Another very direct method is to mount consumer campaigns in shopping centres: firms assign employees to show how to identify the authenticity of their products, and maybe display fake products for comparison. Companies may also cooperate with other firms to sponsor large-scale campaigns with relevant organisations at city, provincial, and national levels. Such campaigns attract media attention and raise consumer awareness, educating the general public about the significance of piracy and the economic damage it causes. Such consumer campaigns can be costly and take time to evolve, but can be very effective if they are organised to take account of consumer interests, cultural understanding and the ability of consumers to understand the information. This effectiveness will certainly be increased if they are organised jointly with governments, relevant companies, non-government anti-piracy organisations and deceived consumers. Such campaigns would also educate many consumers to voluntarily give up buying shoddy fakes, and enhance consumer and corporate relations and brand image. In this process, firms can also explore the needs of consumers for their products, demand conditions being an important success factor to inspire firms to constantly introduce new products to the markets. Again, this is a double victory strategy, as firms educate consumers and explore consumer needs at the same time. Implications This article, based on the response of British and US manufacturing multinationals in China, has highlighted 10 corporate strategies to tackle the prevalent piracy situation, listed in Table 3. The 10 strategies are to use proactive approaches, defensive weapons and networking means to actively prevent and curtail piracy and protect corporate reputation. The proactive approaches include effective labelling and packing, contractual surveillance, appropriate pricing, and 470 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? monitoring to prevent piracy prevalence (strategies 1–4). The defensive weapons allow firms to corporately resolve piracy problems with commercial settlement, and acquisition (strategies 5 and 6). In addition, firms can gain support from different external forces, such as government support, joint actions with other firms and international anti-piracy organisations, and from increased public awareness among consumers (strategies 7–10). Corporate managers and academics should bear in mind the wider implications of this article for implementing of the 10 strategies. Although the study is based on British and American managers’ experiences in the manufacturing sector in China, it has significant implications for corporate managers across all industries, sectors and countries. Firstly, managers should adopt a common attitude and response: piracy is an endless and inevitable problem, and an economic challenge. Taking a united stance will allow firms to avoid indecision or helplessness and force managers to face the reality about the current situation in the Chinese market. The IP system in China has only been established for a little over two decades, and is much less secure than the IP systems of developed countries like the UK and USA—the pioneers in IP advancement. As a manager argued: ‘There is no point in complaining how inadequate the Chinese IP enforcement is, which will not change overnight. Instead, find your own solutions when there is a problem.’ Secondly, firms need to proactively take corporate actions when piracy is detected, treating it as a daunting challenge rather than an affliction. The challenge is to combine a repertoire of the 10 strategies to handle individual cases effectively. In this process, firms not only need to cooperate with relevant government organisations but also liase with firms with similar problems, and more importantly, work to prevent piracy from happening in the first place. Firms also need to work closely with consumers to educate and persuade them to stop buying fakes. They need to be reactive to piracy itself, and take on the task of educating pirates about the importance of respecting intellectual creations. Thirdly, corporate managers must also understand that there is a price to pay in handling piracy. It is a very costly challenge that demands inputs of time, manpower, and corporate budgets. Firms obviously have different financial strengths to face the challenge, but the key is to make the best use of the limited budgets allocated for curbing piracy and prevent their operations from being hurt by illegitimate businesses. As a manager indicated: ‘No matter what action you take, it is still more beneficial than instigating a lawsuit. Why? A lawsuit is unpredictable, time-consuming, and costly, the effects of it can be limited because pirates rarely go to prison, and a penalty can be limited with a fine, which can often be settled quickly between pirating companies and us.’ Furthermore, a legal action is usually concerned with one single case, which does stop one wrongdoing, but does not prevent other wrongdoings from emerging. Therefore, the most effective methods are to admit the reality, be proactive, and commit corporately to handle piracy cases by using a combination of the 10 strategies. Finally, if global business is dynamic, piracy will not be static: when old problems are solved, new problems will arise. Where there is a popular product, there is a piracy, because pirates are always aware of how to exploit the unsatisfied market. In recent years, Internet piracy has become a serious and contingent issue. What action should firms take to resolve this problem effectively? This article has argued that the Microsoft monitoring strategy can curb virtual piracy to some extent, but it also has many limitations. Are there any other effective strategies that firms can adopt? This is an immediate issue for both managers and academics to consider. If global business is dynamic, piracy will not be static. Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 471 472 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? Tight quality contract and supervision Lower price to allow little space for pirates to compete Field and virtual monitoring of manufacturing and distribution 2. Contractual surveillance 3. Coca Cola strategy Source: prepared by the authors based on corporate interviews. 10. Consumer campaign 9. Government hand 8. MU strategy Reapplication of IP with persuasive evidence Networking means 7. DuPont strategy Immediate financial returns, stop piracy, and further action can be taken with a constructed case if this fails Prevent further piracy from certain pirates, cheaper productions with quality control, and prepare relevant evidence for further action if this fails Prevent pirated goods from entering the official channel, and licensing overrun Prevent product overrun, and abide by contractual agreement Attract consumers to give up fakes and buy authentic products Keep fakes checked and take immediate actions with evidence Pros Resolve wrong registrations from the authority, and/or early registrations from other companies Network with other firms to share the grief and Learning curve for all firms, strengthen experience, take joint measures to curb piracy, pervasive power to government by joint efforts and cost-sharing and pressurise authorities to take action Cooperate with and seek support from the Wide publicity and media attention on piracy, government improve relations through working with the government, and brand building in the process Advertising, shopping centre display, Brand building, educate consumers to give up sponsorship on anti-piracy with firms and fakes voluntarily, improve customer relations, organisations and network with firms and organisations Buy piracy firms 6. Acquiring strategy Defensive weapons 5. Commercial settlement Strike a financial compensation with pirates Effective labelling and featured packaging Proactive strategies 1. Budweiser strategy 4. Microsoft strategy Measures Strategies Table 3. Ten corporate strategies handling piracy Costly, time-consuming, and immeasurable about the effects Bureaucratic, and take time to collect evidence and prove the case Needs good organisation and coordination Unpredictable, costly, and time-consuming Conditional that pirates must have skilled workers and other packages, and financial loss initially Negotiation can be lengthy, and pirates may be unwilling to pay the sum Not a very attractive strategy for high tech products Costly, and on-line transactions can be difficult to trace when there is a fake address Financial backup, human power for checking, and research the capacity of replication Lengthy negotiation with partners Cons Acknowledgements The authors would like to express their deeply felt gratitude to the Editor-in-Chief, Professor Charles Baden-Fuller, and the two anonymous referees for their constructive comments and valuable advice. In addition, this piece of work would not have been concluded without the willingness, patience and insightful assistance from the corporate managers that the authors have contacted. Their names, due to confidentiality, cannot be revealed, but the authors are greatly indebted to them for their generosity with their time and efforts. Appendix. Methodology Sample selection The data in this study comes mainly from questionnaire responses and email interviews. The interview sample selection was based on the first author’s 2000 survey of a broader IP topic among multinational managers in different manufacturing industries in China. The samples were chosen from the 1999 lists Top 100 British and American Enterprises, Fortune 500 and Top 500 Multinationals in China (published by the Ministry of Commerce in China). In the end, 183 companies were discovered with IP activities in China in different forms. The first author contacted these companies with a semi-structured questionnaire via email or by post. As a result of this survey, 51 companies provided valid responses and were willing to participate in further interviews which took place in 2002/03. Confidentiality was an important issue with regard to the interviews. The author has not identified individuals and corporate names, the investing capital, establishment of the firms, or number of employees, nor has she offered an individualised summary of the participants: the respondents’ belief that the revelation of such information could easily make them or their firms identifiable has been respected throughout this study. All the respondents working for these firms have been involved in IP activities in China, including patents, copyrights, and trademarks. The interviewees include managing directors, deputy managing directors, IP lawyers, development managers, IP managers, and CEO assistants, and all were highly educated with at least a bachelor’s degree (the majority of them having a Master’s degree, and three of them holding Ph.Ds). The respondents’ industries are all involved in manufacturing in China, including the pharmaceutical, chemical, software, machinery and equipment, computer and memorabilia industries. All interviews were conducted in English in order to avoid cross-language differences. Data gathering procedure All the data collection followed the same procedure. First, a questionnaire was designed following the problem–cause–solution framework established by the first author. The interview questions are either structured or unstructured. Structured questions were all indicated on a 6point Likert scale with 1 meaning strongly disagree, very low, very poor, or very unlikely and 6 indicating strongly agree, very high, excellent, or very likely. (The 6-point scale is used to prevent respondents’ tendency of choosing the middle scale, i.e. choosing 3 on a 5-point Likert scale.) Second, all the interviewees were contacted by telephone to request a questionnaire response and email follow-up interviews with the first author. This was not difficult, as these interviewees have been in contact with the first author over the last few years. Third, the authors sent the questionnaire to the interviewees, requesting their respective confidentiality requirements, e.g. if they would like to have their individual and corporate names revealed. The author received all the first responses within 15 days, and within the following two weeks, emails were further exchanged with the respondents for clarification and for in-depth discussion and further clarification. Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 473 Analysis and validity The authors followed the following five steps to conduct the analysis and ensure validity. . Step one was to organise each response using axial coding. . Step two was to categorise each response into the model framework of problems, causes, and solutions. . Step three was to organise all the individual responses into themes within the framework when all the individual data were categorised. . Step four was to write up the draft based on the organised data. . Step five was to send the draft to the respondent for assurance of validity with two purposes; . The first was to check the accuracy of the facts presented in the analysis and to ask them to point out any matters that they disgreed with. This resulted in a further in-depth study, as old information was confirmed and new information found in the process. . To allow the respondents to check any identifiable factors that could reveal corporate and individual identities, especially sensitive IP information. Where this was the case, respondents tended to provide suggestions to make the factors unidentifiable. References 1. International Anti-Counterfeiting Coalition, Customs Seizures Valued at More than $73 Million in First Half of FY 1999, Available from http://www.iacc.org/customsfy98.html (accessed in July 2003), (1999). 2. The New Oxford Dictionary of English (2001), edited by Pearson, J. Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp. 418, 1411. 3. R. Meredith, The counterfeit economy, Forbes 171(04), 82 (2003). 4. B. Robins, China has now been identified as the Centre of Counterfeiting Activities particularly in the Area of CD, CD-ROM, and Computer Software Pirating, Pacific Economic Review, Fall (1994). See also The Economist, In praise of the real thing, May 17–23, 2003, pp. 12. 5. D. Bosworth and D. Yang, Intellectual property law technology flow and licensing opportunity in the People’s Republic of China, International Business Review 9 453–477 (2000). 6. This has also been called reverse piracy or reverse counterfeiting. 7. D. Gervais, The TRIPS Agreement: Drafting History and Analysis, Sweet & Maxwell, London (1998). 8. The trademark law of the People’s Republic of China, (2001). 9. PricewaterhouseCoopers, Contribution of the Software Industry to the Chinese Economy PricewaterhouseCoopers, Commissioned by the Business Software Alliance, 1998. 10. J. Van Wijk, Dealing with piracy: intellectual asset management in music and software, European Management Journal 20(6), 689–698 (2002). 11. The Economists, Imitating property is theft, May 15, 2003, pp. 69–71. 12. T. Qu and M. B. Green, Chinese Foreign Direct Investment: A Subnational Perspective on Location, Ashgate, Aldershot; (1997); P. Lan, Technology Transfer to China through Foreign Direct Investment, Avebury, Sydney (1996). 13. D. Yang and M. Sonmez, The WTO and trademark development in China, Journal of World Intellectual Property 6(4), 633–653 (2003). 14. www.budweiser.com. 15. A. Nill and C. J. Shultz II, The scourge of global counterfeiting: ethical consumer decision making and a demand side solution, Business Horizons 39(6), 37–42 (1996). 16. Anon, The closely guarded recipes, News, North West, January 30, 2001, pp. 11. 17. www.jjb.co.uk. 18. The data are available on the US Bureau of Labour Statistics at www.bks.giv/oco/ocos157.htm, quoted by Hopkins, Kontnik, and Turnage in Counterfeiting Exposed: Protecting your Brand and Customers, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken. 19. C. Zheng, B. Dong, Y. Cheng, M. Cheng, Y. Sun (Eds.), Intellectual Property Case Analysis, Law Publishing House, Beijing, (1995). 20. Similar examples are the Aspirin and Sherry debates, which, as marks, were lost in some jurisdictions, but were successful in others. 474 Intellectual Property Abuses: How should Multinationals Respond? 21. On the condition that the correction does not ‘relate to the substance of the trademark registration documents or application documents’, Article 36 of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China (2001). 22. www.microsoft.com/China. Biographies Deli Yang is Lecturer in Intellectual Property in International Business at Bradford University School of Management. Her Ph.D. was on Corporate Management of Intellectual Property (IP) from Manchester School of Management, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, UK. Her research interest is in the significance of culture in IP, the impacts of IP on internationalisation, mergers and acquisitions, international negotiations and corporate strategies against international piracy. Bradford University School of Management, Emm Lane, Bradford, BD9 4JL UK. URL: http://www.bradford.ac.uk/management/people. Tel.: +44-1274-234364; fax: +44-1274546866. E-mail: d.yang@bradford.ac.uk. Mahmut Sonmez is Lecturer in Management Science at Loughborough University Business School. His Ph.D. was on Decision Modelling from Manchester School of Management, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, UK. His main research interests include strategic solutions on decision-making problems, and violations of IP rights in developing countries, particularly China and Turkey. E-mail: m.sonmez@lboro.ac.uk. Derek Bosworth was Professor of Economics at the Manchester School of Management, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, UK. His Ph.D. concerned with the Economics of IP. His research interests include economics and management of IP and the determinants of firm performance. E-mail: derek.bosworth@btinternet.com. Long Range Planning, vol 37 2004 475