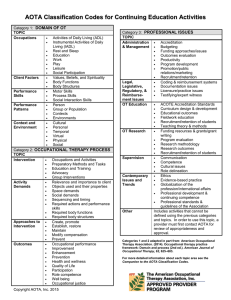

Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale: Interrater Agreement and Construct Validity Milena Jankovich, Jacqueline Mullen, Erin Rinear, Kari Tanta, Jean Deitz KEY WORDS • evaluation • development • pediatrics • play OBJECTIVE. Interrater agreement and construct validity of the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale (RKPPS) were examined. METHOD. Two separately trained raters evaluated 38 typically developing children, ages 36 to 72 months. For each child, the raters observed two 15-min free-play sessions. RESULTS. For the overall play age, the scores of the two raters were within 8 months of each other 86.8% of the time; for the 4 dimension scores, they were within 12 months of each other 91.7% to 100% of the time; and for the 12 category scores, they were within one age level of each other 81.8% to 100% of the time. Construct validity results showed a general match between the children’s chronological ages and their overall play age scores. CONCLUSIONS. Findings suggest that two raters can score the RKPPS with some consistency and that scores on this measure progress developmentally, thus supporting its construct validity. Jankovich, M., Mullen, J., Rinear, E., Tanta, K., & Deitz, J. (2008). Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale: Interrater agreement and construct validity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 221–227. Milena Jankovich, MOT Student, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Jacqueline Mullen, MOT Student, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Erin Rinear, MOT Student, Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Kari Tanta, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA, is Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington and Program Coordinator, Children’s Therapy Department, Valley Medical Center, Seattle. Jean Deitz, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA, is Professor, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Box 356490, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; deitz@u.washington.edu P lay is an important performance area of occupation to a child (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2002). Through play, children learn to communicate, grow, and build the skills necessary to function in society (Knox, 2005; Richmond, 1960). According to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (AOTA, 2002), participating in play is a fundamental part of growth and development throughout the life span. Motor, process, and communication and interaction skills need to be integrated for a child to be a successful player. If a child has sensorimotor, emotional, or social deficits, his or her ability to play may be compromised. One of the roles of occupational therapists is to facilitate play to ensure quality of life and optimal developmental outcomes (Takata, 1969). Measures of play approximate cognitive and developmental level (Bergen, 1988), and observation of play gives occupational therapists the ability to evaluate motor, process, and communication and interaction skills (AOTA, 2002). By evaluating play behaviors, a therapist can measure developmental competence and change in a child (Schaaf & Mulrooney, 1989) and observe play deficits and the effectiveness of treatment on improving play skills (Bundy, 1991). Assessing the occupation of play is also used to determine eligibility for services for children with special needs, to facilitate intervention planning, and to understand a child’s preferred activities (Lifter, 1996). To meet these aims, occupational therapists conducting play observations need “a systematic means of observing play behavior to determine a child’s play assets, skills, and deficits” (Bledsoe & Shepherd, 1982, p. 783). Although assessing play is important, it is not an easy construct to measure. Knox (2005) contended that play is difficult and time-consuming to measure because of the need to observe the child engaged in the occupation of play. Several The American Journal of Occupational Therapy Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/10/2015 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms 221 authors (Bundy, 1991; Knox, 2005; Smith, Takhvar, Gore, & Vollstedt, 1985) stated that, to get a complete assessment or observation of play, it must be conducted in multiple environments. These challenges in measuring the construct of play make it difficult for occupational therapists to find an appropriate measurement tool to use. According to Couch (1996, p. 77), “Assessment of play skills in pediatrics is a critical aspect of developmental evaluation, yet therapists are challenged to find tools to reach this aim.” The field of occupational therapy is currently addressing the need for the development of measurements of play behaviors. Occupational therapists use several assessments of play, each of which yields a different measure of the construct of play. Although some of these assessments were developed years ago, they are still being used or revised for current practice. We highlight those frequently referenced in the literature. The Parten Social Play Hierarchy (Parten, 1932), Lunzer’s Scale of Organization of Play Behavior (Lunzer, 1959), Guide to Play Observation (Robinson, 1977), Growth Gradient (Michelman, 1971), and Guide to Status of Imitation (deRenne-Stephan, 1980) examine important components of play (e.g., learning and organization of rules, creativity, and imitation) but not play as an overall outcome. The Play History (Takata, 1969) is a qualitative assessment of play through interview and observation that provides a description of a child’s play behavior but does not describe it according to a developmental scheme. The Play Skills Inventory (Hurff, 1974) measures four play skills in the areas of sensation, motor, perception, and intellectual functioning and is conducted by observing predetermined activities. The Preschool Play Scale (Bledsoe & Shepherd, 1982) examines play as an overall outcome according to a developmental scheme. In a study addressing the use of specific assessment tools designed to evaluate play behaviors, Couch, Deitz, and Kanny (1998) found that the Preschool Play Scale was used most frequently by pediatric occupational therapists. These investigators further identified the Preschool Play Scale as a promising tool in need of additional study. Since then, the Preschool Play Scale has undergone several changes and has been used as a research and clinical tool (Bundy, 1989; Restall & Magill-Evans, 1994). The current version of the Preschool Play Scale, the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale (Knox, 1997), can be best understood by examining its history of development and revision. Knox (1974) developed a play assessment, called A Play Scale, to aid in determining children’s developmental play ages. The tool has three main advantages. First, it was designed to cover all areas of development and to reflect developmental status (Knox, 1997, p. 46). Second, it is applicable for use with children who are unable to perform a standardized developmental assessment because the ­children are observed participating in play as they normally would. Third, it assesses children in their natural environments. In 1982, Bledsoe and Shepherd revised and renamed the scale the Preschool Play Scale to reflect current findings in the play literature. The scale was further revised by Knox (1997) after “review of its usefulness . . . and limitations” (p. 46) and renamed the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale (RKPPS). Changes were made related to scoring increments, clarity of descriptors, and recent findings related to play development (Bergen, 1988; Knox, 1997; Rubin, Fein, & Vandenberg, 1983). Examples of changes, based on findings related to stages of play development (Bergen, 1988), include the addition of “pretend with replica toys” and “uses one toy to represent another” as descriptors to the Dramatization category and of “games with rules” as a descriptor to the Cooperation category. The RKPPS consists of the 4 dimensions and 12 categories of play behaviors (Knox, 1997) depicted in Figure 1. The resulting play age and play profile provide therapists with useful information to plan and implement intervention. Although the RKPPS is available for use, occupational therapists continue to use the Preschool Play Scale rather than the RKPPS because reliability and validity data are available for the Preschool Play Scale (K. Tanta, personal communication, September 15, 2005). To improve the RKPPS’s clinical utility, its psychometrics merited examination. Specifically, interrater agreement data were needed because of the subjectivity of scoring; also, to examine its construct validity, it was important to know whether children who are typically developing score in their expected age categories. Therefore, the research questions for this study were as follows: • What is the interrater agreement for the RKPPS for the overall play age score, for each of the 4 dimension scores, and for each of the 12 category scores? and • How do the RKPPS overall play age scores of typically developing children relate to the children’s chronological ages? Method Participants A convenience sample of children from the greater Seattle area participated in this study. This sample consisted of 38 children, 17 boys and 21 girls. Seven boys and 7 girls were 36 to 48 months old; 6 boys and 11 girls were 48 to 60 months old; and 4 boys and 3 girls were 60 to 72 months old. All children involved in the study were typically developing, had parental consent, and gave verbal assent to participate in the study. A child information form completed by a parent was used to determine whether a child was 222 Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/10/2015 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms March/April 2008, Volume 62, Number 2 communication, October 11, 2005), we decided to use two 15-min sessions. This is also congruent with the decision of Harrison and Kielhofner (1986) to use two 15-min observations in their study using the Preschool Play Scale. Additionally, although the age range for the RKPPS is from birth to 72 months, we focused on children ages 36 to 72 months because our clinical experience suggested that this is the age group for which this measure is used most frequently. Procedure Study Design and Scale Administrators Figure 1. Dimensions and categories of the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale. t­ ypically developing. “Typically developing” was defined as not having diagnoses such as autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, or developmental delay; not having current or prior special education or therapy services; and not using crutches, canes, walkers, wheelchairs, or other mobility aids at the time of the study. Setting Following approval from the human subjects institutional review board at the University of Washington, children were recruited for this study from the Experimental Education Unit at the University of Washington and two private preschools. Children in these programs tend to come from families of middle to high socioeconomic status. All settings had free-play periods, both indoors and outdoors, integrated into children’s classroom routines. Each child had participated in his or her respective free-play periods for at least 1 month before observation. A variety of toys and play equipment were available, including items such as dramatic and pretend play props, construction toys, arts and crafts supplies, and playground equipment. Two or more children were in a play space (playground, gym, classroom) at any given time, allowing opportunities for peer interaction. Instrumentation The RKPPS is an observational measure that allows therapists to evaluate the play of children ages birth to 72 months in their natural environments (Knox, 1997). Per the instructions, a child should be observed for two 30-min sessions in two different settings, one indoors and one outdoors. However, after consultation with the test developer, who stated that it was acceptable to use two 15-min sessions (S. Knox, personal communication, August 24, 2005), and with an experienced pediatric therapist, who indicated that a full hour of observation was not practical (K. Tanta, personal If a test has good interrater reliability, it is assumed that two individuals who prepare separately (i.e., therapists working in different clinics) will score it similarly. Therefore, for the purposes of this study, the primary scale administrators (two master of occupational therapy students [MOT1 and MOT2]) prepared separately and did not communicate with each other with regard to concepts, administration, or scoring. Neither had experience with the RKPPS before the study. Before data collection began, each student read and studied information published about the RKPPS and practiced using it with several children who were typically developing. The latter continued until each of the scale administrators was scoring consistently with her partner. MOT1 trained with an experienced therapist who had used the Preschool Play Scale extensively in her clinic and was very familiar with the RKPPS. MOT2 trained with MOT3, who also had previously been unfamiliar with the RKPPS. Before and during data collection, MOT2 and MOT3 communicated with the creator of the RKPPS for clarification of concepts, definitions, and scoring. This allowed each primary scale administrator access to a person with expert knowledge of the RKPPS. Training continued until each of the scale administrators was scoring consistently with her partner. During data collection, observer drift was monitored after assessment of every 15 participants. This was accomplished by each primary administrator scoring one child with her original training partner. Scoring The RKPPS provides numerous scores, including an overall play age, 4 dimension ages, and 12 category ages. Descrip­tors (e.g., “uses words to communicate with peers,” “communicates with peers to organize activities”; Knox, 1997, p. 49) illustrate the developmental play progression within the context of the 12 categories and 4 dimensions. The developmental progression is broken down in 6-month increments from 0 to 36 months (e.g., 12–18 months) and 12-month increments from 36 to 72 months (e.g., 36–48 months). The American Journal of Occupational Therapy Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/10/2015 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms 223 To determine each category score, the rater must review all descriptors and decide at which age level they are representative of the child’s play behavior, as opposed to emerging skills. Because some of the printed instructions for scoring the RKPPS have been identified by therapists as being unclear, Kari Tanta, with approval from the test developer, wrote supplemental instructions (S. Knox & K. Tanta, personal communication, October 11, 2005). The Tanta method of scoring involves giving a child credit within an age category only for those behaviors that are truly representative of the child’s play behavior and not for emerging skills or behaviors that occur fleetingly. This method was used in combination with the instructions that accompany the RKPPS. As raters observe play behaviors, a mark is placed over the corresponding descriptors and then scored by looking at the respective age level (Knox, 1997). For example, if a rater places a mark in the 36- to 48-month age level, the child is scored as 48 months. A dimension score is the mean of its category scores, and the overall play age score is the mean of the four dimension scores (Knox, 1997). In situations in which a category behavior is not exhibited during the time of observation, a rater has an option of scoring a child with an NA (not applicable). Although not described in the chapter regarding the RKPPS (Knox, 1997), Knox and Kari Tanta (personal communication, October 11, 2005) indicated that a rater also has the option of asking a child an open-ended question if necessary in an attempt to more clearly identify the type of play in which the child is engaging (e.g., “What are you playing?). For purposes of this study, the requirement that both raters hear the question and response was added. Data Collection Once parental consent and child assent were obtained and the child information form was completed, the administrators began observing. They positioned themselves in the child’s environment for a minimum of 5 min before beginning official observations. This was done to help control for the novelty of having new people in the child’s environment. Each child was observed for two 15-min free-play sessions (Harrison & Kielhofner, 1986), one indoors and one outdoors. For each child, these generally took place on the same day. When this was not possible, observations were completed within 1 week to control for the possibility of developmental changes. The two administrators refrained from communicating with each other with regard to the RKPPS throughout all testing. Each administrator kept a log in which she described the dimensions and categories she found to be particularly challenging and the reasons why. These were later used to determine whether there were specific sections of the RKPPS that were consistently unclear to both administrators and thus potentially in need of further review by the test developer. Data Analysis Because of the nature of the data generated by the RKPPS, scorer consistency related to the first research question was examined using percentage of agreement rather than reliability statistics (e.g., Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients, intraclass correlation coefficients). According to Tinsley and Weiss (1975), one of the benefits of this approach is that it “represents the extent to which different judges tend to make exactly the same judgments about the rated subject” (p. 359). This approach is clinically relevant, and using this approach also makes it possible to examine the extent of agreement within increasing magnitudes of difference (e.g., determining percentage of agreement for ratings in the category of participation within a 6-month window rather than looking exclusively at exact matches). Relative to the second research question, number and percentage of children in each age category with each play score were reported. Results Findings related to the first research question regarding the interrater agreement for the RKPPS appear in Table 1 for the overall play age score; in Table 2 for the four dimension scores; and in Table 3 for the 12 category scores. Table 1 shows the magnitudes of difference in the RKPPS overall play age scores assigned by the two raters and the cumulative numbers and percentages according to the magnitudes of difference in months. For the overall play age, the scores of the two raters were within 8 months of each other almost 87% of the time. Table 2 summarizes the cumulative number and percentage of children scored in each dimension according to the magnitudes of difference in months. For example, in the material management dimension, the two raters scored 36 children (94.7% agreement) within a magnitude of difference of 12 months or less. Table 1. Magnitudes of Difference in Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale Overall Play Age Scores Assigned by the Two Scale Administrators Magnitudes of Difference in Months n % Cumulative n Cumulative % 0 0.1–2.0 2.1–4.0 4.1–6.0 6.1–8.0 >8 1 2.6 1 2.6 11 28.9 12 31.5 9 23.7 21 55.2 7 18.4 28 73.6 5 13.2 33 86.8 5 13.2 38 100.0 Note. N = 38. 224 Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/10/2015 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms March/April 2008, Volume 62, Number 2 Table 2. Cumulative Magnitudes of Difference in Age Scores for Each Dimension of the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale Magnitudes of Difference in Months Dimension Space management (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % Material management (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % Pretense–symbolic (n = 36a) Cumulative n Cumulative % Participation (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % 0 0.1–2.0 2.1–4.0 4.1–6.0 6.1–8.0 8.1–12.0 >12 16 42.1 16 42.1 16 42.1 31 81.6 31 81.6 38 100.0 38 100.0 6 15.8 9 23.7 16 42.1 27 71.1 29 76.3 36 94.7 38 100.0 15 41.7 15 41.7 15 41.7 26 72.2 26 72.2 33 91.7 36 100.0 8 21.1 8 21.1 21 55.3 24 63.2 33 86.8 37 97.4 38 100.0 One rater gave one child an NA rating, and two raters gave one child an NA rating. a Table 3. Magnitudes of Difference in Age Scores Assigned by the Two Scale Administrators for Each Category Score of the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale Magnitudes of Difference in Age Levela Category Space management Gross motor (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % Interest (n = 22) Cumulative n Cumulative % Material management Manipulation (n = 35) Cumulative n Cumulative % Construction (n = 28) Cumulative n Cumulative % Purpose (n = 22) Cumulative n Cumulative % Attention (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % Pretense/symbolic imitation (n = 36) Cumulative n Cumulative % Dramatization (n = 36) Cumulative n Cumulative % Participation Type (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % Cooperation (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % Humor (n = 11) Cumulative n Cumulative % Language (n = 38) Cumulative n Cumulative % 0 1 2 3 NA 22 57.9 37 97.4 38 100.0 38 100.0 0 14 63.6 22 100.0 22 100.0 22 100.0 16 17 48.6 34 97.1 35 100.0 35 100.0 3 17 60.7 25 89.3 28 100.0 28 100.0 10 11 50.0 22 100.0 22 100.0 22 100.0 16 15 39.5 35 92.1 37 97.4 38 100.0 0 17 47.2 32 88.9 36 100.0 36 100.0 2 23 63.9 35 97.2 36 100.0 36 100.0 2 21 55.3 38 100.0 38 100.0 38 100.0 0 22 57.9 38 100.0 38 100.0 38 100.0 0 9 81.8 9 81.8 10 90.9 11 100.0 27 25 65.8 38 100.0 38 100.0 38 100.0 0 Table 4. Children in Each Category With Each Play Age Score 0 = same age level; 1 = within 1 age level difference; 2 = within 2 age levels difference; 3 = within 3 age levels difference. a Table 3 relates to the category scores within each separate dimension. It shows the number of times the two raters scored participants in the same age level, within one age level difference, within two age levels difference, or within three age levels difference. The two raters agreed within one age level difference between 81.8% and 100% of the time on all 12 categories in the RKPPS. Table 4 summarizes the findings for the second research question regarding how children who are developing typically score on the RKPPS and the relationship of these scores to their chronological ages. This question examines one aspect of construct validity, defined by Anastasi and Urbina (1997, p. 126) as “the extent to which the test may be said to measure a theoretical construct or trait” such as play. According to these authors, “Since abilities are expected to increase with age during childhood, it is argued that the test scores should likewise show such an increase, if the test is valid” (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997, p. 127). The findings reported in Table 4 support the construct validity of the RKPPS because the vast majority of the overall play ages assigned by the two raters matched the children’s chronological ages. However, the match was stronger for the older age groups than for those in the 36- to 47-month age range. For that group, 6 of the 14 children earned play age scores that were higher than their chronological ages. Average Play Age Score (Months) Actual Age (Months) 36–47 (n = 14) 48–59 (n = 17) 60–72 (n = 7) The American Journal of Occupational Therapy Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/10/2015 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms 36–47 48–59 60–72 n % n % n % 8 57.1 5 16 35.7 94.1 1 1 7 7.1 5.9 100.0 225 Discussion This study focusing on the RKPPS resulted in two major findings. First, two independently trained raters can generally score within 8 months of each other on the overall play age, within 12 months on the 4 dimension scores, and within one age level on the 12 category scores. Second, the construct validity of the RKPPS was supported because there was a general match between the children’s chronological ages and their overall play ages. Because play is a developmental construct, a valid measure of it should produce scores that reflect a developmental progression (Dunn, 1989). Experiences associated with the data collection, combined with the research findings, resulted in three recommendations for improving the RKPPS. The first is to provide more detail regarding interpreting play behaviors and scoring. Although the interrater agreement was acceptable, each rater reported challenges in scoring whereby she often debated between two scores for a single item. Therefore, it is likely that interrater agreement could be improved by providing more information with the measure. Specifically, it would be helpful to have thorough descriptions of specific behaviors and examples of play behaviors with their appropriate scores. These descriptions could provide a framework for interpreting specific play behaviors and measuring these behaviors consistently. Also, a scoring module could be developed that therapists could complete when learning to use the RKPPS. It could include a practice video of a child playing and a scoring key that the therapist could use to check his or her scores against after completing the RKPPS. A second recommendation is that the guidelines for the use of an occasional open-ended question to the child to clarify a play scenario (S. Knox, personal communication, October 11, 2005) be adopted and included in future versions of the RKPPS. An example of an open-ended question is “What are you doing?” The therapist might ask this question when he or she sees a boy sweeping with a broom. The child’s response might reveal that the boy is not just sweeping but pretending to clean his house for expected guests. Knowing such information facilitates interpretation of the behavior and accuracy in scoring. Third, the possibility of allowing a rater to use an occasional prompt to encourage a child to engage in a type of play the rater needs to observe should be explored. The raters in the current study noted that some children engaged in the same play activity for the duration of the observation. Therefore, to encourage engagement in other types of play so the child’s play can be assessed accurately, prompts may be useful. An example of a prompt might be to place blocks in front of a child and ask, “What can you do with these?” It would be necessary to outline a protocol for the use of such prompts, ensuring that they are compatible with a natural play context, as defined by the measure. Clinical Implications This study provides suggestions regarding clinical use of the RKPPS. First, because the magnitudes of difference between the two raters’ scores for the overall play age were within 8 months of each other the vast majority of the time (86.8% agreement; Table 2), the findings suggest that if a child receives a score up to 8 months below his or her chronological age, there is potentially no cause for concern. This discrepancy between the chronological age and the overall play age score could be caused by individual differences in scoring and is not necessarily an indication that the child has play deficits. However, if a child’s score falls more than 8 months below his or her chronological age and this finding is congruent with other assessment results, further evaluation may be warranted. Second, if an occupational therapist were to use the RKPPS, he or she can have some confidence in the developmental progression of the scale in light of the general match between the overall play ages and the chronological ages of the children. However, therapists should note that 43% of the 36- to 47-month-olds had average play age scores above their play age category, suggesting that this scale may provide an overestimate of these children’s play ages. Last, therapists should be cautious about generalizing these results to children from other cultures and from other socioeconomic groups. Strengths and Limitations An important strength of this study’s design is that the two raters trained separately and did not communicate with regard to the scale during data collection. This approach supports the clinical utility of the RKPPS because two raters from different settings should be able to obtain similar results when evaluating the same child if they each study the instrument thoroughly, practice giving the scale, and check interrater agreement with a colleague. There were two primary limitations of this study. The first was that the sample was homogeneous, with the children being typically developing and tending to come from middle to upper socioeconomic status urban and suburban areas. The second was that the raters for the construct validation portion of the study were not unaware of the children’s approximate ages while they were collecting data. This could have created a possible bias in scoring. Controlling for this factor is difficult, if not impossible, because children are assigned to specific classes on the basis of age, and their physical size and other behaviors provide cues regarding their ages. As a partial control, at the time of data collection the two raters were unaware of the fact that their scores would be reported in relationship to the children’s chronological ages. 226 Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/10/2015 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms March/April 2008, Volume 62, Number 2 Directions for Future Research Continued examination of the psychometric properties of the RKPPS is recommended. As changes are made in the information provided for those administering the RKPPS, new studies should be conducted. Specifically, interrater and test–retest agreement should be examined for children who are typically developing and for those with developmental delays. Children in both groups should represent varying geographic regions, cultures, and socioeconomic groups. In addition, further validation studies should be completed, and normative data should be collected. Conclusion Play is a challenging and important construct for occupational therapists to measure. The creation of an accurate picture of a child’s developmental play level and participation in play activities is integral to occupational therapy evaluation and intervention planning. The RKPPS shows promise for meeting this important need in that the current research suggests that two raters can score this measure with some consistency, and the scores on this measure progress developmentally. It is only through continued refinement and development of play assessments that the need for accurate and valid measurement of this key area of occupation will be met. s Acknowledgments The authors thank the teachers, parents, and students who made this project possible. References American Occupational Therapy Association. (2002). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56, 609–639. Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bergen, D. (1988). Stages of play development. In D. Bergen (Ed.), Play as a medium for learning and development: A handbook of theory and practice (pp. 49–66). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Educational. Bledsoe, N., & Shepherd, J. (1982). A study of reliability and validity of a Preschool Play Scale. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 36, 783–788. Bundy, A. (1989). A comparison of the play skills of normal boys with sensory integrative dysfunction. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 9(2), 84–100. Bundy, A. C. (1991). Play theory and sensory integration. In A. G. Fisher, E. A. Murray, & A. C. Bundy (Eds.), Sensory­integration theory and practice. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Couch, K. J. (1996). The use of the Preschool Play Scale in published research. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 16, 77–84. Couch, K., Deitz, J., & Kanny, E. (1998). The role of play in pediatric occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 52, 111–117. de Renne-Stephan, C. (1980). Imitation: A mechanism of play behavior. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34, 95–102. Dunn, W. (1989). Validity. In L. J. Miller (Ed.), Developing normreferenced standardized tests (pp. 149–168). Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press. Harrison, H., & Kielhofner, G. (1986). Examining reliability and validity of the Preschool Play Scale with handicapped children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 40, 167–173. Hurff, J. (1974). A play skills inventory. In M. Reily (Ed.), Play as exploratory learning (pp. 267–284). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Knox, S. (1974). A Play Scale. In M. Reilly (Ed.), Play as exploratory learning (pp. 247–266). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Knox, S. (1997). Development and current use of the Knox Preschool Play Scale. In L. D. Parham & L. S. Fazio (Eds.), Play in occupational therapy for children (pp. 35–51). St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Year Book. Knox, S. (2005). Play. In J. Case-Smith (Ed.), Occupational therapy for children (5th ed., pp. 571–586). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. Lifter, K. (1996). Assessing play skills. In M. McLean, D. B. Bailey, & M. Wolery (Eds.), Assessing infants and preschoolers with special needs (pp. 435–461). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Lunzer, E. (1959). Intellectual development in the play of young children. Educational Review, 11, 205–217. Michelman, S. (1971). The importance of creative play. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 25, 285–290. Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among pre-school children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 28, 1243–1269. Restall, G., & Magill-Evans, J. (1994). Play and preschool children with autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48, 113–120. Richmond, J. (1960). Behavior, occupation, and treatment of children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 14, 183–186. Robinson, A. (1977). Play: The arena for acquisition of rules for component behavior. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31, 248–253. Rubin, K., Fein, G., & Vandenberg, B. (1983). Play. In P. Mussin (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 694–774). New York: Wiley. Schaaf, R. C., & Mulrooney, L. L. (1989). Occupational therapy in early intervention: A family-centered approach. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43, 745–754. Smith, P. K., Takhvar, M., Gore, N., & Vollstedt, R. (1985). Play in young children: Problems of definition, categorization and measurement. Early Child Development and Care, 19, 24–41. Takata, N. (1969). The play history. American Journal of Occupa­ tional Therapy, 23, 314–318. Tinsley, H., & Weiss, D. (1975). Interrater reliability and agree­ ment of subjective judgments. Journal of Counseling Psychol­ ogy, 22, 358–376. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/10/2015 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms 227