Chinese Exclusion Act & Gentleman's Agreement: A Comparison

advertisement

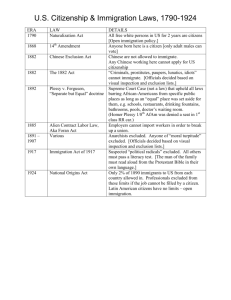

The Chinese Exclusion Act: a template to the Gentleman’s Agreement? Introduction From the second half of the 19th century and throughout the 20th the United States experienced massive influxes of immigrants from around the world, mainly the Asian continent. The promise of employment, the dire conditions at home and the developing relations with the countries (produced by an active US foreign policy), were the main causes which brought thousands to leave their countries, at times permanently, in search of a better future. Asian immigration history in America is considered to be a controversial topic because of the policies adopted by the US government in face of anti-Asian sentiments growing across the nation. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, passed by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur, was the first in the history of the United States to prevent a whole ethnicity and national group to enter the country because of the perceived threat to the economy, culture and American racial homogeneity. In 1907, the Gentleman’s Agreement between the United States and Japan was signed to prevent further immigration of Japanese labourers, in an attempt to alleviate tensions between the two Pacific powers and appease the antiJapanese wave spreading across the western states. For years both policies have been used as evidence for the racist and nationalistic nature of US immigration policy. The Chinese Exclusion Act and the racial rhetoric which came with it have been claimed to work as a template for later US immigration policy and its dealings with new immigrant groups. The literature, however, has lacked in-depth comparative analysis, as it has never delved in the examination of a particular group. Because of this, in this essay I will examine the claim by looking at Japanese immigration in particular, and the policy used to control it; in an attempt to understand how much the Exclusion Act influenced the Gentleman’s Agreement, evaluating their similarities and differences. While both policies were born to limit asian immigration and were undoubtedly, in part, the product of anti-Asian sentiments, I will argue that 1 what brought them about, their fundamental elements, were entirely different, contending with the conventional view that the Exclusion Act served as a template for the Gentleman’s Agreement. Literature Review In her essay, “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924," Erika Lee argues that the Chinese Exclusion Act was to become the template of US immigration policies throughout the rest of the 19th and 20th century. She makes this claim based on the rhetoric used for the Exclusion Act and how this had been applied to other immigrant groups throughout the rest of the century. Furthermore, Lee addresses the more practical aspects of the Chinese Exclusion Act by looking at the development of operational procedures and the birth of immigrant documentation measures. In doing this, Lee explores how these initial practices have been used for 20th century American immigration policy, underscoring the argument of the Exclusion Act being the fundamental structure on which later US immigration policies have been built on.1 Beth Lew-William’s essay “Before Restriction Became Exclusion: America’s Experiment in Diplomatic Immigration Control” advances a thorough argument over the real impact and importance of the 1882 Exclusion Act on Chinese immigration and later US immigration policy. Lew-William’s argues that the 1882 document, which was referred to by its contemporaries as the Chinese Restriction Act (not Exclusion Act), was not in fact the great “watershed”2 in American immigration policy commonly believed to be: the real template for “twentieth-century expansion of gatekeeping in America”3 came rather six years later in the 1888 Chinese Exclusion Act. It was 1Lee, Erika. “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924.” Journal of American Ethnic History 21, no. 3 (March 2002). Beth Lew-Williams, “Before Restriction Became Exclusion: America's Experiment in Diplomatic Immigration Control,” Paci c Historical Review 83, no. 1 (February 2014): 53. 2 Ibid, 54. 2 fi 3 fascinating for me to analyse this essay as it ultimately points out some flaws in the language and historical analysis of Erika Lee’s article which I had formerly analysed. In his article The “‘Gentlemen’s’ Agreement –Exclusion by Class” Michael Patrick Cullinane advances an argument discarding the racist nature of the Gentlemen’s agreement between the United States and the Japanese. In doing so the author moves the focus on President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the signatory of the agreement, rather than on the American public. Cullinane argues that Roosevelt thought of the Japanese as “highly civilised people”4 and that racial discrimination “did not play the most substantial part in framing [his] decision”5. Instead, he advances an argument claiming Japanese exclusion was undertaken on a classist basis rather than on a racial one, underlining how the President believed the Japanese working class to be the main cause of concern in the coastal states, rather than the Japanese people per se. These three articles vary considerably between them in regards to their usefulness for the development of my paper. Lee’s and Cullinane’s article are extremely well developed, supported by efficient evidence of both primary (transcripts, letters, newspaper articles) and secondary nature. The two articles provide different and at times opposite views in regards to the argument I’m trying to explore. The advancements constructed in Lee’s essay are undoubtedly useful for my paper as they specifically address the impact of the Exclusion Act and the racist rhetoric which arose from it on later American immigration policy. Cullinane’s paper is also effective as it focuses on the Gentleman’s Agreement and explores its causes, ultimately advancing findings which are in opposition to Lee’s, adding depth and perspective to my research. Nonetheless, the current literature does at times lack in the information needed for my research. I found Lee’s essay to concentrate solely on the racial rhetoric which moved American Cullinane, Michael Patrick, “The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement – Exclusion by Class,” Immigrants & Minorities 32, no. 2 (January 2014): 144. 4 5 Ibid, 145. 3 immigration policy, in some ways omitting other factors which could have influenced the latter. Also, Lee’s concerns are very broad: by regarding various 20th century immigrant groups in America, Lee does not delve deep enough in the immigration policies towards other Asian immigrant groups (Japanese and Korean) and abstains from presenting a full picture of their determinants. In a similar way, while Cullinane does directly address the causes of the Gentleman’s Agreement, by advancing, for example, how class played a more important role than race, his article does not specifically refer to the Exclusion Act or provides actual arguments relating to its influence or lack of it on the immigration policies taken towards the Japanese group. Lastly, while Lew-William’s essay does a great deal in showing the more complex reality of the “traditional narrative of Exclusion”6, it unfortunately does not pertain my research. What it does, in a way, is add more complexities to it: it undermines the actual importance of the 1882 Restriction document, shifting the spotlight on the 1888 Exclusion Act as the true template used in future US gatekeeping policy. The thesis of my paper challenges Lee’s argument on how the Exclusion Act worked as a template for all following American immigration policy. While I do not look at 20th century US immigration policy in its entirety, in the following pages I underscore how the argument does not hold when applied to the Japanese immigrant group and the policies employed towards it. Furthermore, my paper widens and explores more in depth some aspects of Cullinane’s article such as the reasons for the Japanese Agreement: Cullinane focuses on Roosevelt’s character and his class-based worries, I will develop these points and explore additional factors which have moved the creation of this policy. 6 Beth Lew Williams. “Before Restriction Became Exclusion”. 26. 4 Analysis Since the start of the California Gold Rush in 1848 and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, thousands of Chinese laborers immigrated to the United States in search of wages higher than the ones at home. While at first welcomed by the respective industries for their provision of cheap labor, the decline in the fortunes of the Gold Rush and the consequent increase in competition caused their American peers to revolt against them (this can be seen in the institutionalising of the Foreign Miners Tax), pushing thousands to search for work in western coast cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles. As the Chinese immigrant problem was brought to the wider urban context, citizens accused the Chinese of lowering their wages, ‘stealing’ their employment opportunities and posing a threat to American culture because of the perceived immorality, corruption and anti-Western attitude as seen in crime-ridden Chinatowns. The growth in antiChinese sentiment was helped by local newspapers, such as the San Francisco Chronicle, which article, “The Chinese Invasion! They Are Coming, 900,000 Strong,” promoted an extremely unfavourable image of the group. The Chinese Exclusion Act came as a consequence of widespread anti-Chinese sentiment, fomented by both the working class and the western political elite, in “defense of American Labor”7 and the “self-preservation”8 of the ‘American’ race. In her article The Chinese Exclusion Example, Lee argues how the Exclusion Act represented the great “watershed”9 in US immigration policy as it introduced the “gatekeeping”10 ideology which, according to Lee, was adopted in regards of immigrant groups which followed. Lee claims that the Chinese exclusion provided not only the legal architecture, but also the rhetoric with which to “further racialize”11 other undesirable aliens. These prejudices, applied to the immigrant 7 “Chinese Exclusion Convention”, The San Francisco Call, November 20th, 1901. 8 Lee, “The Chinese Exclusion Example.” 37. 9 Ibid, 37. 10 Ibid, 37. 11 Ibid, 42. 5 groups, encompassed the feared “fecundity”12 of the latter which would have brought about the “race suicide”13 of America. Furthermore, they took more gender related aspects: this can be noted in the 1875 institutionalisation of the Page Act, a document which forbade the entry of lower-class women because of their possible participation in prostitution, and whose underlying gender-based nature was later utilized in the Exclusion Act. Moreover, Lee asserts that the Chinese appearance was used to determine and define the admissibility of new immigrants from Europe, Mexico, and Asia in regards to their “yellowness.”14 Ultimately, Lee argues that the racist rhetoric used by antiChinese activists to institutionalise the Exclusion Act was later applied to new immigrant groups. For example, while keeping from truly delving in the Japanese context, she does mention this new group in regards to its seemingly identical racialization as that of the Chinese. Lee argues that Japanese immigration was judged by western coast citizens as yet another “oriental invasion,”15 considered to be threats due to their “race and their labor.”16 Furthermore, Lee explains how the Japanese were “especially feared”17 because of their agricultural proclivity and their tendency to settle permanently, rather than staying temporarily as the Chinese immigrants would do. As evidence for the similarity in the attributes moving the exclusion of the two immigrant groups, the author quotes San Francisco newspapers which warned how the “Japanese [were] taking the Place of the Chinese.”18 Additionally, Lee compares the speech endings of Denis Kearney, a major leader in anti-asian activism, who’s 1870 speech ended with “The Chinese Must Go!”19 and 1892 speech 12Lee, “The Chinese Exclusion Example,” 43. 13Gabaccia, Donna. “Is Everywhere Nowhere? Nomads, Nations, and the Immigrant Paradigm of the United States History,” Journal of American History, 86, 3, (1999): 1115-1134. 14 Ibid, 43. 15 Lee, “The Chinese Exclusion Example,” 44. 16 Ibid, 44. 17 Ibid, 44. 18 Ibid, 44. 19 Ibid, 45. 6 with “The Japs Must Go!”20; these quotes work to show the blatant adaptation of anti-Chinese rhetoric in regards to the Japanese and how the problems posed by the two groups were found to be “synonymous to each other.”21 Ultimately, Lee argues that the “political and cultural ideology” adopted by anti-Chinese activists and politicians who promoted for exclusion was re-adapted in regards to the Japanese immigrant group. The second argument made by Lee is on technical measures institutionalised for the successful implementation of the Exclusion Act. In her article Lee argues that the Exclusion Act introduced “standard means of inspecting, processing, admitting, tracking, punishing, and deporting immigrants in the United States.”22 Moreover, Lee supports her claim by referencing the systematisation of a “trained force of government officials”23 in charge of inspecting and controlling Chinese immigration; in addition, the author mentions the creation of a “system of registration documents, certificates of identity, and voluminous interviews”24 which was to become “central to America’s control of immigrants” in the twentieth century. Lastly, Lee references how the Exclusion Act set another precedent by “defining illegal immigration as a criminal offence,”25 leading to the establishment of the first American laws on deportation, which were to be used on later immigrant groups. Lee’s argument is thorough, and while it does not reference Japanese immigrants, it is correct in its claim that the Exclusion Act brought about new methods for the successful implementation of immigration policies which were used during the 20th century. I disagree with part of Lee’s argument regarding the re-adaptation of anti-Chinese rhetoric towards the new Japanese group. Although it is undoubtedly true that a racist rhetoric moved both 20 Lee, “The Chinese Exclusion Example,” 45. 21 Ibid, 45. 22 Ibid, 53. 23 Ibid, 53. 24 Ibid, 53. 25 Ibid, 55. 7 Chinese and Japanese immigration policy, I find a problem with the concept of the ‘adaptation.’ Were anti-Japanese activists actively trying to adapt the racist rhetoric to a new group, or did the Japanese immigration simply bring back these sentiments? Ultimately, both immigrant groups were seen as threats to the job market and American culture. In this line of thought we might say that the same rhetoric was used for both the Chinese and the Japanese. However, this does not make the Exclusion Act a template for the Gentleman’s agreement, but simply an immigration policy moved by the same underlying rhetoric, as seen in most immigration policies in history. Furthermore, relating to Lee’s argument on the technical measures introduced for the successful implementation of the Exclusion Act, while it is true that these methods have been used and re-adapted throughout the 20th century, the non-formal nature of the Gentleman’s agreement of which I will talk about, made it so that these immigration measures had not to be officially applied by the US government, but rather by a “Japanese-administered system” which had to stop the immigrants before they reached America, further underlining how the Exclusion Act and the technical measures created for its execution were not openly and formally adopted in regards to Japanese immigration at the start of the 1900’s. One of the most significant points in support of my argument regards the reasons why the the two immigration policies were undertaken and the respective objectives for which they were implemented. On October 9th, 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education adopted a policy of segregation which brought the exclusion of Japanese students from public schools and into ‘Oriental Schools’. This act was promoted by the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League on the basis of the Asian threat to the cultural and moral upbringings of American children; and, according to historian Raymond Esthus, it started “the most serious diplomatic crisis that had yet risen in Japanese-American relations.”26 When words of this injustice had reached the Japanese 26 Esthus, Raymond A. Theodore Roosevelt and Japan. 128. 8 government it was met with “the deepest offence,”27 as it was enacted by US government officials and it blatantly indicated “racial hostility”28 on their part. Furthermore, the Japanese government saw the act as challenging the Japanese-American Treaty of 1894 which amended a most-favourednation clause in regards to Japan. Japanese government officials argued that by segregating Japanese students, the action violated their rights of “residence and travel”29 amended by the 1894 treaty. The situation between the two countries escalated when Japan hinted at possible retaliation and President Roosevelt talked about taking “steps to prepare for war”30. In face of these escalations, Roosevelt understood the issue could “be resolved only by striking at the basic cause of the Pacific coast agitation”31 which seemed to be the “increasing flux of Japanese of the labouring class into the United Stated.”32 In only the twelve months before November 30, 1906, “seventeen thousands”33 Japanese immigrants entered the mainland United States: these numbers showed that the only way to alleviate tensions between the two great powers was to “prevent all immigration of Japanese laboring men - - that is, of the Coolie class - - into the United States.”34 From this conception sprouted the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907, which settled that the segregation order by the San Francisco School Board was to be rescinded, and that the Japanese government was to withhold passports of Japanese laborers directed to mainland United States. From the analysis of what caused the Gentleman’s Agreement, we can note the integral difference between the latter and the Exclusion Act. While the Exclusion Act was a direct consequence of Ambassador Wright to Secretary of State Root, telegram, October 21, 1906, S. D. File 1797. Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Part 2. 27 28 Esthus, Raymond A. Theodore Roosevelt and Japan. 137. 29 Ibid, 143. 30 Ibid, 140. 31 Ibid, 144. 32 Ibid, 144. 33 Ibid, 146. 34 Theodore Roosevelt to Victor Metcalf, November 27, 1906, Library of Congress. 9 widespread anti-Chinese sentiment in regards to their threat to the economy and American culture; the Gentleman’s Agreement was concocted to alleviate tensions between two countries which administration’s respected each other, as seen in multiple of Roosevelt’s writings, such as “I am utterly disgusted at the manifestations….in favour of excluding the Japanese exactly as the Chinese are excluded.”35 In fact, it appears that the Gentleman’s Agreement was rather an attempt to ultimately end the injustices imposed on the Japanese immigrants, by having to take the drastic decision of limiting the presence of the latter group in the pacific coast. Consequently, this goes to further undermine the argument which regards the Chinese Exclusion Act as a template for the immigration policies adopted to deal with the Japanese, as they were undertaken in different spirits: one of exclusion arising from strong, racist sentiment, the other for exclusion as the only means to sedate and properly manage these sentiments. Another argument which challenges the notion of the Exclusion Act being the template for the Gentleman’s agreement concerns the main figure of the Japanese-American immigration issue: President Roosevelt. In his article The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement – Exclusion by Class, author Michael Cullinane argues that what the agreement tried to undertake was not exclusion on a racial basis; rather, exclusion on a classist one. To do this, Cullinane argues that Roosevelt was not prejudiced towards the Japanese people on a racist base, regarding them “highly civilised people”36 and confessing he was “keenly mortified that any Americans should insult”37 them. To further support this argument Cullinane explains how the Japanese civilisation represented, in Roosevelt’s eyes, the embodiment of the three inter-related qualities which constitute good-character: “unselfishness, moral righteousness and self-control.”38 Moreover, Cullinane openly disagrees with Erika Lee’s argument that Roosevelt was advocating for the promotion of a “White Pacific where 35 Theodore Roosevelt to Henry Lodge, May 15, 1906. Library of Congress. 36 Cullinane, “The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement – Exclusion by Class.” 144. 37 Ibid, 144. 38 Ibid, 143. 10 white supremacy would be maintained in the face of an ascendant Japan”39; the author argues that while Roosevelt did fear the growing power of the Japanese Empire, he respected the efforts which brought it to its position and never thought of contending it through a racially fomented community of nations. On the other hand, what Cullinane argues moved Roosevelt to implement his immigration policies was, after the “state of geopolitics”40, a desire to exclude not all the Japanese, rather, the Japanese laboring class. Roosevelt believed the Japanese working class to be the “element that stoked domestic racial discrimination”41 because of the competition it represented in the American job market. In Roosevelt’s view, while the “ ‘Japanese Gentleman’ could get on perfectly well with the ‘American Gentleman’ ”42, the “American workingmen…will object in the most emphatic way to Japanese laborers coming among them in any number.”43 This argument can be supported by the fact that large part of the anti-Japanese sentiment stemmed from the western coast working class, and that the Japanese gentlemen, such as the aristocracy, tourists, students and merchant class were “allowed to enter”44 as they did not be settled “in mass”45 and did not represent a threat to the American working class. Ultimately, the author does not deny that racism in the west coast was very present in brining about Japanese immigration policy. However, he finds the significance of the Gentleman’s agreement as lying in its true classist nature, rather than the racist one. This argument goes against the notion that the Chinese Exclusion Act influenced the Gentleman’s Agreement by asserting the true motives of Roosevelt, which actively tried to not replicate the racially-animated Chinese exclusion in regards of the Japanese immigrants, but rather, 39 Cullinane, “The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement – Exclusion by Class,” 14. 40 Ibid, 141. 41 Ibid, 148. 42 Theodore Roosevelt to Edward Grey, December 18, 1906, Library of Congress. 43 Theodore Roosevelt to Edward Grey, December 18, 1906, Library of Congress. 44 Cullinane, “The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement – Exclusion by Class,” 149. 45 Ibid, 154. 11 prevent further discontent and agitation in the West Coast by decreasing the numbers of Japanese laborers. The last point I want to explore is on the informal essence of the Gentleman’s agreement. The major difference between the Exclusion Act and the 1907 American immigration policies on Japanese immigrants is precisely the unofficial quality given to the accord between the two countries. The Chinese exclusion was implemented in a strongly executive fashion, through the formulation of an official document approved by all sectors of the US administration, and forcefully implemented through the creation of immigration-focused governmental organisations and the development of multiple technical measures. This differs widely from the Gentleman’s agreement, which, as I stated before, was an informal accord between two countries, never officialized through the development of a legitimate treaty document. This undoubtedly goes to show the enormous difference in the two policies: how could the Exclusion Act be considered the template for the Gentleman’s agreement, if this last one lacked both the rigidity and the coded formality of the former? The very titles of the two policies show their differences: one was a one-sided amended federal law, the other an informal arrangement between the two nations. However, it could be argued that the informal nature of the gentleman’s agreement was only kept for matters of convenience, and that the true motives behind it were as forceful and imposed as the Exclusion Act. In his work The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement Esthus explores the more undisclosed aspects of the Gentleman’s agreement: the negotiations which happened before its arrangement. From the start of the crisis, Esthus notes, President Roosevelt and Secretary of State Eliuh Root embarked on a “concerted effort to wring an immigration treaty from Japan.”46 These efforts, however, were destined to be unsuccessful because of the disagreement between the two countries over the terms of the treaty. While the Japanese foreign minister Hayashi was inclined to accept an official treaty, 46 Esthus, Raymond A. Theodore Roosevelt and Japan. 157. 12 he believed that the one proposed by the US administration was to “one-sided.”47 Hayashi believed that the acceptance of a treaty which excluded Japanese laborers in return for school privileges would have faced serious outcry from the Japanese public, which believed that these rights were already possessed under the treaty of 1984. Consequently, in face of the developing crisis, Hayashi proposed the acceptance of these treaty terms in exchange of a clause on naturalisation which would have granted “Japanese not within the excluded class entering the United States” the right to gain American citizenship. He made this “quid pro quo”48 proposal largely to preserve the “amour propre”49 of the Japanese government and its people, which were staunchly against the surrender of their country to the United States on an intrinsically racially discriminatory basis. While at first naturalisation was seen by Roosevelt as a possible term for negotiation, he soon realised that congress would have never approved of the clause, which blatantly opposed the Californian antisentiment it was attempting to appease, considering it, as understood by Hayashi: “impossible at this juncture”50. Furthermore, Esthus explains how the mutual exclusion of laborers amended by the possible treaty further found its criticism in the United States, who’s opposition argued the fundamentally classist nature of the exclusion would have “violated the principle of equality”51 of American citizens; additionally, they defended the right of the United States to control its own schools even if it meant “forfeiting friendly relations with Japan.”52 For all these reasons, which mainly arose out of national pride, a formal treaty was never agreed upon by the two countries, and, consequently, a more informal, unobtrusive arrangement was amended: the Gentleman’s agreement. 47 Esthus, Theodore Roosevelt and Japan, 158. 48 Ibid, 158. 49 Ibid, 158. 50 Ibid, 163. 51 Ibid, 159. 52 Hochi Shimbun, Feburary 2 and 3, 1907 as quoted in Theodore Roosevelt and Japan. 13 By looking at the negotiating aspects behind the final arrangement, we could assert that the Gentleman’s agreement was a more efficient and less troubling way to come to terms between the two countries. It might be argued that this was not an agreement after all, but rather, it was an unofficial act which pushed for a more American-sided arrangement without testing Japanese national pride and underscoring its “sluggish diplomacy.”53 This understanding would underline a similarity between the the Exclusion Act and the Gentleman’s agreement in as much as both promoted a very American, one-sided policy, disregarding the interests and rights of the immigrant groups and their respective nations. Nonetheless, I don’t think this to be correct: the Exclusion Act was blatantly a policy concerned only with American interests, treating the Chinese government as an inferior and easily-disregarded entity. On the other hand, the Gentleman’s agreement and its negotiations not only showed the respect the American administration had for the Japanese one, trying in every way not to offend the latter, but it also provided an amble agreement were the inadmissible racial segregation of the Japanese was corrected, and in the same way the antiJapanese was alleviated by limiting the number of immigrating laborers in mainland US. This goes to show that the American self-interest and disregard for the Chinese government found in the Exclusion Act, was not as slightly present in the dealings previous to the formation of the Gentleman’s agreement. The ingrained differences between the two policies make the claim that the Exclusion Act worked as a template for US immigration policy in regards to the Japanese group unfounded. The very reasons for the adoption of Japanese exclusion were to prevent further agitation against Japanese immigrants, as a way to alleviate the growing tensions between the two pacific superpowers. On the other hand, Chinese exclusion had been from the very start a one-sided policy, formulated to prevent the entry of Chinese immigrants because of their threat to the economy, culture and American well being. Furthermore, by looking at the motives for which Roosevelt 53 Hochi Shimbun, Feburary 2 and 3, 1907 as quoted in Theodore Roosevelt and Japan. 14 undertook the arrangement, we have seen how the Gentleman’s Agreement aimed at excluding the Japanese working class, while the Exclusion Act was a far more racially centred document, showing that what actually moved the two policies were completely different factors. Moreover, after having revised the negotiations of the agreement between the two nations we can come to the conclusion that while the United States was certainly trying to sedate the anti-Japanese sentiment on the western coast, it did so in total respect of the Japanese nation, attempting to give them what they deemed as rightful under the 1984 treaty by undertaking drastic exclusionary policies. US immigration policies have been of great impact on its relations with Asia; because of this, only by understanding the differences in the policies adopted and avoiding their generalisation we can truly comprehend the dynamics which have shaped the relations between the US and Asian countries throughout the 19th and 20th century, 15 Bibliography Primary Sources Ambassador Wright to Secretary of State Root, telegram, October 21, 1906, S. D. File 1797. Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Part 2. <https://history.state.gov/ historicaldocuments/frus1906p2>. Accessed Dec. 12, 2019. The San Francisco call. (San Francisco [Calif.]), November 20, 1901. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/ sn85066387/1901-11-20/ed-1/seq-2/>. Accessed Dec. 13, 2019. Theodore Roosevelt to Edward Grey, December 18, 1906. Roosevelt’s Letters. Library of Congress. <https://www.loc.gov/search/?in=&q=roosevelt&new=true&st=>. Accessed Dec. 13, 2019. Theodore Roosevelt to Henry Lodge, May 15, 1906. Roosevelt’s Letters. Library of Congress. <https://www.loc.gov/item/mss382990014/> Accessed Dec. 14, 2019. Theodore Roosevelt to Victor Metcalf, November 27, 1906. Roosevelt’s Letters. Library of Congress. <https://www.loc.gov/search/?in=&q=metcalfe&new=true&st=> Accessed Dec. 14, 2019. Secondary Sources Lee, Erika. “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924.” Journal of American Ethnic History 21, no. 3 (March 2002): 36–62. <https:// www.jstor.org/stable/27502847>. Lew-Williams, Beth. “Before Restriction Became Exclusion: America’s Experiment in Diplomatic Immigration Control.” Pacific Historical Review 83, no. 1 (February 2014): 24–56. <https:// www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525> 16 Cullinane, Michael Patrick. “The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement – Exclusion by Class.” Immigrants & Minorities 32, no. 2 (January 2014): 139–61. <https://doi.org/10.1080/02619288.2013.860688> Esthus, Raymond A. Theodore Roosevelt and Japan. 2nd ed. Seattle and London : University of Washington Press, 1967. Gabaccia, Donna. “Is Everywhere Nowhere? Nomads, Nations, and the Immigrant Paradigm of the United States History,” Journal of American History, 86, 3, (1999): 1115-1134. 17