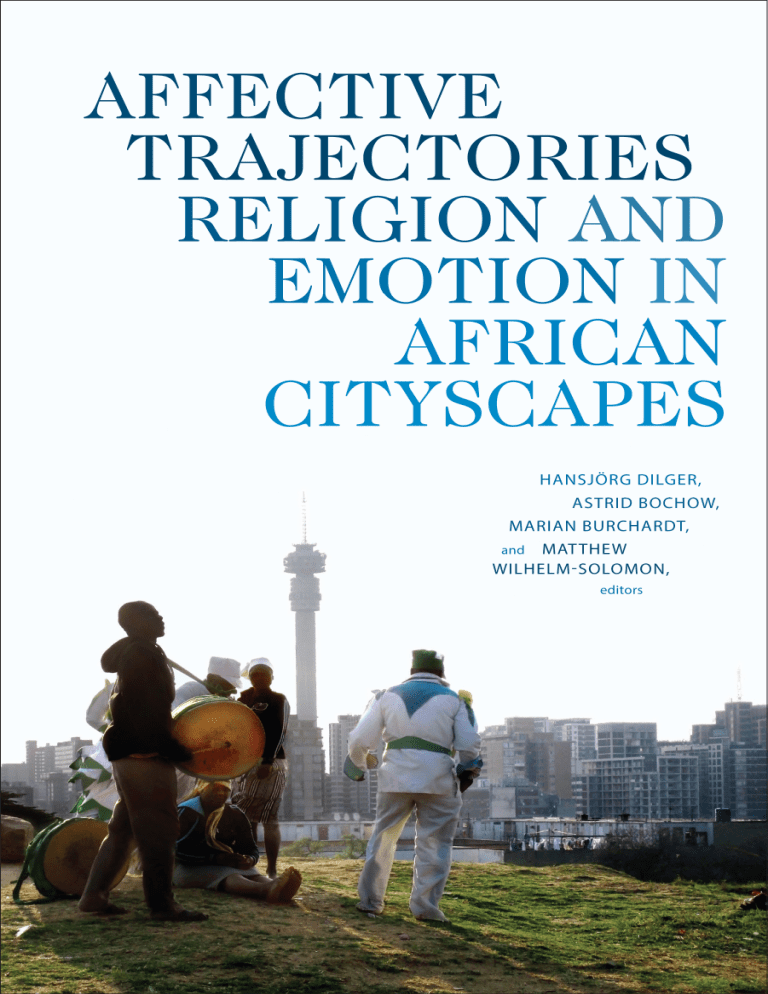

Affective Trajectories: Religion and Emotion in African Cityscapes

advertisement