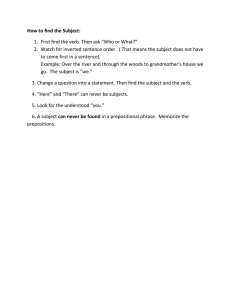

Grammar Basics: Subjects, Predicates, and Complements

advertisement