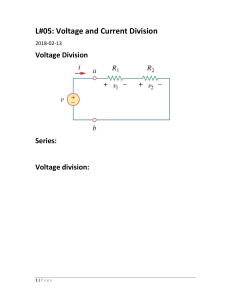

EUROPEAN TRANSACTIONS ON ELECTRICAL POWER Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 Published online 11 August 2008 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/etep.281 Influence of line routing and terminations on transient overvoltages in LV power installations Ibrahim A. Metwally1,2*,y and Fridolin H. Heidler3 1 2 Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, College of Engineering, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman 3 University of the Federal Armed Forces, Munich, EIT 7, D-85577 Neubiberg, Germany SUMMARY IEC 62305-4 gives the rules for the selection and the installation of surge protective devices (SPDs), where the maximum enhancement factor is considered to be equal to 2 in the worst case of open-circuit condition. The objective of the present paper is to check this relation for equipment connected to low-voltage (LV) power system. The LV power system is considered as TN-S system with different routings in three- and six-storey buildings. The terminals of apparatus are substituted by a variety of different loads, namely, resistances, inductances, and capacitances. All Maxwell’s equations are solved by the method of moments (MoM) and the voltage is calculated at the apparatus terminals. The SPD itself is simulated by a voltage source at the ground floor. The results reveal that the voltage at the apparatus terminals may overshoot the SPD protection level by a factor of 3 irrespective of the number of floors and loops. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. key words: enhancement factor; branching; low-voltage installation; method of moments; residual voltage; routing; surge protective device (SPD); silicon avalanche diodes; protective distance; protective level; loops 1. INTRODUCTION The new generations of integrated circuits have very thin layers with thickness of just several nanometers which makes the equipment to be more susceptible to electromagnetic interferences. Frequent abrupt damage and non-predictable lasting effects in integrated circuits of equipment are attributed to transients induced in and propagated into low-voltage (LV) power installations [1–3]. These overvoltages may be of magnitudes that are dangerous for control units and instruments and can cause resetting of microprocessor-based electronic systems, temporary disturbance, or internal data corruption. The control of the electromagnetic interferences has become the dominant task of lightning protection. The basic philosophy of protection against lightning has been developed by the committee IEC TC 81 and has been presented in the standard series IEC 62305 [2,4,5]. IEC 62305-3 [5] gives the rules for the installation of the lightning protection system (LPS) to protect structure against direct lightning strikes. The LPS consists of the external and the internal lightning protection systems. Components of the external LPS are the air termination system, the downward conductor system and the earth termination system. The functions of the external LPS are to intercept the lightning flash, to conduct the lightning flash safely to earth and to disperse it to the earth. Components of the internal LPS are the lightning equipotential bonding and the separation distance between the external LPS and the volume to be protected. The function of the internal lightning protection is to prevent dangerous sparking within the structure. However, the LPS does not provide sufficient protection for the electrical and electronic equipment installed inside the structure [2]. To reduce the probability of failure of electrical and electronic systems within a structure, adequate equipotential bonding of the internal system should be adopted. Surge protective devices (SPDs) are the most convenient devices in order to achieve the *Correspondence to: Ibrahim A. Metwally, Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt. y E-mail: metwally@mans.edu.eg Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 1054 I. A. METWALLY AND F. H. HEIDLER equipotential bonding for live conductors of incoming lines and connected internal live circuits. The requirements, testing procedures and principles for the selection, and application of SPD are given in IEC 61643 [6]. The SPDs can be generally divided into two categories, namely, nonlinear and linear components [7,8]. Nonlinear group includes transient suppressers diodes, metal–oxide varistors (MOVs), spark gaps, and gas-filled surge arresters. Linear group of components includes capacitors, inductors, resistors, or their combination filters. The main disadvantage of linear SPDs is that they cannot withstand high-energy surges as the lightning currents. Therefore, in LV power installations only nonlinear SPDs are used for lightning protection [9]. The response time of MOVs is typically 1 –10 ns. The characteristics of the power system and a facility’s wiring limit the rise times of transients to tens or hundreds of nanoseconds [8,9]. It is of significant importance to differentiate between the lightning-voltage front time and the SPD’s claming time. The incoming overvoltage is damped as soon as it reaches the protection level of the SPD. In the case of lightning, this fact may reduce the front time of the residual voltage very much compared to front time of the associated lightning current irrespective of the SDP type. Hence, there is no correlation between the lightning front time and the SPD’s claming time. The principle of lightning protection zones (LPZs) requires that the SPDs are installed subsequently in the same circuit. The tripping of the SPDs creates residual voltages which may have very short rise time. In this case, if the circuit between the SPD and apparatus is too long, the propagation of the surges leads to oscillation phenomenon. According to Annex D of the international standard IEC 62305-4 [2], in the case of open circuit at apparatus terminals, this can increase the overvoltage at the terminals of apparatus up to the double of the SPD protection level. This presumption is based on studies considering the simple case of coaxial cable with an inner live conductor and a grounded outer shield [10,11]. In Annex D of IEC 62305-4 [2], furthermore the protective distance is introduced in order not to exceed the impulse withstand voltage at the apparatus terminals. The protective distance is defined by the maximum length of the circuit between SPD and apparatus, for which protection of the SPD is effective for the apparatus. In practice, however, this method is difficult to be realized because the protective distance may be very short down to the range of some meters [10,12]. Therefore, in Annex D of IEC 62305-4 [2], an alternative method is presented. This method takes into account that the SPD residual voltage may be doubled at the apparatus terminals. Consequently, the protective level of the SPD has to be reduced to at least the half of the impulse withstand voltage of the apparatus terminals. The objective of the present paper is to check these relations for equipment connected to low-voltage (LV) power system. In fact, it is very difficult to predict the transient response of the LV power networks, because the LV power installations are often very complex [13]. Typically, they have a great diversity of connected loads, the number and location of the conductors, and the number of branches and routings. Therefore, the amplitude and the waveform of the transient overvoltages in LV power installations are influenced by many factors including the earthing condition [14]. In the present study, the LV power installation network is taken into account for a single-phase TN-S system consisting of the live conductor L, the neutral conductor N and the protective earth conductor PE. Generally screened rooms are assumed where the lightning electromagnetic fields are lowered to negligible low levels. Such screened rooms typically exist for LPZ 2 or higher. Consequently, the interaction of the lightning electromagnetic field is ignored. 2. COMPUTATIONAL APPROACH Normally metal-oxide varistor (MOV) based SPDs are installed at the boundary of LPZ 2 or higher LPZ [2]. These MOV-based SPDs typically reduce the incoming overvoltage to a residual voltage with approximately constant voltage level. In the present paper, the SPD residual voltage is taken into account by a step voltage with a linear-rising front up to the peak value as follows umax ttf ; 0 t tf uðtÞ ¼ (1) ; t > tf umax where umax is the peak value and tf is the front time. The incoming overvoltage is limited as soon as it reaches the protection level of the SPD. In the case of lightning strike, this fact may reduce the front time of the residual voltage very much compared to front time of the associated lightning current. In the simulations, it is taken into account by varying the front time from 0.01 ms to 1 ms. Because the objective of the paper is the evaluation of the enhancement factor, the voltages are generally normalized to the maximum of the residual voltage (umax). Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep TRANSIENT OVERVOLTAGES IN LV POWER INSTALLATIONS 1055 Therefore, the maximum of SPD residual voltage is taken into account as base value in per unit (pu), i.e. umax ¼ 1 pu, see Equation (1). The actual residual voltage of SPD can simply be represented by a trapezoidal waveform [9,15]. The front time is governed by both the incoming voltage waveform and the response time of the SPD. On the other hand, the SPD clips the voltage when the discharge current completely dies and produces a much longer tail time. It is worth mentioning that the peak value of the produced voltages at the apparatus terminals is mainly governed by the SPD residual-voltage front time. Therefore, the influence of the tail time is expected to be much lower than that of the front time. Moreover, the simulation of the SPD residual voltage by Equation (1) gives the opportunity of focusing on very fast transient overvoltages up to 5 ms without losing the computation accuracy. The electromagnetic computations are carried out by the computer code ‘‘CONCEPT’’, which has been developed during the last two decades by the Technical University Hamburg-Harburg [16]. This computer code is based on the so-called method of moments [17] (MoM) and is written in FORTRAN 77. It has been validated using basic arrangements as antenna systems and transmission lines above ideal ground [16]. A comparison between measured and calculated fields in electromagnetic pulse simulators is given in Reference [18]. This computer code solves the Maxwell’s equations in the frequency domain. Therefore, the time-domain solutions are obtained from the inverse Fourier transformation. The fundamental assumptions of the computer code are given in Reference [16] and the handling of the package is described in Reference [19]. In the present simulations with the computer code ‘‘CONCEPT’’ [16], the so-called cylindrical thin wire approach is used, where triangles are employed as expansion functions for the currents and the Dirac delta functions as testing functions (point matching). The whole electrical structures are simulated by cylindrical straight wires subdividing them into segments, where the length of each segment is much longer than its radius. Further, the length of a segment is generally limited to l/8, where l is the wavelength of the highest frequency considered. The segment itself may be ideal conducting or loaded by resistive, inductive, or capacitive elements. The ideal conducting ground is taken into account by the method of electrical images. The upper limit of the computation frequency is chosen as 100 MHz, which corresponds to a wavelength of 3 m, to cover the whole frequency regime when simulating the fast rising SPD residual voltage. The increase in the frequency, however, leads to an increase in the number of segments to fulfill the aforementioned condition (segment length < l/8). Due to this condition, the maximum segment length is limited to 0.34 m. Therefore, the considered highest frequency of 100 MHz is a compromise between the requirements of the computer code and the necessity to limit the computation time and the memory to a suitable size. Three different frequency regimes are chosen in order to minimize the number of frequencies. Starting with a lowest frequency of 5 kHz, the frequency is increased in steps of Df ¼ 10 kHz up to 495 kHz. Then in the second frequency regime, the frequency step is increased to Df ¼ 15 kHz up to 10 MHz. In the highest frequency regime between 10 MHz and 100 MHz, the frequency step is further increased to Df ¼ 20 kHz. 3. ASSUMPTIONS FOR THE LV POWER INSTALLATION The LV power distribution system can be classified into TT, TI, and TN systems based on the earthing of the neutral. The latter includes TN-S, TN-C, and TN-C-S systems. In practice, however, the TT system or the TN system is commonly used. For the TT system, the neutral is earthed only at the distribution transformer secondary, and the protective earth in a building is obtained from a local earth electrode [8,14]. On the other hand, the TN system has its neutral earthed at any available opportunity outside a building, including the distribution transformer secondary, and the service entrance [8,14]. In the present simulation the TN-S system is used, where the neutral (N) and the protective earth (PE) are separated [8], see Figure 1. The LV power supply is simulated by the three-wire TN-S system, which consists of the live conductor (L), the neutral conductor (N), and the protective earth conductor (PE). These cables are made of copper with electrical conductivity of 56.2 106 S m1. The solid insulation between the conductors is disregarded and taken into account as air. The interspacing between L, N, and PE conductor is 0.01 m. Figures 1(a) and 1(b) show the arrangements of the cable routing considering a three-storey building, namely, the ground, the first, and the second floors for the 3-loop and 1-loop arrangements, respectively. From the entrance point at ground level, the cable vertically runs 7 m up to the second floor and then 18.5 m horizontally across this floor. Branches of the cable are at heights of 1 m and 4 m, from where the cable runs 18.5 m across the ground and the first floors, respectively. The ends of the cable are either open or connected to apparatus, where the terminals of the apparatuses are simulated by resistance, inductance, or capacitance. At these locations, the voltages are computed as potential differences between the live and neutral conductors, the neutral and the protective earth conductors, and the live and the protective earth conductors, i.e., VL-N, VN-PE, Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep 1056 I. A. METWALLY AND F. H. HEIDLER 18.5m Loop 3 /// Secon Loop 2 d /// 3m /// First Loop 1 /// /// 3m /// Groun d /// 1m /// 9.5 /// Ideal c onducti ng gro und pla ne 9.5 m m Possible SPD locations. (a) L 1M Apparatus terminals 1M N PE Cable at second floor 3m Cable at first floor 3m L 1M Apparatus terminals 1M N PE L 1M SPD Apparatus terminals PE 1m Cable at ground floor 0. 0 1 Ideal conducting ground plane m 0.0 1 m 1M N 18.5 m (b) Figure 1. Cable routing in the 3-floor LV installation: (a) configuration of the three-loop arrangement, and (b) arrangement and connection of all lines of a single loop with the excitation-voltage source connected between L-line and ground. and VL-PE, respectively. The neutral conductor (N) and the protective earth conductor (PE) are solidly earthed at the boundary of the LPZ to simulate the TN-S system [8]. The voltage source, which simulates the SPD residual voltage, is also placed between L and ground/PE at this location. Of course, it is a simplification that the N-conductor is solidly earthed at the boundary of the LPZ, because the earthing location is normally somewhere in the upstream LPZ 1 or LPZ 0. Nevertheless, this scenario is considered just to analyze the transient response of the LV power systems. The open-circuit termination is taken into account by inserting a high resistance of 1 MV to satisfy the requirements of the CONCEPT computer program. Therefore, the conductors L-PE and N-PE are always terminated by the resistance of 1 MV and the conductors L-N are also terminated by 1 MV in case of open-circuit. If the apparatuses are connected, the terminations are taken into account by impedances located between L and N, see Figure 1(b). 4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4.1. Single loop in a three-storey building 4.1.1. Front time of the SPD residual voltage. The influence of the front time tf of the SPD residual voltage is investigated for the case of open-circuit termination, i.e., without apparatus at the cable ends. Figures 2(a), 2(b), and 2(c) show the waveform of the Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep TRANSIENT OVERVOLTAGES IN LV POWER INSTALLATIONS 1057 3 Voltage, pu 2 1 0 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 4 5 4 5 Time, s (a) tf = 1 s. 3 Voltage, pu 2 1 0 -1 0 1 2 3 Time, s (b) tf = 0.1 s. 3 Voltage, pu 2 1 0 -1 0 1 2 3 Time, s (c) tf = 0.01 s. Figure 2. Influence of the front time tf on the voltage VL-PE in the second floor assuming open-circuit termination at all floors (no apparatus). open-circuit voltage VL-PE in the second floor for front times of 1 ms, 0.1 ms, and 0.01 ms, respectively. The shorter the front time tf, the more pronounced are the oscillations of the open-circuit voltage VL-PE. For the relatively long front time tf ¼ 1 ms, the voltage slightly oscillates with a peak value close to 1 pu. On the contrary, the oscillations are mostly pronounced for tf ¼ 0.01 ms with peak values up to 3 pu. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep 1058 I. A. METWALLY AND F. H. HEIDLER Table I. Voltage peak values in pu for open-circuit termination (no apparatus). Front time tf, ms 1.00 0.30 0.10 0.03 0.01 Ground floor First floor Second floor VN-PE VL-N VL-PE VN-PE VL-N VL-PE VN-PE VL-N VL-PE 0.002 0.007 0.050 0.049 0.050 1.05 1.16 1.93 2.01 2.04 1.06 1.16 1.94 2.01 2.05 0.009 0.017 0.098 0.090 0.093 1.12 1.30 2.21 2.33 2.40 1.12 1.30 2.27 2.36 2.47 0.012 0.020 0.103 0.107 0.100 1.16 1.38 2.51 2.87 2.97 1.17 1.39 2.51 2.86 2.95 Table I summarizes the peak values of all open-circuit voltages, i.e., VL-N, VN-PE, and VL-PE. The peak values of VL-N and VL-PE are more or less identical, while the potential differences between neutral (N) and protective earth (PE), VN-PE, are rather low. The small values of VN-PE are due to the fact that both N and PE are solidly earthed at the cable entrance of the LPZ. The results show that the transient voltages are enhanced between L and PE, and between L and N up to 3 pu. Because the peak value increases with decreasing front time, the smallest considered front time tf ¼ 0.01 ms gives the highest values. The voltage increases when moving up from the ground floor to the second floor. This general trend is also found for both voltages VL-N and VN-PE, see Table I. This behavior may be attributed to the fact that multiple successive reflections come up from the ground and the first floors to the second floor. The circuit in Figure 1(b) is also simulated in EMTP (ATP version using frequency dependent transmission line models) for the case shown in Figure 2(c). Figure 3 shows that the attenuation is a bit higher in the EMTP simulation, but the first peak is very similar. The uncertain point with the EMTP simulations is the vertical part where CONCEPT can handle. In fact, the CONCEPT computer code solves all Maxwell’s equations in the frequency domain. Therefore, all types of couplings between lines are taken into account automatically. Consequently, it can be concluded that CONCEPT seems to simulate the model sufficiently correct. Figure 4 illustrates that the peak value of VL-PE strongly depends on both the floor location and the front time of the SPD residual voltage. During the rise, the voltage wave covers the propagation distance of ctf, where c ¼ 300 m ms1 denotes the speed of light. As long as this propagation distance is much greater than the cable length, the peak value of VL-PE only slightly increases compared to the SPD residual voltage. Therefore, the enhancement factor is close to 1 for tf ¼ 1 ms. On the contrary, the peak value of VL-PE significantly increases, if the propagation distance is in the order of the cable length or even less. Because for tf ¼ 0.01 ms the propagation distance of 3 m is very short, this is the reason why multiple reflections enhance the overvoltages by a factor of about 3. Sometimes the apparatus is connected to the ground by extra bonding wires. Such extra PE connections may exist by service lines as the screens of communication cables. This effect was investigated by extra PE connections from the apparatus to the ground. It was found that the effect is very small for enhancing the overvoltages, i.e., typically in the range of few per cents. Figure 3. EMTP (ATP) simulation result for the case given in Figure 2(c). Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep TRANSIENT OVERVOLTAGES IN LV POWER INSTALLATIONS 1059 Absolute peak voltage, pu 3.0 Second floor First floor Ground floor 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.01 0.10 Front time, s 1.00 Figure 4. Peak value of the voltage VL-PE in the three floors as function of the front time tf for open-circuit termination at all floors (no apparatus). 4.1.2. Resistive impedance of the apparatus terminals. The self and the stray capacitances of the apparatus play an important role in defining the spectrum of the equivalent impedance versus frequency, where resonance may occur at certain frequencies. It is worth mentioning that the frequency-dependence of the load termination resistance is ignored as a first approach of this work. In all simulations the voltages were highest at the second floor, only the voltage at this floor is considered in the following investigation. Figure 5 presents the peak values of the voltage VL-N at the second floor assuming individual consumers with the same resistive load at each floor, i.e., each floor is equipped with an individual consumer where all the consumers have variable but identical resistive loads. Four values of load resistors were used, namely, R ¼ 100 V, 1 kV, 10 kV, and 1 MV. It is obviously seen that the peak value of the voltage VL-N increases with increasing resistive load and/or with decreasing front time tf. For resistive loads greater than about 10 kV, the influence of the consumer becomes negligible. In this case, the consumer acts as the open-circuit termination. 4.1.3. Inductive impedance of the apparatus terminals. Transformers are typically installed at the connection to LV power network. Their inductances are in the range of several 100 mH or even higher. Because these inductances represent high impedances for fast rising surges, the transient response of the network is more or less the same as in case of open-circuit condition. Simulations corroborate this behavior, where significant influence of the inductance is only found for unrealistic low values less than 1 mH. Absolute peak voltage, pu 3.0 2.5 2.0 tf = 0.01 s tf = 0.1 s tf = 1 s 1.5 1.0 1E+2 1E+3 1E+4 1E+5 Loadterminationresistance, 1E+6 Figure 5. Peak value of VL-N at the second floor as function of the load termination resistance considering different front time tf. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep 1060 I. A. METWALLY AND F. H. HEIDLER Absolute peak voltage, pu 3.5 Second floor First floor Ground floor 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1E-4 1E-3 1E-2 Loadterminationinductance,H 1E-1 Figure 6. Effect of load termination inductance on VL-N of loop 2 alone for all floors at tf ¼ 0.01 ms. Nevertheless, the following simulation is presented just to complete the study and to show the influence of such low inductive loads. In this part, the load inductance L is varied from 100 mH to 100 mH. The dependence of the voltage waveforms of VL-PE of the second floor for L ¼ 100 mH for front times of 1 ms, 0.1 ms, and 0.01 ms similar and in accordance with the reasoning of Figure 2. Figure 6 illustrates the effect of load termination inductance on VL-N of loop 2 alone (see Figure 1(b)) and for all floors at tf ¼ 0.01 ms. Before the occurrence of the resonance condition, there is roughly a linear increase in VL-N for all floors up to L ¼ 500 mH, where the top floor loop-termination voltage is the highest. For further increase in L after the resonance condition, i.e., L > 500 mH, VL-N slightly decreases then it roughly stays constant. This is attributed to the fact that the SPD residual voltage (unitstep voltage with linear-rising front up to tf ¼ 0.01 ms then stays constant at 1 pu) has very high frequency content in the range of MHz, hence the corresponding inductive reactance for L ¼ 100 mH and 100mH is in the range of kV and MV, respectively. Except at the resonance condition, the trend of these results is similar to those shown in Figure 5 for resistive loop termination. 4.1.4. Capacitive impedance of the apparatus terminals. On the other hand, in the most cases the transformers do not act as pure inductances with respect to fast transient surges. The capacitive coupling, i.e., inter-turn capacitance and capacitance to ground ‘‘core and tank’’, involves a capacitive behavior. The variety of such capacitances is taken into account. Figures 7(a), and 7(b) illustrate the waveforms of the voltage VL-N at the apparatus terminals of the second floor for C ¼ 10 pF and 1000 pF, respectively. The SPD residual voltage is considered with tf ¼ 0.01 ms and each floor is equipped with an apparatus having the same capacitance. The small value of C ¼ 10 pF is comparable to the case of open-circuit, while the higher capacitance C ¼ 1000pF lowers the voltage peak value to about 2.2 pu, see Figure 7(b). The lower frequency of oscillation shown in Figure 7(b) is due to the fact that the insertion of the capacitance lowers the resonance frequency in combination with the cable installation. Figure 8 illustrates the effect of load termination capacitance on VL-N of loop 2 alone (see Figure 1(b)) for all floors at tf ¼ 0.01 ms. For this case, the length of all sub-loops is larger than the propagation distance during the SPD voltage rising, hence the multiple successive reflections dominate and give a peak value of VL-N ¼ 2.13 pu, 2.54 pu, and 3.14 pu for the ground, first, and second floors, respectively. The trend of the results shown in Figure 8 is opposite to those shown in Figures 5 and 6, because as the frequency increases the inductive impedance increases, contrary to the capacitive one. 4.2. Three loops in a three-storey building Figure 9 illustrates the voltage waveforms of VL-N for the second floor using three open-circuited loops (R ¼ 1 MV) at tf ¼ 0.01 ms with excitation at the middle loop 2. Comparing the voltage waveform in Figures 9(a) and 9(b), it can be seen that loops 1 and 3 (Figure 9(a)) have the same oscillating voltage waveform, while the amplitude and frequency of the oscillations is higher for loop 2 (Figure 9(b)). This is attributed to the fact that loops 1 and 3 have longer cable lengths and therefore higher inductances than loop 2. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep 1061 TRANSIENT OVERVOLTAGES IN LV POWER INSTALLATIONS 4 Voltage, pu 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 0 1 2 3 4 5 3 4 5 Time, s (a) C = 10pF. 4 Voltage, pu 3 2 1 0 -1 0 1 2 Time, s (b) C = 1000pF. Figure 7. Voltage waveforms of VL-N at the apparatus terminals of the second floor considering the front time tf ¼ 0.01 ms: (a) C ¼ 10 pF or (b) C ¼ 1000 pF. 3.5 Absolute peak voltage, pu Second floor First floor Ground floor 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1E-11 1E-10 1E-9 Loadterminationcapacitance,F 1E-8 Figure 8. Effect of load termination capacitance on VL-N of loop 2 alone for all floors at tf ¼ 0.01 ms. Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep 1062 I. A. METWALLY AND F. H. HEIDLER 3.0 2.5 Voltage, pu 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 0 1 2 3 4 5 Time, s (a) Loop 1 or 3. 3.0 2.5 Voltage, pu 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 0 1 2 3 4 5 Time, s (b) Loop 2. Figure 9. Voltage waveforms of VL-N for the second floor using three open-circuited loops at tf ¼ 0.01 ms with excitation at loop 2 (no apparatus). Generally for the three-loop case with excitation of loop 2 (see Figure 1(a)), the loop-termination voltages of all loops in all floors are less than those when using loop 2 alone. The symmetry of the arrangement of these three loops makes the loop-termination voltages of loops 1 and 3 are exactly equal. This confirms the accuracy of the computation method. In addition, the loop-termination voltages of the outer loops (loops 1 and 3) are lower than those for the middle loop by 11%, especially at very fast rising tf ¼ 0.01 ms. The trend of these results is in accordance with the reasoning of Figure 4. Figure 10 illustrates the influence of the SPD location on the voltage VL-PE of the second floor assuming at tf ¼ 0.01 ms and the two cases of current injection at the middle loop 2 and at the outer loop 1, respectively, see Figure 1(a). It can be seen that the unsymmetrical arrangement for the case of current injection at the outer loop 1 gives the highest VL-PE at the second floor. In the other case, the symmetrical arrangement (injection at the middle loop 2) gives identical values of VL-PE of the outer loops (loop 1 and 3) with the highest value of VL-PE at the middle loop 2, i.e., 2.9 pu. The latter value is 2.6 pu, i.e., it is lower than that for the case of loop 1 injection by 0.3 pu. The induced voltages VL-N and VL-PE are roughly equal. These examples also show for the 3-loop arrangement that the maximum enhancement factor of 3 should be considered. 4.3. Single loop in a six-storey building For the 3-floor installations the calculations reveal that the overvoltages increase when moving up from the ground floor to the top floor. This behavior is checked for a higher 6-storey building. The cable routings in the ground, the first, and the second floors are the same as in the 3-floor installations, see Figure 1(b). For the third, the fourth, and the fifth floors, the LV power installations are doubled, where the doubled structure is placed on the top of the original 3-floor installation. From the second floor, the vertical cable Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep TRANSIENT OVERVOLTAGES IN LV POWER INSTALLATIONS 1063 3.5 Absolute peak voltage, pu Injection in loop 1 Injection in loop 2 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 Loop 1 Loop 2 Loop 3 Figure 10. Comparison between VL-PE of the second floor for the middle and the corner injection cases at tf ¼ 0.01 ms (no apparatus). is extended by 9 m and horizontal cables are installed at heights of 10 m, 13 m, and 16 m. Like in the original installation, these horizontal cables run 18.5 m across the individual floors. For the 3-floor and the 6-floor installations, there is a common trend, where the open-circuit voltage increases when moving up from a lower floor to a higher one. Therefore, the highest voltages are always at the top floors. Considering the SPD residual voltage with the front time tf ¼ 0.01 ms, the peak value is enhanced up to the factor of about 3 at the top floors irrespective of the number of floors. This is attributed to the dominated successive reflections. For the longer front time tf ¼ 0.1 ms, the enhancement factor is close to 3 only in case of the 6-floor installations, while it is somewhat reduced to about 2.5 for the 3-floor installations. The higher enhancement factor of the 6-floor installations may be due to the fact that the effective cable length is greater in the 6-floor installation compared to that for the 3-floor one. 5. CONCLUSIONS The transient behavior of LV power installations is analyzed by considering the TN-S system with different cable routings in threeand six-storey buildings. All cables consist of the live conductor (L), the neutral conductor (N), and the protective earth conductor (PE). The apparatus terminals are simulated by resistances, inductances, or capacitances. At these locations, the voltage drops are computed as potential differences between the live and the neutral conductors, the neutral and the protective earth conductors, and the live and the protective earth conductors, i.e., VL-N, VN-PE, and VL-PE, respectively. The SPD is located between the live conductor L and ground/PE at the entrance of the cable into the LPZ. The SPD residual voltage is simulated by a step voltage with a linearrising front up to the peak value. The front time of the SPD residual voltage tf is considered with values ranging from 0.01 ms to 1 ms. For the 3-floor and the 6-floor installations, there is a common trend that the overvoltage increases when moving up from a lower floor to a higher one. Therefore, the highest overvoltages always occur in the top floor of the installations. At this floor, the maximum enhancement factor is 3 for the voltage between L and PE, VL-PE, as well as for the voltage between L and N, VL-N. This enhancement factor is found for the case of open-circuit condition, and also for apparatus having moderate terminal impedance down to 10 kV irrespective of the number of floors and loops, especially for high resistive and inductive, and low capacitive loads. Therefore, the enhancement factor of 2 given in Annex D of the IEC 62305-4 standard should be increased to 3. 6. LIST OF SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS C c f L L capacitance at the apparatus terminal, F speed of light, m/s frequency, Hz line (live) wire inductance at the apparatus terminal, H Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep 1064 LEMP LPL LPMS LPS LPZ LV MoM MOV N pu PE R SPD tf u umax VL-N VL-PE VN-PE Df l I. A. METWALLY AND F. H. HEIDLER lightning electromagnetic impulse lightning protection level LEMP protection measures system lightning protection system lightning protection zone low voltage Method of Moments metal-oxide varistor neutral wire per unit protective earth resistance at the apparatus terminal, V surge protective device front time of the SPD residual voltage, s SPD residual voltage, V maximum of SPD residual voltage, V potential difference between L and N, V potential difference between L and PE, V potential difference between N and PE, V frequency step, Hz wavelength, m REFERENCES 1. Paul D. Low-voltage power system surge overvoltage protection. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2001; 37(1):223–229. 2. Protection Against Lightning—Part 4: Electrical and Electronic Systems within Structures. IEC 62305-4 Standard, Ed. 1, 2006-01, 2006. 3. Silfverskiold S, Thottappillil R, Ye M, Cooray V, Scuka V. Induced voltages in a low-voltage power installation network due to lightning electromagnetic fields: an experimental study. IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility 1999; 41(3):265–271. 4. Protection Against Lightning—Part 1: General Principles. IEC 62305-1 Standard, Ed. 1, 2006-01, 2006. 5. Protection Against Lightning—Part 3: Physical Damage to Structures and Life Hazard. IEC 62305-3 Standard, Ed. 1, 2006-01, 2006. 6. Surge Protective Devices Connected to Low-Voltage Power Systems—Part 11: Requirements and Tests. IEC 61643-11, Ed.1, 2002. 7. Loncar B, Osmokrovic P, Stankovic S. Temperature stability of components for overvoltage protection of low-voltage systems. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2002; 30(5):1881–1885. 8. Hasse P. Overvoltage Protection of Low-Voltage Ssystems, IEE Power and Energy Series No. 33, 2nd edn. The Institution of Electrical Engineers: London, 2000. 9. Beutel A, Van Coller J. The application of silicon avalanche diodes on low-voltage power systems. IEEE Transaction on Industry Applications 2005; 41(4):1107– 1112. 10. D’Elia B, Dell’Aquila G, Di Gregorio G, et al. Selection of SPD Characteristics to Reduce the Risk due to Lightning Overvoltages, Proceedings of 26th International Conference on Lightning Protection (ICLP’ 2002), Krakow, Poland, September 2–6, 2002; 539–543. 11. He J, Yuan Z, Xu J, Chen S, Zou J, Zeng R. Evaluation of the effective protection distance of low-voltage SPD to equipment. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2005; 20(1):123–130. 12. Amicucci GL, Fiamingo F, Marzinotto M, Mazzetti C, Lo Piparo GB, Flisowski Z. Protection Against Lightning Overvoltages of Electrical and Electronic Systems: Evaluation of the Protection Distance of an SPD, Proceedings of 27th International Conference on Lightning Protection (ICLP’ 2004), Avignon, France, September 13–16, 2004; 1073–1078. 13. Galvan A, Cooray V, Thottappillil A. A technique for the evaluation of lightning-induced voltages in complex low-voltage power-installation networks. IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility 2001; 43(3):402–409. 14. Mansoor A, Martzloff F. The effect of neutral earthing practices on lightning current dispersion in a low-voltage installation. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 1998; 16(3):783–792. 15. Metwally IA, Gastli A, Al-Sheikh M. Withstand capability tests of transient voltage surge suppressors. Journal of Electric Power Systems Research (JEPSR) 2007; 77(7):859–864. 16. Brüns H-D, Singer H, Leone M. Application of the Method of Moments (MoM) to a Challenging Real-World EMC Problem, Invited paper for IEEE Symposium on EMC, Seattle, USA, 1999; 684–689. 17. Harrington RF. Field Calculations by Moment Methods. The MacMillan Company: New York, 1968. 18. Brüns H-D, Koenigstein D. Calculation and measurements of Transient Electromagnetic Fields in EMP Simulators, Proceedings of 6th Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Zurich, Switzerland, Paper 66L2, 1985; 365–370. 19. Singer H, Bruens H-D, Mader T, Freiberg A. CONCEPT II—Programmer Handbook. University Hamburg-Harburg: Germany, 1994 (in German). Copyright # 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Euro. Trans. Electr. Power 2009; 19:1053–1064 DOI: 10.1002/etep