HISTORY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE I

Main goals

To introduce you to the concepts and techniques of historical linguistics, the

discipline that studies language change.

To show why and how languages change and the main types of language change

that occur in languages.

To show the evolution that English has undergone throughout history.

Course outline

1) General survey of the subject: Historical linguistics: its objectives

2) Language relationships

3) The process of language change

4) Sound change

5) Grammatical change

6) Semantic change

7) Word-formation

8) The historical background of the English language: Loan words

9) The evolution of the English language.

1. Historical linguistics: main goals

Explain synchronic irregularities

Identify and explain language relationships cross-languages similarities

- How differences appeared

- Reconstruct the ancestor language

How and why languages change.

On the one hand, to understand the present state of a language we have to focus on its

irregularities. On the other hand, it is important to understand the relationship of a

given language with other languages: English, for example, is related to languages as

geographically distant as Sanskrit or Persian.

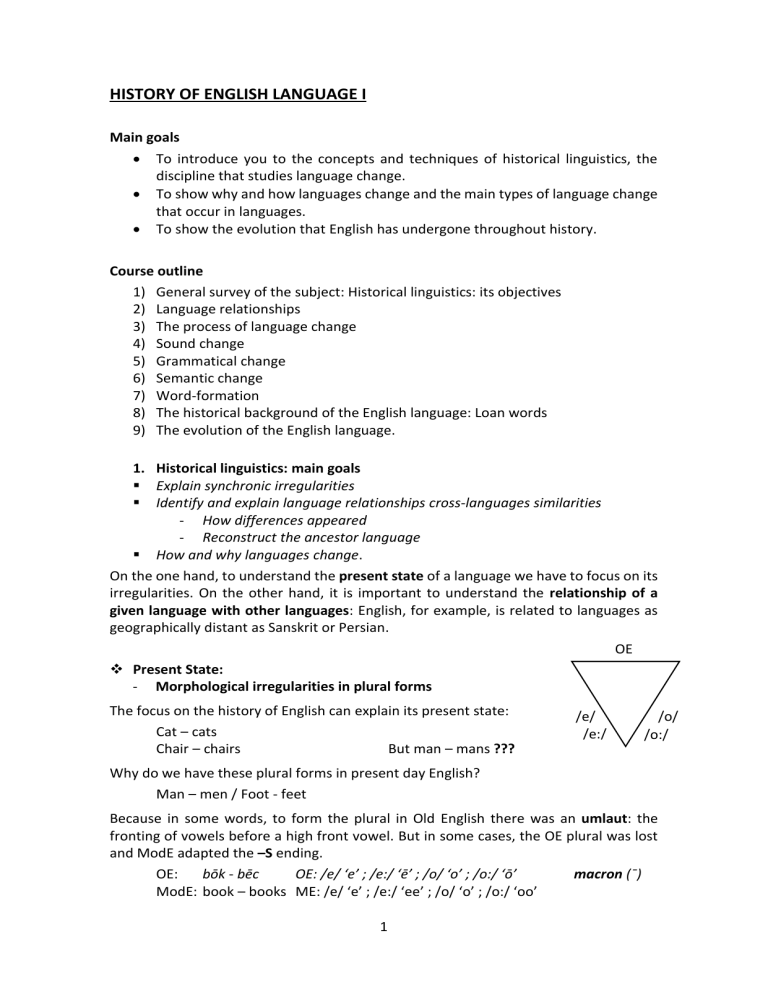

OE

Present State:

- Morphological irregularities in plural forms

The focus on the history of English can explain its present state:

Cat – cats

Chair – chairs

But man – mans ???

/e/

/e:/

/o/

/o:/

Why do we have these plural forms in present day English?

Man – men / Foot - feet

Because in some words, to form the plural in Old English there was an umlaut: the

fronting of vowels before a high front vowel. But in some cases, the OE plural was lost

and ModE adapted the –S ending.

OE:

bōk - bēc

OE: /e/ ‘e’ ; /e:/ ‘ē’ ; /o/ ‘o’ ; /o:/ ‘ō’

macron (¯)

ModE: book – books ME: /e/ ‘e’ ; /e:/ ‘ee’ ; /o/ ‘o’ ; /o:/ ‘oo’

1

- Irregularities in spelling and pronunciation

Sounds and letters don't usually match (there is no correspondence). Sounds are not

always represented by letters/orthographic symbols.

In OE there was a full correspondence between sounds and letters

This is the reason for the present divergence between English spelling and

pronunciation.

Foot – Feet / Mean vs Steak / Divine – Divinity

2. Language relationships: The relationship of English with other languages

Identify language relationships

The comparative method

o Identify cross-language similarities and language relationships

o Language reconstruction

3. The process of language change

Is it abrupt or progressive?

Can we observe it?

Progress or decay?

Is there an absolute standard of correctness? Or Is the usage of speakers the

most important thing?

2

4. Sound change

Why does the sound system change?

To ease pronunciation.

Simplification (but it is relative)

Is sound change regular? Nowadays we believe it is an overstatement, but still

consider sound change to be highly regular and reducible to a set of rules.

Phonological change

Assimilatory changes

Dissimilation

Loss of sounds

Examples of phonological change:

o OE bridd > ModE bird

Metathesis (i.e. transposition of

sounds)

o OE thunor > ModE thunder

Epenthesis (i.e. insertion of sound)

Insertion of sounds

Metathesis

o OE wifman > wimman “woman”

Assimilation

o OE Anglaland > Modern English

England

Haplology (i.e. loss of sounds)

Anglaland - Angla genitive of Angle (Land of the Angles)

3

5. Grammatical change

Morphological change:

The classification of languages according to morphemes per word

The evolution of the English language:

The domino effect of linguistic change

A sound change > morphological change > syntactic change

Analytic / Isolating languages

• Analytic languages have sentences composed entirely of free morphemes, where each

word consists of only one morpheme.

• Isolating languages are “purely analytic” and allow no affixation (inflectional or

derivational) at all. Sometimes analytic languages allow some derivational morphology

such as compounds (two free roots in a single word).

A canonically analytic language is Mandarin Chinese. Note that properties such as

“plural” and “past” comprise their own morphemes and their own words.

[wɔ

mən tan

tçin lə]

1st

PLR play piano PST

‘we played the piano’

Plural and past comprise independent morphemes

Synthetic Languages

• Synthetic languages allow affixation such that words may (though are not required to)

include two or more morphemes. These languages have bound morphemes, meaning

they must be attached to another word (whereas analytic languages only have free

morphemes).

• Synthetic languages include three subcategories: agglutinative, fusional and

polysynthetic.

4

Agglutinative languages

Examples of canonical agglutinative languages include Turkish, Swahili, Hungarian

el-ler-imiz-in (Turkish)

hand-plr.-1st plr.-genitive case, ‘of our hands’

Multiple morphemes per word → only one meaning

o Inflectional languages

Am-o

Amar – present, singular, first person, indicative

Morphological change

The evolution of the English language:

The domino effect of linguistic change

A sound change → morphological change → syntactic change

Syntactic change

Verb in initial position: VSO

Welsh: Gwelsan (nhw) ddraigh (saw they a dragon)

SVO (Modern English)

English: They saw a dragon

Verb final languages: SOV

Japanese: Gakusei-da (student am)

- The classification of languages according to word order:

OE SOV > ModE SVO

- Grammaticalization

ModE “will” began life as full lexical verbs

OE Willan (to want) > ModE Will

‘If you will, we can go to the cinema’: will is used in its original meaning

- The role of Analogy

E.g. OE helpan, holp, holpen > ModE help helped helped

5

6. Semantic change

He was a happy and sad girl

sad: OE sæd “serious”

girl: ME gurle “young person”

Types of Semantic Change

Specialization -- Narrowing

Degeneration – Pejoration

Other types of semantic change

7. Word-formation

The growth of the English vocabulary.

Examples:

o OE fore (before) > fore- forecast

Derivation

o bedroom

Compounding

o to show > show

Conversion

o bus < omnibus

Cliping

o brunch < breakfast + lunch

Blending

8. The historical background of the English language. Loan words

Periods in the History of English

- Old English (5th c. – 11th c.)

- Middle English (11th c. – 15th c.)

- Modern English (15th c. - )

- Early Modern English (15th c. – 17th c.)

Old English

Celtic

Latin

Anglo-Saxon invasion (Angles, Saxons and Jutes)

Old Norse

/i:/

Middle English

Middle English

The Norman Conquest

/u:/

/e:/

Modern English

Great Vowel Shift (GVS)

The Rise of Standard English: spelling conventions based on ME conventions. But

spelling was not updated after GVS

Enlargement of the English vocabulary

6

/o:/

UNIT 1. GENERAL SURVEY OF THE SUBJECT. HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS: ITS OBJECTIVES

Main goal: Provide an overview of the origins and development of the English language

so that we can understand its present state.

Diachronic Linguistics (why and how languages change overtime) vs Synchronic

Linguistics (study the characteristics of language at a given point of time)

Diachronic / Historical Linguistics

Deals with the study of language change over time.

It is concerned with:

- why language changes: the reasons for the changes

- how language changes: the processes by which changes occur

It also helps:

- to recognize that language change is inevitable

- to realize that everyone speaks a dialect, that standard English is but one of a

number of Englishes, none of which is inherently superior to any other

Historical linguistics is NOT prescriptivist. It is NOT about:

- telling what is correct and incorrect in a language

- preserving pure forms

- preventing language change

Two main issues dominated the early course of historical linguistics:

Synchronic irregularity

Cross-language similarities

Synchronic irregularities

-

We can account for much of what seems illogical in language by referring to

historical periods in which the present anomaly fitted into a regular systematic

structure.

Forming the plural: IF HOUSES WHY NOT MOUSES?

sheep / sheep or deer / deer

foot / feet or goose / geese

ox / oxen

These irregularities can be easily explained if we take into account that they are the

remnants of earlier regular patterns.

Old English was a pure inflectional language. Inflectional languages are those languages

that modify the form of their words to provide grammatical information. Number,

gender and case.

7

In OE, words were masculine, feminine or neuter

- OE wif (it was neuter) > ModE wife

- OE fisc (it was masculine / a-stem nouns) > ModE fish

OE 'sc' /ʃ/ > ME 'sh' /ʃ/

OE had declensions like Latin

Singular

Plural

Nominative (Subject)

fisc

fisc-as

Accusative (OD)

fisc

fisc-as

Genitive

fis-es

fisc-a

Dative (OI)

fisc-e

fisc-um

ModE fishes comes from OE fiscas

In some cases, plural was formed by the process of fronting the root vowel (umlaut)

- OE fōt > fēt > ModE foot- feet

- OE tōþ - tēþ > ModE tooth - teeth

OE ‘þ’ /θ/ > ModE 'th' /θ/

þ is called “thorn” /θ/ Upper case, capital: Þ / Lower case: þ

In OE, nouns were classified in 7 types. We will focus on 3 of them: a-stem nouns, nstem nouns and root-consonant stem nouns

a-stem

Masculine nouns (fisc) & neuter nouns (scēp)

- Masc. nouns formed their plural adding –as > ModE –es E.g. fisc – fiscas (fish – fishes)

- In neuter nouns, sg and pl nouns were identical E.g. scēp – scēp (sheep – sheep)

n-stem

These nouns formed their plural taking the ending –an > ModE –en E.g. ox – oxen

root-consonant stem

These nouns showed the effects of a sound change known as umlaut: fronting or

fronting and raising of the root vowel in the plural forms. Vowel mutation

A-STEM MASC.

A-STEM NEUTER

N-STEM

ROOT-CONSONANT STEM

-as

Ø

-an

vowel mutation (fronting)

‘fish’ fisc > fiscas

‘sheep’ scēp > scēp

‘ox’ ox > oxan

’foot’ fōt > fēt

-

A-stem masculine: –as Modern English plural marker -(e)s

A-stem neuter: Ø Modern English zero plural: deer-deer/sheep-sheep

N-stem: -an Modern English plural marker –en: oxen/children

Root-consonant stem: vowel mutation Modern English: foot-feet, man-men...

8

Forming the past

Play-played vs Sing-sang

This synchronic irregularity be explained this way: Past tense is indicated by a mutation

(a change in the root vowel) (Proto-Indo-European, 5000 years ago). Germanic inherited

this way of forming past in strong verbs. This is called ABLAUT

In OE, verbs were either strong or weak.

OE Strong verbs

Strong verbs formed their past tense by changing the root vowel. This sound change is

called Ablaut. E.g. rise-rose. Ablaut is a systematic alternation of the root vowel in order

to indicate the meaning or grammatical function of a word. In verbs used to mark tense

and aspect.

Strong verbs have always had a mutation in their stem:

- OE Singan - Sang (ModE sing-sang)

- OE Risan - Ras (ModE rise-rose)

Ablaut in other IE languages

- Spanish: querer, quiero, quise

- Catalan: voler, vull, volguí

OE Weak verbs

Weak verbs formed their past tense by adding a dental suffix (-ode, -ede, -de, -te)*. This

was an innovation of Germanic languages.

In ModE those endings have evolved into -ed, -d, -t: played, associated, learnt

*/d/ and /t/ were dental at that time

But

Are verbs with ablaut and dental suffix in the past tense like keep-kept / think-thought /

bring-brought strong or weak verbs?

OE cēpan (infinitive) - cēpte (past) ModE keep – kept

-

-

They are weak verbs because the vowel alternation is merely additional to the

affixation of the past tense marker (t). This mutation in the vowel is NOT

motivated by ablaut.

If the past tense has a dental suffix that is not part of the infinitive form, that

verb will be weak.

Weak verbs were only distinguished by the addition of a dental suffix to the stem

of the past tense form. The root vowel was similar in both the present and past

tense forms.

9

OLD ENGLISH:

cēpan (inf.) - cēpte (past)

/e:/

/e:/

In ME period, quantitative changes affected the length of vowels: Long vowels

underwent shortening when preceding a sequence of two consonants

o /a:/ + 2 consonants → /a/

o /e:/ + 2 consonants → /e/

o /i:/ + 2 consonants → /i/

o /o:/ + 2 consonants → /o/

o /u:/ + 2 consonants → /u/

MIDDLE ENGLISH

OE cēpte (infinitive) > ME Kepte (past)

/e:/

>

/e/

In the late ME period, unstressed vowels underwent reduction to /ə/ and finally they

disappeared

- OE cēpan > ME Keep /ke:p/

- OE cēpte > ME Kept /kept/

EARLY MODERN ENGLISH

- ME Keep /ke:p/ > ModE keep /ki:p/

- ME Kept /kept/

*Great Vowel Shift ME /e:/ > ModE /i:/

*In the Early Modern English period, the Great Vowel Shift (GVS) took place. It affected

long vowels inherited from ME, which were raised in articulation or, if they were already

high vowels, were diphthongized.

OE cēpan > ME Keep(an) > ModE keep

/ke:pan/

/ke:p/

/ki:p/

OE cēpte > ME kept(e) > ModE kept

/ke:pte/

/kept/

/kept/

Irregularities in pronunciation: The history of English can also explain the spelling and

pronunciation of Modern English, which may seem chaotic or at least unruly.

The Great Vowel Shift

MIDDLE ENGLISH

MĒTEN

/e:/

MĒTE

/ε:/

EARLY MODERN ENGLISH /e:/ > /i:/ /ε:/ > /i:/

MODERN ENGLISH

MEET

/i:/

MEAT

/i:/

10

Other examples of Synchronic irregularity

How do you pronounce these words?

Heroic

Sulphuric

Basic

- hero /ˈhɪərəʊ/ - heroic /hɪˈrəʊɪk/

- sulphur /ˈsʌlfə/ - sulphuric /sʌlˈfjʊərɪk/

- base /beɪs/ - basic /ˈbeɪsɪk/

The English suffix –ic places stress on the immediately preceding syllable

electric photographic systemic ballistic

atomic

geographic

phonetic systematic

botanic hemispheric

syntactic sclerotic

terrific

specific

telegraphic

soporific

What about catholic and politic?

Why do they follow a different stress pattern?

Catholic < Latin catholicus

Politic < Old French politique < Latin politicus

The affix –ic in catholic and politic is etymological instead of synchronic (as in base basic)

Semantic irregularities

Why do we talk about withstanding a thing when we mean that we stand in

opposition to it rather than in company with it?

Withstand.

With= against / in opposition

Historical linguistics can also explain the principles of semantic change.

OE wið meant ‘against’

Wið changed its meaning in the late OE period: Wið > against > in company

WHY?

It is an example of semantic borrowing: the form was kept but the meaning of the word

was borrowed from Old Norse (við: in company)

Besides the word withstand, we have withdraw, withhold…

In Old English, bread meant “piece of food”, while hlaf meant “bread”.

Cross-language similarities (UNIT 2)

11

UNIT 2. LANGUAGE RELATIONSHIPS AND LANGUAGE RECONSTRUCTION.

LANGUAGE RELATIONSHIPS: CROSS-LANGUAGE SIMILARITIES

Cross-language similarities

The discipline of comparative linguistics involves the identification and evaluation

cross-linguistic similarities.

Explains why some languages have similar, although not identical forms: trying to

determine whether they are fortuitous resemblance or they represent systematic

correspondences (indication of a common origin).

Shows how the differences between related languages have arisen.

Cross language similarities can be motivated by several factors: fortuitous

resemblance, borrowings and common origin.

1. CHANCE SIMILARITIES:

All known languages have a limited number of phonemes and a finite number of

combinations for those phonemes > statistically highly likely that languages

develop accidentally similar forms.

Fortuitous resemblance > English

Finnish

home

home ‘mould’

into

into ’eagerness’

Fortuitous resemblance > English

man

Korean

man

2. BORROWINGS:

Similarities caused by the fact that a language has taken over a feature of another

or because both languages borrowed a form from a 3rd language.

Borrowings >

English

French

colour

couleur

flower

fleur

knife

canif

river

rivière

12

3. COMMON ORIGIN: In this case, languages show systematic patterns of similarities and

differences rather than mere resemblances. The only thinkable explanation for these

systematic correspondences is that both languages are changed forms of what was once

a single language > related languages that belong to the same family and have a

common ancestor.

Common origin > descend English

from the same language

hand

German

Hand

milk

Milch

son

Sohn

book

Buch

Proof of relatedness

We say that 2 languages are related -used to be the same language- if they exhibit

recurring correspondences in basic vocabulary.

Recurrence: The requirement that correspondences RECUR eliminates (or

anyhow greatly reduces) the possibility that the similarities are nothing but

accidents

Correspondences: regular, systematic alignments mainly at the phonetic and

morphological levels. E.g. A certain sound in a language systematically

correspond to another sound in another language.

Basic vocabulary: words which show the highest level of LEXICAL CONTINUITY

through time. It is among these words that we are likeliest to find forms retained

from earlier historical periods (e.g. numbers, body parts, animals)

Historical linguistics tries to explain this 3rd case.

In the 3rd case (common origin) the systematic study of earlier language states can also

help to:

Explain why related languages have similar, although not identical forms.

Show how the differences between related languages have arisen.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ENGLISH AND GERMAN

English

German

ten /ten/

zehn /tse:n/

to /tu/

zu /tsu/

better /ˈbetə/

besser /besər/

water /ˈwɔːtə/

Wasser /vasər/

Systematic correspondence:

English /t/ / #______ → German /ts/ / #______

English /t/ / v_____v → German /s/ / v______v

13

Phonological level

English

German

no /nəʊ/

nein /naɪn/

home /həʊm/

Heim /haɪm/

stone /stəʊn/

Stein /ʃtaɪn/

English /əʊ/ systematically corresponds to German /aɪ/

Morphological level

English

German

younger

junger

older

älter

colder

kälter

Both languages use ER to grade adjectives (comparative).

Lexical level

English

German

house

Haus

book

Buch

finger

Finger

They share the same form, pronunciation and meaning.

We use phonetics and phonology and lexicon because it's more reliable. Sound changes

are regular.

English and German forms are very similar and they differ in a systematic way

Reasons

for

their

similarities:

- Similarities: both have

evolved from a single earlier

parent language. Germanic

Reasons

for

their

differences:

- Differences: due to split-up

of this earlier language into

different branches with

separate development

Germanic:

- West Germanic: English /

German

North

Germanic:

Norwegian

- East Germanic: Gothic

14

ENGLISH AND ROMANCE LANGUAGES

English and the Romance languages are also related.

This is because Germanic and Latin have a common ancestor, called Proto-IndoEuropean.

We can find evidence of this common origin in the systematic phonetic correspondences

that English and the Romance languages (e.g. Spanish and Catalan) exhibit.

English

father

for

fish

thunder

three

heart

hound

head

Spanish

padre

por

pez

trueno

tres

corazón

can

cabeza

Catalan

pare

per

peix

tro

tres

cor

ca

cap

Systematic correspondences

Spanish and Catalan voiceless plosives correspond to English voiceless fricatives

/p/ > /f/

/t/ > /θ/

/k/ > /h/

Spanish and Catalan voiced plosives correspond to English voiceless plosives

/b/ > /p/

/d/ > /t/

/g/ > /k/

English

lip

purse

tame

two

corn

cat

Spanish

labio

bolso

domar

dos

grano

gato

Catalan

llavi

bossa

domar

dos

gra

gat

GRIMM'S LAW

The Germanic family is distinguished from other IndoEuropean languages by certain

phonetic changes, which took place between ProtoIndoEuropean and Germanic

IE had 3 types of plosive sounds:

- voiceless stops

- voiced stops

- voiced aspirated stops

15

PIE voiceless plosives > Germanic voiceless fricatives

/p/ > /f/

/t/ > /θ/

/k/ > /h/

PIE voiced plosives > Germanic voiceless plosives

/b/ > /p/

/d/ > /t/

/g/ > /k/

Whereas in the rest of the PIE languages plosives remained unchanged in the Germanic

languages PIE plosives underwent radical changes.

PIE

* piskos

* treies

* kerd

* leb

* dwo

* yeug

Spanish

pez

tres

corazón

labio

dos

yugo

English

fish

three

heart

lip

two

yoke

Why do you think there are Modern English pairs such as:

Father - paternal

Three - trio

Heart – cardiac

Father, three, heart are from Germanic origin

Parental, trio, cardiac are borrowings from Latin.

o Paternal > Latin Paternalis

o Trio > Latin Trio

o Cardiac > Latin Cardiacus / French cardiaque

LANGUAGE RECONSTRUCTION

Proto = reconstructed

Proto-Indo-European = PIE

Explanation

So far, we have seen that by comparing two or more languages we can identify

systematic correspondences between them. Such correspondences indicate that

they are related, that is, they have a common ancestor.

Often that ancestor language is a dead language with no written or oral records:

What can we do then?

16

What if you don't have records of a language?

Even if there are no written records of the common ancestor, it is possible to

reconstruct it (at least some aspects) by using the comparative method.

On the basis of data provided from modern languages, we can make a kind of

estimation about what protolanguages might have been like.

Only comparison with other languages can clarify which features of a language are

due to inheritance or borrowing.

Language Reconstruction

Jones, a British judge who lived in India, discovered in the 18th century that "the Sanskrit

language... bearing to both of them [Latin and Greek] a stronger affinity than could

possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed that no philologer could

examine the mall without believing them to have sprung from some common source,

which perhaps no longer exists: there is a similar reason… for supposing that both the

Gothic and the Celtic… had the same origin with the Sanskrit”

Sanskrit

pitár

matár

duva

Latin

pater

mater

duo

Greek

pater

mater

duo

Old English

faeder

modor

twegen

How can we explain these similarities?

By chance?

Due to borrowing processes?

Common origin?

- After Jones' declaration, scholars began the systematic comparison of Sanskrit, Latin,

Greek, Germanic, Celtic and other related languages.

- Their aim was to establish the relationship between these languages and reconstruct

PIE (Proto-Indo-European), the language from which they had evolved.

17

Language reconstruction: The comparative method

It is the most important of the various techniques we use to recover linguistic

history.

It focuses on the identification of recurring correspondences at the phonetic and

morphological levels between cognates in two or more languages.

Language phonetic and morphological characteristics are far more stable overtime

than are syntax, semantics, or other aspects of language.

Sound correspondences are reliable: because sounds are not usually borrowed from

other languages. Sound changes are quite regular so the original sound can be traced

back quite easily.

Morphological correspondences are very reliable: Not borrowed from other

languages

Adjective Gradability:

German

klein kleiner kleinste

They have inherited the grading from Germanic

Steps in language reconstruction

1. Assemble cognates

2. Establish sound correspondences

3. Reconstruct the proto-sound

majority wins

directionality

economy

18

English

small smaller smallest

1. Assemble cognates

- Cognates are words with similar, not identical, form and meaning in different

languages

E.g. Three

Old Saxon

Romanian

Sanskrit

Turkish

thria

trei

trayas

üc

- Systematic sound correspondences between words with similar form and meaning are

the first clue that the languages are related.

Latin

English

pes

foot

pater

father

- We have to look for systematic correspondences between languages rather than

similar looking words, which can be misleading

- Reject words which are identical or very close in phonetic form because cognates

develop independently and are subjected to sound changes in their own languages.

Borrowings:

Fr. mouton Eng. mutton

Fr. bouton

Eng. button

- By knowing about the timing and nature of the interaction between two languages, we

can identify plausible loan words

Relationship between English & French started in Middle English, after 1066 (The

Norman Conquest). English borrowed from French:

o Legal words

o Food related words

o Fashion related words

How to recognize cognates?

Core vocabulary (everyday objects and concepts) resist borrowing

body parts

kinship terms

plants

animals

2. Set up sound correspondences

Tongan

Samoan

Rarotongan

tapu

tapu

tapu

/t/

/t/

/t/

/a/

/a/

/a/

/p/

/p/

/p/

/u/

/u/

/u/

Hawaiian

kapu

/k/

/a/

/p/

/u/

19

colours

numbers

religion-related terms…

OE

niht

/n/

/i/

/h/

/t/

/i/

Latin

noctis

/n/

/o/

/k/

/t/

/i/

/s/

Sanskrit

naktam

/n/

/a/

/k/

/t/

/a/

/m/

3. Reconstruct the proto-sound

In reconstructing the original sounds, some principles have to be taken into account:

1. Majority wins

2. Changes must be plausible (directionally)

3. Reconstructions should fill gaps in phonological systems rather than

create unbalanced systems.

Reconstruct the proto-sound: majority wins

The reconstructed form tends to be the sound which has the widest distribution in the

daughter languages.

Tongan

Samoan

Rarotongan

tapu

tapu

tapu

/t/

/t/

/t/

/a/

/a/

/a/

/p/

/p/

/p/

/u/

/u/

/u/

*: the most common (majority wins)

Hawaiian

kapu

/k/

/a/

/p/

/u/

Why majority wins?

More plausible

*t

t

t

t

*/t/

*/a/

*/p/

*/u/

Less plausible

*k

k

t

t

t

k

Why majority wins?

It is more plausible that one of the daughter languages underwent a certain sound

change than multiple languages underwent the same sound change.

20

Reconstruct the proto-sound: directionality

Majority wins principles is overridden by the principle of directionality.

Principle of directionality: There are certain sound changes that very common or

natural while others are extremely rare or uncommon changes only go in one

direction:

Non-palatal sounds > palatal in contact with front vowels (but not the other way

around).

Voiceless sounds > voiced sounds in voiced environments (but not the other way

around).

Weaking:

o Fricativitation

o Degemination

o Vowel reduction

o Deletion

Examples of sound changes that only go in one direction

Palatalization

Non-palatal sound > palatal in the context (in contact) of front vowels (namely /i/ and

/e/) but not the other way around. This change usually applies to velars and alveolars

*/k/ > /tʃ/ / [+ front vowels]

/g/ > /j/ / [+ front vowel]

/s/ > /ʃ/ / [+ front vowel]

* In some languages /k/ > /tʃ/ / [+front vowel]/ > /ʃ/

Non-palatal sounds > palatal in contact with front vowels (). /k/>/tʃ/ /g/>/j/ /s/>/ʃ/

An example of unidirectional sound

Latin

Italian

Romansh

/Kentum/

/tʃento/

/tʃient/

k

tʃ

tʃ

/k/ or /tʃ/? Majority wins?

/tʃ/ > /k/ is this sound change natural? No

Non-palatal sounds > palatal in contact with front vowels: /k/ > /tʃ/.

The proto-sound is /k/ even though it is not the most widely distributed in this case.

Voicing between vowels or voiced sounds: Voiceless sounds > voiced sounds in

voiced environments.

/p/ > /b/ / v______v

/t/ > /d/ / v______v

/k/ > /g/ / v______v

21

Italian

Spanish

Portuguese

/kapo/

/k/

/a/

/p/

/o/

/kabo/

/k/

/a/

/b/

/o/

/kabu/

/k/

/a/

/b/

/u/

*k

*a

*p → unidirectional direction

*u

/p/ or /b/?

Majority wins?

/b/>/p/ is this sound plausible in this context?

Voiceless sounds > voiced sounds in voiced environments but not the other way around.

/p/ should be the proto-sound although it is not the most widely distributed in the

daughter languages

Weakening: sound changes involving a decrease in constriction degree

Fricativization

e.g. /p/ > /f/

Lat. pater > Eng. father

e.g. /b/ > /v/ / voiced environments

Degemination

/tt/ > /t/

Lat. mittere >

Sp. meter

Vowel reduction

Unstressed vowel > /ə/

OE nama /nama/ >

MiddleE name/namə/

Deletion (extreme Loss of final vowels

case

of

weakening)

Loss of final or medial endings

An example of unidirectional sound

Latin

Lithuanian

tres

trys

/t/

/t/

/r/

/r/

/e/

/i/

/s/

/s/

Old English

þri

/θ/

/r/

/i/

/t/ or /θ/? Original /t/. Fricativization

/s/ or no sound? /s/. Deletion

22

OE nama /nama/ >

ModE name/neim/

OE helpan > to help

Old Norse

þri

/θ/

/r/

/i/

*/r/

*/i/

Reconstructions should fill gaps in phonological systems rather than create unbalanced

systems

Balanced

Unbalanced

i

u

e

i

o

e

a

/dh/

p

b

t

.

k

g

o

a

or

/d/

p

b

t

d

k

g

The answer is /d/

Problems with the comparative method

- There might be features that may have been lost in daughter languages and cannot be

reconstructed on the basis of the evidence provided by living language

- Daughter languages do not develop from the ancestor in the same way: some are more

conservative than others

SUMMARY:

Directionality:

1. Voicing of voiceless sounds in a voiced environment

2. Devoicing of voiced sounds at the end of the word

3. Palatalization

/k/ > /tʃ/ / FRONT VOWELS

/g/ > /j/

/s/ > /ʃ/

4. Weakening

- voiceless plosives into voiceless fricatives

/p/ > /f/

/t/ > /θ/

/k/ > /h/

- Reduction

- vowel > /ə/

- /ə/ > ∅ at the end of the word

Economy

Majority Wins

23

UNIT 3. THE PROCESS OF LANGUAGE CHANGE

Main topics to cover in this unit

1. Can we argue for a complete dichotomy between synchronic and diachronic

linguistics in language studies?

2. Can the interdependence between the various linguistic levels be ignored in the

study of language change?

3. Can we observe the process of language change or we can just describe its effects?

4. How does language change originates and spread?

5. Why do languages change?

6. Is language change a matter of progress OR decay?

Questions

Can we argue for a complete dichotomy between synchronic and diachronic

linguistics in language studies?

Can the interdependence between the various linguistic levels be ignored in the

study of language change?

Many linguists trace the history of modern linguistics back to the publication in 1913 of

the book Course in General Linguistics by Ferdinand de Saussure, which agglutinates the

main tenets of early structuralism.

Diachrony: describes language change and language development.

Synchrony: describes language structure at a given point in time, without considering

previous or ongoing language changes.

Saussure and the early structuralists argued for:

A complete dichotomy between diachronic and synchronic studies because it was

thought that the changes that had occurred in a language were irrelevant in a

synchronic analysis. Historical information was considered to be irrelevant in a

synchronic analysis of the language

Additionally, they also argued that changes affected not the system as a whole,

but only individual elements.

This position was challenged at the First International Congress of Linguistics in 1928.

Trubetzkoy and Jakobson (school of Prague, also structuralists) argued that:

• A strict dichotomy between synchronic and diachronic studies had to be rejected

because by making reference to earlier historical periods we can account for some

aspects of the present state of the language.

• Language analysis must take into account the interdependence of all the elements of

a linguistic system. Therefore, any change will affect the whole system.

Some examples: The interdependence of the various Linguistic levels and the

overarching effects of language changes

24

1. Phonological changes can have consequences on the lexicon

Sound change > lexical change

Front

Back

OE /y:/ > ME /i:/

Unrounded Rounded Unrounded Rounded

OE /y/ > ME /i/

Close

i i:

y y:

u uː

OE cynn > ME kin

Mid

e e:

(ø øː)

o oː

OE pytt > ME pit

Open

æ æː

ɑ ɑː

OE fyr > ME fire

In Middle English > unrounding of OE /y:/

OE þyncan ‘to seem’ > ME thinken

OE þencan ‘to think’ > ME thinken

Þyncan was lost owing to the fact that both þyncan and þencan gave ME. Think(en), as

a consequence, they became confused and finally fell together. The contiguity of sense

also helped.

I think you are right = It seems to me that you are right

I have to think about it

There is a connection between a sound change and a lexical change

Quean vs Queen

‘prostitute / young woman’

’the ruler of a state’

In ME they were distinguished by their pronunciation

Quean vs Queen

ME /ɛ:/

ME: /e:/

In the Early ModE period > Great Vowel shift

Quean vs Queen

ME /ɛ:/ >/i:/ ME: /e:/ > /i:/

Quean has disappeared nearly everywhere except Australia (prostitute) and Scotland

(young unmarried woman) because the homophonic clash caused by the Great Vowel

Shift. The GVS only affected long vowels

2. Phonological changes can also have consequences at the morphological and

syntactic level.

Sound change > Morphological change > Syntactic change

OE was an inflectional language. Middle English reduction of unstressed vowels to /ə/

caused the loss of case inflexions, as a consequence the distinction between the

different cases was lost and therefore, this situation led to a stricter word order.

NOUNS inflected in Gender (Masculine, Feminine and Neuter), Number (Singular &

Plural), Case (Nominative -Subject-, Accusative -OD-, Genitive -Possessive-, Dative -OI-)

25

Cyng = king

Old English nouns

a-stem declension (masc.)

Middle English

nouns

Late Middle

English nouns

Singular

Plural

Singular Plural

Singular

Plural

Nominative

cyng

cyngas

king

kinges

king

kings

Accusative

cyng

cyngas

king

kinges

king

kings

Genitive

cynges

cynga

kinges

kinges

king's

kings

Dative

cynge

cyngum

king(e)

kinges

king

kings

OE:

Inflectional Language

Grammatical information was expressed by means of inflections (unstressed)

Flexible syntactic patterns

Early ME:

Unstressed vowels > /ə/, spelling changed 'e'. E.g. kinges in genitive & dative =

analogy

/ə/ > ∅ (lost) apocopate

This phonetic change lead to a grammatical change. Loss of inflections: Case

distinctions are lost. We cannot resort to the form of the word to know its

grammatical function

Late ME:

- Syntactic change:

Rigid word order SVO

Function words. Prepositions E.g. Angl-a-land : Land of the Angles -a-: genitive

plural marker

Effect of vowel reduction on morphology

OE inflectional endings: -es, -e,-as,-a, -um disappeared:

-‘s genitive singular

-(e)s plural

Thus, case distinctions were lost. English could not rely on inflectional endings to

indicate the syntactic function of words any more that lead to a syntactic change.

Syntactic change

If we don't have endings, word order (and use of prepositions) is essential

The loss of case distinctions meant that grammatical information was not provided by

modifying the form of the word anymore. With the loss of case system alternative ways

of expressing syntactic functions were needed such as stricter word order and function

words.

26

CHAIN REACTION

Sound change

→

Morphological change

Vowel reduction:

Unstressed vowels > /ə/ > ∅

→

Syntactic change

Loss of case distinctions:

OE inflectional endings disappeared.

Only the ending –es survived

Rigid word order (SVO) and use of

function words:

To dative > to the king

Of genitive > of the kings

3. Caribbean Spanish vs Standard Spanish. Standard Spanish allows independent

pronouns to be absent.

Sound change > syntactic change

It has been observed in Caribbean Spanish that there is a much higher frequency of

occurrence of the pronouns: tú, usted, él and ella than in other varieties of Spanish.

In Caribbean Spanish final the final -s is lost: –s > ø

Verbs forms which are distinguished by this inflection fail to be distinct if the final –s is

lost.

(Tú) andas vs. (Él) anda

The loss of distinction is compensated for through the use of pronouns.

Tú anda vs. Él anda

Previous examples are a reason to discard a strict division between synchronic and

diachronic linguistics, on the one hand, and between phonetics, morphology, syntax and

semantics, on the other.

A broad view of language will be required in order to explain language change, a view

that must include the structure of language as a whole and how its different parts

interact with one another.

On the basis of these examples:

Can we argue for a complete dichotomy between synchronic and diachronic

linguistics in language studies? NO

Can the interdependence between the various linguistic levels be ignored in the

study of language change? NO

27

SYNCHRONIC VARIATION

A second reason to avoid a strict dichotomy between synchronic and diachronic studies

is synchronic variation. It means that at any given point in time there will be linguistic

elements at different stages of development coexisting in the usage of speakers.

In other words, archaic/traditional forms and new advanced forms coexist in the usage

of speakers, because a language at a given stage is not stable.

E.g. Present Indicative in Middle England

South

North

Midlands

1st Sing.

-e

∅

-e

2nd Sing.

-est

-es

-est

3rd

-eth

-es

-eth/-es

-eth

-es

-e(n)/-es

Sing.

Plural

Middle English 3rd person singular: -eth / -es (loves, loveth)

The –s marker of 3rd person singular is relatively new. It comes from the late ME

period.

Over the Middle English period, the Midlands dialect in

the third person singular used both the Northern ending

and the inherited OE ending that was used in Southern

(more conservative) dialect (-es / eth).

Archaic forms and advanced ones coexist in the usage

of older and younger speakers.

28

New Guinea pidgin. Tok pisin

(Tok=talk, Pisin=pidgin)

Pidgin: a language which develops as a

contact language, when groups of people

who speak different languages come into

contact.

It usually has a limited vocabulary and a

much reduced grammatical structure.

Official languages of New Guinea:

- Tok pisin

- English

- Hiri Motu

liklik manggi – small boy

ol liklik manggi – small boys

dispela haus – this house

ol dispela haus – these houses

A change begins to spread in the language:

A plural suffix derived from English –es (contact between languages) is used along with

the plural marker ‘ol’.

ol liklik manggi

liklik manggis

“small boys”

SO and what next?

1. Plural suffix may spread to more nouns.

2. Original situation (with plural ol) may continue.

3. Diglossic situation may arise: a linguistic situation in which two languages or two

linguistic forms coexist, one of which is a lower or socially stigmatized

dialect/form and the other is a higher or prestige dialect/form.

That was the case of English and French during the English Middle Ages.

SYNCHRONIC VARIATION IN MODERN ENGLISH

Phonological differences between British and American English

Rhoticity: pronunciation of non inter vocalic –r (near, hurt)

Rhotic (traditional pronunciation) vs non-rhotic (18th c, Southeast England) English

Originally ‘r’ is pronounced in all positions and in all dialects of English.

250 years ago some English speakers in Southeast England started to drop ‘r’

before a consonant (arm) or at the end of a word.

Stigmatization of ‘r’ retention in Britain

Positive judgment on ‘r’ retention in USA

29

But…

is British English completely non-rhotic?

Dialect map for Arm

Areas of partial retention (r)

r dropping in the southeast > spread into

the north.

Prediction: in a hundred years the

original pronunciation with /r/ will

survive only in Scotland and Ireland.

Trudgill, Dialects, p.53

Phonological differences: stress pattern in French loanwords

Stress patterns

o a'dult vs 'adult

o ciga'rette vs 'cigarette

o a'pplicable vs 'applicable

British English has adapted them to the Germanic stress pattern (first syllable) because

it is more traditional

Syntactic differences between British and American English

X is different to Y (BrE) vs X is different than Y (AmE)

Lexical differences between British and American English

petrol (+) vs gasoline

lift vs elevator (+)

trousers (+) vs. pants

FACTORS THAT EXPLAIN VARIATION

LANGUAGE INTERNAL FACTORS

Phonetic motivation: ease pronunciation

Comparatives: formed by suffixation –er or analytically adding more. What is the

comparative form of clever?

cleverer and more clever coexist. (The phonological explanation is that the former is

difficult to pronounce and the latter is preferred by many speakers)

Information packaging:

• Ditransitive verbs: V + OI + OD (a) or V + OD + to dative (b)

a) I gave the woman at the reception the book SVOO

b) I gave the book to the woman at the reception SVOOblique

(The indirect object is heavy, thus structure 1 is avoided)

30

LANGUAGE EXTERNAL FACTORS

1. Uneven influence of a foreign language on different areas of a country: Old Norse

had a heavy influence on the northern part of England whereas French heavily

influenced central and southern England.

2. Age: Young speakers introduce new vocabulary and informal language.

3. Gender: Women use more standardized language than men

4. Social class

5. Social motivation. E.g.: New trends in pronunciation that arise in a certain social

group as a symbol of identity.

1. Uneven influence of a foreign language

Historical motivation for this geographical

distribution > Viking invasion. Vikings settled in

north and French settled in middle and

southern parts of the island

Heavy influence of Old Norse on the lower

North of England with 200 years of bilingualism.

- To lake /laik/ < from Old Norse leika "to

play”

- To play < Native OE word plegan

DIG

dig is borrowed from Old French

diguer (‘dig a ditch’)

- Native words are to delve and to

grave:

OE deolfan > ModE delve

OE grafan > ModE grave

Previous verbs delve and grave are

limited to the geographical edges of

the country.

31

2. Synchronic variation and Age

Differences in language between age groups represent ongoing change. E.g. Who

uses dude?

- Young men engaged in conversation with other men.

- Young men use stigmatized forms to profit from covert prestige: as a symbol

of social identity

Non-standard forms are usually considered low-prestige, but in some situations

stigmatized forms still enjoy a covert prestige among certain groups for the very

reason that they are considered incorrect by the rest of speakers.

Young generation prefers ungrammatical forms to create a social identity

Covert prestige: If I use a form that is stigmatized I use it because it is stigmatized

and want to create a trade

3. Synchronic variation and Gender

Considering the language use by yourself and people around you (e.g. your parents,

siblings, friends…), do you observe differences between men and women? If yes,

please provide some examples.

General tendencies noted in England

- Women are more status conscious than men.

- Women tend to use more standard language features than men.

Study of walkin’ (non RP) vs walking (RP) in Norwich

(% means speakers used the –in’ variant in 4% of the cases)

MC

LMC

UWC

MWC

LWC

Male

4%

27%

81%

91%

100%

Female

0%

3%

68%

81%

97%

MC: Middle Class

LMC: Lower Middle Class

UWC: Upper Working Class

MWC: Middle Working Class

LWC: Lower Working Class

Nowadays, in most of the cases, variation is introduced by the middle and lower classes

opposed as in the past, where upper classes introduced language changes.

Across all social groups: women generally use more standard forms than men = men use

more vernacular forms than women

4. Synchronic variation and Social Class

How do you pronounce “hammer”?

New trend to /h/ deletion:

- “hammer” > /‘amə/

- “hill” > /il/

This innovative variant, which is stigmatized by many speakers, is more frequent among

lower class speakers (lower class correlates with more h-dropping)

32

Conclusions

- Saussure's clear demarcation between synchronic and diachronic linguistics is now

seen to be idealized. In practice, purely synchronic studies are not possible.

- Research on language variation has shown synchronic states are not uniform:

traditional and new forms coexist in the usage of speakers.

- Thus, in a complete description of a language, there is always a 'core' or fixed structure

(traditional forms) and variation (new forms).

- Such variation indicates that language is changing.

- Thus, synchronic variation is language change in progress. It is the mechanism that

enables change.

Answers to the questions:

Can we argue for a complete dichotomy between synchronic and diachronic

linguistics in language studies?

o To understand the present state we need to take into account early

stages (irregularities)

o Synchronic variation:

Traditional and new forms coexisting

Synchronic states are not uniform

Can the interdependence between the various linguistic levels be ignored in the

study of language change? No. Changes only affect individual elements

THE ORIGIN AND TRANSMISSION OF LANGUAGE CHANGE

Questions

Can we observe the process of language change or we can just describe its effects?

How does language change originates and spread?

Why do languages change?

Can we observe the process of language change or we can just describe its effects?

Neogrammarians (a German school of linguists at the University of Leipzig, late 19thc

Junggrammatiker, 'young grammarians') proposed the hypothesis of the regularity of

sound change:

“The process of language change has never been directly observed” Bloomfield

“No one has yet observed sound change; we have only been able to detect its

consequences” Hockett

We have defined "Synchronic variation" as the beginning of a potential change.

Observe the consequences:

-eth/-es = loveth/loves

OE

ME

Early ModE ModE

-eth

-eth/-es

-es

33

-es

However, sociolinguists have shown that the process of language change (ongoing

changes) can be observed.

The pioneer is William Labov.

He realized that synchronic variation, which had often been ignored, may indicate

ongoing changes in language.

Sociolinguistic studies have shown that changes in progress can be observed if we

take into account synchronic variation. It had been frequently ignored but it is crucial

in language change and can be observed and analysed

HOW DOES LANGUAGE CHANGE ORIGINATES AND SPREAD?

The new tendency to /h/ deletion (hill /hil/ /il/) is not accepted at the moment. That

variation would lead to a final result.

The Neogrammarians said that a sound change affects all the words in which this sound

occurs simultaneously.

That would be the case of

ME: unrounding of OE /y:/. OE /y:/ > ME /i:/

- OE wyf > wife

- OE lyf > life

- OE bryd > bride

17th c change: /a/>/a:/ before voiceless fricatives /f, s, θ/ (prefricative lengthening)

- pass, fast, disaster

/a:/ /a:/ /a:/

- But gas, mass

/æ/ /æ/

Therefore, we can say that changes are not completely regular.

-

Linguists have now shown that changes do not occur simultaneously in all words.

Instead of that, a change spreads gradually through the lexicon.

A change originates in a few words and spreads gradually rather than affecting all

the relevant words at the same time.

For example, if a language undergoes devoicing of final stops, at the beginning only

some words will undergo this change, which will gradually spread to the other words

later on.

34

Centralization of diphthongs in Martha’s

Vineyard

Labov noticed that in Martha's Vineyard

diphtongs centralised: /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ were

becoming /əɪ/ and /əʊ/.

At first the new sounds fluctuated with

the existing ones, then the new ones took

over in the Island.

Martha's Vineyard is an island at the

Atlantic coast.

At the time of Labov's observations it had

a little over 5500 inhabitants.

Most of the permanent population lived in

the area of the island that was called

Down-Island.

A third of that permanent population,

most of them fishermen, lived in an area

called Up-Island.

The population consisted of three major

ethnic groups: People of Indian,

Portuguese and English origin.

During his investigations, as a first result Labov discovered that:

People of the age group 30 to 60 tend to centralize diphthongs more than younger

or older people.

Up-Islanders used the centralized diphthongs more than people living in the area of

Down-Island.

Fishermen centralize /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ more than any other occupational group.

The English and Indian inhabitants were more likely to use centralization than the

Portuguese.

Those results could not explain the centralization of these diphthongs, but there

seems to be enough evidence to state that age, occupations or ethnic groups might

be involved.

Language use & identification

Age

/əi/

/əu/

75-

25

22

61-75

35

37

46-60

62

44

31-45

81

88

14-30

37

46

Geographical distribution of centralization

35

/əi/

/əu/

Down-island

35

33

Up-island

61

66

To explain the centralization of diphthongs in Martha's Vineyard the criterion

attitude towards Martha's Vineyard might be important.

The hypothesis was that people who were positively oriented towards Martha's

Vineyard would show more centralization than people who had a negative attitude

towards it.

Degree of centralization and orientation towards Martha’s Vineyard

Persons

Orientation /əi/

/əu/

40

Positive

63

62

19

Neutral

32

42

6

Negative

09

08

Obviously people sharing a negative attitude toward Martha's Vineyard or/and

wanting to leave the island imitate the mainland accent.

People wanting to stay, mainly fishermen, expressed their positive attitude towards

Martha's Vineyard by using a stronger than average centralization.

The fishermen were an influential social group: They represented the good old

Yankee values and had a very positive attitude towards the island but a negative

attitude towards summer visitors.

It seems that the centralization of these diphthongs started in a small group of

words used by a group of fishermen, who had a negative attitude towards summer

visitors and the mainland. This change was used as a sign of identity by fishermen

and gradually spread to other words and speakers who also had a positive attitude

towards the island.

THE LEXICAL DIFFUSION THEORY

It was proposed by William Wang in 1969.

It argues that all sound changes originate in a single word or a small group of words

and then spread to other words with a similar phonological context.

But may not spread to all the words that could be potentially affected by a certain

sound change.

36

When charted on a diagram, the progress of change shows an S-shaped form.

First the change affects few words and the new and old pronunciation coexist.

But at some point the change spreads fast to many words.

At the end the change slows down and there may be some words left unaffected

The theory of lexical diffusion stands in contrast to the Neogrammarian hypothesis

that a given sound change applies simultaneously to all words in which the

appropriate context is found.

Changes spread progressively through the lexicon.

There are language items that will remain unchanged (there are exceptions to

change)

Answers to the question:

How does language change originates and spread?

- Changes tend to originate in a small group of words and spread gradually to other

words with similar characteristics.

- Sound changes are usually highly regular but exceptions are likely to occur.

- Language change is not completely regular.

- Language change is not abrupt, it is always progressive.

WHY DO LANGUAGES CHANGE?

While we know that language change is inevitable, we are less certain of its causes.

Bloomfield: "The causes of language change are unknown"

Early Theories of language change

- In the past, change was attributed to many different causes

- Some early theories of language change today seem hilarious or even socially and

morally disturbing

“Linguists are a marvellously clever bunch of scholars: there is really no limit to the

imaginative, elegant and intellectually satisfying hypotheses they can dream up to

account for observed linguistic behaviour”

Jean Aitchison, 2001

1. Geographical determinism

Voiceless Plosives > Voiceless fricatives

Consonant changes began in the mountains because expiration is more intense in

high altitudes.

The suggested cause is neither necessary nor sufficient.

37

-

2. Climatic determinism

It has been argued to be the cause of the rounding of /a:/ in the direction of /o:/ in

the northern languages of Europe.

Old English stān > English stone

Rounding was the result of unwillingness to open the mouth widely in the chilly and

foggy air of the North.

3. Racial and anatomical determinism

Germanic tribes had a greater build-up of earwax which

somehow impeded their hearing, resulting in a series of

consonantal changes.

Other theories claim that language change can be explain due

to physical attributes assumed to be associated with certain

races:

African languages have clicks or labiovelar sounds due to the

anatomical structure of the lips of black Africans.

4. Etiquette, social conventions

Iroquoian languages have no labial consonants because according to their social

conventions it is improper to close your mouth while speaking.

Some African languages have no labials because their speakers use labrets as an

ornamentation (discs inserted in holes cut into the lips)

5. Indolence

Linguistic change is the result of laziness.

Young people or particular social groups who are seen to be changing their speech

in ways disapproved by most speakers are assumed to be just too lazy to pronounce

correctly.

CURRENT THEORIES

The exact cause of language change is difficult to know, but it is usually due to a

combination of factors.

The following are a number of factors which have been put forward as the causes of

language change

1) External factors (sociolinguistic factors)

2) Internal factors (linguistic factors)

EXTERNAL FACTORS

Foreign influence

Fashion

Social Causes

38

o Foreign influence

Substratum

- When a language community learns another language, the new language is

modified by the linguistic patterns carried over from the native language.

- The language of the non-dominant (conquered) group influences the language

of the dominant group (invaders).

- The speech habits proper to the original language of the population (the

substratum language) will bring about changes in the structure of the new

language (the superstratum)

E.g. French is Latin with a Celtic articulatory habits.

E.g. The influence of Celtic on English

When people speaking different languages come into contact, one group learns

the other’s language but does imperfectly, and thus carries over native habits of

pronunciation and other linguistic patterns into the new acquired language.

Superstratum

- The language of the dominant group influences the language of the nondominant group.

- When conquering or migrating, people learn the language of the native

population and influence it.

E.g. Influence of French in English after the Norman Conquest. English borrowed from

French 10.000 words

England after 1066:

French:

English:

- Dominant, prestigious

- 90% population

- Official language of government and

- It became the 3rd language in its

administration

own country

- Ruling classes

- Non-Dominant (after French & Latin)

- Upper classes

Adstratum

- Borrowing that occurs across linguistic boundaries.

E.g. English in South Africa is influenced by Afrikaans.

o Fashion

Fashion might impose certain linguistic habits and make certain linguistic forms become

obsolete. E.g. It was fashionable in the ME period to borrow words from French.

- They have been courting for a year now

- Let’s go to the parlour to have a cup of tea

39

o Social Causes:

a. to be distinct

It was sometimes proposed that groups of people change their language on purpose

to distinguish themselves from other groups. The wish to be distinct

Slang as a symbol of group identity

It necessarily involves deviation from standard language, and tends to be very

popular among adolescents. To one degree or another, however, it is used in all

sectors of society.

It often involves:

- The creation of new linguistic forms or the creative adaptation of old ones.

- It can even involve the creation of a secret language understood only by those within

a particular group (an antilanguage).

- As such, slang frequently forms a kind of sociolect aimed at excluding certain people

from the conversation.

The use of slang terms is a means of recognizing members of the same group, and

to differentiate that group from society at large.

http://www.peevish.co.uk/slang/

Iffy, skint

It sounds iffy (weird, not good)

I’m skint (broke, with no money) Skint < skin

b. to keep social distance

Social climbing has been a moving force in language change.

Members of lower classes change their language by imitating the elite of society in

order to improve their social standing. At the same time upper classes change their

speech to maintain distance from the masses.

INTERNAL FACTORS

a) Functional needs

- The vocabulary has to adapt to our changing world

- Words which refer to obsolete objects may be lost, while new words may be

introduced to refer to new concepts or objects

- Changes are motivated by the speaker’s communication needs

E.g. e-mail, e-commerce, dot-com, App

40

More examples

NETIZEN: A person who spends an excessive amount of time on the Internet

[blend of Internet and citizen].

POPAGANDA: Music that is popular with the general public, and is trying to

promote particular ideas [blend of pop (clipping of popular) and propaganda]

IYKWIM: If You Know What I Mean

KTHXBYE: OK Thanks Bye

Ping:

1) Are you there?

2) Could you ping Bob and see if he's available for a 4pm meeting?

(In computing: The ping is the reaction time of your connection–how fast

you get a response after you have sent out a request)

Rehi (or merely re): hello again. Derived from Re: in the subject line of an email

means reply or response.

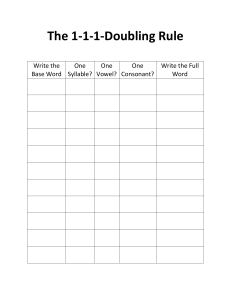

b) Analogy

- Changes orientated to increase regularity

- A more common pattern replaces a less common one eliminating irregularities

in the language.

OE boc-bec > ModE book-books

Traces of plural inflections in ModE

A-STEM

A-STEM

N-STEM

ROOT-CONSONANT STEM

MASC.

NEUTER

OE

ModE

-as

Ø

-an

fisc - fiscas

scēp - scēp

ox > oxan

-es *

Ø

-en

fish - fishes

sheep - sheep

ox > oxen

vowel mutation (ablaut)

man - men

vowel mutation (ablaut)

man - men

* It’s the only productive marker nowadays

OE helpan – holp – holpen > ModE help – helped – helped

Strong verb

Weak verb

Learned/learnt (on the analogy with the vast majority of verbs which form their past in

this fashion)

c) Structural (Intrasystemic) pressure

Most sound changes are motivated by this factor.

Languages tend to develop a balanced sound system, that is, to make sounds as

different from one another as possible by distributing them evenly in phonological

space.

Sound systems try to meet two principles:

- Balance: evenly distributed

- Maximum differentiation

41

Balanced

Unbalanced

i

u

e

u

o

e

a

o

a

Balanced vs unbalanced system

If for some reason, a language loses its high vowels, there would be an intra-systemic

pressure to fill the gap left by that sound by changing the remaining sounds (for

example, by making mid vowels higher in articulation). There is an attempt to make

the system balanced again.

So languages will acquire sounds to fill gaps and eliminate sounds that cause

asymmetries in the system

E.g. English voiced sound /ʒ/ was added to match the voiceless sound /ʃ/ already

existing.

d) Simplification

- Making the system more transparent, simple in morphology, phonology and

syntax.

- When a grammar becomes overly complicated or irregular, it may undergo

change to make it more accessible.

E.g. English has moved in the direction of noun plural always indicated by -s

- It is a relative concept, because it may produce complexities in other parts of the

system

Examples:

o stānas “stones” (a-stem, masculine)

o nāman “names” (n-stem)

o word “words” (a-stem, neuter)

-

Process of regularization -es led to the loss of inflections and it affected syntax

Many sound changes can be considered to simplify the production of sounds

Words may become shorter and we need less physical effort to produce them

But simplification is a relative concept, because it may produce complexities in

other parts of the system

Syncope (dropping of a vowel in the middle of a word) could be considered as

simplification, but it also results in consonant clusters.

e) Ease of articulation: some sound changes are often explained as increasing the ease

of articulation and improving perceptual clarity

- Some sounds can be pronounced together more smoothly if they are alike, or if they

are different (assimilation and dissimilation)

- Elision and intrusion can also help to make articulation easier.

- Metathesis (transposition of sounds in a word).

42

E.g.

o Sp. Peregrino --- Eng. Pilgrim

One of the English liquids dissimilated /r/ → /l/ to ease pronunciation

o Most Spanish speakers when pronouncing 'Spanish' add an /e/:

/ˈespænɪʃ/ vs /ˈspænɪʃ/

f) Hypercorrection: it results from an effort of the speaker to correct what he or she

thinks it is a mistake (which is not, in fact, a mistake.)

E.g. Speakers who wish to avoid the North American feature of flapping (voicing the ‘t’)

may pronounce

Cheddar /tʃetə(r)/

g) Folk etymology: change in the form of a word or phrase resulting from a mistaken

assumption about its composition or meaning

The remodelling of 'Chaise longe' as 'Chaise lounge' because one uses it for lounging is

an example of this process.

lounge=lay

Another example comes from the Spanish vagabundo ‘vagabond, tramp’, which gave

rise in some varieties of Spanish to vagamundo ‘tramp, vagabond’, through the folketymological association with vagar ‘wander, roam, loaf’ and with mundo ‘world’

Question

Is language change a matter of progress OR decay?

PROGRESS OR DECAY

“Time changes all things: there is no reason why language should escape this universal

law.”

“Everything is in a permanent state of change, and language, like everything else, is also

continually changing.”

Saussure

Language change is inevitable but does it imply progress or decay?

“Tongues, like governments, have a natural tendency to degeneration.”

Samuel Johnston

Purist attitude

Purists believe in some sort of absolute standard of correctness, which can be found in

grammars and dictionaries.

43

Non-purist attitude

What is important is the usage of speakers.

If a new word is accepted and used by a number of speakers, that word can be

considered a new addition to the lexicon of the language.

Max Müller, a 19th century scholar, claimed that in the written history of all the

languages of Europe, he could observe only “a gradual process of decay”.

Many scholars thought that language was perfect in its beginning, but it is constantly

in danger of decay (degeneration). The proto-language from which Latin, Greek or

Sanskrit were derived was considered to be the most ‘pure’ form of language.

Change was seen as a degeneration of an original pure state of the language.

The purist attitude was at its height in the 18th century. It contributed to the

standardization of English.

But… What is Standard English?

Which English would you prefer? Why?

I did it vs I done it

Come quick! vs Come quickly!

The book that I bought vs The book what I bought

Them books vs Those books

I didn’t break anything vs I didn’t break nothing

I’m first, ain’t I? vs I’m first, aren’t I?

a, b, a, b, a, b

What is Standard English?

- “having your nouns and your verbs agree”

- “the English legitimized by wide usage and certified by expert consensus, as in a

dictionary usage panel”

- “what I learned at school, in Mrs McDuffey’s class. It really bothers me when I read and

hear other people who obviously skipped her class”

- “the proper language my mother stressed from the time I was old enough to talk”

- “one that few people would call either stilted or low, delivered with a voice neither

guttural nor strident, clearly enunciated”

Standard English, also known as Standard Written English (SWE), is the form of

English most widely accepted as being clear and proper.

Publishers, writers, educators and others have over the years developed a consensus

of what Standard English consist of. Standard English includes word choice, word

order, punctuation and spelling.

Basically, Standard English is a clear and proper form of language that includes word

choice, word order, punctuation and spelling.

44

MIDDLE ENGLISH

Northern dialect

Southern dialect. Kentish

Midland dialect:

West Midland dialect

East Midland dialect → the one CHOSEN because London is close to that area

In the 17th century, the suggestion that there was a right or correct way of speaking

seemed strange to most people.

Spelling was not uniform across dialects.

Concerns about English language focused on two areas: spelling reform and

vocabulary enrichment creating new words by affixation, compounding, blending...

The printing press led to think of the need of a unified written dialect. Spelling in

printed texts became fixed by about the mid-17th century.

Vocabulary enrichment was also considered: some authors thought that English

vocabulary need to be enlarged by borrowings from Latin and Greek, whereas other

authors argued that native resources were sufficient.

The 18th century was a period of linguistic conservatism.

Concern about refining, purifying and fixing the language.

This concern reflected people’s belief that the language had decayed from an

earlier, better state and that subsequent changes in the language had to be

prevented

18th century grammarians undertook the process of standardization of language.

18th century scholars thought that English had no grammar in the sense that it was

uncodified, unsystematised, so they set out to give English a Grammar by:

codifying the rules

establishing a standard of correct usage

removing supposed defects and common errors

They wanted to fix the language in the desire form and prevent further changes.

Prescriptive grammarians of the 18th century were self-appointed experts who

considered themselves qualified to make preserve the integrity of the language.

Samuel Johnson was among them.

The rules they used was the language spoken by the upper-classes

CODIFICATION

Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), author of the two-volume Dictionary.

It fixed English spelling and established a standard for the use of words with a great

deal of respect for upper-class usage.

Increase in the functions of use

- Standard English replaced Latin as the language of scholarship.

- English began to compete with French as the language of diplomacy.

45

ACCEPTANCE

What keeps Standard English in its high place?

Dictionaries and grammar

Style manuals

Schools

The media

Attitude toward language change nowadays

The 18th century attitude towards language is still widespread.

Comments from the press show that many people still consider language change

as corruption.

“Many people look in dismay at what has been happening to our language in the very

place where it evolved. They wonder what it is about our country and society that our

language has become so impoverished, so sloppy and so limited – that we have arrived

at such a dismal wasteland of banality, cliché and casual obscenity”

Prince Charles

“Bad grammar is a sign of carelessness in the use of language, which denotes a lack of

mental discipline in other areas”

Marland

The apostrophe protection society

In some circles, correct use of the apostrophe is taken as a measure of literacy – or

even intelligence.

For some people it has become a social issue which must be treated.

Others feel the time has come to abandon it entirely

Is language evolving to a more efficient state?

“Progress in the absolute sense is impossible, just as it is in morality or politics. It is

simply that different states exist, succeeding each other, each dominated by certain

general laws imposed by the equilibrium of the forces with which they are confronted.

So it is with language.”

J. Vendryès

46

Some more examples of prescriptive rules:

WORD CRIMES by Weird Al Yankovic