Ethical Objectivism Critique: Pojman's Argument Analysis

advertisement

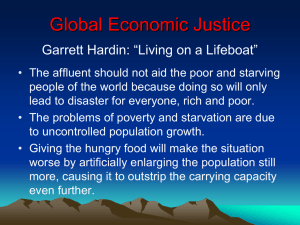

Samuel Sanders 005700717 Philosophy 191 Professor Vanderburgh 22 October 2018 A Critique of Ethical Objectivism In this paper I will state and critique Pojman’s argument for the objective nature of ethics. Pojman’s argument supports the notion that ethical objectivism exists. He further argues that there are implications with the ethical relativism ideology and therefore it is false. I will counter Pojman’s argument and claim that it is possible for ethical relativism to exist and for ethical objectivism to be false. Ethical objectivism refers to rules that inherently exist in the universe that can be applied to everyone. Ethical relativism is the belief that morality stems from society and culture. Pojman critiques ethical relativism in his argument, suggesting that there are problems with the premises for the argument. The first premise, known as the diversity thesis, states “What is considered morally right and wrong varies from society to society, so that there are no moral principles accepted by all societies” (Pojman 44). Pojman argues that cultures are not as diverse as we may think and that anthropologists claim there are many similarities across various cultures (Pojman 44). Pojman uses this to suggest that because there are many moral codes that can be found in vastly different cultures, the first premise is weakened and the ethical objectivist standpoint is strengthened. Furthermore, Pojman claims that the moral differences found among different cultures does not necessarily mean ethical relativism is correct, but rather some cultures moral principles may be simply incorrect. Pojman further critiques the second premise of ethical relativism, which states “All moral principles derive their validity from cultural acceptance” (Pojman 44). Pojman argues that this Sanders 2 premise is false by claiming that the same core of moral codes can be found across cultures, but that they are simply applied differently due to “beliefs, history, and environment” (Pojman 45). Pojman claims, “[Other cultures] differ with us only in belief, not in substantive moral principle” (Pojman 45). These critiques create the foundation for Pojman’s argument for ethical objectivism. Pojman’s starts his argument for ethical objectivism by analyzing our intuitions and “by looking at a naturalist account of morality that transcends individual cultures” (Pojman 46). He states that religion is not a necessary component for objective morality and uses non-religious points for developing his argument. Pojman lists a few moral laws he believes can be seen objectively such as one example, Principle A, which states that “it is morally wrong to torture people for the fun of it” (Pojman 47). The argument suggests that any rational human being would agree that torturing people for fun is morally wrong. Furthermore, if there are people that disagree with this principle, perhaps their reasoning needs to be scrutinized. If the majority of rational human beings agree with Principle A, then the behavior of those who do not agree should not affect our intuition. This argument is backed up with examples of scenarios in which it might make sense that some people would not agree with Principle A. Maybe the culture has not evolved like most humans. Perhaps they lack the reasoning to have a moral framework. Therefore, we cannot compare their behavior to what is morally correct because their reasoning is not developed enough to encompass morality. Pojman definition of morality is determined by examining human nature and our common needs and interests. What is deemed as the right thing to do should be judged about what brings the most benefit to our common needs and interest. Furthermore, what is deemed as wrong is what is likely to cause more harm to those common needs and interests. Pojman asserts Sanders 3 that there are moral codes that are not arbitrary and correlate with “social cohesion and human flourishing” (Pojman 48). I will begin my counter argument by firstly stating that there are implications with Pojman’s attempt to prove an objective morality from a non-religious context. According to Pojman, “I don't think that a religious justification is necessary for the validity of moral principles” (Pojman 47). Although I do not necessarily disagree that religion is a necessary component of morality, I do believe a control group is needed to make this claim. I do not think it is possible to examine a control group because most societies have had a religious history. Societies that have not had any religious history, perhaps a tribe in South America, have their own cultural inheritance. Therefore, in order to make this claim, we must be able to examine a society with no religious history or culture. Furthermore, Pojman makes the assertion that there must be a universal rule in which “to do right” is associated with what brings the most benefit to our common human needs and interests and “to do wrong” is to go against these common human needs and interests. In order to make this claim, a person has to take a position that there is some governing force in the universe, such as a god, that has set these rules. I am willing to suggest that this definition of “right and wrong” is subjective and based off of our own desires for survival. If we look at the behavior of other living animals, we can make the assertion that they do not follow the same moral principles as we do. To assume that the moral principles that apply to us do not apply to them suggests that there is no universal objective morality that applies to all beings. We cannot deny that animals also have basic needs and interests that they need met, yet a lion will still kill an innocent cub from the its own species. If one were to say humans have greater importance Sanders 4 than animals, they would have to assume there is some force in the universe that has decided this. A counter argument from an ethical objectivist standpoint to consider is that the same moral principles that apply to us also apply to other species, however, other species are incorrect in their moral principles similarly to these other cultures that Pojman discusses in his argument. I would counter argue this point by saying we cannot establish a criterion in what moral principles should be considered the correct moral principles and that this flawed logic. We cannot impose one cultures moral principles as correct and others as false unless there is established moral codes in the fabric of the universe. This is something that I do not think is possible to ever know. Furthermore, if there are truly universal moral codes, then there must be some kind of governing agents that have established these rules. In conclusion, Pojman makes a good defense for ethical objectivism. He claims that there are certain moral principles that could be applied to everyone and that the foundation of these moral principles are determined by our common human interests and needs. However, there are several flaws in Pojman’s logic, such as assuming there is an objective basis for right or wrong. In this paper, I critique some of Pojman’s points and make the argument that “right and wrong” is subjective and not objective. To assume these characteristics are objective, one must assume and prove that there are governing agents in the universe that have established these principles. Works Cited Moral Philosophy : A Reader, edited by Louis P. Pojman, and Peter Tramel, Hackett Publishing Company, Incorporated, 2009. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csusb/detail.action?docID=601015. Sanders 5