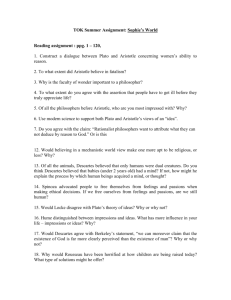

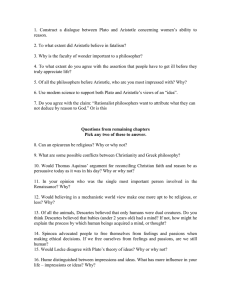

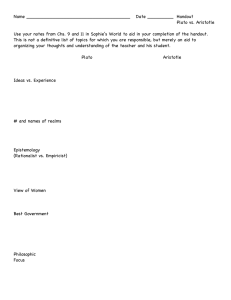

Exam #1 Review Sheet (Metaphysics) Chapter 3 (The Presocratics): 11 questions What was the problem of the One and the Many? 1. What is the ultimate reality that underlies all things? (the One) 2. How is everything else (the Many) related to it? What was the basic "stuff" of reality according to each Presocratic philosopher studied? 1. Thales: Water 2. Anaximander: basic substance must be more elementary than water. Called it the apeiron 3. Anaximenes: Air 4. Heraclitus: Fire Reason or Logos was a crucial concept for which philosopher? Heraclitus Who believed that permanence was an illusion? Who believed that change was the illusion? Heraclitus: permanence Parmenides: change Nous was a crucial concept for which of the Presocratics? Who praised him for his claim that it was the source of all order in the universe? Mind (Anaxagoras) / Who proposed the first theory of evolution? Anaximander: a proto-evolutionist. What was Parmenides' understanding of reality? Parmenides conceives reality as a material, motionless, infinitely extended and fully occupied plenum Who was the first to distinguish between appearance and reality? Which subsequent, extremely influential, philosopher did he influence by means of this distinction? Parmenides. Zeno Chapter 4 (Plato and Aristotle): 15 questions To which philosophers was Plato responding when he proposed his theory of Forms? The Sophists (of Socrates): Protagoras, Gorgias, Thrasymachus Why is reality unknowable if Heraclitus is right? Heraclitus’ teaching that “All things are in flux” denied that there is such a thing as substance persisting throughout change. But if nothing ever remains the same, then knowledge is again impossible. In the case of the Sophists, there was no objective reality to be known; in this case there is an objective reality, but it is never the same. In either case, reality can’t be known. Why is reality unknowable if Protagoras is right? While people may differ about the nature of reality, their differing views nevertheless derive from the same objective reality that exists independently of their conceptions. It exerts a controlling influence on them, otherwise knowledge is not possible What famous statement characterizes Protagoras's position? What is that position called? “Man is the measure of all things.” RELATIVISM What is the highest of Plato's Forms? What, in Plato, best corresponds to our concept of God? The form of the Good. As the ultimate principle of reality and truth, the Form of the Good is the closest thing in Plato to our conception of God. The Good is beyond understanding and, as the source of all reality, is even beyond being as we know it. It is from the Good that all the forms, and all of reality, descends What is Plato's basic view of reality? Reality is actually more complex than two tiers, for Plato. While there are two basic parts to it, being and becoming, there are subdivisions within the parts. It is better, therefore, to think of reality as a continuum, ranging from the least real (the realm of mere images) to the most real (the highest of the forms) According to Plato, how do the Forms cause things to be what they are? By imitation: Things in this realm of becoming “try to be like” their forms, but enjoy only limited success (there is no absolutely beautiful thing, no perfect exemplar of anything). Plato uses the language of moral effort — everything is striving to be what it is intended to be, in accordance with the form that defines its nature — and he uses this moral language even of nonmoral agents (circles, horses, etc.). By participation: Things in the realm of becoming participate in their forms, deriving their specific natures from them. Participation in more than one form is also possible (e.g., the apple not only participates in the form of “appleness,” but also in the forms of “sweetness,” “roundness,” “crispness,” “organic life” and so forth). Plato therefore conceives of a blending of forms in objects. He furthermore recognized that there are certain accidental qualities in things, i.e., qualities that are not part of their essence. These are forms in which individuals participate on their own (and it is participation in these forms that accounts for the differences among individuals of the same class). How does Aristotle's view of the Forms differ from Plato's? Plato, of course, denies that the Forms cause movement or change in sensible things. Aristotle, however, observes that because of their separation from things, neither can they contribute to their being. He writes: “It would seem impossible that the substance and that of which it is the substance should exist apart; how therefore, could the Ideas, being the substances of things, exist apart?” And again: Plato’s Forms “are not in the particulars which share in them.” What is Aristotle's view of the relationship between form and matter called? Form and matter don’t exist apart from each other. They are always joined in a hylomorphic composition (from hyle, meaning “wood” or “matter,” and morphe, which means “form” or “shape”). What is meant by teleology? In whose metaphysic is it a key concept? Where Plato regarded the Forms as eternal and unchanging, Aristotle believes that they possess a tendency to develop toward an end, or telos Matter and form thus conceived, however, do not provide a full account of things. Living things are not static, as Plato conceives their forms to be. They develop and their forms are different from one stage to the next (Cf. the acorn and the oak, the zygote and the fully developed human). Any correct view of form must take into account its dynamism and teleological character (telos = “end”) — i.e., its natural tendency to develop toward a specific end. Plato What are the Four Causes? 1. MATERIAL 2. FORMAL 3. EFFICIENT 4. FINAL What is metaphysical realism? Name four realists. Universals are non-mental and mind-independent (they would exist even if there were no minds to be aware of them). A mindless world would not lack universals, but only the awareness of them. Plato, Aristotle, Augustine Aquinas What is nominalism? Name its founder. In the Middle Ages, William of Ockham founded a school called nominalism (from the Latin, nomen). It held that forms, or universals, do not exist, but are mere names by which we group together things with similar features. Which Christian thinker followed Plato's philosophy? Which followed Aristotle's? Augustine (d. 430) carried on the tradition of Plato Aquinas (d. 1275) that of Aristotle. Chapter 5 (Descartes): 9 questions What is the difference between deduction and induction? intuition (which delivers basic, indubitable truths) deduction (by which still further truths can be derived, all with logical necessity). Which was Descartes' favored type of reasoning? Why? After doubting everything, what was the first result at which he arrived? Descartes’ first result,“Cogito, ergo sum”: Still, there was one thing he could not doubt: that he was doubting, or that he was being deceived. Something was engaged in affirming, denying, doubting and imagining – in short, in thinking – hence Descartes arrived at the foundation upon which he could build the edifice of knowledge: “I think, therefore I am.” By which mental operation did he arrive at it? This result was the product of intuition (direct experience, unmediated by the senses). It possessed the certainty of the premises of logic and mathematics, the earmarks of which were clarity and distinctness. What was his next result? The eidological proof (from åÃäïò, idea): This argument shows that God must exist in order to account for Descartes’ idea of perfection. It is a causal argument similar to those that trace the world’s existence back to God, only here, it is Descartes’ idea of perfection that is said to have God as its cause. By which mental operation did he achieve it? deduction Name Descarte's two types of proof for God's existence. What is the basic idea behind each? A. The eidological proof (from åÃäïò, idea): This argument shows that God must exist in order to account for Descartes’ idea of perfection. It is a causal argument similar to those that trace the world’s existence back to God, only here, it is Descartes’ idea of perfection that is said to have God as its cause. 1. Descartes has an idea of a being more perfect than himself – for he doubts, and it is a greater perfection to know. 2. This idea could not have come from nothing, nor from himself since the more perfect cannot come from the less perfect. 3. Therefore, it derives from a being more perfect than Descartes – one “which even had within itself all the perfections of which I could form any idea.” B. The ontological proof: Here, God’s existence is shown to be a logical consequence of the idea of “perfection” (in the previous argument it was that idea’s cause). 1. Descartes has the idea of a being that possesses the sum of all perfections. 2. Existence is a perfection (a being that exists is greater than one that is merely thought). 3. Therefore God exists. How does Descartes, at length, arrive at certitude that the world exists? The stages by which Descartes’ “certain” results unfold are: first, truths about himself, second, about God and third, about the world. In Descartes we encounter what has been called the subjective turn in philosophy since knowledge of the world begins with knowledge of ourselves and our ideas. What is his solution to the mind-body problem? What is Malebranches? Leibniz's? Spinoza's? Describe how each philosopher's position "solves" the problem. Descartes’ answer: Interactionism. Mind and brain do interact, the one causing changes of state in the other. Descartes hypothesized that mind and brain intermingled in the pineal gland. 1. Occasionalism: On the occasion of bodily stimuli, God creates the appropriate idea or response in the mind, and vice versa (Malebranche, 1638-1715). 2. Preestablished harmony: Bodily states have been preordained by God to correspond with appropriate mental states, like synchronized clocks (Leibniz, 1646-1716). 3. Double-aspect theory: There is only one substance, unknown to us except through its attributes of mind and matter. (Spinoza, 1632-77) Chapter 6 (Locke and Berkeley): 10 questions What is the difference between "subjective" and "objective" idealism? Which type of idealist was Plato? Which type was Berkeley? A. Objective Idealism holds that ideas can exist independently of being perceived (Plato’s view). B. Subjective Idealism holds that all things would cease to exist if all perceivers did (Berkeley’s view). This chapter has to do with subjective idealis What is "substance," as Descartes, Locke, and Berkeley all understand it? This was conceived as an underlying something that upholds the physical qualities of sensible things ( such as size, shape, color, position, sound, and movement), and something that likewise underlies and upholds intellectual activities ( such as thinking, willing, denying, and doubting). In the first case something is matter, and in the second case it is mind. mind-matter dualist Give the reasons why Berkeley denies that material substances exist. 1. Discontinuity of dualism 2. Matter as a meaningless idea 3. Unexperienced as inconceivable 4. Inseparability of primary and secondary qualities 5. Relativity of all qualities Do any of these reasons (unbeknownst to him) also apply to mental substance? Explain Locke's distinction between "primary" and "secondary" properties. Which inheres in the material object, and which in the mind? Distinguished between primary & secondary qualities. “Primary” (size, position, shape, movement) exist independently of a perceiver. “Secondary” (color, sound, texture, taste) exist only in the perceiver’s mind and would altogether cease to exist if no perceiver were present. What phrase serves at the motto for Berkeley's position? BERKELEY’S VIEW: Esse est aut percipi aut percipere – “To be is either to be perceived or to perceive” (often shortened to Esse est percipi – “To be is to be perceived”). What is solipsism? Was Berkeley a solipsist? A. Solipsism is the belief that everything that exists does so only in the solipsist’s mind, he being the sole reality. (“Solipsim” is from the Lat. solus, “alone, only” and ipse, “itself”) B. Berkeley not a solipsist: Like realists, he acknowledged the objective existence of things outside his own mind, taking the passivity of perception as sufficient proof that we do not manufacture our own perceptions. Their source lies outside us. Did Berkeley think there was a relationship between belief in matter and disbelief in God? Does his refutation of matter have any impact on the question of God's existence? The self-subsistence of matter has always been the bulwark of atheism. But if there is no such thing as matter, then things continue in existence only insofar as God – not some material substratum – continuously upholds them. Does Berkeley deny the reality of things, or only their materiality? only their materiality