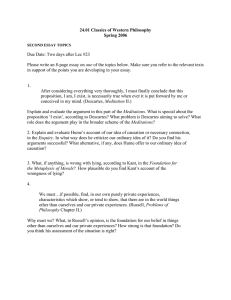

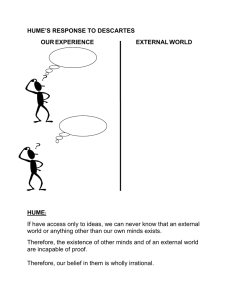

Philosophers: 1. Presocratics* - Presocratics were Greek thinkers who introduced a new way of questioning and inquiring into the world. They all commit to finding an archaea, which is the fundamental thing that underlies all of reality - it means the prinicple of things - and they all, someway or another relates to nature. Prior to Presocratic things, people would rely on Theological explanations (Religion) 2. Thales* - He was the first scientist and philosopher, who believed that "water" was the source of reality - the principle thing that unifies all of existence 3. Parmenides* - Parmenides believes that the universe is unchanging. That the reality remains the same, 'cause otherwise it will violate the LAW OF CONTRADICTION where something cannot be a A and NOT A simultaneously. ;"only our senses convey the appearance of change" 4. Heraclitus* - Heraclitus believes that all there is change in the world, using the example of how one cannot step on the river twice. He thinks that there is perpetual occurance of change, howver that contradicts itself as "a change cannot change" 5. Socrates - looking for definitions of things that cannot be refuted. Is one of the most wellknown Philosopher who helped pioneer Western Philosophy. Socrates believes that philosophy should have practical input that can help us reorient our lives, and show us how to live a good life. 1. Says God claimed him to be "the wisest of men." He came of as haughty and arrogant as he questioned/showing up influential and powerful people in public. They were: 1. Poets 2. Craftsmen 3. Politicians 2. His formal charges: 1. Impiety - didn't believe/respect God 2. Corrupting the youth 3. Though the real reason was due to : Alcibades, who was a student of Socrates, and later became a military strategist of Athens. Alcibades was accused of destroying religious status, and feeling wronged joins the Spartans. Hence, since no one could do anything to him, used Socrates as the scapegoat; They believed that Socrates was the cause of him flipping sides. 3. Socrates believed that the trail was below him, and assumed that people accuse him of two things when all he is trying to do is making people become better/smarter individuals. 1. Sophists - Sophists are indiviuals that present arguements without caring about factual things - as in are they paid to teach others how to argue with others. Socrates refutes that he doesn't argue for the hell of it, that he merely speaks/questions, and not to mention, he doesn't get paid for those. 2. Pre-Socratic Philosophers - They claim that he challengesd God. However, Socrates says he knows nothing. 4. Socrates suggests that as a punishment : the Athenian court pays him and serve him meals in compensation for the wrongful accusations. And that he will have his pay 30 Minaes. His friends try to bribe the judge and convince them to acquit Socrates, but the latter refuses. 5. They charge him guilty, and is sentanced to death by suicide. Although a slightly forlorn, he accepts it because believes that God did it for a reason. He thinks that at least he can go to afterlife and talk to intelligent, knowledgeable people who have died. Plus, through death, at least he can get eternal sleep, which he likes. 6. Socrates represents an ideal philosopher - where he seeks out the truth above all. He challenges people out of dogmatism and skepticism, but is unable to do a good job finding the answers 7. Socrates is considered the wisest person according to the Oracle because he is aware of his limit of knowledge in contrast to the ignorant and dogmatic people who pretend to know everything. 8. According to Socrates, justice makes people better - it's about not harming anyone. Says it's better to be a "just" man than to be an "unjust" man 9. Socrates is a realist- believes that the realm of forms exist; it's not just a thing in our head. 1. REALIST : God exists 2. IDEALIST : God exists in our head 6. Plato - Was Socrates' prized student, who is a realist when it came to the Realm of the Forms. Wants us to know the true forms - to get to the realm of the forms 1. Writes the "Allegory of the Cave" to portray what it's like to be a philosopher 1. "republic" Define Justice 2. A realist 3. Wants us to know the true forms - to get to the realm of the forms 7. Aristotle 1. Aristotle- Doesn't like Plato's view, that the answers are somewhere out there; he believes that the answers are around us -there are four causes: 1. Material cause - the real, tangible stuff that makes things up (ex. Giraffe made up of skins, hair, muscles) 2. Formal cause - why something is the way it is - the shape or structure (ex.Giraffeit's long neck, four legs- a giraffe shape) 3. Efficient cause - Act / actor that brought something into being/existence (ex. Chalk - who ever made it / some sort of assembly line, Giraffe - giraffe parents/sex) 4. Teleological cause - the end purpose; the thing that allows the thing to flourish (ex. Chalk - to write, Giraffe - to do the most special thing; what it's best suited for - eating leaves from the tallest tree) So: ESSENCE- to find the human essence / or the essence of things Everything has an essence 8. Descartes - Aristotle said that the Earth was the center of the enviornment, which he overturned 1. Any belief that he has a smidge of doubt will be thrown out 1. Challenges the view of our senses - as it can deceive us all the time 2. Dreaming - Believes that everying that is happening is a dream - Descartes still is not okay with that b/c in a dream, the basic geometry, maths still are held to be true 3. Deceived by God - but the prob. with using God is b/c God does good and is perfect 4. So then, believes that we are being Deceived by an evil demon - allows us to doubt everythg 2. In exam***Does Descrates believe in an evil demon? No, he doesn't believe, but what he is saying is that he cannot really disprove the possibily of the there being an evil demon; that there is a slight chance that there is an evil demon but cannot prove it because we are constantly decieved "I think therefore I am"- Demon cannot deceive him of that; to be deceived is to have a thought. "One thing for certain- There has to be thought in reality, cannot doubt that as we know that for certainty 3. He is dualist - have an internal mind and a physical body - two world- Mental AND Physical 4. Deductive (General to specific; ex. From general rules/formulas, you solve specific mat problems) vs. Inductive (specific instance to form a general conclusion; ex. On, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday; saw a white swan, Inductive reasoning - all swans are white or Since I like milk, everyone else likes milk) Aristotle based Inductive reasoning for his thoughts So Descartes wanted to use deductive reasoning - wants to get back our sense, hence needs to prove the existence of God. Now his argument gets shaky Proved that there's a Mental Mind (soul, our mind that is impenetrable, invulnerable, helps us get the stuff that cannot be proven by science, like religious stuuf like God/Free will) and Physical Body (Science describes our physical stuff - laws and rules of science) Allows Descartes to have his cake and eat it too, becasue we can have both the spiritual and the physical stuff/ So, how can we tell our mind what we do (our physical body)? The mind-body problem. Descartes ans: Pinial gland- has a magical part His student's ans: My mind is praying to God (has a connection to God, God then moving my limbs Carestian Circle Problem: Descartes basically gives us a circular argument: Clear Disticnt Perception 9. Locke - A dualist 1. Three laws describe the mental world 1. Association 2. Causation 3. Identity Defends Empiricism do not experience objects directly, but experience through filtered, represented ideas - the emotions/ideas they invoke in us The only way to bring about change in the primary qualities is to physically change/do something to the object. To change secondary qualities - change the object LAWS: 1. Association - you have/think of two things that go together. (Hear peanut butter, and think of jelly) butter, and think of jelly) 2. Causation - One event followed by a another (See lightening, then hear thunder, so then assume that the lightening caused the thunder) 3. Identity - How we point out things are going to shape what we see in reality as a whole, so like a whole new compound (ex. Chalk and hat, when combined becomes something as whole) 4. Personal Identity - is tied to the continuity of our concious experience. Our mind makes who we are, more so than our body 2. Rationalism Empiricism Ex. Plato (Jason Forda in ex. Maybe Locke isn't an Empiricist, but we present) and Descartes --- are consider him for the exam there are no innate some, even one or two, innate ideas. Everything we know is through ideas experience 10. Berkeley - Not a dualist - defends idealism - where everything is in our mind. - Perceive ordinary objects - we perceive eveything God puts in our mind----> Change the primary qualities by changing the observer, change the object, change the enviroment 1. 1. accepts the argument that we can have no idea whatsoever what a substance might be—that all we can know of a thing are its sensible properties or “qualities” (straight from Locke) 2. 2. dissolves the distinction between primary and secondary qualities—it cannot be a distinction (as Locke argued) between properties inherent in the objects themselves as opposed to the properties that the objects simply cause in us 3. 3. once one accepts that all knowledge of the world (except for knowledge of one’s one existence and of God’s existence) must be based upon experience, then why should one think that there is anything other than our experiences. Proves God's Existence: God arranges that our ideas and how they are synchronized. We perceive the ideas God's instill in our mind As Berkley believes, everything is percieved from what God puts in our mind God plays the exact role in Berkley's as the physical world plays in Locke's Two things: Two things: 1. Spirit - active mind- The perceiving 2. Ideas - passive - The perceived Berkley's argument Perceive ordinary objects Locke's point - all that we perceive are ideas All ordinary objects are ideas Why it's Radical? Can you imagine a tree that no one experience? The sencond you imagine it, you already perceive it. (Thining of an imaginary thoucht is a perception) Conflates two things- "what we perceive with" - has to be ideas (Locke's) is being confused with "what we are having perceptions of" - Berkley doesn't definitively prove that there are ideas As an Empiricist, you can not say God puts ideas as we have never experienced it. 11. Hume -that Reason cannot help us understand how the world is going to be. Reason cannot do anything (makes no mistakes in his radical argument, in comparison to Berkley and Locke) 1. don't really rely on reason since it's not reason that we use to get through the day. We rely on habits, instincts, and customs 2. Relations of ideas 1. Rationalism - innate 2. A priori - before experience 3. Matters of Fact 1. Empiricist - experience 2. Post posteriori - after experience DIFFERENCES: DIFFERENCES: LOCKE - There are primary qualities - figure, extension...etc. are part of the objects (not observer relative; objective; in the object) and secondary qualities (observer relative; not in the object; in the observer) - The only way to bring about change in the primary qualities is to physically change/do something to the object. To change secondary qualities - change the object (like primary qualities) , change the observer, change the environment (seeing something- colors- in the light vs the dark) BERKLEY - Change the primary qualities by changing the observer, change the object, change the enviroment (work just as the Locke's secondary qualities) WHY BAD EMPIRICIST? Berkley - believes in god, but has not empirical basiss- never experienced- God Locke - all we can experience properties of things (which are mental things); postulates an external world of substances but never experienced objects directly All philosophers were obsessed with Reason to figure out how the world works and operates. Use it to solve problems presented to us, to face issues in the future David Hume tries to show: that Reason cannot help us understand how the world is going to be. Reason cannot do anything (makes no mistakes in his radical argument, in comparison to Berkley and Locke) Relations of Ideas Matters of Fact. -> Statements either intuitvely or -> Cause and effect - take us beyond the demonstrativley certain evidence of our memory and senses ###### Relations of Ideas Matters of Fact. -> Statements either intuitvely or demonstrativley certain -> A sub-class of Cause Math and logic (Deductive reasoning) and effect - take us General rules that we apply at instances to get answers beyond the evidence of A priori- prior to experience our memory and senses Don't need to experiment, go out to the world to test - can Domain of the figure out on your own in your head sciences/experiencialy Stuff you can figure out prior to experience stuff Are Innate (stuff that Rationalists carry out) Rely on inductive reasoning - have to Rationalist - Plato and Descarte actually test Ex. Something true by definition (don't need to ask a things/experiment to bachelor if they are unmarried b/c that's what bachelor figure out/form general stands for ) rules & conclusions Can't help tell us any interesting insight about the world: Something you cannot b/c they are what we already know- what and how are know prior to the concepts pick out things in the world - what is already in experiment our heads - what the rules of concepts (i.e math, which is A posteriori - after a constructed concept) are experiment What the Empricist believes in - Berkley, Locke, Hume Cannot tell us how the world is going to be As in Empricist, you don't know if the sun is going rise tomorrow, 'cause you haven't experienced it - experienced the future. Can assume and take a leap of fate that the laws of science will hold. (All you know as an Empriscit is the immediate present- can never be sure of the future or the past - all way know is the infintile, small time-slice of the present before we blink out of existence) - So basically, we know nothing Continuity of nature - an assumption (no way of verifying that) the future will resemble the past David Hume shows the limit of reasons- don't really rely on reason since it's not David Hume shows the limit of reasons- don't really rely on reason since it's not reason that we use to get through the day. We rely on: Acting according to Habits - intrapersonal life- a lot of experiencial basis Customs/traditions - cultures and generations of people figuring out why we behave the way we do Instincts - species - entire story of life built up the experiencial basis ex. Drinking water can quench your thirst - is based on habits, customs/instincts - we don't expect or stop to reason about that Hence, reason has very little empricial bases on why and what we do. Science isn't grounded on reason *Hume says screw philosophy - to screw using it as a tool to navigate the world. Just go about relying on the habits, customs, and the instincts. Don't think Philosophy will give us an answer to anything - to help us lead our lives. 12. Kant - mind is actively engaging. Kant saw the mind as an organ that soaked up sensory experiences and turned them into ideas (which was like the empiricists), but he also argued that the ordering of that experience was governed by inherent biases and constraints (which was like the rationalists). For example, he argued that the human mind has an innate conception of linear causality – event A happens, which causes event B to happen. We don’t actually see the causality. What we see is event A, followed by event B happening. But the mind is inherently biased to see the two events as connected, and so we infer causality from our experience. The modern scientific method is based on the assumption that these kinds of biases exist in the human mind, and that we need to correct for them using controlled experiments and careful measurement. What Empiricist say means passive conception of mind - mind is not doing stuff, mind a blank canvas, reality is just projected onto a screen, a black box/vessle that carries the ideas He says mind can't be passive, casue otherwise will be overload. It's active - actively filtering in the relevant stuff filtering in the relevant stuff To rationalists he says - Mind can't be just sitting there, waiting for stuff. The world isn't automatically give to you. He argues that it's always radically active. 1. Ends the debate to rationalism and empiricism 2. Two ways to Reason according to Hume: 1. Relations of ideas 1. Rationalism - innate 2. A priori - before experience 2. Matters of Fact 1. Empiricist - experience 2. Post posteriori - after experience Kant says both Rationalism and Empiricist are wrong What Empiricist say means passive conception of mind - mind is not doing stuff, mind a blank canvas, reality is just projected onto a screen, a black box/vessle that carries the ideas He says mind can't be passive, casue otherwise will be overload. It's active - actively filtering in the relevant stuff To rationalists he says - Mind can't be just sitting there, waiting for stuff. The world isn't automatically give to you. He argues that it's always radically active. Constructus : Actively engages in constructing our perceptions of reality (transcendental idealist) 1. Phenomenoal world - world of experience 2. Numinal world - world in and of itself / world out there ( World it truly is independent of our mind's perception) 13. Gettier* - GETTIER PROBLEMS - meet the conditions but not satisfies ; don't have a true definition of KNOWLEDGE - Knowledge, it seems, cannot be the result of accident or “epistemic luck.” Plato: Theaetetus For heuristic purposes, it can be divided into four sections, in which a different answer to this question is examined: (i) Knowledge is the various arts and sciences; (ii) Knowledge is perception; (iii) Knowledge is true judgment; and (iv) Knowledge is true judgment with an “account” (Logos). Knowledge is belief accompanied by an explanation (logos) One way of making mere belief approach the status of knowledge would be to accompany one's judgment with an explanation (or reason) of why one holds this or that belief. Such a reason (logos) would then serve to ground the belief, it would provide a foundation for the judgment, This seems to be the further buttressing that mere belief needs, and the dialogue now begins to move in this direction. Justified true belief is the classical philosophical definition of "knowledge". In other words, if you believe something (the Earth is roughly spherical), the thing which you believe is true (it is), and you have justification for that belief (the horizon is curved, and we can go around the Earth and end up where we left from), then you can be said to have knowledge of that particular fact. THEAETETUS: Define KNOWLEDGE THEAETETUS: Define KNOWLEDGE True belief (if you have a belief and it's true than it's knowledge) Problem with this definition: It isn't justified "Truth- has to do with the worldexistentia not internal" Philosophy has proved: 1. Thinking - as proven by Descartes - internal mental world with though in reality 2. An external world - there is a world out there that the thought occurs in ------ Mind cannot thing or bring itself on its own - has to exist somewhere. Cannot start. Hence has an external thing anchoring our mind. oUr mind can never go beyond our structuring - so it's alwyas filtering Kant Immanuel Kant, writing some 100 years later, gave a similar classification, distinguishing knowledge from opinion and faith. They are all levels of assent. Assent always has a subjective cause, a reason why we assent, and it may have an objective basis in reality. When we assent to something without conviction, the subjective cause is said to be "insufficient," and we hold an "opinion." If the subjective cause is sufficient to induce conviction, yet the person realizes that its objective basis is insufficient to establish its truth, there is "faith." Knowledge is "assent that is sufficient both subjectively and objectively" (Critique of Pure Reason, Part II, Chapter II, Section III). The difference between knowledge and faith lies in the fact that assent is valid for everyone when one has knowledge, but is only valid for one's self when one has faith. Kant Immanuel Kant tried to solve the problems of empiricism without a dogmatic appeal to Immanuel Kant tried to solve the problems of empiricism without a dogmatic appeal to common sense. He employed the conservative strategy of limiting the content of our claims to justification. If we view experience as a connected system of appearances, then we can have a priori knowledge of the basic structure of that experience. Kant used what we now call "transcendental arguments" to show what must be the case if our experience is to be at all possible. Kant tried to do what his predecessors had failed to do—to prove that an external world of physical objects exists. The main premise of his "Refutation of Idealism" is that we can use experience to situate our internal states with respect to time. It is then claimed that we can do so only if we can refer these states to an external system of physical bodies. One way of understanding his claim is that the coherence of our "outer" perceptions must represent an objective fact about physical objects if we are to be able to justify beliefs about our internal states which in fact are justified. (Click here for more.) Regarding probability and induction, Kant took the first of the two paths of Hume's fork. We can establish through a transcendental argument, and not through experience, that nature is uniform. The gist of the argument is that the uniformity of nature is a necessary condition for the ordering of events in time. By taking the path of reason, Kant thought he could establish something even stronger than what Hume denied about probability: that we can discover necessary truths about the course of nature. (Click here for more.) Kant's exposition of his anti-skeptical position is extremely difficult, and for this reason we will not pursue it here. We can make two comments about his general position. First, Kant accepts a certain kind of skepticism. Our claims to knowledge extend only as far as experience can take us. What Kant called "things in themselves" are unknowable. Second, all Kant seems to have shown is a conditional: if experience is ordered in a certain way, then it is necessarily that nature be uniform. This is something Hume could grant. But he could at the same time claim that we are never justified in accepting the antecedent of the conditional, that experience is ordered in the way Kant says it is. Thus Kant has either proved less than he set out to prove (that nature is uniform), or else his proof is defective. It either makes an unsupported dogmatic assumption that experience is suitably ordered, or else covertly supports the claim that experience is ordered by the assumption of the uniformity of nature, which would beg the question. Descartes Writing in the first part of the seventeenth century, Descartes, in an unpublished work, Writing in the first part of the seventeenth century, Descartes, in an unpublished work, declared that "All knowledge [scientia] is certain and evident cognition [cognitio]" (Rules for the Direction of the Mind, Rule Two). Certainty, in turn, is freedom from doubt. We shall later consider Descartes's epistemic standards for certainty. Cognitions differ in their degree of certainty. Descartes distinguished between "absolute" and "moral certainty" (Principles of Philosophy Part Two, Article 206). We are absolutely certain "when we believe that it is wholly impossible that something should be otherwise than we judge it to be" (Principles of Philosophy Part Two, Article 206). We have moral certainty, which is not sufficient for scientia, when we do not normally doubt the truth of what we believe, though we recognize that it may be false. Moral certainty is sufficient for the practical conduct of life. If we were to hold out for scientia before conducting our affairs, we would be paralyzed. Perhaps more importantly for Descartes, he could claim moral certainty with respect to his scientific theories of the world. It was in the context of justifying the uncertain hypotheses made in the conduct of science that he introduced the distinction. Other "rationalist" philosophers such as Spinoza and Leibniz developed accounts of levels of certainty of cognitions (see Spinoza's Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect and Leibniz's "Meditations on Knowledge, Truth, and Ideas"). But for them, as for Descartes, the prize was absolute certainty. Locke John Locke defined knowledge in an unusual way that we will not discuss here. Like Descartes, Locke held that knowledge must be evident and certain, and he also followed Descartes by distinguishing between degrees of certainty (An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Book IV, Chapter II). Locke, however, claimed that knowledge does not require absolute certainty, but only a subjective kind of certainty. Specifically, Locke held that we can have knowledge of the existence of objects which are presently perceived. The reason he explicitly called this "knowledge" is that we are unable to bring ourselves to doubt in these cases. What falls short of this standard is called "opinion" or "probability." Hume Hume David Hume wrote of the "assurance" we have in knowledge. He did not specify the degree of assurance required for knowledge, but it appears that he had Cartesian "absolute certainty" in mind (A Treatise of Human Nature, Book I, Part III, Section 11). He distinguished a level of assurance he called "proof," which is "entirely free from doubt and uncertainty." This is contrasted with probability proper, which is attended with uncertainty. The accounts of knowledge handed down by the most influential modern philosophers set the tone for their epistemological investigations. Because they embraced very high standards of knowledge, they were constrained to limit the scope of knowledge severely. Only Locke allowed that we can have knowledge of particular facts about the external world. Descartes and Kant thought that we can know some general facts about the external world, i.e., that it exists, and that is governed by various laws of nature. Hume did not even allow this much. On the other hand, Hume devoted much of his attention to lesser grades of cognition—grades of cognition that present-day philosophers are willing to count as knowledge. Concepts:** Metaphysics - The study of reality; mind and their perceptions "ideas" ; what really is real ex. Ordinary objects Epistemology - study of knowledge - the nature of knowledge and its opposite view skepticism Ontology - dealing with the nature beings - ontology is the study of what there is Ontology and metaphysics both get confused with epistemology, but epistemology is easier Ontology and metaphysics both get confused with epistemology, but epistemology is easier to separate out. Epistemology is the study of knowledge, of how we know what we know. Whereas ontology and metaphysics are about reality, epistemology is about how human consciousness can interact with that reality. Ontology Metaphysics Epistemology Do souls exist? Are they What physical laws would have How can we know whether the sort of things that to be true in order for souls to souls exist? Can human obey physical laws? Is exist? What rules, if any, govern beings ever know wherter there a God? God’s actions? there is God? Ontology is the study of being. It focuses on several related questions: What things exist? (stars yes, unicorns no, numbers . . . yes?) What categories do they belong to? (are numbers physical properties or just ideas?) Is there such a thing as objective reality? What does the verb “to be” mean? study of being "i think is real and i think is not real." Archea* - the beginning or principle of things that underlie all of reality. how the world works is that everything is derived from... Socratic Method - Teach students by asking question after question. Socrates sought to expose contradictions in the students’ thoughts and ideas to then guide them to solid, tenable conclusions. Through questioning, the questioning mind manages to find himself the truth. method of dialogue to learn questioning to gain wisdom Realm of the Forms - An ideal realm where all exists, but we can never visit Essences - component of things; the essences of things were in their observable particulars, not abstractions. Teleology - is an account of a given thing’s purpose. For example, a teleological explanation of why forks have prongs is that this design helps humans eat certain foods; stabbing food to help humans eat is what forks are for. A purpose that is imposed by a human use, such as that of a fork, is called extrinsic. [1] Natural teleology contends that natural entities have intrinsic purposes, irrespective of human use or opinion. For instance, Aristotle claimed that an acorn’s intrinsic telos is to become a fully grown oak tree. eleological cause - the end purpose; the thing that allows the thing to flourish (ex. Chalk - to write, Giraffe - to do the most special thing; what it's best suited for eating leaves from the tallest tree) Theory of Recollection - we have immortal soul where we can. nothing can be either taught or learnt as we already possess all the knowledge in the world. Socrates explains that, through the lifetime of our soul, we have already learnt all there is to learn and that we can answer every question, provided we are asked in the correct manner. Proves KNOWLEDGE IS INNATE: By using a slave and drawing a square and asking to find the area - it only proves trail - by -error --learning He goes on to prove this by getting an uneducated slave to figure out a math problem by He goes on to prove this by getting an uneducated slave to figure out a math problem by asking him a series of extremely leading questions. ie. “Is your personal opinion that the square on the diagonal of the original square is double its area?” Socrates seems convinced that he has done nothing to ‘educate’ the slave, but merely asked him the appropriate questions that allowed him to recollect. This argument for recollection is taken a step further in the Phaedo, as Plato claims there are two aspects of recollection. The first involves no lapse of time and is less a recollection of something, but more a reminder of it: “you know what happens to lovers, whenever they see a lyre or cloak or anything else their loves are accustomed to use: they recognize the lyre, and they get in their mind, don’t they, the form of the boy whose lyre it is?” The second aspect of recollection is one that does involve the lapse of time and is more familiar to the theory of recollection in the Meno. Additionally, it relates to Socrates’ goal of establishing the immortality of the soul. The argument that he lays out is that we are neither capable of learning anything new, nor were we born with the knowledge of things, but that we knew these things before our birth. Then he tries to illustrate this “theory of recollection” with the example of a geometry lesson, in which Socrates refutes a slave’s incorrect answers much as he had refuted Meno, and then leads him to recognize that the correct answer is implied by his own prior true beliefs. (Implicit true belief is another state of cognition between complete knowledge and pure ignorance.) After the geometry lesson, Socrates briefly reinterprets the alleged “recollection” in a way that can be taken as the discovery of some kind of innate knowledge, or innate ideas or beliefs. Meno finds Socrates’ explanation somehow compelling, but puzzling. Socrates says he will not vouch for the details, but recommends it as encouraging us to work hard at learning what we do not now know. He asks Meno to join him again in a search for the definition of virtue. Meno's paradox - If he does not know, then he cannot search for it. If he can search for it, then he does know and does not need to search. If you don't know about it -> how can you begin to learn/search Allegory of the Cave - “the Allegory of the Cave” in The Republic, which probably represents Allegory of the Cave - “the Allegory of the Cave” in The Republic, which probably represents Plato’s own philosophy, Socrates says that believing the evidence of our senses is ignorance and leads to immorality. Those who leave the cave and see the light – rare philosophers – are neither understood nor believed by the rest of humanity. In The Republic, this argument motivates the idea of the “philosopher king” – that only philosophers, because they have climbed out of the cave and seen reality, are fit to rule, and should be compelled to do so. This analogy is a portrayal of what it's like to be a philosopher; trying to convice people to see other perspectives and in return being considered a lunatic. This represents the philosopher’s education from ignorance to knowledge of the Forms. True education is the turning around of the soul from shadows and visible objects to true understanding of the Forms (518c-d). Philosophers who accomplish this understanding will be reluctant to do anything other than contemplate the Forms but they must be forced to return to the cave (the city) and rule it. Idealism -: a philosophical view of the world; the world only exists in our minds (minddependent, e.g, art which is subjective, beauty depending on the perceiver) - world mentally constructed, or otherwise immaterial. Subjective Idealism: "To be is to be perceived" - Doesn't Believe in the Physical World MATERIALISM & DUALISM Materialism - world consists of physical things. Mental properties are certain types of physical things Dualism - Two fundamentally dif. things : material and mental Idealists reject this picture of the world. They argue that the universe is not a collection of objects that human minds can perceive, but rather a collection of ideas that human minds can grasp. All physical objects, they say, are manifestations, or a kind of physical clothing on top of the idea. Example Example When you see a football arc through the air into the receiver’s hands, it’s following a mathematical trajectory called a parabola. Idealists would say that the ball’s path is “manifesting” the abstract idea of a parabola, so what’s really “real” is not the ball or the air or the stadium, but the ideas that all these things represent. Some idealists take a more radical position, arguing that there are no physical objects at all, only perceptions of physical objects. All idealists agree that the world around us is made of ideas – but while some argue that the ideas are part of a universal mind (e.g. the mind of God), others argue that the ideas are part of an individual mind. Most students find idealism (in either form) a little difficult to swallow – it’s so different from the way we normally think about the world, it almost seems crazy! But it’s a little easier to understand idealism if we look at the grey area in between realism and idealism. Realism - mind-independent. The things exactly exist in the world. Not dependent on humans (IF all humans are wiped out, then the realm will still exists) Ex. Plato will think that Beauty is not subjective. There is one answer, not form of Justice. Realism is a far more simple and direct idea, and nearly everyone outside of professional Realism is a far more simple and direct idea, and nearly everyone outside of professional philosophy is more of a realist than an idealist. This is most people’s common-sense view of the world. We use our senses to gather information about real objects that are around us. Those objects are really out there, and they have physical properties that we can sense – they reflect light for us to see, or they emit odor particles for us to smell. Then the mind directly connects with these objects through memory, thinking, etc. Reality is a collection of objects that we sense. Rationalism - know stuff innately. So-called "rationalists" typically think that we can attain true knowledge by analyzing our ideas, using logic to reason from common notions, and through mathematical explanations. "Rationalists" also tend to see sense perception as the main sources of error and unclarity. Rationalism is the philosophy that knowledge comes from logic and a certain kind of intuition—when we immediately know something to be true without deduction, such as “I am conscious.” Rationalists hold that the best way to arrive at certain knowledge is using the mind’s rational abilities. Math provides a good illustration of rationalism: to a rationalist, you don’t have to observe the world or have experiences in order to know that 1+1=2. You just have to understand the concepts “one” and “addition,” and then you can know that it’s true. Empiricists, on the other hand, argue that this is not true; they point out that we can only rely on mathematical equations based on some experience of the world, for example having one cookie, being given another, and then having two. Rationalism Empiricism Ex. Plato (Jason Forda in present) ex. Maybe Locke isn't an Empiricist, but we consider and Descartes --- are some, even him for the exam there are no innate ideas. one or two, innate ideas Everything we know is through experience Constructivism - concepts are constructed by society. For example, in philosophy of science, the idea is that scientific truth is socially constructed; in moral philosophy, the idea is that moral truth is socially constructed; and so on. Social constructivism appears in many fields, but these are the most common. Continuity of Consciousness - Human life runs its course in three alternating states or conditions, namely, waking, dreaming sleep, and dreamless sleep. The attainment of the higher knowledge of spiritual worlds can be readily understood if a conception be formed of the changes occurring in these three conditions, as experienced by one seeking such higher knowledge. When no training has been undertaken to attain this knowledge, human consciousness is continually interrupted by the restful interval of sleep. During these intervals the soul knows nothing of the outer world, and equally little of itself. Only at certain periods dreams emerge from the deep ocean of insensibility, dreams linked to the occurrences of the outer world or the conditions of the physical body. Identity - How we point out things are going to shape what we see in reality as a whole, so like a whole new compound (ex. Chalk and hat, when combined becomes something as whole)Personal Identity - is tied to the continuity of our concious experience. Our mind makes who we are, more so than our body Bundle Theory of Experience - For Hume, this means that the self is nothing over and above a constantly varying bundle of experiences. Matters of Fact v. Relations of Ideas --Two ways that cannot help us how the world is going to be: Relations of Ideas Matters of Fact. Relations of Ideas Matters of Fact. -> Statements either intuitvely or demonstrativley certain -> A sub-class of Cause Math and logic (Deductive reasoning) and effect - take us General rules that we apply at instances to get answers beyond the evidence of A priori- prior to experience our memory and senses Don't need to experiment, go out to the world to test - can Domain of the figure out on your own in your head sciences/experiencialy Stuff you can figure out prior to experience stuff Are Innate (stuff that Rationalists carry out) Rely on inductive reasoning - have to Rationalist - Plato and Descarte actually test Ex. Something true by definition (don't need to ask a bachelor things/experiment to if they are unmarried b/c that's what bachelor stands for ) figure out/form general Can't help tell us any interesting insight about the world: b/c rules & conclusions they are what we already know- what and how are concepts Something you cannot pick out things in the world - what is already in our heads - know prior to the what the rules of concepts (i.e math, which is a constructed experiment concept) are A posteriori - after experiment What the Empricist believes in - Berkley, Locke, Hume Cannot tell us how the world is going to be A priori - before experience A posteriori - after experience Analytic - Analytic philosophy is based on the idea that philosophical problems can be solved through an analysis of their terms, and pure, systematic logic. Many traditional philosophical problems are dismissed because their terms are too vague, while those that remain are subjected to a rigorous logical analysis. For example, a traditional philosophical problem is “Does God exist?” Various philosophical schools have proposed answers to this question, but analytic philosophy approaches it by saying, “What do you mean by God?” Different religions have wildly different ideas about what the word “God” means, so before you can approach the question of God’s existence you have to define your terms more clearly. Analytic philosophy is more interested in conceptual questions—questions about the meanings of words and statements and their logical relations–than it is in spiritual or practical issues such as morality or the meaning of life. Because of this focus, it has a reputation for being dry and technical. Analytic philosophers rely heavily on the vocabulary, assumptions, and equations of symbolic logic in their arguments. The advantage of reading analytic philosophy is that once you understand a particular author’s terms, and the vocabulary of logical analysis, their arguments should be clear and precise. You may or may not agree with what they say or find it interesting, but if you can understand their language, you should know exactly what they are saying, which is an advantage over some other philosophical schools. Unless of course, you believe that clear and precise language does not represent reality well. Analytic philosophy covers all major branches of philosophy – from social and political philosophy to metaphysics and logic. It’s defined more by its method than by any particular set of questions, arguments, or viewpoints. And its method informs most professional philosophical argumentation today to some degree, especially in America and England. An “analytic” sentence, such as “Ophthalmologists are doctors,” has historically been characterized as one whose truth depends upon the meanings of its constituent terms (and how they’re combined) alone Synthetic - “Ophthalmologists are rich,” whose truth depends also upon the facts about the world that the sentence represents, e.g., that ophthalmologists are rich. The philosopher Immanuel Kant uses the terms "analytic" and "synthetic" to divide propositions into two types. Kant introduces the analytic–synthetic distinction in the Introduction to his Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1998, A6–7/B10–11). There, he restricts his attention to statements that are affirmative subject–predicate judgments and defines "analytic proposition" and "synthetic proposition" as follows: analytic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is contained in its subject concept synthetic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is not contained in its subject concept but related Examples of analytic propositions, on Kant's definition, include: "All bachelors are unmarried." "All triangles have three sides." Kant's own example is: "All bodies are extended," that is, occupy space. (A7/B11) Each of these statements is an affirmative subject–predicate judgment, and, in each, the predicate concept is contained within the subject concept. The concept "bachelor" contains the concept "unmarried"; the concept "unmarried" is part of the definition of the concept "bachelor". Likewise, for "triangle" and "has three sides", and so on. Examples of synthetic propositions, on Kant's definition, include: "All bachelors are alone." "All creatures with hearts have kidneys." Kant's own example is: "All bodies are heavy", that is, they experience a gravitational force. (A7/B11) As with the previous examples classified as analytic propositions, each of these new statements is an affirmative subject–predicate judgment. However, in none of these cases does the subject concept contain the predicate concept. The concept "bachelor" does not contain the concept "alone"; "alone" is not a part of the definition of "bachelor". The same is true for "creatures with hearts" and "have kidneys"; even if every creature with a heart also has kidneys, the concept "creature with a heart" does not contain the concept "has kidneys". Empiricism - Empiricism in the philosophical sense is the idea that all knowledge that a person can know must come from the things they can sense; i.e. you won't know that something is the case until you can sense it in some way. In this way, knowledge that cannot be sensed directly or observed indirectly through tools is not in fact knowledge. - Everything we know is through experience. Immediate object of our perceptions are ideas - as in through our senses, which are the ideas (do not experience objects directly, but experience through filtered, represented ideas - the emotions/ideas they invoke in us) Ideas = direct experience 1. Senses- perceptions/ minds are passive Sensory ---> Simple ideas - colors, we can describe it to a blind person, but the only way to understand how the colors look like is to see it. 2. Reflections- when mind bringing forth the ideas - active, imagine things the way we never received Build up complex ideas by combining simple ideas Objects = indirectly experienced Noumenal - - world in and of itself / world out there ( World it truly is independent of our mind's perception) - The first world is called the noumenal world. It is the world of things outside us, the world of things as they really are, the world of trees, dogs, cars, houses and fluff that are really real. However, Kant says, our minds are created in such a way that we cannot comprehend this world as it really is. Instead what we perceive is like an altered version of this world which Kant called the phenomenal world. The phenomenal world is the world that we perceive or to put it another way, the view we have of the world that is inside our heads. Diagrammatically, it might look a bit like this: So why doesn’t information come cleanly into our heads from out there in the real world? Why do things get messed up on the way in? Kant’s answer is that a number of axioms, assumptions or rules (which he also called schema) are hard wired into our minds and they interact with the real (noumenal) world to help create the phenomenal world that exists inside our heads. In a sense these axioms or rules are like a filter between our minds and the real world, a bit like a man who is wearing sunglasses. The sunglasses are like the schema and they alter the way that the world really looks to create the world that exists inside our heads, as such the man with the sunglasses on will see things as blacker or darker than they really are. The important point is that our perceptions of the world don’t just come out of nowhere, they are caused by the world outside and so we are perceiving a world that really exists, but what that world looks like to us is a bit different to what that world is really like. The problem, however, is that while you can take off the sunglasses to see how bright things really are, you can never take the rules, axioms, assumptions or schema out of your mind in order to find out what the world outside of your head is really like. So Kant creates an unbridgeable gap between the world out there as it really is, the noumenal world, and the world as we perceive it, the phenomenal world inside our heads. Phenomenal - the world as we perceive it, the phenomenal world inside our heads. Skepticism - promote doubt, the suspense of judgment, and the confinement of inquiry to within narrow bounds. Originally, in ancient Greece, skepticism was the philosophy of questioning all claims, religious, ethical, scientific, or otherwise. The point of skepticism was not so much to disbelieve claims, but to "I think therefore I am" - Cogito Ergo Sum - Descartes Descartes turned, in the "Meditations on First Philosophy" to solipsism: the methodical doubting of the senses. He asked, kinda, "How can we be sure we aren't dreaming? How can we be sure we aren't being deceived by a demon?" He reasoned that we've all had incredibly realistic dreams, and that some of those dreams, while being dreamed, were indistinguishable from reality. How, then, can we trust our senses? Well, he dug a little deeper, and determined (quite logically, in my opinion) that we cannot be deceived into thinking that we're thinking -- thought alone is sufficient to guarantee existence. Nothing can deceive us into thinking that we're thinking if we are unthinking things. So by the virtue of thought, we guarantee our existence. Thus the "I think therefore I am" argument. "I think therefore I am"- Demon cannot deceive him of that; to be deceived is to have a thought. "One thing for certain- There has to be thought in reality, cannot doubt that aswe know that for certainty" A statement by the seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes. “I think; therefore I am” was the end of the search Descartes conducted for a statement that could not be doubted. He found that he could not doubt that he himself existed, as he was the one doing the doubting in the first place. In Latin (the language in which Descartes wrote), the phrase is “Cogito, ergo sum.” If you read the above quote from the Meditation II you see that Descartes has disproved everything that he is used to believing in. When there’s nothing left he still is left with himself and nothing else. Regardless of whether or not he is being deceived by some demon or his beliefs are wrong, he is able to see that even if he has the ability to doubt something he must be existing to even doubt it in the first place. The fact that he can think is what assures himself of his own existence, and a deceiving god cannot negate that. From this point on, Descartes can continue in his examination of reality without worry that he is by all means existing. “I Think, Therefore I am” is used in most intro classes to gets across the real meaning of what the cogito (Meditation II) means — A deceiver can’t deceive me of my existence, for if he were the cogito (Meditation II) means — A deceiver can’t deceive me of my existence, for if he were I wouldn’t exist! However, even the Evil Genius cannot deceive me that I have certain thoughts: – Yes, I can be wrong about there being a hand in front of me: • I think there is a hand • … But there is no hand • … no contradiction there – However, I can’t be wrong about having thoughts: • I think I have thoughts • … But I have no thoughts • … but wait: if I think I have thoughts, I do have a thought! • Cogito Ergo Sum! I think, therefore I exist! • What is the ‘I’? – A thinking entity: a mind! Primary and Secondary Qualities - Two Types of Qualities: 1. Primary - are objective, truly in/parts of the objects 1. Figure - shape 2. Number - Rate 3. Extensions - solidity 4. Motion 2. Secondary - (Sensory) are subjective - change the subjects and they experience the secondary qualities differently - observer relative (diff. observers have diff. experience depending on the environment ---> How we see things, feel things) 1. including color, smell, and taste Dualism - Two fundamentally dif. things : material and mental - man is body and mind- mental events are correlated with physical events. Human beings are material objects. We have weight, solidity and consist of a variety of solids, liquids and gases. However, unlike other material objects (e.g. rocks) humans also have the ability to form judgments and reason their existence. In short we have 'minds'. Typically humans are characterized as having both a mind (nonphysical) and body/brain (physical). This is known as dualism. Dualism is the view that the mind and body both exist as (physical). This is known as dualism. Dualism is the view that the mind and body both exist as separate entities. Descartes / Cartesian dualism argues that there is a two-way interaction between mental and physical substances. Descartes argued that the mind interacts with the body at the pineal gland. This form of dualism or duality proposes that the mind controls the body, but that the body can also influence the otherwise rational mind, such as when people act out of passion. Most of the previous accounts of the relationship between mind and body had been uni-directional. Monism -- rejects any splitting of man into parts - is viewed as an unified organism. They believe that the mind is part of the body — that consciousness is produced entirely by the central nervous system, and that the self exists entirely in the material world. There are two basic types of monism: Materialism Materialism is the belief that nothing exists apart from the material world (i.e. physical matter like the brain); materialist psychologists generally agree that consciousness (the mind) is the function of the brain. Mental processes can be identified with purely physical processes in the central nervous system, and that human beings are just complicated physiological organisms, no more than that. Phenomenalism Phenomenalism (also called Subjective Idealism) believes that physical objects and events are reducible to mental objects, properties, events. Ultimately, only mental objects (i.e. the mind) exist. Bishop Berkeley claimed that what we think of as our body is merely the perception of mind. Before you reject this too rapidly consider the results of a recent study. Scientists asked three hemiplegic (i.e. loss of movement from one side of the body) stroke victims with damage to the right hemispheres of their brains about their abilities to move their arms. All three claimed, despite evidence to the contrary in the mirror in front of them, that they could move their right and left hands equally well. Further, two of the three stroke victims claimed that an experimental stooge who faked paralysis (i.e. lack of movement) of his left arm was able to move his arm satisfactorily. Mind/Body Problem -The mind and body problem concerns the extent to which the mind and the body are separate or the same thing. The mind is about mental processes, thought and consciousness. The body is about the physical aspects of the brain-neurons and how the brain is structured. Is the mind part of the body, or the body part of the mind? If they are distinct, then how do they interact? And which of the two is in charge? They argue that the brain can be compared to computer hardware that is "wired" or connected to the human body. The mind is therefore like software, allowing a variety of different software programs: to run. This can account for the different reactions people have to the same stimulus. to run. This can account for the different reactions people have to the same stimulus. This idea ties in with cognitive mediational (thinking) processes. In computer analogies we have a new version of dualism which allows us to incorporate modern terms such as computers and software instead of Descartes "I think therefore I am" Proved that there's a Mental Mind (soul, our mind that is impenetrable, invulnerable, helps us get the stuff that cannot be proven by science, like religious stuuf like God/Free will) and Physical Body (Science describes our physical stuff - laws and rules of science) Allows Descartes to have his cake and eat it too, becasue we can have both the spiritual and the physical stuff/ So, how can we tell our mind what we do (our physical body)? The mindbody problem. Descartes ans: Pinial gland- has a magical part His student's ans: My mind is praying to God (has a connection to God, God then moving my limbs Carestian Circle Problem: Descartes basically gives us a circular argument: Clear Disticnt Perception Our mind-body problem is not just a difficulty about how the mind and body are related and how they affect one another. It is also a difficulty about how they can be related and how they can affect one another. Their characteristic properties are very different, like oil and water, which simply won’t mix, given what they are. Our body and mind seem to be intimately connected: – When I hit your foot with hammer, you will feel pain. – When you decide to raise your hand, you do it • But what exactly is this connection between our body and mind? Why is there such a connection? How does it work? – Is the mind part of our body? Is it simply our brain? • We know that changes in our brain result in changes to our mind. • But does that really make them the same? It certainly seems very strange to say that our mind weighs 3 pounds (like our brain does)! – Or is our mind the way our body behaves? • We often judge that someone has certain mental abilities (and hence has a mind) by their behavior. • But does that make them the same? Most of us think that behavior is a result of our mind, not part of it! To understand the difference between monism and dualism, it might help to focus on one particular aspect of the mind: consciousness, or the mind’s ability to examine its own particular aspect of the mind: consciousness, or the mind’s ability to examine its own processes in real time. Consciousness is arguably the most important aspect of the human mind — without it, would we even be human at all? Monists and dualists have opposite views on consciousness. Dualists Monists The mind is separate from the body. Consciousness The mind is part of the body. is a state of mind that can’t be understood purely in Consciousness can be terms of the body. In order to understand understood as a function of the consciousness, we have to examine abstract logic human brain, and therefore the and/or use faith — studying the brain is not enough. best way to understand it is to study the brain. Among modern philosophers, monism is generally more popular than dualism. However, dualism has been more popular historically, and the logical problems here are far from settled — it remains to be seen whether dualism can make a comeback. Materialism - In more modern times, and influenced by the worldview that modern science provides us with, more and more people believe that the mind is simply part of the physical universe. Materialism: there is only ‘physical stuff’ • Mental ‘stuff’ is either an illusion, or the product of physical stuff (e.g. an abstraction, or combination, of physical stuff) Inductive and Deductive Reasoning - Deductive (General to specific; ex. From general rules/formulas, you solve specific math problems) vs. Inductive (specific instance to form a general conclusion; ex. On, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday; saw a white swan, Inductive reasoning - all swans are white or Since I like milk, everyone else likes milk) Aristotle based Inductive reasoning for his thoughts So Descartes wanted to use deductive reasoning - wants to get back our sense, hence needs to prove the existence of God. Now his argument gets shaky needs to prove the existence of God. Now his argument gets shaky Most everyone who thinks about how to solve problems in a formal way has run across the concepts of deductive and inductive reasoning. As with all my tutorials, the purpose of this article is to explain the differences between these two approaches as clearly as possible. Both deduction and induction are often referred to as a type of inference, which basically just means reaching a conclusion based on evidence and reasoning. First, both deduction and induction are ways to learn more about the world and to convince others about the truth of those learnings. None of these terms would mean anything or are useful to anyone if they weren’t used to do something useful, like determining who committed a crime, or how many planets might harbor life in the Milky Way galaxy. Induction and Deduction help us deal with real-world problems. The biggest difference between deductive and inductive reasoning is that deductive reasoning starts with a statement or hypothesis and then tests to see if it’s true through observation, where inductive reasoning starts with observations and moves backward towards generalizations and theories. Key points Deduction moves from idea to observation, while induction moves from observation to idea. Deduction moves from more general to more specific, while induction moves from more specific to more general. Deductive arguments have unassailable conclusions assuming all the premises are true, but inductive arguments simply have some measure of probability that the argument is true—based on the strength of the argument and the evidence to support it. All men are mortal. Harold is a man. Therefore, Harold is mortal. Deduction This third sentence is absolutely true because (if) the first two sentences are true. I have a bag of many coins, and I’ve pulled 10 at random and they’ve all been pennies, therefore this is probably a bag full of pennies. Induction This gives some measure of support for the argument that the bag only has pennies in it, but it’s not complete support like we see with deduction. Deduction has theories that predict an outcome, which are tested by experiments. Induction makes observations that lead to generalizations for how that thing works. Induction makes observations that lead to generalizations for how that thing works. If the premises are true in deduction, the conclusion is definitely true. If the premises are true in induction, the conclusion is probably true. There’s another type of reasoning called Abductive Reasoning, where you take a set of observations and simply take the most likely explanation given the evidence you have. Deduction is hard to use in everyday life because it requires a sequential set of facts that are known to be true. Induction is used all the time in everyday life because most of the world is based on partial knowledge, probabilities, and the usefulness of a theory as opposed to its absolute validity. Deduction is more precise and quantitative, while induction is more general and qualitative. Examples If A = B and B = C, then A = C. Deduction … Since all squares are rectangles, and all rectangles have four sides, so all squares have four sides. Deduction … All cats have a keen sense of smell. Fluffy is a cat, so Fluffy has a keen sense of smell. Deduction … Every time you eat peanuts, your throat swells up and you can’t breathe. This is a symptom of people who are allergic to peanuts. So, you are allergic to peanuts. Induction … Ray is a football player. All football players weigh more than 170 pounds. Ray weighs more than 170 pounds. Induction … All cars in this town drive on the right side of the street. Therefore, all cars in all towns drive on the right side of the street. Induction We can see here that deduction is a nice-to-have. It’s clean. But life is seldom clean enough to be able to apply it perfectly. Most real problems and questions deal more in the realm of induction, where you might have some observations—and those observations might be able to take you to some sort of generalization or theory—but you can’t necessarily say for sure that you’re right. It’s about working as best you can within a world where knowledge is usually incomplete. Summary 1. Deduction gets you to a perfect conclusion—but only if all your premises are 100% correct. 2. Deduction moves from theory to experiment to validation, where induction moves from observation to generalization to theory. 3. Deduction is harder to use outside of lab/science settings because it’s often hard to find a set of fully agreed-upon facts to structure the argument. 4. Induction is used constantly because it’s a great tool for everyday problems that deal with partial information about our world, and coming up with usable conclusions that may not be right in all cases. 5. Be willing to use both types of reasoning to solve problems, and know that they can often be used together cyclically as a pair, e.g., use induction to come up with a theory, and then use deduction to determine if it’s actually true. 6. The main thing to avoid with these two is arguing with the force of deduction (guaranteed to be true) while actually using induction (probability based on strength of evidence). *Means that these philosophers will not be tested in as great detail as the others. 1. How did it all get started? 1. The Intellectual Shift 1. mythos - story, narrative, mythos 2. logos - argument, account, explanation 2. The Social/Political/Historical Context 1. Where? Hellas. (Greece) 2. When? - 7th Century BCE 1. Egypt - 26th Dynasty/3rd IP 2. Judea – destruction of Jerusalem/Babylonian Captivity (587 BCE) Zephaniah, Jeremiah, Daniel 3. Mesopotamia – Fall of Assyria (612 BCE)/Rise of Neo-Babylonian Empire (Nebuchadnezzar II) 4. Persia – Cyrus the Great (559-530 BCE), Zoroastrianism 5. India - completion of the Upanisads; Siddhartha Gotama (c. 563 – c. 483 BCE) and the Buddhist reformation 6. China - Lao Tzu (born c. 604 BCE) composes the Tao Te Ching; K'ung-fu-tzu (551-479 BCE) composes the I-ching and Analects 3. WHY? - What's so different about Greece? 1. Geography 2. Economy 3. Politics 2. The First Philosophers ("Pre-Socratics"): ("Pre-Socratics"): 1. What is the substance of things? 1. Thales (c. 585 BCE) - all things are “water” 2. Anaximander (c. 580 BCE) – all things come from the “infinite” (ton apeiron) 3. Pythagoras (c. 571 BCE) - all things are made of ”numbers” 4. Democritus (c. 460 BCE) - all things are made of “the indivisible” (atom) 2. What is the nature of Nature? 1. Change - Heraklitos (c. 500 BCE) - all things are in motion 2. Permanence - Parmenides c. 485 BCE – all things are one 3. The Complete Text of the Apology 1. Two Kinds of Charges: 1. The Informal Charge 1. Aristophanes ("The Clouds") "Sokrates is guilty of criminal meddling, in that he inquires into things below the earth and in the sky, and makes the weaker argument defeat the stronger, and teaches others to follow his example." 1. Investigation of the physical world 2. Intentional use of bad reasoning 3. Sokrates is a Sophist (i.e., he takes money for teaching others how to use bad reasoning) This "informal" charge is inadvertanly brought on by Aristophanies and his play "The Clouds." The character "Sokrates" in that play is precisely this kind of nature philosopher! The problem for the real Sokrates is to convince the jury that he bears little resemblance to the character of the comedy. 2. Sokrates' Defense: 1. He does not speculate about the natural world 2. He accepts no money, and the young follow of their own will Having claimed that he is not guilty of either set of charges, Sokrates offers Having claimed that he is not guilty of either set of charges, Sokrates offers an alternative account of why Meletus, Anytus and Lycon have brought these charges against him. 2. The Oracle at Delphi 1. The Riddle 1. Sokrates believes he has no significant wisdom 2. The Oracle (for Apollo) says "no one is wiser than Sokrates" 3. It's inappropriate for God to lie 2. Sokrates' Investigation of the Riddle: (elegxos pronounced elenchos) 1. The Politicians 2. The Poets 3. The Craftsmen Sokrates discovers that none are wise concerning virtue, and in the process of his investigation he makes enemies by publically demonstrating that those who claim to be wise are not. Thus, the real reason he's been brought before the court is because he's made enemies in all parts of the community by exposing those who pretend to be wise when they are not. 3. The Formal Charge 1. The Affidavit sworn by Meletus: "Sokrates is guilty of corrupting the minds of the young, and of believing in deities of his own invention instead of the gods recognized by the state." 1. Corrupting the youth 2. Introducing new gods 2. Sokrates' Defense: Sokrates cross-examines Meletus 1. Sokrates can not intentionally corrupt the youth 2. Sokrates can not be an atheist Both of these arguments against Meletus are excellent examples of Sokrates' Both of these arguments against Meletus are excellent examples of Sokrates' method of argument called 'elegxos' in Greek, or "cross examination." Notice that Sokrates himself does not put forward any specific claims, but merely uses the claims of Meletus to demonstrate an inconsistency in the prosecutor's case. This seems to be the way Sokrates always argues with his opponents. If we look at other dialogues from Plato's Socratic Period, we find Sokrates using the same style of argument. This allows him to claim that he does not have significant wisdom on one hand, while at the same time also claiming that his interlocutor doesn't have significant knowledge either! The elegxos is quite different from what is commonly called the "Socratic Method" which we will see demonstrated in Plato's dialogue the Meno. There we will see Sokrates guiding his interlocutor to the correct answer through a series of leading questions. This is sometimes also referred to as the dialectic method of argument. The dialectic method, however, is probably a platonic invention and not part of Sokrates' style of Philosophy. It is therefore a misnomer to call it the Socratic Method. 2. Sokrates is commanded by Apollo to DO Philosophy 3. The Verdict: Guilty 4. The Sentence: In the courts of Athens, the prosecution would suggest one puninshment and the defense would offer a counter punishment. Then the jury would decide between them. Meletus, for his part, has put forward the death penalty, so it's Sokrates' turn to offer a counter penalty. 1. Maintaince at the Prytaneum, or 2. Fine (one minae = aproximately six months of wages; bumped up to 30 minae at the behest of Sokrates' friends) This is an important, and very interesting, part of the trial. Sokrates has been found guilty by a narrow margin, which likely means that he can sway the jury to leniency in the penalty phase. So Sokrates begins his address to the jury by suggesting lifetime maintaince at the Prytaneum. The Prytaneum is the place in Athens where former victors of the Olympic games received daily rations of food, this is the reward they received from the city for their victory. In essence, Sokrates has suggested as his penalty free meals for the rest of his life! It is clear that he doesn't think he will get this because he quickly goes on to explore banishment, which he rejects, then a monetary fine. We have to ask ourselves, why did Sokrates do this? The effect it has on the jury is obvious; when the second vote is taken, some of those who had voted to acquit Sokrates a moment before, now voted to put him to death. One possible explaination, the one given by Xenophon in fact, is that Sokrates is trying to get himself killed. But this seems inconsistent with everything else we know about Sokrates. I think a better explanation is that Plato is showing us that Socrtates is a flawed character. He is not perfect, and his sarcasm sometimes gets the better of him. The matter is open for interpretation, however, and you must struggle with this question and come to an answer for yourself. 5. Sokrates accepts death: 1. Sokrates' divine voice did not stop him 2. Death ought not to be feared because it can only be one of two things: 1. Either death is an annihilation of the soul (everlasting unconsciousness) 2. Or, death is a migration of the soul from this world to another. 3. If death is an annihilation of the soul, then it is like a dreamless sleep. 4. A dreamless sleep is good (or at the very least, it cannot be bad). 5. (C1) Therefore, if death is like a dreamless sleep, death is good 6. If death is a migration of the soul from the world of the living to the world of the dead, then Sokrates can philosophize with the souls of the dead. 7. It would be good for Sokrates to philosophize with the souls of the dead. 8. (C2) Therefore, if death is a migration of the soul, death is good 9. If death is either an annihilation or migration of the soul, then it is good. 10. If death is good, it ought not be feared. 11. Death is either an annihilation or migration of the soul. 12. (C3) Therefore, death ought not be feared. 6. What is 'Philosophy' for Sokrates? 1. A way of life 2. A search for: 1. wisdom, which is ... 2. knowledge of good and bad, that teaches us ... 3. the right way to live In other words, Philosophy is not a pastime, or sport, or mere entertainment. It is something one does with the whole being. It is, for Sokrates at least, the most important way to live one's life. 4. John Locke is neither a skeptic nor a relativist; he believes that there are facts about the world, and we can know many of them. This assumption makes it essential that we know the difference between believing and knowing. This is what Locke is attempting to do in his Essay. Articulating the distinction between knowledge and opinion, we are led to a discussion of the rules of believing and knowing, and more importantly, the necessity of evidence for formulating and maintaining beliefs and knowledge. It is not enough to simply WANT something to be true, we must have REASONS for our beliefs. This is the subject of Chapter 19 of Book Four, which Pojman has entitled, "Philosophy as the Love of Truth versus Enthusiasm." 1. What is The Value of Truth (i.e., knowledge) 1. Instrumental Value - Good for the sake of something else (e.g., what we can do with it) 2. Intrinsic Value - Good for its own sake NOTE: The sign of the genuine philosopher is loving truth for its own sake, not for the sake of what we can do with it, or what it can do for us. 2. What Counts as Evidence for Belief Justification? (four possible grounds of assent) 1. Reason - "Nature’s Revelation" 1. Self-evident beliefs (i.e., tautologies and definitional truths) 2. That which can be deductively demonstrated (i.e., the rules of logic and mathematics) 3. That which can be inductively inferred (i.e., all empirical knowledge) 2. Divine (special) Revelation "discoveries communicated by God immediately" NOTE: To understand Locke's position it is essential to understand that revelation is an "enlargement" of rational knowledge, but it can never be contrary to reason. Divine revelation cannot contradict reason, because God is a rational being. In fact, God is the rational being. What we call reason just is a reflection of how God thinks. Thus, it cannot be revealed that 2 + 2 = 5, or that squares have three sides, or anything which is a contradiction of the principles of reason. Another way of saying this is, God cannot contradict himself. So, one way we test a revelation to see if it is genuine is by comparing it to what we know through reason. A revelation must be consistent with reason. The second test for a legitimate revelation is whether the belief is something we could come to know on our own. Since God has equipped us with natural abilities (senses and the faculty of reason), he expects us to use those tools to investigate the world. When God gives us a revelation, it must be a truth that transcends our ordinary capacities of knowledge. If someone claims as revelation something that is within our ordinary powers, we know it is not genuine. Thus, genuine revelation must not contradict reason, while it exceeds our ordinary abilities of knowing. But given that we are rational by nature (i.e., made in God’s image) we will be dubious of any belief that is not sufficiently supported by evidence. Knowing this, God, when he gives us a revelation, always provides objective evidence that the revelation is genuine. That evidence is what people commonly call a miracle: an observable event which transcends our ordinary capacity for understanding without violating the rules of reason. 3. Authority- believing what someone says simply because THEY are the one who said it 4. Enthusiasm - believing what we want to believe, when there is no other evidence other than our desire to believe it Of the four possible types of evidence for a belief, only two —reason and revelation—are reliable. For Locke, the truth will always be accompanied by sufficient evidence. Our job, the job of doing Philosophy, is to uncover that evidence. And if that evidence is not forthcoming, we ought to withhold our assent, even if it's a proposition we desperately want to be true. 5. We have thus far been concerned with the ancient Greeks and how they thought of philosophy. But as we saw in the introductory material, for them there was no real distinction between Philosophy and Natural Science. For us, on the other hand, there is a distinction between Philosophy and the other sciences--even if it is an artificial one. So we should again ask our question (What is Philosophy?) taking the Modern distinctions into account. 1. The Difference between Science and Philosophy 1. The Scope of knowledge: Universal versus Individual 2. The Type of knowledge: "Practical " versus Theoretical 3. The Method of knowledge: Division versus Unity 4. The Result of knowledge: Certainty versus Uncertainty 2. The Value of Philosophy: Why Philosophy Ought to be Studied: 1. It Creates an Enlargement of the Self Beyond . . . 1. common sense (egocentrism - the failure to see beyond oneself) 2. family (familiocentrism- the failure to see beyond one’s family beliefs) 3. culture (ethnocentrism- the failure to see beyond one’s cultural beliefs) 4. species (athropocentrism - the failure to see beyond one’s species beliefs) 2. It Makes Possible a Reevaluation of the Self in relation to the Not-Self 2. It Makes Possible a Reevaluation of the Self in relation to the Not-Self 1. Contemplation of the Non-Self 2. The Struggle for Objectivity 3. Philosophical contemplation can, indirectly, influence the "real world" 1. How we feel about the world 2. How we act in the world 6. I. Introduction to Epistemology: An Overview 1. Three Central Questions: 1. What is knowledge? (What‘s the difference between knowledge and opinion?) 2. Can we have knowledge? (Are humans capable of knowing anything?) 3. How do we get knowledge? (What‘s the process by which knowledge is 3. How do we get knowledge? (What‘s the process by which knowledge is obtained?) 2. Three Preliminary Answers: 1. What is Knowledge? 1. beliefs which are 2. true 3. for which we can give sufficient justification 2. Can we have knowledge? 1. Skepticism - "No!" 2. Dogmatism - "Yes!" 3. How do we obtain knowledge? 1. Rationalism - through rational reflection on ideas alone 2. Empiricism - through the senses alone 3. Two Kinds of Belief/Knowledge: Since Knowledge is composed of beliefs, it will be important, as we shall see later, to determine the source of our beliefs and how they are transformed into knowledge. Generally speaking, we can draw a distinction between two types of beliefs and knowledge based on how they are aquired. 1. a priori - (Lt. “from before”) knowledge/beliefs that require no experience 2. a posteriori - (Lt. “from after”) knowledge/beliefs that require some experience II. The Three Essential Elements of Knowledge Expanded 1. Beliefs -higher order cognitive states that are justifi able, but not yet certain 1. Hunch/Intuition (no justification possible) 2. Opinion/belief (justified to some degree, but not certain) 2. Truth - beliefs that correspond with reality ( the way the universe is ) are true, otherwise they are false Note: Remember that only beliefs about the world have a truth-value assignment. Thus, evaluative and aesthetical beliefs are not in themselves usually thought to be true or false. For example, it might be true that you think blue is a preferable color than red, false. For example, it might be true that you think blue is a preferable color than red, but it is not true that blue is prettier than red (because ‘prettier’ is an aesthetical judgment, not a claim about the world). 3. Justification - the evidence which demonstrates a connection between our beliefs and the world 1. Internalism: Justification rests upon a belief's relation to other beliefs 1. Foundationalism - some beliefs are terminal (or self-justifying), all others are derived from them 2. Coherentism - all beliefs are justified by their relations to other beliefs; no terminal beliefs 2. Externalism: Justification rests upon the way a belief is formed; the right process of belief formation gives justification (Cognitive Science - 'right' brain states) 4. Expanding our Preliminary Answers - Can we have knowledge? 1. Three possible answers: 1. Dogmatism - we can have knowledge 2. Skepticism - we can’t have knowledge 3. Relativism - it’s all knowledge 2. Dogmatism: 1. Extreme Dogmatism - Anyone can know any/everything. 2. Mitigated Dogmatism - Some people know some things. 3. Skepticism: Two varieties 1. Extreme Skepticism - No one can know anything. This position maintains that knowledge is, in principle, impossible to attain. That is, it is impossible to be certain that our beliefs meet the criterion of truth. Thus we have no knowledge. 2. Mitigated Skepticism - No one actually knows anything. 4. Relativism - what is true is 'true' for you 1. Extreme Relativism - truth is relative to each individual 2. Mitigated Relativism -truth is relative to the family, culture, group, historical period, etc., in which you live 3. The Problem with Relativism: it leads to logical inconsistencies and/or contradictions (and anything follows from a contradiction) 7. The Republic and the Theory of Ideas: 1. Justice in the State 1. Producers 2. Warriors 3. Rulers 2. Education in the State: 1. Sense-Lovers - (producers and warriors) 1. Focus on the senses 2. Particulars - the objects of the senses 3. Truth Lovers - (Rulers/Philosophers) 1. Focus on Ideas (eidos) 2. They grasp the Universals - the one that stands over the many (the cause of the particular's appearance) 4. Plato’s Ontology: 1. Being - that which exists without qualification 2. Non-Being - the absence of existence 3. Becoming - that which exists with qualification (i.e., subject to change) 5. The Divided Line : Plato's Picture of What can be Known 1. The World of Being - Reason 2. The World of Numbers - Intelligence 3. The Physical World - Opinion 4. Images of the Physical World - Imagination 6. Allegory of the Cave 8. The Theory of Recollection from the Meno 1. Meno's Paradox: 1. Either we already have knowledge (and therefore don‘t need to look for it), or 2. We don't have, nor can we look for, knowledge (because we don’t know what we’re looking for) 2. Sokrates' Solution: the immortal soul hypothesis P1) If the soul is immortal, it has always existed. P2) If the soul has always existed, there is nothing which the soul would not be acquainted with. Conclusion) Therefore, if the soul is immortal, then it knows all things (we don’t learn, we recollection). 3. Proof for the theory of Recollection - The Slave Boy: 1. Begins confident in his knowledge (like the Athenians, like Meno) 2. Cross-examination demonstrates he only has opinion, not knowledge (aporia Sokrates' Mission to Athens) 3. After recognizing his ignorance he is prepared for the process of recollection Renaissance--- REVIEW 1. Renaissance is a period of radical social and intellectual change 2. Three major revolutions of the period: 1. Astronomical or scientific – geocentric to heliocentric model 2. Geographical – rejection of theocentric geography and the birth of colonialism 3. Theological – the fragmentation of Christianity 3. The rise of Skepticism Rene Descartes (1596-1650): The Father of Modern Philosophy 1. Rene Descartes’ Response to Skepticism 1. Descartes' Accomplishments: 1. Optics - How We See 2. Mathematics - Cartesian Coordinate System 3. Philosophy - What and How we Know 2. Meditations on First Philosophy - a summary of Cartesian Philosophy 1. Descartes' Project 1. Identify and eliminate false beliefs 2. Demonstrate how to move from true beliefs to *knowledge* 2. A Structural Overview of The Meditations: 1. Meditation I: How to recognize true beliefs 2. Meditation II: Some beliefs cannot be false 3. Meditation III: Proof of the existence of God 4. Meditation IV: Why do we make mistakes? 5. Meditation V: The essence of things 6. Meditation VI: Proof of dualism; the mind/body distinction 3. Meditation I : What Can be Doubted or How to get Rid of False Beliefs 1. The Problem - We grow up believing many false things, and we base other beliefs on the false ones. 2. The Solution - Find a way to distinguish true from false beliefs (Methodological Skepticism) Note: Two Necessary Conditions for an Adequate Truth Rule: The *Truth* Criterion - property appealed to must never belong to a false belief The *Recognizability* Criterion - the property appealed to must be recognizable to ordinary cognizers Possible Truth Rules: TR 1: Accept as true any belief that has been acquired through direct or indirect sensory experience. Objection: Illusions and Hearsay TR 2: Accept as true any belief that has been acquired through direct sensory experience under uniform or ideally favorable external conditions. Objection: Insanity or Hallucinations TR 3: Accept as true any belief that has been acquired through direct sensory experience under uniform or ideally favorable external and internal conditions. Objection: Dreams TR 4: Accept as true any belief that has been acquired through direct sensory experience under uniform or ideally favorable external and internal conditions when one is not asleep. Objection: We cannot distinguish between dreaming and waking TR 5: Accept as true those general beliefs based on sense experience that are about the simple sensible objects and that are necessary in order to have the experience we have in our dreams. EXAMPLES: color extension shape ("figure") quantity or magnitude time Objection: The Evil Demon (or brain in a vat Hypothesis) 1. Meditation II : Response to the Sceptical Hypothesis 1. Consequences of the Skeptical (Evil Genius) Hypothesis: 1. all our sense data could be false 2. all our memories could be false 3. there might be no external universe 2. Necessary existence of the self Cogito Ergo Sum: Thinking requires a thinker Even if there is an Evil Genius who deceives me about everything else, there must be an 'I' to be deceived. Either I am deceived and I exist, or I am not deceived and I an 'I' to be deceived. Either I am deceived and I exist, or I am not deceived and I exist. Therefore, I must exist (or, even if I can doubt all else, I cannot doubt that I exist). 1. 'I' refers to the thinker (*whatever* it is that is thinking) 2. If there is thinking*, there is a think**er***. 3. I am a thinking thing (the substance of the soul is thought) 3. Representationalism - The TV Screen Theory of Perception 2. Meditation III : How God Secures our Knowledge TR 6: Accept as true every belief that is *clearly* and *distinctly* believed Question: Does this rule meet the necessary conditions for a TR? 1. Evaluation of TR 6: 1. Can we recognize clear and distinct Ideas? YES 2. Are clear and distinct Ideas True? YES, if and only if 1. God exists, and 2. God is not a deceiver 2. Descartes' Argument for the Existence of God 1. Three kinds of Ideas in the mind: 1. Innate (those I discover within myself) 2. Adventitious (those I get accidentally) 3. Invented (those I create for myself) 2. Theory of Perception - Representationalism (the TV screen theory) 3. Descartes’ Ontological Hierarchy - 1. Formal Reality - common to all existing things 2. Objective Reality - belongs to things which represent other things 4. The Argument for God's Existence: P1) I have an idea of God; P2) The idea 'God' is of a perfect being. P3) the cause of the idea must have an equal or greater amount of *formal reality* than the idea has *objective reality* P4) The idea 'God' has more *objective* reality than I have formal reality Conclusion 1) Therefore, I am not the cause of my idea of 'God' P5) Since I am not the cause of my idea 'God' there must be some cause of it outside myself. P6) Only a being with perfect *formal* reality could cause the idea of a perfect being in my mind. Conclusion 2) Therefore, God, the perfect being, exists outside my mind. Conclusion 2) Therefore, God, the perfect being, exists outside my mind. 3. John Locke (1632-1704): An Empirical Response to Descartes' Rationalism 1. Historical Background - 1. Renaissance Revolutions and Skepticism 2. The English Civil War 1642-1646 (Charles I vs. Parliament) 3. Thomas Hobbers (The Leviathan) - Metaphysical Materialism 2. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding 1. Goals of the essay: 1. Identify where our ideas come from. 2. Determine how knowledge is derived from ideas. 3. Determine how much credence we should give to ideas that don't qualify as knowledge. 2. The Weakness of Rationalism: Innate ideas 1. The Argument from Simplicity (Ockham's Razor) 2. The Argument Against Universality: P1) If annate ideas exist, then they are in the souls of all persons. P2) It is not the case that innate ideas exist in all souls. P2) It is not the case that innate ideas exist in all souls. Conclusion) Therefore, innate ideas do not exist. 3. The Alternative Origin Argument (Empiricism*) P1) If an alternative account of how 'innate' ideas are acquired can be provided, then no ideas need not be considered innate. P2) We can provide an alternative account of how we acquire all our ideas. Conclusion) Therefore, we do not need the hypothesis of innate ideas. 3. Developing Empiricism - If there are no innate ideas, where do our ideas come from? 1. The Empirical Hypothesis - the mind begins as a blank slate (tabula rasa) 2. Sensationn - the mental experiences (sense data) caused in us by external objects 3. Reflection - the mind's operations on recorded sense data (e.g., ordering, comparing, thinking, doubting, believing, etc.) 4. Ideas - abstractions drawn from mental reflection on sense data (e.g., color, shape, time, space, goodness, etc.) 5. Knowledge - the systematic organization of appropriately acquired ideas 4. How Ideas are created in the mind NOTE: If there are no innate ideas and our minds begin as a blank slate, then all sensations and ideas must be created in us by an outside source. There are two possible outside sources: God - special revelation Nature - natural revelation (i.e., the five sense) 1. The Primary Qualities of Objects - those qualities that cannot be separated from the object itself 1. extension - it occupies space 2. shape - the limit of extension 3. motion - alteration of location 4. solidity - two bodies cannot co-locate 5. number - how many there are 2. The Secondary Qualities of Objects - the effects of the primary qualities in our minds 1. sights 2. sounds 3. tastes 4. smells 5. feels NOTE: The substance which contains the primary qualities is matter. The Water Bucket Argument - how to prove the distinction between primary and secondary qualities secondary qualities David Hume (1711-1776): Empiricism - The Next Generation 1. Intellectual Background: 1. John Locke - 1. no innate ideas, 2. ideas derived from sensation, 3. distinction between primary and secondary qualities, 4. existence of matter 2. George Berkley - 1. no distinction between primary and secondary qualities, 2. esse est percepi - *im*materialism 2. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding 1. Hume's Distinction between the things in the mind 1. Impressions (i.e., sensations) - lively, immediate, strong 1. sensory data 2. emotions 3. desires/will 3. desires/will 2. Thoughts (ideas) - less forceful, mediated, dependent 1. compounds 2. abstractions 3. imagination 3. Two Arguments for this distinction: 1. The atomic nature of Ideas - copies of, or a composite of copies of sensations (e.g., God) 2. The necessity of impressions for ideas 2. The Shperes of Human Reason (i.e., knowledge) 1. The Relations between Ideas - the logical organization of ideas in the mind 1. Evidence - pure reason (logical relations) 2. demonstrable and certain 3. Examples: Geometry, Arithmetic, Algebra, tautologies, analytic propositions Note: These are 'certain' in that it is impossible even to conceive the contrary of the propositions (e.g., 'square circles'). 2. Matters of Fact - everything that does not fall into the previous category (the contrary of every factual proposition is logically possible) factual proposition is logically possible) 1. What counts as evidence? - Cause and Effect 2. The Problem of Induction - How do we determine causation? 1. not a priori - Billiard Ball (every effect is distinct from its cause) 2. not a posteriori - past effects do not determine future effects (the same phenomena may give rise to different consequences in the future) 3. There exists *no idea of causation*, only the mental habit of expecting the Constant Conjunction of Phenomena in the mind. 3. The Consequences of Hume's View: Skepticism 1. We can 'know' only those things which can be demonstrated. 2. Matters of fact are only believed because of our experience with constant conjunction 3. We have no 'knowledge' of matters of fact.