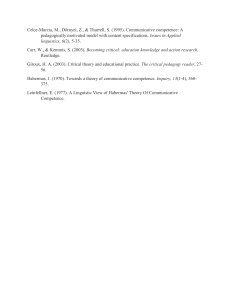

TEMA 4 – LA COMPETENCIA COMUNICATIVA. ANÁLISIS DE SUS COMPONENTES. Commmunicative competence. Analysis of its components. OUTLINE 1. INTRODUCTION 2. COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE 2.1. On defining “communicative competence” 2.1.1. Fluency over accuracy 2.1.2. Communicative competence: an issue in foreign language education 2.1.3. A communicative approach to language teaching 2.1.4. The introduction of cultural studies: a basis for an etnography of communication 3. A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODEL OF COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE 3.1. Chomsky: competence and performance 3.2. Halliday 3.3. Hymes 3.4. Sandra Savignon 3.5. Widdowson 3.6. Canale and Swain; and Canale 4. AN ANALYSIS OF COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE ELEMENTS 4.1. Grammatical competence 4.2. Sociolinguistic competence 4.3. Discourse competence 4.4. Strategic competence 5. CURRENT DIRECTIONS REGARDING COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE 5.1. Multimedia and hypermedia context 5.2. Implications into language teaching 6. CONCLUSION 7. BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. INTRODUCTION In the words of the writer Eric F. Douglas, “competence in communication does not come easily. Ground rules, like rules of the road, are necessary to avoid crashing into one another while we try to communicate”. This is why the aim of this topic is to offer a broad account of the concept of communicative competence, and the importance in society, and especially, in the language teaching community. The first section will start by reviewing communicative competence as a concept, mentioning the importance of fluency over accuracy, the communicative approach of language teaching and an introduction of ethnography of communication. The next section will develop different models of communicative competence such as the ones of Chomsky, Halliday, Hymes, Sandra Savignon, Widdowson and Canale & Swain. Following this section, there will be a further explanation of the communicative competence elements, being these grammatical competence, sociolinguistic competence, discourse competence and strategic competence. Finally, the last section will be focused on the current directions regarding communicative competence, such as the multimedia and hypermedia context and the implications of this into language teaching. 2. COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE The term was first coined by Hymes (1972) in relation to the speaker’s knowledge of how to use the language appropriately. Apart from the linguistic knowledge, the use of the language in appropriate ways to fulfill proper social functions requires other types of knowledge, such as social, strategic, etc. 2.1. On defining “communicative competence” 2.1.1. Fluency over accuracy Communicative competence is the central aim of foreign and second language teaching. This notion no longer describes just a particular proficiency or skill, but makes reference to more than listening and speaking, reading and writing. It is the ability to use appropriately all aspects of verbal and non-verbal language in a variety of contexts, as would a native speaker (Canale, 1983). There are two components to communicative competence under review. The first component is the linguistic competence, which involves the mastery of several features. First, the sound system and written system in order not to sound unusual to the cultural and linguistic ear although the grammar may be perfect. Secondly, the syntax. Thirdly, the stress, pitch, volume, and juncture as a passage from one sound to another in the stream of speech. Finally, the semantics and how, when, where, and why they are used in a language. This feature is to be found culturally implied, not explicitly taught. The second component includes pragmatics competence, which deals with knowing the appropriateness of communication formats, verbal and non-verbal responses and interactions in many contexts. We should highlight first, the appropriateness of action and speech in view of the speakers’ roles, status, ages, and perspectives. Secondly, the use of non-verbal codes. Next is to establish rapport, taking turns, and not to talk excessively, as well as initiating, contributing relevance to, and ending a conversation. Fourthly, the fact of being comprehensible, supplying all necessary information and requesting clarification when necessary. And finally, a feature that involves creating smooth changes in topic, and responding to timing and pauses in dialogue. These pragmatics elements are so powerful that the message can become distorted if some of them are missing. In developing communicative competence, learners need many opportunities to communicate without having to concentrate on structure and form, as being understood is much more important than using correct vocabulary or grammar. In communicative language teaching, the emphasis is on fluency and comprehensibility as opposed to accuracy. Fluency in speaking can be thought of as the ability to generate and communicate one’s ideas intelligibly and with relative ease but not necessarily with accuracy (Canale & Swain, 1980). We, as teachers, can provide opportunities for students to develop context-sensitive behaviour in order to become more aware of, and more adept at responding appropriately to social contexts. 2.1.2. A communicative approach to language teaching The period from the 1950s to the 1980s has often been referred to as “The Age of Methods”. Situational Language Teaching evolved in the UK while a parallel method, the Audio-Lingualism, emerged in the US. Both methods started to be questioned by applied linguistics who saw the need to focus in language teaching on communicative proficiency rather than on mere mastery of structures. Wilkins promoted a system in which learning tasks were broken down into units. This system attempted to demonstrate the systems of meanings that a language learner needs to understand and express within two types: notional categories and categories of communicative function. In the 1980s, the rapid application of these ideas by textbook writers and its acceptance by teaching specialists gave prominence to more interactive views of language teaching, which became to be known as the Communicative Approach or simply Communicative Language Teaching. In the 1970s and 1980s, an approach to foreign and second language teaching emerged both in Europe and north America. It concentrated on language as social behaviour, seeing the primary goal of language teaching as the development of the learner’s communicative competence. Parallel to the influence of the Council of Europe Languages Projects, there was an increasing need to teach adults the major languages for a better educational cooperation within the expanding European Common Market. The movement at first concentrated on notional-functional syllabuses, but in the 1980s, the approach was more concerned with the quality of interaction between learner and teacher rather than the specification of syllabuses and concentrated on classroom methodology rather than on content. Scholars such as Hymes, Halliday, Canale & Swain, or Chomsky leveled their contributions and criticisms at structural linguistic theories claiming for more communicative approaches on language teaching. Among the most relevant features that Communicative Language Teaching claimed for, it is important to highlight a set of principles that provide a broad overview of this method. The first principle claims for students to learn a language through using it to communicate. Secondly, there is an emphasis on authentic and meaningful communication which should be the goal of classroom activities. Thirdly, fluency is seen as pretty important. Fourth, communication is intended to involve the integration of different language skills, and finally, it claims for learning as a process of creative construction which involves trial and error. However, this is considered an approach rather than a method which provides a humanistic approach to teaching where interactive processes of communication receive priority. Its rapid implementation resulted in similar approaches among which we may mention The Natural Approach, Cooperative Language Learning, Content-Based Teaching, and Task-Based Teaching. 2.1.3. The introduction of cultural studies: a basis for an ethnography of communication Communicative competence also covers conditions that affect communication by means of socio-cultural competence in order to facilitate comprehensible interaction or to provide general knowledge of the world and the human nature. Not all sentences can be used in the same circumstances. For example, “Give me the salt!” and “Could you pass me the salt, please?” are both grammatical, but they differ in their appropriateness for use in particular situations. Speakers use their communicative competence to choose what to say, as well as how and when to say it. Hymes (1974) and others have stated that second language acquisition must be accompanied by a cultural knowledge acquisition in addition to communicative competence. Communicating implies not only choosing the appropriate words but also using the appropriate verbal and non-verbal behaviours. The more the knowledge the learner has to facilitate the understanding about a topic from a different culture, the easier it is for the learner to be an active participant, and to speak with ease and fluency. Once the constraint of a lack of background knowledge and information is eliminated, the learner has an opportunity to work on developing fluency and building communicative competence. There are several important strategies that a student should learn about the underlying cultural rules that guide conversation in the environment where they are speaking, such as using gestures, taking turns, or maintaining silence. These strategies vary from culture to culture, and they make relevant, therefore, the acquisition of a cultural knowledge in order to communicate effectively. This tradition on cultural studies was first introduced in a language teaching theory in the early 1920s and improved in the 1970s by the notion of the “ethnography of communication”, a concept coined by Hymes. It refers to a methodology based on anthropology and linguistics allowing people to study human interaction in context. Cultural relativity sees communicative practices as an important part of what members of a particular culture know and do (Hymes, 1972). They acknowledge speech situations, speech events, and speech acts as units of communicative practice and attempt to situate these events in context in order to analyse them. Hymes’ (1972) SPEAKING heuristic serves a framework in which the ethnographer examines several components of speech events as follows: - S: setting and scene. - P: participants (speaker, sender, and addresser) - E: end - A: act sequence - K: key - I: instrumentalities - N: norms of interaction and interpretation - G: genre This interpretation of communicative competence can serve as a useful guide to help second language learners to distinguish important elements of cultural communication as they learn to observe and analyse discourse practices of the target culture in context. 3. A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODEL OF COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE These two terms, culture and language, are directly related to the notion of communicative competence as cultural, and linguistics studies provide the basis for a communicative approach in language teaching. 3.1. Chomsky: competence and performance Chomsky introduced “competence” and “performance” as part of the foundations for his generative grammar. He distinguished the underlying knowledge of language from the way language is actually used in practice. According to him, language performed may be affected by things as attention, stamina, memory, etc. Competence is a person’s underlying linguistic ability to create and understand sentences, including sentences they have never heard before. It includes phonetics, phonology, syntax, semantics and morphology and it enables native speakers to recognize ambiguous sentences or accept apparently meaningless sentences as syntactically correct. Performance is a real-world linguistic output. It may be flawed because of memory limitations, distractions, shift of attention and interest and errors or other psychological factors. The performance may not be fault free, even though his competence is perfect. It is important to make a distinction because it allows those studying a language to differentiate between speech error and not knowing something about the language. 3.2. Halliday In 1985, Halliday declared in his work An Introduction to Functional Grammar, that “the value of a theory lies in the use that can be made of it”. Halliday emphasizes the functions of language in use by giving prominence to a social mode of expression. At this point, meaning is considered as a product of the relationship between the system and its environment, constructing reality as configurations of people, places, things, qualities, and different circumstances. To Halliday, messages combine an organization of content according to the receptive needs of the speaker and listener, an the meaning they are expressing. There are three macro-functions that provide the basic functions on learning a foreign language: ideational, interpersonal, and textual. Ideational represent our experience of phenomena in the world framed by different processes and circumstances which are set in time by means of tense and logical meanings. Interpersonal is shaped by the resources of modality and mood to negotiate the proposals between interactants in terms of probability, obligation or inclination, and to establish and maintain an ongoing exchange of information by means of grammar through declaratives, questions, and commands. Lastly, textual is concerned with the information as text in context at a lexicogrammatically level. On combining these interrelated functions, Halliday proposes seven basic functions on language use, and they are listed as follows: 1. Instrumental: desires and needs. 2. Regulatory: rules, instructions, orders, and suggestions. 3. Interactional: patterns of greeting, thanking, good wishes, etc. 4. Personal: talk about yourself and express your feelings. 5. Heuristic: asking questions. 6. Imaginative: supposing, hypothesizing, and creating for the love of sound and image. 7. Informative: affirmative and negative statements. Halliday’s functional grammar model provides a description of how the structure of English relates to the variables of the social context in which the language is functioning. It is uniquely productive as an educational resource for teaching how the grammatical form of language is structured to achieve purposes in a variety of social contexts. 3.3. Hymes Dell Hymes pointed out that Chomsky’s competence-performance model did not provide an explicit place for sociocultural features, adding that Chomsky’s notion of performance seemed confused between actual performance and underlying rules of performance. He recasts the scope of the competence concept because there is a lack of empirical support in Chomsky’s model, and he feels that there are rules of use without which the rules of grammar would be useless. Hymes introduced the concept of communicative competence, paying special attention to the sociolinguistics component, which connected language and culture. Hymes (1972) stated that native speakers know more than just grammatical competence. He expanded the Chomskyan notions of grammaticality and acceptability into four parameters subsumed under the heading of communicative competence as something which is first, formally possible, secondly, feasible in virtue of the available means, thirdly, appropriate, in relation to a context, and finally, something which is in fact done. Hyme’s model is, then, primarily sociolinguistic, but includes Chomsky’s psycholinguistic parameter of linguistic competence. It is also primarily concerned with explaining language use in social contexts, although it also addresses issues of language acquisition. His model inspired subsequent model developments on communicative competence, such as those of Canale and Swain and Bachman. 3.4. Sandra Savignon Simultaneously to Hymes, the first well-recognized experiment of communicative language teaching was taking place at the University of Illinois. The American linguist, Sandra Savignon in 1972, was conducting an experiment with foreign language learners, particularly adults, in a classroom at a beginner’s level. It was an attempt towards an interactional approach where learners were encouraged to make use of their foreign language in a classroom setting, by means of equivalents of expressions in order to communicate rather than feign native speakers. Savignon’s experiment is considered to be one of the best-known surveys as it shed light on the development of research in this field. She introduced the idea of communicative competence as the ability to function in a truly communicative setting – that is, in a dynamic exchange in which linguistic competence must adapt itself to the total information input, both linguistic and paralinguistic, of one or more interlocutors. She included the use of gestures and facial expression in her interpretation and later refined her definition of communicative competence to comprise of the following six relevant aspects (Savignon, 1983). The first feature is the individual’s willingness to take risks and express themselves in foreign language and to make themselves understood (negotiation of meaning). Secondly, communicative competence is not only oral, but written too. Thirdly, the approach to appropriateness as depending on the context. fourthly, only performance is observable as it is only through performance that competence can be developed, maintained, and evaluated. Fifthly, communicative competence to be relative, and not absolute, as it comes in degrees because it depends on the cooperation of all interlocutors. Finally, she talks about degrees of communicative competence which is difficult to measure. Savignon’s model was not the only result of those theoretical and empirical investigations which were carried out in the early 1980s in the field of communicative language teaching. Though not able to agree on operational definitions of the components of the components of communicative competence, all scholars recognized the sociocultural component to be an inseparable part of foreign language communicative competence. 3.5. Widdowson Widdowson (1978) proposed a distinction between the concepts of use and usage. Both concepts are to be linked to the aspects of performance, as usage refers to the manifestation of the knowledge of a language system whereas the notion of use means the realization of the language system as meaningful communicative behaviour. This duality is based on the notion of effectiveness for communication, by means of which an utterance with a well-formed grammatical structure may or may not have a sufficient value for communication in a given context. He claimed that whether an utterance has a sufficient communicative value or not is determined in discourse. 3.6. Canale and Swain; and Canale It seems a particularly relevant idea to those interested in second language learning, as the relevance of a theory of communicative competence to language by means of testing was first noted by Cooper and explored by Canale and Swain (1980) and Canale (1983). Language tests involve measuring a subject’s knowledge of, and proficiency in, the use of a language. Communicative competence, according to them, is then a theory of the nature of such knowledge and proficiency. A preference model appears to be a useful way to characterize communicative competence, and at the same time, it has many advantages over competing models. They formulated a theoretical framework that, in the modified version of Canale (1983), consisted of four major components of communicative competence. They are the following: - Grammatical competence: mastery of the linguistic code itself. - Sociolinguistic competence: concerned with the appropriate use of language in particular social situations to convey specific communicative functions such as describing, narrating, or eliciting among others. - Discourse competence: mastery of how to use language in order to achieve a unified spoken or written text in different genres. - Strategic competence: mastery of verbal and non-verbal communication strategies by means of both the underlying knowledge about language and communicative language use or skill. 4. AN ANALYSIS OF COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE ELEMENTS 4.1. Grammatical competence All knowledge of lexical items and of rules of morphology, syntax, sentence-grammar semantics, and phonology (Canale & Swain, 1980). It refers to having control over the purely linguistic aspects of the language code itself, regarding verbal and non-verbal codes. This corresponds to Hymes’ grammatical aspect and includes knowledge of the lexicon, syntax, phonology, and semantics. It involves rules of formulations and constraints for students to match sound and meaning, to form words and sentences using vocabulary, to use language through spelling and pronunciation, and to handle linguistic semantics. 4.2. Sociolinguistic competence It refers to the knowledge which the learner has to acquire of the sociocultural rules of language. Canale and Swain (1980) defined this competence in terms of sociocultural rules of use, and rules of discourse. Concerning sociocultural rules of use, this competence is linked to the notion of the extent to which utterances are produced and understood appropriately in different sociolinguistic contexts. Regarding the rules of discourse, it is defined in terms of the mastery of how to combine grammatical forms and meanings. When we deal with appropriateness of form, we refer to the extent to which a given meaning is represented in both verbal and non-verbal form that is proper in a given sociolinguistic context. In relation to meaning appropriateness, this competence is concerned with the extent to which particular communicative functions and ideas are judged to be proper in a given situation, as for instance, complaining, commanding and inviting. 4.3. Discourse competence Discourse analysis is primarily concerned with the ways in which individual sentences connect together for form a communicative message. This competence addresses directly to the mastery of how to combine grammatical forms and meaning to achieve a unified spoken or written text in different genres (Canale & Swain, 1980). By genre is meant the type of text to be unified, for example, a scientific paper, an argumentative essay, among others. The unity of a text is achieved through cohesion in form and coherence in meaning. Cohesion deals with how utterances are linked structurally and facilitates interpretation of a text by means of cohesion devices. Coherence refers to the relationships among the different meanings in a text, where these meanings may be literal meanings, communicative functions, and attitudes. 4.4. Strategic competence In the words of Canale (1983), strategic competence is the verbal and non-verbal communication strategies that may be called into action to compensate for breakdowns in communication due to performance variables or due to insufficient competence. We can describe it as the type of knowledge which we need to sustain communication with someone. This may be achieved by paraphrase, circumlocution, repetition, hesitation, avoidance, guessing as well as shifts in register and style. According to them, strategic competence is useful in various circumstances as for instance, the early stages of second language learning where communicative competence can be present with just strategic and sociolinguistic competence. This approach has been supported by other researchers, such as Savignon and Tarone. Savignon (1983) noted that one can communicate non-verbally in the absence of grammatical or discourse competence provided there is a cooperative interlocutor. She pointed out the necessity and the sufficiency for the inclusion of strategic competence as a component of communicative competence at all levels. Another criterion on strategic competence is the use of the strategies to help getting the meaning across. Tarone (1981) includes a requirement for the use of strategic competence by which the speaker has to be aware that the linguistic structure needed to convey his meaning is not available to him or to the hearer. 5. CURRENT DIRECTIONS REGARDING COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE Although traditionally, foreign language teachers have used media, or devices we use to store, process, and communicate information, technological developments have altered the type of media foreign language students encounter. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Audiolingual Method introduced audiotaped dialogues to the learning situation. Years later, researchers have begun investigating multimedia and hypermedia contexts for foreign language and culture acquisition. 5.1. Multimedia and hypermedia contexts Providing experiences for contact with language in context may prove difficult for foreign language teachers. Constrained by lack of sufficient access to the target culture, teachers often rely on textbooks and classroom materials in teaching language. These materials may not necessarily provide the required environment for the acquisition of communicative competence. It is suggested that through the medium of video, students receive massive doses of comprehensible input, and that video can provide target language speech or texts that include challenging yet understandable portions. Nowadays, not we can find videos in real context in platforms like YouTube or social networks such as Twitter, TikTok or Instagram, with which students may relate and find easier to learn vocabulary or improve skills like listening or even speaking. This is because when the target language is presented in context, in this case in the form of video, the meaning of specific words and utterances becomes clear to the learner. Hypermedia and multimedia environments may also provide a more appropriate context for students to experience the target culture. Present-day approaches deal with a communicative competence model in which first, there is an emphasis on significance over form, and secondly, motivation and involvement are enhanced. This requires creating classrooms conditions which match those in real life and foster acquisition, encouraging learning. Some of this motivational force is brought about by intervening in authentic communicative events. Otherwise, we have to recreate as much as possible the whole cultural environment in the classroom. Second, the linear nature of textbooks affords students a rather restricted experience of the content and does not allow for navigational freedom or interactivity that modern technological tools such computers, interactive board or projectors. This method relies on a notion of communicative competence which takes place first, in foreign language classrooms where the effectiveness of communication is to be acquired, and secondly, in multimedia and hypermedia environments which support the acquisition of communicative competence. 5.2. Implications into language teaching The practicality of implementing ethnographic approaches to foreign language and culture learning is questionable. For example, sometimes, students do not have direct access to members of the target culture, or to a range of individuals representing much of the communicative repertoire of that culture. Furthermore, traditional means of contact with the target culture, such as textbooks do not provide a proper context for ethnographic investigation. Nevertheless, we must point out that nowadays, more often than not, students have the help of conversation auxiliaries at school who come from English speaking countries. Also, some high schools offer exchanges with students from other countries which give them the opportunity to learn the foreign language in a real context. In order to understand communicative practices, second language learners must see members of the target culture use them in authentic situations and must have access to the ground of meaning attached to those practices. In essence, textbooks generally provide students prescriptive phrases with which to communicate without providing insights as to contextual influences of these utterances. They also fail to represent the linguistic repertoire of speech communities as they typically depict a rather monolithic speech community, neglecting to portray the heterogeneous nature of the target cultures’ speakers. If the goal of foreign language teaching is to develop communicative competence among foreign language students, then we must address sociolinguistic aspects of language and provide students opportunities to access the meaning associated with language practices. By ignoring these aspects of communication in foreign language classroom, we are not providing our students essential elements of human interaction, for spoken language must be presented in the full context of communication. 6. CONCLUSION A review of this topic has been developed throughout different sections. First, I referred to the communicative competence as a term, in an attempt to define it and set the basis for the rest of the topic. Then, a historical overview of the development of the model of communicative competence was explained, mentioning the models of Chomsky, Halliday, Hymes, Sandra Savignon, Widdowson and Canale & Swain. After that, there was an analysis of the elements of the communicative competence, being those grammatical, sociolinguistic, discourse and strategic competence. In the last section, I focused on the current directions regarding communicative competence, taking into account the multimedia and hypermedia contexts, and the implications into language teaching which is of special relevance for us as teachers. For generations, language teachers have attempted to overcome students’ goal of achieving communicative competence with the use of realia or authentic materials in the classroom. However, the use of these materials does not necessarily result in an interpretation of the intent of the message that matches those members of the target culture. What it is clear is that without an understanding of native viewpoints, second language and culture learners may be incapable of accessing and interpreting the meaning of communication in the target language as intended by member of that culture. As the philosopher Frantz Fanon said, “to speak a language in to take on a world, a culture”. 7. BIBLIOGRAPHY - Canale, M. & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education. - Canale, M. (1983). “From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy”. In C. Richards & R. Schmidt (Eds.): Language and Communication. New York: Longman. - Hymes, D. (1972). “On communicative competence”. In J. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.): Sociolinguistics. Harmondsworth: Penguin. - Hymes, D. (1974). Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. - Savignon, S. (1983). Communicative Competence: Theory and Classroom Practice. Reading, Mass.: AddisonWesley. - Tarone, E. (1981). Some Thoughts on the Notion of Communication Strategy. TESOL Quarterly. - Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching Language as Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.