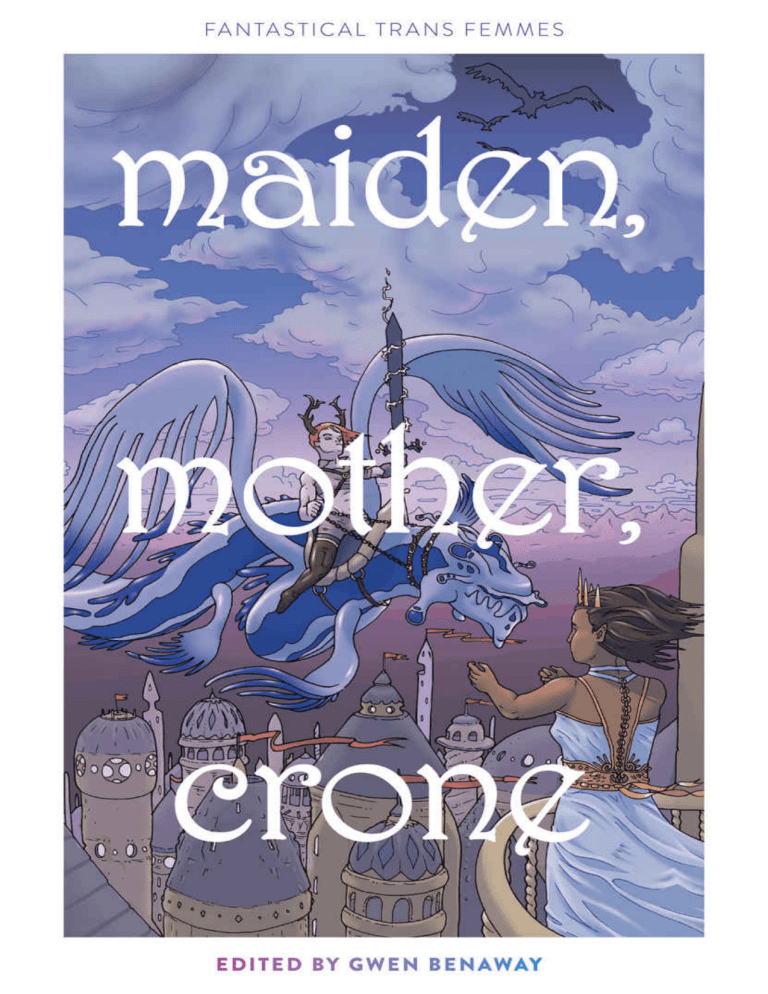

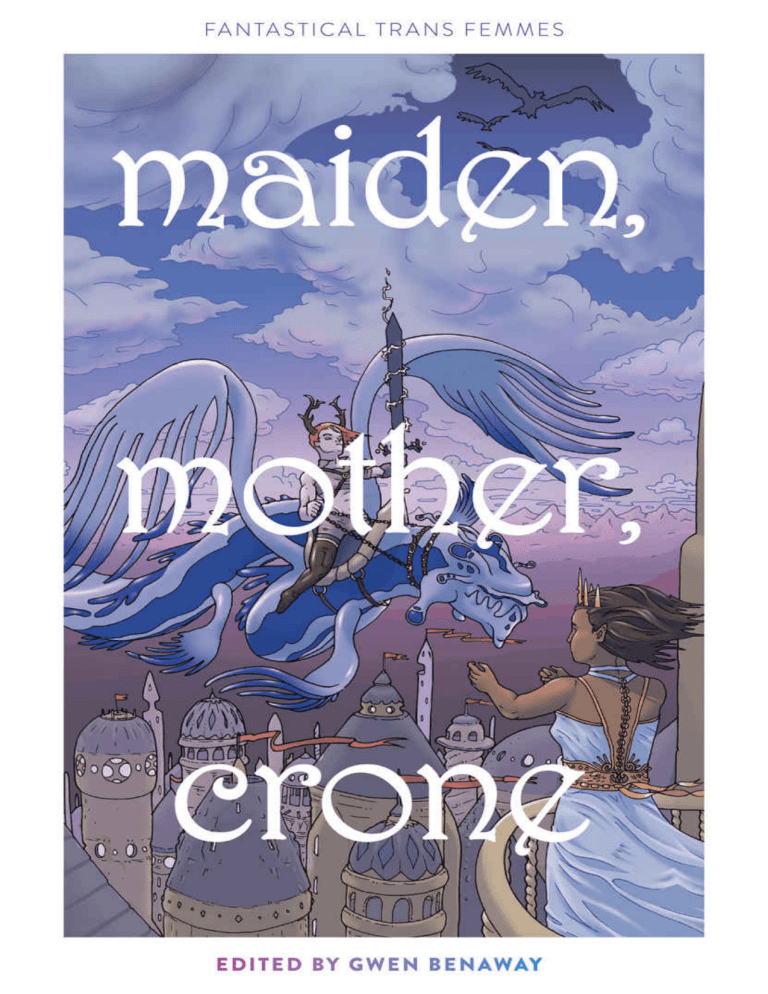

Maiden, Mother, Crone

FANTASTICAL TRANS FEMMES

Edited by Gwen Benaway

Copyright 2019 Bedside Press

Cover art A by Annie Mok

Cover design A by Scott A. Ford

Cover art B by Alex Morris

Interior and cover design B by Relish New Brand Experience

Edited by Gwen Benaway

with additional edits by Emily Stewart & Tia Vasiliou

All stories, memoirs, and poems are copyright of their respective creators as indicated herein, and are

reproduced here with permission.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in any sort of

retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher—or, in the case of photocopying

or other reproduction, a license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency—is an infringement

of copyright law.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Title: Maiden, mother, crone : fantastical trans femmes / Gwen Benaway.

Other titles: Fantastical trans femmes

Names: Benaway, Gwen, 1987- editor.

Description: Short stories.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190078669 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190078774 | ISBN

9781988715216 (softcover) | ISBN 9781988715285 (PDF)

Subjects: CSH: Fantasy fiction, Canadian (English) | CSH: Short stories, Canadian (English) | LCSH:

Fantasy fiction, American. | LCSH: Short stories, American. | CSH: Canadian fiction—21st—

century | LCSH: Transgender women—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PN6071.F25 M35 2019 | DDC 813.087660806—dc23

ISBN 978-1-988715-30-8 (MOBI) | ISBN: 978-1-988715-31-5 (EPUB)

Bedside Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada and the Government

of Manitoba through financial support received from Canada Council for the Arts and the Manitoba

Arts Council for this project.

BEDSIDE PRESS

bedsidepress.com

Table of Contents

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

Gwen Benaway

MOUNTAIN GOD

Gwen Benaway

FOREST’S EDGE

Audrey Vest

THE VIXEN, WITH DEATH PURSUING

Izzy Wasserstein

POTIONS AND PRACTICES

gwynception

FREEING THE BITCH

Ellen Mellor

THE KNIGHTING

Alexa Fae McDaniel

UNDOING VAMPIRISM

Lilah Sturges

I SHALL REMAIN

Kai Cheng Thom

DREAMBORN

Kylie Ariel Bemis

FAILURE

Casey Plett

PERISHER

Crystal Frasier

BIOS

Editor’s Introduction

GWEN BENAWAY

F

antasy was always my first literary love. I spent all of my childhood

reading paperbacks by Mercedes Lackey, Tanya Huff, Melanie Rawn,

and Robin Hobb. Stories of magic and romance were the one safe place in

my life, an imaginary home that I carried with me wherever I went. My

earliest heroines were the beautiful and powerful women that I found in

between the pages of fantasy books. I used to imagine that I could step

through a shimmering portal and appear in a fantasy land in a different body

and gender where adventure, spells, and love waited for me.

I never found that magical other world, but I did transition to become the

woman I always knew I was. Revisiting my favourite fantasy books after

my transition made me realize the many parallels between the lives of trans

femmes and fantasy heroines. While we don’t always slay dragons, there is

a magic and wonder about our lives. We often face enormous challenges

and terrible villains, but we continue to battle onwards. Yet despite these

obvious connections, our lives as trans folks are almost never reflected in

the fantasy books and stories.

I wanted Maiden Mother Crone to be a space for other trans women and

trans feminine folk to write fantastical short stories where trans folks were

the main characters. Between the pages of this anthology, there is a wide

range of fantasy genres and characters represented. All of the classic

fantasy tropes are here, but they are often reimagined in new and

compelling ways. Many stories are about love, community, and kinship.

Some stories look into a bleak future world while others imagine entirely

new worlds. Every story offers a different window into the possibilities of

trans femmes, imagining us as fearless warriors, revolutionary fighters, and

mercenary mages.

While reading the stories in this anthology, I was reminded of why I fell

in love with fantasy. Fantasy gives us the freedom to imagine different

stories for ourselves. The reality of our lives as trans women is never far

from the surface of our fantastical stories, but within their magical bounds,

we have the agency and capacity to change worlds. I hope that our readers

find the same wonder and joy within this anthology that I found in editing

it.

Miikwec,

Gwen

Mountain God

GWEN BENAWAY

T

he air was cool around her. She and Rais were in the foothills of the

mountains, a transitory landscape where the scrub brush of the plains

gave way to tall evergreen trees and dense under foliage. As they rode

closer, the temperature had steadily dropped from a blistering dry heat into

a cool and moist fog. Aoyas breathed in and felt her chest muscles constrict

underneath her leather armour. The air was getting thinner.

Rais rode beside her in silence. They had camped at the edge of the

foothills last night, sleeping underneath one heavy woolen blanket beside a

small creek. She knew Rais hadn’t slept well, haunted by his dreams and

kicking her in his sleep. The last few moons had been rough on both of

them. They had taken a small contract with a local Lord in Hakien out of

financial desperation. Mercenary jobs were plenty in the Occupied lands as

the local Lords and Ladies frequently warred with each other for regional

domination, but some jobs were better than others. The Hakien contract was

messy, as the Lord was fighting off a small farmer rebellion led by his halfsister, and it ended in a brutal midnight raid that made Aoyas’s stomach turn

to think of.

As a mage, she had been behind the main battle lines, casting light spells

to guide the Lord’s forces and occasionally casting fire on the rebellion’s

camps. Rais was mostly an axe fighter, but he was good on horseback and

knew his way around a heavy spear, so the Lord had insisted he participate

in the main charge. The rebellion had been on the verge of starving. The

Lord’s half-sister had been making gestures toward surrender in the days

before the raid. There’d been no reason for a slaughter, much less a

dishonourable attack on a sleeping camp.

Even from where she had been, Aoyas had heard the screams and seen

the Lord’s men chase down fleeing rebellion soldiers. It had been a vulgar

display of masculine pride and violence. The Lord had gleefully watched

the destruction of his half-sister’s forces but elected to stay safely back

while his army had murdered their way to a resolution. Aoyas hated him

and every noble like him with a fierce passion. When Rais had returned

from the raid, his armour soaked in blood and a hard, tight line etched in his

mouth, Aoyas had hated the Lord even more.

Rais didn’t talk about it and Aoyas didn’t ask. She just wrapped Rais in

soft arms every night, holding him through bad dreams and strange moods.

The trip into the mountains was a makeshift pilgrimage away from the

bloodshed of the past moons, a chance for them to reconnect and figure out

next steps. The Lord had been pleased with their service, giving a small

bonus which Aoyas had accepted with a barely hidden grimace. Killing

with her magic bothered her.

Magic was the most beautiful part of her life, a sweetness behind every

bad moment, and she hated despoiling it for petty noble cruelty. There was

no choice but to use her magic against others. If she’d stayed in the Imperial

Academy, she could have used her magic to cast high wards to guard cities,

light their streets, and purify their air. It had always been her dream to work

the highest magic in the Capital city. She loved the rituals and structures of

high magic, the obscure incarnations and the elaborate weaving of elements

together to produce perfect spells that lingered for decades. Her battle

magic, it’s small and violent applications of elemental force, always felt

rushed and flawed in comparison.

She was the first one in her family to attend the Academy. Growing up in

Lerani, the smallest Occupied land under the Empire’s control, meant

accepting a second-class life. Lerani was the last conquered region in the

Empire. The land had been seized in her great-grandmother’s generation,

but the last rebellion was only fifty years ago. In theory, Lerani citizens had

the same rights as any other member of the Empire, but in practice, her

homeland was barely administrated by the Empire. They sent the worst

governors to Lerani, underfunded all of its services, and drained its

resources to fuel the Empire’s more important regions.

Lerani hated the Empire with a passion that put the other Occupied lands

to shame. Her grandmother, a short woman with magic of her own, had

famously spat at Lerani’s governor and was publicly flogged for it. Aoyas

remembered how her grandmother wore her scars with pride, dramatically

wearing loose dresses that showed the raised marks along her back at every

public gathering. Lerani was not a land meant for Imperial overlords nor

were its people interested in the supposed benefits of being Imperial

citizens.

Even as a child, Aoyas had understood that her people had been

conquered and were living with invaders inside their own territories. She

still dreamt of Imperial high magic and living in the Capital city. Magic was

different in Lerani. It had no rituals nor any structure that Aoyas could feel.

Her grandmother had felt Aoyas’s magic blossom inside her when she was

barely six moons old and had tried to teach her traditional Lerani magecraft.

Aoyas didn’t understand it. She knew some Lerani spells, but she could

barely make them work even though she was considered a mage of some

skill in Imperial magics.

The Academy was supposed to solve all of Aoyas’s problems. It was

extremely rare for the Academy to accept Lerani students. There was a

quota set on how many mages from the Occupied lands could become

Imperial mages and once you left the Occupied lands, you were not allowed

back. The Empire may have been lazy, but it wasn’t stupid. Training its

conquered peoples in the magic that had conquered them was only

permissible if those trained never returned home. Aoyas had accepted that

reality, pushing through her interviews and scoring the highest in all of

Lerani’s students.

On the day that Aoyas left her family and homeland for the Academy, her

grandmother had turned away from her and called her a traitor to her

people. Perhaps she was right in the end, Aoyas thought as the sound of

Rais sneezing brought her back into the present moment. The Academy was

as bigoted as the Empire that it served. A Lerani mage might be accepted to

the Academy and excel, but they would be regulated to the secondary

magics and held back from true knowledge, never more than a servant to

the “true” Imperial citizens. The dream she had chased was an impossible

one, so she had left the Academy and sold her magic to survive.

Rais was an unexpected gift. They’d stumbled into each other at a tavern.

Both of them had been brand new to the mercenary life, trying to stay alive

for the first year of their contracts. The first year of any mercenary’s life

was the most lethal. If you lived through it, you were lucky. She and Rais

had been competing for the attention of another mercenary, a blond-haired

Imperial boy who smouldered with a quiet intensity. Somewhere between

flirting with him and downing cheap ale, Aoyas had realized that Rais was a

much more captivating match.

As a Marked woman, Aoyas knew her chances of attracting Rais’s

interest were low. The Empire allowed for citizens to change their born

genders and, if they could pay for it, buy the magics necessary to make their

genders visible in their bodies. Thankfully, Aoyas’s own magic was strong

enough to allow her to do it herself. She had started using the feminizing

magics just after hitting puberty, walking up to the Lerani Consulate and

requesting a gender change without her parent’s permission. Sheer force of

will had got her what she’d wanted and she had never looked back, writing

her new name in blue ink on the citizen registry in front of a bored Imperial

clerk.

Aoyas meant “winter star” in Lerani. There was some legend about the

winter star that her grandmother told the kids in her village, a long-winded

Lerani tale about the darkest night and the single silver star that graced the

highest point in the sky, but Aoyas just liked the sound of the word. As a

Marked woman, the Imperial term for those who changed their gender

identification and bodies through magic, Aoyas’s place in society was lower

than an Unmarked woman, but living as herself meant more to her than the

relative comfort of being Unmarked.

Rais didn’t care that Aoyas was a Marked woman. He was a child of the

Capital city, but Rais’s father was not an Imperial citizen. He came from

beyond the borders in a wooden sailing ship and disappeared back to his

homeland after Rais was born. Growing up with an Outworlder father, Rais

had learned to fight dirty to survive the casual hatred of the Empire. He was

fearless at heart, wearing his hair shorn to the scalp and refusing to conform

to the rules of Imperial life.

They fucked the night they met in an alleyway beside the tavern and

hadn’t stopped waking up together since. Their love was a soft whirl that

kept them alive. They had other lovers when the mood suited them, but

always ended tangled back up together. Aoyas didn’t trust anyone like she

trusted Rais. Their jobs constantly put them in danger and Rais’s dagger had

saved Aoyas’s life more times than she could count. In return, Aoyas

spelled Rais’s clothes to keep him warm and wove intricate protection

magics around her lover’s body.

A high pierced whistling ruptured through the silence of the foothills.

Rai’s horse started beside Aoyas and almost bolted from the sound. Aoyas

felt a sudden searing pain against her cheek and then saw drops of blood

fall onto her saddle. It happened so quickly that she missed the bandit’s

arrow as it swept past her and into the distance behind her. Rais was already

in motion, leaping off horseback into a low tumble with his twin axes in

hand.

Aoyas felt her magic flare around her, a tightening of pressure and air as

three men burst through the brush ahead of them. Their loose cloth tunics

and steel blades marked them as bandits as surely as the murderous glow in

their eyes. She couldn’t see the archer but Rais was already rushing toward

the men, fearless as always. Aoyas pulled her magic into a tight arc in her

hand, one luminous thread of Air and one smaller spark of Fire.

“Immolate,” she whispered under her breath, sending her magic coursing

toward the bandits. The sudden rush of yellow flames along their clothes

told her that her spell had reached them as Rais’s axes cut the first one

down.

More people to kill, she thought, and another beautiful morning ruined.

They reached the mountain village entrance by noon. The sun was burning

in a high arc overhead, but the shadow of the mountain peaks fell over the

land, trapping the wooden houses in morning mist and fog. Every house in

the village was painted in bright blues and greens. The village was the

terminus point on the trail from the Capital to the mountain range, a

meeting point of traders, travellers, and mountain folk. Just beyond the

village, there was a pass over the mountains that bridged two worlds, the

Occupied lands and the unconquered lands beyond.

The Empire wasn’t interested in the lands beyond the mountain village. It

had expanded westward as far as it wanted, signing treaties with the

mountain peoples under the threat of Imperial armies and then ignoring

them onwards. There was an Imperial Consulate in the village, but it was

just a simple thatched house with a single lowly Imperial clerk. There

wasn’t even an army outpost here. As far as the Empire was concerned, as

long as the village paid its taxes, it was on its own.

“Is your face okay?” Rais made brief eye contact with her when he spoke,

gesturing by pointing his lips toward her cheeks. The arrow had barely

broken skin, but the thin cut had bled for a while before drying shut.

“It’s fine. Not like I was winning any beauty contests before.” She

shrugged at him as their horses ambled through the village gates. “Do you

think it will scar?”

“Maybe? Keep it clean and let it air. You could get lucky.” Rais was

always like this—casual, unbothered, matter of fact. “When we get to the

inn, I can take a closer look at it. If you want.”

“If you don’t mind, I guess? I washed it quickly, but I hate to think where

that arrow had been before it found me. It’s not like those bandits were

worried about hygiene.” The bandits had been well equipped and more

organized than the usual highwaymen who preyed on the Imperial highway,

but infection from metal blades was always a risk.

“Okay. I’ll look at it, but after we eat? I’m sick of eating dry rations.

Reminds me of being in the army.”

“And we should probably report it to the Imperial clerk, just in case they

ever send a patrol out here and want to follow up.” She didn’t think anyone

cared about bandits in the mountains, but if enough travellers went missing,

maybe the Empire would send out a patrol. They cared about money and

keeping trade routes flowing even if they didn’t care about people.

Rais rolled his eyes at her. “If you like, m’lady.” His brief army service

had left him with a bitter distain for the Empire and all of its agents.

Aoyas had disliked his cynical practicality when they first got together,

wanting a partner who spent more time comforting her, but eventually she’d

come to appreciate it. His philosophy came from his life in the poor districts

of the Capital city, a world where no respecting Imperial citizen went. It

wasn’t that the poor districts lacked in beauty or softness, but everything

was measured against the reality of not having enough to spare. He didn’t

waste time with falseness or the Empire’s institutions.

As they followed the dirt road toward to the village’s inn, Rais pulled

ahead of her and rode in front. The villagers barely glanced in their

direction, used to strangers arriving off the road, but Rais had an annoying

protective streak. He wasn’t tall, but his wide shoulders and the obvious

confidence that he moved with marked him as a skilled fighter. People

didn’t often realize that Aoyas was a Marked woman, but there could be

trouble if they did. In theory, the Empire didn’t believe in any difference

between Unmarked and Marked women, but the reality of life for a Marked

woman was different.

Usually the only work that Marked women could find in the Empire was

as courtesans or entertainers. Aoyas was a rarity, an educated Marked

woman with the mage gift. She could have capitalized on that privilege

more, choosing to pass as an Unmarked woman and hiding in the

Academy’s mage towers, but she loved the freedom of the road. Her father

was Lenari, but her mother’s people had come from the Empire when

Lenari was first conquered, so Aoyas looked enough like an ordinary

Imperial citizen to deny her Lerani blood.

She had never denied being Lerani or a Marked woman, even when it had

made her life harder. Besides, an Unmarked Imperial woman would have

never been seen in the company of a man like Rais. He may have had an

Imperial mother, but his father was an Outworlder and he didn’t look

anything like what an Imperial citizen was supposed to. It wasn’t just that

she travelled with him. Anyone who paid attention to them could see they

were intimate partners as well—it was visible in the way that Rais

sometimes reached across the space between them to rub her back or tuck

her long hair behind her ears.

As she watched Rais ride in front of her, she wondered if she loved him

or just felt obligated to him. His presence made her life on the road

possible. There were bands of mercenary women, but they often didn’t let

Marked women join their ranks. She was a brilliant mage, skilled enough at

high battle magics, but she wasn’t much of a close-range fighter. Without

Rais’s axe, she would already be dead a hundred times over. Of course, on

his own, Rais could never command the same rates as he did with her. Axe

fighters were common enough, but Imperial trained battle mages, even

Marked Lerani ones, were rare. Maybe that’s all that love is, she thought,

mutual indebtedness.

The village inn was similar to the standard inns that populated all of the

Empire’s towns and cities. The main building was a large double-storey

wooden frame with a high turreted roof. There was a narrow stable behind

the main building with a small enclosed courtyard. With the mountains

rising up above the village and the cool air flowing around them, it was

almost idyllic. The only difference between the village inn and the usual

Imperial Inns was the small shrine to the Mountain God in the middle of the

courtyard. Technically, the Empire had no official religion and tolerated all

faiths, but it was rare to see such a visible expression of belief.

Rais rode through the inn’s courtyard toward the stable and dismounted

behind the hitching post. His horse, a spotted gelding with a gentle

disposition, stamped his feet impatiently while Rais tied the lead to the post.

They’d been sleeping rough since they passed through the last town almost

two weeks ago, grazing the horses on the wild grasses of the lowlands.

Aoyas guided her mare toward the hitching post behind Rais. He reached up

to help her down even though she was perfectly capable of dismounting on

her own.

“Graceful as ever.” He gave her a smirk before taking the lead from her

and tying her mare up. “Can you handle the innkeeper on your own? ’Cause

I need to pay a visit to the latrines.”

Now it was her turn to roll her eyes at him. “I’m not completely useless. I

think I can handle a village innkeeper without adult supervision.”

“Is that what you are? An adult? I always figured you for more of a

spoiled academic brat,” he quipped at her before turning away to walk

toward the communal latrines behind the inn. Aoyas patted her mare and

Rais’s gelding for a minute before heading inside to secure lodgings within,

amused by the momentary flush in her skin from Rais’s teasing.

Innkeepers were important people in villages. They often formed the

landed gentry, upper class citizens with connections across the Empire, and

knew all of the region’s gossip. The innkeeper in the village was an older

man with a heavy build that suggested he knew his way around swordcraft

in his youth. She made eye contact with him as she stepped through the

inn’s front door and walked toward the bar where he was nursing a large

cup of mead.

He appraised her as she walked toward him. Aoyas could never tell if

people knew that she was a Marked woman from her appearance, but

judging from the way his eyes hardened, it was obvious that he’d decided

that she was not the kind of woman he wanted in his inn. Wait till he sees

Rais, she thought, internally steeling herself for the inevitable display of

prejudice.

“Silari.” She greeted him in the high tongue of the Empire. It was a trick

she’d learned because only the educated and upper class spoke the high

tongue. It didn’t mean that the innkeeper would be friendly, but it told him

that she was not a common mercenary. “Looking to book lodgings, and care

for our horses for a couple of days, maybe longer.”

He nodded at her. “Silari, kinas.” He returned her greeting in the high

tongue, adding the feminine title for mage. “Shouldn’t be an issue. We’ve

been fairly quiet since the bandits got more active on the south road.”

Aoyas nodded at him as she pulled out her coin purse to negotiate the

price of their stay. “We ran into some of the bandits on our way in. I haven’t

heard that this area was dangerous for travellers, so it was an unexpected

welcome.”

The innkeeper grunted back at her. “It’s dangerous alright. Ever since the

civil war in Neruados, we’ve been plagued by bandits. Figure it’s

mercenaries and soldiers from the losing side of the war who got a taste for

blood and don’t want to go back to farming.”

“Hmm. Yeah, we saw some of that war up close and it wasn’t pretty.”

Aoyas laid down three silver coins on the bar. It was more than she would

usually pay for a room in a tiny inn, but something told her to not barter

with this man.

His explanation for the bandits made sense to her. Often mercenaries on

the losing side didn’t get paid and needed to recover their costs somehow.

Given the Empire’s considerable disinterest in this part of the Empire,

bandit work was unlikely to result in executions or the Imperial Army

bearing down on you. A small village like this wouldn’t be able to raise the

funds to hire mercenaries to drive away the bandits or get a local Lord to

bother defending them.

“Odd choice for you to travel north instead of going back toward to the

centre. Can’t be much work for you. Magecraft isn’t called for much here.”

The innkeeper pocketed her coins in a single smooth movement and started

pouring her a drink from the communal ale barrel.

Aoyas breathed an internal sigh of relief. If he’d turned them away, it

would mean more rough camping in the cold mountain night. “We wanted

to take a break from fighting for a while. Thought the mountains would be

peaceful.”

“Before the war, they were. Now? It’s safe inside the village bounds, but

the pass and the roads leading in and out are unsafe for travellers. They

leave the village folk alone and our traders get around okay, but travellers or

anyone who looks to have some coin is in danger.” The innkeeper placed a

mug of ale in front of her as he spoke and then reached back for another

mug. “Same for your friend?”

The raised tone in his voice on the word “friend” was a question. She

could ignore it, but figured honesty was her best policy. “Sure. My partner.

He’s an axe fighter.”

The innkeeper shrugged at her and began filling the second cup. “Good

choice. A lady mage on her own or with another lady is asking for trouble.”

Aoyas wanted to tell him that “lady” mercenaries were just as capable as

male ones, but it was not worth it to start fights with the locals. Just then,

she heard the inn door open as Rais walked in. The innkeeper looked up at

him and then back at her. He raised his eyebrows at her.

“An Outworlder, eh?” The innkeeper set the second mug down beside

hers and walked off to talk to the other patrons, letting his disapproval

linger in the air. Aoyas wanted to snap back at him, to call him on his

bullshit, but making a scene wouldn’t help them out. It would mostly be for

her pride anyway. Rais didn’t need her to fight his battles for him,

something she had learned early in their relationship.

Rais stood beside her at the bar. He smelled of their horses and the sweat

of travel. “How did it go? Everything worked out?”

Aoyas gestured to the second mug. “All good. Some mild judgment, but

nothing I couldn’t handle. We’re all paid up.”

Rais lifted the mug to his lips and tried a little of the ale. He grimaced at

the taste but kept drinking. “We are a striking couple.”

“I hate it when people are assholes to you. Still, he did explain the bandit

problem. Mercenaries from the war trying to recoup some costs before

winter comes.”

“Great. We travel to the far reaches of the Empire and run into the same

folks that we were just killing.” He took a few more sips of the ale before

absentmindedly rubbing her back. “Do you think they could recognize us?”

Aoyas considered his question for a moment before answering, quietly

soaking in the warmth of his touch. “It’s possible. Mages tend to stand out.”

“So do Outworlders.” He wasn’t wrong. The innkeeper’s reaction was the

standard response, not a rarity.

“He said they have been leaving the village alone, so we’re probably safe

here. And I’m tired of sleeping on the ground so …” She let her words trail

off, hoping Rais would just agree with her.

He sighed deeply before replying. “I guess. Sometimes I wonder if I

should have fallen for an ordinary girl who ran a bookstore or something.

I’d sleep easier.”

Aoyas tried to control the sudden panic that flared in her body at his

words. He was probably joking, but there was always a small part of her

that wondered when he would get bored of her and find a new lover. An

Unmarked woman who could give him everything he wanted: babies,

security, an easy and comfortable life. Girls like her might be fun for a night

of experimentation, but not a lot of men stuck around for the next day. Rais

had stuck around for the past eight years, but sooner or later, she knew her

luck would run out. She wasn’t getting any younger.

He sensed her anxiety through his hand on her back, feeling the sudden

tightening of the muscles along her spine. “Hey I’m sorry.” He leaned in

closer to her as he spoke. “I was just joking. I didn’t mean it like that.”

“No, I know. It’s fine.” She smiled at him, trying to be reassuring. “Let’s

just see if we can find bath water and maybe spend the rest of the day

hiding in whatever room he gives us?”

“Yeah. I’d like that.” Rais dropped his hand down from her back toward

to her ass, gently squeezing it through her leather tights.

“Really? That’s your idea of romance? After eight years?” Aoyas rolled

her eyes at him and discreetly pushed his hand away from her body. “I’m

not some naïve farm girl or tavern wench that you can seduce with a sleazy

comment and a grope.”

He laughed softly at her and shrugged. “What can I say? I’m a simple

guy. If you wanted poetry, you should have stayed in the Academy.”

“No, I prefer this. And you. Weirdly, even if we get murdered in our sleep

by vengeful bandits in the middle of nowhere, I wouldn’t trade the past

eight years for anything.”

“Shit, lady.” Rais took a swill of the ale and swallowed before smirking at

her. “You got it bad.”

The innkeeper returning to show them to their room saved Aoyas from

having to come up with a witty reply. Sending Rais to grab what they

needed from the horses, she followed the innkeeper up the narrow flight of

stairs at the back of the inn. The room he placed them in was small, but

mercifully clean. It overlooked the small courtyard with its tiny statue of the

Mountain God. She could see Rais below in the stable, rummaging through

their travel packs and whistling to himself.

As she stood looking out at the courtyard and the mountains beyond, an

old prayer of her grandmother’s suddenly came to mind. It had been years

since she’d spoken in her ancestral tongue, but the words came easy to her

lips. She murmured it to the scene before her, saying the last words out loud

in the common Imperial tongue.

“Carry us home, mother, through all our journeys.”

The screams woke them before dawn. At first, the screams were high

pitched and distant, but they rapidly got more frantic and closer. Rais was

awake before she was, rolling from her side and grabbing his axe before

rushing to guard the door to their room. Aoyas flung herself up and ran to

the window overlooking the courtyard. An ugly red glow beneath her told

her that the village was on fire. From her vantage point, she could see a

swarm of shadowy men on horses riding closer to the inn.

“Fuck. The bandits recognized us.” Aoyas shouted to Rais. “We need to

get out of here now!”

“What about the villagers?” Rais turned from the door to face her. “You

just want to leave them to die?”

“No, of course not, but what are we going to do? We’re two people

against at least twenty of them!” She looked out the window at the men

rushing toward the inn. Their torches outlined the burning village houses,

sending wild shadows through the night. A few of the villagers had tried to

fight them and been slaughtered, but most were running from their houses

toward the mountain pass to hide.

“I’m not leaving innocent people to die for our crimes. I swear to all the

gods, Aoyas, I’m not living with it on my conscience.” Rais’s face was

locked into a steely determination but his eyes were soft. “I can’t just run

away.”

“I’m not leaving you here, Rais. You’re all I have.” She could hear the

hysteria in her voice, but she couldn’t help it. If they fought, they would die.

“Please. We have to run.”

“No.” He shook his head at her. “I love you, but there’s a difference

between killing people because it’s your job and letting people die in the

night because you’re a coward.”

“We’re mercenaries, Rais! An Outworlder, a Marked woman. Not

heroes.” The time for running was almost gone. If they ran to their horses

now, they might still make it to the relative dark and safety of the

mountains.

“No, m’lady. I’m sorry. I’m going out there. You can run or come with

me, but I’m not leaving these folks to die.” He opened the door to their

room and disappeared down the inn stairs, leaving her by the window.

It wasn’t a hard decision to make. She followed after him, reaching deep

into herself for the threads of magic that spoke of fire and death. She could

kill three men in close combat with her magic, but twenty was impossible.

This was the end. She would never see Lerani again or her grandmother.

Never wake again with Rais’s arm tucked around her waist. No more

magic, no wind through the pine trees, nothing but the infinite silence of

death.

As they rushed out of the inn’s door and into the main village road, they

passed the innkeeper and his family huddled against the inn’s back wall.

The innkeeper had an old broadsword in his hands, and his wife was

holding a hunting bow. Rais nodded at him as they swept past and he

nodded back. They would die tonight just as Rais and Aoyas would, but

they wouldn’t die without a fight.

The bandits were only a few houses away when she and Rais stepped into

the road. Rais stood in front of her, his axe balanced in his expert hands. He

was bare chested in the night air. They didn’t have time to put on their

armour, much less plan any strategy. This was going to be a fight run

entirely on instinct and training. Aoyas was wearing an old tattered tunic

that barely covered her thighs, but she had had the foresight to grab her

small ritual knife before rushing after Rais.

The bandits slowed down when they saw her and Rais in the road. They

pulled into a small group behind a man on a black horse with a heavy scar

running down his face. He laughed at her and Rais’s defiant poses.

“Here they are. The bastard Lord’s mage and his perverted lover.” The

scarred man’s voice was rough but well trained. He must have been a minor

noble before the war.

Aoyas wasn’t surprised that he called her by her birth gender, but it still

pissed her off. “Fuck you,” she said to the surrounding bandits, summoning

a small thread of flame into her raised hand. Rais stayed silent, focusing all

of his attention on the axe balanced in his hands and the enemies in front of

them.

The scarred man just shrugged at her before gesturing to the bandits

beside him. “Kill them.”

Then, before she had a chance to think or to look at Rais, it began. The

bandits rushed toward them in a torrent of sound and blades. There wasn’t

enough time to marshal her magical resources, just to react. She cast threads

of Air around Rais and herself in a loose circle before sending the spark of

Fire in her hand rushing along the narrow currents that she had spun. The

night air suddenly blazed in a sweltering rush of heat and light as her magic

took shape.

Her small Fire Storm kept the bandits back for a moment. Rais seized the

opportunity to go on the offense, rushing the nearest bandits and sweeping

them down with perfect arcs of his axe. Axe fighters didn’t have the grace

of swordsmen or spear fighters, but they did have tremendous killing force.

He crushed the windpipe of one bandit on a backswing before sending the

axe head deep into the stomach of another one.

It wouldn’t be enough. There were too many of them. The other bandits

were circling around behind them. They would rush Aoyas, killing her

before her magics could touch them, and then take Rais down like a pack of

wolves. She let the Fire Storm fade out as she readied another thread of

magic. This magic wasn’t Imperial nor Elemental. It was Lerani, rooted in

her Spirit and tied to something more powerful than even the land around

them.

As the next wave of bandits stepped over their fallen friends and ran

toward them, Aoyas pressed the tip of her knife deep into the veins of her

right wrist. A sharp pain washed over her as blood poured from her exposed

arteries. The thread of Spirit magic inside her flickered as her resolve

weakened, but then she heard Rais cry out. One of the bandits had scored a

deep cut on his right arm and he was bleeding. It would all be over soon.

Not tonight, she thought, I won’t let him die for me. She pressed the

dagger deeper and called the thread of Spirit fully into being. It roared

around her, drawing its power from her blood spilling onto the ground. The

air shimmered before her eyes for a moment and then the Spirit thread tore

out of her toward the bandits. It became a forked bolt of white lightning,

blasting into their skin and jumping between them.

Rais leapt back from the fray as soon as her lightning struck out. He ran

toward her, but she was already falling. Spirit magic was stronger than

Elemental. When the Empire had invaded her homeland, they’d discovered

just how powerful it was when their high wards failed and lightning fell on

their armies. But like all great powers, it had a terrible price paid in blood.

Her life for a spell felt like a fair trade when it meant that Rais would

live. She wondered what he would do without her as she felt her head slam

into the ground. Just before the infinite dark took her, she saw the remaining

bandits turn back and flee from the village. Their leader, the scarred man,

lay dead beside his horse in a pool of blood and scorched flesh.

The last thing she heard was Rais’s voice saying her name and then, from

some distant place she barely remembered, the sound of her grandmother’s

laugh echoing around her like a soft summer rain.

Light came back slowly. She tried to stay hidden in the dark as long as she

could, chasing the remnants of her grandmother’s presence, but the light

kept growing around her. Soon she could feel her body again, the roughness

of the bedding against her skin and the coarseness of the straw mattress.

Voices came next. She heard people talking in the distance and could feel

their heaviness of their spirits. Finally, the dark abandoned her completely

and Aoyas had no choice but to wake up.

She opened her eyes. Sunlight streamed from the small window in their

inn room. She was alone. The room was stuffy and smelled of sickness. She

tried to rise up in bed, but it hurt too much. Looking down, she could see a

large white linen bandage wrapped around her wrist. It was blood stained

but looked fresh. Someone was taking care of her.

“Rais?” Her voice cracked as she spoke, momentarily dropping down into

a deep pitch that she hadn’t used since childhood. “Is someone there?”

He might be dead. I could have survived but maybe they killed him. Fear

raced through her body, sweeping away whatever comfort she felt at finding

herself still alive. Tears rushed to the corners of her eyes, but she stifled the

panicked sob that swelled in her throat. Before she could think of what to

do next, she heard steps outside her door. She reached for her magic but

found nothing. It was gone, completely dried up from her last spell.

“Aoyas?” Rais opened the door gingerly, almost as if he didn’t believe

that she had really called out for him. “Are you awake?”

“Hey.” Her voice cracked again. She coughed, trying to clear the dryness

out of her throat. Rais stepped into their room and came to sit beside her on

the bed.

“Hey.” His voice was gentle as he reached out and brushed a strand of her

hair behind her ears. “You’re alive, I guess.”

“I think so.” She looked into his eyes, the same brown eyes that caught

her attention so many years ago. “And so are you.”

“Yeah.” Rais shrugged as he took her hand into his. “We’re both alive.”

“What about the bandits?”

“Either dead or run off. The villagers think we’re heroes. They want us to

stay for the season in case the bandits return, but they can’t pay us.” He

squeezed her hand softly before smiling at her. “I know it doesn’t make

good business sense, but would you be okay if we said yes to that?”

“You want to stay in an isolated mountain village with me for no pay?”

Aoyas raised her left eyebrow at him. “Did the bandits hit your head a lot or

something?”

Rais laughed before replying, “No. It just sounds nice.”

Aoyas stayed quiet for a moment, savouring the familiar warmth of his

hand in hers. She noticed that the breeze from the open window smelled of

wild roses and mountains. “You must really love me, huh?”

Rais squeezed her hand again, much tighter than the first time. He cleared

his throat and wiped his eyes with his sleeve before answering her.

“Yeah. I really do.”

Forest’s Edge

AUDREY VEST

I

t is a small village, in a valley at the base of a range of jagged mountains

at the edge of a dark forest far far far away in the north. Cold houses

built on cold earth beneath a thin grey sky. Wolves that howl in the

darkness. A wind that whispers ceaselessly in numb ears. It talks of old

things in dead tongues—buried lords, whose rotting corpses lie forgotten in

damp tombs; mounds of ash gone to flower; and castles ripped apart by

time, their bones ground to dust and blown away.

The villagers say the woods there are a gateway to Fairy; they say that to

walk beneath the forest’s laden boughs is to embrace death (or worse); they

say that at night if you peer between the wide trunks you might catch a

glimpse of the strange lights of the fey kin’s midnight banquets and hear the

distant music of their laughter, and that if you do not run then and douse

your head in cold water and burn sage and lavender and breathe the smoke

deep into your lungs, that you shall fall under their spell and be drawn back

to them and eat their food and spend forevermore in a daze at their grand

tables.

Dark falls early in this country, and from the little windows of the village

houses seeps the glow of oil lamps and candles and hearth fires over which

hang pots of fragrant soups made rich by the blood of that month’s

slaughtered cow.

One building smoulders hotter than the rest, and inside it a woman with

dark hair pounds a length of metal until its glow has faded all to naught.

She picks it up with tongs and nestles it among the coals of the furnace.

Sweat runs down her back. When the metal is bright again, she takes it and

hammers it here and bends it there, and when it’s finished, she dips it in a

vat of oil and wipes her brow with a soft rag while the metal hisses in its

bath. The woman sighs then, strong as a bellows. Her name is Denya. She

has spent her life here, thirty years of long winters and pale springs that

never bloom to summer but instead die unripe and wither beneath early

snow.

There comes a whimpering from the corner of the forge, a frail sound like

a dog too sick or tired or old to bark. Denya ladles broth from a pot hung by

the furnace into a wooden bowl which she takes to the corner, to her

daughter, Eliya, who lies curled in a nest of blankets atop an old straw

mattress.

Denya sits by her daughter’s side and brushes a lock of hair from her pale

cheek. Eliya’s skin is cold, despite the heat of the forge. She shivers at her

mother’s touch and Denya draws her hand back.

“My darling,” she says, “my dearest,” and her daughter’s eyes flutter

open, her irises as pale and grey as the late sky.

“Will you drink some now?” Denya asks and Eliya nods weakly.

Denya lifts her daughter’s head and brings spoonfuls of thin broth to her

lips, which the girl drinks slowly, as though the labour of swallowing is

almost more than she can bare. When the small bowl has been emptied,

Eliya’s eyes close again and Denya lays her back against her pillow and

pulls the blankets close around her once more.

It has been three weeks like this. Three weeks of Eliya shivering in the

forge while her mother sweats, of Denya watching her daughter grow thin

and weak, eating nothing and drinking only broth and murmuring fitfully in

her sleep at strange dreams whose contents Denya can only guess at. Denya

is afraid. The village hangs now at the end of autumn—any day now the

first snows will begin in earnest, and the air will come alive with the biting

malice of deep frost, and the sun will shine less and less through the haze as

the black jaws of winter close around them. Denya fears that she will watch

her daughter wither to nothing. That she will be left alone to bury her

behind the forge in the frozen earth beside her wife’s empty grave.

Such is the truth of life here, the hardness of it. Death is a fox lurking in

the garden, waiting for the weak or wounded, for the old, the young, the

tired or sick. Most die in ordinary ways and are buried in the little cemetery

by the old church where the villagers all gather on Thursdays to pray and

make offerings to the spirits of their dead.

Some few, though, die unseen. They vanish from their homes in the night,

and in the morning some trace of them is found by the forest’s edge—a

slipper, a scarf, a tuft of cloth caught on a bramble. They are the dead who

must be forgotten, for they are cursed. They have no headstones in the

churchyard, no offerings and prayers. To speak of them is sinful. To

remember them, dangerous. Better to forget them outright, lest you yourself

fall prey to their folly and wander where no human ought.

Denya smooths her daughter’s hair and frets. She looks at the empty

ground beside her, where Bren should be kneeling with her. When she

closes her eyes, Denya can almost see her wife’s face turned toward their

daughter, her mouth drawn in a frown, her brow knit with fear. Bren would

catch her staring and turn, and their eyes would meet and grow cloudy, and

they would force wan smiles they didn’t feel and clasp their hands together

and squeeze tightly.

Eliya moans faintly. Denya stands. She unties her apron and pulls her

jacket on and wraps Eliya’s blankets around her and takes her up into her

arms. Eliya is small for a girl of seven, and made feather-light from her

wasting. She stirs, and Denya whispers softly to soothe her, and she carries

her daughter from the forge out into the cold evening. They walk through

the village, past Falstom’s beer house, the sound of laughter rich in the air.

At the far edge of the village Denya takes a path along the base of a wide

hill, and they come eventually to Maro’s cottage.

It is an old, round building of grey stones. The door is rough against

Denya’s knuckles when she knocks. Maro opens the door and peers out at

them from beneath her wrinkles, and she frowns and draws them in and

latches the door behind her.

“Lay her there,” Maro says and Denya settles her daughter into Maro’s

bed.

The cottage is a single room whose walls are lined with shelves full of

jars and bottles and wicker baskets. Dried herbs and flowers hang in neat

bunches from the rafters, and the air is almost as hot as the forge. Denya

shrugs off her jacket and holds it nervously before her.

“She still isn’t better,” Denya says.

Maro harrumphs and shuffles to the hearth, where she pours two mugs of

pungent tea from a kettle.

“Warmth and soup, I told you,” Maro says and hands a mug to Denya.

“Nothing else for it but that.”

Denya puts her mug down on the table. “There must be something.”

Maro shakes her head and takes a long sip of tea.

“She’s skin and bone,” Denya pleads. “She can barely move, she sleeps

all day and talks in her sleep, and even in the forge she still shivers!”

A pot over the hearth begins to bubble over, and Maro shuffles over to

stir it and move it to the edge of the fire.

“Nothing I can do for her,” she says.

Denya says, “Please,” and takes a step toward the old woman.

Maro sighs and runs a hand through her short, wild hair, her back still

turned to Denya.

“You can work magic,” Denya begs. “How is there nothing?”

“Not magic!” Maro snaps. “I brew potions, that’s all. I fix flesh. Always

something to be done for flesh. Her sickness is in her spirit.”

There are tears in Denya’s eyes now, and they spill free and run down her

cheeks and drip onto the worn floorboards beneath her. Maro watches and

twists her thin hands together, and she looks away from Denya when the

woman begins to sob.

“What can I do?” Denya asks between her ragged breaths. “How do I

save her?”

Maro refills her mug and stares into it. “Broth.”

Denya makes an anguished sound and sinks to the floor.

Maro sits in a chair at her table. She says “Broth,” softly, and then louder,

“fey broth.”

Denya’s breath catches. She straightens.

“From the forest?”

Maro nods, her eyes fixed intently upon a beetle slowly ambling along

the edge of her table. “Only that will warm her. She has been in the woods,

I think, and has caught a chill there. I am sorry.”

Denya stands then, and looks to Maro’s window. Outside it is full dark,

the sky black and moonless.

“Take these,” Maro says and offers Denya a lamp and an iron dagger.

Denya takes both and dons her jacket, and she kisses Eliya on her

forehead. Maro comes over to them and cuts a lock of Eliya’s hair, which

she fastens to a length of cord that she ties around Denya’s neck.

“To remind you,” Maro says.

Denya wipes the tears from her eyes. She takes a last look at her daughter

and then she steps out into the night. Her jacket is heavy, but as she walks

east toward the forest the cold begins to worm its way inside her. She has

forgotten her scarf, and her gloves, and the air is heavy with the weight of

coming snow.

At the wood’s edge she stops. The trees are dark and thick and gnarled.

She has been here before, once as a child on a dare with her friends, and

then again three years ago when she found Bren’s necklace hanging from a

low branch the morning after she vanished. There had been a bird higher up

in the tree, crying out it’s lilting, tuneless song. She stood by the forest’s

edge and stared into its gloom, her mind a wheel spinning madly, every

muscle in her tensed and aching. She might have screamed, then. Might

have clutched the necklace tight and rushed in after her wife, if the

neighbors who’d come to help her search hadn’t laid their hands upon her

shoulders and pulled her away. As they half-dragged, half-carried her back

to the village, the bird followed, and every morning for three months Denya

woke to the sound of it singing outside her window. Her sobs were never

loud enough to drown it from her ears.

Eliya had been too young then to understand what had happened. She had

not wept for her mother, not like Denya had. Only later did Bren’s absence

become real to her and then Eliya grew quiet and took to writing Bren’s

name in the dirt when she practised her letters.

Denya’s breath comes in white puffs before her. She grips the knife tight

in her shivering hand and walks forward to the edge of the trees and past it,

and the stillness of the forest wraps around her like a quilt of lead.

The lamplight is pale and weak. She treads carefully over roots and fallen

branches. In deeper, deeper, every step a transgression. The air grows

warmer. There is a smell of old rot; musty leaves and dead wood gnawed by

worms and old moss hang like tattered banners from high boughs. She

walks and looks and strains her ears, but all she can hear are her own

footsteps, and there are no lights in the distance to guide her way.

Now she comes to an oddity, a place where the trees give way to a little

clearing, though the canopy is still thick above so that the place has the

feeling of a large room. The ground within is flat, hard earth, and it is warm

here, and the lantern seems almost to glow brighter when Denya steps

inside. The air smells sweeter. There is a sort of bed made of clean moss

near the edge of the clearing, next to a tree stump upon which sits a golden

cup and a glass pitcher of water with rose petals. The scene is wrong

somehow, though. Too large. The cup is as big as her head, she can see that

now, and the pitcher larger than her chest, and the bed is long enough again

by half for even the tallest men of her village, and there are footprints in the

dirt, long and bare, with four toes.

Denya hurries from the clearing. She stumbles once or twice, glances

back and sees nothing, though she cannot shake the feeling that there are

eyes watching her from the darkness just beyond her light.

More trees, more than can be counted, old and nameless and wild. And

now there is a light ahead, a glow that draws her like a moth, and Denya

hurries forward and staggers out into a glen of grass and stone. There is a

stream, and flowers, and the colours of it all are brighter than she has ever

seen. Behind her the canopy is alight with the fiery glow of sunset, and she

can feel the heat of it against her skin.

It begins to rain warm, sweet water. Denya looks up. There is blue above

her, dusky and soft as periwinkle. She tastes the drops with her tongue, and

she spreads her arms wide and laughs.

There is a path from the glen, wide and straight and lined with silver

lanterns whose flames are warm and inviting. Denya starts down the path.

Her steps are eager; before her there is a blueish glow, and behind her the

sun has set, and there are stars above her, and there is music in the air

pulling her forward, a lilting song whose notes excite her even as they raise

the hairs upon her neck. She comes eventually to a place where the trees

grow thinner, and there are lights among the branches and in the air around

them, and the ground is soft with moss and creeping thyme, and there are

long, low tables laden with platters and bowls of food and pitchers of drink,

and the air is warm as summer and fresh as morning dew.

And the people—the people! Tall and slender, with silver hair and sharp,

pretty features and clothes that look spun from spider silk, so fine and

shimmering and strange are they. Some sit at the tables on cushions and talk

and laugh high, thin laughs, while others dance in circles with each other as

the music rushes on from some unseen place.

A woman comes before Denya and smiles with a flash of white teeth. Her

hair is short and looks soft as down, and she wears silver piercings in her

nose and ears and lips the like of which Denya has never seen.

“Welcome, Beauty,” the woman sings in a gossamer voice.

Her eyes fall to the dagger Denya still clutches in her right hand, and the

fey woman’s eyes narrow and darken, and she says, “You will not need that

here, Beauty. There are no wolves in our country to bite your pretty flesh.”

Denya slips the blade into her belt and the woman smiles again.

“You must be weary,” she says and takes Denya by the hand. “Come, sit a

while and revive yourself.”

The woman’s hand is soft against Denya’s calloused skin. It is cold, also.

Denya shivers.

She is led to a table and made to sit upon a crimson pillow, and a glass of

rosewater is poured for her, and there is a plate before her of fresh bread

and sweet butter and ripe berries and cream. Denya looks at the food while

the short-haired woman sits beside her and smiles. An act of

encouragement. A granting of permission to indulge. Denya spreads butter

onto a piece of bread, slowly, as though she were in a stupor. Something

pricks at her, a thought, a memory. Broth. She has come for broth, and there

is a reason for it she cannot quite recall.

“Do you have any soup?” Denya asks. Her voice is rough and weak, as

though she has not spoken aloud in days.

The short-haired woman smiles. “You’ve a craving, Beauty?”

She claps her hands and a human boy brings her a bowl of soup. The

broth looks thick and nourishing, and it is full of bright, tender vegetables.

Denya takes up her spoon and holds it. She does not dip it to the bowl.

“You may eat, Beauty,” the short-haired woman says. “It is good and

hearty, just what you need to sate your hunger.”

Denya puts the spoon down.

She says, “I am—” and falters.

The woman’s features have grown bland now, and vacant. She has lost

interest, Denya thinks dimly, and feels a pang of guilt, of embarrassment,

and yet at once she is also relieved.

“Eat when you wish, then,” the woman says and stands and is gone so

suddenly it makes Denya’s head spin.

There are other fey at the table, but they don’t seem to notice her, or else

they don’t care. Denya looks at them, and there is something cruel now

about their pale faces, a sense of patient hunger she had not noticed before.

One face near the far end of the table flashes brighter than the rest—a blond

woman with rosy skin. She is familiar, somehow, and Denya frowns and

grips the edge of the table.

And she remembers—her village, her childhood, her friends, and Bren

chief among them. And then a muddling as she ages, a wrongness. She is

fourteen and her father takes her to Maro’s cottage and the old woman gives

her a bottle of white powder and another of blue and tells her they will

change her and ease the disharmony between her body and her mind. She

takes a spoonful of each every morning and grows and blossoms and is

right again in her skin, and her name is Denya, now, after her grandmother,

and …

Bren. Her eyes, blue and close. Kind as her kisses, her touch. They dress

in white, and smiles, and there is music for them. And then blood—too

much blood on the sheets, and Denya’s heart beating so fast and fearful

while Maro holds her hands between Bren’s legs to catch the baby. Eliya,

they name her. Eliya, their angel, their light. And Bren leaves them, leaves

her daughter and her wife and goes into the forest like some lost child, and

then tears, and time, and the ache of Denya’s arms as she strikes hot iron

until it is a twisted lump and she throws it against the wall and weeps on the

ground by her anvil. And then … and then something. Then the reason for

all this, why she came here.

Eliya. Her cold cheek.

Denya’s hands are white and shaking. She lets go of the table. Bren is

staring at her with a look of dim confusion, and Denya goes to her and

kneels beside her wife and draws her close. Their arms wrap around each

other, as urgent and awkward as when they were seventeen and first

admitting their love. Holding her had felt like hunger, then. Now it is like

home, like safety, all warmth and comfort and rightness.

“Bren,” Denya says as her tears fall hot upon her wife’s shoulder. She

says it like a prayer. As though a name itself could be salvation.

She pulls away smiling, but Bren’s eyes are still unfocused.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you,” Bren says, but her tone is uncertain. “We

get so few visitors here.”

Denya’s breath catches in her throat. On the table in front of Bren is a

half-eaten slice of bread, a cup of water with faint marks from her lips upon

the glass.

“No!” Denya cries and the dread inside of her is like ice.

Bren looks confused, almost frightened. In a panic Denya leans forward

to kiss her. Bren’s lips are soft and yielding, familiar, warm. Denya reaches

up, cups her wife’s face in her hands while Bren leans toward her into the

kiss. One of Bren’s hands comes gently to the nape of Denya’s neck,

stroking her skin.

But it is wrong, somehow; Bren’s movements feel eager, but shy,

hesitant. All at once it is like kissing a stranger, and Denya pulls away

crying.

“What’s wrong?” Bren asks. “Did I upset you?”

The cold inside of Denya spreads further, deeper. It is in her bones, her

heart, its barbed tendrils clawing at her mind. Bren’s face becomes blurry as

Denya’s eyes well up with tears.

“It’s me,” she pleads. “Don’t you remember?”

“I’m sorry,” Bren says. Her voice is wounded, confused, and she shrinks

back dejectedly.

Denya sobs. She leans toward her wife again, but this time she takes the

strand of Eliya’s hair from the cord around her neck and presses it into

Bren’s cold hand.

“Your daughter, remember?” Denya says through her tears. “She’s sick,

she needs you—I need you!”

Bren stares at the lock of Eliya’s golden hair, the same shade as her own,

which has grown long in the years since she left them.

She says, “Daughter?” and Denya’s heart swells, but then Bren looks up

and says, “I think you must be confused. Here, won’t you drink something

to calm yourself? Some wine to ease your sorrow?”

Denya cries out, an anguished, whimpering sound, and she pulls away.

She stands, her body shaking and weak.

“What’s wrong?” Bren asks. “Won’t you stay with me?”

Her words tear at Denya. She longs to say yes, to stay, to wrap her arms

tight around her wife and never leave. But already she can feel her mind

growing dull again as the magic of this place gnaws at her memories, her

purpose. If she stays, she will be lost and Eliya will die. But if she leaves

now, if she turns away …

Bren’s features quiver on the edge of heartbreak. Even like this, some

part of her must remember, must cry out for her beloved. A few tears spill

free from her storm-grey eyes and run down her soft, perfect cheeks.

“I’m sorry,” Denya sobs. “I love you, Bren.”

Denya turns her back on her wife. She picks up the soup and walks with

bleary eyes back down the path from which she’d come, and as the fairy

music fades behind her she hears a new harmony caught up in its melody,

the distant, familiar sound of a woman crying.

The glen is dark when Denya reaches it, and the stream has frozen and

the air is cold, and as she hurries forward the first flakes of snow begin to

fall about her.

The trees close around her again. She has lost her lantern somewhere—

perhaps she dropped it before, or at the table—and so she stumbles through

the dark and almost drops the bowl when she trips over a root and falls hard

against a wide trunk. Denya leans against the tree for a moment, panting.

She can hardly see. Her face has grown cold, and her head throbs, but her

hands are warmed by the bowl of soup, and she steadies herself and

straightens.

There comes a sound from someplace near, an infant’s wail.

Denya steps cautiously toward the crying. There is a baby on the ground

in the middle of the clearing, small and naked, and just past it an old man

sits on a stump with his arms folded.

“She’s hungry,” the man says. “She’s cold.”

Denya kneels before the baby. “Where did it come from?”

“Mother left her,” the old man says with a tilt of his head. He has long

grey hair and dark eyes and a thick beard of long whiskers that clump

together like dried twigs.

“Poor thing,” he says pleasantly. “She’s so hungry.”

Denya swallows. The infant’s wailing claws at her, and she feels an

aching in her breasts. When Eliya was born and Bren almost died, Maro

gave Denya a potion that made her own breasts swell with milk, and though

she had not carried her, Denya nursed her child all that first month while

Bren recovered from the birth.

The ground is hard against Denya’s knees. The pain in her head has

grown almost blinding from the cold and the sound of the baby’s cries.

The man says, “She needs broth. Hot broth, to warm her.” Denya’s heart

skips and she looks up just as the man lunges for her neck with taloned

hands.

She staggers back. The infant is gone and in its place there is only a large,

smooth stone. The man stands—too tall, too thin—and lunges for her again.

Denya draws her dagger and slashes wildly at his reaching arms. He shrieks

like a cat and leaps back into a crouch.

Denya runs. She drops the dagger and grips the bowl in both hands,

trying desperately to keep the soup from sloshing out onto the ground. She

bursts out of the forest and into the empty land beyond. There is snow

falling, light and soft, and already there is a fine dusting of it all across the

ground. Denya stands heaving for a moment, trying to catch her breath.

There is a cracking sound behind her, and she whirls. A figure steps out

from the shadows of the forest, pale and thin. Her golden hair is full of

leaves, and her clothes are dirty and torn.

Denya stares. She is trembling, her breath still heavy and uncertain.

“Denya?” Bren asks and Denya cries out and runs to her wife and hugs

her tight with one arm.

“Is this real?” Bren asks. Her breath is hot against Denya’s ear, and they

both begin to cry.

“It’s real,” Denya weeps. “I’m real. I’m here.”

“It was like a dream,” Bren whispers. “I couldn’t wake up. I couldn’t …

couldn’t remember you.”

They stand for a time wrapped close together, breathing each other in,

sharing their warmth. When they kiss this time it is like waking, and their

bodies move in the old, familiar rhythms of their love.

Denya is the first to pull away. She takes Bren’s hand, still wrapped tight

around the lock of Eliya’s hair, and the two hurry back toward Maro’s

cottage. The old woman must hear them coming, for the door opens before

Denya can knock and the two rush inside. They kneel beside her daughter

and Denya lifts her head and helps her drink the still-warm broth from the

bowl of fairy soup. When Eliya has had a few sips, her eyes flutter open and

she takes a long deep breath. Denya puts her hand against Eliya’s cheek.

“My light,” she says, her voice thick with tears. “I found your mother.

She’s home!”

Eliya looks up to where Bren kneels wide-eyed beside Denya, and the girl

coughs and begins to cry, and for the first time in too long her cheeks warm

beneath her mothers’ hands.

The Vixen, With Death Pursuing

IZZY WASSERSTEIN

T

he river roars past me on its way down from the mountain, fed by a

long winter and a rain-soaked spring. It is a white foamed torrent,

radiating a cold so profound that I can feel it, even though I stand ten yards

away. I force myself to take deep breaths. The cold is so sharp that it hurts

my lungs. The scent I’m following is ahead of me, past the fury of the river.

I have no choice but to cross, or Ravenna will die, and many others with

her. The revolution needs me to succeed, so the fight against the Clenched

Fist can continue. But, I need Ravenna.

I pace back and forth along the bank, seeking the best way across and

gathering my courage. I have seen the masked soldiers of the Clenched Fist

march in lockstep and pull children from their parents’ arms. I have seen

two pyromancers duel, leaving a whole block scorched to glass. But the

river reminds me what true power is. I am awed before it.

Water does not usually frighten me, but this is a ferocity I have never

encountered, a torrent that would, if I slipped or misstepped, sweep me

away to my death, drowned or broken against the rocks.

The wind shifts, and my nose twitches. With my enhanced senses, I smell

it: the stench of corruption, of plague. The pestimancer pursues me, to

ensure my failure, Ravenna’s death, and the revolution’s collapse. He is

disease incarnate, and I’m nobody, not truly a revolutionary even though the

pestimancer’s masters would not agree. All I have against that is my fear for

the woman I love and a bit of vulpemancy.

I call on what little of the fox-magic I dare use, adding a bit of confidence

to my sharpened senses. The magic flows through me like a shadow on the

edge of sight, like a flash of orange disappearing into a hedgerow. It

steadies me, blunts the sharp edge of panic, but I’m still only a human

woman, far clumsier than any real fox.

I take two sharp breaths, tug nervously at the strap of the pouch looped

around my neck, and take my best option: a line of rocks jutting from the

water, mostly dry. I step toward the river and feel a chill run through me.

The cold of the water or my own fear? If I fall, I would freeze almost as fast

as I’d drown.

I force myself to move, to dart across on the balls of my feet. My instincts

may be partially a fox’s, but my body is very much human, and though my

phantom tail delights Ravenna, it does nothing to help with balance.

Halfway, one of the rocks turns under my foot. I sway, try to balance, but

my momentum carries me forward and I feel myself falling. I leap to the

next stone, waver, then crouch, fighting back vertigo. I force myself to stop,

to breathe. The river rushes past me, indifferent. Even the stone that nearly

killed me shows no sign of my passing.

I reach the far side and feel immediately exposed along the riverbank. I

can’t help but imagine the pestimancer watching me. When I close my eyes,

I still see him looming over Ravenna, her eyes rolled back, her tongue

lolling, while bloated flies buzz about him, and the air reeks of his taint. I

still see the moment when he turned and fixed the dark pits that should have

been his eyes on me. His voice was like tar pulling at bare feet:

“The Clenched Fist will not be defied. Behold the power of devotion—”

I push the memory aside, and dart into the forest, but I can’t help but look

back, and something rises through the trees, like heat off summer streets,

like an oil slick: miasma. He still pursues, and his power grows. I do not

know how he keeps himself intact, how little of the mage must remain now

that he has given himself so completely over to his art.

There aren’t many of us true mages. Anyone can do small stuff—light a

candle with a bit of pyromancy, push themselves through a sleepless night

with fortimancy. But true power, and true risk, comes by following a single

path. If a mage follows their path too far, embraces their subject too fully,

they become what they study. Some magical tomes were once

bibliomancers, and they say that thunder is the scream of a fulmenancer.

Most people lack the desire and focus to pursue one kind of magic, to

give up cantrips for deep understanding. And most of us mages are careful.

I know better than to rely too much on my magic. I like life in my human

body, thank you kindly, and only use enough magic to get by. I never

dreamt of doing more with my art. Until I met Ravenna, until my world

unsteadied.

The pestimancer, though, shows no fear, seems to revel in what he will

become. He has embraced his power fully. That level of devotion awes and

terrifies me. He will stop at nothing to see me fail.

The smell I seek is on the wind, the root-and-musk scent I pray leads me

to the arbouromancers, and I run after it, hoping to put distance between

myself and my pursuer.

I follow the scent further up the foothills. Gardrun City is only a few

hours from here, nestled in the valley, but the forest plays strange tricks

with sound, so that I can’t hear the city-noises at all. Everything in the

forest is far quieter than the city, and each crack of a branch or bird call

feels ominous.

Up in the hills the trees are a mix of evergreens and flowering trees

whose white branches are only beginning to bud with spring-green leaves.

Everywhere I look, nothing but trees, undergrowth, rocky outcroppings.

Without fox-senses I would be hopelessly lost. I should call on more power,

but I’m already risking as much as I dare.

When at last I reach the source of the smell, I stand blinking, despairing.

The forest here doesn’t look any different from the rest, at least not to my

city-dweller’s eyes, and there isn’t so much as a footprint to suggest the

passing of anyone. The smell is here, but it is strange, alien—

You have brought pestilence here, human. I whirl around, seeking the

source of the words, but I can see no one. You have violated this sacred

place. The voice—or is it voices?—sounds like the rustle of leaves, but

also, somehow, like the wind whipping through a tunnel. Quiet, yet

powerful, multifaceted. Relief floods me, and the tight grip of fear on my

heart eases.

“I didn’t bring the pestilence,” I say, trying to sound like Ravenna would,

confident and unyielding in the face of danger. I try not to sound like the

woman who wants to dart back to her warren, who for months was too

afraid to attend rebel gatherings. “I hate it as much as anyone.”

It seeks you, human, the voices say. Even now it brings sickness and

blight to the forest. Do not pretend this is not your doing.

Knowing the mages are here somewhere, I take in my surroundings anew.

Some of the trees here aren’t old growth, like the rest—they are shorter,

younger, grouped in a circle. A circle with me at the middle.

“I’m trying to cure the plague, not spread it,” I say, unable to keep the

urgency out of my voice. Even if the pestimancer may have struggled to

find a place to cross the river, he cannot be far behind. “The sooner I can do

that, the sooner he’ll be out of your forest.”

What do we care for the problems of your city, human? The voices ask.

You come here, cut trees, cloud the air with filth. You care nothing for us.

I had thought they would want to help me, but now I sense the depths of

their anger. The tightness in my chest redoubles. A fox would be clever, I

think, would adapt.

“I need an herb,” I say. “Purple, shot through with veins of yellow. They

say it cures blood-lung.” If it still exists. “Once I have it, I will go, and the

pestimancer will follow me and leave you in peace.”

Silence. I keep going, desperate to find the words to win them.

“The Clenched Fist unleashed this plague. They’re destroying everyone