Serious Leisure & Information Activities: Self-Actualization & Engagement

advertisement

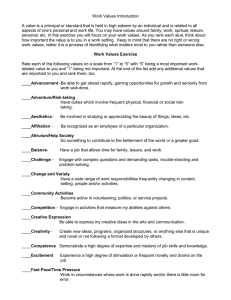

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/0022-0418.htm Information activities in serious leisure as a catalyst for self-actualisation and social engagement Yazdan Mansourian School of Information Studies, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, Australia Information activities in serious leisure 887 Received 9 August 2020 Revised 28 December 2020 Accepted 1 January 2021 Abstract Purpose – This paper reports findings from a research project about human information behaviour in the context of serious leisure. Various forms of information activities in this context have been identified and categorised to depict common patterns of information seeking, sharing, using and producing. Design/methodology/approach – The project adopted a qualitative approach in an interpretive paradigm using a thematic analysis method. Data-collection technique was semi-structured interview and 20 volunteers were recruited via a maximum variation sampling strategy. The collected data was transcribed and thematically analysed to identify the main concepts and categories. Findings – The participants have been experiencing six qualities of serious leisure during their long-term engagement with their hobbies or voluntary jobs and their experiences can be fully mapped onto the serious leisure perspective. The findings also confirmed serious leisure is a unique context in terms of the diversity of information activities embedded into a wide range of individual and collective actions in this context. Information seeking and sharing in serious leisure is not only a source of personal satisfaction for the participants, it also can provide them with a sense of purpose in a meaningful journey towards selfactualization and social inclusion. Research limitations/implications – The generalisability of the findings needs to be examined in wider populations. Nonetheless, the existing findings can be useful for follow-up research in the area. Practical implications – This study will be useful in both policy and practice levels. In the policy level, it will be beneficial for cultural policy makers to gain a better understanding about the nature of leisure activities. In the practice level, it will be helpful for serious leisure participants to understand the value of information seeking and sharing in their leisure endeavours. Also, information professionals can use it to enhance the quality of their services for the serious leisure participants who are usually among devoted patrons of libraries, museums, archives and galleries. Social implications – Learning about serious leisure can provide new insights on people preferences in terms of choosing different entertaining and recreational pursuits – such as indoor and outdoor hobbies – in their free time. Originality/value – The informational aspects of serious leisure is an emerging and evolving ground of research. This paper provides empirical evidence on this topic from a specific context in the regional areas in Australia. Keywords Information seeking, Information sharing, Social engagement, Serious leisure, Information grounds, Human information behaviour, Communities of interests, Self-actualisation Paper type Research paper “Leisure is not synonymous with time. Nor is it a noun. Leisure is a verb. I leisure. You leisure”. Mortimer Adler This paper is part of the author’s research program about human information behaviour in the context of serious leisure funded by the Faculty of Arts and Education at Charles Sturt University in Australia. The author express his deep appreciation to all the participants in this study. What they have done is a great example of generous information sharing. The author is also grateful to the reviewers for their constructive comments. Funding: This study was funded by the Faculty of Arts and Education at Charles Sturt University in Australia and the grant number is A541.3101.30603. Journal of Documentation Vol. 77 No. 4, 2021 pp. 887-905 © Emerald Publishing Limited 0022-0418 DOI 10.1108/JD-08-2020-0134 JD 77,4 888 1. Introduction Leisure activities are extremely diverse ranging from laying down on a couch and watching television to rock climbing. It can be purely pleasurable like taking a leisurely walk around a nearby park or highly challenging such as ultramarathon. In terms of the level of dedication and the required skills, a leisure pursuit can be casual or serious. Stebbins (1982) introduced the concept of serious leisure as all forms of leisure activities that require dedication, longterm commitment and special skills/knowledge. Leisure activities that need perseverance, can potentially turn into a career, need significant personal effort, create durable benefits, have a unique ethos and can form a feeling of identity are categorised as serious in this theory (Stebbins, 1982, 2001). This original idea gradually formed a conceptual framework which is now known as the Serious Leisure Perspective. It has been used in many studies, including the current one, as a theoretical framework to explore the realm of leisure. Serious leisure is a multidisciplinary topic and scholars from a broad range of disciplines look at it from their own perspectives. For example, from a social science view we can focus on the social benefits of serious leisure and how it can be a source of social connectedness. At the same time, scholars from multidisciplinary areas like wellbeing and quality of life focus on the importance of leisure as a sources of meaning and subjective wellbeing (Sirgy et al., 2017). This paper focuses on the human information behaviour aspects in serious leisure and reports findings from a qualitative study. The project has been carried out in Wagga Wagga that is a regional city in New South Wales of Australia. 2. Literature review The existing literature on serious leisure is scattered in various disciplines ranging from psychology and sociology to tourism and hospitality. However, leisure studies acts like an umbrella term to bring the various studies into a unified domain. Nonetheless, each study has its own focal point which makes it closer to one discipline or another. For example, positive psychology scholars investigate personal benefits of serious leisure (Chen, 2014; Pi et al., 2014; Liu and Yu, 2015; Kono et al., 2020). Their research has shown the participants generally experience positive psychological wellbeing, durable pleasure and resilience. Also, it helps them to reduce the stress of everyday life and increase their self-confidence to be more empowered to cope with challenges through a sense of control and self-determination (Kim et al., 2019). They have studied people from different social status and ages. For example, Chen (2014) reported that older adult volunteers having greater serious leisure characteristics enjoy a higher level of subjective wellbeing. As a result, serious leisure engagement can potentially contribute to creating a joyful and meaningful life (Iwasaki, 2007). Furthermore, serious leisure can be a type of coping strategy for people who are under huge pressure of the overwhelming demands of their job (Bunea, 2020). In general, research shows serious leisure can bring numerous personal and social benefits for the participants. From a personal point of view this is a source of self-confidence, sense of fulfilment, self-enrichment, self-expression, enhancement of self-image and satisfaction. From a social perspective, it is a rich source of social interaction, social inclusion and belongingness (Caldwell, 2005; Tsaur and Liang, 2008; Pi et al., 2014; Shupe and Gagne, 2016; Lee and Ewert, 2019; Dillette et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2014; Lee, 2020). Most studies report both personal and social benefits. For instance, Phillips and Fairley (2014) report: It was clear from the participants’ responses that umpiring was incorporated into their lives as a means as a key activity through which they persevered, and obtained beneficial outcomes including mastery of skills, enhancing self-image, socialising, as well as general health and fitness. (p. 196) Moreover, participation in serious leisure groups can facilitate the creation of social worlds, including development of social capital through improved means of social cohesion (Lee and Ewert, 2019; Dillette et al., 2019; Beaumont and Brown, 2015). Besides, serious leisure provides people with many opportunities to explore their capabilities and find their real strengths and passions. Thus, they will be able to experience new challenges and achieve greater goals. Personal benefits are also enormous including constant acquisition of knowledge (Cox et al., 2017), facing challenges (Lee and Ewert, 2019; Lee and Payne, 2016), personal commitment (Veal, 2017), improving emotional wellbeing and a means for authentic communication and emotional expression (Rampley et al., 2019) and also identity development (Lee and Ewert, 2019). Of course, this is not all about the positive outcomes. Serious leisure can create negative effects as well. For example, Rampley et al. (2019) report that it can potentially have a detrimental effect on the participants’ wellbeing if they become overly absorbed to the activity. Besides, most results are contextually bound to cultural and social backgrounds and we cannot easily generalise the findings. For example, Kono et al. (2020) examined the relationship between serious leisure and meaning of life as a part of eudaimonic wellbeing in two groups of Japanese and Euro-Canadian participants. They discovered cross-national differences in the relationships between serious leisure and meaning of life as a result of cultural differences. The informational dimensions of serious leisure is a productive topic in information behaviour scholarship because participation in serious leisure usually requires a constant pursuit of information and typically involves many information activities such as information seeking and sharing. Ross (1999) was among the first scholars who investigated this topic. She interviewed a group of committed readers to understand how pleasurable reading can be as a source of information. Around the same time, Jones and Symon (2001) studied lifelong learning as a type of serious leisure. Nonetheless, Hartel (2003) took the key step in this area when she introduced serious leisure as a new frontier in library and information science scholarship. A few years later Stebbins (2009) mapped this topic onto his original framework. Since then a number of investigations have been carried out to investigate the informational features of serious leisure in different groups. For example, Hartel (2006, 2010) report findings form her research about information activities and resources in gourmet cooking as a popular hobby. Lee and Trace (2009) explored rubber duck collecting. Case (2010) studied the information sources and information seeking habits of coin collectors. Fulton (2016) explored the genealogists’ information world and focused on how they create information in their hobbies. Fulton (2017) studied urban exploration and investigated the concept of secrecy and information creation and sharing in urban exploration. In general, during the past two decades serious leisure has been an emerging and evolving topic in information behaviour scholarship and several studies have been done on this topic. For examples, leisure information behaviours in hobby quilting sites (Gainor, 2008), communities of hobbyist collectors (Lee and Trace, 2009), dietary and food blogging (Savolainen, 2010; Cox and Blake, 2011), online fantasy sports (Hirsh et al., 2012), retired investors, (O’Connor, 2013), music record collectors (Margree et al., 2014), re-enactment (Robinson and Yerbury, 2015), motorsport enthusiasts (Joseph, 2016), gardening (Cheng et al., 2017), genealogy (Hershkovitz and Hardof-Jaffe, 2017), car restoration (Olsson and Lloyd, 2017), media fan communities (Price, 2017; Price and Robinson, 2017), information activities in ultra-running (Gorichanaz, 2017), fun life-contexts (Ocepek et al., 2018), information practices of music fans (Vesga Vinchira, 2019), basketball Twitter community (Sanchez, 2020) and music information seeking in fan clubs (Bronstein and Lidor, 2020) are among the long list of scholarly publications in this field. Mansourian (2020) reviewed the literature and suggested a model to demonstrate the diversity of information sources and patterns of information consumption in this setting. The model categorises serious leisure activities into three clusters: (1) intellectual pursuits, (2) creating or collecting physical objects/materials/products and (3) experiential activities. Accordingly, the participants are divided in three groups of appreciators, producers/collectors Information activities in serious leisure 889 JD 77,4 and performers. His review revealed in spite of commonalities among information activities in these groups, each category has its own priorities, source preferences and information behaviour. 2.1 Research questions 890 The current study aims to address the following research questions: (1) To what extent can we map the participants’ stories onto the serious leisure perspective? (2) What are the common patterns of information activities in the context of serious leisure? (3) What are the contextual factors that impact on information activities in serious leisure? 3. Research method This project adopted an interpretive paradigm and a qualitative approach. The datacollection technique was a semi-structured interview with open ended questions (presented in the Appendix) to understand the participants’ deep reflection about their leisure activities. The researcher used interview as the data collection tool because it enabled him to deeply explore the leisure experiences of the participants. Interview was an efficient data collection tool for the purpose of this study because it provided the researcher with an opportunity to listen to the participants’ stories and learn about their feelings, motivations and achievements. Moreover, this is a very common tool in qualitative leisure studies. As Cheng and Pegg (2016, p. 287) cited Bryman (2004) and report when the researcher has a clear focus then the semi-structured interview is the best means of data collection and enable her/him to delve more deeply into issues during the conversations. For the same reason many other researchers in leisure studies have used interview as their data-collection technique (e.g. Siegenthaler and O’Dell, 2003; Lee et al., 2019; Bronstein and Lidor, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). As the research’s approach was qualitative, the researchers collected data until reaching a saturation point but carried out a few more interviews to make sure there is sufficient empirical evidence to address the research questions. The collected data has been transcribed and analysed through a thematic analysis method (Bernard and Ryan, 2010; Braun and Clarke, 2006; Castleberrya and Nolenb, 2018). The Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee has approved the research proposal in February 2019. This approval has been based on the guidelines in the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research in Australia to make sure all the ethical aspects of the research have been thoroughly considered in this study. The research population included Wagga Wagga residents who are involved in at least one form of serious leisure endeavours such as volunteering, hobbies or amateurism during the past years. To have a broader perspective, the researcher used a maximum variation sampling method (Seale et al., 2007) to include people from different backgrounds who have been involved in different social activities. To form the sample, the researcher used Wagga Wagga Community Directory published by the city council to identify and contact the associations and societies in serious leisure and asked them to introduce potential participants. He also requested them to distribute the information sheet among their members. If they decided to take part in the study they have been free to choose between a telephone and face-to-face interview. If they prefer face-to-face interview, it has been conducted in a community centre or a public place like the city public library. The researcher also provided them with detailed information about the project to address their queries. During the data-collection process the researcher interviewed 20 participants (13 female and 7 male). Most of the participants preferred a telephone interview as it was easier to organise it. At the end, 17 interviews have been done through the phone and only three interviewees attended a face to face discussion. Information activities in serious leisure 891 4. Findings As the researcher used a maximum variation sampling, the participants have been involved in a wide range of hobbies, amateurism and voluntary activities such as cycling, gardening, knitting, soccer, bushwalking, traditional weaving, environmental activism, friends of the art, tennis club, bonsai growing, cricket, table tennis, amateur filmmaking, volunteering in local radios, music, poetry and volunteering in the public library language cafe for refugees and recently arrived immigrants who need to improve their English. More details about the sample and their activities are presented in Table 1. As the table shows, most participants (16 out of 20) have undergone some training to learn the required skills for their serious leisure and only four of them were entirely relied on their own independent learning. On average they have been involved with their hobbies or voluntary work for 17.5 years. Moreover, some of them have been participating in more than one activity at the same time. The average time they spend on their serious leisure was also varied from a few hours per week up to 25 h. For some of them it was variable depending on the time of the year. For example, outdoor hobbies like gardening, cycling or bushwalking mainly depend on the weather and cannot be done regularly during the year. The years of involvement with serious leisure was also varied in the sample ranging from 40 to 2 years. Nonetheless, the average years of activities for the sample was 17.5 which means that most of them have been involved with their chosen activity for a very long time. Code G Type of serious leisure YA T P1 M Volunteer radio broadcasting 16 Yes P2 M Volunteer radio broadcasting 2.5 Yes P3 M Cycling, gardening and radio broadcasting 40 Yes P4 F Volunteering at a public library language cafe 2 Yes P5 F Volunteer mentorship and library language cafe 8 Yes P6 F Home library service, language cafe and knitting 8 Yes P7 M Volunteering at a charity and in a committee 5 No P8 M Various volunteering (e.g. community projects) 30 Yes P9 M Volunteering at several community groups 35 Yes P10 F Soccer playing and walking group 12 Yes P11 F Volunteering and fundraising campaigns 8 Yes P12 F Weaving with a weaving group 11 Yes P13 F Red cross volunteering and language cafe teaching 2.5 Yes P14 F Environmental activities and friends of the art 30 No P15 F Tennis club and red cross volunteering 10 Yes P16 F Bonsai growing and volunteering 21 No P17 M Cricket, table tennis, filmmaking and music 30 Yes P18 F Volunteering at a gallery 20 Yes P19 F Poetry writing and volunteering at a gallery 20 Yes P20 F Walking group and gardening 40 No Note(s): YAs 5 The Years of Activities; T 5 Training; AHW 5 Average Hours per Week AHW 25 10 15 2–4 6–7 5–6 10 Variable 10–12 3–5 5–10 Variable 4–5 Variable Variable Variable Variable 5–6 Variable 10–15 Table 1. List of the serious leisure activities carried out by the participants JD 77,4 892 Through a thematic analysis of the interview transcriptions a number of themes have been identified and categorised. The findings are presented in three parts. The first part provides the themes that demonstrate the qualities of serious leisure illustrating to what extent the participants’ leisure activities can be mapped onto a serious leisure perspective. The second part addresses the research questions about their information activities in the context of serious leisure. The third part presents the findings about various sources of motivation and inspiration helping them to continue their passionate journey and also some challenges and barriers that hinder their activities in this context. 4.1 Part one: qualities of serious leisure The collected data was analysed inductively to discover the themes. In the next stage, the identified themes were compared with the serious leisure perspective deductively to find out to what extent the results are compatible with the theoretical framework. The themes were considerably well-matched with the framework and the participants experienced all the six criteria of serious leisure in their hobbies, amateur and volunteer engagements. In a nutshell, the sample has been actively involved with serious leisure and the below excerpts from the interview transcriptions reveal that their actions can be fully mapped onto the perspective. 4.1.1 Perseverance and commitment. Based on Stebbins’ theory, serious leisure participants follow their endeavours such as their hobbies or voluntary jobs continually and demonstrate their commitment and dedication to it. The findings suggest perseverance was an obvious theme in the dataset as all the participants were enthusiastically involved in their chosen activity for a long term. The below excerpts disclose their dedication. P1: . . . you’ve got to be committed to dedicate at least 15–20 hours . . . you need to provide, make sure you’ve got the time to prepare your program . . . the most important thing is to be reliable and committed. P3. I’m committed to that, and obviously I’m also committed to board meetings which are once a month. And any activities that flow out of the board meeting. So it’s reasonably flexible, but probably is, I mean it does have some commitments. P18. I suppose the first thing is they have to have the interest do not they and desire to be involved. I think that would probably be crucial because if people are not interested in it they will not commit themselves wholeheartedly. Moreover, most of them have been involved in more than one hobby or voluntary job during several years but usually one of the activities have been their main hobby and the rest remained as secondary: P8: I’ve done so many things. I used to volunteer to go into nursing homes and visit elderly people, I’ve worked in an environment centre in one town as a volunteer where we would distribute information on environmental issues . . .. So there are quite a few things that I’ve done over the years. P9: I was on different sporting bodies, because my children play sport. But I was in a couple of other community groups . . . I used to go to meetings to, because of my political aspirations, and then, also influenced, as I say, by my children at school, commitments, and sporting committees and things like that. 4.1.2 Potentiality to turn into a career. The second quality of serious leisure is its potential to turn into a career. The findings suggest most of the participants have been thinking about the possibility of turning their hobbies or voluntary job into a career as they could see the potential for this shift. However, none of them went through this pathway and they prefer to keep it just as a leisure pursuit or a voluntary practice. P2. It is a leisure activity. I do not see it as work. I do not intend to make a career . . . I mean there have been a number of people in the past who have gone on to become very well known in the industry and they started at our radio station . . . but for me no it’s – it’s a leisure activity that I enjoy. P1. I’ve always had an interest in radio, ever since I was a teenager. I did want to get into radio as a career when I was young. But the opportunities and everything else just did – never happened . . . when I came to live here . . . I looked for the local radio stations and I found that station, I liked the music that they play. 4.1.3 Significant personal effort. The third feature of serious leisure, that makes it different from casual leisure, is its requirement for personal effort based on some special knowledge, skills or training. Therefore, serious leisure is not an effortless practice and can create various challenges for the participants. Moreover, for the participants it can be difficult to strike a balance between family, work and leisure. Sometimes engagement with serious leisure can be expensive and time consuming which might be challenging for many people. In general, the findings show these challenges are diverse including gender discrimination, financial hardship, time limitation, overlap with work and even causing some conflicts with their family life. P10. We have lots of things going on, it’s just, you know we have been fighting really hard to be treated the same as the men, we used to not get referees, well we do, we used to not get as many games, now we do, so those are the sort of things. P9: Since the late 1980’s, I have started researching . . . I research all the old hotels around the Riverina, . . . and then out of that I’ve developed an interest in early settlement, the development of villages and things like that; gold mining in the early days. It is still something that I would do every day which is my passion. P12. Sometimes it is hard to have distance because it does cross into your work as well as your personal life . . . It’s about the distance. Sometimes you just have to do what’s expected of you and that sometimes that can be a little bit draining mentally. 4.1.4 Durable personal and social benefits. The fourth characteristic appears across a broad range of personal and social benefits of serious leisure ranging from pure enjoyment to selfexpression, satisfaction and social interaction. The findings indicate generally joyfulness was a dominant feeling. The majority of the participants highlighted the fact they have been involved with their leisure pursuits mainly because they enjoy it and they do not seek any other accomplishment beyond that pure pleasure and joy. P3: I did enjoy it, it was good fun, I really enjoyed the contact with the people and certainly the owners of the Farm are lovely people to work for. P7: We got an increase in local tournaments and participation and more people outdoors playing, you know, getting out and throwing balls and enjoying themselves and meeting people. Personal satisfaction was an evident theme which was frequently appeared in the dataset. The below excerpts demonstrate the personal and social benefits the participants experienced. The themes identified in this section can be categorised into some subcategories including: sense of achievement, social benefits, escaping from loneliness, pure enjoyment, philanthropy and altruism. P1: Just the satisfaction of seeing both people develop into their best, to be the best they can be and to see the station grow to become a service in the community that people are fond of and respect. So it’s really the satisfaction of seeing it work and seeing the people involved happily working within the environment. P4: It’s hard to say, I have not – I do not go into any competitions with it and I do not get any awards. It’s just personal satisfaction. Information activities in serious leisure 893 JD 77,4 894 P6: Well, there’s a lot of satisfaction in doing it. Particularly the – the home library thing. Sense of the achievement has always been one of the main motivations for serious leisure participants. The participants in this study frequently reported that their volunteering and hobbies bring a sense of fulfilment and accomplishment for them during all these years and it has been a sources of motivation and inspiration for them to continue their engagement. P3: I suppose when I reflect on my cycling I think, probably my major achievement is that I just continue to do it. . . . I’ve been in a few, a few events and finished them all satisfactorily in reasonable times. I’m not a high performance cyclist, and so I’ve never, I’ve never won any races, but always been satisfied in just participating and that sense of achievement of having done it and getting better all the time. 4.1.5 Unique ethos within a social world. The fifth category is about the unique ethos that gradually grows around the serious leisure activity and the participants accept it as a norm inside their subculture. An ethos works as a basis of a meaningful purpose and a source of passion and enthusiasm for the participants which encourages them to carry on their involvement in their chosen activity. P10: Because we’re very much of the ethos that if you come to join the group you should contribute to the group. So we would have people who say “I want to do this”, they come once, would not come again. Or we’d have people who would come, who would never sort of give anything back. P12: A lot of people think that yes it’s a weaving group and they’re going to learn how to weave in that instance but I always say to people you need to go slowly and listen, listen, listen and you listen to understand so it’s about actually sitting in the space and place of quietness and just being open to allowing things to happen rather than demanding. P18. I suppose a lifelong attitude or maybe a philosophy of mine has been an attitude to play your part and my dad always said you can back your community but I’ve always had a lifelong experience in learning and I mean a volunteering experience works both ways. Like I would love to pass on your skills and knowledge and having an education background that’s been part of the love of learning. 4.1.6 Personal and social identity. The sixth category is forming a sense of identity for the participants. The findings revealed they tend to identify strongly with their chosen hobby or voluntary job. They typically speak proudly about what they do and consider it as a worthwhile and meaningful dedication. Traditionally work, family or social status are main sources of social identity for people. However, serious leisure can also provide a good reputation and identity for the participants (Green and Jones, 2005). P8: My whole life I’ve worked in volunteering, it was a part of our family culture; as children we would often be working on community projects with my parents . . . as I went through high school . . . I started a youth drop-in centre . . . I think the way my parents raised me was that if you have the ability to help others, you must. . . . So, some just the culture I grew up in, some because they were issues close to my heart. P12. Well I’ll always be a weaver. You can never get away from that or a fibre based artist or whatever you want to call it, people always know you about that. 4.2 Part two: information activities Serious leisure is basically an information-intensive context in terms of the diversity and richness of information sources (e.g. online repositories and printed materials) and information activities (e.g. searching, browsing and sharing) – broadly described as information phenomena (Hartel, 2006, 2019). These information related activities are typically embedded into the various stages and aspects of serious leisure engagement (e.g. Hartel, 2003, 2006, 2010, 2014; Fulton, 2005; Prigoda and McKenzie, 2007; Lee and Trace, 2009; Case, 2010; O’Connor, 2013; Hartel et al., 2016; Price and Robinson, 2017; Hill and Pecoskie, 2017; Lloyd and Olsson, 2019). Moreover, in some arenas such as sports and performing arts (e.g. music or dance), where the main activity is performed with the body, embodied information play a key role (Cox et al., 2017; Cox, 2018; Lloyd and Olsson, 2019). Serious leisure participants often need specific information to follow their interests and they often passionately seek information about their hobbies and share the collected information with their peers in their own communities of interest or via social media for the larger audience in the public. As a result of this ongoing information seeking and sharing practice, serious leisure contexts are commonly information rich. Moreover, as they are keen to learn about their hobbies they normally visit information-rich hubs such as libraries, archives and museums. Meanwhile they need to develop their personal information management skills to organise the information they gather. As a result, they interact more with information resources, develop various information seeking skills and are more active in information sharing practice. The next section provides detailed findings about informational aspects of serious leisure in this study. 4.2.1 Sources of information. The study’s findings identified a range of information sources that participants typically use for their serious leisure purposes ranging from various online resources and tools on the Web (e.g. search engines, websites and social media) to public libraries, local newspapers and grey literature (e.g. government documents, flyers and etc.). The popular information resources are very diverse in this context and they usually use a combination of formal and informal resources both in the digital and print format. P1: . . . most of the information we work on or get is through either a regional community radio association . . . We get a lot of information from this Community Broadcasting Association to help us on governance and that type of thing. But the bulk of the information we get to go forward is through the community, what the community needs are and then to try and marry up the needs of the community to our broadcast service. P6: Because I had been away from Wagga; . . . and I came back and I did not have a great deal of contacts, other than a few family members. So, yes, I . . . found out through the local paper. Training was another source of information. Some of the participants have taken some training course such as workshops to learn new skills and knowledge they need for their serious leisure pursuits. P1: I did a bit of training a couple of, 18 months training on actually broadcasting, radio broadcasting. The bulk of what I do at the moment comes from my years as a senior executive in the corporate world. P3: And I have done training in, for the radio position. I did some accounting courses at university, and so I do have a basic accounting understanding. Based on the chosen hobby background knowledge is also usually useful for the participants. They can use their work-related skills in the leisure time as well. For example, they might use their business skills and expertise to manage their voluntary job. P1: So it works well because I can bring a level of business skill and expertise to the, to what would be by and large a community run identity and in return I get from that, the challenge of putting them on the straight and narrow getting them lined up with strategies and then putting them into practice and things like that. P9. Sometimes you’ll get reports from people like the Royal Australian Historical Society, the Federal Australian Historical Society, those sorts of things I’ll read and learn from. . . . It’s a very wide field, but more and more of its online; it’s knowing where to access that and how to access. Information activities in serious leisure 895 JD 77,4 896 The findings show the form of this training course can be face-to-face or online courses. These training courses provided them with both specific skills and knowledge they need to pursue their serious leisure (e.g. family history researching, bonsai growing skills, aboriginal heritage, culture and language) or general skills such as problem solving or time management. P9: I did a few online courses on basic family history researching. There’s a – you can do a course, either with a university in Tasmania, or there’s one in Scotland, they’re both very popular. . . . I’ve done one of those, and it was just a good little bit of background, but mostly, I just learn from experience as I go. P12: I think I’ve been training for it for my whole life it feels like it. But I have actually done the graduate certificate in Wiradjuri heritage, culture and language. P14: So we were involved in . . . which is a tree regeneration group and a desalination program there. So it was working together with other farmers to try and solve the problem of a rising salt water level in the soil and, so it involved being on the committee and talking with other people and problem solving. 4.2.2 Information seeking. The participants seek information through various sources. They usually prefer online information seeking because of its ease of access and the diversity of resources in the online environment. Nonetheless, they still use libraries and print materials for specific purposes. P9: I am a big fan of getting online . . . the first thing I do is get online and start reading what I can there, I’d use the library. . . . I go to their meetings, I get on their website, and they’ve got educational programs that you can do online. For the Society, I read webpages of other societies, minutes of other societies, I’ll Google how to make successful meetings, how to make a group successful, how to make members satisfied and things like that. I’ll Google that sort of material. P9. So, there’s a lot of online resources now, but then I use libraries, State Records, State Libraries – yeah, all those things – people. So, I do a lot of interviews and first-hand primary sources. 4.2.3 Information sharing. The finding indicates information sharing is the most popular and joyful information activity in this context. The participants use various methods for information sharing which can be categorised into two groups as formal and informal networks. The findings show that word of mouth has been one of the major sources of information sharing in the community. P1: Well going back about 17 years ago somebody was talking to me one day about how they were doing a broadcast on the community radio and I said, “That’d be neat.” And so they said, “Oh we need new presenters.” So I went along, . . . and had some training there and then went on air for, I did breakfast radio for 10 years . . . it was word of mouth more than anything. P9. . . . when I publish an article or a book, I’ll put it on the website, and I’ll publicise it through Facebook, and I reach a much wider audience, and there’s no risk with cost, and I do not have to muck around marketing or anything like that, so it’s just better all around. P3: . . . it’s a very informal process, it’s really just a matter of approaching the organisation . . . it’s just an informal contract, so I would suggest people do because you know you could tailor your own involvement to suit yourself. P3. Talking to people who are from out of Wagga and the fact that they were interested in the farm and wanting to understand, because it’s a hydroponic farm . . ., which was quite a new thing for a lot of people . . . I just enjoyed sharing my knowledge with people, and helping them to understand better what was involved. Social media is one of the main sources of access and sharing information for most of the participants. Some of them publish what they learn during their journey of serious leisure. P9: . . . that is personal satisfaction, and it provides a service, because people enjoy reading what I produce. I just put the articles up online now, and they are readily available . . ., so I get to reach more people through the medium of online, like Facebook, than if I were to publish them in hard copy. Meanwhile, social networking plays an important role in enhancing social connectedness and social inclusion to facilitate information sharing. P6: So, normally it’s just talking about it . . . anyone there that knows anyone that wants any, you know, say a home library thing, I – or this sort of thing, that’s where I get . . . most of the information. I think it’s what they call, women networking. P7: Okay, yeah I do a lot of research on the internet . . . so, network with people who have similar interests in other areas. For example, I’ve reached out to the . . . society and learnt things off them and I’ve also reached out to other bowling clubs, what they do, you know St Vincent De Paul shops, what they do. 4.2.4 Information usage and producing. Some of the participants have been actively involved in producing information about their serious leisure endeavours. A number of them have already published a number of publications about their achievements. P9: I’ve published – I cannot remember now, maybe six or seven books in hardcopy, and in the end I decided that it wasn’t worth the risk of whether – I worried about whether I sold them and whether I lost money on the deal and I’d have to market it, and now I’ve put them online, through Facebook and through the Society’s webpage. P16. As a club we publish a newsletter and I’ve published – I’ve written two articles for the newsletter so far. It used to be just the president that would write the newsletter but we’ve had a bit of change in how we’re organising the newsletter so in the last couple of years and now we’re getting our more experienced members to also contribute . . . we’re all sharing our experiences that way through the club newsletter. 4.3 Part three: motivations and barriers The findings show the participants have various sources of motivation and inspiration helping them to continue their passionate journey. These motivations are varied ranging from connection with like-minded people to helping others. The collected data confirmed participation in serious leisure activities can be very rewarding. The reward might be a positive feedback from people or having a sense of fulfilment because of successful contribution in a social project. The main motivations identified in the study include a number of themes such as: pure pleasure, self-satisfaction, escaping loneliness, social engagement, networking, altruism and benevolence. P18. I just enjoyed. I enjoy art and I thought that would be something really valuable to do when I have finished full time work. So that’s why I’ve got into it more. (Pure Pleasure) P14. That is really fun . . . we do sing for various things there. We sing for Alliance Francaise, we sing at . . . the Fusion Festival. . . . I just love to sing for the sake of singing so that’s probably my one really selfish thing probably. (Self-satisfaction) P6: Having returned from being away for so long, that’s the only way you’re going to get to know people. And also, otherwise, if you do not do it, you’re sitting at home, looking at four walls and probably going nuts, quite frankly. (Escaping loneliness) P17. I’ve chosen to continue with cricket because I enjoy it, it’s a very social sport and it’s good to meet people and make friends and all that kind of thing. (Social engagement) Information activities in serious leisure 897 JD 77,4 P10. When I came to Australia I learned about the clubs . . . I was new and I wanted to make friends, so I went and joined a club, because I love it, but also as a way to have a new social network. (Social networking) Altruism and helping others is an important motivation for the participants. They can help vulnerable people who are socially disadvantaged and try to improve their quality of life through a voluntary job in public places or charities. 898 P9. I realise that what I do in that regard is important for a lot of other people, and it makes material and things available to a lot of people, so it benefits the wider community, so I’m motivated by that. (Altruism) P12. I enjoyed working in that space but also too I could see it was improving the lives of others but also too it was providing an opportunity to – not an opportunity, what’s the word? It was a way of true reconciliation is when you walk side by side with one another and that’s what it felt like. (Benevolence) P6: The language cafe is a brilliant thing, because that brings in refugee and I think that helps them maybe settle in the area as well . . . most of the things I do – even though I’m fairly busy, I make time to do things like that, because I think they’re helping other people. So, it’s mentally stimulating for me. (Helping others) P7: . . . we’re doing oral history of people who are aged and for example, I’ve been going down to the old person’s home and speaking to them there on tape and getting a bit of history of . . . I’ve got a lot of positive feedback from that and with St Vincent De Paul just helping the socially disadvantaged. (Positive feedback) The findings is well-matched with previous research in terms of the social benefits of serious leisure. The data showed the participants enjoy the social benefits of their serious leisure activities very much. P3: And I enjoy very much interacting with all the people who came to the shop, and especially those who came as families, brought their children and wanted to pick their own strawberries . . . and seeing the children have such a great time and understanding actually where some of their food came from . . . also talking to people who are from out of Wagga and the fact that they were interested in the farm. P4: Well I mostly got involved with it because I wanted to meet other volunteers and I felt more connected to the community. Moreover, the findings revealed despite all the constructive aspects, this is not an entirely cheerful story all the time and the participants face some difficulties and hardships. However, it mainly depends on the nature of the activity. For example, a number of outdoor hobbies such as cycling, bushwalking and gardening mainly depend on the weather condition and the weather can be a hurdle for the participants during some periods of the year: P3. . . . the only barrier might be weather. It’s either too hot or too wet or something. P18. I suppose you have to be independent too – to have independence within your life situation and have the time. So if you do not have the time and then you do not have the transport to get to volunteering. I could see that would be more difficult and did not have the confidence to participate they would be real barriers to participation – lack of confidence, lack of time. Additionally, time pressure has always been an issue for most of the participants and it is becoming more important in nowadays hectic life when most people complain about shortage of time. In particularly, for some participants who work fulltime this is a bigger problem. P16. I would like to spend more time on it but it’s hard to actually say because some seasons like spring at the moment, tend to be a lot more intensive because the plants are actively growing whereas through winter most of the plants are dormant . . . so, through the spring, summer months, I’d probably been putting on average maybe 2, 3 hours a week but through the winter months you’d be lucky to do an hour a week. P3: Well it wasn’t so much a barrier but it was an impediment is that, when I offered my services to the owners of the strawberry farm they came to rely on me quite heavily. And towards the end of the season I was starting to think that I do not, I did not want to be devoting so much time. Information activities in serious leisure 899 5. Discussion The findings revealed that the participants in this study have been experiencing all the six qualities of serious leisure during their long-term engagement with their hobbies or voluntary jobs. As a result, their activities can be fully mapped onto the serious leisure perspective which was the main theoretical framework of the study. The findings also reconfirmed that serious leisure is a unique context in terms of the high level of intensity and huge diversity of information phenomena. This outcome was also well-matched with the previous research in this area (Lee and Trace, 2009; Savolainen, 2010; Cox and Blake, 2011; Hirsh et al., 2012; Margree et al., 2014; Joseph, 2016; Olsson and Lloyd, 2017; Price and Robinson, 2017; Bronstein and Lidor, 2020). All the participants actively seek, collect and share information to pursue their interests. Apart from individual information seeking, sometimes they engage in collective information practice (Prigoda and McKenzie, 2007) in their communities of interest such as weaving groups or bonsai growing clubs in this study. Also, along with information gathering and sharing, a few of them produce and publish information as well. What they do at this stage is a good example of creating information in the pursuit of a hobby (Fulton, 2016). Also, the findings confirmed they are passionate about their chosen activity and mostly experience a joyful information seeking to satisfy their information needs. Moreover, looking for information in this context is very much embedded in various activities they perform in their leisure time. For example, when a beginner bonsai grower is learning basic skills of bonsai growing (e.g. trimming, pruning and watering), she/he needs information to achieve this goal. However, information seeking is embedded in the whole process and might remain invisible for the person. Unless she/he reflects on the process. That is why at the end of the interviews most participants were pleased because attending the interview provided then with a chance to reflect on their experience. They felt amazed by the diversity of the information activities they usually carry out without even noticing it, mainly because of the enjoyment they experience in their hobbies. Nonetheless, participation in serious leisure is not always joyful. Sometimes it can be challenging in one way or another. The findings indicate that in some stages the participants struggle to continue their engagement. This is an issue that needs to be explored in future research because most studies in this area mainly focus on the positive aspects and ignore the negative sides. There are a number of contextual elements that need to be considered. For example, Orr (2006) reports that scholars overlook the issue of power and conflict in this context. While, these elements play significant roles. For instance, when there are many volunteers in an area of work, the professional staff might feel concerned that they might lose their job in a long term. As a result of this concern, they might shift to an “us and them” attitude and use their knowledge and expertise as a sources of power to limit the volunteers’ engagement. However, the positive outcomes of serious leisure both in the personal and social levels usually inspire the participants to maintain their involvement anyway. In particular, serious leisure plays a key role in enhancing social engagement. This is more important for vulnerable and isolated groups. Toepoel (2013) reports the oldest age group is the most socially isolated group and contribution in cultural activities has the most significant impact in boosting subjective measures of their social connectedness. Likewise, Cheng and Pegg (2016) report an JD 77,4 900 enduring engagement with serious leisure provides a powerful sense of wellness, happiness and a sense of worth for people. Moreover, serious leisure brings like-minded people together when they can share their stories and work as team members in specific projects. These activities establish a sense of community and boost social inclusion. Bronstein and Lidor (2020) found that a group of music fans seek information to accomplish at least four main purposes including the need for serious leisure, making social connections, having a sense of belonging and forming an identity. Likewise, the findings of the present study suggest the participants enjoy similar outcomes. They usually support one another in their communities of interests, similar to what Savolainen (2010) reports about informational and emotional support in the blogosphere. The findings also revealed that the participants are among very good friends of public libraries and they visit libraries regularly. Basically, libraries can support serious leisure and can be a source of reliable information for them. Besides, public libraries are social hubs and can provide people with facilities to advocate leisure activities. If we support serious leisure, it will bring some benefits for public libraries such as creating communities of interest, generating information grounds, enriching the library collections and promoting library programs and events (Mansourian and Bannister, 2019). Furthermore, the serious leisure perspective can be used by public libraries to audit their programing schedules (VanScoy et al., 2020). Therefore, there are mutual benefits for both libraries and serious leisure participants. 6. Conclusion This paper concludes that serious leisure is not only a source of personal satisfaction for the participants, it also can provide them with a sense of purpose in a meaningful and joyful journey towards self-actualization. It also can act like a social glue to keep people together in a community of interest. At the same time, information seeking and sharing play a key role in achieving these goals and the participants have a wide array of information sources and information sharing networks. These channels are very diverse ranging from informal networks (e.g. personal contacts, information grounds and social media) to formal resources (e.g. books, magazines and newsletters). They also share information through these passages with their peers in their communities of interests and various information grounds. Nonetheless, they face a number of hinders from time to time which make their journey difficult. Challenges such as time pressure and financial adversity are among the most common problems. Nonetheless, as they truly enjoy their chosen activity they have some coping strategies to overcome the difficulties. In terms of further research, there are still many unexplored corners about human information behaviour in this context. For example, our knowledge about the emotional aspects of information activities in serious leisure is still limited. Thus, some phenomenological studies based on the participants’ live experiences would be very useful. Moreover, we still need to discover more about the tools and techniques that serious leisure communities normally employ to produce and preserve information which gradually shape new knowledge depositories and digital heritage around their hobbies. Further research on these aspects of information phenomena in this context can shed light on the less explored corners of this topic. References Beaumont, E. and Brown, D.K. (2015), “Once a local surfer, always a local surfer: local surfing careers in a southwest English village”, Leisure Sciences, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 68-86. Bernard, H.R. and Ryan, G.W. (2010), Analysing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches, Sage, Los Angeles. Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006), “Using thematic analysis in psychology”, Qualitative Research in Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 77-101. Bronstein, J. and Lidor, D. (2020), “Motivations for music information seeking as serious leisure in a virtual community: exploring a Eurovision fan club”, Aslib Journal of Information Management. doi: 10.1108/AJIM-06-2020-0192. Information activities in serious leisure Bryman, A. (2004), Social Research Methods, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford. Bunea, E. (2020), “‘Grace under pressure’: how CEOs use serious leisure to cope with the demands of their job”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 11, p. 1453. Caldwell, L.L. (2005), “Leisure and health: why is leisure therapeutic?”, British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, Vol. 33 No. 1, pp. 7-26. Case, D.O. (2010), “A model of the information seeking and decision making of online coin buyers”, Information Research, Vol. 15 No. 4, available at: http://InformationR.net/ir/15-4/ paper448.html. Castleberrya, A. and Nolenb, A. (2018), “Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: is it as easy as it sounds?”, Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, Vol. 10 No. 6, pp. 807-815. Chen, K.Y. (2014), “The relationship between serious leisure characteristics and subjective well-being of older adult volunteers: the moderating effect of spousal support”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 119 No. 1, pp. 197-210. Cheng, E. and Pegg, S. (2016), “If I’m not gardening, I’m not at my happiest: exploring the positive subjective experiences derived from serious leisure gardening by older adults”, World Leisure Journal, Vol. 58 No. 4, pp. 285-297. Cheng, E., Stebbins, R. and Packer, J. (2017), “Serious leisure amongst older gardeners in Australia”, Leisure Studies, Vol. 35 No. 4, pp. 505-518. Cox, A.M. (2018), “Embodied knowledge and sensory information: theoretical roots and inspirations”, Library Trends, Vol. 66 No. 3, pp. 223-238. Cox, A. and Blake, M.K. (2011), “Information and food blogging as serious leisure”, ASLIB Proceedings, Vol. 63 Nos 2-3, pp. 204-220. Cox, A., Griffin, B. and Hartel, J. (2017), “What everybody knows: embodied information in serious leisure”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 73 No. 3, pp. 386-406. Dillette, A.K., Douglas, A.C. and Andrzejewski, C. (2019), “Yoga tourism – a catalyst for transformation?”, Annals of Leisure Research, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 22-41. Fulton, C. (2005), “Finding pleasure in information seeking: leisure and amateur genealogists exploring their Irish ancestry”, Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 42 No. 1, pp. 1-12. Fulton, C. (2016), “The genealogists’ information world: creating information in the pursuit of a hobby”, Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 85-100. Fulton, C. (2017), “Urban exploration: secrecy and information creation and sharing in a hobby context”, Library and Information Science Research, Vol. 39 No. 3, pp. 189-198. Gainor, R. (2008), “Leisure information behaviours in hobby quilting sites”, Masters in Library Science, Department of Library and Information Studies, University of Alberta. Gorichanaz, T. (2017), “There is no shortcut: building understanding from information in ultrarunning”, Journal of Information Science, Vol. 43 No. 5, pp. 713-722. Green, C. and Jones, I. (2005), “Serious leisure, social identity and sport tourism”, Sport in Society, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 164-181. Hartel, J. (2003), “The serious leisure frontier in library and information science: hobby domains”, Knowledge Organization, Vol. 30 Nos 3-4, pp. 228-238. Hartel, J. (2006), “Information activities and resources in an episode of gourmet cooking”, Information Research, Vol. 12 No. 1, available at: http://InformationR.net/ir/12-1/paper282.html. 901 JD 77,4 902 Hartel, J. (2010), “Managing documents at home for serious leisure: a case study of the hobby of gourmet cooking”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 66 No. 6, pp. 847-874. Hartel, J. (2014), “An interdisciplinary platform for information behaviour research in the liberal arts hobby”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 70 No. 5, pp. 945-962. Hartel, J. (2019), “Turn, turn, turn”, Proceedings of CoLIS, the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Vol. 24 No. 4, Information Research, Ljubljana, available at: http://InformationR.net/ir/24-4/colis/colis1901.html. Hartel, J., Cox, A.M. and Griffin, B.L. (2016), “Information activity in serious leisure”, Information Research, Vol. 21 No. 4, available at: http://InformationR.net/ir/21-4/paper728.html. Hershkovitz, A. and Hardof-Jaffe, S. (2017), “Genealogy as a lifelong learning endeavour”, Leisure, Vol. 41 No. 4, pp. 535-560. Hill, H. and Pecoskie, J.J.L. (2017), “Information activities as serious leisure within the fanfiction community”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 73 No. 5, pp. 843-857. Hirsh, S., Anderson, C. and Caselli, M. (2012), “The reality of fantasy: uncovering information-seeking behaviors and needs in online fantasy sports”, CHI’12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 849-864. Iwasaki, Y. (2007), “Leisure and quality of life in an international and multicultural context: what are major pathways linking leisure to quality of life?”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 82, pp. 233-264. Jones, I. and Symon, G. (2001), “Lifelong learning as serious leisure: policy, practice, and potential”, Leisure Studies, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 269-283. Joseph, P. (2016), “Australian motor sport enthusiasts’ leisure information behaviour”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 72 No. 6, pp. 1078-1113. Kim, J., Brown, S.L. and Yang, H. (2019), “Types of leisure, leisure motivation, and well-being in university students”, World Leisure Journal, Vol. 61 No. 1, pp. 43-57. Kim, J., Yamada, N., Heo, J. and Han, A. (2014), “Health benefits of serious involvement in leisure activities among older Korean adults”, International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 1-9. Kono, S., Ito, E. and Gui, J. (2020), “Empirical investigation of the relationship between serious leisure and meaning in life among Japanese and Euro-Canadians”, Leisure Studies, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 131-145. Lee, C. and Payne, L.L. (2016), “Experiencing flow in different types of serious leisure in later life”, World Leisure Journal, Vol. 58 No. 3, pp. 163-178. Lee, C.P. and Trace, C.B. (2009), “The role of information in a community of hobbyist collectors”, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 60 No. 3, pp. 621-637. Lee, K. (2020), “Serious leisure is social: things to learn from the social world perspective”, Journal of Leisure Research, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 77-87. Lee, K. and Ewert, A. (2019), “Understanding the motivations of serious leisure participation: a selfdetermination approach”, Annals of Leisure Research, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 76-96. Lee, S., Bae, J., Im, S., Lee, S. and Heo, J. (2019), “Senior fashion models’ perspectives on serious leisure and successful aging”, Educational Gerontology, Vol. 45 No. 10, pp. 600-611. Liu, H. and Yu, B. (2015), “Serious leisure, leisure satisfaction and subjective wellbeing of Chinese university students”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 122, pp. 159-174. Lloyd, A. and Olsson, M. (2019), “Untangling the knot: the information practices of enthusiast car restorers”, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 70 No. 12, pp. 1311-1323. Mansourian, Y. (2020), “How passionate people seek and share various forms of information in their serious leisure”, Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, Vol. 69 No. 1, pp. 17-30. Mansourian, Y. and Bannister, M. (2019), “Five benefits of serious leisure for a public library”, Incite, Vol. 40 Nos 5-6, pp. 32-33. Margree, P., MacFarlane, A., Price, L. and Robinson, L. (2014), “Information behaviour of music record collectors”, Information Research, Vol. 19 No. 4, available at: http://InformationR.net/ir/19-4/ paper652.html. Ocepek, M.G., Bullard, J., Hartel, J., Forcier, E., Polkinghorne, S. and Price, L. (2018), “Fandom, food, and folksonomies: the methodological realities of studying fun life-contexts”, Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 55 No. 1, pp. 712-715. Olsson, M. and Lloyd, A. (2017), “Losing the art and craft of know-how: capturing vanishing embodied knowledge in the 21st century”, Information Research, Vol. 22 No. 4, available at: http:// InformationR.net/ir/22-4/rails/rails1617.html. O’Connor, L.G. (2013), “The information seeking and use behaviors of retired investors”, Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, Vol. 45 No. 1, pp. 3-22. Orr, N. (2006), “Museum volunteering: heritage as ‘serious leisure’”, International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 194-210. Phillips, P. and Fairley, S. (2014), “Umpiring: a serious leisure choice”, Journal of Leisure Research, Vol. 46 No. 2, pp. 184-202. Pi, L., Lin, Y., Chen, C., Chiu, J. and Chen, Y. (2014), “Serious leisure, motivation to volunteer and subjective well-being of volunteers in recreational events”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 119, pp. 1485-1494. Price, L. (2017), “Serious leisure in the digital world: exploring the information behaviour of fan communities”, Doctoral dissertation, City University of London. Price, L. and Robinson, L. (2017), “Being in a knowledge space: information behaviour of cult media fans”, Journal of Information Science, Vol. 45 No. 5, pp. 649-664. Prigoda, E. and McKenzie, P.J. (2007), “Purls of wisdom: a collectivist study of human information behaviour in a public library knitting group”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 63 No. 1, pp. 90-114. Rampley, H., Reynolds, F. and Cordingley, K. (2019), “Experiences of creative writing as a serious leisure occupation: an interpretative phenomenological analysis”, Journal of Occupational Science, Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 511-523. Robinson, J. and Yerbury, H. (2015), “Re-enactment and its information practices: tensions between the individual and the collective”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 71 No. 3, pp. 591-608. Ross, C.S. (1999), “Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure”, Information Processing and Management, Vol. 35 No. 6, pp. 783-799. Sanchez, J. (2020), “Investigating basketball Twitter: a community examination of serious leisure information practices”, Doctoral dissertation, The State University of New Jersey, Rutgers. doi: 10.7282/t3-t04p-1m48. Savolainen, R. (2010), “Dietary blogs as sites of informational and emotional support”, Information Research, Vol. 15 No. 4, available at: http://www.informationr.net/ir/15-4/paper438.html. Seale, C., Gobo, G., Gubrium, J.F. and Silverman, D. (2007), Qualitative Research Practice, Sage, London. Shupe, F.L. and Gagne, P. (2016), “Motives for and personal and social benefits of airplane piloting as a serious leisure activity for women”, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Vol. 45 No. 1, pp. 85-112. Siegenthaler, K.L. and O’Dell, I. (2003), “Older golfers: serious leisure and successful aging”, World Leisure Journal, Vol. 45 No. 1, pp. 45-52. Sirgy, M.J., Uysal, M. and Kruger, S. (2017), “Towards a benefits theory of leisure well-being”, Applied Research Quality Life, Vol. 12, pp. 205-228. Stebbins, R.A. (1982), “Serious leisure: a conceptual statement”, Pacific Sociological Review, Vol. 25, pp. 251-272. Information activities in serious leisure 903 JD 77,4 Stebbins, R.A. (2001), “Serious leisure”, Society, Vol. 38 No. 4, pp. 53-57. Stebbins, R.A. (2009), “Leisure and its relationship to library and information science: bridging the gap”, Library Trends, Vol. 57 No. 4, pp. 618-631. Toepoel, V. (2013), “Ageing, leisure and social connectedness: how could leisure help reduce social isolation of older people?”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 113 No. 1, pp. 355-372. 904 Tsaur, S. and Liang, Y. (2008), “Serious leisure and recreation specialization”, Leisure Sciences, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 325-341. VanScoy, A., Thomson, L. and Hartel, J. (2020), “Applying theory in practice: the serious leisure perspective and public library programming”, Library and Information Science Research, Vol. 42 No. 3, 101034. Veal, A.J. (2017), “The serious leisure perspective and the experience of leisure”, Leisure Sciences, Vol. 39 No. 3, pp. 205-223. Vesga Vinchira, A. (2019), “Modelling the information practices of music fans living in Medellın, Colombia”, Information Research, Vol. 24 No. 3, available at: http://InformationR.net/ir/24-3/ paper833.html. Zhou, L., Chlebosz, K., Tower, J. and Morris, T. (2020), “An exploratory study of motives for participation in extreme sports and physical activity”, Journal of Leisure Research, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 56-76. Appendix Data Collection tool: Interview Protocol (1) What is/are the serious leisure activity/activities that you are involved in? (2) How long have you been involved in this practice? (3) How did you learn about it in the first place? (4) In average how much time do you spend for your leisure weekly? (5) What are your motivations to spend time in this context? (6) What are your main sources of information? (7) How do you usually search your required information for this hobby? (8) Do you publish your stories and reflections about this hobby in any media? (9) Are you member of a society or association related to this subject? (10) Have you done any training for this activity? (11) How do you categorise information related to this interest? (12) What are your main achievements in this field so far? (13) How do you share information about this interest? (14) Do you use social media for sharing relevant information? (15) What is the best advantage of spending time on this interest? (16) What is your recommendation for people who would like to take part in this activity? (17) What are your main barriers and obstacles in this context? (18) How do you predict your future involvement in this field? (19) Is there anything else that you would like to add? About the author Yazdan Mansourian is a lecturer in the School of Information Studies at Charles Sturt University (CSU) in Australia. He received his PhD in Information Science from The University of Sheffield (2003–2006). Yazdan has a BSc degree in Agricultural Engineering (1991–1995) from Guilan University and an MA degree in LIS from Ferdowsi University of Mashhad (1998–2001). During January 2007 to June 2017 he was faculty member at Kharazmi University. Yazdan joined CSU in 2017 and currently his main research interest is human information behaviour in serious leisure. He explores the role of joy in engaging people with hobbies, amateurism and voluntary activities and how joyful leisure experiences inspire the participants to seek, share and use information. Yazdan Mansourian can be contacted at: ymansourian@csu.edu.au For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Information activities in serious leisure 905