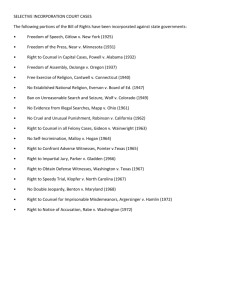

CASE BRIEF Francisco Paco Larrañaga, a Filipino-Spanish citizen, was 27 years old when he and six others were convicted in Cebu for the 1997 abduction, rape and murder of sisters Marijoy and Jacqueline Chiong in 2004. According to the prosecution, Larrañaga, along with seven other men, kidnapped Marijoy and Jacqueline Chiong in Cebu City on 16 July 1997. On the same day, the two women were allegedly raped. Marijoy Chiong was then pushed down into a ravine, while Jacqueline Chiong was beaten. Jacqueline Chiong's body remains missing. The case against Larrañaga centered on the testimony of a co-defendant, David Valiete Rusia. In echange for blanket immunity, he testified. Rusia claimed that he was with Larrañaga in Ayala Center, Cebu early in the evening of July 16, the evening Larrañaga says he was in R&R Restaurant in Quezon City with his friends. Rusia was not known to Larrañaga and only appeared as a "state witness" 10 months after the event. Thirty-five (35) witnesses, including his teacher's and classmates at the Center for Culinary Arts (CA) in Quezon City, testified under oath that he was in Quezon City, when the said crime is said to have been committed. however, the trial court considered theses testimonies irrelevant, rejecting these as coming from "friends of the accused" and they were not admitted. During his trial in the Cebu RTC, defense lawyers sought to present evidence of his whereabouts on the evening of the crime. That Larrañaga, at that time 19 years old, was at a party at the R&R Restaurant along Katipunan Avenue, Quezon City, and stayed there until early morning the following day. After the party, the logbook of the security guard at Larrañaga's condominium indicates that Larrañaga returned to his Quezon City condominium at 2:45 a.m. Rowena Bautista, an instructor and chef at the culinary center, said Larrañaga was in school from 8 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. and saw him again at about 6:30 p.m on July 16. The school's registrar, Caroline Calleja, said she proctored a two-hour exam where Larrañaga was present from 1:30 p.m. Larrañaga attended his second round of midterm exams on July 17 commencing at 8 a.m. Only then did Larrañaga leave for Cebu in the late afternoon of July 17, 1997. Airline and airport personnel also came to court with their flight records, indicating that Larrañaga did not take any flight on July 16, 1997, nor was he on board any chartered aircraft that landed in or departed from Cebu during the relevant dates, except the 5 p.m. PAL flight on July 17, 1997 from Manila to Cebu. Nonetheless, the trial court ruled that Larrañaga required proof of physical impossibility. They failed to establish by clear and convincing evidence that it was physically impossible for him to be in Cebu at the time. 5 May 1999, RTC found co-defendants guilty of the kidnapping and serious illegal detention of Jacqueline Chiong and sentenced them to reclusion perpetua. It decided that there was insufficient evidence to find him guilty of the kidnapping and serious illegal detention with homicide and rape of Marijoy Chiong. The Supreme Court then changed the verdict to a death sentence by lethal injection on the 3 of February 2004. They were found guilty not only of the kidnapping and serious illegal detention of Jacqueline Chiong, but also of the complex crime of kidnapping and serious illegal detention with homicide and rape of Marijoy Chiong. However, the Philippine government abolished death penalty in 2006, and the lives of the seven (7) codefendants were spared. Larrañaga brought his case to the UN Human Rights Committee which found numerous violations of the convict’s rights during the course of the trial, from the lower court to the Supreme Court, and recommended, in 2006, a “commutation of his death sentence and early consideration for release on parole.” Since then Larrañaga remains in jail in Spain, where he was transferred as part of a prisoner exchange treaty in 2009, while his six Filipino co-accused are behind bars in the Philippines. The Spanish government has also lobbied the Philippines on behalf of Larranaga but he cannot be released unless he wins a presidential pardon. He filed an appeal to then President Benigno Aquino. However the Department of Justice rejected the appeal on behalf of the president. APPEAL TO THE HRC HRC VIEW, Communication No. 1421/2005 The complaint The complaint Ground State Party's Comment Violation of article 6 State party death penalty was of the Covenant reintroduced the never abolished by death penalty after the 1987 abolishing it. Constitution. Consideration of the merits In the light of the State party's recent repeal of the death penalty, the Committee > imposition of the considers that this death penalty for claim is no longer a certain crimes is live issue. purely a matter for domestic discretion, save for the limitation that it be imposed only for the "most serious crimes". > not a party to the Second Optional Protocol to the Covenant. violation of article Violation 14 (2) presumption. innocence: of of there was clear evidence of homicide and rape. evaluation of facts It recalls that a and evidence by the criminal appeal Special Heinous opens up the entire Crimes Court and case for review and the Supreme Court that to have oral were manifestly arguments before arbitrary and the Supreme Court amounted to a is not a matter of denial of justice, in right. The Supreme violation of his right Court carefully to be presumed assessed the innocent until evidence before it proved guilty. and decided to disagree with the trial court's imposition of a life sentence on the author and his codefendants. prosecution was based on evidence testimony was from an accomplice corroborated by charged with the disinterested same crime witnesses and compatible with the physical evidence 14 (1) trial court and the Supreme Court were subject to outside pressure from powerful social groups, especially the Chinese-Filipino community, of which the victims are members and decision of the Supreme Court was rendered by the court as a whole, rather than by specific Justices. trial judge did not show sufficient latitude in permitting the defendant to prove this defence, and in particular, excluded several witnesses offered in the alibi defence. which argued for the execution of the defendants. article 14 (1)(3d), prevented from author was not testifying at his own prevented from trial testifying, since the prosecution and the defence agreed to dispense with his testimony 3(e) no equality to call and examine trial court may witnesses dispense with the testimony of witnesses who would offer the same testimonies given by witnesses who already testified right to crossexamine was unfairly restricted It was the right and duty of the trial court to control the cross> cross- examination of examination of the witnesses, both for main prosecution the purpose of had to examine the case as to the facts and the law, and in particular had to make a full assessment of the question of the author's guilt or innocence, it should have used its power to conduct hearings, as provided under national law, to ensure that the proceedings complied with the requirements of a fair trial witness was repeatedly cut short by the trial judge and prematurely terminated to avoid the possibility of harm to the witness > trial judge refused to hear the remaining defense witnesses. 14 3(b) conserving time and protecting the witnesses from prolonged and needless examination. reaffirms that it is for the national courts to evaluate facts and evidence in a particular case. However, bearing in mind the seriousness of the charges involved in the present case, the Committee considers that the trial court's denial to hear the remaining defence witnesses without any further justification other than that the evidence was "irrelevant and immaterial" and the time constraints, while, at the same time, the number of witnesses for the prosecution was not similarly restricted, does not meet the requirements of article 14 counsel did not have sufficient time the trial had to be hen counsel for the to prepare the terminated within defendant requests defense sixty days. an adjournment because he was not given enough time to acquaint himself with the case, the court must ensure that the defendant is given an opportunity to prepare his defense. > adjournment should have been granted 14 (3d) could not choose an effective counsel trial court can appoint a counsel whom it considers competent to enable the trial to proceed. 14 (1) not tried by an no basis for the independent and claim of partiality impartial tribunal and bias on the part of the trial judge because he was the same judge who had informed the author of the charges against him and asked him to enter his plea. Art. 6(2) and article SC failed to correct 14 any of the irregularities of the this is a case involving the death penalty, the trial court should have accepted the author's request for a different counsel, even if this entailed an adjournment of the proceedings. involvement of these judges in these trial and appeal proceedings is incompatible with the requirement of impartiality > involvement of these judges in the preliminary proceedings was such as to allow them to form an opinion on the case prior to the trial and appeal proceedings. This knowledge is necessarily related to the charges against the author and the evaluation of those charges. proceedings before the lower court. Articles 9(3), undue delays in the given the 14(3)(c) and 14(5) proceedings complexity of the case and the fact that the author availed himself of all the remedies available, the courts have acted with all due dispatch Article 7 prolonged period of detention on death row. UN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE Shadow Report September 2012 REMEDY ORDERED commutation of death sentence early consideration for release on parole measures violations in the future to prevent REMEDY PROVIDED Death penalty commuted to life imprisonment along with many others prior to issuance of Committee’s views. Court order in 2007 recognised possibility of parole. Author remains in prison in Spain similar under a prisoner transfer agreement; author maintains release on parole requires steps to be taken by the Philippines. Anticipated release date 28 September 2034. Communication between the parties ongoing. SUMMARY OF COMMUNICATIONS AND KNOWN STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION Francisco Juan Larrañaga v. Philippines, Communication No. 1421/2005, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/87/D/1421/2005 (2006). Summary of facts: Mandatory imposition of the death penalty; presumption of innocence The author, along with six co-defendants, was accused of kidnapping, serious illegal detention, rape and murder. According to the author, he was not in the same city when these crimes were committed. The main prosecution witness was another defendant who was promised immunity from prosecution. During the hearings, the witness admitted for the first time that he had raped one of the victims and the cross examination was cut short when he admitted that he lied about his previous convictions, which should have disentitled him from immunity. There were also allegations that he had been bribed. In response, author's counsel refused to participate in the trial and asked the trial judge to recuse himself - he was summarily found guilty of contempt of court, arrested and imprisoned. The author requested 3 weeks to hire new counsel, but the court refused to adjourn the trial any further, and offered the defendants the opportunity to rehire their counsel, who were in prison. The then court ordered the Public Attorney's Office to assign to the court a team of public attorneys who would act temporarily as defense counsel. Prosecution witnesses were presented, and the court deferred the cross-examination of several of them in view of the defendants' insistence that the lawyer whom they had yet to choose would conduct the cross-examination. The author's newly appointed counsel then asked to cross-examine these witnesses but the court refused. It also refused to grant the new counsel an adjournment to acquaint himself with the case file. Author’s counsel cross-examined again the main prosecution witness, however, in response to a motion from the prosecution, he was discharged as a witness and was granted immunity from prosecution. The court then granted the new counsel 4 days to decide if they wanted to cross-examine the other prosecution witnesses, but counsel refused in protest and the court decided that all the defendants had waived their right to cross-examine prosecution witnesses. Witnesses testified in favor of the author and confirmed that he was in Quezon City immediately before, during and after the alleged crime committed in Cebu City, more than 500 km away. Several pieces of evidence were presented to the court to the same effect. The trial judge refused to hear other witnesses on the ground that their testimony would be substantially the same as the author's other witnesses and he refused to hear evidence from other defense witnesses on the ground that the evidence was "irrelevant and immaterial.” The author was found guilty of the kidnapping and serious illegal detention. The author appealed to the Supreme Court, which did not hear the testimony of any witnesses during the review process, relying solely upon the lower court's appreciation of the evidence. They found the author guilty not only of the kidnapping and serious illegal detention, but also of the complex crime of kidnapping and serious illegal detention with homicide and rape. The author was sentenced to death by lethal injection. A motion for reconsideration was lodged with the Supreme Court, but was rejected. Violations: Article 6, paragraph 1; article 7; and article 14, paragraphs 1, 2, 3 (b), (c), (d), (e), 5 Remedy: In accordance with article 2, paragraph 3, of the Covenant, the State party is under an obligation to provide the authors with an effective remedy, including commutation of his death sentence and early consideration for release on parole. The State party is under an obligation to take measures to prevent similar violations in the future. Follow-up: Death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 2006 along with many others prior to issuance of Committee’s views. Shortly afterwards the death penalty was abolished in the Philippines. In March 2007 a court order recognised that the author was not precluded by the decree abolishing the death penalty to consideration for parole. In October 2009 the author was transferred under a prisoner transfer agreement from the Philippines to Spain. In March 2011 the Spanish courts confirmed that the author’s anticipated release date was 28 September 2034. In November 2011 the case was raised in the Human Rights Committee and the Special Rapporteur on follow-up agreed to look into the case and to consider whether the Philippines has properly implemented the Committee’s views. The Special Rapporteur also said he would also start from the “strong presumption” that, as Spain has obligations under the Optional Protocol, it should also be involved in the implementation of the remedy. In December 2011 the author’s representatives wrote to the Committee urging that the following steps to be taken: i. ii. iii. iv. The Special Rapporteur, through the Secretariat, should send a reminder to the Philippines and a letter to Spain seeking its views on follow up If no information is forthcoming by the given deadline, the Special Rapporteur should seek to organize a meeting with a representative of the Philippines and Spain from the Permanent Mission in Geneva or New York, to discuss the facilitation of implementation If no information is forthcoming from the Philippines, a follow-up mission to the Philippines should be organised because it has experienced particular difficulties with the implementation of the Committee’s recommendations If insufficient or no follow-up information has been provided, the Committee should seek information from the Philippines during the examination of its periodic report in October 2012 under article 40 of the Covenant; and in respect of Spain during its next periodic report The Government responded in May 2012, attempting to reopen the merits on some of the violations held by the Committee, and alleging that the Government of Spain was responsible for the terms of continuation of imprisonment. The author responded again in June 2012. No further progress has been made and the author remains in prison. (Communication with the author’s representative). PRISONER EXCHANGE TREATY As a dual citizen of the Philippines and Spain, Paco Larrañaga was moved to a Spanish prison under what is known as the RP-Spain Transfer of Sentenced Persons Agreement (TSPA). Signed on May 18, 2007 and approved by the senates of both countries, this treaty allows foreign prisoners to be sent to their countries of nationality to serve out the rest of their sentences. > The treaty allows a person sentenced to serve imprisonment in the Philippines to serve his sentence in a jail in Spain and vice versa. > Once the transfer is accomplished, the sentence enforcement shall be governed by the laws of the State where the convict was transferred. Only the sentencing State, the Philippines in the case of Larrañaga, may grant pardon, amnesty, or commutation of sentence. However, Spain may ask the Philippines to grant pardon, amnesty, or commutation of the sentence by submitting an application with sufficient grounds. > PACO LATER Paco remains in prison but now benefits from an additional privilege of the Spanish penal system: Due to time already served, he is granted occasional therapeutic leaves (a few days every month) at the prison board's discretion, which means he receives permission to leave during daytime hours to study and work. > Six years after being transferred from the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa City to a Spanish prison, Francisco “Paco” Osmeña Larrañaga is working part-time as a chef. > allowed to leave his cell without a security escort and head to work at the restaurant. He then returns at night to his cell. > Paco studied hotel and restaurant management under a temporary license granted by the Prison Support Team in a penitentiary. > right to work by prisoners is guaranteed under the Spanish Constitution of 1978, which states that prisoners have “the right to paid employment.” > In 2009, Paco was transferred to a maximum-security prison in Soto del Real, Madrid, Spain named the Madrid Central Penitentiary. > four years later, Larrañaga was moved to a second-grade prison in Martutene, San Sebastian, Spain. It was in Martutene that Larrañaga was granted special licenses for his education and work. WHAT HAPPENED TO THE DEATH PENALTY BY LETHAL INJECTION? > In April 2006, President Arroyo commuted the sentences of 1,230 death row and ultimately signed RA 9346 in June 2006 which abolished the use of capital punishment. Congress had overwhelmingly supported the abolishment of the practice in their vote for the RA earlier that month replacing the death penalty with life imprisonment and reclusion perpetua. > In 2007, the Philippines ratified the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which requires countries to abolish the death penalty. Countries that are parties to the covenant and the protocol cannot reinstate the death penalty without violating their obligations under international human rights law.