Faculty of Electronics and Telecommunications

INSTITUTE OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS

RAE411 Telecommunications Software

Tianhua Chen

2022/10/21

1

Basic Concepts of Graphs and Related Terms

▪ Graph is a non linear data structure; A map is a well-known example of a graph. In a map various

connections are made between the cities. The cities are connected via roads, railway lines and

aerial network. We can assume that the graph is the interconnection of cities by roads. Euler used

graph theory to solve Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem. Is there a possible way to traverse

every bridge exactly once – Euler Tour

2

A graph contains a set of points known as nodes (or vertices) and set of links known as edges (or Arcs) which

connects the vertices.

Graph Terminology

1. Vertex : An individual data element of a graph is called as Vertex. Vertex is also known as node. In above

example graph, A, B, C, D & E are known as vertices.

3

2. Edge : An edge is a connecting link between two vertices. Edge is also known as Arc. An edge is represented as

(starting Vertex, ending Vertex).

In above graph, the link between vertices A and B is represented as (A,B).

Riga Technical University

▪ Edges are three types:

▪ 1. Undirected Edge - An undirected edge is a bidirectional edge. If there is an undirected edge

between vertices A and B then edge (A , B) is equal to edge (B , A).

▪ 2. Directed Edge - A directed edge is a unidirectional edge. If there is a directed edge between

vertices A and B then edge (A , B) is not equal to edge (B , A).

▪ 3. Weighted Edge - A weighted edge is an edge with cost on it. Edges can be weighted; for example,

"distance," "travel time," and "fare" between two stops in a transit network can all be used as

weights.

4

Types of Graphs

1. Undirected Graph

A graph with only undirected edges is said to be undirected graph.

2. Directed Graph

A graph with only directed edges is said to be directed graph.

Riga Technical University

5

3. Complete Graph

A graph in which any V node is adjacent to all other nodes present in the graph is known as a complete graph. An

undirected graph contains the edges that are equal to edges = n(n-1)/2 where n is the number of vertices present

in the graph. The following figure shows a complete graph.

6

4. Regular Graph

Regular graph is the graph in which nodes are adjacent to each other, i.e., each node is accessible from any

other node.

Riga Technical University

7

5. Cycle Graph

A graph having cycle is called cycle graph. In this case the first and last nodes are the same. A closed simple

path is a cycle.

6. Acyclic Graph

A graph without cycle is called acyclic graphs.

Riga Technical University

7. Weighted Graph

A graph is said to be weighted if there are some non negative value assigned to each edges of the graph.

The value is equal to the length between two vertices. Weighted graph is also called a network.

Riga Technical University

8

9

Outgoing Edge

A directed edge is said to be outgoing edge on its origin vertex.

Incoming Edge

A directed edge is said to be incoming edge on its destination vertex.

Degree

Total number of edges connected to a vertex is said to be degree of that vertex.

Indegree

Total number of incoming edges connected to a vertex is said to be indegree of that vertex.

Outdegree

Total number of outgoing edges connected to a vertex is said to be outdegree of that vertex.

Parallel edges or Multiple edges

If there are two undirected edges to have the same end vertices, and for two directed edges to have the same

origin and the same destination. Such edges are called parallel edges or multiple edges.

Self-loop

An edge (undirected or directed) is a self-loop if its two endpoints coincide.

Simple Graph

A graph is said to be simple if there are no parallel and self-loop edges.

Adjacent nodes

When there is an edge from one node to another then these nodes are called adjacent nodes.

Incidence

In an undirected graph the edge between v1 and v2 is incident on node v1 and v2.

Riga Technical University

Walk

A walk is defined as a finite alternating sequence of vertices and edges, beginning and ending with

vertices, such that each edge is incident with the vertices preceding and following it.

Closed walk

A walk which is to begin and end at the same vertex is called close walk. Otherwise it is an open walk.

If e1,e2,e3,and e4 be the edges of pair of vertices (v1,v2),(v2,v4),(v4,v3) and (v3,v1) respectively ,then v1

e1 v2 e2 v4 e3 v3 e4 v1 be its closed walk or circuit.

Path

A open walk in which no vertex appears more than once is called a path.

10

If e1 and e2 be the two edges between the pair of vertices (v1,v3) and (v1,v2) respectively, then v3 e1 v1 e2

v2 be its path.

Riga Technical University

Length of a path

The number of edges in a path is called the length of that path. In the following, the length of the path is 3.

11

Circuit

A closed walk in which no vertex (except the initial and the final vertex) appears more than once is called a

circuit.

A circuit having three vertices and three edges.

Riga Technical University

Routing and Forwarding

Forwarding versus Routing

– Forwarding:

– to select an output port based on destination address and routing table

– Routing:

– process by which routing table is built

▪ Routing is not the same as Forwarding

▪ Routing is the building of maps

– Each routing protocol usually has its own routing database

– Routing protocols populate the forwarding table

▪ Forwarding is passing the packet to the next hop device

– Forwarding table contains the best path to the next hop for each prefix

– There is only ONE forwarding table

12

Routing

Forwarding versus Routing

– Forwarding:

– to select an output port based on destination address and routing table

– Routing:

– process by which routing table is built

13

Routing

Forwarding versus Routing

– Forwarding:

– to select an output port based on destination address and routing table

– Routing:

– process by which routing table is built

14

Routing

• Forwarding table VS Routing table

• Forwarding table

• Used when a packet is being forwarded and so must contain enough information to

accomplish the forwarding function

• A row in the forwarding table contains the mapping from a network number to an outgoing

interface and some MAC information, such as Ethernet Address of the next hop.

• Routing table

• Built by the routing algorithm as a precursor to build the forwarding table

• Generally contains mapping from network numbers to next hops

15

Routing

Example rows from (a) routing and (b) forwarding tables

16

Routing

Network as a Graph

The basic problem of routing is to find the lowest-cost path between any two nodes

Where the cost of a path equals the sum of the costs of all the edges that make up the path

Undirected Graph

Cycle Graph

Sub Graph

Connected Graph

Routers are used as vertices, and network connections between routers are used as edge weights, which

can include factors such as the speed of network connections, network load levels, and priority by time

periods. As an abstraction, we combine all influencing factors into a single weight.

17

Routing

• For a simple network, we can calculate all shortest paths and load them into some nonvolatile

storage on each node.

• Such a static approach has several shortcomings

• It does not deal with node or link failures

• It does not consider the addition of new nodes or links

• It implies that edge costs cannot change

• What is the solution?

• Need a distributed and dynamic protocol

• Two main classes of protocols

• Distance Vector

• Link State

18

Distance Vector

▪ Each node constructs a one dimensional array (a vector) containing the “distances” (costs) to all

other nodes and distributes that vector to its immediate neighbors

▪ Starting assumption is that each node knows the cost of the link to each of its directly connected

neighbors

19

Distance Vector

Initial distances stored at each node (global view)

20

Distance Vector

Initial routing table at node A

21

Distance Vector

Final routing table at node A

22

Distance Vector

A to G:

A, B, C, D, G (cost: 4)

A, C, D, G (cost: 3)

A, F, G (cost: 2)

Final distances stored at each node (global view)

23

Distance Vector

▪ The distance vector routing algorithm is sometimes called as Bellman-Ford algorithm

▪ Every T seconds each router sends its table to its neighbor each router then updates its table

based on the new information

▪ Problems include fast response to good new and slow response to bad news. Also too many

messages to update

24

Distance Vector

• When a node detects a link failure

▪ F detects that link to G has failed

▪ F sets distance to G to infinity and sends update to A

▪ A sets distance to G to infinity since it uses F to reach G

▪ A receives periodic update from C with 2-hop path to G

▪ A sets distance to G to 3 and sends update to F

F decides it can reach G in 4 hops via A

▪

25

Distance Vector

▪ Slightly different circumstances can prevent the network from stabilizing

– Suppose the link from A to E goes down

– In the next round of updates, A advertises a distance of infinity to E, but B and C advertise a

distance of 2 to E

– Depending on the exact timing of events, the following might happen

▪ Node B, upon hearing that E can be reached in 2 hops from C, concludes that it can reach

E in 3 hops and advertises this to A

▪ Node A concludes that it can reach E in 4 hops and advertises this to C

▪ Node C concludes that it can reach E in 5 hops; and so on.

▪ This cycle stops only when the distances reach some number that is large enough to be

considered infinite

Count-to-infinity problem

–

26

Count-to-infinity Problem

▪ Use some relatively small number as an approximation of infinity

▪ For example, the maximum number of hops to get across a certain network is never going to be

more than 16

▪ One technique to improve the time to stabilize routing is called split horizon

– When a node sends a routing update to its neighbors, it does not send those routes it learned

from each neighbor back to that neighbor

– For example, if B has the route (E, 2, A) in its table, then it knows it must have learned this

route from A, and so whenever B sends a routing update to A, it does not include the route (E,

2) in that update

27

Count-to-infinity Problem

▪ In a stronger version of split horizon, called split horizon with poison reverse

– B actually sends that back route to A, but it puts negative information in the route to ensure

that A will not eventually use B to get to E

– For example, B sends the route (E, ∞) to A

28

Example

F to C:

FABC = 6+3+4=13

FEBC = 2+1+4=7

FEDC = 2+1+9=12

FAEBC = 6+1+1+4 = 12

FAEDC = 6+1+1+9=17

FEABC = 2+1+3+4=10

FABEDC = 6+3+1+1+9=20

Riga Technical University

How to find the distance vector router table for all nodes?

29

Routing Information Protocol (RIP)

Example Network running RIP

Rather than advertising the cost of reaching other routers,

the routers advertise the cost of reaching networks.

Router C would advertise to router A the fact it can reach

1, network 2 and 3 cost 0

2, network 5 and 6 cost 1

3, network 4 at cost 2

RIPv2 Packet Format

30

Link State Routing

Strategy: Send to all nodes (not just neighbors) information about directly connected links (not entire

routing table).

▪ Link State Packet (LSP)

– id of the node that created the LSP

– cost of link to each directly connected neighbor

– sequence number (SEQNO)

– time-to-live (TTL) for this packet

▪ Reliable Flooding

– store most recent LSP from each node

– forward LSP to all nodes but one that sent it

– generate new LSP periodically; increment SEQNO

– start SEQNO at 0 when reboot

– decrement TTL of each stored LSP; discard when TTL=0

31

Link State

Reliable Flooding

Flooding of link-state packets. (a) LSP arrives at node X; (b) X floods LSP to A and C; (c) A and C

flood LSP to B (but not X); (d) flooding is complete

32

Dijkstra’s Shortest-Path Algorithm

▪ Iterative algorithm

– After k iterations, know least-cost path to k nodes

▪ S: nodes whose least-cost path definitively known

– Initially, S = {u} where u is the source node

– Add one node to S in each iteration

▪ D(v): current cost of path from source to node v

– Initially, D(v) = c(u,v) for all nodes v adjacent to u

– … and D(v) = ∞ for all other nodes v

– Continually update D(v) as shorter paths are learned

33

33

Dijsktra’s Algorithm

34

1 Initialization:

S: Least cost path known

2 S = {u}

3 for all nodes v

D(v): Known shortest cost from

4

if (v is adjacent to u)

source to v

5

D(v) = c(u,v)

6

else D(v) = ∞

C(w,v): Known cost from w to v

7

8 Loop: Do

9 find w not in S with the smallest D(w)

10 add w to S

11 update D(v) for all v adjacent to w and not in S:

12

D(v) = min{D(v), D(w) + c(w,v)}

13 until all nodes in S

34

1

1

2

5

4

3

Dijkstra’s Algorithm Example

3

2

4

1

35

35

2

Dijkstra’s Algorithm Example

Loop: Do

4

1 D(w)

3 not in S 1with the smallest

find w

add w to S

2

5

forall v adj to1 w && not in S:

1

2

5

3

4

3

1

D(v) = min{ D(v), D(w) + c(w,v) }

1

4 in S

until all nodes

3

2

4

3

2

3

2

1

4

1

4

1

1

2

2

5

5

36

4

3

4

3

1

1

36

1

4

1

1

1

2

2

5

5

4

3

4

3

Dijkstra’s Algorithm Example

3

2

3

2

4

1

1

3

2

3

2

1

4

1

4

1

1

2

2

5

5

37

4

3

4

3

1

1

37

u

3

2

v

w

1

4

1

2

x

s

5

4

3

y

t

1

• Shortest-path tree from u

Shortest-Path Tree

38

z

(u,v)

(u,w)

(u,w)

(u,v)

(u,v)

(u,w)

(u,w)

link

• Forwarding table at u

v

w

x

y

z

s

t

38

u

39

3

2

v

w

1

Fig. 1

1

4

2

x

Fig. 3

5

s

4

3

y

t

1

z

Fig. 5

Fig. 2

Fig. 4

39

Shortest Path Routing

▪ In practice, each switch computes its routing table directly from the LSP’s it has collected using a

realization of Dijkstra’s algorithm called the forward search algorithm

▪ Specifically each switch maintains two lists, known as Tentative and Confirmed

▪ Each of these lists contains a set of entries of the form (Destination, Cost, NextHop)

40

Shortest Path Routing

▪ The algorithm

– Initialize the Confirmed list with an entry for myself; this entry has a cost of 0

– For the node just added to the Confirmed list in the previous step, call it node Next, select its

LSP

– For each neighbor (Neighbor) of Next, calculate the cost (Cost) to reach this Neighbor as the

sum of the cost from myself to Next and from Next to Neighbor

▪ If Neighbor is currently on neither the Confirmed nor the Tentative list, then add

(Neighbor, Cost, Nexthop) to the Tentative list, where Nexthop is the direction I go to

reach Next

▪ If Neighbor is currently on the Tentative list, and the Cost is less than the currently listed

cost for the Neighbor, then replace the current entry with (Neighbor, Cost, Nexthop) where

Nexthop is the direction I go to reach Next

– If the Tentative list is empty, stop. Otherwise, pick the entry from the Tentative list with the

lowest cost, move it to the Confirmed list, and return to Step 2.

41

Shortest Path Routing

42

Open Shortest Path First (OSPF)

OSPF Header Format

OSPF Link State Advertisement

43

Distance Vector vs. Link State Routing

Node A: to reach F go to B

Node B: to reach F go to D

Node D: to reach F go to E

Node E: go directly to F

A

B

C

▪ With distance vector routing, each node has information only about the next hop:

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

E

Distance vector routing makes

poor routing decisions if

directions are not completely

correct

(e.g., because a node is down).

D

▪

If parts of the directions incorrect, the routing may be incorrect until the routing algorithms has reconverged.

44

44

F

Distance Vector vs. Link State Routing

C

A

B

E

C

F

A

C

B

C

A

E

F

D

C

B

E

B

A

D

E

F

D

D

In link state routing, each node has a complete map of the topology

B

F

▪

A

E

▪

D

If a node fails, each

node can calculate

the new route

A

E

C

▪

B

Difficulty: All nodes need to

have a consistent view of the

network

A

D

45

B

E

C

F

D

F

F

45

Link State Routing: Properties

▪ Each node requires complete topology information

▪ Link state information must be flooded to all nodes

▪ Guaranteed to converge

46

46

Link State Routing: Basic principles

1. Each router establishes a relationship (“adjacency”) with its neighbors

2. Each router generates link state advertisements (LSAs) which are distributed to all

routers

LSA = (link id, state of the link, cost, neighbors of the link)

3. Each router maintains a database of all received LSAs (topological database or link

state database), which describes the network as a graph with weighted edges

4. Each router uses its link state database to run a shortest path algorithm (Dijikstra’s

algorithm) to produce the shortest path to each network

47

47

Received

LSAs

LSAs are flooded

to other interfaces

Link State

Database

Dijkstra’s

Algorithm

Operation of a Link State Routing protocol

48

IP Routing

Table

48

Riga Technical University

49

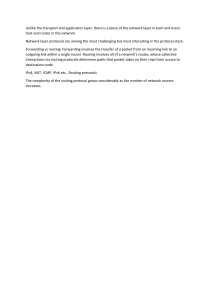

OSPF

▪ OSPF = Open Shortest Path First

▪ The OSPF routing protocol is the most important link state routing protocol on the Internet

▪ The complexity of OSPF is significant

▪ History:

– 1989: RFC 1131 OSPF Version 1

– 1991: RFC 1247 OSPF Version 2

– 1994: RFC 1583 OSPF Version 2 (revised)

– 1997: RFC 2178 OSPF Version 2 (revised)

– 1998: RFC 2328 OSPF Version 2 (current version)

50

50

Provides authentication of routing messages

Enables load balancing by allowing traffic to be split evenly across routes with equal cost

Type-of-Service routing allows to setup different routes dependent on the TOS field

Supports subnetting

Supports multicasting

Allows hierarchical routing

Features of OSPF

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

51

51

10.10.10.1

.1

.1

4

.2

10.10.10.2

.2

10.1.1.0 / 24

2

.2

2

.4

10.1.4.0 / 24

3

.5

10.10.10.4

.4

.5

5

.3

.3

2.0

.1.

10

10.1.5.0/24

10.10.10.5

.4

.5

52

1

10.1.7.0 / 24

1

.6

/2

4

10

.1.

8.0

3

.3

10.10.10.2

10.1.6.0 / 24

Example Network

Router IDs are

selected

independent of

interface addresses

Link costs are called Metric

Metric is in the range [0 , 216]

Metric can be asymmetric

10.1.3.0 / 24

10.10.10.6

.6

52

4

/2

3

.1

.2

.4

10.1.4.0 / 24

10.10.10.4

.4

10.10.10.2

.2

10.1.1.0 / 24

.2

.5

.5

.3

.3

10.1.5.0/24

2.0

.1.

10

10.10.10.5

.4

.5

10.1.7.0 / 24

.6

/2

4

10

.1.

8.0

10.10.10.1

.1

.3

53

10.10.10.2

10.1.6.0 / 24

Link State Advertisement (LSA)

Link ID = 10.1.1.1, Metric = 4

Link ID = 10.1.2.1, Metric = 3

Link ID = 10.10.10.1, Metric = 0

▪ The LSA of router 10.10.10.1 is as

follows:

▪ Link State ID:

10.10.10.1 = can be Router ID

▪ Advertising Router:

10.10.10.1 = Router ID

▪ Number of links:

3 = 2 links plus router itself

▪ Description of Link 1:

▪ Description of Link 2:

▪ Description of Link 3:

Each router sends its LSA to all routers in the network

(using a method called reliable flooding)

10.1.3.0 / 24

10.10.10.6

.6

53

4

/2

Network and Link State Database

10.10.10.1

.1

2.0

.1.

10

LS Type

10.1.10.1

Link StateID

10.1.10.2

10.1.10.1

Adv. Router

4

/2

Router-LSA

10.1.10.2

10.1.10.3

.2

.4

10.10.10.4

.4

10.1.4.0 / 24

.2

.5

.5

.3

0xe39a

0x6b53

0x219e

0x9b47

Checksum

10.1.5.0/24

.3

10.10.10.2

.2

Router-LSA

10.1.10.3

10.1.10.4

0xd2a6

0x05c3

.4

10.1.7.0 / 24

.6

10.10.10.6

0x8000003a

0x80000003

0x80000007

0x80000006

LS SeqNo

18

20

1712

1618

0

LS Age

.6

0x80000038

1680

54

0x80000005

.5

/2

4

10

.1.

8.0

10.1.1.0 / 24

Router-LSA

10.1.10.4

10.1.10.5

.1

Router-LSA

10.1.10.5

10.1.10.6

Each router has a

database which

contains the LSAs

from all other routers

Router-LSA

10.1.10.6

.3

Router-LSA

10.10.10.5

10.1.6.0 / 24

10.10.10.2

10.1.3.0 / 24

54

Link State Database

▪ The collection of all LSAs is called the link-state database

▪ Each router has and identical link-state database

Useful for debugging: Each router has a complete description of the network

–

▪ If neighboring routers discover each other for the first time, they will exchange their link-state

databases

▪ The link-state databases are synchronized using reliable flooding

55

55

OSPF Packet Format

IP header

OSPF packets are not

carried as UDP payload!

OSPF has its own IP

protocol number: 89

OSPF Message

Header

TTL: set to 1 (in most cases)

OSPF Message

LSA

Header

LSA

LSA

Data

LSA

... ...

Body of OSPF Message

Message Type

Specific Data

Destination IP: neighbor’s IP address or 224.0.0.5

(ALLSPFRouters) or 224.0.0.6 (AllDRouters)

56

LSA

56

OSPF Packet Format

2: current version

is OSPF V2

OSPF Message

Header

Message types:

1: Hello (tests reachability)

2: Database description

3: Link Status request

4: Link state update

5: Link state acknowledgement

Standard IP checksum taken

over entire packet

version

message length

Body of OSPF Message

type

authentication type

Area ID

source router IP address

checksum

authentication

32 bits

authentication

Authentication passwd = 1: 64 cleartext password

Authentication passwd = 2: 0x0000 (16 bits)

KeyID (8 bits)

Length of MD5 checksum (8 bits)

Nondecreasing sequence number (32 bits)

ID of the Area

from which the

packet originated

0: no authentication

1: Cleartext

password

2: MD5 checksum

(added to end

packet)

Prevents replay

attacks

57

57

OSPF LSA Format

LSA

LSA

Header

LSA

Data

LSA

Header

Link 1

Link 2

Link Age

Link Type

Link State ID

advertising router

Metric

Metric

length

link sequence number

Link ID

Link Data

#TOS metrics

Link Data

Link ID

#TOS metrics

checksum

Link Type

Link Type

58

58

Discovery of Neighbors

10.1.10.2

Scenario:

Router 10.1.10.2 restarts

▪ Routers multicasts OSPF Hello packets on all OSPF-enabled interfaces.

▪ If two routers share a link, they can become neighbors, and establish an adjacency

10.1.10.1

OSPF Hello

OSPF Hello: I heard 10.1.10.2

▪ After becoming a neighbor, routers exchange their link state databases

59

59

Acknowledges

receipt of

description

Sends database

description.

(description only

contains LSA

headers)

10.1.10.1

OSPF Hello

OSPF Hello: I heard 10.1.10.2

Database Description: Sequence = X+1

Database Description: Sequence = X+1, 1 LSA header=

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.2, 0x80000005

Database Description: Sequence = X, 5 LSA headers =

Router-LSA, 10.1.10.1, 0x80000006

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.2, 0x80000007

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.3, 0x80000003

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.4, 0x8000003a

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.5, 0x80000038

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.6, 0x80000005

Database Description: Sequence = X

Database

description of

10.1.10.2

Sends empty

database

description

Scenario:

Router 10.1.10.2 restarts

10.1.10.2

After neighbors are discovered the nodes exchange their databases

Discovery of

adjacency

Neighbor discovery and

database synchronization

60

60

10.1.10.1 sends

requested LSAs

Regular LSA exchanges

61

10.1.10.1

Link State Request packets, LSAs =

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.1,

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.2,

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.3,

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.4,

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.5,

Router-LSA,

10.1.10.6,

Link State Update Packet, LSAs =

Router-LSA, 10.1.10.1, 0x80000006

Router-LSA, 10.1.10.2, 0x80000007

Router-LSA, 10.1.10.3, 0x80000003

Router-LSA, 10.1.10.4, 0x8000003a

Router-LSA, 10.1.10.5, 0x80000038

Router-LSA, 10.1.10.6, 0x80000005

Link State Update Packet, LSA =

Router-LSA,

10.1.1.6, 0x80000006

10.1.10.2

10.1.10.2 explicitly

requests each LSA

from 10.1.10.1

10.1.10.2 has more

recent value for

10.0.1.6 and sends it

to 10.1.10.1

(with higher sequence

number)

61

10.10.10.1

Update

database

ACK

LSA

10.10.10.2

Update

database

10.10.10.2

LSA

LSA

10.10.10.5

Update

database

10.10.10.4

LSA-Updates are distributed to all other routers via Reliable Flooding

Example: Flooding of LSA from 10.10.10.1

Routing Data Distribution

•

•

62

LSA

ACK

Update

database

10.10.10.6

Update

database

62

Dissemination of LSA-Update

▪ A router sends and refloods LSA-Updates, whenever the topology or link cost changes. (If a

received LSA does not contain new information, the router will not flood the packet)

▪ Exception: Infrequently (every 30 minutes), a router will flood LSAs even if there are no new

changes.

▪ Acknowledgements of LSA-updates:

▪ explicit ACK, or

implicit via reception of an LSA-Update

▪

63

OSPF Design Service Provider Networks

64

OSPF Areas and Rules

•

•

•

•

Backbone area (0)

must exist

All other areas

must have

connection to

backbone

Backbone must be

contiguous

Do not partition

area (0)

Area 2

Backbone

Router

Internet

Area 4

Area

Border

Router

Area 0

Ruteador

Interno

Area 3

Area 1

Autonomous

System (AS)

Border Router

65

Autonomous Systems

▪

▪

An autonomous system is a region of the Internet that is administered by a single entity.

Examples of autonomous regions are:

▪ UVA’s campus network

▪ MCI’s backbone network

Regional Internet Service Provider

▪

▪

Routing is done differently within an autonomous system (intradomain routing) and between

autonomous system (interdomain routing).

66

Ethernet

Ethernet

Router

Router

Autonomous

System 1

Router

Ethernet

Ethernet

Autonomous

System 2

Router

Router

Ethernet

Autonomous Systems (AS)

Ethernet

Router

67

67

OSPF Design

▪ Figure out your addressing first – OSPF and addressing go together

– The objective is to maintain a small link-state DB

– Create address hierarchy to match the network topology

– Separate blocks for infrastructure, customer interfaces, customers, etc.

68

OSPF Design

▪ Examine the physical topology

– Is it meshed or hub-and-spoke (star)

▪ Try to use as Stubby an area as possible

– It reduces overhead and LSA counts

▪ Push the creation of a backbone

– Reduces mesh and promotes hierarchy

69

OSPF Design

▪ One SPF per area, flooding done per area

– Try not to overload the ABRs (Area border router)

▪ Different types of areas do different flooding

– Normal areas

– Stub areas

– Totally stubby (stub no-summary)

– Not so stubby areas (NSSA)

70

OSPF Design

▪ Redundancy

– Dual links out of each area – using metrics (cost) for traffic

engineering

– Too much redundancy …

▪ Dual links to backbone in stub areas must be the same –

otherwise sub-optimal routing will result

▪ Too much redundancy in the backbone area without good

summarization will affect convergence in the area 0

71

OSPF for ISPs

▪ OSPF features you should consider:

– OSPF logging neighbor changes

– OSPF reference cost

– OSPF router ID command

– OSPF Process Clear/Restart

72

OSPF Best Common Practices – Adding Networks

73

OSPF – Network Aggregation

•

BCP – Individual OSPF network

statement for each infrastructure link

– Have separate IP address blocks

for infrastructure and customer

links

– Use IP unnumbered interfaces or

BGP to carry /30 to customers

– OSPF should only carry

infrastructure routes in an ISP’s

network

OC12c

ISP Backbone

OC48

Customer Connections

OC12c

74

OSPF – Adding Networks

▪ Redistribute connected subnet

– Works for all connected interfaces on the router but sends networks as external types-2s –

which are not summarized

▪ router ospf 100

redistribute connected subnets

▪

▪ Not recommended

75

OSPF – Adding Networks

▪ Specific network statements

– Each interface requires an OSPF network statement. Interfaces that

should not bet broadcasting Hello packets need a passive-interface

statement

▪ router ospf 100

▪

network 192.168.1.1 0.0.0.3 area 51

▪

network 192.168.1.5 0.0.0.3 area 51

passive interface Serial 1/0

▪

76

OSPF – Adding Networks

▪ Network statements - wildcard mask

– Every interface covered by a wildcard mask used in the OSPF network

statement. Interfaces that should not be broadcasting Hello packets

need a passive-interface statement or default passive-interface should

be used

▪ router ospf 100

▪

network 192.168.1.0 0.0.0.255 area 51

▪

default passive-interface default

no passive interface POS 4/0

▪

77

OSPF – Adding Networks

▪ The key theme when selecting which method to use is to keep the links-state DB as small as

possible

– Increases stability

– Reduces the amount of information in the LSAs

– Speeds up convergence time

78

OSPF – Useful Features

79

OSPF Logging Neighbor Changes

▪ The router will generate a log message whenever an OSPF neighbor changes state

▪ Syntax:

▪ [no] ospf log-adjacency-changes

▪ A typical log message:

▪ %OSPF-5-ADJCHG: Process 1, Nbr 223.127.255.223 on Ethernet0 from

LOADING to FULL, Loading Done

80

Number of State Changes

▪ The number of state transitions is available via SNMP (ospfNbrEvents) and the

CLI:

– show ip ospf neighbor [type number] [neighbor-id] [detail]

▪ Detail—(Optional) Displays all neighbors given in detail (list all neighbors).

When specified, neighbor state transition counters are displayed per

interface or neighbor ID

81

State Changes (Cont.)

▪ To reset OSPF related statistics, use the clear ip ospf counters EXEC command.

– clear ip ospf counters [neighbor [<type number>] [neighbor-id]]

82

OSPF Cost: Reference Bandwidth

▪ Bandwidth used in metric calculation

– Cost = 10^8/BW

– Not useful for BW > 100 Mbps but can be changed

▪ Syntax:

– ospf auto-cost reference-bandwidth <reference-bandwidth>

▪ Default reference bandwidth is still 100Mbps for backward compatibility

83

OSPF Router ID

▪ If the loopback interface exists and has an IP address, that is used as the router ID in

routing protocols - stability!

▪ If the loopback interface does not exist, or has no IP address, the router ID is the highest

IP address configured – danger!

▪ Subcommand to manually set the OSPF router ID :

– router-id <ip address>

84

OSPF Clear/Restart

▪ clear ip ospf [pid] redistribution

–This command can clear redistribution based on OSPF routing process ID. If no PID

is given, it assumes all OSPF processes

▪ clear ip ospf [pid] counters

–This command clear counters based on OPSF routing process ID. If no PID is given,

it assumes all OSPF processes

▪ clear ip ospf [pid] process

–This command will restart the specified OSPF process. If no PID is given, it assumes

all OSPF processes. It attempts to keep the old router-id, except in cases where a new

router-id was configured, or an old user configured router-id was removed. It requires

user confirmation because it will cause network churn.

85

OSPF Command Summary

86

Redistributing Routes into OSPF

– ROUTER OSPF <pid#x>

– REDISTRIBUTE {protocol} <as#y>

–

<metric>

–

<metric-type (1 or 2)

–

<tag>

–

<subnets>

–

87

NETWORK <n.n.n.n> <mask> AREA <area-id>

AREA <area-id> STUB {no-summary}

AREA <area-id> AUTHENTICATION

AREA <area-id> DEFAULT_COST <cost>

AREA <area-id> VIRTUAL-LINK <router-id>...

AREA <area-id> RANGE <address mask>

OSPF Router Sub-Commands

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

88

IP OSPF COST <cost>

IP OSPF PRIORITY <8-bit-number>

IP OSPF HELLO-INTERVAL <number-of-seconds>

IP OSPF DEAD-INTERVAL <number-of-seconds>

IP OSPF AUTHENTICATION-KEY <8-bytes-of-password>

Interface Sub-Commands

▪

▪

▪

▪

▪

89

Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP)

Destination host unreachable due to link /node failure

Reassembly process failed

Time To Live had reached 0 (so datagrams don't cycle forever)

IP header checksum failed

▪ Defines a collection of error messages that are sent back to the source host whenever a router or

host is unable to process an IP datagram successfully

–

–

–

–

▪ ICMP-Redirect

– From router to a source host

– With a better route information

90

91