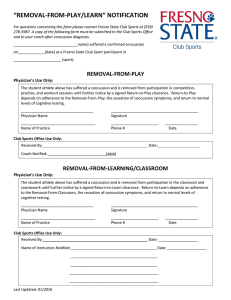

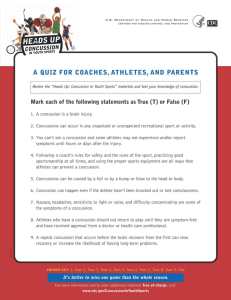

Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19 (2016) 194–199 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsams Original research On-field management and return-to-play in sports-related concussion in children: Are children managed appropriately? Harini P. Haran a,b,c , Silvia Bressan a,b,d , Ed Oakley a,b,e , Gavin A. Davis b,e , Vicki Anderson b,e , Franz E. Babl a,b,e,∗ a Emergency Department, Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia c Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia d University of Padova, Italy e Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia b a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 8 November 2014 Received in revised form 20 January 2015 Accepted 14 February 2015 Available online 24 February 2015 Keywords: Concussion Traumatic brain injury Head injury Sport Child Return to play a b s t r a c t Objectives: On-field management and return-to-play guidelines aim to ensure the identification and appropriate management of the concussed athlete. Compliance with current guidelines in many settings is unknown. We assessed whether key components of current concussion guidelines are being followed in child athletes. Design: Prospective observational study. Methods: Data were collected from children (5–18 years) presenting to a paediatric emergency department with sport-related concussion via researcher-administered surveys in the emergency department and during a follow up phone call. On hospital discharge all patients received a return to sports fact sheet based on the International Concussion in Sports Group. Results: Ninety-three had sustained a concussion (mean age 12.7 (±0.27) years, 83% male). Sports played included Australian Football (47%), soccer (12%), rugby (9%) basketball (8%), other (25%). 82% participated in organised sports. Concussive signs or symptoms included loss of consciousness (41%), disorientation (36%), vomiting (23%), amnesia (30%), headache (60%). For concussive injury in organised sports (n = 76), overall 42% were not managed according to recommended guidelines: 19% were not immediately removed from play, 29% were allowed to return to play on the same day and 27% were not assessed by qualified personnel. 93% of parents and 96% of patients were unaware of concussion or return-to-play guidelines from their organisations. Overall, 72% were compliant with provided return-to-play guidelines. Conclusions: Many children with sports related-concussion are not formally assessed on-field and continue to play. On-field concussion management and return to play practices are often suboptimal. Awareness and education of coaches, teachers, parents and children need to be improved. © 2015 Sports Medicine Australia. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Sports-related concussion has received growing media and scientific attention in recent years for its increasing incidence and possible short and long-term sequelae.1 Children are particularly vulnerable with 65% of all sport-related head injuries presenting to US emergency departments (EDs) being in persons aged 5–18 years.2 In Australia, the impact of concussion on the child and on the health sector is not well described, despite 63% of school-aged ∗ Corresponding author. E-mail address: Franz.babl@rch.org.au (F.E. Babl). children participating in at least one organised sport outside school hours.3 Concussed athletes, who return to play whilst still symptomatic, have an increased risk of recurrent injury and associated complications. This is due to a pathophysiological window of brain vulnerability post-concussion, as well as a post-concussion reduction in reaction time, information processing and speed, exposing the athlete to the demands of sport with a reduced capacity for evasive and defensive actions, with resultant increased risk of recurrent brain injury.4,5 The main issues of concern therefore are concussion management at the time of injury and timing of return to play. The International Concussion In Sport Group (CISG) consensus statement,5 and position statements from the American Medical http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2015.02.009 1440-2440/© 2015 Sports Medicine Australia. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. H.P. Haran et al. / Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19 (2016) 194–199 Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM)6 and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN)7 all advocate prohibition of athletes returning to play/train on the same day as their injury. In Australia, both the Australian Football League (AFL) and the National Rugby League (NRL) recommend immediate removal from play, first aid management and assessment by medical personnel for athletes with suspected concussion, as per the CISG 2012 Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport.5,8,9 In Australian Football, junior leagues are required to have a person with current first aid qualifications available at all games.8 Once concussion has been diagnosed, both sporting bodies mandate a graduated return-to-play process commencing once the athlete is asymptomatic, progressing to normal game play in a minimum of 6 days. No evidence based guidelines for safe return-to-play following sport-related head injury have been validated for children, and the current guidelines are modelled on those for adults recommended in the CISG 2012 Consensus Statement.5,10 It remains unclear if general or sports specific guidelines for concussion management translate into changed on field practice, and how much players and parents know about the management of concussion and return to play instructions. There have been few studies assessing on-field management of head injuries in children and youth, or coach awareness and understanding of recommended guidelines. A recent survey of community AFL and NRL coaches and sports trainers identified knowledge gaps in key aspects of on-field management and the importance of a graduated return-to-play.11 International studies have recognised similar gaps in both coach and player knowledge.12,13 Involvement in sport is highly encouraged for children to improve health, fitness, confidence and teamwork skills. However it is crucial that sport is also safe for children who are rapidly developing both cognitively and physically. This study aimed to identify: (1) compliance with on-field management guidelines for concussion; (2) parent and player awareness of return-to-play guidelines; and (3) parent and player compliance with return-to-play guidelines supplied to them. We also planned to assess differences between sports, and between organised and unorganised sporting activities. 2. Methods Children aged between 5 and 18 years presenting to the emergency department (ED) at The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne (RCH) with sport-related concussion between May 2013 and November 2013 were recruited for the study. The RCH is a paediatric tertiary referral hospital and paediatric trauma centre for the state of Victoria, Australia, with an annual ED census of 82,000 patients. The study was approved by the RCH human research ethics committee. Sports included both organised and non-organised sports, and included recreational activities such as motor-cycle and bicycle riding, skateboarding, horse-riding and ice-skating. Injuries sustained while playing on a playground or during games involving running but not involving a ball were not included. We enrolled concussive injuries defined as a blow to the head resulting in one or more of the following: loss of consciousness, headache, vomiting, amnesia, disorientation, seizure or focal neurology.5 We excluded lacerations or bruises to the head or face without concussive signs or symptoms. Eligible children were identified at initial presentation to the ED. Verbal consent was obtained for initial data collection and followup phone call, which was completed with parents between 3 weeks and 3 months after recruitment. Refusal to participate would not impact on the patient’s clinical management and parents/guardians were able to withdraw their child from the study at any time. 195 All families were provided with the hospital’s return-to-sports fact sheet,14 outlining the graduated return-to-play protocol recommended by the CISG 2008 Consensus Statement,15 and a fact sheet providing general advice for head injury post-dicharge.16 Though both the CISG statement and head injury fact sheet were more detailed in their recommendations, we defined a patient as “compliant” with CISG on field management if they were removed immediately from play, assessed by qualified personnel and not allowed to return to play on the same day. We defined a patient as “compliant” with CISG RTP if they at least followed two of the steps of the step wise return to play and did not return to play while still experiencing symptoms. Analysis was descriptive with categorical variables presented as percentages and 95% confidence intervals for relevant key percentages, and continuous variables described as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range according to their parametric or non-parametric distribution. Results for Australian Football (AF) and non-AF sports played were dichotomised. 3. Results During the study period, there were 1115 head injuries (HIs) of any severity that presented to the ED. A total of 271 sport-related HIs among children aged 5–18 years were identified. Of these, 169 were missed during prospective recruitment, mostly while researchers were unavailable to approach patients for enrolment. A total of 102 patients with sports related HIs were approached; 9 were excluded as they had soft tissue or neck injuries without concussive symptoms and 93 had concussion (the study group). No patient who was approached refused consent for participation. Of enrolled patients with concussion, 8 were lost to follow up. The average number of days until follow up was 32 (±5.2) days. Demographics and signs and symptoms at presentation of the 93 enrolled children are presented in Table 1. Children arrived by ambulance in 50.5% of cases and apart from one patient arriving by air ambulance the remainder arrived in private car. Mean age of the children with concussion was 12.7 (SD ± 0.27) years. Sports played were AF (47.3%), soccer (11.8%), rugby (8.6%) basketball (7.5%) and other sports (24.7%). which included baseball, gymnastics, ice-skating, speed ice-skating, horse-riding, handball, hockey, taekwando, motocross, and riding a scooter, bicycle, skateboard or quadbike. Most children (81.7%) were involved in organised sports. Of the organised sports, 53.9% (95% CI 42.1–65.5%) were playing AF. Children had been competing in their sport on average 3.7 years (SD ± 0.3). Overall, protective equipment was worn by 51.6% (95% CI 41.0–62.1%), mainly mouth guards (41.9%) and helmets (12.9%). All participants were asked whether they wore a helmet at the time of injury, with only 2.3% of AF players and 22.4% of non-AF players wearing a helmet. Signs and symptoms of concussions and management of children prospectively enrolled who were playing AF is compared with those playing non-AF sports in Table 1. The most frequent concussive symptoms and signs were headache (60.2%), and LOC (40.9%). Neuroimaging was performed in 18/93 (19.4%) of patients with none showing intracranial pathology. Forty-five percent were observed in a short stay unit (30.1%) or admitted to an inpatient ward (15.1%). Important factors regarding on field management of concussive injuries are shown in Table 2. For most injuries a coach or medical staff attended and assessed the patient. Ten percent of patients did not report their head injuries at the time and were therefore not assessed on field. Symptom checklist use could only be determined definitively in ∼50% of cases overall as 20% of patients did not know if the checklist had been used. 196 H.P. Haran et al. / Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19 (2016) 194–199 Table 1 Demographics, signs and symptoms of children with sports related concussion. Gender Male Female Age (years) 5–7 8–10 11–15 16–18 Organiser Club School Non-organised Nature of organised play Competition Friendly Training/Physical Education NA Competition level Suburban Interschool Other NA Competition experience Nil ≤1 year 1–5 years >5 years Concussive signs and symptoms Loss of consciousness Disorientation Vomiting Amnesia Headache Seizure activity Focal neurological deficit Disposition Treated and discharged Observed in Short Stay Inpatient admission Australian Football (n = 44) Non-Australian Football (n = 49) Total (n = 93) 43 (97.7%) 1 (2.3%) 34 (69.4%) 15 (30.6%) 77 (82.8%) 16 (17.2%) 3 (6.8%) 4 (9.1%) 35 (79.5%) 2 (4.5%) 1 (2.0%) 9 (18.4%) 32 (65.3%) 7 (14.3%) 4 (3.9%) 13 (14.7%) 67 (70.6%) 9 (10.8%) 36 (81.9%) 5 (11.4%) 3 (6.8%) 23 (46.9%) 12 (24.3%) 14 (28.6%) 59 (63.4%) 17 (18.3%) 17 (18.3%) 40 (90.9%) 1 (2.3%) 0 3 (6.8%) 22 (44.9%) 4 (8.2%) 8 (16.3%) 17 (34.7%) 62 (66.7%) 5 (5.4%) 8 (8.6%) 18 (19.4%) 31 (70.5%) 4 (9.1%) 6 (13.6%) 3 (6.8%) 11 (22.4%) 6 (12.2%) 11 (22.4%) 21 (42.9%) 42 (45.2%) 10 (10.8%) 17 (18.3%) 24 (25.8%) 3 (6.8%) 4 (9.1%) 21 (47.7%) 16 (36.4%) 13 (26.5%) 9 (18.4%) 14 (28.6%) 13 (26.5%) 16 (17.2%) 13 (14.0%) 35 (37.6%) 29 (31.2%) 17 (38.6%) 18 (40.9%) 9 (20.5%) 15 (34.1%) 25 (56.9%) 1 (2.3%) 1 (2.3%) 21 (42.9%) 15(30.6%) 12 (24.5%) 13 (26.5%) 31 (63.2%) 1 (2.0%) 4 (8.2%) 38 (40.9%) 33 (35.5%) 21 (22.6%) 28 (30.1%) 56 (60.2%) 2 (2.2%) 5 (5.4%) 30 (68.2%) 11 (25.0%) 3 (6.8%) 21 (42.9%) 17 (34.7%) 11 (22.4%) 51 (54.8%) 28 (30.1%) 14 (15.1%) Other levels of competition included; state, regional, rural and age group levels. NA = not applicable. When compliance with on-field management practices was defined as performing all tasks recommended by the CISG statement, 32/76 (42%; 95% CI 31–54%) children involved in organised-sports were not managed appropriately. This included 14/76 (19%; 95% CI 10–31%) not removed immediately from play; 21/76 (27%; 95% CI 17–40%) not assessed by qualified personnel; and 22/76 (29%; 95% CI 18–41%) allowed to return to play same day, with 6/76 (7.9%; 95% CI 3.0–16.4%) allowed to return to play after less than 30 min. Follow-up calls were completed for 85 children. Of these 85 children, 42 (49.4%) played AF. Overall 65 children (76.5%; 95% CI 66.0–85.0%) experienced post-concussive symptoms. The most frequent post concussive symptoms reported in follow up were fatigue (57.6%), headache (56.5%), neck pain (25.9%), difficulty concentrating (17.6%), difficulty remembering (15.3%), irritability (15.3%), sensitivity to light (14.1%), being more emotional (12.9%), dizziness (11.8%), sensitivity to noise (11.8%), nausea and vomiting (10.6%). Forty-nine of 85 children (57.6%; 95% CI 46.4–68.3%) experienced symptoms for fewer than 7 days, and 16/85 (18.8%; 95% CI 11.2–28.8%) experienced symptoms for 10 days or more after their injury. Compliance rates with components of RCH return-to-play guidelines are shown in Table 3. None of the 85 patients followed the CISG based step-wise process exactly as set out in terms of a 6 step staged process or with progression to the next step every 24 h. However, as set out in methods, we defined compliance with RTP guidelines in a modification of the 2008 CISG guidelines.15 Seventy children (82.4%; 95% CI 72.6–89.8%) (57 organised, 13 non-organised) followed at least two steps of the step-wise RTP process. One of these children playing organised AF did not complete each step for at least 24 h, and 12/85 (14.1%; 95% CI 7.5–23.4%) children, all playing organised sports, returned to play whilst still experiencing symptoms. A further two children who had followed a step-wise RTP, both playing organised AF, experienced symptoms during their RTP process but did not rest for at least 24 h until asymptomatic, as prescribed by the CISG protocol. Fifty-five percent of children had followed a RTP and returned to sport and six were still symptomatic and had not yet returned to sport. Therefore, overall 61/85 (71.8%; 95% CI 61.0–81.0%) were broadly compliant with our RTP guidelines. In organised sports, 47/70 (67.1%; 95% CI 54.9–77.9%) were compliant with our RTP guidelines. In most measures of compliance there was little difference between the different organised sports or unorganised sport. However more children who played organised AF received medical clearance before returning to play. Prior to presentation for this injury, 45/93 (48.4%; 95% CI 37.9–59.0%) of parents were aware of some HI information. However, 71/76 (93.4%; 95% CI 85.3–97.8%) of parents and 73/76 (96.1%; 95% CI 88.9–99.2%) of children involved in organised sports were unaware of head injury information from their own organisation. Of the 17 children with a previous sport-related HI in organised H.P. Haran et al. / Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19 (2016) 194–199 197 Table 2 On field management of concussive injuries. Organised sports (n = 76) AF (n = 41) Personnel attending injury 1 (2.4%) No Yes 36 (87.8%) Coach 21 Medical staff 33 Other 5 Did not report head injury 4 (9.8.%) Personnel assessing injury 4 (9.8%) No Yes 32 (78.0%) 16 Coach 24 Medical staff 2 Other 1 (2.4%) Unknown 4 (9.8%) Did not report head injury Field-side assessment using symptom checklist 10 (24.4%) No Yes 15 (36.6%) 12 (29.3%) Unknown Did not report head injury 4 (9.8%) 0 NA, non-organised Stoppage of play 18 (43.9%) No 18 (43.9%) Yes NA 5 (12.2%) 4 Did not report head injury End of game 1 0 Non-team sports Immediate removal from play No 4 (9.8%) 33 (80.5%) Yes Did not report head injury 4 (9.8%) Stand down time <15 min 2 (4.9%) 2 (4.9%) 15–30 min 0 Unknown NA 37 (90.2%) 7 Kept playing Did not return to play 30 Same day return to play since head injury 29 (70.7%) No 12 (29.3%) Yes 8 Kept playing Same game 4 0 Unknown Management between field and emergency department 9 (22.0%) No 32 (78.0%) Yes 22 Paramedic 10 Other Doctor/Hospital 3 Other Transport to emergency department 17 (41.5%) Personal car 23 (56.1%) Ambulance 1 (2.4%) Air transport Non-organised sports (n = 17) Total (n = 93) 3 (8.6%) 29 (82.9%) 21 15 4 4 (11.4%) 5 (29.4%) 9 (52.9%) 0 5 2 3 (17.6%) 9 (9.7%) 74 (79.6%) 42 53 11 11 (11.8%) 9 (25.7%) 21 (60.0%) 11 15 6 1 (2.9%) 4 (11.4%) 6 (35.3%) 8 (47.1%) 0 6 1 0 3 (17.6%) 19 (20.4%) 61 (65.6%) 27 45 9 2 (2.2%) 11 (11.8%) 17 (48.6%) 7 (20.0%) 7 (20.0%) 4 (11.4%) 0 NA NA NA NA 17 27 (29.0%) 22 (23.7%) 19 (20.4%) 8 (8.6%) 17 (18.3%) 7 (20.0%) 22 (62.9%) 6 (17.1%) 3 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA NA 25 (32.9%) 40 (52.7%) 11 (14.5%) 7 2 2 3 (8.6%) 29 (82.9%) 3 (8.6%) NA NA NA 7 (9.2%) 62 (81.6%) 7 (9.2%) 1 (2.9%) 1 (2.9%) 1 (2.9%) 31 (88.6%) 6 25 NA NA NA NA NA NA 3 (3.9%) 3 (3.9%) 1 (1.3%) 68 (89.5%) 13 55 25 (71.4%) 10 (28.6%) 6 2 0 12 (70.1%) 4 (23.5%) 3 0 1 (5.9%) 66 (71.0%) 26 (28.0%) 15 6 1 (1.1%) 14 (40.0%) 21 (60.0%) 15 4 4 4 (23.5%) 13 (76.5%) 9 6 1 27 (29.0%) 66 (71.0%) 46 20 8 20 (57.1% 15 (42.9%) 0 8 (47.1%) 9 (52.9%) 0 45 (48.4%) 47 (50.5%) 1 (1.1%) Non-AF (n = 35) AF – Australian Football. sports, only 1 child and parent were aware of HI information from their organisation. At follow-up, all parents (100%) were aware of the hospital provided RTP guidelines as provided in the HI handout they received. However, 74.3% (95% CI 62.4–84.0%) of all parents with completed follow-up calls who participated in organised sports were unaware of any RTP guidelines from their organisation. Of those participating in club sports, 15/54 (27.8%, 95% CI 16.5–41.6%) were aware of RTP information from their club and of those participating in school sports, 3/16 (18.8%; 95% CI 4.0–45.6%) were aware of RTP information from their school. 1 child and 1 parent was aware of both school and club guidelines. 4. Discussion It is widely accepted that same day return to play in concussed athletes can cause prolonged symptoms, and increase the risk of both complications and recurrent HI.7,17 CISG consensus recommendations5 have been adopted by Australian sporting codes such as AFL8,18 and NRL.9 They mandate the use of an approved sideline assessment tool (SAT) and trained personnel to assess concussive injury. This study was designed to assess the implementation of these guidelines in children’s sport, the participants’ knowledge of these guidelines, and concussed patient compliance with return to play guidelines. The underlying sports 198 H.P. Haran et al. / Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19 (2016) 194–199 Table 3 Return to play (RTP) protocol followed in children with concussive injury in organised Australian Football (AF), organised non-AF sports and non-organised sports, including second head injury. Organised Sports (n = 70) Attempted any RTP No Yes First full gameplay RTP attempt Not yet full RTP <7days post-concussion ≥7days post-concussion Attempted step-wise RTP No Yes NA, not yet RTP Contact RTP with medical clearance No Yes NA, not yet returned to contact sports RTP whilst symptomatic No Yes NA Symptoms during RTP and action taken: No symptoms Experienced symptoms Continued RTP without rest Rested until asymptomatic for ≥24 h NA Non-organised sports (n = 15) Total (n = 85) 3 (9.7%) 28 (90.3%) 1 (6.7%) 14 (93.3%) 6 (7.1%) 79 (92.9%) 4 (10.3%) 0 35 (89.7%) 10 (32.3%) 1 (3.2%) 20 (64.5%) 4 (26.7%) 1 (6.7%) 10 (66.7%) 18 (21.2%) 2 (2.4%) 65 (76.5%) 4 (10.3%) 33 (84.6%) 2 (5.1%) 4 (12.9%) 24 (77.4%) 3 (9.7%) 1 (6.7%) 13 (86.7%) 1 (6.7%) 9 (10.6%) 70 (82.4%) 6 (7.1%) 21 (53.8%) 14 (35.9%) 4 (10.3%) 22 (71.0%) 3 (9.7%) 6 (19.4%) 8 (53.3%) 4 (26.7%) 3 (20.0%) 51 (60.0%) 21 (24.7%) 13 (15.3%) 31 (79.5%) 6 (15.4%) 2 (5.1%) 22 (71.0%) 6 (19.4%) 3 (9.7%) 13 (86.7%) 1 (6.7%) 1 (6.7%) 66 (77.6%) 13 (15.3%) 6 (7.1%) 28 (71.8%) 9 (23.1%) 5 4 2 (5.1%) 21 (67.7%) 7 (22.6%) 3 4 3 (9.7%) 13 (86.7%) 1 (6.7%) 1 NA 1 (6.7%) 62 (81.2%) 17 (11.8%) 9 8 6 (7.1%) AF (n = 39) Non-AF (n = 31) 2 (5.1%) 37 (94.9%) NA – not applicable. activities in this study were dominated by AF, a sport mainly played in the southern hemisphere winter months when the study was conducted. This study highlights that while these international sports related concussion guidelines have been adopted by sporting organisations they have not necessarily been implemented at many sporting fields with 40% of children who sustained a concussion playing sport not receiving on field management consistent with CISG recommendations.5 Deficiencies in management were evident at all points of the guideline – players were not immediately removed from play, were allowed to return to play on the same day, or were not assessed by qualified personnel. International studies have been conducted assessing youth sporting staff awareness and knowledge of concussion management guidelines,12,13,19 and have identified gaps in coach and trainer sports related concussion management. This study indicates that these knowledge gaps translate into inappropriate on-field management and premature return to play in youth athletes. Despite the largest sporting codes adopting best practice concussion management guidelines, only 7% of parents or children in this study were aware of any pre-injury concussion instructions or RTP guidelines from their sporting organisation, suggesting current implementation of the guidelines is inadequate. We also found that a number of children did not report their head injury during the game. The problem of underreporting of HI by youth athletes has been previously identified, with higher rates of underreporting in studies in the US and New Zealand compared to the present study.20,21 Although we did not prospectively ascertain reasons for not reporting concussion at the time of injury, the lack of awareness of concussion guidelines, and the presumed lack of knowledge of the significance of a sports related concussion may be contributing factors. Most children recovered within 7 days with 81% reporting no postconcussive symptoms 7 days from their injury. Previous studies have demonstrated higher rates of post concussive problems.22–24 However, these studies used detailed neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive recovery whilst the present study used a researcher administered symptom checklist only. While over two thirds complied to some degree with the CISG5 based RTP information provided at hospital discharge, only 8.2% complied with all 6 steps of the protocol. Of particular concern, 17.6% of children either returned to play whilst symptomatic or did not follow appropriate remedial action after experiencing symptoms during their RTP process. Possible explanations for this inadequate response include poor parental understanding, lack of medical supervision during the step-wise programme and the difficulty of using a process primarily designed for adult athletes in a non-professional paediatric sports setting. Generally, the literature shows poor compliance rates with RTP guidelines among youth athletes.12,13,25 A US study of concussed high school athletes found that at least 40% were non-compliant, however it was unclear whether all athletes were aware of RTP guidelines.12 A recent Australian study of mostly adult athletes found a rate of non-compliance of 87%.25 Despite the poor compliance with the RTP steps the majority of children in this study waited until they were asymptomatic for at least 6 days before returning to full gameplay and followed the appropriate sections of RTP recommendation if they experienced symptoms during any stage of RTP. These rates are higher than those previously reported.12,13,25 Previous studies, however, have examined all sports related head injuries and concussion, whilst our cohort tended to the more severe end of the spectrum as we included only children presenting to a major paediatric hospital after a head injury. The non-compliance with RTP guidelines in youth athletes is often explained by the sporting culture of ‘not letting the team down’. Thirty-two percent of New Zealand high school rugby players believed a concussed player on their team had been under pressure to return to play.13 At follow-up no parent in our study reported that their child had been under any such pressure. Our findings demonstrate the lack of universal adherence to appropriate on-field management of sports related HI, and RTP guidelines are not being adequately implemented or supervised by clubs or medical personnel. These practices potentially expose H.P. Haran et al. / Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19 (2016) 194–199 children to a greater risk of complications from concussion. Considering the focus of a number of sporting organisations on improving care for possible concussion through their websites and freely provided materials26 there appears to be a problem with both the transfer of information from the sporting organisation to the individual clubs, coaches, parents and players, and the implementation of the recommendations. In the US state laws mandate compliance with concussion education and return to play rules.26 Similar laws do not exist in Australia nor in many other countries. Before considering legislative changes the community, sporting clubs, and sporting organisations need to accept the problem and address the knowledge and implementation deficits in managing sports related concussion. Findings are limited in their generalisability due to a focus on a single, paediatric tertiary referral hospital. The results were dominated by AF injuries as there was a weekend and winter seasonal focus which is the main season for football playing in the southern hemisphere. This may have resulted in a study population dominated by AF. Selection bias may have been introduced as recruitment was based on researcher availability. Although very few sideline assessment tools appeared to have been used on-field information on the use of these tools may be better collected by targeting coaches and team staff rather than parents and child athletes, who may not be aware of the tools being used. The population studied was hospital based and findings cannot be generalised to all field-side concussions, particularly those not transferred to hospital. 5. Conclusions On-field concussion management and return to play practices are often suboptimal and awareness and education of coaches, teachers, parents and children and actual practice on the sports fields need to be improved. Many children with sports related concussion are not being appropriately assessed on-field and continue to play despite signs or symptoms of concussion, potentially increasing the risks of complications and further head injury. Practical implications • Sports associations need to improve the transfer of information about best practice of on-field concussion management to the individual clubs, coaches, parents and players, and ensure the implementation of the recommendations. • Acute care settings should routinely provide information on return to play and school in children with concussion. • Return to play recommendations for children and adolescents will need to be modified from existing adult focused guidelines to be more practicable. Acknowledgements The authors declare that there are no competing interests and no grants associated with the research contained within this manuscript. We acknowledge the support of the families involved in the study, the assistance of medical and nursing staff and Ms. Amanda Williams, emergency research coordinator, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. This study was supported by the Victorian Government Infrastructure Support programme and the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation (2014400), Melbourne, Australia. Contributor statement: FEB conceived the study. All authors developed the design of the study. HH undertook the data collection and analysed the data. HH drafted the manuscript with significant contributions from all authors. 199 Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.02.009. References 1. Harrison EA. The first concussion crisis: head injury and evidence in early American football. Am J Public Health 2014; 104(5):822–833. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301840. 2. CDC. Nonfatal traumatic brain injuries related to sports and recreation activities among persons aged ≤ 19 years – United States, 2001–2009. MMWR 2011; 60(39):1337–1342. 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4901.0 – children’s participation in cultural and leisure activities, Australia, Organised Sports, 2009. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/4901.0∼Apr+2009∼Main+ Features∼Organised+sport?OpenDocument [accessed 05.03.13]. 4. Shrey DW, Griesbach GS, Giza CC. The pathophysiology of concussions in youth. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2011; 22(4):577–602. 5. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Aubry M et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th international conference on concussion in sport held in Zurich, November 2012. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 216(5):e55–e71. 6. Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M et al. American medical society for sports medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47:15–26. 7. American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: the management of concussion in sports (summary statement): report of the quality standards subcommittee. Neurology 1997; 48:581–585. 8. AFL Research Board, AFL Medical Officer’s Association. Guidelines for the management of concussion in Australian football for general practitioners. Available from: http://www.aflcommunityclub.com.au/index.php?id=66 [accessed 05.05.13]. 9. International Rugby Board. IRB concussion guidelines. Available from: http://www.irbplayerwelfare.com/?documentid=3 [accessed 05.04.13]. 10. Davis GA, Purcell LK. The evaluation and management of acute concussion differs in young children. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48:98–101. 11. White PE, Newton JD, Makdissi M et al. Knowledge about sports-related concussion: is the message getting through to coaches and trainers? Br J Sports Med 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-09-2785. Published Online First: [16 September 2013]. 12. McLeod TC, Schwartz C, Bay RC. Sport-related concussion misunderstandings among youth coaches. Clin J Sport Med 2007; 17(2):140–142. 13. Guilmette TJ, Malia LA, McQuiggan MD. Concussion understanding and management among New England high school football coaches. Brain Inj 2007; 21(10):1039–1047. 14. Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia. Head injury – return to sport. Available from: http://www.rch.org.au/kidsinfo/fact sheets/Head injuryreturn to sport/ [accessed 31.03.14]. 15. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 3rd international conference on concussion in sport held in Zurich, November 2008. Br J Sports Med 2009; 43:i76–i84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.058248. 16. Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia. Head injury – general advice. Available from: http://www.rch.org.au/kidsinfo/fact sheets/Head injury/ [accessed 31.03.14]. 17. McCrea M, Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW et al. Acute effects and recovery time following concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA 2003; 290(19):2556–2563. 18. AFL Development. AFL community home. Available from: http://aflcommunityclub.com.au [accessed 11.04.14]. 19. Shenouda C, Hendrickson P, Davenport K et al. The effects of concussion legislation one year later-what have we learned: a descriptive pilot survey of youth soccer player associates. PM&R 2012; 4:427–435. 20. Yard EE, Comstock RD. Compliance with return to play guidelines following concussion in US high school athletes, 2005–2008. Brain Inj 2009; 23:888–898. 21. Sye G, Sullivan SJ, McCrory P. High school rugby players’ understanding of concussion and return to play guidelines. Br J Sports Med 2006; 40:1003–1005. 22. Field M, Collins MW, Lovell MR et al. Does age play a role in recovery from sports-related concussion? A comparison of high school and collegiate athletes. J Pediatr 2003; 142:546–553. 23. Sim A, Terryberry-Spohr L, Wilson KR. Prolonged recovery of memory functioning after mild traumatic brain injury in adolescent athletes. J Neurosurg 2008; 108:511–516. 24. Delaney TS, Lacroix VJ, Leclerc S et al. Concussions among university football and soccer players. Clin J Sport Med 2002; 12:331–338. 25. Hollis SJ, Stevenson MR, McIntosh AS et al. Incidence, risk and protective factors in mild traumatic brain injury in a cohort of Australian nonprofessional male rugby players. Am J Sports Med 2009; 37:2328–2333. 26. Washington State Legislature. RCW 28A.600.190 Youth sports – concussion and head injury guidelines – injured athlete restrictions – short title, Washington, Access Washington, 2009. Available from: http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default. aspx?cite=28A.600.190 [accessed 11.04.14].