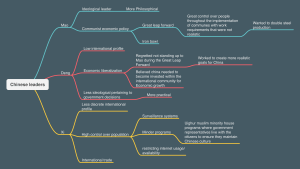

The Great Leap Forward: aims, economic consequences, famine. Great Leap Forward (1958-1961): Aims and features of the Great Leap Forward. May 1958: desire to accelerate China’s economic growth in order to achieve superpower status. ideological motivation for the precise nature of the plan would also promote the creation of a more socialist, classless society. Very high production quotas would be set for the increased production of food and the organisation into communes would facilitate greater direct control and requisitioning - massive reorganisation increase industrial production, particularly of steel, consequently there arose a proliferation of backyard furnaces for the production of steel in the countryside. Many peasants were forced off the land to supervise these furnaces and ‘donations’ of goods to be melted in these inefficient furnaces was also required of the local people. Factories also increased and were set similarly unrealistic production quotas. Great Leap Forward (1958-61): dire consequences for China and split with the Soviet Union ‘half of China may well have to die’ [November 1958] unrealistic quotas for food requisitioning, the massive quantities of food exported abroad (primarily to the USSR, North Korea and North Vietnam) and poor harvests during the ‘three bad years’ of 19591961, led to famine of catastrophic proportions in China, with an estimated 38 million deaths from starvation Terror was also unleashed on the peasantry as accusations of hoarding grain were common. poor central planning and ineffective management, failing, despite several superficially impressive grand projects, to reach its objectives. Indeed, Lynch has written that ‘the record of the Great Leap Forward is largely a study in failure’. division in politics, both domestically and internationally. Sino-Soviet split first became evident ideological fight with Khrushchev denouncing the latter’s policies in the USSR as ‘revisionist’, and placing ‘survival before Marxism-Leninism’. socialist aims of the Great Leap Forward were meant to indicate that China had taken no such revisionist path and thus deserved to be recognised as the foremost power in the Communist bloc. explicit overtures to other communist states in order to try to divert their loyalty towards China and away from the USSR. Khrushchev was outraged and withdrew many of the Soviet advisors from China, halting assistance on many as yet incomplete industrial projects, including, of course, the construction of the Chinese A-bomb. Mao’s objective of launching Maoism on the world in order for China to replace the USSR as the foremost socialist nation was now entirely apparent. The Great Leap Forward (1958-61): Political divisions within the Chinese Communist Party. division within the Chinese Communist Party whose legacy would be long-lasting and bloody. Cultural Revolution in 1966 to exact his terrible revenge on those within the Party who had dared to criticise his policies in the Great Leap. first of these rare voices was that of Marshal Peng Du-huai, Defence Minister and member of the Politburo. Peng, however, having failed to prompt any action from the European communist bloc against Mao’s continued exportation of food, and failing to attract any significant co-plotters to his side in China, he became the victim of Maoist terror. Mao accused Peng at a Party conference in Lushan of trying to form an ‘anti-party clique’ and he was denounced, arrested, his family became outcasts and Peng himself spent much of the next two decades in forced labour camps and solitary confinement in prison. He was replaced as Defence Minister by Lin Biao, entirely loyal to Mao, and who launched a purge of Peng’s sympathisers in the army. The purge was broadened throughout China, focusing on resisters of requisitioning. 1962 by no less than Mao’s Number 2 in the Communist Party, the President Liu Shao-chi. At the Conference of the Seven Thousand convened in 1962 to which the top officials from throughout China were invited, the problems resulting from the Great Leap Forward were high on the agenda. planned the Conference in such a way as to stifle any potential opposition to him President, Liu Shao-chi in delivering his speech, departed from the set text in order to criticise the Great Leap announcing that ‘there is no Great Leap Forward but a great deal of falling backward’. minimise damage to himself by seeking scapegoats for the failings of the Great Leap and producing a limited ‘self-criticism’. Mao was also essentially forced to abandon the high food levies and the Great Leap Forward effectively came to an end in 1962.