Improving English Learners’ Speaking through Mobile-assisted Peer Feedback

advertisement

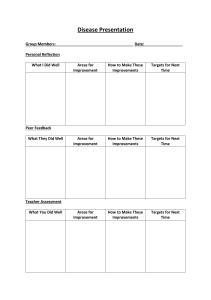

895335 research-article2020 REL0010.1177/0033688219895335RELC JournalWU and Miller SI: English for Academic and Professional Purposes in the Digital Era Improving English Learners’ Speaking through Mobileassisted Peer Feedback RELC Journal 2020, Vol. 51(1) 168­–178 © The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688219895335 DOI: 10.1177/0033688219895335 journals.sagepub.com/home/rel Junjie Gavin Wu and Lindsay Miller City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR Abstract In this article, we report on an action case study on the use of mobile-assisted peer feedback to improve second language (L2) speakers’ English performance. Drawing on the learning-oriented assessment (LOA) framework (Carless, 2007), the study made in-class use of a newly developed mobile app with the provision of peer feedback. The study was conducted with 25 Business School students in an English for Specific Purposes course at a Hong Kong university. A mixed-methods approach was adopted, including a questionnaire survey, a focus group discussion after the class and a teacher journal. In addition to the participants’ general attitudes, two broad themes were found in relation to the participants’ learning experience, namely the use of peer feedback and the affordances and constraints of technology. Results showed that students generally agreed on the positive effects of mobile-assisted peer feedback (e.g. real-time and anonymous feedback), while they recognized some limitations such as the small screen size of their phones and the limited number of given rubrics. Finally, we discuss the implications from different perspectives based on the reported themes. Keywords Speaking, mobile-assisted learning, peer feedback, learning-oriented assessment, classroom based learning ‘in its early days, such research [technology] points to fresh possibilities for enhancing the teaching of speaking’ (McCarthy and O’Keeffe, 2004: 36). In 2004, McCarthy and O’Keeffe called for a closer integration of technology and speaking practice in second language learning. Although we have witnessed a rising interest in improving students’ speaking performance with the development of advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence and augmented reality (Zhang et al., in press), speaking has been the least explored basic language skill, compared with Corresponding author: Junjie Gavin Wu, Department of English, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR. Email: junjiewu4-c@my.cityu.edu.hk WU and Miller 169 listening, reading, and writing (Kessler, 2018). Part of the reason for this dearth of investigation is that speaking is not a key component in many countries’ secondary school testing systems, and therefore does not receive the in-class attention given to the other language skills (Black and William, 2018). Notwithstanding the above, English speaking skills have become crucially important for English as a Second Language (ESL) users. Academically, scholars have to effectively present their findings via English at international conferences. Professionally, Business English as a Lingua Franca has become commonplace. Socially, social communication now extends beyond national boundaries and many platforms (e.g. Instagram, Twitter) offer ESL speakers multimodal ways of communicating with each other. To these ends, it has become clear that speaking in English as a second or foreign language deserves wider research attention. This article explores the perceptions students and their teacher have when using mobile technology in class in an attempt to give feedback on, and hence improve, students’ speaking performance. As part of a larger research project, this article has one overarching research question: How can mobile-assisted peer feedback enhance ESL students’ learning experience in relation to their speaking skills? Learning-oriented Assessment There has been a long-running debate regarding how we can assess students’ oral language skills. This debate centres on the issue of whether we should promote assessment for learning or assessment of learning. Instead of treating these concepts as incompatible, Carless (2007) argued that both types of assessment should be used to reach our ultimate teaching goal – to enhance student learning. Against this backdrop, Carless (2007) suggested the learning-oriented assessment (LOA) framework which emphasizes the goal of supporting learning by engaging learners actively in assessment activities. One of the key constructs of LOA is feedback: the provision of constructive feedback from students (peer and self) and teachers, and the uptake of feedback in a feed-forward process (e.g. use the feedback to improve speaking). In this process, students are encouraged to not only be consumers of language knowledge but producers of language and actively take responsibility for their learning. Furthermore, peer feedback can address the limitations of restricted class time and large-size classes (Lam, 2010). Yet, we must acknowledge that there are still voices challenging the effectiveness of peer feedback and who caution against this as being a magic wand to improve language skills (see Lam, 2010; Xu and Carless, 2017; Yu and Lee, 2016). Despite research that has been done into L2 writing (e.g. Yu and Lee, 2016), our understanding of peer feedback in L2 speaking especially within the technologyenhanced language learning (TELL) context remains limited (Xu and Carless, 2017). This article, as an exploratory project, aims to cast light on the use of mobile-assisted peer feedback to promote L2 speaking in an English for Specific Purposes (ESP) course. Technological Assessment Tools Although there are a number of apps on the market that students can use to improve their English speaking outside the classroom (e.g. Duolingo and Busuu), most of them are not 170 RELC Journal 51(1) Figure 1. The basic interface of PeerEval. designed specifically for use in the traditional classroom context. One exception is PeerEval. PeerEval is available from the Apple App Store and can be accessed through the webpage https://peereval.mobi/ using any technical device. It is a simple-to-use app: after downloading the app, the teacher first needs to set up an online class register by importing students’ names and creating an assessment rubric. Then, with an access code generated from the teacher’s side, students can log into their accounts. After that, students can choose their peer’s name and mark his/her performance based on the set of rubrics (e.g. on a speaking task, as described here). Apart from the marking scale of one to five, an optional comment column is provided. Students complete their marking and hit submit (Figure 1). Once the marking has been done, each student can see their individual feedback from their peers and his/her mark will be compared with the average mark of the entire class (Figure 2). All feedback and students’ marks are available in the teacher’s account so that the teacher can use this information when making a general analysis of his/her students’ speaking performance. WU and Miller 171 Figure 2. Students’ peer feedback. The study Participants The project was conducted with 25 students from an ESP course offered to the Business School at a public university in Hong Kong. The participants included 10 first-year, 12 second-year and three fourth-year learners (15 females, 10 males). Apart from two Mainland Chinese, the other students were all from Hong Kong, aged from 18–22. Their English language proficiency levels were assessed as intermediate to upper-intermediate based on their previous school examination results and corroborated by the teacher’s assessment and observations. Course English for Business Communication aims to improve students’ communication skills by way of a semi-authentic business context. The course is 13 weeks long and the class meets for three hours each week. The syllabus for the course is guided by five assignments and this study reports the results from the business meeting speaking assignment. To help students get more individual feedback and have a better idea of the assessment criteria, the teacher decided to use PeerEval in Week 5 of the course to see if the app might enhance students’ in-class practice. Project The basic steps of the use of PeerEval are illustrated in Figure 3. The pedagogical structures were designed based on the LOA framework to motivate students’ learning through their involvement as peer evaluators and to make use of this feedback as a source to improve their performance in the upcoming teacher-assessed assignment. In Week 4, the basics of the assignment and the app were introduced to the students. Apart from a simple description of the assessment rubric, exemplars of different levels of performance were analysed with the students to better prepare them for the activity. In Week 5, students were organized into groups of five and provided with one business meeting case study, similar to the upcoming 172 RELC Journal 51(1) Figure 3. Pedagogical structures of Weeks 4–6 (business meeting simulation). assessed assignment. The teacher circulated and acted as a facilitator and provided feedback while the students practised their meetings in class. After their meetings, each student was required to use the app to give feedback on their peers’ oral performance. Then, one group was randomly chosen to present their mock meeting in front of the whole class, during which the rest of the students marked this performance with PeerEval. This practice activity acted as a type of standardization for the whole class in how they might use the grading rubric. To conclude the practice session, the teacher synthesized all student comments from each group’s feedback and discussed these with the class. The students were then encouraged to use the feedback they had received in order to improve their performance in their Week 6 teacher-based assessment. Data Collection and Analysis Data were gathered in the following ways: Quantitative data were collected by an attitudinal questionnaire (adapted from Patri, 2002) from one class (N=25) of students at the end of the Week 5 lesson. The questionnaire, containing five 5-point Likert items and five open-ended questions, was used to get students’ feedback regarding their Week 5 learning experience. The Likert questions provided a quantitative snapshot of the students’ perceptions of using the app through a descriptive analysis with a calculation of Mean and Standard Deviation. Qualitative data were gathered from the open-ended questions in the questionnaire and from an interview with volunteer students. The five open-ended questions (e.g. Did you find it difficult to assess your classmates’ talk? If YES, why?) in the questionnaire were utilized to gain further personalized insights of the mobile-assisted learning experience. After that, a post-class group interview (e.g. What do you like/dislike about this app?) was conducted in English with a focus group of four students. These students, from four different in-class groups, volunteered for the interview and as such can be considered willing participants who wanted to share their experiences. During the focus group meeting, some prompts were given by the teacher to elicit students’ opinions regarding WU and Miller 173 the app and the learning experience. Interview data were transcribed by the first author and checked for accuracy by the second author. In addition to these students’ sources of data, we also had the teacher/first author keep a research journal throughout the project to reflect on his own use of the app and his observations of the students’ practice of giving peer feedback in class. Collectively, a thematic analysis was applied to the qualitative data set. The first author adopted Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis procedures and found themes related to the research question. To enhance the validity of the results, the second author then commented on the preliminary findings for further improvement. Based on our research question, two broad themes emerged from the analysis of the student data: peer feedback and the use of technology. Findings The Provision of Peer Feedback Students and the teacher held a positive orientation towards the use of mobile technology as a way to improve English speaking performance with this in-class activity. Students in the survey rated the question: ‘To what extent do you think this app helped you improve your preparation for the assignment?’ as M=3.96 from 1=very little to 5=very much with a SD=0.79. This may not be surprising as all our students were techsavvy and willingly wanted to see if using their smartphones could assist in their language improvement. In the open-ended questions, they listed several advantages, including immediate and anonymous feedback, involvement of the entire class, and the environmentally friendly and convenient-to-use app. Additionally, our interviewees (pseudonyms were used) explained: My group mates have more time to communicate with me. And it’s better than the teacher because the teacher needs to allocate his time to other students. So I think peers can give more detailed suggestions (Nam, Year 1) My group mates may have different opinions about my performance and I can learn from them (Lee, Year 2). Yeah, I got to learn some speaking skills from the teacher or from my peers. And also I get a chance to speak more English in my daily life. So, yeah (Shin, Year 2). Because you guys as peers can talk equally, telling others what you want her or him to improve. So I think it is a better way to give each other feedback (Park, Year 1). Nam recognized the time limitation and appreciated the detailed and real-time feedback from his peers while Lee commented that he was able to receive more help from different group mates. Shin believed that she had improved her speaking via observing and assessing others’ speaking and getting peer feedback. Moreover, she was grateful for the chances to make further use of her English skills. This might be considered a somewhat surprising finding since English is the official language in this English-medium 174 RELC Journal 51(1) instruction (EMI) university, but in monolingual contexts it may not be that unusual to find that students (and their teachers) often interact with their L1 even in EMI situations (Hafner et al., 2015). Park, talking from a social power perspective, acknowledged the equal status in class among peers. Having said that, Park went on to say she did not like giving negative feedback as she believed, ‘I’ll try to be nice, because we are peers, and I wouldn’t be so straightforward to point out the problems’. Lee and Nam, on the other hand, were more direct regarding the provision of critical feedback. It depends on the seriousness of the problem. If it’s too serious I will criticize it. (Lee). If I provide suggestions through the app, I will criticize strictly (Nam). In contrast to Lee and Nam’s directness, Park was held back by her affective concerns. Nam explained his position further: it was because of the anonymity and the reduced pressure of giving the feedback through a non-face-to-face medium that he felt more secure about giving negative comments. According to the teacher’s journal, Nam was a task-oriented and hard-working student while Park demonstrated more relationship-oriented performance in class. These students grew up within a Chinese cultural context, known for its face-saving ethos, which may account for some of their perceptions on giving negative feedback (Wu, 2017). This point will be further discussed later. The participants also encountered a number of challenges regarding peer feedback. Not surprisingly, students expressed their desire for more feedback from the teacher (Xu et al., 2017). Nam, for example, in the interview explained: I think it’s better to add teachers’ advice rather than only students’. I think it’s not very professional enough because there are only students’ suggestions. Similar thoughts were mentioned in the interview with Park: More comments from you maybe. I think because you [the teacher] can give us more concrete advice and because you are the one who gives us marks. So I will bear your comments in mind more than my peers’. These comments indicated that students did not wholly trust their peers’ competence in giving feedback and still heavily relied on their teacher for feedback. This, to some extent, demonstrated the students’ failure of seeing the purpose of the mobile-assisted learning activity. Meanwhile, from the teacher’s observations, it was found that the comment column was not salient or compulsory so many students did not go beyond the numerical feedback and did not offer concrete comments to their peers. I noticed that, if it’s not compulsory, students (or even me!) will just submit the evaluation form without filling in the Comment column. It saves time and efforts, but it also makes the app less constructive and effective to students’ learning (Teacher journal). WU and Miller 175 The Use of Mobile Technology Regarding the technological mediation, students generally agreed that PeerEval was user-friendly as Park remarked that ‘You can directly drop down the marks and comments’. Lee appreciated that ‘The rating system is simple and easy to grade’. Likewise, the teacher reflected on the usefulness of PeerEval as: 1) A simple interface to locate important information 2) A handy operating system for teachers not used to using technology 3) The synchronous view of scores and average marks for learners and the teacher 4) A useful overall display of marks and comments in the teacher’s account (Teacher journal) However, questionnaire respondents and the teacher mentioned some constraints of PeerEval (Table 1). Among others, the trouble of finding their partners’ names due to the small screen size on a phone seems to be a problem for most users. However, with a list of only 25 students this was not considered a major issue. With much larger classes the name search may become a problem and might frustrate students’ desires to make use of the app. Another issue was that the system only allows up to six marking criteria. This limited what peers could make remarks on and according to the questionnaire survey most students commented that the marking descriptions were not detailed enough for them to accurately evaluate their peers’ speaking. It should, however, be stressed here that discussions of the rubrics and an exemplar activity had been conducted before the activity in Week 4 with the students and they may have forgotten how to interpret the rubrics. Table 1. Student Response to and Teacher Reflections on the Use of PeerEval. Themes Student Responses (Questionnaire) Teacher Reflections (Teacher Journal) Technology ‘It automatically logged out when I switched to other applications :( I have to retype all the information.’ ‘I need to find my group mate one by one.’ ‘It may set up a group for marking easily. It is trouble to find out people to mark one by one.’ ‘The marking criteria is too broad.’ ‘Only 5 categories can be used.’ ‘Students, in a big class, had trouble finding their partners, especially when the screen size was not large enough.’ ‘The class was not as large as my previous class in a Mainland Chinese university. I wonder how easy it can be when used in large-size classes.’ ‘I couldn’t fit all my 14 marking items into the system.’ Rubrics Discussion and Conclusion This preliminary investigation attempts to move forward our understanding of mobileassisted peer feedback in L2 speaking. Although small in scale, in this last section, we 176 RELC Journal 51(1) are still able to make five points from our study related to the research question we set out to answer. First, the app used provided a user-friendly experience for the students and the teacher. Spontaneity and anonymity of peer feedback were perceived as defining features of PeerEval among the users. The provision of real-time feedback (as part of a feed-forward process) to learners on their oral performance was somewhat achieved. Therefore, within a limited time (3 hours) all students in the class received some feedback on their oral performance and were expected to use this feedback in the final business meeting assignment. Given the issues of large class size and insufficient class time for speaking practice using mobile-assisted peer feedback in class may offer a way forward. Second, involving students in giving peer feedback allowed them to become producers of knowledge (the evaluator), rather than always relying on teacher feedback (Wu and Miller, in press). This permitted students to transform their identities and participate more fully in their speaking assignments. The questionnaire data and interviewee feedback showed an appreciation to offer and receive peer feedback and due to the collaborative manner of learning the whole class participated in the activity. This promotion of student agency echoes Hafner and Miller’s (2019) idea that learners should be empowered in the whole learning process, through which their learner autonomy will be gradually activated to achieve better learning outcomes. Third, the collaborative mode of learning, afforded by using the app, also reflects the socio-cultural theory of learning in that the learning process is mediated by interactions under specific social and cultural factors (Vygotsky, 1978). The findings show that affective concerns have both facilitated and hindered the effectiveness of peer feedback; learners were more socially equal in providing comments. Yet, their provision of critical feedback was influenced by the interpersonal relationship. Given that our participants grew up in a Confucian culture, face and interpersonal values play a pivotal role in this process and this is something technology, being culturally neutral, cannot account for (Wu, 2018). However, the anonymity of the feedback makes this app useful, especially in the Confucian heritage classroom where face-saving is a salient feature of the context (Xu and Carless, 2017). Fourth, even with a class size of 25 students, it is difficult for the teacher to constantly give individual feedback to each student on their oral performance. Involving peers with the use of technology helped the teacher significantly in this activity. Nonetheless, we need to take account of the uniqueness of this experience for our students. Our students still sometimes failed to recognize the usefulness of peer feedback as they lack sufficient confidence in themselves and their peers to give such feedback. This may not simply be a matter of training and having students use the app more often, but is also a matter of building mutual trust through dialogue between teachers and students, and students themselves. When learners become aware that they can assess their peers accurately, and their comments can be consistent with the teacher’s, they may become more confident in their evaluator abilities. Fifth, although PeerEval is generally perceived as a useful feedback tool for use in class, technological constraints (Table 1) pose some challenges for students. Feedback to the app software designer may help with the student problems. From the teacher’s perspective, how to effectively train students to become comfortable and confident in giving WU and Miller 177 critical feedback when using the app is the main issue. More in-class training time of providing constructive feedback would be useful. This study adds to the limited research into the use of cutting-edge technology in helping L2 speakers learn from peer feedback. Drawing on the preliminary findings from this report, the project is undergoing modifications with a view to implement it with more students and monitor its use over a longer period of time. To finish, we return to McCarthy and O’Keeffe’s (2004) quote, which heads the article, and call for teachers and researchers to investigate the use of technology in class as a way to enhance the teaching of speaking. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ORCID iD Lindsay Miller https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5961-2381 References Black P, Wiliam D (2018) Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 25(6): 551–75. Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101. Carless D (2007) Learning-oriented assessment: conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 44(1): 57–66. Kessler G (2018) Technology and the future of language teaching. Foreign Language Annals 51(1): 205–18. Lam R (2010) A peer review training workshop: coaching students to give and evaluate peer feedback. TESL Canada Journal 27(2): 114. McCarthy M, O’Keeffe A (2004) Research in the teaching of speaking. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 24: 26–43. Hafner CA, Li DCS, and Miller L (2015) Language choice among peers in project-based learning: a Hong Kong case study of english language learners’ plurilingual practices in out-of-class computer-mediated communication. Canadian Modern Language Review 71(4): 441–470. Hafner CA, Miller L (2019) English in the Disciplines: A Multidimensional Model for ESP Course Design. London and New York: Routledge. Patri M (2002) The influence of peer feedback on self-and peer-assessment of oral skills. Language Testing 19(2): 109–31. Vygotsky LS (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Wu JG (2017) Teacher’s presence in synchronous mobile chats in a Chinese university. The Journal of AsiaTEFL 14(4): 778–783. Wu JG (2018) Mobile collaborative learning in a Chinese tertiary EFL context. TESL-EJ 22(2): 1–15. Wu JG, Miller L (in press) Raising native cultural awareness through WeChat: a case study with Chinese EFL students. Computer Assisted Language Learning: 1–31. doi:10.1080/09588221 .2019.1629962 178 RELC Journal 51(1) Xu Y, Carless D (2017) Only true friends could be cruelly honest: cognitive scaffolding and socialaffective support in teacher feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42(7): 1082–94. Yu S, Lee I (2016) Understanding the role of learners with low English language proficiency in peer feedback of second language writing. TESOL Quarterly 50(2): 483–94. Zhang D, Wang M, and Wu JG (in press) Design and implementation of augmented reality for English language education. In: Geroimenko V (ed.) Augmented Reality in Education: A New Technology for Teaching and Learning. Cham: Springer.