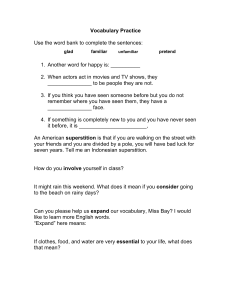

JOURNAL OF BELIEFS & VALUES https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2019.1570452 The Indian superstition scale: creating a measure to assess Indian superstitions Sieun An a a , Navya Kapoor a , Aanchal Setia a , Smriti Agiwal a and Ishika Ray b Ashoka University, Sonepat, India; bUniversity of Washington, Seattle, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Despite humans’ capacity for rational thought, they are not immune to superstitions. Superstitions are strongly tied to cultural practices, especially in India. Although 17% of the world’s population resides in India, Indian culture is understudied, and there have not been sufficient attempts to understand Indian superstitions in a scientific manner from a psychometric standpoint. By creating a proper superstition measurement for the Indian population, we can better understand how Indians think and behave. The goal of the present research is to create a superstition measure specific to Indian culture. The results reveal 18 items reflecting Indian superstitions that can be generalised across contemporary India. superstition; belief; well-being; culture Rational and superstitious practices are intertwined in our daily lives. Superstitions – no matter how trivial – are an integral part of most individuals’ lives even in the present day context (Sagone and De Caroli 2014). Superstitious beliefs have a significant influence on people’s choices, be it in their daily lives or while making important business or market economy decisions (Block and Kramer 2009; Kramer and Block 2007; Lepori 2009). There have been several attempts to define the concept of superstition. Levitt (1952) postulated that the following six characteristics need to be taken into consideration while defining a superstition: a superstition is: (1) fundamentally irrational; (2) popularly accepted (i.e. it should be a widely held belief); (3) usually influences the behaviour of the holder; (4) may be a belief in supernatural phenomena in the conventional sense; (5) has no sound evidence of personal experience to support it; and (6) may have arisen spontaneously and spread without ever having had the sanction of authority. Typically, psychological researchers refer to superstition as a phenomenon exerting an imagined influence on an action or an outcome when no real causal relationship is apparent, or indeed present (e.g. Carlson, Mowen, and Fang 2009; Matute, Yarritu, and Vadillo 2011). A majority of theories accounting for both superstitious cognition and behaviour have been examined from a psychological perspective (Campbell 1996; Shermer 1997; Vyse 2013). However, most of these theories account for the factors which lead to superstitious behaviour, but do not directly measure superstition as a psychological construct in and of itself. As a result, psychologists have produced CONTACT Sieun An sieun.an@ashoka.edu.in Department of Psychology, Ashoka University, India © 2019 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group 2 S. AN ET AL. research explaining the social cognitive aspects of superstitious thinking and belief (e.g. Jahoda 1970; Lindeman and Aarnio 2007; Rice 2003) as well as its behavioural manifestations (e.g. Damisch, Stoberock, and Mussweiler 2010; Morse and Skinner 1957; Skinner, 1948) without measuring the extent to which superstitions affect an individual’s functioning. In order to accomplish such a goal, it is necessary to have tools that allow psychologists to assess superstitious beliefs. In the past, several scales that measure superstition have been created (e.g. Carlson, Mowen, and Fang 2009; Fluke, Webster, and Saucier 2014). However, superstitious beliefs and practices differ across cultures and populations (Carlson, Mowen, and Fang 2009); therefore, culture-specific superstition scales would be more sound tools to measure superstitious beliefs. The goal of the present research is to develop and administer a scale to measure superstitious beliefs across India that can predict the magnitude of an individual’s superstitious ideology. Who is superstitious? There has been much speculation and subsequent research as to the kind of people who ‘fall prey’ to superstitions. Research shows that Americans tend to associate the propensity towards superstitious thought and behaviour with individuals who are backward and uneducated (Frazer 1922; Jueneman 2001; Vyse 2013). Nevertheless, it is clear that although the definition of superstitious belief and behaviour is largely agreed upon, the actual classification of beliefs and behaviours as ‘superstitious’ can vary even within a culture. Lesser (1931) posited that ‘the same belief or behaviour can be superstitious to one person, non-superstitious to another; non-superstitious to one person at one time, superstitious to the same person at a different time; . . . non-superstitious to all men at one time, superstitious to all men at a different time’ (620). The need for a superstition scale for India Superstitions are a fundamental part of India’s culture and are deeply rooted in people’s beliefs even today (Jayapalan 2005). Superstitious beliefs are greatly associated with illiteracy, which has a rate of about 36% in India (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India 2011b). However, in contrast to the general opinion about the holders of superstitions, 60–70% of India’s literate working population, including scientists, hold superstitious beliefs (“Institute for the Study” 2008; Kashyap 2012). Therefore, the behaviour and practices of people of India cannot be understood completely without studying superstitions. A reliable measure for superstitions will provide a base for studying superstitions in relation to cognitive and behavioural phenomena. Superstitious beliefs and behaviours have been extensively studied and various scales have been created to measure superstitious ideologies of people (Darke and Freedman 1997; Fluke, Webster, and Saucier 2014; Huang and Teng 2009; Huque and Chowdhury 2007; Žeželj et al. 2009). However, these scales are not considered to be as externally valid as previously thought, due to findings that show that specific superstitions differ across cultures (Carlson, Mowen, and Fang 2009). This discovery also highlights a gap in psychological literature on superstition, since the scales used to assess superstitious JOURNAL OF BELIEFS & VALUES 3 beliefs and practices are not necessarily valid for all cultures. This is especially true for Indian culture as it is vastly different from Western cultures. Many of the superstitious beliefs that are prevalent in Western cultures do not pertain to India. For example, the superstition that Friday 13th is an unlucky day is widespread in America to an extent that people deliberately avoid travelling and working on that day, which leads to an estimated loss of $800 to $900 million each Friday 13th (Roach 2004). On the other hand, this superstition is irrelevant in India. Likewise, the Indian superstition that one should hang lemons and chilies on the door to keep the evil eye away does not apply in the Western context. While the wearing of white clothes by a married woman in India is considered highly inauspicious and is frowned upon, women in Western cultures typically wear white on their wedding day. India’s demographic is famously heterogeneous, with an estimated 1.3 billion citizens, 22 scheduled languages, and at least seven different religions (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India 2011a). This diversity cultivates unique ideas and values, which could be a probable origin of superstitions that are widely varied from superstitious beliefs found in other cultures. In any case, no uniform scale has been constructed in the past for the Indian population. Components of the scale The present 18-item questionnaire was created with Nixon’s (1925) principle aim in mind: by creating a concise list of short but representative statements, we can measure a general overview of the factors which greatly affect superstitious beliefs in Indians. Most items on this scale were constructed in accordance with the revised paranormal belief scale (Tobacyk 2004). It aims to measure both positive and negative magical beliefs that are prevalent in Indian society, deriving common religious and folk superstitions from Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and indigenous tribal faiths. Some items on our Indian questionnaire are adapted from the Bangladesh questionnaire (Huque and Chowdhury 2007), since Bangladesh was part of the Indian subcontinent until the partition of Bengal in 1947. As a result, modern day Bangladesh and India continue to share certain key cultural similarities, folklore and superstitions among them. The present scale refrains from more geographically or culturally specific items such as ‘Taking good food and having pastime on the first day of a new year (e.g. the 1st Baishak of the Bengali Year) will make your days good throughout the year’, which are present and justified in Huque and Chowdhury’s (2007) Bangladeshi superstitions scale. Instead, this scale includes items that may be generalised across the breadth of India, namely positive and negative outcome superstitions without a specific geographic or cultural detail – (‘Adding one rupee to a gift sum is auspicious, i.e. sums like 21 or 101 rupees or 501 rupees are considered more auspicious than say 20 or 100’, ‘It is an ominous start if anyone sneezes while getting out of the home’). In an attempt to make the scale more generalisable across India, most items in the questionnaire are derived from Hindu folklore and culture (for instance, ‘A person born under the influence of Mars is called a manglik or is described as having a Mangal Dosha. People avoid marrying such a person, especially if the person is a woman. Marriage with such a person is believed to cause marital discord and divorce, sometimes death’, ‘The wearing of white clothes by a married woman is considered inauspicious’). Inclusion 4 S. AN ET AL. of these religion-specific items is justified by the 80% Hindu majority in India (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India 2011a). In contrast, other Indian religions such as Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism are distinct from Hinduism and condemn superstitious beliefs in their tenets (“Religion: Buddhism” 2018). Consequently, any superstitious beliefs held by participants following these religions would be rooted in Hinduism, as well as more esoteric local customs. The items adapted from Huque and Chowdhury (2007) also account for superstitious beliefs that are prevalent among non-Hindu majorities; since Bangladesh is a Muslim-majority country, the adapted items account for superstitious beliefs potentially held by Muslim participants. The current project aimed to construct a measure of superstition for Indian population, which could aid our understanding of the way 17% of the world’s population thinks and behaves. Method Participants Participants were 219 undergraduates from a mid-sized university in India (100 men and 119 women) with a mean age of 18.68 years (SD = 1.26). All were Indian nationals from various regions in India (North = 46%, South = 26%, East = 15%, West = 10%, and Central = 3%). Religious breakdown was 62% Hindu, 22% non-religious, and 16% of other (Christian, Islam, Sikhism, etc.) religions. All participation was voluntary, and was compensated with a small gift. Materials and procedure The superstition questionnaire items were generated by several research assistants who are native to Indian culture from different regions of India. We finalised them into 34 items; participants rated them on a 0 = not at all to 6 = very much scale in response to the question, ‘Please read the following statements and rate how relevant they are to Indian Cultural Superstitions for you.’ We also recorded basic demographic information (age, sex, nationality, hometown, religion, etc.). Results The 34 superstition items were factor analysed using a Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation and Kaiser Normalisation. A total of 18 items were selected for the scale, which was created for Indian specific superstitions. See Table 1. The analysis yielded two factors explaining a total of 56.18% of the variance. Thirteen items loaded onto the first factor. The 13 items loaded above 0.5 for component 1, but not on other components. See Table 2. This factor was labelled ‘influence on well-being’. The first factor solution explained 49.77% of the variance. Internal consistency of the 13 items was examined using a reliability test. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96, demonstrating strong internal consistency. Five items loaded on the second factor. The five items loaded above 0.5 for component 2, but not in other components. See Table 3. This factor was labelled ‘symbolistic JOURNAL OF BELIEFS & VALUES 5 Table 1. List of Chosen 18 Indian Superstitious Items. Item 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Description It is ominous to see a black cat on the way to your destination or out of home. If anyone praises a healthy and good-looking child, he/she gets sick for having an evil eye. Flicking of the left eye is a sign of getting sick soon. If the foetus moves in mother’s womb, it will be a boy, else it will be a girl. The entrance of butterfly into the room is a good sign. It is a symbol of good luck for the father, if the first born is a daughter. One should not open the doors at night upon hearing a single call from someone outside the home. The birth of handicapped children is the consequence of parent’s sin. If a pregnant woman cuts anything during the lunar eclipse or a solar eclipse, she will deliver a deformed child. To keep the evil away from home, one should hang lemons and chilies on the door. It is bad luck if the temple lamp blows out in the middle of the prayer. It is bad luck to pluck flowers and leaves after dawn. Adding one rupee to a gift sum is auspicious, i.e. sums like 21 or 101 rupees or 501 rupees are considered more auspicious than say 20 or 100. Mothers put kohl (eyeliner) on their babies’ face to ward off evil eye, by making it imperfect. A person born under the influence of Mars is called a manglik or having a Mangal Dosha. People avoid marrying such a person, especially if the person is a woman. Marriage with such a person is believed to cause marital discord and divorce, even sometimes death. However, it is believed that if two mangliks marry, the effects of both cancel out. Peepul trees are believed to be the abode of ghosts, and they are avoided at night. Continuous hiccups are considered a sign of someone close badly remembering you. The wearing of white clothes by a married woman is considered inauspicious. The scale score is the mean of the 18 items. Anchors are defined as 0 being less superstitious, and 6 being highly superstitious. Table 2. Item factor loadings for Factor 1 based on a principal components analysis with varimax rotation and Kaiser normalisation. Item 1 2 3 8 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Factor 1 0.686 0.697 0.656 0.586 0.784 0.742 0.562 0.784 0.786 0.750 0.679 0.779 0.712 Factor 2 0.211 0.203 0.426 0.192 0.156 0.137 0.164 0.198 0.315 0.201 0.259 Communalities 0.70 0.69 0.67 0.69 0.84 0.69 0.47 0.73 0.77 0.81 0.68 0.70 0.69 Table 3. Item factor loadings for Factor 2 based on a principal components analysis with varimax rotation and Kaiser normalisation. Item 4 5 6 7 9 Factor 1 0.267 0.229 0.139 0.375 Factor 2 0.562 0.582 0.623 0.752 0.575 Communalities 0.64 0.55 0.49 0.64 0.65 6 S. AN ET AL. prophecy’. The second factor solution explained 6.41% of the variance. Internal consistency for the five items was examined using a reliability test. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78, demonstrating adequate internal consistency. Lastly, Factor 1 and Factor 2 were strongly correlated, r = .61, n = 219, p < .001. Due to the relatively high correlation between the two factors, we performed a discriminant validity test as described in Campbell and Fiske (1959). The result of this test was .70, which is under the criterion value of .85 for meeting discriminant validity. This lends support to the claim that Factors 1 and 2 measure separate, but related constructs. Next, to provide support for the predictive power of the scale with respect to religion, we performed a 2 Religion (Hindu vs. Non-Hindu) × 2 Factor (1 vs. 2) two way ANOVA. The results showed that there was a main effect of Religion, F(218, 1) = 13.01, p < .001, η2partial = .06, such that Hindus (M = 1.88, se = .12) were more superstitious compared to Non-Hindus (M = 1.20, se = .15). Also, there was a main effect of Factor, F(218, 1) = 114.75, p < .001, η2partial = .35, such that Factor 1 items (M = 2.10, se = .13) were rated higher compared to Factor 2 items (M = .99, se = .08). These main effects were qualified by a Religion by Factor interaction, F(218, 1) = 10.44, p = .001, η2partial = .05. For Factor 1, Hindus (M = 2.59, se = .16) reported stronger superstitions compared to non-Hindus (M = 1.58, se = .20), and for Factor 2, Hindus (M = 1.17, se = .10) reported slightly stronger superstitions compared to non-Hindus (M = 0.82, se = .13) as well. See Figure 1. We also performed predictive validity tests on sex and hometown separately; however, there were no significant effects for these variables. Discussion The purpose of the current research was to develop a superstition scale that could measure superstitious beliefs across contemporary India. The results showed that 18 out Hindu Non-Hindu Superstition Rating Scores 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 1 2 Factor Figure 1. Interaction of Religion by Factor. Hindu N = 136; Non-Hindu N = 83 JOURNAL OF BELIEFS & VALUES 7 of the 34 items are relevant to Indians who participated in the study. There are 13 relevant items in Factor 1 and five relevant items in Factor 2. The results support that the superstition scale constructed in this study is highly reliable. Superstitions include beliefs that are not consistent with scientific findings. They are often seen as thoughts that science has been unable to explain through its laws (Himawan 2014). This is supported by the theme of Factor 1 being influence on well-being, and the theme of Factor 2 being symbolic prophecy. Furthermore, superstitions are culturally specific (Carlson, Mowen, and Fang 2009), and as demonstrated by the findings of the present paper, developing a measure of superstitions is important in order to understand the factors that affect patterns and variances of behaviour within a specific culture. India is a country with a population of 1.3 billion (Statista 2018), so understanding its cultural components is crucial to understanding humans on earth. To our knowledge, this is the first Indian superstition scale (ISS) that has been developed, and is a significant contribution towards mapping Indian culture and psychology. Limitations and future directions There are a few caveats to consider. The project was conducted with college students who are mostly from urban backgrounds, so the population was not educationally diverse. However, since the subjects came from all over India (south, north, west, east and central) and had a variety of religious backgrounds, the results can be generalised to all parts of contemporary India. In the future, this experiment can be replicated with rural populations in India with different socio-economic backgrounds, ages, education levels, etc. Also, this measurement itself can reflect why and how Indians think and behave the way they do, and has much potential for future projects. Going forward, this measurement can be used in various projects relating to India including – but not limited to – projects exploring the link between superstitions and religion. Previous research showed positive correlation between people’s religious beliefs and the magnitude of an individual’s superstitious beliefs (Buhrmann and Zaugg 1983; Rudski 2003). Further, our findings also establish a proportional link between these two variables. The stronger superstitious beliefs among Hindu participants in the present study can be attributed to the greater incidence of superstitious practices within Hinduism. Conversely, the weaker superstition reported by non-Hindu participants is reflective of the tenets of their own faiths (including atheism), since the other surveyed religions forbid superstitious beliefs and behaviour. While superstition has been found to be negatively correlated with intelligence and openness to experience (Shenhav, Rand, and Greene 2012; Wagner 1928), Vyse (2013) argues that even Harvard students, whom one might consider intelligent, engage in superstitious behaviour. However, no causal link has been established between intelligence and superstitious beliefs. Further, while both sexes are superstitious, women are slightly more superstitious than men (Vyse 2013; Zapf 1945). While these studies were conducted in Western countries, similar studies can be performed with Indian populations to explore intelligence and gender in relation to superstitious beliefs and practices. With a reliable measure for superstitions, the number of people who believe in superstitions to a given extent can be calculated, which can be further used to understand the 8 S. AN ET AL. impact of superstitions on cognition and behaviour. For instance, good-luck associated superstitious behaviour has been shown to lead to better performance in tasks such as golfing, memory games, etc. (Damisch, Stoberock, and Mussweiler 2010). Since the present questionnaire uses a Likert scale as opposed to a binary scale, the degree of belief in superstitions can also be assessed. The causal link demonstrated by Damisch et al. could be further affirmed by studying the relationship between the level of performance and the degree of belief in general superstitions. Alternatively, a study that explores the effect of activation of ill-omen on superstitious and non-superstitious people’s performance could be conducted as well. In conclusion, this project significantly enhances our understanding of the prevalence of superstitions in Indian culture, which previously had not been well understood or heavily investigated in a scientific manner. The results from this study can be extended to understand the impact of superstitions on the cognition and behaviour of individuals. Further research can aim to discover various other variables in relation to superstition such as the role played by religion in forming superstitious beliefs as well as to explore the cause and effect relationship between the two variables, if there is one. This will help us to understand how blind faith in superstitions can be questioned so that humans can attempt to be logical and rational. Superstitions continue to be deeply ingrained in the minds of many, so a reliable superstition measure can add to the understanding of psychology. Disclosure statement No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Notes on contributors Dr. Sieun An is an assistant professor of Psychology at Ashoka University. Ms. Navya Kapoor is an undergrad student majoring in Psychology at Ashoka University. Ms. Aanchal Setia is an undergrad student majoring in Psychology at Ashoka University. Ms. Smriti Agiwal is an undergrad student majoring in Economics at Ashoka University. Ms. Ishika Ray is a graduate student majoring in Psychology at the University of Washington at Seattle. ORCID Sieun An http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7760-924X http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9718-195X Navya Kapoor http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4742-3572 Aanchal Setia http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0112-1341 Smriti Agiwal http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1491-8176 Ishika Ray References Block, L., and T. Kramer. 2009. “The Effect of Superstitious Beliefs on Performance Expectations.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 37: 161–169. doi:10.1007/s11747-008-0116-y. JOURNAL OF BELIEFS & VALUES 9 Buhrmann, H. G., and M. K. Zaugg. 1983. “Religion and Superstition in the Sport of Basketball.” Journal of Sport Behavior 6: 146. Campbell, C. 1996. “Half-Belief and the Paradox of Ritual Instrumental Activism: A Theory of Modern Superstition.” British Journal of Sociology 47: 151–166. doi:10.2307/591121. Campbell, D. T., and D. W. Fiske. 1959. “Convergent and Discriminant Validation by the Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix.” Psychological Bulletin 56: 81–105. Carlson, B. D., J. C. Mowen, and X. Fang. 2009. “Trait Superstition and Consumer Behavior: ReConceptualization, Measurement, and Initial Investigations.” Psychology & Marketing 26: 689–713. doi:10.1002/mar.v26:8. Damisch, L., B. Stoberock, and T. Mussweiler. 2010. “Keep Your Fingers Crossed! How Superstition Improves Performance.” Psychological Science 21: 1014–1020. doi:10.1177/0956797610372631. Darke, P. R., and J. L. Freedman. 1997. “The Belief in Good Luck Scale.” Journal of Research in Personality 31: 486–511. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1997.2197. Fluke, S. M., R. J. Webster, and D. A. Saucier. 2014. “Methodological and Theoretical Improvements in the Study of Superstitious Beliefs and Behavior.” British Journal of Psychology 105: 102–126. doi:10.1111/bjop.12008. Frazer, J. G. 1922. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, 401–402. Vol. 1. New York: Macmillan. Himawan, K. K. 2014. “Magical Thinking in Jakarta: What Makes You Believe What You Believe.” Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy 5: 3–9. doi:10.1080/ 21507686.2013.872158. Huang, L. S., and C. I. Teng. 2009. “Development of a Chinese Superstitious Belief Scale.” Psychological Reports 104: 807–819. doi:10.2466/PR0.104.3.807-819. Huque, M. M., and A. H. Chowdhury. 2007. “A Scale to Measure Superstition.” Journal of Social Science 3: 18–23. Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture. 2008. Worldviews and Opinions of Scientists: India 2007-2008 Summary Report. https://www.scribd.com/document/17138974/ Worldviews-and-Opinions-of-Scientists-India-2007-2008-Summary-Report Jahoda, G. 1970. The Psychology of Superstition. Harmondsworth: Penguin. Jayapalan, N. 2005. Problems of Indian Education. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. Jueneman, F. B. 2001. “The Making of a Myth.” Research & Development 43: 9–10. Kashyap, G. K. 2012. “Superstition@Workplace.” People Matters. https://www.peoplematters.in/ article/watercooler/superstition-workplace-2345?utm_source=peoplematters&utm_medium= interstitial&utm_campaign=learnings-of-the-day Kramer, T., and L. Block. 2007. “Conscious and Nonconscious Components of Superstitious Beliefs in Judgment and Decision Making.” Journal of Consumer Research 34: 783–793. doi:10.1086/523288. Lepori, G. M. 2009. Dark Omens in the Sky: Do Superstitious Beliefs Affect Investment Decisions? Working paper, Copenhagen Business School. Lesser, A. 1931. “Superstition.” The Journal of Philosophy 28: 617–628. doi:10.2307/2015685. Levitt, E. E. 1952. “Superstitions: Twenty-Five Years Ago and Today.” The American Journal of Psychology 65: 443–449. Lindeman, M., and K. Aarnio. 2007. “Superstitious, Magical, and Paranormal Beliefs: An Integrative Model.” Journal of Research in Personality 41: 731–744. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.06.009. Matute, H., I. Yarritu, and M. A. Vadillo. 2011. “Illusions of Causality at the Heart of Pseudoscience.” British Journal of Psychology 102: 392–405. doi:10.1348/000712610X532210. Morse, W., and B. F. Skinner. 1957. “A Second Type of Superstition in the Pigeon.” The American Journal of Psychology 70: 308–311. Nixon, H. K. 1925. “Popular Answers to Some Psychological Questions.” The American Journal of Psychology 36: 418–423. doi:10.2307/1414166. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011a. “Census of India: Data Item Collected in Census.” http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/data_item_collected_ in_census.aspx 10 S. AN ET AL. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011b. “Census of India: Literacy and Level of Education.” http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/literacy_and_level_of_ education.aspx Religion: Buddhism. 2018. “British Broadcasting Corporation.” http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/ religions/buddhism/ Rice, T. W. 2003. “Believe It or Not: Religious and Other Paranormal Beliefs in the United States.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 95–106. doi:10.1111/jssr.2003.42.issue-1. Roach, J. 2004. “Friday the 13th Phobia Rooted in Ancient History.” National Geographic News. Accessed 28 July 2008. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/02/0212_040212_fri day13.html Rudski, J. 2003. “What Does a “Superstitious” Person Believe? Impressions of Participants.” The Journal of General Psychology 130: 431–445. doi:10.1080/00221300309601168. Sagone, E., and M. E. De Caroli. 2014. “Locus of Control and Beliefs about Superstition and Luck in Adolescents: What’s Their Relationship?” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 140: 318–323. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.427. Shenhav, A., D. G. Rand, and J. D. Greene. 2012. “Divine Intuition: Cognitive Style Influences Belief in God.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 141: 423. doi:10.1037/a0025391. Shermer, M. 1997. “Why People Believe Weird Thinks.” In Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time. New York: WF Freeman and Company. Skinner, B. F. 1948. “‘Superstition’ in the Pigeon.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 38: 168. doi:10.1037/h0055873. Statista. 2018. “The Statistics Portal.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/263766/totalpopulation-of-india/ Tobacyk, J. J. 2004. “A Revised Paranormal Belief Scale.” International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 23: 11. doi:10.24972/ijts.2004.23.1.94. Vyse, S. A. 2013. Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition-Updated Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. Wagner, M. E. 1928. “Superstitions and Their Social and Psychological Correlatives among College Students.” The Journal of Educational Sociology 2: 26–36. doi:10.2307/2961760. Zapf, R. M. 1945. “Relationship between Belief in Superstitions and Other Factors.” The Journal of Educational Research 38: 561–579. doi:10.1080/00220671.1946.10881378. Žeželj, I., M. Pavlović, M. Vladisavljević, and B. Radivojević. 2009. “Construction and Behavioral Validation of Superstition Scale.” Psihologija 42: 141–158. doi:10.2298/PSI0902141Z.