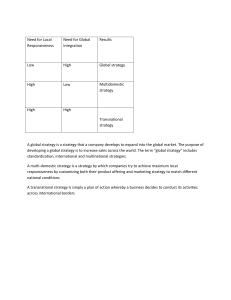

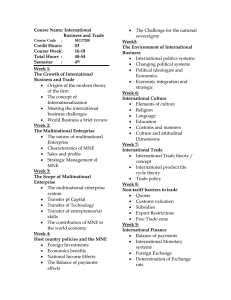

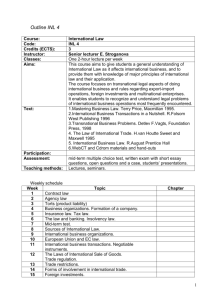

3 Developing Transnational Strategies Building Layers of Competitive Advantage In this chapter, we discuss how the numerous conflicting demands and pressures described in the first two chapters shape the strategic choices that MNEs must make. In this complex situation, an MNE determines strategy by balancing the motivations for its own international expansion with the economic imperatives of its industry structure and competitive dynamics, the social and cultural forces of the markets it has entered worldwide, and the political demands of its home- and host-country governments. To frame this complex analysis, this chapter examines how MNEs balance strategic means and ends to build the three required capabilities: globalscale efficiency and competitiveness, multinational flexibility and responsiveness, and worldwide innovation and learning. After defining each of the dominant historic strategic approaches – what we term classic multinational, international, and global strategies – we explore the emerging transnational strategic model that most MNEs must adopt today. Finally, we describe not only how companies can develop this approach themselves but also how they can defend against transnational competitors. The strategies of MNEs at the start of the twenty-first century were shaped by the turbulent international environment that redefined global competition in the closing decades of the twentieth century. It was during that turmoil that a number of different perspectives and prescriptions emerged about how companies could create strategic advantage in their worldwide businesses. Consider, for example, three of the most influential articles on global strategy published during the 1980s – the decade in which many new trends first emerged.1 Each is reasonable and intuitively appealing. What soon becomes clear, however, is that their prescriptions are very different and often contradictory, a reality that highlights not only the complexity of the strategic challenge that faced managers in large, worldwide companies but also the confusion of advice being offered to them. • Theodore Levitt argued that effective global strategy was not a bag of many tricks but the successful practice of just one: product standardization. Here the core of a 1 See Theodeore Levitt, “The globalization of markets,” Harvard Business Review, 61:3 (1983), 92–102; Thomas Hout, Michael E. Porter, and Eileen Rudden, “How global companies win out,” Harvard Business Review, 60:5 (1982), 98–109; Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad, “Do you really have a global strategy?” Harvard Business Review, 63:4 (1985), 139–49. 152 Developing Transnational Strategies global strategy lay in developing a standardized product to be produced and sold the same way throughout the world. • In contrast, an article by Michael Porter and his colleagues suggested that effective global strategy required the approach not of a hedgehog, who knows only one trick, but that of a fox, who knows many. These “tricks” include exploiting economies of scale through global volume, taking preemptive positions through quick and large investments, and managing interdependently to achieve synergies across different activities. • Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad’s prescription for a global strategy contradicted Levitt’s even more sharply. Instead of a single standardized product, they recommended a broad product portfolio, with many product varieties, so that investments in technologies and distribution channels could be shared. Crosssubsidization across products and markets, and the development of a strong worldwide distribution system were at the center of these authors’ view of how to succeed in the game of global chess. As we described in the preceding chapter, what was becoming increasingly clear during the next two decades was that to achieve sustainable competitive advantage, MNEs needed to develop layers of competitive advantage – global-scale efficiency, multinational flexibility, and the ability to develop innovations and leverage knowledge on a worldwide basis. And although each of the different prescriptions focuses on one or another of these different strategic objectives, the challenge for most companies today is to achieve all of them simultaneously. Worldwide Competitive Advantage: Goals and Means Competitive advantage is developed by taking strategic actions that optimize a company’s achievement of these three different and, at times, conflicting goals. In developing each of these capabilities, the MNE can utilize three very different tools and approaches, which we described briefly in Chapter 1 as the main forces motivating companies to internationalize. It can leverage the scale economies that are potentially available in its different worldwide activities, it can exploit the differences in sourcing and market opportunities among the many countries in which it operates, and it can capitalize on the diversity of its activities and operations to create synergies or develop economies of scope. The MNE’s strategic challenge therefore is to exploit all three sources of global competitive advantage – scale economies, national differences, and scope economies – to optimize global efficiencies, multinational flexibility, and worldwide learning. And thus the key to worldwide competitive advantage lies in managing the interactions between the different goals and the different means. The Goals: Efficiency, Flexibility, and Learning Let us now consider each of these strategic goals in a little more detail. Worldwide Competitive Advantage: Goals and Means 153 Global Efficiency Viewing an MNE as an input–output system, we can think of its overall efficiency as the ratio of the value of its outputs to the value of its inputs. In this simplified view of the firm, its efficiency could be enhanced by increasing the value of outputs (i.e., securing higher revenues), lowering the value of its inputs (i.e., lowering costs), or doing both. This is a simple point but one that is often overlooked: efficiency improvement is not just cost reduction but also revenue enhancement. To help understand the concept of global efficiency, we use the global integration–national responsiveness framework first developed by C. K. Prahalad (see Figure 3.1).2 The vertical axis represents the potential benefits from the global integration of activities – benefits that largely translate into lower costs through scale and scope economies. The horizontal axis represents the benefits of national responsiveness – those that result from the country-by-country differentiation of product, strategies, and activities. These benefits essentially translate into better revenues from more effective differentiation in response to national differences in tastes, industry structures, distribution systems, and government regulations. The framework can be used to understand differences in the benefits of integration and responsiveness at the aggregate level of industries, as well as to identify and describe differences in the strategic approaches of companies competing in the same industry. Also, as Figure 3.1 indicates, industry characteristics alone do not determine company strategies. In automobiles, for example, Fiat historically pursued a classical multinational strategy, helping establish national auto industries through its joint venture partnerships and host government support in Spain, Poland, and many other countries with state-sponsored auto industries. Toyota, by contrast, succeeded originally by developing products and manufacturing them in centralized, globally scaled facilities in Japan. A “regional” strategy becomes feasible when geographic regions or groups of countries are sufficiently large and internally homogeneous markets but differ substantially from other regions or groups. Honda has implemented such an approach by dividing its organization into six autonomous geographical regions – North America, Japan, Europe, China, Asia, and the Middle East. In addition to manufacturing and marketing global models such as the Civic and the Accord, each region manages the full value chain for specific regional models such as the Pilot in North America and the Brio series in Asia. This sort of strategic choice to focus on the objective of global efficiency (rather than local responsiveness) creates vulnerabilities and challenges as well as clear benefits. Multinational Flexibility A worldwide company faces an operating environment characterized by diversity and volatility. Some opportunities and risks generated by this environment are 2 For a detailed exposition of this framework, see C. K. Prahalad and Yves Doz, The Multinational Mission (New York: The Free Press, 1987). 154 Developing Transnational Strategies Figure 3.1 The integration–responsiveness framework Christopher A. Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal, Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1989). endemic to all firms; others, however, are unique to companies operating across national borders. A key element of worldwide competitiveness therefore is multinational flexibility – the ability of a company to manage the risks and exploit the opportunities that arise from the diversity and volatility of the global environment.3 Although there are many sources of diversity and volatility, it is worth highlighting four that we regard as particularly important. First, there are macroeconomic risks that are completely outside the control of the MNE, such as changes in prices, factor costs, or exchange rates caused by wars, natural calamities, or economic cycles. Second, there are political risks that arise from policy actions of national governments, such as managed changes in exchange rates or interest rate adjustments, or events that are related to political instability. Third, there are competitive risks arising from the uncertainties of competitors’ responses to the MNE’s own strategies. And fourth, there are resource risks, such as the availability of raw materials, capital, or managerial talent. In all four categories, the common characteristic of the various types of risks is that they vary across countries and change over time. This variance makes flexibility the key strategic management requirement, because diversity and volatility create attendant opportunities that must be considered jointly. In general, multinational flexibility requires management to scan its broad environment to detect changes and discontinuities and then respond to the new situation in the context of the worldwide business. MNEs following this approach exploit their exposure to diverse and dynamic environments to develop strategies – and structures – in more general and more flexible terms so as to be robust to different international environmental scenarios. For example, having a network of affiliated subsidiaries that emphasize global exports rather than individual local 3 This issue of multinational flexibility is discussed more fully in Bruce Kogut, “Designing global strategies: profiting from operating flexibility,” Sloan Management Review, Fall (1985), 27–38. Worldwide Competitive Advantage: Goals and Means 155 markets provides a flexibility to shift production when a particular national market faces an economic crisis.4 Worldwide Learning Most existing theories of the MNE view it as an instrument to extract additional revenues from internalized capabilities. The assumption is that the firm goes abroad to make more profits by exploiting its technology, brand name, or management capabilities in different countries around the world. And most traditional theory assumes that the key competencies reside at the MNE’s center. Although the search for additional profits or the desire to protect existing revenues may explain why MNEs come to exist, it does not provide a complete explanation of why some of them continue to grow and flourish. As we suggested in Chapter 1, an alternative view may well be that a key asset of the multinational is the diversity of environments in which it operates. This diversity exposes the MNE to multiple stimuli, allows it to develop diverse capabilities, and provides it with broader learning opportunities than are available to a purely domestic firm. Furthermore, its initial stock of knowledge provides the MNE with strength that allows it to create organizational diversity in the first place. In Chapter 5, we engage in a detailed discussion of the approaches that MNEs use to deliver on the objective of worldwide learning. The Means: National Differences, Scale, and Scope Economies There are three fundamental tools for building worldwide competitive advantage: exploiting differences in sourcing and market potential across countries, exploiting economies of scope, and exploiting economies of scale. In this section, we explore each of them in more depth. National Differences In the absence of efficient markets, the fact that different nations have different factor endowments (e.g., an abundance of labor, land, materials) leads to intercountry differences in factor costs. Because different activities of the firm, such as R&D, production, or marketing, use various factors to different degrees, a firm can gain cost advantages by configuring its value chain so that each activity is located in the country that has the least cost for its most intensively used factor. For example, R&D facilities may be placed in the UK because of the available supply of high-quality, yet relatively modestly paid, scientists; manufacturing of laborintensive components may be undertaken in Malaysia to capitalize on the lower cost, efficient labor force; and software development could concentrate in India, 4 Additional examples of multinational flexibility are discussed in Tony Tong and Jeffrey Reuer, “Real options in multinational corporations: organizational challenges and risk implications,” Journal of International Business Studies, 38:2 (2007), 215–30. 156 Developing Transnational Strategies where skilled software engineers are paid a fraction of Western salaries. Initially, General Electric’s “global product concept” was set up to concentrate manufacturing wherever it could be implemented in the most cost-effective way (while still retaining quality). Over time, however, changes in cost structures, the threat of imitators, and the pursuit of control over the supply chain eventually led the company to move back some of the manufacturing sites to the United States.5 This highlights the fact that global situations are rarely stable over long periods of time, and that MNE strategy must above all be flexible and responsive to changing differences in home- and host-country environments. Market potential varies across countries In the October 2016 World Economic Outlook (WEO) by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), growth in emerging market and developing economies was expected to account for more than three-quarters of projected world growth. In January 2017, the IMF released an updated WEO, which projected emerging market and developing economies growth at 4.5% in 2017. PwC predicts that the E7 economies (China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, Turkey, and Mexico) could be double the size of the G7 by 2050 in terms of purchasing power parity.6 National differences may also exist in output markets. As we have discussed, distribution systems, government regulations, the effectiveness of different promotion strategies, and customer tastes and preferences may vary in different countries. In order to exploit national differences, companies may need to reshuffle their business models. For example, the growing middle classes in emerging markets will have different needs and priorities than those that most of the current business models address.7 They may still have very basic unmet needs (e.g., refrigeration and clothes washing) that require a different value proposition versus the business model existing in advanced markets. Much more of the average household income in emerging markets is spent on food and transportation whereas this figure in the United States is 25%. For companies operating in emerging economies, addressing such needs is not a matter of transferring their existing business models and adjusting them with small tweaks. Instead, MNEs will sometimes need to rethink their business models, so as to solve problems such as accessibility and affordability. To illustrate, consider whether consumer needs in emerging economies are basically local or global. Fashion products and personal banking are examples of global needs, while economy cars and basic and affordable home appliances are exemplars of local needs in these markets. Depending on each of the four categories of the needs and consumer combinations shown in Figure 3.2, companies can develop strategies to better serve middle-class consumers there. 5 6 7 Jeffrey R. Immelt, “The CEO of General Electric on sparking an American manufacturing renewal,” Harvard Business Review, 90 (2012), 43–6. John Hawksworth, Hannah Audino, Rob Clarry, and Duncan McKellar, “The long view: how will the global economic order change by 2050?” in The World in 2050 (PwC, 2017), p. 54. David Court and Laxman Narasimhan, “Capturing the world’s emerging middle class,” McKinsey Quarterly, 3 (2010), 12–17. Worldwide Competitive Advantage: Goals and Means 157 Middle-class consumers’ needs Middle-class consumers’ ability to buy High Low Local Global Shape or localize Create a platform Reinvent business model Target niche Figure 3.2 Category-specific strategies to help companies serve middle-class consumers in emerging economies Source: Condensed from David Court and Laxman Narasimhan, “Capturing the world’s emerging middle class,” McKinsey Quarterly, 3 (2010), 12–17. As we will also see in many case examples, a firm can obtain higher prices for its output by tailoring its offerings to fit the unique requirements in each national market. Scale Economies Microeconomic theory provides a strong basis for evaluating the effect of scale on cost reduction, and the use of scale as a competitive tool is common in industries ranging from roller bearings to semiconductors. Whereas scale, by itself, is a static concept, there may be dynamic benefits of scale through what has been variously described as the experience or learning effect. The higher volume that helps a firm to exploit scale benefits also allows it to accumulate learning,8 which leads to progressive cost reduction as the firm moves down its learning curve. So although emerging Korean electronics firms were able to match the scale of experienced Japanese competitors, it took them many years before they could finally compensate for the innumerable process-related efficiencies the Japanese had learned after decades of operating their global-scale plants. Scope Economies The concept of scope economies is based on the notion that certain economies arise from the fact that the cost of the joint production (or development or distribution) of two or more products can be less than the cost of producing them separately.9 Such cost reductions may take place for many reasons – for example, resources such as information or technologies, once acquired for use in producing one item (television sets, for example), are available without cost for production of other items (video players, for instance). 8 9 For an understanding that accumulation of learning may differ across different firms, see Jaeyong Song, “Subsidiary absorptive capacity and knowledge transfer within multinational corporations,” Journal of International Business Studies, 45:1 (2014), 73–84. For a detailed exposition of scope economies, see David J. Teece, “Economies of scope and the scope of the enterprise,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 1:3 (1980), 223–47. 158 Developing Transnational Strategies Table 3.1 Scope economies in product and market diversification Sources of scope economics Shared physical assets Shared external relations Shared learning Product diversification Market diversification Factory automation with flexibility to produce multiple products (Ford) Using common distribution channels for multiple products (Samsung) Shared R&D in computer and communications business (NEC) Global brand name (Apple) Servicing multinational customers worldwide (Citibank) Pooling knowledge developed in different markets (P&G) Source: Adapted from Prahalad (1987). The strategic importance of scope economies arises from a diversified firm’s ability to share investments and costs across the same or different value chains – a source of economies that competitors without such internal and external diversity cannot match. Such sharing can take place across segments, products, or markets and may involve the joint use of different kinds of assets (see Table 3.1). Implicit with each of these tools is the ability to develop an organizational infrastructure that supports it. As we discuss in later chapters, the organizational ability to leverage a global network and value chain will differentiate the winners and losers. Mapping Ends and Means: Building Blocks for Worldwide Advantage Table 3.2 shows a mapping of the different goals and means for achieving worldwide competitiveness. Each goals–means intersection suggests some of the factors that may enhance a company’s strategic position. Although the factors are only illustrative, it may be useful to study them carefully and compare them against the proposals of the three academic articles mentioned at the beginning of the chapter. It will become apparent that each author focuses on a specific subset of factors – essentially, some different goals–means combinations – and the differences among their prescriptions can be understood in terms of the differences in the particular aspect of worldwide competitive advantage on which they focus. International, Multinational, Global, and Transnational Strategies In Chapter 2, we described how environmental forces in different industries shaped alternative approaches to managing worldwide operations that we described as international, multinational, global, and transnational. We now elaborate on the International, Multinational, Global, and Transnational Strategies 159 Table 3.2 Worldwide advantage: goals and means Sources of competitive advantage Strategic objectives National differences Scale economies Scope economies Achieving efficiency in current operations Managing risks through multinational flexibility Benefiting from differences in factor costs – wages and cost of capital Expanding and exploiting potential scale economies in each activity Balancing scale with strategic and operational flexibility Sharing of investments and costs across markets and businesses Portfolio diversification of risks and creation of options and side bets Benefiting from experience – cost reduction and innovation Shared learning across organizational components in different products, markets, or businesses Innovation, learning, and adaptation Managing different kinds of risks arising from market- or policyinduced changes in comparative advantages of different countries Learning from societal differences in organizational and managerial processes and systems distinctions among these different approaches, as well as their respective strengths and vulnerabilities in terms of the different goals–means combinations we have just described. International Strategy Companies adopting this broad approach focus on creating and exploiting innovations on a worldwide basis, using all the different means to achieve this end. MNEs headquartered in technologically advanced countries with sophisticated markets often adopted this strategic approach but limited it primarily to exploiting homecountry innovations to develop their competitive positions abroad. The international product cycle theory we described in Chapter 1 encompasses both the strategic motivation and competitive posture of these companies: at least initially, their internationalization process relied heavily on transferring new products, processes, or strategies developed in the home country to less advanced overseas markets. This approach was common among US-based MNEs such as Kraft, Pfizer, P&G, and General Electric. Although these companies built considerable strength out of their ability to create and leverage innovation, many suffered from deficiencies of both efficiency and flexibility because they did not develop either the centralized and high-scale operations of companies adopting global strategies or the very high degree of local responsiveness that multinational companies could muster through their autonomous, self-sufficient, and entrepreneurial local operations. This deficiency has led some of the companies in this category to change. Kraft, for example, 160 Developing Transnational Strategies in an effort to leverage its iconic North American brands in the global snack business, created a new subsidiary Mondelez International Inc. – hence its efficiency stand. At the same time, its North America-focused grocery business aims to have flexibility and local responsiveness in this line of business. Johnnie Walkers in turn, pursued both a global and local (glocal) advertising strategy with their “Keep Walking” campaign. The elements of the campaign were slightly modified depending on the culture and market it appeared in; however, the underlying message was retained. They have more than doubled their global business in ten years and have changed the Johnnie Walker and Scotch whisky business globally.10 Multinational Strategy The multinational strategic approach focuses primarily on one means (national differences) to achieve most of its strategic objectives. Companies adopting this approach tend to focus on the revenue side, usually by differentiating their products and services in response to national differences in customer preferences, industry characteristics, and government regulations. This approach leads most multinational companies to depend on local-for-local innovations, a process requiring the subsidiary to not only identify local needs but also use its own local resources to respond to those needs. Carrying out most activities within each country on a localfor-local basis also allows those adopting a multinational strategy to match costs and revenues on a currency-by-currency basis. Historically, many European companies, such as Unilever, ICI, Philips, and Nestlé, followed this strategic model. In these companies, assets and resources historically were widely dispersed, allowing overseas subsidiaries to carry out a wide range of activities from development and production to sales and services. Their selfsufficiency was typically accompanied by considerable local autonomy. But, although such independent national units were unusually flexible and responsive to their local environments, they inevitably suffered problems of inefficiencies and an inability to exploit the knowledge and competencies of other national units. These inefficiencies have led some of these companies to change. The CEO of Unilever, for example, in its 2011 annual report expressed that: “We are changing the organization. Today we are more agile, more consumer responsive and better able to leverage global scale.” Yet by 2017, the same CEO said, “it has seen the world become more ‘multipolar’ with local tastes and nationalism playing a bigger role in consumers’ lives.” Global Strategy Companies adopting the classic global strategic approach, as we have defined it, depend primarily on developing global efficiency. They use all the different means to achieve the best cost and quality positions for their products. 10 Jerry Wind, Stan Sthanunathan, and Rob Malcolm, “Great advertising is both local and global,” Harvard Business Review, March 29 (2013). Accessed March 13, 2017, https://hbr.org/2013/03/ great-advertising-is-both-loca. International, Multinational, Global, and Transnational Strategies 161 This means has been the classic approach of many Japanese companies such as Toyota, Canon, Komatsu, and Matsushita (Panasonic). As these and other similar companies have found, however, such efficiency comes with some compromises of both flexibility and learning. For example, concentrating manufacturing to capture global scale may also result in a high level of intercountry product shipments that can raise risks of policy intervention, particularly by host governments in major importer countries. Similarly, companies that centralize R&D for efficiency reasons often find they are constrained in their ability to capture new developments in countries outside their home markets or to leverage innovations created by foreign subsidiaries in the rest of their worldwide operations. And, finally, the concentration (most often through centralization) of activities such as R&D and manufacturing to achieve a global scale exposes such companies to high sourcing risks, particularly in exchange rate exposure. As an example, the 2011 earthquake in Japan was so harmful to Canon that it announced it was pursuing a new regional headquarters management system (one headquarters each in the United States, Europe, and Japan) to manage its local product developments. Each has the authority to roll out businesses globally. The descriptions we have presented to this point regarding multinational versus global strategies have been mostly described in their pure forms. In practice, of course, many firms do adopt a regional strategy, focusing much of their international expansion on the home region, plus perhaps one or two other regions. Ford Motor Company, for example, operates two manufacturing plants in India and has invested over $2 billion since 1995. The Ford Next-Gen Figo, Aspire, and EcoSport models are exported to over 40 markets. Transnational Strategy Beneath each of these three traditional strategic approaches lies some implicit assumptions about how best to build worldwide competitive advantage. The global company assumes that the best cost position is the key source of competitiveness; the multinational company sees differentiation as the primary way to enhance performance; and the international company expects to use innovations to reduce costs, enhance revenues, or both. Companies adopting the transnational strategy recognize that each of these traditional approaches is partial, that each has its own merits, but none represents the whole truth. To achieve worldwide competitive advantage, costs and revenues have to be managed simultaneously, both efficiency and innovation are important, and innovations can arise in many different parts of the organization. Therefore instead of focusing on any subpart of the set of issues shown in Table 3.2, the transnational company focuses on exploiting each and every goals–means combination to develop layers of competitive advantage by exploiting efficiency, flexibility, and learning simultaneously. To achieve this ambitious strategic approach, however, the transnational company must develop a very different configuration of assets and capabilities than is typical of traditional multinational, international, and global company structures. The 162 Developing Transnational Strategies global company tends to concentrate all its resources – either in its home country or in low-cost overseas locations – to exploit the scale economies available in each activity. The multinational company typically disperses its resources among its different national operations to be able to respond to local needs. And the international company tends to centralize those resources that are key to developing innovations but decentralize others to allow its innovations to be adapted worldwide. The transnational, however, must develop a more sophisticated and differentiated configuration of assets and capabilities. It first decides which key resources and capabilities are best centralized within the home-country operation, not only to realize scale economies but also to protect certain core competencies and provide the necessary supervision of corporate management. Basic research, for example, is often viewed as such a capability, with core technologies kept at home for reasons of strategic security as well as competence concentration. Certain other resources may be concentrated but not necessarily at home – a configuration that might be termed “ex-centralization” rather than decentralization. World-scale production plants for labor-intensive products may be built in a lowwage country such as Mexico or Bangladesh. The advanced state of a particular technology may demand concentration of relevant R&D resources and activities in Japan, Germany, or the United States. Such flexible specialization – or excentralization – complements the benefits of scale economies with the flexibility of accessing low input costs or scarce resources and the responsiveness of accommodating national political interests. This approach can also apply to specific functional activities. For example, McDonald’s moved its international tax base to Britain. This holding company would receive royalties from licensing deals outside the United States. Earlier, Amsterdam-based software company Irdeto opened a second headquarters in Beijing to enhance the influence of its managers in the fast-growing Chinese market on the company’s decision-making processes. To underscore the commitment, the CEO and his family moved to China in 2007. Some other resources may best be decentralized on a regional or local basis because either potential economies of scale are small or there is a need to create flexibility by avoiding exclusive dependence on a single facility. Local or regional facilities may not only afford protection against exchange rate shifts, strikes, natural disasters, and other disruptions, but also reduce logistical and coordination costs. An important side benefit provided by such facilities is the impact they can have in building the motivation and capability of national subsidiaries, an impact that can easily make small efficiency sacrifices worthwhile. Table 3.3 summarizes the differences in the asset configurations that support the different strategic approaches of the various MNE models. We explore these strategy–organizational linkages in more detail in Chapter 4. Worldwide Competitive Advantage: The Strategic Tasks In the final section of this chapter, we look at how a company can respond to the strategic challenges we have described. The task will clearly be very different Worldwide Competitive Advantage: The Strategic Tasks 163 Table 3.3 Strategic orientation and configuration of assets and capabilities in international, multinational, global, and transnational companies Strategic orientation Configuration of assets and capabilities International Multinational Global Transnational Exploiting parentcompany knowledge and capabilities through worldwide diffusion and adaptation Sources of core competencies centralized, others decentralized Building flexibility to respond to national differences through strong, resourceful, and entrepreneurial national operations Building cost advantages through centralized, global-scale operations Decentralized and nationally selfsufficient Centralized and globally scaled Developing global efficiency, flexibility, and worldwide learning capability simultaneously Dispersed, interdependent, and specialized depending on the company’s international posture and history. Companies that are among the major worldwide players in their businesses must focus on defending their dominance while also building new sources of advantage. For companies that are smaller, but aspire to worldwide competitiveness, the task is one of building the resources and capabilities needed to challenge the entrenched leaders. And for companies that are focused on their national markets and lack either the resources or the motivation for international expansion, the challenge is to protect their domestic positions from others that have the advantage of being MNEs. Defending Worldwide Dominance In recent decades, the shifting external forces we have described have resulted in severe difficulties – even for those MNEs that had enjoyed strong historical positions in their businesses worldwide. Typically, most of these companies pursued traditional multinational, international, or global strategies, and their past successes were built on the fit between their specific strategic capability and the dominant environmental force in their industries. In multinational industries such as branded packaged products, in which forces for national responsiveness were dominant, companies such as Unilever developed strong worldwide positions by adopting multinational strategies. In contrast, in global industries such as consumer electronics or semiconductor chips, companies such as Panasonic or Hitachi built leadership positions by adopting global strategies. In the emerging competitive environment, however, these companies could no longer rely on their historic ability to exploit global efficiency, multinational flexibility, or worldwide learning. As an increasing number of industries developed what we have termed transnational characteristics, companies faced the need to master all three strategic capabilities simultaneously. 164 Developing Transnational Strategies The challenge for the leading companies was to protect and enhance the particular strength they had while simultaneously building the other capabilities. For many MNEs, the initial response to this new strategic challenge was to try to restructure the configuration of their assets and activities to develop the capabilities they lacked. For example, global companies with highly centralized resources sought to develop flexibility by dispersing resources among their national subsidiaries; multinational companies, in contrast, tried to emulate their global competitors by centralizing R&D, manufacturing, and other scale-intensive activities. In essence, these companies tried to find a new “fit” configuration through drastic restructuring of their existing configuration. Such a zero-based search for the ideal configuration not only led to external problems, such as conflict with host governments over issues like plant closures, but also resulted in trauma inside the company’s own organization. The greatest problem with such an approach, however, was that it tended to erode the particular competency the company already had without effectively adding the new strengths it sought.11 The complex balancing act of protecting existing advantages while building new ones required companies to follow two fairly simple principles. First, they had to concentrate at least as much on defending and reinforcing their existing assets and capabilities as on developing new ones. Their approach tended to be one of building on – and eventually modifying – their existing infrastructure instead of radical restructuring. To the extent possible, they relied on modernizing existing facilities rather than dismantling the old and creating new ones. Second, most successful adaptors looked for ways to compensate for their deficiency or approximate a competitor’s source of advantage, rather than trying to imitate its asset structure or task configuration. In searching for efficiency, multinational companies with a decentralized and dispersed resource structure found it easier to develop efficiency by adopting new flexible manufacturing technologies in some of their existing plants and upgrading others to become global or regional sources, rather than to close those plants and shift production to lower cost countries to match the structure of competitive global companies. Similarly, successful global companies found it more effective to develop responsiveness and flexibility by creating internal linkages between their national sales subsidiaries and their centralized development or manufacturing units, rather than trying to mimic multinational companies by dispersing their resources to each country operation and, in the process, undermining their core strength of efficiency. Challenging the Global Leader A number of companies have managed to evolve from relatively small national players to major worldwide competitors, challenging the dominance of traditional 11 For a discussion about the dynamic capabilities perspective, see John Cantwell, “Revisiting international business theory: a capabilities-based theory of the MNE,” Journal of International Business Studies, 45:1 (2014), 1–7. Worldwide Competitive Advantage: The Strategic Tasks 165 leaders in their businesses. Dell in the computer industry, Magna in auto parts, Electrolux in the domestic appliances business, and CEMEX in the cement industry are examples of companies that have evolved from relative obscurity to global visibility within relatively short periods of time. The actual processes adopted to manage such dramatic transformations vary widely from company to company. Electrolux, for example, grew almost exclusively through acquisitions, whereas Dell built capabilities largely through internal development, and Magna and CEMEX used a mix of greenfield investments and acquisitions. Similarly, whereas Dell built its growth on the basis of cost advantages and logistics capabilities, it expanded internationally because of its direct sales business model and its ability to react quickly to changes in customer demand. Despite wide differences in their specific approaches, however, most of these new champions appear to have followed a similar step-by-step approach to building their competitive positions. Each developed an initial toehold in the market by focusing on a narrow niche – often one specific product within one specific market – and developing a strong competitive position within that niche. That competitive position was built on multiple sources of competitive advantage rather than on a single strategic capability. Next, they expanded their toehold to a foothold by limited and carefully selected expansion along both product and geographic dimensions and by extending the step-by-step improvement of both cost and quality to this expanded portfolio. Such expansion was sometimes focused on products and markets that were not of central importance to the established leaders in the business. By staying outside the range of the leaders’ peripheral vision, the challenger could remain relatively invisible, thereby building up its strength and infrastructure without incurring direct retaliation from competitors with far greater resources. For example, emerging companies often focused initially on relatively low-margin products such as small-screen TV sets or subcompact cars. While developing their own product portfolio, technological capabilities, geographic scope, and marketing expertise, challengers were often able to build up manufacturing volume and its resulting cost efficiencies by becoming original equipment manufacturer suppliers to their larger competitors. Although this supply allowed the larger competitor to benefit from the challenger’s cost advantages, it also developed the supplying company’s understanding of customer needs and marketing strategies in the advanced markets served by the leading companies. Once these building blocks for worldwide advantage were in place, the challenger typically moved rapidly to convert its low-profile foothold into a strong permanent position in the worldwide business. Dramatic scaling up of production facilities typically preceded a wave of new product introductions and expansion into the key markets through multiple channels and their own brand names. Another way a challenger may pursue rapid transition into a strong international presence is through acquisitions, as Shuanghui International did in 2013 with the acquisition of Smithfield Foods or as Qingdao Haier Company did in 2016 with the acquisition of General Electric’s appliance business. These deals were valued at $7.1 billion and $5.4 billion respectively. 166 Developing Transnational Strategies Protecting Domestic Niches For reasons of limited resources or other constraints, some national companies may not be able to aspire to such worldwide expansion, although they are not insulated from the impact of global competition. Their major challenge is to protect their domestic niches from worldwide players with superior resources and multiple sources of competitive advantage.12 This concern is particularly an issue in developing markets such as India and China, where local companies face much larger, more aggressive, and deeper pocketed competitors. There are three broad alternative courses of action that can be pursued by such national competitors. The first approach is to defend against the competitor’s global advantage. Just as MNE managers can act to facilitate the globalization of industry structure, so their counterparts in national companies can use their influence in the opposite direction. An astute manager of a national company might be able to foil the attempts of a global competitor by taking action to influence industry structure or market conditions to the national company’s advantage. These actions might involve influencing consumer preference to demand a more locally adapted or service-intensive product; it could imply tying up key distribution channels; or it might mean preempting local sources of critical supplies. Many companies trying to enter the Japanese market claim to have faced this type of defensive strategy by local firms. A second strategic option would be to offset the competitor’s global advantage. The simplest way to do this is to lobby for government assistance in the form of tariff protections. However, in an era of declining tariffs, this is increasingly unsuccessful. A more ambitious approach is to gain government sponsorship to develop equivalent global capabilities through funding of R&D, subsidizing exports, and financing capital investments. As a “national champion,” the company would theoretically be able to compete globally. However, in reality, it is very unusual for such a company to prosper. Airbus Industrie, which now shares the global market for large commercial airplanes with Boeing, is one of the few exceptions – rising from the ashes of other attempts by European governments to sponsor a viable computer company in the 1970s and then to promote a European electronics industry a decade later. Also, General Electric’s lobbying activities in 2009 led to its inclusion in the bailout program of the US government. The third alternative is to approximate the competitors’ global advantages by linking up in some form of alliance or coalition with a viable global company. Numerous such linkages have been formed with the purpose of sharing the risks and costs of operating in a high-risk global environment. By pooling or exchanging market access, technology, and production capability, smaller competitors can gain some measure of defense against global giants. For example, in March 2017, a memorandum of understanding was signed between Volkswagen and India’s Tata Motors. This agreement will allow them to explore a partnership of developing auto components and vehicles for the Indian market and more. Both companies have 12 For a detailed discussion, see Niraj Dawar and Tony Frost, “Competing with giants: survival strategies for local companies competing in emerging markets,” Harvard Business Review, 77:2 (1999), 119–30. 167 fallen behind in the Indian market against competitors such as Hyundai and Maruti Suzuki. Similarly, the Indian telecom company Bharti has established a variety of inbound alliances with foreign firms to create a winning strategy for the Indian market and is now one of the top telecom companies in the world. CONCLUDING COMMENTS Although these three strategic responses obviously do not cover every possible scenario, they highlight two important points from this chapter. First, the MNE faces a complex set of options in terms of the strategic levers it can pull to achieve competitive advantage, and the framework in Table 3.2 helps make sense of those options by separating out means and ends. Second, the competitive intensity in most industries is such that a company cannot solely afford to do something different from what other companies do. Rather, it is necessary to gain competitive parity on all relevant dimensions (efficiency, flexibility, learning) while also achieving differentiation on one. To be sure, the ability to achieve multiple competitive objectives at the same time is far from straightforward and, as a result, we see many MNEs experimenting with new ways of organizing their worldwide activities. And this organization will be the core issue we will address in the next chapter.