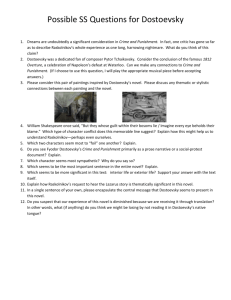

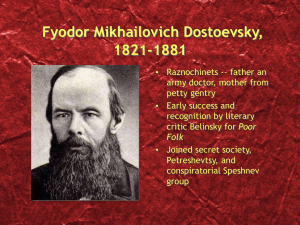

1 Dostoevsky and the Ballets Russes: Images of Savagery and Spirituality in the British Response to Russian Culture, 1911-1929 Darya Protopopova British literary critics and art connoisseurs did not express a consistent and prolonged interest in Russian art and literature until the late nineteenth century. Generally, the attention that was paid towards Russia in nineteenth-century Britain was of political nature, heightened during periods of hostility between the two countries such as the Crimean War of 1853 – 1856. In early twentieth-century Britain, suspicion and hostility towards the Russians were replaced by admiration of Russian art and literature, partly because the two countries became allies during the First World War.1 As critics have pointed out, 1910 to 1925 was, roughly, the period when British attitudes regarding Russia changed dramatically from condescension and mistrust of an ‘uncivilized’ political enemy, to admiration of Russian art and laudatory fantasies about the ‘soul’ of Russian people. Rachel May defines the period of 1910 – 1925 the years of the ‘Russian craze’ in Britain.2 For many centuries, Britain had viewed Russia as an adversary of Western civilization, associated with the Orient and the primitive. These associations did not vanish with the developing amity between the two allies. Moreover, as the East and the archaic became subjects of great interest among the modernists, these characteristics boosted the fashion in Britain for all things Russian during the first two decades of the twentieth century. In the early 1900s, the British Russophiles, such as Maurice Baring, Stephen Graham, and John William Mackail, came to believe that their country was in need of ‘spiritual aid from Russia 1 See L.H. Honigwachs, Edwardian Discovery of Russia, 1900 - 1917 (Columbia University, Ph.D., 1977) 1-12. R. May, The Translator in the Text: On Reading Russian Literature in English (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern UP, 1994) 30-1. 2 2 to help redeem her from commercialism and materialism’.3 They saw Russia, formerly described in the British press as a land of imaginary savages, as the country of no-less imaginary saints and prophets. Graham defined Russia as ‘a church, a holy place where the Western may smooth out a ruffled mind and look upon the beauty of life’.4 Similarly, in 1919 Virginia Woolf wrote about ‘the features of a saint’ in ‘every great Russian writer’.5 Woolf’s contemporaries stopped seeing Russia as a culturally backward country, ‘a clog … to the general movement of progress’.6 British modernists, including Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, T.S. Eliot, and Katherine Mansfield, celebrated Russian novelists as guides in their search for new narrative methods. Russia also became a symbol of originality in visual arts. The Russian Ballet was enthusiastically received as avant-garde.7 The Russian painters Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov took part in Roger Fry’s ‘Second PostImpressionist Exhibition’ in 1912.8 This does not mean, however, that British writers ceased to perceive Russia as ‘wild’ and ‘barbarous’. At the start of the twentieth century, the untutored, elemental, and Far Eastern flavours—the “Otherness” with which Russia had been associated—were transformed into symbols of modernity and liberation in the eyes of British artists. One example of this modernisation of the image of Russia is Roger Fry’s celebration of Russian art – alongside Oriental and primitive arts – as a source of innovative ideas. Fry believed that the cultural hierarchy which had formed in Western art criticism by the turn of the century had to be reconsidered, so that primitive and all other non-European arts would no longer be seen as 3 D. Brewster, East-West Passage: A Study in Literary Relationships (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1954) 164. Maurice Baring (1874–1945), poet and author, travelled widely around Russia and in 1910 published his famous Landmarks in Russian Literature. Stephen Graham (1884-1975) was a publicist and traveller. John William Mackail (1859 – 1945), scholar and socialist, was Oxford Professor of Poetry in 1906 – 1911 and President of the British Academy in 1932 – 1936. 4 S. Graham, Undiscovered Russia (London: John Lane; The Bodley Head, 1912) 327. 5 V. Woolf, “Modern Novels.” The Essays of Virginia Woolf. Ed. A. McNeillie. Vol. 3 (London: The Hogarth Press, 1988) 35. 6 J.W. Mackail, Russia’s Gift to the World (London; New York; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, 1915) 7. 7 L. Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (New York; Oxford: 1989) 97. 8 See M. Chamot, “The Early Work of Goncharova and Larionov.” The Burlington Magazine 97(627) (June 1955) 170, 172-174. 3 inferior to the cultures of so-called civilised countries.9 He argued that primitive art could show English artists of the time a way out of what he perceived to be an aesthetic dead-end: Why should [the artist] … wilfully return to primitive, or, as it is derisively called, barbaric art? The answer is that it is … simply necessary, if art is to be rescued from the hopeless encumbrance of its own accumulations of science; if art is to regain its power to express emotional ideas.10 Fry praised primitive art for the qualities which, in his view, British art had lost over the centuries, such as ‘directness of vision’ and ‘complete freedom’.11 He led a tireless war against what he called ‘descriptive’ art, which he argued only conveyed the outer qualities of things, neglecting their ‘soul’.12 In his search for ‘vitality’, ‘sincerity’, and ‘spontaneity’, Fry turned his critical attention to the French Impressionists, and Islamic, Byzantine and primitive art.13 Russian art occupied a prominent position among Fry’s alternatives to the British aesthetic tradition. The Russian Ballet attracted Fry’s attention with its use of Russian folk motifs in its search for ultra-modern methods of stage design. Commenting on Mikhail Larionov’s designs for the ballet Children’s Tales, first shown in London in 1919, Fry notes their ‘crude vehemence of colour which sets just the right key by its reminiscence of Russian peasant art and children’s toys’.14 In 1930 Fry wrote an article for a catalogue of the exhibition of Russian icons at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where he developed his ideas about ‘the immense difference between the Russian and See R. Fry, “The Courtauld Institute of Art” (1930). A Roger Fry Reader. Ed. C. Reed (Chicago; London: Chicago UP, 1996) 277. 10 Idem., “The Grafton Gallery – I” (1910). A Roger Fry Reader 86. 11 Idem., “The Art of the Bushmen” (1910). Idem., Vision and Design (London: Chatto and Windus, 1923) 97; “Negro Sculpture” (1920). Vision and Design 101. 12 Idem., “The Post-Impressionists – II” (1910). A Roger Fry Reader 92. 13 For Fry’s application of the term ‘vitality’ to Byzantine and Islamic art, see “An Appreciation of the Swenigorodskoi Enamels.” The Burlington Magazine. Vol. 21. No. 113 (August 1912). 293; “The Munich Exhibition of Mohammedan Art-II.” The Burlington Magazine. Vol. 17. No. 90 (September 1910) 327. For Fry’s application of the term ‘sincerity’ to the works of Cézanne and children’s drawings, see Cézanne: A Study of His Development (London: The Hogarth Press, 1927) 17, 27; “An Essay of Aesthetics” (1909). Vision and Design 20. Fry criticized Sir Joshua Reynolds for a lack of ‘spontaneity’ in his Reflections on British Painting (London: Faber, 1934) 53. 14 Idem., “M. Larionow and the Russian Ballet” (1919). A Roger Fry Reader 291. 9 4 West-European mental attitude’.15 Among the ‘curiously unfamiliar’ qualities of Russian iconography he names their ‘feverish intensity and intimacy of emotion’ and their focus on ‘the movements of the soul’.16 In Fry’s opinion, works of Russian medieval artists revealed signs of ‘Oriental influences’.17 For British modernists, declaring one’s preference for the exotic and unconventional was an effective way of rebelling against Victorianism.18 In their Russomania, they focused on the unfamiliar or ‘strange’ qualities of Russian art – on everything that placed the latter in opposition to their ‘very orderly civilisation’.19 One vivid example is the British reception of the Russian Ballet. During the first two seasons of the Ballets Russes in Paris in 1909 – 1910, Sergei Diaghilev, creator of the company, realised that the West only applauded specific presentations of Russia. As the Russian diplomat Peter Lieven, a spectator at many of Diaghilev’s productions, observed, ‘[t]he West expected from Diaghilev not only Russian national colour, but something like Eastern Asiatic exoticism which the press and public demanded of anything Russian’.20 Lieven’s description of Nicholas Roerich’s designs for the ‘Polovtsian Dances’ from the opera Prince Igor (first performed in Paris in 1909) demonstrates the image of Russia that appealed to Western audiences: [Roerich’s] task of representing on the stage the boundless expanse of the Southern Russian steppes was not an easy one. … There are no extant relics of the Polovtsi … But Roerich was not a specialist in primitive cultures for nothing. He produced costumes for the Polovtsi which were a combination of the Yakut and Kirghiz costumes, and the result was both powerful and convincing.21 Idem., “Russian Icon-Painting from a Westrn-European Point of View”. Masterpieces of Russian Painting: Twenty Colour Plates and Forty-three Monochrome Reproductions of Russian Icons and Frescoes from the XI to the XVIII Centuries. Ed. M. Farbman (London: Europa Publications, 1930) 35. 16 Ibid., 36, 42. 17 Ibid., 56. 18 See L. Woolf, Beginning Again: An Autobiography of the Years 1911 to 1918 (London: The Hogarth Press, 1964) 34; V. Woolf, Roger Fry: A Biography (London: The Hogarth Press, 1940) 83. 19 An expression from Woolf’s review of Chekhov’s stories: Essays 3:84. 20 P. Lieven, The Birth of Ballets-Russes. Trans. L. Zarine (London: Allen and Unwin, 1936) 75-6. 21 Ibid., 82. The Polovtsy were a nomadic Turkic people who inhabited the central Eurasian steppe between the 11th and 13th centuries. The Yakuts are a Mongoloid people of north-eastern Siberia. The Kirghiz are a Mongolian people of west-central Asia. 15 5 The British reception of the Ballets Russes, starting from its first appearance in London on 21 June 1911, closely echoed the French response. Members of the high society and literati, who constituted the main part of Diaghilev’s British audiences before the War, were enchanted by the Oriental setting of the ballets like Scheherazade and by Russian folk motifs in the music and stage design of ballets like Prince Igor, The Firebird and Petrushka. The Times applauded ‘the savagejoyful panther-leaping of the men’ in Prince Igor and the ‘sensuous langour’ and ‘savagery’ of Scheherazade.22 British passion for the Ballets Russes continued after the War. In 1921, T.S. Eliot praised Igor Stravinsky’s music for the ballet The Rite of Spring, for evoking the spirit of ‘primitive ceremony’ and ‘possessing a quality of modernity’ at the same time.23 Similarly, in his account of the Georgian cultural scene, Frank Swinnerton writes: ‘To an English public weary of English things and already longing for whatever was savage and untamed, the wildness of [the Ballets Russes was] like firewater to an innocent native’.24 The British cognoscenti’s enthusiasm about the Ballets Russes is a confirmation of ‘a central paradox of Modernism: the most sophisticated achievement of the present is a return to, or a new appreciation of, the archaic’.25 The ‘barbaric’ Russian mind was also the main discussion point in British reviews of Russian literature, which was being translated in large quantities in early twentieth-century Britain. Virginia Woolf’s first reading of Dostoevsky (a French translation of Crime and Punishment) in 191226 coincided with the start of what came to be known in Britain as the ‘Dostoevsky cult’ – the period of heightened interest in Dostoevsky, which lasted, according to Helen Muchnic, from 1912 until 1921, i.e., the years during which William Heinemann published Constance Garnett’s 22 The Times. 24 June 1911; 17 October 1911; 25 October 1911. T.S. Eliot, “London Letter.” The Dial, October 1921, 452. 24 F. Swinnerton, The Georgian Literary Scene: A Panorama (London: Heinemann, 1935) 296. 25 M. Bell, “The Metaphysics of Modernism.” The Cambridge Companion to Modernism. Ed. M. Levenson (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999) 20. 26 The Letters of Virginia Woolf. Ed. N. Nicolson. Vol. 2 (London: The Hogarth Press, 1978) 5. 23 6 translations of Dostoevsky, starting with The Brothers Karamazov.27 The first English translations of Dostoevsky by Frederick Whishaw were published in the 1880s, although, until Garnett’s translations appeared, educated English-reading audience had preferred French translations of his novels. T.S. Eliot remembered his visit to Paris in late 1910: During the period of my stay in Paris, Dostoevsky was very much a subject of interest amongst literary people … I read Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov in the French translation during the course of that winter. These three novels made a very profound impression on me.28 The main critical work on Dostoevsky which remained popular in Britain even after English studies of him appeared was also French – namely, Melchior de Vogüé’s Le Roman Russe (1886). Robert Lord describes the ‘disastrous’ effect De Vogüe’s book had on the subsequent interpretations of Dostoevsky in Britain: Dostoevsky crawled out of De Vogüé’s pages a creature from another planet, ‘an abnormal and mighty monster’, a colossus, the embodiment of dark primitive Russia, a ‘true Scythian’. … The phrase ‘the religion of suffering’ – probably coined by De Vogüé – has left an indelible mark on several generations … Even the best of Dostoevsky's critics have sometimes echoed De Vogüé without even being aware of the fact.29 For two decades after the publication of Whishaw’s translations, Dostoevsky and his interpretation by De Vogüé had hardly been discussed by the British critics, until, in 1912, came a turning point in Dostoevsky's reception in Britain. According to Frank Swinnerton, then a reader for the publishing firm Chatto and Windus, in that year, ‘every young literary or pseudo-literary person in London The last, thirteenth volume appeared in 1920. H. Muchnic, “Dostoevsky’s English Reputation (1881 – 1936).” Smith College Studies in Modern Languages. Vol. XX. Nos. 3-4 (April-July 1939) 61. 28 Unpublished letter, quoted in: J.C. Pope, “Prufrock and Raskolnikov.” American Literature. Vol. 18. 319. 29 R. Lord, Dostoevsky: Essays and Perspectives (London: Chatto and Windus, 1970) 3. 27 7 seized and consumed with a fury of delight’ Garnett’s version of The Brothers Karamazov, declaring Dostoevsky's book ‘the greatest novel ever written’.30 In Britain of the time, it became fashionable to regard Russian literature as the fruit of a nonWestern civilization. In their fascination with the exotic Russian mind, British critics were influenced by De Vogüé’s descriptions of Russian writers. De Vogüé discerned features of ‘a Russian peasant’ in the physiognomy of Turgenev and Dostoevsky, likening Turgenev to a member of ‘a pastoral tribe from beyond the Ural Mountains’.31 His idea that Turgenev ‘personified all the striking qualities of the true Russian race, its spontaneous goodness of heart, natural simplicity and self-resignation’, anticipated what the British intellectuals, such as Graham and Mackail, would write on Russia in the 1910s.32 De Vogüé had argued that Russian novelists – Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky – attempted to describe in their works a ‘peculiar national disease’, which expressed itself in the Russian tendency of falling into emotional extremes, such as ‘despair, fatalism, savagery, asceticism’ and ‘sheer madness’.33 In the 1910s, the association of Russia with a dichotomous union of wildness and spirituality repeatedly emerged in the writings of the British Russophiles. Among leading British Russianists of the time was a Cambridge classical scholar Jane Ellen Harrison (1850 – 1928).34 She explained her fascination with Russian culture in a letter she wrote to Gilbert Murray in 1914: ‘[W]hatever sort of a wild beast Russia makes of herself she still cares more than any other nation for the things of the spirit, and that is priceless (though as you say dangerous)’.35 Dostoevsky's artistic ‘violence’ and his preoccupation with ‘the depths of the darkest souls’ were recurrent themes in Woolf’s reviews of Dostoevsky.36 ‘Violent and subtle emotions’ 30 Swinnerton 144. E.M. de Vogüé, The Russian Novel. Trans. from the 11th ed. by H.A. Sawyer (London: Chapman and Hall, 1913) 156, 262. 32 Ibid. 33 De Vogüé 282. 34 For an account of Jane Harrison’s interest in Russia see D.S. Mirsky, Jane Ellen Harrison and Russia (Cambridge: Heffer, 1930). 35 Quoted in J. Stewart, Jane Ellen Harrison: A Portrait from Letters (London: The Merlin Press, 1959) 155. 36 Essays 2:86, 166; 3:114. 31 8 discerned by Woolf in Dostoevsky's novels bear resemblance to the image of the untamed Russia that attracted the British audience to the Russian Ballet and Russian folk art.37 The writings by De Vogüé and Harrison demonstrate that when Russian novels became popular in the West, the atmosphere of extreme emotional intensity was not ascribed by the critics to Dostoevsky's works exclusively. Nor did the first British responses to Dostoevsky characterize him as the only Russian novelist preoccupied with the matters of the soul. However, the more familiar Dostoevsky became to the British critics, the more often they defined him as a unique writer even among other Russian novelists. In his 1910 essay ‘Tourgeniev and Dostoievsky’, Arnold Bennett, after commenting on ‘the spontaneous, unconscious realism of the Russians’, went on to juxtapose ‘the highest and most terrible pathos’ of Dostoevsky and ‘the calm and exquisite soft beauty’ of Turgenev.38 The definition of Dostoevsky as the most ‘Russian’ writer became one of the dominant themes in Dostoevsky's British criticism of the time. Lytton Strachey observed that Dostoevsky ‘is acclaimed as the most distinctively Russian of writers; and, no doubt, it is this very fact that has so far prevented his popularity in England’.39 Having commented on Dostoevsky's books being ‘agitated, feverish, intense’, Strachey noted that ‘this kind of atmosphere offers a peculiarly marked contrast to that of the ordinary English novel’.40 Similarly, in 1912 Percy Lubbock observed that Dostoevsky is, ‘both by habit of mind and by literary method far more remote from Western ways than either of the two great novelists [Tolstoy and Turgenev] with whom it seems inevitable to compare him’.41 It appears that the word ‘Russian’ was used as a literary term in the British reviews of the time, signifying unfamiliar and difficult. It also stood for the literature that was perceived as new and prophetic. One was obliged to know ‘the Russians’, at least by reputation, in order to 37 Essays 2:86. A. Bennett, Books and Persons: Being Comments on a Past Epoch, 1908 – 1911 (London: Chatto and Windus, 1917) 209, 212-13. 39 [L. Strachey.] “Dostoievsky” [review of Constance Garnett’s translation of The Brothers Karamazov, first published in The Spectator, 28 September 1912]. Idem., Spectatorial Essays (London: Chatto and Windus, 1964) 174-5. 40 L. Strachey, Spectatorial Essays 176-7. 41 [P. Lubbock.] “Dostoevsky.” TLS. 4 July 1912. 269. 38 9 appear informed about the latest literary events. Dostoevsky was universally recognized as the most difficult and, therefore, most Russian author. Championing Dostoevsky's Russianness became a popular way of proclaiming one’s non-conformist literary tastes. The mysterious Russian soul, which the novels by Dostoevsky and other Russian writers supposedly helped to fathom, was a fashionable literary concept of the time. De Vogüé paid tribute to the soul of Russia ‘at home on the abysmal depths of the ocean’ as early as in 1886.42 Jane Harrison argued that the aspects of the Russian verb ‘are … one clue to the reading of the Russian soul’.43 In 1912 Percy Lubbock observed that ‘through [Dostoevsky] alone can we hope to understand the Russian soul, divined and interpreted in his novels as nowhere else’.44 The British commentators on Dostoevsky followed two main directions in their interpretation of the Russian soul, as epitomized in Dostoevsky's novels. One stance was to use the word ‘soul’ in its theological sense, which led certain critics to the discussion of the religious message in Dostoevsky's works. Arthur Clutton-Brock argued that Dostoevsky refused to divide his characters ‘into sheep and goats’: ‘For him all men have more likeness to each other than unlikeness … and because he is always aware of the soul in them, he has a Christian sense of their equality’.45 John Middleton Murry developed this theological line in the British criticism of Dostoevsky to an extreme. In his Fyodor Dostoevsky: A Critical Study (1916), he argued that Dostoevsky ‘was not a novelist’, but a visionary, whose novels should be read as spiritual literature.46 The second stance in the discussion of Dostoevsky's preoccupation with the soul was to use the word ‘soul’ as a synonym for ‘mind’, which certain critics tended to do when describing Dostoevsky as an expert on human psychology. T.S. Eliot praised Dostoevsky’s understanding of the human brain: 42 De Vogüé 282. J.E. Harrison, Russia and the Russian Verb: A Contribution to the Psychology of the Russian People (Cambridge, Heffer, 1915) 3. 44 [P. Lubbock.] “Dostoevsky.” TLS. 4 July 1912. 269. 45 [A. Clutton-Brock.] “The Faith of Dostoevsky.” TLS. 7 August 1913. 325. 46 J.M. Murry, Fyodor Dostoevsky: A Critical Study (London: Martin Secker, 1916) 48. 43 10 Dostoevsky's point of departure is always a human brain in a human environment, and the ‘aura’ is simply the continuation of the quotidian experience of the brain into seldom explored extremities of torture.47 The modernists’ admiration for Dostoevsky's ‘power of reconstructing those most swift and complicated states of mind’ was a prerequisite for their later interest in psychoanalysis.48 In the literary criticism of the 1920s Dostoevsky is often mentioned alongside with Freud.49 In 1928, Freud himself contributed to this association, by writing an article on ‘Dostoevsky and Parricide’, translated into English in the following year.50 Woolf was ‘gulping up’ Freud’s The Future of an Illusion and Civilisation and Its Discontents in December 1939.51 After 1917, the British response to Dostoevsky was significantly shaped by the context of the Russian revolution and civil war. Reports on ‘the appallingly chaotic conditions of affairs in Russia’ encouraged certain critics to read Dostoevsky as a ‘psychoanalyst’ of his own nation, rather than as a writer preoccupied with common features of human nature.52 In his 1918 article on Dostoevsky, George Thorn discusses the ‘arriv[al]’ of the Russian proletariat, ‘influenced by ideas as crude and wild as those which Dostoevsky satirises [in The Possessed]’.53 Due to the political context, throughout the late 1910s and 1920s, the main point of attraction in Dostoevsky for the British readers remained the impulsiveness and occasional deliriousness of his characters. In 1921, The Times celebrated Dostoevsky's centenary by publishing an article on his life and works. The article highlighted a strong autobiographical element in Dostoevsky's novels: It was [Dostoevsky’s] personal experience that enabled him so vividly to depict in his work that strange impulse to approach the edge of the abyss, gaze down, and on occasion to T.S. Eliot, “Beyle and Balzac.” The Athenaeum. 30 May 1919. 392. V. Woolf, “More Dostoevsky.” Essays 2:85. 49 J.D. Beresford, “Psychoanalysis and the Novel.” The London Mercury. February 1920. 426-9. 50 S. Freud, “Dostoevsky and Parricide.” Trans. D.F. Tait. Realist. Vol. 1 (4). 1929. 18-33. 51 The Diary of Virginia Woolf. Ed. A.O. Bell. Vol. 5 (London: The Hogarth Press, 1984) 249-50. 52 G.W. Thorn, “Sidelights on the Psychology of the Russian Revolution from Dostoevsky.” The Contemporary Review 113 (January/June 1918) 695. 53 Thorn 698. 47 48 11 plunge into its gloomy mystery. He knew something still more terrible, something that he defined as ‘the craving that sometimes arises in the most believing and reverent man to deny …the holy of holies of his own heart … the most sacred ideal of the nation in all its fullness’. This blasphemous convulsive impulse … Dostoievsky must himself have known.54 Whether or not the emotions described in Dostoevsky's novels were autobiographical, it is important to note that certain British cognoscenti, attracted to Dostoevsky because of his alleged ‘madness’, themselves were prone to spiritual extremism. In her letter to John Middleton Murry, Katherine Mansfield ridicules Murry’s attempts ‘to abase [himself] like Dostoievsky did’: [W]hen certain winds blow across your soul they bring the smell from that dark pit & the uneasy sound from those hollow caverns - & you long to lean over the dark driving danger & just not fall in – But letting us all see meanwhile how low you lean –55 Articles on Dostoevsky's biography in periodicals, as well as publications of Dostoevsky's letters and diaries, made it widely known in Britain of the 1910s that Dostoevsky once served a sentence of hard labour in Siberia for his association with an underground intellectual group.56 Murry’s views on Dostoevsky demonstrate that the British Russophiles often perceived the author of The Brothers Karamazov as an advocate of spiritual and political rebelliousness. Modernist writers frequently referred to Dostoevsky's ‘strangeness’. When commenting on Garnett’s translation of The Brothers Karamazov, Strachey calls Dostoevsky’s genius ‘strange’ and his works ‘disconcerting’ both in their form and ‘spirit’.57 Reviewing one of the Dostoevsky-related publications issued by The Hogarth Press, Murry mentions ‘Turgenev’s belief that Dostoevsky was [Anon.] “A Great Russian Novelist: Feodor Dostoievsky”. The Times. 11 November 1921. Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield. Ed. V. O’Sullivan and M. Scott. Vol. 1 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984) 318. 56 Letters of Fyodor Michailovitch Dostoevsky to His Family and Friends. Trans. E.C. Mayne (London: Chatto and Windus, 1914); Dostoevsky: Letters and Reminiscences. Trans. S.S. Koteliansky and J.M. Murry (London: Chatto and Windus, 1923); New Dostoevsky letters. Trans. S.S. Koteliansky (London: Mandrake Press, 1929); The Letters of Dostoyevsky to His Wife. Trans. E. Hill and D. Mudie; with an introduction by D.S. Mirsky (London: Constable, 1930). 57 L. Strachey, Spectatorial Essays 175-6. 54 55 12 a psychological Marquis de Sade’.58 The modernists welcomed the difficulty and unexpectedness of Dostoevsky's works, believing them to be the result of his desire to disclose deeper truths about human nature and to set new limits for the art of fiction. Strachey, Katherine Mansfield, James Joyce and T.S Eliot associated Dostoevsky with madness, either through the peculiarities of his characters or through his hectic writing manner. Strachey remarks that Dostoevsky's books ‘appear to be always trembling on the verge of insanity’.59 References to Dostoevsky in Katherine Mansfield’s letters often point to the ‘delirious’ side of Dostoevsky's plots.60 Modernists regarded Dostoevsky's madness as a positive characteristic. In response to Arthur Power’s protestation that Dostoevsky’s characters are ‘mad, all of them’, Joyce retorted: Madness you may call it … but therein may be the secret of his genius. Hamlet was mad, hence the great drama; some of the characters in the Greek plays were mad; Gogol was mad; Van Gogh was mad; but I prefer the word exaltation, exaltation which can merge into madness, perhaps. In fact all men have had that vein in them; it was the source of their greatness; the reasonable man achieves nothing.61 According to Strachey, this quality of madness enabled Dostoevsky to endow his reader with ‘a new understanding of the mysterious soul of man’.62 Eliot connects his discussion of hallucinations in Dostoevsky's novels to the idea that art can regain its power through returning to the elementary – the argument parallel to Fry’s celebration of the primitive culture. Eliot notes the Russian novelists’ ability to discern basic emotions behind their characters’ complex decisions: The surface of existence coagulates into lumps which look like important simple feelings … which the patient analyst disintegrates into more complex and trifling, but ultimately, if he goes far enough, into various canalizations of something again simple, terrible and unknown. The Russians point to this thing.63 [J.M. Murry.] “Dostoevsky Possessed.” TLS. 22 November 1922. 702. L. Strachey, Spectatorial Essays 177. 60 Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield 1:291; 310. 61 A. Power, Conversations with James Joyce. Ed. C. Hart (London: Millington, 1974) 60. 62 L. Strachey, Spectatorial Essays 178. 63 T.S. Eliot, “Beyle and Balzac.” The Athenaeum. 30 May 1919. 393. 58 59 13 In Britain of the time, Dostoevsky was not perceived as the most experimental writer, despite repeated references to his modernity. It was another Russian author, Chekhov, who was mainly praised for the aesthetic freshness of his works. The limited space of this article does not permit me to outline the details of Chekhov’s reception in early twentieth-century Britain. The essential fact is that the gradual recognition of Chekhov the prose writer (as opposed to that of Chekhov the dramatists) took place in Britain almost simultaneously with the growth of Dostoevsky's popularity. The first English translation of Chekhov appeared in 1903,64 but it was not until 1916, when Chatto and Windus published the first volume of The Tales of Chekhov in Constance Garnett’s translation, that Chekhov became widely known in Britain.65 When addressing the issue of Chekhov’s modernity, the British critics, for example, John Middleton Murry, focused on the ‘aesthetic impression’ of Chekhov’s stories.66 According to Murry, Chekhov’s main innovation was to achieve a unified vision of life before writing a story, which allowed heterogeneous details of the plot merge naturally into one aesthetic whole.67 Similarly, in 1921 Edward Garnett called Chekhov ‘modern’, when commenting on his ‘atmospheric truth and subtle inflexions of tone’.68 Positive reviews of Dostoevsky and Chekhov must be examined as a part of a general modernist campaign for liberation in arts, described by the literary historian D.S. Mirsky (1890 – 1939) in his account of the London cultural scene after the First World War: The new tendencies went far beyond the boundaries of literature, and came out as a great movement for the liberation of the everyday life of the individual from social discipline and social obligation.69 64 A.P. Chekhov, The Black Monk, and Other Stories (1903) and The Kiss, and Other Stories (1908) were both translated by R.E.C. Long and published by Duckworth. They were reviewed by Arnold Bennett in The New Age in 1909. See: A. Bennett, “Tchehkoff.” Books and Persons (London: Chatto and Windus, 1917) 117-9. 65 Swinnerton 174. The thirteen-volume Tales of Chekhov were published between 1916 and 1922. 66 J.M. Murry, “Thoughts on Tchehov” (1919). Idem., Aspects of Literature (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 92. 67 J.M. Murry, “Thoughts on Tchehov.” 93-4. 68 Chekhov: The Critical Heritage. Ed. V. Emeljanow (London : Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981) 212. 69 D.S. Mirsky, The Intelligentsia of Great Britain. Trans. A. Brown (London: Gollancz, 1935) 108-9. 14 If Dostoevsky was associated with the Russian revolution of 1917, through his psychological insights and portrayal of Russian socialists in The Possessed, Chekhov was largely praised for his revolutionary narrative method. In 1923 William Gerhardie, a novelist and author of the first British monograph on Chekhov, argued that the latter liberated literature from ‘affectation’ and ‘insincerity’.70 It was the same search for ‘fresh angles’ of vision that united the modernists in their appreciation of Dostoevsky, Chekhov and the Post-Impressionists.71 Katherine Mansfield remembered her first impression of Vincent van Gogh: Wasn’t that Van Gogh … Yellow flowers – brimming with sun in a pot? … [T]hat, & another of a sea-captain in a flat cap. They taught me something about writing, which was queer – a kind of freedom – or rather, a shaking free.72 Katherine Mansfield’s description of her feelings about Van Gogh is remarkably similar to Woolf’s comments on the impressionistic qualities of Chekhov’s prose: It is giddy, uncomfortable, inconclusive. But imperceptibly things arrange themselves, and we come to feel that the horizon is much wider from this point of view; we have gained a sense of astonishing freedom.73 Woolf and other modernists singled out Dostoevsky and Chekhov for the same qualities which Roger Fry praised in the art of Van Gogh. In Fry’s view, ‘Van Gogh’s morbid temperament forced him to express in paint his strongest emotions, and in the methods of Cézanne he found a means of conveying the wildest and strangest visions conceived by any artist of our time’.74 Fry 70 Chekhov: The Critical Heritage 252. The expression is from Edward Garnett’s review of Chekhov: Chekhov: The Critical Heritage 211. 72 Letter to Dorothy Brett, 5 December 1921. Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield 4:333. 73 V. Woolf, “Tchehov’s Questions” (1918). Essays 2:245. 74 R. Fry, “The Post-Impressionists” (1910). A Roger Fry Reader 83. 71 15 defines Van Gogh as ‘primitive’ in his endeavor to ‘illustrate[] his own soul’.75 Woolf’s comments on Chekhov and Katherine Mansfield’s impressions of Van Gogh correspond with Fry’s search for ‘complete freedom’ in the Post-Impressionists and primitive art. Like Fry in the Post-Impressionists, modernist writers found in Russian literature a spirit that annihilated the restraints forced upon the individual by Western society. Woolf and Fry referred to Dostoevsky’s novels and productions of the Ballets Russes largely when they needed to demonstrate that the modernity in art was to be achieved through exploration of the hidden side of human nature. 75 Idem., “Van Gogh” (1923). Idem., Transformations (London: Chatto and Windus, 1932) 181.