Frostbite: Evaluation, Treatment, and Management

advertisement

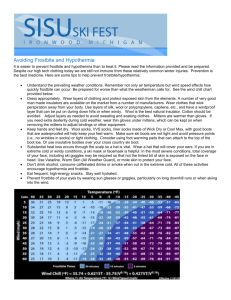

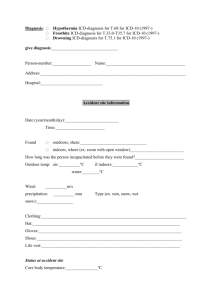

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Frostbite Authors Hajira Basit1; Tanner J. Wallen2; Christopher Dudley3. Affiliations 1 Brookdale University 2 Creighton University School of Medicine 3 Emory University Last Update: June 27, 2022. Continuing Education Activity Frostbite, also known as freezing cold injury is tissue damage that occurs due to cold exposure, occurring at temperatures below zero degrees celsius. Homeless populations, children, and the elderly are especially vulnerable to frostbite. Prolonged duration and lower temperatures increase the risk of frostbite and the extent of the injury. Certain pre-existing conditions, including peripheral vascular disease, malnutrition, Raynaud's disease, diabetes mellitus, and tobacco use may worsen frostbite-related tissue damage. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of frostbite and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition. Objectives: Identify the epidemiology of frostbite. Summarize how to evaluate a patient for frostbite. Review the treatment and management options available for frostbite. Explain interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination and communication to advance treatment and prevention of frostbite, in turn leading to better patient outcomes. Access free multiple choice questions on this topic. Introduction Frostbite, also known as freezing cold injury (FCI) is tissue damage as a result to cold exposure, occurring at temperatures below 0 degrees C. It is included in a spectrum of injury, from FCI to non-FCI and frostnip.[1] Any portion of exposed skin is prone to the damaging effects of frostbite. Patients are at high risk for ischemic tissue injury and necrosis. Patients that survive cold tissue injury are prone to secondary infection and dehydration from loss of the skin barrier. Frostbite tend to occur when the body is exposed to intense cold, resulting in vasoconstriction. The resulting decrease in blood flow fails to deliver heat to the tissues and eventually leads to ice crystal formation. Body parts most prone to frostbite include the feet, hand, ears, lips, and nose. Most cases of frostbite occur in the winter; homeless people and those who perform outdoors activity are most susceptible to the injury. The goal of treatment is to salvage as much tissue as possible so that maximal function remains. Etiology Skin exposure to freezing conditions causes frostbite. Prolonged duration and lower temperatures increase the likelihood and the extent of the injury. Certain pre-existing conditions may worsen tissue injury because of frostbite, including peripheral vascular disease, malnutrition, Raynaud's disease, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, etc. A unifying pattern among these conditions is poor impaired internal organ insulation or dysfunctional vasculature. Risk factors for frostbite include: Winter season No or inadequate shelter from the cold High wind chill factor Exposure at a high altitude Prolonged duration of exposure Prolonged exposure to a wet condition Altered mental status Alcohol or drug abuse Malnutrition Immobilization Extremes of age Homeless Presence of medical disorders like diabetes, hypothyroidism, peripheral vascular disease, stroke or arthritis Smoker Epidemiology Classically, frostbite injuries were common in military personnel. However, with the increase in technology and accessibility, recreational sports have become a significant repository for frostbite cases. Homeless populations, children, and the elderly are especially vulnerable to frostbite. Risk factors include behavioral (lack of clothing, alcohol/drug consumption, access to shelter), physiological (dehydration, high altitudes, hypoxia), and other comorbidities with a predilection for tissue hypoxia (diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, Raynaud phenomenon). [1] Pathophysiology Frostbite has a prejudice for distal extremities, digits, and those portions of exposed skin with decreased perfusion (nose, ears) and less insulation. As the temperature of exposed skin drops, endothelial cell damage can cause localized edema in the extremity. Hyperviscous intravascular flow and vasodilation causes slowing forces, resulting in microthrombi. The constellation of microvascular injury, venous stasis, and microthrombi all contribute to the development of ischemia attributed to frostbite. Depending on the extent of the exposure and subsequent cellular damage, injuries may be reversible or irreversible. Normal skin blood flow is about 250 ml/min but during frostbite, the flow drops to less than 20-50 ml/min. As the temperature drops to below 0 degrees Centigrade, blood flow ceases. The slower venous system freezes before the arterial system. Frostbite causes injury in the following ways: Direct damage of the cold to the tissues Indirect damage caused by dehydration Formation of ice crystals that leads to alteration in electrolytes and lipid layers Stasis of the microvessels leading to thrombus formation and ischemia Reperfusion injury Recovery Frostbite injury is classified into three zones which include: 1. Zone of coagulation which is the most distal and often the most severely injured. Here the injury is irreversible 2. Zone of stasis is the middle zone where the injury can be moderate to severe. but it reversible. 3. Zone of hyperemia is the proximal zone, which is the least injured. In most cases, recovery from frostbite can take 5-30 days, depending on the severity of injury. Histopathology Initially, extracellular ice crystals form in exposed tissue. Continued cold exposure can cause intracellular ice crystals to form. Cell membrane damage results in electrolyte imbalances. As the transmembrane osmolarity gradient increases, cell membranes can rupture, resulting in cell death. Should tissue thawing occur, a reperfusion-associated inflammatory response through proinflammatory cytokines may cause additional tissue damage. Even more dangerous, additional cycles of thaw-refreeze can cause progressively worsening tissue ischemia and subsequent thrombosis.[2] History and Physical History of the patient should include duration and external temperatures during exposures. Physical examination may reveal blanched, white skin. Patients may complain of heaviness in an exposed extremity as numbness progresses. In later stages of frostbite, exposed areas may become dark or purplish in hue due to poor vascular tone and pooling of blood. Superficial frostbite affecting the epidermis and subcutaneous fat will have pale, white blisters upon rewarming. Deep, full-thickness frostbite will become hemorrhagic with rewarming and may become gangrenous.[3] Injured skin may be well-demarcated with surrounding viable skin. It is important to know that the initial exam will not accurately reveal the final depth and extent of the injury. Rewarming injury During rewarming, edema may start to appear within 3-5 hours and may last 7 days. Blisters tend to appear within 4-24 hours. Presence of eschar will be obvious at 10-15 days and mummification with a line of demarcation may develop in 3-8 weeks. Evaluation Frostbite is a clinical diagnosis. Using additional laboratory testing may be helpful in determining the extent to which comorbid conditions may be contributing to tissue ischemia. Technetium-99 (Tc-99) triple phase scanning and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may help to determine extent of amputation in the first few days after injury.[4][5] Tc-99 bone imaging may also assist in determining candidacy for tPA.[6] Treatment / Management Patients should have protection from further injury by covering exposed areas. The care of patients with frostbite begins with rewarming in the field if there is no anticipation of refreezing, as thaw-refreezing may worsen injuries.[3] Remove patients from the wind. Remove wet clothing and replace with dry clothing. Avoid vigorous rubbing as this can cause further damage.[7] In-hospital management includes warm water baths, approximately 40-42 degrees C. Patients with systemic hypothermia should be managed by raising core temperature above 35 degrees C using warm IV fluids, and this should precede warming of the affected extremity.[7] This rewarming protocol also includes patients with other comorbidities or significant trauma. NSAIDS (ibuprofen) are indicated for controlling pain and preventing further inflammation, but stronger analgesics including narcotics may be necessary to achieve pain control. Frequent re-examination for sensation should accompany rewarming. Although controversial, some sources recommend drainage or excision on white, cloudy-appearing blisters, while hemorrhagic blisters should be left intact. As with burn patients, particular care to prevent infections and dehydration should be a priority. Overly aggressive surgical debridement may remove skin that is otherwise viable, so complete rewarming should be achieved before surgical debridement. Signs of compartment syndrome (edema, pulselessness, extreme pain) should prompt urgent surgery. Delayed amputation (up to 6 weeks following injury) until the determination of tissue viability may prevent surgical morbidity from unnecessary procedures.[8][9] Patients with full-thickness injuries and evidence of ischemia and no restoration of tissue perfusion after rewarming may be candidates for thrombolytic (tPA) therapy.[10] tPA may reduce the need for digital amputation.[11] Combination therapy with tPA and IV heparin may also reduce the need for digital amputation.[6] Iloprost, a potent vasodilator, has been used as a potential treatment to prevent ischemia in frostbite.[3] IV Iloprost is unavailable in the United States. Differential Diagnosis Careful assessment for systemic hypothermia and full-thickness tissue injury are essential in patients with apparent frostbite. Failure to correct for underlying comorbidities associated with frostbite (i.e., intoxication, cardiovascular compromise, significant environmental exposure, trauma) may cause systemic collapse and death. Staging Traditionally, frostbite has a staging system similar to burns: First degree - numbness, central pallor, surrounding erythema/edema, desquamation, dysesthesia Second degree - skin blistering with surrounding erythema/edema Third degree - tissue loss involving entire thickness of skin, hemorrhagic blisters Fourth degree - tissue loss involving deeper structures, resulting in loss of the affected part Another classification based on frostbite on hands/feet has been proposed, which incorporate early imaging studies and may better predict outcomes.[12] Grade 1 - no cyanosis on the extremity; no risk of amputation or sequelae predicted Grade 2 - cyanosis on distal phalanx only; amputation to soft tissue and sequelae of fingernail/toenail sequelae predicted Grade 3 - cyanosis on intermediate and proximal phalanges; amputation to the bone of the digit and functional sequelae predicted Grade 4 - cyanosis over carpal/tarsal bones; amputation to limb and functional sequelae predicted. With this classification system, as grade increases, so does the likelihood of limb amputation. Prognosis Functional sequelae of frostbitten areas depend on the extent of tissue injury.[12] Unfavorable factors in frostbite include hemorrhagic blistering, non-blanching cyanosis, and firm skin after rewarming.[3] Patients should avoid cold exposure for up to a year after the initial injury. Frostbite injury is associated with morbidity which is worse in the presence of the following: Presence of hemorrhagic blisters No edema Ongoing mottling Frank presence of frozen tissue Complications of frostbite include: Paresthesias Loss of nails Anhidrosis of hyperhidrosis Cracked skin Atrophy of muscles Chronic pain Joint stiffness Phantom pain Tremor Complications Frostbite survivors may have an intolerance to cold in previously frostbitten areas, which may be a consequence of vasospasm and abnormal autonomic tone following cold injury. Complex regional pain syndrome is a common complication.[10] Autoamputation of an affected digit may precede surgical amputation. Deterrence and Patient Education Risk modification including proper clothing, access to shelter, and maintaining hydration and nutrition are vital for protection against frostbite.[7] Patients should be advised to keep clothing as dry as possible and to wear multiple layers if they foresee cold exposure. Alcohol consumption should be discouraged. Emollients, although traditionally believed in Nordic countries to prevent frostbite, do not have protective effects in preventing frostbite and should be discouraged.[13] Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes Frostbite is a very common problem during winter and is associated with high morbidity. Because any part of the body can be affected, the condition is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the emergency department physician, internist, wound care nurse, and a surgeon. A multimodal approach to the treatment of patients with frostbite may provide the best chance for functional recovery.[1] The key is patient education; frostbite in many instances can be prevented. Patients should be advised to dress well during winter, carry extra clothing supplies if they are into winter sports and avoid tight restrictive clothing. The nurse should advise against the use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. For those with medical problems. it is important to ensure that their health is stable before venturing on an outdoors trip during winter. Early consultation with the surgical services specializing in frostbite is crucial. During recovery from frostbite, as with other traumatic injuries with an expected loss of, function, consultation with rehabilitation services is vital, including wound care, physical therapy, occupational therapy, physical medicine & rehabilitation specialists, among others. Finally, one should not immediately recommend amputation. The aim is to salvage all viable tissue. Thus, a wound care nurse should follow the patient and only debride infected superficial dead skin and let the damaged skin slough off on its own. Open communication with the interprofessional team is the key so that all patients receive the optimal standard of care. Outcomes The outcomes after frostbite injury are guarded and depend on the extent of the injury. Most people tend to have some residual deficits; either sensory or functional. Review Questions Access free multiple choice questions on this topic. Comment on this article. References 1. Imray CH, Oakley EH. Cold still kills: cold-related illnesses in military practice freezing and non-freezing cold injury. J R Army Med Corps. 2005 Dec;151(4):218-22. [PubMed: 16548337] 2. Rintamäki H. Predisposing factors and prevention of frostbite. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2000 Apr;59(2):114-21. [PubMed: 10998828] 3. Roche-Nagle G, Murphy D, Collins A, Sheehan S. Frostbite: management options. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008 Jun;15(3):173-5. [PubMed: 18460961] 4. Cauchy E, Marsigny B, Allamel G, Verhellen R, Chetaille E. The value of technetium 99 scintigraphy in the prognosis of amputation in severe frostbite injuries of the extremities: A retrospective study of 92 severe frostbite injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2000 Sep;25(5):969-78. [PubMed: 11040315] 5. Barker JR, Haws MJ, Brown RE, Kucan JO, Moore WD. Magnetic resonance imaging of severe frostbite injuries. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Mar;38(3):275-9. [PubMed: 9088467] 6. Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005 Dec;59(6):1350-4; discussion 1354-5. [PubMed: 16394908] 7. Handford C, Buxton P, Russell K, Imray CE, McIntosh SE, Freer L, Cochran A, Imray CH. Frostbite: a practical approach to hospital management. Extrem Physiol Med. 2014;3:7. [PMC free article: PMC3994495] [PubMed: 24764516] 8. Hallam MJ, Cubison T, Dheansa B, Imray C. Managing frostbite. BMJ. 2010 Nov 19;341:c5864. [PubMed: 21097571] 9. Woo EK, Lee JW, Hur GY, Koh JH, Seo DK, Choi JK, Jang YC. Proposed treatment protocol for frostbite: a retrospective analysis of 17 cases based on a 3-year single-institution experience. Arch Plast Surg. 2013 Sep;40(5):510-6. [PMC free article: PMC3785582] [PubMed: 24086802] 10. Sheridan RL, Goldstein MA, Stoddard FJ, Walker TG. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 41-2009. A 16-year-old boy with hypothermia and frostbite. N Engl J Med. 2009 Dec 31;361(27):2654-62. [PubMed: 20042758] 11. Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, Cochran A, Edelman LS, Saffle JR. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007 Jun;142(6):546-51; discussion 551-3. [PubMed: 17576891] 12. Cauchy E, Chetaille E, Marchand V, Marsigny B. Retrospective study of 70 cases of severe frostbite lesions: a proposed new classification scheme. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001 Winter;12(4):248-55. [PubMed: 11769921] 13. Lehmuskallio E. Emollients in the prevention of frostbite. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2000 Apr;59(2):122-30. [PubMed: 10998829] Figures Frostbite to fingers/hands. Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, Winky (CC by 2.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC. This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, a link is provided to the Creative Commons license, and any changes made are indicated. Bookshelf ID: NBK536914 PMID: 30725599