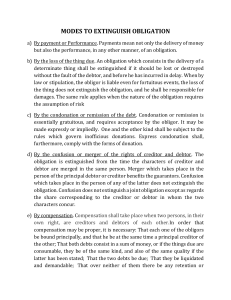

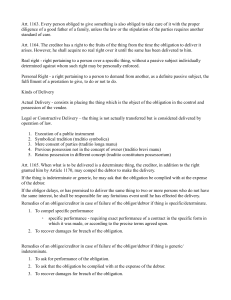

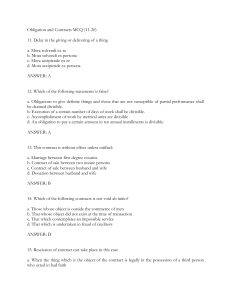

LAW ON OBLIGATIONS A. IN GENERAL 1. DEFINITION Article 1156. An obligation is a juridical necessity to give, to do or not to do. JURIDICAL NECESSITY: Art. 1423 provides that obligations are either natural or civil. Art. 1156 provides the definition of civil obligations. Under Art. 1423, civil obligations give a right of action to compel their performance or fulfillment. In this sense, there is juridical necessity to perform the obligation because it can result in judicial or legal sanction. 2. KINDS OF OBLIGATIONS AS TO BASIS AND ENFORCEABILITY Art. 1423. Obligations are civil or natural. Civil obligations give a right of action to compel their performance. Natural obligations, not being based on positive law but on equity and natural law, do not grant a right of action to enforce their performance, but after voluntary fulfillment by the obligor, they authorize the retention of what has been delivered or rendered by reason thereof. Some natural obligations are set forth in the following articles. CIVIL OBLIGATIONS VS. NATURAL OBLIGATIONS: Basis Enforceability CIVIL Positive, man-made law Grants a right of action to compel performance or fulfillment NATURAL Equity and natural law Does not grant a right of action for fulfillment. However, it can still be enforced: 1. If the plaintiff required fulfillment before a court and there is no objection; or 2. if voluntarily fulfilled, creditor can still retain the benefits of fulfillment. EXAMPLE: X is indebted to Y, but the debt already prescribed. Since the action already prescribed, the obligation is converted from civil to natural where X can no longer be compelled by court action to pay, only by his Note that what prescribed is the “action” and not the obligation. If still fulfilled after the period has expired, debtor can no longer demand the return of what has been delivered. Art. 1428 provides: Art. 1428. When, after an action to enforce a civil obligation has failed the defendant voluntarily performs the obligation, he cannot demand the return of what he has delivered or the payment of the value of the service he has rendered. Some authors include a third classification: Moral Obligations. But these can be under Natural Obligations as to their enforceability since this obligation cannot be enforced through court action. Examples of such is the obligation of Muslims not to eat pork, or Catholics to go to church every Sunday. 3. ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF OBLIGATION a. b. c. d. Active subject (creditor) - obligee Passive subject (debtor) - obligor Prestation – subject matter of the obligation – either to give, to do or not to do. Vinculum (Efficient Cause) – the reason why the obligation exists. – juridical tie. ILLUSTRATION: A promised to give B his television set. In this illustration, A is the obligor/debtor; B is the oblige/creditor; giving the television set is the prestation; the agreement or contract is the efficient cause. B. SOURCES OF OBLIGATIONS: Art. 1157. Obligations arise from: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) 1. Law; Contracts; Quasi-contracts; Acts or omissions punished by law; and Quasi-delicts. LAW (Obligations ex lege) Art. 1158. Obligations derived from law are not presumed. Only those expressly determined in this Code or in special laws are demandable, and shall be regulated by the precepts of the law which establishes them; and as to what has not been foreseen, by the provisions of this Book. The above article means that the obligation must be clearly set forth in the law. Examples of obligations arising from law are: a. Duty of support; b. Duty to pay taxes. 2. CONTRACTS (Obligations ex contractu) Art. 1159. Obligations arising from contracts have the force of law between the contracting parties and should be complied with in good faith. Art. 1305. A contract is a meeting of minds between two persons whereby one binds himself, with respect to the other, to give something or to render some service. Once a contract is entered into, the parties are bound by its terms and cannot, without valid reason withdraw therefrom. 3. QUASI-CONTRACTS (Obligations ex quasi-contractu) The juridical relation resulting from lawful, voluntary and unilateral acts by virtue of which the parties become bound to each other to the end that no one will be unjustly enriched or benefited at the expense of another. PRINCIPAL KINDS OF QUASI-CONTRACTS: A. NEGOTIORUM GESTIO– the voluntary management of the property or affairs of another without the knowledge or consent of the latter. B. SOLUTIO INDEBITI – the juridical relation which is created when something is received when there is no right to demand it and it was unduly delivered through mistake. Requisites: 1. 2. 4. There is no right to receive the thing delivered The thing was delivered through mistake DELICT (Obligations ex maleficio or ex dlicto) Delict is an act or omission punishable by law which may be governed by the Revised Penal Code, other penal laws, or the Title on Human Relations under the Civil Coe. Revised Penal Code: Art. 100. Civil liability of a person guilty of felony. — Every person criminally liable for a felony is also civilly liable Note, also, that under the Rules of Court, whenever a criminal action is instituted, the civil action for the civil liability is impliedly instituted therewith. Art. 104. What is included in civil liability. — The civil liability established in Articles 100, 101, 102, and 103 of this Code includes: 1. Restitution; 2. Reparation of the damage caused; 3. Indemnification for consequential damages. Recovery of civil liability requires only preponderance of evidence whle to be liable criminally, proof beyond reasonable doubt is required. It follows then, that if an accused is acquitted of criminal charges due to reasonable doubt, he may still be held civilly liable if the same is proven by preponderance of evidence. 5. QUASI-DELICTS (Obligations ex quasi-delicto or ex quasi-maleficio) Art. 2176. Whoever by act or omission causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is obliged to pay for the damage done. Such fault or negligence, if there is no pre-existing contractual relation between the parties, is called a quasi-delict and is governed by the provisions of this Chapter Requisites: a. b. c. d. There There There There must must must must be be be be an act or omission; fault or negligence; damage caused; a direct relation of cause and effect between the act or omission and the damage; Example: While driving recklessly, the driver hit a pedestrian and the latter was injured. Here the act was driving recklessly; there was negligence, since the required degree of care was not met; there was damage to the pedestrian who was injured; and the cause of the damage was the reckless driving of the driver. C. KINDS OF CIVIL OBLIGATIONS 1. AS TO PERFECTION AND EXTINGUISHMENT PURE OBLIGATIONS Art. 1179. Every obligation whose performance does not depend upon a future or uncertain event, or upon a past event unknown to the parties, is demandable at once. Every obligation which contains a resolutory condition shall also be demandable, without prejudice to the effects of the happening of the event. A pure obligation is one without a condition or a term and as such, demandable at once. CONDITIONAL OBLIGATIONS Art. 1181. In conditional obligations, the acquisition of rights, as well as the extinguishment or loss of those already acquired, shall depend upon the happening of the event which constitutes the condition. Conditions: are uncertain events which wields an influence on a legal relationship. Kinds of Conditions as to when the obligation should be performed suspensive resolutory happening of which gives rise to the obligation happening of which extinguishes the rights already existing as to whom or where it depends potestative depends on the will of the party to the juridical relation as to capacity to be performed in parts casual mixed divisible indivisible conjunctive depends on chance partly depends on will of the party and partly on chance can be performed in parts cannot be performed in parts all must be performed alternative positive negative express implied possible impossible only one must be performed act omission stated merely inferred can be fulfilled cannot be fulfilled either physically or legally as to number of obligations are to be performed when there are several of them as to nature as to how made known to the other party as to whether the obligation can be fulfilled Potestative Condition: Art. 1182. When the fulfillment of the condition depends upon the sole will of the debtor, the conditional obligation shall be void. If it depends upon chance or upon the will of a third person, the obligation shall take effect in conformity with the provisions of this Code. Potestative conditions which render the obligation void are those which are suspensive and potestative on the part of the debtor not those which are resolutory or potestative on the part of the creditor. This is so, because if it were allowed by law, there is a possibility that the obligation will never arise. Constuctive or Presumed Fulfillment: Art. 1186. The condition shall be deemed fulfilled when the obligor voluntarily prevents its fulfillment. EXAMPLE: In a contract for a piece of work, where A hired B as contractor to build his house where 50% of the contract price is payable as downpayment and 50% upon completion. If A voluntarily prevented the happening of the condition for the payment of the remaining 50%, i.e., the completion of the house, say by preventing the workers from entering the premises, the condition is already deemed fulfilled and B would be entitled to the remaining 50%. Except: if the prevention is pursuant to a valid right, say, workers are not following the plans, or the contractor uses inferior materials – the debtor is not compelled to pay. He can even ask for the demolition of the work already completed at the expense of the contractor. Impossible Conditions: Art. 1183. Impossible conditions, those contrary to good customs or public policy and those prohibited by law shall annul the obligation which depends upon them. If the obligation is divisible, that part thereof which is not affected by the impossible or unlawful condition shall be valid. Impossibility: can either be: 1. Physically impossible – such as a condition requiring the debtor to go to the sun; or 2. Legally impossible – such as when it is contrary to law, good customs, public policy, such as a condition requiring the debtor to kill somebody. Effect: 1. When an impossible condition is imposed in an obligation to do, the obligation and the condition are treated as void since the debtor knows that no fulfillment can be done and therefore is not serious about being liable. 2. In obligations not to do or if the condition is negative, the impossible condition can just be disregarded and the obligation remains. Example: I will sell to you my land if you will not draw a circle with three sides. Here, the condition is actually always fulfilled. Example2: I will sell to you my land if you do not sell illegal drugs. Note that such effects are applicable only to obligations and contracts, not to testamentary dispositions and donations, where impossible or illegal conditions are just disregarded. Effect of fulfillment of obligations as to fruits: Art. 1187. The effects of a conditional obligation to give, once the condition has been fulfilled, shall retroact to the day of the constitution of the obligation. Nevertheless, when the obligation imposes reciprocal prestations upon the parties, the fruits and interests during the pendency of the condition shall be deemed to have been mutually compensated. If the obligation is unilateral, the debtor shall appropriate the fruits and interests received, unless from the nature and circumstances of the obligation it should be inferred that the intention of the person constituting the same was different. In obligations to do and not to do, the courts shall determine, in each case, the retroactive effect of the condition that has been complied with. As to the obligation – the happening of the condition retroacts to the day the obligation was constituted. Example: In 2017, X promised to sell his land to Y if the latter passes the board exam by May 2018. Y passed the board exam on May 2018. In this case, if Y donated the property prior to passing the board exam, it is a valid donation since the land is not considered future property since the happening of the condition would retroact to the day the obligation was constituted. This rule, however, is applicable only to consensual contracts, not to real ones, since the latter would require delivery for its perfection. No retroactivity as to: 1. Fruits or interests Example: in the earlier example, Y would not be entitled to the fruits of the land prior to the happening of the condition and X would not be entitled to interest on the purchase price since they are deemed mutually complensated. Unilateral obligations: in unilateral obligations, the debtor as a rule, is entitled to the fruits, unless a contrary intention appears. 2. Period of prescription Condition where obligation is treated as one with a period: Art. 1180. When the debtor binds himself to pay when his means permit him to do so, the obligation shall be deemed to be one with a period, subject to the provisions of Article 1197. “MEANS TO PAY” – valid obligation with a period, because the remedy of the creditor is to go to court once the debtor has the means to pay. Positive conditions with a deadline: Art. 1184. The condition that some event happen at a determinate time shall extinguish the obligation as soon as the time expires or if it has become indubitable that the event will not take place. Example: I will give you my land if you marry X by the end of the year. If X dies by June of the same year, the obligation is deemed extinguished already since it is already indubitable that the event will not take place. Rules as to improvement, loss or deterioration: Art. 1189 provides that in case of obligations to give a specific or determinate thing is subject to a suspensive condition, the following rules shall be observed in case of the improvement, loss or deterioration of the thing during the pendency of the condition: 1. The thing is lost (when it perishes, goes out of commerce, or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or it cannot be recovered) a. Without fault of the debtor – obligation is extinguished; b. With fault of the debtor – debtor is liable for damages. 2. The thing deteriorartes a. Without fault of the debtor – the impairment is borne by the creditor; b. With fault of the debtor – the creditor has two options: (1) To exact fulfillment and ask for damages (2) Rescission with damages 3. There is improvement a. By nature or time – the improvement will inure to the benefit of the creditor b. At the expense of the debtor – he shall have no other right than that granted to the usufructuary, e.g., he may remove the improvement if it will not cause damage to the thing. The above rules likewise applies to obligations with a period. Effect of happening of a resolutory condition: Art. 1190. When the conditions have for their purpose the extinguishment of an obligation to give, the parties, upon the fulfillment of said conditions, shall return to each other what they have received. xxx In the event that a resolutory condition is fulfilled, it will be as if there was no obligation to begin with and the parties are required to return to each other what they have received. Example: X gave Y his car upon the condition that Y will not go to a casino. Y went to a casino. In this case, the obligation is extinguished and it will be as if there was obligation to begin with. Accordingly, Y is required to return to X the parcel of land together with any fruits received therefrom. OBLIGATIONS WITH A PERIOD/TERM: Art. 1193. Obligations for whose fulfillment a day certain has been fixed, shall be demandable only when that day comes. Obligations with a resolutory period take effect at once, but terminate upon arrival of the day certain. A day certain is understood to be that which must necessarily come, although it may not be known when. If the uncertainty consists in whether the day will come or not, the obligation is conditional, and it shall be regulated by the rules of the preceding Section. (1125a) A period is a certain length of time which determines the effectivity or the extinguishment of the obligation. Unlike a condition, a period is certain to arrive or must necessarily come even though it may not be known when. KINDS OF TERM: 1. Definite – specific date, e.g. Dec. 31, end of the year this year, within 6 months; 2. Indefinite – period may arrive upon the fulfilment of a certain event which is certain to happen. E.g., death. or 3. 4. 5. Legal – imposed or provided by law, e.g. filing of taxes; obligation to give support – within the first 5 days of the month. Voluntary – agreed upon by the parties. Judicial – those fixed by courts. As to effect, a term/period may be: 1. Ex die – a period with a suspensive effect. 2. In diem – a period with a resolutory effect. When may the court fix the period? 1. Under Art. 1191, par. 3: Art. 1191. The power to rescind obligations is implied in reciprocal ones, in case one of the obligors should not comply with what is incumbent upon him. The injured party may choose between the fulfillment and the rescission of the obligation, with the payment of damages in either case. He may also seek rescission, even after he has chosen fulfillment, if the latter should become impossible. The court shall decree the rescission claimed, unless there be just cause authorizing the fixing of a period. This is understood to be without prejudice to the rights of third persons who have acquired the thing, in accordance with Articles 1385 and 1388 and the Mortgage Law. 2. Under Art. 1197: Art. 1197. If the obligation does not fix a period, but from its nature and the circumstances it can be inferred that a period was intended, the courts may fix the duration thereof. The courts shall also fix the duration of the period when it depends upon the will of the debtor. In every case, the courts shall determine such period as may under the circumstances have been probably contemplated by the parties. Once fixed by the courts, the period cannot be changed by them There are two instances when the court may fix a period as provided above: 1. The parties intended a period, but no period was fixed; 2. The period depends solely on the will of the debtor. Benefit of the period: Art. 1196. Whenever in an obligation a period is designated, it is presumed to have been established for the benefit of both the creditor and the debtor, unless from the tenor of the same or other circumstances it should appear that the period has been established in favor of one or of the other PRESUMPTION: is that the period was fixed for the benefit of both parties. EXCEPTION: when from the tenor of the obligation or other circumstances, it was only established for one or the other. Example of the exemption: use of the words ”on or before” – for the benefit of the debtor. As such, the it can be seen from the tenor of the condition that the benefit was for the debtor who can perform or fulfill the obligation even prior to the expiration of the term. Debtor’s loss of benefit of the period: a. When after the obligation has been contracted, he becomes insolvent, unless he gives a guaranty or security for the debt; The insolvency need not be judicially declared, it is sufficient that the debtor’s liabilities are more than his assets. Example: D is indebted to C for P100,000 due on June 30, 2018. D became insolvent on March 31, 2018. In this case, the indebtedness is immediately demandable since D loses the right to make use of the period. b. When he does not furnish to the creditor the guaranties or securities which he has promised; Example: D borrowed P100,000 from C payable on December 31, 2018 and promised to deliver his diamond ring as security therefor. However, D lost the diamond ring prior to delivery. In this case, the P100,000 is due immediately since he failed to provide the security as promised. c. When by his own acts he has impaired said guaranties or securities after their establishment, and when through a fortuitous event they disappear, unless he immediately gives new ones equally satisfactory; Example: D borrowed P100,000 from C payable on December 31, 2018 and mortgaged his house as security. On June 30, 2018, the house was destroyed by a typhoon. The debt shall be due and demandable on June 30, 2018 unless the debtor can provide a security which is equally satisfactory. d. When the debtor violates any undertaking, in consideration of which the creditor agreed to the period; Example: D borrowed P100,000 from C payable on December 31, 2018 upon the condition that D would not go to any casino. D went to a casino on March 31, 2018. The debt shall be demandable on March 31, 2018. e. When the debtor attempts to abscond. An attempt on the part of the debtor to abscond is a sign of bad faith and intention not to comply with the obligation. What is material here is the intent of the debtor in absconding. Thus, if he merely went out of the country for a vacation, the debtor does not lose the benefit of the period since there was no intention to defraud the creditor. 2. AS TO PLURALITY OF PRESTATION a. b. CONJUNCTIVE usually use the word “and” compared to alternative obligations which use the word “or”. ALTERNATIVE Art. 1199. A person alternatively bound by different prestations shall completely perform one of them. The creditor cannot be compelled to receive part of one and part of the other undertaking. Art. 1200. The right of choice belongs to the debtor, unless it has been expressly granted to the creditor. The debtor shall have no right to choose those prestations which are impossible, unlawful or which could not have been the object of the obligation. Alternative Obligations: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Where several objects are due, the fulfillment of one is sufficient. Right of Choice: generally, it belongs to the debtor, except: a. When expreslly granted to the creditor, i.e., it cannot be implied; or b. When the right of choice is given to a third party. The debtor’s right of choice is limited in such a way that he cannot choose any prestation which is impossible or unlawful. The choice, to take effect, must be communicated. The communication of the choice made is technically called “concentration.” The choice cannot be part of one and part of another. When from all the choices, only one is practicable, the debtor shall lose the right of choice. Logically, the obligation would be to deliver that which remains. If through the creditor’s acts, the debtor cannot make a choice, the debtor may rescind the contract with damages. If the choice is with the debtor and when through his fault, all prestations are lost or has become impossible, he shall be liable to the creditor for the value of the last thing which disappeared. If the choice is with the creditor and until a choice is communicated: a. If one of the things is lost through a fortuitous event, the creditor can choose from the remaining; b. If the loss of one of the things occurs through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may: (1) Claim any of those subsisting, or (2) The price of that which was lost plus damagages; c. If all the things are lost through the fault of the debtor, the choice by the creditor shall fall upon the price of any one of them, also with indemnity for damages. c. FACULTATIVE Art. 1206. When only one prestation has been agreed upon, but the obligor may render another in substitution, the obligation is called facultative. The loss or deterioration of the thing intended as a substitute, through the negligence of the obligor, does not render him liable. But once the substitution has been made, the obligor is liable for the loss of the substitute on account of his delay, negligence or fraud. Facultative Obligations: there are more than one prestation, but only one is demandable, unlike in alternative where any of the prestations may be demandable. Right to substitute: is always with the debtor. He cannot be compelled to make the substitution. Alternative vs. Facultative Obligation: As to contents of the obligation As to nullity As to choice As to effect of loss ALTERNATIVE OBLIGATION there are various prestations all of which constitute parts of the obligation the nullity of one prestation does not invalidate the obligation, which is still in force with respect to those which have no vice the right to choose may be given to the creditor only the impossibility of all the prestations due without fault of the debtor extinguishes the obligation FACULTATIVE OBLIGATION only ONE principal prestation constitutes the obligation, the accessory being only a means to facilitate payment. the nullity of the principal prestation invalidates the obligation & the creditor cannot demand the substitute even when this is valid only the debtor can choose the substitute prestation. the impossibility of the principal prestation is sufficient to extinguish the obligation, even if the substitute is possible Loss of the thing or impossibility of the prestation: whether it results in the extinguishment of the obligation: 1. Conjunctive: Yes. 2. Alternative: Specific things. Depending on who has the right of choice. a. If there had already been a communication of choice: the obligation has already been simple. The lost of the chosen prestation extinguishes the obligation. b. Due to the fault of the debtor, if the right belongs to the debtor: i. Perform remaining obligations; ii. No liability for damages. c. Due to the fault of the debtor, if the right of choice belongs to the creditor: i. Demand value of thing lost plus damages; ii. Choose from the remaining plus damages. *if due to fortuitous event, the debtor may perform the obligation as to the choice of the creditor from the remaining prestations. d. 3. Due to the fault of the creditor, if the right of choice belongs to the debtor; i. He may rescind the obligation (option only, not automatic) plus damages; ii. Perform one of the remaining prestations + damages. Facultative: It depends: a. If the loss happened BEFORE substitution, and i. the prestation lost is the SUBSTITUTE: not extinguished; ii. the prestation lost is the PRINCIPAL: extinguished. b. If the loss happened AFTER substitution, and i. The prestation lost is SUBSTITUTE: extinguished. ii. The prestation lost is PRINCIPAL: not extinguished. IF ALL things lost: if right of choice is with the: a. b. Debtor: value of the last prestation lost (may be indicative of his choice. The value of the last prestation was intended to be the one to be delivered) Creditor: value of any of the prestation. 3. AS TO RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS OF MULTIPLE PARTIES a. SOLIDARY OBLIGATION A solidary obligation is one in which the debtor is liable for the entire obligation or each creditor is entitled to demand the whole obligation. If there is only one obligation, it is a solidary obligation. Art. 1207. The concurrence of two or more creditors or of two or more debtors in one and the same obligation does not imply that each one of the former has a right to demand, or that each one of the latter is bound to render, entire compliance with the prestation. There is a solidary liability only when the obligation expressly so states, or when the law or the nature of the obligation requires solidarity. (1137a) Olidary obligation arises when the obligation: 1. Expressly so states (stipulated); Terms which may indicate solidarity: a. Mancomunada solidaria b. Joint & several; c. In solidum; d. Juntos o separadamente; e. Individually and collectively. f. Individually g. Collectively h. Separately i. Distinctively j. Respectively k. Severally l. “I promise to pay” signed by more than one individual 2. When the law requires solidarity; a. When two or more heirs take possession of the estate, they are solidarily liable for the loss or destruction of a thing devised or bequeathed. (Art. 927) b. Even when the agent has exceeded his authority, the principal is solidarily liable with the agent if the former allowed the latter to act as though he had full powers. (Art. 1911) c. When there are two or more bailees to whom a thing is loaned in the same contract, they are liable solidarily. (Art. 1945) d. The responsibility of two or more payees, when there has been payment of what is not due, is solidary. (Art. 2157) e. The responsibility of two or more persons who are liable for quasi-delict is solidary. (Art. 2194) 3. When the nature of the obligation requires solidarity. ENFORCEMENT OF SOLIDARY OBLIGATIONS: 1. The debtor may pay any one of the solidary creditors; but if any demand, judicial or extrajudicial, has been made by one of them, payment should be made to him. 2. Novation, compensation, confusion or remission of the debt, made by any of the solidary creditors or with any of the solidary debtors, shall extinguish the obligation: a. The creditor who may have executed any of these acts, as well as he who collects the debt, shall be liable to the others for the share in the obligation corresponding to them. b. The remission made by the creditor of the share which affects one of the solidary debtors does not release the latter from his responsibility towards the co-debtors, in case the debt had been totally paid by anyone of them before the remission was effected. c. The remission of the whole obligation, obtained by one of the solidary debtors, does not entitle him to reimbursement from his co-debtors. 3. A solidary debtor may, in actions filed by the creditor, avail himself of all defenses which are derived from the nature of the obligation and of those which are personal to him, or pertain to his own share. With respect to those which personally belong to the others, he may avail himself thereof only as regards that part of the debt for which the latter are responsible. Examples of Total Defenses: a. Payment by another co-debtor, as to a subsequent demand of a creditor; b. If the contract is void; c. If the obligation has prescribed. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Payment made by one of the solidary debtors extinguishes the obligation. If two or more solidary debtors offer to pay, the creditor may choose which offer to accept. He who made the payment may claim from his co-debtors only the share which corresponds to each, with the interest for the payment already made. If the payment is made before the debt is due, no interest for the intervening period may be demanded. When one of the solidary debtors cannot, because of his insolvency, reimburse his share to the debtor paying the obligation, such share shall be borne by all his co-debtors, in proportion to the debt of each. The creditor may proceed against any one of the solidary debtors or some or all of them simultaneously. The demand made against one of them shall not be an obstacle to those which may subsequently be directed against the others, so long as the debt has not been fully collected. Payment by a solidary debtor shall not entitle him to reimbursement from his co-debtors if such payment is made after the obligation has prescribed or become illegal. ILLUSTRATION: A, B, C, D and E are solidarily liable to X and Y, solidary creditors, for P10,000. 1. X or Y can demand the whole P10,000 from any of the solidary debtors. 2. A, B, C, D or E then could be made liable for the whole P10,000. 3. If it turns out that A is a minor (defense personal to him), the liability shall be proportionately decreased as to his share – P2,000 (P10,000/5). As such, B, C, D or E can validly raise A’s minority as a defense and can be made liable for P8,000 only. 4. 5. 6. 7. b. If it turns out that A is insolvent, this is not a defense available against the creditor/s. As such, B, C, D or E can be made liable to pay the whole P10,000. If B pays, he can seek reimbursement from the solvent debtors their respective share plus their share of the insolvent debtor’s share, or P2,500 each (P2,000 individual share + P500 from A’s share [P2,000/4]) If one of the solidary creditors condoned the whole debt, say X, he shall be liable to Y for his share in the debt. If one of the solidary debtors obtained the condonation or remission of the debt, say A, he is NOT entitled to reimbursement from his co-debtors. If X condoned the share of A – B, C, D or E can only be made liable for the remaining debt, i.e., P8,000. But A’s liability will not be affected if any of the remaining debtors already paid the whole obligation prior to the condonation or remission. JOINT OBLIGATIONS: If none of the above circumstances, which would give rise to solidarity, are present, the obligation is considered joint. A joint obligation is one in which each of the debtors is liable only for a proportionate part of the debt or each creditor is entitled only to a proportionate part of the credit. In joint OBLIGATIONS, there are as many OBLIGATIONS as there are debtors multiplied by the number of creditors. EFFECTS: 1. 2. 3. 4. The demand by one creditor upon one debtor, produces the effects of default only with respect to the creditor who demanded & the debtor on whom the demand was made, but not with respect to the others; The interruption of prescription by the judicial demand of one creditor upon a debtor does not benefit the other creditors nor interrupt the prescription as to other debtors. On the same principle, a partial payment or acknowledgement made by one of several joint debtors does not stop the running of the statute of limitations as to the others; The vices of each obligation arising from the personal defect of a particular debtor or creditor does not affect the obligation or rights of the others; The insolvency of a debtor does not increase the responsibility of his co-debtors, nor does it authorize a creditor to demand anything from his co-creditors; ILLUSTRATION: A, B, C, D and E are liable to X and Y for P10,000. 1. Here, there is nothing in the problem which would suggest that the parties agreed to solidarity in debt or credit, nor the law or the nature of the obligation require the same. Accordingly, the debtors are joint debtors, and the creditors are joint creditors. 2. Accordingly, since there are 5 joint debtors and 2 joint creditors, there are 10 debts (5 x 2 – multiplying the number of joint debtors with the number of joint creditors), of P1,000 each as follows: A is liable for P1,000 to A is liable for P1,000 to B is liable for P1,000 to B is liable for P1,000 to C is liable for P1,000 to C is liable for P1,000 to D is liable for P1,000 to D is liable for P1,000 to E is liable for P1,000 to E is liable for P1,000 to 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. c. X Y X Y X Y X Y X Y Accordingly, X can only collect P1,000 each from A, B, C, D or E; or A is liable only for P1,000 to X or Y. If A turns out to be a minor, this does not, in any way, affect the liabilities of B, C, D or E. If A turns out to be insolvent, this does not, in any way, affect the liabilities of B, C, D or E. As such, they will not share in the debt of A. If X and Y are solidary creditors, there are only 5 debts (5 joint debtors * 1 creditor) or P2,000 each (P10,000/5). As such, X or Y can collect P2,000 each from A, B, C, D or E. If A, B, C, D and E are solidary debtors, there are only 2 debts (1 debtor * 2 joint creditors) of P5,000 each (P10,000/2). As such, X can collect P5,000 from any of the debtors; and any of the debtors can be made liable for the whole P5,000 debt due to X and P5,000 debt due to Y. DISJUNCTIVE This is not covered by New Civil Code. In this case, there are 2 or more creditors and 2 or more debtors but they are named disjunctively as debtors and creditors in the alternative. The rules on solidary obligations must apply because if rules on alternative obligations will be applied then the debtor will generally be given the choice to whom shall he give payment. Example: A binds himself to pay P100 either to X or Y; A or B will pay 100 to X. 4. AS TO PERFORMANCE OF PRESTATION a. Joint Indivisible Art. 1209. If the division is impossible, the right of the creditors may be prejudiced only by their collective acts, and the debt can be enforced only by proceeding against all the debtors. If one of the latter should be insolvent, the others shall not be liable for his share. Art. 1224. A joint indivisible obligation gives rise to indemnity for damages from the time anyone of the debtors does not comply with his undertaking. The debtors who may have been ready to fulfill their promises shall not contribute to the indemnity beyond the corresponding portion of the price of the thing or of the value of the service in which the obligation consists. (1150) In determining whether an obligation is divisible or indivisible, the question asked should be: whether the obligation is capable of partial performance? If it is, the obligation is considered divisible. The indivisibility of an obligation does not necessarily give rise to solidarity. Nor does solidarity of itself imply indivisibility. Example: A and B are jointly liable to X for the delivery of a particular TV set worth P10,000. 1. Here, the obligation is indivisible, since there can be no partial delivery of a TV set. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. But the obligations of A and B are joint. As such, to require compliance, X must proceed against ALL debtors. As such, demand must be made against all of them. If it turns out that A is insolvent, B shall be liable only to X for his share, or P5,000 (P10,000 value of the TV divided by 2) and he is not liable for the share of A. If B was ready to comply, but A was not, X is entitled to damages. But B is not liable therefor since he was ready to comply with his undertaking. B can only be made liable for his proportionate share. If none was ready to comply, any of A or B can be made liable for damages. GENERAL RULE: the creditor cannot be compelled to accept partial performance. EXCEPTIONS: 1. If stipulated; 2. If the obligation is divisible; 3. If the obligation is partially liquidated and partially unliquidated, the liquidated portion may already be performed; 4. An obligation which would require a number of days to be performed, it may be considered divisible by operation of law. b. Solidary Indivisible Example: if in the earlier illustration, A and B are solidarily liable, X can demand the car from either A or B, subject to reimbursement of the other. Obligations deemed indivisible: 1. 2. 3. Obligation to give definite things Those not susceptible of partial performance If capable of partial performance but the law or the intention of the parties treats it as indivisible. Obligations deemed divisible: 1. 2. 3. 4. The object of the obliation is the execution of a certain number of days of work When the object is the accomplishment of work by metrical units When the purpose of the obligation is to pay a certain amount in installments When the object of the obligation is the accomplishment of work susceptible of partial performance. 5. OBLIGATION WITH A PENAL CLAUSE Art. 1226. In obligations with a penal clause, the penalty shall substitute the indemnity for damages and the payment of interests in case of noncompliance, if there is no stipulation to the contrary. Nevertheless, damages shall be paid if the obligor refuses to pay the penalty or is guilty of fraud in the fulfillment of the obligation. The penalty may be enforced only when it is demandable in accordance with the provisions of this Code. (1152a) GENERAL RULE: the penalty shall substitute the indemnity for damages and payment of interests in case of non-compliance. EXCEPTIONS: 1. If there is stipulation to the contrary; 2. If the debtor refuses to pay the penalty; 3. If the debtor is guilty of fraud in the fulfilment of the obligation. Art. 1227. The debtor cannot exempt himself from the performance of the obligation by paying the penalty, save in the case where this right has been expressly reserved for him. Neither can the creditor demand the fulfillment of the obligation and the satisfaction of the penalty at the same time, unless this right has been clearly granted him. However, if after the creditor has decided to require the fulfillment of the obligation, the performance thereof should become impossible without his fault, the penalty may be enforced. (1153a) Expressly reserved: does not require that it be stipulated, it may be inferred from the nature of the obligation. Art. 1228. Proof of actual damages suffered by the creditor is not necessary in order that the penalty may be demanded. (n) Art. 1229. The judge shall equitably reduce the penalty when the principal obligation has been partly or irregularly complied with by the debtor. Even if there has been no performance, the penalty may also be reduced by the courts if it is iniquitous or unconscionable. (1154a) GROUNDS FOR REDUCTION OF PENALTY: 1. When the principal obligation has been partly or irregularly complied with. 2. When the same is iniquitous or unconscionable. Art. 1230. The nullity of the penal clause does not carry with it that of the principal obligation. The nullity of the principal obligation carries with it that of the penal clause. (1155) 6. OTHER CLASSIFICATIONS OF OBLIGATIONS As to subject matter As to affirmativeness As to persons obliged D. Real – obligation to give Personal – obligation to do or not to do Positive – obligation to give or to do Negative – obligation not to do or not to give Unilateral – where only one of the parties is bound Bilateral – where both parties are bound NATURE AND EFFECT OF OBLIGATIONS 1. OBLIGATIONS TO GIVE a. To deliver the thing, which may be either actual or constructive. Actual Delivery – the actual change of hands of the thing. Constructive Delivery – where the physical transfer is implied which may be done by: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Traditio Simbolica – symbolic delivery. Traditio Longa Manu – delivery done by merely pointing to the object. Traditio Brevi Manu – where the person to whom delivery is due is already in possession of the thing. Traditio Constitutum Possessorium – where the possessor is the owner and retains possession but in another capacity. Executon of legal forms and solemnities b. The person obliged to give is required to take care of it with the proper diligence of a good father of a family (bonus pater familia), as a general rule. Except: when there is stipulation or the law requires another standard of care. c. The debtor is obliged to deliver the fruits of the thing from the time the obligation to deliver it arises. Note, however, that the creditor will not acquire real rights over the fruits until it is delivered to him. Example: D obliged himself to deliver to C a parcel of land with fruit-bearing trees on April 15, 2018. If the trees bore fruit on April 15, 2018, D is likewise obliged to deliver the same to C. C has a personal right to demand delivery of the fruits. But he does not acquire ownership over the fruits, or real rights over them, until they are delivered to him. Such that, if the fruits are sold by D to a buyer in good faith, X, the latter shall have a better right over them. C’s remedy is to ask for damages from D. d. The person obliged to give is also obliged to deliver all accessions and accessories, even though they may not have been mentioned. Accessories – those joined to or included with the principal for the latter’s better use, perfection or enjoyment. Example: keys to a house. Accessions – additions or improvements upon a thing which may include an alluvium and whatever is built, planted ro sown on a parcel of land. Example: building constructed on land. e. 2. Remedies available to the creditor in case of non-compliance: (1) Obligation to deliver a specific thing – demand specific performance (2) Obligation to deliver a generic thing – either demand specific performance or substitute performance OBLIGATIONS TO DO AND NOT TO DO Remedy available to the creditor in case of non-compliance (or when it was poorly done): the obligation can be performed by the creditor himself or by some other person at the expense of the debtor (or in obligations not to do have it undone) or ask for damages, or both. Note that specific performance is not a remedy in obligations to do since this would amount to involuntary servitude which is prohibited by our Constitution. E. SPECIFIC CIRCUMSTANCES AFFECTING OBLIGATIONS IN GENERAL Art. 1170. Those who in the performance of their obligations are guilty of fraud, negligence, or delay, and those who in any manner contravene the tenor thereof, are liable for damages. (1101) a. FRAUD Art. 1171. Responsibility arising from fraud is demandable in all obligations. Any waiver of an action for future fraud is void. (1102a) Art. 1338. There is fraud when, through insidious words or machinations of one of the contracting parties, the other is induced to enter into a contract which, without them, he would not have agreed to. (1269) Art. 1344. In order that fraud may make a contract voidable, it should be serious and should not have been employed by both contracting parties. Incidental fraud only obliges the person employing it to pay damages. (1270) Kinds of Fraud: 1. Dolo causante – or fraud in obtaining consent, is applicable only to contracts where consent is necessary and thus affects the validity of the contract, making it voidable. Under this kind of fraud, the party would not have entered into the contract were it not for the fraud; annulment is the remedy of the party who’s consent was obtained through fraud. Example: material misrepresentations made in an application for insurance. 2. Dolo incidente – or fraud in the performance of the obligation and applicable to obligations arising from any source. This kind, however, does not affect the validity of the contract and makes the party guilty of fraud liable for damages. Under this kind, a party would have entered the obligation with or without the fraud. Remedy is damages. Example: tax evasion, where the payment of taxes is lowered through illegal means such as underdeclaration of income or overclaiming of expenses. b. NEGLIGENCE Art. 1172. Responsibility arising from negligence in the performance of every kind of obligation is also demandable, but such liability may be regulated by the courts, according to the circumstances. (1103) Art. 1173. The fault or negligence of the obligor consists in the omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place. When negligence shows bad faith, the provisions of Articles 1171 and 2201, paragraph 2, shall apply. If the law or contract does not state the diligence which is to be observed in the performance, that which is expected of a good father of a family shall be required. (1104a) Negligence: consists in the omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place. Kinds of Negligence as to EXTENT: 1. 2. Simple Negligence – failure to comply with the diligence required; Gross Negligence – amounts to bad faith and may thus be the source of moral damages. Kinds of Negligence as to SOURCE: 1. Culpa Contractual – contractual negligence – or that which results in a breach of contract. Example: A passenger of a jeepney is hurt because of the driver’s negligence. Here, there is contract of carriage between the passenger and the owner of the jeepney, and the negligence was in relation to the absence or lack of the diligence required of the driver (representative of the owner) by virtue of such contract. As such, the passenger can sue the owner for breach of contract through negligence. 2. Culpa Aquiliana – civil negligence or quasi-delict Example: A passer-by is hit by the same jeepney from the above example. Here, there is no pre-existing contractual relationship. In this case, the passenger can sue both the driver and the owner for quasi-delict. However, the owner can raise the defense, and prove, that he exercised the required diligence in the selection and supervision of the driver. 3. Culpa Criminal – criminal negligence – or that which results in the commission of a crime or a delict. Example: In the same illustration, the passenger or the passer-by can sue the driver for culpa criminal, reckless imprudence resulting to physical injuries to be exact. Note that who can be sued criminally is the driver only. However, civil damages can be recovered from the owner who is considered subsidiarily liable if the driver is insolvent. Here, the defense of diligence in the selection and supervision of the drive is not available. Negligence on the part of the creditor: 1. If his negligence was the immediate and proximate cause of the injury, there is no recovery for damages. Example: a pedestrian, not looking where he was going and not knowing that the traffic light was red, bumped into a car driving below the speed limit. Here there is no negligence on the part of the car. In fact, if any damage is caused to the car, the pedestrian can be liable for such. 2. If his negligence was only contributory – he may still recover damages, BUT the courts can mitigate or reduce the same. Degree of care required: 1. As a rule a. That required by law: e.g., a common carrier is required to exercise extraordinary care; or b. That agreed upon by the parties. 2. In the absence of the two above, diligence of a good father of a family. c. DELAY Art. 1169. Those obliged to deliver or to do something incur in delay from the time the obligee judicially or extrajudicially demands from them the fulfillment of their obligation. However, the demand by the creditor shall not be necessary in order that delay may exist: (1) When the obligation or the law expressly so declare; or (2) When from the nature and the circumstances of the obligation it appears that the designation of the time when the thing is to be delivered or the service is to be rendered was a controlling motive for the establishment of the contract; or (3) When demand would be useless, as when the obligor has rendered it beyond his power to perform. In reciprocal obligations, neither party incurs in delay if the other does not comply or is not ready to comply in a proper manner with what is incumbent upon him. From the moment one of the parties fulfills his obligation, delay by the other begins. (1100a) Kinds of Delay: 1. 2. 3. Mora Solvendi – delay on the part of the debtor, which may either be: a. Mora solvendi ex re: in real obligations b. Mora solvendi ex persona: in personal obligations Mora Accipiendi – delay on the part of the creditor; Compensatio Morae – delay on the part of both parties. WHEN CONSIDERED IN DEFAULT: General Rule: upon demand, which may be judicial or extra-judicial. Exceptions: 1. 2. 3. 4. When When When When stipulated – a due date in itself is not enough, what should be stipulated is that there is no need for demand to consider the debtor in default the law so declares – e.g., delivery of a partner’s share in the partnership time was a controlling motive – e.g., a florist for a wedding demand would be useless – e.g., when the debtor already transferred the thing to another; or had it destroyed or hidden. d. ANY OTHER MANNER OF CONTRAVENTION Non-performance may fall under this category which may make the debtor liable for damages. In general, every debtor who fails in performance of his obligations is bound to indemnify for the losses and damages caused thereby. The phrase "any manner contravene the tenor" of the obligation includes any illicit act which impairs the strict and faithful fulfillment of the obligation or every kind or defective performance. (Arrieta vs. NARIC) Example: X leased a house to Y. It turns out that the true owner of the house is A and he wants to occupy the house. Here, X can be liable for breach of contract because he failed to maintain Y in peaceful possession of the leased premises. EXCUSE FOR NON-PERFORMANCE: 1. Fortuitous Event – Arts. 1174, 552,1165, 2147,2159 Art. 1174. Except in cases expressly specified by the law, or when it is otherwise declared by stipulation, or when the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk, no person shall be responsible for those events which could not be foreseen, or which, though foreseen, were inevitable. (1105a) Fortuitous events by definition are extraordinary events not foreseeable or avoidable. It is therefore, not enough that the event should not have been foreseen or anticipated, as is commonly believed but it must be one impossible to foresee or to avoid. Elements: To constitute a fortuitous event, the following elements must concur: a. b. c. d. The cause of the unforeseen and unexpected occurrence or of the failure of the debtor to comply with obligations must be independent of human will; It must be impossible to foresee the event that constitutes the caso fortuito or, if it can be foreseen, it must be impossible to avoid; The occurrence must be such as to render it impossible for the debtor to fulfill obligations in a normal manner; and, The obligor must be free from any participation in the aggravation of the injury or loss. General Rule: is that no personal shall be responsible for those events which could not be foresee, or which, though foreseen, were inevitable. Exceptions: 1. 2. 3. Declared by stipulation; When the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk: e.g., insurance contracts. Expressly specified by law. Provisions providing for liability even if the loss was due to fortuitous events: Art. 552. A possessor in good faith shall not be liable for the deterioration or loss of the thing possessed, except in cases in which it is proved that he has acted with fraudulent intent or negligence, after the judicial summons. A possessor in bad faith shall be liable for deterioration or loss in every case, even if caused by a fortuitous event. (457a) Art. 1165. When what is to be delivered is a determinate thing, the creditor, in addition to the right granted him by Article 1170, may compel the debtor to make the delivery. If the thing is indeterminate or generic, he may ask that the obligation be complied with at the expense of the debtor. If the obligor delays, or has promised to deliver the same thing to two or more persons who do not have the same interest, he shall be responsible for any fortuitous event until he has effected the delivery. (1096) Art. 2147. The officious manager shall be liable for any fortuitous event: (1) If he undertakes risky operations which the owner was not accustomed to embark upon; (2) If he has preferred his own interest to that of the owner; (3) If he fails to return the property or business after demand by the owner; (4) If he assumed the management in bad faith. (1891a) Art. 2159. Whoever in bad faith accepts an undue payment, shall pay legal interest if a sum of money is involved, or shall be liable for fruits received or which should have been received if the thing produces fruits. He shall furthermore be answerable for any loss or impairment of the thing from any cause, and for damages to the person who delivered the thing, until it is recovered. (1896a) Negligence, Delay or Fraud concurring with Fortuitous Event: if upon the happening of a fortuitous event or an act of God, there concurs a corresponding fraud, negligence, delay or violation or contravention in any manner of the tenor of the obligation as provided for in Article 1170 of the Civil Code, which results in loss or damage, the obligor cannot escape liability. The principle embodied in the act of God doctrine strictly requires that the act must be one occasioned exclusively by the violence of nature and human agencies are to be excluded from creating or entering into the cause of the mischief. When the effect, the cause of which is to be considered, is found to be in part the result of the participation of man, whether it be from active intervention or neglect, or failure to act, the whole occurrence is thereby humanized, as it was, and removed from the rules applicable to the acts of God. Thus, it has been held that when the negligence of a person concurs with an act of God in producing a loss, such person is not exempt from liability by showing that the immediate cause of the damage was the act of God. To be exempt from liability for loss because of an act of God, he must be free from any previous negligence or misconduct by which the loss or damage may have been occasioned. (NPC vs. CA) F. REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF OBLIGATIONS Obligations to give: Art. 1165. When what is to be delivered is a determinate thing, the creditor, in addition to the right granted him by Article 1170, may compel the debtor to make the delivery. If the thing is indeterminate or generic, he may ask that the obligation be complied with at the expense of the debtor. If the obligor delays, or has promised to deliver the same thing to two or more persons who do not have the same interest, he shall be responsible for any fortuitous event until he has effected the delivery. (1096) 1. 2. Determinate thing – specific performance only if it is legally and physically possible. Substitute performance is not possible. Generic thing – substitute performance. The creditor can have another person to have such kind of thing be delivered at the cost of the debtor plus damages. Obligations to do: the remedy of the creditor: Substitute performance – have somebody else perform the obligation at the debtor’s cost, including the costs of having to undo that which was poorly done. Art. 1167. If a person obliged to do something fails to do it, the same shall be executed at his cost. This same rule shall be observed if he does it in contravention of the tenor of the obligation. Furthermore, it may be decreed that what has been poorly done be undone. (1098) Specific Performance: is not applicable since this would be violative of the debtor’s constitutional right against involuntary servitude. Obligations not to do: and the obligor does it, the creditor may have it undone at the expense of the debtor. Art. 1168. When the obligation consists in not doing, and the obligor does what has been forbidden him, it shall also be undone at his expense. (1099a) RESCISSION AS A REMEDY: TWO KINDS: 1. Rescission under Art. 1191, which should’ve been properly termed as “resolution” Art. 1191. The power to rescind obligations is implied in reciprocal ones, in case one of the obligors should not comply with what is incumbent upon him. The injured party may choose between the fulfillment and the rescission of the obligation, with the payment of damages in either case. He may also seek rescission, even after he has chosen fulfillment, if the latter should become impossible. The court shall decree the rescission claimed, unless there be just cause authorizing the fixing of a period. This is understood to be without prejudice to the rights of third persons who have acquired the thing, in accordance with Articles 1385 and 1388 and the Mortgage Law. (1124) 2. Rescission under Art. 1301/1303 Differences: RESOLUTION (Art. 1911) Principal remedy – may be availed of even if the party has other remedies available. Cause of action is “substantial or fundamental breach” RESCISSION (Art. 1301) Subsidiary remedy – can only be invoked if there is no other remedy (Art. 1303) Breach is not required. May be invoked even if both parties already complied with their obligation. Cause of action is lesion or economic injury to a party. the beginning and restore the parties to their relative positions as if no contract has been made. Kinds of Damages (MENTAL): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Moral – for mental and physical anguish Exemplary – corrective or to set an example Nominal – to vindicate a right when no other kind of damages may be recovered Temperate – when the exact amount of damages can not be determined Actual – actual losses incurred. This is the only type of damage that would require proof. Liquidated – predetermined beforehand. G. MODES OF EXTINGUISHMENT OF OBLIGATIONS – Art. 1231 Art. 1231. Obligations are extinguished: (1) By payment or performance: (2) By the loss of the thing due: (3) By the condonation or remission of the debt; (4) By the confusion or merger of the rights of creditor and debtor; (5) By compensation; (6) By novation. Other causes of extinguishment of obligations: a. Annulment b. Rescission c. Fulfillment of a resolutory condition d. Prescription These other causes are governed elsewhere in the Civil Code. PAYMENT OR PERFORMANCE A debt is not understood to have been paid unless the thing or service in which the obligation consists has been completely delivered or rendered, as the case may be. How made: • If debt is a monetary obligation, by delivery of the money. • If the debt is delivery of a thing or things, by delivery of the thing or things. • If the debt is doing of a personal undertaking, by the performance of said personal undertaking. • If the debt is not doing something, by refraining from doing the action. a. Provisions as to the payor Art. 1236. The creditor is not bound to accept payment or performance by a third person who has no interest in the fulfillment of the obligation, unless there is a stipulation to the contrary. Whoever pays for another may demand from the debtor what he has paid, except that if he paid without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, he can recover only insofar as the payment has been beneficial to the debtor. (1158a) Art. 1237. Whoever pays on behalf of the debtor without the knowledge or against the will of the latter, cannot compel the creditor to subrogate him in his rights, such as those arising from a mortgage, guaranty, or penalty. (1159a) Payment made by a third person: a. Who has an interest in the fulfilment of the obligation or when the debtor consents. Effects: 1. The creditor can be compelled to receive payment 2. The third party payor may demand reimbursement for the full amount 3. Results in subrogation: As such, the 3rd party payor may exercise rights belonging to the creditor, such as going against the guarantor or foreclosure of mortgage. Person who has interest in the fulfillment of the obligation: include those subsidiarily liable such as guarantors and mortgagors, and co-debtors (including joint co-debtors). Example: A is indebted to B for P1,000,000 secured by a mortgage on X’s house and a guaranty executed by Y. X offered to pay the P1,000,000 which was accepted by B. In this case, • X is entitled to reimbursement for the full amount even if A already made partial payments. • X is subrogated to B’s rights. As such, he can go against Y in case A is unable to pay. • If B refused, he can be compelled by X to accept the payment. b. One who has no interest in the fulfilment of the obligation or when the debtor had no knowledge of or did not consent (against his will). Effects: 1. The creditor cannot be compelled to receive payment. 2. If payment was made, 3rd party payor can only demand reimbursement upto the extent that has been beneficial to the debtor. 3. No subrogation. As such, the third party payor cannot go against guarantors or foreclose the mortgage. Example: A is indebted to B for P1,000,000 secured by a mortgage on X’s house. Z offered to pay the P1,000,000 which was accepted by B against the will of A. In this case, • Z is entitled to reimbursement only to the extent beneficial to the debtor. Accordingly, if A already made partial payments of say P200,000, Z is only entitled only to reimbursement upto P800,000. • Z is not subrogated to B’s rights. As such, he cannot foreclose on the mortgage if A failed to pay. • If B refused, he can not be compelled by Z to accept the payment. In both instances, the payment shall extinguish the obligation. Subrogation: when the 3rd party payor steps in the shoes of the creditor. There is legal subrogation when: Art. 1302. It is presumed that there is legal subrogation: (1) When a creditor pays another creditor who is preferred, even without the debtor's knowledge; (2) When a third person, not interested in the obligation, pays with the express or tacit approval of the debtor; (3) When, even without the knowledge of the debtor, a person interested in the fulfillment of the obligation pays, without prejudice to the effects of confusion as to the latter's share. (1210a) When creditor may be bound to accept payment from a third person: 1. 2. When stipulated; When the 3rd party payor has an interest in the fulfilment of the obligation 3. When the debtor gives his consent. Art. 1238. Payment made by a third person who does not intend to be reimbursed by the debtor is deemed to be a donation, which requires the debtor's consent. But the payment is in any case valid as to the creditor who has accepted it. (n) Debtor’s consent: is necessary under this article since there can be no valid donation without acceptance by the donee since no one should be compelled to accept the generosity of another. If the debtor did not consent, there would be no valid donation, and the third party-payor can seek reimbursement from the debtor. Obligation is extinguished: even if the debtor did not accept the donation since the payment is in any case valid as to the creditor. Art. 1239. In obligations to give, payment made by one who does not have the free disposal of the thing due and capacity to alienate it shall not be valid. Capacity and Free Disposal: the payor should have capacity to alienate and the free disposal of the thing due for payment to be effective. Such that minors (who don’t have capacity) and those suffering the penalty of civil interdiction (no free disposal) cannot make a valid payment. b. Provisions as to the payee Art. 1240. Payment shall be made to the person in whose favor the obligation has been constituted, or his successor in interest, or any person authorized to receive it. (1162a) Payment may be made to: 1. 2. 3. Person in whose favour the obligation has been constituted – not necessarily a party to the constitution of the obligation. His successor in interest – who may not be creditors at the time of constitution, but may be creditors at the time of fulfilment. Any person authorized to receive it – agents are creditors because they have the right to collect, but not in their own right. (This is relevant as to Compensation as a mode of extinguishing obligation) Payment to a wrong party: Art. 1241. Payment to a person who is incapacitated to administer his property shall be valid if he has kept the thing delivered, or insofar as the payment has been beneficial to him. Payment made to a third person shall also be valid insofar as it has redounded to the benefit of the creditor. Such benefit to the creditor need not be proved in the following cases: (1) If after the payment, the third person acquires the creditor's rights; (2) If the creditor ratifies the payment to the third person; (3) If by the creditor's conduct, the debtor has been led to believe that the third person had authority to receive the payment. (1163a) Payment to an incapacitated person: is valid only if the incapacitated person kept the thing delivered or insofar as it was beneficial to him. Example: X is indebted to A for P100,000. A became insane when X paid the P100,000. 1. If after a while the money was not used by A, the payment is considered valid since A kept the money. 2. If A was fraudulently induced by Z to buy a ring for P100,000, where the ring is actually worth P20,000 only. There is valid payment upto the amount of P20,000 since this is the amount for which A benefited. Payment to anyone not authorized as provided under Art. 1240 is considered a void payment. As such, the debtor may be compelled to pay again, his remedy being to run against the person he made payment to. Except in the following circumstances: 1. It redounded to the benefit of the creditor; 2. Such benefit need not be proven if: a. after the payment, the third person acquires the creditor's rights; b. the creditor ratifies the payment to the third person; c. by the creditor's conduct, the debtor has been led to believe that the third person had authority to receive the payment. 3. Payment made in good faith to any person in possession of the credit. (Art. 1242) c. Thing to be paid or delivered Art. 1232. Payment means not only the delivery of money but also the performance, in any other manner, of an obligation. (n) Art. 1244. The debtor of a thing cannot compel the creditor to receive a different one, although the latter may be of the same value as, or more valuable than that which is due. In obligations to do or not to do, an act or forbearance cannot be substituted by another act or forbearance against the obligee's will. (1166a) Art. 1246. When the obligation consists in the delivery of an indeterminate or generic thing, whose quality and circumstances have not been stated, the creditor cannot demand a thing of superior quality. Neither can the debtor deliver a thing of inferior quality. The purpose of the obligation and other circumstances shall be taken into consideration. (1167a) Art. 1249. The payment of debts in money shall be made in the currency stipulated, and if it is not possible to deliver such currency, then in the currency which is legal tender in the Philippines. The delivery of promissory notes payable to order, or bills of exchange or other mercantile documents shall produce the effect of payment only when they have been cashed, or when through the fault of the creditor they have been impaired. In the meantime, the action derived from the original obligation shall be held in the abeyance. (1170) Legal Tender Power: refers to payment which the creditor can be compelled to accept. Under the New Central Bank Act, coins and currencies issued by the BSP have legal tender power. For currency notes, there is no limit as to the amount it can be used as legala tender. However, for coins, the following are the limits: 1. P1, P5 and P10 coins shall be legal tender in amounts not exceeding P1,000; 2. Coins below P1 – legal tender not exceeding P100. Extinguishment: Payment made through negotiable instruments, such as checks, do not produce the effect of payment, or extinguish the obligation, until: 1. 2. At the time the check or other mercantile documents have been encashed; Its value becomes impaired. Art. 1250. In case an extraordinary inflation or deflation of the currency stipulated should supervene, the value of the currency at the time of the establishment of the obligation shall be the basis of payment, unless there is an agreement to the contrary. (n) Applicable only to contracts: since the provision deals with “currency stipulated” d. Place, date, time and manner of payment 1. 2. Payment shall be made in the place designated in the obligation. If there was no stipulation and the obligation consists in the delivery of a determinate thing, the payment shall be made wherever the thing might be at the moment the obligation was constituted. In any other case the place of payment shall be the domicile of the debtor. If the debtor changes his domicile in bad faith or after he has incurred in delay, the additional expenses shall be borne by him. 3. 4. SPECIAL FORMS OF PAYMENT Dation in Payment Art. 1245. Dation in payment, whereby property is alienated to the creditor in satisfaction of a debt in money, shall be governed by the law of sales. Dation in payment is the delivery or transmission of ownership of a thing by the debtor to the creditor as an accepted equivalent of the performance of the obligation. It may consists not only of a thing but also of rights, i.e., usufruct or credit. Governed by the law on sales: The undertaking really partakes in one sense of the nature of sale, that is, the creditor is really buying the thing or property of the debtor, payment for which is to be charged against the debtor's debt. As such, the essential elements of a contract of sale, namely, consent, object certain, and cause or consideration must be present. (Filinvest Credit Corporation vs. Philippine Acetylene Co., Inc.) Nature: there has to be delivery of the thing and prior acceptance and a consequent transfer of ownership to consider it a dation in payment. A mere promise to deliver a thing in lieu of the originally constituted subject amounts to a novation. Extent of extinguishment: General rule: to the extent of the value of the thing delivered as agreed upon or as may be proved. Exception: if the parties consider the thing as equivalent to the obligation through an express or implied agreement or by silence. Application of Payments Art. 1252. He who has various debts of the same kind in favor of one and the same creditor, may declare at the time of making the payment, to which of them the same must be applied. Unless the parties so stipulate, or when the application of payment is made by the party for whose benefit the term has been constituted, application shall not be made as to debts which are not yet due. If the debtor accepts from the creditor a receipt in which an application of the payment is made, the former cannot complain of the same, unless there is a cause for invalidating the contract. (1172a) Application of Payment: is the designation of the debt which is being paid by a debtor who has several obligations of the same kind in favor of the creditor to whom payment is made. Requisites: 1. 2. 3. 4. There is only one debtor; There are several debts; The debts are of the same kind; There is only one and the same creditor. Due and demandable debts: as a general rule, all the debts must be due and demandable. EXCEPTION: when there is mutual agreement or when the consent of the party for whose benefit the term was constituted was obtained. Right to apply payment: generally, the debtor has the right to apply the payment at the time of making the payment, subject to the following LIMITATIONS: 1. Creditor cannot be compelled to accept partial payment. (Art. 1248); Art. 1248. Unless there is an express stipulation to that effect, the creditor cannot be compelled partially to receive the prestations in which the obligation consists. Neither may the debtor be required to make partial payments. However, when the debt is in part liquidated and in part unliquidated, the creditor may demand and the debtor may effect the payment of the former without waiting for the liquidation of the latter. (1169a) 2. Debtor cannot apply payment to principal if interest has not been paid. Art. 1253. If the debt produces interest, payment of the principal shall not be deemed to have been made until the interests have been covered. (1173) 3. 4. The debt must be liquidated, except when the parties agree otherwise; Cannot be made when the period has not arrived and such period was constituted in favour of the creditor, except with the consent of the creditor (Art. 5. When there is agreement as to which debt must be paid first. 1252); If the debtor did not designate, to which debt shall payment apply? That which was chosen by the creditor as reflected in the receipt which is accepted by the debtor without protest. (Art. 1252, 2nd par.) Art. 1254. When the payment cannot be applied in accordance with the preceding rules, or if application cannot be inferred from other circumstances, the debt which is most onerous to the debtor, among those due, shall be deemed to have been satisfied. If the debts due are of the same nature and burden, the payment shall be applied to all of them proportionately. (1174a) If debtor and creditor did not designate: 1. 2. If the debts are of different nature and burden – to that debt which is most onerous to the debtor; IF the debts are of the same nature and burden – applied proportionately. Debts which are considered more onerous: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Principal in obligation and surety in another debt where he is the PRINCIPAL Sole debtor in one obligation and solidary debtor in another debt where he is the SOLE DEBTOR As among solidary debtors the part of the debt corresponding to each is more burdensome than as to every debtor When there are various debts (all without interest) OLDEST When there are various debts (some with interest) that with HIGHEST INTEREST RATE When there is an unsecured debt with interest and a secured debt without interest that which has interest When there is an encumbrance that which is SECURED When there is a bond where the principal and surety are solidarily bound BUT the a smaller portion pertains to the surety as to the principal, the UNSECURED PORTION of the debt is more onerous 9. With respect to indemnity for damages those with a penal clause over those governed by the general rules on damages 10. Liquidated debts over unliquidated ones 11. Those where the debtor is in default over those where he is not Payment by Cession or Assignment Art. 1255. The debtor may cede or assign his property to his creditors in payment of his debts. This cession, unless there is stipulation to the contrary, shall only release the debtor from responsibility for the net proceeds of the thing assigned. The agreements which, on the effect of the cession, are made between the debtor and his creditors shall be governed by special laws. (1175a) Two Kinds: 1. Voluntary – Art. 1255; 2. Judicial – under the Insolvency Law. Remedy of the debtor if the creditors do not accept his voluntary cession. Advantages of judicial cession is that the court discharges the debtor of his debts and the obligations are extinguished. Properties exempt from Execution: are generally not covered by cession. Except if the debtor waives such exemption. Dation in payment vs. Assignment: Dation in payment Cession or Assignment both are substitute of performance of an obligation Art 1245 Art 1255 Ownership of the thing is transferred to the creditor No such transfer Obligation may be totally extinguished if agreed upon by the Obligation is extinguished only insofar as the net proceeds parties or by their silence, consider the thing equivalent to the (except: otherwise stipulated) obligation. does not involve plurality of creditors involves plurality of creditors Involves a specific thing Involves all the properties of the debtor unless exempt from execution. may be made even by a solvent debtor; merely involves a supposes financial difficulty on the part of the debtor change of the object of the obligation by agreement of the parties and at the same time fulfilling the same voluntarily How proceeds distributed to the creditors: 1. 2. Stipulation; Preference of credit. Tender of Payment and Consignation Tender of Payment is the manifestation made by the debtor to the creditor of his desire to comply with his obligation, with the offer of immediate performance. It is a PREPARATORY ACT to consignation and in itself DOES NOT extinguish the obligation. Consignation is the deposit of the object of the obligation in a competent court in accordance with rules prescribed by law, AFTER the tender of payment has been refused or because of circumstances which render direct payment to the creditor impossible. It extinguishes the obligation. Applies only to extinguish of obligation not to exercise a right: such that in a situation where a party would exercise his right of repurchase and the buyer refused to accept. The right to redeem is a RIGHT, not an obligation, therefore, there is no consignation required. (Immaculata vs. Navarro) Requisites: 1. 2. There is a debt due; There is legal cause to consign in any of the following grounds: Art. 1256. If the creditor to whom tender of payment has been made refuses without just cause to accept it, the debtor shall be released from responsibility by the consignation of the thing or sum due. Consignation alone shall produce the same effect in the following cases: (1) When the creditor is absent or unknown, or does not appear at the place of payment; (2) When he is incapacitated to receive the payment at the time it is due; (3) When, without just cause, he refuses to give a receipt; (4) When two or more persons claim the same right to collect; (5) When the title of the obligation has been lost. (1176a) As a rule, tender of payment is not required prior to consignation. There is only one instance where tender of payment is required, i.e., when the creditor refuses to accept without just cause. 3. There is previous notice to consign to the persons having interest in the fulfilment of the obligation; Art. 1257. In order that the consignation of the thing due may release the obligor, it must first be announced to the persons interested in the fulfillment of the obligation. The consignation shall be ineffectual if it is not made strictly in consonance with the provisions which regulate payment. (1177) 4. The amount or thing due is deposited in court. Art. 1258. Consignation shall be made by depositing the things due at the disposal of judicial authority, before whom the tender of payment shall be proved, in a proper case, and the announcement of the consignation in other cases. The consignation having been made, the interested parties shall also be notified thereof. (1178) Art. 1259. The expenses of consignation, when properly made, shall be charged against the creditor. (1178) Withdrawal of the Thing Deposited: Art. 1260. Once the consignation has been duly made, the debtor may ask the judge to order the cancellation of the obligation. Before the creditor has accepted the consignation, or before a judicial declaration that the consignation has been properly made, the debtor may withdraw the thing or the sum deposited, allowing the obligation to remain in force. (1180) Art. 1261. If, the consignation having been made, the creditor should authorize the debtor to withdraw the same, he shall lose every preference which he may have over the thing. The co-debtors, guarantors and sureties shall be released. (1181a) Withdrawal as a matter of right: debtor withdraws before acceptance by the creditor or before judicial declaration of propriety of consignation. In this case, no extinguishment yet of the obligation. As such, no revival since the obligation has not been extinguished to begin with. Withdrawal after acceptance or declaration: obligation is revived. As such, creditor can no longer run after the guarantor, unless the latter consented. This is because the obligation has been extinguished. The revival did not revive the guaranty. LOSS OF THE THING DUE OR IMPOSSIBILITY OF PERFORMANCE Loss: means when the thing goes out of commerce, perishes or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or that it cannot be recovered. Art. 1262. An obligation which consists in the delivery of a determinate thing shall be extinguished if it should be lost or destroyed without the fault of the debtor, and before he has incurred in delay. When by law or stipulation, the obligor is liable even for fortuitous events, the loss of the thing does not extinguish the obligation, and he shall be responsible for damages. The same rule applies when the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk. (1182a) Fortuitous Event: generally, the debtor is not liable for damages if the thing is lost due to fortuitous event, EXCEPTIONS: 1. 2. 3. When the law so provides; When stipulation so provides; When the nature of the obligation requires the assumption of risk. For fortuitous event to be invoked, there must be no negligence on the part of the party invoking. Malfunction of the break system – is not a fortuitous event since this could’ve been prevented by a regular maintenance of the vehicle. Robbery and Theft: are not considered Fortuitous Event for a pawnshop business or a bank. (Sicam vs. Jorge) Reciprocal Obligations: the extinguishment of one party’s obligation due to loss due to a fortuitous event, likewise extinguishes the other party’s obligation. Art. 1263. In an obligation to deliver a generic thing, the loss or destruction of anything of the same kind does not extinguish the obligation. (n) Genus nunquam perit: Genus does not perish. EXCEPTIONS: 1. 2. 3. When the thing goes out of commerce; By legal impossibility; Limited Generic: In such cases where the generic thing belongs to a particular group of thing and the loss pertains to the whole group and NOT ONLY to the thing itself, then the obligation is extinguished. E.g., A promise to deliver one of his horses and ALL the horses of the A died, the obligation is extinguished. Partial Loss: Art. 1264. The courts shall determine whether, under the circumstances, the partial loss of the object of the obligation is so important as to extinguish the obligation. (n) Partial loss may be determined by the court as so important to extinguish the obligation. In doing so, intent of the parties must necessarily be considered. E.g., A promised to deliver a cellphone with its casing. The cellphone was stolen but A managed to save the casing. Would A still be liable to deliver the casing? Yes, if the primary consideration of the creditor was to obtain the casing. The test is whether the parties would not have entered into the obligation without the thing that have been lost, then the obligation is extinguished. Art. 1265. Whenever the thing is lost in the possession of the debtor, it shall be presumed that the loss was due to his fault, unless there is proof to the contrary, and without prejudice to the provisions of article 1165. This presumption does not apply in case of earthquake, flood, storm, or other natural calamity. (1183a) Burden of proof: is generally with the creditor claiming that the loss was due to the fault of the debtor. However, if the thing is lost while in the possession of the debtor, a presumption arises that it was due to his fault, thus, the burden of proof shifts to him. However still, if the thing was lost on the occasion of a calamity, then no such presumption arises, the burden of proof is still with the creditor. Art. 1266. The debtor in obligations to do shall also be released when the prestation becomes legally or physically impossible without the fault of the obligor. (1184a) Loss of the thing may likewise cover impossibility of performance, e.g., a debtor is obliged to paint a building and the building was destroyed (physical impossibility) or a law took effect making the obligation illegal (legal impossibility). When: In impossibility, the law should take effect, or the impossibility happened DURING the existence of the obligation so as to extinguish it. If the law took effect or the impossibility arose BEFORE the existence of the obligation, the obligation is void. Types of Impossibility: 1. 2. 3. 4. As As a. b. As As to nature: Physical (by reason of its nature); and Legal (through some subsequent law); to whom impossibility refers: Objective – impossibility of the act or service itself without considering the person of the debtor; Subjective - impossibility refers to the fact that the act or service can no longer be done by the debtor but may still be performed by another person to extent: Partial or Total; to period of impossibility: Permanent or Temporary. Difficulty of prestation Art. 1267. When the service has become so difficult as to be manifestly beyond the contemplation of the parties, the obligor may also be released therefrom, in whole or in part. (n) Court action: when the performance of the obligation is difficult, it does not, on its own, warrant extinguishment of the obligation. However, when it has become so difficult beyond the contemplation of the parties, the debtor may go to court to release him from the obligation but not to modify the terms of the contract. Requisites for applicability: 1. 2. 3. 4. Event or change in the circumstances that could not have been foreseen at the time of the execution of the contract; Such event or change makes the performance extremely difficult but not impossible; Such event or change is not due to the act of any of the parties; The contract concerns a future prestation. Art. 1269. The obligation having been extinguished by the loss of the thing, the creditor shall have all the rights of action which the debtor may have against third persons by reason of the loss. (1186) CONDONATION OR REMISSION OF THE DEBT Art. 1270. Condonation or remission is essentially gratuitous, and requires the acceptance by the obligor. It may be made expressly or impliedly. One and the other kind shall be subject to the rules which govern inofficious donations. Express condonation shall, furthermore, comply with the forms of donation. (1187) Condonation/Remission is an act of liberality, by virtue of which, without receiving any equivalent, the creditor renounces the enforcement of an obligation, which is extinguished in its entirety or in that part or aspect of the same to which the remission refers. Gratuitous: If not gratuitous, it will be considered: 1. 2. 3. Dation in payment – when the creditor receives a thing different from that stipulated; Novation – when the subject or principal conditions of the obligation should be changed; Compromise – when the matter renounced is in litigation or dispute and in exchange of some concession which the creditor receives. Kinds of Condonation: 1. As to form: a. Express – when made formally; should be in accordance with the forms of ordinary donations. i. Acceptance is necessary for this to become effective; Article 745. The donee must accept the donation personally, or through an authorized person with a special power for the purpose, or with a general and sufficient power; otherwise, the donation shall be void. (630) Article 746. Acceptance must be made during the lifetime of the donor and of the donee. (n) ii. Movable property must comply with the form prescribed under Art. 748: Art. 748. The donation of a movable may be made orally or in writing. An oral donation requires the simultaneous delivery of the thing or of the document representing the right donated. If the value of the personal property donated exceeds five thousand pesos, the donation and the acceptance shall be made in writing, otherwise, the donation shall be void. (632a) iii. Immovable property must comply with the form prescribed under Art. 749: Art. 749. In order that the donation of an immovable may be valid, it must be made in a public document, specifying therein the property donated and the value of the charges which the donee must satisfy. The acceptance may be made in the same deed of donation or in a separate public document, but it shall not take effect unless it is done during the lifetime of the donor. If the acceptance is made in a separate instrument, the donor shall be notified thereof in an authentic form, and this step shall be noted in both instruments. (633) b. Implied – when it can be inferred from the acts of the parties. E.g., delivery of the promissory note to the debtor. 2. As to extent a. Total – when the whole obligation is extinguished. b. Partial – which may be as to the amount; as to the accessory obligation; or as to a certain amount of debt (in case of solidarity). 3. As to manner of remission a. Inter vivos – during the lifetime of the creditor. b. Mortis causa – will take effect upon death which must be in done through a will. Art. 1271. The delivery of a private document evidencing a credit, made voluntarily by the creditor to the debtor, implies the renunciation of the action which the former had against the latter. If in order to nullify this waiver it should be claimed to be inofficious, the debtor and his heirs may uphold it by proving that the delivery of the document was made in virtue of payment of the debt. (1188) Implied/Tacit Remission may be had from: 1. 2. Delivery of a private document evidencing a credit, voluntarily made by the creditor to the debtor (Art. 1271); Voluntary destruction or cancellation of the evidence of credit by the creditor with intent to renounce his right Covers “private instrument” only: because if what was delivered is a public document, the fact that there remains a copy in the archive of certain offices of such document means that there can be no renunciation if such were the case. Art. 1272. Whenever the private document in which the debt appears is found in the possession of the debtor, it shall be presumed that the creditor delivered it voluntarily, unless the contrary is proved. (1189) Art. 1273. The renunciation of the principal debt shall extinguish the accessory obligations; but the waiver of the latter shall leave the former in force. (1190) Art. 1274. It is presumed that the accessory obligation of pledge has been remitted when the thing pledged, after its delivery to the creditor, is found in the possession of the debtor, or of a third person who owns the thing. (1191a) CONFUSION OR MERGER OF RIGHTS Art. 1275. The obligation is extinguished from the time the characters of creditor and debtor are merged in the same person. (1192a) Merger/Confusion: the meeting in one person of the qualities of the creditor and debtor with respect to the same obligation. Requisites: a. b. Must take place between the credit and the principal debtor; Must involve the very same obligation; c. Must be total. Examples: a. b. PNB is indebted to Allied. PNB and Allied Bank entered into a merger agreement. In this case, the indebtedness of PNB is extinguished due to the merger. H is indebted to his father T. When T dies and H is his only heir, the obligation becomes extinguished since H will inherit the credit. The characters of the creditor and debtor in the said obligation are merged in his person. Art. 1276. Merger which takes place in the person of the principal debtor or creditor benefits the guarantors. Confusion which takes place in the person of any of the latter does not extinguish the obligation. (1193) Guarantors: this article is for the benefit of the guarantor. But the merger of the creditor and guarantor does not affect the principal application. COMPENSATION Art. 1278. Compensation shall take place when two persons, in their own right, are creditors and debtors of each other. (1195) Compensation: a mode of extinguishment to the concurrent amount, the obligations of those persons who in their own right, are reciprocally creditors and debtors of each other. Compensation vs. Payment, Merger and Counterclaim capacity of party to dispose of thing extent of extinguishment of obligation number of obligations parties need to allege Compensation not necessary because it takes effect by operation of law may be partial Payment indispensable Compensation always 2 2 persons are mutually the creditor and debtor of each other Merger only one the creditor and the debtor become one and the same Compensation need not be alleged and proven because it takes effect by operation of law Counterclaim must be alleged and proven must be complete Kinds of Compensation: 1. As to effects/extent: a. Total – when the two obligations are of the same amount; Art. 1281. Compensation may be total or partial. When the two debts are of the same amount, there is a total compensation. (n) b. 2. Partial – when the amounts are not equal. This is total as to the debt with lower amount. As to origin/cause: a. Legal – takes effect by operation of law because all the requisites are present; b. Facultative – can be claimed by one of the parties who, however, has the right to object to it c. Example: when one of the obligations has a period for the benefit of one party alone and who renounces that period so as to make the obligation due Conventional – when the parties agree to compensate their mutual obligations even if some of the requisite are lacking. Art. 1282. The parties may agree upon the compensation of debts which are not yet due. (n) d. Judicial – decreed by the court in a case where there is a counterclaim. Art. 1283. If one of the parties to a suit over an obligation has a claim for damages against the other, the former may set it off by proving his right to said damages and the amount thereof. (n) Requisites: Art. 1279. In order that compensation may be proper, it is necessary: (1) That each one of the obligors be bound principally, and that he be at the same time a principal creditor of the other; (2) That both debts consist in a sum of money, or if the things due are consumable, they be of the same kind, and also of the same quality if the latter has been stated; (3) That the two debts be due; (4) That they be liquidated and demandable; (5) That over neither of them there be any retention or controversy, commenced by third persons and communicated in due time to the debtor. (1196) Requisites: 1. Parties must be mutual principal debtors and creditors in their own right: Credit Line – the existence of a credit line does not necessarily create a debtor-creditor relationship if the debtor did not avail of said credit line. (PNB vs. Vda de Ong Acero) They must be creditors in their own right – If one of the creditors is not a creditor in his own right, that is, his right to collect is because of a contract of agency, compensation cannot take place between the debt of such agent to a party who is indebted to the principal. (Sycip vs. CA) 2. Both debts must be due– does not necessitate that both debts are due AT THE SAME TIME; one debt may have been due earlier. The requirement is that at the time of the compensation, both debts are already due. 3. Both debts must be liquidated and demandable - Liquidated debts are those whose exact amount has already been determined. (Asia Trust Development Bank vs. Tuble, GR No. 183987, July 25, 2012) Compensation cannot take place where one's claim against the other is still the subject of court litigation. It is a requirement, for compensation to take place, that the amount involved be certain and liquidated. (Solinap vs. del Rosario) Proof of the liquidation of a claim, in order that there be compensation of debts, is proper if such claim is disputed. But, if the claim is undisputed, as in the case at bar, the statement is sufficient and no other proof may be required. (Republic vs. de los Angeles) 4. Debts must pertain to sums of money or if consumables, they must be of the same kind and quality No compensation in reciprocal obligations: a. b. They must have arisen from the same cause, as such they can never involve both sums of money or the same consumables of the same kind and quality; Otherwise, no one can be compelled to perform an obligation Attorney’s Fees may be the subject of legal compensation: It is the litigant, not his counsel, who is the judgment creditor and who may enforce the judgment by execution. Such credit, therefore, may properly be the subject of legal compensation. (Gan Tion vs. CA) Thus, if the trial court granted the request of the attorney to make the attorney’s fees directly payable to him, where such was already offsetted against the debt of the winning party to the debtor, then the grant is a void alteration of judgment. (Mindanao Portland Cement Corporation vs. CA) 5. The claim must be clearly demandable, i.e., no controversy as to the claim. If the claim of one party is still contested or disputed, this requirement is not yet met. As such, this circumstance prevents legal compensation from taking place. (International Corporate Bank Inc vs. IAC) Art. 1280. Notwithstanding the provisions of the preceding article, the guarantor may set up compensation as regards what the creditor may owe the principal debtor. (1197) Art. 1284. When one or both debts are rescissible or voidable, they may be compensated against each other before they are judicially rescinded or avoided. (n) Art. 1285. The debtor who has consented to the assignment of rights made by a creditor in favor of a third person, cannot set up against the assignee the compensation which would pertain to him against the assignor, unless the assignor was notified by the debtor at the time he gave his consent, that he reserved his right to the compensation. If the creditor communicated the cession to him but the debtor did not consent thereto, the latter may set up the compensation of debts previous to the cession, but not of subsequent ones. If the assignment is made without the knowledge of the debtor, he may set up the compensation of all credits prior to the same and also later ones until he had knowledge of the assignment. (1198a) Debtor may still invoke compensation even after assignment, if: 1. 2. Had no knowledge of or did not consent to the assignment; or If with knowledge or consent, but reserved his right to the compensation. Art. 1286. Compensation takes place by operation of law, even though the debts may be payable at different places, but there shall be an indemnity for expenses of exchange or transportation to the place of payment. (1199a) Art. 1287. Compensation shall not be proper when one of the debts arises from a depositum or from the obligations of a depositary or of a bailee in commodatum. Neither can compensation be set up against a creditor who has a claim for support due by gratuitous title, without prejudice to the provisions of paragraph 2 of Article 301. (1200a) Art. 1288. Neither shall there be compensation if one of the debts consists in civil liability arising from a penal offense. (n) When compensation may not be proper: 1. 2. 3. 4. Depositum – as to the depositary; Bail – as to the bailee; Support – as to the one giving support, EXCEPT: support in arrears and those contractual in nature; Civil liability arising from a penal offense. Art. 1289. If a person should have against him several debts which are susceptible of compensation, the rules on the application of payments shall apply to the order of the compensation. (1201) Art. 1290. When all the requisites mentioned in Article 1279 are present, compensation takes effect by operation of law, and extinguishes both debts to the concurrent amount, even though the creditors and debtors are not aware of the compensation. (1202a) NOVATION Dual Function: extinguishes the obligation and creates a new one. Requisites: 1. Previous valid obligation Art. 1298. The novation is void if the original obligation was void, except when annulment may be claimed only by the debtor or when ratification validates acts which are voidable. (1208a) 2. 3. 4. Agreement of all parties to a new contract Extinguishment of old obligation Validity of the new obligation Art. 1297. If the new obligation is void, the original one shall subsist, unless the parties intended that the former relation should be extinguished in any event. (n) Death of one of the creditor: the new creditor is(are) the heir(s), no novation. Mere change in the person of the creditor does not cause novation. Art. 1291. Obligations may be modified by: (1) Changing their object or principal conditions; (2) Substituting the person of the debtor; (3) Subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor. (1203) Kinds of Novation: 1. 2. 3. As to nature: a. Subjective/Personal b. Objective/Real c. Mixed As to form: a. Express; b. Implied As to extent: a. Total; b. Partial. Subjective Novation: changing the subject: 1. Active – if a third person is subrogated to the rights of the creditor; How? a. By agreement or express Whose consent necessary: Art. 1300. Subrogation of a third person in the rights of the creditor is either legal or conventional. The former is not presumed, except in cases expressly mentioned in this Code; the latter must be clearly established in order that it may take effect. (1209a) Art. 1301. Conventional subrogation of a third person requires the consent of the original parties and of the third person. (n) b. By law or implied – Art. 1302 Art. 1302. It is presumed that there is legal subrogation: (1) When a creditor pays another creditor who is preferred, even without the debtor's knowledge; (2) When a third person, not interested in the obligation, pays with the express or tacit approval of the debtor; (3) When, even without the knowledge of the debtor, a person interested in the fulfillment of the obligation pays, without prejudice to the effects of confusion as to the latter's share. (1210a) Effects of subrogation: Art. 1303. Subrogation transfers to the persons subrogated the credit with all the rights thereto appertaining, either against the debtor or against third person, be they guarantors or possessors of mortgages, subject to stipulation in a conventional subrogation. (1212a) Art. 1304. A creditor, to whom partial payment has been made, may exercise his right for the remainder, and he shall be preferred to the person who has been subrogated in his place in virtue of the partial payment of the same credit. (1213) 2. Passive – if a third person is substituted to the person of the debtor. In this case, it should be clear to both parties that the new debtor is in lieu of the old debtor. a. Expromision - without knowledge or against the will of the original debtor • As to extent of reimbursement – Arts. 1236 and 1237 shall be applicable, as such, the new debtor can only recover only upto the extent that the old debtor was benefited. Art. 1293. Novation which consists in substituting a new debtor in the place of the original one, may be made even without the knowledge or against the will of the latter, but not without the consent of the creditor. Payment by the new debtor gives him the rights mentioned in Articles 1236 and 1237. (1205a) • As to right of the creditor when the new debtor becomes insolvent or fails to fulfil the obligation – he cannot run after the old debtor. Art. 1294. If the substitution is without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, the new debtor's insolvency or non-fulfillment of the obligations shall not give rise to any liability on the part of the original debtor. (n) b. Delegacion - with consent or knowledge of the original debtor but without any objection. Here, it is the debtor who offers the change. Parties: Delegante – the old debtor; Delegado – the new debtor Delegatorio – the creditor. • • As to extent of reimbursement – the whole amount paid regardless of the extent the old debtor was benefited. As to right of the creditor when the new debtor becomes insolvent – he can run after the old debtor, IF: the insolvency was already existing and of public knowledge, or known to the debtor. Otherwise, the creditor cannot run after the old debtor. Art. 1295. The insolvency of the new debtor, who has been proposed by the original debtor and accepted by the creditor, shall not revive the action of the latter against the original obligor, except when said insolvency was already existing and of public knowledge, or known to the debtor, when the delegated his debt. (1206a) Creditor’s consent – in any case, the creditor’s consent is necessary for there to be a novation in the person of the debtor as provided under Art. 1293. Objective or Real Novation 1. 2. Change in the object Change in the principal conditions of the obligation, which may either be: a. Express; or b. Implied: Art. 1292. In order that an obligation may be extinguished by another which substitute the same, it is imperative that it be so declared in unequivocal terms, or that the old and the new obligations be on every point incompatible with each other. (1204) Implied novation requires clear and convincing proof of complete incompatibility between the two obligations. The law requires no specific form for an effective novation by implication. The test is whether the two obligations can stand together. If they cannot, incompatibility arises, and the second obligation novates the first. If they can stand together, no incompatibility results and novation does not take place. (Millar vs. CA) It is elementary that novation is never presumed; it must be explicitly stated or there must be manifest incompatibility between the old and the new obligations in every aspect. (NPC vs. Dayrit and People’s Bank and Trust Company vs. Syvel’s Incorporated) Art. 1296. When the principal obligation is extinguished in consequence of a novation, accessory obligations may subsist only insofar as they may benefit third persons who did not give their consent. (1207) Accessory obligations: General Rule: extinguished as a consequence of novation. Exception: insofar as pour atrui is concerned and the third person for whose benefit the obligation was constituted did not give his consent. Art. 1299. If the original obligation was subject to a suspensive or resolutory condition, the new obligation shall be under the same condition, unless it is otherwise stipulated. (n)