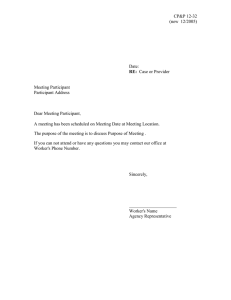

Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 19 (2021) 86–91 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jcbs Empirical Research Acceptance and commitment group therapy among Saudi Muslim females with mental health disorders Mashael Bahattab a, b, Ahmad N. AlHadi c, d, * a Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont, United States Psychiatry Department, King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia c Psychiatry Department, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia d SABIC Psychological Health Research and Applications Chair (SPHRAC), Psychiatry Department, College of Medicine, King Saud University Medical City, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia b A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: Acceptance and commitment therapy Saudi Arabia Muslim Depression Anxiety Introduction: This study aimed to examine the potential acceptance, feasibility, and clinical impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in a group format for Saudi women who struggle with depression and anxiety disorders. The findings may help clinicians in Saudi Arabia and other Muslim communities to be aware of ACT as an emerging therapeutic approach for treating depression and anxiety and related conditions. Methods: Eight women with depression and anxiety in Riyadh city in the year 2017 were included in the study. A qualitative design was used for this study to test the possible effectiveness of and receptivity to a group treatment protocol based on ACT among Muslim Saudi females. The ACT group met for one 1.5-h session per week for 8 consecutive weeks. Thematic analysis techniques were employed. To explore and describe participants’ expe­ riences, the data were analyzed for emerging themes that were then identified and coded. Results: The results showed preliminary support that ACT could be an effective, well-received therapeutic approach for Muslim Saudi women as far as decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety and making an overall positive change in their attitudes and behavior, as well as increasing self-confidence. Conclusions: ACT group therapy was well appreciated and viewed as being culturally and religiously acceptable by the Saudi Muslim female participants. The present results support the notion that ACT is well appreciated as a potential means of reducing depression and anxiety and can help enhance positive emotions and increase the psychological well-being of Saudi women. 1. Background Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is considered an effective thera­ peutic method for depression and anxiety disorders. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a new therapeutic form of CBT that, ac­ cording to a growing number of studies, offers remarkable possibilities and perspectives in understanding and treating depression and anxiety (Kohtala, 2015; Boone & Myler, n.d.; Folke, Parling, & Melin, 2012; Rahmani & Rahmani, 2015; Dousti, Mohagheghi, & Jafari, 2015; and Azadeh, Zahrani, and Besharat, 2016). Individuals who have symptoms of either depression or anxiety usually struggle because they try to reject or avoid their unwanted inner experiences. ACT refers to this rejection as psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance, which means the inability to accept distressing thoughts and feelings as they arise (Arch et al., 2012; Bluett et al., 2014; Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). In contrast to psychological inflexibility, ACT has proposed a model based on psychological flexibility that consists of six core pro­ cesses: flexible attention to the present moment, chosen values, committed action, self-as-context, defusion, and acceptance (Luoma, Hayes, & Walser, 2007). According to Tanhan (2014) and Yavuz (2016), there are a few shared characteristics between the fundamental ideas of ACT and Islam, which may make ACT a fitting choice for helping Muslim clients. The commonality between the six core processes of ACT and Muslims’ beliefs and practices will be explained. Being in the present moment is “the ability to create space to be in * Corresponding author. SABIC Psychological Health Research and Applications Chair (SPHRAC), Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, King Saud University Medical City, King Saud University, POBox 7805(55), Riyadh, 11472, Saudi Arabia. E-mail addresses: mashaelbahattab@gmail.com (M. Bahattab), alhadi@ksu.edu.sa (A.N. AlHadi). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.01.005 Received 27 September 2020; Received in revised form 9 January 2021; Accepted 17 January 2021 Available online 20 January 2021 2212-1447/© 2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of Association for Contextual Behavioral Science. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). M. Bahattab and A.N. AlHadi Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 19 (2021) 86–91 the here-and-now in an open, receptive, and nonjudgmental mood” (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2012, p. 205). This concept is significant in Islam, in which it could be practiced in several ways, such as the bodily attitude prayers. When engaging in the correct way of prayer, Muslims should be focused on every movement and word they recite while praying and not focused on their worries and concerns. However, when it happens that someone gets fused with any aspect of their internal experience (thoughts, feelings or sensations), Islamic scholars recom­ mend that a Muslim should come back to what they are reciting and doing without judging themselves (Tanhan, 2014). The observing-self is “understanding/experiencing the self as a continuity of consciousness beyond one’s feelings, thoughts, sensations, experiences, etc.” (Hayes et al., 2012, p. 206). It is one of the other two aspects of self in ACT; the conceptualized self (or self-as-content) and the self that is aware of all content (self-as-context) (Hayes et al., 2012). All the three types of self from the ACT perspective could be seen in Islam as well; the Holy Qur’an indicates that everyone has a multilevel sense of self (nafs) (Yavuz, 2016). Defusion is “making closer contact with verbal events as they really are, not merely as what they say they are” (Hayes et al., 2012, p. 244). According to ACT, defusion can be created through metaphors and experiential activities, while in Islam, defusion can be facilitated through religious activities such as prayers, stories, and sacred texts to help the individual to look at thoughts, feelings, sensations as they are, not as if they were wholly real (Tanhan, 2019). Acceptance is “the willingness to experience inner states, regardless of whether they are experienced as pleasant or unpleasant” (Hayes, 2010, p. 206). One of the main concepts in Islam is called sabr. The purpose and function of sabr is the willingness to accept unwanted inner or external experiences (Yavuz, 2016). This can be seen through the word alhamdulillah, one of the most common words that Muslims use in all conditions regardless of pleasant or unpleasant experience/situations. This word means taking time/space for that specific experience rather than running away from it (Tanhan, 2019). Value is “clarifying what is important to the way one desires to live life” (Hayes et al., 1999; as cited in Springer, 2012, p. 207). The kinds of value-based questions in ACT are in line with Islamic principles. Islam encourages people to think of their actions and goals, as well as what they want to stand for (Tanhan, 2014). Committed action “involves flexible moving toward goals that are consistent with one’s values” (Hayes et al., 1999; as cited in Springer, 2012, p. 207). Similar to ACT, Islam stresses that Muslims should create their goals according to their values. The Holy Quran emphasizes the importance of taking actions in almost all verses that mention faith, which indicates the importance of creating goals according to values and taking actions from a contextual and mindful perspective. (Tanhan, 2014). All of the above points to the similarities between ACT and Islamic principles, which is the main source and guide Saudis refer back to. Given this, the author thought that ACT would have high probability of enhancing the mental health in Saudi Arabia in general and specifically for those with depression and anxiety keeping in mind higher prevalence among females. In a study that aimed to explore the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among visitors to faith healers in Saudi Arabia, the authors found that depression and anxiety disorders were the most common disorders among the study participants (Alosaimi et al., 2014). We aimed in this study to identify the applicability and clinical impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in a group format for Saudi women who struggle with depression and anxiety disorders. psychiatrists and psychologists working at King Saud University Medical City. Individuals interested in participating contacted the researcher via telephone or e-mail (as indicated on the flyer). An initial intake inter­ view was scheduled to briefly explain the study format to interested individuals. A consent form was then provided to those who remained interested in taking part in the study. Once a total of eight individuals had provided their consent to participate, the start date and time for the group sessions was sent to the participants. At the end of the study, upon completion of the research, a debriefing statement was provided to all participants. 2.2. Design This study used a qualitative design. Data were gathered through interviews with eight Saudi females who had a diagnosis of depression and anxiety. The possible effectiveness of and receptivity to ACT among Muslim Saudi females were examined using a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) of all participant narratives drawn from interviews conducted following their participation in the eight weekly ACT group therapy sessions. The length of the interviews varied somewhat from one participant to another; some gave relatively short answers while others elaborated more. Owing to a scheduling issue, sessions 7 and 8 were held on the same day during week 8. All interviews were conducted, recor­ ded, and subsequently transcribed by the first author, M. B., who also did the coding process. 2.3. Research protocol The method of qualitative analysis was Braun and Clarke’s (2006) Thematic Analysis (TA) process, which involves the following six steps: 1) Familiarizing yourself with your data, 2) Generating initial codes, 3) Searching for themes, 4) Reviewing themes, 5) Defining and naming themes, and 6) Producing the report on the aim of the study. Data were collected and these six steps were utilized to find common themes that emerged from the responses given by the participants. Themes that surfaced amongst multiple interviews suggested generalizability, at least across this sample. 2.4. Confidentiality The identities of the participants and any revealing information were kept anonymous by implementing a numeric coding system to store data. Any personally identifying information was kept confidential. All the notes from the interviews were secured by a password on a private laptop. Collected data were used only for research purposes. Ethical approval was granted from the King Saud University institutional review board before data collection began. No incentives were offered to participants. 3. Materials and measures A list of open-ended questions, presented in Table 1, was asked following the eight-week intervention. Scheduled individual face-toface interviews took approximately 60 min to complete and explored participants’ experiences with taking part in the ACT group therapy. All interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis. 3.1. Procedure As noted, the participants were eight Saudi females aged 18–60 years, with a diagnosis of depression or/and anxiety disorders. All the participants were from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The ACT group therapy consisted of eight weekly meetings. Sessions were given utilizing a protocol that Matthew S. Boone and Cory Myler created for a depression and anxiety group (Boone & Myler, n.d.); all the 2. Methods 2.1. Participants A total of eight Saudi females who had a diagnosis of depression and anxiety were recruited to participate in the study with the assistance of 87 M. Bahattab and A.N. AlHadi Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 19 (2021) 86–91 evaluate the potential acceptance, feasibility, and clinical impact of ACT group therapy on them. In terms of clinical supervision, the student was supervised as fol­ lows: first, a Licensed Clinical Psychologist, through VSee (combining HIPAA video chat, device integration, and health data visualization); and second, direct clinical supervision conducted by a consultant psy­ chiatrist (second author) who had received fellowship training in psy­ chotherapy and ACT. Previous research states that ACT is effective among several pop­ ulations who suffer from various mental health disorders (Abbasi et al., 2015; Azadeh, Zahrani, and Besharat, 2016; Bluett, 2017, p. 2014Molavi, Mikaeili, Rahimi, & Mehri,; Vakili & Gharraee, 2014). Table 1 Interview questions for participants. Questions for Participants in English Questions for Participants in Arabic • Self-Description: 1. How did it feel to be in ACT therapy? • Changes: 2. Have you noticed any specific changes in yourself after having participated in the ACT therapy? For example, are you doing, feeling, or thinking differently from the way you did before? 3. What specific ideas, if any, have you gotten from therapy so far, including ideas about yourself or other people? Have any changes been brought to your attention by other people? 4. Has anything changed for the worse since ACT therapy began? 5. Is there anything that you wanted to change that hasn’t changed since ACT therapy began? • Problematic Aspects: 6. Have you found anything about ACT therapy that has been hindering, unhelpful, negative or disappointing for you? These items may include general aspects and/or specific events. 7. Were there things in ACT therapy that were difficult or painful, but still OK or perhaps helpful? What were these? 8. Was anything missing from ACT therapy? What would have made your therapy more effective or helpful? • Religious and cultural aspects: 9. Do you think the six core processes of ACT therapy are consistent or inconsistent with Islamic principles? 10. What is your perspective regarding the group format of ACT therapy? • ﻭﺹﻑ ﺫﺍﺕﻱ: 1. ﻙﯼﻑ ﻙﺍﻥﺕ ﺕﺝﺭﺏﺕﻙ ﻡﻉ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺍﻝﺝﻡﻉﻱ؟ • ﺕﻍﻱﻱﺭﺍﺕ: 2. ﻩﻝ ﻝﺍﺡﻅﺕ ﺃﻱ ﺕﻍﻱﺭﺍﺕ ﻑﻱ ﻥﻑﺱﻙ ﺏﻉﺩ ﻡﺵﺍﺭﻙﺕﻙ ﻑﻱ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﮪﻝ ﮪﻥﺍﻙ ﺃﻱ:ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺍﻝﺝﻡﻉﻱ؟ ﻡﺙﻝ ﺕﻍﻱﻱﺭ ﻑﻱ ﻡﺵﺍﻉﺭﻙ ﺃﻭ ﺃﻑﻙﺍﺭﻙ؟ 3. ﮪﻝ ﮪﻥﺍﻙ ﺃﻱ ﺃﻑﻙﺍﺭ ﻡﺡﺩﺩﺓ ﺍﻙﺕﺱﺏﺕﯼﮪﺍ ﻡﻥ ﺥﻝﺍﻝ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﺃﻑﻙﺍﺭ ﻉﻥ ﻥﻑﺱﻙ ﺃﻭ ﻉﻥ،ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺃﺵﺥﺍﺹ ﺁﺥﺭﻱﻥ؟ ﻡﺍ ﻩﻱ؟ 4. ﮪﻝ ﮪﻥﺍﻙ ﺃﻱ ﺕﻍﻱﻱﺭﺍﺕ ﻝﻝﺃﺱﻭﺃ ﻡﻥﺫ ﺍﻥﺽﻡﺍﻡﻙ ﻝﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺍﻝﺝﻡﻉﻱ؟ 5. ،ﮪﻝ ﮪﻥﺍﻙ ﺃﻱ ﺕﻍﻱﻱﺭﺍﺕ ﺃﺭﺩﺕ ﺡﺩﻭﺙﻩﺍ ﻭﻝﻙﻥﻩﺍ ﻝﻡ ﺕﺡﺩﺙ ﻡﻥﺫ ﺏﺩﺀ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺍﻝﺝﻡﻉﻱ؟ 4. Results Seven of the eight study participants were included in the ACT group therapy. One participant who had social anxiety and was afraid of having panic attacks if she participated received the ACT therapy intervention individually following the same group protocol. A brief description of all research participants is provided here, with numbers to protect participants’ anonymity and confidentiality. All participants fit the criteria of being Saudi Muslim adults who have depression or/and anxiety disorders. Also, the participants’ ages were between 21 and 46 years old. Most of them had bachelor’s degrees, while two of the participants were medical students. Through data analysis, the following themes emerged: (1) the par­ ticipants’ perceptions of ACT intervention; (2) ACT in Saudi culture and Islamic society; and (3) the benefits of ACT in general as well as in terms of its specific components: acceptance, cognitive defusion, being pre­ sent, observing self, values, committed actions, practicing mindfulness, and the behavioral effect. All themes were evidenced across the 8 study participants (Table 2). 6. ﮪﻝ ﻭﺝﺩﺕ ﺵﻱﺉﺍ ﻑﻱ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺍﻝﺝﻡﻉﻱ ﻙﺍﻥ ﻝﻩ ﺃﺙﺭ ﺱﻝﺏﻱ ﺃﻭ ﻍﻱﺭ ﻡﻑﻱﺩ ﺃﻭ ﻡﺥﻱﺏ ﻝﻝﺁﻡﺍﻝ؟ ﻑﻱ ﺝﻭﺍﻥﺏ:ﺍﻝﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺃﻭ ﺃﻥﺵﻁﺓ ﻡﺡﺩﺩﺓ ﻡﺙﺍﻝ ﺃﺡﺩﺍﺙ ﻡﻉﻱﻥﺓ،ﻉﺍﻡﺓ. 7. ﮪﻝ ﻙﺍﻥ ﻩﻥﺍﻝﻙ ﺃﻱ ﺝﻭﺍﻥﺏ ﻡﺅﻝﻡﺓ ﺃﻭ ﺹﻉﺏﺓ ﻑﻱ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﻝﻙﻥﻩﺍ ﻙﺍﻥﺕ ﻡﻑﻱﺩﺓ ﻥﻭﻉﺍ ﻡﺍ؟،ﺍﻝﺝﻡﻉﻱ ﻡﺍ ﻩﻱ ﺕﻝﻙ ﺍﻝﺝﻭﺍﻥﺏ؟ 8. ﻡﺍﺫﺍ ﻙﺍﻥ ﻱﻥﻕﺹ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺍﻝﺝﻡﻉﻱ ﻝﻱﻙﻭﻥ ﻡﻑﯼﺩﺍ ﻭﻑﻉﺍﻝﺍ؟ • ﺍﻝﺝﻭﺍﻥﺏ ﺍﻝﺩﻱﻥﻱﺓ ﻭﺍﻝﺙﻕﺍﻑﻱﺓ: 9. ﮪﻝ ﺕﻉﺕﻕﺩ ﺃﻥ ﺍﺱﺕﺭﺍﺕﻱﺝﻱﺍﺕ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺍﻝﺱﺕﺓ ﺕﺕﻡﺍﺵﻯ ﻡﻉ ﻡﺏﺍﺩﺉ ﺍﻝﺩﻱﻥ ﺍﻝﺇﺱﻝﺍﻡﻱ؟ 10. ﻡﺍ ﻩﻭ ﺭﺃﻱﻙ ﻑﻱ ﻥﻭﻉ ﻉﻝﺍﺝ ﺍﻝﺕﻕﺏﻝ ﻭﺍﻝﺍﻝﺕﺯﺍﻡ ﺏﺵﻙﻝ ﺝﻡﺍﻉﻱ؟ 4.1. Theme 1: participants’ perceptions of ACT intervention The effectiveness of the therapy format was received differently. An advantage of the group format that was highlighted by several of the participants was the benefit of sharing each other’s experiences and feelings. Participant 6 noted: “I am not good at expressing my thoughts and feelings, so the group therapy helped me a lot.” Participant 2 also added, “hearing the members’ values helped me with clarifying my values.” Participant 3 thought that in individual therapy format, she would not have understood that what she has been experiencing is normal. Both Participants 5 and 3 emphasized another benefit of being involved in group therapy, which is gaining a new perspective. How­ ever, Participant 5 shared that she believed the negative side of group therapy was getting exposed to new fears as a result of listening to the members’ experiences. Another negative aspect that Participant 5 noticed is that she started doubting herself when the other members said that they understood the concepts and could apply the techniques. The same Participant 5, as well as Participant 8, who was in the individual therapy, indicated that they thought that therapy in an individual content was translated to Arabic and the sessions led in Arabic, including the presentation slides and the mindfulness recordings. The sessions were 1.5 h long and included the following ACT themes: Session 1: Contact with the present moment; Session 2: Defusion; Session 3: Acceptance/willingness; Session 4: Values; Session 5: Observing self; Session 6: Committed action; Sessions 7/8: all processes, with a focus on building greater patterns of committed action in the service of values. Each group meeting was organized generally as follows: opening mindfulness exercise, review of LIFE Exercises, assignments from the previous week, didactic portion with group discussion, experiential ex­ ercise with group discussion, and assignment of LIFE exercises for the next time. The didactic portion ended in the fifth session and was reinforced by the readings. More focus on the group “process” and hereand-now discussion occurred in the second half. The therapist was a female Master’s-level psychology student at Notre Dame de Namur University. She had completed her one-year practicum. The student therapist received about 74 h of training on ACT. There were no expected risks for participants. If they became un­ comfortable in any way, they were free to discontinue their participation in any group session and/or the study itself. Also, a referral for partic­ ipants was provided should they become distressed at any point in the study. The referral was a consultant psychiatrist (second author), who was the direct clinical supervisor at the study site. Upon completion of the ACT group therapy, each member of the group was interviewed to Table 2 Participants’ quotes for each theme. 88 Example of each theme The participants’ quotes Theme 1: Participants’ Perceptions of ACT Intervention Theme 2: ACT in Saudi Culture and Islamic Society Theme 3: Benefits of ACT Participant 6: “There are things that I regret not doing even though I want so badly to do them.” Participant 4: “I am sure that ACT strongly supports the Islamic principles.” Participant 5: “I thought there was no solution for what I am going through, but ACT made me realize that there are still techniques that I haven’t tried before and could help me to cope.” M. Bahattab and A.N. AlHadi Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 19 (2021) 86–91 format is more helpful because they can focus on themselves. Another aspect about which the participants had different percep­ tions was the protocol. Most of the participants had the same opinion in terms of the insufficient length of time of the sessions as well as the number of sessions. Another element that was pointed out was the lack of visual aids in the presentation. Most of the participants agreed that the sessions that included PowerPoint presentations and more photos were more attractive to them and helped them comprehend the content. Participant 2 thought that the protocol could have been enriched even more through the presentation of details of case studies that actually benefitted from ACT. An additional component of the protocol that the participants highlighted was the experiential exercises during sessions. Participant 4 reported: “In the session that you gave me a paper to write down my painful thoughts and feelings, I began to cry when I saw them in front of me on the paper. I saw the suffering that was causing me inner pain.” Participants also shared their experiences when they were asked to imagine themselves in their 80s and to think about a few value-based questions that were provided to them. The last component that the participants discussed regarding the protocol was the at-home assignments. The assignments were various readings, mindfulness exercises, and some paperwork. Participant 7 reported that the assigned book in the protocol helped to further clarify the points that were hard to understand during the sessions. Also, Participant 4 stated that having a reading assignment at home helped her to strongly grasp the content in the session, which made her feel comfortable. learned to first understand my feelings which helped me to accept them.” Cognitive Defusion. Participants had various perceptions of the cognitive defusion strategies. Participant 3 thought that the strategies were helpful in terms of distinguishing between what is fact and what is an opinion that she has about herself or that other people have about her, and then evaluating whether or not it is beneficial to consider this opinion. Also, Participant 1 reported, “I liked the idea that our thoughts are different than ourselves.” Being Present. Participants stated that when they constantly remind themselves to bring their awareness to the present moment, they feel more relaxed, which helped them appreciate even the small things in their lives. Participant 5 thought that ACT helps to take the most of life by being present in the moment, “so that we do not miss it and have regrets later.” Observing Self. The observing-self component of ACT was repeat­ edly mentioned in the participants’ feedback about their experience. Participant 2 thought that learning about the observing-self part of her was a significant discovery. Participant 3 stated that knowing about the observing-self helped her avoid engaging with her unhelpful thoughts. Most of the participants mentioned how the weather metaphor reso­ nated with them. Participant 7 reported: “I realized that there is an original me, regardless of how I feel.” Values. The participants thought that ACT helped them clarify their values, which were not present for some of them. Participant 5 stated that she didn’t tend to pay attention to what she values because she was not aware of the importance of having her values as a guide for what she should or should not do. Participant 2 reported that clarifying her values helped her better regulate her emotions. She explained: “Now when I am sad, I sit with my sad feelings for a moment and then I try to remind myself of my goals and where I want to be in 10 years.” Committed Actions. Participant 3 stated that maintaining a dis­ tance between herself and her thoughts gave her space to think about whether or not the thoughts were useful in terms of moving toward her values. Participant 2 agreed that understanding the nature of feelings helped her allow them to be, and at the same time think of the next step to move toward her goals as well as where she wants to be in 10 years. Participant 6 also said: “I learned that I cannot change people around me, but I can change myself.” Practicing Mindfulness. The other component of ACT that most of the participants appreciated was the mindfulness exercises. Participant 7 stated that practicing mindfulness helped her regain her selfempowerment and made her calmer, more relaxed, and active when she got up in the morning. Participants commented on how mindfulness helped them with their sleep problems. Participant 7 said, “I started listening to Sound Cloud recordings before I went to bed, and I noticed that the thoughts that used to come to my mind, even those coming on a day of trouble, became much less; now I can fall asleep in an hour and a half at maximum.” Participant 5 and another participant did express a negative aspect of practicing mindfulness. Participant 5 reported: “Some of the mindfulness exercises caused me panic attacks. Facing my thoughts was what made me panicked.” Behavioral Effects. The participants discussed several changes they noticed throughout the eight weeks. Participant 7 reported that ACT helped her with her weight issue; she lost a few kilograms, which had always been one of her goals. Participant 4 shared that even though she realized that her situation was tough and made her cry, she is now much calmer because she is more willing to accept her feelings. Finally, Participants 3, 7, and 2 indicated that the quality of their sleep had clearly improved. 4.2. Theme 2: ACT in saudi culture and Islamic society All the participants reported feeling that ACT was in line with Saudi society as well as Islamic principles. They also mentioned that there were several scripts in the Quran and Hadith (the major source of guidance for Muslims apart from the Quran) that support the ACT core processes. Participant 5 noted that, “in this group therapy, we were given therapeutic strategies and concepts that we have already practiced and believed.” Participant 1 reported that acceptance is a significant concept in Islam, but that ACT presented it in a different form. 4.3. Theme 3: benefits of ACT Participants indicated that they noticed several benefits of being involved in ACT group therapy in general and as a result of each component of ACT in particular. Participant 5 thought that ACT teaches important life skills even for those who do not struggle with mental health disorders. Participant 2 shared her experience with ACT: “I feel like my brain has enlarged learning about all of this.” Participant 7 thought this experience made her feel more confident. She also said, “I felt like I needed someone to save me, and I was actually saved.” Acceptance. The participants reported that the concept of accep­ tance was a bit of a challenge for them because they were used to rejecting and escaping from their pain in different ways. Participant 7 reported, “I could not accept the idea of accepting my pain. I thought acceptance was just a philosophical word, but I have realized later that it is true, and it is in my hands to choose to accept.” The participants indicated that they had a strong belief that, for them to live meaningful lives, they should first get rid of their painful thoughts and feelings. They also stated that what significantly helped them accept their unwanted thoughts was their awareness of the nature of thoughts and the fact that they come and go. Also, most of the participants expressed their appreciation of the fact that pain is normal, which made it easy for them to hold their pain while simultaneously moving forward. Participant 4 reported, “I believe that when I accept my feeling, I gain more self-confidence.” Participant 2 stated that acceptance gave her a new perspective, which helped her to deal with her overreacting issue. She also added: “Therapists used to tell me to be positive, but with ACT I 5. Discussion Participants reported positive results—both personal and inter­ personal—from their work in the ACT group therapy. These perceived benefits indicated that ACT was associated with a positive change in 89 M. Bahattab and A.N. AlHadi Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 19 (2021) 86–91 anxiety and depression symptoms, in addition to the positive changes in diet, sleep, psychological flexibility, emotion regulation skills, valuebased living, and mindfulness. The results of this study regarding the effectiveness of ACT group therapy among Muslim women in Saudi Arabia are aligned with the findings reported in studies conducted among non-Muslim societies, including the work of Folke et al. (2012), Kohtala (2009), and Dousti et al. (2015). Also, these findings are in line with studies carried out among members of Iranian Muslim society, including studies by (2014)Molavi, Mikaeili, Rahimi, & Mehri, Rahmani and Rahmani (2015), and Azadeh, Zahrani, and Besharat (2016). As evidenced by the data acquired from interviews with the Saudi Muslim female participants, the group format was reported as being highly effective and powerful in terms of the validation and support provided as a result of sharing and listening among the group members. Regarding the links between ACT and the Muslim Saudi society, the participants implied that ACT supports Islamic values and that it actu­ ally helped them become the Muslims they wanted to be. In particular, they mentioned the concept of acceptance and its importance, as well as benefits that are emphasized by many scripts in both the Quran and Hadith. Another factor worth mentioning about this group therapy process is that the presented metaphors were received in a very positive way. According to Dwairy (2009), one of his Muslim-Arab clients achieved a significant change in his belief system, self-esteem, happiness, re­ lationships, and satisfaction with himself and with God using metaphor therapy based on the client’s own culture and religion. Even though the metaphors based on culture and religion was proven to be effective, the therapist used only the metaphors that were provided in the protocol without any adaptation. However, since both the participants and the therapist share the same faith background, mentioning the religious aspect from time to time was inevitable but not a focus. Also, the participants commented on the protocol that was used for the intervention. They appreciated the presentation slides, especially those that had more pictures. The results of this study encouraged having ACT-based therapy that consists of eight sessions. Though some participants stated that eight sessions were not enough, they indicated how valuable and helpful the intervention was for them. This finding is supported by studies in the literature review, which indicated that providing eight sessions or fewer, such as six or four, was still signifi­ cantly helpful (Folke et al., 2012; Kohtala, 2009; Dousti et al., 2015; Shaker, Rahimi, & Zare, 2016; Abbasi et al., 2014). The participants also found that the experiential exercises, as well as the group discussions, were helpful and shared that the assignments had enriched and deepened their understanding. They specifically appreci­ ated the reading and mindfulness exercises. Participants reported on how mindfulness exercises improved their sleep and emotional regula­ tion skills and led to positive changes in terms of a greater appreciation for life. A similar outcome in terms of the effectiveness of the mindful­ ness exercises was reported in a study of mindfulness-based stress reduction among Emirati Muslim women (Thomas, Raynor, and Bakker, 2016). The participants also said that ACT gave them a great deal of awareness and a new perspective in terms of the nature of their thoughts and feelings. They claimed that this awareness helped them move for­ ward depending on their values. Also, their responses indicated that awareness of their thoughts and feelings seemed to have improved the overall quality of their lives, which is aligned with the findings reported in the study of the Quality of Life Improvements after Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Nonresponders to Cognitive Behavioral Ther­ apy for Primary Insomnia (Hertenstein et al., 2014). Participants thought that the ACT core processes gave them the necessary life skills and increased their value-based living. Participants did report several challenges associated with the first process of the group therapy. The fact that they would experience a group therapy format was an anxiety-provoking for some of them. In addition, for two participants, the mindfulness exercises seemed to be a trigger for their panic attacks. Another challenge that the participants experienced was with the concept of acceptance. Some of the partici­ pants found it difficult to deal with their painful thoughts and feelings with openness and without judgment. More studies are needed to better understand how the six core pro­ cesses match the beliefs of Islam. Also, considering the small sample, more studies with more participants are required. A suggestion that was also proposed by Tanhan (2014) is that because ACT uses several met­ aphors, it would be helpful to conduct future studies about metaphors from Islam that might be used within the ACT perspective. 6. Conclusions Despite the relatively small sample size, the ACT group therapy was well appreciated and viewed as being culturally and religiously acceptable by the Saudi Muslim female participants. Also, the present results support the idea that ACT is well appreciated as a potential means of reducing depression and anxiety among Saudi women. Addi­ tionally, the results lend preliminary support to the notion that ACT can help enhance positive emotions and increase the psychological wellbeing of Saudi women. This research topic was specifically chosen because the researcher has strong connections to the studied population and wants to bring mental health services to this group. The themes discovered here help to achieve the desired goal of exploring a new therapeutic approach that could assist people with mental disorders in Saudi Arabia and that they would accept as a culturally appropriate approach. Ethics approval and consent to participate Approved by the ethical committee of The College of Medicine at King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Informed consent was preceding the survey questions containing the aim of the study and the participant’s right to withdraw at any time without any obligations towards the study team. Consent for publication Not applicable. Availability of data and materials Data related to this study are presented in the results section. Raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Funding The Funding of this research was obtained by the SABIC Psycho­ logical Health Research and Applications Chair, Department of Psychi­ atry, College of Medicine, Deanship of Post Graduate Teaching, King Saud University. The funding body has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data nor in writing the manuscript. Author’s contributions All authors contribute equally to study design, data collection, data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Declaration of competing interest The authors declare that they have no competing interests. 90 M. Bahattab and A.N. AlHadi Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 19 (2021) 86–91 Acknowledgements Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Psychology Faculty Publications, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006 Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Hertenstein, E., Thiel, N., Lüking, M., Külz, A., Schramm, E., Baglioni, C., et al. (2014). Quality of life Improvements after acceptance and commitment therapy in Nonresponders to cognitive behavioral therapy for primary Insomnia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(6), 371–373. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365173 Kohtala, A., Lappalainen, R., Savonen, L., Timo, E., & Tolvanen, A. (2015). A foursession acceptance and commitment therapy based intervention for depressive symptoms delivered by master’s degree level psychology students: A preliminary study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43(3), 360–373. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/S1352465813000969 Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., & Walser, R. D. (2007). Learning ACT: An acceptance And commitment therapy skills-training manual for therapists. Oakland, Ca: Context Press. Molavi, P., Mikaeili, N., Rahimi, N., & Mehri, S. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy based on reducing anxiety and depression in students with social phobia. Journal of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, 14 (4),412-423. Rahmani, E., & Rahmani, M. (2015). Effectiveness of acceptance & commitment group therapy on anxiety reduction of students. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences, 5(11S), 661–665. Shaker, M., Rahimi, M., & Zare, M. (2016). The effectiveness of therapy based on acceptance and commitment social anxiety and general self-efficacy on divorced women under welfare organization in Yazd. Clinical and Experimental Psychology, 2 (137). https://doi.org/10.4172/2471-2701.1000137 Springer, J. M. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy [ACT]: Part of the “third wave” in the behavioral tradition. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34(3), 205–212. Tanhan, A. (2014). Spiritual strength: The use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) with Muslim clients (Unpublished master’s thesis). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester. Tanhan, A. (2019). Acceptance and commitment therapy with ecological systems theory: Addressing Muslim mental health issues and wellbeing. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 3(2), 197–219. Retrieved from http://journalppw.com/index.php /JPPW/article/view/172. Vakili, Y., & Gharraee, B. (2014). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in treating a case of obsessive compulsive disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 9(2), 115–117. Yavuz, K. F. (2016). ACT and Islam. In J. A. Nieuwsma, R. D. Walser, & S. C. Hayes (Eds.), ACT for clergy and pastoral counselors: Using acceptance and commitment therapy to bridge psychological and spiritual care (pp. 139–148). Oakland, CA, US: New Harbinger Publications. The Funding of this research was obtained by the SABIC Psycho­ logical Health Research and Applications Chair, Department of Psychi­ atry, College of Medicine, Deanship of Post Graduate Teaching, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. We would like to thank all the people who participated in the research for their patience and kindness. Some data in this manuscript had been submitted as a graduation requisite for the first author in master thesis in clinical psychology, Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont; United States. References Abbasi, M., Dargahi, S., Ghasemi Jobaneh, R., Dargahi, A., Mehrabi, A., & Aziz, K. (2015). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment based training on the maladaptive schemas of female students with bulimia nervosa. Arch Hygiene Science, 4(2), 86–93. Alosaimi, F. D., Alshehri, Y., Alfraih, I., Alghamdi, A., Aldahash, S., Alkhuzayem, H., et al. (2014). The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among visitors to faith healers in Saudi Arabia. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 30(5), 1077–1082. https://doi. org/10.12669/pjms.305.5434 Azadeh, S. M., Kazemi-Zahrani, H., & Besharat, M. A. (2016). Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on interpersonal problems and psychological flexibility in female high school students with social anxiety disorder. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(3), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n3p131 Bluett, E. J. (2017). Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder and moral injury. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. M. Boone, C.Myler. University Counseling and Psychological Services | Association for Contextual Behavioral Science. Retrieved January 8, 2018, from, https:// contextualscience.org/act_for_depression_and_anxiety_group_cornell_unive, n.d. Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychol- ogy. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. ISSN 1478-0887 Available from: http://eprints. uwe.ac.uk/11735. Dousti, P., Mohagheghi, H., & Jafari, D. (2015). The effect of acceptance and commitment therapy on the reduction of anxious thoughts in students. Environment Conservation Journal, 16(SE), 327–333. Dwairy, M. (2009). Culture analysis and metaphor psychotherapy with Arab-Muslim clients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/ jclp.20568 Folke, F., Parling, T., & Melin, L. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy for depression: A preliminary randomized clinical trial for unemployed on long- term sick leave. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(4), 583–594. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.01.002 91