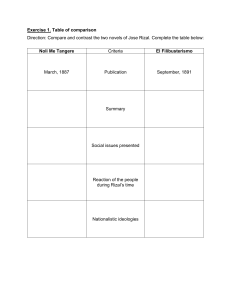

Noli Me Tangere By Dr. Jose Rizal Noli Me Tangere is Latin for "touch me not," an allusion to the Gospel of St. John where Jesus says to Mary Magdelene: "Touch me not, for I am not yet ascended to my Father." Rizal entitled this novel as such drawing inspiration from John 20:1317 of the Bible, the technical name of a particularly painful type of cancer (back in his time, it was unknown what the modern name of said disease was). He proposed to probe all the cancers of Filipino society that everyone else felt too painful to touch. Noli Me Tángere, is an 1887 novel by José Rizal during the colonization of the Philippines bySpain to describe perceived inequities of the Spanish Catholic friars and the ruling government. Originally written in Spanish, the book is more commonly published and read in the Philippines in either Tagalog or English. Early English translations of the novel used titles like An Eagle Flight (1900) and The Social Cancer (1912), disregarding the symbolism of the title, but the more recent translations were published using the original Latin title. It has also been noted by the Austro-Hungarian writer Ferdinand Blumentritt that "Noli Me Tángere" was a name used by local Filipinos for cancer of the eyelids; that as an ophthalmologist himself Rizal was influenced by this fact is suggested in the novel's dedication, "To My fatherland". José Rizal, a Filipino nationalist and medical doctor, conceived the idea of writing a novel that would expose the ills of Philippine society after reading Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. He preferred that the prospective novel express the way Filipino culture was perceived to be backward, antiprogress, anti-intellectual, and not conducive to the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment. He was then a student of medicine in the Universidad Central de Madrid. The plot revolves around Crisostomo Ibarra, mixedrace heir of a wealthy clan, returning home after seven years in Europe and filled with ideas on how to better the lot of his countrymen. Striving for reforms, he is confronted by an abusive ecclesiastical hierarchy and a Spanish civil administration by turns indifferent and cruel. The novel suggests, through plot developments, that meaningful change in this context is exceedingly difficult, if not impossible. The death of Ibarra’s father, Don Rafael, prior to his homecoming, and the refusal of a Catholic burial by Padre Damaso, the parish priest, provokes Ibarra into hitting the priest, for which Ibarra is excommunicated. The decree is rescinded, however, when the governor general intervenes. The friar and his successor, Padre Salvi, embody the rotten state of the clergy. Their tangled feelings—one paternal, the other carnal—for Maria Clara, Ibarra’s sweetheart and rich Capitan Tiago’s beautiful daughter, steel their determination to spoil Ibarra’s plans for a school. The town philosopher Tasio early notes similar past attempts have failed, and his sage commentary makes clear that all colonial masters fear that an enlightened people will throw off the yoke of oppression. Precisely how to accomplish this is the novel’s central question, and one which Ibarra debates with the mysterious Elias, with whose life his is intertwined. The privileged Ibarra favors peaceful means, while Elias, who has suffered injustice at the hands of the authorities, believes violence is the only option. Ibarra’s enemies, particularly Salvi, implicate him in a fake insurrection, though the evidence against him is weak. Then Maria Clara betrays him to protect a dark family secret, public exposure of which would be ruinous. Ibarra escapes from prison with Elias’s help and confronts her. She explains why, Ibarra forgives her, and he and Elias flee to the lake. But chased by the Guardia Civil, one dies while the other survives. Convinced Ibarra’s dead, Maria Clara enters the nunnery, refusing a marriage arranged by Padre Damaso. Her unhappy fate and that of the more memorable Sisa, driven mad by the fate of her sons, symbolize the country’s condition, at once beautiful and miserable. Using satire brilliantly, Rizal creates other memorable characters whose lives manifest the poisonous effects of religious and colonial oppression. Capitan Tiago; the social climber Doña Victorina de Espadaña and her toothless Spanish husband; the Guardia Civil head and his harridan of a wife; the sorority of devout women; the disaffected peasants forced to become outlaws: in sum, a microcosm of Philippine society. What does Noli Me Tangere teach us? CHARACTERS NOTE: That some of the photos you will see in the presentation is not the actual face of the character. Although, this is only a model according to their characteristics. Crisostomo Ibarra Juan Crisóstomo Ibarra y Magsalin, commonly referred to in the novel as Ibarra or Crisostomo, is the novel's protagonist. The mestizo (mixed-race) son of Filipino businessman Don Rafael Ibarra, he studied in Europe for seven years. Ibarra is also María Clara's fiancé. Maria Clara María Clara de los Santos, commonly referred to as María Clara, is Ibarra's fiancée and the most beautiful and widely celebrated girl in San Diego. She was raised by Kapitán Tiago delos Santos, and his cousin, Isabel. In the later parts of the novel, she was revealed to be an illegitimate daughter of Father Dámaso, the former curate of the town, and Doña Pía Alba, Kapitán Tiago's wife, who had died giving birth to María Clara. Kapitan Tiago Don Santiago de los Santos, known by his nickname Tiago and political title Kapitán Tiago, is said to be the richest man in the region of Binondo and possessed real properties in Pampanga and Laguna de Baý. He is also said to be a good Catholic, a friend of the Spanish government and thus was considered a Spaniard by the colonial elite. Kapitán Tiago never attended school, so he became the domestic helper of a Dominican friar who gave him an informal education. Padre Damaso Dámaso Verdolagas, better known as Padre Dámaso, is a Franciscan friar and the former parish curate of San Diego. He is notorious for speaking with harsh words, highhandedness, and his cruelty during his ministry in the town. An enemy of Crisóstomo's father, Don Rafael Ibarra, Dámaso is revealed to be María Clara's biological father. Elias Elías is Ibarra's mysterious friend and ally. Elías made his first appearance as a pilot during a picnic of Ibarra and María Clara and her friends. Pilosopong Tasyo Filósofo Tasio (Tagalog: Pilósopong Tasyo) was enrolled in a philosophy course and was a talented student, but his mother was a rich but superstitious matron. Like many Filipino Catholics under the sway of the friars, she believed that too much learning condemned souls to hell. She then made Tasyo choose between leaving college or becoming a priest. Since he was in love, he left college and married. Doña Victorina Doña Victorina de los Reyes de de Espadaña, commonly known as Doña Victorina, is an ambitious Filipina who classifies herself as a Spaniard and mimics Spanish ladies by putting on heavy makeup. The novel narrates Doña Victorina's younger days: she had lots of admirers, but she spurned them all because none of them were Spaniards. Later on, she met and married Don Tiburcio de Espadaña, an official of the customs bureau ten years her junior. However, their marriage is childless. Sisa Narcisa, or Sisa, is the deranged mother of Basilio and Crispín. Described as beautiful and young, although she loves her children very much, she cannot protect them from the beatings of her husband, Pedro. Crispin Crispín is Sisa's seven-year-old son. An altar boy, he was unjustly accused of stealing money from the church. After failing to force Crispín to return the money he allegedly stole, Father Salví and the head sacristan killed him. It is not directly stated that he was killed, but a dream of Basilio's suggests that Crispín died during his encounter with Padre Salví and his minion. Basilio Basilio is Sisa's 10-year-old son. An acolyte tasked to ring the church's bells for the Angelus, he faced the dread of losing his younger brother and the descent of his mother into insanity. At the end of the novel, a dying Elías requested Basilio to cremate him and Sisa in the woods in exchange for a chest of gold located nearby. Do you think Rizal was able to deliver his message clearly through Noli?