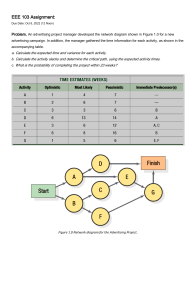

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1355-5855.htm APJML 21,1 Regulation of soft issues in advertising in Confucian societies: a comparative examination Zhihong Gao and Joe H. Kim 76 Rider University, Lawrenceville, New Jersey, USA Received December 2007 Revised April 2008 Accepted June 2008 Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics Vol. 21 No. 1, 2009 pp. 76-92 # Emerald Group Publishing Limited 1355-5855 DOI 10.1108/13555850910926254 Abstract Purpose – This paper sets out to examine the formal regulatory framework of controlling soft issues in six Confucian societies: China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea and Japan. It aims to investigate whether these societies adopt a similar approach to soft issues. Design/methodology/approach – The approach takes the form of historical analysis and textual analysis. Findings – Japan stands out among Confucian societies in regulating soft issues. The other five societies share considerable similarities, though each society’s approach ultimately reflects the entanglement and interaction between various economic, political, cultural and historical factors in the local context. Practical implications – For international advertisers, the ideological facet of advertising regulation in some Confucian societies spells unpredictable traps and troubles. Originality/value – Only a very few works have systematically examined soft issues in advertising, and few have focused on East Asia. The paper contributes to the literature by comparing how societies with similar cultural traditions regulate soft issues. Keywords Social factors, Advertising standards, Confucianism, East Asia Paper type General review Regulation of soft issues in advertising presents a serious challenge because it assumes a strong subjective dimension and is influenced by a spectrum of cultural, religious, political and economic forces (Boddewyn and Kunz, 1991). This is especially true today in the age of globalization, when interactions and conflicts between the world’s cultural and religious idea systems have intensified, and local forces increasingly turn to traditional cultural elements in their attempts to curb the side effects of globalization (Featherstone, 1990). In this context, soft issues in advertising are highly contested and a primary contributor to the flux of local regulation. Some specific soft issues, including alcohol and tobacco advertising, children’s advertising, sex-role stereotyping and socially controversial products, have been frequently studied (e.g. Shao and Hill, 1994; Taylor and Raymond, 2000). Yet, only a very few works have systematically examined the topic (Boddewyn, 1991; Boddewyn and Kunz, 1991). Moreover, broad international surveys in nature, these few works do not investigate the link between national regulations and the local ideological context. As a result, our understanding of the topic remains sketchy and superficial. To examine the ideological underpinning of advertising regulation, this paper applies the theory of new traditional economy and compares how six Confucian societies, including China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea and Japan, regulate soft issues in advertising. The concept of ‘‘new traditional economy’’, proposed by Rosser and Rosser (1998, 2005), describes economies which attempt to situate their capitalist development in a traditional socio-cultural framework as a way to address the social impact of Western-style modernization. The concept elegantly accommodates the conflicting trends of globalization and provides a dynamic perspective to understanding local regulation. The paper is organized into five sections. It first reviews the relevant literature on soft issues in advertising and then introduces the theory of new traditional economy. The third section discusses the general background of the six Confucian societies. The fourth section compares these societies’ approaches to soft issues. The last section concludes by exploring the implications of the findings for international advertising. Regulation of soft issues in advertising Regulating soft issues in advertising Advertising regulation encompasses three essential objectives: to encourage fair competition, to protect consumer interest and to maintain social norms. Considered hard issues, the first two objectives focus on ‘‘the deceptive character of advertisements as well as on the proper substantiation of advertising claims’’ (Boddewyn, 1991, p. 25). In contrast, the third objective deals with subjective, soft issues such as decency, taste, public opinion and social ethics (Boddewyn, 1991; Boddewyn and Kunz, 1991). Soft issues cover three general categories: 77 . offensive advertising content; . advertising of socially controversial products; and . exploitation of vulnerable groups (Boddewyn, 1991). The first category includes topics such as decency, sexism, sexuality, violence against women and objectification of women (Boddewyn, 1991, p. 26). Socially, controversial products can be either mentionable products such as cigarettes and alcohol, whose consumption is deemed undesirable or socially unmentionable products such as contraceptives and undergarments (Boddewyn, 1991; Wilson and West, 1981). Wilson and West (1981) further divide the unmentionable into two subcategories: those whose consumption is largely condemned by society (e.g. pornography and prostitution), and those whose consumption is acceptable but socially embarrassing (e.g. personal hygiene products and burial services). Finally, vulnerable groups may include children, senior citizens and the underprivileged (Boddewyn, 1991). Countries often adopt different approaches to soft issues in advertising (Boddewyn, 1991; Boddewyn and Kunz, 1991). In particular, many Western countries are wary of soft issues, usually leaving them to market and communitarian forces (Boddewyn, 1991). Shao and Hill (1994) further confirm that societies may share considerable common ground in defining what is offensive, yet diverge in their regulatory approach. However, the literature on the topic, scanty as it is, does not provide adequate insight to what accounts for the national differences. Advertising is arguably more than a market mechanism. In fact, it asserts a direct influence on social values, goals and ideals (Gustafson, 2001). Hence, advertising regulation extends beyond the economic sphere and acquires a strong ideological dimension. From this perspective, a better understanding of international advertising regulation must take the local ideological landscape into consideration – the theory of new traditional economy provides a dynamic framework for research in such a direction. The theory of new traditional economy In a series of articles, Rosser and Rosser (1998, 2005) propose the concept of ‘‘new traditional economy’’ to describe a ‘‘Third Way’’ between market capitalism and command socialism: ‘‘In the New Traditional Economy there is an effort to re-embed a modern or modernizing economy within a traditional socio-cultural framework, APJML 21,1 78 usually associated with a religion’’ (Rosser and Rosser, 2005, p. 562). According to the authors, the new traditional economy ‘‘often put[s] forward an idea of society as a whole being like a big family’’ and ‘‘claims to combine the old with the new, the individual with the collective, the ethical with the practical’’ (Rosser et al., 1999, p. 764). Islamic economics, neo-Confucian economics and Hindu economics are identified as prominent examples of the new traditional movements (Rosser and Rosser, 2005; Rosser, Rosser and Kramer, 1999). To a great extent, the concept of new traditional economy elegantly accommodates and summarizes the conflicting trends of globalization. Globalization is a complex and pluralistic process involving constant interactions and contestations between various idea systems at the global, regional and local level (Featherstone, 1990). Such a process is full of paradoxes. On the one hand, the idea of free market has spread worldwide and become a major engine for policy convergence in the economic arena (Hesmondhalgh, 2005). Thus, in promoting capitalist economic development, local regulation is compelled to embrace liberalistic legal regime and values, which favor ‘‘the adoption of impartial, rational self- over group identities and the assertion of universal laws over local customs’’ (Cheng and Rosett, 2003, p. 2). On the other hand, globalization brings to the foreground the sharp contradictions between the global economy and local cultures, and fuels cultural renaissance searching for self-definition and self-maintenance (Featherstone, 1990). In particular, the Western model of modernization is often perceived to have caused social problems such as loss of humanity, degradation of traditional norms and spiritual values and triumph of individualism over community interest (Song, 2002, p. 114). In this context, the new traditional movement emerges ‘‘partly as an ideological movement seeking to assert the political, economic, and cultural autonomy of non-Western nations and societies against the power and influence of US-style Western market capitalism’’ (Rosser and Rosser, 1998, p. 224). The concept of new traditional economy provides a dynamic and holistic perspective to understanding policy-making, including advertising regulation, at the local level by framing the discussion in the context of negotiations and compromises between conflicting idea systems. Rotzoll and Haefner (1996) propose that examining the implicit or explicit assumptions of classical liberalism will likely lead to compatible views of the role of regulation (p. 43). Free market ideas dictate that government regulation ‘‘must be carefully circumscribed and extremely limited’’ (Oliver, 1988, p. 6). In contrast, local traditional ideas may define the role of advertising differently and consequently see a greater need for regulating advertising. Confucian societies in East Asia provide a perfect case study to investigate how and to what extent conflicting idea systems negotiate with each other to shape the local regulatory landscape. Confucian teachings and Confucian societies According to Rozman (1991), Confucian societies include China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan and two Koreas. Empirical tests support the existence of such a cultural cluster (Gupta et al., 2002). The list does not include Vietnam, whose claim to membership of the group ‘‘is far more tenuous than that for any of the above areas’’ (Rozman, 1991, p. 7). This paper examines the Confucian societies identified above, with North Korea excluded due to scarcity of information. The six Asian societies all came under the influence of Confucianism in history, though significant differences exist between them in terms of the time, degree and social origin of their Confucianization (Collcutt, 1991; Duncan, 1998; Haboush, 1991; Rozman, 1991). Notably, the Confucian concern for morality, propriety, modesty, social harmony and human relationship, as well as its emphasis on moral education, has profoundly branded the cultural consciousness of these societies (Ching, 1977; Shryock, 1966; Wilhelm, 1931). The ideal Confucian government consists of men with superior moral qualities, who set good examples for the people, and who devote themselves to moral education (Dawson, 1981). Due to rounds of anti-Confucian tides and most importantly, the spread of Western liberal ideas, the influence of Confucianism in East Asia has declined in the last 100 years (Ching, 1977; Rozman 1991). Nevertheless, the Confucian idea system remains an influential, persistent aspect of East Asian societies. The Confucian societies have all experienced rapid economic growth in the last few decades, first led by Japan, then followed by the ‘‘Four Mini-Dragons’’, i.e. South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, and most recently, by mainland China. However, distinct from the Western liberalistic model, economic development in these societies takes on the form of ‘‘managed and negotiated capitalism’’ ( Jayasuriya, 1999, p. 2): the state, rather than adopting the minimal government intervention stance, has actively intervened in the economy as well as maintained close relations with businesses (Yoshimatsu, 2000). Rosser and Rosser (1998) call the East Asian capitalism ‘‘neo-Confucianism’’, a major rising new traditional economic system that supports authoritarian state structures and familistic groupist attitudes. The recent history of the Confucian societies confirms that Confucian ideas have been actively exploited by their governments for the purpose of state building. For instance, South Korea, in its conquest for economic development, has combined nationalist ideals and Confucianism to invent its own work ethics (Kim and Park, 2003). President Park Chung-hee even established the Academy of Korean studies to study Confucianism as a component of Korea’s valuable spiritual culture (Hahm, 2003, p. 277). Similarly, the leaders of Singapore have been extolling Confucianism-based ‘‘Asian values’’ in their implementation of a ‘‘soft’’ authoritarian regime (Kuo, 1998; Zakaria, 1994). Hong Kong has witnessed depoliticized, shallow discourses on good citizenship and community building by both the colonial and Special Administrative Region governments for the purpose of maintaining social order (Lam, 2005), and Confucian values serve as a primary source for government guidelines on moral education (Cheng, 2004). Lee Teng-Hui, Taiwan’s first popularly elected leader, also advocates the concept of ‘‘Confucian democracy’’ (Lee, 1999), and the Taiwan government has launched its project of nation-building (Hughes and Stone, 1999). The Chinese government, in its struggle for legitimacy, has been promoting a broad concept of social ethics based on Confucian values to build ‘‘a harmonious society’’ (He, 2005). Because of these government rhetoric and initiatives, Confucian thinking has been experiencing a discernible revival since the 1980s (Tu, 1998). This revival is further facilitated by two additional factors. First, Confucian values have often been credited – at least partially – for the economic miracles in East Asia (e.g. Jacobs et al., 1995; Lam, 2003; Ornatowski, 1996; Romar, 2002; Zhu, 2000). At the same time, social issues related to industrialization, modernization and globalization foster introspection and a return to traditional ideas for solutions and inspirations (Rozman, 1991; Song, 2002). According to Song (2002), the modern Western ethic entails a liberal individualist tradition which emphasizes the private interests of individuals, whereas the Confucian ethic values the harmony and welfare of the entire community above the interests of individuals (p. 118). In the case of advertising regulation, the liberal tradition gives primary consideration to advertisers’ rights to freedom of commercial speech and thus is reluctant to regulate soft issues in advertising. In contrast, the communitarian focus Regulation of soft issues in advertising 79 APJML 21,1 80 of the Confucian ethic, combined with its strong concern for morality and the tradition of moral education, suggests that the Confucian societies, unlike their Western counterparts, may be more earnest in regulating soft issues in advertising. While sharing the tradition of Confucianism, the six societies have experienced very distinct trajectories of development in recent times and thus differ on a number of dimensions (Table I). Notably, they are at different stages of economic development, and their people enjoy varied degrees of political freedom. These economic and political factors may impact advertising regulation in these societies and lead to some tangible differences between them. On the other hand, the new traditional nature of these economies and their shared cultural heritage may also foster regulatory similarities. The next section will explore the differences and similarities in their approach to soft issues in advertising. Confucian societies’ approaches to soft issues Addressing government advertising regulation, Gao (2005) emphasizes the importance of comparing the general regulatory structures and guidelines. When it comes to soft issues in advertising, Boddewyn (1991) identifies three major categories: offensive content, socially controversial products and vulnerable groups. Combining elements from these two frameworks, this section compares the formal regulation of soft issues in the six Confucian societies on five aspects: . the general structure, including the form of regulation, major agencies in charge, and primary laws and codes involved; . regulatory guidelines on soft issues; . provisions on offensive advertising content; . provisions on advertising for unmentionable products such as sexually transmitted diseases, personal hygiene products, contraceptives, gambling, pornographic materials, escort or similar services and funeral services; and . provisions on advertising to children. Since advertising for cigarettes, alcohol and pharmaceuticals encounters a similar degree of legal restrictions across markets due to national and international health initiatives (Shao and Hill, 1994), these products are not included in the comparison. The data consist of advertising laws, regulations and self-regulatory codes currently in effect in these societies. The general structure The primary form of advertising regulation varies across the Confucian societies, though they all have either laws or self-regulatory codes to govern soft issues (Table II). The government plays a predominant role in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan – Hong Kong’s self-regulatory codes are issued and enforced by the government. Largely consistent with their civil law tradition, China, Taiwan and South Korea have more elaborate advertising laws than other societies. Singapore does not have codified advertising laws other than Indecent Advertisements Act, which bans advertisements for treatments of venereal diseases. The Singapore Code of Advertising Practice provides detailed and elaborate provisions on advertising practices and is enforced by the Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore (ASAS), an advisory council to the Consumers Association of Singapore. With representatives from the government, industry and consumer organizations, the ASAS is empowered to 3.5 (partly free) Free market capitalism $36,800 1.28 (1) free Communist republic One-party system Civil law 6.5 (not free) Market-oriented socialism $6,200 3.34 (111) mostly unfree Government typea Political systema Legal systema Political freedom index 2005b Economic systema Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (PPP 2005 est.)a Economic freedom 2006 scores (overall rank)c 2.37 (37) mostly free $26,700 Free market capitalism 1.5 (free) Civil law 1.56 (2) free $29,700 Free market capitalism 4.5 (partly free) English common law Multi-party system 2.63 (45) mostly free $20,300 Free market capitalism 1.5 (free) Hybrid of European civil law and AngloAmerican law Multi-party system Republic Parliamentary republic Democratic regime with elected president Multi-party system Japanese colony 1905-1945 South Korea British colony 1819-1963 Singapore Japanese colony 1895-1945 Taiwan Notes: aCentral Intelligence Agency (2006); bFreedom House (2005); cThe Heritage Foundation (2006) English common law Multi-party system Special administrative region of China British colony 1841-1997a Western influence in coastal areas 1840-1945 Colonial historya Hong Kong China Societies 2.26 (27) mostly free $30,400 Free market capitalism 1.5 (free) European civil law, with EnglishAmerican influence Multi-party system Constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary government Japan Regulation of soft issues in advertising 81 Social, political and economic comparison of Confucian societies Table I. Government Government Government Self-regulation Hybrid Self-regulation China Hong Kong Taiwan Singapore South Korea Japan Table II. Structural dimensions of regulating decency issues in advertising in Confucian societies Form of regulation Japan advertising review organization Korean broadcasting commission, KARB Advertising standards authority Government information office Broadcasting authority State administration of industry and commerce Major regulatory agencies None Regulations Concerning Deliberation on Broadcasts, Regulations Concerning Deliberation on Advertising Broadcast, The Youth Protection Law, Regulations of Advertising [in Publications] Indecent Advertisements Act Radio and Television Act, Standards on Examining the Content of Radio and Television Advertisements, Standards on the Production and Broadcast of Advertisements on Cable Television, Detailed Methods on the Implementation of Medicine Law Undesirable Medical Advertisements Ordinance Advertising Law, Regulations on the Administration of Advertising, Methods on the Administration of Advertising for Medicine, Provisional Rules on the Administration of Radio and Television Advertisements Primary statutes on decency issues in advertising The Japan Advertising Agencies Association Corporation Code of Ethics None The Singapore Code of Advertising Practice None Generic Code of Practice on Television Advertising Standards, Generic Code of Practice on Radio Advertising Standards Self-Discipline Code on Spiritual Civilization in Advertising Self-regulatory codes 82 Societies APJML 21,1 have an advertisement amended, withheld or withdrawn, as well as rule on disputes between advertising businesses (the Consumers Association of Singapore, 2006). Japan does not have codified laws regulating soft issues. Its advertising laws such as Consumer Protection Fundamental Act and Act Against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Presentations focus on deceptive advertising. Compared to its Singapore counterpart, the Japanese Advertising Review Organization (JARO), the primary selfregulatory body in Japan, is much less powerful, as it cannot force the parties involved to abide by its decisions. The JARO follows a few brief principles in its review and deals primarily with misleading and unfair advertising (The Japanese Advertising Review Organization, 2006). Advertising regulation in South Korea takes a hybrid form: a series of advertising statutes exist, but the government entrusts their enforcement to a civilian selfregulatory body, Korea Advertising Review Board (KARB). The KARB serves as a clearinghouse for broadcast advertisements and monitors advertisements published in the print media for violations. It has the power to hand out and enforce decisions such as caution, warning, correction, stoppage or apology advertisement (The Korea Advertising Review Board, 2006). Guidelines on soft issues The Confucian societies fall into two camps when it comes to guidelines on soft issues (Table III). Both Hong Kong and Japan have very brief guidelines. In contrast, China, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea all specify guidelines that go far beyond the general principle that advertising shall respect prevailing social norms and values. Notably, they all require advertisements to respect national pride and dignity as well as help maintain social unity and harmony. Singapore and South Korea’s guidelines stand out as particularly elaborate. The Singapore Code of Advertising Practice, a self-regulatory code, lists the shared values of the society, including nation before community and society before self; family as the basic unit of society; community support and respect for the individual; consensus, not conflict; and racial and religious harmony (The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore, 2003, p. I.ii.1.4). It also enumerates Singapore’s family values, including love, care and concern, mutual respect, filial responsibility, commitment and communication (The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore, 2003, p. I.ii.1.5). It further explains what these values mean for advertising content (The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore, 2003, p. II. 8.-9). For instance, advertisements should not ‘‘encourage inconsiderate and disrespectful conduct amongst family members’’ or ‘‘discourage the responsibilities of honouring, supporting and providing for one’s parents and grandparents in their old age’’ (The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore, 2003, p. II. 9. 2.3). South Korea’s Regulations Concerning Deliberation on Broadcasts defines the public responsibility of broadcasting in terms of nation building and harmonious social order (Korean Broadcasting Commission, 2005a, Article 7). The law allocates a section to ‘‘Level of Morality’’, which covers topics such as morality, respect for life, maintenance of dignity, wholesome life ethos and social integration in its first five articles (Korean Broadcasting Commission, 2005a, Chapter II section 4). Both Regulations Concerning Deliberation on Advertising Broadcast and Regulations of Advertising [in Publications] give emphasis to the ‘‘dignity of the nation’’ and require advertisements to respect national symbols, cultural inheritances and the public’s pride (Korean Broadcasting Commission, 2005b, Article 10; Korean Broadcasting Commission, 2005c, Article 25). Regulation of soft issues in advertising 83 Beneficial to the moral health of the people Shall conform to social morality and professional ethics General principles Social norms and values Shall protect national dignity and interest, promote Chinese national spirit and culture and strengthen national confidence and pride Social unity Shall contribute to and harmony national unity and ethnical harmony Shall not be detrimental to national interests or ethnic dignity Shall not disrupt public order Clean, not vulgar Shall not adversely affect good social customs Taiwanc Shall be pursuant to social manners and customs; must not work against sound social order or good customs of the society Shall not harm social morality, shall contribute to the formation of correct values and norms and to the enhancement of social ethics and public etiquette Should not subvert the shared social and family values, should not condone rude and inconsiderate behavior, should not downplay the importance of having a caring and compassionate attitude for the less fortunate Should not promote a lifestyle detrimental to family values, should not subvert family values Should not downplay patriotism, distort the perception of Singaporeans and the quality of life in Singapore or discredit Singapore as a country Should not subvert racial and religious harmony or downplay the importance of national unity, should not encourage confrontational approach or fuel conflicts Shall help develop a harmonious national culture, shall not aggravate conflicts Shall respect the public’s pride and emotion, shall not harm national dignity and pride Shall respect the sanctity of marriage and sound family values Decency Japanf Quality standards South Koreae Decency Singapored Notes: aChina Advertising Association (1997); The National People’s Congress of China (1994); bHong Kong Broadcasting Authority (2004); cTaiwan Executive Council (1999); dThe Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore (2003); eKorean Broadcasting Commission (2005a, 2005b, 2005c); fThe Japanese Advertising Review Organization (2006) National spirit, dignity and pride Clean and in good taste Shall not be objectionable to a substantial and responsible section of the community Hong Kongb 84 Family values Chinaa Table III. Guidelines on taste and decency in advertising in Confucian societies Guidelines APJML 21,1 A self-claimed socialist country, China defines its guidelines on decency under the ideological umbrella of socialist ethics and spiritual civilization (The National People’s Congress of China, 1994). The Self-Discipline Code on Spiritual Civilization in Advertising, issued by China Advertising Association (1997) and approved by China State Administration of Industry and Commerce, requires that advertising encourage socialist ethics, show respect for traditional culture and Chinese language, defend national unity and ethnical solidarity and cultivate in people kindness, truthfulness and love for the country and socialism. Provisions on offensive advertising content Except for the ‘‘clean and in good taste’’ principle, Hong Kong’s advertising regulations do not contain provisions on specific advertising appeals. The same can be said about Japan’s self-regulatory codes, which only suggest that ‘‘advertising must esteem grace and dignity to contribute to the establishment of sound and healthy life of the people’’ (Japan Advertising Agencies Association, 2006). In comparison, China, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea all ban advertising that plays on fear, violence, superstition, obscenity and promiscuity. In defining its quality standards, South Korea’s Regulations Concerning Deliberation on Advertising Broadcast provides a detailed list of offensive expressions: . expressions promoting violence, crime or other anti-social acts; or other expressions that belittles life; . expressions promoting excessive fear or hatred; . expressions promoting excessive nudity, obscenity or lewdness; . excessively vulgar expressions harmful to public morality; and . sexually degrading or prejudicial expressions. (Korean Broadcasting Commission, 2005b, Article 5). Exaggerated and/or superlative claims are also banned in these four societies, though the Singapore code states that it ‘‘places no constraint upon the free expression of opinion’’ (The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore, 2003, p. III. 4.1). Provisions on advertising for unmentionables Advertising for unmentionable products faces varied degrees of regulation in the Confucian societies (Table IV). Japan has few provisions on the subject, whereas China, Hong Kong and South Korea have rules across a range of products. Interestingly, except for Japan, all ban advertisements for treatments of venereal diseases. Advertising for personal products such as feminine napkins is allowed in every society, though closely regulated in China, Hong Kong and South Korea. Only China and South Korea ban commercial advertising for contraceptives. Advertising for gambling, services of sexual nature (such as escort services, massage parlors sex phone lines, etc.) and advertising for pornographic materials is prohibited in three of the six societies. Provisions on advertising to children The International Code of Advertising Practice, the world business community’s expression of its social responsibility in respect of advertising, provides two principles concerning advertising to children and young people, i.e. the ‘‘inexperience and credulity’’ principle and the ‘‘avoidance of harm’’ principle (International Chamber of Regulation of soft issues in advertising 85 Banned Banned Gambling Services of sexual nature Pornographic materials Should be restrained and discreet; cannot be shown between 4:00-8:00 p.m. Banned except for lotteries authorized by the government, horse racing and football Banned Banned Ads for common betting banned Ads for pharmaceutical device for gynecological use, venereal diseases or genitals banned Ads for treatment of venereal disease, nervous debility or other complaint or infirmity arising from or relating to sexual intercourse, and breast enlargement banned Prohibited Prohibited Prohibited Shall not be voluptuous or obscene or use any expressions or pictures emphasizing sexual organs, sexual drive or body parts Prohibited South Koreae Singapored Japan Notes: aChina Advertising Association (1997), The National People’s Congress of China (1994); bHong Kong Broadcasting Authority (2004); cTaiwan Executive Council (1999); dThe Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore (2003); eKorean Broadcasting Commission (2005a, 2005b, 2005c) Banned Banned except for public service ads Contraceptives Personal products (feminine napkins, undergarments, toilet papers, deodorants, etc.) Ads for medicines Ads for treatment of related to sexual abortion, miscarriage, functions banned pregnancy tests, alcohol or drug addiction and venereal disease banned; promotion of sexual virility, desire or fertility or the restoration of lost youth banned Should be restrained and discreet, in good taste and not overly graphic, presented with care and sensitivity; should not cause embarrassment and/ or offense to the viewer Ads for treatment of venereal diseases, sexual impotence, and drug addiction banned; ads for hemorrhoid and athlete’s-foot ointment banned during meal times Banned during meal times Medicinal/medical products and services Taiwanc Hong Kongb Table IV. Provisions on advertising for offensive products in Confucian societies Chinaa 86 Products APJML 21,1 Commerce, 1997). Under the ‘‘Social Value’’ subparagraph of the latter, the Code demands that ‘‘advertisements should not undermine the authority, responsibility, judgment or tastes of parents, taking into account the current social values’’ (International Chamber of Commerce, 1997). Such a provision recognizes that advertising to children encompasses a dimension of moral education, though the specific values taught are culturally bound. Japan’s self-regulatory codes require that advertisements ‘‘be made in consideration of its impact on youth and children’’ (Japan Advertising Review Organization, 2006), but do not elaborate on the topic. In comparison, laws and codes in other Confucian societies all go to great length in establishing the boundaries for advertising to children. In particular, they not only include clauses on children’s credulity and avoidance of harm but also take on a strong moral dimension. For instance, Hong Kong’s Generic Code of Practice on Television Advertising Standards stipulates that ‘‘children seen in advertisements should be presented in such a manner as to set a good example of behaviour and manners’’ (Hong Kong Broadcasting Authority, 2005). Taiwan’s Standards on the Production and Broadcast of Advertisements on Cable Television prohibits advertisements from asserting an adverse effect on established moral customs such as respect for parents and teachers, influencing children to form bad habits, or encouraging greedy, acquisitive mentality in children (Taiwan Executive Council, 1999). Similarly, children in advertisements in Singapore cannot be shown to be disrespectful to adults, nor can advertisements actively encourage children to eat excessively or make excessive purchases (The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore, 2003). Chinese advertising regulations also call on advertisers to contribute to the formation of good ethics and morality in children – advertisements should feature children and adults with good morality and manners, and should not show children behave in disrespectful, unfriendly or uncivilized ways (China Advertising Association, 1997; China State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, 2004). Striving to help children and youth to form good characters, the relevant laws in South Korea stipulate that advertisements shall not use expressions harmful to the character, emotion or values of children or juveniles (Korean Broadcasting Commission, 2005b). Meanwhile, Korean statutes go beyond advertising content in their protection of children. The country’s Youth Protection Law poses expansive restrictions on advertisements deemed to be ‘‘media materials harmful to juveniles’’, so that children and youth will not gain access to such materials (Korea Juvenile Protection Committee, 2002). For instance, the time period between 13:00 and 22:00 and in the case of holidays and school breaks, 10:00-22:00 are designated as ‘‘Juvenile Viewing Time Zone’’, during which media materials harmful to children should not be broadcast (Korea Broadcasting Commission, 2005a; Korea Juvenile Protection Committee, 2002). Discussion Japan stands out among the Confucian societies in that it has no elaborate laws and codes on soft issues, and its self-regulatory body has very limited power. Much like the United States, the country relies on the market, community and self discipline rather than formal regulation. For instance, advertising for condoms, female hygiene products and sexual diseases are socially restricted in Japan (Shao and Hill, 1994). Two plausible reasons account for why the Japanese approach differs from those of other Confucian societies. First, compared to its Asian neighbors, Japan has a much longer history of capitalist development. The Meiji Restoration ushered in the Japanese economic modernization characterized by earnest introduction of liberalistic ideas, modern Regulation of soft issues in advertising 87 APJML 21,1 88 technologies and Western-style institutions during the second-half of the nineteenth century (Hoston, 1992), almost 100 years before the rest of the region began its industrialization. The free market ideology fits well into the Japanese indigenous political culture, which exhibits a strong tendency to emphasize guidance by the state rather than direct regulation in relation to some transcending principles (Eisenstadt, 1995). Second, it is also possible that, given the society’s strong emphasis on conformity and self-discipline (Triandis, 1994), the Japanese have internalized the traditional values to such a degree that explicit laws become unnecessary in dictating business ethics. China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea share considerable similarities in their handling of soft issues. First, they all follow a centralized approach. In the case of China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, the government plays the ultimate central role. The center of the South Korean system consists of two pieces, government legislation and a self-regulatory body entrusted by the government to enforce laws. Though the Singapore system is self-regulatory, the ASAS enjoys the status of a government agency in its power to rule against violations. These formal frameworks confirm the tradition of managed capitalism and close co-operation between the state and business in these societies (Jayasuriya, 1999; Yoshimatsu, 2000). In addition, advertising regulations in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea all explicitly deal with soft issues, though to a different degree. Their guidelines that emphasize morality, family and harmony are reminiscent of the core Confucian values, and those promoting national pride, unity and dignity echo nationalistic sentiments embedded in these societies’ nation building projects. In prohibiting various offensive claims and banning advertising for a range of offensive products, they manifest a strong moral conservatism, reflecting the new traditional nature of their economies (Rosser et al., 1999). Meanwhile, their regulation of children’s advertising invariably assumes a dimension of moral education, as advertising is considered as a critical tool to teach children about moral values such as respect for adults, good manners and modesty. Confucian influence alone cannot fully explain these similarities. Historical and political forces also play a salient role here. Notably, all these five societies experienced some form of colonialism in the twentieth century followed by independence and authoritarian politics except in the case of Hong Kong, which was controlled by the British until 1997. As Geertz (2000) points out, the transition from colonies to states requires a radical change in the task of nationalist ideologizing: instead of anticolonialism rhetoric, it consists in defining a collective subject and an experiential ‘‘we’’ from whose will the activities of government seem spontaneously to flow – traditional cultural elements provide a natural fountain for this new ideology (p. 240). This is exactly the case in East Asia, where Confucian values were integrated into the redefinition of nationalism through nation-building projects, and authoritarian politics facilitated the process by tightly controlling social communications, including advertising. The legacy of this new nationalist ideology persists today, even though these societies have experienced rapid economic development and, in the case of Taiwan and South Korea, democratization. Conclusion All considered neo-Confucian economies (Rosser and Rosser, 1998), the six Confucian societies do not implement the same approach in regulating soft issues in advertising. Japan, a well-developed economy with a long history of capitalist development, seems to have opted for a liberalistic approach in its advertising regulation. In comparison, advertising regulation by the other Confucian societies all manifest characteristics of managed capitalism. Notably, the government or quasi-government agencies in these societies play an active, central role in regulating soft issues, and their advertising provisions often reveal strong moral conservatism. The regulations of China, Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore further indicate a paternalistic stance on the part of these governments, who perceive advertising as a social tool to propagandize their definitions of good and moral life. For international advertisers, the strong ideological dimension of advertising regulation in some Confucian societies spells serious challenges. For instance, advertisements that contain visuals or headlines deemed alien to the local culture have been banned in Singapore (Frith, 2003, p. 46). In China, the regulator asked McDonald’s to pull its commercial which depicted a Chinese man on his knees begging for a discount because some consumers complained that the commercial was an indignity (‘‘McDonald’s Pulls’’, 2005). These examples suggest that it may not be adequate for Western professionals to rely on their own understanding of soft issues when managing international campaigns. Rather, they need to sensitize themselves to the nuances and idiosyncrasies of local regulations. More importantly, advertising scholars and practitioners should adopt a more holistic view of international advertising regulation. To this end, the concept of new traditional economy provides a valuable entry point to dissecting and understanding the ideological underpinning of local regulation. In the mirror of their regulations, we see how societies handle differently the delicate balance between the free market and tradition, between the universal trends and the local customs, and between individual freedom and collective interest. Admittedly, the proliferation of global media and especially the internet increasingly exposes people in East Asia to advertisements from the West and thus seriously challenges the enforcement of local regulations. However, it is a double-edged sword. It may gradually lead to a more tolerant attitude and consequently loosened control of soft issues in the region. It is also possible that exposure to undesirable advertising from abroad heightens these societies’ sense of cultural identity and strengthens their resolve to propagandize their ideas of good and moral life through tightened regulation. For future research, it would be interesting to investigate whether a discourse on the freedom of commercial speech exists in the Confucian societies, and if yes, to what extent it influences local advertising law making. Advertising regulation in these societies can be further studied from the perspective of ethical dimensions such as idealism vs pragmatism and universalism vs relativism (Treise et al., 1994): where are Confucian ethics and liberalistic ethics located on these dimensions, and are there common grounds between them for reconciliation? These two research directions, which this paper does not explore due to space constraints, hold promises for much deeper understanding of policy-making in the Confucian societies as well as advertising regulation in general. References Boddewyn, J.J. (1991), ‘‘Controlling sex and decency in advertising around the world’’, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 25-35. Boddewyn, J.J. and Kunz, H. (1991), ‘‘Sex and decency issues in advertising: general and international dimensions’’, Business Horizons, Vol. 34 No. 5, pp. 13-22. Regulation of soft issues in advertising 89 APJML 21,1 90 Central Intelligence Agency of United States (2006), ‘‘World factbook’’, available at: www.cia.gov/ cia/publications/factbook/geos/tw.html (accessed on 11 March 2006). Cheng, L. and Rosett, A. (2003), ‘‘Finding a role for law in Asian development’’, in Rosett, A., Cheng, L. and Woo, M.Y.K. (Eds), East Asian Law – Universal Norms and Local Cultures, RoutledgeCurzon, London, pp. 1-21. Cheng, R.H.M. (2004), ‘‘Moral education in Hong Kong: Confucian-parental, christian-religious and liberal-civic influences’’, Journal of Moral Education, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 533-51. China Advertising Association (1997), The Self-Discipline Code on Spiritual Civilization in Advertising, Beijing. China State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (2004), Provisional Rules on the Administration of Radio and Television Advertisements, Beijing. Ching, J. (1977), Confucianism and Christianity, Kodansha International, Tokyo. Collcutt, M. (1991), ‘‘The legacy of Confucianism in Japan’’, in Rozman, G. ( Ed.), The East Asian Region: Confucian Heritage and its Modern Adaptation, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 111-56. Dawson, R. (1981), Confucius, Hill and Wang, New York, NY. Duncan, J. (1998), ‘‘The Korean adoption of neo-Confucianism: the social context’’, in Slot, W.H. and Devos, G.A. (Eds.), Confucianism and the Family, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, pp. 75-90. Eisenstadt, S.N. (1995), ‘‘The Japanese historical experience – comparative and analytical dimensions’’, Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 148-75. Featherstone, M. (1990), Global Culture: Nationalism, Globalization and Modernity, Sage, London. Freedom House (2005), Freedom in the World, Washington, DC. Frith, K.T. (2003), ‘‘Advertising and the homogenization of cultures: perspectives from ASEAN’’, Asian Journal of Communication, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 37-54. Gao, Z. (2005), ‘‘Harmonious regional advertising regulation? a comparative examination of government advertising regulation in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan’’, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 34 No. 3, pp. 75-88. Geertz, C. (2000), The Interpretation of Cultures, Basic Books, New York, NY. Gupta, V., Hanges, P.J. and Dorfman, P. (2002), ‘‘Cultural clusters: methodology and findings’’, Journal of World Business, Vol. 37, pp. 11-15. Gustafson, A. (2001), ‘‘Advertising’s impact on morality in society: influencing habits and desires of consumers’’, Business and Society Review, Vol. 106 No. 3, pp. 201-23. Haboush, J.H.K. (1998), ‘‘The Confucianization of Korean society’’, in Rozman, G. (Ed.), The East Asian Region: Confucian Heritage and its Modern Adaptation, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 84-110. Hahm, C. (2003), ‘‘Law, culture, and the politics of Confucianism’’, Columbia Journal of Asian Law, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 254-301. He, Z. (2005), ‘‘A look at law making from the perspective of building a harmonious society (in Chinese)’’, The People’s Daily, 20 April, p. 1. Hesmondhalgh, D. (2005), ‘‘Media and cultural policy as public policy’’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 95-109. Hong Kong Broadcasting Authority (2004), Generic Code of Practice on Television Advertising Standards, Hong Kong. Hoston, G.A. (1992), ‘‘The state, modernity, and the fate of liberalism in prewar Japan’’, Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 51 No. 2, pp. 287-316. Hughes, C. and Stone, R. (1999), ‘‘Nation-building and curriculum reform in Hong Kong and Taiwan’’, The China Quarterly, No. 160, pp. 977-91. Jacobs, L., Gao, G. and Herbig, P. (1995), ‘‘Confucian roots in China: a force for today’s business’’, Management Decision, Vol. 33 No. 10, pp. 29-34. Japan Advertising Agencies Association (2006), Code of Ethics, Tokyo. Jayasuriya, K. (1999), ‘‘Introduction: a framework for the analysis of legal institutions in East Asia’’, in Jayasuriya, K. (Ed.), Law, Capitalism and Power in Asia: The Rule of Law and Legal Institutions, Routledge, London, pp. 1-27. International Chamber of Commerce (1997), International Code of Advertising Practice, Paris. Kim, A.E. and Park, G. (2003), ‘‘Nationalism, Confucianism, work ethics and industrialization in South Korea’’, Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 33 No. 1, pp. 37-49. Korea Advertising Review Board (2006). ‘‘How KARB works’’, available at: http://karb.or.kr/e/ how/how01.html (accessed 16 March 2006). Korean Broadcasting Commission (2005a), Regulations Concerning Deliberation on Broadcasts (in Korean), Seoul. Korean Broadcasting Commission (2005b), Regulations Concerning Deliberation on Advertising Broadcast (in Korean), Seoul. Korean Broadcasting Commission (2005c), Regulations of Advertising in Publications (in Korean), Seoul. Korea Juvenile Protection Committee (2002), South Korean Youth Protection Law, Seoul. Kuo, E.C. (1998), ‘‘Confucianism and the Chinese family in Singapore: continuities and changes’’, in Slot, W.H. and Devos, G.A. (Eds), Confucianism and the Family, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, pp. 231-48. Lam, K.J. (2003), ‘‘Confucian business ethics and the economy’’, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 43 Nos. 1/2, pp. 153-62. Lam, W. (2005), ‘‘Depoliticization, citizenship, and the politics of community in Hong Kong’’, Citizenship Studies, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 309-22. Lee, T.H. (1999), ‘‘Confucian democracy: modernization, culture, and the state in East Asia’’, Harvard International Review, Vol. 21 No.4, pp. 16-18. Nation’s Restaurant News (2005), ‘‘McDonald’s pulls TV ad in China after complaints’’, Nation’s Restaurant News, Vol. 39 No. 28, p. 82. Oliver, D. (1988), ‘‘Who should regulate advertising, and why?’’, International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 7, pp. 1-9. Ornatowski, G.K. (1996), ‘‘Confucian ethics and economic development: a study of the adaptation of Confucian values to modern Japanese economic ideology and institutions’’, Journal of Socio-Economics, Vol. 25 No. 5, pp. 571-90. Romar, E.J. (2002), ‘‘Virtue is good business: Confucianism as a practical business ethic’’, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 38 Nos. 1-2, pp. 119-31. Rosser, B.J. and Rosser, M.V. (1998), ‘‘Islamic and neo-confucian perspectives on the new traditional economy’’, Eastern Economic Journal, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 217-27. Rosser, B.J. and Rosser, M.V. (2005), ‘‘The transition between the old and new traditional economies in India’’, Comparative Economic Studies, Vol. 47, pp. 561-78. Rosser, M.V., Rosser, B.J. and Kramer, K.L. Jr (1999), ‘‘The new traditional economy: a new perspective for comparative economics?’’, International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 26 No. 6, pp. 763-78. Rotzoll, K.B. and Haefner, J.E. (1996), Advertising in Contemporary Society: Perspectives toward Understanding, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL. Regulation of soft issues in advertising 91 APJML 21,1 92 Rozman, G. (1991), ‘‘The East Asian region in comparative perspective’’, in Rozman, G. (Ed.), The East Asian Region: Confucian Heritage and its Modern Adaptation, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 3-44. Shao, A.T. and Hill, J.S. (1994), ‘‘Global television advertising restrictions: the case of socially sensitive products’’, International Journal of Advertising, Vol. 13, pp. 347-66. Shryock, J.K. (1966), The Origin and Development of the State Cult of Confucius, Paragon Book Reprint Corp., New York, NY. Song, Y. (2002), ‘‘Crisis of cultural identity in East Asia: on the meaning of Confucian ethics in the age of globalisation’’, Asian Philosophy, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 109-25. Taiwan Executive Council (1999), Standards on the Production and Broadcast of Advertisements on Cable Television (in Chinese), Taipei. Taylor, C.R. and Raymond, M.A. (2000), ‘‘An analysis of product category restrictions in advertising in four major East Asian markets’’, International Marketing Review, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 287-86. The Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore (2003), Singapore Code of Advertising Practice, Singapore. The Consumers Association of Singapore (2006), ‘‘About ASAS’’, available at: www.case.org.sg/ asas1.htm (accessed on 11 March 2006). The Heritage Foundation (2006), 2006 Index of Economic Freedom, Washington, DC. The Japanese Advertising Review Organization (2006), ‘‘The history and current activities of the Japan Advertising Review Organization, Inc.’’, available at: www.jftc.go.jp/eacpf/05/ jicatext/sep16_2.pdf (last accessed November 19 2008). The National People’s Congress of China (1994), Advertising Law (in Chinese), Beijing. Treise, D., Weigold, M.F., Conna, J. and Garrison, H. (1994), ‘‘Ethics in advertising: ideological correlates of consumer perceptions’’, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 59-69. Triandis, H.C. (1994), Culture and Social Behavior, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Tu, W.M. (1998), ‘‘Confucius and Confucianism’’, in Slot, W.H. and Devos, G.A. (Eds), Confucianism and the Family, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, pp. 3-37. Wilhelm, R. (1931), Confucius and Confucianism, (translated by George H. Danton and Annina Periam Danton), Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York, NY. Wilson, A. and West, C. (1981), ‘‘The marketing of ‘unmentionables’’’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 59 No. 1, pp. 91-102. Yoshimatsu, H. (2000), ‘‘State-market relations in East Asia and institution-building in the AsiaPacific’’, East Asia, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 5-33. Zakaria, F. (1994), ‘‘Culture is destiny: a conversation with Lee Kuan Yew’’, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 73 No. 2, pp. 109-26. Zhu, Z. (2000), ‘‘Cultural change and economic performance: in interactionistic perspective’’, The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 109-26. Corresponding author Zhihong Gao can be contacted at: zgao@rider.edu To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.