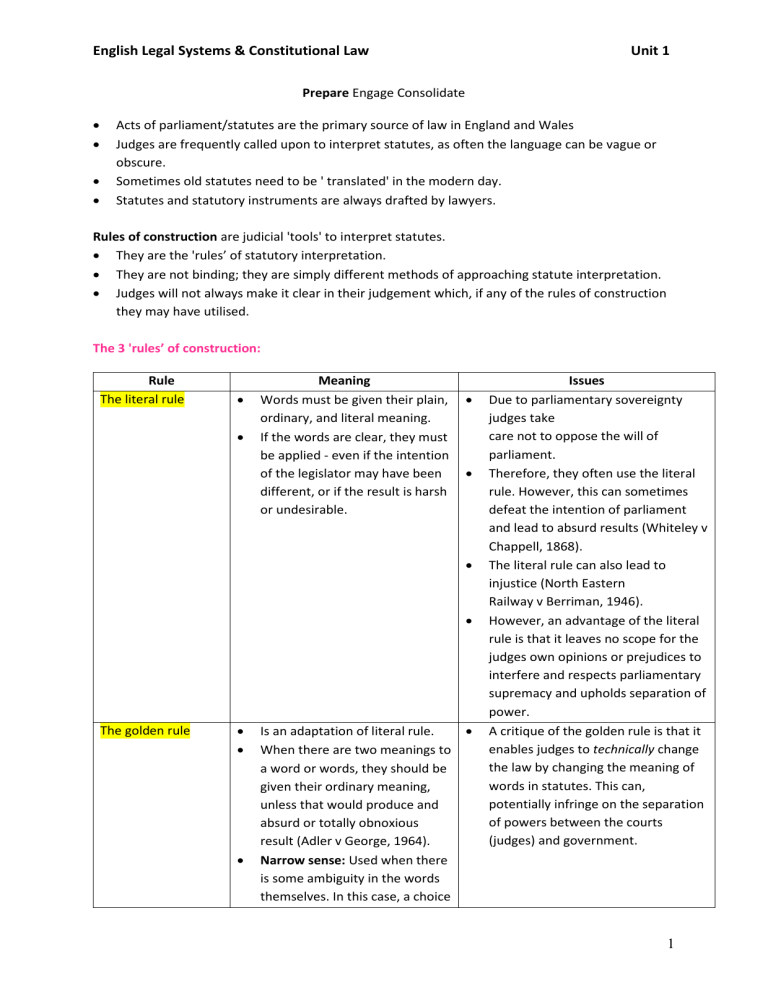

English Legal Systems & Constitutional Law Unit 1 Prepare Engage Consolidate Acts of parliament/statutes are the primary source of law in England and Wales Judges are frequently called upon to interpret statutes, as often the language can be vague or obscure. Sometimes old statutes need to be ' translated' in the modern day. Statutes and statutory instruments are always drafted by lawyers. Rules of construction are judicial 'tools' to interpret statutes. They are the 'rules’ of statutory interpretation. They are not binding; they are simply different methods of approaching statute interpretation. Judges will not always make it clear in their judgement which, if any of the rules of construction they may have utilised. The 3 'rules’ of construction: Rule The literal rule Meaning Words must be given their plain, ordinary, and literal meaning. If the words are clear, they must be applied - even if the intention of the legislator may have been different, or if the result is harsh or undesirable. Issues The golden rule Is an adaptation of literal rule. When there are two meanings to a word or words, they should be given their ordinary meaning, unless that would produce and absurd or totally obnoxious result (Adler v George, 1964). Narrow sense: Used when there is some ambiguity in the words themselves. In this case, a choice Due to parliamentary sovereignty judges take care not to oppose the will of parliament. Therefore, they often use the literal rule. However, this can sometimes defeat the intention of parliament and lead to absurd results (Whiteley v Chappell, 1868). The literal rule can also lead to injustice (North Eastern Railway v Berriman, 1946). However, an advantage of the literal rule is that it leaves no scope for the judges own opinions or prejudices to interfere and respects parliamentary supremacy and upholds separation of power. A critique of the golden rule is that it enables judges to technically change the law by changing the meaning of words in statutes. This can, potentially infringe on the separation of powers between the courts (judges) and government. 1 English Legal Systems & Constitutional Law The mischief rule The purposive approach between meanings is to avoid an absurd or illogical result. Wider sense: Used even where words have only one meaning to avoid a result which is obnoxious to public policy or civil law principles, or breaches parliamentary intention (Re Sigsworth, 1935). Requires the interpreter of the statute to ascertain the legislator's intention. Moreover, what mischief or defect in law was the statute intending to rectify? (Royal college of Nursing v DHSS, 1981 on appeal). Is the modern style of interpreting statutes. Judges examine why the statute was passed and is purpose, even if it means distorting the ordinary meaning of the words. This approach is influenced by prior EU membership as it is widely used in EU law. Unit 1 Some people, (for example, a minority of members of the House of Lords) still believe the literal approach is better, as it is up to parliament to change the law, not judges. As this rule gives judges the most discretion over statutes. Presumption against criminal liablility. Legislation related to EU law: Retained EU law forms a significant part of the English legal system and UK courts continue to use the purposive approach to interpret it. EU statutes follow the civil law tradition, which favours simplicity of drafting and a high degree of abstraction, compared to the exhaustive approach used in the UK and the common law approach traditionally used by English Courts. Therefore, the purposive approach is vital for interpreting this legislation, so that questions of wide economic or social aims are often considered by the courts (Litster v Fourth Dry Doc and Engineering Co Ltd, 1990). 2 English Legal Systems & Constitutional Law Unit 1 Impact of the 1998 Human Rights Act: Section 3 of the HRA 1998 provides that "so far as it is possible to do so, primary and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights" If the court cannot achieve this, it may make a declaration of incompatibility (section 4 of the act). R v A (2002) highlighted this issue as the House of Lords had to decide if s41 of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 (which set out the circumstances for an accused rapist to question his victim in the witness box) was compatible with a defendant’s right to a fair trial under article 6 of the ECHR. The House of Lords found that it was necessary to apply the above rule in this case to ensure the 1998 HRA was upheld. This demonstrates the thin line between judges interpreting and making law. The rules of language: General principles judges may apply when interpreting statutes. Noscitur a sociis (recognition by associated words) Eiusdem generis (of the same kind or nature) Expressio unius est exclusio alterius (expressing one thing excludes another) Meaning ‘known by the company it keeps’. That a word derives meaning from surrounding words. Used to assist in the interpretation of the Factories Act 1961. Most used rule of language. If a general word follows two or more specific words, that general word will only apply to items of the same type as specific words. How to determine if eiusdem generis applies: 1. Are there general words following a list of specific words? 2. If so, what type are the specific words? 3. Interpretation: any new item will be included in the statute only if it is of the same type as the specific words. Wood v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (1986). This means ' to express one is to exclude another’. Therefore, the mention of one or more specific things may be taken to exclude others of the same type. Used in R v Inhabitants of Sedgley (1831). 3 English Legal Systems & Constitutional Law Unit 1 Aids to interpretation: In addition to using the rules of construction and language when interpreting a stature, the courts can also use aids to interpretation when the meaning of a statute is not clear. Intrinsic Aids (the use of the statute itself) The statute must be read as a whole, and the words read in context (note the overlap with the ‘rules of language’). Any words that have been debated by parliament (interpretation) and are therefore part of the statute are legitimate aids. The long and short titles, preamble, punctuation, and headings may also be used as intrinsic aids. Marginal notes are not normally used. Extrinsic Aids (aids outside the statute itself) Interpretation Acts: These acts give definitions for words commonly used in legislation. Dictionaries: Dictionaries can be referred to when a word has no specific legal meaning. Dictionaries are of particular value when a judge is using the literal approach. Other statutes: These could be earlier statutes replaced by the current statute, or any other statute. Although just because a word has been interpreted in one statute doesn't mean it will be interpreted the same way in another. Hansard: All parliamentary debates that take place in the House of commons or the House of Lords about the statute are recorded in Hansard. Traditionally, it was not usually permissible for courts to refer to this preparatory work as an aid to interpretation. More recently, this rule has relaxed, particularly to identify the 'mischief' which an act is intended to remedy. Pepper v Hart (1993) established that the courts could refer to the material recorded in Hansard if: a) The statute is ambiguous or obscure, or its literal meaning leads to an absurdity; and b) The material consists of Clear statements made by a minister or other promoter of the bill. Others include: Law Commission Official Reports Legal Practice International Conventions Other Jurisdictions Historical Setting Academic knowhow Previous Judicial Interpretation 4 English Legal Systems & Constitutional Law Unit 1 Presumptions: In addition to rules and aids, the courts can apply certain presumptions in interpreting legislation. Presumptions assist lawyers by providing a set of assumptions about the intent of Parliament, as a backdrop to their reasoning. There are presumptions used in various areas of the law, but these are examples for statutory interpretation. a) Against alteration of the common law. Unless the statute expressly states an intention to alter the common law, the interpretation which does not alter the existing law will be preferred. b) Against deprivation of the liberty of the individual. Accordingly, any ambiguity in a penal or criminal statute will be interpreted in favour of the citizen. c) Against criminal liability without guilty intention (mens rea). There is a presumption in favour of mens rea or guilty mind in criminal matters. When creating new criminal offences, Parliament does not always define the mens rea required. In these cases, the presumption will be applied. In Sweet v Parsley [1970] AC 132, a schoolteacher was convicted of drugs offences after her tenants were discovered growing cannabis in her rented house. She was found guilty, despite her lack of knowledge of the situation, but the decision was later overturned by the House of Lords (now the Supreme Court) using this presumption. d) Against the retrospective operation of statutes. Where an Act of Parliament becomes law, a presumption arises that it will apply only to future actions. This is particularly important in relation to taxation and criminal law cases. However, some legislation is specifically stated to have retrospective effect; an example is the War Crimes Act 1991, which allows the prosecution of those suspected of committing acts of atrocity during World War II. e) Against deprivation of property or interference with private rights. f) Against binding the Crown. Unless there is a clear statement to the contrary, legislation is presumed not to apply to the Crown. g) Against ousting the jurisdiction of the courts. Principles of interpretation: 1. Start with a rule of construction, initially the language, especially if a literal rule. 2. Watch out for the purposive rule, specifically in retained EU or ECHR law, but now also of more general application. 3. Support it with rules of language, especially if a list is involved, and aids to interpretation. 4. Keep presumptions in mind. 5