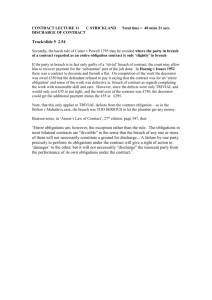

UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, JAMAICA SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION BUSINESS LAW UNIT 2 – LAW OF CONTRACT Definition A contract is a legally binding agreement between two or more parties which is essentially commercial in nature. Not all agreements are considered legally binding. For an agreement to be considered legally binding, the parties must intend legal consequences to follow their actions. Essentials of a binding contract A. Offer An offer may be defined as a clear statement of the terms on which the offeror is prepared to do business with the offeree. An offer may be bilateral (i.e. a promise made in return for a promise) or unilateral (i.e. a promise made in return for the completion of a specified act). For an offer to be valid, it must: 1. Have clearly stated terms (it must be definite) Gunthing v Lynn 2. The offeror must have an intention to do business Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. Ltd. 3. The offer must be communicated Invitation to treat is not an intention to do business – Fisher v Bell, Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists, Patridge v Crittenden, Grainger v. Gough Statements of negotiation are not intentions to do business – Harvey v Facey Offer must be communicated Offer may be communicated verbally, in writing or by conduct – Note – Invitation to submit tenders are generally considered invitation to treat, although it may also be considered an offer by the advertisers to consider any offer submitted to them. (Blackpool v Blackpool Council) 1 Termination of offers By refusal and counter offer – Hyde v Wrench, Stevenson v McLean By lapse of time – Ramsgate Hotel v Montefiore By revocation – Dickinson v Dodds By death where contract involves personality of the offeror The effect of a promise to keep the offer open for a certain time or to give someone the right of first refusal- This will not be legally binding unless the offeree gave some payment to the offeror in return for the promise. Routledge v Grant c.f. Dickenson v. Dodds B. Acceptance This is an agreement to be bound by all the terms of the offer. To be valid, an acceptance must: Be exactly on the same terms of the offer and must not be varied otherwise it would be considered a counter offer – Hyde v Wrench Be certain and definite Be communicated in the manner implied or expressed in the offer and this may be verbal, in writing or by conduct –Powell v Lee, Brogden v Metropolitan Railway, Entores v Miles Far East Corp. Silence does not mean consent- Felthouse v Bindley, Instantaneous communication –acceptance is not communicated until received Communication by post – (The Postal Rule)- acceptance is valid once the letter is posted-Adams v Lindsell & Household Insurance v Grant Contrast Holwell Securities v Hughes Also note that acceptance cannot be withdrawn or revoked unilaterally. C. Consideration Definition In Currie v Misa, consideration was defined as a benefit to one party or a detriment to the other party. In Dunlop v Selfridge, consideration was defined as the price one party pays for the other party’s act or promise. According to the law of contract, any party who intends to enforce a promise given by the other party must have given consideration for that promise. 2 Types There two types of consideration, namely, executed and executory consideration. Essential elements of consideration For consideration to be valid, the following essential elements must be present: 1. Consideration must not be past – Roscorla. Thomas; Lampleigh v. Braithwaite 2. Consideration must move from promisee to the promisor (the party receiving the promise is the promisee and the party making the promise is the promisor). Tweddle v. Atkinson Note - most contracts are bilateral therefore, both parties would have to give consideration for their promises to be binding. 3. Consideration must be sufficient but need not be adequate. White v Bluett, Thomas v Thomas, Collins v Godefroy, Stilk v Myrick & Hartley v. Ponsonby 4. Consideration must not be illegal or vague. Pearce v. Brooks Note – Part – payment of a debt is not sufficient consideration – Pinnel’s case. Exceptions – Part-payment at an earlier date Part-payment at a different place Where goods or other material benefit accompany the part –payment Promissory estoppel is a defense where part-payment is considered in sufficient consideration – Central London Property Trust v High Trees House. D. Intention to Create Legal Relations In determining whether the parties intend legal consequences to follow their actions, the courts usually make two general presumptions capable of being rebutted by specific evidence to the contrary. 1. Parties in a domestic or social relationship are presumed not to intend legal consequences to follow their agreements unless the contrary is proved – Balfour v Balfour, Merit v Merit, Simpkins v Pays. 2. Parties in business or commercial relationship are presumed to have intention to create legal relations unless the contrary is proved –Look at Comfort Letters and 3 honour agreements-Kleinwort Benson v. Malaysia Mining Corporation Berhad & Jones v Vernons Pools. Defects in Contracts A contract may be defective even though the essential elements of a binding contract are present. The defect may be due to; 1 – lack of capacity to contract by one or both parties to the contract, 2 – the presence of vitiating factors, or 3 – illegality of the contract. Defects in the contract may render the contract void, voidable or unenforceable. In a void contract, the defect is considered serious in the eyes of the law that the law sees the contract as non-existent. Any property given or money paid will have to be returned. For a voidable contract, the defect is not considered so serious and therefore the contract is valid until the aggrieved party takes steps to make same void if he or she so desires. An unenforceable contract is valid but not enforceable against a vulnerable party. Contractual Incapacity This renders the contract unenforceable against the vulnerable party. 1. Minors – Contracts are generally unenforceable against a minor except the contract is for the purchase of necessary items.– Peters v Fleming, Nash v Inman. 2. Mentally impaired person – Contracts are unenforceable against a mentally impaired person only where the other party knew or should have known that the person was mentally impaired at the time of contract of contract. Vitiating factors Vitiating factors may either render the contract void or voidable. Vitiating factors are: misrepresentations, mistakes, undue influence and duress. 1. Misrepresentation – renders the contract voidable. Misrepresentations are untrue statements of fact made by one party before the contract was finalized which induced the other party to enter into the contract. Statement of law, opinion and intention are usually not considered statements capable of being misrepresented except in certain exceptional circumstances – Bisset v Wilkinson, Smith v Land & House Prop. Corp., Edington v Fitzmaurice, Esso Petroleum v Mardon 4 . Misrepresentation may be Innocent, Fraudulent-Derry v. Peek; Car & Universal Finance v. Caldwell or Negligent-Naughton v. O’Callaghan 2. Mistake An operative mistake makes the contract void. Mistake may be: Common mistake -Galloway v. Galloway Mutual mistake- Raffles v Wichelhaus Unilateral mistake by one party regarding the identity of the other party. A contract will not be void for mistaken identity unless the claimant can prove all of the following; 1. that the claimant intended to deal with some other person than the contracting party – King’s Norton Metal Co. v Edridge, Merrett & Co., Cundy v Lindsay and 2. that the other party was aware of the claimant’s mistake and 3. that when the contract was made the issue of identity was crucial – Phillips v Brooks, Lewis v Avery –Contrast Cundy v. Lindsay 3. Duress Duress is a common law doctrine whereby threats or use of violence to force a party to enter into the contract makes the contract voidable – Barton v Armstrong, Cumming v. Ince 4. Undue influence Where one party abuses his/her personal influence or authority over another to make the other party enter into the contract, the transaction is voidable if the influence is effective – Williams v Bayley, Tate v. Williamson. Where a fiduciary relationship exists between the parties, undue influence is presumed once the complaint can prove that the resulting transaction was disadvantageous to him. Alcard v. Skinner, Re Craig. Where no fiduciary relationships exists, the complainant must prove undue influence. ILLEGALITY & PUBLIC POLICY A contract that is otherwise valid may be unenforceable due to illegality or public policy. Illegal Contracts A contract is illegal if it involves the breach of some law or some defined morality. It is against the policy of the common law to allow an action on a contract containing an illegal or wrongful element. Examples of illegal contract are: 5 a) b) c) d) e) f) g) Contracts prohibited by statute Contracts to defraud the Income Tax Department Contracts involving the commission of a crime or tort- Beresford v Royal Insurance Company. Contract with a sexually immoral element- Pearce v. Brooks Contracts against the state Contract leading to corruption in public life Contracts which interfere with the course of justice The Consequences of Illegality The general rule is that no action can be brought on an illegal contract. Any party who participated in the performance of the illegal contract will be debarred from claiming damages for breach of contract. Money paid or property transferred is generally irrecoverable. Public Policy There are some contracts that are not illegal per se but which will be held void for being against public policy. These are; a) b) c) d) Contracts to oust the jurisdiction of the courts Contracts striking at the sanctity of marriage Contracts impeding parental duties Contracts in restraint of trade Consequences of Contract against Public Policy These contracts are not illegal in the full sense; instead they are void to the extent of the public policy contravention. As a result, unlike in the case of illegal contracts, money paid or property transferred is generally recoverable. The court will perform an act of severance, i.e., separating the valid part of the contract from the void part. Terms of Contract A contract is made up of terms offered by one party and accepted by the other party. Contracts usually consist of both express terms and implied terms. Express terms - These are terms in the contract that have been specifically communicated by a party to the contract. Communication may either be verbal or in writing, and both parties know or should know that these terms exist. 6 Implied terms – These terms are deemed to be part of the contract or are deemed to apply to the contract. These terms may be implied by Statute, Custom or the Courts. Conditions, Warranties and Innominate terms Implied and express terms may be further classified into conditions, warranties and innominate terms. Conditions are the most important terms, which form the main structure of a contract. These crucial terms must be pointed out to the other party before the formation of a contract is completed. Breach of conditions gives the wronged party a right to cancel the contract and claim compensation for any loss suffered. Warranties are minor terms of the contract, which are ancillary rather than crucial or important to the contract. A breach of warranty does not give the wronged party the right to refuse to perform his side of the obligation but rather, he will be entitled to claim compensation for any loss suffered as a result of the breach. Innominate terms are broad terms in the contract, which have not been categorized by the parties into conditions and warranties. The court is given the task in situations of breach to determine whether such terms are conditions or warranties. In order to make this decision the court takes various factors into consideration, which include the intentions of the parties and the extent of damage to the injured party. Poussared v Spiers, Bettni v Gye. Exclusion / Exemption Clauses Exclusion clauses are clauses stated in a contract by which one party seeks to limit or exclude himself from liability. For an exclusion clause to be effective, it must satisfy the following three criteria: 1. 2. 3. It must be incorporated within the contract It must be clear and unambiguous It must not be rendered ineffective by statute For a party to be bound by an exclusion clause irrespective of whether the contract is verbal or in writing. Olley v Marlborough Court Hotel, Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking, Chapelton v Barry UDC. Note – That a party may be deemed to have implied notice from past dealings – Kendall v Lilllico That the more onerous the terms, the greater the degree of notice required – Interfoto Picture Library Ltd. V Stiletto Productions 7 That customers are deemed to have constructive notice of the content of any contractual documents they sign whether they have read it or not – L’Estrange v Graucob Customers cannot claim they misunderstood a clause unless the seller helped to cause misunderstanding – Curtis v Chemical Cleaning & Dyeing Co. Usually, a party cannot exclude liability for a fundamental breach; however in some circumstances, the court may allow the exclusion clause to protect the party in breach – Photo Production Ltd v Securior Transport Ltd Privity of Contract Persons who are not parties to the contract cannot enforce the contract; neither can the burdens of the contract be enforced against them. They are said not to be privy to the contract or have privity of contract. Tweddle v Atkinson and Beswick v Beswick. Some exceptions to the doctrine of privity of contract 1. 2. 3. 4. Agency. Third-party insurance Assignment of contractual rights Trusts DISCHARGE OF CONTRACT Method of Discharge A party who is subject to the obligations of a contract may be discharged from those obligations in any of the following ways: (a) (b) (c) (d) Performance Agreement Breach Frustration Discharge of Performance is the normal method. Where the promisor is unable or unwilling to give more than partial performance there is no discharge. The practical effect of this rule is that where a contract provides for payment by one party after performance by the other, no action to recover payment may be maintained until performance is complete, nor will an action for a proportionate payment be available on the basis of quantum meruit. Cuter v Powell. Performance must be complete to bring a case. Moore & Co. v Laundaeur. Exceptions include divisible contracts and substantial performance Acceptance of Partial Performance 8 If the promisee voluntarily accepted less than complete performance where he had genuine freedom of choice, the promisor is entitled to claim payment on a quantum meruit basis. Prevention of Performance Where a party is prevented from completing his undertaking because of some act or omission of the other party, the party who has been prevented from performing may either sue for damages or for payment on a quantum meruit basis. Discharge by Agreement A contract may provide for its own discharge by inclusion of a clause imposing a condition precedent or condition subsequent or it may contain a term giving one or both parties the right to end the agreement by giving notice to the party (e.g. contracts of employment). Condition Precedent prevents the contract from coming into operation unless the condition is satisfied. The condition becomes binding – it is contingent to something occurring. (1) Hargraves Transportation Ltd. V Lynch (2) Pynn v Campbell Condition Subsequent provides for the discharge of obligations outstanding under the contract in the event of a specific occurrence. Mutual Agreement Both parties can agree to accept something different where there has been accord and satisfaction that the former obligation is discharged. Where a contract is partially/wholly executed, discharge of such contract must be supported by consideration or made under seal. The party to whom something is owed may agree to accept something different in place of the former obligation; but where the subsequent agreement by which one of the parties consent to accept something different in place of the original obligation is under threat, the old obligation remains undischarged. Discharge of Breach Refusal or substantive failure by one party to perform his obligations, releases the other party from his obligations and renders the party in default liable for breach of contract; The general principle is that the breach must be a breach of condition of the contract and not a breach of warranty. In the case of a Breach of Condition, the injured party can treat 9 the contract as being automatically discharged in which case he cannot also sue for damages or breach of contract since he has indicated his willingness to regard the contract as dead and has therefore waived his right to action for damages. However, if he has incurred expenses on the contract he may bring a quasi contractual quantum meruit action for compensation. In the case of Breach of Warranty the injured party can sue for damages but must go on with the contract – he does not have the right to rescind or terminate the contract. If a person chooses the latter course he keeps the contract alive and should immediately commence action to enforce it, i.e., sue for damages or specific performance. Discharge by Acceptance of Breach A breach does not, in itself discharge a contract but it may, in circumstances give the innocent party the right to treat it as discharge if he so wishes. There are several forms of breach of contract: (1) (2) failure to perform the contract which is the most usual form - as where a seller fails to deliver goods by the appointed time; express repudiation – where one party states he will not perform is part of the contract. (i) (ii) Rochester v De LaTour Omnium Enterprises v Sutherland Remedies for Breach of Contract The standard remedy for breach of contract is the award of damages as compensation for the loss suffered by the injured party. As an alternative, the injured party, in some cases, claim payment for the value of what he has done (quantum meruit) or seek a court requiring the defendant to perform the contract (specific performance). Where appropriate, the plaintiff may apply for declaration that the contract has been rescinded or obtain restitution of property which he has transferred. The right to remedy for breach of Contract is subject to time limit (limitation) i.e. the right of action for breach, may be statute barred because of lapse of time. As a general rule the amount awarded as damages is what is needed to put the plaintiff in the position he would have achieved if the contract had been performed. If for example there is a failure to deliver goods at a contract price of $100 per ton and similar goods are obtainable at a market price $110 per ton, damages are calculated at the rate of $10 per ton. (Sale of Goods Act 1979 s. 51) More complicated questions of assessing damages can arise but the general principle is to compensate for financial loss. 10 Lapse of Time The right to sue for breach of contract becomes statute barred six (6) years from the date of the breach (or 12 years if the contract is by deed). The plaintiff’s rights cease to be enforceable at law but right to liquidate a sum may be revived by acknowledgement in writing the debtor even if made after the limitation period has expired. In the following situation the 6 –year period does not begin at date of breach but later:(i) (ii) if plaintiff is a minor or of unsound mind at the time of the breach, the 6-year period begins only when his disability ceases. Once begun it is not subsequent disability; if the defendant or his agent conceals the right of action by fraud, the 6 year period begins only when plaintiff discovered or could by reasonable diligence, have discovered the fraud. (Case Applegate v Moss 1970) Discharge by Subsequent Impossibility Contra Supervening Impossibility Subsequent impossibility is a basic common law rule that a party is not discharged from his contractual obligation merely because performance has become more onerous or impossible owing to some unforeseen event. The general rule is that contractual obligations are absolute and if a party wishes to protect himself from subsequent difficulties in performance, he should so stipulate for that protection. The Doctrine of Frustration has, however, developed a number of exceptions to the general rule of absolute contractual liability. Where without the fault of either party some totally unforeseen event takes place which renders future performances either impossible or completely impracticable, the doctrine of frustration will apply. Limited circumstance in which frustration occurs include: (i) where the basis on which the contract was predicated is totally destroyed. Taylor v Caldwell (Theatre burnt down.) (ii) The Non-occurrence of an event Krell v Henry (non-recovery of money.) (iii) Death or Illness – A contract for personal services may be frustrated by death or unduly prolonged illness of employee. Temporary illness or incapacity will not, in most cases, discharge the contract unless it can be shown that those go to the root of the contract – i.e. a condition of the contract. 11 (iv) (v) Government interference – where government prohibits performance for such a period that it would be unreasonable to expect performance after the prohibition ceases; e.g. change in law (Avery v Bowden Self-induced Frustration – The doctrine of frustration will not apply where frustration is self-induced – Maritime National Fish Ltd v Ocean Sea Trawlers. The doctrine of frustration may also not be applicable where express terms in a contract cover the contingency complained of – British Movie News v London Cinema Ltd. 12