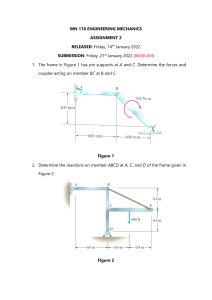

2023 INDEX OF edited by Dakota L. Wood © 2023 by The Heritage Foundation 214 Massachusetts Ave., NE Washington, DC 20002 (202) 546-4400 | heritage.org All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 978-0-89195-308-1 edited by Dakota L. Wood We are honored to dedicate the 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength to Senator James M. Inhofe (R–OK) Contents Contributors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix Acknowledgments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xi Preface. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xiii Kevin Roberts, PhD Introduction.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Executive Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 AUKUS: New Opportunities for the United States and Its Closest Allies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23 Peter Jennings Recruiting the All-Volunteer Force: New Approaches for a New Era.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37 Richard Brady Determining the Real Cost of the Tools of War. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53 John G. Ferrari, Major General, U.S. Army (Ret.) Global OperatingEnvironment Assessing the Global Operating Environment.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67 Europe. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69 Daniel Kochis Middle East. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 Nicole Robinson Asia. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159 Jeff Smith, Dean Cheng, Bruce Klingner, and Walter Lohman Conclusion: Scoring the Global Operating Environment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 Assessing Threats to U.S. Vital Interests. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197 China.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201 Dean Cheng Russia. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223 Alexis Mrachek Iran. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 261 James Phillips North Korea. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 293 Bruce Klingner Non-State Actors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 301 James Phillips and Jeff Smith Conclusion: Global Threat Level.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 315 U.S. Military Power An Assessment of U.S. Military Power.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 321 U.S. Army. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335 Thomas W. Spoehr U.S. Army Modernization Table.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 349 U.S. Navy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 361 Brent D. Sadler U.S. Navy Modernization Table. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 378 U.S. Air Force.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 397 John Venable U.S. Air Force Modernization Table. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 416 U.S. Marine Corps. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 433 Dakota L. Wood U.S. Marine Corps Modernization Table. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 444 Threats to U.S. Vital Interests U.S. Space Force. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 455 John Venable U.S. Space Force Modernization Table. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 469 U.S. Nuclear Weapons.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 481 Patty-Jane Geller Missile Defense. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 507 Patty-Jane Geller Cyber Warfare and U.S. Cyber Command. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 527 James Di Pane Conclusion: U.S. Military Power.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 533 Glossary of Abbreviations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 537 Methodology.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 551 Senator James M. Inhofe (R–OK). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 557 Contributors Heritage Experts Dakota L. Wood is Senior Research Fellow for Defense Programs in the Center for National Defense, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation. He served for two decades as an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps, including service as a strategic analyst for the Commandant of the Marine Corps and the Secretary of Defense’s Director of Net Assessment. Thomas W. Spoehr, Lieutenant General, U.S. Army (Ret.), is Director of the Center for National Defense. Before joining The Heritage Foundation, he served America for more than 36 years in the U.S. Army. Frederico Bartels is a former Senior Policy Analyst for Defense Budgeting in the Center for National Defense. Before joining The Heritage Foundation, he served for three years as a Policy Analyst with Concerned Veterans for America. Dean Cheng is a former Senior Research Fellow in the Asian Studies Center of the Davis Institute. He specializes in China’s military and foreign policy. Maiya Clark is a Senior Research Associate in the Center for National Defense. She focuses on the military industrial base. Luke Coffey is a former Director of the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy of the Davis Institute at the time he contributed to this edition of the Index. He joined Heritage after service as Senior Special Advisor to the Secretary of State for Defence of the United Kingdom. James Di Pane is a Policy Analyst in the Center for National Defense. He focuses on military cyber and the U.S. Coast Guard and manages production of the Index of U.S. Military Strength. Patty-Jane Geller is a Senior Policy Analyst in the Center for National Defense. Her work addresses nuclear deterrence and missile defense. Bruce Klingner is Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia in the Asian Studies Center. He served for two decades at the Central Intelligence Agency and the Defense Intelligence Agency. Daniel Kochis is Senior Policy Analyst in European Affairs in the Davis Institute’s Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom, where he specializes in trans-Atlantic security issues including NATO, U.S.–Russia relations, and the Arctic. Walter Lohman is a former Director of the Asian Studies Center. He has served on the staff of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, in the office of Senator John McCain, and as Executive Director of the U.S.–ASEAN Business Council. Alexis Mrachek is a former Policy Analyst for Russia and Eurasia in the Allison Center. James Phillips is Senior Research Fellow for Middle Eastern Affairs in the Allison Center. He has also served at the Congressional Research Service and at the East–West Center. Nicole Robinson is a Senior Research Associate in the Allison Center. She specializes in Middle East matters. Brent D. Sadler is Senior Research Fellow for Naval Warfare and Advanced Technology in the Center for National Defense. He retired from the U.S. Navy as a captain and served for 26 years as a submarine officer aboard multiple nuclear submarines and in various senior posts including Naval Attaché, Malaysia, and Senior Advisor to the Chief of Naval Operations. Jeff Smith is Director of the Asian Studies Center. He specializes in South Asia, has authored and contributed to several books on Asian security matters, and formerly served as Director of Asian Security Programs at the American Foreign Policy Council. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military ix John Venable is Senior Research Fellow for Defense Policy in the Center for National Defense. A 25-year veteran of the U.S. Air Force and F-16 pilot, he served in three combat operations, was commander of the Thunderbirds, and earned the rank of colonel before retiring. External Reviewers and Expert Contributors Richard Brady, Colonel, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret.), is CEO of the American Society of Military Comptrollers. John G. Ferrari, Major General, U.S. Army (Ret.), is a Nonresident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Peter Jennings is a Senior Fellow at and former Executive Director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Robert Soofer, PhD, is Senior Associate (Non-resident), Missile Defense Project, at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Any views presented in or reflecting the results of any prepublication review of this document by an officer or employee of the United States government are rendered in his or her individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States government or any agency thereof. x 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Acknowledgments T to account for changes in content delivery as our world becomes increasingly digital, portable, and driven by social media, and the guidance and coordination provided by Director of Research Editors Therese Pennefather ensured the creation of a cohesive finished product. We believe that this Index helps to provide a better-informed understanding and wider appreciation of America’s ability to “provide for the common defence”—an ability that undergirds The Heritage Foundation’s vision of “an America where freedom, opportunity, prosperity, and civil society flourish.” The Index continues to be cited and referenced across government—by Congress, the executive branch, and officials within the Department of Defense and supporting government agencies—as well as the media, academia, and policy institutes and among the public. We remain encouraged that so many Americans are similarly concerned about the state of affairs in and the multitude of factors affecting our country. The Heritage Foundation seeks a better life for Americans, and this requires a strong economy, a strong society, and a strong defense. To help measure the state of the economy, Heritage publishes the annual Index of Economic Freedom; to help guide Congress in its constitutional exercise of the power of the purse, Heritage scholars analyze federal spending across all sectors of the economy and put forward recommendations throughout the year that, if implemented, would make Members of Congress better stewards of the taxes paid by all Americans; and to help Americans everywhere more fully understand the state of our defenses, our Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy is publishing this ninth annual edition of the Index of U.S. Military Strength. In addition to acknowledging all of those who helped to prepare this edition, very special recognition is due to the Heritage members and donors The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military xi he Index of U.S. Military Strength is truly a team effort. This edition includes the work of 20 authors, an amazing research editor, two extraordinarily talented graphics specialists, designers and marketing specialists and web-design/digital content experts, and a handful of very bright interns— Conner Bolanos, Jackson Clark, Aaron Eudaimon, and Grace Hermanson—who assisted with the research and tabulation of budget and acquisition data that make the service capability tables possible. But among the members of this team, there are a few special contributors who go the extra mile and make the Index a remarkable and uniquely special undertaking. James Di Pane, Policy Analyst in the Center for National Defense, extended his winning streak in shepherding production of the 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength. He worked with everyone involved to make this Index a reality, both in print and on the web. Senior Editor William T. Poole is a force of nature in the world of editing, each year using his ability to maintain a consistent tone, impeccable accuracy, and a fresh approach to conveying essential information throughout this multi-author document to enhance the excellent work produced by our authors. Data Graphics Services Manager John Fleming continued his impressive work in giving visual life to text and statistics to convey a message with maximum impact, working with the authors to explore more creative ways to convey important information. Research Editor and Paper Production Specialist Kathleen Scaturro again used her proofreading skills to ensure a high-quality final product. Graphic Designer Grace DeSandro created the cover image for this year’s Index. Senior Designer and Web Developer, Research Projects, Jay Simon and Senior Digital Strategist Augusta Cassada Irvine ensured that the presentation of Index materials was tuned whose continued support has made this 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength possible. Finally, as we do each year, The Heritage Foundation expresses its enduring appreciation to the members of the U.S. armed forces who continue to protect the liberty of the American people in an ever more challenging world. xii 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Preface T destroyer, and the KC-46 tanker must never happen again. Wasteful spending on unnecessary programs to push the military to go “green” (which will cost $3 billion in 2023) must be curtailed. Less effort should be placed on critical race theory and diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in favor of increasing readiness. A strong U.S. military is all the more important because America’s existential threat—the People’s Republic of China—is expanding its strength and global influence with the cunning of serpents. The Chinese Communist Party has spent the past three decades methodically leveraging Western elites’ decadence and compromising American institutions to its own strategic advantage. China has invested in an arsenal of missiles designed to target U.S. warships, has upgraded its fleet of fighter jets, and is fielding advanced equipment that is rivaling the U.S. military’s in quality. U.S. intelligence experts gauge that China has surpassed the U.S. in hypersonic missiles, space systems, and naval shipbuilding. It has initiated a massive increase in its nuclear capabilities. We should remember Vladimir Putin and Ukraine when thinking of China and Taiwan. America’s adversaries have shown a willingness to do more than simply invest in capabilities; they have also shown a willingness to use them. Even if China had no hard military power, its rancid ideological ambitions, demographic urgency, and institutionalized technological aggression would make it our most dangerous adversary. That the Chinese navy is adding the equivalent of the entire British navy every year in new warships, is developing missiles designed to target U.S. warships, is upgrading its fleet of fighter jets, and now fields an army 50 percent larger than our own adds an exclamation point to the fact. This Index of U.S. Military Strength, composed by experts who have studied these areas for decades, The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military xiii he Russia–Ukraine War of 2022 shocked many from the complacency that suggested conventional war was a thing of the past. Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has reminded many countries of the global threats that remain and has caused several to begin to rebuild their national defenses. It’s a message the U.S. should heed as well. U.S. foreign policy has tended to oscillate between an overreliance on internationalism to remake the world to America’s liking and an urge to isolate ourselves behind our oceans. Neither policy is appropriate for American interests. The American people want—and deserve—a new approach to global leadership: policies that draw lessons from our realist and idealist traditions but apply those lessons narrowly to American interests rather than elite fantasies. The world is more dangerous today than it has ever been. A strong military and effective strategies to project military strength to friend and foe alike are not luxuries, but necessities. Times change; human nature does not. In global affairs, as on street corners, ideals like justice, freedom, and human dignity, however true, are ultimately only as strong as their enforcers. If America is going to remain free, safe, and prosperous, it requires the military power necessary to ensure that its adversaries would never dare to challenge it on the battlefield. The leaders of Russia and China understand this. In Washington, American “strength” is too often, and lazily, solely measured by military spending— as if courage, lethality, technology, and ingenuity were budget line items themselves rather than the byproducts of intelligent budgeting and inspiring leadership. If the U.S. military is going to regain its preeminence, the Pentagon must act to be both more focused and more efficient. Procurement disasters such as the Littoral Combat Ship, the Zumwalt-class effort too with tariffs, sanctions, economic and institutional disengagement from Chinese agents—and closer ties to Pacific allies. We are in a new era, against a new enemy, wielding and deflecting new weapons. But the fight remains the same: to protect the American people, our interests, and our unique constitutional freedoms from oppressive tyrannies abroad and elite complacency and entitlement here at home. In this fight, as ever, success is not a battle to win, but a choice to make. provides an unvarnished assessment of the U.S. military. In many cases, the reports are troubling. The U.S. Army is the smallest it has been since 1940. The Air Force is the smallest and oldest it has been since its inception. The Navy is nowhere near its goal of 350 ships and is retiring more ships than it is building. We need to do not simply more, but better to check Beijing’s ambitions. A strong and modern military is not enough. Congress must finally close the soft-power gap, reclaim information and technological supremacy—and end the high-tech piracy on which China has built its economic and military power. We should deploy economic policy in the xiv 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Kevin Roberts, PhD, President The Heritage Foundation October 2022 Introduction T Soft approaches cost less in manpower and treasure than military action costs and do not carry the same risk of damage and loss of life, but when the United States is confronted by physical threats to its national security interests, it is the hard power of its military that carries the day. In fact, the absence of military power or the perception that one’s hard power is insufficient to protect one’s interests will frequently—and predictably—invite challenges that soft power is ill-equipped to address. Thus, hard power and soft power are complementary and mutually reinforcing. An insufficiency of either damages the other and ultimately jeopardizes the country’s future. The decline of America’s military hard power, historically shown to be critical to defending against major military powers and to sustaining operations over time against lesser powers or in multiple instances simultaneously, is thoroughly documented and quantified in this Index. It is harder to quantify the growing threats to the U.S. and its allies that are engendered by the perception of American weakness abroad and doubts about America’s resolve to act when its interests are threatened. The anecdotal evidence is consistent with direct conversations between Heritage scholars and high-level diplomatic and military officials from countries around the world: The aging and shrinking of America’s military forces, their reduced presence in key regions since the end of the Cold War, and various distractions created by America’s domestic debates have created a perception of American weakness that contributes to destabilization in many parts of the world, prompts old friends to question their reliance on America’s assurances, and spurs them to expand their own portfolio of military capabilities. While stronger allies are generally a boon for U.S. security and economic interests, allies that are less tied to U.S. security assurances reflect The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 1 he United States maintains a military force primarily to protect the homeland from attack and to protect its interests abroad. Other uses—assisting civil authorities in times of emergency, for example, and maintaining the perception of combat effectiveness to deter enemies—amplify other elements of national power such as diplomacy or economic initiatives, but America’s armed forces exist above all else so that the U.S. can physically impose its will on an enemy and change the conditions of a threatening situation by force or the threat of force. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of U.S. Military Strength gauges the ability of America’s military to perform its missions in today’s world and assesses how the condition of the military has changed during the preceding year. The Index is not meant either to predict what the U.S. military might be able to do in the future or to accord it efficacy today based on the promise of new technologies that are in development rather than fielded and proven in use. It is a report to American citizens on the status of the military that they join, that they support, and on which they depend. The United States prefers to lead through “soft” elements of national power—diplomacy, economic incentives, and cultural exchanges—but soft power cannot ultimately substitute for raw military power. When soft approaches like diplomacy work, their success often owes much to the knowledge of all involved that U.S. “hard power” stands ready, however silently, in the diplomatic background. In similar fashion, countries seek an economic relationship with the United States because of the strength of the U.S. economy and the country’s perceived longterm viability and stability. All are predicated on the ability of the U.S. to protect itself, safeguard its interests, and render assistance to its allies, and all depend on a competent, effective, and commensurately sized military. the decline of U.S. influence in regional affairs. For decades, the perception of American strength and resolve has helped to deter adventurous bad actors and tyrannical dictators and has underwritten a vast network of U.S. allies and partners. Regrettably, both that perception and, as a consequence, its deterrent and reassuring effects are eroding. Recognition of this problem is growing in the U.S. and was forcefully addressed in the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), which called for a renewal of America’s military power. However, spending on defense must be commensurate with the interests that the defense establishment is called upon to protect, and there continues to be a significant—even growing— gap between the two. Meanwhile, America’s allies, with a few notable exceptions, continue to underinvest in their military forces, and the United States’ chief competitors are hard at work improving their own. The result is an increasingly dangerous world threatening a weaker America. This can seem odd to many observers because U.S. forces have dominated the battlefield in tactical engagements with enemy forces over the past 30 years. Not surprisingly, the forces built to battle those of the Soviet Union have handily defeated the forces of Third World dictators and terrorist organizations. These military successes, however, are quite different from lasting political successes and have masked the deteriorating condition of America’s military, which has been able to undertake such operations only by “cashing in” on investments made in the 1980s and 1990s. Unseen by the American public, the consumption of our military readiness has not been matched by corresponding investments in replacements for the equipment, resources, and capacity used up since September 11, 2001, in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. It is therefore critical that we understand the condition of the United States military with respect to America’s vital national security interests, the threats to those interests, and the context within which the U.S. might have to use hard power. It is likewise important to know how these three areas— operating environments, threats, and the posture of the U.S. military—change over time, given that such changes can have substantial implications for defense policies and investments. The U.S. Constitution opens with a beautiful passage in which “We the People” state that among their handful of purposes in establishing the Constitution 2 was to “provide for the common defence.” The Constitution’s enumeration of limited powers for the federal government includes the powers of Congress “To declare War,” “To raise and support Armies,” “To provide and maintain a Navy,” “To provide for calling forth the Militia,” and “To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia” and the power of the President as “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.” With such constitutional priority given to defense of the nation and its vital interests, one might expect the federal government to produce a standardized, consistent reference work on the state of the nation’s security. Yet no such single volume exists, especially in the public domain, to allow comparisons from year to year. In the past half-dozen years, the Department of Defense has moved to restrict reporting of force readiness even further. Thus, the American people and even the government itself are prevented from understanding whether investments in defense are achieving their desired results. What America needs is a publicly accessible reference document that uses a consistent, methodical, and repeatable approach to assessing defense requirements and capabilities. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of U.S. Military Strength, an annual assessment of the state of America’s hard power, fills this void, addressing both the geographical and functional environments that are relevant to the United States’ vital national interests and the threats that rise to a level that puts or has the strong potential to put those interests at risk. Any assessment of the adequacy of military power requires two primary reference points: a clear statement of U.S. vital security interests and an objective requirement for the military’s capacity for operations that serves as a benchmark against which to measure current capacity. Top-level national security documents issued by a long string of presidential Administrations have consistently made clear that three interests are central to any assessment of national military power: l l Defense of the homeland; Successful conclusion of a major war that has the potential to destabilize a region of critical interest to the U.S.; and 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Preservation of freedom of movement within the global commons: the sea, air, outer space, and cyberspace domains through which the nations of the world conduct their business. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 3 advances in their own militaries or that the new capability might not be as effective as we believed during its development. The current war in Ukraine offers compelling evidence of this. Although new technologies—unmanned aerial vehicles, anti-arEvery President has recognized that protecting mor guided munitions, cyberwarfare—are on display America from attack is one of the U.S. military’s in abundance, “old school” weaponry like artillery, fundamental reasons for being. Going to war has rockets, and automatic weapons have proven to be always been controversial, but the decision to do so devastatingly effective. has been based consistently on the conclusion that The historical record of war shows repeatedly that one or more vital U.S. interests were at stake. new technologies convey temporary advantages: The This Index embraces the requirement that the force that wins is usually the one that is best able to U.S. military should be able to handle two major sustain operations over time, replace combat losses wars or two major regional contingencies (MRCs) with fresh forces and equipment, and use its capabilisuccessfully at the same time or in closely overlap- ties in novel ways that account for the enemy, terrain, ping time frames as the most compelling rationale time, and achievable objectives. This reality has led for sizing U.S. military forces. The basic argument the authors to return consistently to an appreciation is this: The nation should have the ability to engage of the force’s capacity, the modernity of its capabiliand defeat one opponent and still have the ability ties, and its readiness for close combat with an equalto guard against competitor opportunism: that is, ly capable and competent enemy. Consequently, this to prevent someone from exploiting the perceived Index continues to emphasize the importance of the opportunity to move against U.S. interests while two-war force sizing benchmark and the need to enAmerica is engaged elsewhere. sure that the current force is ready for war and mateThe Index is descriptive, not prescriptive: It re- rially capable of winning in hard combat. views the current condition of its subjects within the assessed year and describes how conditions Assessing the World and have changed during the previous year, informed by the Need for Hard Power the baseline condition established by the inaugural The assessment portion of the Index is composed 2015 Index. In short, the Index answers the question, of three major sections that address the aforemen“Have conditions improved or worsened during the tioned areas of primary interest: the operating enassessed year?” vironments within or through which America’s milThis study also assesses the U.S. military against itary must be employed, threats to U.S. vital national the two-war benchmark and various metrics that are interests, and the U.S. military services themselves. explained further in the military capabilities section. For each of these areas, the Index provides context, Importantly, the Index measures the hard power explaining why a given topic is addressed and how needed to win conventional wars rather than the it relates to understanding the nature of America’s general utility of the military relative to the breadth hard-power requirements. of tasks it might be (and usually is) assigned in order The authors of this study used a five-category to advance U.S. interests short of war. scoring system that ranges from “very poor” to “exThe authors acknowledge that advances in tech- cellent” or “very weak” to “very strong” as appronology can translate into new military capabilities. priate to each topic. This approach was selected as New tools, platforms, and weapons tend to prompt the best way to capture meaningful gradations while some observers to assume that older capabilities can avoiding the appearance that a high level of precibe replaced easily with new ones, often in reduced sion was possible given the nature of the issues and numbers, or that the current force will be trans- the information that was publicly available. formed in ways that make it decisively better than Some factors are quantitative and lend themthat of an opponent. Typically missing in the most selves to discrete measurement; others are very optimistic assessments of what the military might qualitative in nature and can be assessed only then be able to do is a corresponding recognition through an informed understanding of the material that competitors quickly adopt similar technological that leads to an informed judgment. l By themselves, purely quantitative measures tell only part of the story when it comes to the relevance, utility, and effectiveness of hard power. Using only quantitative metrics to assess military power or the nature of an operating environment can lead to misinformed conclusions. For example, the mere existence of a large fleet of very modern tanks has little to do with the effectiveness of the armored force in actual battle if the employment concept is irrelevant to modern armored warfare. (Imagine, for example, a battle in rugged mountains.) Also, experience and demonstrated proficiency are often so decisive in war that numerically smaller or qualitatively inferior but well-trained and experienced forces can defeat a larger or qualitatively superior adversary that is inept or poorly led. Again, the differing performance of Russian and Ukrainian troops is illuminating, and countries like China are taking note. The world is still very much a qualitative place, however digital and quantitative it has become thanks to the explosion of advanced technologies, and judgments have to be made in the absence of certainty. We strive to be as objective and evenhanded as possible in our approach and as transparent as possible in our methodology and sources of information so that readers can understand why we reached the conclusions we reached—and perhaps reach their own as well. The result will be a more informed debate about what the United States needs in terms of military capabilities to deal with the world as it is. A detailed discussion of scoring is provided in each assessment section. In our assessment, we begin with the operating environment because it provides the geostrategic stage upon which the U.S. attends to its interests: l l l 4 The various states that would play significant roles in any regional contingency; The terrain that enables or restricts military operations; the infrastructure—ports, airfields, roads, and rail networks (or lack thereof )—on which U.S. forces would depend; and The types of its linkages and relationships with a region and major actors within it that cause the U.S. to have interests in the area or that facilitate effective operations. Major actors within each region are identified, described, and assessed in terms of alliances, political stability, the presence of U.S. military forces and relationships, and the maturity of critical infrastructure. Our assessment focuses on three key regions— Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—because of their importance relative to U.S. vital security, economic, and diplomatic interests. This does not mean that we view Latin America and Africa as unimportant. It means only that the security challenges within these regions do not currently rise to the level of direct threats to America’s vital interests as we have defined them. We addressed their condition in the 2015 Index and will provide updated assessments when circumstances make such reassessments necessary. Next is a discussion of threats to U.S. vital interests. Here we identify the countries and non-state actors that pose the greatest current or potential threats to U.S. vital interests based on two overarching factors: behavior and capability. We accept the classic definition of “threat” as a combination of intent and capability, but while capability has attributes that can be quantified, intent is difficult to measure. We concluded that “observed behavior” serves as a reasonable surrogate for intent because it is the clearest manifestation of intent. We based our selection of threat countries and non-state actors on their historical behavior and explicit policies or formal statements vis-à-vis U.S. interests, scoring them in two areas: the degree of provocative behavior that they exhibited during the year and their ability to pose a credible threat to U.S. interests regardless of intent. For example, a state full of bluster but with only a moderate ability to act accordingly poses a lesser threat, and a state that has great capabilities and a record of bellicose behavior that is opposed to U.S. interests still warrants attention even if it is relatively quiet in a given year. The combination of behavior and ability to pose a credible threat eliminates most smaller terrorist, insurgent, and criminal groups and many problematic states because they do not have the ability to challenge America’s vital national interests successfully. Finally, we address the status of U.S. military power in three areas: capability (or modernity), capacity, and readiness. To do this, we must answer four questions: 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength l l l l Do U.S. forces possess operational capabilities that are relevant to modern warfare? l Can they defeat the military forces of an opposing country? Do they have a sufficient amount of such capabilities? Is the force sufficiently trained to win in combat, and is its equipment materially ready? Topical Essays Each edition of the Index provides the opportunity to share with readers authoritative insights into issues that affect U.S. military power. Past editions have included essays on logistics, alliances, experimentation, the spectrum of conflict and the domains in which forces operate, and special operations forces, among many others. There is a lot of shaft that makes the pointy end of a spear effective, and we endeavor to explain what this means with these essays. In this edition, we are pleased to share the work of authors who address recruiting, the complexity of military program costs, and a recently announced agreement between the U.S., the United Kingdom, and Australia involving naval power. l In fiscal year 2022, the military services are struggling to recruit a sufficient number of young Americans to fill the ranks. There are many reasons why this is the case, and there are substantial consequences for America’s military power should the services continue to fall short in their efforts. In his essay, “New Approaches for a New Era in Recruiting the All Volunteer Force,” Richard Brady draws on his extensive experience in the field to explain the various factors, systems, and processes involved and to offer recommendations that, if implemented, could help to improve such efforts. All of these are fundamental to success even if they are not de facto determinants of success (something we explain further in the section). We also address the condition of the U.S. nuclear weapons capability, assessing it in areas that are unique to this military component and critical to understanding its real-world viability and effectiveness as a strategic deterrent, and provide a descriptive overview of current U.S. ballistic missile defense capabilities and challenges. The Index does not assess (“score”) U.S. cyber and ballistic missile defense capabilities. There are as yet no viable metrics by which to measure the capacity, capability, or readiness of these elements of national defense, their constituent service components, and elements of the government that contribute to activities in these domains, and it is not yet clear how one would assess their roles in measuring “hard combat power,” which is the focus of this publication. However, we do provide overviews of each functional capability, explaining to the reader the capability as it is currently constituted and aspects of its function and contribution. Contributing from “down under,” Peter Jennings writes from Australia to explain why the recently signed agreement involving Australia, the U.K., and the U.S. (AUKUS) is so important to their mutual security interests. The U.S. and U.K. have agreed to help Australia develop a nuclear-powered submarine capability. In “AUKUS: New Opportunities for the United States and Its Closest Allies,” Jennings provides context essential to understanding why this is a big deal. l John Ferrari concludes with “Determining the Real Cost of the Tools of War,” a superb explanation of why the defense budget is so hard to understand. On the surface, a request for funding to purchase an airplane might appear simple. However, as one gets into the wicked details, the multitude of confusing terms, tricky definitions, and different ways to treat “cost” can easily mislead any but the most expert analyst to an incorrect understanding of what the defense budget actually buys. Scoring U.S. Military Strength Relative to Vital National Interests The purpose of this Index is to make the national debate about defense capabilities better informed by assessing the U.S. military’s ability to defend against current threats to U.S. vital national interests within the context of the world as it is. Each of the elements considered—the stability of regions and access to them by America’s military forces; the various threats as they improve or lose capabilities and change their behavior; and the United States’ armed forces themselves as they adjust to evolving The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 5 fiscal realities and attempt to balance readiness, capacity (size and quantity), and capability (how modern they are) in ways that enable them to carry out their assigned missions successfully—can change from year to year. Each region of the world has its own set of characteristics that include terrain; man-made infrastructure (roads, rail lines, ports, airfields, power grids, etc.); and states with which the United States has relationships. In each case, these factors combine to create an environment that is either favorable or problematic when it comes to the ability of U.S. forces to operate against threats in the region. Various states and non-state actors within these regions possess the ability to threaten—and have consistently behaved in ways that do threaten— America’s interests. Fortunately for the U.S., these major threat actors are few in number and continue to be confined to three regions—Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—thus enabling the U.S. (if it will do so) to focus its resources and efforts accordingly. Unfortunately, however, when one of these major threat actors does something outrageous like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the damage is not confined to the immediate region. Our globally interconnected world means that local wars have global consequences that lead to severe economic, diplomatic, and security problems for the U.S., its allies, and its trading partners. Russia’s assault on Ukraine has sent shocks throughout energy and food markets, causing severe shortages and spikes in costs for nearly every country. One can only imagine the catastrophe that would result if China decided to seize Taiwan or use force to take control of disputed islands or if Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear weapons capability prompted Israel to use force to protect itself. The question that looms large in any of these scenarios is both simple and fundamental: Is the U.S. military up to the task of defending America’s interests? To that point, America’s military services are beset by aging equipment, shrinking numbers, rising costs, and problematic funding. These four elements interact in ways that are difficult to measure in concrete terms and impossible to forecast with any certainty. Nevertheless, the exercise of describing them and characterizing their general condition is worthwhile because it informs debates about defense policies and the allocation of resources that are necessary if the U.S. military is to carry out its assigned 6 duties. Further, as seen in this 2023 Index, noting how conditions have changed during the preceding year helps to shed light on the effects that policies, decisions, and actions have on security affairs that involve the interests of the United States, its allies and friends, and its enemies. It should be borne in mind that each annual Index assesses conditions as they are for the assessed year. This 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength describes changes that occurred during the preceding year with updates current as of early September 2022. Assessments for global operating environment, threats to vital U.S. interests, and U.S. military power are shown in the Executive Summary. Factors that would push things toward “bad” (the left side of the scale) tend to move more quickly than those that improve one’s situation, especially when it comes to the material condition of the U.S. military. Munitions can be expended in seconds, and an airplane or a tank can be lost in an instant. Replacing either takes months or years. Similarly, wars unfold at a breakneck pace and can last weeks, months, or years, but their aftermath can extend decades into the future, changing the geopolitical and global economic landscapes in ways that cannot be undone. Of the three areas measured—global operating environment, threats to vital U.S. interests, and U.S. military power—the U.S. can directly control only one: its own military. The condition of the U.S. military can influence the other two because a weakened America arguably emboldens challenges to its interests and loses potential allies, but a militarily strong America deters opportunism and draws partners to its side from across the globe. Conclusion During the decades since the end of the Second World War, the United States has underwritten and taken the lead in maintaining a global order that has benefited more people in more ways than at any other period in history. Now, however, that American-led order is arguably under the greatest stress since its founding, and some wonder whether it will break apart entirely as fiscal and economic burdens (exacerbated by the costs incurred in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and the disruptions caused by the Russia–Ukraine War) plague nations, violent extremist ideologies threaten the stability of entire regions, state and non-state opportunists seek to exploit upheavals, and major states 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength compete to establish dominant positions in their respective regions. America’s leadership role remains in question, and its security interests are under substantial pressure. Challenges continue to grow, long-standing allies are not what they once were, and the U.S. is increasingly bedeviled by debt and domestic discord that constrain its ability to sustain its forces at a level that is commensurate with its interests. Informed deliberations on the status of America’s military power are therefore desperately needed. It is our hope, as always, that the Index of U.S. Military Strength will help to facilitate those deliberations. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 7 Executive Summary “As currently postured, the U.S. military is at growing risk of not being able to meet the demands of defending America’s vital national interests. It is rated as weak relative to the force needed to defend national interests on a global stage against actual challenges in the world as it is rather than as we wish it were. This is the logical consequence of years of sustained use, underfunding, poorly defined priorities, wildly shifting security policies, exceedingly poor discipline in program execution, and a profound lack of seriousness across the national security establishment even as threats to U.S. interests have surged.” T The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 9 officials and to the American public, to gauge the U.S. military’s ability to perform its missions in today’s world. The inaugural 2015 edition established a baseline assessment on which each annual edition builds, one that both assesses the state of affairs for its respective year and measures how key factors have changed during the preceding year. The Index is not an assessment of what might be, although the trends that it captures may well imply both concerns and opportunities that can guide decisions that are germane to America’s security. Rather, the Index should be seen as a report card for how well or poorly conditions, countries, and the U.S. military have evolved during the assessed year. The he United States maintains a military force to past cannot be changed, but it can inform, just as the protect the homeland from attack and to pro- future cannot be predicted but can be shaped. tect its interests abroad. There are other uses, of course—for example, to assist civil authorities in What the Index Assesses times of emergency or to deter enemies—but this The Index of U.S. Military Strength assesses the force’s primary purpose historically has been to ease or difficulty of operating in key regions based make it possible for the U.S. to physically impose its on existing alliances, regional political stability, the will on an enemy when necessary. presence of U.S. military forces, and the condition It is therefore critical that the American people of key infrastructure. Threats are assessed based on understand the condition of the United States mili- the behavior and physical capabilities of actors that tary with respect to America’s vital national security pose challenges to vital U.S. national interests. The interests, threats to those interests, and the context condition of America’s military power is measured within which the U.S. might have to use “hard pow- in terms of its capability or modernity, capacity for er” to protect those interests. Because changes can operations, and readiness to handle assigned mishave substantial implications for defense policies sions. This framework provides a single-source refand investment, knowing how these three areas erence for policymakers and other Americans who change over time is likewise important. Of the three, seek to know whether our military is up to the task the condition of the military is the most important of defending our national interests. to understand because it is the only one over which Any discussion of the aggregate capacity and the U.S. has complete control, and it underwrites breadth of the military power needed to protect U.S. the ability of all other aspects of national power to security interests requires a clear understanding of flourish or fail. precisely what interests must be defended. Three viEach year, The Heritage Foundation’s Index of tal interests have been specified consistently (albeit U.S. Military Strength employs a standardized, con- in varying language) by a string of Administrations sistent set of criteria, accessible both to government over the past few decades: l l l Defense of the homeland; Successful conclusion of a major war that has the potential to destabilize a region of critical interest to the U.S.; and Preservation of freedom of movement within the global commons (the sea, air, outer space, and cyberspace domains) through which the world conducts its business. To defend these interests effectively on a global scale, the United States needs a military force of sufficient size: what is known in the Pentagon as capacity. The many factors involved make determining how big the military should be a complex exercise, but successive Administrations, Congresses, Department of Defense staffs, and independent commissions have managed to arrive at a surprisingly consistent force-sizing rationale: an ability to handle two major conflicts simultaneously or in closely overlapping time frames. At its root, the current National Defense Strategy (NDS) implies the same force requirement.1 Its emphasis on a return to long-term competition with major powers, explicitly naming Russia and China as primary competitors,2 reemphasizes the need for the United States to have: l l l Sufficient military capacity to deter or win against large conventional powers in geographically distant regions, The ability to conduct sustained operations against lesser threats, and The ability to work with allies and maintain a U.S. presence in regions of key importance that is sufficient to deter behavior that threatens U.S. interests. No matter how much America desires that the world be a simpler, less threatening place that is more inclined to beneficial economic interactions than violence-laden friction, the patterns of history show that competing powers consistently emerge and that the U.S. must be able to defend its interests in more than one region at a time. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s dramatic expansion of its military and its provocative behavior far beyond the 10 Indo-Pacific region, North Korea’s intransigence with respect to even discussing its nuclear capabilities, and Iran’s dogged pursuit of a nuclear weapon capability and sustained support for terrorist groups illustrate this point. Consequently, this Index embraces the two-war or two-contingency requirement. Since its founding, the U.S. has been involved in a major “hot” war every 15–20 years. Since World War II, the U.S. has also maintained substantial combat forces in Europe and other regions while simultaneously fighting major wars as circumstances demanded. The size of the total force roughly approximated the two-contingency model, which has the inherent ability to meet multiple security obligations to which the U.S. has committed itself while also modernizing, training, educating, and maintaining the force. Accordingly, our assessment of the adequacy of today’s U.S. military is based on the ability of America’s armed forces to engage and defeat two major competitors at roughly the same time. We acknowledge that without a dramatic change in circumstances such as the onset of a major conflict, a multitude of competing interests that evolve during extended periods of peace and prosperity will cause Administrations and Congresses to favor spending on domestic programs rather than investing in defense. Extended peace leads to complacency, which can lead to distraction and less willingness to invest in defense. The result: a weakened military, competitors that are emboldened, and a nation at risk. Consequently, winning the support needed to increase defense spending to the level that a force with a two-war capacity requires is admittedly difficult politically. But this does not change the patterns of history, the behavior of competitors, or the reality of what it takes to defend America’s interests in an actual war. This Index’s benchmark for a two-war force is derived from a review of the forces used for each major war that the U.S. has undertaken since World War II and the major defense studies completed by the federal government over the past 30 years. We concluded that a standing (Active Component) twowar–capable force would consist of: l l l Army: 50 brigade combat teams (BCTs); Navy: 400 battle force ships and 624 strike aircraft; Air Force: 1,200 fighter/ground-attack aircraft; 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength l Marine Corps: 30 battalions; and l Space Force: metric not yet established. This recommended force does not account for homeland defense missions that would accompany a period of major conflict and are generally handled by Reserve and National Guard forces. Nor does it constitute the totality of the Joint Force, which includes the array of supporting and combat-enabling functions that are essential to the conduct of any military operation: logistics; transportation (land, sea, and air); health services; communications and data handling; and force generation (recruiting, training, and education) to name only a few. Rather, these are combat forces that are the most recognizable elements of America’s hard power but that also can be viewed as surrogate measures for the size and capability of the larger Joint Force. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 11 The Global Operating Environment The United States is a global power with global security interests, and its military must be able to protect those interests anywhere they are threatened. While this may occur in any region, three regions—Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—stand apart because of the scale and scope of U.S. interests associated with them and the significance of competitors that are able to pose commensurately large threats. Aggregating the three regional scores provides a global operating environment score of FAVORABLE in the 2023 Index. Europe. Overall, the European region remains stable, mature, and friendly to U.S. military operational requirements. Russia remains the preeminent military threat to the region, both conventionally and unconventionally, and its invasion of Ukraine marks a serious escalation in its efforts to exert influence on its periphery. China continues to have a significant presence in Europe and, by mitigating sanctions, has been a key enabler of the Russian government’s ability to conduct the war in Ukraine. The past year saw continued U.S. reengagement with the continent along with increases in European allies’ defense budgets and capability investment spurred by alarm over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and related threats to countries that are supporting Ukraine’s defense. It is difficult to predict whether NATO’s renewed emphasis on collective defense and its reinvigorated defense spending will continue in the long term or whether this is a short-term response to Russia’s invasion. We hope for the former but must plan against the latter. For Europe, scores this year remained steady, as they did in 2021 (assessed in the 2022 Index), with no substantial changes in any individual categories or average scores. The 2023 Index again assesses the European operating environment as “favorable.” The Middle East. The Middle East region is now highly unstable, both because its authoritarian regimes have eroded and because it continues to serve as a breeding ground for terrorism. Overall, regional security has continued to deteriorate. Although Iraq has restored its territorial integrity since the defeat of ISIS, the political situation and future relations between Baghdad and the United States will remain difficult as long as a government that is sympathetic to Iran is in power. U.S. relations in the region will remain complex, but this has not stopped the U.S. military from operating as needed. The region’s primary challenges—continued meddling by Iran and surging transnational terrorism—are made more difficult by Sunni–Shia sectarian divides, the more aggressive nature of Iran’s Islamist revolutionary nationalism and its open pursuit of nuclear weapon capabilities, and the proliferation of Sunni Islamist revolutionary groups. In the Middle East, the U.S. benefits from operationally proven procedures that leverage bases, infrastructure, and the logistical processes needed to maintain a large force forward deployed thousands of miles away from the homeland. The personal links between allied armed forces are also present, and joint training exercises improve interoperability and give the U.S. an opportunity to influence some of the region’s future leaders. America’s relationships in the region are pragmatic, based on shared security and economic concerns. As long as these issues remain relevant to both sides, the U.S. is likely to have an open door to operate in the Middle East when its national interests require that it do so. Although circumstances in all measured areas vary throughout the year, in general terms, the 2023 Index assesses the Middle East operating environment as “moderate,” but the region’s political stability continues to be “unfavorable” and will remain a dark cloud over everything else. Global Operating Environment: Summary VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE FAVORABLE EXCELLENT Operating Environment: Europe VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE FAVORABLE Alliances EXCELLENT % Political Stability % U.S. Military Posture % Infrastructure % OVERALL % Operating Environment: Middle East VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE Alliances FAVORABLE EXCELLENT FAVORABLE EXCELLENT % Political Stability MODERATE % U.S. Military Posture % Infrastructure % OVERALL % Operating Environment: Asia VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE Alliances % Political Stability % U.S. Military Posture % Infrastructure % OVERALL % Global Operating Environment VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE Europe Middle East 12 FAVORABLE % % Asia % OVERALL % 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength EXCELLENT l l l Interests that conflict with those of the United States; Sometimes hostile intentions toward the U.S.; and In some cases, growing military capabilities that are leveraged to impose an adversary’s will by coercion or intimidation of neighboring countries, thereby creating regional instabilities. The government of the United States constantly faces the challenge of employing the right mix of diplomatic, economic, public information, intelligence, and military capabilities to protect and advance its interests. Because this Index focuses on the military component of national power, its assessment of threats is correspondingly an assessment of the military or physical threat posed by each entity addressed in this section. Russia remains the primary threat to American interests in Europe as well as the most pressing threat to the United States. Its invasion of Ukraine reintroduced conventional war to Europe. It also is the largest conflict on that continent since the end of the Second World War, and its many economic and security repercussions are felt across the globe. Moscow also remains committed to massive pro-Russia propaganda campaigns in other Eastern European countries as well as disruptive activities around its periphery and across the Middle East. The 2023 Index again assesses the threat emanating from Russia as “aggressive” in its behavior and “formidable” (the highest category on the scale) in its growing capabilities. Though Russia is consuming its inventory of munitions, supplies, equipment, and even military personnel in its war against Ukraine, it is also replacing those items and people. Unlike Ukraine’s, Russia’s industrial capacity remains untouched by the war, and will allow Moscow to replace older equipment lost in the conflict with newly manufactured items. Russia’s military is also gaining valuable combat experience. Consequently, the war may actually serve to increase the challenge that Russia poses to U.S. Threats to U.S. Interests interests on the continent. America faces challenges to its security at home China, the most comprehensive threat the and interests abroad from countries and organiza- U.S. faces, remained “aggressive” in the scope of tions that have: its provocative behavior and earns the score of The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 13 Asia. The Asian strategic environment includes half of the globe and is characterized by a variety of political relationships among states with wildly varying capabilities. This makes Asia far different from Europe, which in turn makes America’s relations with the region different from its relations with Europe. American conceptions of Asia must recognize the physical limitations imposed by the tyranny of distance and the need to move forces as necessary to respond to challenges from China and North Korea. The complicated nature of intra-Asian relations and the lack of an integrated, regional security architecture along the lines of NATO make defense of U.S. security interests more challenging than many Americans appreciate. However, the U.S. has strong relations with allies in the region, and their willingness to host bases helps to offset the vast distances that must be covered. The militaries of Japan and the Republic of Korea are larger and more capable than European militaries, and both countries are becoming more interested in developing missile defense capabilities that will be essential in combatting the regional threat posed by North Korea. In Japan, the growing public awareness of the need to adopt a more “normal” posture militarily in response to China’s increasingly aggressive actions indicates a break with the pacifist tradition among the Japanese since the end of World War II. This could lead to improved military capabilities and the prospect of joining the U.S. in defense measures beyond the immediate vicinity of Japan. We continue to assess the Asia region as “favorable” to U.S. interests in terms of alliances, overall political stability, militarily relevant infrastructure, and the presence of U.S. military forces. Summarizing the condition of each region enables us to get a sense of how they compare in terms of the difficulty that would be involved in projecting U.S. military power and sustaining combat operations in each one. As a whole, the global operating environment maintains a score of “favorable,” which means that the United States should be able to project military power anywhere in the world to defend its interests without substantial opposition or high levels of risk other than those imposed by a capable enemy. Threats to U.S. Vital Interests: Summary SEVERE HIGH ELEVATED GUARDED LOW Behavior of Threats HOSTILE AGGRESSIVE China % Russia % Iran % North Korea TESTING ASSERTIVE BENIGN ASPIRATIONAL MARGINAL GUARDED LOW % Non-State Actors % OVERALL % Capability of Threats FORMIDABLE China % Russia % GATHERING Iran % North Korea % Non-State Actors CAPABLE % OVERALL % Threats to U.S. Vital Interests SEVERE HIGH China % Russia % Iran % North Korea % Non-State Actors % OVERALL % “formidable” for its capability because of its continued investment in the modernization and expansion of its military and the particular attention it has paid to its space, cyber, and artificial intelligence capabilities. The People’s Liberation Army continues 14 ELEVATED to extend its reach and military activity beyond its immediate region and engages in larger and more comprehensive exercises, including live-fire exercises in the East China Sea near Taiwan and aggressive naval and air patrols in the South China Sea. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength and international financial institutions. This Index therefore assesses the overall threat from North Korea, considering the range of contingencies, as “testing” for level of provocation of behavior and “gathering” for level of capability. A broad array of terrorist groups remain the most hostile of any of the threats to America examined in the Index. The primary terrorist groups of concern to the U.S. homeland and to Americans abroad are the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and al-Qaeda. Al-Qaeda and its branches remain active and effective in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and the Sahel of Northern Africa. Though no longer a territory-holding entity, ISIS also remains a serious presence in the Middle East, in South and Southeast Asia, and throughout Africa, threatening stability as it seeks to overthrow governments and impose an extreme form of Islamic law. Its ideology continues to inspire attacks against Americans and U.S. interests. Fortunately, Middle East terrorist groups remain the least capable threats facing the U.S., but they cannot be dismissed. Just as there are American interests that are not covered by this Index, there may be additional threats to American interests that are not identified here. This Index focuses on the more apparent sources of risk and those that appear to pose the greatest threat. Compiling the assessments of these threat sources, the 2023 Index again rates the overall global threat environment as “aggressive” and “gathering” in the areas of threat actor behavior and material ability to harm U.S. security interests, respectively, leading to an aggregated threat score of “high.” The Status of U.S. Military Power Finally, we assessed the military power of the United States in three areas: capability, capacity, and readiness. We approached this assessment service by service as the clearest way to link military force size; modernization programs; unit readiness; and (in general terms) the functional combat power (land, sea, air, and space) that each service represents. We treated the United States’ nuclear capability as a separate entity because of its truly unique characteristics and constituent elements, from the weapons themselves to the supporting infrastructure that is fundamentally different from the infrastructure that supports conventional capabilities. While not fully assessing cyber as we do the Army, Navy, Air The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 15 China also continues to conduct probes of the South Korean and Japanese air defense identification zones, drawing rebukes from both Seoul and Tokyo, and its statements about Taiwan and exercise of military capabilities in the air and sea around the island have been increasingly belligerent. China is taking note of the war in Ukraine and U.S. military developments and has been adjusting its own posture, training, and investments accordingly. Iran represents by far the most significant security challenge to the United States, its allies, and its interests in the greater Middle East. Its open hostility to the United States and Israel, sponsorship of terrorist groups like Hezbollah, and history of threatening the commons underscore the problem it could pose. Today, Iran’s provocations are of primary concern to the region and America’s allies, friends, and assets there. Iran relies heavily on irregular (to include political) warfare against others in the region and fields more ballistic missiles than any of its neighbors. Iran’s development of ballistic missiles and its potential nuclear capability also make it a long-term threat to the security of the U.S. homeland. In addition, Iran has continued its aggressive efforts to shape the domestic political landscape in Iraq, adding to the region’s general instability. The 2023 Index extends the 2022 Index’s assessment of Iran’s behavior as “aggressive” and its capability as “gathering.” North Korea’s military poses a security challenge for American allies South Korea and Japan, as well as for U.S. bases in those countries and on the island territory of Guam. North Korean officials are belligerent toward the United States, often issuing military and diplomatic threats. Pyongyang also has engaged in a range of provocative behavior that includes nuclear and missile tests and tactical-level attacks on South Korea. It has used its missile and nuclear tests to enhance its prestige and importance domestically, regionally, and globally and to extract various concessions from the U.S. in negotiations on its nuclear program and various aid packages. Such developments also improve North Korea’s military posture. U.S. and allied intelligence agencies assess that Pyongyang has already achieved nuclear warhead miniaturization, the ability to place nuclear weapons on its medium-range missiles, and the ability to reach the continental United States with a missile. North Korea also uses cyber warfare as a means of guerilla warfare against its adversaries Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force, we acknowledge the importance of new tools and organizations that have become essential to deterring hostile behavior and winning wars. These three areas of assessment (capability, capacity, and readiness) are central to the overarching questions of whether the U.S. has a sufficient quantity of appropriately modern military power and whether military units are able to conduct military operations on demand and effectively. As reported in all previous editions of the Index, the common theme across the services and the U.S. nuclear enterprise is one of force degradation caused by many years of underinvestment, poor execution of modernization programs, and the negative effects of budget sequestration (cuts in funding) on readiness and capacity in spite of repeated efforts by Congress to provide relief from low budget ceilings imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011. The services have undertaken efforts to reorient from irregular warfare to large-scale combat against a peer adversary, but such shifts take time and even more resources. Because of the rising costs of fuel, munitions, and repair parts and the lack of qualified maintainers and maintenance facilities, much of the progress in regaining readiness that had been made in 2020 and 2021 has been lost in 2022. The forecast for 2023 is likewise gloomy given a proposed defense budget for FY 2023 that will not be sufficient to keep pace with ongoing and dramatic increases in inflation. Experience in warfare is ephemeral and context-sensitive. Valuable combat experience is lost as servicemembers who individually gained experience leave the force, and it retains direct relevance only for future operations of a similar type: Counterinsurgency and adviser support operations in Iraq, for example, gained over the past two decades are fundamentally different from major conventional operations against a state like Iran or China. Although portions of the current Joint Force are experienced in some types of operations, the force as a whole lacks experience with high-end, major combat operations of the sort being seen in Ukraine and toward which the U.S. military services have only recently begun to redirect their training and planning. Additionally, the force is still aged and shrinking in its capacity for operations even if limited quantities of new equipment like the F-35 Lightning II fighter are being introduced. 16 We characterized the services and the nuclear enterprise on a five-category scale ranging from “very weak” to “very strong,” benchmarked against criteria elaborated in the full report. These characterizations should not be construed as reflecting either the competence of individual servicemembers or the professionalism of the services or Joint Force as a whole; nor do they speak to the U.S. military’s strength relative to the strength of other militaries around the world in direct comparison. Rather, they are assessments of the institutional, programmatic, and material health or viability of America’s hard military power benchmarked against historical instances of use in large-scale, conventional operations and current assessments of force levels likely needed to defend U.S. interests against major enemies in contemporary or near-future combat operations. Our analysis concluded with these assessments: l l Army as “Marginal.” The Army’s score remains “marginal” in the 2023 Index, and significant challenges that have arisen during the year call into question whether it will improve its status in the year ahead. Though the Army has sustained its commitment to modernizing its forces for great-power competition, its modernization programs are still in their development phase, and it will be a few years before they are ready for acquisition and fielding. In other words, the Army is aging faster than it is modernizing. It remains “weak” in capacity with only 62 percent of the force it should have. However, 25 of its 31 Regular Army BCTs are at the highest state of readiness, thus earning a readiness score of “very strong” and conveying the sense that the service knows what it needs to do to prepare for the next major conflict. Nevertheless, the Army’s internal assessment must be balanced against its own statements that unit training is focused on company-level operations rather than battalion or brigade operations. Consequently, how these “ready” brigade combat teams would actually perform in combat is an open question. Navy as “Weak.” This worrisome score, a drop from “marginal” assessed in the 2022 Index, is driven by problems in capacity (“very weak”) and readiness (“weak”). This Index 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength assesses that the Navy needs a battle force of 400 manned ships to do what is expected of it today. The Navy’s current battle force fleet of 298 ships and intensified operational tempo combine to reveal a service that is much too small relative to its tasks. Contributing to a lower assessment is the Navy’s persistent inability to arrest and reverse the continued diminution of its fleet as adversary forces grow in number and capability. If its current trajectory is maintained, the Navy will shrink further to 280 ships by 2037. Current and forecasted levels of funding will prevent the Navy from altering its decline unless Congress undertakes extraordinary efforts to increase assured funding for several years. l l Marine Corps as “Strong.” The score for the Marine Corps was raised to “strong” from “marginal” in the 2022 Index and remains “strong” in this edition for two reasons: (1) because the 2021 Index changed the threshold for capacity, lowering it from 36 infantry battalions to 30 battalions in acknowledgment of the Corps’ argument that it is a one-war force that also stands ready for a broad range of smaller crisis-response tasks, and (2) because of the Corps’ extraordinary, sustained efforts to modernize (which improves capability) and enhance its readiness during the assessed year. Of the five services, the Corps is the only one that has a compelling story for change, has a credible and practical plan for change, and is effectively implementing its plan to change. However, in the absence of additional funding that would enable the Corps to maintain higher end strength while also pursuing its modernization and reorientation efforts, the Corps will reduce the number of its battalions even further to just 21, and this reduction will limit the extent to which it can conduct distributed operations as envisioned and replace combat losses (thus limiting its ability to sustain operations). Though the service remains hampered by old equipment in some areas, it has nearly completed modernization of its entire aviation component, is making good progress in fielding a new amphibious combat vehicle, and is fast-tracking the acquisition of new anti-ship and anti-air weapons. Full realization of its redesign plan will require the acquisition of a new class of amphibious ships, for which the Corps needs support from the Navy. Space Force as “Weak.” The mission sets, space assets, and personnel that have transitioned to the Space Force from the other services since its establishment in December 2019 and that have been added over the past two years have enabled the service to sustain its support to the Joint Force. However, there is little evidence that the USSF has improved its readiness to provide nearly real-time support to operational and tactical levels of force operations or that it is ready in any way to execute defensive and offensive counterspace operations to the degree envisioned by Congress when it The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 17 Air Force as “Very Weak.” The Air Force has been downgraded once again, the second, time in the past two years. The Air Force was assessed as “marginal” in the 2021 Index but, with public reporting of the mission readiness and physical location of combat aircraft implying that it would have a difficult time responding rapidly to a crisis, fell to a score of “weak” in the 2022 Index. During FY 2022, the year assessed for this Index, problems with pilot production and retention, an extraordinarily small amount of time in the cockpit for pilots, and a fleet of aircraft that continues to age compounded challenges even more, leading to the current score of “very weak,” the lowest on our scale. The USAF currently is at 86 percent of the capacity required to meet a two-MRC benchmark, it is short 650 pilots, the average age of its fighter aircraft fleet is 32 years old, and pilots are flying barely more than once per week across all types of aircraft. New aircraft like the F-35 and KC-46 are being introduced, but the pace is too slow. Although there is a chance the Air Force might win a single MRC in any theater, there is little doubt that it would struggle in war with a peer competitor. Both the time required to win such a conflict and the attendant rates of attrition would be much higher than they would be if the service had moved aggressively to increase high-end training and acquire the fifth-generation weapon systems required to dominate such a fight. l U.S. Military Power: Army VERY WEAK Capacity WEAK MARGINAL STRONG VERY STRONG % Capability % Readiness % OVERALL % U.S. Military Power: Navy VERY WEAK Capacity WEAK MARGINAL STRONG VERY STRONG STRONG VERY STRONG STRONG VERY STRONG % Capability % Readiness % OVERALL % U.S. Military Power: Air Force VERY WEAK WEAK MARGINAL Capacity % Capability % Readiness % OVERALL % U.S. Military Power: Marine Corps VERY WEAK Capacity WEAK MARGINAL % Capability % Readiness % OVERALL % U.S. Military Power: Space VERY WEAK 18 WEAK Capacity % Capability % Readiness % OVERALL % MARGINAL 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength STRONG VERY STRONG U.S. Military Power: Nuclear VERY WEAK WEAK MARGINAL STRONG Nuclear Stockpile % Delivery Platform Reliability % Warhead Modernization VERY STRONG % Delivery Systems Modernization % Nuclear Weapons Complex % National Labs Talent % Allied Assurance % OVERALL % U.S. Military Power VERY WEAK WEAK Army STRONG VERY STRONG % Navy Air Force MARGINAL % % Marine Corps % Space % Nuclear % OVERALL % authorized the creation of the Space Force. The majority of its platforms have exceeded their life span, and modernization efforts to replace them are slow and incremental. The service’s two counterspace weapons systems (Meadowlands and Bounty Hunter) cover only a fraction of the offensive and defensive capabilities required to win a conflict in space. Other counterspace systems are likely being developed or, like cyber, are already in play without public announcement. Nevertheless, the USSF’s current visible capacity is not sufficient to support, fight, or weather a war with a peer competitor. l Nuclear Capabilities as “Strong” but Trending Toward “Marginal” or Even “Weak.” This conclusion is sustained from the 2022 Index. The scoring for U.S. nuclear weapons must be considered in the context of a threat environment that is significantly more dangerous than it was in previous years. Until recently, U.S. nuclear forces needed to address one nuclear peer rather than two. Given senior leaders’ reassurances with respect to the readiness and reliability of U.S. nuclear forces, as well as the strong bipartisan commitment to modernization of the entire nuclear enterprise, this year’s Index retains its grade of “strong,” but only for now. U.S. nuclear forces face many risks that, without a continued commitment to a strong deterrent, could warrant a decline to an overall score of “marginal” or “weak.” The reliability of current U.S. delivery systems and warheads is at risk as they continue to age and The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 19 the threat continues to advance. Iran, for example, has announced an ability to enrich uranium to 60 percent (90 percent is needed for a weapon), and Russia and China are aggressively expanding the types and quantities of nuclear weapons in their inventories. Nearly all components of the nuclear enterprise are at a tipping point with respect to replacement or modernization and have no margin left for delays in schedule. Future assessments will need to consider plans to adjust America’s nuclear forces to account for the doubling of peer nuclear threats. While capacity was not assessed this year, it is clear that the change in threat warrants a reexamination of U.S. force posture and the adequacy of current modernization plans. Failure to keep modernization programs on track while planning for a three-party nuclear peer dynamic could lead inevitably to a decline in the strength of U.S. nuclear deterrence. Endnotes 1. Though issued during President Donald J. Trump’s Administration, the 2018 NDS has not yet been superseded by a similar document, focused on the military, from the Administration of President Joseph R. Biden. However, the Biden Administration has released interim guidance in which it sets out the broad outlines and priorities of its national security agenda. In particular, President Biden’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance reiterates the same core national security interests and the same set of major competitor countries posing challenges to U.S. interests that the preceding Administration identified and places them in a global context wherein the U.S. military must be ready to handle several problems in geographically separated locations. See President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, The White House, March 2021, pp. 8–9, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf (accessed August 1, 2022). 2. James Mattis, Secretary of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, p. 2. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf (accessed August 1, 2022). 20 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength In the aggregate, the United States’ military posture can only be rated as “weak.” The Air Force is rated “very weak,” the Navy and Space Force are “weak,” and the U.S. Army is “marginal.” The Marine Corps and nuclear forces are “strong,” but the Corps is a one-war force, and its overall strength is therefore not sufficient to compensate for the shortfalls of its larger fellow services. And if the United States should need to employ nuclear weapons, the escalation into nuclear conflict would seem to imply that handling such a crisis would challenge even a fully ready Joint Force at its current size and equipped with modern weapons. Additionally, the war in Ukraine, which threatens to destabilize not just Europe but the economic and political stability of other regions, shows that some actors (in this case Russia) will not necessarily be deterred from conventional action even though the U.S. maintains a strong nuclear capability. Thus, strong conventional forces of necessary size are essential to the ability of the U.S. to respond to emergent crises in areas of special interest. The 2023 Index concludes that the current U.S. military force is at significant risk of not being able to meet the demands of a single major regional conflict while also attending to various presence and engagement activities. The force would probably not be able to do more and is certainly ill-equipped to handle two nearly simultaneous MRCs—a situation that is made more difficult by the generally weak condition of key military allies. In general, the military services continue to prioritize readiness and have seen some improvement over the past few years, but modernization programs, especially in shipbuilding, continue to suffer as resources are committed to preparing for the future, recovering from 20 years of operations, and offsetting the effects of inflation. In the case of the Air Force, some of its limited acquisition funds are being spent on aircraft of questionable utility in high-threat scenarios while R&D receives a larger share of funding than efforts meant to replace quite aged aircraft are receiving. As observed in both the 2021 and 2022 editions of the Index, the services have normalized reductions in the size and number of military units, the forces remain well below the level needed to meet the two-MRC benchmark, and substantial difficulties in recruiting young Americans to join the military services are frustrating even modest proposals just to maintain service end strength. Congress and the Administration took positive steps to stabilize funding in the latter years of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA). This mitigated the worst effects of BCA-restricted funding, but sustained investment in rebuilding the force to ensure that America’s armed services are properly sized, equipped, trained, and ready to meet the missions they are called upon to fulfill will be critical. At present, the Administration’s proposed defense budget for FY 2023 falls far short of what the services need to regain readiness and to replace aged equipment, and Congress’s intention to increase the proposed budget by 5 percent accounts for barely half of the current rate of inflation, which is nearing 10 percent. As currently postured, the U.S. military is at growing risk of not being able to meet the demands of defending America’s vital national interests. It is rated as weak relative to the force needed to defend national interests on a global stage against actual challenges in the world as it is rather than as we wish it were. This is the logical consequence of years of sustained use, underfunding, poorly defined priorities, wildly shifting security policies, exceedingly poor discipline in program execution, and a profound lack of seriousness across the national security establishment even as threats to U.S. interests have surged. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 21 AUKUS: New Opportunities for the United States and Its Closest Allies Peter Jennings O on a free and open Indo-Pacific enduring and flourishing in the decades ahead.”4 While the Australian Navy appeared to be the first beneficiary of AUKUS’s focus on nuclear propulsion, the reality is that even on the most optimistic projections, a nuclear-powered submarine for Australia is at least a decade—and perhaps more realistically 15 to 20 years—in the future. In this essay, I will assess the opportunities and risks associated with AUKUS, asking what each of the three partners may want to get for their political and economic investment. All three countries stand to gain from AUKUS in geopolitical, strategic, and defense terms, but not without some risk to the practical delivery of defense technology outcomes. AUKUS: The Strategic Context AUKUS reflects a shared understanding among the three partner countries that the PRC presents an immediate and sustained challenge to the international security order, not only globally, but most pressingly in the Indo-Pacific region. Each country has been forced to change policy on the PRC over the past decade, moving from attempts to engage Beijing with a view to shaping its behavior to a point now where the three countries openly acknowledge the danger of an assertive China’s growing power. This has not been an easy process. Australia concluded a free trade agreement with China in late 2014 on terms that would hardly be acceptable today, and Tony Abbott, then the center-right Australian Prime Minister, welcomed Xi Jinping to Canberra saying that “a relationship might begin with commerce but it rarely ends there once trust has been established, as I believe it has between Australia The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 23 n September 15, 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, and U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson held a virtual media conference to announce “the creation of an enhanced trilateral security partnership called ‘AUKUS’—Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.” The partnership focuses on the Indo-Pacific and is intended to “foster deeper integration of security and defense-related science, technology, industrial bases, and supply chains.”1 The most striking initial AUKUS project is “a shared ambition to support Australia in acquiring nuclear-powered submarines” and a projected 18-month time frame “to seek an optimal pathway to deliver this capability.” Only once before has the United States given a foreign power access to technology to develop nuclear propulsion: the United Kingdom in the 1950s. AUKUS therefore represents a significant strategic opportunity for Australia. More broadly, the partnership offers to pool defense-related science and technology and each country’s defense industry into a shared endeavor, working on the following high-priority areas: “cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and additional undersea capabilities.”2 Early reactions to AUKUS described the agreement as a big deal. The Economist declared AUKUS to be as profound a strategic shift as “Nixon going to China in 1972 and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.”3 It was a new piece of strategic architecture in the Indo-Pacific and for that reason directly aimed at the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Beijing’s challenge to the rules-based order. Biden underlined this point at the agreement’s launch: [T]the future of each of our nations—and indeed the world—depends and China.”5 In 2015, then-British Prime Minister David Cameron was welcoming a “golden era” with Beijing based on massive PRC investment in critical infrastructure.6 When Xi visited Washington, D.C., in September 2015, he gave assurances to President Barack Obama that China had “no intention to militarize” the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea and would reduce the cyber-enabled theft of American intellectual property.7 For a short while, there was hope in the White House that Xi could be taken at his word. Since those optimistic times, policy toward the PRC has hardened in the AUKUS capitals. The need to respond to Beijing’s militarization of the South China Sea, massive military spending, coercive use of trade and investment, cyber espionage, and attempts to undermine American and allied influence in the Indo-Pacific has forced governments to make more negative assessments about Beijing’s intentions. The arrival of AUKUS reflects a shared realization that more concerted effort is needed to align policy responses to China and fast-track emerging military capabilities to strengthen deterrence. AUKUS should therefore be seen in the context of the arrival of the QUAD (a grouping that includes the U.S., Australia, Japan, and India); the rapidly growing Australia–U.S.–Japan trilateral defense partnership; and an enlarged and revitalized NATO. These are all recent examples of the world’s consequential pluralist countries grouping together in the face of a sustained authoritarian challenge from the PRC and Russia. AUKUS does not supplant existing bilateral treaty agreements and defense cooperation activities between the U.S. and Australia and the U.S. and Britain, but it brings a new trilateral mechanism to the fore, creating the possibility of wider cooperation among the three countries’ defense and intelligence establishments, research and development, and industrial sectors. AUKUS is perhaps also a tacit acknowledgement of the limits to the individual capacities of the three countries. As powerful as the United States is, it needs capable allies to bolster American military strength, add options for logistic support and sustainment, and field interoperable military platforms. For all three countries, AUKUS is a potentially valuable force multiplier with the capacity to strengthen conventional deterrence and complicate Beijing’s strategic planning. 24 How Does AUKUS Fit with U.S. Strategy? Successive American Administrations have sought to give more priority to the Indo-Pacific, and Biden’s February 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy stresses an “intensifying American focus” on the region. Two themes dominate the Biden strategy: l l This is a competition for influence with China, which “seeks to become the world’s most influential power” through “coercion and aggression,” and The United States will counter this through “collective efforts over the next decade” with allies and partners.8 On America’s defense posture in the region, the Biden strategy refers to AUKUS in the context of reinforcing and strengthening deterrence and bringing together European and Indo-Pacific partners. The AUKUS technology agenda fits neatly into the strategy’s priority list for Indo-Pacific defense priorities: We will foster security ties between our allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, including by finding new opportunities to link our defense industrial bases, integrating our defense supply chains, and co-producing key technologies that will shore up our collective military advantages. As we do, we will bring together our Indo-Pacific and European partners in novel ways, including through the AUKUS partnership.9 There is substantial continuity between the Trump and Biden Administrations in terms of American force posture in the Indo-Pacific. The National Security Strategy released by then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis in 2018 defines key desired attributes of U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific: Forward force maneuver and posture resilience. Investments will prioritize ground, air, sea, and space forces that can deploy, survive, operate, maneuver, and regenerate in all domains while under attack. Transitioning from large, centralized, unhardened infrastructure to smaller, dispersed, resilient, adaptive basing that include active and passive defenses will also be prioritized.10 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength This is particularly relevant to U.S. thinking about Australia’s strategic geography and the potential for American forces to operate with their Australian Defence Force (ADF) counterparts in and from the north of Australia. Since 2010, the U.S. Marine Corps has been staging annual six-month to eight-month rotational deployments to Darwin in the Northern Territory. The U.S. Air Force has been staging increasing numbers of flights from Australia’s northern air bases. Current planning seeks to intensify this cooperation. At the most recent annual Australia–U.S. Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) talks in September 2021, bringing the U.S. Secretaries of State and Defense together with their Australian counterparts, the Secretaries and Ministers endorsed the following areas of force posture cooperation: l l l Enhanced maritime cooperation by increasing logistics and sustainment capabilities of U.S. surface and subsurface vessels in Australia. Enhanced land cooperation by conducting more complex and more integrated exercises and greater combined engagement with Allies and Partners in the region. Establish a combined logistics, sustainment, and maintenance enterprise to support high‑end warfighting and combined military operations in the region.11 Without much attention being drawn to it, the U.S. is investing substantially in building a fuel facility near Darwin, to be completed in September 2023, which will be able to store 300 million litres (nearly 80 million U.S. gallons) of military jet fuel.12 Taken together with the arrival of AUKUS, it seems clear that American thinking about Australia’s strategic value in the Indo-Pacific is changing. Northern Australia is becoming more important to support a dispersal strategy, while Australia’s potential as a supply and sustainment hub is growing. An Australian Defence Force operating nuclear-powered submarines (in all probability Virginia-class The British Agenda for AUKUS In March 2021, the U.K. government released a policy statement, Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy. The statement argued that “the Indo-Pacific will be of increasing geopolitical and economic importance, with multiple regional powers with significant weight and influence, both alone and together.”14 As a result, Britain would “tilt to the Indo-Pacific,”15 in part as a response to the competitive challenges presented by China. The policy shift was underscored by a deployment to the Indo-Pacific of the Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier and a maritime strike group in late 2021. Not all in the U.K. are convinced that the “tilt” will survive after the Prime Ministership of Boris Johnson, the chief architect of the policy. The judgment of Peter Ricketts, now in the House of Lords after a career at the heart of British foreign policy, is unambiguous: “A tilt to the Indo-Pacific is a slogan not a strategy. It does not match closely enough the pattern of Britain’s vital interests to become the basis for a durable national strategy.”16 Ricketts does The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 25 l Enhanced air cooperation through the rotational deployment of U.S. aircraft of all types in Australia and appropriate aircraft training and exercises. SSNs) along with an array of interoperable platforms, sensors, and weapons is valuable. Combine that with key elements of equipment production and prepositioning in Australia along with access to ADF bases and national infrastructure, and this becomes a powerful force multiplier for the U.S. military at great distance from the continental U.S. Are there risks to the United States in pursuing a closer defense relationship with Australia? All alliances impact autonomous decision-making to some degree. However, nothing can replace the value of Australia’s strategic geography to the south of the Asian mainland. Just as in the Second World War, a major military campaign focused on the Western Pacific would find Australia a vital piece of geography for the United States. The U.S. must factor in occasional political differences between Canberra and Washington that may impact the conduct of operations. For example, how would the two countries manage political decision-making in support of military operations mounted from Australian territory? Nevertheless, over the 70-year life of the ANZUS treaty,13 Australia and the United States have had a remarkable confluence of shared strategic interests, and this confluence is only being reinforced by the rise of an assertive Beijing. accept, though, that an active foreign policy in Europe and deeper engagement in the Asia–Pacific “are not mutually exclusive.”17 Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a reminder that Europe and the U.K. face more immediate strategic threats in their own neighborhood. This, appropriately, will be a primary driver of British defense policy. However, enabled by the size of its economy and population and driven by a nationalist and assertive ideology, the PRC will remain the biggest long-term strategic challenge to global stability. Whether acknowledged or not, all countries are tilting to the Indo-Pacific. After Brexit, the U.K. is looking for markets and economic prospects in the region. This mix of risk and reward is likely to sustain a long-term British interest in the Indo-Pacific, perhaps best regarded as a second-level security priority after the existential threat presented to Europe by a revanchist Russia. AUKUS is a prime enabler for the U.K. to pursue its agenda for an Indo-Pacific tilt. The two policy objectives of enhanced trilateral cooperation and a stronger British presence and interest in the Indo-Pacific align comfortably. In a perfect policy world, AUKUS should add momentum to independent British efforts to pursue a tilt to the region. From a British perspective, AUKUS cements a stronger bilateral relationship with the U.S. that is quite separate from NATO or other European connections. If the aspired level of technology cooperation is achieved, AUKUS lifts the U.K. and Australia into a closer and stronger relationship with the United States relative to any other ally or partner. Britain will probably also assess that a close AUKUS industrial partnership will strengthen its defense export position relative to European competitors. AUKUS and Australia The arrival of AUKUS reflects a strong Australian interest to seek support from like-minded democracies in what has been a protracted and complicated set of disputes with China. In 2018, Australia became one of the first countries to exclude PRC companies, in particular Huawei and ZTE, from participating in the rollout of the 5G network. Canberra has also passed laws banning PRC funding of political parties, prevented at least some Chinese acquisitions of critical infrastructure, and modernized anti-espionage and anti-covert interference laws. Following thenPrime Minister Scott Morrison’s call for an international investigation into the origin of the Covid-19 26 virus, Beijing retaliated with official and unofficial bans on Australian exports including coal, barley, wine, beef, seafood, and other commodities. From a defense perspective, Australia has been particularly concerned about the PRC’s illegal annexation of much of the South China Sea and its cultivation of political influence with Australian state governments, with Pacific Island countries, and in Southeast Asia. A Defence Strategic Update issued in 2020 concluded that: Previous Defence planning has assumed a tenyear strategic warning time for a major conventional attack against Australia. This is no longer an appropriate basis for defence planning. Coercion, competition and grey-zone activities directly or indirectly targeting Australian interests are occurring now.… Reduced warning times mean defence plans can no longer assume Australia will have time to gradually adjust military capability and preparedness in response to emerging challenges. This includes the supply of specialised munitions and logistic requirements, such as fuel, critical to military capability.18 In responding to these developments, Canberra has sought to deepen alliance cooperation with the United States significantly, build closer defense ties with Japan and India, and restate the importance of cooperation between countries that support the international rule of law. There is bipartisan political and domestic popular support for lifting defense spending beyond the current level of 2.1 per cent of gross domestic product, as well as for establishing the conditions for domestic production of a range of missiles for ADF and allied use, expanding offensive and defense cyber capabilities, and looking for other ways to increase ADF range and firepower to boost deterrence. Australian governments have recognized that emphasizing force structure improvements—replacing aging submarines and surface vessels, for example—that would not deliver new capabilities until well into the 2030s was a major weakness in defense planning. AUKUS therefore addresses five identified Australian strategic needs. l It seeks to engage the United States more closely, giving Washington reason to put higher value on its alliance with Australia. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength l l l l British involvement is welcomed by Canberra as a way of signaling that likeminded democracies will work together to resist the PRC’s challenge to the global order. This is a way of internationalizing what has been a difficult bilateral struggle between Canberra and Beijing. AUKUS offers the possibility of fast-tracking the acquisition of new military technology that will strengthen deterrence and give the ADF a technology edge. AUKUS underpins a strategic judgment that the defense of Australia is something that can be credibly assured only within an alliance context, so the ADF needs to have the best possible levels of interoperability with the U.S. military. AUKUS addresses a central policy failure spanning several Australian administrations, which is the inability to find more capable replacements for the ADF’s high-quality but aging Collins-class submarines. The Submarine Strategy Prior to the AUKUS announcement, Australia was planning to replace its six Collins-class conventional attack submarines with 12 locally built French-designed submarines designated the Attack-class. The aim as stated in the 2016 Defence White Paper was to produce 12 “regionally superior The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 27 Australian critics of AUKUS argue that the agreement draws the country too closely into the U.S. rivalry with China. Hugh White, for example, argues that “we cannot take it for granted the US will solve our China problem for us. On the contrary, our ally will probably fail us. Americans will find that it will cost them more than it is worth to maintain leadership in Asia against China’s formidable challenge.”19 White’s critique is based on his concluded view that China will not be deterred from seeking dominance in the Indo-Pacific. Australian national security policymakers do not accept that position, preferring instead to argue that a close alliance with the United States helps to strengthen deterrence. It is certainly true, though, that an alliance made closer through AUKUS will lift American expectations about what Australia should be able to contribute to that collective defense effort. submarines with a high degree of interoperability with the United States.” The “key capabilities” of these submarines “will include: anti-submarine warfare; anti-surface warfare; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; and support to special operations.”20 By 2020, Prime Minister Scott Morrison had formed doubts about whether the Attack class would provide that regionally superior capability at the time of initial delivery around the mid-2030s. Morrison directed a small team in the Defence Department to identify alternative submarine designs. By the time of the G-7 meeting in Cornwall in the United Kingdom, Biden, Johnson, and Morrison had agreed privately on the broad shape of AUKUS cooperation, noting that “the strategic context in the Indo-Pacific was changing and that there was a strong rationale for deepening strategic cooperation between the three governments.”21 It was a remarkable step made possible only by the presidential decision to allow Australia access to nuclear technology. In my personal experience as Deputy Secretary for Strategy in the Defence Department between 2009 and 2012, the United States Navy and wider national security system was not in any way disposed to give Australia access to submarine nuclear propulsion technology. Australian officials had raised the issue on several occasions only to be politely but firmly rebuffed. The U.S. Navy’s interest was in assisting Australia to strengthen its capacity for conventional attack submarine operations. Media reports suggest that there are substantial reservations in the U.S. Navy about the AUKUS plan to develop an Australian SSN. For example, Randy Schriver, a former Assistant Secretary of Defense in the Trump Administration, identified “many potential obstacles on both sides” including from the U.S. Navy. Schriver told The Australian newspaper that there needed to be “sustained commitment from the senior political leaders in both capitals, otherwise the chances of Australia deploying its own nuclear submarine will drop below 50 per cent.”22 In effect, the decision to proceed with finding a pathway for Australia to access SSNs could have come only from President Biden. From an Australian perspective, an essential part of the 18-month “pathway” to March 2023 is to assure the U.S. Navy, Department of Energy, and other parties that Australia is capable of handling this transfer of intellectual property and technology securely and safely. An Australian Nuclear Powered Submarine Taskforce was established to work with the U.K. and U.S. on defining an 18-month pathway to development of an acquisition strategy. Key issues that the pathway is intended to address are “[s]ubmarine design, construction, safety, operation, maintenance, disposal, regulation, training, environmental protection, installations and infrastructure, industrial base capacity, workforce, and force structure.”23 Compared to normal Defence business processes, this work is happening at breakneck speed, and measurable progress is being made. By December of 2021, a key parliamentary committee agreed to a U.S.–U.K.–Australia treaty enabling the exchange of naval nuclear propulsion information, an essential platform for classified information sharing. The committee noted that “the Australian Government has approved funding of up to $300 million for the operation of the Nuclear Powered Submarine Task Force. As of 25 November 2021, the task force had 134 staff.”24 By May 2022, that staff had grown to 226 people—by Australian standards a significant policy commitment.25 In the United States, a bipartisan congressional working group announced in June 2022 that the Australia–U.S. Submarine Officer Pipeline Act was being introduced to ”establish a joint training pipeline between the U.S. Navy and the Royal Australian Navy” and “enable the start of U.S.-based training of Commanding Officers for Australia’s future fleet of nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS alliance.”26 Given the rapid worsening of the strategic outlook in the Indo-Pacific, much attention has been paid to how quickly a nuclear propulsion capability could be delivered to Australia. A complicating factor is that the Morrison government insisted that the nuclear submarines could be built in Adelaide, South Australia. To put it mildly, this is a major commitment, well ahead of current Australian industrial capability. The head of the Nuclear Powered Submarine Task Force, Vice Admiral Jonathan Mead, has said that outside of weapons fit, no design changes would be made to a choice between either the British Astute-class or American Virginia-class SSNs. Mead has acknowledged that, given design priorities in the U.K. and U.S., “new versions, the American SSNX and the British SSNR, will be in the mix.”27 In January 2022, U.K. Foreign Secretary Elizabeth Truss commented to the Australian media that 28 there could be the possibility of “collaborative development by the three AUKUS parties rather than a choice of Britain’s Astute-class or America’s Virginia-class.”28 There is promise in that approach, which could produce a design common to all three navies along lines like the common development approach used for the Joint Strike Fighter. There is intense speculation in Australia that it might be possible to lease or acquire a U.S. Virginia-class SSN in U.S. service, reflagging the boat as Australian before 2030 and before construction of Australian SSNs. Peter Dutton, Australia’s Minister for Defence up to the May 2021 election and now leader of the centre-right Opposition, claims that: I believed it possible to negotiate with the Americans to acquire, say, the first two submarines off the production line out of Connecticut. This wouldn’t mean waiting until 2038 for the first submarine to be built here in Australia. We would have our first two subs this decade. I had formed a judgment that the Americans would have facilitated exactly that.29 For that to happen, Biden or his successor would have to conclude that there was value in giving Australia access to these boats ahead of the U.S. Navy’s own demands for more submarines. The advantage to the U.S. is that Australia would pay for the capability, allowing an expansion of a larger “federated” submarine presence in the Indo-Pacific. However, no one should underestimate the costs and challenges ahead in realising this Australian capability in every area from construction and sustainment to basing, crew training, safety, and operational planning. The Wider AUKUS Technology Agenda In addition to nuclear propulsion, the September 2021 AUKUS announcement identified four “high priority areas” for collaborating work: cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and additional undersea capabilities. Further, in April 2022, Biden, Johnson, and Morrison met virtually to review progress on the AUKUS agenda and added some new categories for increased collaboration: “We also committed today to commence new trilateral cooperation on hypersonics and counter-hypersonics, and electronic warfare capabilities, as well as to expand information sharing and to deepen cooperation on defense innovation.”30 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Little has been publicly released about progress to date. A tripartite senior officials’ group has been appointed to oversee progress. In Australia, the Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet is the representative, while U.K. and U.S. National Security Advisers Stephen Lovegrove and Jake Sullivan, respectively, lead for their countries. Two joint steering groups have been established: one focused on submarines and the other covering all other nominated areas of advanced technology. Working groups have been established for each technology. To date, a work plan has not been released. On April 5, 2022, the partners released a fact sheet reporting the following meetings: l l “The three countries have held multiple Joint Steering Group meetings for each of the two AUKUS lines of effort, including in-person meetings in Canberra, London, and Washington, D.C.”32 “Seventeen trilateral working groups have been established (nine relating to nuclear-powered submarines, and eight to other advanced military capabilities); each has met multiple times.”33 On April 1, 2022, it was announced that a bipartisan AUKUS Working Group, also known as the “AUKUS Caucus,” had been formed in the U.S. Congress. Its members, drawn from both the Democratic and Republican parties, are intent on “provid[ing] a forum for congressional attention on the implementation of AUKUS and on completing the steps needed to strengthen our already-existing security relationship.”34 Three areas of weapons development activity that have been publicly revealed may be taken as examples of what could emerge from AUKUS cooperation. First, in April 2022, the AUKUS leaders reviewed progress on implementation and, on autonomous systems, said: “Through the AUKUS Undersea Reactions to AUKUS Robotics Autonomous Systems (AURAS) project, International reactions to AUKUS were varied our nations are collaborating on autonomous un- and largely divided on lines reflecting the stratederwater vehicles, which will be a significant force gic competition for influence in the Indo-Pacific. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 29 l “On March 10, 2022, National Security Advisors from the three allies met virtually to review AUKUS progress and provide direction to the trilateral partnership going forward.”31 multiplier for our maritime forces. Trials and experimentation of this capability are planned for 2023.”35 In May 2022, during the election campaign, then-Defence Minister Peter Dutton announced plans to fast-track the acquisition of three Extra Large Autonomous Undersea Vehicles (XLAUV).36 For a planned cost of USD$100 million, the boats are to be built in Australia over three years in a co-development project between the Australian Defence Organisation and U.S. company Anduril.37 The boats are said to be capable of long endurance and multi-mission roles. Second, a large investment in cyber capability was announced in the March 2022 Australian budget. Project REDSPICE—an acronym standing for Resilience, Effects, Defence, Space, Intelligence, Cyber and Enablers—will invest an additional AUS$9.9 billion over the coming decade in a range of areas, including tripling the size of the Australian Signals Directorate’s offensive cyber capability. In terms of cooperation with the U.S. and U.K., ASD claims that Project REDSPICE will enable “[g]reater integration through expanded global footprint,” “[c]o-investment in Five-Eyes initiatives,” and “[c]ollaboration on AI and cyber technologies.”38 Finally, without providing details, the Australian government has alluded to “collaboration with the United Sates to develop hypersonic missiles” as part of wider plans to develop a local missile manufacturing capability and increase stock holdings of U.S. missiles, including Tomahawk cruise missiles; joint air-to-surface standoff missiles (extended range); long-range anti-ship missiles (extended range); and precision-strike guided missiles for land forces with a range of over 400 kilometres.39 In April 2022, the government announced that “Raytheon and Lockheed Martin have been chosen to deliver the Sovereign Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance Enterprise (GWEO), to initially enhance self-reliance and supply chain resilience, but with a future goal of developing a guided weapons manufacturing capability in Australia.”40 It is clear that the project is intended to support U.S. missile requirements in the Indo-Pacific as much as it is to expand the ADF’s missile capabilities. Countries that welcomed the agreement included Japan, Singapore, and the Philippines. While Vietnam remained silent on the subject, it is assumed that it tacitly approves. France was critical based on the difficult reality that AUKUS ended its contract to design and build conventionally powered submarines in Australia.41 The change of government in Australia has opened the way to resuming a more positive bilateral relationship between Canberra and Paris. Predictably, the PRC was a strident critic. A Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson condemned the agreement, claiming that: Cooperation on nuclear-powered submarine technology between the US, the UK and Australia will gravely undermine regional peace and stability, aggravate arms race and impair international nuclear non-proliferation efforts. It runs counter to regional countries’ wishes. The three countries should discard the Cold War zero-sum mentality and narrow geopolitical perspective, follow the trend of the times for peace and development, and stop forming exclusive blocs or cliques.42 Concerns about a supposed proliferation risk were aired by Indonesia and Malaysia. In May, Prime Minister Ismail Sabri of Malaysia told Japan’s Nikkei newspaper that “We are worried that some other major economies will take advantage of AUKUS. For example, if China wants to help North Korea purchase nuclear-powered submarines, we can’t say no because AUKUS has set a precedent.”43 Australia continues to make the case in Southeast Asia that it has no intention of acquiring nuclear weapons. All three AUKUS partners maintain that the agreement to provide Australia with a pathway to nuclear propulsion does not compromise their support for nuclear non-proliferation. The AUKUS countries advised the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that a critical objective of their cooperation will be to maintain “the strength of both the nuclear non-proliferation regime and Australia’s exemplary non-proliferation credentials.”44 One important task for the AUKUS partners will be to determine whether any other countries should be allowed to participate in the broader technology development programs being advanced by the agreement. In an interview with the Australian Strategic 30 Policy Institute (ASPI) in November 2021, Japan’s ambassador to Australia said, “We have been told there are some instances or areas where AUKUS members may need Japanese cooperation and participation and we are more than willing to do our contribution.”45 With two AUKUS members in NATO, it is relevant that the recently released NATO Strategic Concept commits the alliance to “promote innovation and increase our investments in emerging and disruptive technologies to retain our interoperability and military edge.”46 This too could create a basis for expanding AUKUS cooperation, although hopefully without a loss of focus and pace, which are key aspects of the AUKUS strategy. Next Steps A defining event in AUKUS’s short history will be in March 2023 when officials are projected to bring to the President and the two Prime Ministers the plan for how Australia can acquire nuclear-propelled submarines. Australia’s new Defence Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, Richard Marles, has said that he hopes to achieve three key outcomes at that time. The first is an identified submarine type, which amounts to a choice between the U.S. Virginia-class or British Astute-class SSNs or their design successors. Second, it is expected that the advice in March 2023 will identify a realistic time frame for the Australian submarine acquisition. Finally, Marles has said that he wants to understand options for an interim conventional submarine replacement if there is a gap between the end of life of the Collins-class submarines and the arrival of the SSNs.47 The Australian Defence Organisation is working on the third of these options in parallel with the AUKUS study. At this stage, there is little on the public record indicating timelines for developments in the other technology areas. A potential critical waypoint will be the AUSMIN Ministerial meeting, which is due to be held in Australia toward the end of 2022. Given the priority that recent AUSMIN meetings have put on strengthening interoperability between the ADF and U.S. forces and on shared technology development, we should expect that the United States and Australian governments will put a high priority on the AUKUS agenda’s leading to the quickest possible deployment of new military capabilities. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength A further risk is that once the 18-month study into Australia’s nuclear propulsion options is concluded in March 2023, U.S. officials might conclude that Australia does not have the capacity or resolve to adopt nuclear propulsion. By then, the Albanese government will have a clearer sense of the cost involved. A Labor government might conclude that the cost is too high, although against that, Labor would have to balance the negative implications for wider alliance cooperation. Alliance relationships work best when they are delivering practical outcomes that benefit all parties. In short, AUKUS needs some practical results, including in areas where the fast delivery of capability will show the value of each country’s changing long-standing industrial and procurement practices. While that is clearly the aim of officials working on AUKUS delivery, we should not underestimate the challenges. Will the U.S. Congress, for example, really support the early delivery of a Block IV Virginia-class SSN to Australia ahead of the U.S. Navy’s own requirements? To date, congressional backing for AUKUS has been vocal and impressive, but in all three countries, local industrial and political perspectives will have to be acknowledged. On balance, there is more for the AUKUS countries to gain by continuing cooperation under the agreement than there is by backsliding. Biden’s personal investment in AUKUS is such that a failure to deliver tangible outcomes would damage the Administration’s position, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region, weakening future options for the U.S. military posture in the Western Pacific. For Australia, the costs of an AUKUS backdown would likely have an election-losing consequence for any Australian government. The U.K. has perhaps the least to lose if AUKUS fails to deliver, but London has much to gain if it can shape a closer industry and technology relationship with Washington. Conclusion Speaking at Singapore’s Shangri La Dialogue in June 2022, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin summed up the value of AUKUS: That’s another reason why our new security partnership with Australia and the U.K. is so important. AUKUS won’t just deliver nuclear-powered submarines. It holds out the promise of progress across a range of emerging tech areas that can bolster our deterrence, from AI to hypersonics.51 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 31 What Could Go Wrong? For all its promise, a lot could happen to derail AUKUS. The agreement is too disruptive of existing policy processes to have come from officials, and AUKUS would not have proceeded without the personal commitment of President Biden, Boris Johnson, and Scott Morrison. On May 21, 2022, Morrison’s government was defeated in Australia’s federal election. The new centre-left Labor government of Anthony Albanese has pledged to continue with AUKUS, although there are elements of the Labor Party that oppose nuclear propulsion. Labor depends on support from minor parties in the Senate, which in some cases are adamantly opposed to AUKUS and the alliance with the United States. Whatever the views inside the Labor Party, AUKUS was popularly received by Australians. A poll conducted in March 2022 found that 52 percent of those surveyed thought AUKUS would make Australia safer, while 70 percent surveyed were in favor of acquiring nuclear propelled submarines.48 As for Boris Johnson, in addition to having become deeply unpopular with British voters, he narrowly survived a vote of no confidence in his leadership from Conservative Party members of Parliament in early June and was finally forced to resign on July 7.49 The Conservative Party is going through lengthy mandated processes to select a new party leader and therefore Prime Minister by October 2022. It would be surprising if a new Conservative Prime Minister opposed AUKUS, but beset with domestic and international problems, a new British PM might not give AUKUS the priority that Boris Johnson did. The British Labour Party maintains support for the U.K.’s own submarine-based nuclear deterrent (although this is a contested position within the party) and has also indicated support for AUKUS.50 While President Biden has indicated an intention to run for a second term, his age is giving rise to speculation about his capacity to continue in office. All three of the original AUKUS leaders could therefore be out of office before the agreement delivers tangible progress on any defense capability plan. Would a re-elected Donald Trump continue AUKUS? It must be said that while Trump was skeptical of NATO, in office he was a strong supporter of the alliance with Australia and bilateral partnership with the U.K. Much could depend on how Trump or any future Republican President might choose to engage with Beijing. The defining words here are surely “the promise of progress.” AUKUS offers a remarkable new stage of alliance cooperation that will substantially lift Australian defense capabilities and strengthen allied military forces in the Indo-Pacific with exotic new technology. If AUKUS succeeds, it will be transformative. If for whatever reason AUKUS fails, that would do lasting damage to the United States’ position in the Indo-Pacific and to the position of the U.K. and Australia as America’s closest allies. The next 12 months will be hugely consequential as officials work to deliver a viable path forward. 32 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Endnotes 1. “Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS,” The White House, September 15, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statementsreleases/2021/09/15/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus/ (accessed July 7, 2022). 2. Ibid. 3. “The Strategic Reverberations of the AUKUS Deal Will Be Big and Lasting,” The Economist, September 19, 2021, https://www.economist.com/ international/2021/09/19/the-strategic-reverberations-of-the-aukus-deal-will-be-big-and-lasting (accessed July 7, 2022). 4. “Remarks by President Biden, Prime Minister Morrison of Australia, and Prime Minister Johnson of the United Kingdom Announcing the Creation of AUKUS,” The White House, September 15, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/09/15/remarks-bypresident-biden-prime-minister-morrison-of-australia-and-prime-minister-johnson-of-the-united-kingdom-announcing-the-creation-of-aukus/ (accessed July 7, 2022). 5. Prime Minister Tony Abbott, statement to Parliament of Australia on visit by Chinese Prime Minister Xi Jinping, November 17, 2014, https:// parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=CHAMBER;id=chamber%2Fhansardr%2F35c9c2cf-9347-4a82-be89-20df5f76529b%2 F0003;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F35c9c2cf-9347-4a82-be89-20df5f76529b%2F0005%22 (accessed July 7, 2022). 6. Reuters, “China, Britain to Benefit from ‘Golden Era’ in Ties—Cameron,” October 17, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-britainidUSKCN0SB10M20151017 (accessed July 7, 2022). 7. David Brunnstrom and Michael Martina, “Xi Denies China Turning Artificial Islands into Military Bases,” Reuters, September 25, 2015, https://www. reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-pacific-idUSKCN0RP1ZH20150925 (accessed July 7, 2022), and “FACT SHEET: President Xi Jinping’s State Visit to the United States,” The White House, September 25, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/25/fact-sheetpresident-xi-jinpings-State-visit-united-States (accessed July 7, 2022). 8. Executive Office of the President, National Security Council, Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States, February 2022, p. 5, https://www. whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf (accessed July 7, 2022). 9. Ibid., p. 13. 10. James Mattis, Secretary of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, U.S. Department of Defense, p. 6, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-DefenseStrategy-Summary.pdf (accessed July 8, 2022). Emphasis in original. 11. Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Joint Statement Australia–U.S. Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) 2021, September 16, 2021, https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/united-states-of-america/ausmin/joint-statement-australia-us-ministerial-consultationsausmin-2021 (accessed July 7, 2022). 12. Melissa Mackay, “Work Begins on $270 Million US Fuel Storage Facility on Darwin’s Outskirts,” ABC [Australian Broadcasting Corporation] News, January 18, 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-01-19/work-begins-on-us-jet-fuel-facility-outside-darwin/100764194 (accessed July 7, 2022). 13. U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, “The Australia, New Zealand and United States Security Treaty (ANZUS Treaty), 1951,” https:// history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/anzus (accessed July 8, 2022). 14. HM Government, Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty, CP 403, March 2021, p. 27, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/975077/Global_Britain_in_a_Competitive_Age-_the_Integrated_Review_of_Security__ Defence__Development_and_Foreign_Policy.pdf (accessed July 7, 2022). 15. Ibid., pp. 60 and 66–67. 16. Peter Ricketts, Hard Choices: What Britain Does Next (London: Atlantic Books, 2021), p. 227. 17. Ibid. 18. Australian Government, Department of Defence, 2020 Defence Strategic Update, p. 14, para. 1.13, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/ publications/2020-defence-strategic-update (accessed July 7, 2022). Emphasis in original. 19. Hugh White, “We Need to Talk About China—and then Actually Do Something About Our Own Security,” The Australian, June 25, 2022, https:// www.theaustralian.com.au/inquirer/we-need-to-talk-about-china-and-then-actually-do-something-about-our-own-security/news-story/97dcb2 c562d8f81304e1f223306f1b1c (accessed July 8, 2022). Subscription required. 20. Australian Government, Department of Defence, 2016 Defence White Paper, p. 90, para. 4.25, https://www.defence.gov.au/about/ publications/2016-defence-white-paper (accessed July 8, 2022). See also ibid., p. 90, para. 4.26. 21. “Readout: Trilateral Meeting of Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the United Kingdom, President Joe Biden, and Prime Minister Scott Morrison of Australia,” The White House, June 12, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/12/readout-trilateralmeeting-of-prime-minister-boris-johnson-of-the-united-kingdom-president-joe-biden-and-prime-minister-scott-morrison-of-australia/ (accessed July 8, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 33 22. Adam Creighton, “Australia May Not Get Any Sub from AUKUS Warns Former Trump Official,” The Australian, January 16, 2022, https://www. theaustralian.com.au/nation/defence/australia-may-not-get-any-sub-from-aukus-warns-former-trump-official/news-story/751c928ccc91ebd5d9 19edcff51961ca (accessed July 15, 2022). Subscription required. 23. See Australian Government, Department of Defence, “Nuclear Powered Submarine Taskforce: Frequently Asked Questions: What NuclearPowered Submarine Will Australia Be Acquiring?” https://www.defence.gov.au/about/taskforces/nuclear-powered-submarine-task-force/ frequently-asked-questions (accessed July 8, 2022). 24. Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, Report No. 199, Agreement for the Exchange of Naval Nuclear Propulsion Information, December 2021, p. 14, para. 2.55, https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportjnt/024853/ toc_pdf/Report199.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf (accessed July 8, 2022). 25. Brendan Nicholson, “Australia Considering Next-Generation US and UK Designs for Nuclear Submarines,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, The Strategist, May 10, 2022, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australia-considering-next-generation-us-and-uk-designs-for-nuclear-submarines/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 26. Press release, “Gallagher, AUKUS Working Group Introduce New Bill to Establish Officer Training Pipeline for Australian Submarines,” Office of Congressman Mike Gallagher, June 15, 2022, https://gallagher.house.gov/media/press-releases/gallagher-aukus-working-group-introduce-newbill-establish-officer-training (accessed July 8, 2022). See also H.R. 8073, “To direct the Secretary of Defense to establish a joint training pipeline between the United States Navy and the Royal Australian Navy, and for other purposes,” 117th Cong., Introduced June 15, 2022, https://www. congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/8073?s=1&r=3 (accessed July 8, 2022). 27. Nicholson “Australia Considering Next-Generation US and UK Designs for Nuclear Submarines.” 28. Ticky Fullerton, “Deeper Defence Ties Vital to Counter China’s Influence, Says Liz Truss,” The Australian, January 19, 2022, https://www. theaustralian.com.au/nation/politics/defence-ties-vital-to-counter-china-truss/news-story/b78943dd035f3d52e604c05e779c124c (accessed July 8, 2022). Subscription required. See also Peter Jennings, “AUKMIN’s Global View Is Good for Australia,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, The Strategist, January 24, 2022, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/aukmins-global-view-is-good-for-australia/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 29. Peter Dutton, MP, “Opinion Piece for the Australian,” June 8, 2022, https://www.peterdutton.com.au/opinion-piece-for-the-australian/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 30. “AUKUS Leaders’ Level Statement,” The White House, April 22, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statementsreleases/2022/04/05/aukus-leaders-level-statement/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 31. “Fact Sheet: Implementation of the Australia–United Kingdom–United States Partnership (AUKUS),” The White House, April 5, 2022, https:// www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/05/fact-sheet-implementation-of-the-australia-united-kingdom-unitedstates-partnership-aukus/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 32. Ibid. 33. Ibid. 34. Press release, “Reps. Courtney, Gallagher, Kilmer, and Moore Announce Formation of the New Bipartisan AUKUS Working Group, in Support of the Undersea Alliance Between the U.S., U.K., and Australia,” Office of Congressman Joe Courtney, April 1, 2022, https://courtney.house. gov/media-center/press-releases/reps-courtney-gallagher-kilmer-and-moore-announce-formation-new (accessed July 8, 2022). For an excellent summary of AUKUS developments, see Marcus Hellyer and Ben Stephens, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Strategic Insights No. 170, “ASPI AUKUS Update 1: May 2022,” https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2022-05/ASPI%20AUKUS%20update%201. pdf?VersionId=lB063VndLfT5t5YHsDDwHvxWnKViC4m1 (accessed July 8, 2022). 35. “Fact Sheet: Implementation of the Australia–United Kingdom–United States Partnership (AUKUS).” 36. Tom Ravlic, “Election 2022: Dutton Flags Robotic Undersea Warfare Capability,” The Mandarin, May 5, 2022, https://www.themandarin.com. au/188327-election-2022-dutton-flags-robotic-undersea-warfare-capability/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 37. Andrew McLaughlin, “Anduril & ADF to Partner on Autonomous Undersea Vehicle Development,” Australian Defence Business Review, May 5, 2022, https://adbr.com.au/anduril-adf-to-partner-on-autonomous-undersea-vehicle-development/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 38. Australian Government, Australian Signals Directorate, REDSPICE: A Blueprint for Growing ASD’s Capabilities, p. 18, https://www.asd.gov.au/sites/ default/files/2022-05/ASD-REDSPICE-Blueprint.pdf (accessed July 8, 2022). 39. The Hon. Scott Morrison MP, Prime Minister; The Hon. Peter Dutton MP, Minister for Defence; and Senator the Hon. Marise Payne, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister for Women, “Australia to Pursue Nuclear-Powered Submarines Through New Trilateral Enhanced Security Partnership,” joint media statement, September 16, 2021, https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/media-release/australiapursue-nuclear-powered-submarines-through-new-trilateral-enhanced-security-partnership (accessed July 8, 2022). 40. “Raytheon and Lockheed Martin to Deliver GWEO,” Australian Defence Magazine, April 5, 2022, https://www.australiandefence.com.au/ defence/joint/raytheon-and-lockheed-martin-to-deliver-gweo#:~:text=Raytheon%20and%20Lockheed%20Martin%20have,weapons%20 manufacturing%20capability%20in%20Australia (accessed July 8, 2022). 41. For a good summary of international reactions to AUKUS, see Hellyer and Stephens, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Strategic Insights No. 170, “ASPI AUKUS Update 1: May 2022.” 34 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 42. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s Regular Press Conference on September 22, 2021,” https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2511_665403/202109/t20210922_9580314.html (accessed July 8, 2022). 43. Associated Press, “Australia FM Stresses AUKUS Will Not Create Nuclear Weapons,” June 28, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/china-asiaaustralia-global-trade-b3bb95edec2baa9584fb8faead271222 (accessed July 8, 2022). 44. Press release, “IAEA on Trilateral Effort of Australia, United Kingdom, and United States on Nuclear Naval Propulsion,” International Atomic Energy Agency, September 16, 2021, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/iaea-on-trilateral-effort-of-australia-united-kingdom-andunited-states-on-nuclear-naval-propulsion (accessed July 8, 2022). 45. Jack Norton, “Japan ‘More than Willing’ to Help Ensure AUKUS Success,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, The Strategist, November 12, 2021, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/japan-more-than-willing-to-help-ensure-aukus-success/ (accessed July 8, 2022). 46. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” p. 7, para. 24, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/ pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf (accessed July 8, 2022). 47. The Hon. Richard Marles MP, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, “Interview with Peter Stefanovic, Sky News.” Australian Government, Department of Defence, July 1, 2022, https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/minister/rmarles/transcripts/interview-peter-stefanovicsky-news (accessed July 8, 2022). 48. Natasha Kassam, “Lowy Institute Poll 2022,” Lowy Institute, June 29, 2022, https://poll.lowyinstitute.org/report/2022 (accessed July 8, 2022). 49. Rowena Mason, “Boris Johnson Wins No-Confidence Vote Despite Unexpectedly Large Rebellion,” The Guardian, June 7, 2022, https://www. theguardian.com/politics/2022/jun/06/boris-johnson-wins-no-confidence-vote-despite-unexpectedly-large-rebellion (accessed July 8, 2022); Jim Pickard, “Boris Johnson Resigns,” Financial Times, July 7, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/db96be7d-7728-435a-af70-5b1ba3173e83#post55fdb4a7-68ac-40da-8839-92acd6476362 (accessed July 8, 2022); and Owen Amos, “Boris Johnson Resigns: Five Things That Led to the PM’s Downfall,” BBC News, July 7, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-62070422 (accessed July 8, 2022). 50. Latika Bourke, “British Labour Backs AUKUS Alliance but Would Punish Australia for Climate Inaction,” The Sydney Morning Herald, September 28, 2021, https://www.smh.com.au/world/europe/british-labour-backs-aukus-alliance-but-would-punish-australia-for-climate-inaction20210926-p58uy5.html (accessed July 8, 2022), and BBC News, “Labour Renews Vow to Keep Nuclear Weapons,” February 28, 2021, https:// www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-56198972 (accessed July 8, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 35 51. Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin, “Remarks at the Shangri-La Dialogue by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III (as Delivered), U.S. Department of Defense, June 11, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech/Article/3059852/remarks-at-the-shangri-la-dialogueby-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iii-a/ (accessed July 8, 2022). Recruiting the All-Volunteer Force: New Approaches for a New Era Richard Brady T We are now seeing some substantial problems. Changes in American culture, the rise of new technologies used by American youth to interact with the world around them, and fewer opportunities to be exposed to the military are making the recruiting effort extraordinarily difficult. Beyond making it harder to meet annual recruiting goals, this potentially calls into question the AVF’s viability and demands a number of improvements to and adaptations within the “accessions enterprise” if we are to continue to have the most competent, professional military possible. Military accessions—the process of recruiting, qualifying, and conducting initial entry training—is vital to our national security interests. Its operating environment is constantly evolving, and the organizations involved must respond in kind to remain relevant and accomplish their missions. This is particularly true of the recruiting portion of the accession environment, as recruiting tends to be the most visible and significant aspect of accessions. Recruiting is constantly affected by changing applicant demographics and expectations, service requirements and demands, accession policies, threats and security requirements, and technologies. The accession enterprise is made up of three components: l l l The service recruiting commands; The United States Military Entrance Processing Command (USMEPCOM); and The service recruit training sites. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 37 he National Defense Strategy defines the enduring mission of the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) as providing combat-credible military forces to deter war and protect the security of our nation. This requires the fielding of sufficient capable forces to defeat America’s enemies and protect the American people and our vital national interests.1 In 1973, the U.S. military undertook a dramatic change in how it populated the services, moving from a model that relied on a combination of young Americans who wanted to join and those who were drafted by order of the government. The volunteer or recruited model has been a feature of the military since the country was founded, and the services have made all sorts of efforts to attract young men—and later, women—to join the military. Recruiters have appealed to a sense of patriotism, a desire for experience or education, health care benefits, or even a steady paycheck. During periods of war, when the size of the military needed to be increased dramatically and very rapidly, the country employed a draft to fill the ranks, especially when casualties from combat needed to be replaced even by the unwilling. But the Vietnam war, occurring as it did during a period of great social and political upheaval in the U.S., led to a great rethinking about the military and what it needed to be. While not always the case, compelling draftees to serve in a controversial war during a time of domestic discord led to disciplinary problems in the military and declines in unit cohesion, effectiveness, and morale. The all-volunteer force (AVF) model was meant to improve the professionalism of the force, which it has, but it also depends on success in convincing young Americans in large numbers to join the force. Each component has a vital role in supporting the DOD mission by ensuring and supporting the quality and quantity of the AVF. Given some significant changes in the recruiting environment, all participants in the process must adapt their systems, processes, organizations, and mindsets to meet the annual requirement of recruits in an AVF. The military accession enterprise is experiencing structural, political, social, and technical shifts on a scale not seen since the all-volunteer force was adopted in 1973. It has been 50 years since the U.S. last drafted people, and the military services must address these shifts if they are to continue to be successful in populating our military with young Americans who are willing to serve our country. Military recruiting involves actions and activities taken by a service to identify and attract individuals in sufficient numbers to meet organizational needs. These actions include marketing, advertising, influencing, and educating to generate a pool of desirable candidates, enhance their interest and attraction to military service, and increase the probability that these individuals will enlist. Among the organizational needs to be met by this process are the end strength objective for each service (how large it needs to be) and personnel with the aptitude and skills required to serve in technical fields.2 DOD recruiting data highlight the challenge involved in accomplishing the accession mission.3 Service recruiting productivity and resultant USMEPCOM and service recruit training throughput continue to be challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in limited access to high school students and large student gatherings. But the COVID-19 challenges tell only part of the story. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated systemic issues—changing demographics, propensity, standards, technology, and methods—within the accession environment that had been building for years, and it will take more than the end of the pandemic to resolve them. The services have limited levers to influence near-term recruiting results. For applicants, these levers include waiving tattoo policies, weight standards, and education standards and providing higher enlistment bonuses. Recent headlines indicate that service recruiting commands are attempting to use a mix of these levers to improve recruiting outcomes in fiscal year (FY) 2022.4 Similarly, the services can increase recruiter productivity in the 38 near term through promotion and duty assignment preferences, monetary incentives, and involuntary extension of productive recruiters.5 The more important levers reside at the policy and societal levels where the quality and quantity of military service inductees can be properly balanced with a focus on long-term outcomes and costs to the accession enterprise. These levers include medical policies and standards, testing policies and standards, and youth propensity to serve. An appreciation for the role these levers play requires an understanding of the complex interplay of the organizations involved as well as the history of accession standards. A Balance of Interests: The Accession Triad The first leg of the accession triad includes the military service recruiting commands. Under Title 10 of the United States Code: The Secretary concerned may accept original enlistments in the Regular Army, Regular Navy, Regular Air Force, Regular Marine Corps, Regular Space Force, or Regular Coast Guard, as the case may be, of qualified, effective, and able-bodied persons who are not less than seventeen years of age nor more than forty-two years of age.6 The service secretaries carry out this mission largely through the recruiting force with oversight from service headquarters. In terms of a supply chain, the service recruiting commands are the first step in a long process that eventually results in military servicemembers being fielded to operational commands and adding to military readiness. Collectively, the service recruiting commands employ more than 20,000 recruiters worldwide to meet their annual recruiting requirements. Within the accession triad, service recruiting results receive the most visibility, as annual goals are used by both the public and private sectors to gauge military readiness and the willingness of young Americans to serve their country in uniform. In 1976, the Secretary of Defense established the United States Military Entrance Processing Command, the second leg of the accession triad. Initially established as a Department of the Army field operating agency under the jurisdiction of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, USMEPCOM was led 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength to meet quality and quantity metrics in most years. However, when recruiting quantity metrics begin to fall short, as experienced in FY 2022, the tension builds, upsetting the balance between quality and quantity. The military services must enlist a sufficient quantity of recruits to fill units in the operating forces and maintain readiness. If the quantity of recruits falls short, then the services must restructure operational units to ensure combat effectiveness.8 In terms of cold, hard metrics, quantity is valued more than quality. This has been true in both peacetime and in war. But starting in the early 20th century and as medicine and cognitive testing evolved, it became more difficult to ignore the quality aspects of recruits and the medical and mental fitness impacts on readiness. Evolution of the Accession Process Today’s modern accession standards originated with the United States’ entry into World War I. The declaration of war signed by President Woodrow Wilson on April 6, 1917, set in motion what would become by the end of the war the largest coordinated system of human resource selection, classification, training, and assignment ever implemented. During the 18 months the nation participated in World War I, uniform standards were devised to screen out the medically unsuitable and to assess the aptitude capabilities of enlistees. Medically, screening for tuberculosis was a priority as TB was a leading cause of death at the time. Height and weight standards were also first applied with uniformity during the World War I era.9 The application of these standards resulted in far more rejections of prospective servicemembers for underweight than for overweight. World War I also witnessed the advent of aptitude testing. The Army Alpha test consisted of eight subtests and served as a prototype for later test development. The Army Beta test was one of the first paper-and-pencil tests to evaluate the aptitude of recruits who had little or no schooling or who did not speak English. Both tests were eventually replaced by the Army General Classification Test (AGCT). More than 20 years later, World War II presented the nation with an even more monumental mobilization effort. By the time the wartime selective service laws expired in 1947, more than 10 million men had been inducted into the military services. The physical standards for induction were first published by The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 39 by a commanding general who was also commanding general of U.S. Army Recruiting Command. This arrangement remained in place until 1979 when USMEPCOM became a DOD field operating activity reporting to the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. This arrangement gave the Secretary of Defense greater oversight of the accession process through USMEPCOM’s mission of evaluating applicants by applying established DOD aptitude, medical, and moral standards during processing for military service. The Secretary of Defense’s authority over USMEPCOM and the accession process helps to ensure equality of opportunity for all eligible applicants for military service. The DOD uses common entrance qualification standards for enlistment, appointment, and induction across all military services. This helps to avoid inconsistencies and inequities linked to ethnicity, race, religion, or gender. Moreover, this enables the judgment of suitability for military service on the basis of an applicant’s adaptability, potential to perform, and conduct.7 The third leg of the accession triad is the service recruit training mission. The services, including the U.S. Coast Guard, maintain nine recruit training sites with the mission to transform civilian volunteers into professional servicemembers who are disciplined, fit, acculturated, and combat ready. To increase the likelihood of success, the service recruit training commands desire new recruits who are at high levels of medical and mental readiness before the start of training. All components of the accession triad—recruiting, USMEPCOM, and recruit training—must work cohesively to enlist approximately 250,000 men and women into the U.S. armed forces annually. This requires not only the integration of policies and systems, but also the balance of incentives and desired outcomes at each step of the process. Recruiting has the dual mission of quantity and quality with the former taking precedent over the latter. USMEPCOM has a near singular focus on quality and adherence to accession standards. Recruit training focuses on individual recruit readiness, which is a function of quality and training standards. Because of the divergent incentive structure, there is a natural tension among the three elements of the triad: recruiting, USMEPCOM, and recruit training. This tension has generally led to positive outcomes for the accession enterprise, allowing it the War Department in 1940.10 They were used by local draft board physicians and physicians at Joint Army and Navy Induction Stations. The physical standards changed as the war progressed, as medical science advanced, and as the needs of the War Department evolved. The most extensive changes involved dental and visual acuity standards and the PULHES physical classification system, all of which are still in use today.11 In 1948, an interservice working group was created to develop a single aptitude test for use by all services. This effort resulted in the introduction in 1950 of the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT). The AFQT served as a screening device, determining an applicant’s overall capacity to absorb military training, and provided a uniform yardstick with which to predict the individual’s potential for success while in service. The AFQT did not aid in job classification. For this, the services employed their separate examinations or specialized tests. In 1974, the DOD selected the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) as the single instrument of choice to screen applicants both for enlistment and for occupational classification testing. This streamlined the testing process and enhanced the individual service’s ability to match applicants with jobs and provide job guarantees to applicants who qualify. In 1976, the same year USMEPCOM was established, a revised version of the ASVAB became the enlistment eligibility test DOD-wide.12 Refined and improved versions of the ASVAB continue to serve in the 21st century. Medical fitness standards continue to be refined to keep pace with current trends in public health and advances in medical science and military requirements. Audiometric standards were added and hearing tests became routine.13 Screening for HIV was mandated in the 1980s for all persons entering the services.14 USMEPCOM incorporated International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) codes in 2015,15 and updated standards related to transgender applicants and the pandemic diseases were added between 2017 and 2021.16 Today, the DOD regularly evaluates the medical and testing standards applied to accession based on emerging science, research, and advances in technology. These efforts, intended to balance cost and performance in military enlistments, are nonetheless influenced by politics and public opinion. The shifts in policy governing military service 40 for transgender individuals between 2018 and 2021 and the COVID-19 medical standards and vaccine policies of 2020 and 2021 are cases in point. While these policies are of interest from a societal or public health perspective, their impact on military readiness is hotly debated. One thing is quite clear, however: They increase both the cost and the level of effort needed to recruit military personnel. Levers of Control: Medical, Testing, and Propensity The United States Army is projected to miss annual recruiting goals in FY 2022 and FY 2023, falling short by as many as 40,000 new recruits. General Joseph Martin, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, identified the unprecedented challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic environment, the labor market, and competition with private companies as key factors that negatively impact recruiting.17 These challenges have affected recruiter productivity by largely prohibiting large group events, curtailing widely attended sports or school events, and limiting the impact of traditional incentive schemes like bonuses. The Army, Army Reserve, and Army National Guard are the recruiting bellwether for all of the military services, accounting for nearly 50 percent of the annual DOD accession goal of 250,000 recruits. The traditional model of recruiting, which was effective before the COVID-19 pandemic, will not suffice in a post-COVID environment. Understanding this requires understanding the structural issues that determine whether a potential recruit desires to serve and is qualified to join. Finding medically fit, academically proficient, and motivated men and women is the foundational issue in military recruiting. Medical. DOD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1, “Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction,” establishes baseline accession medical standards.18 All applicants complete the same accession medical history process, which requires self-disclosure of medical history, authorization given to the military to access personal medical records, and a physical examination by a licensed medical professional. Uniform accession medical standards reduce the risk of long-term negative outcomes both for the servicemember and for the military services. The intent is to not aggravate any preexisting physical or mental health condition that might lead to the injury or death of the servicemember or a long-term cost 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength of medical history, which led to Existing Prior to Service (EPTS) attrition (early discharge of the servicemember because of undisclosed medical problems revealed during the servicemember’s first enlistment) and high costs to the DOD at recruit training and during first-term enlistment. USMEPCOM data consistently show that almost 50 percent of all EPTS attrition in all services is due to applicant nondisclosure of medical information.19 The principal reasons for EPTS in all services are (in order) psychological, orthopedic, and asthma (pulmonary). Applicants for military service undergo a USMEPCOM medical screening that includes a physical exam; urinalysis for protein, glucose, and illicit drugs; hearing; and vision.20 Applicants complete a report of medical history as well as behavioral questionnaires, both of which require the applicant to disclose any conditions, particularly in behavioral health, that would normally be disqualifying. For various reasons, from willful nondisclosure to poor recall, applicants tend not to reveal such information. According to a 2016 Accession Medical Standards Analysis and Research Activity (AMSARA) report, “the great majority of EPTS discharges are for medical conditions that were not discovered or disclosed at the time of application for service, with concealment by the applicant being the most common scenario.”21 Since these instances of nondisclosure are not uncommon, obtaining applicant medical and/or prescription records helps USMEPCOM medical providers to make the appropriate qualification decisions. In addition, the services, through their Service Medical Waiver Review Authorities (SMWRA), are better informed when conducting risk assessments during waiver reviews. In most cases, the relevant military medical authorities are able to acquire this important information, but the time needed to do so also means that it takes longer to process the applicant. Between 1997 and 2017, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) made several recommendations to improve recruit medical screening processes at USMEPCOM. The GAO’s 1997 report recommended that DOD develop methods to verify applicant medical history to decrease issues of nondisclosure that could lead to recruit injury, attrition, or even death.22 Its 2017 report highlighted concern with the lack of electronic interfaces between USMEPCOM and electronic medical information The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 41 to the government from a permanent disability. The stress of military service can result in a reoccurrence of some previous condition, whether resolved or unresolved. All components of the accession enterprise have a shared goal: finding young adults to meet the mission requirements of the military services and ensuring that they have every opportunity to pursue a successful military career. Accession medical standards are based on advances in medical science, changes in public health, operational needs, and prerogatives of the DOD and military services pertaining to sociopolitical or cultural issues. They are designed to ensure that individuals are physically and psychologically qualified and capable of performing the strenuous military duties that are often associated with wartime activities. This requires the applicant to be available for worldwide duty without restriction or delay; able to tolerate exposure to stressful, dangerous, and harsh environments; and able to operate dangerous, sensitive, or classified equipment. Applicants with conditions that would normally disqualify them are reviewed on a case-by-case basis by the relevant service to determine whether a medical waiver can be issued. Each service has its own waiver policy that typically calls for more information about the condition of the individual and treatments available to mitigate risk associated with the medical condition. This additional information helps the service to make a risk-informed decision on the applicant. Conditions that are more rarely waived include those involving behavioral health, including self-mutilation, suicidal attempts or gestures, major depression, bipolar disorder, or other similar conditions. As important as the military recruiting and accession processes are, they rely heavily on a patchwork of outdated technology and paper-based data collection for medical history. Until recently, this process was seen to serve both the needs of DOD and those of the services even though it was based on the assumption that the medical record provided by the applicant was complete and accurate. Based on this assumption, the DOD thought it was able to apply stringent accession medical standards, and this gave the impression that high quality standards were being met even though the services were recruiting applicants with largely unverifiable medical histories. Various studies and reports over the years identified this shortfall in validating applicant disclosure holders that would otherwise make it easier for Military Entrance Processing Stations (MEPS) to obtain medical history information.23 In 2016, USMEPCOM was directed to gain access to authoritative health information through a fully automated and electronic health record system to reduce the number of EPTS discharges and respond to the various problems noted in government reports. USMEPCOM conducted assessments, pilots, and initiatives between 2016 and 2020 to obtain this information and prepare for implementation. These efforts resulted in a system-of-systems approach that began with formal pilot programs in 2020 and an implementation plan in 2021. Medical modernization in USMEPCOM encompasses multiple systems that collectively provide access to an applicant’s health information and electronic health records. The systems include: l l l 42 MEPCOM Integrated Resource System (MIRS 1.1). MIRS is a cloud-based, enterprise processing system that provides centralized control and interface for accessions.24 Deployed in 2021, MIRS features increased maintainability, usability, security, and scalability compared to legacy systems. It supports medical processing through the scheduling and reporting of medical exams. Health Artifact and Image Management Solution (HAIMS). HAIMS provides global visibility and access to records and images generated during health care delivery.25 With access available at all MEPS and service recruit training sites, HAIMS supports the digitization and transmission of accession health records while reducing personally identifiable information (PII) and personal health information (PHI) exposure. Joint Longitudinal Viewer (JLV). JLV provides an integrated, read-only view of electronic health records from the DOD, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and health information exchanges.26 JLV primarily contains health information on prior service applicants and the dependents (spouses and children) of military servicemembers. It utilizes electronic health records held by DOD and VA to provide prescription history for beneficiary populations. l l Prescription Medication Reporting System (PMRS). A commercial application used primarily by the insurance industry, PMRS provides pharmacy history reports on individuals, including prescription drug dosage and refill information.27 PMRS primarily covers insured applicants who have no prior military affiliation and is compliant with both the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Fair Credit Reporting Act. Military Health System (MHS) GENESIS. MHS GENESIS is the next-generation DOD, VA, and Department of Homeland Security (for U.S. Coast Guard) electronic health record that covers accession through retirement.28 MHS GENESIS is a fully digital system that leverages authoritative data and reduces reliance on paper-based processes. Collectively, these systems provide end-to-end electronic health record coverage and access to authoritative health information while fully digitizing the accession medical process in a cloud-based environment. From an enterprise standpoint, they improve qualification decisions, reduce recruit training attrition (EPTS), and enhance policy formation at the DOD and service levels. In December 2021, USMEPCOM initiated the Medical Review of Authoritative Data (MROAD) program as the first step to address the problem of applicant nondisclosure. MROAD makes it possible for the military to obtain applicant prescription histories that are used to identify medical conditions contributing to avoidable attrition.29 MROAD leverages two complementary systems: JLV and PMRS. The data obtained from JLV and PMRS reports allow for a more comprehensive picture of applicants’ medical histories. In early 2020, USMEPCOM used MROAD to assess the use and impact of JLV and PMRS in the medical evaluation process. Only records of applicants already shipped to recruit training were reviewed so that the assessment did not affect actual qualification decisions. After reviewing the records of 1,545 applicants between April and June 2020, USMEPCOM found that nearly 7 percent of applicants had a prescription history suggesting non-waiverable medical conditions.30 Further analysis indicated that approximately 83 percent of applicants would be 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength fully qualified during the physical exam with an additional 10 percent receiving service medical waivers. The net impact on qualifications confirmed that applicants were not disclosing potentially disqualifying conditions, as the disqualification rate increased by nearly 7 percent overall. It was estimated that the savings associated with better qualification decisions totaled nearly $1 billion per year for the DOD and services at a financial cost of only $5 million per year. Interestingly, the results of the review also revealed that an additional 21,000 applicants need to be recruited each year to offset the number that are medically disqualified during prescreening for the services to meet their annual recruiting goals. The individual applicant findings were somewhat more startling. When the prescription history of applicants who had already assessed and shipped to recruit training during 2020 were reviewed, it was found that many had undisclosed, significant mental health conditions that would not be compatible with military service or success at recruit training. Examples included: l l l An applicant with 232 prescription fills for multiple psychiatric medications, USMEPCOM had processes and procedures in place to implement the use of PMRS and JLV when directed. This initiative addressed the historical problem of applicant nondisclosure of medical history and would have allowed USMEPCOM medical providers to make better informed risk-based decisions. The use of authoritative health information would also reduce the variance in medical decision-making and EPTS attrition, nearly 50 percent of which is due to applicants failing to disclose medically disqualifying information. Service recruiting commands were hesitant, preferring to implement MROAD in FY 2023. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, inability to gain access to schools and conduct large-scale events, and a young, less experienced recruiting force had created challenges to meeting recruitment goals. Recruiting commands were concerned that implementation of more stringent medical screening practices would decrease the pool of eligible applicants and increase the workload for recruiters. Any additional barriers to entry were seen as counterproductive. l l An applicant with over 100 prescription fills for ADHD and anti-depressives, and l An applicant who was prescribed lithium for bipolar disorder. The Council on Recruit Basic Training, an organization made up of the commanders and commanding generals of the service recruit training commands, supported medical modernization efforts if they reduced EPTS attrition at the initial entry training sites. Identifying medically disqualifying conditions would arguably prevent injury or death, minimize attrition rates, and increase graduation rates. Furthermore, applicants approved through the waiver process would sustain fewer injuries/illnesses if preventive measures were available. Such cases would not normally be granted a waiver for enlistment by the military services, yet they somehow “slipped through the system.” The decision to implement MROAD in actual qualification decisions was made in 2021. DOD developed several courses of action (COA) that balanced the need for medical modernization with the realities of the recruiting environment. While varyService medical review waiver authorities ing somewhat in their implementation start date largely favored the use of authoritative health and the use of medical history reports during the information in the accession process because course of the accession process, all of the COAs recit provided a more holistic picture of an appliommended better use of both electronic and paper cant's medical history and allowed for better medical records to determine whether an applicant determinations in cases involving medical needed a more comprehensive physical examination. waiver requests. Perhaps not surprisingly, the positions of agencies involved in the decision to implement recomThe DOD directed the implementation of mendations varied greatly, depending on their mis- MROAD beginning in FY 202231 against the strong sions and roles in the accession supply chain. reservations of the services. USMEPCOM was l The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 43 directed to provide implementing procedures to the services before the initiation of MROAD and to conduct an assessment of the program after six months of use. Military applicant medical disqualification rates began to increase immediately following the implementation of MROAD in December 2021. Additionally, the increase in the quantity of medical history that MEPS medical providers needed to review increased the timeline for medical evaluations. These two factors—higher disqualification rates and longer timelines—increased the risk of missed recruiting goals for the service recruiting commands. The services voiced their concerns in early 2022, and DOD decided to pause the MROAD program in anticipation of the deployment of MHS GENESIS.32 USMEPCOM deployed MHS GENESIS in the second and third quarters of FY 2022. Similar to the deployment of MROAD, the services strongly objected to the deployment of MHS GENESIS. They continued to be concerned about the negative impact that increased medical disqualification rates would have on service recruiting efforts, particularly in a year when all military services are struggling to meet their recruiting goals. Despite these concerns, determining that the improved quality of military applicants outweighed the services’ concerns about quantity and given the difficulty of the recruiting mission in FY 2022 and the likelihood that the services would miss recruiting goals in any event, DOD determined that FY 2022 was the best time to deploy MHS GENESIS. The deployment of MHS GENESIS marked the most significant change in medical qualification in a half-century and was the result of decades of work and research. USMEPCOM moved from a paper-based system to a modern health care system that provides “a single health record for service members, veterans, and their families”33 as well as better, more responsive access to authoritative health information. Its use not only has the direct impact of improving the quality of recruits enlisted in the military, but also provides improved insight into the overall health of the U.S. armed forces. These long-term benefits should not be outweighed by the short-term impacts being experienced by the service recruiting commands in meeting their quantity goals. Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Testing. The ASVAB is the world’s most widely used multiple-aptitude test battery and became so widely used 44 because of the evolutionary process by which it was developed and implemented—a process in which the U.S armed forces have played a central role. The process of administering standardized tests at the beginning of the 20th century was time-consuming and costly and required highly trained administrators. In 1917, American Psychological Association (APA) President Robert Yerkes urged the APA to contribute to the war effort by helping to find a way to assess recruits.34 The APA formed numerous committees, one of which was charged with developing a group intelligence test that could identify men with low intelligence and those who were well-prepared for special assignments or higher-level training. Their efforts resulted in the Army Alpha and Beta tests, introduced in 1917.35 The Army Alpha was a written test for literate recruits. It had various parts, including analogy recognition, missing number fillins, and sentence unscrambling. These types of questions are still common in modern IQ tests. The Beta version was used for men who did not speak English or were illiterate. It also had several parts, including a maze, number work, and picture completions. The Alpha and Beta tests could be administered to large groups and took less than an hour to complete. By the end of World War I, more than one million people had taken the Army Alpha and Beta tests. The Army used the tests for two primary reasons: to improve the assigning of new recruits and to allow military leaders to gain a better understanding of their soldiers’ individual abilities. The first tests were just the beginning of the journey for intelligence and aptitude testing within the U.S. military. During World War II, each service used its own assessment procedures before an individual’s induction. The War Department also began to use the Army General Classification Test and Navy General Classification Test to classify enlisted personnel.36 These tests included questions on vocabulary, arithmetic, and block counting. More than nine million people took these tests during the war. In 1948, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, which mandated that the newly formed DOD should develop a uniform screening test to be used by all of the services. In response, DOD developed the AFQT.37 DOD began to administer the AFQT in 1950 and continued to administer it until the mid1970s. The AFQT consisted of 100 multiple choice questions in vocabulary, arithmetic, spatial relations, 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength TABLE 1 Armed Forces Qualification Test: Categories and Score Ranges SOURCE: Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, “Understanding ASVAB Scores,” https://www.officialasvab.com/applicants/ scores/ (accessed August 9, 2022). Category Score Range I 93–99 II 65–92 IIIA 50–64 IIIB 31–49 IVA 21–30 IVB 16–20 IVC 10–15 V 1–9 A the services will not enlist applicants below Category IIIB without a waiver. The difficulty involved in finding sufficient numbers of AFQT Category I, II, and IIIA applicants has led the services to explore non-cognitive testing as an alternative way to assess American youth for their potential to succeed in military service. These non-cognitive tests, the most notable being the Tailored Adaptive Personality Assessment System (TAPAS), identify behavioral skills and attributes like grit, resilience, or coping that predict success in an endeavor. Nearly all of the military services have administered or are administering the TAPAS test to military applicants, and the Army was administering it on a limited basis as early as 2012. However, none of the military services has fully integrated the TAPAS scores into its enlistment-related decision-making. Service recruiting commands and advocacy groups have asked that applicants be allowed to use electronic calculators when taking ASVAB tests and that testing be provided in a language option other than English (for example, in Spanish). The thought is that the use of calculators and testing in a native language will increase the pool of qualified applicants. However, these proposals present multiple challenges. ASVAB testing questions have not been developed with calculators in mind, and the test has not been normed with applicants who used calculators. As a result, allowing calculators to be used in ASVAB testing would likely have only a marginal impact on the number of qualified applicants. In addition, military training is conducted The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 45 and mechanical ability. DOD used the AFQT to measure the “general trainability” of draftees and volunteers for all of the armed services. In 1966, the DOD began to develop a single battery for all of the services. In 1968, the DOD first offered the ASVAB at no cost to high schools and postsecondary schools. By 1976, DOD introduced the ASVAB as the official aptitude test for all of the services.38 Since that time, the DOD has improved the ASVAB program, most notably with the inclusion of the Career Exploration Program (CEP). Administered to over 500,000 high school students annually, the CEP is used by school counselors to encourage students to increase their level of self-knowledge and understand how that information is linked to military and civilian occupational opportunities. For recruiters and potential recruits, the ASVAB test’s most important score is the AFQT, which is computed using scores from four subtests: Arithmetic Reasoning, Mathematics Knowledge, Paragraph Comprehension, and Word Knowledge. The AFQT score is a percentile ranging from 1–99 and is normed based on a sample of 18-year-old through 23-year-old youth that was collected in 1997, resulting in a bell curve in which an AFQT score of 50 represents an average result. The AFQT scores are further broken into eight categories, as depicted in the accompanying table. The military services are required to report the number of military applicants enlisted under each category. The service recruiters are strongly encouraged to enlist AFQT Category I, II, and IIIA applicants and to limit AFQT IIIB applicants. Generally, heritage.org in English, so applicants who are not proficient in English would likely struggle with and possibly fail in training because of their inability to comprehend the training materials. The most viable way to increase the pool of qualified applicants would be to use a blend of cognitive and non-cognitive tests to determine suitability and enlistment. For example, ASVAB Category IV applicants who would otherwise not be considered for enlistment could be granted a waiver if they have a high TAPAS score. As all the services are currently administering the TAPAS test to prospective recruits, this blended approach could be implemented quickly and at a fraction of the cost of other options. The blended approach represents a step-increase in testing capability, increasing the enlistment eligibility (qualification) of the current and prospective pool of recruits while also improving the classification of recruits to improve success rates in military service. Propensity. While the DOD as a whole and the military services individually develop and implement policies to identify high-quality prospects for military service and increase the odds that such service will be successful, they also work to understand the attitude of youth toward military service. This is key to marketing efforts that link the military to American youth. One of the DOD’s greatest challenges is a significant decline in the propensity to serve among America’s youth and a corresponding negative trend in views of the value of military service among key “influencers” that shape their opinions. This decline has been influenced by a combination of factors such as: l l l l 46 A shrinking military footprint in many areas of the country (resulting in less opportunity for youth to have personal contact with anyone in the military); Low unemployment rates (plenty of job opportunities in the civilian sector); Improved access to college and higher education; and Years of prolonged overseas conflict for the military (implying that anyone joining the military would have a similar experience). These factors have created conditions in which the intrinsically motivating elements of military service have become less self-evident to the youth market while the sacrifices of service in terms of physical, psychological, and quality-of-life consequences remain top-of-mind. Today’s youth view military service as fraught with risk and sacrifice without unique rewards or advantages. The distinguishing outcomes that youth associate with joining the military often include physical injury, constant deployment, family separation, post-service unemployment, and trouble reintegrating into society. These views are often reinforced by the media, national headlines, and family influence. Moreover, the increased political polarization of America has crept into perceptions of military service. The military is portrayed negatively as either a breeding ground for racist, extremist, or insurgent behavior on the one hand or weakened by “woke,” fragile, and social experimentation policies on the other. Both portrayals, neither of which is either true or productive, undermine youth propensity to serve and therefore military recruiting. To counter these challenges and help reimage the military for today’s youth, the DOD initiated a series of influencer media campaigns. The messaging was intended to increase awareness of the opportunities of military service, advocate for the benefits of public service, and overcome the misinformation with respect to the risks associated with military service. The Joint Advertising, Market Research and Studies (JAMRS) program is the DOD office for military advertising, market research, and studies related to recruiting.39 JAMRS uses annual surveys to explore the perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes of American youth as they relate to joining the military. Understanding these factors is critical to success in sustaining an AVF and helps to ensure that recruiting efforts are directed in the most efficient and beneficial manner. JAMRS survey results show a steady decline in the general propensity to serve in the military among youth ages 16–21 between 2018 and 2021, reaching a low of 10 percent in the summer of 2021.40 At low levels of propensity, all resources supporting the recruiting mission must work harder for the services and DOD to make annual recruiting goals. For the first time, a majority of youth have never considered the military as an option, even though economic hardships and uncertainties persisted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength weekend engagement to achieve recruiting goals. Individual recruiter engagement with prospective applicants is therefore extremely important and must be measured across multiple metrics to ensure that the front end of the accession pipeline remains productive. Market indications are problematic for military recruiting in both the short and long terms. Many youth aspire to a lifestyle that maximizes work–life alignment, which they do not perceive as being available with military service. The military recruiting services have not adjusted their messaging to account for this change in youth attitudes. Doing so will come at increased cost, but it will also help to attract high-quality, eligible, and diverse youth. Experience has shown that support for AVF recruitment requires adequate and sustained resources. The services must have the resources to make timely investments in the number of recruiters, marketing and advertising efforts, and enlistment bonuses to mitigate the adverse effects of such a challenging environment. Modernizing Military Accessions The military accession process must evolve to achieve the quality standards and quantity requirements that are needed to maintain military readiness. Industrial age accession practices, based on large-scale batch processing, need to be replaced by data-driven and targeted strategies. The COVID-19 pandemic served as an inflection point for the accession enterprise, highlighting systemic issues in the accession model while prompting the development of potentially transformational programs to modernize the process. At present, the military services are failing to leverage new tools to achieve their recruiting goals at the very time when American youth are increasingly ineligible to serve and have less desire to serve. While challenging, the recruiting environment does present an opportunity to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic with a new accession model that is built on modern medical standards and technologies, integrated cognitive and non-cognitive testing, and the ability to adapt to changing youth attitudes and behaviors. The current incentive structure, which tends to favor quantity of recruits over quality of recruits, does not support this transition. History has shown that the accession enterprise can evolve when there is sufficient dissatisfaction with The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 47 Additionally, only 23 percent of America’s youth are eligible to enlist in the military without a waiver.41 Disqualifying factors include overweight, drug use, adverse medical conditions/history, adverse mental health condition/history, low aptitude and education, poor conduct, and having dependents (a spouse, child or children, or other family members who depend on the potential enlistee for support). Nearly half of all youth who are ineligible are so for multiple reasons. This situation is exacerbated by low youth propensity and the difficulties recruiters have in engaging youth in a fragmented social and cultural landscape with limited resources. Most youth do not seek information about serving in the military and are not motivated to look past the stereotypes presented in our culture. Emergent concerns around sexual harassment and assault in the military are at an all-time high: Nearly one-third of eligible youth cite this as the main reason why they would not consider joining the U.S. military. Significant growth in the number of media platforms, including traditional media, social media, and digital media, requires outreach resources to work harder and be targeted so that they reach intended markets more effectively. The disconnect between the youth population and the military has been exacerbated by current events, creating a perfect storm for military recruiters. The restrictions on in-person engagements imposed because of the COVID-19 pandemic have left recruiters at a disadvantage in cultivating and maintaining relationships with both the broader market and the low-propensity segments of that market. As many recruiters will relate, it is much easier for a potential applicant to “ghost” them, either by not responding to efforts to contact them or by ignoring follow-on efforts once an initial contact is made, if they have met only online. Additionally, many recruiters lack the social media skills and authorities to engage with potential applicants in the digital platforms where they are most likely to be found. Nonetheless, recruiting remains a very personal business. Unlike transactional sales, recruiting for military service is more akin to a serial sales model where a recruit must be sold multiple years of service. This requires face-to-face interactions not only with the prospective recruit, but also with his or her family, friends, and other influencers. For most successful recruiters, this is not a “9 to 5” job; it is one that requires significant evening and Conclusion The accession enterprise must build the resilience that is similarly expected of military servicemembers. Recruiting the AVF cannot be a reactive activity; it must be a proactive, initiative-driven effort that engages American youth and convinces them of the value and nobility of serving their country in uniform. Removing impediments is critical to making progress in this endeavor, and implementing a host of modern systems within the medical screening and recruit processing systems is a huge step forward. Similar efforts are needed in the recruiting system and should receive priority attention not just from senior defense officials, but also from influencers in education, civic organizations, and the sports and entertainment industries. These are the sectors of American society that are in the closest and most regular contact with our youth. If such efforts are not made, the viability of the AVF and, consequently, the security of the country will come into question. the current state, when there is a compelling vision for a future state, and when initial steps are taken toward that future state. The medical technologies, in terms of authoritative health information and electronic health records, and the cognitive and non-cognitive testing methodologies are in place to be fully integrated into the accession process. The only obstacles that remain are the policy and political will to do so and the institutional resistance to change. Failure to act at this moment will delay implementation for at least another generation and continue to jeopardize military readiness. Political agendas and public opinion will continue to play a role in the accession process, but their negative manifestations can be marginalized when all of the components needed to identify, engage, recruit, and induct new servicemembers are aligned on outcomes. Understanding the primary levers of control through medical and testing standards, as well as a deep understanding of changing youth attitudes and behaviors, will allow the accession enterprise to achieve its goals in any political, economic, or social environment. 48 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Endnotes 1. James Mattis, Secretary of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, U.S. Department of Defense, p. 1, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-DefenseStrategy-Summary.pdf (accessed August 8, 2022). 2. Alan M. Saks, “The Impracticality of Recruitment Research,” in The Blackwell Handbook of Personnel Selection, ed. Arne Evers, Neil Anderson, and Olga Voskuijl (Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), pp. 47–72). 3. Press release, “Department of Defense Announces Recruiting and Retention Numbers for Fiscal Year 2022 Thru February 2022,” n.d., https:// prhome.defense.gov/Portals/52/Documents/MRA_Docs/MPP/pressreleases/2022/5%20-%20Press%20Release%20February%202022%20FY22. pdf?ver=a9W-dWRNxTH06HwIvfFu4g%3D%3D (accessed August 8, 2022). 4. Steve Beynon, “Army Drops Requirement for High School Diploma amid Recruiting Crisis,” Military.com, June 24, 2022, https://www.military. com/daily-news/2022/06/24/army-drops-requirement-high-school-diploma-amid-recruiting-crisis.html (accessed August 8, 2022), and Joe Lacdan, “Army Eases Tattoo Restrictions with New Policy,” U.S. Army, June 23, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/257828/army_eases_tattoo_ restrictions_with_new_policy (accessed August 8, 2022). 5. Steve Beynon, “Army Extending Assignments for Recruiters Involuntarily as Service Scrambles to Fill Ranks,” Military.com, June 10, 2022, https:// www.military.com/daily-news/2022/06/10/army-involuntary-extending-assignments-recruiters-service-scrambles-fill-ranks.html (accessed August 8, 2022). 10 U.S. Code § 505(a), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/505 (accessed August 8, 2022). U.S. Department of Defense, “Qualification Standards for Enlistment, Appointment, and Induction,” Department of Defense Instruction No. 1304.26, March 23, 2015, Incorporating Change 3, October 26, 2018, p. 2, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/ dodi/130426p.pdf?ver=2018-10-26-085822-050 (accessed August 8, 2022). 8. Davis Winkie, “Army May Restructure Brigade Combat Teams amid Recruiting Woes,” Army Times, July 29, 2022, https://www.armytimes.com/ news/your-army/2022/07/29/army-may-restructure-brigade-combat-teams-amid-recruiting-woes/ (accessed August 8, 2022). 9. The standards were first published in Selective Service Regulations in 1917 and were later incorporated into Army Regulation 40-105, “Standards of Physical Examination for Entrance into the Regular Army, National Guard, and Organized Reserves,” which included the horse-friendly policy of barring those exceeding 180 pounds from joining the cavalry. See Selective Service Regulations, Part VIII, “Physical Examination,” 1917, pp. 94–101, https://centropr-archive.hunter.cuny.edu/sites/default/files/military-project/1917%20Draft.pdf (accessed August 8, 2022), and Army Regulation 40-105, “Standards of Physical Examination for Entrance into the Regular Army, National Guard, and Organized Reserves,” May 29, 1923, in Colonel William B. Foster, Ida Levin Hellman, Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Hesford, and Captain Darrell G. McPherson, Physical Standards in World War II, Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, 1967, pp. 244–248, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA291761.pdf (accessed August 8, 2022). 10. War Department Mobilization Regulation No. 1-9: “Standards of Physical Examination During Mobilization,” August 31, 1940, in Foster et al., Physical Standards in World War II, pp. 129–160. 11. The PULHES physical classification standard was adopted from a system already in use by the Canadian Armed Forces. The Canadians had a system called PULHEMS, which indicated the individual’s suitability for a particular assignment at a glance. (The “M” in the Canadian system stood for mentality (intelligence) and was eliminated from the U.S. system in favor of AGCT results, which were recorded separately in the individual’s record.) After experimenting with the Canadian system, the Americans adopted it as PULHES in May 1944. “In a complete profile, an individual received a grade from 1 to 4 in each of the six body parts or functions; that is, ‘P,’ physical capacity or stamina; ‘U’, upper extremities; ‘L’, lower extremities; ‘H’, hearing (including ear defects): ‘E’, eyes; and ‘S’, neuropsychiatric.” Each of the letter categories had four numerical grades that could be assigned. See “The Adoption of PULHES,” in Foster et al., Physical Standards in World War II, pp. 68–72, esp. p. 68. See also U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, “Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction,” DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1, March 30, 2018, pp. 16–17, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_v1p. PDF?ver=9NsVi30gsHBBsRhMLcyVVQ%3D%3D (accessed August 8, 2022), and U.S. Department of Defense, “Criteria and Procedure Requirements for Physical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Armed Forces,” Department of Defense Instruction No. 6130.4, April 2, 2004, p. 9, https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blaw/dodd/corres/pdf/i61304_040204/i61304p.pdf (accessed August 15, 2022). 12. Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, “History of Military Testing,” https://www.officialasvab.com/researchers/history-of-military-testing/ (accessed August 8, 2022). See also Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, “ASVAB Fact Sheet,” n.d., https://www.officialasvab.com/wpcontent/uploads/2020/07/ASVAB-Fact_Sheet.pdf (accessed August 8, 2022). 13. National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, Medical Follow-up Agency, Committee on Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Associated with Military Service from World War II to the Present, Noise and Military Service: Implications for Hearing Loss and Tinnitus, (Washington: National Academies Press, 2006), p. 190, https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11443/chapter/8 (accessed August 8, 2022). 14. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, “Update: Routine Screening for Antibodies to Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Civilian Applicants for U.S. Military Service and U.S. Armed Forces, Active and Reserve Components, January 2014–June 2019,” U.S. Department of Defense, Military Health System, last updated January 9, 2020, https://health.mil/News/Articles/2019/08/01/Routine-Screening-forAntibodies?type=Fact+Sheets#:~:text=Infection%20with%20HIV%20is%20medically,detect%20newly%20acquired%20HIV%20infections (accessed August 8, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 49 6. 7. 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2015, 2014, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/Downloads/icd10cm-guidelines-2015.pdf (accessed August 8, 2022). 16. Daniel Wilson, “DOD Issues Guidance for Recruiting Transgender Troops,” Law360, December 21, 2017, https://www.law360.com/employmentauthority/articles/997304/dod-issues-guidance-for-recruiting-transgender-troops (accessed August 8, 2022). Subscription required. See also U.S. Department of Defense, “In-Service Transition for Transgender Service Members,” DoD Instruction 1300.28, April 30, 2021, https://www.esd. whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/130028p.pdf (accessed August 9, 2022), and U.S. Department of Defense, “Coronavirus: Timeline: DOD Response,” last updated August 8, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/Spotlights/Coronavirus-DOD-Response/Timeline/ (accessed August 9, 2022). 17. Testimony of General Joseph M. Martin, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, in hearing, Fiscal Year 2023 Readiness Program Update, Subcommittee on Readiness, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives July 19, 2022, 1:03:20 to 1:03:52, https://armedservices.house.gov/ hearings?ID=6D218012-FDB2-47DE-8DCF-9EA14A5D821F (accessed August 8, 2022). 18. See note 11, supra. 19. U.S. Department of Defense, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Preventive Medicine Branch, Accession Medical Standards Analysis & Research Activity, Annual Report 2015: Attrition & Morbidity Data for 2014 Accessions, Published and Distributed 2nd Quarter of Fiscal Year 2016, p. 3, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1005616.pdf (accessed August 15, 2022). U.S. Government Accountability Office, Military Personnel: Improvements Needed in the Management of Enlistees’ Medical Early Separation and Enlistment Information. GAO-17-527, July 2017, pp. 20 and 21, https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/686352.pdf (accessed August 15, 2022); and “FY18 EPTS Attrition Data (October 2017–September 2018),” in Colonel Arthur B. Cajigal, “Brief to British Armed Forces Recruiting Programme,” U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command, February 3, 2020, p. 15. 20. U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command, “Your Future Begins Now!” https://www.mepcom.army.mil/ArchivedPages/Enlistment-Processing/ (accessed August 8, 2022). 21. U.S. Department of Defense, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Preventive Medicine Branch, Accession Medical Standards Analysis & Research Activity, Annual Report 2015: Attrition & Morbidity Data for 2014 Accessions, p. 3. 22. Mark E. Gebicke, Director, Military Operations and Capabilities Issues, National Security and International Affairs Division, U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Military Attrition: Better Screening of Enlisted Personnel Could Save DOD Millions of Dollars,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Personnel, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, GAO/T-NSIAD-97-102, March 5, 1997, https://www.gao.gov/assets/tnsiad-97-102.pdf (accessed August 9, 2022). 23. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Military Personnel: Improvements Needed in the Management of Enlistees’ Medical Early Separation and Enlistment Information, pp. 20–25. See also U.S. Department of Defense, Walter Reed Institute of Research, Preventive Medicine Branch, Accession Medical Standards Analysis and Research Activity, Annual Report 2015: Attrition & Morbidity Data for 2014 Accessions, pp. 101–113. 24. Tandem, “U.S. Department of Defense: Modernizing the Military Enlistment Process,” https://madeintandem.com/case-studies/modernizing-themilitary-enlistment-process/ (accessed August 9, 2022). 25. Fact Sheet, “HAIMS: Health Artifact and Image Management Solution,” U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Health Agency, Solution Delivery Division, October 2021, https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Fact-Sheets?query=haims&isDateRange=0&broadVector=000&newsVector=00000 000&refVector=0000100000000000&refSrc=1 (accessed August 9, 2022). 26. Fact Sheet, “DoD Healthcare Management System Modernization Joint Longitudinal Viewer,” U.S. Department of Defense, DoD Healthcare Management System Modernization, Program Management Office, October 2019, https://health.mil/-/media/Files/MHS/Fact-Sheet-Files/ JLV_Factsheet_20191022_508C.ashx (accessed August 9, 2022). 27. U.S. Department of Defense, Military Health System, “Military Health System Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Procedures,” last updated December 10, 2021, https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/Pharmacy-Operations/PrescriptionMonitoring-Program/Prescription-Drug-Monitoring-Program-Procedures (accessed August 9, 2022). 28. Claudia Sanchez-Bustamante, “New Electronic Health Record Rollout Will Hit Major Milestone in 2022,” U.S. Department of Defense, Military Health System, January 12, 2022, https://health.mil/News/Articles/2022/01/12/New-Electronic-Health-Records-Rollout-Will-Hit-Major-Milestonein-2022 (accessed August 9, 2022). 29. U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command, FY2021 Annual Report, p. 3, https://www.mepcom. army.mil/Portals/112/Documents/Command%20Annual%20Report/Command%20Annual%20Report%20online%20FY2021. pdf?ver=UGoLTRx6024TEVZosMWD8w%3D%3D#:~:text=Medical%20Review%20of%20Authoritative%20Data,streamline%20the%20 medical%20qualification%20process (accessed August 8, 2022). 30. Slide 6, “MROAD Pilot Results, April–June 2020,” in Stephanie P. Miller and Colonel Rich Brady, “OUSD(P&R) Military Personnel Policy: Accession Policy Directorate,” U.S. Department of Defense, presented July 2021, p. 6, and Slide 11, “PMRS/JLV Impact on Attrition,” in “Accession Medical Modernization,” U.S. Department of Defense, presented January 2021. 31. U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command, FY2021 Annual Report, 2021, p. 3. 32. Private correspondence with the author. 50 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 33. U.S. Department of Defense, Military Health System, “About MHS GENESIS,” https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/MHS-Transformation/ MHS-GENESIS#:~:text=About%20MHS%20GENESIS,%2C%20veterans%2C%20and%20their%20families (accessed August 10, 2022). 34. Kendra Cherry, “Robert Yerkes Was Influential in Comparative Psychology,” Verywell Mind, updated April 13, 2020, https://www.verywellmind. com/robert-yerkes-biography-2795531 (accessed August 8, 2022). 35. Joe Ricker, “Army Alpha & Army Beta & Psychology: History, Theories, & Results,” Study.com, updated January 7, 2022, https://study.com/ academy/lesson/army-alpha-army-beta-psychology-history-theories-results.html (accessed August 8, 2022). 36. Andrew Marshall, “What Is the Army General Classification Test?” Boot Camp & Military Fitness Institute, January 15, 2021, https:// bootcampmilitaryfitnessinstitute.com/2021/01/15/what-is-the-army-general-classification-test/ (accessed August 8, 2022). 37. Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, “Historical Importance of Military Testing,” https://asvabmilitarytest.com/history-of-asvab-test (accessed August 9, 2022). 38. Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, “History of Military Testing.” 39. U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Advertising, Market Research & Studies, “Marketing Communications,” https://jamrs.defense.gov/marketingcommunications/ (accessed August 8, 2022). 40. U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Advertising, Market Research & Studies, Office of People Analytics, “Summer 2021 Propensity Update,” PowerPoint Presentation, May 18, 2022, p. 2, https://jamrs.defense.gov/Portals/20/Documents/ YP50Summer2021PUBLICRELEASEPropensityUpdate.pdf?ver=gSF5SrE3hRX5lhFwoz7Iqw%3d%3d (accessed August 8, 2022). 41. Matt Seyler, “Military Struggling to Find New Troops as Fewer Young Americans Willing or Able to Serve,” ABC7 Eyewitness News, New York, July 2, 2022, https://abc7ny.com/military-troops-recruitment-war/12011656/#:~:text=Only%2023%25%20of%20Americans%20aged,use%20are%20 common%20disqualifying%20factors (accessed August 8, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 51 Determining the Real Cost of the Tools of War John G. Ferrari, Major General, U.S. Army (Ret.) A With regard to defense costs, there are four key problems with respect to both weapons systems and personnel: l The failure to include operating and support costs, l Undefined timelines, l Poor or nonexistent updating of estimates, and l Abuse of the English language. popular low-cost airline advertises one-way flights from New York City to Los Angeles starting at $61, an undeniable bargain. When you go to book the flight, you realize it is a 13-hour trip, compared to the six-hour nonstop advertised by competitors. Then you notice the five-and-a-halfhour layover in Miami, in a direction the opposite of where you are traveling. When you continue with your booking, it becomes clear that to choose your seat, bring any sort of personal item on the plane, and check a bag, you will have to spend another $65—four bucks more than the cost of the flight itself. A carry-on and onetime waived change fee will cost you an additional $15. Finally, for the right to check in with an agent at the airport, you will be squeezed for an extra $10. On the payment page, your $61 flight will have become nearly triple what you would have paid to be afforded the same amenities provided on most other flights (with the exception of complimentary in-flight beverages and snacks), and you have become the beneficiary of an unexpected five-and-a-half-hour pit stop in a Florida airport. The Department of Defense (DOD) weapons systems and personnel cost estimates and the unnamed low-cost airline have many commonalities including misleading up-front and fixed costs, misunderstood timelines, and operational costs that are often ignored. Why make the comparison? The American public is consuming information from various sources that often mix up, confuse, and make erroneous cost projections for various DOD programs. Just as they need to be better consumers of airline flight information, American taxpayers need to be more well-informed about defense capabilities and better consumers of defense information and security. It is clear that some of the most prominent programs and personnel costs in the U.S. military today suffer from inconsistent and incomplete estimations, with one prominent exception: the much-maligned F-35 fighter. As complicated as the estimation process and DOD estimation guidelines are, once he or she knows where to look, anyone can determine where programs fall victim to some of the more common estimation pitfalls. Although submitting incorrect estimations could eventually lead to bad policy decisions, it is safe to assume that few to none of these inaccuracies are the result of malicious intent. Some estimations, such as those for the F-35 program and the cost of the Iraq War, have serious political implications that may incentivize the cherry-picking of numbers, but consistent problems in DOD estimations result from a number of systemic and procedural issues. This analysis is not meant to forgive misguided budgeting but seeks rather to explain that even the “facts” may not be accurate in the end, whether miscalculations are caused by inclusion or by omission of data. As the U.S. seeks to strengthen the military’s budget, it is critical that policymakers have the right information The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 53 at the right time so that they can make the best de- complicate the analyses of and justifications for cisions and Americans can get the most national billions of dollars in national security decisions. defense for their tax dollars. One should never be afraid to ask what is meant by a word: Words matter. Using and Understanding the PAUC vs. APUC. Anyone who wants to know Right Defense Budget Terms how much specific weapons systems or munitions How much money does Congress provide for our cost should be prepared to be dazzled by two differnational defense? This is a seemingly easy ques- ent combinations—PAUC and APUC—and be pretion, yet most get it wrong, and they do so mostly pared for both to be used interchangeably or, worse because there are three different sets of numbers yet, not identified. that get transposed in normal conversation. What PAUC stands for Program Acquisition Unit Cost, the United States spends on national defense is not which is set in statute and used to define cost rethe same as what the Pentagon spends, which is not porting requirements to Congress.2 It is simply calthe same as how much money is appropriated by the culated by adding together all of the developmental Defense Appropriations Subcommittees of Congress. costs for a program, including program-specific Understanding the difference between, for example, military construction; adding it to the projected “basic economy” and merely “economy” is key to un- cost of production; and then dividing that sum by derstanding what our money is buying. the total number of systems intended to be proTo start with, the term “national defense”—in the cured throughout the system’s lifetime. If you want case of resourcing—encompasses much more than to make a system appear affordable, be extremely the Pentagon and includes programs run by other optimistic in how many you plan to acquire: The departments such as the nuclear program in the more you “intend” to buy, the more you spread the Department of Energy. This number is often called development costs, thus driving down the appearthe “050” budget line number and aligns with the ance of the per unit price. In this case, imagine you National Defense Authorization Act. For the Penta- are the airline, trying to raise money from investors. gon specifically, its funding is often called “051.” But If you assume lots of people on your aircraft for each just to make it slightly more confusing, in the con- flight, you can market yourself as a low-cost airline. gressional appropriation process, the defense appro- However, if the passengers do not show up, you are priation does not include either the Pentagon funds now a high-cost airline. for Military Construction/Family Housing, which Within DOD, analyzing the PAUC is important are provided by the Appropriations Committee’s for programs with large up-front development costs Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Relat- and high projected quantities. As a smart consumer ed Agencies Subcommittee, or the non-Pentagon of DOD acquisition data, never take the PAUC at face National Defense funds, which are provided by the value without understanding those two factors. Energy and Water Development and Related AgenThe second acronym is APUC: same letters, but cies Subcommittee. this time they stand for Average Per Unit Cost. The Table 2 is a helpful guide to understanding these APUC is calculated by taking the actual projected numerical discrepancies and explains why the fol- cost of production and dividing it by the proposed lowing sentence incorrectly compares budget re- quantity. Since inflating the quantity does not get sources: “A budget of even $770 billion [051] would you a lower average in this case, how does this numbe a significant increase when compared to the ber get misused? It is called the “learning curve.” $728.5 billion enacted in law for the Defense Depart- The learning curve occurs when a program assumes ment in FY22 [defense appropriation less military that the cost of production will magically decrease construction].”1 over time. Since there is both an art and a science to This is just one example (albeit a simple one) of forecasting the learning curve effect in forecasted how the word “defense” has three different mean- pricing, this is an area in which you should be exings depending upon who is using it and when. Now tremely skeptical when comparing different systems. imagine this playing out across different programs To see it in practice, consider the recent budget or in the context of real versus nominal dollars. documents for the F-35 and F-15EX. In 2023, the Not being specific with defense budget terms can F-35 jets are Block 4 models, and the fly-away cost 54 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength TABLE 2 Funding Provided to the Department of Defense 2021 Enacted 2022 President’s Budget 2022 Omnibus DOD, Defense Appropriations $695.2 $705.2 $728.5 4.8% DOD, MILCON Appropriations $8.5 $9.8 $14.9 75.3% $703.7 $715.0 $743.4 5.6% $37.1 $37.9 $38.6 4.0% $740.8 $752.9 $782.0 5.6% Total DOD (051) Non-DOD National Defense (DOE/Other) National Defense Budget (050) Change, 2021 Enacted to 2022 Omnibus SOURCE: Elaine McCuster and John G. Ferrari, “4 Initial Defense Highlights from the 2022 Omnibus Appropriations Bill,” American Enterprise Institute, AEIdeas Blog, March 11, 2022, https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/4-initial-defense-highlights-fromthe-2022-omnibus- appropriations-bill/ (accessed August 11, 2022). A heritage.org and funding lines; therefore, it does not go through the same bureaucratic process that other agencies must go through inside the Pentagon. Before the Federal Aviation Administration cracked down on the airlines, some of them excluded such things as the Passenger Facility Charge, Flight Segment Tax, September 11 Security Fee (Passenger Civil Aviation Security Service Fee), and Transportation Tax from their advertised fares. Unfortunately, we have no version of the FAA for program costing; therefore, as with a resort fee at a hotel, you need to ask about other costs. At its core, the MDA is only supposed to procure systems, and after it is done fielding them, the intent is for the systems and all associated costs to be transferred to one of the military services. Therefore, MDA estimates tend to be limited to just the MDA’s costs—not lifetime costs. A February 2022 Missile Defense Agency: How Government Accountability Office (GAO) report Excluding Costs “Looks” Cheaper highlights this reality, noting that the U.S. Missile A common fallacy holds that projected cost esti- Defense Agency’s cost estimates included “a nummates are guided by and adhere to a common set of ber of shortcomings…such as its comprehensiveness, rules and standards and that they cannot be skewed accuracy, transparency, and traceability.”3 by the agency providing them. The Missile Defense With regard to cost omissions, one needs to be Agency (MDA) has its own acquisition authority aware that the MDA is omitting certain operational The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 55 (APUC) is about $91.6 million each or $5 million more than the Block 3 jets, which is straightforward. If the Air Force bought 48 jets, the gross weapons system cost (PAUC) of each fighter would have been $108 million. By reducing the number of F-35s purchased/denominator to just 33 F-35As, the gross weapons systems cost (PAUC) increases by almost $8 million to $115.5 million. Why would the Air Force do this? Because they want to buy more F-15EXs. Reducing F-35 quantities makes the $120.2 million PAUC for the F-15EX seem almost even. In other words, $120.2 million per plane seems a lot more justifiable to Congress when the other option is nearly the same price anyway. Buying only 33 enables the Air Force to level the cost comparisons. All of the math is accurate, but knowing how the costs are calculated is just as important. and sustainment costs from its estimates. Why is this important? Because operations and sustainment costs can often reach 70 percent of lifetime-program costs, which means that omitting or adjusting these estimates has an enormous impact not just on current funding levels, but also on future funding levels. This has hampered the MDA because, in reality, the agency has not transferred many programs to the services. Therefore, over time, the MDA finds itself spending more funds on sustainment, which is not in its mission statement, and less on research and development and procurement, which are why it exists. This error, in effect, mortgages our future to pay for the present. The GAO also notes that the MDA is inaccurately reporting flight test cost estimates. Two recent Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) tests cost a combined $20 million, but the flight test estimate was only $2 million.4 This discrepancy is not isolated to the Army’s THAAD system. The GAO also “found a $1.5 billion increase in development costs for the Aegis Weapon System Spiral 5.1 program between 2019 and 2020 baseline reporting,” while “MDA only reported a $664 million increase—a difference of $851 million.”5 Why is this important? Because those costs are inaccurately represented elsewhere in the budget, which means that policymakers are using bad information when assessing the cost-benefit of one system versus another. Is the MDA doing anything malicious? Not necessarily. For the most part, it is doing estimates only for those costs that apply directly to its mission set rather than after it transfers the program to the services. The MDA will also state that, regarding test costs, assessing fixed costs across programs may not be worth the effort. In any event, an observer’s understanding of the costs for various MDA systems would be just over one-third of the actual cost: $1.3 billion reported by the MDA versus “at least $3.5 billion” uncovered by the GAO.6 However, just because it is not malicious doesn’t mean it is not a problem. Anticipating ongoing systems costs certainly needs to be included in program estimates to help the decision-makers prepare for future years’ defense spending. costs in the procurement of the first ship for a specific class. Even taking that into account, it appears that the Navy then engages in a bit of wishful thinking on how costs can be reduced for the new class of ships, relying on intuition rather than on past data. This is analogous to someone who checks the price of an airplane ticket six weeks out and then uses that estimate to set aside funds for a ticket he intends to purchase the night before he flies. In 2020, the Navy estimated that the Constellation-class frigate would cost about $870 million per ship, or $8.7 billion for the 10-ship project;7 Eric Labs, one of the top Congressional Budget Office (CBO) naval analysts, separately predicted that the program would cost $1.2 billion per ship, or $12.3 billion for the entire program.8 Historically, the Navy has “almost always” underestimated the cost of its shipbuilding projects.9 The Navy was able to weave together a wishful narrative that, according to the Congressional Research Service, could be true because the “FFG(X) is based on a[n Italian] design that has been in production [in Italy and France] for many years” and “[l]ittle if any new technology is being developed for it.”10 So what actually happened? From fiscal year (FY) 2021 to FY 2022, the Navy’s estimate of the cost per ship increased by 14 percent. Specifically: In the Navy’s FY2021 budget submission, the FFG-62 class ship to be procured in FY2022 (i.e., the third ship in the program) had an estimated procurement cost of $954.5 million. In the Navy’s FY2022 budget submission, the ship has an estimated procurement cost of $1,087.9 million—an increase of $133.4 million, or 14.0%, over the figure in the Navy’s FY2021 budget submission.11 This increase came about as a result of preparation and testing costs that were not previously included in the estimates. Looking forward, “if FFG-62s were to wind up costing about the same to construct per thousand tons of displacement as other recent U.S. military surface combatants, then the third and subsequent FFG-62s could cost 17% to Constellation-Class Frigate: The 56% more than the estimate for those ships shown Guide to Wishful Thinking in the Navy’s FY2021 budget submission.”12 Much like the MDA, the Navy has its own unique The military services are not immune to wishful way of calculating costs. The Navy places all of its de- thinking, and they also know that getting the provertailed design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) bial camel’s nose under the tent is a certain way to 56 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength CHART 1 Pound for Pound: Comparing the Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate Every surface combatant built since 1970 cost more by weight to produce than the Navy expects its new FFG(X) to cost. Figures shown below are costs per thousand tons of displacement in millions of 2020 dollars. SHIP YEAR AVERAGE COST OF LEAD AND FOLLOW-ON SHIPS DD-963 Spruance 1970 $210 FFG-7 Oliver Hazard Perry 1973 $249 CG-47 Ticonderoga 1978 $399 DDG-51 Flight I Arleigh Burke 1985 $293 DDG-51 Flight IIA Arleigh Burke 1994 $268 NSC-1 Legend 2004 $180 LCS-3 Fort Worth 2009 $215 LCS-4 Coronado 2009 $260 DDG-51 Flight III Arleigh Burke 2017 $227 FFG(X) 2020 $145 SOURCE: Figure 1, “Cost of the Navy’s Surface Combatants per Thousand Tons of Lightship Displacement,” in Congressional Budget Ofce, “The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate,” October 2020, p. 6, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-10/56669-New-Frigate-Program.pdf (accessed August 11, 2022). A heritage.org keep a program. Very few people get promoted for saying that they will run acquisition programs that cost more than previous programs; therefore, the inherent bias to “try for” savings is not malicious in intent but is instead rational inside a large bureaucracy. But that is not to say this rationale doesn’t desperately need a cleanup. was closer to $71 million—a 42 percent miscalculation. While the difference between $50 million and $71 million might seem relatively small, if you account for a 42 percent mistake over a long period of time for a large fleet of ships, the cost increase gets very large, very fast. How did the Navy get this so wrong? It turns out that outsourcing maintenance to contractors Littoral Combat Ships: Forgetting drove up the cost.14 The initial estimate of 40 crew People and the Price of Having Them members nearly doubled in reality to about 70, and The Navy is already decommissioning its initial before the Navy decided to terminate the program, purchase of the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) fleet just the number of sailors needed was about to grow even 14 years after the first ship set sail and, amazingly more. Cost projections based on bad assumptions or enough, even as a ship is finishing construction. What preferred assumptions that turn out to be wrong inwent wrong? A lot. For the purpose of this analysis, troduce flawed data for programs; the result is policy however, we will confine ourselves to the cost pro- decisions and budget commitments that prove to be jections for operating costs, which turned out to be terribly costly for the service and the taxpayer. outdated and inaccurate according to the GAO.13 The initial plan called for the ship to have about Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle: 40 people with maintenance done by contractors. Failing to Account for Uncertainty The Navy estimated total operating costs per year One of the Army’s signature modernization proper ship at $50 million. In reality, the cost over time grams is the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 57 (OMFV). Being optionally manned means that it could operate autonomously, a task that has never been accomplished and for which there are almost no past cost data. To fund this program in the near term, the Army is slowing down procurement of its existing systems, in essence trading current combat power for future combat power. However, will the Army be able to afford the new program, or is it doing as it did with the Future Combat Systems and other past efforts to build ground combat systems: setting itself up for having neither current nor future ground combat capabilities while spending tens of billions of dollars? If one is to believe the GAO, the Army is substituting the precision of point estimates to mask uncertainty, which in the past has led to failure “due to immature technology and changing and complex requirements at a cost to taxpayers of roughly $23 billion.”15 In effect, reality displaces optimistic projections over time, revealing the true cost of systems that are consistently higher than originally presumed. In the case of the OMFV, the consumer of the Army’s cost estimates needs to grapple with two important pieces of uncertainty. First, as discussed above, the Army has tried this before and failed to the tune of $23 billion. One has to ask: Why is this time different? The second question is: If this has never been done before, as we have never built an optionally manned combat platform, how can the cost estimate even be accurate? Given these complicating factors, it might have made more sense for the Army to structure this program as a series of smaller-duration, less risky demonstration projects that can prove out the cost, technology, and feasibility of the system. The GAO did give the Army high marks for following the cost estimation process, but at $46 billion (the projected cost of the program), the uncertainty error is enormous.16 As we saw with the Navy LCS, there really may be no way to know what the actual cost will be. The equivalent of this, for our airline ticket purchaser, is that you are going to buy an airline ticket for a flight 10 years from now and agree to pay based on the purchase price of aircraft that have yet to be purchased, the future unknown price of jet fuel, and the potential costs of developing the flight to have either a real pilot or no pilot at all. At this point, it is an open-ended commitment to spend money. Maybe this is less like buying a plane ticket than it is like buying a ticket to Mars. 58 Reserve Forces: The Cost of Active vs. Activating In the past decade, both the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Army have had financial disputes with their National Guard forces that have led to congressionally chartered commissions, both of which were triggered during periods of declining budgets and potential force structure reductions.17 The cost discussions are often difficult to understand, with both sides making “accurate” statements that lead to “different” conclusions. How can this be? It depends on how you blend personnel costs, equipment costs, and operating costs along with assumptions on Reserve use during peacetime for operational rotation missions versus wartime surge capacity. These five different variables can be, and often are, blended differently and then compared together as if they were the same. The first and most frequently used costs are those for personnel. Since Reserve personnel are part-time personnel, it is a mathematical fact that those that are not activated are less expensive than full-time personnel. However, depending on how often and for what purpose the services activate their Reserve Component forces, they could cost more than the equivalent of an Active unit. This is due to the time—and therefore the resources—needed for mobilization and post-mobilization efforts. If used for the occasional surge operation, the costs of the Reserve over time tend to be less than those of their Active counterparts. But if used nearly continuously for operational missions (continuous boots on the ground), the costs tend to be higher. Equipment costs, though often not discussed in relation to Reserve components, are relevant depending upon whether one treats equipment as a sunk cost because the equipment already exists or as a procurement cost that should be included in the Reserve’s total value/expense. The National Commission on the Future of the Army began over a dispute about the Apache helicopter’s force structure. Because the Army did not have enough Apaches and needed more funds to buy more aircraft, the price became a central component of the conversation. When related to low-density, high-cost weapons platforms like the Apache, costs become more relevant because they can dwarf other investments like personnel or operations. To compare, the cost of 100 cargo trucks might be nearly negligible within the Army’s total budget for accounting purposes, but the 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength cost of additional Apache helicopters at $13 million apiece mounts up significantly and quickly. (The less expensive trucks, however, also can add up to significant dollars if the quantity is high enough.) In other words, it matters what type of Reserve unit one is discussing, because the equipment within one type of unit can account for much more in dollar terms than the equipment in others does. Emerging from all of these studies over many years are two fundamental premises when discussing the Active Component/Reserve Component force mix: l “Part-time” force structure, meaning the capability delivered by traditional Reservists and Guardsmen who do not serve continuously on active duty, costs less than the force structure provided by “full-time” personnel. As of March 2021, the Department of Defense estimated that emergency/overseas contingency operations (OCO) spending for the wars in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan totaled $1.596 trillion;19 as of June 2022, it estimated that the total had reached $1.637 trillion.20 The cost of a war is perhaps the most challenging of all cost estimates. There are, off the bat, many necessary clarifying questions such as: l In what time span do you quantify the war? l When do residual costs end? l l l Reserve Component force structure, especially traditional Reservists, costs less than that of the Active Component, but Reserve Component forces are not always less expensive when conducting operations than are Active Component forces. l l l The Cost of War: Who’s Asking? According to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction’s most recent report: DOD’s latest Cost of War Report, dated September 30, 2021, said its cumulative obligations for Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel in Afghanistan, including U.S. warfighting and DOD reconstruction programs, had reached $849.7 billion…. State, USAID, and other civilian agencies report cumulative obligations of $50.1 billion for Afghanistan reconstruction, which when added to the DOD amount results in $136.9 billion obligated for Afghanistan reconstruction through that date….18 l Does it include personnel costs, which have to be accounted for regardless of whether the servicemember is at home or abroad? Are you measuring what was spent that otherwise would have not been spent, or also the cost of assets and resources that would still have been costly without the war? For example, a plane is flown in peacetime if only for pilots to maintain their skills and certification. Is one to account for direct economic costs? What about costs associated with deaths, the climate, etc.? Do you know how you measure those? Do you count associated medical care for veterans of those wars? Any estimate that professes to have determined the actual cost of war involves many subjective decisions about what to count and what not to count. Estimating the cost of the Iraq War is a chief example of this dilemma. The Brown University Costs of War Project has estimated that from FY 2001–FY 2022, the wars in Iraq and Syria cost a total of $2.058 trillion (exclusive of future veterans’ care). If one includes future veterans’ care, total costs rise to $3.158 trillion.21 A much less aggressive and comprehensive estimate by the Congressional Research Service puts The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 59 If you are trying to figure out how much it costs to travel from New York to Los Angeles, it matters whether you are flying on a private jet or a commercial jet, taking the train, or getting on a bus. For the discussion of Active versus Reserve Component costing, it matters whether you are including equipment costs, operational use, and wartime surge, broken out by various types of units. l Do you count related but indirect war costs? For example, do you count related activities in Syria as part of the Iraq war’s costs? obligations for Iraq at 51 percent ($759 billion) of total DOD OCO obligations from 9/11 through FY 2018.22 This would be the simplest number because it includes the fewest factors in estimated war costs. This is very similar to trying to calculate externalities into the cost of a flight to differentiate it from the price you are actually paying. For example: l l l l l l What is the price of the carbon emissions from the flight? What about the cost of the taxpayer-subsidized airport? If the airline goes bankrupt, what pension costs will the government have to pay for in the future? What about the food stamp costs for the people cleaning the airplane because they do not make a living wage? Have we calculated the environmental damage caused by production of the jet fuel? While we are at it, how about the human cost of extracting the titanium needed in war-torn countries to build the aircraft? All of a sudden, the “cost” of your flight diverges wildly from the “price” you pay for the ticket. Such is the case with the cost of war. It encompasses not only weapons systems and personnel costs, but also the accounting difficulties within both. The question of what to count and what is being accounted for leads to incredible variance between cost estimates—whether based on projected interest or whether or not to include veterans’ care. The key here is transparency: By knowing how it is totaled, one can better assess the components of that total, whether and how it compares to others, and what capabilities the funds physically provide. F-35: Most Expensive or Most Impressive? The F-35 aircraft is one of the most advanced and ambitious programs that DOD has undertaken. It also is heralded as the most expensive program ever undertaken. As this is the last of the cases we will examine, it is interesting to see how the F-35 compares to some of the other programs discussed in this essay. 60 First, the cost is estimated over a 66-year life cycle, with a current estimate in excess of $1.7 trillion.23 (By contrast, the MDA did not estimate operational costs over the lifetime of the missiles and supporting systems it purchased.) Of the $1.7 trillion, the procurement of 2,456 aircraft accounts for just under $400 billion, while the cost of sustaining the planes over time hits nearly $1.3 trillion. This is very important, as no other DOD program has a 66-year operating cost estimate. Second, this program has updated its cost estimates more times than almost all other programs combined. Over the course of the program, the GAO alone has issued an extensive series of reports examining the F-35’s ongoing cost estimates and the “significant challenges DOD faced in sustaining a growing F-35 fleet.”24 In April 2021, for example, the GAO reported that the Air Force needs to reduce estimated sustainment costs per plane by $3.7 million by 2036 or face $4.4 billion in costs beyond estimates.25 Each time the GAO issues a report, the cost estimates are updated. For most programs, the cost estimates are traditionally frozen in time, so this is likely the first living cost estimate in DOD’s history. Many worry that the armed services will be unable to afford the F-35’s sustainment. This should certainly be worrisome, as this critical project faces a grim future. But in relation to the thesis of this analysis, the forewarning and guidance on reducing future expenses make this program’s cost accounting also very impressive. As a result of expansive reporting from DOD and other U.S. government agencies on current costs and program updates and estimates, the F-35 program is likely the most well-accounted major weapons program in DOD history. One cannot help but wonder what the cost would be for every other major acquisition program across DOD if the same criteria and program updates that have been applied to the F-35 program were applied to them. Finally, in comparing F-35 procurement costs with procurement costs for other aircraft, it is obvious that other systems do not have the same in-depth cost accounting. This makes an apples-to-apples comparison impossible for anyone but the most determined budget analyst. In a recent and relevantly titled article, “Air Force’s Math on the F-15EX and F-35 Doesn’t Add Up,”26 a comparison of the two fighter platforms reveals the impressive nature of F-35 program 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength not on their search engine, while others use techniques like fare ghosting or providing discounted rates to other sites. In essence, caveat emptor—let the buyer beware. The same is true when you read a paper, news story, or official document about how much anything in DOD costs: Know that what you read is likely not everything you should know. First, there is no consistent standard for the updating of lifetime budget costs, which is especially problematic when actual inflation rates vary heavily from those anticipated numbers. In these cases, the estimates become obsolete. Lifetime budgets are sometimes not updated when estimates for the procurement of individual units unexpectedly increase, as in the case of the FFG-62. Next, the updated standards for budget estimation are not high enough, and there is no consumer protection board to hear complaints or to assess penalties for bad information. Even though services consistently underestimate initial and lifetime costs of personnel and weapons systems, there is no system for ensuring adjustments before the release of official estimates, which are almost always incomplete. Think of this as “in-flight meals not included” the next time you book your trip. The remedy for this is firmer definitions regarding budget estimations, something akin to the MSRP sticker on a new car—which in reality is often much more than the price you end up paying the dealer. Perhaps most important, the consumers of this information should channel their inner “Sy Syms.” Sy ran a series of discount clothing stores in the Conclusion Northeast, and his slogan was “An educated consumWhen you purchase an airline ticket these days, er is our best customer.” From reporters to analysts sites like Google Flights attempt to standardize the to the American public, asking the right questions, pricing by allowing you to adjust the ticket price for understanding partial answers—and when the anexpenses like carry-on baggage and picking your swers are only partial—and then acting on the inforseats while also measuring your carbon footprint. mation will ensure that as a nation, we make better But even that tool is not necessarily sufficient be- decisions and smarter investments regarding our cause some airlines, such as Southwest, are simply national security. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 61 cost counting. The Administration cuts the F-35 procurement quantities for FY 2023 because the F-15s are “less expensive to buy and to fly” than the F-35. The Air Force’s cost data for these two weapons systems prove this to be “patently false.” The F-35’s “flyaway” cost includes all of the equipment needed to meet mission requirements. The “cheaper” F-15 estimate provided by DOD fails to include offensive systems that are included in the F-35’s “sticker” price to meet the same requirements. And while the F-35 program might be a record due to its inclusion of all elements, for FY 2022, the gross weapons systems cost—including all necessary packages, equipment, and support depots—brings the F-15EX to $120 million27 compared to the fully loaded F-35A’s $98.2 million. Because of the F-35’s comprehensive cost estimates, the program has been able to see where changes need to be made. The fighter’s mission-capable rate has continued to rise in recent years, and DOD has reduced sustainment and readiness expenditures and timelines. Reform efforts include increasing the availability and production of spare parts, improving depot-level repair, and decreasing customer wait times. Increased transparency may increase the apparent cost, but in the long term, it results in better decisions and informed savings. The same cannot be said with any certainty for other aircraft procurement programs because no other such program has been similarly assessed. Endnotes 1. Valerie Insinna, “2023 Budget Drops on March 28, but Details Will Be Missing,” Breaking Defense, March 18, 2022, https://breakingdefense. com/2022/03/2023-budget-drops-on-march-28-but-details-will-be-missing/ (accessed July 12, 2022). 2. 10 U.S. Code § 4351(a)(1), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/4351#a_1 (accessed July 24, 2022). 3. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Missile Defense: Addressing Cost Estimating and Reporting Shortfalls Could Improve Insight into Full Costs of Programs and Flight Tests, GAO-22-104344, February 2022, p. 1, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104344.pdf (accessed July 24, 2022). 4. Ibid., p. 23. 5. Ibid., p. 28. 6. Ibid., p. 34. 7. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Constellation (FFG-62) Class Frigate Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. R44972, updated March 31, 2022, p. 15, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/ R44972/92 (accessed August 2, 2022). 8. David B. Larter, “US Navy’s Cost Estimate for New Frigate Won’t Hold Water, Predicts Government Analyst,” Defense News, October 14, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2020/10/14/the-us-navys-cost-estimate-for-its-new-frigate-wont-hold-water-analyst-predicts/ (accessed July 24, 2022). 9. Ibid. 10. O’Rourke, “Navy Constellation (FFG-62) Class Frigate Program: Background and Issues for Congress,“ p. 15. 11. Ibid., p. 13. 12. Ibid. 13. Anthony Capaccio, “Troubled Littoral Ship Still Can’t Perform Mission, GAO Says,” Bloomberg, February 24, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/ news/articles/2022-02-24/troubled-littoral-ship-still-can-t-perform-its-mission-gao-says (accessed June 13, 2022). 14. David B. Larter, “High Operating Costs Cloud the Future of Littoral Combat ships, Budget Data Reveals,” Defense News, April 12, 2021, https:// www.defensenews.com/naval/2021/04/12/high-operating-costs-cloud-the-future-of-littoral-combat-ships-budget-data-reveals/ (accessed June 13, 2022). 15. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Next Generation Combat Vehicles: As Army Prioritizes Rapid Development, More Attention Needed to Provide Insight on Cost Estimates and Systems Engineering Risks, GAO-20-579, August 2020, p. 1, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-579.pdf (accessed July 26, 2022). 16. Ibid., pp. 1 and 35. 17. See National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force, Report to the President and Congress of the United States, January 30, 2014, https://policy.defense.gov/Portals/11/Documents/hdasa/AFForceStructureCommissionReport01302014.pdf (accessed July 26, 2022), and National Commission on the Future of the Army, Report to the President and the Congress of the United States, January 28, 2016, https://www. nationalguard.mil/Portals/31/Documents/ARNGpdfs/ncfa/NCFA-Full-Final-Report.pdf (accessed July 26, 2022). 18. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, April 30, 2022, p. 36, https://www. sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2022-04-30qr.pdf (accessed July 11, 2022). See also Figure F.4, “Afghanistan Cost of War and Reconstruction, Annual and Cumulative Obligations FY 2002 to FY 20021 Q4,” in ibid., p. 37. 19. U.S. Department of Defense, Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), “Estimated Cost to Each U.S. Taxpayer for the Wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria,” March 2021, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/documents/Section1090Reports/Estimated_Cost_to_Each_U.S._Taxpayer_ of_Each_of_the_Wars_in_Afghanistan,_Iraq_and_Syria_dated_March_2021.pdf (accessed July 11, 2022). 20. U.S. Department of Defense, Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), “Estimated Cost to Each U.S. Taxpayer for the Wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria,” June 2022, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/documents/Section1090Reports/Estimated_Cost_to_Each_U.S._Taxpayer_ of_Each_of_the_Wars_in_Afghanistan,_Iraq_and_Syria_dated_June_2022.pdf (accessed July 11, 2022). 21. Table 2, “Estimated Costs Attributed to the Major War Zones, FY2001–FY2022,” in Neta C. Crawford, “The U.S. Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars,” Brown University, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Cost of War Project, September 1, 2021, https://watson.brown.edu/ costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/Costs%20of%20War_U.S.%20Budgetary%20Costs%20of%20Post-9%2011%20Wars_9.1.21.pdf (accessed July 11, 2022). 22. Christopher T. Mann, “U.S. War Costs, Casualties, and Personnel Levels Since 9/11,” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. IF11182, April 18, 2019, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11182/1 (accessed July 11, 2022). 23. Diana Maurer, Director, Defense Capabilities and Management, U.S. Government Accountability Office, “F-35 Sustainment: Enhanced Attention to and Oversight of F-35 Affordability Are Needed,” testimony before the Subcommittees on Readiness and Tactical Air and Land Forces, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, GAO-21-505T, April 22, 2021, p. 1, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-505t.pdf (accessed June 13, 2022). 62 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 24. Ibid., pp. 4 and 21–23. 25. Ibid., p. 16. 26. John Venable, “Air Force’s Math on the F-15EX and F-35 Doesn’t Add Up,” Breaking Defense, April 19, 2022, https://breakingdefense. com/2022/04/air-forces-math-on-the-f-15ex-and-f-35-doesnt-add-up/?_ga=2.116581710.950593788.1650383248-951717084.1641387148 (accessed June 13, 2022). 27. In his original article, the author quoted a price of $136.0 million. It has since been determined that the Eagle Passive Active Warning Survivability System (EPAWSS) was included in the airframe cost of the F-15EX. Subtracting that cost from the quoted price of $136.0 million results in a gross weapon systems cost for the F-15EX of $120.2 million. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 63 Global Operating Environment Assessing the Global Operating Environment M provide needed support for future U.S. military operations. The relationships and knowledge gained through any of these factors would undoubtedly ease future U.S. military operations in a region and contribute greatly to a positive operating environment. In addition to U.S. defense relations within a region, additional criteria—including the quality of the local infrastructure, the area’s political stability, whether or not a country is embroiled in any conflicts, and the degree to which a nation is economically free—should also be considered. Then there are low-likelihood, high-consequence events that occur infrequently but that, when they do happen, can radically alter conditions in ways that affect U.S. interests. Massive natural disasters like Typhoon Tip in 1979 or the explosion of Mount Tambora in 1816 can displace populations, upend regional power arrangements, or destroy critical infrastructure. The eruption of Mount Pinatubo did just that in 1991, causing so much damage to Clark Airbase and Subic Bay Naval Station that the cost, combined with diplomatic frictions between the U.S. and the Philippines, led the U.S. to abandon these strategic facilities. A massive solar flare could have a similar impact on a much larger scale because of the level of dependence on electrical power across our world. Scientists, analysts, planners, and officials in public and commercial ventures study such things but seldom take concrete action to mitigate their potential impact. For the past two years, the world has been shaken by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused governments to spend extraordinary sums of money not only to manage the public health crisis, but also to mitigate the economic impact on their countries. The economic and societal stresses stemming from the pandemic have put terrific pressures on political establishments. They also have caused funding for such essential government functions as defense to The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 67 easuring the strength of a military force—defined as the extent to which that force can accomplish missions—requires examination of the environments in which the force operates. Aspects of one environment may facilitate military operations; aspects of another may work against them. A favorable operating environment presents the U.S. military with obvious advantages; an unfavorable operating environment may limit the effect of U.S. military power. The capabilities and assets of U.S. allies, the strength of foes, the willingness of friend or foe to use its military power, the region’s geopolitical environment, and the availability of forward facilities and logistics infrastructure all factor into whether an operating environment can support U.S. military operations. When assessing an operating environment, one must pay particular attention to any U.S. treaty obligations with countries in the region. A treaty defense obligation ensures that the legal framework is in place for the U.S. to maintain and operate a military presence in a particular country. In addition, a treaty partnership usually yields regular training exercises and interoperability as well as political and economic ties. It also obligates the U.S. to commit its military in support of an ally, which has the effect of focusing U.S. military leadership on some regions more than others. Additional factors—including the military capabilities of allies that might be useful to U.S. military operations; the degree to which the U.S. and allied militaries in the region are interoperable and can use, for example, common means of command, communication, and other systems; and whether the U.S. maintains key bilateral alliances with nations in the region—also affect the operating environment. Similarly, nations where the U.S. has stationed assets or permanent bases and countries from which the U.S. has launched military operations in the past may substantially increased their defense budgets and, among European allies, have contributed equipment, munitions, and a range of supplies to Ukraine to help it defend itself. One consequence of this has been reinvigorated discussions among U.S. allies about the status of military power and the need to ensure that forces can work together effectively. But another has been the consumption of expensive military capabilities, which has led some countries to start hedging on their pledges to sustain support to Ukraine or, in some circumstances, to contribute national power to collective defense. All of this to say that conditions evolve from one year to the next and from one security setting to the next in ways that affect the ease or difficulty of conducting U.S. military operations. The operating environment assessment is meant to add critical context to complement the threat environment and U.S. military assessments that are detailed in subsequent sections of the 2023 Index. A final note: This Index refers to all disputed territories by the names employed by the United States Department of State and should not be seen as reflecting a position on any of these disputes. be reallocated to meet the more immediate demands of the pandemic and—given the threat of contagion— mitigation measures to be adopted at the expense of military exercises, training events, and deployments. As of mid-2022, most countries appear to have resolved many of the disruptions caused by the pandemic, adapting their economies and adjusting their policy approaches to deal with the public health crisis. So, too, have populations that have normalized their routines, mitigating many of the original fears stemming from the crisis. In similar fashion, military forces have found ways to return to training and exercises that are necessary to regain proficiency. Most recently, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 has affected national and public perspectives with regard to military power. Before Russia invaded its neighbor, many capitals acknowledged the importance of military power but often failed to follow their words with commensurate investments in operationally relevant military forces. Confronted with the reality of a war in Europe and the possibility of another one in Asia because of China’s persistent saber rattling and heavy investment in its ability to project power, Poland, Germany, Great Britain, and Japan, to name but a few, have 68 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Europe Daniel Kochis T The Russian Federation is the most significant and direct threat to Allies’ security and to peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area. It seeks to establish spheres of influence and direct control through coercion, subversion, aggression and annexation. It uses conventional, cyber and hybrid means against us and our partners. Its coercive military posture, rhetoric and proven willingness to use force to pursue its political goals undermine the rules-based international order.3 Additionally, the new concept recognizes China as a major challenge: “The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values,” and “[t]he deepening strategic partnership between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation and their mutually reinforcing attempts to undercut the rules-based international order run counter to our values and interests.”4 In addition to taking steps to bolster NATO’s collective defense capability, the U.S. and its allies have made significant investments in arming and training the Ukrainian military. What began as individual nations supplying arms, ammunition, and supplies (often surplus) has evolved into a sustained flow of intelligence, weapons, matériel, and platforms upon which Ukrainian forces have become entirely reliant. Some nations have even begun to repair damaged Ukrainian equipment. In addition to military aid and intelligence, European nations in particular have accepted millions of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war. All of this illuminates the reality that war is still a feature of international relations that cannot be predicted or always deterred, that is costly both in preparation and undertaking, and that generates additional costs (such as support for refugees and disruption of economic activity) beyond the straightforward expense of equipment and training. The 51 countries in the U.S. European Command (USEUCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) include approximately one-fifth of the world’s population, 10.7 million square miles of land, and 13 million The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 69 he past year has seen significant and swift changes in U.S. force posture in Europe and the trajectory of allied capabilities because of Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine in February.1 The scale, scope, and intensity of conventional military power used by Russia led to a renewed appreciation for such power in many European capitals that had neglected their militaries since the end of the Cold War. In April, a U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) spokesperson stated that “[t]he European security environment has changed and will stay changed as a result of [Russian President Vladimir] Putin’s willingness to conduct an unprovoked invasion of a neighboring state.”2 The U.S. has reintroduced additional manpower and capabilities into Europe and is reevaluating its long-term basing posture. European NATO allies have deployed in support of alliance deterrence efforts in eastern Europe, and many have renewed their commitment to NATO spending benchmarks and rebuilding military capabilities that have atrophied over the past 30 years. In June, NATO invited Finland and Sweden to join the alliance. Also in June, the alliance adopted a new Strategic Concept at its Madrid summit. The first new concept since 2010, it takes into account the comprehensive changes in the transatlantic security environment that have taken place during the past 12 years. With respect to Russia, it states clearly that: square miles of ocean. Some of America’s oldest (France) and closest (the United Kingdom) allies are found in Europe. The U.S. and Europe share a strong commitment to the rule of law, human rights, free markets, and democracy. During the 20th century, millions of Americans fought alongside European allies to defend these shared ideals—the foundations on which America was built. America’s economic ties to the region are likewise important. A stable, secure, and economically viable Europe is in America’s economic interest. For more than 70 years, the U.S. military presence has contributed to regional security and stability, and both Europeans and Americans have benefited economically. The member states of the European Union (EU), along with the United States, account for approximately half of the global economy, and the U.S. and EU member countries are generally each other’s principal trading partners. Europe is also important to the U.S. because of its geographical proximity to some of the world’s most dangerous and contested regions. From the eastern Atlantic Ocean to the Middle East, up to the Caucasus through Russia, and into the Arctic, Europe is enveloped by an arc of instability. The European region also has some of the world’s most vital shipping lanes, energy resources, and trade choke points. European basing allows U.S. forces to respond robustly and quickly to challenges to U.S. economic and security interests in and near the region. Russia’s brutal effort to remake the borders of Europe by force has shocked many partners, upended the continent’s strategic picture, and begun a war with implications that are far wider than the sovereignty of Ukraine itself. Admiral Robert Burke, Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Europe, U.S. Naval Forces Africa, and Allied Joint Forces Command Naples, for example, has described the European and African theaters as “the forefront of great power competition.”5 Other external threats to European security include Russia’s activity in the Arctic, growing presence in the Mediterranean theater, and efforts to destabilize Western cohesion in addition to the possibility that Russia might expand the scope of its aggression to include the eastern states of NATO. Added to this is the growing threat to the transatlantic alliance that is posed by Chinese investments, technology, and propaganda efforts. Russian naval activity in the North Atlantic and Arctic has necessitated a renewed focus on regional command and 70 control and has led to increased operations by U.S. and allied air and naval assets in the Arctic, and Russia’s strengthened position in Syria has led to a resurgence of Russian activity in the Mediterranean that has contributed to “congested” conditions.6 Speaking at an Atlantic Council meeting in March 2019, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Joseph Dunford explained that the U.S. has two key advantages over adversaries: “our network of allies and partners, and the ability to project power where and when necessary to advance our national interest.”7 Nowhere is the value of allies and U.S. basing more apparent than it is in the European operating environment. U.S. Reinforcements in Europe. Russia’s war against Ukraine greatly accelerated a trend of U.S. reinvestment in Europe that had begun following Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014. In April 2014, the U.S. launched Operation Atlantic Resolve (OAR), a series of actions meant to reassure U.S. allies in Europe, particularly those bordering Russia. Under Operation Atlantic Resolve and funded through the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), the U.S. increased its forward presence in Europe; invested in European basing infrastructure and in prepositioned stocks, equipment, and supplies; engaged in enhanced multinational training exercises; and negotiated agreements for increased cooperation with NATO allies. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine spurred the U.S. to increase forces flowing to Europe and ignited a U.S. and NATO-wide reevaluation of long-term basing structures and force posture requirements to deter Russian aggression from spilling over to alliance member states, especially those like Poland, whose role as a staging ground for aid to Ukrainian forces has made it a Russian target.8 In January 2022, the U.S. had approximately 80,000 troops in Europe (permanent and rotational); that number grew to more than 100,000 by March.9 A month after Russia’s invasion, [T]he U.S. ha[d] activated about 11,600 troops for the mission: 4,700 from the 82nd Airborne Division to Poland; 300 from the XVIII Airborne Corps to Germany; 1,000 from the 2nd Cavalry Regiment to Romania; 800 from the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team to Latvia; 100 F-35 Lightning II air crew to Estonia, Lithuania and Romania; 100 AH-64 Apache aircrew to 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength CHART 2 Few U.S. Troops in Europe Are Stationed Near Russia 75,000 72,405 50,000 Germany 42,000 25,000 U.K. 11,500 0 Italy 10,000 12,960 Nations Not Bordering Russia Nations Bordering Russia 12,500 Poland 10,500 SOURCE: U.S. European Command, written response to Heritage Foundation request for information on U.S. troop levels in Europe, July 7, 2022. Troops at Sea A heritage.org the Pentagon, “These Growlers…are equipped for a variety of missions. But they do specialize in flying electronic warfare missions, using a suite of jamming sensors to confuse enemy radars, greatly aiding in the ability to conduct suppression of enemy air defense operations.”12 From February through April, three B-52 Stratofortress aircraft and 300 troops from North Dakota rotated to a base in the United Kingdom as part of the Bomber Task Force Mission, flying regularly over European airspace.13 The U.S. has brought additional air assets to EuThe U.S. has also begun to consider new permarope. The U.S. Air Force (USAF), for example, “has nent basing in eastern European NATO member moved additional fighters, tankers, and intelligence, states. In April 2022, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft into the General Mark Milley voiced his support for permaEuropean theater over the past few months, as well nent U.S. bases in eastern Europe but with troops as bombers on a rotational basis, all to reassure deployed rotationally “‘[s]o you get the effect of NATO allies who feel threatened by the invasion permanence’ at a lesser cost because expenses such of Ukraine.”11 In March 2022, six U.S. Navy EA-18G as family housing and schools are not involved.” “I Growlers and 240 troops deployed to Spangdahlem believe a lot of our allies, especially those such as Air Base in Germany from Washington State to the Baltics or Poland or Romania…are very willing bolster alliance collective defense. According to to establish permanent bases,” Milley noted. “They Poland and the Baltic states; 3,800 from 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division and its sustainment unit to Germany; 150 airmen from Fairchild Air Force Base, Washington; 40 members of an air support operations unit to Romania and Poland; 300 ordnance and maintenance soldiers to Germany; and 300 members of V Corps to Germany and Poland.10 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 71 will build them and pay for them.”14 In May, respond- Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), ing to advance questions as part of Senate Armed highlighted the importance of EDI funding in reServices Committee hearings on his nomination turning the United States to a posture of deterrence: to serve as Commander, U.S. European Command and Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, General EDI enhances our posture to deter adversaries Christopher Cavoli similarly stated that “permaand compete in a contested logistics environnently assigned forces are more operationally effecment alongside our European defense countive, as they remain fully oriented to the operational terparts. Increases in forward stationed and environment and can become interoperable with rotational forces strengthen our contact, blunt, 15 our Allies and Partners.” and surge layer capabilities, providing an ability European Deterrence Initiative. On top of reto compete and win in a multi-domain crisis or newed investments in Europe, the U.S. has continconflict. EDI investments improve theater infraued with more established efforts to bolster collecstructure and prepositioned stocks. Funding for tive defense in Europe. The Biden Administration exercises, training, and building partner capachas requested $4,176.9 billion for the European Deity strengthens the readiness, architecture, and terrence Initiative in fiscal year (FY) 2023, which interoperability across the Euro-Atlantic area. would be a $365.3 million increase from the enacted These advances enable our deterrence and FY 2022 EDI budget of $3,811.6 billion.16 EDI funddefense efforts through rapid deployment and ing requests for FY 2023 include (among others): sustainment of forces.18 The EDI has supported infrastructure improvements across the region. One major EDI-funded project is a replacement hospital at Landstuhl, Germany, to be named the Rhine Ordnance Barracks Medical Center. Originally slated to be completed in 2022, it is now expected that it will be completed in 2027. The new permanent facility will “provid[e] Exercises to “increase[] the overall readiness primary care, specialized consultative care, hospiand interoperability of U.S. forces across all talization and treatment for more than 200,000 U.S. domain” and “improve[] the interoperability military personnel, DoD and interagency civilians of U.S. forces with our NATO Allies and theand dependents in Europe.”19 Landstuhl’s imporater partners.” tance is illustrated by the fact that in early March 2020, it was one of the first two overseas U.S. labInfrastructure improvements that include oratories to be capable of testing for coronavirus.20 “purchasing new fixed undersea surveillance In addition to the EDI, as of the end of 2021, the systems and refurbishment of older, existing U.S. Department of State had awarded nearly $300 systems already in place throughout the AOR” million in grants since 2018 through its European and improving “airfield infrastructure and Recapitalization Incentive Program (ERIP) and prepositioned storage capability to support U.S. repurposed funds to help U.S. allies in Europe reAir Forces in Europe operations, actions, and place Russian equipment with U.S.-made equipactivities.” ment. This includes infantry fighting vehicles for Croatia, Greece, and North Macedonia; helicopters “Providing our Allies and partners with the for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lithuania, capability and capacity to better defend themand Slovakia; and air surveillance radars and fixedselves and to enable or enhance their participa- wing aircraft for Bulgaria. The program helps allies tion as full operational partners against threatto “modernize their militaries by building NATO ening actors….”17 interoperable forces and removing Russian and Soviet-legacy equipment from their force structure.”21 Testifying in March 2022, General Tod Wolters, Forward Presence. In April 2022, the 3rd Armored Commander, U.S. European Command, and NATO’s Brigade Combat Team (ABCT) of the 4th Infantry l “[Continued support for] rotational force deployments, infrastructure investments, and [delivery of ] the right capabilities in key locations throughout Europe (i.e., Air Force-European Contingency Air Operations Sets (ECAOS), Army Prepositioned Stocks (APS)).” l l l 72 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength [The agreement] covers matters such as the establishment of a forward division command in Poznan, stationing of a rotationally-present armoured brigade in Żagań-Świętoszów, deployment of Reaper UAVs squadron to Łask, the establishment of a Polish-US combat training centre (CTC) in Drawsko Pomorskie, the establishment of an airlift cargo hub for USAF in Wrocław-Starachowice, the establishment of the presence of an Army Aviation Brigade on a rotational basis, and a logistics battalion as well as special ops facility in Powidz, and another special ops facility in Lubliniec.32 The U.S. Army’s V Corps, which had been deactivated in 2013, was reactivated on November 9, 2020, and became fully operational in November 2021.33 In June 2022, President Joseph Biden announced that the U.S. would establish the permanent V Corps headquarters in Poland.34 In March, the headquarters, then based in Kentucky, was largely deployed to Europe “to provide additional command and control of U.S. Army forces in Europe” and to “to build readiness, improve interoperability, reinforce allies and deter further Russian aggression.”35 By April, the U.S. had deployed more than 10,000 troops to Poland including forces helping to aid Ukrainian refugees and facilitate the flow of weapons and aid to Ukraine.36 In March 2022, the U.S. Defense Department confirmed that U.S. troops were “liaising” with Ukrainian forces in Poland as weapons are handed over but not training “in the classic sense.”37 By the end of April, the Pentagon confirmed that the U.S. was training Ukrainian forces in Germany on systems that include armored vehicles, artillery, and radar.38 The U.S. has strengthened its presence in Norway as well. In April 2021, the two nations signed the Supplementary Defense Cooperation Agreement, which allows the U.S. to build additional infrastructure at Rygge and Sola Air Stations in southern Norway as well as Evenes Air Station and Ramsund Naval Station above the Arctic Circle.39 Construction at Evenes will support the monitoring of Russian submarine activity by Norwegian and allied maritime patrol aircraft. According to former Norwegian Foreign Minister Ine Eriksen Soereide, “The agreement reaffirms Norway’s close relationship with the U.S. and confirms Norway’s key position on the northern flank of NATO.”40 In October 2021, the U.S. Navy The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 73 Division from Fort Carson, Colorado, replaced the outgoing BCT in the ninth armored rotation in support of Operation Atlantic Resolve.22 The BCT consisted in part of 4,000 troops, 90 tanks, 15 Paladins, and 150 infantry fighting vehicles. Many analysts have noted the special importance of ground forces for deterrence. “Land forces provide traditional ‘boots on the ground’ and a visible presence among local populations,” according to one recent analysis. “They can also enhance the credibility of deterrence through bringing to bear the heavy ground forces required to defend, seize, and hold territory in the event of conflict.”23 In addition to back-to-back rotations of armor, the U.S. has maintained a rotational aviation brigade in Europe since February 2017.24 The eighth such rotation, lasting from November 2021–July 2022, has been the 1st Air Cavalry Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division from Fort Hood, Texas, with 2,000 troops, 10 CH-47 Chinooks, 25 AH-64 Apaches, and 35 UH-60 and 15 HH-60 Black Hawk helicopters.25 In May 2018, the U.S. began to fly MQ-9 Reaper drones on unarmed reconnaissance flights out of Miroslawiec Air Base in Poland. The drones became fully operational in March 2019 when U.S. Air Force officials stated that Poland was chosen for the MQ-9s because of its “strategic location.”26 In June 2020, runway work at Miroslawiec caused drones to be moved temporarily to Ämari Air Base in Estonia, marking the first time that unmanned U.S. aircraft have operated out of Estonia.27 In January 2021, the U.S. announced that 90 USAF personnel and an unspecified number of MQ9s would be based at Campia Turzii in Romania “to conduct intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions in support of NATO operations.”28 According to General Jeffrey Harrigian, Commander of U.S. Air Forces in Europe, U.S. Air Forces Africa, and Allied Air Command, the new permanent base’s location approximately 300 miles from the coast “really facilitates our ability to compete in the Black Sea.”29 In addition to Ämari, Miroslawiec, and Campia Turzii, the U.S. also operates MQ-9s out of Lask Air Base in Poland.30 In August 2020, the U.S. and Poland signed the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, which entered into force in November 2020. The agreement increased U.S. rotational forces in Poland by 1,000 people and provided for more exercises and infrastructure development to support a deployment of 20,000 U.S. troops if necessary.31 In addition: deployed a mobile “Expeditionary Medical Facility to a cave system near Bogen Bay in northern Norway, some 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle.”41 According to the operations director for the U.S. Navy Expeditionary Medical Support Command (NEMSCOM), “Expeditionary Medical Facilities are deployable on short notice and contain many capabilities of a modern hospital.”42 In August 2020, the Marine Corps announced the end of heel-to-toe rotations of 700 Marines to Norway, which began in 2017, opting for shorter, more sporadic deployments.43 The first new deployment in October 2020 consisted of 400 Marines, and in the second, 1,000 Marines were deployed to Setermoen, Norway, from January–March 2021 for Arctic warfare training.44 Major General Patrick J. Hermesmann, former Commander of U.S. Marine Corps Forces Europe & Africa, has noted the growing relationship between Norway and the U.S. through “shared hardship of tough, realistic training in this austere environment.”45 From March–April 2022, Norway hosted NATO’s Cold Response 2022, the largest Norwegian-led exercise since the Cold War. Among the participants were 3,000 American Marines.46 In addition to ground forces, in February and March 2021, four B-1 Lancers were based out of Ørland Air Station in southern Norway, marking the first time the aircraft have been based in Norway.47 The Lancers conducted training exercises with allies Denmark, Germany, Italy, Norway, and Poland while also practicing landing and refueling at Bodø Air Base above the Arctic Circle.48 In October 2020, at the behest of the United States, Norway announced the reopening of Olavsvern bunker, a mountainside submarine base near Tromsø with “9,800ft of deep water underground docks that can house and refit nuclear submarines.” The base, which had been closed in 2002, is now open to U.S. Seawolf-class nuclear submarines.49 The U.S. also continues to rotate a Sustainment Task Force “comprised of nearly 1,000 personnel and 200 pieces of equipment” from “11 active duty, U.S. Army Reserve and National Guard units.” The units that make up the task force are varied and “include ammunition, fuel, movement control, transportation, maintenance, ordnance, supply, and postal services.”50 During the June 2022 NATO Summit, the U.S. announced additional deployments to Europe 74 including (among others) deployment of a new rotational Brigade Combat Team to Romania; enhanced rotational deployments of “armored, aviation, air defense, and special operations forces” to the Baltics; deployment of “two squadrons of F-35s at RAF Lakenheath”; the forward stationing of an “air defense artillery brigade headquarters, a short-range air defense battalion, a combat sustainment support battalion headquarters, and an engineer brigade headquarters” in Germany; and the forward stationing of “a short-range air defense battery” in Italy.51 Operation Atlantic Resolve’s naval component has consisted partly of increased deployments of U.S. ships to the Baltic and Black Seas since 2014. In 2021, the U.S. spent 111 days in the Black Sea, significantly more than the 82 days it spent there in 2020.52 Russian undersea activity continues at an elevated level. The U.S. Navy reestablished the 2nd Fleet, which is “responsible for the northern Atlantic Ocean,” in May 2018 nearly seven years after it had been disbanded in 2011.53 The 2nd Fleet reached full operational capability at the end of 2019.54 The fleet was reestablished because of Russian militarization of the Arctic.55 “This is where the fight is…where the competition is,” according to Vice Admiral Andrew Lewis, former Commander of the 2nd Fleet. “Specifically in the Atlantic [and] the undersea capability of the Russians.”56 In March 2021, in a statement exercise, three Russian ballistic missile submarines punched through ice in the Arctic near the North Pole.57 For Vice Admiral Lewis, “[a]nti-submarine warfare is a primary mission for everybody in the United States Navy, regardless of what you wear on your chest.”58 Admiral Burke has stated that the 6th Fleet keeps units operating “nearly continuously” in the Arctic and that U.S. submarines “really dominate that area.”59 The U.S. also has capable partners in patrolling Arctic waters including the “U.K. and France to name two extremely reliable [and] capable partners.” In addition: Canada…Norway…all contribute significantly to the theater of undersea warfare fight. Denmark is expanding their capabilities. Now almost every one of those nations that I’ve mentioned now have significant airborne maritime patrol reconnaissance aircraft, if not the P-8A version, closely resembling the P-8 capabilities. Many have bought versions similar to the P-8. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Their surface combatants today are incredibly capable too.60 In the ground domain, we expect to establish a U.S. division-sized capability through forward-stationed forces, rotational forces, and Army Prepositioned Stocks (APS). Continued In March 2022, NATO opened its first Multinational Ammunition Warehousing Initiative (MAWI) in Estonia for allies to store munitions for EFP deployments. The alliance plans further MAWI sites to support EFP deployments and the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF).70 NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg noted in June, “if there’s any lesson to be learned from Ukraine [it] is the importance of heavy equipment in place, but also fuel, ammunition, supplies.”71 By April, the U.S. had deployed Joint Munitions Command experts to Germany and Poland to provide “expert technical ammunition and explosives assistance and support to units stationed in or deployed to Europe.”72 Aid to Ukraine. The U.S. and its allies have provided significant military aid to Ukraine. By early May, the U.S. had provided Ukraine with $3.8 billion in security assistance since the beginning of Russia’s second invasion.73 In April, President Biden stated that “[t]he United States alone has provided 10 anti-armor systems for every one Russian tank that’s in Ukraine—a 10-to-1 ratio,” adding that “[w]e’ve sent thousands of anti-armor and anti-missile helicopters, drones, grenade launchers, machine guns, rifles, radar systems.”74 By mid-April, according to U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin: [The U.S. had sent Ukraine] over 1,400 stingers, over 5,500 Javelins, over 14,000 other anti-armor weapons, over 700 switchblade tactical unmanned aerial systems, 18 155mm Howitzers, The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 75 In recent years, the U.S. has also made a point of publicly acknowledging the surfacing of nuclear-powered submarines in Arctic waters as a message of deterrence. One such example occurred in May 2021, when the Virginia-class submarine USS New Mexico docked in Tromsø, Norway.61 Outside the Arctic, as explained by General Wolters, “Rarely navigated by Russia since the 1990’s, advances in its submarine fleet and expanding maritime strategic goals have reinvigorated Russia’s access to the broader Atlantic Ocean.”62 These changes have led officials to state that the U.S. east coast is no longer “a safe haven.”63 Russia has also increased its naval capabilities in the Mediterranean, utilizing its naval base in Tartus, Syria. In February 2022, the U.S. and its allies detected an unusual positioning of three Russian guided missile cruisers in the Mediterranean near U.S., French, and Italian Carrier Strike Groups operating in theater.64 One analyst assessed that “Russia has reinforced its naval presence in the Mediterranean, much more than usual. This can be seen as an outer defense layer for naval operations in the Black Sea, off Ukraine. In particular, to deter NATO involvement, especially from the US and French aircraft carriers.”65 Prepositioned Stocks. The U.S. continues to preposition equipment in Europe across all services. In February 2022, the U.S. activated its Army Prepositioned Stock-2 across six sites to outfit an armored brigade combat team deploying from the U.S.66 The FY 2023 budget request includes $1,273.9 billion to support enhanced prepositioning for the U.S. Army, Air Force, and Special Forces.67 With specific respect to the Army, DOD’s FY 2023 budget request includes “funding to continue the build of a division-sized set of prepositioned equipment with corps-level enablers that is planned to contain two ABCTs (one of which is modernized), two Fires Brigades, air defense, engineer, movement control, sustainment and medical units.”68 In March 2022, General Wolters testified that: investment in APS equipment facilitates increased agility and lethality by enabling rapid integration of rotational combat units into USEUCOM and NATO operations. During Exercise DEFENDER-Europe 21, U.S. Army Europe and 26 participating nations demonstrated readiness to command and control large-scale operations by exercising at the battalion and brigade levels while building interoperability. In Exercise DEFENDER-Europe 24, we plan to assemble a divisional formation on NATO’s eastern flank for the first time since the end of the Cold War, conducting a multinational command post exercise with U.S. and multinational divisions and brigades operating under U.S. Army Europe leadership. These prepositioned stocks enabled us to respond swiftly in response to Russia’s aggression in and around Ukraine.69 CHART 3 Nations Hosting Ukrainian Refugees REFUGEES, IN MILLIONS HOST NATION AS % OF HOST NATION POPULATION Poland Germany Czech Republic Italy Turkey Spain United Kingdom United States France Moldova Slovakia Bulgaria Romania Austria Netherlands Lithuania Switzerland Belgium Estonia Portugal Ireland Sweden Latvia Finland Denmark Hungary Georgia Norway Greece Croatia Cyprus Belarus Montenegro Slovenia Luxembourg North Macedonia Albania Iceland Malta Liechtenstein Bosnia and Herzegovina 1.2 0.9 0.6 0.3 0.0 0% 1% 2% 3% 4% NOTES: According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, these numbers reflect “the estimated number of individual refugees who have fled Ukraine since 24 February and are currently present in European countries.” Border crossings are far higher. Russia has been excluded from the list due to the large number of Ukrainian deportations. Belarus is a belligerent alongside Russia in the war against Ukraine. SOURCES: U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, “Operational Data Portal: Ukraine Refugee Situation,” July 6, 2022, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed September 8, 2022), and Camilo Montoya Galvez, “U.S. Admits 100,000 Ukrainians in 5 Months, Fulfilling Biden Pledge,” CBS News, July 29, 2022, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-admits-100000-ukrainians-in-5-monthsfulfilling-biden-pledge/ (accessed September 8, 2022). A 76 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength heritage.org 16 Mi-17 helicopters, 200 M113 Armored Personnel Carriers, 75,000 sets of body armor and helmets, two air surveillance radars, 14 counter artillery radars, 4 counter mortar radars, unmanned coastal defense vessels, tactical secure communications systems, over 7,000 small arms, and 50,000,000 rounds of ammunition.75 This is an historic moment and the very first time the Alliance has employed these high readiness forces in a deterrence and defence role. They represent a flexible, combat credible force that can be employed in multiple ways, and we are utilizing fully their inherent agility. U.S. allies have also donated large amounts of military hardware. By April, the EU had funded €1.5 billion in military aid to Ukraine.76 In May, it was reported that Estonia and Latvia had donated approximately a third of their military budgets to Ukraine, Poland had donated around 13 percent, and Slovakia had donated nearly 12 percent.77 In April, France announced that it was sending Caesar self-propelled howitzers.78 The French also have trained “Ukrainian soldiers in France on how to use the powerful guns.”79 Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and the U.S. have donated U.S. Javelin and Stinger missiles, leaving holes in their own inventories that need to be backfilled.80 The rate of system use in Ukraine, combined with “an aged and insecure production infrastructure, riddled with potential bottlenecks, vulnerabilities, and supply challenges,” could make this difficult for the U.S.81 By mid-April, for example, the U.S. reportedly had “provided one-third of its overall stockpile of Javelin anti-tank missiles. It cannot easily deliver more without leaving its own armories badly depleted—and it may take months or years to significantly ramp up production.”82 Air defense is a particular problem for Ukrainian forces. In April, Slovakia announced that it was sending an S-300 air defense system to Ukraine, and the Netherlands deployed Patriot missile batteries to Slovakia “in order to reinforce the eastern flank of the NATO area.” A Defence Ministry spokesman said that the Netherlands “will also send S-300 anti-aircraft systems to Ukraine at NATO’s request.”83 The United Kingdom, a particular leader in aiding Ukraine, has announced its intention to supply Ukraine with anti-ship missiles.84 The U.S. has trained Ukrainian forces outside of Ukraine, including a group of around 50 Ukrainian soldiers that it trained to operate U.S. howitzers.85 The United Kingdom has been training Ukrainians on the use of AS-90 howitzers and armored vehicles, principally in Poland but also smaller contingents of Ukrainian forces inside the U.K.86 In April, the Czech Republic announced that its defense firms would begin repairing Ukrainian tanks and armored vehicles. Czech Defense Minister Jana Cernochova stated that “[t]he Czech Republic is the first partner country that the Ukrainian side has officially approached for cooperation in repairing ground weapons which need to be put into service or were damaged during combat.”87 In addition to military training and aid, the transatlantic community has accepted large numbers of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war. Poland has accepted more than 3,000,000—by far the largest total since the beginning of the war.88 Other nations have accepted numbers that are far smaller but still significant in proportion to the receiving nation’s population. NATO Responses to Russia’s War in Ukraine. On February 25, 2022, for the first time in its history, NATO activated approximately one-third of its 40,000-strong NATO Response Force (NRF).89 In announcing the activation General Wolters stated that: These deterrence measures are prudent and enhance our speed, responsiveness and capability to shield and protect the one billion citizens we swore to protect.90 In January 2022, the U.S. announced that 8,500 troops would be put on alert for possible deployment as part of the NRF.91 In February, Canada announced that 3,400 troops would be placed on standby for the same purpose.92 In addition to ground forces, NATO has 130 aircraft on alert and more than 200 ships operating in theater.93 In June, the alliance announced that the NRF would be increased in size from 40,000 to 300,000. Secretary General Stoltenberg noted that “for the first time since the Cold War, we will have pre-assigned forces to defend specific Allies” and will be able to “reinforce much faster if needed.”94 It should be noted, however, that Stoltenberg’s announcement appeared to have caught some NATO members by surprise, leading an unnamed NATO official to say that “[t]he concept has not been fully worked The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 77 MAP 1 NATO Nations Collaborate on Russian Deterrence Measures Since Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine, NATO has put in place new measures in eastern Europe to deter Russia. In 2014, it established Enhanced Forward Presence Multinational Battalions in four member states in the Baltic Sea region. In 2022, additional battalions were added in four member states in central Europe and the Black Sea region. Most of those same nations also benefit from NATO air policing operations. FINLAND NORWAY SWEDEN ESTONIA RUSSIA LATVIA DENMARK LITHUANIA NETHERLANDS BELARUS U.K. POLAND GERMANY BELGIUM UKRAINE CZECH REP. SLOVAK REP. AUSTRIA FRANCE MOLDOVA HUNGARY ROMANIA SERBIA BULGARIA ITALY Black Sea SPAIN TURKEY Mediterranean Sea Enhanced Forward Presence Multinational Battalions ■ Established 2014 ■ Established 2022 Battalion location Air Policing Operations Approximate patrol areas Air bases SOURCE: Heritage Foundation research. 78 A 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength heritage.org As long as nuclear weapons exist, NATO must remain a nuclear Alliance. NATO’s nuclear capability preserves peace, prevents coercion, deters aggression, and instills confidence in the transatlantic bond. The United States continues to make available its strategic nuclear forces to the defense of NATO and they are the supreme guarantee of the security of our Allies.102 It is believed that until the end of the Cold War, the U.S. maintained approximately 2,500 nuclear warheads in Europe. Unofficial estimates range between 150 and 200 warheads spread out across bases in Belgium, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Turkey.103 In October 2019, reports surfaced that the U.S. was considering moving the approximately 50 tactical nuclear weapons stored at Incirlik Air Base in Turkey in light of ongoing tensions, but this has not happened. All of these weapons are free-fall gravity bombs designed for use with U.S. and allied dual-capable aircraft. Although tactical nuclear weapons are forward deployed to Incirlik, “there are no aircraft capable of delivering the B-61 gravity bombs co-located at Incirlik Airbase.”104 The U.S. has nuclear sharing agreements with Belgium, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands that allow for delivery of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons by allied aircraft, but no such agreement is in force with Turkey: “The weapons at Incirlik Air Base in Turkey are solely for use on U.S. aircraft.”105 The B61 nuclear gravity bomb that is “deployed from U.S. Air Force and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) bases” is undergoing a life extension program that is expected to add at least 20 years to its service life and “improve the B61’s safety, security, and effectiveness.”106 The B61-12 bomb, according to U.S. officials, is “intended to be three times more accurate than its predecessors.”107 The first production unit was completed in February 2022, and the extension program is to be completed by 2026.108 In October 2021, the Air Force completed a full weapons system demonstration that was “the flight test portion of the nuclear design certification process for the latest B61 series weapon,” allowing the program to move “into the nuclear operational certification phase, essentially clearing the [F35-A] and weapon for frontline service.”109 China. At NATO’s 2019 leaders meeting in London, the alliance “recognize[d] that China’s growing influence and international policies present both opportunities and challenges that we need to address together as an Alliance.”110 Issues of concern include Russian and Chinese military cooperation as well as Chinese technology, propaganda, offensive cyber capabilities, and control of critical infrastructure in Europe, all of which affect NATO’s member states. “We are concerned,” NATO noted in its Brussels statement, “by recent public comments by PRC officials and call on China to cease amplifying the Kremlin’s false narratives, in particular on the [Russia-Ukraine] war and on NATO, and to promote a peaceful resolution to the conflict.”111 In an interview, Admiral Burke, noting that Chinese warships and investments are “increasingly present” in the Mediterranean, highlighted the potential risk to U.S. and alliance interests from Chinese infrastructure acquisitions in Europe: The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 79 up yet” and that “[w]e will have to do more to build up the model before we can work out what national commitments can be.”95 In March 2022, the establishment of multinational battle groups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia was announced at an extraordinary NATO summit. The battle group in Bulgaria consists of “Up to 803” Bulgarian troops supplemented by 135 U.S. and 30 Albanian troops.96 The battle group in Hungary consists of 900 troops: 60 Croatian, 130 U.S., and 710 Hungarian.97 The Czech Republic (133 troops) will lead the NATO battle group in Slovakia with contributions from Germany (284); the Netherlands (125); and Slovenia (101). Both the Dutch and German deployments include air defense.98 France (550 troops) is leading the 1,148-strong NATO battalion in Romania, which also includes troops from Belgium (248); Poland (230); and the U.S. (120).99 The French deployment includes armored vehicles and a naval air group for air defense and air surveillance.100 NATO also retains “multinational battalion-size battlegroups” in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. Established as part of NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence in 2017, they are led, respectively, by the U.K., Canada, Germany, and the U.S.101 U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe. In his 2022 EUCOM posture statement, General Wolters reaffirmed that: Today, the Chinese have a controlling interest in 12 European ports. So, are NATO countries going to be able to count on those ports for Free Trade, and if NATO has to defend Europe, will they allow us into those ports to refuel, resupply, do repairs, rearm? We don’t know if we can count on that. It’s a troubling pattern and our European partners are increasingly aware and awakened to this potential threat.112 Important Alliances and Bilateral Relations in Europe The United States has a number of important multilateral and bilateral relationships in Europe. First and foremost is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the world’s most important and arguably most successful defense alliance. North Atlantic Treaty Organization. NATO is an intergovernmental, multilateral security organization that was designed originally to defend Western Europe from the Soviet Union. It anchored the U.S. firmly in Europe, solidified Western resolve during the Cold War, and rallied European support following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. NATO has been the bedrock of transatlantic security cooperation ever since its creation in 1949 and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. In April 2021, following a U.S. decision to withdraw forces from Afghanistan and “recognising that there is no military solution to the challenges Afghanistan faces,” NATO ended Operation Resolute Support, a non-combat operation intended to provide “training, advice and assistance to Afghan security forces and institutions.”113 The withdrawal of alliance forces was completed in August 2021, and the mission was terminated in September 2021. Two ongoing NATO operations are Kosovo Force (KFOR), which includes “approximately 3,500 Allied and partner troops,” and Operation Sea Guardian, which maintains “maritime situational awareness, counter-terrorism at sea and support to capacity-building” in the Mediterranean. Additional operations include air policing “to meet Iceland’s peacetime preparedness needs”; air policing over the Baltics, Albania, Montenegro, Slovenia, and the Benelux countries of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg; and support for the African Union Mission in Somalia through occasional airlifts and sealifts while helping to train and build capacity in the African Standby Force.114 80 Finally, there is NATO Mission Iraq (NMI), a non-combat mission to train and build the capacity of Iraqi Security Forces. In February 2021, following an Iraqi government request in late 2020, NATO defense ministers agreed to increase the size of NMI and expand the scope of training activities beyond the Baghdad region. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated that an incremental increase could raise the number of NATO troops participating in NMI from 500 to around 4,000.115 In recent years, NATO has focused strongly on military mobility and logistics in line with its 2014 Readiness Action Plan (RAP). The RAP was designed to reassure nervous member states and put in motion “longer-term changes to NATO’s forces and command structure so that the Alliance will be better able to react swiftly and decisively to sudden crises.”116 In June 2018, NATO defense ministers agreed to the Four 30s plan to improve the movement of troops in Europe by 2020. “Four 30s” derives from the plan’s objective that NATO should be able to respond to any aggression with “30 troop battalions, 30 squadrons of aircraft, and 30 warships within 30 days.”117 In 2019, according to Secretary General Stoltenberg, “Allies contributed all of the combat forces required for this initiative” and were “now working to build and maintain the level of readiness of these forces and organise them into larger formations.”118 At the 2019 London summit, space was recognized as “the Alliance’s ‘fifth domain’ of operations, alongside land, sea, air and cyberspace.” Subsequently, in October 2020, “NATO Defence Ministers…agreed to the creation of a space centre at NATO’s Allied Air Command in Ramstein, Germany.” The center’s mission “is to help coordinate Allied Space activities, support NATO activities and operations, and help protect Allied Space systems by sharing information about potential threats.” To these ends, it “works closely with the Allies’ national Space agencies and organisations and the NATO Command Structure to fuse data, products and services provided by nations, such as imagery, navigation and early warning.”119 In May 2022, in a historic shift brought about by Russia’s war against Ukraine, Finland and Sweden applied for NATO membership. Secretary General Stoltenberg stated that the alliance would fast-track their applications.120 Each of the existing 30 NATO 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Tirana Airport Zeebrugge (Bruges) Antwerp Gateway Logistics hub Liège airport Port of Varna Port of Burgas Maersk Container Industry (Tinglev) Terminal des Flandres (Dunkirk) Terminal de France (Le Havre) Terminal du Grant Ouest (Nantes) Eurofos Terminal (Marseille) Port of Hamburg Jade-Weser-Port Logistics Center (Wilhelmshaven) Frankfurt-Hahn Airport Schwerin-Parchim Port of Duisburg Piraeus Container Terminal BILK Kombiterminal (Budapest) Vado Reefer Terminal (Genoa) Malta Freeport Terminal (Marsaxlokk) Euromax Terminal (Rotterdam) Gdynia Container Terminal (Gdynia) Port of Sines Port of Constanta Maribor Airport Ljubljana Airport Noatum Container Terminal (Bilbao) Noatum Container Terminal (Valencia) Kumport Sea Terminal (Istanbul) Heathrow Airport Bulgaria Denmark France Germany Greece Hungary Italy Malta Netherlands Poland Portugal Romania Slovenia Spain Turkey U.K. SOURCE: Heritage Foundation research. member states must ratify the accession protocols and are expected to do so. Finland and Sweden’s inclusion in NATO would bring substantial capabilities to the alliance and enhance the security of the Baltic Sea region. Enhanced Forward Presence. Historically, the centerpiece of NATO’s renewed focus on collective Own Airport Port Port Airport Port Port Port Port Port Port Port Port Port Airport Airport Railway Port Railway Port Port Port Port Port Port Airport Airport Port Port Port Airport Majority Albania Belgium Nearly Half Site/Location Less than Half Type ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Country Lease China’s Ownership Stake in European Ports, Airports, and Railways Unknown TABLE 3 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● A heritage.org defense has been the existing four multinational battalions stationed in Poland and the Baltic States as part of the alliance’s Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP). Different countries serve as lead (framework) nations, providing overall coordination and the centerpiece force that is augmented by other contributing nations, for different supported countries. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 81 l l l l The U.S. serves as the framework nation in Orzysz, Poland, near the Suwalki Gap. The U.S.-led battle group consists of 780 American troops augmented by four troops from Croatia, “up to 120” from Romania, and 129 from the United Kingdom.121 In Estonia, the United Kingdom serves as the framework nation, headquartered in Tapa with 993 troops in an armored infantry battalion with main battle tanks and armored fighting vehicles along with “self-propelled artillery and air defence assets, engineers, an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance group and logistic support elements,” in addition to one Icelandic civilian strategic communications specialist, 219 French troops, and 217 Danish troops.122 In Adazi, Latvia, Canada is the framework nation with “Up to 639” troops and armored fighting vehicles augmented by “Up to 21” troops from Albania; “Up to 81” from the Czech Republic; one civilian communications specialist from Iceland; “Up to 250” troops from Italy with short-range air defense and a chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defense unit; 11 from Montenegro; nine from North Macedonia; “up to 177” from Poland with tanks; “up to 152” from Slovakia; 42 from Slovenia; and “Up to 504” from Spain with tanks and armored fighting vehicles.123 In Rukla, Lithuania, Germany serves as the framework nation with 1,031 troops augmented by “Up to 135” from a Czech Republic air defense unit, 270 from the Netherlands, and “Up to 188” from Norway with main battle tanks and infantry fighting vehicles in addition to one public affairs official from Belgium, another from Iceland, and a six-person transportation team from Luxembourg.124 EFP troops are under NATO command and control; a Multinational Division Headquarters Northeast located in Elblag, Poland, which reached full operational capability in December 2018, coordinates the four battalions.125 In February 2017, the Baltic States signed an agreement to facilitate the movement of NATO forces among the countries.126 82 Some EFP host nations have called for additional assets—importantly, enablers to be added to the battalions. In April 2022, Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Gabrielius Landsbergis called for “more armored vehicles, air defense, sea defenses, and the securing of ports and infrastructure in the region.”127 Some contributing nations have begun to deploy new enablers to the region; in Lithuania, for example, Germany now deploys an Ocelot shortrange air defense system.128 NATO also has established eight Force Integration Units located in Sofia, Bulgaria; Tallinn, Estonia; Riga, Latvia; Vilnius, Lithuania; Bydgoszcz, Poland; Bucharest, Romania; Szekesfehervar, Hungary; and Bratislava, Slovakia. These new units “will help facilitate the rapid deployment of Allied forces to the Eastern part of the Alliance, support collective defence planning and assist in coordinating training and exercises.”129 At its July 2016 Warsaw summit, NATO agreed to “develop tailored forward presence in the southeast part of the Alliance territory.” Specifically: Appropriate measures, tailored to the Black Sea region and including the Romanian initiative to establish a multinational framework brigade to help improve integrated training of Allied units under Headquarters Multinational Division Southeast, will contribute to the Alliance’s strengthened deterrence and defence posture, situational awareness, and peacetime demonstration of NATO’s intent to operate without constraint. It will also provide a strong signal of support to regional security. Options for a strengthened NATO air and maritime presence will be assessed.130 The U.S. and Romania jointly organize the biannual Saber Guardian exercise, which is designed to “improve the integration of multinational combat forces” stationed in the region.131 In the 2021 iteration, which took place in Estonia, Bulgaria, and Romania, “more than 13,000 service members from 19 countries [conducted] live fire and air and missile defense operations, plus a large scale medical evacuation.”132 Saber Guardian 21 was one of several exercises linked with DEFENDER-Europe 21, which had a Black Sea regional focus. The purpose of DEFENDER Europe 2022, which was conducted in May, was to “demonstrate U.S. Army Europe 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength territory covering SACEUR’s (Supreme Allied Commander Europe) area of operation has atrophied since the end of the Cold War.”141 Former U.S. Commander of European Command Lieutenant General Ben Hodges has described the importance of military mobility: “We need to think how fast the Russians are moving. We must be able to move as fast or faster than them so that they do not make the mistake of thinking that they could launch an attack of some sort in an area before we could respond.”142 Continued shortfalls in the alliance’s ability to move soldiers and equipment swiftly and efficiently include “limitations of road surface weight capacity, bridges capacity and railway traffic limits” as well as differences in rail gauges and continued legal, procedural, and regulatory slowdowns.143 NATO has focused heavily on overcoming these barriers, working with the European Union, which retains competencies that are critical to improving military mobility, particularly with regard to overcoming legal and regulatory hurdles. In May 2021, NATO Deputy Secretary General Mircea Geoană underscored the importance of continued cooperation with the EU on military mobility, noting that continued improvements are needed in such areas as “regulations for swift border-crossing, close coordination between military forces and civil government bodies, access to necessary transport capabilities, and ensuring that national transport infrastructure is fit for purpose.”144 In April 2022, the alliance established the Defence Innovation Accelerator of the North Atlantic (DIANA). With a $1.1 billion “innovation fund” that will invest in “deep-tech startups” over a 15-year period and working through “more than 10 accelerator sites and over 50 test centers,” DIANA is “tasked to bring innovative civilian and military organizations closer together to develop cutting-edge solutions in the realms of emerging and disruptive technologies.” Among these “emerging and disruptive technologies” are artificial intelligence, autonomy, big-data processing, biotechnology, hypersonic technology, new materials, propulsion, quantum-enabled technologies, and space-related systems.145 Cyber Capabilities. “A secure cyberspace is essential to everything the Alliance does,” according to NATO’s secretary general. “This is why cyber defence is part of NATO’s core task of collective defence. NATO has made clear that a severe cyber attack could lead it to invoke Article 5 of the The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 83 and Africa’s ability to aggregate US-based combat power quickly in Eastern Europe” and to “increase the lethality of the NATO alliance through long-distance fires, build unit readiness in a complex joint, multinational environment and leverage host nation capabilities to increase the command’s operational reach.” The exercise included “3,437 U.S. and 5,193 multi-national service members from 11 Allied and Partner nations.”133 NATO continues air policing missions over Bulgarian and Romanian airspace. In September and October of 2020, six U.S. F-16s took part in a fourweek air policing mission over Bulgaria with Bulgarian air force units and Canadian F-18s flying from Romania.134 In 2021, NATO jets were scrambled 370 times, and 290 of these incidents involved Russian military aircraft (down from 350 in 2020).135 In October 2019, addressing a NATO capability gap in aerial refueling, the Czech Republic, Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Norway jointly procured A330 air-to-air refueling aircraft, to be deployed from 2020–2024. The fifth of nine aircraft ordered was delivered in August 2021.136 Five of the aircraft will operate out of Eindhoven air base in the Netherlands, and three will operate out of Germany’s Cologne–Wahn air base.137 Additionally, in November 2019, NATO announced a $1 billion package to upgrade its Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) planes. The upgrades, which “will provide AWACS with sophisticated new communications and networking capabilities, including upgrades to the NE-3A’s data link and voice communications capabilities, and enhanced Wide-Band Beyond Line-of-Sight airborne networking capability,” will extend the aircrafts’ service life to 2035.138 NATO’s Alliance Ground Surveillance force, which consists of five RQ-4D Phoenix remotely piloted aircraft based out of Sigonella, Italy, along with ground command and control stations, achieved initial operating capability in February 2021.139 In 2018, NATO established two new commands with a combined total of 1,500 personnel: a joint force command for the Atlantic based in Norfolk, Virginia, and a logistics and military mobility command headquartered in Ulm, Germany.140 Logistics has been a significant alliance focus in recent years. An internal alliance assessment in 2017 reportedly concluded that NATO’s “ability to logistically support rapid reinforcement in the much-expanded 84 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength A heritage.org NOTE: Figures are estimates for 2022. Iceland is not listed because it has no military. SOURCE: Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 27, 2022, https://www.nato.int/ nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/2022/6/pdf/220627-defexp-2022-en.pdf (accessed August 3, 2022). In Europe, NATO members closer to Russia and the Middle East spend, in general, more on defense than those further away. Threat Proximity Largely Dictates Military Spending MAP 2 PORTUGAL IRELAND SPAIN U.K. N. MACEDONIA BULGARIA ROMANIA CYPRUS MOLDOVA TURKEY SYRIA IRAQ ARMENIA GEORGIA RUSSIA <1.25% 1.25%–1.74% 1.75%–1.99% 2%+ DEFENSE SPENDING AS PERCENTAGE OF GDP Black Sea UKRAINE BELARUS LATVIA ESTONIA FINLAND LITHUANIA GREECE MONTENEGRO ALBANIA ITALY HUNGARY CROATIA AUSTRIA SLOVAK REP. POLAND CZECH REP. SWEDEN SLOVENIA SWITZERLAND Mediterranean Sea FRANCE GERMANY LUX. BELGIUM NETHERLANDS DENMARK NORWAY Washington Treaty.”146 Ultimately, the decision to invoke Article 5 will be a political decision. As noted, NATO recognized cyberspace as a domain of operations at its 2016 Warsaw summit. Subsequently: l On August 31, 2018, NATO established a Cyberspace Operations Centre (CYOC) in Mons, Belgium, that will include 70 cyber experts when it becomes fully operational in 2023. The CYOC “supports military commanders with situational awareness to inform the Alliance’s operations and missions.”147 and partner countries boost their capabilities in areas such as cyber defence.”152 In November 2021, the Communication and Information Agency “organised a first NATO counter-drone exercise in the Netherlands…to ensure that commercial systems from different NATO nations can work together, interoperably, to counter threats posed by drones.”153 With respect to the likely effects of Chinese 5G technology on the sharing of intelligence in Europe, U.S. officials have said that utilizing Chinese state-controlled companies for next-generation wireless networks would be “nothing short of madIn 2020, NATO published its first cyber doctrine.148 ness.”154 A Chinese presence in European telecommunications networks could decisively compromise In 2021, at the NATO summit in Brussels, “Althe communications integrity of both the military lies endorsed a new Comprehensive Cyber Deand the intelligence community. The Brussels Statefence Policy, which supports NATO’s core tasks ment notes that “NATO and Allies, within their reand overall deterrence and defence posture to spective authority, will maintain and enhance the enhance further the Alliance’s resilience.”149 security of our critical infrastructure, key industries, supply chains, and communication information Through the NATO Industry Cyber Partnership, networks, including 5G.”155 In March 2022, General NATO has also invested in a stronger relationship Wolters testified that: with industry. “This partnership,” as described by NATO, “includes NATO entities, national ComputThe PRC’s efforts to expand 5G networks er Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) and Allies’ throughout Europe via state-backed firms, such industry representatives. Information-sharing, exas Huawei and ZTE, pose significant security ercises, and training and education are just a few risks to the interests and military forces if the examples of areas in which NATO and industry are U.S., Allies, and Partners. These networks place working together.”150 intellectual property, sensitive information, Cooperation within NATO is also facilitated by technology, and private personal information at two other entities. heightened risk of acquisition and exploitation by the Chinese government.156 The NATO Intelligence on Cyberspace Community of Interest was created “to more regularly Many nations have taken decisions in recent exchange information, assessments and best years to restrict Chinese vendors from 5G networks, practices—improving NATO’s ability to prevent but these threat perceptions are not uniform, and and respond to cyber threats.”151 implementation of these decisions will remain crucially important. The impact of the emerging The NATO Communications and Information patchwork approach toward Chinese 5G technoloAgency “is responsible for ensuring NATO has gy on the European operating environment should the secure networks, communications and soft- become clearer in the coming years. ware needed to guarantee peace and stability At the June 2019 NATO summit: for one billion citizens” and “runs the NATO Cyber Security Centre, which defends NATO’s Allies reaffirmed that secure access to space networks around the clock from cyber attacks services, products and capabilities is essential and malicious activity, monitoring, identifyfor the Alliance’s operations, missions and ing and preventing potential threats.” When activities. They agreed that attacks to, from or requested to do so, “the Agency also helps Allies within space present a clear challenge to the l l l The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 85 l and we have infrastructure in place to be able to house all six in Rota, Spain.”161 In June 2022, DOD announced that “the United States is working with the government to increase the number of destroyers stationed at Rota from four to six.”162 security of the Alliance, could be as harmful to modern societies as a conventional attack and could lead to the invocation of the mutual defence clause (Article 5) of the North Atlantic Treaty. To implement space as an operational domain, the Alliance is enhancing its space domain awareness and common understanding of the space environment. To that end, NATO announced plans in 2021 to develop a Strategic Space Situational Awareness System at NATO Headquarters in Brussels. In addition, NATO’s military authorities have accepted an offer from France to establish a NATO Centre of Excellence devoted to space in Toulouse. NATO also agreed on a roadmap for further implementation of NATO’s Space Policy in the upcoming years to guide NATO’s efforts in a number of areas, including science and technology, resilience and exercises. In 2021, space operational activities were integrated into several exercises, including Steadfast Jupiter, Ramstein Ambition and Steadfast Leda. These exercises involved the development and management of space effects and the integration of space products.157 l l l A second Aegis Ashore site in Redzikowo, Poland, that broke ground in May 2016 has faced delays but was commissioned in September 2020. It is supposedly nearing completion, but whether it will begin operations in 2022 remains unclear.163 Ramstein Air Base in Germany hosts the command center.164 The U.K. operates an early warning BMD radar at RAF Fylingdales in England. The U.K. also continues to consider upgrades to its Type 45 Destroyers with BMD-capable missiles.165 In May and June 2021, 10 nations—Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States—took part in the biannual BMD exercise Formidable Shield. Formidable Shield 21 featured 15 ships, 10 aircraft, and 3,300 participants and “[was] Ballistic Missile Defense. NATO’s ballistic designed to improve allied interoperability in a livemissile defense (BMD) achieved initial operational fire joint IAMD [Integrated Air and Missile Defense] capability in July 2016, offering a stronger capability environment, using NATO command and control to defend alliance populations, territory, and forces reporting structures.”166 across the southern portion of Europe from a potenIn January 2017, the Russian embassy in Norway tial ballistic missile attack. For example: threatened that if Norway contributed ships or radar to NATO BMD, Russia “[would] have to react to deAn Aegis Ashore site in Deveselu, Romania, fend our security.”167 Norway operates four Fridtjof became operational in May 2016, and upgrades Nansen–class Aegis-equipped frigates that are not 158 were completed in August 2019. currently BMD-capable.168 A fifth Aegis-equipped frigate, the Helge Ingstad, collided with an oil tanker An AN/TPY-2 forward-based early-warning and sustained so much damage that the government BMD radar is located at Kürecik, Turkey, purdecided to scrap it.169 suant to the U.S. European Phased Adaptive Denmark, which agreed in 2014 to equip at least Approach (EPAA).159 one of its Iver Huitfeldt–class frigates with radar to contribute to NATO BMD, reaffirmed this comBMD-capable U.S. Aegis-equipped ships are mitment in the Defence Agreement 2018–2023.170 forward deployed at Rota, Spain.160 General Russia’s ambassador in Copenhagen responded by Wolters has characterized Rota’s four current publicly threatening Denmark: “I do not believe that destroyers as the “workhorses of deterrence,” Danish people fully understand the consequences adding that “[w]e currently have a set number of what may happen if Denmark joins the Ameriof four and the request is for two additional can-led missile defense system. If Denmark joins, l l l 86 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Quality of Armed Forces in the Region Article 3 of the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty, NATO’s founding document, states that at a minimum, members “will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.”181 Regrettably, only a handful of NATO members are living up to their Article 3 commitments. In 2022, only nine countries will spend the required minimum of 2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on defense: Croatia (2.03 percent); Estonia (2.34 percent); Greece (3.76 percent); Latvia (2.10 percent); Lithuania (2.36 percent); Poland (2.42 percent); the Slovak Republic (2.00); the United Kingdom (2.12 percent); and the United States (3.47 percent). Romania is just below the threshold at 1.99 percent.182 However, NATO defense spending is trending upward overall. According to the NATO Secretary General’s annual report for 2021: In 2021, eight Allies met the guideline of spending 2% of their GDP on defence, up from just three Allies in 2014. The United States accounted for 51% of the Allies’ combined GDP and 69% of combined defence expenditure. Total NATO military spending in 2021 was estimated to exceed USD 1 trillion. Allies also made progress on their pledge to invest 20% or more of defence expenditures in major new capabilities. In 2021, 21 Allies met the NATO-agreed 20% guideline, compared to only seven in 2014, and 20 Allies spent more in real terms on major equipment than they did in 2020.Allies also made progress on their pledge to invest 20% or more of defence expenditures in major new capabilities.183 Danish warships become targets for Russian nuclear missiles.”171 In March 2019, the first of four Dutch De Zeven Provinciën–class frigates received a SMART-L Multi-Mission/Naval (MM/N) D-band long-range radar upgrade that is “capable of BMD mission (surveillance and tracking of ballistic missiles) up to 2000 km while simultaneous[ly] maintaining the air defence capability.”172 All four Dutch frigates will receive the radar upgrade and carry SM-3 surfaceto-air missiles.173 In May 2021, as part of NATO’s Formidable Shield exercise, radar aboard the HNLMS De Zeven Provinciën “was used to eliminate a ballistic missile, marking a first in Europe.”174 In December 2020, the Royal Netherlands and German navies signed an agreement to work jointly to develop a replacement for the Dutch De Zeven Provinciën–class frigate and Germany’s three F124 Sachsen-class frigates.175 Belgian Admiral Jan de Beurme stated in April 2021 that “we are studying the feasibility of integrating ballistic missile defense shooter capabilities into the new frigates.”176 A contract to develop a weapons suite for a joint Belgian and Dutch procurement of two multipurpose frigates apiece was awarded in February 2019, and the vessels are expected to enter service beginning in 2024.177 Spain currently operates four Aegis-equipped F-100 Alvaro de Bazan–class frigates, but they are not yet BMD-capable.178 In April 2019, Spain signed an agreement to procure five F-110 multi-mission frigates, the first of which will likely be deployed in 2026. The Aegis-equipped frigates “will host the first naval solid-state S-band radar for the Spanish Navy.”179 The Italian Navy is procuring seven multi-role offshore patrol vessels (PPAs) that are to be delivered from 2021–2026. The first of two BMD-capable PPAs in full configuration is scheduled for delivery in 2024.180 In 2022, 24 Allies met the NATO-agreed 20 percent guideline, compared to only seven in 2014 and 21 in 2021.184 Germany. Germany has long been an economic powerhouse with mismatched military capabilities, but Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine sparked major changes in the government’s thinking about military power. In 2022, Germany will spend 1.44 percent of GDP on defense and 20.9 percent of its defense budget on equipment, meeting one of two benchmarks.185 In February 2022, Chancellor Olaf Scholz “vow[ed] to anchor a 100 billion (US $113 billion) euro defense fund in the country’s constitution and exceed a NATO-wide annual spending goal.”186 In announcing the policy change, Scholz stated that “[i]t’s clear we need to invest significantly more in the security of our country in order to protect our freedom and our democracy.”187 In February, Germany also sent an additional 380 troops, including “artillery soldiers, reconnaissance specialists, medics [and] nuclear and biological warfare specialists,” to Lithuania where it serves as The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 87 CHART 4 Less than Half of NATO Members Follow Defense Spending Guidelines NATO members are expected to spend at least 2 percent of their GDP on defense, and at least 20 percent of their defense spending is supposed to go to equipment. Only the U.S. and eight other nations do both. DEFENSE SPENDING AS A PERCENTAGE OF GDP, 2022 4% NATO GUIDELINE: 20% 3% U.S. Greece U.K. Poland Lithuania Estonia Latvia Slovak Rep. Croatia 2% NATO GUIDELINE: 2% Netherlands Romania France North Macedonia Bulgaria Montenegro Albania Norway Italy Portugal Germany Denmark Czech Rep. Slovenia Belgium Turkey Canada Spain 1% Hungary Luxembourg 0% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% EQUIPMENT AS A PERCENTAGE OF DEFENSE EXPENDITURES, 2022 NOTE: Figures are estimates for 2022. Iceland is not listed because it has no military. SOURCE: Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 27, 2022, p. 3, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/220627-def-exp-2022-en.pdf (accessed August 3, 2022). A the framework nation for NATO’s EFP battalion.188 These forces joined the 543 German troops already stationed in Rukla.189 In early April, Germany deployed Ozelot short-range self-propelled air defense systems with Stinger missiles.190 Germany also spent $110 million through 2021 to upgrade facilities in Lithuania that include barracks used by the multinational battalion.191 The Luftwaffe has taken part 88 heritage.org in NATO’s Baltic Air Policing 13 times—more than any other nation’s armed forces—most recently out of Šiauliai air base in Lithuania in the summer of 2020 and Ämari Air Base in Estonia from September 2020 to May 2021.192 Germany also maintains 70 troops in Kosovo as part of NATO’s Kosovo Force.193 In March 2022, the Bundestag extended the mandate for Germany’s 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength equipment, manpower shortages, and an outdated and slow procurement structure.204 In March 2022, Germany announced a deal to purchase 35 F-35A fighters “as replacement for the Tornado in the role of nuclear sharing.” The Tornados are to be phased out between 2025 and 2030. The Luftwaffe also announced the purchase of 15 Eurofighter Typhoons “equipped for electronic warfare.”205 Germany has stated that these purchases do not change its commitment to take part in the Future Combat Air System (FCAS). The Luftwaffe is also reportedly moving toward procurement of an anti-ballistic missile system—either the Israeli-produced Arrow 3 system along with corresponding radar installed at three locations in Germany or the U.S.-produced THAAD system—to defend against attacks from Russian Iskander missiles.206 In March 2021, the Ministry of Defence announced plans to upgrade its Patriot missiles to keep them in service until 2030 and to invest in drone technology rather than a next-generation air defense platform.207 Germany operates the largest fleet of heavy transport aircraft in Europe and has taken delivery of 37 of 53 A400M cargo aircraft ordered.208 In May 2018, the U.S. approved the sale of six C-130J Hercules aircraft and three KC-130J tankers to France and Germany, which were planning to create a joint capability.209 A new joint training center for both aircraft in Normandy broke ground in 2021 and is scheduled to begin operations in 2024.210 The aircraft will be based at Évreux, France, where “this binational air transport squadron will have unrestricted exchange of aircraft, air crews, and maintainers, as well as technical and logistical support based on a common pool of spare parts and a common service support contract.”211 Germany announced the end of its P-3C ORION maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) modernization program in June 2020. In July 2021, Germany’s Defense Ministry signed a letter of offer and acceptance to procure five P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft under the U.S. government’s Foreign Military Sales process.212 In September, Boeing signed a contract with the U.S. Navy to produce the five planes at a “total price tag” of $1.6 billion with deliveries to begin in 2024.213 Other planned air force procurements include replacement of the country’s heavy transport helicopter fleet.214 In April 2022, an agreement was struck for the procurement of 140 missiles for Germany’s five The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 89 participation in NATO’s Sea Guardian maritime security operation, for which 210 troops are currently deployed, and approved a one-year extension of Germany’s participation in the United Nations Mission in South Sudan.194 In May, Germany announced the end of its participation in the EU Training Mission Mali (EUTM), where 300 soldiers had served, but indicated a willingness to extend the mandate for the 1,000 German troops taking part in the U.N.’s Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) if “the UN made sure the shortfalls created by the French withdrawal were filled to ensure the safety of German soldiers.”195 In the Middle East, German forces participate in the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) peacekeeping mission, the mandate for which extends through June 2022.196 In January 2022, Germany extended its non-combat training mission in Iraq and its air-to-air refueling, air surveillance radar, and air transport missions in support of the counter-ISIS coalition through the end of October.197 In April 2017, the Bundeswehr established a new cyber command with a staff of approximately 14,500.198 Germany also led NATO’s VJTF in 2019 and will do so again in 2023 with “the earmarked units prioritised for modernisation and upgrades.”199 In June 2022, Germany announced that it would contribute “15,000 soldiers, 65 aeroplanes, 20 navy units, and other formations to the New Force Model,” greatly increasing the size of the NRF.200 Although Germany’s forces have taken on additional roles in recent years, its military continues to suffer serious equipment and readiness issues overall. The Bundeswehr was recently described as “more or less bare” by Chief of the Army Alfons Mais and in an “alarming” state by Defense Commissioner Eva Hoegl.201 Major weapons systems have an operational readiness rate of 77 percent.202 However, despite some improvements such as the 71 percent readiness rate for combat vehicles, less than half of Germany’s Leopard 2 tanks are ready for action, only 35 of 400 Puma infantry fighting vehicles are “fit for war,” less than 30 percent of the Navy’s ships are “fully operational in the sense that all of the ship’s major systems [are] functional and up to high-intensity operations,” and the readiness rate for helicopters is only 40 percent.203 Challenges to the rebuilding of Germany’s military capabilities include a lack of domestic industry capacity, a need to rely on manufacturers for repair and upgrade of Heron TP unmanned aerial vehicles.215 Armed drones have been a contentious political issue for years in Germany, resisted in large part by the Social Democrats. That the decision has now been taken is a significant shift. Germany, France, Italy, and Spain plan to acquire a collective fleet of Eurodrones at an estimated total cost of $7.5 billion. Germany will have seven systems, each of which will include two ground stations and three aircraft.216 Germany continues to work with France on development of the Main Ground Combat System (MGCS), which will replace both nations’ main battle tanks.217 However, other funding priorities reportedly include “air transport capabilities, frigates and landing platform,” along with €20 billion for munitions, and it is not expected that the project will be completed before 2035.218 Germany’s troubled F-125 Baden-Württemberg– class frigate procurement has been completed. In December 2017, the frigate failed sea trials because of “software and hardware defects.”219 It reportedly had “problems with its radar, electronics and the flameproof coating on its fuel tanks,” was “found to list to the starboard,” and lacked sufficiently robust armaments as well as the ability to add them.220 In addition, there are concerns about whether the frigate’s ability to defend against aerial attack is so deficient that the ship is fit only for “stabilization operations,” and the lack of sonar and torpedo tubes makes the ship vulnerable to attack by submarines.221 Germany returned the ship to the shipbuilder following delivery.222 The redesigned Baden-W ürttemberg was belatedly commissioned in June 2019, and Germany took delivery of the fourth and final F-125 in January 2022.223 In January 2020, Germany awarded a $6.7 billion contract to the Dutch Damen Shipyards for the next-generation F-126 frigate.224 Damen is building the frigates “together with its [German] partners Blohm+Voss and Thales,” and the first of four ordered (with the possibility of another two) is to be delivered in 2028.225 In July 2021, Germany and Norway signed an agreement for a joint program to construct six Type 212CD submarines (two for Germany and four for Norway), the first of which are to be delivered to the Norwegian Navy in 2029 with Germany taking delivery of its submarines in 2032 and 2034.226 Germany’s five K130 Corvettes are due to be delivered by 2025, and the first of the class is undergoing sea trials this year.227 90 In addition to procurements, Germany is seeking to improve readiness by having a combat-ready army division by 2025 rather than the originally planned target of 2027. Germany currently does not have a combat-ready division.228 Deployments often strain the military for years. In one example, “the concentration of all available resources in training, personnel, special tools and spare parts” during the 15-month deployment of TIGER combat helicopters to Mali in 2017 and 2018 “halted the process chain in domestic operations to such an extent that this continued to have a significant disruptive impact on materiel readiness in 2020.” Even Germany’s robust contribution to Baltic Air Policing “takes everything it has, often at the expense of training initiatives.”229 The navy is not much better off. Problems with submarines include “long yard periods, difficulties with main batteries and the practice of ‘controlled removal’ from some submarines in order to keep others operational.”230 Reports surfaced in March 2021 that more than 100 German vessels including submarines rely on a Russian navigation system that does not meet NATO standards and that “[d]uring a worst-case cyberattack, navigation data could be hacked and the ship could fully lose operability.”231 And according to one analyst, the six-month deployment of the frigate Bayern to the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, and Pacific theater beginning in August 2021 “came ‘at the price of gutting the fleet,’ with ship maintenance plans and training schedules altered to accommodate the Bayern mission.”232 There is also a shortage of personnel. The number of personnel on active duty in Germany’s army rose from 176,000 in 2016 to 183,695 by the end of 2021. However, “20,412 of the 116,974 military posts above the ranks of junior-ranking personnel were vacant [by the end of 2021]. This is the equivalent of 17.5 per cent.” In addition, “at the end of 2019 the average age was 32.4 (32.9 for career soldiers and temporary-career volunteers, 20.1 for military service volunteers)” and “had risen to 33.1 by the first half of 2021 (33.8 for career soldiers and temporary-career volunteers, 20.7 for military service volunteers).”233 In April 2021, Germany started a year-long “voluntary military service in homeland security” program that mixes combat training with specialist training to prepare 1,000 young Germans per year to deal with pandemics or natural disasters and protect critical infrastructure.234 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength In January 2019, France signed a $2.3 billion agreement with Dassault Aviation for development of the F4 Standard upgrade to the Rafale fighter aircraft. The upgrade includes “a number of new features, the most important of which is an improvement in the aircraft’s connectivity in both national and allied contexts, through software-defined radio, new links, and satellite communications.”243 The 28 Rafales to be delivered in 2025 “will include some F4 functionalities.”244 An additional 30 Rafales at full F4 configuration will be delivered by 2030. It is expected that “[t]he F4 version will significantly improve the 4.5-generation fighter’s stealth capabilities, which although present in earlier versions to some extent failed to compete with fifth-generation combat aircraft.”245 In February 2021, France signed a contract to procure an additional 12 Rafales at the F3R standard by 2025 to replace fighters that had recently been sold to Greece.246 In May 2021, France, Germany, and Spain signed an agreement to develop a flying demonstrator aircraft for the Future Combat Air System, which is to begin entering service in 2040.247 As of March 2022, because of ongoing disputes between defense companies on technology sharing, the program had yet to enter research and development.248 Executives at Dassault, one of the main defense firms working on the program, stated that “development work on FCAS had in effect ground to a halt, with the company taking its engineers off the programme until it was able to agree [on] a way forward with Airbus.”249 Further complicating the picture, France now worries that Germany’s plan to buy the F-35 places the two countries on diverging timelines for the new aircraft.250 In March, France announced that it would upgrade 42 of 67 Tiger MkIII attack helicopters at a cost of $3.06 billion with delivery expected in 2029.251 France established a 220-person Space Command under the Air Force in September 2019 and has committed to investing $4.78 billion in its space capabilities by 2025.252 In January 2021, NATO approved a Center of Excellence for Military Space to be located alongside French Space Command in Toulouse. The first researchers arrived in 2021, and the center is to be fully staffed by 2025.253 France intends to have a “fully capable” system to defend its space assets in place by 2030. “If our satellites are threatened,” Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly has said, “we intend to blind those of our The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 91 France. France has one of NATO’s most capable militaries and retains an independent nuclear deterrent capability. France rejoined NATO’s Integrated Command Structure in 2009 but remains outside the alliance’s nuclear planning group. In 2022, France will spend 1.90 percent of GDP on defense and 28.6 percent of defense spending on equipment, narrowly missing meeting both NATO benchmarks.235 France will spend at least $45.1 billion on defense in 2022, which is about $1.8 billion more than it spent in 2021. Incumbent President Emmanuel Macron has promised further increases, but the scale of those increases remains unclear.236 France’s defense budget for 2022, according to an Armed Forces Ministry spokesman, “reflects the nation’s commitment to increase its defense funds by €1.7 billion year over year since 2019” and “represents a €9 billion increase over the 2017 budget.” All told, the “French government has invested a cumulative €26 billion on defense over the past five years.”237 Following the Cold War, France drew down the capabilities needed for peer-to-peer conflict. Between 1991 and 2021, “the number of battle tanks dropped from 1,349 to 222, the number of fighters from 686 to 254, the number of large surface ships from 41 to 19 and its active-duty manpower from 453,000 to 203,000.” “Today, the French Army is beautiful,” French General Eric Laval has said, “but in a high intensity conflict, would it be able to hold beyond 48 hours? High intensity would imply potentially very tough battles which could last between 72 to 96 hours and which we are not allowed to lose.” Chief of the Army General Pierre Schill has described the current transformation process as the “most important modernization undergone since World War II.”238 Air Force procurements include an upgrade to the aerial refueling and airlift fleet. In February 2020, France received the second of two KC-130J Super Hercules.239 It also has been introducing new A330 MRTT (Multi-Role Tanker Transport) aircraft and as of April 19, 2022, had received six of a dozen ordered.240 France received its 18th A400M Atlas military transport aircraft in April 2021 and plans to have 25 in service by 2025.241 In October 2020, the government announced that the final 10 NH90 Tactical Troop Helicopters on order for delivery in 2025 and 2026 would be upgraded to meet special forces requirements.242 adversaries. We reserve the right and the means to be able to respond: that could imply the use of powerful lasers deployed from our satellites or from patrolling nano-satellites.”254 In March 2021, with German and U.S. space forces also participating, France launched its first military exercise (AsterX) in space “to evaluate its ability to defend its satellites and other defense equipment from an attack.”255 AsterX 2022 took place in February and March with the U.S. participating.256 In 2022, in addition to personnel and infrastructure, “[t]he Air and Space Force will receive a number of anti-drone jammer guns, and the service plans to deploy an experimental counter-UAS laser weapon aboard a warship at sea next year.”257 Army procurements include Kochi HK416 Assault Rifles, more than 50 percent of which had been delivered as of March 2022; 300 ANAFI USA micro-drones; and 364 Serval Armored Vehicles, 108 of which are to be delivered by the end of 2022.258 The Army will receive 50 upgraded Leclerc tanks in 2022 and plans to invest €58 million in the Main Ground Combat System, a next-generation tank that is being developed jointly with Germany.259 One major project is an upgrade to the French sea-based and air-based nuclear deterrent. The nation test-fired the M51.2, the current three-stage, sea-land strategic ballistic missile (without a warhead), in April 2021 as part of a development program for the M51.3, which is expected in 2025.260 France’s sea-based deterrent is provided by four Le Triomphant–class ballistic missile submarines.261 In March, in response to Russian aggression and threats, France reportedly had three of its four ballistic missile submarines at sea at the same time—something that has not happened in decades. Similar messaging was behind the successful test of the ASMP-A air-launched nuclear weapon in March 2022.262 The government launched France’s third-generation ballistic missile submarine program in February 2021. Delivery of the first submarine is planned for 2035 with three additional subs to be delivered every five years thereafter. Armed Forces Minister Parly has described the third-generation submarines in colorful terms as able to “hear better and defend themselves better whilst at the same time being more silent: They will not make more noise than a school of shrimp.”263 Other major naval procurements include $1.09 billion through 2025 for the design phase of a new nuclear-powered aircraft carrier that will deploy 92 30 Future Combat Air Systems and is planned to enter service in 2038.264 The carrier procurement will account for 20 percent of French naval vessel procurement spending during the next decade.265 In December 2021, the U.S. Department of State’s Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) cleared a potential $1.3 billion sale to France of an Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS), an Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG) system, and related equipment for its new carrier, which will incorporate two or three EMALs and relatively new electromagnetic catapult systems. According to the DSCA, “[t]he proposed sale will result in a continuation of interoperability between the United States and France.”266 The Suffren, the first of six new fifth-generation Barracuda-class nuclear-powered attack submarines, was commissioned in November 2020.267 The second vessel, the Duguay-Trouin will be delivered by the end of the year.268 France is procuring five defense and intervention frigates, the first of which is due in 2024 and the second and third due in 2025.269 The Alsace, a FREMM multi-mission frigate delivered in April 2021, and the Lorraine, which underwent sea trials in February and will be delivered by year’s end, will have enhanced air defense capabilities in addition to the focus on anti-submarine warfare that characterizes the six FREMMs that were delivered between 2012 and 2019.270 In November 2020, Armed Forces Minister Parly announced the overhaul of the entire mine countermeasures systems by 2029.271 In the same month, France and the U.K. signed a production contract for the joint Maritime Mine Counter Measure (MMCM) autonomous minehunting system.272 Identical unmanned mine-hunting demonstrators were delivered to France and the U.K. in December 2021 and have begun capability development trials.273 In December 2016, France opened a cyber-operational command.274 The French Military Programming Law for 2019–2025, enacted in the summer of 2018, added “an additional 1.6 billion euros for cyber operations along with 1,500 additional personnel for a total of 4,000 cyber combatants by 2025,” and in January 2019, France issued its “first doctrine for offensive cyber operations.”275 This year, France will spend “€11 million to develop a sovereign combat cloud capability.”276 France, which has NATO’s third-largest number of active-duty personnel,277 withdrew the last of its 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength the EU-led Operation Irini, which has as its chief mission the enforcement of a U.N. arms embargo on Libya.288 Operation Irini organized the April 2021 Le Pérouse naval exercise in the Bay of Bengal, which also included ships from Australia, Japan, India, and the U.S.289 France also conducts occasional freedom-of-navigation operations in the Pacific. In 2021, for example, it sent a nuclear-propelled attack submarine and warship on an eight-month mission to the Indian and Pacific Oceans.290 France is keenly aware of and concerned about Chinese activity in the Pacific. In June 2021, French Admiral Pierre Vandier said that France faced “a logic of suffocation” in the region because of China’s activities: We have a lot of evidence showing a change in posture. Our boats are systematically followed, sometimes forced to maneuver in front of Chinese ships to avoid a collision, in defiance of the rules of freedom of navigation that we defend. Some of our stopovers in countries in the region where we used to pass are canceled at the last moment, without clear explanations.291 The French-led, Abu Dhabi–based Awareness Strait of Hormuz initiative to help patrol the waters near Iran became operational on February 25, 2020. France continues to contribute to the initiative’s military mission, Operation Agenor.292 Operation Sentinelle, launched in January 2015 to protect the country from terrorist attacks, is the largest operational commitment of French forces. Sentinelle and Operation Resilience, launched in March 2020 to help combat the coronavirus,293 together represent a domestic commitment of 13,000 French forces. Frequent deployments, especially in Operation Sentinelle, have placed significant strains on French forces and equipment. According to one analyst: Firstly, the conjunction of Opération Sentinelle and operations Inherent Resolve and Barkhane led to reduced training time for land forces and for pilots of combat aircraft, helicopters and especially transport aircraft, with the training shortfall amounting to nearly one-third of the intended flight hours. These personnel were on active duty and no longer receiving sufficient training. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 93 troops from Afghanistan at the end of 2014, although all of its combat troops had left in 2012. France continues to remain engaged in the fight against the Islamic State, deploying 600 troops in Operation Chammal.278 In February 2022, the Charles de Gaulle Carrier Strike Group undertook a three-month operational deployment to the Mediterranean that included support for Operation Chammal. During the deployment, the CSG took part in “‘tri carrier operations’ with the Italian Navy (Marina Militare)’s Cavour CSG and the U.S. Navy’s Truman CSG” to maintain interoperability and train with new assets like F-35Bs and E-2D Advanced Hawkeye aircraft.279 France’s contributions to NATO deterrence missions in Eastern Europe have included the deployment of approximately 337 soldiers to Estonia as part of NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence.280 France also has deployed 500 troops to Romania “to further increase its contribution to reassurance for the Allies most exposed to Russia’s threatening actions” in Ukraine and has taken part in Baltic Air Policing nine times, most recently flying out of Estonia from March 31 to August 1, 2022, with “four Mirage 2000-5 fighter aircraft and a 100-strong air force detachment.”281 In addition, four Rafale fighters along with air-to-air refuelers fly combat air patrol missions over Poland from bases in France as part of NATO’s “enhanced Vigilance Activities.”282 France, which led NATO’s VJTF in the first half of 2022,283 is preparing for high-intensity warfare with a full-scale divisional exercise Orion for 2023 that could involve up to 10,000 troops in addition to air and naval units.284 On February 17, 2022, President Macron announced that “France will withdraw its [2,400] troops from Mali nine years after it first intervened to drive Islamic extremists from power but intends to maintain a military presence in neighboring West African nations.” France also plans to reduce its Barkhane force in the Sahel region, which includes Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania, and Niger, from 4,300 to 2,500–3,000 troops.285 The French military has more than 1,600 troops stationed in Djibouti, 900 in Côte d’Ivoire, 350 in Gabon, and 400 in Senegal.286 France also has 650 troops stationed in the United Arab Emirates,287 and a 15-year defense agreement between the two countries has been in effect since 2012. In the Mediterranean, French Rear Admiral Jean J. de Muizon is Deputy Operation Commander of Secondly, the equipment was in intensive use and wearing out more quickly, but the budgets allocated for maintenance proved to be insufficient, which meant that equipment-readiness rates fell. Readiness rates were very low for transport and attack helicopters in particular— just over 50% in 2017—and for the armoured vehicles used in the Sahel, only three-quarters of which were serviceable during the same period.294 The United Kingdom. America’s most important bilateral relationship in Europe is its Special Relationship with the United Kingdom. From the sharing of intelligence to the transfer of nuclear technology, a high degree of military cooperation has helped to make this relationship unique. In 2022, the U.K. will spend 2.12 percent of GDP on defense and 28.1 percent of its defense budget on equipment.295 In November 2020, the government announced plans to spend “a projected total of nearly $22 billion” on defense across the next four years “on top of a previous commitment to add $2 billion more to the country’s defense budget, with the combined planned increase being approximately $24.1 billion through 2024.” The new funding will be used in part for acquisitions, including frigates, Type 32 warships, and the U.K.’s Future Combat Air System. The U.K. is also standing up a Space Command and an Artificial Intelligence Center.296 In March 2021, the U.K. released its Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy as well as a Defence Command Paper.297 The Defence Ministry’s Command Paper, which lays out a plan for military modernization, includes plans for “a new Multi-Role Ocean Surveillance capability to safeguard the critical undersea national infrastructure on which our prosperity depends” and a new special operations Army Ranger Regiment that “will be able to operate in complex, high-threat environments, taking on some tasks traditionally done by Special Forces.”298 The paper also specifies significant cuts in capability, including retirement of Mine Counter Measures Vessels, and the early retirement of C-130J transport aircraft.299 The army would be reduced “from the current Full Time Trade Trained strength of 76,000 to 72,500 by 2025”—the smallest it has been since 1714.300 One analysis argues that the Army reduction “is less than might appear” because “the 94 Army has been well below its planned personnel numbers for some years,” but the loss of the C-130J will be felt as “[t]hese aircraft had been particularly favoured for Special Forces roles, which will now fall to the considerably larger A400M Atlas.”301 Additionally: [T]the Army will invest around £1.3bn in our armoured capability by upgrading 148 of our main battle tanks to ensure the Challenger III will become one of the most protected and most lethal in Europe. The remaining fleet will be retired. We will no longer upgrade Warrior but it will remain in service until replaced by Boxer, which we expect to happen by the middle of this decade.302 Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine has raised questions about plans detailed in the Integrated Review: “Among the changes to be implemented was a pivot to the Asia–Pacific region and a transformation of the military towards hi-tech capabilities like space, cyber, and artificial intelligence, away from conventional weapons like main battle tanks.”303 The U.K.’s Defence Equipment Plan 2021–2031 details spending of £238 billion (approximately $310 billion), across 10 years, an increase of 25 percent (£48 billion) from the previous year’s plan.304 Navy Command will receive £38.1 billion; Army Command, £41.3 billion; Air Command, £36.2 billion; Strategic Command, £35.0 billion; the Defence Nuclear Organisation, £58.1 billion; and the combined Strategic and Combat Air Programmes, £21.5 billion.305 According to U.K. Secretary of State Ben Wallace MP: [W]e have also made the significant investments required to address new threats and to ensure that our armed forces remain capable and credible. This includes continuing to deliver the Dreadnought class of submarines to renew the nuclear deterrent, building new ships for the Royal Navy, a major modernisation and upgrade programme for the Army, developing the Future Combat Air System, and investing in space, cyber and digital.306 It remains unclear whether the Ministry of Defence will be able to cover the costs of the proposed equipment plan. The National Audit Office has warned that “in this year’s Plan, risks remain 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength of over-optimistic assumptions about future budgets, costs and the likely achievement of savings targets.” As a consequence, “[t]here is a real risk that, despite the additional funding it has received, the Department’s ambition outstrips the resources available to it.”307 Although the number of its active-duty servicemembers is small in comparison to the militaries of France and Germany, the U.K. maintains European NATO’s most effective armed forces. Nevertheless, the Army admitted in October 2020 that it would miss targets set down in the 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) and that “[a] fully capable division including a new Strike brigade will not be available for fielding until the early 2030s.” By 2025, the Army will “only be able to deploy a combat division consisting of just a single armoured infantry brigade and an interim manoeuvre support brigade.”308 As explained by Ben Barry of the IISS: In early 2021, the Defence Ministry announced that it had been granted observer status for the Franco-German Main Ground Combat System program, which is slated to replace French and German Main Battle Tanks “around 2035.”310 In April 2019, the U.K. reported that it was planning to upgrade only 148 of its 227 remaining Challenger II main battle tanks, cutting its fleet by one-third.311 The 79 other tanks would be scavenged for spare parts.312 Because Challenger tanks are not currently manufactured, sourcing spare parts is a continual problem.313 The British Army had previously cut its tank forces by 40 percent in 2010.314 The Defence Command Paper laid out plans to spend £1.3 billion on upgrades to “148 of our main battle tanks to ensure the Challenger III will become one of the most protected and most lethal in Europe.”315 One former U.K. tank officer recently wrote that the small number of available U.K. tanks means that “our armoured brigades can only play a bit part in someone else’s military in alliance The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 95 The Army was mandated [in the 2015 review] to deliver two armored infantry brigades, whereas they are now saying they can only generate one. They have enough vehicles for three infantry armored brigades, but my very strong suspicion is they haven’t been spending money on spares. If they haven’t got sufficient spare parts they will only risk sending one brigade on operations.309 or coalition.”316 Production of the Challenger IIIs began in March, and initial operating capability is expected in 2027.317 In March 2021, the U.K. announced that it would no longer upgrade its Warrior armored vehicles but that they would remain in service through the mid2020s.318 In 2019, the U.K. signed a £2.8 billion deal to procure around 523 Boxer armored vehicles.319 As a result of the decision to stop upgrading the heavier Warriors, the Army is “conducting an analysis on potential lethality enhancements of Boxer vehicles.”320 The Army announced a purchase of 100 additional Boxers (for a total of 623) in April 2022 with the first units expected to enter service next year.321 As of February 2022, the U.K. had taken delivery of 25 of 48 F-35Bs ordered with delivery of three more expected by the end of 2022.322 Although the total number of F-35s that will be procured may not be known until “the 2025 time frame,” the Defense Command Paper states an ambition to “grow the [F-35] Force, increasing the fleet size beyond the 48 aircraft that we have already ordered.”323 RAF F-35s based at Akrotiri, Cyprus, flew operational sorties for the first time in June 2019.324 In 2019, the U.K. took delivery of the last of 160 Typhoon aircraft, all of which were expected to stay in service until 2040.325 However, in March 2021, the U.K. announced that 24 Tranche 1 Typhoons will be retired by 2025.326 Project Centurion, a $515.83 million Typhoon upgrade to integrate additional Storm Shadow long-range cruise missiles and Brimstone precision attack missiles, was completed in 2018 and enabled the U.K. to retire its fleet of Tornado aircraft.327 The U.K. recently detailed a £2 billion investment over the next four years to develop the Tempest, a sixth-generation fighter to be delivered in 2035, and is partnering with Italy, Japan, and Sweden on the project.328 The RAF operates the largest fleet of air-to-air refuelers in Europe, which is noteworthy because of the severe shortage of this capability on the continent.329 Along with the U.K., the U.S. has produced and jointly operated an intelligence-gathering platform, the RC-135 Rivet Joint aircraft, which has seen service in Mali, Nigeria, and Iraq and is now part of the RAF fleet.330 The U.K. operates seven C-17 cargo planes and has started to bring the European A400M cargo aircraft into service after years of delays. Britain has taken delivery of 20 of 22 A400M heavy transport aircraft ordered, with the final two set for delivery by the end of 2022, and appears to be planning to order additional A400Ms later in this decade.331 The Sentinel R1, an airborne battlefield and ground surveillance aircraft, flew its last operational flight in February 2021.332 In January 2021, the U.K. took delivery of the last of nine P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) that are to be based at RAF Lossiemouth in Scotland.333 In 2018, retired Air Vice-Marshal Andrew Roberts testified to Parliament that “capable though the P-8 may be, the number of aircraft planned is undoubtedly inadequate to fulfil even the highest priority tasks likely to be assigned to the force in tension and hostilities.”334 The U.K. also plans to procure approximately 45 medium helicopters to remain in service until the mid-2040s. This platform will replace four different helicopter platforms currently in service.335 The Royal Navy has lost 40 percent of its fleet since the end of the Cold War.336 Of the 55 ships lost since the early 1980s, half are frigates, and the U.K. now operates only 12.337 Overall: Budget cuts have delayed crucial procurement programmes. The Type 23 frigates and Trafalgar class submarines should have been replaced years ago, and it is becoming increasingly challenging and expensive to maintain aging vessels. The Navy has also taken too long to rectify major problems with vessels. One notable example is the issue with the Type 45 destroyers’ propulsion system: the six vessels are not scheduled to be fixed until 2028, and there are already signs that this target may be slipping. As a result of these failures too many of our high-end warships spend too much of their time unavailable for operations.338 However, as construction of destroyers and frigates picks up steam, “the ambition is to rebuild to more than 20 by the end of the decade.”339 The Royal Navy’s surface fleet is based on the new Type-45 destroyer and the older Type-23 frigate. The latter will be replaced by eight Type-26 Global Combat Ships sometime in the 2020s.340 The Type26 Global Combat Ships are meant to handle a flexible range of tasks; weaponry will include “the Sea Ceptor missile defence system, a 5-inch medium calibre gun, flexible mission bay, Artisan 997 Medium Range Radar, and towed array sonars” as well as “the 96 Future Cruise/Anti-Ship Weapon (FCASW) from 2028.”341 In September 2021, construction began on the first of five T31e frigates, which are scheduled to enter service in 2027.342 One of the U.K.’s oldest Type-23 frigates, HMS Monmouth, was retired early at the end of 2021, and a second, HMS Montrose, is being retired this year. The projected savings of £100 million ($133 million) “will be invested into the development of the follow-on capabilities of the Type 26 anti-submarine warfare frigate and Type 31 general purpose frigate.”343 From May 2021–December 2021, the HMS Queen Elizabeth conducted its first operational deployment that included time in the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian and Pacific Oceans, “working alongside ships from 17 countries and participating in 18 major exercises.”344 The Carrier Strike Group deployment included a U.S. destroyer and a Dutch frigate. The Queen Elizabeth’s embarked F-35s “undertook 1,278 sorties in total during the deployment, with more than 2,200 hours of flying, including 44 combat missions in support of Operation Inherent Resolve against the Islamic State (ISIS) in Iraq and Syria.”345 In November, the Carrier Strike Group took part in interoperability exercises with Italian F-35Bs. According to Commodore Steve Moorhouse, commander of the U.K. Carrier Strike Group, “The fact that US, Italian, and UK F-35Bs are able to fly to and from one another’s decks offers tactical agility and strategic advantage to NATO.”346 The U.K.’s Queen Elizabeth–class carriers are the largest operated in Europe. A second in this class, HMS Prince of Wales, will be the larger of the two carriers and was commissioned in December 2019.347 However, the Prince of Wales has been beset by a series of leaks that have cost £3.3 million to correct and necessitated the cancellation of planned fixed-wing sea trials with F-35s off the U.S. east coast that were scheduled for January 2021.348 The Prince of Wales returned to the sea in May 2021 after five months of repairs.349 Each carrier is capable of supporting 36 F-35s, but the U.K. currently plans to procure only 48.350 In March 2022, the Prince of Wales led NATO’s Maritime High Readiness Force, serving as command ship for Exercise Cold Response, in which 35,000 troops from 28 nations converged in Norway and the surrounding seas through April for cold-weather exercises.351 The Royal Navy is also introducing seven Astute-class attack submarines as it phases out its older Trafalgar-class subs. The fifth Astute-class 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength The Royal Air Force has taken part in Baltic Air Policing six times since 2004, most recently in May– August 2020.362 In March 2022, four RAF Typhoons were deployed to Romania to take part in NATO’s enhanced Air Policing (eAP), the fourth time the RAF has participated in eAP since 2017.363 That same month, the RAF announced that F-35s flying from RAF Marham were taking part in patrols of Polish and Romanian airspace as part of NATO’s Enhanced Vigilance Activity.364 From November–December 2019, four U.K. typhoons and 120 personnel took part in Icelandic Air Policing.365 Before its withdrawal early in 2021, the U.K. maintained a force of 895 troops in Afghanistan as part of NATO’s Resolute Support Mission.366 It also contributes to NATO’s Kosovo Force;367 the Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group One, Standing NATO Maritime Group One, and Standing NATO Maritime Group Two;368 and, as an active part of the anti-ISIS coalition, Operation Shader.369 In February 2021, the U.K. announced that it planned to increase the number of British troops (currently “about 100 soldiers”) engaged in training Iraqi security forces.370 Italy. Italy hosts some of the U.S.’s most important bases in Europe, including the headquarters of the 6th Fleet. It also has NATO’s fifth-largest military371 and one of its more capable despite continued lackluster defense investment. In 2022, Italy will spend 1.54 percent of its GDP on defense and 22.7 percent of its defense budget on equipment, meeting the second NATO spending benchmark.372 Spending in 2021 represented a 9.6 percent or $1.7 billion yearover-year increase from 2020.373 In April, Prime Minister Mario Draghi announced that Italy would attain the 2 percent benchmark in 2028 rather than 2024, “a member of his ruling coalition, the Five Star party, [having] threatened to oppose a pending parliamentary vote on the matter over concerns the cash would be better used on social programs.”374 As indicated in the Defense Ministry’s Multi-year Planning Document 2021–2023, released in August 2021, overall defense spending will decline ”to about 1.23% [of GDP] by 2023 moving further away from the 2% that European NATO countries agreed to aim for at the 2014 NATO summit.”375 Italy spends the alliance’s second-highest total on salaries (60.5 percent of its defense budget), “leaving proportionally less cash for military procurement, training, maintenance and infrastructure.”376 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 97 submarine was launched in April 2021.352 Crucially, the U.K. maintains a fleet of 13 Mine Counter Measure Vessels (MCMVs) that deliver world-leading capability. As a supplement, the U.K. began minehunting and survey operations using unmanned surface vessels (USVs) in March 2020.353 In February 2022, the U.K. ordered a fifth ATLAS Remote Combined Influence Minesweeping System.354 Perhaps the Royal Navy’s most important contribution is its continuous-at-sea, submarine-based nuclear deterrent based on the Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarine and the Trident missile. In July 2016, the House of Commons voted to renew Trident and approved the manufacture of four replacement submarines to carry the missile. The U.K.’s Integrated Review announced plans to raise the ceiling on the nation’s nuclear-warhead stockpile because of “the developing range of technological and doctrinal threats.”355 The U.K. plans to procure four new Dreadnought-class ballistic missile submarines, which are expected to have a 30-year life span, at a cost of £31 billion (plus an additional contingency funding stream of £10 billion for any potential cost overruns) with the first, HMS Dreadnought, to be completed in the early 2030s.356 Construction on a second submarine, HMS Valiant, is ongoing, and construction on the third and fourth, HMS Warspite and HMS King George VI, is in its initial phases. In May 2021, the Ministry of Defence ordered a review of the program because of delays that continue to push back the date of completion.357 Despite these issues, the U.K. remains a leader in NATO, serving as the framework nation for NATO’s EFP in Estonia and a contributing nation for the U.S.-led EFP in Poland with 150 troops.358 In February 2022, the U.K. announced that it was doubling its troop presence in Estonia to more than 1,700 troops along with 48 Warrior Infantry Fighting Vehicles and 24 Challenger II Main Battle Tanks.359 The U.K. also deployed 140 armed forces engineers to Poland in December 2021 “in response to the pressures from irregular migration at the Belarus border” and 350 Marines to Poland in February 2022 to assist “Polish Armed Forces with joint exercises, contingency planning and capacity building in the face of ongoing tensions on the Ukrainian border.” Both deployments are on a bilateral basis.360 In March 2022, the U.K. announced that more than 150 troops would be joining a new NATO multinational battalion in Bulgaria with 150 troops.361 Air Force procurements include (among others) T-345 and T-346 jet trainers; three MC-27J Praetorians “in the special operations configuration” and the EC-27J JEDI (Jamming and Electronic Defense Instrumentation) electronic warfare aircraft, both of which are variants of the C-27J Spartan; loitering munitions; and two KC-767 air-to-air refuelers.377 Italy plans to purchase 60 F-35As for the Air Force and 30 F-35Bs, the F-35Bs to be divided equally between the Air Force and Navy.378 A government-owned plant for final assembly of the F-35 is located in Cameri, Italy. Italy has thus far received 18 aircraft: 14 F-35As and one F-35B for the Air Force and three F-35Bs for the Navy.379 The Air Force will continue funding development of the Eurodrone in conjunction with France, Germany, and Spain and is planning upgrades to its fleet of MQ-9 reaper drones, which Italy may be intending to arm.380 In December 2020, Italy signed the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) Cooperation agreement with Sweden and the U.K. The agreement covers “the cooperation for research, development, and ‘joint-concepting’” of the sixth-generation Tempest fighter.381 According to the planning document, Italy has allocated an initial €2 billion for the program.382 In April 2021, Military Chief of Staff General Enzo Vecciarelli suggested that the Tempest might possibly employ directed energy weapons to defeat hypersonic missiles.383 Key Army procurements include the planned acquisition of 150 Centauro II tank destroyers, with delivery of the first tranche to be completed by the end of 2022; 650 Lince 2 light multi-role vehicles; 156 VBM Freccia 8x8 infantry combat vehicles; and upgrades to the Ariete Main Battle Tank (MBT). The Army plans to upgrade 125 Ariete MBTs, extending their operational timeline to 2040. However, analysts have noted that not enough money has been allocated to upgrade all 125, so either future allocations will be necessary or plans will be scaled down. Because of inadequate funding, other non-priority Army acquisition projects are not likely to come into service until the end of the decade.384 Key naval procurements include plans for four U212A submarines, the first of which is scheduled for delivery in May 2030; “a special operations & diving operations/Submarine Rescue Ship”; and the Teseo Mk2/E anti-ship missile, which is in development.385 Italy launched the last of 10 new FREMM frigates in January 2020 and has funded “two-year 98 feasibility and risk-reduction studies” with a view to replacing two aging destroyers with two 10,000-ton DDX destroyers by 2028.386 Italy’s focus is the Mediterranean region where it participates in a number of stabilization missions including NATO’s Sea Guardian, the EU’s Operation Irini and Operation Atalanta, and the Italian Navy’s own Operation Mare Sicuro (Safe Sea) off the Libyan coast.387 Additionally, “Italy has 400 men, 142 land vehicles and 2 air vehicles in Libya” as part of the bilateral Mission of Assistance of Support in both Misrata and Tripoli.388 Despite a southern focus, Italy contributes to Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group Two, as well as the EFP battalion in Latvia (250 troops) and Operation Prima Parthica (600 troops, partly to help train Iraqi Security Forces), and is leading NATO Mission Iraq in 2022.389 Italian air assets including Tornado jets operating out of the Ahmed Al Jaber air base in Kuwait are performing reconnaissance missions in support of the coalition to defeat the IS.390 With 621 troops, Italy is the second-largest contributor to KFOR after the United States.391 In March 2022, Italy announced that it was sending two mine countermeasures vessels to Romania.392 The Italian Air Force is a strong contributor to Baltic Air Policing and participated in a 15-month mission from September 2020–December 2021. Italian Typhoons first operated out of Lithuania from September 2020–April 2021.393 In April 2021, Italy deployed four F-35As to Estonia, marking the first time the F-35 has taken part in Baltic Air Policing.394 In September 2021, four Italian Typhoons took over flying out of Ämari air base in Estonia until December 1, 2021.395 From December 2021–March 2022, the Air Force took part in NATO’s enhanced Air Policing in Romania with four typhoons and 140 troops.396 Italy previously participated in air policing out of Romania in 2019 and “a four-month enhanced Air Policing deployment to Bulgaria in 2017.”397 The Italian Air Force has deployed to Iceland to perform air patrols six times since 2013, most recently in June–July 2020 when six F-35As were deployed to Iceland.398 Poland. Situated in the center of Europe, Poland shares a border with four NATO allies, a long border with Belarus and Ukraine, and a 144-mile border with Russia’s Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian enclave between Poland and Lithuania on the Baltic 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength defense from 2030 to 2024.411 A law passed by the lower house of Parliament in March 2022 would increase defense spending to 3 percent of GDP in 2023 and increase the size of the armed forces to 300,000, 50,000 of whom would be members of territorial defense units).412 Poland is making major investments in military modernization and is planning to spend $133 billion on new capabilities by 2035 as envisioned in the Defense Ministry’s Technical Modernization Plan for 2021–2035, which was signed in October 2019.413 In addition, several major acquisitions have been announced in recent years. For example: l l l l l l In February 2018, Poland joined an eight-nation “coalition of NATO countries seeking to jointly buy a fleet of maritime surveillance aircraft.”414 In March 2018, in the largest procurement contract in its history, Poland signed a $4.75 billion deal for two Patriot missile batteries, which are scheduled for delivery between 2022 and 2025.415 In February 2019, Poland signed a $414 million deal to purchase 20 high-mobility artillery rocket systems from the U.S. for delivery by 2023.416 Sea. Poland also has a 65-mile border with Lithuania, making it the only NATO member state that borders any of the Baltic States. NATO’s contingency plans for liberating the Baltic States in the event of a Russian invasion reportedly rely heavily on Polish troops and ports.399 Poland is ground zero for supplies and military equipment from Western allies reaching Ukraine. In early March 2022, it was reported that an average of 14 wide-bodied aircraft with matériel and weapons arrive at the Rzeszow airport each day.400 The U.S. reportedly deployed two Patriot missile batteries at the airport, thereby underscoring its importance, in mid-March.401 Poland has an active military force of 114,050 that includes a 58,500-person army with 797 main battle tanks.402 It also has a Territorial Defense Force (TDF) that is intended “to increase the strength of the armed forces and the defense capabilities of the country,” according to former Minister of Defense Antoni Macierewicz, and “is also the best response to the dangers of a hybrid war like the one following Russia’s aggression in Ukraine.”403 The TDF is mostly volunteer; “its personnel combine their civilian careers with limited military service of a minimum of two days twice a month and an annual two-week camp.”404 Its planned 17 brigades will be distributed across the country.405 The force, which will number 53,000 by 2026,406 constitutes the fifth branch of the Polish military, subordinate to the Minister of Defense.407 National Defense Minister Mariusz Blaszczak has stated that the TDF’s performance combating COVID-19 has “impeccably proved their importance and effectiveness.”408 Poland is also investing in cyber capabilities. Its new Cyberspace Defense Force was established in February 2022 with a mission of “defense, reconnaissance and, if need be, offensive actions to protect Poland’s Armed Forces from cyberattacks.”409 In November 2020, the U.S. and Poland signed an enhanced defense cooperation agreement that increased the number of U.S. forces stationed in Poland. The U.S. further expanded its footprint in Poland in 2022 following Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine. In 2022, Poland will spend 2.42 percent of GDP on defense and 20.4 percent of its defense budget on equipment, surpassing both NATO benchmarks.410 Poland’s 2020 National Security Strategy accelerated the timeline for spending 2.5 percent of GDP on In April 2019, it signed a $430 million deal to buy four AW101 helicopters that will provide anti-submarine warfare and search-and-rescue capabilities and are to be delivered by the end of 2022.417 In April 2020, it was announced that Poland had concluded negotiations for the purchase of 60 Javelin Command Launch Units (CLUs) and 180 Javelin anti-tank missiles and that “[a] formal agreement to this effect will be signed soon.”418 In January 2020, Poland signed a $4.6 billion deal to purchase 32 F-35As, with “deliveries from 2026,” to be based at Poland’s Lask Air Base. A group of 24 Polish pilots completed F-35 simulator training in Arizona early in 2021.419 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 99 l l l In April 2021, the U.S. and Poland signed an agreement for Poland to acquire five retrofitted C-130H Hercules transport aircraft (decommissioned by the U.S. in 2017) by 2024, with the first arriving in 2021.420 In July 2021, Poland announced a deal to procure 250 M1A2 Abrams SEPv3 tanks with deliveries beginning by the end of 2022.421 In April, Poland announced that it had “significantly accelerated the delivery of the Narew short-range air defense system” with the first of two fire modules to be delivered in September 2022 and the second to be delivered “on the turn of 2022 and 2023” rather than in 2027 as originally planned.422 Although Poland’s focus is territorial defense, it had 290 troops deployed in Afghanistan as part of NATO’s Resolute Support Mission.423 Poland’s Air Force has taken part in Baltic Air Policing 10 times since 2006, most recently operating four F-16s out of Šiauliai Air Base in Lithuania from December 2021–March 2022.424 From August–October 2021, four Polish F-16s and 140 troops took part in Icelandic Air Policing, marking the first time that Poland has taken part in that mission.425 In 2020, Poland was the lead for NATO’s VJTF, and approximately half of the 6,000 troops in the VJTF’s Spearhead Force were Polish.426 Poland also is part of NATO’s EFP in Latvia and has 247 troops in NATO’s KFOR mission in Kosovo.427 In addition, 150 troops are deployed to Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, and Qatar as part of Operation Inherent Resolve, and 30 are deployed as part of NATO Mission Iraq.428 In April 2021, about 80 Polish soldiers deployed to Turkey as part of a NATO assurance mission to assist Turkey by providing additional maritime patrols over the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.429 Poland also continues to take part in NATO’s tailored forward presence in Bulgaria and Romania with 220 troops.430 Finally, a tank company with 177 troops is deployed to Latvia as part of the NATO EFP battalion in that nation, and Poland reportedly is contributing 100 soldiers to a new NATO EFP battalion in Slovakia.431 Turkey. Turkey remains an important U.S. ally and NATO member. Autocratic President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s efforts to warm relations with 100 Russia have strained U.S.–Turkish bilateral relations, but Russia’s war in Ukraine and Turkey’s support for Ukrainian forces are helping relations move forward on a more positive track. Turkey has been an important U.S. ally since the closing days of World War II. During the Korean War, it deployed 15,000 troops and suffered 721 killed in action and more than 2,000 wounded. Turkey joined NATO in 1952, one of only two NATO members (the other was Norway) that had a land border with the Soviet Union. Today, it continues to play an active role in the alliance, but not without difficulties. Following an attempted coup in July 2016, thousands of academics, teachers, journalists, judges, prosecutors, bureaucrats, and soldiers were fired or arrested. Since 2016, 321,000 people have been detained in Turkey.432 Opposition politicians and civil society leaders continue to be jailed. Turkey has built 131 new prisons since the attempted coup and is thinking of building another 100. In addition, Turkey’s prison population reached 300,000 in 2020, up from 180,000 in 2016, and political dissidents have been barred from being released under COVID-19 amnesties.433 The post-coup crackdown has had an especially negative effect on the military. As of July 2021, 23,364 military personnel had been dismissed, and “[t]he effect on officer morale of these continuing purges,” according to the IISS, has been “exacerbated by the widespread suspicion that promotions and appointments were increasingly politicised, with outspoken supporters of Erdogan fast-tracked for promotion.”434 In April 2021, Turkish authorities detained 10 former admirals who were part of a group of more than 100 retired naval officers that issued an open letter criticizing a government plan to construct a canal in Istanbul.435 Turkey’s military is now suffering from a loss of experienced generals and admirals as well as an acute shortage of pilots. The dismissal of 680 of 1,350 pilots greatly exacerbated existing pilot shortages.436 A third of the dismissed pilots were in the leadership echelon, commanding squadrons, fleets, or bases.437 A request to the U.S. to send trainers was denied, as was a Turkish plan to utilize Pakistani trainers to fly the F-16.438 Furthermore, as one analyst notes, “[t]he shortage of pilots was not the only problem. Many of the veteran staff members, especially at the operations and logistics centers that help pilots fly successful missions, were also removed, hampering 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength In his posture statement to Congress, General Wolters downplayed the lasting potential of the Turkish–Russian rapprochement: Turkey possesses the second largest military in NATO, borders a volatile region, and retains a pivotal role in countering Russia. The Turkish and Russian government’s [sic] relationship remains competitive and transactional, with Turkish engagement often aimed at constraining Russian behavior. Both nations view the Black Sea region within their natural spheres of influence, and each continues to oppose the other in Ukraine, Libya, and Syria. Turkey can best counter Russia through close cooperation with the U.S. and NATO. We laud Turkey’s strong support to Ukraine up to and during Russia’s invasion, and we will continue to find ways to increase our cooperation with Turkey bilaterally and within NATO.452 Turkey has been a key supporter of Ukraine. In addition to $7.4 billion worth of trade with Kyiv in 2021, Turkish Bayraktar TB2 armed drones have proven particularly effective on the battlefield in Ukraine, and Turkey has continued to resupply Ukrainian forces “despite warnings from Moscow.”453 In February, Turkey closed the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits to warships, blocking Russian warships operating in the Mediterranean from entering the Black Sea to join in the assault on Ukraine.454 Turkey remains reliant on Western companies, including for its drones. “While Turkish companies have assembled the drones,” according to the Congressional Research Service, “they apparently rely on Western countries for some key components, including engines, optical sensors, and camera systems.”455 Turkey is also seeking ways to modernize its manned aircraft. In October 2021, Turkey requested to purchase 40 F-16 fighters and 80 modernization kits for its older fleet of F-16s, and in a March 2022 letter to Congress, the State Department found “compelling long-term NATO alliance unity and capability interests, as well as U.S. national security, economic and commercial interests that are supported by appropriate U.S. defense trade ties with Turkey.”456 In May, the Biden Administration asked Congress to approve the sale of electronics, missiles, and radar to Turkey for F-16 upgrades. Following The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 101 the close coordination between the air and land elements of the air force. Hundreds of engineers on the ground were also removed.”439 The dilapidated condition of its air force is partly why Turkey has decided to acquire new groundbased air defense systems.440 In December 2017, Turkey signed a $2.5 billion agreement with Russia to purchase two S-400 air defense systems. Delivery of the first system, consisting of two S-400 batteries and 120 missiles, was completed in September 2019, but delivery of a second system has been delayed by the inability of the two countries to agree on technology transfer and co-production.441 “The decision to purchase two S-400 air-defence systems from Russia,” reports the IISS, “was made by the president without detailed consultation with the armed forces about the possible technical and strategic repercussions.”442 U.S. officials have expressed grave concerns about this purchase and suspended Turkey from the F-35 program in July 2019, stating that “[t]he F-35 cannot coexist with a Russian intelligence collection platform that will be used to learn about its advanced capabilities.”443 Turkey tested the system against its F-16s in November 2019 and further tested the system at Sinop near the Black Sea in October 2020.444 In December, a U.S. official stated that “[w]e object to Turkey’s purchase of the system and are deeply concerned with reports that Turkey is bringing it into operation.”445 That same month, in response to Turkey’s purchase of the S-400 systems, the U.S. announced sanctions that took effect in April 2021.446 Fearful of the effect of these sanctions, Turkey had been stockpiling spare F-16 parts since 2019.447 Turkish defense firms make “more than 800 components…for the F-35 as part of a nine-nation consortium,” and Turkey’s suspension from the program could cost Turkish defense industry as much as $10 billion.448 (The U.S. Government Accountability Office has specified more precisely that 1,005 parts are produced by Turkish firms.449) As of April 2021, it was reported that “the Pentagon [had] hoped to remove all Turkish suppliers from the program by 2020, but it will take until 2022 for all contracts with Turkish companies to come to a close.”450 Both sides have floated proposals to end the dispute, with Turkey suggesting that it “not keep the S-400s operational at all times” and the U.S. suggesting that Turkey transfer its S-400s to Ukraine—a suggestion that Ankara rejected as “quite unrealistic.”451 Turkey’s announcement in June that it was lifting its objections to Finland and Sweden joining NATO, the Administration reiterated its support both for the modernization kits and for the sale of new F-16s to Turkey: “The United States supports Turkey’s modernization of its fighter fleet because that is a contribution to NATO security and therefore American security.”457 Whether the equipment to modernize Turkey’s fleet of F-16s or the purchase of new F-16s materializes remains to be seen, but the Administration’s favorable position undoubtedly reflects a thawing trend because of Turkey’s robust support for Ukraine and support for Finnish and Swedish membership. Absent modernization kits, however, Turkey will have to rely on its own domestic industry to modernize its aging fleet.458 In October 2019, Turkey launched a major offensive in Syria against the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), partly to create a buffer zone near the Turkish border. The largest Kurdish armed faction within the SDF is the People’s Protection Units (YPG), an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated terrorist group that has waged war against Turkey off and on since 1984. The offensive led to the creation of a buffer zone jointly patrolled by Turkish and Russian forces following an agreement between Presidents Erdogan and Putin in Sochi. In February 2020, Russian-backed Syrian regime forces launched an attack on Idlib, the last remaining stronghold of forces opposed to Bashar al-Assad. Turkish forces opposed the offensive and lost 36 soldiers before Turkey and Russia agreed to a cease-fire. The cease-fire was extended in February 2021 and, despite violations by the Syrian Army and rebel factions, has held because of a détente in Syria between Turkey and Russia. Turkish threats to renege on a 2016 agreement with the EU under which the EU paid Turkey to stop the flow of migrants to Europe are a consistent and enduring source of friction (perhaps at least partly because Turkey did in fact renege on the agreement in 2020).459 Turkey and Greece remain at odds over maritime boundaries and drilling rights between their two nations in the eastern Mediterranean in addition to drilling rights off the Cypriot coast and migration.460 Maritime talks between Turkey and Greece are ongoing despite a flare-up of tensions in 2020.461 Turkey is reportedly planning to build a 102 naval base in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and began flying UAVs out of Geçitkale Airport in December 2019.462 Recent upgrades to the base have further heightened tensions.463 In March 2021, Turkey and Qatar signed a deal for Qatari pilots to train in Turkey, leading to speculation that Turkey had “decided to train its fighter pilots on Rafale jets of the Qatar Emiri Air Force (QeAF) so as to counter the Rafale fleet of its adversary, Greece.”464 U.S. security interests in the region lend considerable importance to America’s relationship with Turkey. Turkey is home to Incirlik Air Base, a major U.S. and NATO facility, but it was reported early in 2018 that U.S. combat operations at Incirlik had been significantly reduced and that the U.S. was considering permanent reductions. In January 2018, the U.S. relocated an A-10 squadron from Incirlik to Afghanistan to avoid operational disruptions; these aircraft have since returned to their home base in Missouri following the U.S. withdrawal. Restrictions on the use of Incirlik for operations in Syria have proven problematic. “[The] American operation to kill Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Syria,” for example, “saw U.S. forces use a base in Iraq instead of the much closer Incirlik, requiring a round trip of many hours.”465 The U.S. reportedly began reviewing plans to remove nuclear weapons from Incirlik in 2019, but no such decision has yet been taken. Turkey’s Konya Air Base continues to support NATO AWACS aircraft involved in counter-ISIS operations and Spain’s operation of a Patriot system in the Turkish city of Adana under NATO auspices.466 Turkey also hosts a crucial AN/TPY-2 radar at Kürecik, which is part of NATO’s BMD system with a range of up to 1,800 miles.467 In 2021, Turkey commanded NATO’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force, making investments in their units assigned to the VJTF. “Turkey has made substantial investments into the unit—amongst the most mobile in NATO—particularly in its logistics and ammunition requirements planning,” according to NATO. “The latest models of Turkish armed vehicles, anti-tank missiles and howitzers have been allocated to the force.”468 Early in 2021, Turkey maintained “a 600-strong contingent” in Afghanistan as part of NATO’s Resolute Support Mission.469 The Turks also have contributed to a number of peacekeeping missions in the Balkans, still maintain 316 troops in Kosovo,470 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength and have participated in counterpiracy and counterterrorism missions off the Horn of Africa in addition to deploying planes, frigates, and submarines during the NATO-led operation in Libya. Turkey currently contributes to the Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group Two and Standing NATO Maritime Group Two.471 It has taken part in Baltic Air Policing twice, most recently from May–September 2021 when four F-16s and 80 troops deployed to Malbork, Poland, for the mission.472 In February 2022, Turkey closed the Bosphorus and Dardanelles Straits to warships—a decision that was made even more significant in April when Russia’s Black Sea fleet flagship the Moskva was sunk by Ukrainian forces.473 Turkey’s closure of the Black Sea will prevent Russia from replacing this ship. Turkey has a 355,200-strong active-duty military,474 which is NATO’s second largest after that of the United States. However, in June 2019: assault ships, which officials say will be able to carry 30 to 50 drones.477 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 103 In June 2021, Turkey test-fired its “first domestically produced long-range anti-ship cruise missile.” For many platforms, however, despite some successes, Turkey continues to rely on foreign components, including “US-made engines in the T129 ATAK attack helicopter, German guns for the Altay tank, and German air-independent propulsion systems for its new Reis-class submarines.”478 Turkey’s procurement of 250 new Altay main battle tanks has been delayed for years because of the need to acquire foreign components. The tank had relied on a German-made engine and transmission, as well as French armor, but the technology transfer was not approved. In March 2022, Turkey announced an agreement with two South Korean manufacturers to produce the engine and transmission for the tank.479 Even the Bayraktar drone relies President Recep Tayyip Erdogan ratified a new on “optical/infrared imaging and targeting sensor law that reduced the length of compulsory milsystems” from a Canadian company.480 itary service from 12 to six months. On payment In January 2022, Pakistan cancelled a $1.5 billion of a fee, compulsory service can be reduced deal for 30 T129 ATAK helicopters, which had been further to one month of basic training. The signed in 2018, after years of delays.481 The helicopchanges were expected to reduce the overall ter’s engine is produced by American and British size of the armed forces by around 35%, as part firms, and Turkey has yet to field a domestic replaceof Turkey’s long-term plan to create compact ment. In April 2021, the U.S. granted export licenses and fully professional armed forces.475 for the sale of six T129s to the Philippines; its refusal to issue export licenses for the sale to Pakistan led to Turkey, which in 2022 will spend 1.22 percent the deal’s cancellation.482 In February 2022, Turkey of GDP on defense and 30.8 percent of its defense announced that a Ukrainian-developed engine for its budget on equipment,476 has become increasingly larger T929 helicopter gunship would be produced in self-reliant with respect to its defense capabilities. Turkey. The helicopter is supposed to make its first A particular success has been its Bayraktar drone flight equipped with the new engine in 2023, although program, and the nation is investing further in au- the war could cause the flight to be delayed.483 tonomous systems. Specifically: Additionally, the French government has blocked development of anti-ballistic missiles because of It has begun mass production of the Akıncı, a Turkey’s actions in Syria.484 President Erdogan has larger unmanned combat aircraft with a paypersonally lobbied French President Macron to load of 1.5 tons, and has started sea trials for allow Turkey to purchase the French–Italian EUthe ULAQ, an unmanned surface vessel armed ROSAM consortium’s SAMP/T missile-defense syswith six guided missiles. Four kinds of armed tems.485 In March 2022, France and Italy reportedly unmanned ground vehicles are competing for a agreed to “explore reviving the steps for the SAMP/T Turkish government contract. missile defense system.”486 Having been removed from the F-35 program, Turkey also has plans for a “mobile naval mine” Turkey is purportedly planning to produce a domesthat can be used for surveillance and to attack tic fifth-generation jet, the TF-X National Combat ships, as well as for unmanned fighter jets and Aircraft, with the goal of a prototype by 2023 and strike aircraft to be used on its amphibious the first flight by 2025.487 Another major procurement is for six Type-214 submarines, the first of which was launched in May 2021 and will enter service in 2022 and the last of which is to be delivered in 2027.488 In February 2019, Turkey announced upgrades of four Preveze-class submarines, to take place from 2023–2027.489 According to reports in February 2022, “sea acceptance trials of the early delivered systems and the Critical Design Phase of the Preveze Mid-Life Modernisation Project have been successfully completed.”490 In February 2019, Turkey launched an intelligence-gathering ship, the TCG Ufuk, which President Erdogan has described as the “eyes and ears of Turkey in the seas.”491 In December 2019, Turkey’s Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB) released its Strategic Plan 2019–2023, which sets targets of 75 percent of Turkish military needs being supplied domestically by 2023 and defense exports being increased to $10.2 billion by 2023. Turkey is forecasted to fall short of its indigenous production target of 71 percent in 2023.492 Turkish exports declined by 17 percent to $2.28 billion in 2020, down from $2.74 billion in 2019, but they rebounded in 2021 at more than $3 billion.493 The Baltic States. The U.S. has a long history of championing the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Baltic States that dates back to the interwar period of the 1920s. Since regaining their independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the Baltic States have been staunch supporters of the transatlantic relationship. Although small in absolute terms, the three countries contribute significantly to NATO in relative terms. Estonia. Estonia has been a leader in the Baltics in terms of defense spending. In 2022, it will spend 2.34 percent of GDP on defense and 21.6 percent of its defense budget on new equipment.494 Estonia will increase defense spending by €476 million (US$523 million) in 2022 and plans to spend an estimated €350 million to acquire short-range and medium-range air defense systems by 2025.495 In October 2021, Estonia signed a contract to purchase the Blue Spear 5G coastal shore-to-ship mobile defense system.496 Some of the planned investments in Estonia’s Ministry of Defence Development Plan 2031, released in December 2021, details investments in ammunition stocks along with renovation of Ämari airfield, a modern War and Disaster Medicine Centre in Tartu, “mid-range anti-tank weapons for all 104 infantry brigades,” R-20 Rahe assault rifles, a midrange air surveillance radar, CV-9035 armoured combat vehicle upgrades, and naval mines.497 In February 2022, Estonia announced its largest defense procurement, a $794 million joint Estonia–Latvia purchase of such logistics vehicles as “cranes, loaders and aircraft loaders.”498 Although the Estonian armed forces total only 7,200 active-duty personnel (including the army, navy, and air force),499 they are held in high regard by their NATO partners and punch well above their weight inside the alliance. Between 2003 and 2011, 455 Estonians served in Iraq. Perhaps Estonia’s most impressive deployment has been to Afghanistan: More than 2,000 Estonian troops were deployed between 2003 and 2014, and they sustained the second-highest number of deaths per capita among all 28 NATO members. In 2015, Estonia reintroduced conscription for men ages 18–27, who must serve eight or 11 months before being added to the reserve rolls.500 The number of Estonian conscripts will increase from 3,200 to 4,000 by 2025.501 Estonia has demonstrated that it takes defense and security policy seriously, focusing on improving defensive capabilities at home while maintaining the ability to be a strategic actor abroad. Estonia is acquiring a total of 18 South Korean–built K9 self-propelled howitzers at a total cost of €66 million.502 It received the first units in October 2020, and the remaining units are scheduled to arrive by 2023.503 Estonia has prioritized anti-tank weapons and has sent Ukraine significant numbers of Javelin anti-tank weapons from its own stocks. In October 2020, Estonia withdrew from a joint armored vehicle development program with Latvia and Finland for financial reasons, deferring the acquisition of new armored vehicles until the end of the decade.504 In 2019, it received two C-145A tactical transport aircraft donated by the U.S.505 In July 2019, Estonia signed a $24 million deal to purchase 16,000 rifles from an American arms company, allowing it to phase out older Soviet and Israeli weapons.506 Estonia’s cyber command became operational in August 2018 and is expected to include 300 people when it reaches full operational capability in 2023.507 U.S. and Estonian cyber commands train together. In the fall of 2020, for example, they trained in Estonia to help search for and block incoming cyber threats from Russia.508 Estonia also participated in 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength on equipment, exceeding both NATO benchmarks.518 It also plans to increase defense spending “in 2025 and subsequent years” to “not less than 2.5 percent of the forecasted GDP.”519 In November 2018, Latvia signed a deal for four UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters, to be delivered in 2022. The Michigan National Guard began training Latvian maintainers on the helicopters in December.520 In 2018, Latvia signed a $133 million agreement to purchase Spike precision-guided tactical missiles from Israel, the first of which were delivered in February 2020.521 A new team trainer for the missiles was installed in October 2020.522 Latvia has also expressed interest in procuring a medium-range ground-based air defense system (GBADS). Joint procurements include (with Estonia) logistics vehicles and (with Finland) 200 armored vehicles for Latvian forces, the first two of which were delivered in March 2022 and all of which are to be delivered by 2029.523 Latvia is looking to upgrade temporary fencing along its border with Belarus into permanent fencing to stem the flow of migrants “illegally pushed into Latvia from Belarus.”524 The U.S. continues to aid the Latvian border guard including through delivery of tactical vehicles.525 Lithuania. Lithuania is the largest of the three Baltic States, and its armed forces total 23,000 active-duty troops.526 It reintroduced conscription in 2015 and lowered the age for compulsory service in December 2019.527 Lithuania has shown a steadfast commitment to international peacekeeping and military operations. Between 2003 and 2011, it sent 930 troops to Iraq. From 2002–2021, around 3,000 Lithuanian troops served in Afghanistan, and Lithuania continues to contribute to NATO’s KFOR and NATO Mission Iraq. In 2022, Lithuania will spend 2.36 percent of GDP on defense and 30.5 percent of its defense budget on equipment.528 It also “plans to reach 2.5% [of GDP] by 2030.”529 In April 2019, the U.S. and Lithuania signed a fiveyear “roadmap” defense agreement.530 According to the Pentagon, the agreement will help “to strengthen training, exercises and exchanges” and help Lithuania “to deter and defend against malicious cyber intrusions and attacks.” The two nations also pledged “to support regional integration and procurement of warfighting systems,” including “integrated air and missile defense systems and capabilities to enhance The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 105 U.S. Cyber Command’s CYBER FLAG 21-1 exercise in November 2021.509 In 2017, Estonia and the U.S. strengthened their bilateral relationship by signing a defense cooperation agreement that builds on the NATO–Estonia Status of Forces Agreement, further clarifying the legal framework for U.S. troops in Estonia.510 Estonian forces have participated in a number of operations. These involvements include, for example, 45 soldiers in Resolute Support before its end, a vessel as part of the Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group One, and special forces as part of France’s Task Force Takuba in the Sahel, which began in the latter half of 2020.511 Estonian troops also take part in NATO Mission Iraq and the U.S.-led Operation Inherent Resolve in Iraq.512 In February 2022, Estonia announced the withdrawal from Mali of 95 troops who had been taking part in the French-led Operation Barkhane.513 Latvia. Latvia’s recent military experience has been centered on operations in Iraq and Afghanistan with NATO and U.S. forces. Latvia deployed more than 3,000 troops to Afghanistan and between 2003 and 2008 deployed 1,165 troops to Iraq. It also has contributed to a number of other international peacekeeping and military missions. A recent IISS analysis notes that “Latvia has no requirement and therefore no capacity to independently deploy and sustain forces beyond its national boundaries, although the armed forces have taken part in a range of NATO and EU missions.”514 Nevertheless, despite a military that consists of only 8,750 full-time servicemembers, Latvia deployed troops to NATO’s Resolute Support Mission until the mission’s completion; participates in Operation Inherent Resolve in Iraq, where the mandate for the approximately 30 Latvian soldiers taking part was extended in March 2022 and now runs until February 2024; and has 136 troops deployed in NATO’s KFOR mission.515 Latvia’s State Defence Concept states that “the size of the National Guard must grow to 10,000 troops by 2024 and reach 12,000 troops by 2027.”516 Latvia “is investing $56 million annually through 2022 on military infrastructure, with two-thirds of this amount being spent to upgrade Ādaži military base, headquarters of the Canadian-led EFP battlegroup.”517 In 2022, Latvia will spend 2.10 percent of GDP on defense and 24.6 percent of its defense budget maritime domain awareness.”531 A Mobilisation and Host Nation Support law took effect in January 2021.532 In December 2021, the U.S. and Lithuania signed a Reciprocal Defense Procurement Agreement that U.S. Secretary of Defense Austin stated “will improve conditions for the acquisition of defense items and increase military interoperability.”533 In November 2020, Lithuania signed a $213 million deal to purchase four UH-60M Black Hawk helicopters beginning in late 2024; the U.S. is contributing approximately $30 million to help with the acquisition.534 In October 2020, Lithuania received two Norwegian-made NASAMS mid-range air defense batteries armed with U.S.-made missiles.535 In March 2022, Lithuania announced a $40 million purchase of additional Javelin anti-tank weapons.536 In April 2021, the U.S. donated $10 million worth of M72 Light-Armor Weapons to Lithuania.537 Additional procurements include Boxer Infantry Fighting Vehicles and €145 million for 200 U.S.-made Oshkosh Joint Light Tactical Vehicles (JLTV).538 The first 50 JLTVs were delivered in October 2021 with 50 more to be delivered per year through 2024.539 In January 2022, it was reported that Saab had recently “signed a framework agreement with the Lithuanian Ministry of Defence to provide the country with several Carl-Gustaf M4 recoilless weapons and ammunition” and that Lithuania’s “Defence Materiel Agency has placed a $16.7 million ammunition order as part of the framework agreement.”540 execute a battle rhythm to support decision-makers as well as 24/7 engagement and coordination around the globe with about 40 to 60 people at any given time.”542 EUCOM “executes a full range of multi-domain operations in coordination with Allies and partners to support NATO, deter Russia, assist in the defense of Israel, enable global operations, and counter trans-national threats in order to defend the Homeland forward and fortify Euro-Atlantic security.”543 It is supported by four service component commands (U.S. Naval Forces Europe [NAVEUR]; U.S. Army Europe and Africa [USAREUR-AF]; U.S. Air Forces in Europe [USAFE]; and U.S. Marine Forces Europe [MARFOREUR]) and one subordinate unified command (U.S. Special Operations Command Europe [SOCEUR]). U.S. Naval Forces Europe. NAVEUR is responsible for providing overall command, operational control, and coordination for maritime assets in the EUCOM and Africa Command (AFRICOM) areas of responsibility. This includes more than 20 million square nautical miles of ocean and more than 67 percent of the Earth’s coastline. This command is currently provided by the U.S. 6th Fleet, based in Naples, and brings critical U.S. maritime combat capability to an important region of the world. Some of the more notable U.S. naval bases in Europe include the Naval Air Station in Sigonella, Italy; the Naval Support Activity Base in Souda Bay, Greece; and the Naval Station at Current U.S. Military Presence in Europe Rota, Spain. At its peak in 1953, because of the Soviet threat The USS Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group to Western Europe, the U.S. had approximately deployed to the European theater in 2022 to demon450,000 troops in Europe operating across 1,200 strate the U.S. commitment to NATO. In January, the sites. During the early 1990s, both in response to a CSG took part in NATO exercise Neptune Strike 22 perceived reduction in the threat from Russia and under direct NATO operational control.544 Examples as part of the so-called peace dividend following the of activities during the exercise include (among othend of the Cold War, U.S. troop numbers in Europe ers) “airborne patrols with Allied aircraft through were slashed. Today, the U.S. has fewer than 66,000 a series of missions spanning enhanced vigilance, active-duty forces permanently stationed in Europe. training and NATO enhanced Air Policing (eAP), However, increased rotational forces deployed to supporting the Alliance’s cohesive defence and colEurope to bolster deterrence in eastern NATO mem- lective resolve,” and the refueling of F/A-18E Super ber states have increased total U.S. deployments to Hornets by German Air Force A400M Tankers in around 100,000.541 February and participation by HST squadrons in “a In response to Russia’s second invasion of series of training missions with the Romanian Air Ukraine, EUCOM created Control Center Ukraine Force” in March.545 (ECCU) to coordinate defense assistance to Ukraine. U.S. Army Europe and Africa. In November One official has described ECCU as “a combination 2020, U.S. Army Europe and U.S. Army Africa were of a call center, a watch floor, meeting rooms. They consolidated into U.S. Army Europe and Africa 106 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength (USAREUR-AF), headquartered in Wiesbaden, Germany. According to the Army, “The consolidation of these two Army service component commands under one four-star commander will play a vital role in supporting missions across two interconnected theaters of operation” and will “enhance efficiency by streamlining the headquarters’ ability to execute functions and improving global and regional contingency response efforts.”546 The former USAREUR was established in 1952. Then, as today, the U.S. Army formed the largest portion of U.S. forces in Europe. USAREUR-AF includes “approximately 73,000 U.S. Army personnel assigned and deployed throughout Europe and Africa.” Permanently deployed forces include the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, based in Vilseck, Germany; the 173rd Airborne Brigade in Italy; the 12th Combat Aviation Brigade out of Ansbach, Germany; and the 41st Field Artillery Brigade, with headquarters in Grafenwoehr, Germany. In addition: Reactivated in September 2019, the 1st Battalion, 6th Field Artillery, 41st Field Artillery Brigade is currently the only U.S. rocket artillery brigade in Europe and represents the first time in 13 years that USAREUR has had the Multiple Launch Rocket System in its command; a second field artillery battalion was reactivated in the fall of 2020.548 The 5th Battalion, 4th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, was activated in November 2018 and is now based in Ansbach. 549 The Army announced plans to outfit a complete battalion with the Maneuver-Short-Range Air Defense System (M-SHORAD) by the end of 2022; currently, only a platoon within the 5th Battalion, 4th Air Defense Artillery Regiment is equipped with M-SHORAD.550 Finally, each year, USAREUR-AF takes part in more than 60 exercises with 80,000 multinational participants from 75 countries.551 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 107 Operational and theater enablers such as the 21st Theater Sustainment Command, 10th Army Air and Missile Defense Command, 7th Army Training Command, 79th Theater Sustainment Command, 66th and 207th Military Intelligence Brigades, 2nd Theater Signal Brigade, U.S. Army NATO Brigade, Installation Management Command-Europe and Regional Health Command-Europe provide essential skills and services that support our entire force.547 U.S. Air Forces in Europe. USAFE provides a forward-based air capability that can support a wide range of contingency operations. It originated as the 8th Air Force in 1942 and flew strategic bombing missions over the European continent during World War II. USAFE describes itself as “direct[ing] air operations in a theater spanning three continents, covering more than 19 million square miles, containing 104 independent states, and possessing more than a quarter of the world’s population and more than a quarter of the world’s Gross Domestic Product.”552 Headquartered at Ramstein Air Base, USAFE has seven main operating bases along with 114 geographically separated locations. The main operating bases include the RAF bases at Lakenheath and Mildenhall in the U.K., Ramstein and Spangdahlem Air Bases in Germany, Lajes Field in the Azores, Incirlik Air Base in Turkey, and Aviano Air Base in Italy.553 Terrorist attacks against these installations remain a threat. In March and April 2020, five Tajik nationals who had come to Germany seeking refugee status were arrested for plotting terrorist attacks against U.S. Air Force bases and personnel on behalf of ISIS.554 Strategic bomber deployments continue periodically. In March 2021, U.S. B-1 and B-2 bombers flying from the U.S. deployed out of Orland Air Base in Norway and Lajes Field in Portugal, respectively.555 According to the U.S. Air Force, “[s]trategic bomber deployments to Europe provide theater familiarization for aircrew members and demonstrate U.S. commitment to allies and partners.”556 U.S. Marine Forces Europe. MARFOREUR was established in 1980. It was originally a “designate” component command (only a shell during peacetime but able to bolster its forces during wartime). Its initial staff was 40 personnel based in London. By 1989, it included more than 180 Marines in 45 separate locations in 19 countries throughout the European theater. Today, the command is based in Boeblingen, Germany, and approximately 300 of the more than 1,500 Marines based in Europe are assigned to MARFOREUR.557 It was also dual-hatted as Marine Corps Forces, Africa (MARFORAF), under U.S. Africa Command in 2008. MARFOREUR supports the Norway Air Landed Marine Air Ground Task Force, the Marine Corps’ only land-based prepositioned stock. As of June 2017, the U.S. had enough prepositioned stock in Norway “to equip a fighting force of 4,600 Marines, led by a colonel, with everything but aircraft and desktop computers.”558 The Norwegian government covers half of the costs of the prepositioned storage, and the stock’s proximity to the Arctic region makes it particularly important geostrategically. In March– April 2022, these prepositioned stocks were a factor in the Cold Response 22 exercise, which included 30,000 troops from 27 countries including 3,000 U.S. Marines.559 In the fall of 2021, Special-Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force–Crisis Response–Africa (SPMAGTF–CR–AF), based in Moron, Spain, and created in the wake of the Benghazi embassy attack to respond to crises in the Middle East and North Africa, was shut down.560 Subsequently, Marines have participated in training exercises conducted by AFRICOM’s North and West Africa Response Force.561 U.S. Special Operations Command Europe. SOCEUR is the only subordinate unified command under EUCOM. Its origins are in the Support Operations Command Europe, and it was based initially in Paris. This headquarters provided peacetime planning and operational control of special operations forces during unconventional warfare in EUCOM’s area of responsibility. SOCEUR has been headquartered in Panzer Kaserne near Stuttgart, Germany, since 1967. It also operates out of RAF Mildenhall in the U.K. In 2018, it was announced that the U.S. was planning to relocate tactical United States special operations forces from Stuttgart to Baumholder. The move has yet to occur, but the Administration’s FY 2022 Special Operations budget request included funding to support “three major renovation projects” as part of “the initiative to restation SOF to Baumholder in order to alleviate overcrowding in Stuttgart, Germany.”562 Due to the sensitive nature of special operations, publicly available information is scarce. However, it has been documented that SOCEUR elements participated in various capacity-building missions and civilian evacuation operations in Africa and took an active role in the Balkans in the mid-1990s and in combat operations in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. SOCEUR also plays an important role in joint training with European allies and since June 2014 has maintained an almost continuous presence in the Baltic States and Poland in order to train special operations forces in those countries. A new special operations base in Latvia that opened in December 2020, for example, “includes a vehicle servicing facility, ammunition storage and two helipads for 108 U.S. CV-22 aircraft from the United Kingdom-based 352nd Special Operations Wing,” all of which “are designed to allow special operations forces to move rapidly in and out of the area and conduct maintenance.”563 According to General Wolters: Our Special Operations Forces (SOF) work with European Allies and Partners to build capacity, counter malign activity, and improve resilience. These unique capabilities enable USEUCOM to identify, attribute, and counter Russian malign influence. Furthermore, our Special Operations personnel provide invaluable contributions in sensing the operational environment, enhancing our ability to deter through indications and warnings.564 The FY 2023 DOD EDI budget request includes $26,760,000 in declared special operations funding for “Increased SOF Partnership Activities in Central/Eastern Europe” ($491,000) and “SOF Staging Capabilities and Prepositioning” ($26,269,000).565 Key Infrastructure and Warfighting Capabilities One of the major advantages of having U.S. forces in Europe is access to logistical infrastructure. EUCOM, for example, supports the U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) with its array of air bases and access to ports throughout Europe. One of these bases is Mihail Kogalniceanu Air Base in Romania, which “began as a major refueling and supply route for U.S. troops in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom, as well as a hub to neighboring countries in both EUCOM and CENTCOM,” and from which “[n]ations, allies, and partners…leverage and promote an increasingly interoperable force and posture in coordination to deter further Russian aggression.”566 Europe is a mature and advanced operating environment. Because of its decades-long presence in Europe, the U.S. benefits from tried and tested systems that involve moving large numbers of matériel and personnel into, within, and out of the continent. This offers an operating environment that is second to none in terms of logistical capability. There are more than 166,000 miles of rail line in Europe (not including Russia), an estimated 90 percent of the roads in Europe are paved, and the U.S. enjoys access to a wide array of airfields and ports across the continent. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength U.S. has increased its investment in Europe, and its military position on the continent is stronger than it has been for some time. Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine served to underscore the importance both of continued U.S. reinvestment in Europe and of efforts (which in many cases were already underway) by the U.S. and its allies to improve their defense capabilities. The military, economic, political, and societal impact of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, including China’s support for and enablement of the regime in Moscow, will have to be reckoned with for years to come. Though Russia is experiencing significant battlefield losses, it will be prudent for defense planners to assume that Russia will replace those losses of old equipment with modern, improved items, thereby sustaining the challenge to U.S. and NATO-partner security interests. NATO’s renewed focus on collective defense has resulted in a focus on logistics, newly established commands that reflect a changed geopolitical reality, and a robust set of exercises. NATO’s biggest challenges derive from potential spillover from Ukraine, the need to arm and assist Ukrainian forces while also swiftly backfilling stocks, continued capability and readiness gaps for many European nations, continuing improvements and exercises in the realm of logistics, and the need to establish the ability to mount a robust response to both linear and nonlinear forms of aggression. Scoring the European Operating Environment As noted at the beginning of this section, various 2. Unfavorable. A challenging operating enviconsiderations must be taken into account in assessronment for military operations is marked by ing the regions within which the U.S. may have to inadequate infrastructure, weak alliances, and conduct military operations to defend its vital narecurring political instability. The U.S. military tional interests. Our assessment of the operating enis inadequately placed in the region. vironment utilized a five-point scale, ranging from “very poor” to “excellent” conditions and covering 3. Moderate. A neutral to moderately favorable four regional characteristics of greatest relevance operating environment is characterized by adeto the conduct of military operations: quate infrastructure, a moderate alliance structure, and acceptable levels of regional political 1. Very Poor. Significant hurdles exist for military stability. The U.S. military is adequately placed. operations. Physical infrastructure is insufficient or nonexistent, and the region is political- 4. Favorable. A favorable operating environment ly unstable. The U.S. military is poorly placed or includes good infrastructure, strong alliances, absent, and alliances are nonexistent or diffuse. and a stable political environment. The U.S. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 109 Conclusion Overall, the European region remains a largely stable, mature, and friendly operating environment. Russia remains the preeminent military threat, both conventionally and unconventionally, but Chinese propaganda, influence operations, and investments in key sectors present an additional—and serious— threat. The past year has proven to be an inflection point for transatlantic security with many European allies reinvesting in defense and capabilities. The long-term capacity of allies to sustain a commitment to defense remains to be seen, as does the outcome of the Russia–Ukraine war, which is dramatically reshaping the threat perception in Europe and necessitating operational planning that takes into account what is transpiring on a daily basis. America’s closest and oldest allies are located in Europe, and the region is incredibly important to the U.S. for economic, military, and political reasons. Perhaps most important, the U.S. has treaty obligations through NATO to defend the European members of that alliance. If the U.S. needs to act in or near the European region, there is a history of interoperability with allies and access to key logistical infrastructure that makes the operating environment in Europe more favorable than the environment in other regions in which U.S. forces might have to operate. The past year saw continued U.S. reengagement with the continent, both militarily and politically, along with continued increases in European allies’ defense budgets and capability investments. The military is well placed in the region for future operations. (presumably) achieve successes in critical “first battles” more quickly. Being routinely present in a region also helps the U.S. to maintain familiarity with its characteristics and the various actors that might try to assist or thwart U.S. actions. With this in mind, we assessed whether or not the U.S. military was well positioned in the region. Again, indicators included bases, troop presence, prepositioned equipment, and recent examples of military operations (including training and humanitarian) launched from the region. 5. Excellent. An extremely favorable operating environment includes well-established and well-maintained infrastructure; strong, capable allies; and a stable political environment. The U.S. military is exceptionally well placed to defend U.S. interests. The key regional characteristics consist of: a. Alliances. Alliances are important for interoperability and collective defense, as allies are more likely to lend support to U.S. military operations. Various indicators provide insight into the strength or health of an alliance. These include whether the U.S. trains regularly with countries in the region, has good interoperability with the forces of an ally, and shares intelligence with nations in the region. b. Political Stability. Political stability brings predictability for military planners when considering such things as transit, basing, and overflight rights for U.S. military operations. The overall degree of political stability indicates whether U.S. military actions would be hindered or enabled and considers such questions as whether transfers of power are generally peaceful and whether there have been any recent instances of political instability in the region. c. U.S. Military Positioning. Having military forces based or equipment and supplies staged in a region greatly enhances the ability of the United States to respond to crises and d. Infrastructure. Modern, reliable, and suitable infrastructure is essential to military operations. Airfields, ports, rail lines, canals, and paved roads enable the U.S. to stage, launch operations from, and logistically sustain combat operations. We combined expert knowledge of regions with publicly available information on critical infrastructure to arrive at our overall assessment of this metric. For Europe, scores this year remained steady, with an increase in the Strength of Alliances spurred by the enhanced threat to common interests resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. l Alliances: 5—Excellent l Political Stability: 4—Favorable l U.S. Military Positioning: 4—Favorable l Infrastructure: 4—Favorable Leading to a regional score of: Favorable Operating Environment: Europe VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE FAVORABLE Alliances 110 EXCELLENT % Political Stability % U.S. Military Posture % Infrastructure % OVERALL % 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Endnotes 1. Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine occurred in 2014 when Russia seized and illegally annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and ignited a war in Ukraine’s Donbas region, fought with regular Russian forces and aid to proxies created in the region, so called “Russian backed separatist forces.” Deutsche Welle, “Russian Court Says Country’s Soldiers Stationed in Ukraine,” December 16, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/russian-court-sayscountrys-soldiers-stationed-in-ukraine/a-60153034 (accessed May 26, 2022). 2. John A. Tirpak, “U.S. Military Posture Changes Needed in Europe, Pentagon Says,” Air Force Magazine, April 18, 2022, https://www.airforcemag. com/u-s-military-posture-changes-needed-in-europe-pentagon-says/ (accessed May 26, 2022). 3. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” p. 4, https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/ (accessed July 6, 2022). 4. Ibid., p. 5. 5. Peter Ong, “U.S. Navy Reports on Arctic and North Atlantic,” Naval News, February 20, 2021, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/02/ u-s-navy-reports-on-arctic-and-north-atlantic/ (accessed May 26, 2022). 6. Trisha Thomas, “NATO: Russia Uses Syrian War to Boost Mediterranean Presence,” Associated Press, May 7, 2018, https://apnews.com/ article/391be5ea4450452caa7d84458806b9e9 (accessed May 26, 2022). 7. David A. Wemer, “US Joint Chiefs Chairman Makes the Case for Keeping US Troops in Europe,” Atlantic Council, New Atlanticist Blog, March 21, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/us-joint-chiefs-chairman-makes-the-case-for-keeping-us-troops-in-europe (accessed May 26, 2022). 8. Agence France-Presse, “‘Top Target for Putin’: Residents in Polish Town Worried over US Missile Facility,” March 18, 2022, https://www.firstpost. com/world/top-target-for-putin-residents-in-polish-town-worried-over-us-missile-facility-10469751.html (accessed May 26, 2022). 9. Zachary Basu, “Where 100,000 US Troops Are Stationed in Europe,” Axios, March 22, 2022, https://www.axios.com/2022/03/23/where-100000us-troops-are-stationed-europe (accessed June 16, 2022) . 10. Meghann Myers, “Pentagon Reconsidering Troop Levels in Europe amid Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” Military Times, March 25, 2022, https:// www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2022/03/25/pentagon-reconsidering-troop-levels-in-europe-amid-russias-invasion-ofukraine/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 11. Tirpak, “U.S. Military Posture Changes Needed in Europe, Pentagon Says.” 13. Press release, “Bomber Task Force Europe: Strategic Bombers Soar Through NATO's Eastern Flank, Complete Successful 2-Month Rotation,” U.S. European Command, April 18, 2022, https://www.eucom.mil/pressrelease/42017/bomber-task-force-europe-strategic-bombers-soar-throughnatos-eastern-flank-complete-succe (accessed May 27, 2022). 14. Dan Lamothe, “As Ukraine War Drags on, Pentagon Makes Long-Term Plans for Europe,” The Washington Post, April 5, 2022, https://www. washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/04/05/us-troops-europe-russia-ukraine/ (accessed June 8, 2022). 15. “Senate Armed Services Committee Advance Policy Questions for General Christopher G. Cavoli, USA, Nominee for Appointment to the Position of Commander, United States European Command and Supreme Allied Commander, Europe,” pp. 8–9, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/ imo/media/doc/Cavoli%20APQ%20responses.pdf (accessed July 6, 2022). 16. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Department of Defense Budget Fiscal Year (FY) 2023: European Deterrence Initiative, April 2022, p. 3, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2022/FY2022_EDI_JBook. pdf (accessed June 9, 2022). 17. Ibid., pp. 2, 9, 17, and 17. 18. General Tod D. Wolters, U.S. Air Force, Commander, United States European Command, statement before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, March 29, 2022, pp. 10–11, https://www.eucom.mil/document/42003/sasc-29-mar-2022-eucom-statement-gen-wolterspdf (accessed May 27, 2022). 19. “Contract Awarded for Largest Overseas U.S. Military Hospital,” U.S. Army, January 20, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/253398/contract_ awarded_for_largest_overseas_u_s_military_hospital (accessed June 17, 2022). 20. Phil Stewart, “Military Deploys First Coronavirus Test Kits, Though Capacity Is Limited,” Task & Purpose, March 6, 2020, https://taskandpurpose. com/news/military-deploys-coronavirus-test-kits (accessed May 28, 2022). 21. Fact Sheet, “European Recapitalization Incentive Program (ERIP),” U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, December 6, 2021, https://www.state.gov/european-recapitalization-incentive-program-erip/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 22. Press release, “Ninth Atlantic Resolve Armored Rotation Set to Begin Mission,” U.S. Army Europe and Africa, March 21, 2022, https://www. europeafrica.army.mil/ArticleViewPressRelease/Article/2972096/press-release-ninth-atlantic-resolve-armored-rotation-set-to-begin-mission/ (accessed May 28, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 111 12. C. Todd Lopez, “6 Navy ‘Growler’ Aircraft Headed to Germany to Support Deterrence Mission,” Spangdahlem Air Base, March 28, 2022, https:// www.spangdahlem.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2980758/6-navy-growler-aircraft-headed-to-germany-to-support-deterrence-mission/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 23. Sean Monaghan, Andrew Lohsen, and Pierre Morcos, “Designing New Battlegroups: Advice for NATO Planners,” Center for Strategic and International Studies Commentary, April 15, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/designing-new-battlegroups-advice-nato-planners (accessed May 28, 2022). 24. This was announced early in 2016. See Reuters, “U.S. to Deploy Armored Brigade Combat Teams to Europe,” March 30, 2016, https://www.reuters. com/article/us-usa-military-europe-idUSKCN0WW23P (accessed May 28, 2022). In early 2017, the Army initiated a program to rotate units from CONUS to Europe and back, emphasizing the heel-to-toe aspect, meaning that the replacing unit would arrive before departure of the current unit so as to achieve a constant presence in Europe. The program began in January 2017 with the 10th CAB, followed by the 1st CAB in November 2017 and the 4th CAB in June 2018. See Spc. Thomas Scaggs, “10th Combat Aviation Brigade Returns from Successful Rotation in Europe,” U.S. Army, November 15, 2017, https://www.army.mil/article/196979/10th_combat_aviation_brigade_returns_from_successful_rotation_in_europe (accessed May 28, 2022), and Staff Sgt. Adrian Patoka, “Third Atlantic Resolve Aviation Brigade Arrives in Europe,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 22, 2018, https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1558059/third-atlantic-resolve-aviation-brigade-arrives-in-europe/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 25. U.S. Army Europe and Africa, “Fact Sheet: U.S. Army Europe and Africa Support to Atlantic Resolve,” as of November 8, 2021, https:// www.europeafrica.army.mil/Portals/19/documents/Fact%20Sheets/Atlantic%20Resolve%20Fact%20Sheet%2011082021.pdf?ver=jTsgqzycQIh3TgpPuZg-g%3d%3d (accessed May 28, 2022). 26. Kyle Rempfer, “Air Force MQ-9 Reaper Drones Based in Poland Are Now Fully Operational,” Air Force Times, March 5, 2019, https://www. airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2019/03/05/air-force-mq-9-reaper-drones-based-in-poland-are-now-fully-operational/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 27. David Cenciotti, “US Air Force M-9 Reaper Drones Have Deployed to Estonia for the First Time in History,” Business Insider, July 13, 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/air-force-mq9-reaper-drones-deploy-to-estonia-first-time-2020-7?utm_source=feedburner&amp;utm_ medium=referral (accessed June 16, 2022). 28. Press release, “U.S. Air Force Establishes Enduring Presence in Romania,” U.S. Air Forces in Europe & Air Forces Africa, January 4, 2021, https:// www.usafe.af.mil/News/Press-Releases/Article/2461113/us-air-force-establishes-enduring-presence-in-romania/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 29. Oriana Pawlyk, “With Fewer US Troops in Europe, MQ-9 Reaper Drones Are Filling the Gap,” Military.com, February 26, 2021, https://www.military. com/daily-news/2021/02/26/fewer-us-troops-europe-mq-9-reaper-drones-are-filling-gap.html (accessed May 27, 2022). 30. Brian W. Everstine, “US, Poland Finish Negotiations on Troop Increase, Drones,” Air Force Magazine, August 3, 2020, https://www.airforcemag. com/us-poland-end-negotiations-on-troop-increase-drones/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 31. BBC News, “Pompeo Signs Deal to Redeploy Troops from Germany to Poland,” August 15, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/worldeurope-53792019 (accessed May 28, 2022). 32. Jędrzej Graf and Jakub Palowski, “Defence24 Reveals Details of the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement [EXCLUSIVE],” Defence24.com, August 14, 2020, https://www.defence24.com/defence24-reveals-details-of-the-enhanced-defence-cooperation-agreement-exclusive (accessed May 28, 2022). 33. Pvt. Devin Klecan, “Victory in Europe: V Corps Reaches Major Milestone,” U.S. Army, November 4, 2021, https://www.army.mil/article/251719/ victory_in_europe_v_corps_reaches_major_milestone (accessed May 28, 2022). 34. “Permanent HQ for US Army's V Corps to Be Set up in Poland Says Biden,” The First News, June 29, 2022, https://www.thefirstnews.com/article/ permanent-hq-for-us-armys-v-corps-to-be-set-up-in-poland-says-biden-31386 (accessed July 6, 2022). 35. U.S. Army, V Corps Public Affairs, “Press Release: Victory Corps Deploys Main Headquarters to Europe,” March 3, 2022, https://www.vcorps.army. mil/Newsroom/Articles/Article-Display/Article/2954021/press-release-victory-corps-deploys-main-headquarters-to-europe/ (accessed July 6, 2022). 36. Natalie Liu, “US Visit Highlights Poland’s Rising Military Capabilities,” Voice of America, April 21, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/us-visithighlights-poland-s-rising-military-capabilities-/6538941.html (accessed May 28, 2022), and Shannon Pettypiece, “Biden Travels to Poland as the Country Struggles with Ukrainian Refugee Influx,” NBC News, March 25, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/white-house/biden-polandukraine-refugees-russia-invasion-president-rcna21380 (accessed May 28, 2022). 37. Phil Stewart and Idrees Ali, “U.S. Liaising with Ukrainian Forces in Poland, Pentagon Says,” Reuters, March 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/ world/us-liaising-with-ukrainian-forces-poland-pentagon-says-2022-03-29/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 38. Jim Garamone, “U.S. Troops Train Ukrainians in Germany,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 29, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/NewsStories/Article/Article/3015610/us-troops-train-ukrainians-in-germany/#:~:text=U.S.%20service%20members%20in%20Germany,Kirby%20 said%20today (accessed May 28, 2022). 39. Thomas Nilsen, “U.S. Navy to Build Airport Infrastructure in North Norway to Meet Upped Russian Submarine Presence,” Radio Canada International, Eye on the Arctic, April 16, 2021, https://www.rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2021/04/16/u-s-navy-to-build-airport-infrastructure-innorth-norway-to-meet-upped-russian-submarine-presence/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 40. Reuters, Terje Solsvik, and Nerijus Adomaitis, “Norway to Allow U.S. Military to Build on Its Soil in New Accord,” Reuters, April 16, 2021, https:// www.reuters.com/world/europe/norway-may-allow-us-military-build-its-soil-revised-cooperation-deal-2021-04-16/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 112 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 41. Christopher Woody, “The US Navy Is Going Underground as NATO Increases Its Focus on Its Northern Border with Russia,” Business Insider, October 29, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/us-navy-deploys-hospital-to-norway-caves-amid-russia-tension-2021-10 (accessed May 28, 2022). 42. Diana Stancy Correll, “Navy Sets up Mobile Hospital with 150 Beds in Norwegian Caves,” Navy Times, October 26, 2021, https://www.navytimes. com/news/your-navy/2021/10/26/navy-sets-up-mobile-hospital-with-150-beds-in-norwegian-caves/ (accessed May 28, 2022). NEMSCOM has since been renamed and is now the Naval Medical Readiness Logistical Command (NMRLC). Julius Evans, “NEMSCOM Changes Name and Fleets up, NOSTRA to Be Disestablished,” U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, December 7, 2021, https://www. dvidshub.net/image/7208092/nemscom-changes-name-and-fleets-up-nostra-disestablished (accessed June 9, 2022). 43. Philip Athey, “Marine Corps Announces End to Year-Round Deployment to Norway,” Marine Corps Times, August 13, 2020, https://www. marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2020/08/13/marine-corps-announces-end-to-year-round-deployment-to-norway/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 44. Gina Harkins, “Norway Cancels Big Military Exercise After 1,000 US Marines Arrive in Country,” Military.com, January 27, 2021, https://www. military.com/daily-news/2021/01/27/norway-cancels-big-military-exercise-after-1000-us-marines-arrive-country.html (accessed June 16, 2022). 45. U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Europe and Africa, “Marine Rotational Force-Europe 19.2 & 20.1 Transfer of Authority,” September 27, 2019, https://www. dvidshub.net/news/344810/marine-rotational-force-europe-192-201-transfer-authority (accessed July 6, 2022). 46. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Exercise Cold Response 2022—NATO and Partner Forces Face the Freeze in Norway,” last updated March 25, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_192351.htm?selectedLocale=en (accessed June 17, 2022), and Caleb Larson, “The U.S. Marine Corps Is Keeping an Eye on Russia and Europe,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, March 27, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/usmarine-corps-keeping-eye-russia-and-europe-201483 (accessed June 9, 2022). 47. Brian W. Everstine, “First B-1 Deployment to Norway Shows Importance of Arctic, Cold-Weather Ops,” Air Force Magazine, March 5, 2021, https:// www.airforcemag.com/first-b-1-deployment-to-norway-shows-importance-of-arctic-cold-weather-ops/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 48. Ibid. and Thomas Nilsen, “U.S. B-1 Bomber Makes First Landing Inside Norway’s Arctic Circle,” The Barents Observer, March 9, 2021, https:// thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2021/03/us-b-1-bomber-makes-first-landing-inside-norways-arctic-circle (accessed May 28, 2022). 49. Bruno Waterfield, “Norway Reopens Submarine Base to Help US,” The Times, October 12, 2020, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/norwayreopens-submarine-base-to-help-us-hlmr3wv8s (accessed June 9, 2022). 50. U.S. Army Europe and Africa, “Fact Sheet: U.S. Army Europe and Africa Support to Atlantic Resolve.” 51. U.S. Department of Defense, “Fact Sheet—U.S. Defense Contributions to Europe,” June 29, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/ Release/Article/3078056/fact-sheet-us-defense-contributions-to-europe/ (accessed July 6, 2022). 52. Heritage Foundation research. 53. Idrees Ali, “With an Eye on Russia, U.S. Navy Re-establishing Its Second Fleet,” Reuters, May 4, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usadefense-navy-russia/with-an-eye-on-russia-u-s-navy-re-establishing-its-second-fleet-idUSKBN1I52CJ (accessed May 28, 2022). 54. 13News Now Staff, “US Second Fleet Declares Full Operational Capability,” WVEC, Norfolk, Virginia, updated January 1, 2020, https:// www.13newsnow.com/article/news/national/military-news/us-2nd-fleet-declares-full-operational-capability/291-4dddcb02-5f8d-46c6-8c2c62ba665b017b (accessed May 28, 2022). 55. U.S. 2nd Fleet Public Affairs, “U.S. 2nd Fleet to Lead BALTOPS 2019,” Military News, April 2, 2019, https://www.militarynews.com/news/u-s-2ndfleet-to-lead-baltops-2019/article_00db98bc-557a-11e9-a02b-c718d36bd746.html (accessed May 28, 2022). 56. Paul McLeary, “How the US Is Preparing to Hunt New Chinese, Russian Subs,” Breaking Defense, September 17, 2020, https://breakingdefense. com/2020/09/how-the-us-is-preparing-to-hunt-new-chinese-russian-subs/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 57. Joseph Trevithick, “Three Russian Ballistic Missile Submarines Just Surfaced Through the Arctic Ice Together,” The War Zone, March 26, 2021, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/39953/three-russian-ballistic-missile-submarines-just-surfaced-through-the-arctic-ice-together (accessed May 27, 2022). 58. McLeary, “How the US Is Preparing to Hunt New Chinese, Russian Subs.” 59. Ong, “U.S. Navy Reports on Arctic and North Atlantic.” 60. Ibid. 61. U.S. Sixth Fleet Public Affairs, “USS New Mexico Arrives in Tromsø, Norway,” U.S. Naval Forces Europe–Africa / U.S. Sixth Fleet, May 10, 2021, https://www.c6f.navy.mil/Press-Room/News/Article/2600979/uss-new-mexico-arrives-in-troms-norway/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 62. Wolters, statement before Senate Armed Services Committee, March 29, 2022, p. 8. 63. Joseph Trevithick, “Admiral Warns America’s East Coast Is No Longer a ‘Safe Haven’ Thanks to Russian Subs,” The War Zone, February 4, 2020, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/32087/admiral-warns-americas-east-coast-is-no-longer-a-safe-haven-thanks-to-russian-subs (accessed May 27, 2022). 64. Sam LaGrone, “Updated: Russian Navy Cruisers Positioned to Counter U.S., French and Italian Carrier Groups in the Mediterranean,” U.S. Naval Institute News, updated February 24, 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/02/22/russian-navy-cruisers-positioned-to-counter-u-s-french-anditalian-carrier-groups-in-the-mediterranean (accessed May 27, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 113 65. H I Sutton, “Unusual Russian Navy Concentration Seen in Eastern Mediterranean,” Naval News, February 24, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/ naval-news/2022/02/unusual-russian-navy-concentration-seen-in-eastern-mediterranean/#:~:text=Russia%20has%20reinforced%20its%20 naval,US%20and%20French%20aircraft%20carriers (accessed May 26, 2022). 66. Hope Seck, “The Army Just Activated Its Massive Gear Stockpile in Europe. Here’s What That Means,” Sandboxx, March 4, 2022, https://www. sandboxx.us/blog/the-army-just-activated-its-massive-gear-stockpile-in-europe-heres-what-that-means/#:~:text=Since%202014%2C%20 three%20new%20Army,of%20war%20stocks%3B%20and%20Zutendaal%2C (accessed May 27, 2022). 67. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Department of Defense Budget Fiscal Year (FY) 2023: European Deterrence Initiative, pp. 3 and 13–14. “Navy funding for Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Preparedness in the amount of $3.8 million was not coded as EDI and is not included in this budget overview document.” Ibid., p. 14, note. 68. Ibid., p. 13. 69. Wolters, statement before Senate Armed Services Committee, March 29, 2022, pp. 14–15. 70. News release, “NATO Enhanced Forward Presence Receives First Multinational Ammunition Warehouse,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, March 23, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_193622.htm?selectedLocale=en (accessed May 28, 2022). 71. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg During an Online Conversation with POLITICO Journalist Lili Bayer,” June 22, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_196972.htm (accessed July 6, 2022). 72. Cameron Porter, “Joint Munitions Command Experts Deployed to Europe Provide Vital Support,” U.S. Army, April 18, 2022, https://www.army.mil/ article/255757/joint_munitions_command_experts_deployed_to_europe_provide_vital_support (accessed May 28, 2022). 73. Press statement by Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of State, “$150 Million in Additional U.S. Military Assistance for Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State, May 6, 2022, https://www.state.gov/150-million-in-additional-u-s-military-assistance-for-ukraine/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 74. Terri Moon Cronk, “President Biden Announces New $800M in Military Assistance to Ukraine,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 21, 2022, https:// www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3006622/president-biden-announces-new-800m-in-military-assistance-to-ukraine/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 75. Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III [@SecDef], “United States Security Assistance to Ukraine,” Twitter, April 14, 2022, https://twitter.com/ SecDef/status/1514704710162333697/photo/1 (accessed May 28, 2022). 76. Press release, “EU Support to Ukraine: Council Agrees on Third Tranche of Support Under the European Peace Facility for Total €1.5 billion,” European Union, Council of the European Union, April 13, 2022, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/04/13/eu-support-to-ukrainecouncil-agrees-on-third-tranche-of-support-under-the-european-peace-facility-for-total-1-5-billion/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 77. Beyza Binnur Donmez, “One-Third of Estonia’s Military Budget Donated to Ukraine,” Anadolu Agency [Ankara, Turkey], May 12, 2022, https:// www.aa.com.tr/en/russia-ukraine-war/one-third-of-estonias-military-budget-donated-to-ukraine/2586116#:~:text=Estonia%20has%20 donated%20one%2Dthird,Foreign%20Ministry%20said%20on%20Twitter (accessed May 28, 2022). 78. Philippe Chapleau, “40 Ukrainian Gunners in France from This Weekend to Be Trained on Caesar,” Lignes de défense Blog, April 22, 2022, http:// lignesdedefense.blogs.ouest-france.fr/archives/2022/04/index-3.html (accessed May 28, 2022). 79. Christopher Miller and Paul McLeary, “Heavy Weaponry Pours into Ukraine as Commanders Become More Desperate,” Politico, April 25, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/04/25/ukraine-weaponry-russia-war-00027406 (accessed May 28, 2022). 80. Lee Hudson, Paul McLeary, and Connor O’Brien, “Pentagon Scrambles to Replenish Weapons Stocks Sent to Ukraine,” Politico, March 22, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/03/22/pentagon-scrambles-to-replenish-weapons-stocks-sent-to-ukraine-00019333 (accessed May 28, 2022). 81. Craig Hooper, “Ukraine’s Use of Stinger and Javelin Missiles Is Outstripping U.S. Production,” Forbes, March 8, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/ sites/craighooper/2022/03/08/ukraines-use-of-stinger-and-javelin-missiles-is-outstripping-us-production/?sh=2559e6152409 (accessed May 28, 2022). 82. Hal Brands, “Ukraine War Is Depleting America’s Arsenal of Democracy,” The Washington Post, April 14, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/ business/ukraine-war-is-depleting-americas-arsenal-of-democracy/2022/04/14/4d1b8896-bbfb-11ec-a92d-c763de818c21_story.html (accessed May 28, 2022). 83. Reuters, “Slovakia Gives S-300 Air Defense System to Ukraine, PM Says,” April 8, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/slovakia-gives-s-300-airdefense-system-to-ukraine-pm-says/6520768.html#:~:text=Slovakia%20on%20Friday%20announced%20it,air%20defense%20system%20 to%20Ukraine.&text=Slovakia%20has%20donated%20its%20S,Minister%20Eduard%20Heger%20said%20Friday (accessed June 9, 2022), and Sofia Stuart Leeson, “Dutch Sent Patriot Missile Systems to Slovakia,” Euractiv, April 15, 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_ news/dutch-sent-patriot-missile-systems-to-slovakia/ (accessed June 9, 2022). 84. Reuters, “Britain Examining Anti-Ship Missile Solution for Ukraine,” April 19, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/britain-examininganti-ship-missile-solution-ukraine-2022-04-19/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 85. Reuters, “US Starts Training of Some Ukrainian Troops on Howitzer Artillery,” April 20, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-starts-trainingsome-ukrainian-troops-howitzer-artillery-2022-04-20/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 114 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 86. Andrew Chuter, “Britain Reveals Ukrainian Soldiers Are Training Locally,” Defense News, April 22, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/trainingsim/2022/04/22/britain-reveals-ukrainian-soldiers-are-training-locally/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 87. Agence France-Presse, “Czech Arms Firms to Repair Damaged Ukrainian Tanks,” The Defense Post, April 20, 2022, https://www.thedefensepost. com/2022/04/20/czech-firms-repair-ukraine-tanks/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 88. Liu, “US Visit Highlights Poland’s Rising Military Capabilities.” 89. Ellen Mitchell, “NATO Activates Response Force for First Time in History,” The Hill, February 25, 2022, https://thehill.com/policy/defense/595876nato-activates-response-force-for-first-time-in-history/ (accessed May 28, 2022), and Abraham Mahshie, “NATO Activates Response Force; Austin Calls on Allies to Increase Contributions,” Air Force Magazine, February 25, 2022, https://www.airforcemag.com/nato-activates-responseforce-austin-calls-on-allies-to-increase-contributions/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 90. News release, “SACEUR Statement on the activation of the NATO Response Force,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, February 25, 2022, https://shape.nato.int/news-archive/2022/saceur-statement-on-the-activation-of-the-nato-response-force (accessed May 28, 2022). 91. Phil Stewart, “U.S. Puts 8,500 Troops on Alert to Deploy amid Ukraine Tensions,” Reuters, January 25, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/ us-puts-8500-troops-alert-deploy-amid-ukraine-tensions-2022-01-24/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 92. Steven Chase, “Another 3,400 Canadian Troops Placed on Standby to Deploy to Europe if Necessary, Defence Minister Says,” The Globe and Mail, updated February 25, 2022, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-another-3400-canadian-troops-placed-on-standby-to-deployto-europe-if/ (accessed May 2818, 2022). 93. Paul Belkin, “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: NATO Response,” Congressional Research Service Insight No. IN11866, updated March 21, 2022, p. 1, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11866 (accessed May 28, 2022). 94. Alexandra Ma, “NATO to Boost Rapid-Response Unit from 40,000 to over 300,000 Troops in Apparent Response to Putin’s War,” Business Insider, June 27, 2022, https://www.businessinsider.com/nato-rapid-response-unit-announce-expansion-300k-troops-2022-6 (accessed July 6, 2022), and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg During an Online Conversation with POLITICO Journalist Lili Bayer.” 95. Michael Birnbaum and Emily Rauhala, “Those 300,000 High-Readiness NATO Troops? ‘Concept,’ not Reality,” The Washington Post, June 29, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/06/29/those-300000-high-readiness-nato-troops-concept-not-reality/ (accessed July 6, 2022). 97. Ibid. 98. Ibid. 99. Ibid. 100. SHAPE Public Affairs Office, “France Sends Troops and Equipment to Romania,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, March 8, 2022, https://shape. nato.int/news-archive/2022/france-sends-troops-and-equipment-to-romania (accessed May 28, 2022). 101. News release, “NATO’s Military Presence in the East of the Alliance,” last updated June 1, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/ topics_136388.htm#:~:text=This%20enhanced%20forward%20presence%20was,robust%20and%20combat%2Dready%20forces (accessed June 10, 2022). 102. Wolters, statement before Senate Armed Services Committee, March 29, 2022, p. 14. 103. Joseph Trevithick, “Air Force Shows Off Squadron Logo Highlighting Stockpile of Nuclear Bombs in Belgium,” The War Zone, March 31, 2021, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/40008/air-force-shows-off-squadron-logo-highlighting-stockpile-of-nuclear-bombs-in-belgium (accessed May 27, 2022). 104. Abhijnan Rej, “US Sanctions Turkey over Russian Air Defense System, Raising Questions and Concerns,” The Diplomat, December 16, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/12/us-sanctions-turkey-over-russian-air-defense-system-raising-questions-and-concerns/ (accessed May 28, 2022). 105. Trevithick, “Air Force Shows Off Squadron Logo Highlighting Stockpile of Nuclear Bombs in Belgium.” 106. U.S. Department of Energy, National Nuclear Security Administration, “B61-12 Life Extension Program,” November 2021, https://www.energy.gov/ sites/default/files/2021-12/B61-12%20Fact%20Sheet%20December%202021.pdf (accessed May 29, 2022). 107. Oriana Pawlyk, “Air Force Advances Testing of New Nuclear Gravity Bomb: General,” Military.com, May 1, 2018, https://www.military.com/ dodbuzz/2018/05/01/air-force-advances-testing-new-nuclear-gravity-bomb-general.html (accessed May 27, 2022). 108. News release, “KCNSC Celebrates Completion of ‘B61-12 Life Extension Program’ First Production Unit,” U.S. Department of Energy, Kansas City National Security Campus, February 1, 2022, https://kcnsc.doe.gov/news/news-article/2022/02/01/kcnsc-celebrates-completion-of-b61-12-lifeextension-programfirst-production-unit (accessed May 27, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 115 96. Factsheet, “NATO’s Forward Presence,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/2022/6/pdf/2206-factsheet_efp_en.pdf?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=natopress&utm_campaign=20220628_bg (accessed July 6, 2022). 109. Thomas Newdick, “F-35A Completes Final Inert Drop Test of New B61-12 Nuclear Bomb,” The War Zone, October 5, 2021, https://www.thedrive. com/the-war-zone/42639/f-35a-completes-final-drop-test-of-new-b61-12-nuclear-bomb (accessed May 27, 2022). 110. Press release, “London Declaration Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in London 3–4 December 2019,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, December 4, 2019, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_171584. htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 111. Press release, “Statement by NATO Heads of State and Government,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, March 24, 2022, https://www.nato.int/ cps/en/natohq/official_texts_193719.htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 112. Ong, “U.S. Navy Reports on Arctic and North Atlantic.” 113. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan (2015–2021),” last updated May 30, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/ en/natohq/topics_113694.htm (accessed June 4, 2022). 114. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Operations and Missions: Past and Present,” last updated June 8, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/ natolive/topics_52060.htm (accessed June 10, 2022), and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Air Command, “Icelandic Air Policing,” https://ac.nato.int/missions/air-policing/iceland (accessed June 10, 2022). 115. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Relations with Iraq,” last updated June 1, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_88247.htm (accessed May 29, 2022), and France 24, “NATO to Expand Iraq Mission to Around 4,000 Personnel,” February 18, 2021, https://www.france24. com/en/europe/20210218-nato-to-expand-iraq-mission-to-around-4-000-personnel (accessed May 29, 2022). 116. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Readiness Action Plan,” last updated July 15, 2021, http://www.nato.int/cps/on/natohq/topics_119353.htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 117. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “NATO Agrees to ‘Four 30s’ Plan to Counter Russia,” updated June 7, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/natoministers-expected-to-okay-four-thirties-initiative-stoltenberg/29275979.html (accessed May 29, 2022). 118. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2019, p. 16, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/2020/3/pdf_publications/sgar19-en.pdf (accessed May 29, 2022). 119. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “NATO Space Centre,” https://shape.nato.int/about/aco-capabilities2/nato-space-centre (accessed May 29, 2022). 120. Bruno Waterfield, “Nato Fast-Tracks Membership of Finland and Sweden to Minimise Threat from Russia,” The Sunday Times, May 15, 2022, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/nato-fast-tracks-membership-of-finland-and-sweden-to-minimise-threat-from-russia-7zs86sbn5 (accessed May 29, 2022). 121. Factsheet, “NATO’s Forward Presence.” 122. Ibid. 123. Ibid. 124. Ibid. 125. Mariusz Błaszczak, “Poland’s Defense Minister: Making the Constant Effort to Strengthen Defense,” Defense News, December 9, 2018, https:// www.defensenews.com/outlook/2018/12/10/polands-defense-minister-making-the-constant-effort-to-strengthen-defense/ (accessed May 29, 2022), and news release, “Landcom Soldiers in Elbląg,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Multinational Division North East, February 22, 2018, https://mndne.wp.mil.pl/en/articlesnews-u/2018-02-226-landcom-soldiers-in-elblag/ (accessed May 29, 2022). 126. Baltic News Service, “Baltic Countries Sign Agreement on Fast Movement of NATO Forces,” Latvian Information Agency, February 15, 2017, http:// www.leta.lv/eng/defence_matters_eng/defence_matters_eng/news/CEB6CED4-EA2D-404C-8814-A8765D6BA915/ (accessed May 29, 2022). 127. Deutsche Welle, “Germany's Baerbock calls for stronger NATO strategy in Baltics,” April 22, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-baerbockcalls-for-stronger-nato-strategy-in-baltics/a-61557467 (accessed May 29, 2022). 128. Ibid. 129. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO Force Integration Units (NFIU), “NATO Force Integration Unit (NFIU) Fact Sheet,” https://jfcbs.nato.int/ page5725819/nato-force-integration-units/nato-force-integration-units-fact-sheet (accessed May 29, 2022). 130. Press release, “Warsaw Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw 8–9 July 2016,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, July 9, 2016, last updated March 29, 2017, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/ natohq/official_texts_133169.htm (accessed May 30, 2022). See also North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “NATO’s Military Presence in the East of the Alliance.” 131. Capt. Brian Anderson, “Michigan Units Dash Hopes at Saber Guardian 19,” U.S. Army, June 20, 2019, https://www.army.mil/article/223457/ michigan_units_dash_hopes_at_saber_guardian_19 (accessed June 30, 2021). 132. U.S. Army Europe and Africa, “Press Release—DEFENDER-Europe 21 Activities Begin This Month, Include Two Dozen Nations,” March 15, 2021, https://www.europeafrica.army.mil/ArticleViewPressRelease/Article/2537359/press-release-defender-europe-21-activities-begin-this-monthinclude-two-dozen/ (accessed May 29, 2022). 116 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 133. U.S. European Command, “DEFENDER-Europe 22 Fact Sheet,” as of May 3, 2022, https://www.europeafrica.army.mil/Portals/19/documents/ Infographics/DE22%20Factsheet%20.pdf?ver=Sz9mrh0GxIMTAd1i--z0OQ%3d%3d (accessed May 29, 2022). 134. News release, “U.S. F-16 Begin [sic] NATO Air Policing Mission with Bulgarian Air Force,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, September 28, 2020, https://ac.nato.int/archive/2020/US_eAP_BGR (accessed May 29, 2022). 135. Deutsche Welle, “NATO Scrambled Jets 290 Times Due to Russian Planes in 2021,” December 28, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/nato-scrambledjets-290-times-due-to-russian-planes-in-2021/a-60271618 (accessed May 29, 2022). 136. News release, “Multinational MRTT Fleet Continues to Grow,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO Support and Procurement Agency, August 31, 2021, https://www.nspa.nato.int/news/2021/multinational-mrtt-fleet-continues-to-grow (accessed May 29, 2022). 137. Gareth Jennings, “Czech Republic Joins EU/NATO MMF Tanker Group,” Janes, October 24, 2019, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/newsdetail/czech-republic-joins-eunato-mmf-tanker-group (accessed May 27, 2022). 138. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “AWACS: NATO’s ‘Eyes in the Sky,’” last updated March 3, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/ topics_48904.htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 139. News release, “NATO Alliance Ground Surveillance Force Achieves Initial Operational Capability,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, February 15, 2021, https://shape.nato.int/news-archive/2021/nato-alliance-ground-surveillance-forceachieves-initial-operational-capability (accessed May 29, 2022). 140. Jim Garamone, “NATO Approves Norfolk Joint Force Command, Defense Readiness Initiative,” U.S. Army, June 8, 2018, https://www.army.mil/ article/206683/nato_approves_norfolk_joint_force_command_defense_readiness_initiative (accessed May 29, 2022); news release, “NATO Defence Ministers Take Decisions to Strengthen the Alliance,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, February 15, 2018, https://www.nato.int/cps/ ua/natohq/news_152125.htm (accessed May 29, 2022); and Reuters, “Germany Chooses Ulm for New Proposed NATO Logistics Command,” March 20, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-germany/germany-chooses-ulm-for-new-proposed-nato-logistics-commandidUSKBN1GW1QM (accessed May 29, 2022). 141. Christopher Woody, “A Convoy of US Army Howitzers Got Stopped by German Police, and It Points to a Major Problem NATO Has in Europe,” Business Insider, January 12, 2018, http://www.businessinsider.com/us-army-howitzers-stopped-in-germany-nato-logistics-problems-2018-1 (accessed May 29, 2022). 142. Octavian Manea, “A Tour of Horizon Interview with Lieutenant General Ben Hodges on NATO Adaption and the Russian Way of War,” Small Wars Journal, August 7, 2018, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/small-wars-journal-interview-lieutenant-general-ben-hodges-nato-adaptationand-russian-way (accessed May 29, 2022). 143. Maciej Szopa, “Military Mobility—A Key in Defending the NATO Eastern Flank,” Defence24.com, March 31, 2020, https://www.defence24.com/ military-mobility-a-key-in-defending-the-nato-eastern-flank (accessed May 29, 2022). 144. News release, “Deputy Secretary General Discusses NATO–EU Cooperation at Military Mobility Symposium,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, last updated May 7, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_183464.htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 145. Vivienne Machi, “NATO Unveils Tech Accelerator Footprint, with Plans for over 60 Sites,” Defense News, April 6, 2022, https://www.defensenews. com/global/europe/2022/04/06/nato-unveils-tech-accelerator-footprint-with-plans-for-over-60-sites/ (accessed May 29, 2022). 146. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2020, p. 23, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/2021/3/pdf/sgar20-en.pdf (accessed May 29, 2022). Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty states that an attack on one or more NATO member states will be considered an attack on all NATO member states. The North Atlantic Treaty, Article 5, April 4, 1949, last updated April 10, 2019, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/SID-857936BB-66246E10/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 147. Robin Emmott, “NATO Cyber Command to Be Fully Operational in 2023,” Reuters, October 16, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-natocyber/nato-cyber-command-to-be-fully-operational-in-2023-idUSKCN1MQ1Z9 (accessed May 29, 2022), and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Cyber Defence,” last updated March 23, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_78170.htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 148. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2020, p. 23. See also press release, “Statement by the North Atlantic Council Concerning Malicious Cyber Activities,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 3, 2020, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_ texts_176136.htm (accessed May 29, 2022). 149. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Cyber Defence.” 150. Ibid. 151. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2020, p. 24. 152. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2021, p. 125, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/2022/3/pdf/sgar21-en.pdf (accessed July 6, 2022). 153. Ibid. 154. Dan Sabbagh, “Using Huawei in UK 5G Networks Would Be ‘Madness’, US Says,” The Guardian, January 13, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/ technology/2020/jan/13/using-huawei-in-uk-5g-networks-would-be-madness-us-says (accessed May 30, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 117 155. Press release, “Brussels Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels 14 June 2021,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 14, 2021, last updated April 8, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/ natohq/news_185000.htm#:~:text=It%20guarantees%20the%20security%20of,unity%2C%20solidarity%2C%20and%20cohesion (accessed May 30, 2022). 156. Wolters, statement before Senate Armed Services Committee, March 29, 2022, p. 4. 157. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2021, p. 28. 158. Dorian Archus, “NATO Has Completed AEGIS Upgrade at Romania,” Naval Post, August 11, 2019, https://navalpost.com/nato-has-completedaegis-upgrade-at-romania/ (accessed May 30, 2022). 159. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Ballistic Missile Defence,” last updated January 26, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49635. htm (accessed May 30, 2022). 160. Ibid. 161. Testimony of General Tod D. Wolters, USAF, Commander, U.S. European Command, in hearing, National Security Challenges and U.S. Military Activities in Europe, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, 117th Cong., 1st Sess., April 15, 2021, pp. 16 and 31, https://www. congress.gov/117/chrg/CHRG-117hhrg45430/CHRG-117hhrg45430.pdf (accessed May 30, 2021). 162. United States Department of Defense, “Fact Sheet—U.S. Defense Contributions to Europe.” 163. “US Navy Commissions NSF Redzikowo in Poland,” Naval Technology, September 4, 2020, https://www.naval-technology.com/ news/us-navycommissions-nsf-redzikowo-in-poland/ (accessed May 30, 2022), and Jen Judson, “Construction of Aegis Ashore in Poland Nearing Completion,” Defense News, March 9, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2022/03/09/construction-of-aegis-ashore-in-poland-nearingcompletion/ (accessed May 30, 2022). 164. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Ballistic Missile Defence.” 165. Guest Contributor, “Ballistic Missile Defence and the Type 45 Destroyer,” UK Defence Journal, March 19, 2021, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/ ballistic-missile-defence-and-the-type-45-destroyer/ (accessed July 2, 2021). 166. U.S. Naval Forces Europe and Africa/U.S. Sixth Fleet Public Affairs, “Allied Forces Prepare for the Start of Exercise Formidable Shield 2021,” Naval News, May 4, 2021, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/05/allied-forces-prepare-for-the-start-of-exercise-formidable-shield-2021/ (accessed May 30, 2022), and news release, “Allied Forces Prepare for the Start of Exercise At-Sea Demo/Formidable Shield 2021,” U.S. Sixth Fleet Public Affairs, May 3, 2021, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/2592845/allied-forces-prepare-for-the-start-ofexercise-at-sea-demoformidable-shield-20/ (accessed May 30, 2022). 167. Russian Embassy in Norway and Norway Today, “Russia Threatens Norway to Stay out of NATO Missile Defense,” Atlantic Council, March 21, 2017, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/natosource/russia-threatens-norway-to-stay-out-of-nato-missile-defense/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 168. Seaforces.org, “Royal Norwegian Navy: Fridtjof Nansen Class Frigate,” https://www.seaforces.org/marint/Norwegian-Navy/Frigate/FridtjofNansen-class.htm (accessed May 31, 2022), and Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL33745, updated May 18, 2022, p. 2, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/RL33745.pdf (accessed May 31, 2022). 169. “Norwegian Government Scraps the Wrecked Frigate Helge Ingstad,” The Maritime Executive, January 21, 2021, https://www.maritime-executive. com/article/norwegian-government-scraps-the-wrecked-frigate-helge-ingstad (accessed May 31, 2022). 170. Danish Ministry of Defence, “Agreement for Danish Defence 2018–2023,” https://www.fmn.dk/en/topics/agreements-and-economi/agreementfor-danish-defence-2018---2023/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 171. “Denmark Progresses in NATO Ballistic Missile Defense Role,” Defense News, April 22, 2016, http://www.defensenews.com/story/defense/airspace/strike/2016/04/22/denmark-progresses-nato-ballistic-missile-defense-role/83391868/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 172. Xavier Vavasseur, “Germany and the Netherlands Joining Forces for F-124 / LCF Frigate Replacement,” Naval News, December 18, 2020, https:// www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2020/12/germany-and-the-netherlands-joining-forces-for-f-124-lcf-frigate-replacement/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 173. “HNLMS De Zeven Provincien Successfully Fires Two RIM-162 ESSM,” Navy Recognition, May 21, 2021, https://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/ naval-news/naval-news-archive/2021/may/10177-hnlms-de-zeven-provincien-successfully-fires-two-rim-162-essm.html (accessed May 31, 2022). 174. Xavier Vavasseur, “Royal Netherlands Navy’s HNLMS De Zeven Provinciën Frigate Tracks Ballistic Missile,” Naval News, March 31, 2022, https:// www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/05/royal-netherlands-navys-hnlms-de-zeven-provincien-frigate-tracks-ballistic-missile/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 175. Vavasseur, “Germany and the Netherlands Joining Forces for F-124 / LCF Frigate Replacement.” 176. Xavier Vavasseur, “Video: Admiral De Beurme on Belgian Navy MCM and Frigate Programs,” Naval News, April 5, 2021, https://www.navalnews. com/naval-news/2021/04/video-admiral-de-beurme-on-belgian-navy-mcm-and-frigate-programs/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 177. “Thales to Develop Air Warfare Mission Suite for New Dutch, Belgian Frigates,” Naval Today, February 29, 2019, https://navaltoday. com/2019/02/28/thales-to-develop-air-warfare-mission-suite-for-new-dutch-belgian-frigates/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 118 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 178. Lockheed Martin, “Aegis: The Shield of the Fleet: Deployed Aegis Global Fleet,” https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/products/aegis-combatsystem.html (accessed May 31, 2022), and O’Rourke, “Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” p. 2. 179. “Lockheed Martin to Equip Spanish F-110 Frigates with New Radar System,” Naval Technology, December 6, 2019, https://www.naval-technology. com/news/lockheed-martin-spain-f-110/ (accessed July 10, 2021). 180. “PPA Class Multi-Purpose Offshore Patrol Vessels,” Naval Technology, August 14, 2020, https://www.naval-technology.com/projects/ppa-classmulti-purpose-offshore-patrol-vessels/ (accessed May 31, 2022), and “PPA to Bring BMD Capability to Italian Navy in 2024,” Navy Recognition, March 5, 2018, https://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/naval-news/naval-news-archive/2018/march-2018-navy-naval-defense-news/6008ppa-to-bring-bmd-capability-to-italian-navy-in-2024.html (accessed May 31, 2022). 181. The North Atlantic Treaty, Article 3. 182. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 27, 2022, p. 3, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/220627-def-exp-2022-en.pdf (accessed July 6, 2022). 183. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2021, p. 42. 184. Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014– 2022),” p. 3. 185. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2022), p. 3. 186. Sebastian Sprenger, “Scholz Proposes 100 Billion Euro Defense Fund, Vows to Exceed NATO Spending Goal,” Defense News, February 27, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/02/27/scholz-proposes-100-billion-euro-defense-fund-vows-to-exceed-nato-spendinggoal/ (accessed may 31, 2022). 187. Deutsche Welle, “Germany Commits €100 Billion to Defense Spending,” February 27, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-commits-100billion-to-defense-spending/a-60933724 (accessed May 31, 2022). 188. Deutsche Welle, “German Troop Reinforcements Arrive in Lithuania amid Russia Tensions,” February 14, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/germantroop-reinforcements-arrive-in-lithuania-amid-russia-tensions/a-60774606 (accessed May 18, 2022). 189. Fact Sheet, “NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence.” 191. Reuters, “Germany Vows to Keep Troops in Lithuania, Invest More in Barracks,” February 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lithuanianato/germany-vows-to-keep-troops-in-lithuania-invest-more-in-barracks-idUSKCN1PT1QN (accessed May 31, 2022). 192. News release, “German Air Force Reinforces Patrolling of the Baltic Airspace,” Republic of Lithuania, Ministry of National Defence, July 20, 2020, https://kam.lt/en/news_1098/news_archives/news_archive_2020/news_archive_2020_-_07/german_air_force_reinforces_patrolling_of_the_ baltic_airspace.html (accessed May 31, 2022), and NATO Allied Air Command Public Affairs Office, “Italy Starts First-Time F-35 Deployment,” May 3, 2021, https://www.lockheedmartin.com/f35/news-and-features/italy-starts-first-time-f35-deployment.html (accessed May 31, 2022). 193. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Kosovo Force (KFOR): Key Facts and Figures,” March 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/2022/3/pdf/2022-03-KFOR-Placemat.pdf (accessed May 31, 2022). 194. Federal Government of Germany, “Extension for Mission SEA GUARDIAN,” February 9, 2022, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/ sea-guardian-federal-armed-forces-2004702 (accessed May 31, 2022), and Federal Government of Germany, Federal Foreign Office, “Support for South Sudan,” March 18, 2022, https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/aussenpolitik/laenderinformationen/suedsudan-node/-/2440878 (accessed May 31, 2022). 195. Reuters, “Germany to End EU Training Mission in Mali,” May 5, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germany-ready-continue-unmission-mali-defmin-2022-05-04/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 196. Federal Government of Germany, “German Troops to Remain in Lebanon,” May 12, 2021, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/ extension-unifil-1913790#:~:text=UNIFIL%20mandate%20German%20troops%20to,approved%20by%20the%20German%20Bundestag (accessed May 31, 2022). 197. Federal Government of Germany, Federal Foreign Office, “Germany Continues to Stand Shoulder to Shoulder with the Iraqi Government in the Fight Against IS,” January 28, 2022, https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/aussenpolitik/themen/terrorismus-kriminalitaet/fight-againstis/2383354 (accessed May 31, 2022). 198. Federal Republic of Germany, Federal Ministry of Defence, Bundeswehr, Cyber and Information Domain Service, “Cyber and Information Space—A New Domain,” https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/organization/the-cyber-and-information-domain-service (accessed May 31, 2022). 199. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2022), p. 106. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 119 190. Baltic News Service, “Germany Deploys Ozelot Air Defence System in Lithuania,” LRT [Lithuanian National Television and Radio], April 4, 2022, https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1661776/germany-deploys-ozelot-air-defence-system-in-lithuania (accessed May 31, 2022). 200. Germany at NATO (@GermanyNATO), Tweet, June 29, 2022, 8:40 am, https://twitter.com/GermanyNATO/status/1542125880931241986 (accessed July 6, 2022). 201. Agence France-Presse, “How Germany, Shaken by Ukraine, Plans to Rebuild Its Military,” France 24, March 29, 2022, https://www.france24.com/ en/live-news/20220329-how-germany-shaken-by-ukraine-plans-to-rebuild-its-military (accessed May 31, 2022). 202. Michael Shurkin, “How the Bundeswehr Should Spend Its Money,” War on the Rocks, March 21, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/03/howthe-bundeswehr-should-spend-its-money/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 203. Ibid. and Agence France-Press, “How Germany, Shaken by Ukraine, Plans to Rebuild Its Military.” 204. Shurkin, “How the Bundeswehr Should Spend Its Money,” and Agence France-Presse, “How Germany, Shaken by Ukraine, Plans to Rebuild Its Military.” 205. Reuters, “Germany to Buy 35 Lockheed F-35 Fighter Jets from U.S. amid Ukraine Crisis,” March 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ germany-decides-principle-buy-f-35-fighter-jet-government-source-2022-03-14/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 206. Reuters, “Germany Looks to Buy Israeli or U.S. Missile Defence System,” April 2, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germany-looksbuy-israeli-or-us-missile-defence-system-2022-04-02/ (accessed May 31, 2022); Sebastian Sprenger and Seth J. Frantzman, “German Air Force Banks on Israel’s Arrow-3 for National Missile Shield,” Defense News, April 6, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/04/06/ german-air-force-banks-on-israels-arrow-3-for-national-missile-shield/ (accessed May 31, 2022); Agence France-Presse, “How Germany, Shaken by Ukraine, Plans to rebuild Its Military”; and Reuters, “Germany Looks to Buy Israeli or U.S. Missile Defence System.” 207. Sebastian Sprenger, “Germany Shelves New Anti-Missile Weapon and Turns to Drone Defense,” Defense News, March 23, 2021, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/03/23/germany-shelves-new-anti-missile-weapon-and-turns-to-drone-defense/ (accessed June 10, 2022). 208. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2021, p. 67, and table, “Orders, Deliveries, in Operation Military Aircraft by Country—Worldwide,” summary to May 31, 2022, in Airbus, “A400M,” https://www.airbus.com/en/products-services/defence/military-aircraft/ a400m (accessed June 2, 2022). 209. Trevithick, “Germany, France Move Ahead with Joint C-130J Unit amid Budget Woes and A400M Delays,” The War Zone, May 8, 2018, https:// www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/20697/germany-france-move-ahead-with-joint-c-130j-unit-amid-budget-woes-and-a400m-delays (accessed May 27, 2022). 210. Vivienne Machi, “France, Germany Launch Joint Tactical Air Squadron and Training Center,” Defense News, September 2, 2021, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/09/02/france-germany-launch-joint-tactical-air-squadron-and-training-center/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 211. Stefano D’Urso, “First German C-130J Hercules Performs Maiden Flight,” The Aviationist, November 10, 2021, https://theaviationist. com/2021/11/10/first-german-c-130j/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 212. “Germany Signs Deal to Procure Five Boeing P-8A Poseidon Aircraft,” Naval-Technology, July 1, 2021, https://www.naval-technology.com/news/ germany-five-boeing-p-8a-poseidon-aircraft/ (accessed June 11, 2022). 213. Sebastian Sprenger, “Boeing Gets Nod to Start Building Germany’s P-8 Anti-Submarine Aircraft,” Defense News, September 29, 2021, https:// www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/09/29/boeing-gets-nod-to-start-building-germanys-p-8-anti-submarine-aircraft/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 214. Gastón DuBois, “Boeing and Airbus Team up to Support H-47 Chinook Offer to Germany,” Aviacionline, March 25, 2022, https://www.aviacionline. com/2022/03/boeing-and-airbus-team-up-to-support-h-47-chinook-offer-to-germany/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 215. Shephard News, “Germany Bites the Bullet and Arms Heron TPs,” April 7, 2022, https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/uv-online/germanybites-the-bullet-and-arms-heron-tps/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 216. Vivienne Machi, “With Spain on Board, Final Contracts Imminent for Eurodrone Program,” Defense News, January 27, 2022, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/01/27/with-spain-on-board-final-contracts-imminent-for-eurodrone-program/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 217. Caleb Larson, “France and Germany Are Teaming Up to Build a New Super Tank,” The National Interest, The Reboot Blog, December 12, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/france-and-germany-are-teaming-build-new-super-tank-197825 (accessed May 31, 2022). 218. Harry Lye, “German MoD Mulls Military Equipment Shopping List,” Shephard News, March 16, 2022, https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/ defence-notes/german-mod-mulls-military-equipment-shopping-list/ (accessed May 31, 2022), and Agence France-Presse, “How Germany, Shaken by Ukraine, Plans to Rebuild Its Military.” 219. Tyler Rogoway, “The German Navy Decided to Return Their Bloated New Frigate to the Ship Store This Christmas,” The War Zone, December 23, 2017, http://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/17185/the-german-navy-has-decided-to-return-their-new-frigate-to-the-ship-store-this-christmas (accessed May 31, 2022). 220. William Wilkes, “German Engineering Yields New Warship That Isn’t Fit for Sea,” The Wall Street Journal, January 12, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/ articles/german-engineering-yields-new-warship-that-isnt-fit-for-sea-1515753000 (accessed May 31, 2022). 221. John Beckner and Helmoed Heitman, “Is Germany's Navy Dead?” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, July 23, 2018, https://nationalinterest. org/blog/buzz/germanys-navy-dead-26566 (accessed May 31, 2022), and Ross Clark, “Germany’s Military Has Become a Complete Joke,” The Spectator, August 31, 2019, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/germany-s-military-has-become-a-complete-joke (accessed May 31, 2022). 120 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 222. “Germany Returns Lead F125 Frigate to Builder, Report,” Naval Today, December 22, 2017, https://navaltoday.com/2017/12/22/germany-returnslead-f125-frigate-to-builder-report/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 223. “TKMS Delivers 4th and Final F125 Frigate ‘RHEINLAND-PFALZ,’” Naval News, January 28, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/navalnews/2022/01/tkms-delivers-4th-and-final-f125-frigate-to-the-german-navy/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 224. Reuters, “Germany Awards Warships Construction Contract to Dutch Shipyard Damen,” January 14, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/ germany-awards-warships-construction-con/germany-awards-warships-construction-contract-to-dutch-shipyard-damen-idINL8N29J33J (accessed June 11, 2022). 225. “Damen Signs Mk41 VLS Contract with Lockheed Martin for F126 Frigates,” Naval News, February 16, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/navalnews/2022/02/damen-signs-mk41-vls-contract-with-lockheed-martin-for-f126-frigates/ (accessed June 11, 2022). 226. Naida Hakirevic Prevljak, “Germany, Norway Seal Deal for Six Type 212CD Submarines,” Naval News, July 8, 2021, https://www.navaltoday. com/2021/07/08/germany-seals-deal-for-two-u212cd-submarines/ (accessed May 3119, 2022). 227. Fatima Bahtić, “Work Starts on Last German Navy’s K130 Corvette,” Naval News, February 18, 2022, https://www.navaltoday.com/2022/02/18/ construction-starts-on-last-german-navys-k130-corvette/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 228. Reuters, “Germany Military to Quicken Push for Combat Readiness, Defmin Says,” March 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ germany-military-quicken-push-combat-readiness-defmin-says-2022-03-29/ (accessed May 31, 2022). 229. Information from the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces: Annual Report 2020 (62nd Report), German Bundestag, 19th Electoral Term, Printed Paper 19/26600, February 23, 2021, p. 79, https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/839232/e1a864120697c27057534944ceb20111/ annual_report_2020_62nd_report-data.pdf (accessed May 31, 2022). 230. Ibid., p. 81. 231. Deutsche Welle, “German Submarines Fitted with Russian Technology: Report,” March 28, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/german-submarinesfitted-with-russian-technology-report/a-57030819 (accessed May 31, 2022). 232. Daniel Kochis, “Winds of Change in Berlin? A Road Map for U.S.–German Relations,” The Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3655, September 26, 2021, p. 17, https://www.heritage.org/europe/report/winds-change-berlin-road-map-us-german-relations. 233. Information from the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces: Annual Report 2021 (63rd Report), German Bundestag, Printed Paper 20/900, March 15, 2022, pp. 12, 61, and 63, https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/901614/fc410cdd893ba69d52b8cb55ed1fb715/annual_ report_2021_63rd_report-data.pdf (accessed July 6, 2022). 234. Alex Berry, “Germany Launches New Voluntary Military Service Program,” Deutsche Welle, April 6, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/germanylaunches-new-voluntary-military-service-program/a-57105974 (accessed May 31, 2022). 235. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2022), p. 3. 236. Christina Mackenzie, “Seven European Nations Have Increased Defense Budgets in One Month. Who Will Be Next?” Breaking Defense, March 22, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/03/seven-european-nations-have-increased-defense-budgets-in-one-month-who-will-be-next/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 237. Vivienne Machi, “Next-Gen Tech Investments, Platform Upgrades Lead France’s 2022 Defense Budget,” Defense News, September 22, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/09/22/next-gen-tech-investments-platform-upgrades-lead-frances-2022-defense-budget/ (accessed July 6, 2022). 238. Murielle Delaporte, “France Wants to Transform Its ‘Beautiful’ Army for High-Intensity Warfare,” Breaking Defense, December 16, 2021, https:// breakingdefense.com/2021/12/france-wants-to-transform-its-beautiful-army-for-high-intensity-warfare/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 239. Agence France-Presse, “France Receives Second Lockheed KC-130J, Completing Delivery of 4 Super Hercules Aircraft,” The Defense Post, February 10, 2020, https://www.thedefensepost.com/2020/02/10/france-lockheed-kc-130j-super-hercules/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 240. Table, “Orders, Deliveries, in Operation Military Aircraft by Country—Worldwide,” summary to May 31, 2022, in Airbus, “A330 MRTT,” https://www. airbus.com/en/products-services/defence/military-aircraft/a330-mrtt (accessed June 1, 2022). 241. Table, “Orders, Deliveries, in Operation Military Aircraft by Country—Worldwide,” summary to May 31, 2022, in Airbus, “A400M.” 242. Christina Mackenzie, “France Orders Beefed-Up NH90 Choppers for Special Operations,” Defense News, October 12, 2020, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2020/10/12/france-orders-beefed-up-nh90-choppers-for-special-operations/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 243. David Donald, “France Launches Rafale F4 Upgrade,” AINonline, January 24, 2019, https://www.ainonline.com/aviation-news/ defense/2019-01-24/france-launches-rafale-f4-upgrade (accessed June 1, 2022). 244. Christina Mackenzie, “France Orders $2.3 Billion Upgrade for Rafale Warplanes,” Defense News, January 14, 2019, https://www.defensenews.com/ global/europe/2019/01/14/france-orders-upgraded-rafale-warplanes-for-23-billion/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 245. Younis Dar, “New F4 Rafale Fighter Jets to Have Advanced Stealth & EWS; Is India a Potential Customer?” The EurAsian Times, April 5, 2021, https://eurasiantimes.com/new-f4-rafale-fighter-jets-to-have-advanced-stealth-is-india-a-potential-customer/ (accessed June 1, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 121 246. Airforce Technology, “French Air and Space Force to Receive 12 New Rafales from Dassault,” February 1, 2021, https://www.airforce-technology. com/news/french-air-and-space-force-to-receive-12-new-rafales-from-dassault/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 247. “France, Germany Spain Reach FCAS Agreement,” Defense Brief, May 17, 2021, https://defbrief.com/2021/05/17/france-germany-spain-reachfcas-agreement/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 248. Hanan Zaffar, “Setback to European Fighter Jet as Companies in Deadlock,” The Defense Post, March 9, 2022, https://www.thedefensepost. com/2022/03/09/fcas-program-airbus-dassault/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 249. Pfeifer and White, “Divisions Risk Undermining Windfall for Europe’s Defence Industry.” 250. Ibid. 251. Christina Mackenzie, “France, Spain Ink Deals to Upgrade Tiger Attack Helicopters,” Breaking Defense, March 11, 2022, https://breakingdefense. com/2022/03/france-spain-ink-deals-to-upgrade-tiger-attack-helicopters/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 252. Christina Mackenzie, “France Plans to Boost Its Self-Defense Posture in Space,” Defense News, July 26, 2019, https://www.defensenews.com/ global/europe/2019/07/26/france-plans-to-boost-its-self-defense-posture-in-space/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 253. Christina Mackenzie, “NATO Names Location for New Military Space Center,” Defense News, February 5, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/ space/2021/02/05/nato-names-location-for-new-military-space-center/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 254. Lauren Chadwick and Jeremy Wilks, “‘May the Force Be with Vous’: France Unveils Space Weapons Plan,” Euronews, updated July 26, 2019, https://www.euronews.com/2019/07/26/may-the-force-be-with-vous-france-unveils-space-weapons-plan (accessed June 1, 2022), and Rachel Cordery, “French Defence Minister Announces Anti-Satellite Laser Weapons,” Airforce Technology, July 26, 2019, https:// www.airforcetechnology.com/news/french-anti-satellite-laser-weapon/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 255. Deutsche Welle, “France Conducts First Military Exercises in Space,” March 10, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/france-conducts-first-militaryexercises-in-space/a-56821868 (accessed June 1, 2022). 256. Doug Messier, “AsterX 2022: The Space Threat Under the Eye of the Space Command and CNES,” Parabolic Arc, March 14, 2022, http://www. parabolicarc.com/2022/03/14/asterx-2022-the-space-threat-under-the-eye-of-the-space-command-and-cnes/ (accessed June 1, 2022), and Zach, “The Space Surveillance Operations Center at the ASTERX 22 Exercise in France,” D1SoftBallNews, March 15, 2022, https://d1softballnews. com/the-space-surveillance-operations-center-at-the-asterx-22-exercise-in-france/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 257. Machi, “Next-Gen Tech Investments, Platform Upgrades Lead France’s 2022 Defense Budget.” 258. Eyal Boguslavsky, “French Army Continues to Arm with H&K’s HK416F Assault Rifles,” Israel Defense, March 14, 2022, https://www.israeldefense. co.il/en/node/53910 (accessed May 19, 2022); Tong Ong, “Parrot to Supply French Army with Hundreds of Micro-Drones,” The Defense Post, January 12, 2021, https://www.thedefensepost.com/2021/01/12/french-army-parrot-micro-drones/ (accessed June 1, 2022); and “Future Army Serval Armored Reconnaissance Vehicle to Be Delivered in Three Variants,” Army Recognition, February 2, 2022, https://www.armyrecognition. com/defense_news_february_2022_global_security_army_industry/future_french_army_serval_armored_reconnaissance_vehicle_to_be_ delivered_in_three_variants.html?fbclid=IwAR18ZlFLoHwraqXvbu6SSkdiDHNfCNrqwXO7JsOLWC0jarLJ8DKrVec9Asw (accessed June 1, 2022). 259. Machi, “Next-Gen Tech Investments, Platform Upgrades Lead France’s 2022 Defense Budget.” 260. Christina Mackenzie, “See France Test-Fire an M51 Strategic Missile into the Atlantic,” Defense News, April 28, 2021, https://www.defensenews. com/global/europe/2021/04/28/france-test-fires-an-m51-strategic-missile-into-the-atlantic/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 261. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2022), p. 104. 262. Thomas Newdick, “France Has Increased Its Ballistic Missile Submarine Patrols for the First Time in Decades,” The War Zone, March 24, 2022, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/44910/france-has-increased-its-ballistic-missile-submarine-patrols-for-the-first-time-in-decades (accessed June 1, 2022). 263. Christina Mackenzie, “France to Begin Building New Ballistic Missile Subs,” Defense News, February 22, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/ naval/2021/02/22/france-to-begin-building-new-ballistic-missile-subs/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 264. Christina Mackenzie, “Macron Kicks off French Race to Build a New Nuclear-Powered Aircraft Carrier,” Defense News, December 8, 2020, https:// www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2020/12/08/macron-kicks-off-french-race-to-build-a-new-nuclear-powered-aircraft-carrier/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 265. Maritime Fairtrade, “France’s Aircraft Carriers to Account for 20% of Naval Vessel Spend over Next 10 Years,” December 17, 2021, https:// maritimefairtrade.org/frances-aircraft-carriers-to-account-for-20-of-naval-vessel-spend-over-next-10-years/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 266. Michael Peck, “France Is Still Mad at the US over a Lost Submarine Deal, But That Isn’t Keeping It from Buying US Gear for Its New Aircraft Carrier,” Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/france-buying-emals-for-aircraft-carrier-despite-us-aukus-ire-202112#:~:text=EMALS%20and%20AAG%20will%20be,%2Dgeneration%20aircraft%20carrier%20program.%22&text=Electromagnetic%20 catapults%20such%20as%20EMALS,kicking%20jets%20off%20floating%20airfields (accessed June 1, 2022). 122 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 267. Emmanuel Huberdeau, “France Launches First Barracuda SSN,” Janes, July 12, 2019, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/francelaunches-first-barracuda-ssn (accessed May 27, 2022), and “New Suffren Barracuda-Class Nuclear-Powered Attack Submarine Officially Commissioned by French Navy,” Navy Recognition, November 2020, https://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/news/defence-news/2020/november/9236-newsuffren-barracuda-class-nuclear-powered-attack-submarine-officially-commissioned-by-french-navy.html (accessed June 1, 2022). 268. Dylan Malyasov, “France Rolls Out New Nuclear-Powered Attack Submarine,” Defence Blog, modified November 29, 2021, https://defence-blog. com/france-rolls-out-new-nuclear-powered-attack-submarine/#:~:text=The%204%2C500%20Duguay%2DTrouin%20S636,enduring%20and%20 quick%20to%20deploy (accessed June 1, 2022). 269. “France Accelerates the FDI Frigates Program,” Navy Recognition, March 2021, https://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/news/defencenews/2021/march/9901-france-accelerates-the-fdi-frigates-program.html (accessed June 1, 2022). 270. Xavier Vavasseur, “France’s Final FREMM Frigate ‘Lorraine’ Starts Sea Trials,” Naval News, February 22, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/navalnews/2022/02/frances-final-fremm-frigate-lorraine-starts-sea-trials/ (accessed June 1, 2022), and Christina Mackenzie, “Naval Group Delivers French Frigate with Bolstered Capabilities,” Defense News, April 16, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2021/04/16/naval-groupdelivers-french-frigate-with-bolstered-capabilities/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 271. Christina Mackenzie, “French Navy Begins Broad Revamp of Its Mine-Hunting Abilities,” Defense News, November 6, 2020, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2020/11/06/french-navy-begins-broad-revamp-of-its-mine-hunting-abilities/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 272. Harry Lye, “UK, France to Sign Autonomous Minehunting Production Contract,” Naval Technology, November 3, 2020, https://www.navaltechnology.com/news/contract-news/uk-france-to-sign-autonomous-minehunting-production-contract/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 273. “France, UK Take Delivery of New Unmanned Minehunting Demonstrators,” Defense Brief, December 8, 2021, https://defbrief.com/2021/12/08/ france-uk-take-delivery-of-new-unmanned-minehunting-demonstrators/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 274. Marine Pennetier, “Under Threat, France Grooms Army Hackers for Cyber Warfare,” Reuters, April 5, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/usfrance-cyber/under-threat-france-grooms-army-hackers-for-cyber-warfare-idUSKBN1771B2 (accessed June 1, 2022). 275. Arthur P. B. Laudrain, “France’s New Offensive Cyber Doctrine,” Lawfare, February 26, 2019, https://www.lawfareblog.com/frances-newoffensive-cyber-doctrine (accessed June 1, 2022). 276. Machi, “Next-Gen Tech Investments, Platform Upgrades Lead France’s 2022 Defense Budget.” 277. Chapter Four, “Europe,” in International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, pp. 64–163. 279. Martin Manaranche, “French Carrier Strike Group Begins ‘Clemenceau 22’ Deployment,” Naval News, February 1, 2022, https://www.navalnews. com/naval-news/2022/02/french-carrier-strike-group-begins-clemenceau-22-deployment/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 280. Factsheet, “NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence,” and ERR [Estonian Public Broadcasting], “France Sending More Forces to Estonia,” February 25, 2022, https://news.err.ee/1608512663/france-sending-more-forces-to-estonia (accessed June 1, 2022). 281. Government of France, Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, “France Diplomacy: France and NATO,” https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/ french-foreign-policy/security-disarmament-and-non-proliferation/our-alliances-and-cooperations/france-and-nato/ (accessed June 1, 2022), and news release, “French Air and Space Force Employs Assets for NATO’s Deterrence and Defence,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Air Command, March 1, 2022, https://ac.nato.int/archive/2022/FRA_EVA (accessed June 1, 2022). 282. Government of France, Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, “France Diplomacy: France and NATO,” and news release, “French Air and Space Force Employs Assets for NATO’s Deterrence and Defence,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Air Command, March 1, 2022, https:// ac.nato.int/archive/2022/FRA_EVA (accessed June 1, 2022). 283. News release, “France Sends Troops and Equipment to Romania,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, March 8, 2022, https://shape.nato.int/news-archive/2022/france-sends-troops-and-equipment-to-romania (accessed June 1, 2022). 284. Archyde, “French Armed Forces Prepare for High Intensity War,” March 30, 2021, https://www.archyde.com/french-armed-forces-prepare-forhigh-intensity-war/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 285. Associated Press, “France and EU to Withdraw Troops from Mali, Remain in Region,” U.S. News & World Report, February 17, 2022, https://www. usnews.com/news/world/articles/2022-02-17/eu-nations-to-withdraw-military-task-force-from-mali (accessed June 1, 2022). 286. Infographic, “Déploiements Opérationnels des Forces Armées Françaises [Operational Deployments of the French Armed Forces],” in Government of France, Ministry of the Armed Forces, “Operations,” https://www-defense-gouv-fr.translate.goog/operations/operations?_x_tr_ sl=fr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc (accessed June 1, 2022). 287. Ibid. 288. European Union Naval Force Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR MED), Operation IRINI, “About Us,” https://www.operationirini.eu/about-us/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 289. Abhijnan Rej, “France-Led Multination Naval Exercise Commences in Eastern Indian Ocean,” The Diplomat, April 5, 2021, https://thediplomat. com/2021/04/france-led-multination-naval-exercise-commences-in-eastern-indian-ocean/ (accessed June 1, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 123 278. Infographic, “Opération CHAMMAL,” in Government of France, Ministry of the Armed Forces, “Operations: Operation CHAMMAL,” https://www. defense.gouv.fr/operations/grand-levant/operation-chammal (accessed June 1, 2022). 290. Reuters, “French Nuclear Submarine Patrolled in South China Sea—Navy,” February 9, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/southchina-seafrance-submarine-idUSL1N2KF1J7 (accessed June 1, 2022). 291. Nathalie Guibert and Elise Vincent, “Admiral Pierre Vandier: In the Indo-Pacific, ‘We Face a Stifling Logic of Suffocation,’” Le Monde, June 10, 2021, https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2021/06/10/amiral-pierre-vandier-en-indo-pacifique-nous-affrontons-une-logique-detouffement_6083594_3210.html (accessed June 1, 2022). 292. “Two Years of Operation AGENOR in Gulf and Strait of Hormuz,” SeaWaves Magazine, March 1, 2022, https://seawaves.com/?p=19597 (accessed June 2, 2022). 293. France 24, “Macron Launches Army Operation Resilience to Support Fight Against Coronavirus,” March 25, 2020, https://www.france24.com/ en/20200325-macron-launches-army-operation-resilience-to-support-fight-against-coronavirus (accessed June 2, 2022). 294. Jean-Pierre Maulny, Deputy Director, French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs, “Lessons Learned from France’s Military Engagements in Foreign Operations and Internal Security,” in Bastian Giegerich and James Hackett, “Military Capabilities in Europe: A Framework for Assessing the Qualitative Dimension,” International Institute for Strategic Studies Research Paper, January 2022, pp. 8–9, https:// www.iiss.org/blogs/research-paper/2022/02/military-capabilities-in-europe-a-framework-for-assessing-the-qualitative-dimension (accessed June 2, 2022). 295. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2022), p. 3. 296. Joseph Trevithick, “Everything We Know About the United Kingdom's Big New Defense Spending Plan,” The War Zone, November 19, 2020, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/37722/everything-we-know-about-the-united-kingdoms-big-new-defense-spending-plan (accessed June 2, 2022). 297. Her Majesty’s Government, Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty, CP 403, March 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/975077/Global_Britain_in_a_Competitive_Age-_the_Integrated_Review_of_ Security__Defence__Development_and_Foreign_Policy.pdf (accessed June 14, 2022), and U.K. Ministry of Defence, Defence in a Competitive Age, Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Defence by Command of Her Majesty, CP 411, March 2021, https://assets.publishing. service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/974661/CP411_-Defence_Command_Plan.pdf (accessed June 14, 2022) 298. U.K. Ministry of Defence, Defence in a Competitive Age, pp. 49 and 52. 299. Ibid., pp. 48 and 56. 300. Ibid., p. 53, and Daniel Kochis, “European Defense Spending Still Rising, but COVID-19 Poses Retrenching Risk,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, April 6, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/europe/commentary/european-defense-spending-still-rising-covid-19-poses-retrenchingrisk. 301. Douglas Barrie, Ben Barry, Henry Boyd, and Nick Childs, “The UK’s New Model Forces,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, Analysis Blog, March 24, 2021, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2021/03/uk-defence-command-paper (accessed June 2, 2022). 302. U.K. Ministry of Defence, Defence in a Competitive Age, p. 54. 303. Andrew Chuter, “Did Russia’s War Sink the Latest British Defense Strategy?” Defense News, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/ europe/2022/04/05/did-russias-war-sink-the-latest-british-defense-strategy/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 304. U.K. Ministry of Defence, The Defence Equipment Plan 2021–2031, 2022, p. 5, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1055953/Defence_Equipment_Plan_2021.pdf (accessed June 14, 2022). This “report is published in parallel with a review by the National Audit Office (NAO), who review our plans each year and provide feedback on areas for improvement.” Ibid., p. 7. See National Audit Office, The Equipment Plan 2021 to 2031, Ministry of Defence, Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, HC 1105, February 21, 2022, https://collateral.prmax.co.uk/collateral/189946.pdf (accessed June 14, 2022). 305. U.K. Ministry of Defence, The Defence Equipment Plan 2021–2031, 2022, pp. 36, 36, 38, 40, 42, and 44. 306. The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP, Secretary of State for Defence, “Secretary of State Foreword,” in ibid., p. 2. 307. National Audit Office, The Equipment Plan 2021 to 2031, p. 12. See also Figure 10, “Our Audit Approach,” in ibid., p. 45. 308. Andrew Chuter, “British Army Admits More Delays in Fielding Enough Combat Forces,” Defense News, October 12, 2020, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2020/10/12/british-army-admits-more-delays-in-fielding-enough-combat-forces/ (accessed June 14, 2022). 309. Ibid. See also Ben Barry, “British Army Heavy Division Comes up Light,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, Military Balance Blog, January 8, 2021, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2021/01/british-army-heavy-division (accessed June 14, 2022). 310. Andrew Chuter and Sebastian Sprenger, “British Military Looks to the ‘Eurotank’ as It Weighs Its Hardware Options,” Defense News, January 11, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/01/11/british-military-looks-to-the-eurotank-as-it-weighs-its-hardware-options/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 124 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 311. Samuel Cranny-Evans, “UK to Reduce Operational Challenger 2 Tank Fleet,” Janes, April 23, 2019, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/newsdetail/uk-to-reduce-operational-challenger-2-tank-fleet (accessed June 2, 2022). 312. David Axe, “British Army Is Planning to Upgrade Just 148 of Its 227 Challenger 2 Tanks,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, April 21, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/british-army-planning-upgrade-just-148-its-227-challenger-2-tanks-53587 (accessed June 2, 2022). 313. David Axe, “British Army, German Tanks. London Might Not Like It, but It Needs to Buy Leopard 2s,” Forbes, November 11, 2020, https://www. forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2020/11/11/british-army-german-tanks-london-might-not-like-it-but-it-needs-to-buy-leopard-2s/?sh=32f598922d7a (accessed June 2, 2022). 314. Cranny-Evans, “UK to Reduce Operational Challenger 2 Tank Fleet.” 315. U.K. Ministry of Defence, Defence in a Competitive Age, p. 54. 316. Stuart Crawford, “The Future UK Main Battle Tank Fleet,” UK Defence Journal, March 22, 2021, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/the-future-ukmain-battle-tank-fleet/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 317. Caleb Larson, “Production of the British Challenger 3 Tank Has Begun,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, March 29, 2022, https:// nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/production-british-challenger-3-tank-has-begun-201526 (accessed June 2, 2022). 318. Andrew Chuter, “British Army Wants More Punch in Its Boxer Vehicle Fleet,” Defense News, April 6, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/ europe/2021/04/06/british-army-wants-more-punch-in-its-boxer-vehicle-fleet/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 319. Shephard News, “British Army Orders 100 More Boxer Armored Vehicles,” April 11, 2022, https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/landwarfareintl/ british-army-orders-100-more-boxer-armoured-vehicl/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 320. Chuter, “British Army Wants More Punch in Its Boxer Vehicle Fleet.” 321. Shephard News, “British Army Orders 100 More Boxer Armored Vehicles.” 322. George Allison, “More F-35B Jets Being Delivered to the UK,” UK Defence Journal, February 15, 2022, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/more-f35b-jets-being-delivered-to-the-uk/#:~:text=The%20aircraft%20are%20being%20flown,by%20the%20end%20of%202025 (accessed June 2, 2022). 323. Aaron Mehta, “New British Plan Looks to Boost F-35 Numbers, but Is It Still Aiming for 138?” Defense News, March 22, 2021, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/03/23/new-british-plan-looks-to-boost-f-35-numbers-but-is-it-still-aiming-for-138/ (accessed June 14, 2022), and U.K. Ministry of Defence, Defence in a Competitive Age, p. 56. 325. Ed Adamczyk, “Britain’s Royal Air Force Receives Last Typhoon Fighter on Order from BAE,” United Press International, September 27, 2019, https://www.upi.com/Defense-News/2019/09/27/Britains-Royal-Air-Force-receives-last-Typhoon-fighter-on-order-from-BAE/7821569598752/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 326. George Allison, “24 Typhoon Aircraft to Be Retired by 2025,” UK Defence Journal, March 22, 2021, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/24-typhoonaircraft-to-be-retired-by-2025/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 327. Andrew Chuter, “The British Air Force Is Upgrading Its Typhoon Fighter Jets to Keep Them Fighting Until 2040,” Business Insider, August 9, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/british-air-force-sensor-upgrades-typhoon-fighter-jets-2019-8 (accessed June 2, 2022). 328. “UK Defence to Invest £2bn in Combat Air System Tempest,” Government Computing, March 25, 2021, https://www.governmentcomputing.com/ national-security/news/uk-defence-to-invest-2bn-in-combat-air-system-tempest/ (accessed June 2, 2022), and Brent M. Eastwood, “Tempest: The UK Has Big Plans for a Stealth 6th Generation Fighter,” 1945, February 16, 2022, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2022/02/tempest-the-uk-hasbig-plans-for-a-stealth-6th-generation-fighter/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 329. Alan Warnes, “NATO Air-to-Air Refuelling,” European Security & Defence, December 13, 2019, https://euro-sd.com/2019/12/articles/15526/natoair-to-air-refuelling/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 330. Royal Air Force, “Aircraft: RC-135W Rivet Joint: About the RC-135W Rivet Joint,” https://www.raf.mod.uk/aircraft/airseeker-rc-135w-rivet-joint/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 331. George Allison, “UK Planning to Purchase Additional A400M Transport Aircraft,” UK Defence Journal, January 6, 2022, https://ukdefencejournal. org.uk/uk-planning-to-purchase-additional-a400m-transport-aircraft/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 332. News release, “RAF Sentinel R1 Aircraft Conducts Last Operational Flight,” Royal Air Force, February 26, 2021, https://www.raf.mod.uk/news/ articles/raf-sentinel-r1-aircraft-conducts-last-operational-flight/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 333. News release, “Final Poseidon Aircraft Delivered to RAF Lossiemouth,” U.K. Ministry of Defence, January 12, 2021, https://des.mod.uk/poseidonaircraft-delivered-raf-lossiemouth/#:~:text=The%20ninth%20and%20final%20Poseidon,multi%2Drole%20maritime%20patrol%20aircraft (accessed June 3, 2022). 334. David Axe, “The Royal Air Force Needs More Patrol Planes,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, January 1, 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/ blog/buzz/royal-air-force-needs-more-patrol-planes-110231 (accessed June 3, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 125 324. ITV News, “UK’s F-35 Fighter Jets Join Operations Against IS Above Iraq and Syria,” June 25, 2019, https://www.itv.com/news/2019-06-25/uks-f35-fighter-jets-join-operations-against-is-above-iraq-and-syria (accessed June 3, 2022). 335. Harry Lye, “UK’s New Medium Helicopter to Fly into 2040s,” Army Technology, April 8, 2021, https://www.army-technology.com/news/ukmedium-helicopter-requirement/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 336. David B. Larter, “In a Naval Confrontation with Iran, Great Britain Can Find Neither Ships nor Friends,” Defense News, July 25, 2019, https://www. defensenews.com/naval/2019/07/25/in-a-naval-confrontation-with-iran-great-britain-can-find-neither-ships-nor-friends/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 337. Ibid. and Table 4, “Availability of Royal Navy Vessels by Class,” in U.K. House of Commons Defence Committee, “We’re Going to Need a Bigger Navy,” Third Report of Session 2021–22, HC 168, December 14, 2021, p. 43, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8205/ documents/85026/default/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 338. U.K. House of Commons Defence Committee, “We’re Going to Need a Bigger Navy,” p. 3. 339. Barrie et al., “The UK’s New Model Forces.” 340. Seaforces.org, “City (Type 26) Class Frigate (Global Combat Ship Programme),” https://www.seaforces.org/marint/Royal-Navy/Frigate/City-Type26-class.htm (accessed June 3, 2022). 341. Fatima Bahtić, “UK’s First Type 26 Frigate to Hit the Water Later This Year,” Naval Today, March 8, 2022, https://www.navaltoday. com/2022/03/08/uks-first-type-26-frigate-to-hit-the-water-later-this-year/ (accessed June 3, 2022), and Navy Lookout, “Royal Navy’s Type 26 Frigates to Be Equipped with Cruise Missiles by 2028,” July 9, 2021, https://www.navylookout.com/royal-navys-type-26-frigates-to-beequipped-with-cruise-missiles-by-2028/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 342. Bahtić, “UK’s First Type 26 Frigate to Hit the Water Later This Year.” 343. Fatima Bahtić, “UK to Retire Two Type 23 Frigates Saving £100M to Boost Future Fleet,” Naval Today, November 24, 2021, https://www. navaltoday.com/2021/11/24/uk-to-retire-two-type-23-frigates-saving-100m-to-boost-future-fleet/ (accessed June 3, 2022), and Harry Lye, “Royal Navy to lose Type 23s setting stage for future fleet,” Naval Technology, March 23, 2021, https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/royalnavy-to-lose-two-type-23s-setting-stage-for-future-fleet/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 344. Constantine Atlamazoglou, “The UK’s New Aircraft Carrier Wrapped up Its Maiden Deployment with 2 More Milestones—One Good and One Bad,” Business Insider, December 28, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/new-uk-aircraft-carrier-ends-first-deployment-with-milestones-2021-12 (accessed June 3, 2022). 345. Nick Childs, “UK Carrier Strike Capability: Where Next?” International Institute for Strategic Studies, Military Balance Blog January 7, 2022, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2022/01/uk-carrier-strike-capability-where-next (accessed June 3, 2022). 346. Atlamazoglou, “The UK’s New Aircraft Carrier Wrapped up Its Maiden Deployment with 2 More Milestones—One Good and One Bad.” 347. James Hirst, “Prince Charles Attends Commissioning of HMS Prince of Wales,” Forces.net, December 10, 2019, https://www.forces.net/news/ prince-charles-attend-commissioning-hms-prince-wales (accessed June 3, 2022). 348. Harry Lye, “HMS Prince of Wales to Begin F-35 Trials in January 2021: Exclusive,” Naval Technology, March 2, 2020, https://www.naval-technology. com/news/hms-prince-of-wales-to-begin-f-35-trials-in-january-2021-exclusive/ (accessed June 3, 2022), and Jemma Carr, “Royal Navy’s Newest Aircraft Carrier HMS Prince of Wales Returns to the Sea After Two Leaks in Five Months and £3.3Million Repairs,” Daily Mail, April 30, 2021, https:// www.msn.com/en-gb/news/world/hms-prince-of-wales-returns-to-the-sea-after-two-leaks-in-five-months/ar-BB1gf5KJ?MSCC=1604183894 (accessed June 3, 2022). 349. Carr, “HMS Prince of Wales Returns to the Sea After Two Leaks in Five Months and £3.3Million Repairs.” 350. David Axe, “Attention Navy Fans, Britain’s Type 26 Frigate Is Nearly Here,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, September 1, 2019, https:// nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/attention-navy-fans-britains-type-26-frigate-nearly-here-77006 (accessed June 3, 2022), and ITV News, “UK’s F-35 Fighter Jets Join Operations Against IS Above Iraq and Syria.” 351. “HMS Prince of Wales to Lead NATO Task Force in the Arctic,” Naval News, March 8, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/03/ hms-prince-of-wales-to-lead-nato-task-force-in-the-arctic/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 352. News release, “Testing the Latest Astute Class Submarine,” BAE Systems, February 11, 2022, https://www.baesystems.com/en-us/article/testingthe-latest-astute-class-submarine (accessed June 3, 2022). 353. Harry Lye, “Royal Navy to Begin Unmanned Minehunting Operations,” Naval Technology, January 14, 2020, https://www.naval-technology.com/ news/royal-navy-to-begin-unmanned-minehunting-operations/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 354. Hanan Zaffar, “UK Orders Additional Mine-Hunting System for Royal Navy,” The Defense Post, February 7, 2022, https://www.thedefensepost. com/2022/02/07/royal-navy-mine-hunting-system/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 355. Her Majesty’s Government, Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, p. 76. 356. Nick Childs, “The UK’s Dreadnought Programme: The Latest Lessons,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, Military Balance Blog, January 21, 2022, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2022/01/the-uks-dreadnought-programme-the-latest-lessons (accessed June 4, 2022). 357. Dan Taylor, “MOD ‘Orders Review into Concerns over Dreadnought Submarine Programme,” The Mail, May 5, 2021, https://www.nwemail.co.uk/ news/19278533.mod-orders-review-concerns-dreadnought-submarine-programme/ (accessed June 14, 2022). 126 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 358. News story, “Defence Secretary and Polish Counterpart Reaffirm Commitment to European Security,” U.K. Ministry of Defence and The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP, February 8, 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-secretary-and-polish-counterpart-reaffirm-commitment-toeuropean-security#:~:text=The%20Defence%20Secretary%20confirmed%20that,tensions%20on%20the%20Ukrainian%20border (accessed June 4, 2022). 359. George Allison, “How Many British Tanks and Troops Are in Estonia?” UK Defence Journal, March 1, 2022, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/howmany-british-tanks-and-troops-are-in-estonia/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 360. News story, “Defence Secretary and Polish Counterpart Reaffirm Commitment to European Security.” 361. Reuters, “British Troops to Join NATO Combat Unit in Bulgaria—PM Petkov,” March 24, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/british-troopsjoin-nato-combat-unit-bulgaria-pm-petkov-2022-03-24/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 362. News story, “RAF Typhoons Begin NATO Air Policing Mission in Lithuania,” U.K. Ministry of Defence and The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP, May 1, 2020, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/raf-typhoons-begin-nato-air-policing-mission-in-lithuania (accessed July 3, 2021). 363. News release, “Royal Air Force Typhoons Support NATO’s Enhanced Air Policing in Romania,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Air Command, March 31, 2022, https://ac.nato.int/archive/2022/RAFeAPRomania2022 (accessed June 4, 2022). 364. News release, “RAF F-35 Lightnings Join NATO mission,” Royal Air Force, March 4, 2022, https://www.raf.mod.uk/news/articles/raf-f-35lightnings-join-nato-mission/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 365. George Allison, “British Jets Complete Icelandic Air Policing Mission,” UK Defence Journal, December 11, 2019, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/ british-jets-complete-icelandic-air-policing-mission/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 366. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Resolute Support Mission, “Resolute Support Mission (RSM): Key Facts and Figures,” February 2021, https:// www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2021/2/pdf/2021-02-RSM-Placemat.pdf (accessed June 4, 2022). 367. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Kosovo Force, “Kosovo Force (KFOR): Key Facts and Figures.” 368. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Maritime Command, “Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group One (SNMCMG1),” https://mc.nato. int/snmcmg1 (accessed June 5, 2022); North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Maritime Command, “Standing NATO Maritime Group One (SNMG1),” https://mc.nato.int/SNMG1 (accessed June 5, 2022); and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Maritime Command, “Standing NATO Maritime Group Two (SNMG2),” https://mc.nato.int/SNMG2 (accessed June 5, 2022). 369. Forces.net, “Operation Shader: All You Need to Know About Britain’s Fight Against IS,” June 22, 2021, https://www.forces.net/news/three-yearsop-shader-1500-airstrikes-against-islamic-state (accessed June 4, 2022). 370. James Hirst, “UK to Increase Military Training Presence in Iraq,” Forces.net, February 18, 2021, https://www.forces.net/news/iraq/uk-increasemilitary-training-presence-iraq (accessed June 4, 2022). 371. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2019, p. 66. 372. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2022), p. 3. 373. Tom Kington, “Italy Defense Budget Rebounds Despite Coronavirus,” Defense News, October 28, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/global/ europe/2020/10/28/italy-defense-budget-rebounds-despite-covid-crisis/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 374. Tom Kington, “Italy Aims to Reach NATO Defense-Spending Target by 2028, Four Years Late,” Defense News, April 1, 2022, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/04/01/italy-aims-to-reach-nato-defense-spending-target-by-2028-four-years-late/ (accessed June 14, 2022). 375. Tim Fish, “Italy’s Army Modernization Finally Seeing Movement After Years of Delays,” Breaking Defense, November 24, 2021, https:// breakingdefense.com/2021/11/italys-army-modernization-finally-seeing-movement-after-years-of-delays/ (accessed June 14, 2022). 376. Crispian Balmer and Angelo Amante, “Italy Defers NATO Defense Spending Goal to 2028 in Coalition Compromise,” Reuters, March 31, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/italy-defers-nato-defence-spending-goal-2028-coalition-compromise-2022-03-31/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 377. David Cenciotti, “First Two T-345 Trainers Delivered to the Italian Air Force,” The Aviationist, December 23, 2020, https://theaviationist. com/2020/12/23/first-two-t-345-trainers-delivered-to-the-italian-air-force/ (accessed June 15, 2022); Military Leak, “Italian Ministry of Defense to Fund MC-27J Praetorian Military Transport Aircraft Development,” August 17, 2021, https://militaryleak.com/2021/08/17/italian-ministry-ofdefence-to-fund-mc-27j-praetorian-military-transport-aircraft-development/ (accessed June 4, 2022), and Stefano D’Urso, “Italy Increasing Tempest Funding and Planning New Support Aircraft Acquisitions,” The Aviationist, August 18, 2021, https://theaviationist.com/2021/08/18/italydpp-2021-2023/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 378. David Cenciotti and Stefano D'Urso, “Third Italian F-35B Goes to the Italian Air Force. And the Italian Navy Is Not Happy at All,” The Aviationist, February 26, 2020, https://theaviationist.com/2020/02/26/third-italian-f-35b-goes-to-the-italian-air-force-and-the-italian-navy-is-not-happyat-all/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 379. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, pp. 120–121. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 127 380. Airbus, “Eurodrone,” https://www.airbus.com/en/defence/eurodrone (accessed June 4, 2022), and D’Urso, “Italy Increasing Tempest Funding and Planning New Support Aircraft Acquisitions.” 381. Mansij Asthana, “Big Boost to Sixth-Gen Tempest Fighter Program as Italy and Sweden Ink Trilateral Agreement,” The EurAsian Times, January 7, 2021, https://eurasiantimes.com/big-boost-to-sixth-gen-tempest-fighter-program-as-italy-uk-and-sweden-ink-trilateral-agreement/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 382. Luca Peruzzi, “Italy’s Defense Ministry Multi-Year Planning Document 2021–2023,” European Security & Defence, October 22, 2021, https://eurosd.com/2021/10/articles/exclusive/24116/italys-defence-multi-year-planning-document-2021-2023/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 383. Tom Kington, “Italian Military Chief Envisions the Tempest Fighter Zapping Missiles,” Defense News, April 13, 2021, https://www.defensenews. com/global/europe/2021/04/13/italian-military-chief-envisions-the-tempest-fighter-zapping-missiles/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 384. Fish, “Italy’s Army Modernization Finally Seeing Movement After Years of Delays.” 385. Luca Peruzzi, “First Details About the Italian Navy’s U212 NFS,” Naval News, January 13, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/01/ first-details-about-the-italian-navys-u212-nfs/ (accessed June 4, 2022); Kington, “Italy Defense Budget Rebounds Despite Coronavirus”; Luca Peruzzi, “Italy’s New Defence Budget Plan: What Is New?” European Security & Defense, September 19, 2019, https://euro-sd.com/2019/09/ articles/14456/italys-new-defence-budget-plan-what-is-new/ (accessed June 4, 2022); and Xavier Vavasseur, “MBDA Unveils New Teseo Mk2/E Anti-Ship Missile at SEAFUTURE 2021,” Naval News, September 28, 2021, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/09/mbda-unveils-newteseo-mk2-e-anti-ship-missile-at-seafuture-2021/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 386. Xavier Vavasseur, “Fincantieri Launched the Italian Navy’s Tenth and Final FREMM Frigate,” Naval News, January 27, 2020, https://www. navalnews.com/naval-news/2020/01/fincantieri-launched-the-italian-navys-tenth-and-final-fremm-frigate/ (accessed June 4, 2022), and Tom Kington, “Italy Plans New Destroyers for 2028 Delivery,” Defense News, November 9, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/global/ europe/2020/11/09/italy-plans-new-destroyers-for-2028-delivery/#:~:text=ROME%20%E2%80%94%20Fresh%20from%20a%20burst,of%20 its%20fleet%20%E2%80%94%20new%20destroyers (accessed June 4, 2022). 387. News release, “NATO Operation Sea Guardian Focused Patrols Return to Central Mediterranean,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Maritime Command, March 11, 2021, https://mc.nato.int/media-centre/news/2021/nato-operation-sea-guardian-focused-patrols-return-tocentral-mediterranean (accessed June 4, 2022); European Union Naval Force Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR MED), Operation IRINI, “About Us”; Naida Hakirevic Prevljak, “EU Naval Operation Atalanta Extended Until December 2022,” Naval Today, January 4, 2021, https://www. navaltoday.com/2021/01/04/eu-naval-operation-atalanta-extended-until-december-2022/ (accessed June 4, 2022); “Marina Militare: Cambio commando all’Operazione ‘Mare Sicuro’ (OMS) [Navy: Change of Command at the Operation ‘Safe Sea’ (WHO)],” ForzeArmate.org [ArmedFoprces.org], December 29, 2021, https://www.forzearmate.org/marina-militare-cambio-comando-alloperazione-mare-sicuro-oms/ (accessed June 4, 2022). 388. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 122, and Italian Ministry of Defence, Army, “International Operations: Bilateral Mission of Assistance and Support in Libya (MIASIT),” 2019, https://www.esercito.difesa.it/en/Operations/international-operations/ Pagine/Libya-MIL.aspx (accessed June 4, 2022). 389. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Maritime Command, “Standing NATO Maritime Group Two (SNMG2)”; Associated Press, “Live Updates: Italy Formally Approves NATO Contingents,” The Denver Post, February 25, 2022, https://www.denverpost.com/2022/02/25/live-updates-italyformally-approves-nato-contingents/ (accessed May 23, 2022); International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 122; and news release, “Secretary General Praises Italy for Major Role in NATO,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, last updated November 18, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_188662.htm?selectedLocale=en (accessed June 5, 2022). 390. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 122. 391. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Kosovo Force, “Kosovo Force (KFOR): Key Facts and Figures.” 392. Tayfun Ozberk, “Italy Plans to Send Two MCM Vessels to Romania to Tackle Mine Threat,” Naval News, April 1, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/ naval-news/2022/04/italy-plans-to-send-two-mcm-vessels-to-romania/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 393. LETA [Latvian Information Agency], Baltic News Service, TBT Staff, “Italy, Germany to Continue NATO’s Baltic Air-Policing Mission for Another 3 Months,” The Baltic Times, December 29, 2020, https://www.baltictimes.com/italy__germany_to_continue_nato_s_baltic_air-policing_ mission_for_another_3_months/ (accessed June 5, 2022), and David Cenciotti, “The Italian F-35As Have Deployed to Estonia for NATO’s Baltic Air Policing Mission,” The Aviationist, April 30, 2021, https://theaviationist.com/2021/04/30/italian-f35-estonia/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 394. Cenciotti, “The Italian F-35As Have Deployed to Estonia for NATO’s Baltic Air Policing Mission.” 395. Blog Before Flight, “Italian Air Force Completes Record Participation in NATO Baltic Air Policing Mission,” December 5, 2021, https://www. blogbeforeflight.net/2021/12/italian-air-force-nato-baltic-air-policing.html (accessed June 5, 2022). 396. News release, “Italian Eurofighter Detachment Take Over Responsibility for Enhanced Air Policing in Romania from the Royal Canadian Air Force,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Air Command, December 16, 2021, https://ac.nato.int/archive/2021/italian-eurofighter-detachmenttake-over-responsibility-for-enhanced-air-policing-in-romania-from-the-royal-canadian-air-force (accessed June 5, 2021). 397. News release, “Italian Eurofighters to Enhance Air Policing Capabilities over Romania,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Air Command, April 29, 2019, https://ac.nato.int/archive/2019/italian-eurofighters-enhance-air-policing-capabilities-over-romania (accessed June 5, 2022). 128 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 398. News release, “Air Policing in Iceland. New Italian Air Patrol Operation,” Embassy of Italy, Oslo, June 12, 2020, https://amboslo.esteri.it/ ambasciata_oslo/en/ambasciata/news/dall_ambasciata/2020/06/air-policing.html#:~:text=Six%20F%2D35A%20fighters%20of,last%20for%20 about%20two%20months (accessed June 5, 2022). 399. Daniel Kochis, “Poland: The Lynchpin of Security on NATO’s Front Lines,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 4455, August 17, 2015, http://www. heritage.org/research/reports/2015/08/poland-the-lynchpin-of-security-on-natos-front-lines. 400. Agence France-Presse, “Near Ukraine Border, Western Arms Arrive Quickly and Discreetly,” France 24, March 4, 2022, https://www.france24.com/ en/live-news/20220304-near-ukraine-border-western-arms-arrive-quickly-and-discreetly (accessed June 5, 2022). 401. Michael Gabriel Hernandez, “US Patriot Batteries Deployed to Poland amid Russia’s War on Ukraine: Official,” Anadolu Agency [Ankara, Turkey], March 9, 2022, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/us-patriot-batteries-deployed-to-poland-amid-russias-war-on-ukraine-official/2529646 (accessed June 5, 2022). 402. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 135. 403. Christian Davies, “New Polish Military Force Worries Political Opposition,” Politico, November 16, 2016, http://www.politico.eu/article/new-polishmilitary-force-worries-political-opposition/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 404. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2020, p. 79. 405. Błaszczak, “Poland’s Defense Minister: Making the Constant Effort to Strengthen Defense.” 406. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2021, p. 132. The 2022 edition of The Military Balance confirms both the endstrength objective and the number of brigades. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, pp. 135 and 136. 407. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2018: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2018), p. 135, and Charlie Gao, “This Is How Poland Plans to Fight Russia in a War,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, March 3, 2018, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/how-poland-plans-fight-russia-war-24731 (accessed June 5, 2022). 408. Mariusz Blaszczak, “Poland’s Defense Minister: COVID-19 Is Forcing the Military to Reexamine Its Role,” Defense News, January 11, 2021, https://www. defensenews.com/outlook/2021/01/11/polands-defense-minister-covid-19-is-forcing-the-military-to-reexamine-its-role/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 409. Associated Press, “Poland Launches Cybersecurity Military Unit,” The Seattle Times, updated February 9, 2022, https://www.seattletimes.com/ business/technology/poland-launches-cybersecurity-military-unit/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 410. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2022), p. 3. 411. Republic of Poland, National Security Strategy of the Republic of Poland, 2020, p. 18, https://www.bbn.gov.pl/ftp/dokumenty/National_Security_ Strategy_of_the_Republic_of_Poland_2020.pdf (accessed June 5, 2022). 412. “Poland’s Lower House of Parliament Approves Law to Increase Military,” The Kyiv Independent, March 12, 2022, https://kyivindependent.com/ uncategorized/polands-lower-house-of-parliament-approves-law-to-increase-military/ (accessed June 5, 2022); Reuters, “Poland to Ramp up Defense Spending, Army as Ukraine War Rages,” March 3, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/poland-ramp-up-defence-spendingarmy-ukraine-war-rages-2022-03-03/ (accessed June 5, 2022); and Ana-Roxana Popescu, “Poland to Increase Defence Spending to 3% of GDP from 2023,” Janes, March 4, 2022, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/poland-to-increase-defence-spending-to-3-of-gdpfrom-2023 (accessed June 5, 2022). 413. Jacek Siminski, “Polish MoD Adopts a New Technical Modernization Plan—Air Domain Focus. F-35 Top Priority,” The Aviationist, October 14, 2019, https://theaviationist.com/2019/10/14/polish-mod-adopts-a-new-technical-modernization-plan-air-domain-focus-f-35-top-priority/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 414. Aaron Mehta, “Poland, Canada Join NATO Members in Potential Maritime Surveillance Aircraft Buy,” Defense News, February 15, 2018, https:// www.defensenews.com/smr/munich-security-forum/2018/02/15/poland-canada-join-nato-members-in-potential-maritime-surveillanceaircraft-buy/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 415. Lidia Kelly, “Poland Signs $4.75 Billion Deal for U.S. Patriot Missile System Facing Russia,” Reuters, March 28, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/ article/us-raytheon-poland-patriot/poland-united-states-sign-4-75-billion-deal-on-patriot-missiles-idUSKBN1H417S (accessed June 5, 2022), and Staff Sgt. Andrew Mallett, “U.S. and Poland Continue to Grow Air Defense Powerhouse,” U.S. Army, August 20, 2020, https://www.army.mil/ article/238302/u_s_and_poland_continue_to_grow_air_defense_powerhouse (accessed June 5, 2022). 416. Associated Press, “Poland to Pay $414M for US-Made Rocket Launching System,” February 10, 2019, https://www.apnews. com/573c2f35ffea4cbfb65edb90aa22c0ff (accessed June 5, 2022). 417. Jarosław Adamowski, “Poland Acquires AW101 Helos for Navy Under $430M Deal,” Defense News, April 29, 2019, https://www.defensenews.com/ global/europe/2019/04/29/poland-acquires-aw101-helos-for-navy-under-430m-deal/?utm_source=clavis (accessed June 5, 2022). 418. “Poland Finalizes Negotiations to Buy FGM-148 Javelin Antitank Missiles,” Army Recognition, April 22, 2020, https://www.armyrecognition.com/ april_2020_news_defense_global_security_army_industry/poland_finalizes_negotiations_to_buy_fgm-148_javelin_antitank_missiles.html (accessed June 5, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 129 419. Jaroslaw Adamowski, “Poland Inks $4.6 Billion Contract for F-35 Fighter Jets,” Defense News, January 31, 2020, https://www.defensenews. com/global/europe/2020/01/31/poland-inks-46-billion-contract-for-f-35-fighter-jets/ (accessed July 3, 2021); David Axe, “Report: Poland Is Buying 32 F-35 Fighters (And Russia Won’t Like It),” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, May 21, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/ report-poland-buying-32-f-35-fighters-and-russia-wont-it-58742 (accessed July 3, 2021); David Donald, “Poland to Receive C-130Hs, Announces F-35 Base,” AINonline, April 15, 2021, https://www.ainonline.com/aviation-news/defense/2021-04-15/poland-receive-c-130hs-announces-f-35base#:~:text=Poland's%20Minister%20of%20National%20Defense,Martin%20C%2D130H%20Hercules%20turboprops (accessed June 5, 2022); and Lockheed Martin, Global Enterprise, Poland, “F-35: A Dominant Capability For the 21st Century (Poland),” https://www.f35.com/f35/globalenterprise/poland.html (accessed June 5, 2022). 420. Jacek Siminski, “Poland Signs Excess Defense Article Deal Procuring Five Extra C-130Hs (Resurrected from the ‘Boneyard’),” The Aviationist, April 14, 2021, https://theaviationist.com/2021/04/14/poland-signs-excess-defense-article-deal-procuring-five-extra-c-130hs-resurrected-from-theboneyard/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 421. Jaroslaw Adamowski, “Polish Defence Ministry Confirms Plan to Buy M1 Abrams Tanks,” Defense News, July 14, 2021, https://www.defensenews. com/land/2021/07/14/polish-defence-ministry-confirms-plan-to-buy-m1-abrams-tanks/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 422. Jaroslaw Adamowski, “Poland Will Get a New Air-Defense System After the Summer,” Defense News, April 14, 2022, https://www.defensenews. com/global/europe/2022/04/14/poland-will-get-a-new-air-defense-system-after-the-summer/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 423. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Resolute Support Mission, “Resolute Support Mission (RSM): Key Facts and Figures.” 424. News release, “Polish Air Force Starts Baltic Air Policing Mission in Lithuania,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Air Command, December 1, 2021, https://ac.nato.int/archive/2021/polish-air-force-starts-baltic-air-policing-mission-in-lithuania- (accessed June 5, 2022). 425. PAP [Polish Press Agency], “Poland Joins NATO’s Air Policing Mission in Iceland,” The First News, August 2, 2021, https://www.thefirstnews.com/ article/poland-joins-natos-air-policing-mission-in-iceland-23714 (accessed June 5, 2022). 426. News release, “Poland Takes Charge of NATO High Readiness Force,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, December 30, 2019, https://www.nato. int/cps/en/natohq/news_172334.htm (accessed June 5, 2022). 427. Factsheet, “NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence,” and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Kosovo Force, “Kosovo Force (KFOR): Key Facts and Figures.” 428. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 137. 429. Republic of Poland, Ministry of National Defence, “Polish Armed Forces in the TAMT Mission in Turkey,” https://www.gov.pl/web/nationaldefence/polish-armed-forces-in-the-tamt-mission-in-turkey (accessed June 5, 2022). 430. Republic of Poland, Ministry of National Defence, “PMC Romania,” https://www.gov.pl/web/national-defence/pmc-romania (accessed June 5, 2022), and International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 137. 431. Factsheet, “NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence,” and Michal Hudec, “Slovak Government Approves Deployment of NATO Troops,” Euractiv, March 10, 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/slovak-government-approves-deployment-of-nato-troops/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 432. France 24, “Turkey Marks Fifth Anniversary of Failed Coup that Prompted Sweeping Crackdown,” July 15, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/ europe/20210715-turkey-marks-fifth-anniversary-of-failed-coup-against-erdogan (accessed June 3, 2022). 433. Noah Blaser, “‘We Fell Off the Face of the Earth,’” Foreign Policy, August 8, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/08/08/turkey-prison-complexerdogan/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 434. France 24, “Turkey Marks Fifth Anniversary of Failed Coup that Prompted Sweeping Crackdown,” and International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2020, p. 82. 435. Al Jazeera, “Turkey Arrests 10 Retired Admirals over Government Criticism,” April 5, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/5/turkeyissues-arrest-warrants-over-retired-admirals-open-letter (accessed June 3, 2022). 436. Dario Leone, “Turkey Could Soon Train Its Fighter Pilots on Qatar’s Rafales to Learn How to Counter Greek Rafales,” The Aviation Geek Club, December 21, 2021, https://theaviationgeekclub.com/turkey-could-soon-train-its-fighter-pilots-on-qatars-rafales-to-learn-how-to-countergreek-rafales/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 437. Abdullah Bozkurt, “Turkish Air Force Crippled After Mass Purge of Pilots by Erdoğan Government,” Nordic Monitor, January 13, 2020, https:// www.nordicmonitor.com/2020/01/the-turkish-air-force-crippled-after-mass-purge-of-pilots-by-erdogan-government/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 438. Michael Peck, “Turkey: How One Country Destroyed Their Own Air Force,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, January 2, 2020, https:// nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/turkey-how-one-country-destroyed-their-own-air-force-110581 (accessed June 3, 2022). 439. Bozkurt, “Turkish Air Force Crippled After Mass Purge of Pilots by Erdoğan Government.” 440. Michael Peck, “Bad Idea: In 2016, Turkey Destroyed Its Own Air Force,” The National Interest, The Reboot Blog, March 18, 2021, https:// nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/bad-idea-2016-turkey-destroyed-its-own-air-force-180427 (accessed June 3, 2022). 130 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 441. Abdullah Bozkurt, “Turkey Failed to Convince Russia to Share Missile Technology, Agree to Co-production,” Nordic Monitor, December 29, 2021, https://nordicmonitor.com/2021/12/turkey-failed-to-convince-russia-to-share-missile-technology-co-production/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 442. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2020, p. 82. Turkey has pushed ahead with this acquisition. The 2022 edition of The Military Balance notes tension with NATO allies because of this acquisition and reports that Turkey now has 32 S-400 missiles in its inventory. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, pp. 155 and 157. 443. Aaron Mehta, “Turkey Officially Kicked Out of F-35 Program, Costing US Half a Billion Dollars,” Defense News, July 17, 2019, https://www. defensenews.com/air/2019/07/17/turkey-officially-kicked-out-of-f-35-program/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 444. Burak Ege Bekdil, “Turkey Transports S-400 Air Defense System for Black Sea Tests,” Defense News, October 9, 2020, https://www.defensenews. com/training-sim/2020/10/09/turkey-transports-s-400-air-defense-system-for-black-sea-tests/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 445. Amanda Macias, “U.S. Sanctions Turkey over Purchase of Russian S-400 Missile System,” CNBC, updated December 15, 2020, https://www.cnbc. com/2020/12/14/us-sanctions-turkey-over-russian-s400.html (accessed June 3, 2022). 446. “US Sanctions on Turkish Officials over S-400s Come into Force,” Daily Sabah, April 6, 2021, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/ussanctions-on-turkish-officials-over-s-400s-come-into-force (accessed June 3, 2022). 447. Thomas Newdick, “Turkish F-16 Knocks Down Target Drone with New Indigenous Air-to-Air Missile,” The War Zone, April 15, 2021, https://www. thedrive.com/the-war-zone/40193/turkish-f-16-knocks-down-target-drone-with-new-indigenous-air-to-air-missile (accessed May 27, 2022). 448. David Welna, “U.S.–Turkey Standoff over F-35 Escalates as Each Side Waits for the Other to Blink,” NPR, April 3, 2019, https://www.npr. org/2019/04/03/709222963/u-s-turkey-standoff-over-f-35-escalates-as-each-side-waits-for-the-other-to-blin (accessed May 27, 2022), and Burak Ege Bekdil, “How Turkey’s Industry Could Suffer from the S-400 Deal with Russia,” Defense News, April 11, 2019, https://www.defensenews. com/industry/2019/04/11/how-turkeys-industry-could-suffer-from-the-s-400-deal-with-russia/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 449. According to the GAO, “the F-35 program office and the prime contractors have identified and are contracting with alternative suppliers to produce the 1,005 parts that are currently made in Turkey.” U.S. Government Accountability Office, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter: DOD Needs to Update Modernization Schedule and Improve Data on Software Development, GAO-21-226, March 2021, p. 5, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21226.pdf (accessed May 27, 2022). 450. Valerie Insinna, “Turkey’s Removal from F-35 Program to Cause Hike in Engine Price,” Defense News, April 23, 2021, https://www.defensenews. com/air/2021/04/23/turkeys-removal-from-f-35-program-to-cause-hike-in-engine-price/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 452. Wolters, statement before Senate Armed Services Committee, March 29, 2022, p. 19. 453. Dorian Jones, “Turkey Steps Up Support for Ukraine, Risking Russian Retaliation,” Voice of America, March 3, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/ turkey-steps-up-support-for-ukraine-risking-russian-retaliation-/6468635.html (accessed June 3, 2022). 454. Heather Mongilio, “Turkey Closes Bosphorus, Dardanelles Straits to Warships,” U.S. Naval Institute News, February 28, 2022, https://news.usni. org/2022/02/28/turkey-closes-bosphorus-dardanelles-straits-to-warships (accessed May 27, 2022). 455. Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas, “Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. R41368, updated November 9, 2020, p. 29, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/R41368.pdf (accessed June 3, 2022). 456. Humeyra Pamuk, “U.S. Says Potential F-16 Sale to Turkey Would Serve U.S. Interests, NATO—Letter,” Reuters, April 7, 2022, https://www.reuters. com/world/us-says-potential-f-16-sale-turkey-would-serve-us-interests-nato-letter-2022-04-06/ (accessed June 3, 2022). 457. Humeyra Pamuk and Andrea Shalal, “Biden Administration Throws Support Behind Potential F-16 Sale to Turkey,” Reuters, June 29, 2022, https:// www.reuters.com/world/biden-administration-throws-support-behind-potential-f-16-sale-turkey-2022-06-29/ (accessed June 29, 2022). See also Jared Szuba, “Pentagon ‘Fully Supports’ F-16 Sale to Turkey,” Al-Monitor, June 30, 2022, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/06/ pentagon-fully-supports-f-16-sale-turkey (accessed July 6, 2022). 458. Ahval, “Fate of Turkish Air Force May Resemble Iran’s—Analyst,” February 10, 2021, https://ahvalnews.com/turkey-military/fate-turkish-air-forcemay-resemble-irans-analyst (accessed June 3, 2022). 459. Kemal Kirisçi, “As EU–Turkey Migration Agreement Reaches the Five-Year Mark, Add a Job Creation Element,” The Brookings Institution, Order from Chaos Blog, March 17, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/03/17/as-eu-turkey-migration-agreement-reachesthe-five-year-mark-add-a-job-creation-element/ (accessed June 15, 2022), and Vice Admiral Patrick Chevallereau, “The Worm Is in the Fruit: A Rising Strategic Foe Inside NATO,” RUSI [Royal United Services Institute] Europe Commentary, July 31, 2020, https://rusi.org/explore-ourresearch/publications/commentary/worm-fruit-rising-strategic-foe-inside-nato (accessed June 3, 2022). 460. Al Jazeera, “Twelve Refugees Found Frozen to Death near Turkey–Greece Border,” February 3, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/ news/2022/2/3/12-migrants-found-frozen-to-death-near-turkey-greece-border (accessed June 3, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 131 451. Umut Uras, “Analysis: Turkey’s New S-400 Proposal Offers Olive Branch to US,” Al Jazeera, February 10, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/ news/2021/2/10/turkey-proposes-model-to-resolve-s-400-dispute-with-us (accessed June 3, 2022), and “Turkey Says Idea to Send Its S-400s to Ukraine ‘Quite Unrealistic,’” Daily Sabah, March 24, 2022, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/defense/turkey-says-idea-to-send-its-s400s-to-ukraine-quite-unrealistic (accessed June 3, 2022). 461. Associated Press, “Leaders of Turkey, Greece Hold Talks in Rare Meeting,” U.S. News & World Report, March 13, 2022, https://www.usnews.com/ news/business/articles/2022-03-13/leaders-of-turkey-greece-hold-talks-in-rare-meeting (accessed June 3, 2022). 462. Nikos Stelgias, “Kibris Postasi: Plan for a Turkish Naval Base in Karpasia,” News in Cyprus, October 18, 2021, http://www.newsincyprus.com/ news/351462/kibris-postasi-plan-for-a-turkish-naval-base-in-karpasia (accessed May 23, 2022), and Reuters, “Turkish Drones Escorting Drill Ships to Fly from Turkish Cypriot Airport: Report,” December 13, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-defence-cyprus/turkishdrones-escorting-drill-ships-to-fly-from-turkish-cypriot-airport-report-idUSKBN1YH2DZ (accessed June 3, 2022). 463. Associated Press, “Turkey’s Drone Base in Northern Cyprus Hightens [sic] Regional Tensions,” Haaretz, August 25, 2021, https://www.haaretz. com/middle-east-news/turkey/turkey-s-drone-base-in-northern-cyprus-hightens-regional-tensions-1.10149930 (accessed June 3, 2022). 464. Sakshi Tiwari, “Rafale Fighter Jets: Turkey to Train Its Pilots on French-Origin Warplane Operated by Qatari Air Force—Reports,” The EurAsian Times, December 22, 2021, https://eurasiantimes.com/rafale-fighter-jets-turkey-could-train-its-pilots-operated-by-qatar-air-force/ (accessed June 15, 2022); Ragip Soylu, “Qatar to Train Air Force in Turkey Under New Deal,” Middle East Eye, July 1, 2021, https://www.middleeasteye.net/ news/turkey-qatar-military-training-airforce-agreement (accessed May 23, 2022); and Leone, “Turkey Could Soon Train Its Fighter Pilots on Qatar’s Rafales to Learn How to Counter Greek Rafales.” 465. Dorian Jones, “US Military Base in Turkey Has Uncertain Future,” Voice of America, November 26, 2019, https://www.voanews.com/europe/usmilitary-base-turkey-has-uncertain-future (accessed June 3, 2022). 466. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Airborne Early Warning and Control Force, “FOB Konya,” https://awacs.nato.int/organisation/forwardoperating-bases--location/fob-konya (accessed June 3, 2022), and Kalev Stoicescu and Hille Hanso, “Turkey’s Future Role in NATO: An Indispensable and Difficult Ally,” International Center for Defence and Security Policy Paper, January 2022, p. 9, https://icds.ee/wp-content/ uploads/2022/01/ICDS_Policy_Paper_Turkey%C2%B4s_Future_Role_in_NATO_Stoicescu_Hanso_January_2022-1.pdf (accessed June 3, 2022). 467. Infographic, “NATO Ballistic Missile Defence Architecture as of 2019,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/ assets/pictures/2016_07_160711a-infographics-bmd/20170907_170907-bmd03.jpg (accessed July 3, 2021), and Joseph Trevithick, “The U.S. Army Wants to Expand a Secretive Missile Defense Site in Turkey,” The War Zone, May 25, 2017, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/10638/ the-u-s-army-wants-to-expand-a-secretive-missile-defense-site-in-turkey (accessed May 27, 2022). 468. News release, “Turkey Takes Charge of NATO High Readiness Force,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, last updated December 30, 2020, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_180627.htm (accessed June 5, 2022). 469. News release, “Turkey Continues Its Efforts for Afghanistan’s Lasting Security, Through the NATO-Led Resolute Support Mission,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, last updated March 31, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_182914.htm?selectedLocale=en (accessed June 3, 2022). 470. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Kosovo Force, “Kosovo Force (KFOR): Key Facts and Figures.” 471. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Maritime Command, “Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group One (SNMCMG2), and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Maritime Command, “Standing NATO Maritime Group Two (SNMG2).” 472. Ed Adamczyk, “Turkish F-16s, Troops Join NATO Air Policing,” United Press International, July 7, 2021, https://www.upi.com/DefenseNews/2021/07/07/nato-turkey-poland-airpolicing/8551625672900/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 473. Mongilio, “Turkey Closes Bosphorus, Dardanelles Straits to Warships,” and Brad Lendon, “Russian Warship Sinks in the Black Sea After Ukraine Claims It Was Hit by a Missile,” CNN, updated April 14, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/04/14/europe/russia-navy-cruiser-moskva-fireabandoned-intl-hnk-ml/index.html (accessed June 5, 2022). 474. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 155. 475. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2020: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2020), p. 81. 476. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2022), p. 3. 477. Benjamin Brimelow, “Turkey Is Building New Ships, Tanks, and Missiles to Boost Its Military and Send a Message to the Rest of NATO,” Business Insider, August 6, 2021, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/turkey-is-building-new-ships-tanks-and-missiles-to-boost-its-military-andsend-a-message-to-the-rest-of-nato/ar-AAN0SR (accessed June 5, 2022). 478. Ibid. 479. Ashish Dangwal, “The ‘Power of Panther’—Dumped by France & Germany, Turkey’s Long-Delayed Altay Main Battle Tanks Get Korean Thrust,” The EurAsian Times, March 18, 2022, https://eurasiantimes.com/turkeys-long-delayed-altay-tanks-to-get-s-korean-engine/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 480. Burak Ege Bekdil, “Turkey to Export T129 Helos to Philippines Despite Block on Pakistani Order,” Defense News, May 25, 2021, https://www. defensenews.com/air/2021/05/25/turkey-to-export-t129-helos-to-philippines-despite-block-on-pakistani-order/ (accessed June 5, 2022). 481. Gastón Dubois, “Pakistan Cancels Purchase of Turkish T129 ATAK Helicopters, and Seeks Replacement from China,” Aviacionline, January 5, 2022, https://www.aviacionline.com/2022/01/pakistan-cancels-purchase-of-turkish-t129-atak-helicopters-and-seeks-replacement-from-china/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 132 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 482. Bekdil, “Turkey to Export T129 Helos to Philippines Despite Block on Pakistani Order.” 483. Linda Kay, “Ukrainian-Origin ATAK-II Helicopter Engines to Be Produced in Turkey,” Defense World, posted February 23, 2022, https://www. defenseworld.net/2022/02/23/ukrainian-origin-atak-ii-helicopter-engines-to-be-produced-in-turkey.html (accessed June 17, 2022). 484. Sevil Erkuş, “France ‘Hampers Eurosam Missile System Due to Political Reasons,’” Hürriyet Daily News, January 6, 2020, https://www. hurriyetdailynews.com/france-hampers-eurosam-missile-system-due-to-political-reasons-150657 (accessed June 7, 2022). 485. Selcan Hacaoglu, Firat Kozok, and Ania Nussbaum, “Turkey Pushes Macron to Allow Purchase of Missile System,” Financial Post, September 25, 2020, https://financialpost.com/pmn/business-pmn/turkey-pushes-macron-to-allow-purchase-of-missile-system (accessed June 7, 2022). 486. “Turkey, France, Italy to Revive Steps on SAMP/T Missiles: Erdoğan,” Daily Sabah, March 25, 2022, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/ defense/turkey-france-italy-to-revive-steps-on-sampt-missiles-erdogan (accessed June 7, 2022). 487. Sakshi Tiwari, “Turkey’s 5th-Gen TF-X Stealth Fighter Jet to Be Rolled Out by 2025; Mega Engineering Complex Inaugurated,” The EurAsian Times, January 10, 2022, https://eurasiantimes.com/turkey-tf-x-stealth-fighter-jet-in-3-years-opens-complex/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 488. Tayfun Ozberk, “Turkey Floats Out Its First AIP Submarine ‘Piri Reis,’” Naval News, March 25, 2021, https://www.navalnews.com/navalnews/2021/03/turkey-floats-out-its-first-aip-submarine-piri-reis/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 489. Xavier Vavasseur, “Turkish Industry to Conduct Mid-life Upgrade of Preveze-Class Submarines,” Naval News, February 10, 2019, https://www. navalnews.com/naval-news/2019/02/turkish-industry-to-conduct-mid-life-upgrade-of-preveze-class-submarines/?nowprocket=1 (accessed June 7, 2022). 490. “STM Completes Sea Trials of Turkish Preveze-Class Modernized Submarines,” Navy Recognition, February 14, 2022, https://www.navyrecognition. com/index.php/naval-news/naval-news-archive/2022/february/11398-stm-completes-sea-trials-of-turkish-preveze-class-modernizedsubmarines.html (accessed June 7, 2022). 491. “Turkey Launches Test and Evaluation Ship TCG Ufuk,” Naval Today, February 11, 2019, https://navaltoday.com/2019/02/11/turkey-launches-testand-evaluation-ship-tcg-ufuk/ (accessed June 7, 2022), and Can Kasapoglu, “‘The Blue Homeland’: Turkey’s Largest Naval Drill,” Anadolu Agency [Ankara, Turkey], February 27, 2019, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/-the-blue-homeland-turkey-s-largest-naval-drill/1404267 (accessed June 7, 2022). 492. Press release, “Serial Production of Turkey’s Hurjet Not Enough to Help Meet 2023 Indigenous Production Goal, Says GlobalData,” GlobalData, January 19, 2022, https://www.globaldata.com/serial-production-turkeys-hurjet-not-enough-help-meet-2023-indigenous-production-goal-saysglobaldata/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 494. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022), p. 3. 495. Jaroslaw Adamowski, “Estonia Increases Defense Spending to Buy Air Defense Systems, More Weapons,” Defense News, March 25, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/03/25/estonia-increases-defense-spending-to-buy-air-defense-systems-more-weapons/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 496. ERR [Estonian Public Broadcasting], “Estonia Signs Contract for Coastal Defense System Acquisition,” October 6, 2021, https://news.err. ee/1608361155/estonia-signs-contract-for-coastal-defense-system-acquisition (accessed June 7, 2022). 497. Republic of Estonia, Ministry of Defence, “National Defence Development Plan 2031,” last updated December 14, 2021, https://kaitseministeerium. ee/en/national-defence-development-plan-2031 (accessed June 7, 2022). 498. Georgia Wilson, “Estonia Announces Largest Defense Procurement Worth US$794mn,” Procurement, February 7, 2022, https://procurementmag. com/procurement-strategy/estonia-announces-largest-defence-procurement-worth-us-794mn (accessed June 7, 2022). 499. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 100. 500. Simon Newton, “Why NATO’s Military Might Is Focused on Estonia,” Forces.net, May 11, 2015, https://www.forces.net/news/tri-service/why-natosmilitary-might-focused-estonia (accessed June 7, 2022). 501. Republic of Estonia, Ministry of Defence, “National Defence Development Plan 2031.” 502. ERR [Estonian Public Broadcasting], “Paper: More Military Equipment to Be Bought from South Korea,” October 3, 2019, https://news.err. ee/987854/paper-more-military-equipment-to-be-bought-from-south-korea (accessed June 7, 2022). 503. “Estonia Receives First K9 Howitzers from South Korea,” Defense Brief, October 10, 2020, https://defbrief.com/2020/10/10/estonia-receives-firstk9-howitzers-from-south-korea/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 504. ERR [Estonian Public Broadcasting], “Finland and Latvia to Build Armored Vehicles Together,” January 10, 2021, https://news.err.ee/1234201/ finland-and-latvia-to-build-armored-vehicles-together (accessed June 7, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 133 493. Burak Ege Bekdil, “Turkey Reports 17% Drop in Defense Exports,” Defense News, January 19, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/ europe/2021/01/19/turkey-reports-nearly-15-drop-in-defense-exports/ (accessed June 7, 2022), and “Turkey’s Defense Industry Targets More than $4 billion in Exports This Year: Official,” Hürriyet Daily News, March 6, 2022, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkeys-defense-industrytargets-more-than-4-billion-in-exports-this-year-official-172005 (accessed June 7, 2022). 505. Gareth Jennings, “Estonia Receives First of Two Donated C-145As,” Janes, March 19, 2019, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/ estonia-receives-first-of-two-donated-c-145as (accessed June 7, 2022). 506. Paul McLeary, “Estonia Inks ‘Big’ New US Defense Deal, Eyes on Russia,” Breaking Defense, July 9, 2019, https://breakingdefense.com/2019/07/ estonia-inks-big-us-defense-deal-eyes-on-russia/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 507. Monica M. Ruiz, “To Bolster Cybersecurity, the US Should Look to Estonia,” Wired, February 14, 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/opinion-tobolster-cybersecurity-the-us-should-look-to-estonia/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 508. Eric Tucker, “US, Estonia Partnered to Search out Cyber Threat from Russia,” Associated Press, December 3, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/ hacking-russia-estonia-e931e674091b080f7a01642b01729bbe (accessed June 7, 2022). 509. News release, “Dept. of Defense’s Largest Multinational Cyber Exercise Yet Focuses on Collective Defense,” U.S. Cyber Command, December 3, 2021, https://www.cybercom.mil/Media/News/Article/2861207/dept-of-defenses-largest-multinational-cyber-exercise-yet-focuses-on-collective/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 510. News release, “Signing of Defense Cooperation Agreement—Remarks by Ambassador James D. Melville,” U.S. Embassy in Estonia, January 17, 2017, https://ee.usembassy.gov/signing-defense-cooperation-agreement-remarks-ambassador-james-d-melville/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 511. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Resolute Support Mission, “Resolute Support Mission (RSM): Key Facts and Figures”; North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group One (SNMCMG1)”; and Gregoire Lory, “EU’s Takuba Military Taskforce in Sahel Caught Between France and Mali,” Euronews, updated March 2, 2022, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/02/03/eu-s-takubamilitary-taskforce-in-sahel-caught-between-france-and-mali#:~:text=Takuba%20was%20set%20up%20in,the%20jihadist%20advance%20in%20 Mali (accessed June 7, 2022). 512. Republic of Estonia, Defence Forces, “Operations Abroad,” last updated July 23, 2021, https://mil.ee/en/defence-forces/operations-abroad/#tnato-mission-iraq-nmi (accessed June 7, 2022). 513. James Tasamba, “Estonia to Withdraw Its Troops from Mali,” Anadolu Agency [Ankara, Turkey], February 15, 2022, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/ africa/estonia-to-withdraw-its-troops-from-mali/2502729 (accessed June 7, 2022). 514. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 122. 515. Ibid., p. 123; North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Resolute Support Mission, “Resolute Support Mission (RSM): Key Facts and Figures”; press release, “Saeima Extends Participation of Latvian Troops in International Coalition Military Operation ‘Inherent Resolve,’” Latvijas Republikas Saeima [Parliament of the Republic of Latvia], March 17, 2022, https://www.saeima.lv/en/news/saeima-news/30783-saeima-extendsparticipation-of-latvian-troops-in-international-coalition-military-operation-inherent-resolve?phrase=iraq (accessed June 7, 2022); and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Kosovo Force, “Kosovo Force (KFOR): Key Facts and Figures.” 516. Republic of Latvia, Ministry of Defence, The State Defence Concept, approved by the Cabinet of Ministers on August 18, 2020, and adopted by the Saeima [Parliament of the Republic of Latvia] on September 24, 2020, p. 24, https://www.mod.gov.lv/sites/mod/files/document/ Valsts%20aizsardzibas%20koncepcija_ENG_0.pdf (accessed June 7, 2022). See also news release, “Saeima Approves the National Defence Concept,” Republic of Latvia, Ministry of Defence, September 28, 2020, https://www.mod.gov.lv/en/news/saeima-approves-national-defenceconcept#:~:text=National%20Guard%20are%20indispensable%20to,long%2Dterm%20protection%20of%20Latvia (accessed June 7, 2022). 517. Viktors Domburs, “Latvia: Armed to the Teeth,” The Independent, December 8, 2019, https://www.theindependentbd.com/arcprint/ details/226969/2019-12-08 (accessed June 7, 2022), and news release, “Latvia Plans to Invest the Average of €50 Million a Year in the Development of Military Infrastructure over the Next Four Years,” Republic of Latvia, Ministry of Defence, February 26, 2019, https://www.mod. gov.lv/en/news/latvia-plans-invest-average-eu50-million-year-development-military-infrastructure-over-next (accessed June 7, 2022). 518. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” p. 3. 519. LETA [Latvian National News Agency], “Latvian Government Confirms Increased Defense Spend,” March 30, 2022, https://eng.lsm.lv/article/ society/defense/latvian-government-confirms-increased-defense-spend.a450233/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 520. Staff Sgt. Tristan Viglianco, “Michigan National Guard Trains First Latvian UH-60 Black Hawk Maintainer,” U.S. Air Forces in Europe & Air Forces Africa, December 17, 2021, https://www.usafe.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2877557/michigan-national-guard-trains-first-latvian-uh-60black-hawk-maintainer/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 521. Military Leak, “Latvian National Armed Forces Takes Delivery of New Spike Precision-Guided Tactical Missiles,” February 24, 2020, https://militaryleak. com/2020/02/24/latvian-national-armed-forces-takes-delivery-of-new-spike-precision-guided-tactical-missiles/#:~:text=The%20Latvian%20 National%20Armed%20Forces%20purchased%20a%20new%20delivery%20of,Spike%20LR2%2C%20and%20Spike%20ER2 (accessed June 7, 2022). 522. “Latvia Installs Team Trainer for Spike Missiles,” Army Technology, October 9, 2020, https://www.army-technology.com/news/latvia-teamtrainer-spike-missiles/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 523. Eng.lsm.lv [Latvian Public Broadcasting] and ReTV, “Latvia Gets First ‘Patria’ Armored Vehicles,” March 8, 2022, https://eng.lsm.lv/article/society/ defense/latvia-gets-first-patria-armored-vehicles.a446891/ (accessed June 16, 2022). 524. Eng.lsm.lv [Latvian Public Broadcasting] and Linda Spundina, “Latvia–Belarus Border Construction Costs Rise by €15 Million,” March 16, 2022, https://eng.lsm.lv/article/society/defense/latvia-belarus-border-construction-costs-rise-by-15-million.a448215/ (accessed June 16, 2022). 134 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 525. Eng.lsm.lv [Latvian Public Broadcasting] and Dāvids Friedenfelds, “Latvian Border Guard Gets Tactical Vehicles from USA,” eng.lsm.lv, March 9, 2022, https://eng.lsm.lv/article/society/defense/latvian-border-guard-gets-tactical-vehicles-from-usa.a447151/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 526. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 123. 527. LRT [Lithuanian National Television and Radio], “Lithuania Lowers Conscription Age,” December 12, 2019, https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-inenglish/19/1124775/lithuania-lowers-conscription-age#:~:text=Young%20men%20between%2018%20and,called%20up%20for%20military%20 service (accessed June 7, 2022). 528. Graph 3, “Defence Expenditure as a Share of GDP (%),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” and Graph 4, “Equipment Expenditure as a Share of Defence Expenditure (%,),” in press release, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2022),” p. 3. 529. Tim Fish, “As Russia Threatens Ukraine, Baltic Nations Work to Update Armored Vehicle Fleets,” Breaking Defense, January 31, 3022, https:// breakingdefense.com/2022/01/as-russia-threatens-ukraine-baltic-nations-work-to-update-armored-vehicle-fleets/ (accessed July 6, 2022). 530. Sebastian Sprenger, “Lithuania Is First Baltic Nation to Sign US Defense-Cooperation Pact,” Defense News, April 3, 2019, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2019/04/03/lithuania-is-first-baltic-nation-to-sign-us-defense-cooperation-pact/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 531. News release, “U.S., Lithuania Detail Roadmap for Cooperation Through 2024,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 2, 2019, https://www.defense. gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/1803578/us-lithuania-detail-roadmap-for-cooperation-through-2024/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 532. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2021, p. 122. 533. Jim Garamone, “U.S., Lithuania Sign Agreement to Further Military Interoperability,” U.S. Department of Defense, December 13, 2021, https:// www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2871726/us-lithuania-sign-agreement-to-further-military-interoperability/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 534. Jaroslaw Adamowski, “Lithuania Signs Deal for Its First American Military Helicopters,” Defense News, November 13, 2020, https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2020/11/13/lithuania-signs-deal-for-its-first-american-military-helicopters/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 535. Press release, “NASAMS Medium-Range Air Defence System Officially Handed Over to the Lithuanian Armed Forces,” Republic of Lithuania, Ministry of National Defence, October 30, 2020, https://www.defense-aerospace.com/articles-view/release/3/214069/lithuania-takes-deliveryof-nasams-air-defense-system.html (accessed June 5, 2021), and Airforce Technology, “Lithuania to Buy Additional NASAMS Air Defence Missiles from Norway,” January 4, 2019, https://www.airforce-technology.com/news/lithuania-nasams-defence-missiles-norway/ (accessed June 1, 2022). 536. Baltic News Service, “Lithuanian Military to Purchase More Javelin Missiles from US,” LRT [Lithuanian National Television and Radio], March 10, 2022, https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1641039/lithuanian-military-to-purchase-more-javelin-missiles-from-us (accessed June 7, 2022). 537. Joe Saballa, “US Donates $10M in Anti-Tank Weapons to Lithuania,” The Defense Post, April 20, 2021, https://www.thedefensepost. com/2021/04/20/us-donates-lithuania-anti-tank-weapons/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 538. “Lithuania Will Procure 200 US JLTV Joint Light Tactical Vehicles from Oshkosh Defense,” Army Recognition, November 24, 2019, https://www. armyrecognition.com/november_2019_global_defense_security_army_news_industry/lithuania_will_procure_200_us_jltv_joint_light_ tactical_vehicles_from_oshkosh_defense.html (accessed June 7, 2022). 539. Fish, “As Russia Threatens Ukraine, Baltic Nations Work to Update Armored Vehicle Fleets.” 540. Joe Saballa, “Saab Supplying Carl-Gustaf M4 Ammunition to Lithuania,” The Defense Post, January 13, 2022, https://www.thedefensepost. com/2022/01/13/saab-gustaf-m4-lithuania/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 541. Basu, “Where 100,000 US Troops Are Stationed in Europe;” 542. Abraham Mahshie, “What Is EUCOM’s Ukraine Control Center?” Air Force Magazine, April 29, 2022, https://www.airforcemag.com/what-iseucoms-ukraine-control-center/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 543. U.S. European Command, “Commander’s Priorities: Mission,” https://www.eucom.mil/organization/commanders-priorities (accessed June 16, 2022). 544. C. Todd Lopez, “Neptune Strike ’22 Kicks off Monday in Mediterranean,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 21, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/ News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2906812/neptune-strike-22-kicks-off-monday-in-mediterranean/ (accessed June 8, 2022). 545. “NATO Forces Conduct Air Operations with USS Harry S. Truman CSG,” Naval News, March 11, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/navalnews/2022/03/nato-forces-conduct-air-operations-with-uss-harry-s-truman-csg/ (accessed June 8, 2022). 546. U.S. Army Public Affairs, “U.S. Army Europe and Africa Commands Consolidate,” November 20, 2020, https://www.army.mil/article/241094/u_s_ army_europe_and_africa_commands_consolidate (accessed June 8, 2022). See also press release, “US Army Europe, Africa Now Consolidated,” U.S. Army Europe and Africa, November 23, 2020, https://www.europeafrica.army.mil/ArticleViewPressRelease/Article/2424126/press-releaseus-army-europe-africa-now-consolidated/ (accessed June 7, 2022). 547. U.S. Army Europe and Africa, “Fact Sheet: U.S. Army Europe and Africa,” as of March 8, 2021, https://www.europeafrica.army.mil/Portals/19/ documents/Infographics/USAREURAF%20Fact%20Sheet%2003082021.pdf?ver=2RoIT5wSRaHhBRpUz26yvw%3D%3D (accessed July 7, 2022). 548. Kinsey Lindstrom, “Rockets Return to Europe,” U.S. Army, January 10, 2020, https://www.army.mil/article/231553/rockets_return_to_europe (accessed July 7, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 135 549. 10th Army Air & Missile Defense Command, “Units of 10th AAMDC: 5th Battalion, 4th Air Defense Artillery,” https://www.10thaamdc.army.mil/54ADA/ (accessed June 8, 2022). 550. Jen Judson, “US Army’s Short-Range Air Defense Capability Will Grow to a Battalion by Year’s End,” Defense News, March 30, 2022, https://www. defensenews.com/land/2022/03/30/us-armys-short-range-air-defense-capability-will-grow-to-a-battalion-by-years-end/ (accessed June 8, 2022). 551. U.S. Army Europe and Africa, “Fact Sheet: U.S. Army Europe and Africa.” 552. U.S. Air Forces in Europe & Air Forces Africa, “USAFE–AFAFRICA,” https://www.usafe.af.mil/About-Us/Mission-and-Organization/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 553. Fact sheet, “U.S. Air Forces in Europe–Air Forces Africa,” U.S. Air Force, July 2015, https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/ Article/609838/united-states-air-force-in-europe/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 554. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “Germany Arrests Four Tajik Nationals Suspected of Plotting Terrorist Attack,” April 15, 2020, https://www.rferl. org/a/germany-arrests-four-tajik-nationals-suspected-of-plotting-terrorist-attack/30555712.html (accessed June 8, 2022). 555. Brian W. Everstine, “B-1s, B-2s Wrap up European Bomber Task Force Deployment,” Air Force Magazine, https://www.airforcemag.com/b-1s-b-2swrap-up-european-bomber-task-force-deployment/ (accessed June 2, 2022). 556. U.S. Air Forces in Europe and Air Forces Africa, “U.S. Air Force B-2s Return to Europe,” Air Force Global Strike Command, March 10, 2020, https:// www.afgsc.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2106854/us-air-force-b-2s-return-to-europe/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 557. U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Marine Forces Europe and Africa, “About: History,” https://www.marforeur.marines.mil/About/History/ (accessed May 27, 2022). 558. See Military.com, “Marines May Move Even More Combat Gear into Norwegian Caves,” June 16, 2017, https://www.military.com/ defensetech/2017/06/16/marines-combat-gear-norwegian-caves (accessed May 27, 2022). 559. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Exercise Cold Response 2022—NATO and Partner Forces Face the Freeze in Norway,” and Larson, “The U.S. Marine Corps Is Keeping an Eye on Russia and Europe.” 560. Philip Athey, “Marine Corps Ends All 3 of Its Crisis Response Deployments,” Marine Corps Times, March 18, 2022, (accessed June 17, 2022). 561. See, for example, Maj. Cain Claxton, “Response Force Hones Capability in Air–Ground Integration Exercise,” United States Africa Command, December 10, 2021, https://www.africom.mil/article/34235/response-force-hones-capability-in-air-ground-integration-exercise (accessed June 17, 2022), and Maj. Cain Claxton, “AFRICOM Response Force Keeps Skills Sharp,” U.S. Army, February 22, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/254151/ usafricom_response_force_keeps_skills_sharp (accessed June 17, 2022). 562. U.S. Special Operations Command, Fiscal Year 2022 President’s Budget, United States Special Operations Command, May 2021, p. 114, 129 https:// comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2022/budget_justification/pdfs/01_Operation_and_Maintenance/O_M_VOL_1_ PART_1/SOCOM_OP-5.pdf (accessed June 17, 2022). 563. Military Leak, “US Special Forces Open Site in Latvia,” December 5, 2020, https://militaryleak.com/2020/12/05/us-special-forces-openoperations-site-in-latvia/ (accessed June 17, 2022). See also Stavros Atlamazoglu, “NATO Has Opened a New Special Operations Facility in Latvia,” The National Interest, The Reboot Blog, January 14, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/nato-has-opened-new-specialoperations-facility-latvia-199400 (accessed June 17, 2022). 564. Wolters, statement before Senate Armed Services Committee, March 29, 2022, p. 17. 565. Table 3, “EDI Funding by Appropriation,” in U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Department of Defense Budget Fiscal Year (FY) 2023: European Deterrence Initiative,” pp. 28, 31, and 32. 566. Michael Beaton, “MEDDAC Bavaria Reaches East to Romania to Support U.S., Multinational Forces,” U.S. Army, April 17, 2017, https://www.army. mil/article/185409/meddac_bavaria_reaches_east_to_romania_to_support_u_s_multinational_forces (accessed June 8, 2022), and Capt. Moriamo Sulaiman, “Romanian President Welcomes NATO Allied Troops at Mihail Kogalniceanu Airbase,” March 7, 2022, https://www.dvidshub. net/news/416710/romanian-president-welcomes-nato-allied-troops-mihail-kogalniceanu-airbase (accessed June 7, 2022). 136 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Middle East Nicole Robinson S death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 AD.2 Sunni Muslims, who form the majority of the world’s Muslim population, hold power in most of the region’s Arab countries. However, viewing the Middle East’s current instability through the lens of a Sunni–Shia conflict does not reveal the full picture. The cultural and historical division between Arabs and Persians has reinforced the Sunni–Shia split. The mutual distrust between many Sunni Arab powers and Iran, the Persian Shia power, compounded by clashing national and ideological interests, has fueled instability in such countries as Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. Sunni extremist organizations like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) have exploited sectarian and ethnic tensions to gain support by posing as champions of Sunni Arabs against Syria’s Alawite-dominated regime and other non-Sunni governments and movements. Regional demographic trends also are destabilizing factors. The Middle East contains one of the world’s youngest and fastest-growing populations. This would be viewed as an advantage in most of the West, but not in the Middle East. Known as “youth bulges,” these demographic tsunamis have overwhelmed many countries’ inadequate political, economic, and educational infrastructures, and the lack of access to education, jobs, and meaningful political participation fuels discontent. Because almost two-thirds of the region’s inhabitants are less than 30 years old, this demographic bulge will continue to undermine political stability across the region.3 The Middle East has more than half of the world’s oil reserves and is the world’s chief oil-exporting region.4 As the world’s largest producer and consumer of oil,5 the U.S., even though it actually imports relatively little of its oil from the Middle East, has The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 137 trategically situated at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and Africa, the Middle East has long been an important focus of United States foreign policy. U.S. security relationships in the region are built on pragmatism, shared security concerns, and economic interests that include large sales of U.S. arms to help countries in the region to defend themselves. The U.S. also has a long-term interest that derives from the region’s economic importance as the world’s primary source of oil and gas. The region is home to a wide array of cultures, religions, and ethnic groups, including Arabs, Jews, Kurds, Persians, and Turks among others. It also is home to the three Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as well as many smaller religions like the Bahá’í, Druze, Yazidi, and Zoroastrian faiths. The region contains many predominantly Muslim countries as well as the world’s only Jewish state. The Middle East is deeply sectarian, and these long-standing divisions, exacerbated by religious extremists’ constant vying for power, are central to many of its current challenges. In some cases, these sectarian divides have persisted for centuries. Contemporary conflicts, however, have less to do with these histories than they do with modern extremist ideologies and the fact that today’s borders often do not reflect cultural, ethnic, or religious realities. Instead, they are often the results of decisions taken by the British, French, and other powers during and soon after World War I as they dismantled the Ottoman Empire.1 In a way that many in the West do not understand, religion remains a prominent fact of daily life in the modern Middle East, and the friction within Islam between Sunnis and Shias is at the heart of many of the region’s conflicts. This friction dates back to the a vested interest in maintaining the free flow of oil and gas from the region. Oil is a fungible commodity, and the U.S. economy remains vulnerable to sudden spikes in world oil prices. During the COVID-19 crisis, oil prices plunged to below zero in April 2020 after stay-at-home orders caused a severe imbalance between supply and demand. This unprecedented drop in demand sparked an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, both of which tried to maintain revenue by increasing the price of the reduced amount of oil sold. Although both countries eventually agreed to reduce production by 12 percent, the plummet in oil prices during 2020 caused significant shocks for both exporters and importers.6 U.S. energy policies during 2021 exacerbated the problem. The new Administration’s decisions to shutter some existing energy production and refuse permission for new exploration made the U.S. more sensitive to energy market volatility originating from the Middle East. Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made matters worse. The price of oil jumped to more than $139 a barrel while gas prices doubled—the highest levels for both in almost 14 years.7 In November 2021 and February 2022, Saudi Arabia declined the U.S. request to increase oil production, choosing instead to abide by the April 2020 agreement between OPEC and Russia to cut production.8 Because many U.S. allies depend on Middle East oil and gas, there is also a second-order effect for the U.S. if supply from the Middle East is reduced or compromised. For example, Japan is the world’s third-largest economy and largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG).9 The U.S. might not have to depend on Middle East oil or LNG, but the economic consequences arising from a major disruption of supplies would ripple across the globe. Thus, tensions and instabilities continue to affect global energy markets and directly affect U.S. national security and economic interests. Financial and logistics hubs are growing along some of the world’s busiest transcontinental trade routes, and one of the region’s economic bright spots in terms of trade and commerce is in the Persian Gulf. The emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), along with Qatar, are competing to become the region’s top financial center. The region’s economic situation is part of what drives its political environment. The lack of 138 economic freedom helped to fuel the popular discontent that led ultimately to the Arab Spring uprisings, which began in early 2011 and disrupted economic activity, depressed foreign and domestic investment, and slowed economic growth. Sustained financial and economic growth could lead to greater opportunities for the region’s people, but tensions will persist as countries compete for this added wealth. The COVID-19 pandemic has had massive repercussions for the entire region, affecting economies and shaking political systems in the aftermath of the crisis. Regional gross domestic product (GDP) did rise by 3 percent last year after contracting 5 percent in 2020, but most Middle Eastern economies will not exceed their pre-pandemic GDP per capita in 2022 according to economic projections.10 Countries that were already facing economic challenges before the pandemic are now facing a long road to recovery, increasing the likelihood of political instability in an already fragile region. The political environment has a direct bearing on how easily the U.S. military can operate in the region. The political situation in many Middle Eastern countries remains fraught with uncertainty. The Arab Spring uprisings of 2010–2012 formed a sandstorm that eroded the foundations of many authoritarian regimes, erased borders, and destabilized many of the region’s countries,11 but the popular uprisings in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Bahrain, Syria, and Yemen did not usher in a new era of democracy and liberal rule as many in the West were hoping. At best, they made slow progress toward democratic reform; at worst, they added to political instability, exacerbated economic problems, and contributed to the rise of Islamist extremists. Today, the region’s economic and political outlooks remain bleak. In some cases, self-interested elites have prioritized regime survival over real investment in human capital, aggravating the material deprivation of youth as issues of endemic corruption, high unemployment, and the rising cost of living remain unresolved. Since 2019, large-scale protests have called attention to the region’s lack of economic and political progress. COVID-19 lockdowns and curfews temporarily disrupted protests in Lebanon and Iraq, but demonstrations resumed in 2020. They failed to gain momentum, but more recently, the spike in food and gas prices caused in part by the Russian invasion of Ukraine has sparked demonstrations in both countries that, alongside 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength surrogate militias. These Iran-backed militias have carried out terrorist campaigns against U.S. forces and allies in the region for many years. On January 2, 2020, President Donald Trump ordered an air strike that killed General Qassem Suleimani, leader of the Iranian Quds Force, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, leader of an Iraqi Shia paramilitary group, both of whom had been responsible for carrying out attacks against U.S. personnel in Iraq. Suleimani’s and Muhandis’s deaths were a huge loss for Iran’s regime and its Iraqi proxies. They also were a major operational and psychological victory for the United States.19 In Afghanistan, Tehran’s influence on some Shiite groups is such that thousands have volunteered to fight for Bashar al-Assad in Syria.20 Iran also provided arms to the Taliban after it was ousted from power by a U.S.-led coalition21 and has long considered the Afghan city of Herat near the Afghan–Iranian border to be within its sphere of influence. The Biden Administration’s disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan paved the way for a Taliban takeover and may deepen ties between Tehran and Kabul, increasing Iran’s growing alliances in the region. Iran already looms large over its weak and divided Arab rivals. Iraq and Syria have been destabilized by insurgencies and civil war and may never fully recover; Egypt is distracted by its own internal problems, economic imbalances, and the Islamist extremist insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula; and Jordan has been inundated by a flood of Syrian refugees and is threatened by the spillover of Islamist extremist groups from Syria.22 Meanwhile, Tehran has continued to build up its missile arsenal, now the largest in the Middle East; has intervened to prop up the Assad regime in Syria; and supports Shiite Islamist revolutionaries in Yemen and Bahrain.23 In Syria, the Assad regime’s brutal repression of peaceful demonstrations early in 2011 ignited a fierce civil war that killed more than half a million people and created a major humanitarian crisis: according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “13.4 million people in need of humanitarian and protection assistance in Syria”; “6.6 million Syrian refugees worldwide, of whom 5.6 million hosted in countries near Syria” like Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan; and “6.7 million internally displaced persons” within Syria.24 The large refugee populations created by this civil war could become a source of recruits for extremist groups. For example, both The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 139 ongoing socioeconomic deterioration, will fuel further discontent.12 If similar protests were to break out across the region, the operational environment for U.S. forces could well be affected. There is no shortage of security challenges for the U.S. and its allies in this region. Using the breathing space and funding afforded by the July 14, 2015, Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA),13 for example, Iran exploited Shia–Sunni tensions to increase its influence on embattled regimes and undermine adversaries in Sunni-led states. In May 2018, the Trump Administration left the JCPOA after European allies failed to address many of its serious flaws, including its sunset clauses, and imposed crippling economic sanctions in a “maximum pressure campaign.”14 The sanctions are meant to force changes in Iran’s behavior, particularly with regard to its support for terrorist organizations and refusal to renounce a nascent nuclear weapons program.15 Many of America’s European allies publicly denounced the Trump Administration’s decision to withdraw from the JCPOA, but most officials agree privately that the agreement is flawed and needs to be fixed. America’s allies in the Middle East, including Israel and most Gulf Arab states, supported the U.S. decision and welcomed a harder line against the Iranian regime.16 However, the Biden Administration’s efforts to resurrect the JCPOA threaten to disrupt the gains made by the Trump Administration. Iran has been mounting its own maximum-pressure campaign to force President Joseph Biden to lift sanctions and return to the 2015 agreement without imposing conditions. Indirect talks brokered by the European Union between U.S. and Iranian diplomats in Vienna resumed in April 2021, but as this study was being prepared, talks had stalled and a deal had not been reached.17 Despite Iran’s insistence, the Biden Administration has rightly refused to lift the terrorist designations of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).18 Tehran attempts to run an unconventional empire by exerting great influence on sub-state entities like Hamas in the Palestinian territories, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Mahdi movement and other Shia militias in Iraq, and the Houthi insurgents in Yemen. The Iranian Quds Force, the special-operations wing of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, has orchestrated the formation, arming, training, and operations of these sub-state entities as well as other the Islamist Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, formerly known as the al-Qaeda–affiliated Jabhat Fateh al-Sham and before that as the al-Nusra Front, and the self-styled IS, formerly known as ISIS or ISIL and before that as al-Qaeda in Iraq, used the power vacuum created by the war to carve out extensive sanctuaries where they built proto-states and trained militants from a wide variety of other Arab countries, Central Asia, Russia, Europe, Australia, and the United States.25 At the height of its power, with a sophisticated Internet and social media presence and by capitalizing on the civil war in Syria and sectarian divisions in Iraq, the IS was able to recruit more than 25,000 fighters from outside the region to join its ranks in Iraq and Syria. These foreign fighters included thousands from Western countries, among them the United States. In 2014, the U.S. announced the formation of a broad international coalition to defeat the Islamic State. By early 2019, the territorial “caliphate” had been destroyed by a U.S.-led coalition of international partners. However, the socioeconomic meltdown of Lebanon and ongoing fighting in Syria present an environment that the IS can exploit to reconstitute itself. Multiple reports indicate that the IS is recruiting young men in Tripoli, Lebanon.26 There is a real danger that IS or other Islamic extremists could capitalize on the security vacuum created by that country’s ongoing deterioration.27 Arab–Israeli tensions are another source of regional instability. The repeated breakdown of Israeli–Palestinian peace negotiations has created an even more antagonistic situation. Hamas, the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood that has controlled Gaza since 2007, seeks to transform the conflict from a national struggle over sovereignty and territory into a religious conflict in which compromise is denounced as blasphemy. Hamas invokes jihad in its struggle against Israel and seeks to destroy the Jewish state and replace it with an Islamic state. The signing of the Abraham Accords in 2020 caused a brief spark of hope. These U.S.-brokered agreements normalizing relations between Israel and the UAE and between Israel and Bahrain have created new opportunities for trade, investment, and defense cooperation.28 They are also important milestones in the diplomatic march toward a broader Arab–Israeli peace.29 However, Israeli–Palestinian tensions have only worsened over the past two years. In April 2022, 140 tensions escalated after nearly a month of deadly violence and attacks in Jerusalem’s old city. Hamas fired a barrage of rockets into Israel from Gaza, and Israel responded with air strikes.30 This escalation is remarkably similar to the 11-day war that took place around the same time in 2021.31 Increased violence threatens the unity of Israel’s ideologically divided coalition government led by Naftali Bennett. Members of the coalition, including the country’s Arab minority Ra’am party, have suspended their support as a result of violence at the Al-Aqsa Mosque, causing the coalition to lose its slim majority in parliament.32 As this study was being prepared, the situation remained tense. Important Alliances and Bilateral Relations in the Middle East The U.S. has strong military, security, intelligence, and diplomatic ties with several Middle Eastern nations, including Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Because the historical and political circumstances that led to the creation of NATO have been largely absent in the Middle East, the region lacks a similarly strong collective security organization. When it came into office, the Trump Administration proposed the idea of a multilateral Middle East Strategic Alliance with its Arab partners.33 The initial U.S. concept, which included security, economic cooperation, and conflict resolution and deconfliction, generated considerable enthusiasm, but the project has since been sidelined. Middle Eastern countries traditionally have preferred to maintain bilateral relationships with the U.S. and generally have shunned multilateral arrangements because of the lack of trust among Arab states. This lack of trust manifested itself in June 2017 when the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt, and several other Muslim-majority countries cut or downgraded diplomatic ties with Qatar after Doha was accused of supporting terrorism in the region.34 These nations severed all commercial land, air, and sea travel with Qatar and expelled Qatari diplomats and citizens. In January 2021, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt agreed to restore ties with Qatar during the 41st Gulf Cooperation Council Summit. Per the agreement, Saudi Arabia and its GCC allies lifted the economic 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength participate in the annual Hajj pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca. Riyadh has been a key partner in efforts to counter the influence of Iran. The U.S. is also the largest provider of arms to Saudi Arabia and regularly, if not controversially, sells munitions needed to resupply stockpiles expended in the Saudi-led campaign against the Houthis in Yemen. Under the Biden Administration, bilateral relations have shown signs of deterioration because the Administration has turned a blind eye to Houthi aggression. For example, the Biden Administration lifted the Trump Administration’s designation of the Houthi Ansar Allah (Supporters of God) movement as a terrorist organization despite Houthi drone and ballistic missile attacks against military and civilian targets in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have called for a redesignation of the Houthis, but as this book was being prepared, no such designation had been imposed.39 Gulf Cooperation Council. The GCC’s member countries are located in an oil-rich region close to the Arab–Persian fault line and are therefore strategically important to the U.S.40 The root of Arab–Iranian tensions in the Gulf is Tehran’s ideological drive to export its Islamist revolution and overthrow the traditional rulers of the Arab kingdoms. This ideological clash has further amplified long-standing sectarian tensions between Shia Islam and Sunni Islam. Tehran has sought to radicalize Shia Arab minority groups to undermine Sunni Arab regimes in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Yemen, and Bahrain. It also sought to incite revolts by the Shia majorities in Iraq against Saddam Hussein’s regime and in Bahrain against the Sunni al-Khalifa dynasty. Culturally, many Iranians look down on the Gulf States, many of which they see as artificial entities carved out of the former Persian Empire and propped up by Western powers. GCC member countries often have difficulty agreeing on a common policy with respect to matters of security. This reflects both the organization’s intergovernmental nature and its members’ desire to place national interests above those of the GCC. The 2017 dispute regarding Qatar illustrates this difficulty. Another source of disagreement involves the question of how best to deal with Iran. The UAE and Saudi Arabia, states that once opposed the Iran nuclear deal, were courting Tehran through diplomatic engagements in 2021.41 Bahrain still maintains The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 141 and diplomatic blockade of Qatar, reopening their airspace, land, and sea borders. This diplomatic détente paves the way for full reconciliation in the GCC and, at least potentially, a more united front in the Gulf.35 Military training is an important part of these relationships. Exercises involving the United States are intended principally to ensure close and effective coordination with key regional partners, demonstrate an enduring U.S. security commitment to regional allies, and train Arab armed forces so that they can assume a larger share of responsibility for regional security. Israel. America’s most important bilateral relationship in the Middle East is with Israel. Both countries are democracies, value free-market economies, and believe in human rights at a time when many Middle Eastern countries reject those values. With support from the United States, Israel has developed one of the world’s most sophisticated air and missile defense networks.36 No significant progress on peace negotiations with the Palestinians or on stabilizing Israel’s volatile neighborhood is possible without a strong and effective Israeli–American partnership. Ties between the U.S. and Israel improved significantly during the Trump Administration, encouraged by the relocation of America’s embassy from Tel Aviv to western Jerusalem in 2018 and the Administration’s role in facilitating the Abraham Accords, which were signed in 2020, and so far have shown no signs of deteriorating under the Biden Administration.37 However, beyond “floating the idea of a White House meeting between senior Israeli and Palestinian officials,”38 the Biden Administration has shown little interest in taking an active role in Israeli–Palestinian peace negotiations. If the conflict between the two sides continues to escalate, President Biden may find himself pressured to become more involved. Saudi Arabia. After Israel, the U.S. military relationship is deepest with the Gulf States, including Saudi Arabia, which serves as de facto leader of the Gulf Cooperation Council. America’s relationship with Saudi Arabia is based on pragmatism and is important for both security and economic reasons, but it has come under intense strain since the murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi by Saudi security services in Turkey in 2018. The Saudis enjoy huge influence across the Muslim world, and approximately 2 million Muslims a hawkish view of the threat from Iran. Oman prides itself on its regional neutrality, and Qatar shares natural gas fields with Iran, so it is perhaps not surprising that both countries view Iran’s activities in the region as less of a threat and maintain cordial relations with Tehran. Kuwait tends to fall somewhere in the middle. Intra-GCC relations also can be problematic. Egypt. Egypt is another important U.S. military ally. As one of six Arab countries that maintain diplomatic relations with Israel (the others are Jordan, Bahrain, the UAE, Sudan, and Morocco), Egypt is closely enmeshed in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and remains a leading political, diplomatic, and military power in the region. Relations between the U.S. and Egypt have been difficult since the 2011 downfall of President Hosni Mubarak after 30 years of rule. The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi was elected president in 2012 and used the Islamist-dominated parliament to pass a constitution that advanced an Islamist agenda. Morsi’s authoritarian rule, combined with rising popular dissatisfaction with falling living standards, rampant crime, and high unemployment, led to a massive wave of protests in June 2013 that prompted a military coup in July. The leader of the coup, Field Marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, pledged to restore democracy and was elected president in 2014 and again in 2018 in elections that many considered to be neither free nor fair. Sisi’s government faces major political, economic, and security challenges. However, because of Egypt’s ban on anti-government demonstrations and Sisi’s tight control of internal security, there was only one outbreak of protests in 2018.42 Internal security may deteriorate if bread prices continue to rise—a development that could trigger a new wave of anti-government protests—or if the Islamic State resurges inside Egypt. Historically, figures on Middle East defense spending have been very unreliable, and the lack of data has worsened. For 2020, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, there were no available data for Qatar, Syria, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.44 Different security factors drive the degree to which Middle Eastern countries fund, train, and arm their militaries. For Israel, which fought and defeated Arab coalitions in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982, the chief potential threat to its existence is now an Iranian regime that has called for Israel to be “wiped off the map.”45 States and non-state actors in the region have invested in asymmetric and unconventional capabilities to offset Israel’s military superiority.46 For the Gulf States, the main driver of defense policy is the Iranian military threat combined with internal security challenges; for Iraq, it is the internal threat posed by Iran-backed militias and Islamic State terrorists. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) are considered the most capable military forces in the Middle East. Iran and other Arab countries have spent billions of dollars in an effort to catch up with Israel, and the resulting “arms race,” supplied in part by the U.S., could threaten Israel’s qualitative military effectiveness (QME). Iran is steadily improving its missile capabilities and, due to the expiration of the U.N. conventional arms embargo in October 2020, now has access to the global arms trade.47 In response, Arab countries are upgrading their weapons capabilities while establishing officer training programs to improve military effectiveness.48 Israel funds its military sector heavily and has a strong national industrial capacity that is supported by significant funding from the U.S. Combined, these factors give Israel a regional advantage despite limitations of manpower and size. In particular, the IDF has focused on maintaining its superiority in missile defense, intelligence collection, precision Quality of Armed Forces in the Region weapons, and cyber technologies.49 The Israelis reThe quality and capabilities of the region’s armed gard their cyber capabilities as especially important forces are mixed. Some countries spend billions of and use cyber technologies for a number of purposes, dollars each year on advanced Western military including defending Israeli cyberspace, gathering hardware; others spend very little. Saudi Arabia’s intelligence, and carrying out attacks.50 military budget is by far the region’s largest, but in In 2010, Israel signed a $2.7 billion deal with 2020 (the most recent year for which data are avail- the U.S. to acquire approximately 20 F-35I “Adir” able), Oman spent the region’s highest percentage Lightning fighter jets (the F-35I is a heavily modof GDP on defense at 11 percent, followed by Saudi ified version of the Lockheed Martin F-35 stealth Arabia at 8.4 percent.43 fighter).51 In the 2021 conflict with Hamas, these 142 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength on arm sales by the Biden Administration, the sale moved forward in April 2021.57 The sale is somewhat controversial because of Israeli concerns about other regional powers also possessing the most modern combat aircraft, potentially challenging an important Israeli advantage. Middle Eastern countries have shown a willingness to use their military capability under certain and limited circumstances. The navies of GCC member countries rarely deploy beyond their Exclusive Economic Zones, but Kuwait, Bahrain, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have participated in and in some cases have commanded Combined Task Force 152, formed in 2004 to maintain maritime security in the Persian Gulf.58 The UAE and Qatar deployed fighters to participate in NATO-led operations over Libya in 2011, although they did not participate in strike operations. To varying degrees, all six GCC members also joined the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition with the UAE contributing the most in terms of air power.59 Air strikes in Syria by members of the GCC ended in 2017. With 438,500 active personnel and 479,000 reserve personnel, Egypt has the region’s largest Arab military force.60 It possesses a fully operational military with an army, air force, air defense, navy, and special operations forces. Until 1979, when the U.S. began to supply Egypt with military equipment, Cairo relied primarily on less capable Soviet military technology.61 Since then, its army and air force have been significantly upgraded with U.S. military weapons, equipment, and warplanes. Egypt’s naval capabilities have also grown with the opening of a naval base at Ras Gargoub and the commissioning of a fourth Type-209/1400 submarine and a second FREMM frigate.62 Egypt has struggled with increased terrorist activity in the Sinai Peninsula, including attacks on Egyptian soldiers, attacks on foreign tourists, and the October 2015 bombing of a Russian airliner departing from the Sinai. The Islamic State’s “Sinai Province” terrorist group has claimed responsibility for all of these actions.63 Although the Egyptian army regained control of two IS-controlled villages, militant attacks against army affiliates in different parts of North Sinai and the kidnapping of tribal leaders threaten the stability of the area.64 Jordan is a close U.S. ally and has small but effective military forces. The principal threats to its security include terrorism, turbulence spilling The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 143 jets were deployed in a major combat operation that targeted dozens of Hamas rocket launch tubes in northern Gaza.52 Israel maintains its qualitative superiority in medium-range and long-range missile capabilities and fields effective missile defense systems, including Iron Dome and Arrow, both of which the U.S. helped to finance. However, because Congress has yet to pass legislation to restock the interceptors for the Iron Dome, Israel is vulnerable to ongoing threats across its border.53 Israel also has a nuclear weapons capability (which it does not publicly acknowledge) that increases its strength relative to other powers in the region and has helped to deter adversaries as the gap in conventional capabilities has been reduced. After Israel, the most technologically advanced and best-equipped armed forces are found in the GCC countries. Previously, the export of oil and gas meant that there was no shortage of resources to devote to defense spending, but the collapse of crude oil prices has forced oil-exporting countries to adjust their defense spending patterns. Nevertheless, GCC nations still have the region’s best-funded (even if not necessarily its most effective) Arab armed forces. All GCC members boast advanced defense hardware that reflects a preference for U.S., U.K., and French equipment. Saudi Arabia maintains the GCC’s most capable military force. It has an army of 75,000 soldiers and a National Guard of 130,000 personnel reporting directly to the king. The army operates 1,010 main battle tanks including 500 U.S.-made M1A2s. Its air force is built around American-built and British-built aircraft and consists of more than 456 combat-capable aircraft that include F-15s, Tornados, and Typhoons.54 In fact, air power is the strong suit of most GCC members. Oman, for example, operates F-16s and Typhoons. In 2018, the U.S. government awarded Lockheed Martin a $1.12 billion contract to produce 16 new F-16 Block 70 aircraft (Lockheed Martin’s newest and most advanced F-16 production configuration) for the Royal Bahraini Air Force.55 Qatar operates French-made Mirage fighters and is buying 24 Typhoons from the U.K.56 In November 2020, the U.S. Department of State notified Congress that it had approved the sale of a $23.4 billion defense package of F-35A Joint Strike Fighters, armed drones, munitions, and associated equipment to the UAE. After a temporary freeze over from Syria and Iraq, and the resulting flow of refugees. Although Jordan faces few conventional threats from its neighbors, its internal security is threatened by Islamist extremists returning from fighting in the region who have been emboldened by the growing influence of al-Qaeda and other Islamist militants. As a result, Jordan’s highly professional armed forces have focused on border and internal security in recent years. Considering Jordan’s size, its conventional capability is significant. Jordan’s ground forces total 86,000 soldiers and include 182 British-made Challenger 1 tanks and four French-made Leclerc tanks. Forty-seven F-16 Fighting Falcons form the backbone if its air force,65 and its special operations forces are highly capable, having benefitted from extensive U.S. and U.K. training. Jordanian forces have served in Afghanistan and in numerous U.N.led peacekeeping operations. Iraq has fielded one of the region’s most dysfunctional military forces. After the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2011, Iraq’s government selected and promoted military leaders according to political criteria.66 Shiite army officers were favored over their Sunni, Christian, and Kurdish counterparts, and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki chose top officers according to their political loyalties. Politicization of the armed forces also exacerbated corruption within many units with some commanders siphoning off funds allocated for “ghost soldiers” who never existed or had been separated from the army for various reasons.67 The promotion of incompetent military leaders, poor logistical support because of corruption and other problems, limited operational mobility, and weaknesses in intelligence, reconnaissance, medical support, and air force capabilities have combined to undermine the effectiveness of Iraq’s armed forces. In June 2014, for example, the collapse of as many as four divisions that were routed by vastly smaller numbers of Islamic State fighters led to the fall of Mosul.68 The U.S. and its allies responded with a massive training program for the Iraqi military that led to the liberation of Mosul on July 9, 2017.69 Since 2017, the capabilities and morale of Iraq’s armed forces have improved, but there is still concern about Baghdad’s ability to sustain operational effectiveness in the face of the current U.S. drawdown and redeployment of forces. The continued presence of armed militias presents the biggest obstacle to force unity.70 144 Current U.S. Military Presence in the Middle East Before 1980, the limited U.S. military presence in the Middle East consisted chiefly of a small naval force that had been based in Bahrain since 1958. The U.S. “twin pillar” strategy relied on prerevolutionary Iran and Saudi Arabia to take the lead in defending the Persian Gulf from the Soviet Union and its client regimes in Iraq, Syria, and South Yemen,71 but the 1979 Iranian revolution demolished one pillar, and the December 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan increased the Soviet threat to the Gulf. In January 1980, President Jimmy Carter proclaimed in a commitment known as the Carter Doctrine that the United States would take military action to defend oil-rich Persian Gulf States from external aggression. In 1980, he ordered the creation of the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF), the precursor to U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM), which was established in January 1983.72 Until the late 1980s, according to USCENTCOM, America’s “regional strategy still largely focused on the potential threat of a massive Soviet invasion of Iran.”73 After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime became the chief threat to regional stability. Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, and the United States responded in January 1991 by leading an international coalition of more than 30 nations to expel Saddam’s forces from Kuwait. CENTCOM commanded the U.S. contribution of more than 532,000 military personnel to the coalition’s armed forces, which totaled at least 737,000.74 This marked the peak U.S. force deployment in the Middle East. Confrontations with Iraq continued throughout the 1990s as Iraq continued to violate the 1991 Gulf War cease-fire. Baghdad’s failure to cooperate with U.N. arms inspectors to verify the destruction of its weapons of mass destruction and its links to terrorism led to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. During the initial invasion, U.S. forces numbered nearly 192,000,75 joined by military personnel from coalition forces. Apart from the “surge” in 2007, when President George W. Bush deployed an additional 30,000 personnel, the number of American combat forces in Iraq fluctuated between 100,000 and 150,000.76 In December 2011, the U.S. officially completed its withdrawal of troops, leaving only 150 personnel attached to the U.S. embassy in Iraq.77 Later, in 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength MAP 3 U.S. Access to Bases and Facilities in the Middle East COUNTRY U.S. TROOPS TURKEY SYRIA Med. Sea ISRAEL 13,500 8,000–10,000 7,000 Kuwait Qatar Bahrain UAE Jordan Saudi Arabia Iraq Oman 2 3,500 3,145 2,700 2,500 A few hundred IRAQ 1 JORDAN KUWAIT 4 5 PAK. 7 8 6 EGYPT AFG. IRAN 3 BAHRAIN QATAR Persian 9 Gulf 11 10 12 U.A.E. SAUDI ARABIA Gulf of Aden 13 14 OMAN 16 Red Sea Arabian Sea 17 18 SUDAN 15 YEMEN ERITREA JORDAN 1 Muwaffaq Salti Airbase BAHRAIN 7 Khalifa bin Salman Port 8 Shaykh Isa Air Base IRAQ 13 14 15 QATAR 9 Al Udeid Air Base 2 al-Asad Air Base KUWAIT 3 Ali al-Salem Air Base 4 Ahmad al-Jabir Air Base 5 Camp Arifjan 16 17 18 OMAN Musnanah Air Base Muscat International Airport RAFO Masirah Al Duqm Port RAFO Thumrait Salalah Port UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 10 Al-Dhafra Air Base 11 Jebel Ali Port 12 Fujairah Naval Base SAUDI ARABIA 6 Eskan Village Air Base SOURCE: Heritage Foundation research. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military A heritage.org 145 the aftermath of IS territorial gains in Iraq, the U.S. redeployed thousands of troops to the country to assist Iraqi forces against IS and help to build Iraqi capabilities. In July 2021, the Biden Administration announced that America’s combat mission in Iraq would come to a close by the end of the year and that the remaining U.S. forces would transition to an advisory role. U.S. force levels in Iraq declined from 5,200 in 2020 to 2,500 in January 2021.78 The U.S. also continues to maintain a limited number of forces in other locations in the Middle East, primarily in GCC countries. Rising naval tensions in the Persian Gulf prompted the additional deployments of troops, Patriot missile batteries, and combat aircraft to the Gulf in late 2019 to deter Iran, but most were later withdrawn.79 By January 2022, CENTCOM deployed an estimated 40,000 to 60,000 U.S. troops in 21 countries within its area of responsibility.80 Although the exact disposition of U.S. forces is hard to triangulate because of the fluctuating nature of U.S. military operations in the region,81 information gleaned from open sources reveals the following: l Kuwait. More than 13,500 U.S. personnel are based in Kuwait and spread among Camp Arifjan, Ahmad al-Jabir Air Base, and Ali al-Salem Air Base. A large depot of prepositioned equipment and a squadron of fighters and Patriot missile systems are also deployed to Kuwait.82 l 5,000 aircraft overflights, 600 aircraft landings, and 80 port calls annually. The number of U.S. military personnel in Oman has fallen to a few hundred, mostly from the U.S. Air Force. According to the Congressional Research Service, “the United States reportedly has access to Oman’s military airfields in Muscat (the capital), Thumrait, Masirah Island, and Musnanah” as well as (pursuant to a March 2019 Strategic Framework Agreement) the ports of Al Duqm and Salalah.84 l l UAE. About 3,500 U.S. personnel are deployed at Jebel Ali port, Al Dhafra Air Base, and naval facilities at Fujairah. Jebel Ali port is the U.S. Navy’s busiest port of call for aircraft carriers. U.S. Air Force personnel who are stationed in the UAE use Al Dhafra Air Base to operate fighters, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), refueling aircraft, and surveillance aircraft. In addition, the United States has regularly deployed F-22 Raptor combat aircraft to Al Dhafra and in April 2021 deployed the F-35 combat aircraft because of escalating tensions with Iran. Patriot and Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile systems are deployed for air and missile defense.83 l l 146 Oman. In 1980, Oman became the first Gulf State to welcome a U.S. military base. Today, it provides important access in the form of over Bahrain. Approximately 7,000 U.S. military personnel are based in Bahrain. Because Bahrain is home to Naval Support Activity Bahrain and the U.S. Fifth Fleet, most U.S. military personnel there belong to the U.S. Navy. A significant number of U.S. Air Force personnel operate out of Shaykh Isa Air Base, where F-16s, F/A-18s, and P-8 surveillance aircraft are stationed. U.S. Patriot missile systems also are deployed to Bahrain. The deep-water port of Khalifa bin Salman is one of the few facilities in the Gulf that can accommodate U.S. aircraft carriers.85 Saudi Arabia. In June 2021, President Biden reported to Congress that approximately 2,700 U.S. military personnel were deployed in Saudi Arabia “to protect United States forces and interests in the region against hostile action by Iran or Iran-backed groups.” The President confirmed that these troops, “operating in coordination with the Government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, provide air and missile defense capabilities and support the operation of United States fighter aircraft.”86 The six-decade-old United States Military Training Mission to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the four-decade-old Office of the Program Manager of the Saudi Arabian National Guard Modernization Program, and the Office of the Program Manager–Facilities Security Force are based in Eskan Village Air Base approximately 13 miles south of the capital city of Riyadh.87 Qatar. The number of U.S. personnel, mainly from the U.S. Air Force, deployed in Qatar “has ranged from about 8,000 to over 10,000.”88 The U.S. operates its Combined Air Operations 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Center at Al Udeid Air Base, which is one of the world’s most important U.S. air bases. It is also the base from which the anti-ISIS campaign was headquartered. Heavy bombers, tankers, transports, and ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) aircraft operate from Al Udeid Air Base, which also serves as the forward headquarters of CENTCOM. The base houses prepositioned U.S. military equipment and is defended by U.S. Patriot missile systems. The recent tensions between Qatar and other Arab states have not affected the United States’ relationship with Qatar. l l l l l U.S. Army Forces Central Command. USARCENT is USCENTCOM’s land component. Based in Kuwait, it is responsible for land operations in an area that totals 4.6 million square miles (1.5 times larger than the continental United States). U.S. Air Forces Central Command. USAFCENT is USCENTCOM’s air component. Based in Qatar, it is responsible for air operations and for working with the air forces of partner countries in the region. It also manages an extensive supply and equipment prepositioning program at several regional sites. U.S. Marine Forces Central Command. MARCENT is USCENTCOM’s designated Marine Corps service component. Based in Bahrain, it is responsible for all Marine Corps forces in the region. U.S. Special Operations Command Central. SOCCENT is a subordinate unified command under USCENTCOM. Based in Qatar, it is responsible for planning special operations throughout the USCENTCOM region, planning and conducting peacetime joint/combined special operations training exercises, and orchestrating command and control of peacetime and wartime special operations. CENTCOM “directs and enables military operations and activities with allies and partners to increase regional security and stability in support of enduring U.S. interests.”91 Execution of this mission is supported by four service component commands (U.S. Naval Forces Middle East [USNAVCENT]; U.S. Army Forces Middle East [USARCENT]; U.S. Air Forces Middle East [USAFCENT]; and U.S. Marine Forces Middle East [MARCENT]) and one suborIn addition to the American military presence in dinate unified command (U.S. Special Operations the region, two NATO allies—the United Kingdom Command Middle East [SOCCENT]). and France—play an important role. The U.K.’s presence in the Middle East is a legaU.S. Naval Forces Central Command. UScy of British imperial rule. The U.K. has maintained NAVCENT is USCENTCOM’s maritime compo- close ties with many countries that it once ruled nent. With its forward headquarters in Bahrain, and has conducted military operations in the reit is responsible for commanding the afloat gion for decades. As of 2020, approximately 1,350 units that rotationally deploy or surge from the British service personnel were based throughout the United States in addition to other ships that are region. This number fluctuates with the arrival of based in the Gulf for longer periods. USNAVvisiting warships.92 CENT conducts persistent maritime operations The British presence in the region is dominated to advance U.S. interests, deter and counter by the Royal Navy. Permanently based naval assets disruptive countries, defeat violent extreminclude four mine hunters and one Royal Fleet ism, and strengthen partner nations’ maritime Auxiliary supply ship. In addition, there generally l The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 147 Jordan. According to CENTCOM, Jordan “is one of [America’s] strongest and most reliable partners in the Levant sub-region.”89 Although there are no U.S. military bases in Jordan, the U.S. has a long history of conducting training exercises out of Jordanian air bases. Due to recent events in neighboring Syria, in addition to other military assets like fighter jets and air defense systems, “approximately 3,147 U.S. military personnel are deployed to Jordan to ‘counter-ISIS operations, enhance Jordan’s security, and promote regional stability.’”90 capabilities in order to promote a secure maritime environment in an area that encompasses approximately 2.5 million square miles of water. are frigates or destroyers in the Gulf or Arabian Sea performing maritime security duties,93 and (although such matters are not the subject of public discussion) U.K. attack submarines also operate in the area. In April 2018, as a sign of its long-term maritime presence in the region, the U.K. opened a base in Bahrain—its first overseas military base in the Middle East in more than four decades.94 The U.K. has made a multimillion-dollar investment in modernization of the Duqm Port complex in Oman to accommodate its new Queen Elizabeth–class aircraft carriers.95 The U.K. also has a sizeable Royal Air Force (RAF) presence in the region, mainly in the UAE and Oman. A short drive from Dubai, Al-Minhad Air Base is home to a small contingent of U.K. personnel, and small RAF detachments in Oman support U.K. and coalition operations in the region. Although considered to be in Europe, the U.K.’s Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia in Cyprus have supported U.S. military and intelligence operations in the past and are expected to continue to do so. The British presence in the region extends beyond soldiers, ships, and planes. A British-run staff college operates in Qatar, and Kuwait chose the U.K. to help run its own equivalent of the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.96 The U.K. also plays a very active role in training the Saudi Arabian and Jordanian militaries. The French presence in the Gulf is smaller than the U.K.’s but still significant. France opened its first military base in the Gulf in 2009. Located in the emirate of Abu Dhabi, it was the first foreign military installation built by the French in 50 years.97 The French have 650 personnel based in the UAE, along with seven Rafale jets and an armored battlegroup, as well as military operations in Kuwait and Qatar.98 French ships have access to the Zayed Port in Abu Dhabi, which is big enough to handle every ship in the French Navy except the aircraft carrier Charles De Gaulle. Military support from the U.K. and France has been particularly important in Operation Inherent Resolve, a U.S.-led joint task force that was formed to combat the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. As of May 2021, France had between 600 and 650 troops stationed in the UAE, 600 stationed in Syria and Iraq, and 700 stationed in Lebanon.99 The U.K. temporarily redeployed troops back to the U.K. because of COVID-19 but announced in February 2021 that the 148 500 troops would be sent back along with an additional 3,500 troops to boost its counterterrorism training mission in Iraq.100 The additional troops will help both to prevent the IS from returning and to manage threats from Iran-backed militias more effectively. Another important actor in Middle East security is the small East African country of Djibouti. Djibouti sits on the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, through which an estimated 6.2 million barrels of oil a day transited in 2018 (the most recent year for which U.S. Energy Administration data are available) and which is a choke point on the route to the Suez Canal.101 An increasing number of countries recognize Djibouti’s value as a base from which to project maritime power and launch counterterrorism operations. The country is home to Camp Lemonnier, which can hold as many as 4,000 personnel and is the only permanent U.S. military base in Africa.102 China is also involved in Djibouti and has established its first permanent overseas base there. This base can house 10,000 troops, and Chinese marines have used it to stage live-fire exercises featuring armored combat vehicles and artillery. France, Italy, and Japan also have presences of varying strength in Djibouti.103 Key Infrastructure and Warfighting Capabilities The Middle East is critically situated geographically. Two-thirds of the world’s population lives within an eight-hour flight from the Gulf region, making it accessible from most other regions of the globe. The Middle East also contains some of the world’s most critical maritime choke points, including the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz. Although infrastructure is not as developed in the Middle East as it is in North America or Europe, during a decades-long presence, the U.S. has developed systems that enable it to move large numbers of matériel and personnel into and out of the region. According to the Department of Defense, at the height of U.S. combat operations in Iraq during the Second Gulf War, the U.S. presence included 165,000 servicemembers and 505 bases. Moving personnel and equipment out of the country was “the largest logistical drawdown since World War II” and included redeployment of “the 60,000 troops who remained in Iraq at the time and more than 1 million pieces of equipment ahead of their deadline.”104 The condition of the region’s roads varies from country to country. The most recent available data 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength reflect that 100 percent of the roads in Israel, Jordan, that these shipping lanes offer to America and her and the UAE are paved. Other nations—for example, allies. The major shipping routes include: Oman (49.3 percent); Saudi Arabia (21.5 percent); and Yemen (8.7 percent)—have poor paved road The Suez Canal. In 2021, more than 20,000 coverage.105 Rail coverage is also poor. China’s Belt ships transited the Suez Canal—an average of and Road Initiative has targeted ports, roads, and 55 ships per day.110 Considering that the canal railway development in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and many itself is 120 miles long but only 670 feet wide, other countries, and the result could be improved this is an impressive amount of traffic. The Suez transportation conditions across the region at the Canal is important to Europe because it proexpense of U.S. interests.106 vides access to oil from the Middle East. It also The U.S. has access to several airfields in the reserves as an important strategic asset, as it is gion. The primary air hub for U.S. forces is Al Udeid used routinely by the U.S. Navy to move surface Air Base in Qatar. Other airfields include Ali Al Salem combatants between the Mediterranean Sea Air Base, Kuwait; Al Dhafra, UAE; Al Minhad, UAE; and the Red Sea. Thanks to a bilateral arrangeIsa, Bahrain; Eskan Village Air Base, Saudi Arabia; ment between Egypt and the United States, the Muscat, Oman; Thumrait, Oman; and Masirah IsU.S. Navy enjoys priority access to the canal.111 land, Oman, in addition to the commercial airport at Seeb, Oman. In the past, the U.S. has used major The journey through the narrow waterway is airfields in Iraq, including Baghdad International no easy task for large surface combatants. The Airport and Balad Air Base, as well as Prince Sultan canal was not constructed with the aim of acAir Base in Saudi Arabia. commodating 100,000-ton aircraft carriers and The fact that a particular air base is available to therefore exposes a larger ship to attack. For this the U.S. today, however, does not necessarily mean reason, different types of security protocols are that it will be available for a particular operation in followed, including the provision of air support the future. For example, because of their more corby the Egyptian military.112 These security prodial relations with Iran, Qatar and Oman probably tocols, however, are not foolproof. In April 2021, would not allow the U.S. to use air bases in their terthe Suez Canal was closed for more than 11 days ritory for strikes against Iran unless they were first after a container ship blocked the waterway, creattacked themselves. ating a 360-ship traffic jam that disrupted almost The U.S. also has access to ports in the region, 13 percent of global maritime traffic. This crisis perhaps the most important being the deep-water proves that ever-larger container ships transitport of Khalifa bin Salman in Bahrain and naval ing strategic choke points are prone to accidents facilities at Fujairah in the UAE.107 The UAE’s comthat can lead to massive disruptions of both globmercial port of Jebel Ali is open for visits from U.S. al maritime trade and U.S. maritime security.113 warships and the prepositioning of equipment for operations in theater.108 In March 2019, “Oman and Strait of Hormuz. According to the U.S. Enthe United States signed a ‘Strategic Framework ergy Information Administration, the Strait Agreement’ that expands the U.S.–Oman facilities of Hormuz, which links the Persian Gulf with access agreements by allowing U.S. forces to use the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman, “is the the ports of Al Duqm and Salalah.”109 The location world’s most important oil chokepoint because of these ports outside the Strait of Hormuz makes of the large volumes of oil that flow through them particularly useful. Approximately 90 percent the strait.”114 In 2020, its daily oil flow averaged of the world’s trade travels by sea, and some of the “around 18 million barrels” per day, or the equivbusiest and most important shipping lanes are loalent of about “[o]ne fifth of global oil supply.”115 cated in the Middle East. Tens of thousands of cargo Given the extreme narrowness of the passage ships travel through the Strait of Hormuz and the and its proximity to Iran, shipping routes Bab el-Mandeb Strait each year. through the Strait of Hormuz are particularGiven the high volume of maritime traffic in the ly vulnerable to disruption. Iran attacked oil region, no U.S. military operation can be undertaken tankers repeatedly in April and May 2021 and without consideration of the opportunity and risk continues to harass U.S. naval ships.116 l The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 149 l l Bab el-Mandeb Strait. The Bab el-Mandeb Strait is a strategic waterway located between the Horn of Africa and Yemen that links the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean. Exports from the Persian Gulf and Asia destined for Western markets must pass through the strait en route to the Suez Canal. Because the Bab el-Mandeb Strait is 18 miles wide at its narrowest point, passage is limited to two channels for inbound and outbound shipments.117 Maritime Prepositioning of Equipment and Supplies. The U.S. military has deployed noncombatant maritime prepositioning ships (MPS) containing large amounts of military equipment and supplies in strategic locations from which they can reach areas of conflict relatively quickly as associated U.S. Army or Marine Corps units located elsewhere arrive in the area. The British Indian Ocean Territory of Diego Garcia, an island atoll, hosts the U.S. Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia, which supports prepositioning ships that can supply Army or Marine Corps units deployed for contingency operations in the Middle East. Conclusion For the foreseeable future, the Middle East region will remain a key focus for U.S. military planners. Once considered relatively stable, mainly because of the ironfisted rule of authoritarian regimes, the area is now highly unstable and a breeding ground for terrorism. Overall, regional security has deteriorated in recent years. Even though the Islamic State (or at least its physical presence) appears to have been defeated, the nature of its successor is unclear. Iraq has restored its territorial integrity since the defeat of ISIS, but the political situation and future relations between Baghdad and the U.S. will remain difficult as long as Iran retains control of powerful Shia militias that it uses to intimidate Iraqi political leaders.118 Although the regional dispute with Qatar has been resolved, U.S. relations in the region will remain complex and difficult to manage. U.S. military operations, however, continue uninterrupted. Many of the borders created after World War I are under significant stress. In countries like Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, the supremacy of the nation-state is being challenged by non-state actors that wield influence, power, and resources comparable to those of small states. The region’s principal security and political challenges are linked to the unrealized aspirations of the Arab Spring, surging transnational terrorism, and meddling by Iran, which seeks to extend its influence in the Islamic world. These challenges are made more difficult by the Arab–Israeli conflict, Sunni–Shia sectarian divides, the rise of Iran’s Islamist revolutionary nationalism, and the proliferation of Sunni Islamist revolutionary groups. Thanks to its decades of military operations in the Middle East, the U.S. has developed tried-andtested procedures for operating in the region. Bases and infrastructure are well established, and the logistical processes for maintaining a large force forward deployed thousands of miles away from the homeland are well in place. Moreover, unlike in Europe, all of these processes have been tested recently in combat. The personal links between allied armed forces are also present. Joint training exercises improve interoperability, and U.S. military educational courses that are regularly attended by officers (and often royals) from the Middle East give the U.S. an opportunity to influence some of the region’s future leaders. America’s relationships in the region are based pragmatically on shared security and economic concerns. As long as these issues remain relevant to both sides, the U.S. is likely to have an open door to operate in the Middle East when its national interests require that it do so. Scoring the Middle East Operating Environment As noted at the beginning of this section, various aspects of the region facilitate or inhibit the ability of the U.S. to conduct military operations to defend its vital national interests against threats. Our assessment of the operating environment 150 uses a five-point scale that ranges from “very poor” to “excellent” conditions and covers four regional characteristics of greatest relevance to the conduct of military operations: 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 1. Very Poor. Significant hurdles exist for military operations. Physical infrastructure is insufficient or nonexistent, and the region is politically unstable. In addition, the U.S. military is poorly placed or absent, and alliances are nonexistent or diffuse. 2. Unfavorable. A challenging operating environment for military operations is marked by inadequate infrastructure, weak alliances, and recurring political instability. The U.S. military is inadequately placed in the region. 3. Moderate. A neutral to moderately favorable operating environment is characterized by adequate infrastructure, a moderate alliance structure, and acceptable levels of regional political stability. The U.S. military is adequately placed. 4. Favorable. A favorable operating environment includes good infrastructure, strong alliances, and a stable political environment. The U.S. military is well placed for future operations. The key regional characteristics consist of: a. Alliances. Alliances are important for interoperability and collective defense, as allies are more likely to lend support to U.S. military operations. Indicators that provide insight into the strength or health of an alliance include whether the U.S. trains regularly with countries in the region, has good interoperability with the forces of an ally, and shares intelligence with nations in the region. b. Political Stability. Political stability brings predictability for military planners when considering such things as transit, basing, and overflight rights for U.S. military operations. The overall degree of political stability indicates whether U.S. military actions would be hindered or enabled and reflects, for example, c. U.S. Military Positioning. Having military forces based or equipment and supplies staged in a region greatly facilitates the ability of the United States to respond to crises and, presumably, achieve success in critical “first battles” more quickly. Being routinely present in a region also helps the U.S. to remain familiar with its characteristics and the various actors that might either support or try to thwart U.S. actions. With this in mind, we assessed whether or not the U.S. military was well positioned in the region. Again, indicators included bases, troop presence, prepositioned equipment, and recent examples of military operations (including training and humanitarian) launched from the region. d. Infrastructure. Modern, reliable, and suitable infrastructure is essential to military operations. Airfields, ports, rail lines, canals, and paved roads enable the U.S. to stage, launch, and logistically sustain combat operations. We combined expert knowledge of regions with publicly available information on critical infrastructure to arrive at our overall assessment of this metric.119 The U.S. has developed an extensive network of bases in the Middle East region and has acquired substantial operational experience in combatting regional threats. At the same time, however, many of America’s allies are hobbled by political instability, economic problems, internal security threats, and mushrooming transnational threats. Although the region’s overall score remains “moderate,” as it was last year, it is in danger of falling to “poor” because of political instability and growing bilateral tensions with allies over the security implications of the proposed nuclear agreement with Iran and how best to fight the Islamic State. With this in mind, we arrived at these average scores for the Middle East (rounded to the nearest whole number): l Alliances: 3—Moderate l Political Stability: 2—Unfavorable The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 151 5. Excellent. An extremely favorable operating environment includes well-established and well-maintained infrastructure, strong and capable allies, and a stable political environment. The U.S. military is exceptionally well placed to defend U.S. interests. whether transfers of power are generally peaceful and whether there have been any recent instances of political instability in the region. l U.S. Military Positioning: 3—Moderate l Infrastructure: 3—Moderate Leading to a regional score of: Moderate Operating Environment: Middle East VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE Alliances Political Stability MODERATE % % % Infrastructure % OVERALL % U.S. Military Posture 152 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength FAVORABLE EXCELLENT Endnotes 1. For example, during a 1916 meeting in Downing Street, Sir Mark Sykes, Britain’s lead negotiator with the French on carving up the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, pointed to the map and told the Prime Minister that for Britain’s sphere of influence in the Middle East, “I should like to draw a line from the e in Acre [modern-day Israel] to the last k in Kirkuk [modern-day Iraq].” See James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle That Shaped the Middle East (London: Simon & Schuster U.K., 2011), pp. 7–20. See also Margaret McMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (New York: Random House, 2003). 2. S.B., “What Is the Difference Between Sunni and Shia Muslims?” The Economist, updated September 23, 2016, http://www.economist.com/blogs/ economist-explains/2013/05/economist-explains-19/ (accessed May 4, 2022). 3. Sabahat Khan, “MENA’s Youth Bulge Is a Regional Security Challenge,” The Arab Weekly, April 2, 2018, https://thearabweekly.com/menas-youthbulge-regional-security-challenge (accessed May 4, 2022). 4. Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, “Data/Graphs: OPEC Share of World Crude Oil Reserves, 2018,” https://www.opec.org/ opec_web/en/data_graphs/330.htm (accessed May 4, 2022). 5. Table, “The 10 Largest Oil Producers and Share of Total World Oil Production in 2020,” and table, “The 10 Largest Oil Consumers and Share of Total World Oil Consumption in 2018,” in U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): What Countries Are the Top Producers and Consumers of Oil?” last updated December 8, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq. php?id=709&t=6 (accessed May 4, 2022). 6. Grant Smith, “OPEC Output Hit 30-Year High During the Saudi–Russia Price War,” Bloomberg, May 1, 2020, https://www.worldoil.com/ news/2020/5/1/opec-output-hit-30-year-high-during-the-saudi-russia-price-war (accessed May 4, 2022). 7. BBC News, “Ukraine Conflict: Petrol at Fresh Record as Oil and Gas Prices Soar,” March 7, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-60642786 (accessed May 4, 2022). 8. James Phillips, “Biden’s Burnt Bridges Exacerbate Ukraine-Related Oil Crisis,” The Daily Signal, March 11, 2022, https://www.dailysignal. com/2022/03/11/bidens-burnt-bridges-exacerbate-ukraine-related-oil-crisis. 9. Oliver Reynolds, “The World’s Top 5 Largest Economies in 2024,” FocusEconomics, February 16, 2021, https://www.focus-economics.com/blog/ the-largest-economies-in-the-world (accessed May 4, 2022), and U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “Country Analysis Executive Summary: Japan,” last updated October 2020, https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Japan/ japan.pdf (accessed May 4, 2022). 11. See, for example, The Heritage Foundation, “The ‘Arab Spring’: Heritage Foundation Recommendations,” Heritage Foundation WebMemo No. 3222, April 13, 2011, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/report/the-arab-spring-heritage-foundation-recommendations. 12. Vivian Yee, “Mideast Feels the Pinch of Rising Food Prices as Ramadan Nears,” The New York Times, March 26, 2022, https://www.nytimes. com/2022/03/26/world/middleeast/mideast-food-prices-ramadan.html (accessed May 4, 2022). 13. See U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Joint Plan of Action (JPOA) Archive and Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) Archive,” https:// home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/iran-sanctions/joint-plan-of-action-jpoaarchive-and-joint-comprehensive-plan-of-action-jcpoa-archive (accessed May 4, 2022). 14. James Phillips and Peter Brookes, “Iran’s Nuclear Humpty Dumpty: The JCPOA Should Not Be Put Back Together Again,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No.3661, October 13, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/report/irans-nuclear-humpty-dumpty-the-jcpoa-should-not-beput-back-together-again. 15. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Sanctions Programs and Country Information: Iran Sanctions,” https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/ financial-sanctions/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/iran-sanctions (accessed May 4, 2022), and Peter Brookes, Brett D. Schaefer, and James Phillips, “Iran Nuclear Deal: Next Steps,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 5030, January 29, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/ middle-east/report/iran-nuclear-deal-next-steps. 16. Robert Berger, “Israel Welcomes Trump’s ‘Bold’ Decision to Leave Iran Deal,” Voice of America, May 9, 2018, https://www.voanews.com/a/israelwelcomes-donald-trump-decision-leave-iran-nuclear-deal/4386422.html (accessed May 4, 2022), and “Saudi Arabia Welcomes US Withdrawal from Iran Nuclear Deal,” Arab News, updated May 9, 2018, http://www.arabnews.com/node/1299156/saudi-arabia (accessed May 4, 2022). 17. James Phillips, “Biden Must Stand Up to Iran’s Proxy Extortion Strategy,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, March 8, 2021, https://www.heritage. org/middle-east/commentary/biden-must-stand-irans-proxy-extortion-strategy, and James Phillips, “U.S. Enters Multilateral Minefield in Indirect Nuclear Talks with Iran,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, April 6, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/commentary/us-entersmultilateral-minefield-indirect-nuclear-talks-iran. 18. Al-Monitor Staff, “Iran Nuclear Negotiations at Stalemate over IRGC Terror Listing,” Al-Monitor, April 20, 2022, https://www.al-monitor.com/ originals/2022/04/iran-nuclear-negotiations-stalemate-over-irgc-terror-listing (accessed May 4, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 153 10. Yousef Saba, “MENA Growth to Be ‘Uneven and Insufficient’ in 2022, World Bank Says,” Reuters, April 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/ middle-east/mena-growth-be-uneven-insufficient-2022-world-bank-says-2022-04-14/ (accessed May 4, 2022). 19. James Phillips, “How U.S. Strike Against Iranian General Changes the Rules of the Game in Iraq, Region,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, January 5, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/commentary/how-us-strike-against-iranian-general-changes-the-rules-the-game-iraqregion. 20. Sune Engel Rasmussen and Zahra Nader, “Iran Covertly Recruits Afghan Shias to Fight in Syria,” The Guardian, June 30, 2016, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/30/iran-covertly-recruits-afghan-soldiers-to-fight-in-syria (accessed May 4, 2022). 21. BBC News, “Hague Fury as ‘Iranian Arms’ Bound for Taliban Seized,” March 9, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12694266 (accessed May 4, 2022). 22. Chris Massaro, “US Has the Military Might, but Iran Will Lean on Proxies and Militias If They Get Dragged into the Conflict,” Fox News, May 20, 2019, https://www.foxnews.com/world/us-military-might-iran-proxies-militias-conflict (accessed May 4, 2022); Bruce Clingan, “Commentary: The U.S. Is Right to Restore Aid to Egypt,” Reuters, July 30, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-clingan-egypt-commentary/commentarythe-u-s-is-right-to-restore-aid-to-egypt-idUSKBN1KK1YE (accessed May 4, 2022); and Fact Sheet, “Jordan,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, October 2019, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/72076 (accessed May 4, 2022). 23. Peter Brookes and James Phillips, “The Growing Danger of Iran’s Missile Programs,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3605, April 13, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/report/the-growing-danger-irans-missile-programs. 24. “Past Month ‘Deadliest on Record’ for Syrian Civilians Killed in US-Led Air Strikes,” The Independent, May 23, 2017, http://www.independent. co.uk/news/world/middle-east/syria-war-us-air-strikes-civilian-death-toll-deadliest-on-record-isis-donald-trump-a7751911.html (accessed May 4, 2022), and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Syria Emergency,” updated March 15, 2021, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/syriaemergency.html (accessed May 4, 2022). 25. Les Picker, “Where Are ISIS’s Foreign Fighters Coming From?” in National Bureau of Economic Research Digest, June 2016, p. 6, https://www.nber. org/digest/jun16/jun16.pdf (accessed May 4, 2022). 26. “As Economy Collapses, Some Young Lebanese Turn to Extremism,” The Arab Weekly, April 2, 2022, https://thearabweekly.com/economycollapses-some-young-lebanese-turn-extremism (accessed May 4, 2022). 27. Nicole Robinson and Natasha Chernyavsky, “Lebanon’s Stalled Government Should Worry the US,” The Daily Signal, January 18, 2022, https:// www.dailysignal.com/2022/01/18/lebanons-stalled-government-should-worry-the-us. 28. Nicole Robinson and Rafi Levitt, “Abraham Accords: Sowing Seeds of Peace, Harvesting Fruits of Prosperity,” The Daily Signal, February 24, 2022, https://www.dailysignal.com/2022/02/24/abraham-accords-sowing-seeds-of-peace-harvesting-fruits-of-prosperity/, and Nicole Robinson and Eric Feely, “Abraham Accords Pave Way for Previously Unthinkable Arab–Israeli Defense Cooperation,” The Daily Signal, January 10, 2022, https://www.dailysignal.com/2022/01/10/abraham-accords-pave-way-for-previously-unthinkable-arab-israeli-defense-cooperation. 29. James Phillips, “How the Israel–Bahrain Peace Deal Will Reshape the Middle East,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, September 17, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/commentary/how-the-israel-bahrain-peace-deal-will-reshape-the-middle-east. 30. Joseph Krauss, “Explainer: Why Mideast Tensions Are Soaring Yet Again,” Associated Press, April 21, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/businessmiddle-east-jerusalem-israel-west-bank-6bf140ecb95b583382b582c56ddf2b01 (accessed May 5, 2022). 31. James Phillips, “Hamas Exploits Palestinian Unrest to Launch Rocket War Against Israel,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, May 12, 2021, https:// www.heritage.org/middle-east/commentary/hamas-exploits-palestinian-unrest-launch-rocket-war-against-israel, and BBC News, “Israel–Gaza Ceasefire Holds Despite Jerusalem Clash,” May 21, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-57195537 (accessed May 5, 2022). 32. Times of Israel Staff, “Ra’am Freezes Its Coalition and Knesset Membership amid Temple Mount Tensions,” The Times of Israel, April 17, 2022, https://www.timesofisrael.com/raam-mulls-coalition-membership-freeze-amid-temple-mount-tensions/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 33. Luke Coffey and James Phillips, “The Middle East Strategic Alliance: An Uphill Struggle,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 5056, April 7, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/report/the-middle-east-strategic-alliance-uphill-struggle. 34. Tamara Qiblawi, Mohammed Tawfeeq, Elizabeth Roberts, and Hamdi Alkhshali, “Qatar Rift: Saudi, UAE, Bahrain, Egypt Cut Diplomatic Ties,” CNN, updated July 27, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/06/05/middleeast/saudi-bahrain-egypt-uae-qatar-terror/index.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 35. Nicole Robinson, “Qatar’s Normalization with Gulf States Could Pave the Way Toward a Secure and Stable Persian Gulf,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, January 8, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/commentary/qatars-normalization-gulf-states-could-pave-the-waytoward-secure-and-stable. 36. Pieter D. Wezeman, “Conventional Strategic Military Capabilities in the Middle East,” EU Non-Proliferation Consortium Background Paper, July 2011, p. 8, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2016-03/Conventional-strategic-military-capabilities-in-the-Middle-East.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). Prepared for “EU Seminar to promote confidence building and in support of a process aimed at establishing a zone free of WMD and means of delivery in the Middle East,” Brussels, July 6–7, 2011. 37. Isabel Kershner, “9 Things to Know About Jerusalem as U.S. Embassy Opens,” The New York Times, May 13, 2018, https://www.nytimes. com/2018/05/13/world/middleeast/israel-jerusalem-us-embassy.html (accessed May 5, 2022), and Peace to Prosperity: A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinian and Israeli People, The White House, January 2020, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ Peace-to-Prosperity-0120.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 38. Barak Ravid, “Scoop: U.S. Floated White House Meeting of Israelis and Palestinians,” Axios, April 7, 2022, https://www.axios.com/white-housemeeting-israelis-palestinians-c12d7e66-2680-411d-b5c1-289890113189.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 154 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 39. James Phillips and Nicole Robinson, “Time to Hold the Houthis Accountable in Yemen,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 5261, April 7, 2022, https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/report/time-hold-the-houthis-accountable-yemen. 40. The GCC was founded in 1981 to offset the threat from Iran, which became hostile to Sunni-led Arab states after its 1979 revolution. 41. Karen DeYoung and Liz Sly, “Gulf Arab States that Opposed the Iran Nuclear Deal Are Now Courting Tehran,” The Washington Post, December 11, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/uae-saudi-iran-diplomacy-nuclear-deal/2021/12/11/8c51edae-586c-11ec-8396-5552bef55c3c_story. html (accessed May 5, 2022). 42. Declan Walsh, “Rare Protests Against Egypt’s Leader Erupt in Cairo and Elsewhere,” The New York Times, September 20, 2019, https://www. nytimes.com/2019/09/20/world/middleeast/anti-government-protests-egypt.html (accessed May 5, 2022), and Vivian Yee and Nada Rashwan, “Egypt’s Harsh Crackdown Quashes Protest Movement,” The New York Times, October 4, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/04/world/ middleeast/egypt-protest-sisi-arrests.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 43. Diego Lopes da Silva, Nan Tian, and Alexandra Marksteiner, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2020,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Fact Sheet, April 2021, p. 12, https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/fs_2104_milex_0.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 44. Ibid., p. 9, note 1, which specifies that the “[c]ountries included in the estimate are Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.” 45. Nazila Fathi, “Wipe Israel ‘Off the Map’ Iranian Says,” The New York Times, October 27, 2005, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/26/world/ africa/26iht-iran.html?_r=0 (accessed May 5, 2022). 46. Ibid. 47. The embargo “limited all U.N. member states from selling weaponry—including battle tanks, armored combat vehicles, large caliber artillery systems, combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, missiles or missile systems and spare parts—to the Islamic Republic.” United States Institute of Peace, “Part 1: History of Arms Embargo on Iran,” The Iran Primer, updated October 21, 2020, https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2020/ may/11/part-1-us-arms-embargo (accessed May 5, 2022), and Nasser Karimi, “UN Arms Embargo on Iran Expires,” Defense News, October 19, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/global/mideast-africa/2020/10/19/un-arms-embargoes-on-iran-expires/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 48. Jewish Institute for National Security of America, Gemunder Center U.S.–Israel Security Policy Project, “Arming Israel to Defeat Iranian Aggression: Frontloading Weapons Delivery,” November 2019, https://jinsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Arming-Israel-to-Defeat-IranianAggression-1.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 49. T. S. Allen, “Here Is How Israel’s Military Dominates the Battlefield,” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, February 27, 2018, http://nationalinterest. org/blog/the-buzz/here-how-israels-military-dominates-the-battlefield-24679 (accessed May 5, 2022). 51. Lynn Adler and Jim Wolf, “Update 1—Israel, U.S. Sign $2.75 Billion F-35 Deal,” Reuters, October 7, 2010, https://www.reuters.com/article/israelusa-f-35-idUSN0717986420101008 (accessed May 5, 2022), and Defense Industry Daily Staff, “Adir Who? Israel’s F-35i Stealth Fighters,” Defense Industry Daily, August 11, 2021, https://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/israel-plans-to-buy-over-100-f35s-02381/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 52. Judah Ari Gross, “IDF Says It Launched Major Offensive on Dozens of Rocket Launch Tubes in Gaza,” The Times of Israel, May 11, 2021, https:// www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/idf-says-it-launched-major-offensive-on-dozens-of-rocket-launch-tubes-in-gaza/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 53. Blaise Misztal and Patty-Jane Geller, “Congress Overdue to Help Fund Israel’s Iron Dome,” The Washington Times, February 15, 2022, https://www. washingtontimes.com/news/2022/feb/15/congress-overdue-to-help-fund-israels-iron-dome/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 54. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2022), pp. 366–369. 55. News release, “Lockheed Martin Awarded Contract to Build F-16 Block 70 Aircraft for Bahrain,” Lockheed Martin, June 25, 2018, https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2018-06-25-Lockheed-Martin-Awarded-Contract-to-Build-F-16-Block-70-Aircraft-for-Bahrain?_ ga=2.3223408.1543096780.1588692655-1467716092.1546629521 (accessed May 5, 2022). 56. Reuters, “Qatar Goes Ahead with $6.7 Billion Typhoon Combat Jets Deal with UK’s BAE Systems,” December 10, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/ article/us-britain-qatar-typhoons/qatar-goes-ahead-with-6-7-billion-typhoon-combat-jets-deal-with-uks-bae-systems-idUSKBN1E40QM (accessed May 5, 2022). 57. James Phillips, Nicole Robinson, and John Venable, “F-35 Sale to UAE Advances U.S. Security Interests,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 6032, December 10, 2020, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/f-35-sale-uae-advances-us-security-interests. 58. U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, Combined Maritime Forces—U.S. 5th Fleet, “Combined Maritime Forces,” https://www.cusnc.navy.mil/ Combined-Maritime-Forces/ (accessed May 5, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 155 50. See, for example, Gil Press, “6 Reasons Israel Became a Cybersecurity Powerhouse Leading the $82 Billion Industry,” Forbes, July 18, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2017/07/18/6-reasons-israel-became-a-cybersecurity-powerhouse-leading-the-82-billionindustry/#d458614420aa (accessed May 5, 2022), and NoCamels Team, “Israel Is a Small Country, but a Cyber Superpower, Says Ex-CIA Director at CyberTech 2018,” NoCamels, January 20, 2018, http://nocamels.com/2018/01/israel-cyber-superpower-cia-cybertech-2018/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 59. Helene Cooper and Anne Barnard, “Jordan and Emirates Carry out Airstrikes in Syria Against ISIS,” The New York Times, February 10, 2015, www. nytimes.com/2015/02/11/world/middleeast/united-arab-emirates-resume-airstrikes-against-isis.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 60. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 336. 61. GlobalSecurity.org, “Egypt Military Guide: Introduction,” last modified April 4, 2012, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/egypt/intro. htm (accessed May 5, 2022). 62. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 319. 63. Reuters and Jack Khoury, “Isis Claims Responsibility for Attack That Killed 15 Egyptian Military Personnel,” Haaretz, February 16, 2019, https://www. haaretz.com/middle-east-news/egypt/15-egyptian-military-personnel-killed-or-wounded-in-sinai-attack-army-says-1.6938947 (accessed May 5, 2022), and Jason Hanna, Michael Martinez, and Jennifer Deaton, “ISIS Publishes Photo of What It Says Is Bomb that Downed Russian Plane,” CNN, updated November 19, 2015, https://www.cnn.com/2015/11/18/middleeast/metrojet-crash-dabiq-claim/index.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 64. MEE Correspondent in Cairo, “Egypt: Sinai Residents Asked to Return as Army and Tribes Curb Islamic State Group,” Middle East Eye, April 21, 2022, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/egypt-sinai-residents-return-army-tribes-curb-is-presence (accessed May 5, 2022). 65. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022, p. 351. 66. See, for example, Florence Gaub, “An Unhappy Marriage: Civil–Military Relations in Post-Saddam Iraq,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Middle East Center, January 13, 2016, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/ACMR-Gaub-final.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 67. Reuters, “Iraq Says It Found 50,000 ‘Ghost Soldiers’ on Payroll,” December 1, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-iraqsoldiers-idUSKCN0JF2RZ20141201 (accessed May 5, 2022). 68. Ned Parker, Isabel Coles, and Raheem Salman, “Special Report: How Mosul Fell—An Iraqi General Disputes Baghdad’s Story,” Reuters, October 14, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-gharawi-special-report/special-report-how-mosul-fell-an-iraqi-general-disputesbaghdads-story-idUSKCN0I30Z820141014 (accessed May 5, 2022). 69. Tim Arango and Michael R. Gordon, “Iraqi Prime Minister Arrives in Mosul to Declare Victory over ISIS,” The New York Times, July 9, 2017, https:// www.nytimes.com/2017/07/09/world/middleeast/mosul-isis-liberated.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 70. Nicole Robinson and Eric Feely, “What a Firebrand Cleric’s Growing Strength Means for American Policy in Iraq,” The Daily Signal, December 2, 2021, https://www.dailysignal.com/2021/12/02/what-a-firebrand-clerics-growing-strength-means-for-american-policy-in-iraq. 71. During 1967 and 1990, South Yemen, officially known as the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, was a socialist state in the southeastern provinces of the present-day Republic of Yemen. 72. U.S. Central Command, “About Us: U.S. Central Command History,” https://www.centcom.mil/ABOUT-US/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 73. Ibid. 74. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph P. Englehardt, Desert Shield and Desert Storm: A Chronology and Troop List for the 1990–1991 Persian Gulf Crisis, U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute Special Report AD-A234 743, March 25, 1991, p. 5, https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a234743. pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 75. Associated Press, “A Timeline of Iraq War, Troop Levels,” Internet Archive, updated May 25, 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20141023033147/ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2008/04/07/a-timeline-of-iraq-war-tr_n_95534.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 76. BBC News, “Iraq War in Figures,” December 14, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-11107739 (accessed May 5, 2022). 77. Reuters, “Timeline: Invasion, Surge, Withdrawal; U.S. Forces in Iraq,” December 18, 2011, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-usa-pullout/ timeline-invasion-surge-withdrawal-u-s-forces-in-iraq-idUSTRE7BH08E20111218 (accessed May 5, 2022). 78. Christopher M. Blanchard, “Iraq and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. 10404, updated January 20, 2022, https:// crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10404 (accessed May 5, 2022). 79. Gordon Lubold and Michael C. Bender, “U.S. to Remove Patriot Missile Batteries from Saudi Arabia,” The Wall Street Journal, updated May 7, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-to-remove-patriot-missile-batteries-from-saudi-arabia-11588867916 (accessed May 5, 2022). 80. J. P. Lawrence, “US Troop Level Reduction in Middle East Likely as Focus Shifts Elsewhere,” Stars and Stripes, January 14, 2022, https://www. stripes.com/theaters/middle_east/2022-01-14/centcom-central-command-drawdown-iraq-afghanistan-kuwait-saudi-arabia-4289137.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 81. Matthew Wallin, “U.S. Bases and Military Facilities in the Middle East,” American Security Project Fact Sheet, June 2018, https://www. americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Ref-0213-US-Military-Bases-and-Facilities-Middle-East.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 82. Kenneth Katzman, “Kuwait: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RS21513, updated May 12, 2021, pp. 8–11, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/RS21513.pdf (accessed May 10, 2022). 83. Kenneth Katzman, “The United Arab Emirates (UAE): Issues for U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RS21852, updated October 28, 2021, pp. 14–16, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/mideast/RS21852.pdf (accessed May 10, 2022). 84. Kenneth Katzman, “Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RS21534, updated May 19, 2021, p. 14, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS21534 (accessed May 10, 2022). 156 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 85. Kenneth Katzman, “Bahrain: Issues for U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RS951013, updated March 10, 2022, pp. 10–11, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/95-1013 (accessed May 10, 2022). 86. Christopher M. Blanchard, “Saudi Arabia: Background and U.S. Relations,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL33533, updated October 5, 2021, pp. 25-26, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33533 (accessed May 10, 2022). 87. Captain Marie Harnley, “Wing Leadership Visits Eskan Village,” U.S. Air Forces Central, July 5, 2013, http://www.afcent.af.mil/ Units/379thAirExpeditionaryWing/News/Display/tabid/5382/Article/350180/wing-leadership-visits-eskan-village.aspx (accessed May 5, 2022). 88. Kenneth Katzman, “Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. R44533, updated April 11, 2022, pp. 13–14, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44533 (accessed May 10, 2022). 89. U.S. Army Central, “Eager Lion,” STAND-TO! The Official Focus of the U.S. Army, April 11, 2018, https://www.army.mil/standto/2018-04-11 (accessed May 5, 2022). 90. Jeremy M. Sharp, “Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL33546, updated May 5, 2022, pp. 15–16, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33546 (accessed May 10, 2022). 91. U.S. Central Command, “About Us: CENTCOM Mission and Command Priorities,” https://www.centcom.mil/ABOUT-US/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 92. Louisa Brook-Holland, “UK Forces in the Middle East Region,” House of Commons Library Briefing Paper No. 08794, January 14, 2020, p. 2, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8794/CBP-8794.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 93. Ibid., p. 3. 94. Malak Harbarb), “U.K. Opens Persian Gulf Military Base in Bahrain,” Associated Press, April 5, 2018, https://apnews.com/ article/403eea90b7054edaa978c0e51fd182c4 (accessed May 5, 2022). 95. U.K. Ministry of Defence and The Rt. Hon. Sir Michael Fallon, MP, “Multi-Million Pound Joint Venture Announced Between Britain and Oman,” March 30, 2016, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/multi-million-pound-joint-venture-announced-between-britain-and-oman (accessed May 5, 2022). 96. Frank Gardner, “‘East of Suez’: Are UK Forces Returning?” BBC News, April 29, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-22333555 (accessed May 5, 2022). 97. Harriet Alexander, “Where Are the World’s Major Military Bases?” The Telegraph, July 11, 2013, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/ defence/10173740/Where-are-the-worlds-major-military-bases.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 99. French Defense Attaché Office, Embassy of France to the United States, “French Armed Forces Update,” May 2021, https://franceintheus.org/ IMG/pdf/FAFU/FAFU_008b.pdf (accessed May 5, 2022). 100. James Hirst, “UK to Increase Military Training Presence in Iraq,” Forces.Net, February 18, 2021, https://www.forces.net/news/iraq/uk-increasemilitary-training-presence-iraq (accessed May 5, 2022). 101. U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “Today in Energy: The Bab el-Mandeb Strait Is a Strategic Route for Oil and Natural Gas Shipments,” August 27, 2019, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=41073 (accessed May 5, 2022). 102. U.S. Navy, Commander, Navy Installations Command, “Welcome to Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti: Installation Information,” https://www.cnic.navy. mil/regions/cnreurafcent/installations/camp_lemonnier_djibouti.html (accessed May 5, 2022). 103. Associated Press, “The New Military Powerhouse on the Red Sea: Tiny Djibouti,” Haaretz, April 10, 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/middle-eastnews/the-new-military-powerhouse-on-the-red-sea-tiny-djibouti-1.5990505 (accessed May 5, 2022). 104. Donna Miles, “Centcom Undertakes Massive Logistical Drawdown in Afghanistan,” Armed Forces Press Service, June 21, 2013, https://defence.pk/ pdf/threads/centcom-undertakes-massive-logistical-drawdown-in-afghanistan.259682/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 105. Percentages calculated based on data in U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook: Country Comparisons—Roadways,” https://www. cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/roadways/country-comparison/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 106. Zvi Mazel, “China’s Growing Economic Impact on the Middle East,” Geopolitical Intelligence Services Report, April 21, 2022, https://www. gisreportsonline.com/r/china-middle-east/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 107. Katzman, “Bahrain: Issues for U.S. Policy,” pp. 11 and 20, and Katzman, “The United Arab Emirates (UAE): Issues for U.S. Policy,” p. 19. 108. Katzman, “The United Arab Emirates (UAE): Issues for U.S. Policy,” p. 18. 109. Katzman, “Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy,” p. 14. 110. Martin Placek, “Number of Ships Passing Through the Suez Canal from 1976 to 2021,” Statista, March 31, 2022, https://www.statista.com/ statistics/1252568/number-of-transits-in-the-suez-cana-annually/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 111. Michael Wahid Hanna, “Getting over Egypt: Time to Rethink Relations,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 94, No. 6 (November/December 2015), https://www. foreignaffairs.com/articles/egypt/getting-over-egypt (accessed May 5, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 157 98. Government of France, Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, “Country Files: United Arab Emirates,” updated May 14, 2019, https://www. diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/united-arab-emirates/# (accessed May 5, 2022), and International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2021: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2022), p. 376. 112. Associated Press, “US Carrier Crosses Suez Canal into Red Sea,” The Times of Israel, November 8, 2013, http://www.timesofisrael.com/us-carriercrosses-suez-canal-into-red-sea/ (accessed May 5, 2022). 113. Brent Sadler, “What the Closing of the Suez Canal Says About U.S. Maritime Security,” Heritage Foundation Commentary, April 12, 2021, https:// www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/what-the-closing-the-suez-canal-says-about-us-maritime-security. 114. U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “The Strait of Hormuz Is the World’s Most Important Oil Transit Chokepoint,” December 27, 2019, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=42338 (accessed May 10, 2022). 115. Statista Research Department, “Oil Flows Through the Strait of Hormuz Between 2014 and 2020 (in Million Barrels per Day),” April 6, 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/277157/key-figures-for-the-strait-of-hormuz/ (accessed May 10, 2022). 116. United States Institute of Peace, “Timeline: U.S.–Iran Naval Encounters,” The Iran Primer, updated November 15, 2021, https://iranprimer.usip.org/ blog/2021/may/05/timeline-us-iran-naval-encounters#:~:text=The%20most%20recent%20incidents%20were,and%20Iran%20in%20a%20year (accessed May 4, 2022). 117. U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, “Today in Energy: Three Important Oil Trade Chokepoints Are Located Around the Arabian Peninsula,” August 4, 2017, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=32352 (accessed May 10, 2022). 118. Seth J. Frantzman, “Is Iran’s Influence in Iraq Growing, or Has It Reached a Plateau?” The Jerusalem Post, January 2, 2019, https://www.jpost. com/Middle-East/Is-Irans-influence-in-Iraq-growing-or-has-it-reached-a-plateau-576104 (accessed May 4, 2022). 119. See, for example, World Bank, “Logistics Performance Index: Quality of Trade and Transport-Related Infrastructure (1=Low to 5=High),” 2007–2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/lp.lpi.infr.xq (accessed May 4, 2022). 158 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Asia Jeff Smith, Dean Cheng, Bruce Klingner, and Walter Lohman E l China (third); l Japan (fourth); l South Korea (sixth); l Taiwan (eighth); l India (ninth); and l Vietnam (10th). America’s economic connections with these countries and others in the region and beyond contribute to a closely integrated global economy characterized by ties in production, finance, services, information, and investment. When one part of the system sneezes, other parts of the economic body get sick—as demonstrated recently and most starkly by the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact of that crisis on both supply and demand, especially with respect to technology, continues to affect defense planning, budgeting, and production in the United States and across the region. Tensions in the U.S.–China economic relationship have had a similar impact. Economics is central to understanding political dynamics in Asia, but that is not the only important consideration. Several of the world’s largest militaries are there, including those of China, India, North and South Korea, Pakistan, Russia, and Vietnam. The United States also maintains a network of treaty alliances and security partnerships, as well as a significant military presence, in Asia, and five Asian states (China, North Korea, India, Pakistan, and Russia) possess nuclear weapons. The region is a focus of American security concerns both because of its substantial military forces and because of its legacy of conflict. Both of the two major “hot” wars fought by the United States during the Cold War (Korea and Vietnam) were fought in Asia. Moreover, the Asian security environment is unstable. For one thing, the Cold War has not ended in Asia. Of the four states divided between Communism and democracy by the Cold War, three (China, Korea, and Vietnam) are in Asia. Neither the Korean situation nor the China–Taiwan situation has been The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 159 ver since the founding of the American Republic, Asia has been a key U.S. area of interest for both economic and security reasons. One of the first ships to sail under an American flag was the aptly named Empress of China, which inaugurated America’s participation in the lucrative China trade in 1784. In the more than 235 years since then, the United States has held to the strategic assumption that allowing any single nation to dominate Asia would be inimical to American interests. Asia is too important a market and too great a source of key resources for the United States to be denied access. Thus, beginning with U.S. Secretary of State John Hay’s “Open Door” policy toward China in the 19th century, the United States has worked to prevent the rise of a regional hegemon in Asia, whether it was imperial Japan or the Soviet Union. In the 21st century, Asia’s importance to the United States will continue to grow. Asia is a key source of vital natural resources and a crucial part of the global value chain in areas like electronic components. Through 2021, six of America’s top 10 trading partners were found in Asia:1 resolved despite the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Cold War itself was an ideological conflict layered atop long-standing—and still lingering— historical animosities. Asia is home to several major territorial disputes, among them disputes between or among: l l l l l l l Japan and Russia (Northern Territories/ Southern Kurils); Japan, China, and Taiwan (Senkakus/Diaoyutai/Diaoyu Dao); Korea and Japan (Dok-do/Takeshima); Vietnam, China, and Taiwan (Paracels/Xisha Islands); China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and the Philippines (Spratlys/Nansha Islands); India and Pakistan (Kashmir); and India and China (Aksai Chin and parts of the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh). Several of these unresolved differences could devolve into war. Chinese air and sea incursions around Taiwan—especially since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—have generated increased concern about Taiwan’s survival as an independent nation. The situation on the Korean Peninsula is perpetually tense. And China’s increasingly aggressive presence at sea is bringing Beijing ever closer to conflict with the U.S. military and the forces of its treaty allies and security partners. On the China–India border, the two sides have come to blows in recent years. It is in light of this instability and the reluctance of many states in the region to align with great powers that one should weigh the region’s lack of a political–security architecture. There is no Asian equivalent of NATO despite an ultimately failed mid-20th century effort to forge a parallel multilateral security architecture through the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Regional security entities like the Five Power Defense Arrangement (involving the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, and Singapore in a peacetime “arrangement” rather than an alliance) or discussion forums like 160 the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and groupings like the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting-Plus (ADMM-Plus) have been far weaker. There also is no Asian equivalent of the Warsaw Pact. Instead, Asian security has been marked by a combination of bilateral alliances, mostly centered on the United States, and individual nations’ efforts to maintain their own security. In recent years, these core aspects of the regional security architecture have been supplemented by “minilateral” consultations like the U.S.–Japan–Australia and India–Japan– Australia trilaterals and the U.S.–Japan–Australia– India quadrilateral dialogue (popularly known as “the Quad”). Nor is Asia undergirded by any significant economic architecture. Despite substantial trade and expanding value chains among the various Asian states, as well as with the rest of the world, formal economic integration is limited. There are many trade agreements among the nations of the region and among these nations and countries outside of Asia, most prominently the 15-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and 11-nation Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), but there is no counterpart to the European Union or even to the European Economic Community or the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to European economic integration. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is a far looser agglomeration of disparate states, although they have succeeded in expanding economic linkages among themselves over the past 50 years through a range of economic agreements like the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA). The South Asia Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC), which includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, has been less important to regional stability. It is largely ineffective, both because of the lack of regional economic integration and because of the historical rivalry between India and Pakistan. Important Alliances and Bilateral Relations in Asia The keys to America’s position in the Western Pacific are its alliances with Japan, the Republic of Korea (ROK), the Philippines, Thailand, and Australia, supplemented by very close security relationships with New Zealand and Singapore, an emerging 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Japan. The U.S.–Japan defense relationship is the linchpin of America’s network of relations in the Western Pacific. The U.S.–Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, signed in 1960, provides for a deep alliance between two of the world’s largest economies and most sophisticated military establishments. Changes in Japanese defense policies are now enabling an even greater level of cooperation on security issues, both between the two allies and with other countries in the region. Since the end of World War II, Japan’s defense policy has been distinguished by Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, which states in part that “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.”2 In effect, this article prohibits the use of force by Japan’s governments as an instrument of national policy. It also has led to several other associated policies. One such policy was a prohibition against “collective self-defense.” Japan recognized that nations have a right to employ their armed forces to help other states defend themselves (in other words, to engage in collective defensive operations) but rejected that policy for itself: Japan would employ its forces only in defense of Japan. This changed in 2015. Japan passed legislation that enabled its military to exercise limited collective self-defense in certain cases involving threats to both the U.S. and Japan as well as in multilateral peacekeeping operations. In recent years, Japan has increased its security cooperation with other Indo-Pacific democracies. This cooperation has included enhancing security agreements, participating in more multilateral military exercises, and providing ships to Southeast Asian coast guard forces. Tokyo relies heavily on the United States—and Washington’s extended deterrence guarantee of nuclear, conventional, and missile defense forces— for its security. Japan has developed a formidable military by implementing significant changes in security legislation and procuring an impressive array of sophisticated weapons. Yet because of its pacifist constitution and the devastation wrought by its quest for regional dominance in World War II, progress in altering Japan’s security posture has always lagged behind faster-moving regional threats. The Japanese people remain deeply suspicious of any use of the military as a policy instrument—and fearful that any easing of constraints will lead Japan The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 161 strategic partnership with India, and evolving relationships with Southeast Asian partners like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The U.S. also has a robust unofficial relationship with Taiwan. The United States also benefits from the interoperability gained from sharing common weapons and systems with many of its allies. Many nations, for example, have equipped their ground forces with M-16/M-4–based infantry weapons and share the same 5.56 mm ammunition; they also field F-15 and F-16 combat aircraft and employ LINK-16 data links among their naval forces. Australia, Japan, and South Korea are partners in production of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, and all three countries have taken delivery of the aircraft. Partners like India and Australia operate American-made P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft and C-17 transport aircraft. Consequently, in the event of conflict, the region’s various air, naval, and even land forces would be able to share information in such key areas as air defense and maritime domain awareness. This advantage is enhanced by the constant ongoing range of both bilateral and multilateral exercises, which acclimate various forces to operating together and familiarize both American and local commanders with each other’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), as well as training, tactics, and (in some cases) war plans. In addition, “enabling” military agreements allow the United States and several of its regional partners to access each other’s military facilities, share intelligence and encrypted communications and equipment, and refuel each other’s warships at sea. While it does not constitute a formal alliance, in November 2017, Australia, Japan, India, and the U.S. reconstituted the Quad. Officials from the four countries agreed to meet in the quadrilateral format twice a year to discuss ways to strengthen strategic cooperation and combat common threats. In 2019, the group held its first meeting at the ministerial level and added a counterterrorism tabletop exercise to its agenda. In 2020, officials from the four countries participated in a series of conference calls to discuss responses to the COVID-19 pandemic that also included government representatives from New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam. In March 2021, the leaders of the four nations held their first virtual summit, marking a new level of interaction. In September 2021, the four leaders held the first in-person Quad summit; it is expected that a second will be held in Japan during 2022. into military conflict. Each incremental step in expanding the role of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces has therefore been immensely controversial. As part of its relationship with Japan, the United States maintains some 54,000 military personnel and another 8,000 Department of Defense (DOD) civilian employees in Japan under the rubric of U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ).3 These forces include, among other things, a forward-deployed carrier battle group centered on the USS Ronald Reagan; an amphibious ready group at Sasebo centered on the LHA-6 America, an aviation-optimized amphibious assault ship; and the bulk of the Third Marine Expeditionary Force (III MEF) on Okinawa. U.S. forces exercise regularly with their Japanese counterparts, and this collaboration has expanded in recent years to include joint amphibious exercises in addition to air and naval exercises. The American presence is supported by a substantial American defense infrastructure throughout Japan, including Okinawa. These major bases provide key logistical and communications support for U.S. operations throughout the Western Pacific, cutting travel time substantially compared with deployments from Hawaii or the West Coast of the United States. They also provide key listening posts for the monitoring of Russian, Chinese, and North Korean military operations. This capability is supplemented by Japan’s growing array of space systems, including new reconnaissance satellites. The Japanese government “pays roughly $2 billion per year to defray the cost of stationing U.S. military personnel in Japan.”4 These funds cover approximately 75 percent of the cost of deployed U.S. forces,5 including the costs of utility and labor at U.S. bases, improvements in U.S. facilities in Japan, and relocation of training exercises away from populated areas in Japan. Japan paid nearly all of the cost of new U.S. military facilities at Futenma and Iwakuni as well as a third of the cost of new facilities in Guam. It also purchases 90 percent of its weapons and defense systems from the United States.6 During bilateral Special Measures Agreement negotiations, the Trump Administration sought a 400 percent increase in Japanese contributions for remuneration above the cost of stationing U.S. troops in Japan. In January 2022, the Biden Administration reached an agreement with Japan on a new five-year cost-sharing agreement that includes incremental 162 increases in Japanese funding, thereby resolving a major irritant in the bilateral relationship.7 The United States has long sought to expand Japanese participation in international security affairs. Japan’s political system, grounded in the country’s constitution, legal decisions, and popular attitudes, has generally resisted this effort. However, in recent years, Tokyo has become increasingly alarmed by China’s surging defense expenditures, rapidly expanding and modernizing military capabilities, and escalating aerial and maritime incursions into Japan’s territorial waters and contiguous areas. In response, Japan has reoriented its forces so that they can better counter the Chinese threat to its remote southwest islands. It also has acquired new capabilities, built new facilities, deployed new units and augmented others, improved its amphibious warfare capabilities, increased its air and sea mobility, and enhanced its command-and-control capabilities for joint and integrated operations. Recently, the growing potential for a Taiwan crisis has led senior Japanese officials to issue increasingly bold public statements of support for Taipei and more directly align Japan’s national interests with the protection of Taiwan’s security. As yet, however, there have been no declared Japanese policy changes and no pledge to intervene directly in a military conflict to defend Taiwan or even to allow U.S. defense of Taiwan from bases in Japan. Similarly, heightened Japanese concern about the growing North Korean missile and nuclear threats has triggered a resurgence of debate about whether the country should augment its defenses by acquiring strike capabilities, which would enable Japan to conduct an attack against targets in an opponent’s country. Japan’s legal interpretation of what is allowed under its peace constitution is not static. It has evolved in response to increasing regional threats, Japan’s improving military capabilities, and Tokyo’s perception of the strength of its alliance with Washington. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has stated that Japan should consider building a missile-strike capability as a “viable option” against China and North Korea, to be implemented in response to initial attacks.8 Pursuing strike capabilities would be the subject of great controversy—both among the Japanese people and among the people of neighboring countries—and would require deft public diplomacy to overcome strong resistance to such a significant 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength centered mainly on the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division, rotating brigade combat teams, and a significant number of combat aircraft. The U.S.–ROK defense relationship involves one of the more integrated and complex command-and-control structures. A United Nations Command (UNC) established in 1950 was the basis for the American intervention and remained in place after the armistice was signed in 1953. UNC has access to seven bases in Japan to support U.N. forces in Korea. In concrete terms, however, it oversaw only South Korean and American forces as other nations’ contributions were gradually withdrawn or reduced to token elements. Although the 1953 armistice ended the Korean War, UNC retained operational control (OPCON) of South Korean forces until 1978, when it was transferred to the newly established Combined Forces Command (CFC). Headed by the American Commander of U.S. Forces Korea, who is also Commander, U.N. Command, CFC reflects an unparalleled degree of U.S.–South Korean military integration. CFC returned peacetime OPCON of South Korean forces to Seoul in 1994. If war became imminent, South Korean forces would become subordinate to the CFC commander, who in turn remains subordinate to both countries’ national command authorities. In 2007, then-President Roh Moo-hyun requested that the United States return wartime OPCON of South Korean forces to Seoul. This decision engendered significant opposition within South Korea and raised serious military questions about the transfer’s impact on unity of command. Faced with various North Korean provocations, including a spate of missile tests as well as attacks on South Korean military forces and territory in 2010, Washington and Seoul agreed in late 2014 to postpone wartime OPCON transfer and adopt a conditions-based rather than timeline-based policy. After wartime OPCON transfer, the CFC commander would be a South Korean general with a U.S. general as deputy commander. The U.S. general would continue to serve as commander of UNC and U.S. Forces Korea (USFK). The CFC commander, regardless of nationality, would always remain under the direction and guidance of U.S. and South Korean political and military national command authorities. President Moon Jae-in advocated for an expedited OPCON transition during his administration, but critical conditions, including improvement in South The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 163 shift in Japan’s post–World War II security posture. Although this is now being discussed more openly by politicians, Japanese strike capability is still only at the theoretical debate stage. Tokyo has yet to articulate strike policy, strategy, a doctrine of employment, triggering events, procurement, deployment, or how offensive systems would train in Japan. Contentious historical issues from Japan’s brutal 1910–1945 occupation of the Korean Peninsula have been serious enough to torpedo efforts to improve defense cooperation between Seoul and Tokyo. South Korean–Japanese relations took a major downturn in 2018 when the South Korean Supreme Court ruled that Japanese companies could be forced to pay occupation reparations. In December 2018, an incident between a South Korean naval ship and a Japanese air force plane further exacerbated tensions. Japan responded in July 2019 by imposing restrictions on exports to South Korea of three chemicals that are critical to the production of semiconductors and smartphones.9 Seoul then threatened to withdraw from the bilateral General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), which enables the sharing of classified intelligence and military information on the North Korean nuclear and missile threat. The Moon Jae-in administration relented and maintained the agreement, but there was public criticism of U.S. pressure. The election of new leaders in South Korea and Japan has raised hopes that it might be possible to reduce tensions by separating difficult historic issues from the necessity of addressing present-day security threats. Prime Minister Kishida was responsible for two Japanese–South Korean agreements10 while he served as foreign minister, and South Korean President Yoon Seok-youl, elected in March 2022, has vowed to build a “future-oriented relationship” with Japan.11 Republic of Korea. The United States and the Republic of Korea signed their Mutual Defense Treaty in 1953. That treaty codified the relationship that had grown from the Korean War, when the United States dispatched troops to help South Korea defend itself against invasion by Communist North Korea. Since then, the two states have forged an enduring alliance supplemented by a substantial trade and economic relationship that includes a free trade agreement. The U.S. is committed to maintaining 28,500 troops on the Korean Peninsula. This presence is Korean forces and a decrease in North Korea’s nuclear program, have yet to be met.12 President Yoon Seok-youl, elected in March 2009, criticized Moon’s push for a premature return of wartime OPCON from United Nations Command before Seoul had fulfilled the agreed-upon conditions. The domestic political constraints under which South Korea’s military operates are less stringent than those that govern the operations of the Japanese military. South Korea has fought alongside the United States in every conflict since the Korean War. Seoul sent 300,000 troops to the Vietnam War, and 5,000 of them were killed. At one point, it fielded the third-largest troop contingent in Iraq after the United States and Britain. It also has conducted anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia and has participated in peacekeeping operations in Afghanistan, East Timor, and elsewhere. South Korean defense planning remains focused on North Korea, especially as Pyongyang has deployed its forces in ways that optimize a southward advance and has carried out several penetrations of ROK territory by ship, submarine, commandos, and drones. The sinking of the South Korean frigate Cheonan and shelling of Yongpyeong-do in 2010, which together killed 48 military personnel, wounded 16, and killed two civilians, have only heightened concerns about North Korea. In response to Pyongyang’s expanding nuclear strike force, South Korea created a “3K” tiered defense strategy comprised of Kill Chain (preemptive attack); the Korea Air and Missile Defense (KAMD) system; and the Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR) system. The South Korean military is a sizeable force with advanced weapons and innovative military education and training. South Korean military spending has increased, and Seoul appears to be procuring the right mix of capabilities. U.S.–South Korean interoperability has improved, partly because of continued purchases of U.S. weapons systems. Over the past several decades, the American presence on the peninsula has slowly declined. In the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon withdrew the 7th Infantry Division, leaving only the 2nd Infantry Division on the peninsula. Those forces have been positioned farther back so that few Americans are now deployed on the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Traditionally, U.S. military forces have engaged regularly in major exercises with their ROK 164 counterparts, including the Key Resolve and Foal Eagle series, both of which involved the deployment of substantial numbers of forces and were intended partly to deter Pyongyang as well as to give U.S. and ROK forces a chance to practice operating together. However, after the 2018 U.S.–North Korean Summit, President Donald Trump announced unilaterally that he was cancelling major bilateral military exercises because he thought they were provocative and expensive.13 The President made this decision without consulting the DOD, U.S. Forces Korea, or allies South Korea and Japan. During the next four years, the U.S. and South Korea cancelled numerous exercises and imposed constraints on additional exercises. North Korea did not reciprocate with any diplomatic gesture or military constraints in response to this unilateral U.S. concession. The outbreak of COVID-19 in South Korea in 2020 led to the additional curtailment of training activity, raising the possibility that allied deterrence and defense capabilities could be further degraded. In March 2022, the U.S. conducted its first aircraft carrier exercise near Korea since 2018, and the Biden Administration appears likely to resume large-scale allied military exercises in South Korea.14 The ROK government provides substantial resources to defray the costs of U.S. Forces Korea. The bilateral, cost-sharing Special Measures Agreement has offset the non-personnel costs of stationing U.S. forces in South Korea since 1991 and is renegotiated every five years. In February 2019, South Korea agreed to increase its share of the cost by approximately 8 percent to $924 million. Later in 2019, President Trump demanded a fivefold increase of $5 billion a year and threatened to reduce or remove U.S. forces from South Korea. In April 2021, the Biden Administration signed an agreement accepting an incremental increase in Seoul’s contribution in line with previous agreements, thereby defusing tensions within the alliance. South Korea spends 2.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense—more than is spent by any European ally. Seoul absorbs costs not covered in the cost-sharing agreement, including $10 billion, or 93 percent, of the cost of constructing Camp Humphreys, the largest U.S. base on foreign soil. During the past four years, South Korea has purchased $13 billion in arms from the United States.15 The Philippines. America’s oldest defense relationship in Asia is with the Philippines. The 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Task Force–Philippines (JSOTF–P), ended during the first part of 2015. The U.S. presence in Mindanao continued at a reduced level until the Trump Administration, alarmed by the terrorist threat there, began Operation Pacific Eagle–Philippines (OPE–P). The presence of 200–300 American advisers proved very valuable to the Philippines in its 2017 battle against Islamist insurgents in Marawi.16 Continued on-the-ground military assistance for the counterterrorism challenge in Mindanao and other security cooperation in the Philippines received a boost in July 2021 when the Philippines, during a visit by American Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, retracted its intention to abrogate the 1998 U.S.–Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA). Since February 2020, the VFA has operated on serial six-month extensions offered by the Philippine President. An instrument of the MDT, the VFA specifies the procedures governing the deployment of U.S. forces and equipment to the Philippines. It also governs the application of domestic Philippine law to U.S. personnel, which is the most substantive part of the VFA and historically its most controversial. The VFA undergirds approximately 280 U.S.– Philippine annual exercises—more than are conducted with any other military in Southeast Asia. Its abrogation would have slowed the rate of these interactions, conditioned their composition, and exposed each element of them to political pressures in the Philippines. Its preservation, on the other hand, not only sheds these constraints, but also enables the expansion of cooperation. The most recent example was the conduct of annual Balikatan exercises, billed by both sides as the largest ever held.17 The U.S. embassy reported deployment of “nearly 9,000” troops, “more than 50 aircraft, four ships, 10 amphibious craft, four HIMARS rocket system launchers, and four Patriot missile systems” as well as “approximately 40 personnel from the Australian Defense Force.”18 The U.S. and the Philippines have also resumed plans for base improvement and sharing arrangements under the 2014 U.S.–Philippine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA).19 The U.S. government has long made it clear that any attack on Philippine government ships or aircraft or on the Philippine armed forces—for example, by China—would be covered under the U.S.–Philippine mutual defense treaty.20 This makes The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 165 United States seized the Philippines from the Spanish more than a century ago as a result of the Spanish–American War and a subsequent conflict with indigenous Philippine nationalist forces. Unlike other colonial powers, however, the U.S. put in place a mechanism by which the Philippines could transition through a period as a commonwealth until receiving full independence in 1946. Just as important, substantial numbers of Filipinos fought alongside the United States against Japan in World War II, establishing a bond between the two peoples. Following World War II and after assisting the newly independent Filipino government against the Communist Hukbalahap movement in the 1940s, the United States and the Philippines signed a mutual defense treaty (MDT). For much of the period between 1898 and the end of the Cold War, the largest American bases in the Pacific were in the Philippines, centered on the U.S. Navy base in Subic Bay and the complex of airfields that developed around Clark Field (later Clark Air Base). While the Philippines have never had the ability to provide substantial financial support for the American presence, the unparalleled base infrastructure provided replenishment and repair facilities and substantially extended deployment periods throughout the East Asian littoral. These bases, being reminders of the colonial era, were often centers of controversy. In 1991, a successor to the Military Bases Agreement between the U.S. and the Philippines was submitted to the Philippine Senate for ratification. After a lengthy debate, the Philippines rejected the treaty, thereby compelling American withdrawal from Philippine bases. Given the effects of the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, which devastated Clark Air Base and damaged many Subic Bay facilities, and the end of the Cold War, it was not felt that closure of the bases would fundamentally damage America’s posture in the region. Moreover, despite the closing of the American bases and consequent slashing of American military assistance, U.S.–Philippine military relations remained close, and assistance began to increase again after 9/11 as U.S. forces supported Philippine efforts to counter Islamic terrorist groups, including the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), in the South of the archipelago. From 2002–2015, the U.S. rotated 500–600 special operations forces regularly through the Philippines to assist in counterterrorism operations. That operation, Joint Special Operations it incumbent on the U.S., consistent with its constitutional procedures, to come to the defense of the Philippines. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken reiterated this commitment in two separate calls with the Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs in January and April 2021.21 Secretary of Defense Austin made a similar statement in September, also reiterating the treaty’s application to the South China Sea, an issue that was once subject to some doubt.22 Thailand. The U.S.–Thai security relationship is built on the 1954 Manila Pact, which established the now-defunct SEATO, and the 1962 Thanat–Rusk agreement.23 These were supplemented by the Joint Vision Statements for the Thai–U.S. Defense Alliance of 2012 and 2020.24 In addition, Thailand gained improved access to American arms sales in 2003 when it was designated a “major, non-NATO ally.” Thailand’s central location has made it an important part of the network of U.S. alliances in Asia. During the Vietnam War, American aircraft based in Thailand ranged from fighter-bombers and B-52s to reconnaissance aircraft. In the first Gulf War and again in the Iraq War, some of those same air bases were essential for the rapid deployment of American forces to the Persian Gulf. Access to these bases remains critical to U.S. global operations. U.S. and Thai forces exercise together regularly, most notably in the annual Cobra Gold exercises, which were initiated in 1982. This builds on a partnership that began with the dispatch of Thai forces to the Korean War, during which Thailand lost more than 1,200 of the approximately 6,000 troops it had deployed. The Cobra Gold exercise is the world’s longest-running international military exercise25 and one of its largest. The most recent, in 2022, although again scaled back because of concern for the COVID pandemic, involved 1,200 American troops and 2,000 Thai troops26 as well as participants from a range of other countries, including India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, and Australia.27 For many years, a small number of Chinese personnel have also participated. Because of pandemic concerns, “[a]ctivities like live fire drills, amphibious landings and evacuation operations” were excluded.28 In contrast to the close relations between their militaries, U.S.–Thailand political relations have been strained since 2006. A coup that year and another in 2014 limited military-to-military relations for more than 10 years. This was due partly to standing U.S. law prohibiting assistance to governments 166 that result from coups against democratically elected governments and partly to policy choices by the U.S. government. The U.S. and Thailand, however, have managed to salvage much of their military-to-military cooperation and now look to normalize relations. This has been made possible by two developments: elections in 2019, which led to a new civilian government, and Washington’s new strategic focus on great-power competition with China. As a result, the U.S. accepted the flawed Thai electoral model as an opportunity to encourage the relationship. This encompassed high-level engagement and arms transfers to the Thai military of major systems like Stryker armored vehicles and Black Hawk helicopters. Under the Biden Administration, this trend may lead to the sale of the F-35.29 Over several decades, amid uncertainty in the U.S. commitment to the relationship, Thailand has been drifting geopolitically away from the U.S. and toward China. This process has been accelerating partly because of expanding economic relations between the two states and partly because of complications in U.S.–Thai relations arising from the political situation in Thailand and a general difference in threat perception concerning China. The U.S. considers China its greatest long-term security challenge; Thailand has no such concern. Relations between the Thai and Chinese militaries have improved steadily over the years. Intelligence officers began formal meetings in 1988. Thai and Chinese military forces have engaged in joint naval exercises since 2005, joint counterterrorism exercises since 2007, and joint marine exercises since 2010 and conducted their first joint air force exercises in 2015.30 The Thais conduct more bilateral exercises with the Chinese than are conducted by any other military in Southeast Asia.31 The Thais also have been buying Chinese military equipment for many years. Purchases in recent years have included significant buys of battle tanks and armored personnel carriers.32 According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), from 2006–2021, China has been a significantly bigger supplier than the U.S.33 These deals, however, have not been without difficulty. Thailand’s 2017 acquisition of submarines, for example, has been stalled first by a combination of budget restraints, the priority of COVID-19 response, and public protest34 and more recently by Germany’s 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength include “fifth generation integration, aircraft maintenance integration, aeromedical evacuation (AME) integration, refuelling certification, and combined technical skills and logistics training.”41 It has been accompanied by the buildout of related infrastructure at Australian bases and, of note most recently, a massive fuel storage facility in Darwin.42 Other improvements are underway at training areas and ranges in Australia’s Northern Territories.43 In 2021, the U.S., Australia, and the U.K., which already enjoyed close security cooperation, moved bilaterally and in the context of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing arrangement to formalize and deepen these ties through the Australia–United Kingdom– United States partnership (AUKUS). This trilateral partnership is focused on current defense-related technology. Central to and most immediate among its stated priorities is support for Australia’s acquisition of “a conventionally armed, nuclear powered submarine capability at the earliest possible date, while upholding the highest nonproliferation standards.”44 The White House has reported either “strong progress” or “recently initiated work” in several areas beyond submarine technology, which is already underway. These areas include (among others) undersea robotic autonomous systems, quantum technologies, artificial intelligence, and hypersonic capabilities.45 This new, cutting-edge cooperation under the USFPI and AUKUS comes on top of long-standing joint U.S.–Australia training, the most prominent example of which is Talisman Saber. These biannual exercises involve U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines as well as almost two-dozen ships, multiple civilian agencies, and participants embedded from other partner countries.46 COVID forced the 2021 iteration to downsize, but the 2019 version included more than 34,000 personnel from the U.S. and Australia. Singapore. Singapore is America’s closest non-ally partner in the Western Pacific. The agreements that support this security relationship are the 2015 U.S.–Singapore Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA), which is an update of a similar 2005 agreement, and the 1990 Memorandum of Understanding Regarding United States Use of Facilities in Singapore, which was renewed in 2019 for another 15 years. Pursuant to these agreements and other understandings, Singapore hosts U.S. naval ships and aircraft as well as the principal logistics support node for the U.S. Seventh Fleet. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 167 refusal to allow export of the engines the boats require.35 Submarines could be particularly critical to Sino–Thai relations because their attendant training and maintenance will require a greater Chinese military presence at Thai military facilities. Australia. Australia is one of America’s most important allies in the Indo-Pacific. U.S.–Australia security ties date back to World War I when U.S. forces fought under Australian command on the Western Front in Europe, and they deepened during World War II when, after Japan commenced hostilities in the Western Pacific (and despite British promises), Australian forces committed to the North Africa campaign were not returned to defend the continent. As Japanese forces attacked the East Indies and secured Singapore, Australia turned to the United States to bolster its defenses, and American and Australian forces cooperated closely in the Pacific War. Those ties and America’s role as the main external supporter of Australian security were codified in the Australia–New Zealand–U.S. (ANZUS) pact of 1951. Today, the two nations’ chief defense and foreign policy officials meet annually (most recently in August 2020) in the Australia–United States Ministerial (AUSMIN) process to address such issues of mutual concern as security developments in the Asia–Pacific region, global security and development, and bilateral security cooperation.36 Australia also has long granted the United States access to a number of joint facilities, including space surveillance facilities at Pine Gap, which has been characterized as “arguably the most significant American intelligence-gathering facility outside the United States,”37 and naval communications facilities on the North West Cape of Australia.38 In 2011, cooperation and U.S. access were expanded with the U.S. Force Posture Initiatives (USFPI), which included Marine Rotational Force–Darwin and Enhanced Air Cooperation. The rotation of up to 2,500 U.S. Marines for a set of six-month exercises near Darwin, Australia, began in 2012. The current rotation is comprised of 2,200 Marines39 and an Army detachment.40 In the past, these forces have deployed with assets including a tilt-rotor MV-22 Osprey squadron, UH-1Y Venom utility and AH-1Z Viper attack helicopters, and RQ-21A Blackjack drones. The USFPI’s Enhanced Air Cooperation component began in 2017 building on preexisting schedules of activity. New activities under the initiative Singapore trains approximately 1,000 military personnel in the United States each year on such American-produced equipment as F-15SG and F-16C/D fighter aircraft and CH-47 Chinook and AH-64 Apache helicopters.47 Along with American allies Australia, Japan, and South Korea, Singapore also has ordered and been approved to buy the F-35.48 Like others of its assets, the F-35s will be housed at training facilities in the U.S.49 and perhaps on Guam under an agreement reached in 2019.50 New Zealand. For much of the Cold War, U.S. defense ties with New Zealand were similar to those between America and Australia. In 1986, however, as a result of controversies over U.S. Navy employment of nuclear power and the possible deployment of U.S. naval vessels with nuclear weapons, the U.S. suspended its obligations to New Zealand under the 1951 ANZUS Treaty. Defense relations improved in the early 21st century as New Zealand committed forces to Afghanistan and dispatched an engineering detachment to Iraq. The 2010 Wellington Declaration and 2012 Washington Declaration, while not restoring full security ties, allowed the two nations to resume high-level defense dialogues.51 As part of this warming of relations, New Zealand rejoined the multinational U.S.-led RIMPAC (Rim of the Pacific) naval exercise in 2012 and has participated in each iteration since then. In 2013, U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and New Zealand Defense Minister Jonathan Coleman announced the resumption of military-to-military cooperation, and in July 2016, the U.S. accepted an invitation from New Zealand to make a single port call, reportedly with no change in U.S. policy to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons on the ship.52 At the time of the visit in November 2016, both sides claimed to have satisfied their respective legal requirements.53 The prime minister expressed confidence that the vessel was not nuclear-powered and did not possess nuclear armaments, and the U.S. neither confirmed nor denied this. The November 2016 visit occurred in a unique context, including an international naval review and a relief response to the Kaikoura earthquake. Since then, there have been several other ship visits by the U.S. Coast Guard, and in 2017, New Zealand lent the services of one its naval frigates to the U.S. Seventh Fleet following a deadly collision between the destroyer USS Fitzgerald and a Philippine container 168 ship that killed seven American sailors. Another U.S. naval warship did not visit New Zealand until November 2021, when the guided-missile destroyer USS Howard made a port call.54 New Zealand is a member of the elite Five Eyes intelligence alliance with the U.S., Canada, Australia, and the U.K.55 Taiwan. When the United States shifted its recognition of the government of China from the Republic of China (on Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China (PRC, the mainland), it also declared certain commitments concerning the security of Taiwan. These commitments are embodied in the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) and the subsequent “Six Assurances.” The TRA is an American law, not a treaty. Under the TRA, the United States maintains programs, transactions, and other relations with Taiwan through the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT). Except for the Sino–U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty, which had governed U.S. security relations with Taiwan and was terminated by President Jimmy Carter following the shift in recognition to the PRC, all other treaties and international agreements made between the Republic of China and the United States remain in force. Under the TRA, it is U.S. policy “to provide Taiwan with arms of a defensive character.”56 The TRA also states that the U.S. “will make available to Taiwan such defense articles and services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.”57 The U.S. has implemented these provisions of the act through sales of weapons to Taiwan. The TRA states that it is also U.S. policy “to consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States” and “to maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”58 To this end: The President is directed to inform the Congress promptly of any threat to the security or the social or economic system of the people on Taiwan and any danger to the interests of the United States arising therefrom. The President 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength and the Congress shall determine, in accordance with constitutional processes, appropriate action by the United States in response to any such danger.59 Supplementing the TRA are the “Six Assurances” issued by President Ronald Reagan in a secret July 1982 memo, later publicly released and the subject of hearings held by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in August 1982.60 These assurances were intended to moderate the third Sino–American communiqué, itself generally seen as one of the “Three Communiqués” that form the foundation of U.S.–PRC relations. These assurances of July 14, 1982, were that: In negotiating the third Joint Communiqué with the PRC, the United States: 1. Although the United States sells Taiwan a variety of military equipment and sends observers to its major annual exercises, it does not engage in joint exercises with Taiwan’s armed forces. Some Taiwan military officers, however, attend professional military education institutions in the United States. There also are regular high-level meetings between senior U.S. and Taiwan defense officials, both uniformed and civilian. The United States does not maintain any bases in Taiwan. However, in late 2021, after reports of an uptick in the number of U.S. military advisers in Taiwan, Taiwan’s President acknowledged their presence,62 going back at least to 2008.63 The numbers involved are in the dozens64 with most of these advisers involved in the provision of training on U.S.-sourced military equipment. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 169 has not agreed to set a date for ending arms sales to Taiwan; 2. has not agreed to hold prior consultations with the PRC on arms sales to Taiwan; 3. will not play any mediation role between Taipei and Beijing; 4. has not agreed to revise the Taiwan Relations Act; 5. has not altered its position regarding sovereignty over Taiwan; 6. will not exert pressure on Taiwan to negotiate with the PRC.61 Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. On a region-wide basis, the U.S. has two major ongoing defense-related initiatives to expand its relationships and diversify the geographical spread of its forces. The Maritime Security Initiative is intended to improve the security capacity of U.S. partners, and the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) bolsters America’s military presence and makes it more accountable. Among the most important of the bilateral partnerships in this effort, beyond those listed above, are Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. None of these relationships is as extensive and formal as America’s relationship with Singapore, India, and U.S. treaty allies, but all are of growing significance. Since shortly after the normalization of diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1995, the U.S. and Vietnam also have gradually normalized their defense relationship. The relationship was codified in 2011 with a Memorandum of Understanding Advancing Bilateral Defense Cooperation. In 2015, the MOU was updated with the Joint Vision Statement on Defense Cooperation, which includes references to such issues as “defense technology exchange,”65 and was implemented under a three-year 2018–2020 Plan of Action for United States–Viet Nam Defense Cooperation that was agreed upon in 2017.66 According to USINDOPACOM’s 2022 command posture statement, the U.S. and Vietnam “are expected to issue a new Defense Cooperation Plan of Action for 2022–2024 and an updated Defense MOU Annex codifying new cooperation areas, including defense trade, pilot training, cyber, and personnel accounting (POW/MIA).”67 The most significant development with respect to security ties over the past several years has been relaxation of the ban on sales of arms to Vietnam. The U.S. lifted the embargo on maritime security–related equipment in the fall of 2014 and then ended the embargo on arms sales completely in 2016. The embargo had long served as a psychological obstacle to Vietnamese cooperation on security issues; lifting it, however, has not changed the nature of the articles that are likely to be sold. Transfers to date have been to the Vietnamese Coast Guard. These include provision under the Excess Defense Articles (EDA) program of two decommissioned Hamilton-class cutters, with a possible third on the way,68 and 24 Metal Shark patrol boats as well as infrastructure support.69 Vietnam is scheduled to take delivery of six unmanned Boeing-made Scan Eagle aerial vehicles (UAVs) for its Coast Guard.70 The U.S. is also providing T-6 turboprop trainer aircraft.71 Agreement has yet to be reached with respect to sales of bigger-ticket items like refurbished P-3 maritime patrol aircraft, although they have been discussed. The U.S.–Vietnam Cooperative Humanitarian and Medical Storage Initiative (CHAMSI) is designed to enhance cooperation on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief by, among other things, prepositioning related American equipment in Da Nang, Vietnam.72 This is a sensitive issue for Vietnam and is not often referenced publicly, but it was emphasized during Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc’s visit to Washington in 2017 and again during Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s visit to Vietnam in 2018. In the same year, Vietnam participated in RIMPAC for the first time. It did not participate in the exercise in 2020, when it was scaled down because of COVID-19,73 or in 2022. There have been two high-profile port calls to Vietnam since 2018. Early that year, the USS Carl Vinson visited Da Nang with its escort ships in the first port call by a U.S. aircraft carrier since the Vietnam War, and another carrier, USS Theodore Roosevelt, visited Da Nang in March 2020. These are significant signals from Vietnam about its receptivity to partnership with the U.S. military—messages underscored very subtly in Vietnam’s 2019 Viet Nam National Defence white paper.74 Nevertheless, significant limits on the U.S.–Vietnam security relationship persist, including a Vietnamese defense establishment that is very cautious in its selection of defense partners, party-to-party ties between the Communist Parties of Vietnam and China, and a Vietnamese foreign policy that seeks to balance relationships with all major powers. The U.S., like others among Vietnam’s security partners, remains officially restricted to one port call a year with an additional one to two calls on Vietnamese bases being negotiable. The U.S. and Malaysia, despite occasional political differences, “have maintained steady defense cooperation since the 1990s.” Examples of this cooperation include Malaysian assistance in the reconstruction of Afghanistan and involvement in anti-piracy operations “near the Malacca Strait and…off the Horn of Africa” as well as “jungle warfare training at a Malaysian facility, bilateral exercises like Kris Strike, and multilateral exercises like Cobra Gold, 170 which is held in Thailand and involves thousands of personnel from several Asian countries plus the United States.”75 The U.S. has occasionally flown P-3 and/or P-8 patrol aircraft out of Malaysian bases in Borneo. The U.S. relationship with Malaysia was strengthened under President Barack Obama and continued on a positive trajectory under the Trump Administration. In addition to cooperation on counterterrorism, the U.S. is focused on helping Malaysia to ensure maritime domain awareness. In 2020, then-Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for South and Southeast Asia Reed B. Werner summarized recent U.S. assistance in this area: [M]aritime domain awareness is important for Malaysia, given where it sits geographically. Since 2017, we have provided nearly US$200 million (RM853 million) in grant assistance to the Malaysian Armed Forces to enhance maritime domain awareness, and that includes ScanEagle unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), maritime surveillance upgrades, and longrange air defence radar.76 The upgrading of its F-18 fleet is the most significant U.S. defense program currently underway with Malaysia.77 Malaysia reportedly also “is hoping to buy Kuwait’s entire fleet of Boeing F/A-18 Hornet multi-role fighter jets, although discussions between both governments over the sale have yet to begin.”78 The U.S.–Indonesia defense relationship was revived in 2005 following a period of estrangement caused by American concerns about human rights. It now includes regular joint exercises, port calls, and sales of weaponry. Because of their impact on the operating environment in and around Indonesia, as well as the setting of priorities in the U.S.–Indonesia relationship, the U.S. has also worked closely with Indonesia’s defense establishment to reform Indonesia’s strategic defense planning processes. U.S.–Indonesia military cooperation is governed by the 2010 Framework Arrangement on Cooperative Activities in the Field of Defense and the 2015 Joint Statement on Comprehensive Defense Cooperation79 as well as the 2010 Comprehensive Partnership. These agreements have encompassed “more than 200 bilateral military engagements a year” and cooperation in six areas: “maritime security and domain awareness; defense procurement 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength government. In February 2020, Ambassador Khalilzad and Taliban co-founder and chief negotiator Abdul Ghani Baradar signed a tentative peace agreement in which the Taliban agreed that it would not allow al-Qaeda or any other transnational terrorist group to use Afghan soil. It also agreed not to attack U.S. forces as long as they provided and remained committed to a withdrawal timeline, eventually set at May 2021. In April 2021, President Joseph Biden announced that the U.S. would be withdrawing its remaining 2,500 soldiers from Afghanistan by September 11, 2021, remarking that America’s “reasons for remaining in Afghanistan are becoming increasingly unclear.”87 As the final contingent of U.S. forces was leaving Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban launched a rapid offensive across the country, seizing provincial capitals and eventually the national capital, Kabul, in a matter of weeks. During the Taliban offensive, President Ghani fled the country for the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the Afghan security forces largely abandoned their posts.88 Having left the air force base at Bagram in July, the U.S. and other countries were left trying to evacuate their citizens and allies from the Kabul International Airport as the Taliban assumed control of the capital. Amid the chaos, a suicide bombing attack on the airport perimeter on August 26 killed 13 U.S. military personnel and nearly 200 Afghans. IS-K, the local branch of ISIS, claimed responsibility for the attack, and the Biden Administration subsequently launched drone strikes on two IS-K targets.89 The last U.S. forces were withdrawn on August 30, 2021. Early in September, the Taliban formed a new government comprised almost entirely of hardline elements of the Taliban and Haqqani Network, including several individuals on the U.S. government’s Specially Designated Global Terrorists list.90 Sirajuddin Haqqani, arguably the most powerful figure in the new Afghan government, carries a $10 million U.S. bounty. Since seizing power, the Taliban government has hunted down and executed hundreds of former government officials and members of the Afghan security forces. It also has cracked down on Afghanistan’s free press, banned education for girls beyond sixth grade while the daughters of several Taliban leaders attend school in Pakistan and the UAE, and curtailed the rights of women and minorities. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 171 and joint research and development; peacekeeping operations and training; professionalization; HA/DR [High Availability/Disaster Recovery]; and countering transnational threats such as terrorism and piracy.”80 In 2021, the agreements framed new progress in the relationship that included breaking ground on a new coast guard training base,81 inauguration of a new Strategic Dialogue,82 and the largest-ever U.S.– Indonesia army exercise.83 This exercise, Garuda Shield, involved a combined 4,500 troops. In a major 2022 development, the U.S. agreed to sell Indonesia up to 36 F-15s and related equipment and munitions worth $14 billion.84 As of March 2021, the U.S. “ha[d] $1.88 billion in active government-to-government sales cases with Indonesia under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system.”85 The U.S. and Indonesia also have signed two of the four foundational information-sharing agreements that the U.S. maintains with its closest partners: the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) and Communications Interoperability and Security Memorandum of Agreement (CISMOA). Afghanistan. On October 7, 2001, U.S. forces invaded Afghanistan in response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. This marked the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom to combat al-Qaeda and its Taliban supporters. The U.S., in alliance with the U.K. and the anti-Taliban Afghan Northern Alliance forces, ousted the Taliban from power in December 2001. Most Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders fled across the border into Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas where they regrouped and initiated an insurgency in Afghanistan in 2003. In August 2003, NATO joined the war in Afghanistan and assumed control of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). In 2011, at the height of the war, there were 50 troop-contributing nations and nearly 150,000 NATO and U.S. forces on the ground in Afghanistan. On December 28, 2014, NATO formally ended combat operations and relinquished responsibility to the Afghan security forces, which numbered around 352,000 (including army and police).86 In 2018, U.S. Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad initiated talks with the Taliban in Doha, Qatar, in an attempt to find a political solution to the conflict and encourage the group to negotiate with the Afghan Like most of the world’s other governments, the U.S. government has refused to offer the new Taliban government diplomatic recognition. In October 2021, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Colin Kahl admitted that both al-Qaeda and ISIS-K were operating in Afghanistan with the intent to conduct terrorist attacks abroad, including against the U.S. Specifically, Kahl estimated that “[w]e could see ISIS-K generate that capability in somewhere between 6 or 12 months” and that “Al Qaeda would take a year or two to reconstitute that capability.”91 Pakistan. During the early stages of the war in Afghanistan, the U.S. and NATO relied heavily on logistical supply lines running through Pakistan to resupply anti-Taliban coalition forces. Supplies and fuel were carried on transportation routes from the port at Karachi to Afghan–Pakistani border crossing points at Torkham in the Khyber Pass and Chaman in Baluchistan province. For roughly the first decade of the war, approximately 80 percent of U.S. and NATO supplies traveled through Pakistani territory. Those amounts progressively decreased as the U.S. and allied troop presence shrank. By the late 2000s, tensions emerged in the relationship over accusations by U.S. analysts and officials that Pakistan was providing a safe haven to the Taliban and its allies as they intensified their insurgency in Afghanistan. The Taliban’s leadership council or “shura” was located in Quetta, the capital of Pakistan’s Baluchistan province. With relations already tense, U.S.–Pakistan relations suffered an acrimonious rupture in 2011 when U.S. special forces conducted a raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout in Abbottabad less than a mile from a prominent Pakistani military academy. Relations deteriorated further in 2017 when President Donald Trump suspended billions of dollars of U.S. military assistance to Pakistan and declared that “[w]e can no longer be silent about Pakistan’s safe havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban, and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond.”92 Between 2001 and 2016, Pakistan received approximately $30 billion in aid and “reimbursements” from the U.S. in the form of coalition support funds (CSF) for its military deployments and operations along the border with Afghanistan. In 2016, reflecting the growing congressional resistance to military assistance for Pakistan, Congress blocked funds for the provision of eight F-16s. According to the Congressional Research Service, U.S. aid appropriations 172 and military reimbursements have fallen continuously since fiscal year (FY) 2013; CSF reimbursements fell to zero in FY 2017 and remained at that level through FY 2020.93 Since 2015, U.S. Administrations have refused to certify that Pakistan has met requirements to crack down on the Haqqani Network, an Afghan terrorist group with known links to Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency.94 In addition to suspending aid, the Trump Administration supported the addition of Pakistan to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) “grey list” for failing to fulfill its obligations to prevent the financing of terrorism and its designation as a “Countr[y] of Particular Concern under the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 for having engaged in or tolerated ‘systematic, ongoing, [and] egregious violations of religious freedom.”95 Pakistan remains on the grey list in 2022. Despite harboring and supporting a variety of known terrorist groups that operate in Afghanistan and Kashmir, Pakistan has also been the victim of terrorism from anti-state extremist groups, including the Pakistani Taliban or TTP. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the TTP engaged in a bloody campaign of terrorism against the Pakistani state; from 2008–2013, approximately 2,000 civilians were killed in terrorist attacks each year.96 The Pakistan military launched a series of operations against these groups in 2014 and succeeded in progressively reducing terrorist violence in the years that followed.97 However, since the Afghan Taliban assumed power in Kabul, the number of attacks on Pakistan civilian and military targets has spiked dramatically98 with the TTP and the local affiliate of the Islamic State taking credit for most of these attacks. Islamabad has repeatedly accused the Taliban government in Kabul of harboring these groups or failing to rein in their activities. Tensions reached a tipping point in April 2022 when the Taliban accused Pakistan of launching cross-border raids into Afghanistan to target these militant groups, causing dozens of civilian casualties in the process.99 Pakistan–U.S. relations improved modestly from 2018–2021 as Pakistan involved itself as a key player in bringing the Afghan Taliban to the negotiating table with the U.S. government. However, relations remained generally frosty and have improved little under the Biden Administration, with President Biden reportedly refusing to engage in direct 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Initiative (NTI) in 2018, with only Iran’s and North Korea’s ranking less secure at 21st and 22nd, respectively.102 In its 2020 report, the NTI assessed that the “[m]ost improved among countries with materials in 2020 is Pakistan, which was credited with adopting new on-site physical protection and cybersecurity regulations, improving insider threat prevention measures, and more.”103 There is the additional (though less likely) scenario of extremists gaining access through a collapse of the state. While Pakistan remains unstable because of its weak economy, regular terrorist attacks, sectarian violence, civil–military tensions, and the growing influence of religious extremist groups, a total collapse of the Pakistani state is highly unlikely. The country’s most powerful institution, the 550,000-strong army that has ruled Pakistan for almost half of its existence, would almost certainly intervene and assume control once again if the political situation began to unravel. The potential breakup of the Pakistani state would have to be preceded by the disintegration of the army, which currently is not plausible. Pakistan–India Conflict. India and Pakistan have fought four wars since partition in 1947, including conflicts in 1947, 1965, 1971, and 1999. Deadly border skirmishes across the Line of Control (LoC) in Kashmir, a disputed territory claimed in full by both India and Pakistan, are commonplace. With terrorist groups operating relatively freely in Pakistan and maintaining links to its military and intelligence services, there is a moderate risk that the two countries might eventually engage in all-out conflict. Pakistan’s recent focus on incorporating tactical nuclear weapons into its warfighting doctrine has also raised concern that conflict now involves a higher risk of nuclear exchange. In early 2019, Pakistan conducted several tests of its nuclear-capable, short-range NASR ballistic missiles.104 The military and strategic dynamic between India and Pakistan has grown more volatile since the May 2014 election of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader Narendra Modi as India’s prime minister. Modi invited Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to his swearing-in ceremony, but in August 2014, the two sides engaged in intense firing and shelling along their international border and the Line of Control that divides Kashmir. A similar escalation in border tensions occurred again in October 2014 when a series of firing incidents claimed The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 173 communications with Prime Minister Imran Khan and Pakistan declining an invitation to attend President Biden’s December 2021 Summit for Democracy. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman visited Pakistan in October 2021 to discuss “the importance of holding the Taliban accountable to the commitments they have made.” Days earlier, she noted: “We don’t see ourselves building a broad relationship with Pakistan. And we have no interest in returning to the days of hyphenated India–Pakistan.”100 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Stockpile. In September 2021, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists estimated that Pakistan “now has a nuclear weapons stockpile of approximately 165 warheads.” The report added that “[w]ith several new delivery systems in development, four plutonium production reactors, and an expanding uranium enrichment infrastructure, however, Pakistan’s stockpile…could grow to around 200 warheads by 2025, if the current trend continues.”101 The possibility that terrorists could gain effective access to Pakistani nuclear weapons is contingent on a complex chain of circumstances. Concern about the safety and security of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons increases when India–Pakistan tensions increase. If Pakistan were to move its nuclear assets or (worse) take steps to mate weapons with delivery systems, the likelihood of theft or infiltration by terrorists could increase. Increased reliance on tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) is of particular concern because launch authorities for TNWs are typically delegated to lower-tier field commanders far from the central authority in Islamabad. Another concern is the possibility that miscalculations could lead to regional nuclear war if India’s leaders were to lose confidence that nuclear weapons in Pakistan are under government control or, conversely, were to assume that they were under Pakistani government control after they ceased to be. There are additional concerns that Islamist extremist groups with links to the Pakistan security establishment could exploit those links to gain access to nuclear weapons technology, facilities, and/ or materials. The realization that Osama bin Laden stayed for six years within a mile of Pakistan’s premier defense academy has fueled concern that al-Qaeda can operate relatively freely in parts of Pakistan. Pakistan’s weapons-grade materials were ranked the 19th least secure by the Nuclear Threat more than a dozen casualties with several dozen more injured.105 On December 25, 2015, Modi made an impromptu visit to Lahore—the first visit to Pakistan by an Indian leader in 12 years—to meet with Sharif. The visit created enormous goodwill between the two countries and raised hope that official dialogue would soon resume. Again, however, violence marred the new opening. One week after the meeting, militants attacked an Indian airbase at Pathankot, killing seven Indian security personnel.106 A comprehensive India–Pakistan dialogue has remained frozen ever since, although the two governments still regularly communicate with one another. New Delhi has insisted that Pakistan take concrete verifiable steps to crack down on terrorist groups before a comprehensive dialogue covering all outstanding issues—including the Kashmir dispute—can resume. Unfortunately, the past few years have been marred by additional terrorist attacks and cross-border shelling. The Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) terrorist group was responsible for a January 2, 2016, attack on the Indian airbase at Pathankot, a February 2018 attack on an Indian army camp in Kashmir, and a February 2019 attack on Indian security forces in Kashmir—the deadliest single terrorist attack in the disputed region since the eruption of an insurgency in 1989.107 Following a deadly attack on Indian security forces in Pulwama, Kashmir, in February 2019, India launched an even more daring cross-border raid. For the first time since the Third India–Pakistan War of 1971, the Indian air force crossed the LoC and dropped ordnance inside Pakistan proper (as opposed to disputed Kashmir), targeting several JeM training camps in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.108 Delhi stressed that the “non-military” operation was designed to avoid civilian casualties and was preemptive in nature because India had credible intelligence that JeM was attempting other suicide attacks in the country. In response, Pakistan launched fighter jets to conduct their own strike on targets located on India’s side of the LoC in Kashmir, prompting a dogfight that resulted in the downing of an Indian MiG-21. Pakistan released the captured MiG-21 pilot days later, ending the brief but dangerous crisis. Nevertheless, both militaries continued to engage in artillery attacks along the disputed border throughout 2019. 174 Pakistan reported more than 45 casualties, including 14 soldiers, from Indian shelling between January 2019 and October 2019. India reported 21 casualties and over 2,000 cease-fire violations during the same period.109 Skirmishes at the LoC continued and even accelerated in 2020 with India’s Home Ministry registering “5,133 instances of ceasefire violations along the Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan last year, which resulted in 46 fatalities.”110 In early 2021, however, India and Pakistan experienced at least a partial diplomatic thaw as both countries combated the COVID-19 global pandemic. In February, both countries agreed to observe a strict cease-fire along the LOC,111 and in March, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, declared in a speech that “it is time to bury the past and move forward.”112 In March 2022, India accidentally fired a cruise missile into Pakistan. The unarmed missile flew roughly 100 kilometers into Pakistan and crashed harmlessly without casualties. The Indian government blamed a “technical malfunction” during “routine maintenance.”113 Pakistan called the launch irresponsible and demanded a “joint probe to accurately establish the facts” in a response that one correspondent characterized as “measured.”114 India. During the Cold War, U.S.–Indian military cooperation was minimal except for a brief period during and after the China–India border war in 1962 when the U.S. provided India with supplies, arms, and ammunition. The rapprochement was shortlived, and the U.S. suspended arms and aid to India following the Second Indo–Pakistan War of 1965. The relationship was largely characterized by mistrust in the 1970s under the Nixon Administration. America’s ties with India hit a nadir during the Third Indo–Pakistan war of 1971 when the U.S. deployed the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise toward the Bay of Bengal in a show of support for Pakistani forces. Months earlier, India had signed a major defense treaty with Moscow. India’s close defense ties to Russia and America’s close defense ties to Pakistan left the two countries estranged for the duration of the Cold War. Military ties between the U.S. and India have improved significantly over the past two decades (particularly since the signing of a 10-year defense partnership and civil nuclear deal in 2005) as the two sides have established a robust strategic partnership based on mutual concerns about China’s increasingly belligerent behavior and converging 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Operations from Ships Other Than Aircraft Carriers (HOSTAC) and an Industrial Security Annex (ISA) that allows the U.S. to share classified information with private Indian defense firms. During the Trump Administration, the two countries also initiated a new 2+2 defense and foreign ministers dialogue while reviving the Quad grouping (which joins India and the U.S. with Australia and Japan) in 2017.117 In 2020, the four countries held the first Quad naval exercise since 2007. When a deadly crisis erupted at the China–India border in 2020, the Trump Administration provided India with two advanced surveillance drones and cold-weather gear for Indian soldiers. In recent years, India has made additional purchases of U.S. military hardware, including C-17 transport aircraft, Apache attack helicopters, MH60R Seahawk multi-mission helicopters, Sig Sauer assault rifles, and M777 ultralight howitzer artillery guns. It also is reportedly considering the purchase of 30 armed MQ-9 reaper drones (10 each for the three branches of its military) for $3 billion and a half-dozen highly capable P-8I maritime aircraft (to supplement the dozen currently in operation) for nearly $2 billion. New Delhi and Washington regularly hold joint annual military exercises across all services. They include the Yudh Abhyas army exercises, Red Flag air force exercises, and Malabar naval exercise, which added Japan and Australia as permanent participants in 2012 and 2020, respectively. In late 2019, India and the U.S. held their first-ever tri-service military exercise, nicknamed “Tiger Triumph.” At the April 2022 2+2 defense and foreign policy dialogue, which was held in Washington, the two sides signed “a Space Situational Awareness arrangement” and “agreed to launch an inaugural Defense Artificial Intelligence Dialogue.” They also committed to exploring the coproduction of Air-Launched Unmanned Aerial Vehicles under the Defense Trade and Technology Initiative (DTTI). In addition, India agreed “to join the Combined Maritime Forces Task Force…to expand multilateral cooperation in the Indian Ocean,” and the two sides agreed to “explore possibilities of utilizing Indian shipyards for repair and maintenance of ships of the U.S. Maritime Sealift Command to support mid-voyage repair of U.S. Naval ships.”118 The U.S. Department of Defense assessed that these initiatives “will allow the U.S. and Indian militaries to work more seamlessly together The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 175 interests in countering regional terrorism and promoting a “free and open Indo-Pacific.”115 The U.S. has supplied India more than $25 billion worth of U.S. military equipment since 2008, including C-130J and C-17 transport aircraft, P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft, Chinook airlift helicopters, Apache attack helicopters, artillery batteries, and Firefinder radar. The two countries also have several information-sharing and intelligence-sharing agreements in place, including one that covers “white” or commercial shipping in the Indian Ocean. Defense ties have advanced at an accelerated rate since the election of Prime Minister Modi in 2014. In 2015, the U.S. and India agreed to renew and upgrade their 10-year Defense Framework Agreement. In 2016, the two governments finalized the text of the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA), which allows each country to access the other’s military supplies and refueling capabilities through ports and military bases, and the U.S. designated India a “major defense partner,” a designation unique to India that is intended to facilitate its access to American defense technology. Since then, Indian and U.S. warships have begun to offer each other refueling and resupply services at sea.116 In October 2020, U.S. P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft were refueled for the first time at an Indian military base in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. America’s strategic and defense ties with India advanced in several important ways during the Trump Administration. In 2018, India was granted STA-1 status, easing controls on exports of advanced defense technology. India is only the third Asian country after Japan and South Korea to be granted STA-1 status. In the same year, India established a permanent naval attaché representative to U.S. Central Command in Bahrain, fulfilling a long-standing request from New Delhi. In 2018, the two countries also signed the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA), which will allow the U.S. to sell India encrypted communications equipment and create secure channels for communication between the Indian and U.S. militaries. In 2020, the U.S. and India signed the Basic Exchange Cooperation Agreement (BECA), which creates a framework for the sharing of geospatial intelligence. Beyond these “foundational” or “enabling” military agreements, in recent years, the two countries have also signed an agreement on Helicopter across all domains of potential conflict” and “jointly meet the challenges of this century.”119 Quality of Key Allied or Partner Armed Forces in Asia Because Asia lacks an integrated, regional security architecture along the lines of NATO, the United States partners with most of the region’s nations on a bilateral basis. This means that there is no single standard to which all local militaries aspire; instead, the region is characterized by a wide range of capabilities that are influenced by local threat perceptions, institutional interests, physical conditions, historical factors, and budgetary considerations. Moreover, most Asian militaries have limited combat experience, particularly in high-intensity air or naval combat. Some, like Malaysia, have never fought an external war since gaining independence in the mid-20th century. The Indochina wars, the most recent high-intensity conflicts, are now more than 50 years in the past. It is therefore unclear how well Asia’s militaries have trained for future warfare and whether their doctrine will meet the exigencies of wartime realities. Based on examinations of equipment, however, we assess that several Asian allies and friends have substantial potential military capabilities that are supported by robust defense industries and significant defense spending. The defense budgets of Japan, South Korea, and Australia are estimated to be among the world’s 15 largest, and the three countries’ military forces field some of the world’s most advanced weapons, including F-15s in the Japan Air Self Defense Force and ROK Air Force; airborne early warning (AEW) platforms; Aegis-capable surface combatants and modern diesel-electric submarines; and third-generation main battle tanks. As noted, all three nations are also involved in the production and purchase of F-35 fighters. At this point, both the Japanese and Korean militaries arguably are more capable than most European militaries, at least in terms of conventional forces. Japan’s Self Defense Forces, for example, field more tanks, principal surface combatants, and combat-capable aircraft than their British counterparts field. Similarly, South Korea fields more tanks, principal surface combatants, and combat-capable aircraft than Germany fields. Both the ROK and Japan are also increasingly interested in developing missile defense capabilities, 176 including joint development and coproduction in the case of Japan. After much negotiation and indecision, South Korea deployed America’s Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system on the peninsula in 2017. It is also pursuing an indigenous missile defense capability. As for Japan, its Aegis-class destroyers are equipped with SM-3 missiles, and it decided in 2017 to install the Aegis Ashore missile defense system to supplement its Patriot missile batteries.120 In June 2020, Tokyo unexpectedly cancelled plans to build two Aegis Ashore missile defense sites, citing the potential for the interceptor missile’s first-stage booster to fall onto populated areas. Other likely factors in the decision include the overall cost of the program, inept handling of the site-selection process, and government unwillingness to press national objectives over local resistance.121 Currently, Tokyo plans to build an additional two Aegis-capable ships to compensate for the cancellation of the Aegis Ashore project. Australia also has very capable armed forces. They are smaller than NATO militaries but have major operational experience, having deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan as well as to help the Philippines with its Southern insurgency. Australia’s military has several operations underway in the region from the Southwest Pacific islands, which are so critically important to it, to its partnership with Malaysia in the North Indian Ocean and South China Sea, to the Korean Peninsula.122 Singapore’s small population and physical borders limit the size of its military, but in terms of equipment and training, it has Southeast Asia’s largest defense budget123 and fields some of the region’s highest-quality forces. Singapore’s ground forces can deploy third-generation Leopard II main battle tanks, and its fleet includes four conventional submarines (to be replaced by four new, more capable submarines from Germany)124 and six frigates and eight missile-armed corvettes. Its air force has F-15E Strike Eagles and F-16s as well as one of Southeast Asia’s largest fleets of airborne early warning and control aircraft (G550-AEW aircraft) and a squadron of KC-130 tankers that can help to extend range or time on station.125 In January 2020, the U.S. Department of State cleared Singapore to purchase “four short-takeoff-and-vertical-landing F-35 variants with an option for eight more of the ‘B’ models.” Delivery is scheduled to begin in 2026.126 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 50 percent of the world’s population and include two of the three largest economies and nine of the 10 smallest; the most populous nation (China); the largest democracy (India); the largest Muslim-majority nation (Indonesia); and the world’s smallest republic (Nauru). The region is a vital driver of the global economy and includes the world’s busiest international sea-lanes and nine of its 10 largest ports. By any meaningful measure, the Indo-Pacific is also the world’s most militarized region, with “seven of the world’s ten largest standing militaries and five of the world’s declared nuclear nations.”133 INDOPACOM has several “component and sub-unified commands”134 that include: l l Current U.S. Presence in Asia U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. Established in 1947 as U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM), USINDOPACOM is the oldest and largest of America’s unified commands. According to its website: USINDOPACOM protects and defends, in concert with other U.S. Government agencies, the territory of the United States, its people, and its interests. With allies and partners, USINDOPACOM is committed to enhancing stability in the Asia–Pacific region by promoting security cooperation, encouraging peaceful development, responding to contingencies, deterring aggression, and, when necessary, fighting to win. This approach is based on partnership, presence, and military readiness.132 l USINDOPACOM’s area of responsibility (AOR) includes not only the expanses of the Pacific, but also Alaska and portions of the Arctic, South Asia, and the Indian Ocean. Its 36 nations represent more than U.S. Army Pacific. USARPAC is the Army’s component command in the Pacific. Headquartered in Hawaii and with approximately 80,000 soldiers, it supplies Army forces as necessary for various global contingencies and “has sent peacekeeping forces to the Sinai Peninsula, Haiti, East Timor and Bosnia.”135 Among its 12 subordinate commands are U.S. Army Japan, the 500th Military Intelligence Brigade, and U.S. Army Alaska. At the other extreme, the Armed Forces of the Philippines are among the region’s weakest military forces. Having long focused on waging counterinsurgency campaigns while relying on the United States for its external security, the Philippines spent only 1.0 percent of GDP on its military in 2020.127 The most modern ships in the Philippine navy are three former U.S. Hamilton-class Coast Guard cutters. It has also taken delivery of new South Korean–built frigates and is set to buy two more smaller South Korean naval vessels.128 The Philippines also has purchased 12 light attack fighter aircraft from South Korea129 and has been cleared to acquire 12 new American F-16s.130 The armed forces of American allies from outside the region, particularly those of France and the United Kingdom, should also be mentioned. France has overseas bases in New Caledonia and the South Pacific, locally based assets, and 2,900 personnel in the region.131 It also conducts multiple naval deployments each year out of Metropolitan France. The U.K. is likewise very active in the region and, given its unparalleled integration with U.S. forces, can employ its capability directly in pursuit of shared objectives. It has a naval logistics facility in Singapore and Royal Gurkhas stationed in Brunei and has been an integral part of a U.S.-led mission to monitor seaborne evasions. U.S. Pacific Air Force. PACAF is responsible for planning and conducting defensive and offensive air operations in the Asia–Pacific region. It has three numbered air forces under its command: 5th Air Force in Japan; 7th Air Force in Korea; and 11th Air Force, headquartered in Alaska. These air forces field two squadrons of F-15s, two squadrons of F-22s, five squadrons of F-16s, and a single squadron of A-10 ground attack aircraft as well as two squadrons of E-3 early-warning aircraft, tankers, and transports. Other forces that regularly come under PACAF command include B-52, B-1, and B-2 bombers. In 2020, PACAF activated two F-35A squadrons at Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska. It completed the integration of 54 “combat-coded” F-35A aircraft in April 2022, increasing the number of squadrons to four.136 U.S. Pacific Fleet. PACFLT normally controls all U.S. naval forces committed to the Pacific, which usually represents 60 percent of the Navy’s fleet. It is organized into Seventh Fleet, headquartered in Japan, and Third Fleet, The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 177 headquartered in California. Seventh Fleet comprises the forward-deployed element of PACFLT and includes the only American carrier strike group (CTF-70, ported at Yokosuka, Japan) and amphibious group (CTF-76, ported at Sasebo, Japan) that are home-ported abroad. The Third Fleet’s AOR spans the West Coast of the United States to the International Date Line and includes the Alaskan coastline and parts of the Arctic. In recent years, the involvement of the Third Fleet’s five carrier strike groups in the Western Pacific has been eased by the blurring of this boundary between the two fleets’ areas of operation under a concept called “Third Fleet Forward.” Beginning in 2015, the conduct of Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) that challenge excessive maritime claims (a part of the Navy’s mission since 1979) has assumed a higher profile as a result of several well-publicized operations in the South China Sea. Under the Trump Administration, the frequency of these operations increased significantly. l l 178 U.S. Marine Forces Pacific. With its headquarters in Hawaii, MARFORPAC controls elements of the U.S. Marine Corps operating in the Asia–Pacific region. Because of its extensive responsibilities and physical span, MARFORPAC controls two-thirds of Marine Corps forces: the I Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF), centered on the 1st Marine Division, 3rd Marine Air Wing, and 1st Marine Logistics Group, and the III Marine Expeditionary Force, centered on the 3rd Marine Division, 1st Marine Air Wing, and 3rd Marine Logistics Group. The I MEF is headquartered at Camp Pendleton, California, and the III MEF is headquartered on Okinawa, although each has various subordinate elements deployed at any time throughout the Pacific on exercises, to maintain presence, or engaged in other activities. MARFORPAC is responsible for supporting three different commands: It is the U.S. Marine Corps component of USINDOPACOM, provides the Fleet Marine Forces to PACFLT, and provides Marine forces for U.S. Forces Korea (USFK). U.S. Special Operations Command Pacific. SOCPAC has operational control of various special operations forces, including Navy SEALs; Naval Special Warfare units; Army Special Forces (Green Berets); and Special Operations Aviation units in the Pacific region, including elements in Japan and South Korea. It supports the Pacific Command’s Theater Security Cooperation Program as well as other plans and contingency responses. SOCPAC forces also support various operations in the region other than warfighting, such as counterdrug operations, counterterrorism training, humanitarian assistance, and demining activities. l U.S. Forces Korea and U.S. Eighth Army. Because of the unique situation on the Korean Peninsula, two subcomponents of USINDOPACOM—U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) and U.S. Eighth Army—are based in Korea. USFK, a joint headquarters led by a four-star U.S. general, is in charge of the various U.S. military elements on the peninsula. U.S. Eighth Army operates in conjunction with USFK as well as with the United Nations presence in the form of United Nations Command. Other forces, including space capabilities, cyber capabilities, air and sealift assets, and additional combat forces, may be made available to USINDOPACOM depending on requirements and availability. Key Infrastructure That Enables Expeditionary Warfighting Capabilities Any planning for operations in the Pacific will be dominated by the “tyranny of distance.” Because of the extensive distances that must be traversed in order to deploy forces, even Air Force units will take one or more days to deploy, and ships measure steaming time in weeks. For instance, a ship sailing at 20 knots requires nearly five days to get from San Diego to Hawaii. From there, it takes seven more days to get to Guam; seven days to Yokosuka, Japan; and eight days to Okinawa—if ships encounter no interference along the journey.137 China’s growing anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities, ranging from an expanding fleet of modern submarines to anti-ship ballistic and cruise missiles, increase the operational risk for deployment of U.S. forces in the event of conflict. China’s capabilities not only jeopardize American combat forces 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 179 that would flow into the theater for initial combat, attractive potential target in the event of conflict. but also would continue to threaten the logistical The increasing reach of Chinese and North Korean support needed to sustain American combat power ballistic missiles reflects this growing vulnerability. during the subsequent days, weeks, and months. Guam and Saipan. The U.S. military has nonAmerican basing structure in the Indo-Pacific combatant maritime prepositioning ships (MPS), region, including access to key allied facilities, is which contain large amounts of military equipment therefore both necessary and increasingly at risk. and supplies, in strategic locations from which they can reach areas of conflict relatively quickly as asAmerican Facilities sociated U.S. Army or Marine Corps units located Hawaii. Much as it was in the 20th century, Ha- elsewhere arrive in the areas. U.S. Navy units on waii remains the linchpin of America’s ability to sup- Guam and in Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northport its position in the Western Pacific. If the United ern Marianas, support prepositioning ships that States cannot preserve its facilities in Hawaii, both can supply Army or Marine Corps units deployed combat power and sustainability become moot. The for contingency operations in Asia. United States maintains air and naval bases, communications infrastructure, and logistical support on Allied and Other Friendly Facilities Oahu and elsewhere in the Hawaiian Islands. Hawaii For the United States, access to bases in Asia has is also a key site for undersea cables that carry much long been a vital part of its ability to support military of the world’s communications and data, as well as operations in the region. Even with the extensive for satellite ground stations. aerial refueling and replenishment skills of the U.S. Guam. The American territory of Guam is located Air Force and U.S. Navy, it is still essential that the 4,600 miles farther west. Obtained from Spain as a United States retain access to resupply and replenresult of the Spanish–American War, Guam became ishment facilities, at least in peacetime. The ability a key coaling station for U.S. Navy ships. It was seized of those facilities to survive and function will directby Japan in World War II, was liberated by U.S. forces ly influence the course of any conflict in the Westin 1944, and after the war became an unincorporat- ern Pacific region. Moreover, a variety of support ed, organized territory of the United States. Key U.S. functions, including communications, intelligence, military facilities on Guam include U.S. Naval Base and space support, cannot be accomplished without Guam, which houses several attack submarines and facilities in the region. possibly a new aircraft carrier berth, and Andersen Today, maintaining maritime domain awareness Air Force Base, one of a handful of facilities that can or space situational awareness would be extraorhouse B-2 bombers. U.S. task forces can stage out of dinarily difficult without access to facilities in the Apra Harbor, drawing weapons from the Ordnance Asia–Pacific region. The American alliance network Annex in the island’s South Central Highlands. The is therefore a matter both of political partnership Marine Corps is working to expand a major facility, and of access to key facilities on allied soil. Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz, activated on OctoJapan. In Japan, the United States has access ber 1, 2020.138 Upon completion in 2025, the base will to more than 100 different facilities, including host 5,000 Marines comprising various aviation and communications stations, military and dependent ground combat, combat support, logistics, and head- housing, fuel and ammunition depots, and weapons quarters units.139 There is also a communications and and training ranges in addition to such major basdata relay facility on the island. es as the air bases at Misawa, Yokota, and Kadena Guam’s facilities have improved steadily over and naval facilities at Yokosuka, Atsugi, and Sasebo. the past 20 years. B-2 bombers, for example, began The naval facilities support the USS Ronald Reagan to operate from Andersen Air Force Base in March carrier strike group (CSG), which is home-ported in 2005.140 These improvements have been accelerated Yokosuka, and a Navy-Marine Expeditionary Strike and expanded even as China’s A2/AD capabilities Group (ESG) centered on the USS America, homehave raised doubts about the ability of the U.S. to ported at Sasebo. The skilled workforce at places like sustain operations in the Asian littoral. The con- Yokosuka is needed to maintain American forces and centration of air and naval assets as well as logis- repair equipment in time of conflict. Replacing them tical infrastructure, however, makes the island an would take years if not decades. This combination of facilities and workforce, in addition to physical location and political support, makes Japan an essential part of any American military response to contingencies in the Western Pacific. Japanese financial support for the American presence also makes these facilities some of the most cost-effective in the world. The status of one critical U.S. base has been a matter of public debate in Japan for many years. The U.S. Marine Corps’ Third Marine Expeditionary Force, based on Okinawa, is the U.S. rapid reaction force in the Pacific. The Marine Air-Ground Task Force, comprised of air, ground, and logistics elements, enables quick and effective response to crises or humanitarian disasters. To improve the political sustainability of U.S. forces by reducing the impact on the local population in that densely populated area, the Marines are relocating some units to Guam and less-populated areas of Okinawa. The latter includes moving a helicopter unit from Futenma to a new facility in a more remote location in northeastern Okinawa. Because of local resistance, construction of the Futenma Replacement Facility at Camp Schwab will not be complete until at least 2025, but the U.S. and Japanese governments have affirmed their support for the project. South Korea. The United States also maintains an array of facilities in South Korea. The Army’s footprint in South Korea is larger than its footprint in Japan because the United States and South Korea remain focused on deterring North Korean aggression and preparing for any possible North Korean contingencies. The Army maintains four major facilities (which in turn control a number of smaller sites) at Daegu, Yongsan in Seoul, and Camps Red Cloud/Casey and Humphreys. These facilities support the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division, which is based in South Korea. Other key facilities include air bases at Osan and Kunsan and a naval facility at Chinhae near Pusan. The Philippines. In 1992, the United States ended a nearly century-long presence in the Philippines when it withdrew from its base in Subic Bay as the base’s lease ended. The eruption of Mount Pinatubo had already forced the closure of Clark Air Base; the costs of repairing the facility were deemed too high to be worthwhile. In 2014, however, spurred by China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea, including against Philippine claims such as Mischief Reef (seized in 1995) and Scarborough Shoal 180 (2012), the U.S. and the Philippines negotiated the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, which allowed for the rotation of American forces through Philippine military bases. In 2016, the two sides agreed on an initial list of five bases to be used in the Philippines. Geographically distributed across the country, they are Antonio Bautista Air Base in Palawaan, closest to the Spratlys; Basa Air Base, located on the main Philippine island of Luzon and closest to the hotly contested Scarborough Shoal; Fort Magsaysay, also on Luzon and the only facility on the list that is not an air base; Lumbia Air Base in Mindanao, where Manila remains engaged in low-intensity combat with Islamist insurgents; and Mactan-Benito Ebuen Air Base in the central Philippines.141 In 2018, construction was completed on a humanitarian assistance and disaster relief warehouse located at Basa Air Base.142 American F-16s based in South Korea deployed there for a 12-day exercise with Philippine fighter jets in 2019143 and exercised there again in 2020.144 With the resolution of disputes over the status of America’s Visiting Forces Agreement with the Philippines, it is expected that building out of the other EDCA sites will begin as well. It remains unclear precisely which additional forces would be rotated through the Philippines as a part of this agreement, which in turn affects the kinds of facilities that would be most needed. The base upgrades and deployments pursuant to the EDCA are part of a broader expansion of U.S.–Philippine defense ties begun under the Aquino government and continued under President Duterte with some adjustments. Singapore. The United States does not have bases in Singapore, but it is allowed access to several key facilities that provide essential support for American forward presence. Since the closure of its facilities at Subic Bay, the United States has been allowed to operate the principal logistics command for the Seventh Fleet out of the Port of Singapore Authority’s Sembawang Terminal. The U.S. Navy also has access to Changi Naval Base, one of the few docks in the world that can handle a 100,000-ton American aircraft carrier. A small U.S. Air Force contingent operates out of Paya Lebar Air Base to support U.S. Air Force combat units visiting Singapore and Southeast Asia, and Singapore hosts Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) and rotating P-8 aircraft.145 Australia. The most prominent element of the U.S. presence in Australia is the deployment of U.S. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Specifically, “MPF ships deliver a forward presence and rapid crisis response capability by pre-positioning equipment and supplies to various locations at sea.”149 Several elements of the U.S. global space surveillance and communications infrastructure, as well as basing facilities for the B-2 bomber, are also located on the island. Conclusion The Asian strategic environment is extremely expansive. It includes half the globe and is characterized by a variety of political relationships among states that possess wildly varying capabilities. The region includes long-standing American allies with relationships dating back to the beginning of the Cold War as well as recently established states and some long-standing adversaries such as North Korea. American conceptions of the region must therefore recognize the physical limitations imposed by the tyranny of distance. Moving forces within the region (never mind to it) will take time and require extensive strategic lift assets as well as sufficient infrastructure (such as sea and aerial ports of debarkation that can handle American strategic lift assets) and political support. At the same time, the complicated nature of intra-Asian relations, especially unresolved historical and territorial issues, means that the United States, unlike Europe, cannot necessarily count on support from all of its regional allies in responding to any given contingency. Scoring the Asia Operating Environment As with the operating environments of Europe 2. Unfavorable. A challenging operating enviand the Middle East, we assessed the characterisronment for military operations is marked by tics of Asia as they could be expected to facilitate or inadequate infrastructure, weak alliances, and inhibit America’s ability to conduct military operrecurring political instability. The U.S. military ations to defend its vital national interests against is inadequately placed in the region. threats. Our assessment of the operating environment utilized a five-point scale that ranges from 3. Moderate. A neutral to moderately favorable “very poor” to “excellent” conditions and covers four operating environment is characterized by aderegional characteristics of greatest relevance to the quate infrastructure, a moderate alliance strucconduct of military operations: ture, and acceptable levels of regional political stability. The U.S. military is adequately placed. 1. Very Poor. Significant hurdles exist for military operations. Physical infrastructure is insuffi4. Favorable. A favorable operating environment cient or nonexistent, and the region is politicalincludes good infrastructure, strong alliances, ly unstable. The U.S. military is poorly placed or and a stable political environment. The U.S. absent, and alliances are nonexistent or diffuse. military is well placed for future operations. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 181 Marines to Darwin in northern Australia. In keeping with Australian sensitivities about permanent American bases on Australian soil, however, the Marines do not maintain a permanent presence in the country.146 Similarly, the United States jointly staffs the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap and the Joint Geological and Geophysical Research Station at Alice Springs and has access to the Harold E. Holt Naval Communication Station, including its space surveillance radar system, in the western part of the country.147 Finally, the United States is granted access to a number of facilities in Asian states on a contingency or crisis basis. Thus, U.S. Air Force units transited Thailand’s U-Tapao Air Base and Sattahip Naval Base during the first Gulf War and during the Iraq War, but they do not maintain a permanent presence there. Additionally, the U.S. Navy conducts hundreds of port calls throughout the region. Diego Garcia. The American facilities on the British territory of Diego Garcia are vital to U.S. operations in the Indian Ocean and Afghanistan and provide essential support for operations in the Middle East and East Asia. The island is home to the Military Sealift Command’s Maritime Prepositioning Squadron-2 (MPSRON-2), which works with Maritime Prepositioning Squadron-3 (MPSRON-3) “to deliver a strategic power-projection capability for the Marine Corps, Army and Air Force, known as the Maritime Prepositioning Force (MPF).”148 5. Excellent. An extremely favorable operating environment includes well-established and well-maintained infrastructure, strong and capable allies, and a stable political environment. The U.S. military is exceptionally well placed to defend U.S. interests. presumably, achieve successes in critical “first battles” more quickly. Being routinely present also helps the United States to maintain familiarity with a region’s characteristics and the various actors that might act to assist or thwart U.S. actions. With this in mind, we assessed whether or not the U.S. military was well positioned in the region. Again, indicators included bases, troop presence, prepositioned equipment, and recent examples of military operations (including training and humanitarian) launched from the region. The key regional characteristics consist of: a. Alliances. Alliances are important for interoperability and collective defense, as allies would be more likely to lend support to U.S. military operations. Indicators that provide insight into the strength or health of an alliance include whether the U.S. trains regularly with countries in the region, has good interoperability with the forces of an ally, and shares intelligence with nations in the region. b. Political Stability. Political stability brings predictability for military planners when considering such things as transit, basing, and overflight rights for U.S. military operations. The overall degree of political stability indicates whether U.S. military actions would be hindered or enabled and reflects, for example, whether transfers of power in the region are generally peaceful and whether there have been any recent instances of political instability in the region. c. U.S. Military Positioning. Having military forces based or equipment and supplies staged in a region greatly facilitates the ability of the United States to respond to crises and, d. Infrastructure. Modern, reliable, and suitable infrastructure is essential to military operations. Airfields, ports, rail lines, canals, and paved roads enable the U.S. to stage, launch operations from, and logistically sustain combat operations. We combined expert knowledge of regions with publicly available information on critical infrastructure to arrive at our overall assessment of this metric.150 For Asia, we arrived at these average scores (rounded to the nearest whole number): l Alliances: 4—Favorable l Political Stability: 3—Moderate l U.S. Military Positioning: 4—Favorable l Infrastructure: 4—Favorable Aggregating to a regional score of: Favorable Operating Environment: Asia VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE Alliances Political Stability 182 FAVORABLE % % U.S. Military Posture % Infrastructure % OVERALL % 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength EXCELLENT Endnotes 1. U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau, “Foreign Trade: Top Trading Partners—December 2021,” https://www.census.gov/foreigntrade/statistics/highlights/top/top2112yr.html (accessed May 13, 2022). 2. “Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.” Constitution of Japan, Article 9, promulgated November 3, 1946, came into effect May 3, 1947, http://japan.kantei.go.jp/constitution_and_ government_of_japan/constitution_e.html (accessed May 13, 2022). 3. U.S. Forces, Japan, “About USFJ: Guidance from the Commander, U.S. Forces Japan,” https://www.usfj.mil/About-USFJ/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 4. Emma Chanlett-Avery, Mark E. Manyin, Brock R. Williams, Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs, and Caitlin Campbell, “U.S.–Japan Relations,” Congressional Research Service In Focus No. 10199, updated March 30, 2022, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10199.pdf (accessed May 13, 2022). 5. Bruce Klingner, James Jay Carafano, and Walter Lohman, “Don’t Break Alliances over Money,” The National Interest, Korea Watch Blog, November 22, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/korea-watch/don’t-break-alliances-over-money-98967 (accessed May 13, 2022). 6. Bruce Klingner, Jung Pak, and Sue Mi Terry, “Opinion: Trump Shakedowns Are Threatening Two Key U.S. Alliances in Asia,” Los Angeles Times, December 16, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2019-12-16/how-trump-is-threatening-alliances-in-asia (accessed June 20, 2021). 7. Press release, “Joint Statement of the U.S.–Japan Security Consultative Committee 2+2,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 6, 2022, https:// thepressreleaseengine.com/Joint+Statement+of+the+U+S+-Japan+Security+Consultative+Committee+2+2+-id210220-1068297 (accessed May 13, 2022). 8. Yukio Tajima, Rintaro Tobita, and Junnosuke Kobara, “Japan PM Hopefuls Kono, Kishida Join Call to Hike Defense Budget,” Nikkei Asia, September 14, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Japan-election/Japan-PM-hopefuls-Kono-Kishida-join-call-to-hike-defense-budget (accessed May 13, 2022). 9. Bruce Klingner and Riley Walters, “The U.S. Must Limit Damage from the Japan–South Korea Trade Dispute,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3429, August 7, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/the-us-must-limit-damage-the-japan-south-korea-trade-dispute. 10. The December 2015 “Comfort Women Agreement” (referring to the women forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II) and the 2016 GSOMIA. 11. Kyodo News, “South Korea’s Next Leader Yoon Vows Future-Oriented Ties with Japan,” March 10, 2022, https://english.kyodonews.net/ news/2022/03/3af347bb3857-urgent-s-koreas-yoon-vows-to-build-future-oriented-relations-with-japan.html (accessed May 13, 2022). 13. NPR, “President Trump’s Press Conference on North Korea Summit, Annotated,” June 12, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/06/12/619192513/ president-trumps-press-conference-on-north-korea-summit-annotated (accessed May 13, 2022). 14. Josh Smith and Hyonhee Shin, “U.S., S.Korea Seen Resuming Major Military Drills as N.Korea Tensions Rise,” Reuters, March 31, 2022, https:// wtvbam.com/2022/03/31/u-s-s-korea-seen-resuming-major-military-drills-as-n-korea-tensions-rise/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 15. Klingner, Carafano, and Lohman, “Don’t Break Alliances over Money.” 16. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of Inspector General; U.S. Department of State, Office of Inspector General; and U.S. Agency for International Development, Office of Inspector General, Overseas Contingency Operations: Operation Inherent Resolve, Operation Pacific Eagle–Philippines, Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, October 1, 2017–December 31, 2017, pp. 99–100, https://media.defense.gov/2018/ Jun/18/2001932643/-1/-1/1/FY2018_LIG_OCO_OIR_Q1_12222017_2.PDF (accessed May 13, 2022). 17. Sebastian Strangio, “Philippines, US Kick Off Large-Scale Balikatan Military Exercise,” The Diplomat, March 29, 2022, https://thediplomat. com/2022/03/philippines-us-kick-off-large-scale-balikatan-military-exercise/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 18. Press release, “U.S. and Philippine Forces Successfully Conclude 37th Balikatan,” U.S. Embassy in the Philippines, April 8, 2022, https:// ph.usembassy.gov/u-s-and-philippine-forces-successfully-conclude-37th-balikatan/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 19. Admiral John C. Aquilino, U.S. Navy, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, statement on “U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Posture” before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, March 10, 2022, pp. 21–22, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/INDOPACOM%20 Statement%20(ADM%20Aquilino)%20_SASC2.PDF (accessed May 13, 2022). 20. Walter Lohman, “Scarborough Shoal and Safeguarding American Interests,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 3603, May 14, 2012, p. 2, http:// www.heritage.org/research/reports/2012/05/south-china-sea-dispute-between-china-and-the-philippines-safeguarding-americas-interests. 21. Press release, “Secretary Blinken’s Call with Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs Locsin,” U.S. Department of State, April 8, 2021, https://www. state.gov/secretary-blinkens-call-with-philippine-secretary-of-foreign-affairs-locsin-2/ (accessed May 13, 2022), and press release, “Secretary Blinken’s Call with Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs Locsin,” U.S. Department of State, January 27, 2021, https://www.state.gov/secretaryblinkens-call-with-philippine-secretary-of-foreign-affairs-locsin/ (accessed May 13, 2022). See also former Secretary of State Michael Pompeo’s remarks in transcript, “Remarks with Philippine Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin, Jr. at a Press Availability,” Manila, Philippines, March 1, 2019, https://2017-2021.state.gov/remarks-with-philippine-foreign-secretary-teodoro-locsin-jr/index.html (accessed May 13, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 183 12. Bruce Klingner, “Enhance South Korean Military Capabilities Before OPCON Transfer,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3452, December 2, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/enhance-south-korean-military-capabilities-opcon-transfer. 22. Press release, “Readout of Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III’s Meeting With Philippine Secretary of National Defense Delfin Lorenzana,” U.S. Department of Defense, September 10, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2771441/readout-of-secretary-ofdefense-lloyd-j-austin-iiis-meeting-with-philippine-sec/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 23. Named for Thai Foreign Minister Thanat Khoman and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk. 24. “2012 Joint Vision Statement for the Thai–U.S. Defense Alliance,” Bangkok, Thailand, November 15, 2012, in Bangkok Post, November 16, 2012, https://www.bangkokpost.com/world/321551/text-of-thailand-us-joint-vision-statement (accessed May 13, 2022). 25. 1st Lt. Timothy Hayes, “Cobra Gold 20: Opening Ceremony,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, February 25, 2020, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/ News/News-Article-View/Article/2094057/cobra-gold-20-opening-ceremony/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 26. Reuters, “Thai, U.S. Troops Prepare for Scaled Down ‘Cobra Gold’ Exercises,” February 18, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/thaius-troops-prepare-scaled-down-cobra-gold-exercises-2022-02-18/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 27. Wassana Nanuam, “Cobra Gold Lite Kicks off in Thailand,” Bangkok Post, February 23, 2022, https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/ general/2268331/cobra-gold-lite-kicks-off-in-thailand (accessed May 13, 2022). 28. Reuters, “Thai, U.S. Troops Prepare for Scaled Down ‘Cobra Gold’ Exercises.” 29. RFA and BenarNews Staff, “Thai Plan to Acquire F-35 Fighter Jets Poses Dilemma for Washington,” Radio Free Asia, February 2, 2022, https:// www.rfa.org/english/news/china/thailand-f35-02162022155156.html (accessed May 31, 2022). 30. Phuong Nguyen and Brittany Billingsley, “China’s Growing Military-to-Military Engagement with Thailand & Myanmar,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Asia Program, cogitASIA blog, September 12, 2013, http://cogitasia.com/chinas-growing-military-to-militaryengagement-with-thailand-and-myanmar/ (accessed May 13, 2022); Patpicha Tanakasempipat and Jutarat Skulpichetrat, “China, Thailand Joint Air Force Exercise Highlights Warming Ties,” Reuters, November 14, 2015, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-china-thailand-militaryidUKKBN0TD0CB20151124 (accessed May 13, 2022); and Ian Storey, “Thailand’s Military Relations with China; Moving from Strength to Strength,” Yusof Ishak Institute Perspective, Issue: 2019, No. 43, May 27, 2019, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2019_43.pdf (accessed May 13, 2022). 31. Zachary Abuza, “America Should Be Realistic About Its Alliance with Thailand,” War on the Rocks, January 2, 2020, https://warontherocks. com/2020/01/america-should-be-realistic-about-its-alliance-with-thailand/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 32. Ibid.; Mike Yeo, “Thailand to Buy More Chinese Tanks, Reportedly for $58M,” Defense News, April 4, 2017, http://www.defensenews.com/articles/ thailand-to-buy-more-chinese-tanks-reportedly-for-58m (accessed May 13, 2022); and Reuters, “Thailand in $67-Million Deal to Buy Armored Personnel Carriers from China,” June 14, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-china-defence-idUSKBN1950IH (accessed May 13, 2022). 33. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “SIPRI Arms Transfers Database: Trade Registers: Transfers of Major Weapons: Deals with Deliveries or Orders Made for 2006 to 2021,” https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers (accessed May 13, 2022). Data for Thailand are a product of user query whereby the country and years of interest are selected. Query results generate a table that shows countries supplying arms to Thailand. The top five include Sweden, China, Ukraine, South Korea, and the U.S. in descending order. 34. Masayuki Yuda, “Thailand Shelves Chinese Submarine Deal After Public Backlash,” Nikkei Asia, August 31, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/ Turbulent-Thailand/Thailand-shelves-Chinese-submarine-deal-after-public-backlash (accessed May 13, 2022). 35. Zsombor Peter, “Thai–China Submarine Deal Runs Aground on EU Arms Embargo,” Voice of America, March 31, 2022, https://www.voanews. com/a/thai-china-submarine-deal-runs-aground-on-eu-arms-embargo-/6509026.html (accessed May 13, 2022). 36. Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Countries, Economies and Regions: United States of America: AUSMIN— Australia–United States Ministerial Consultations,” https://dfat.gov.au/geo/united-states-of-america/ausmin/Pages/ausmin-australia-unitedstates-ministerial-consultations.aspx (accessed May 13, 2022). 37. Kim Beazley, “Pine Gap at 50: The Paradox of a Joint Facility,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, The Strategist, August 30, 2017, https://www. aspistrategist.org.au/pine-gap-50-paradox-joint-facility/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 38. Stephen Smith, Minister of Defence and Deputy Leader of the House, Ministerial Statement on “Full Knowledge and Concurrence,” Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, June 26, 2013, pp. 7071–7075, http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/ genpdf/chamber/hansardr/4d60a662-a538-4e48-b2d8-9a97b8276c77/0016/hansard_frag.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf (accessed May 13, 2022). 39. Seth Robson, “US Marines Begin Arriving in Australia for Another Six-Month Training Mission,” Stars and Stripes, March 14, 2022, https://www. stripes.com/branches/marine_corps/2022-03-14/us-marine-corps-darwin-australia-rotation-covid-19-coronavirus-5339176.html#:~:text=A%20 contingent%20of%20up%20to,Australian%20Defence%20Department%20announced%20Monday (accessed May 13, 2022). 40. Capt. Joseph DiPietro, “Marine Rotational Force–Darwin 22 Arrives in Darwin,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, March 17, 2022, https://www.pacom. mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2970258/marine-rotational-force-darwin-22-arrives-in-darwin/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 41. Australian Government, Department of Defence, “United States Force Posture Initiatives: Enhanced Air Cooperation,” https://defence.gov.au/ Initiatives/USFPI/EAC.asp (accessed May 13, 2022). 184 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 42. John Coyne, “Defence Needs a Clear Plan for Investment in Northern Australia,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, The Strategist, March 21, 2022, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/defence-needs-a-clear-plan-for-investment-in-northern-australia/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 43. Australian Government, Department of Defence, “United States Force Posture Initiatives: USFPI Infrastructure,” https://defence.gov.au/Initiatives/ USFPI/Infrastructure/Default.asp (accessed May 13, 2022). 44. “Fact Sheet: Implementation of the Australia–United Kingdom–United States Partnership (AUKUS),” The White House, April 5, 2022, https:// www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/05/fact-sheet-implementation-of-the-australia-united-kingdom-unitedstates-partnership-aukus/ (accessed May 13, 2022). See also press release, “Joint Statement on Australia–U.S. Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) 2021,” U.S. Department of State, September 16, 2021, https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-australia-u-s-ministerial-consultationsausmin-2021/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 45. “Fact Sheet: Implementation of the Australia–United Kingdom–United States Partnership (AUKUS),” 46. U.S. Army Pacific Public Affairs, “Exercise Talisman Saber 2017 Highlights Enduring US, Australia Alliance,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, June 29, 2017, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1233790/exercise-talisman-saber-2017-highlights-enduring-us-australiaalliance/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 47. Fact Sheet, “U.S. Security Cooperation with Singapore,” U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, April 20, 2021, https://www. state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-singapore/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 48. Valerie Insinna, “Singapore Gets the Green Light to Buy F-35s,” Defense News, January 9, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/air/2020/01/09/ singapore-gets-the-green-light-to-buy-f-35s/ (accessed May 13, 2022), and Mike Yeo, “Singapore Moves to Buy Four F-35s, Possibly Eight More Afterward,” Defense News, March 1, 2019, https://www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/avalon/2019/03/01/singapore-moves-to-buy-fourf-35s-possibly-eight-more-afterward/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 49. Mike Yeo, “US Approves Location for Singaporean F-16, F-35 Training,” Defense News, June 4, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/trainingsim/2021/06/04/us-approves-location-for-singaporean-f-16-f-35-training/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 50. Mike Yeo, “Singapore to Launch Fighter Jet Training Detachment on Guam,” Defense News, December 9, 2019, https://www.defensenews.com/ smr/reagan-defense-forum/2019/12/09/singapore-to-launch-fighter-jet-training-detachment-on-guam/ (accessed May 13, 2022), and Linette Lai, “Two US Airbases Shortlisted to Host New RSAF F-35B Aircraft,” The Straits Times, June 4, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/ two-us-air-bases-shortlisted-to-host-new-rsaf-f-35b-aircraft (accessed May 13, 2022). 52. News release, “U.S., New Zealand Announce Expanded Defense Cooperation,” U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, October 28, 2013, https://www.dsca.mil/news-media/news-archive/us-new-zealand-announce-expanded-defense-cooperation (accessed May 13, 2022), and David B. Larter, “In Port Visit, New Zealand and U.S. Seek to Bolster Military Ties,” Navy Times, July 22, 2016, http:// www.navytimes.com/story/military/2016/07/22/port-visit-new-zealand-and-us-seek-bolster-military-ties/87450022/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 53. Associated Press, “US Warship to Visit New Zealand as USS Sampson’s Arrival Ends Stalemate on Nuclear Vessels,” ABC [Australian Broadcasting Corporation] News, October 18, 2016, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-10-18/new-zealand-to-end-stalemate-on-us-warships/7943252 (accessed May 13, 2022). 54. Seth Robson, “US Navy Destroyer Makes a Rare Port Call in New Zealand,” Stars and Stripes, November 26, 2021, https://www.stripes.com/ branches/navy/2021-11-25/us-navy-port-call-wellington-new-zealand-uss-howard-3755849.html (accessed May 13, 2022). 55. See J. Vitor Tossini, “The Five Eyes—The Intelligence Alliance of the Anglosphere,” UK Defence Journal, April 14, 2020, https://ukdefencejournal. org.uk/the-five-eyes-the-intelligence-alliance-of-the-anglosphere/ (accessed May 16, 2022), and Office of the Director of National Intelligence, National Counterintelligence and Security Center, “Five Eyes Intelligence Oversight and Review Council,” https://www.dni.gov/index.php/ncschow-we-work/217-about/organization/icig-pages/2660-icig-fiorc (accessed May 16, 2022). 56. Taiwan Relations Act, Public Law 96-8, 96th Cong., approved April 10, 1979, Section 2, https://www.ait.org.tw/our-relationship/policy-history/ key-u-s-foreign-policy-documents-region/taiwan-relations-act/ (accessed May 14, 2022). Section 18 specifies that “This Act shall be effective as of January 1, 1979.” 57. Ibid., Section 3. 58. Ibid., Section 2. 59. Ibid., Section 3. 60. See hearing, U.S. Policy Toward China and Taiwan, Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess., August 17, 1982, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZsPcyAEACAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed May 16, 2022), and hearing, China–Taiwan: United States Policy, Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess., August 18, 1982, https://books.google.com/books?id=px3hl0TuzwsC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_ summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed May 16, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 185 51. See “Text of the Wellington Declaration,” November 5, 2010, http://usnzcouncil.org/us-nz-issues/wellington-declaration/ (accessed May 13, 2022), and “Text of the Washington Declaration on Defense Cooperation Between the Department of Defense of the United States of America and the Ministry of Defense of New Zealand and the New Zealand Defense Force,” June 19, 2012, http://usnzcouncil.org/us-nz-issues/washingtondeclaration/ (accessed May 13, 2022). 61. Shirley A. Kan, “China/Taiwan: Evolution of the ‘One China’ Policy—Key Statements from Washington, Beijing, and Taipei,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL30341, October 10, 2014, pp. 43–44, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/ RL30341.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). Emphasis in original. 62. Erin Hale, “US Nearly Doubled Military Personnel Stationed in Taiwan This Year,” Voice of America, December 2, 2021, https://www.voanews. com/a/pentagon-us-nearly-doubled-military-personnel-stationed-in-taiwan-this-year-/6337695.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 63. Jack Detsch, “The U.S. Is Getting Taiwan Ready to Fight on the Beaches,” Foreign Policy, November 8, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/11/08/ us-taiwan-military-presence-china-biden-porcupine/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 64. Hale, “US Nearly Doubled Military Personnel Stationed in Taiwan This Year.” 65. News release, “United States–Vietnam Joint Vision Statement,” The White House, July 7, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-pressoffice/2015/07/07/united-states-%E2%80%93-vietnam-joint-vision-statement (accessed May 16, 2022). 66. News release, “Joint Statement: Between the United States of America and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,” U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Vietnam, November 13, 2017, https://vn.usembassy.gov/20171112-joint-statement-united-states-america-socialist-republic-viet-nam/ (accessed May 16, 2022). 67. Aquilino, statement on “U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Posture,” March 10, 2022, p. 27. 68. Ridzwan Rahmat, “Vietnam’s Request for Third ex-USCG Cutter Receives Support of Biden Administration,” Janes, August 26, 2021, https://www. janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/vietnams-request-for-third-ex-uscg-cutter-receives-support-of-biden-administration (accessed May 14, 2022). 69. Fact Sheet, “U.S. Security Cooperation with Vietnam,” U.S. Department of State, August 16, 2018, https://2017-2021.state.gov/u-s-securitycooperation-with-vietnam/index.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 70. Mike Yeo, “Asia-Pacific Militaries Bet on Unmanned Systems to Meet Regional Challenges,” Defense News, November 30, 2020, https://www. defensenews.com/unmanned/2020/11/30/asia-pacific-militaries-bet-on-unmanned-systems-to-meet-regional-challenges/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 71. Jon Grevatt, “Vietnam to Procure T-6 to Boost Pilot Training,” Janes, June 7, 2021, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/vietnam-toprocure-t-6-to-boost-pilot-training (accessed May 14, 2022). 72. “Joint Statement: Between the United States of America and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,” The White House, May 23, 2016, https:// obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/05/23/joint-statement-between-united-states-america-and-socialist-republic (accessed May 14, 2022). 73. Wyatt Olson, “Winnowed in Scope by Coronavirus, a Smaller RIMPAC Maritime Exercise Begins Monday,” Stars and Stripes, August 14, 2020, https://www.stripes.com/news/pacific/winnowed-in-scope-by-coronavirus-a-smaller-rimpac-maritime-exercise-begins-monday-1.641263 (accessed May 14, 2022). 74. Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, Ministry of National Defence, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, completed and registered October 2019, http://www.mod.gov.vn/wps/wcm/connect/08963129-c9cf-4c86-9b5c-81a9e2b14455/2019VietnamNationalDefence. pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=08963129-c9cf-4c86-9b5c-81a9e2b14455 (accessed May 14, 2022). 75. [Name redacted], “Malaysia: Background and U.S. Relations,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. R43505, May 18, 2017, pp. 9–10, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20170518_R43505_025187722d007dc55f7f86a9a6ea62e4985d07b3. pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). Two earlier versions of this report dated May 23, 2014, and November 19, 2015, list Ian E. Rinehart, Analyst in Asian Affairs, as the author. 76. Bernama [Malaysian National News Agency], “US Committed to Stronger Defence Ties with Malaysia,” Malay Mail, July 10, 2020, https://www. malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/07/10/us-committed-to-stronger-defence-ties-with-malaysia/1883290 (accessed May 14, 2022). 77. U.S. Embassy in Malaysia, “Office of Defense Cooperation: Foreign Military Sales,” https://my.usembassy.gov/embassy/government-agencies/ office-of-defense-cooperation/ (accessed May 14, 2022), and “Malaysian F/A-18D Hornet Fleet to Undergo Depot Maintenance and Upgrade in Australia,” Asia Pacific Defense Journal, February 19, 2020, https://www.asiapacificdefensejournal.com/2020/02/malaysian-fa-18d-hornet-fleetto.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 78. Mike Yeo, “Malaysia Keen on Buying Kuwait’s Hornet Fighter Jets,” Defense News, December 23, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/ asia-pacific/2021/12/23/malaysia-keen-on-buying-kuwaits-hornet-fighter-jets/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 79. News release, “Joint Statement Between the Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Indonesia and the Department of Defense of the United States of America,” U.S. Department of Defense, May 31, 2019, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/1863375/jointstatement-between-the-ministry-of-defense-of-the-republic-of-indonesia-an/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 80. U.S. Department of Defense, The Department of Defense Indo-Pacific Strategy Report: Preparedness, Partnerships and Promoting a Networked Region, June 1, 2019, p. 37, https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jul/01/2002152311/-1/-1/1/DEPARTMENT-OF-DEFENSE-INDO-PACIFIC-STRATEGYREPORT-2019.PDF (accessed May 14, 2022). 81. BenarNews, “US, Indonesia Building Maritime Training Base on Batan,” Radio Free Asia, June 28, 2021, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/ base-06282021182525.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 186 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 82. Remarks to the Press, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi Before Their Meeting,” U.S. Department of State, August 3, 2021, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-and-indonesian-foreign-minister-retno-marsudi-before-their-meeting/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 83. Koya Jibiki, “US and Indonesia to Hold Largest Island Defense Drills,” Nikkei Asia, July 30, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Internationalrelations/Indo-Pacific/US-and-Indonesia-to-hold-largest-island-defense-drills (accessed May 14, 2022). 84. Associated Press, “US Approves Major $14 Billion Arms Sale to Indonesia,” Voice of America, February 10, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/usapproves-major-14-billion-arms-sale-to-indonesia-/6436765.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 85. Fact Sheet, “U.S. Security Cooperation with Indonesia,” U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, March 23, 2021, https://www. state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-indonesia/ (accessed May 18, 2022). 86. U.S. Department of Defense, Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan, December 2016, p. 33, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/ Documents/pubs/Afghanistan-1225-Report-December-2016.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 87. “Remarks by President Biden on the Way Forward in Afghanistan,” The White House, April 14, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/ speeches-remarks/2021/04/14/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-way-forward-in-afghanistan/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 88. Natasha Turak and Amanda Macias, “Ousted Afghan President Ashraf Ghani Resurfaces in UAE After Fleeing Kabul, Emirati Government Says,” CNBC, August 18, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/18/afghan-president-ashraf-ghani-is-in-uae-after-fleeing-afghanistan.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 89. Sandi Sidhu, Nick Paton Walsh, Tim Lister, Oren Liebermann, Laura Smith-Spark, and Saskya Vandoorne, “Ten Family Members, Including Children, Dead After US Strike in Kabul,” CNN, updated August 30, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/08/29/asia/afghanistan-kabul-evacuationintl/index.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 90. Yaroslav Trofimov, “Taliban Unveil New Afghan Government,” The Wall Street Journal, updated September 7, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/ taliban-crack-down-on-protest-led-by-women-in-kabul-11631014019 (accessed May 14, 2022). 91. Stenographic transcript of Hearing to Receive Testimony on Security in Afghanistan and the Regions of South and Central Asia, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, October 26, 2021, p. 21, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/21-80_10-26-2021.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 92. Nahal Toosi, “Pakistan Terrorism Crackdown ‘Necessary’ to Trump’s Afghanistan Strategy,” Politico, August 22, 2017, https://www.politico.com/ story/2017/08/22/pakistan-terrorism-crackdown-necessary-to-trumps-afghanistan-strategy-241885 (accessed May 14, 2022). 94. “Figures in the CSF row reflect actual payments by appropriation year. The FY2015 NDAA authorized up to $1 billion in additional CSF to Pakistan, $300 million of which was subject to Haqqani Network-related certification requirements that cannot be waived by the Administration. The FY2016 NDAA authorized $900 million, with $350 million ineligible for waiver. The FY2017 NDAA again authorized $900 million, but with $400 million ineligible for waiver. The FY2018 NDAA authorized $700 million, with $350 million ineligible for waiver. The Administration did not issue certifications for FY2015-FY2018. The NDAA for FY2019 revamped the CSF program, authorizing $350 million to support security enhancement activities along Pakistan’s western border, subject to certification requirements that have not been met to date. The Pentagon has requested $450 million for global CSF for FY2020.” Table, “Direct Overt U.S. Aid Appropriations for and Military Reimbursements to Pakistan, FY2002– FY2020,” note g. 95. Press statement by Michael R. Pompeo, U.S. Secretary of State, “United States Takes Action Against Violators of Religious Freedom,” U.S. Mission to International Organizations in Geneva, December 20, 2019, https://geneva.usmission.gov/2019/12/20/united-states-takes-action-againstviolators-of-religious-freedom/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 96. Madiha Afzal, “Terrorism in Pakistan Has Declined, but the Underlying Roots of Extremism Remain,” Brookings Institution, Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors, January 15, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/01/15/terrorism-in-pakistan-has-declined-but-theunderlying-roots-of-extremism-remain/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 97. Ibid. 98. Daud Khattak, “The Pakistani Taliban Is Back,” The Diplomat, March 9, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/the-pakistani-taliban-is-back/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 99. Ayaz Gul, “Taliban Condemn Pakistan for Alleged Cross-Border Attacks in Afghanistan,” Voice of America, April 16, 2022, https://www.voanews. com/a/taliban-condemn-pakistan-for-alleged-cross-border-attacks-in-afghanistan/6532351.html (accessed May 14, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 187 93. Table, “Direct Overt U.S. Aid Appropriations for and Military Reimbursements to Pakistan, FY2002–FY2020,” Prepared by the Congressional Research Service for distribution to multiple congressional offices, March 12, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/pakaid.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). DOD’s “FY 2021 budget request for support for coalition forces,” however, “include[d] $180 million for the Coalition Support Fund (CSF)…. The FY 2021 CSF request of $180 million reflect[ed] a $45 million (20 percent) decrease from the FY 2020 enacted level of $225 million due to the continuing suspension of U.S. security assistance to Pakistan based on the President’s January 4, 2018, guidance.” U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer, United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Request: Defense Budget Overview, revised May 13, 2020, p. 6-6, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/ fy2021/fy2021_Budget_Request_Overview_Book.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 100. Ayaz Gul, “US Official Slams Taliban for Falling Short on Public Pledges,” Voice of America, October 8, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/usdiplomat-discusses-afghanistan-bilateral-ties-with-pakistan-leaders/6262799.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 101. Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Nuclear Notebook: How Many Nuclear Weapons Does Pakistan Have in 2021?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, September 7, 2021, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2021-09/nuclear-notebook-how-many-nuclear-weapons-does-pakistan-havein-2021/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 102. Table, “Theft Ranking: Countries with Weapons-Usable Nuclear Materials,” in Nuclear Threat Initiative, NTI Nuclear Security Index, Theft/ Sabotage: Building a Framework for Assurance, Accountability, and Action, September 2018, p. 10, https://media.nti.org/documents/NTI_2018_ Index_FINAL.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 103. Nuclear Threat Initiative, NTI Nuclear Security Index, Theft/Sabotage/Radiological, July 2020, p. 9, https://www.ntiindex.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/01/2020_NTI-Index_Report.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 104. Ayaz Gul, “Pakistan Equips Military with Tactical Nuke-Capable Missile,” Voice of America, updated January 25, 2019, https://www.voanews. com/a/pakistan-equips-military-with-tactical-nuke-capable-missile-/4757719.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 105. Associated Press, “Worst Fighting in Years over Disputed Kashmir,” CBS News, October 9, 2014, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/india-pakistanfighting-kashmir-thousands-civilians-flee-border-violence/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 106. Ralph Ellis, Euan McKirdy, and Harmeet Shah Singh, “Indian Prime Minister Urges Pakistan to Investigate Attack on Military Base,” CNN, updated January 5, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/01/04/asia/india-air-base-gunmen/index.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 107. Ravi Krishnan Khajuria, “Jammu Army Camp Attack: Two Soldiers Killed as JeM Militants Storm into Sunjuwan Base,” Hindustan Times, updated February 10, 2018, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/terrorists-attack-army-camp-in-jammu-soldier-and-daughter-injured/story20lLSRP8tuSE6UM2nvxt1O.html (accessed June 21, 2021), and BBC News, “Pulwama Attack: Nine Killed in Kashmir Gun Battle,” February 18, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-47275072 (accessed May 14, 2022). 108. Joanna Slater, “India Strikes Pakistan in Severe Escalation of Tensions Between Nuclear Rivals,” The Washington Post, February 26, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/pakistan-says-indian-fighter-jets-crossed-into-its-territory-and-carried-out-limitedairstrike/2019/02/25/901f3000-3979-11e9-a06c-3ec8ed509d15_story.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 109. BBC News, “India and Pakistan Blame Each Other over Kashmir Shelling,” October 21, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asiaindia-50120613 (accessed May 14, 2022). 110. Special Correspondent, “Parliament Proceedings: 5,133 Ceasefire Violations Along LoC Last Year: Government,” The Hindu, updated February 9, 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/parliament-proceedings-46-security-personnel-killed-in-ceasefire-violations-by-pakistan-in2020-rajnath-singh/article33782464.ece (accessed May 14, 2022). 111. Press release, “Joint Statement,” Government of India, Ministry of Defence, February 25, 2021, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage. aspx?PRID=1700682 (accessed May 14, 2022). 112. “Read: Full Text of Gen Bajwa’s Speech at the Islamabad Security Dialogue,” Dawn, March 18, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1613207/readfull-text-of-gen-bajwas-speech-at-the-islamabad-security-dialogue (accessed May 14, 2022). 113. Press release, “Statement on Accidental Firing of Missile,” Government of India, Ministry of Defense, March 11, 2022, https://pib.gov.in/ PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1805148 (accessed May 14, 2022). 114. Umair Jamal, “Pakistan Alarmed over India’s Accidental Missile Firing,” The Diplomat, March 14, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/03/ pakistan-alarmed-over-indias-accidental-missile-firing/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 115. See Robert C. O’Brien, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, “A Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” January 5, 2021, https:// trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/OBrien-Expanded-Statement.pdf (accessed May 18, 2022), and Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States, The White House, February 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-PacificStrategy.pdf (accessed May 18, 2022). See also Bruce Vaughn, Emma Chanlett-Avery, Ben Dolven, K. Alan Kronstadt, Susan V. Lawrence, Thomas Lum, Wayne M. Morrison, and Ronald O’Rourke, “The Trump Administration’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’: Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. R45396, updated October 3, 2018, https://crsreports.congress.gov/ product/pdf/R/R45396 (accessed May 18, 2022). 116. Jeff M. Smith, “Modi 2.0: Navigating Differences and Consolidating Gains in India–U.S. Relations,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3425, August 5, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/modi-20-navigating-differences-and-consolidating-gains-india-us-relations. 117. Jeff Smith, “Austin Goes to India: An Agenda for India–U.S. Defense Consultations,” Heritage Foundation Issue Brief No. 6067, March 18, 2021, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/austin-goes-india-agenda-india-us-defense-consultations. 118. Press release, “Fourth Annual U.S.–India 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue,” U.S. Department of State, April 11, 2022, https://www.state.gov/fourth-annualu-s-india-22-ministerial-dialogue/ (accessed May 18, 2022), and press release, “Readout of U.S.–India 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 11, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2996350/readout-of-us-india-22-ministerial-dialogue/#. YlTOVV8flao.twitter (accessed May 18, 2022). 119. Press release, “Readout of U.S.–India 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue.” 188 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 120. Megan Eckstein, “Japan Cabinet Approves Aegis Ashore Buy to Supplement DDGs in Ballistic Missile Defense,” U.S. Naval Institute News, December 22, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/12/22/japan-cabinet-approves-aegis-ashore-buy-supplement-ddgs-ballistic-missile-defense (accessed May 14, 2022). 121. Masaya Kato, “Japan Stuck with $1.6bn Bill After Scrapping Aegis Ashore System,” Nikkei Asia, June 18, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/ Politics/International-relations/Japan-stuck-with-1.6bn-bill-after-scrapping-Aegis-Ashore-system (accessed May 14, 2022), and Kyodo News, “Japan Suspends Plan to Deploy Aegis Ashore Missile Defense System,” The Japan Times, June 15, 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/ news/2020/06/15/national/japan-halt-deploy-aegis-ashore-missile-defense-system/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 122. Australian Government, Department of Defence, “Operations: Current Operations,” https://www1.defence.gov.au/operations (accessed May 14, 2022). 123. Table, “Military Expenditure by Country, in Constant (2019) US$ m., 1988–2020,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2021, https:// sipri.org/sites/default/files/Data%20for%20all%20countries%20from%201988%E2%80%932020%20in%20constant%20%282019%29%20 USD%20%28pdf%29.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 124. Jeremy Koh, “Made for Singapore: First of Four Custom-Built RSN Submarines Launched in Germany,” CNA, February 19, 2019, https://www. milipolasiapacific.com/news-post/made-for-singapore-first-of-four-custom-built-rsn-submarines-launched-in-germany/#:~:text=%2D%20 September%202021-,Made%20for%20Singapore%3A%20First%20of%20four%20custom%2Dbuilt,RSN%20submarines%20launched%20in%20 Germany&text=KIEL%2C%20Germany%3A%20The%20first%20of,on%20Monday%20(Feb%2018) (accessed May 14, 2022). 125. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2022), pp. 303-305. 126. Mike Yeo, “US Approves Location for Singaporean F-16, F-35 Training,” Defense News, June 4, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/trainingsim/2021/06/04/us-approves-location-for-singaporean-f-16-f-35-training/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 127. Table, “Military Expenditure by Country as Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, 1988–2020,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2021, https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/Data%20for%20all%20countries%20from%201988%E2%80%932020%20as%20a%20share%20of%20 GDP%20%28pdf%29.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 128. Raissa Robles, “Philippine Navy Seeks ‘Dream Fleet’ in South China Sea, Buys Two South Korean Warships to Ramp Up Maritime Defences,” South China Morning Post, December 29, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3161455/philippine-navy-seeks-dream-fleetsouth-china-sea-buys-two-south (accessed May 14, 2022). 129. Frances Mangosing, “PH, South Korea Discuss Corvettes, Light Fighter Jet Upgrades,” Inquirer.net, December 16, 2020, https://globalnation. inquirer.net/192725/ph-south-korea-discuss-corvettes-light-fighter-jet-upgrades (accessed May 19, 2022). 130. Mike Yeo, “Philippine Air Force Modernizes Fleet Following Financial Troubles, Historical Inaction,” Defense News, February 14, 2022, https:// www.defensenews.com/air/2022/02/14/philippine-air-force-modernizes-fleet-following-financial-troubles-historical-inaction/ (accessed May 19, 2022). 131. Government of France, Directorate General for International Relations and Strategy, France and Security in the Indo-Pacific, updated May 2019, pp. 6 and 8, https://franceintheus.org/IMG/pdf/France_and_Security_in_the_Indo-Pacific_-_2019.pdf (accessed May 14, 2022). 132. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, “About USINDOPACOM,” http://www.pacom.mil/About-USINDOPACOM/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 133. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, “Area of Responsibility,” last updated March 2022, https://www.pacom.mil/About-USINDOPACOM/USPACOM-Areaof-Responsibility/ (accessed May 19, 2022). 134. Ibid. 135. MyBaseGuide, “Hawaii—Army Community: Brief History: U.S. Army, Pacific (USARPAC),” https://mybaseguide.com/installation/hawaii-army/ community/brief-history-6/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 136. 354th Fighter Wing Public Affairs, “Eielson Completes F-35A Lightning II Fleet,” Eielson Air Force Base, April 15, 2022, https://www.eielson.af.mil/ News/Articles/Article/3001623/eielson-completes-f-35a-lightning-ii-fleet/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 137. Steaming times calculated using Marine Vessel Traffic, “Sea Distance Calculator,” http://www.marinevesseltraffic.com/2013/07/distance-calculator. html (accessed May 14, 2022). 138. U.S. Marine Corps, “History: Historical Summary of Marines on Guam," https://www.mcbblaz.marines.mil/History/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 139. Alex Wilson, “Contracts for Marines Corps’ New Base on Guam Are Nearing $1.5 billion,” Stars and Stripes, April 20, 2022, https://www.stripes. com/theaters/asia_pacific/2022-04-20/marine-corps-base-camp-blaz-guam-construction-okinawa-5742329.html (accessed May 14, 2022). 140. Air Force Technology, “B-2 Spirit Stealth Bomber,” April 24, 2020, http://www.airforce-technology.com/projects/b2/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 141. Press release, “Sixth United States–Philippines Bilateral Strategic Dialogue Joint Statement,” U.S. Department of State, March 18, 2016, https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2016/03/254833.htm (accessed May 14, 2022). 142. News release, “U.S., Philippines Cut the Ribbon on Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement Project,” U.S. Embassy in the Philippines, January 30, 2019, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1744271/us-philippines-cut-the-ribbon-on-enhanced-defensecooperation-agreement-project/ (accessed May 14, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 189 143. Staff Sgt. Anthony Small, “US, Philippine AF Concludes [sic] Bilateral Air Contingency Exchange,” U.S. Air Force, February 6, 2019, https://www. af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/1749908/us-philippine-af-concludes-bilateral-air-contingency-exchange/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 144. Michael J. Green and Gregory B. Poling, “The U.S. Alliance with the Philippines,” Center for Strategic and International Studies Commentary, December 3, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-alliance-philippines (accessed May 14, 2022). 145. Fact Sheet, “U.S. Security Cooperation with Singapore,” U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, April 20, 2021, https://www. state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-singapore/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 146. See, for example, Wyatt Olson, “Deal Likely to Bring More US Assets to Australia,” Stars and Stripes, June 20, 2014, https://www.stripes.com/ news/deal-likely-to-bring-more-us-military-assets-to-australia-1.289846 (accessed May 14, 2022). 147. Smith, Ministerial Statement on “Full Knowledge and Concurrence.” 148. Grady Fontana, “Military Sealift Command’s USNS Pililaau Delivers Cobra Gold 18 Essentials,” U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, February 9, 2018, https://www.dvidshub.net/news/265236/military-sealift-commands-usns-pililaau-deliverscobra-gold-18-essentials (accessed May 14, 2022). 149. Ibid. See also Rear Adm. (Ret.) Michael McDevitt, “America’s Interest in Diego Garcia,” War on the Rocks, June 3, 2020, https://warontherocks. com/2020/06/americas-interest-in-diego-garcia/ (accessed May 14, 2022). 150. For an example of a very accessible database, see World Bank, “Logistics Performance Index: Quality of Trade and Transport-Related Infrastructure (1=Low to 5=High),” 2007–2018, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/LP.LPI.INFR.XQ (accessed May 14, 2022). 190 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Conclusion: Scoring the Global Operating Environment T of the Russian government’s ability to conduct the war in Ukraine. Both NATO and many non-NATO European countries have reason to be increasingly concerned about the behavior and ambitions of both Russia and China, although agreement on a collective response to these challenges remains elusive. The past year saw continued U.S. military and political reengagement with the continent along with increases in European allies’ defense budgets and capability investment. Additional deployments to Europe following the invasion of Ukraine have made the U.S. military presence in Europe the strongest it has been for several years. The economic, political, and societal impacts of the invasion are only beginning to be felt and will undoubtedly have to be reckoned with for years to come. However, NATO has maintained its collective defense posture throughout despite the draining of its material resources as the alliance sends equipment and munitions into Ukraine to strengthen that country’s ability to defend itself. It is difficult to predict whether NATO’s renewed emphasis on collective defense and its reinvigorated defense spending will continue over the long term or is merely a short-term response to Russia’s invasion. Given the potential for Russia to replace its Global Operating Environment VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE FAVORABLE Europe Middle East EXCELLENT % % Asia % OVERALL % The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 191 he United States is a global power with global security interests, and threats to those interests can emerge from any region. Consequently, the U.S. military must be ready to operate in any region when called upon to do so and must account for the range of conditions that it might encounter when planning for potential military operations. These considerations necessarily inform its decisions about the type and amount of equipment it purchases (especially to transport and sustain the force); the location or locations from which it might operate; and how easily it can or cannot project and sustain combat power when engaged with the enemy. Aggregating the three regional scores provides a global operating environment score of FAVORABLE in the 2023 Index. Europe. Overall, the European region remains a stable, mature, and friendly operating environment. Russia remains the preeminent military threat to the region, both conventionally and unconventionally, and its invasion of Ukraine marks a serious escalation of its efforts to exert influence on its periphery. China continues to have a significant presence in Europe through its propaganda, influence operations, and investments in key sectors. By mitigating the effect of sanctions, it also has been a key enabler Global Operating Environment: Summary VERY POOR UNFAVORABLE MODERATE battlefield losses with newer, more modern equipment, NATO defense spending on capability will be an important issue in the medium to long terms. Scores for Europe remained steady this year as they did in 2021 (assessed in the 2022 Index), with no substantial changes in any individual categories or average scores. The 2023 Index again assesses the European operating environment as “favorable.” The Middle East. The Middle East region is now highly unstable, in large measure because of the erosion of authoritarian regimes and the fact that the region remains a breeding ground for terrorism. Overall, regional security has continued to deteriorate. Although Iraq has restored its territorial integrity since the defeat of ISIS, the political situation and future relations between Baghdad and the United States will remain difficult as long as a government that is sympathetic to Iran is in power. U.S. relations in the region will remain complex, but this has not stopped the U.S. military from operating as needed. The supremacy of the nation-state is being challenged in many countries by non-state actors that wield influence and power comparable to those of small states. The region’s primary challenges—continued meddling by Iran and surging transnational terrorism—are made more difficult by Sunni–Shia sectarian divides, the more aggressive nature of Iran’s Islamist revolutionary nationalism, and the proliferation of Sunni Islamist revolutionary groups. COVID-19 exacerbated these economic, political, and regional crises during 2020 and 2021 and continued to do so throughout 2022. The result could well be further destabilization of the post-pandemic operational environment for U.S. forces. In the Middle East, the U.S. benefits from operationally proven procedures that leverage bases, infrastructure, and the logistical processes needed to maintain a large force that is forward deployed thousands of miles away from the homeland. The personal links between allied armed forces are also present, and joint training exercises improve interoperability and provide an opportunity for the U.S. to influence some of the region’s future leaders. 192 FAVORABLE EXCELLENT America’s relationships in the region are based pragmatically on shared security and economic concerns. As long as these issues remain relevant to both sides, the U.S. is likely to have an open door to operate in the Middle East when its national interests require that it do so. Although circumstances in all measured areas vary throughout the year, in general terms, the 2023 Index assesses the Middle East operating environment as “moderate,” but the region’s political stability continues to be “unfavorable” and will remain a dark cloud over everything else. Asia. The Asian strategic environment includes half of the globe and is characterized by a variety of political relationships among states with wildly varying capabilities. This makes Asia far different from Europe, which in turn makes America’s relations with the region different from its relations with Europe. American conceptions of Asia must recognize the physical limitations imposed by the tyranny of distance and the need to move forces as necessary to respond to challenges from China and North Korea. The complicated nature of intra-Asian relations and the lack of an integrated, regional security architecture along the lines of NATO make defense of U.S. security interests in Asia more challenging than many Americans appreciate. However, the U.S. has strong relations with allies in the region, and their willingness to host bases helps to offset the vast distances that must be covered. The militaries of Japan and the Republic of Korea are larger and more capable than European militaries, and both countries are becoming more interested in developing missile defense capabilities that will be essential in combatting the regional threat posed by North Korea. In Japan, there is a growing public awareness of the need to adopt a more “normal” military posture in response to China’s increasingly aggressive actions. This indicates a break with the pacifist tradition among the Japanese that has lasted since the end of World War II and could lead to improved military capabilities and the prospect of joining the U.S. in defense measures beyond the immediate vicinity of Japan. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength We continue to assess the Asia region as “favorable” to U.S. interests in terms of alliances, overall political stability, militarily relevant infrastructure, and the presence of U.S. military forces. Summarizing the condition of each region enables us to get a sense of how they compare in terms of the difficulty that would be involved in projecting U.S. military power and sustaining combat operations in each one. As a whole, the global operating environment maintains a score of “favorable,” which means that the United States should be able to project military power anywhere in the world to defend its interests without substantial opposition or high levels of risk. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 193 Threats to U.S. Vital Interests Assessing Threats to U.S. Vital Interests B ecause the United States is a global power with global interests, scaling its military power to threats requires judgments with regard to the importance and priority of those interests, whether the use of force is the most appropriate and effective way to address the threats to those interests, and how much and what types of force are needed to defeat such threats. This Index focuses on three fundamental, vital national interests: l l Defense of the homeland; l l Preservation of freedom of movement within the global commons: the sea, air, outer space, and cyberspace domains through which the world conducts business. The geographical focus of the threats in these areas is further divided into three broad regions: Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. Obviously, these are not America’s only interests. Among many others are the growth of economic freedom in trade and investment, the observance of internationally recognized human rights, and the alleviation of human suffering beyond our borders. None of these other interests, however, can be addressed principally and effectively by the use of military force, and threats to them would not necessarily result in material damage to the foregoing vital national interests. Therefore, however important these additional American interests may be, we do not use them in assessing the adequacy of current U.S. military power. There are many publicly available sources of information on the status, capabilities, and activities l The Military Balance is an excellent, widely consulted source, but it is primarily a count of military hardware, often without context in terms of equipment capability, maintenance and readiness, training, manpower, integration of services, doctrine, or the behavior of competitors that threaten the national interests of the U.S. as defined in this Index. Each edition of the publication includes topical essays and a variety of focused discussions about some aspect of a selected country’s capabilities, but there is no overarching assessment of military power referenced against a set of interests, potential consequences of use, or implications for the interaction of countries. The ODNI’s “Annual Assessment” omits many threats, and its analysis of those that it does address is limited. Moreover, it does not reference underlying strategic dynamics that are key to the evaluation of threats and that may be more predictive of future threats than is a simple extrapolation of current events. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 197 Successful conclusion of a major war that has the potential to destabilize a region of critical interest to the U.S.; and of countries with respect to military power. Perhaps the two most often cited as references are The Military Balance, published annually by the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS),1 and the “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community.”2 The former is an unmatched resource for researchers who want to know, for example, the strength, composition, and disposition of a country’s military services. The latter serves as a reference point produced by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). Comparison of our detailed, peer-reviewed analysis of specific countries with The Military Balance and the ODNI’s “Annual Assessment” reveals two stark limitations in these external sources. Threat Categories Behavior HOSTILE AGGRESSIVE TESTING ASSERTIVE BENIGN Capability FORMIDABLE GATHERING CAPABLE ASPIRATIONAL MARGINAL We suspect that this is a consequence of the U.S. intelligence community’s withholding from public view its very sensitive assessments, which are derived from classified sources and/or result from analysis of unclassified, publicly available documents with the resulting synthesized insights being classified because of what they reveal about U.S. determinations and concerns. The need to avoid the compromising of sources, methods of collection, and national security findings makes such a policy understandable, but it also causes the ODNI’s annual threat assessments to be of limited value to policymakers, the public, and analysts working outside of the government. Consequently, we do not use the ODNI’s assessment as a reference, given its quite limited usefulness, but trust that the reader will double-check our conclusions by consulting the various sources cited in the following pages as well as other publicly available reporting that is relevant to the challenges to core U.S. security interests that are discussed in this section. Measuring or categorizing a threat is problematic because there is no absolute reference that can be used in assigning a quantitative score. Two fundamental aspects of threats, however, are germane to this Index: l l The threatening entity’s desire or intent to achieve its objective and Its physical ability to do so. Physical ability is the easier of the two to assess; intent is quite difficult. A useful surrogate for intent is observed behavior because this is where intent becomes manifest through action. Thus, a provocative, belligerent pattern of behavior that seriously threatens U.S. vital interests would be very worrisome. Similarly, a comprehensive ability to accomplish objectives even in the face of U.S. military power would be of serious concern to U.S. policymakers, and weak or very limited abilities would lessen U.S. concern even if an entity behaved provocatively vis-à-vis U.S. 198 interests. It is the combination of the two—behavior and capability—that informs our final score for each assessed actor. Each categorization used in the Index conveys a word picture of how troubling a threat’s behavior and set of capabilities have been during the assessed year. The five ascending categories for observed behavior are: l Benign, l Assertive, l Testing, l Aggressive, and l Hostile. The five ascending categories for physical capability are: l Marginal, l Aspirational, l Capable, l Gathering, and l Formidable. As noted, these characterizations—behavior and capability—form two halves of an overall assessment of the threats to U.S. vital interests. The most current and relatable example of this interplay between behavior and capability is Russia’s brutal assault on Ukraine. Throughout its buildup of forces along Ukraine’s border during 2021, Russia consistently downplayed observers’ concerns that its actions were a prelude to war. Regardless of its protestations, however, one could not dismiss the potential for grievous harm that was inherent in 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Russia’s forces and their disposition. Russia’s behavior, combined with the military capability it had deployed in posture and geographic position, belied its official pronouncements. The same thing can be said about China, Iran, and North Korea. Like Russia, each of these countries typically tries to refute observers’ concerns that its military activities, posturing, and investments threaten the interests of neighbors, as well as distant competitors like the U.S., but no rational country can ignore the potential that is inherent in the forces that each country fields, the investments it is making to improve and expand its capabilities, and a pattern of behavior that reveals its regime’s preference for intimidation and coercion over diplomacy and mutually beneficial economic interaction. It is therefore in the core interest of the United States to take stock of the capabilities and behaviors of its chief adversaries as it considers the capacity, capability, and readiness of its own military forces. We always hold open the possibility of adding to or deleting from our list of threat actors. The inclusion of any state or non-state entity is based solely on our assessment of its ability to present a meaningful challenge to a critical U.S. interest during the assessed year. Endnotes 1. For the most recent of these authoritative studies, see International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2022). 2. See Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “2022 Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” February 7, 2022, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2022-Unclassified-Report.pdf (accessed July 13, 2022). Issued before 2021 as “Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community.” The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 199 China Dean Cheng I n its 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, the Biden Administration made clear that it sees China as a major and growing threat: “China…has rapidly become more assertive” and “is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.1 While this is labeled an interim guidance, it probably will be reflected eventually in the Administration’s full National Security Strategy when it is issued. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 201 Threats to the Homeland Both China and Russia are seen as revisionist powers, but they pose very different challenges to the United States. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has the world’s second-largest gross domestic product (GDP), and its economy as measured in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP) is far larger than the U.S. economy.2 China is also an integral and important part of the global supply chain for crucial technologies, especially those relating to information and communications technology. As a result, it has the resources to support a comprehensive military modernization program that has been ongoing for more than two decades and spans the conventional, space, and cyber realms as well as weapons of mass destruction, an area that includes a multipronged nuclear modernization effort. At the same time, the PRC has been acting more assertively—even aggressively—against a growing number of its neighbors. Unresolved land and maritime disputes have led Beijing to adopt an increasingly confrontational attitude toward territorial disputes in the South China Sea, in the East China Sea, and along the China–India border, and Beijing’s reaction to the Democratic Progressive Party’s victories in Taiwan’s 2016 and 2020 elections has heightened cross-Strait tensions. In May 2020, the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission reported that, “[w]ith the world distracted by COVID-19, China also intensified its multi-faceted pressure campaign against Taiwan. Chinese military aircraft crossed the median line of the Taiwan Strait three times in the early months of 2020 after only one such incursion in 2019.” The commission further noted that China conducted several provocative military exercises around the island and “continued its efforts to poach Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic allies as the virus spread.”3 Since then, China has been intruding regularly across the median line of the Taiwan Strait with ever-larger groups of aircraft. Meanwhile, China’s attempts to obscure the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic and stifle international investigations into the matter have undermined global health efforts. Beijing has also sought to exclude Taiwan from multilateral efforts to combat the pandemic. Growing Conventional Capabilities. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) remains one of the world’s largest militaries, but its days of largely obsolescent equipment are in the past. Nearly two decades of officially acknowledged double-digit growth in the Chinese defense budget have resulted in a comprehensive modernization program that has benefited every part of the PLA. This has been complemented by improvements in Chinese military training and, in 2015, the largest reorganization in the PLA’s history.4 The PLA has lost 300,000 personnel since those reforms, but its overall capabilities have increased as newer, much more sophisticated systems have replaced older platforms. A major part of the 2015 reorganization was the establishment of a separate ground forces headquarters and bureaucracy; previously, the ground forces had been the default service providing staffs and commanders. Now the PLA Army (PLAA), responsible for the PLA’s ground forces, is no longer automatically in charge of war zones or higher headquarters functions. At the same time, the PLAA has steadily modernized its capabilities, incorporating both new equipment and a new organization. It has shifted from a division-based structure toward a brigade-based one and has been improving its mobility, including heliborne infantry and fire support.5 These forces are increasingly equipped with modern armored fighting vehicles, air defenses, both tube and rocket artillery, and electronic support equipment. The PLA Navy (PLAN) is Asia’s largest navy “and within the past few years…has surpassed the U.S. Navy in numbers of battle force ships (meaning the types of ships that count toward the quoted size of the U.S. Navy).”6 According to the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD): The PLAN is the largest navy in the world with a battle force of approximately 355 platforms, including major surface combatants, submarines, aircraft carriers, ocean-going amphibious ships, mine warfare ships, and fleet auxiliaries. This figure does not include 85 patrol combatants and craft that carry anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs). The PLAN’s overall battle force is expected to grow to 420 ships by 2025 and 460 ships by 2030.7 Although the total number of ships has dropped, the PLAN has fielded increasingly sophisticated and capable multi-role ships. Multiple classes of surface combatants are now in series production, including the Type 055 cruiser and the Type 052C and Type 052D guided missile destroyers, each of which fields long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) and anti-ship cruise missile systems, as well as the Type 054 frigate and Type 056 corvette. The PLAN has similarly been modernizing its submarine force. Since 2000, the PLAN has consistently fielded between 50 and 60 diesel-electric submarines, but the age and capability of the force have been improving as older boats, especially 1950s-vintage Romeo-class boats, are replaced with newer designs. These include a dozen Kilo-class submarines 202 purchased from Russia and domestically designed and manufactured Song and Yuan classes. All of these are believed to be capable of firing both torpedoes and anti-ship cruise missiles.8 The Chinese have also developed variants of the Yuan, with an air-independent propulsion (AIP) system that reduces the boats’ vulnerability by removing the need to use noisy diesel engines to recharge batteries, and are “expected to produce a total of 25 or more Yuan class submarines by 2025.”9 The PLAN has been expanding its amphibious assault capabilities as well. The PLA Marine Corps, for example, is China’s counterpart to the U.S. Marine Corps. According to the DOD: The PLANMC previously consisted of two brigades (approximately 10,000 personnel) and was limited in geography and mission to amphibious assault and defense of South China Sea outposts. In 2020, the PLANMC continued to mature an enlarged force structure of eight brigades intended to be scalable and mobile, modernize its capabilities for joint expeditionary operations—including operations beyond the First Island Chain—and become more proficient in conventional and irregular warfare. Throughout 2020, the PLANMC continued to work towards fully equipping and training its four newly established maneuver brigades (in addition to its two previously existing brigades), a SOF brigade, and an aviation (helicopter) brigade.10 To move this force, the Chinese have begun to build more amphibious assault ships, including Type 071 amphibious transport docks.11 Each can carry about 800 naval infantrymen and move them to shore by means of four air-cushion landing craft and four helicopters. Supporting these expanded naval combat forces is a growing fleet of support and logistics vessels. The 2010 PRC defense white paper noted the accelerated construction of “large support vessels.” It also noted specifically that the navy is exploring “new methods of logistics support for sustaining long-time maritime missions.”12 These include tankers and fast combat support ships that extend the range of Chinese surface groups and allow them to operate for more prolonged periods away from main ports. Chinese naval task forces dispatched to the Gulf of Aden have typically included such vessels. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength the American F-22 fighter. The J-31 appears to resemble the F-35 but with two engines rather than one. The production of advanced combat aircraft engines remains one of the greatest challenges to Chinese fighter design. The PLAAF is also deploying increasing numbers of H-6 bombers, which can undertake longer-range strike operations including operations employing land-attack cruise missiles. Although the H-6, like the American B-52 and Russian Tu-95, is a 1950s-era design copied from the Soviet-era Tu-16 Badger bomber, the latest versions (H-6K) are equipped with updated electronics and engines and are made of carbon composites. In addition, China is developing the H-20, a flying wing–type stealth bomber that is probably similar to the U.S. B-2.17 Equally important, the PLAAF has been introducing a variety of support aircraft, including airborne early warning (AEW), command and control (C2), and electronic warfare (EW) aircraft. These systems field state-of-the-art radars and electronic surveillance systems that allow Chinese air commanders to detect potential targets, including low-flying aircraft and cruise missiles, more quickly and gather additional intelligence on adversary radars and electronic emissions. China’s combat aircraft are also increasingly capable of undertaking mid-air refueling, which allows them to conduct extended, sustained operations, and the Chinese aerial tanker fleet, which is based on the H-6 aircraft, has been expanding. At the biennial Zhuhai Air Show, Chinese comAlthough they currently have limited power panies have displayed a variety of unmanned aerial projection capability, both the PLAAF and vehicles that reflect substantial investments and rePLAN Aviation are seeking to extend their search and development efforts. The surveillance reach. The PLAAF, in particular, has received and armed UAV systems include the Xianglong repeated calls from its leadership to become a (Soaring Dragon) and Sky Saber systems. The DOD’s truly “strategic” air force, able to project power 2019 report on Chinese capabilities stated that at long distances and support Chinese national China had “successfully tested the AT-200, which interests wherever they extend.15 it claims is the ‘world’s first large cargo UAV,’” and further specified that “[t]his drone can carry up to The PLAAF currently has more than 700 1.5 tons of cargo and… may be especially suited to fourth-generation fighters that are comparable to provide logistic support to PLA forces in the South the U.S. F-15, F-16, and F-18. They include the do- China Sea.”18 Chinese UAVs have been included in mestically designed and produced J-10 as well as the various military parades over the past several years, Su-27/Su-30/J-11 system, which is comparable to suggesting that they are being incorporated into the F-15 or F-18 and dominates both the fighter and Chinese forces, and the DOD’s 2021 report on Chistrike missions.16 China is also believed to be pre- nese capabilities states that “The PLAAF continues paring to field two stealthy fifth-generation fighter to modernize with the delivery of domestically built designs. The J-20 is the larger aircraft and resembles aircraft and a wide range of UAVs.”19 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 203 The PLAN has also been expanding its naval aviation capabilities, the most publicized element of which has been the growing Chinese carrier fleet. This currently includes not only the Liaoning, purchased from Ukraine over a decade ago, but a domestically produced copy, the Shandong, that completed its first exercise in 2021.13 Both of these ships have ski jumps for their air wing, but the Chinese are also building several conventional takeoff/barrier landing (CATOBAR) carriers (like American or French aircraft carriers) that will employ catapults and therefore allow their air complement to carry more ordnance and/or fuel.14 The PLAN’s land-based element is modernizing as well, with a variety of long-range strike aircraft, anti-ship cruise missiles, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) entering the inventory. In addition to more modern versions of the H-6 twin-engine bomber (a version of the Soviet/Russian Tu-16 Badger), the PLAN’s Naval Aviation force has added a range of other strike aircraft to its inventory. These include the JH-7/FBC-1 Flying Leopard, which can carry between two and four YJ-82 anti-ship cruise missiles, and the Su-30 strike fighter. The PLA Air Force (PLAAF), with more than 1,700 combat aircraft, is Asia’s largest air force. It has shifted steadily from a force focused on homeland air defense to one that is capable of power projection, including long-range precision strikes against both land and maritime targets. The DOD’s 2021 report on Chinese capabilities notes that: The PLAAF is also responsible for the Chinese homeland’s strategic air defenses. Its array of surface-to-air missile batteries is one of the world’s largest and includes the Russian S-300 (SA-10B/ SA-20) and its Chinese counterpart, the Hongqi-9 long-range SAM. The S-400 series of Russian longrange SAMs, delivery of which began in 2018, mark a substantial improvement in PLAAF air defense capabilities, as the S-400 has both anti-aircraft and anti-missile capabilities.20 China has deployed these SAM systems in a dense, overlapping belt along its coast, protecting the nation’s economic center of gravity. Key industrial and military centers such as Beijing are also heavily defended by SAM systems. China’s airborne forces are part of the PLAAF. The 15th Airborne Corps has been reorganized from three airborne divisions to six airborne brigades in addition to a special operations brigade, an aviation brigade, and a support brigade. These forces have been incorporating indigenously developed airborne mechanized combat vehicles for the past decade, giving them more mobility and a better ability to engage armored forces. Nuclear Capability. Chinese nuclear forces are the responsibility of the PLA Rocket Forces (PLARF), one of the three new services created on December 31, 2015. China’s nuclear ballistic missile forces include land-based missiles with a range of 13,000 kilometers that can reach the U.S. and CSS4 and submarine-based missiles that can reach the U.S. when the submarine is deployed within missile range. The PRC became a nuclear power in 1964 when it exploded its first atomic bomb as part of its “two bombs, one satellite” effort. China then exploded its first thermonuclear bomb in 1967 and orbited its first satellite in 1970, demonstrating the capability to build a delivery system that can reach the ends of the Earth. China chose to rely primarily on a land-based nuclear deterrent instead of developing two or three different basing systems as the United States did. Unlike the United States or the Soviet Union, China chose to pursue only a minimal nuclear deterrent. The PRC fielded only a small number of nuclear weapons: 100–150 weapons on medium-range ballistic missiles and approximately 60 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Its only ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) conducted relatively few deterrence patrols (perhaps none),21 and its first-generation submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), 204 the JL-1, if it ever attained full operational capability had limited reach. The JL-1’s 1,700-kilometer range makes it comparable to the first-generation Polaris A1 missile fielded by the U.S. in the 1960s. After remaining stable for several decades, China’s nuclear force became part of Beijing’s two-decade modernization effort. The result has been both modernization and expansion of the Chinese nuclear deterrent. The core of China’s ICBM force is the DF-31 series, a solid-fueled, road-mobile system, along with a growing number of longer-range, road-mobile DF-41 missiles that may already be in the PLA operational inventory. The DOD’s 2019 report on Chinese capabilities characterized the DF-41 as “a new MIRV-capable, road-mobile ICBM,”22 and its 2021 report (as have previous reports) again states that “China appears to be considering additional DF-41 launch options, including rail-mobile and silo basing.”23 China’s medium-range nuclear forces have similarly shifted to mobile, solid-rocket systems so that they are both more survivable and more easily maintained. This past year has seen a sudden inflation in the number of strategic nuclear warheads available to the PLA Rocket Force. Imagery analysts at several think tanks discovered at least three fields of silos under construction in western China.24 Each appears to contain around 100 silos, indicating that China could expand its land-based nuclear deterrent component by more than an order of magnitude. Notably, the Chinese are also expanding their ballistic missile submarine fleet. Replacing the one Type 092 Xia-class SSBN are six Type 094 Jin-class SSBNs, all of which are operational. Equipped with the longer-range JL-2 SLBM, “the PLAN’s six operational Jin class SSBNs represent the PRC’s first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent.” In addition, “[e]ach Jin class SSBN can carry up to 12 JL-2 SLBMs.”25 There is some possibility that the Chinese nuclear arsenal now contains land-attack cruise missiles. The CJ-20, a long-range, air-launched cruise missile carried on China’s H-6 bomber, may be nuclear-tipped, although there is not much evidence that China has pursued such a capability. China is also believed to be working on a cruise missile submarine that, if equipped with nuclear cruise missiles, would further expand the range of its nuclear attack options.26 As a result of its modernization efforts, China’s nuclear forces appear to be shifting from a minimal 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength (FOBS) could allow attacks from southern trajectories (that is, from over the South Pole) or even the placement of warheads in orbit, which would make them almost impossible to intercept. Even without a nuclear warhead, an orbiting hypersonic vehicle could do enormous damage to a city or a military facility such as an air base or an ICBM silo. Notably, because of the strategic instability that FOBS programs would introduce, neither the U.S. nor the Soviet Union ever pursued them. Cyber and Space Capabilities. The PLA’s major 2015 reorganization included creation of the PLA Strategic Support Force (PLASSF), which brings the Chinese military’s electronic, network (including cyber), and space warfare forces under a single service umbrella. Previously, these capabilities had been embedded in different departments across the PLA’s General Staff Department and General Armaments Department. By consolidating them into a single service, the PLA has created a Chinese “information warfare” force that is responsible for offensive and defensive operations in the electromagnetic and space domains. Chinese network warfare forces are known to have conducted a variety of cyber and network reconnaissance operations as well as cyber economic espionage. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice charged PLA officers from Unit 61398, then of the General Staff Department’s 3rd Department, with the theft of intellectual property and implanting of malware in various commercial firms.29 Members of that unit are thought also to be part of Advanced Persistent Threat-1, a group of computer hackers believed to be operating on behalf of a nation-state rather than a criminal group. In 2020, the Department of Justice charged several PLA officers with one of the largest breaches in history: stealing the credit ratings and records of 147 million people from Equifax.30 The PRC has been conducting space operations since 1970 when it first orbited a satellite, but its space capabilities didn’t gain public prominence until 2007 when the PLA conducted an anti-satellite (ASAT) test in low-Earth orbit against a defunct Chinese weather satellite. The test became one of the worst debris-generating incidents of the space age: Many of the several thousand pieces of debris that were generated will remain in orbit for more than a century. Equally important, Chinese counter-space efforts have been expanding steadily. The PLA not only has The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 205 deterrent posture, suited only to responding to an attack and then with only limited numbers, to a more robust but still limited deterrent posture. While the PRC will still likely field fewer nuclear weapons than either the United States or Russia, it will field a more modern and diverse set of capabilities than India, Pakistan, or North Korea, its nuclear-armed neighbors, are capable of fielding. If there are corresponding changes in doctrine, modernization will enable China to engage in limited nuclear options in the event of a conflict. This assessment changes, however, if the missiles going into the newly discovered silos are equipped with MIRVs (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles). With five MIRVs atop each missile, for example, 300 new ICBMs would have some 1,500 warheads—equivalent to the U.S. and Russian numbers allowed under New START. Even with fewer than 300 ICBMs, the new SLBMs and new bombers would enable China, within a few years, to field as large a nuclear force as the United States or Russia is capable of fielding. In addition to strategic nuclear forces, the PLARF has responsibility for medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic missile (MRBM and IRBM) forces. These include (among others) the DF-21 MRBM, which has a range of approximately 1,500 kilometers, and the DF-26 IRBM, which has a range of approximately 3,000 kilometers and “is capable of conducting precision conventional or nuclear strikes against ground targets, such as U.S. military bases on Guam, as well as against maritime targets.”27 It is believed that Chinese missile brigades equipped with these systems may have both nuclear and conventional responsibilities, making any deployment from garrison much more ambiguous from a stability perspective. The expansion of these forces also raises questions about the total number of Chinese nuclear warheads. While it is unclear whether they are nuclear-armed, China’s hypersonic glide vehicles also pose a growing threat to the United States and its allies. Hypersonic glide vehicles are slower than ICBMs—Mach 5 for a hypersonic vehicle as opposed to Mach 25 for an ICBM warhead—but are designed to maneuver during their descent, making interception far more difficult. During a Chinese test in August 2021, a hypersonic vehicle apparently went into orbit.28 This creates a fundamentally different threat, as a fractional orbital bombardment system tested ASATs against low-Earth orbit systems, but also is believed to have tested a system designed to attack targets at geosynchronous orbit (GEO) approximately 22,000 miles above the Earth. As many vital satellites are at GEO, including communications and missile early-warning systems, China’s ability to target such systems constitutes a major threat. In early 2022, China’s Shijian-22 towed a dead Chinese satellite into a “graveyard” orbit above the GEO belt.31 While this was officially touted as a servicing operation, the ability to attach one satellite to another and then tow it also has potential military implications. The creation of the PLASSF, incorporating counter-space forces, reflects the movement of counter-space systems, including direct-ascent ASATs, out of the testing phase to fielding with units. In 2018, for example, the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) noted that “China has military units that have begun training with anti-satellite missiles.”32 Threats to the Commons The U.S. has critical sea, air, space, and cyber interests at stake in the East Asia and South Asia international common spaces. These interests include an economic interest in the free flow of commerce and the military use of the commons to safeguard America’s own security and contribute to the security of its allies and partners. Washington has long provided the security backbone in these areas, and this in turn has supported the region’s remarkable economic development. However, China is taking increasingly assertive steps—including the construction of islands atop previously submerged features—to secure its own interests, and two things seem obvious: China and the United States do not share a common conception of international space, and China is actively seeking to undermine American predominance in securing international common spaces. In addition, as China expands its naval capabilities, it will be present farther and farther away from its home shores. As part of this effort, it established its first formal overseas military base in 2017 pursuant to an agreement with the government of Djibouti. Dangerous Behavior in the Maritime and Airspace Common Spaces. The aggressiveness of the Chinese navy, maritime law enforcement forces, and air forces in and over the waters of the East 206 China Sea and South China Sea, coupled with ambiguous, extralegal territorial claims and assertion of control there, poses an incipient threat to American and overlapping allied interests. Chinese military writings emphasize the importance of establishing dominance of the air and maritime domains in any future conflict. Although the Chinese do not necessarily have sufficient capacity to prevent the U.S. from operating in local waters and airspace, the ability of the U.S. to take control at acceptable costs in the early stages of a conflict has become a matter of greater debate.33 A significant factor in this calculus is the fact that China has “fully militarized at least three of several islands it built in the disputed South China Sea, arming them with anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems, laser and jamming equipment and fighter jets in an increasingly aggressive move that threatens all nations operating nearby.”34 China also has been intensifying its challenges to long-standing rivals Vietnam and the Philippines and has begun to push toward Indonesia’s Natuna Islands and into waters claimed by Malaysia. It is unclear whether China is yet in a position to enforce an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) consistently, but the steady two-decade improvement of the PLAAF and PLAN naval aviation will eventually provide the necessary capabilities. Chinese observations of recent conflicts, including wars in the Persian Gulf, the Balkans, and Afghanistan, have emphasized the growing role of airpower and missiles in conducting “non-contact, non-linear, non-symmetrical” warfare.35 This growing parity, if not superiority, constitutes a radical shift from the Cold War era when the U.S. and its allies clearly would have dominated air and naval operations in the Pacific. China has also begun to employ nontraditional methods of challenging foreign military operations in what Beijing regards as its territorial waters and airspace. It has employed lasers, for example, against foreign air and naval platforms, endangering pilots and sailors by threatening to blind them.36 Increased Military Space Activity. One of the key force multipliers for the United States is its extensive array of space-based assets. Through its various satellite constellations, the U.S. military can track opponents, coordinate friendly forces, engage in precision strikes against enemy forces, and conduct battle-damage assessments so that its munitions are expended efficiently. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength mode.42 Before it was finally brought under control, it had drifted through a portion of the geosynchronous belt, forcing other satellite owners to move their assets and juggle frequencies. A deliberate such attempt by China (or any other country) could prove far harder to handle, especially if conducted in conjunction with attacks by kinetic systems or directed-energy weapons. Most recently, China has landed an unmanned probe at the lunar south pole on the far side of the Moon. This is a major accomplishment because the probe is the first spacecraft ever to land at either of the Moon’s poles. To support this mission, the Chinese deployed a data relay satellite to Lagrange Point-2, one of five points where the gravity wells of the Earth and Sun “cancel out” each other, allowing a satellite to remain in a relatively fixed location with minimal fuel consumption. While the satellite itself may or may not have military roles, the deployment highlights that China will now be using the enormous volume of cis-lunar space (the region between the Earth and the Moon) for various deployments. This will greatly complicate American space situational awareness efforts by forcing the U.S. to monitor a vastly greater area of space for possible Chinese spacecraft. The Chinese Chang’e-5 lunar sample retrieval mission in 2020 and the recent Chinese landing on Mars underscore China’s effort to move beyond Earth orbit to cis-lunar and interplanetary space. Cyber Activities and the Electromagnetic Domain. As far back as 2013, the Verizon Risk Center identified China as the “top external actor from which [computer] breaches emanated, representing 30 percent of cases where country-of-origin could be determined.”43 Given the difficulties of attribution, country of origin should not necessarily be conflated with perpetrator, but forensic efforts have associated at least one Chinese military unit with cyber intrusions, albeit many years ago.44 The Verizon report similarly concluded that China was the source of 95 percent of state-sponsored cyber espionage attacks. Since the 2015 summit meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Barack Obama, during which the two sides reached an understanding to reduce cyber economic espionage, Chinese cyber actions have shifted. Although the overall level of activity appears to be unabated, the Chinese seem to have moved toward more focused attacks mounted from new sites. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 207 Because the American military is expeditionary—meaning that its wars are fought far from the homeland—its reliance on space-based systems is greater than that of many other militaries. Consequently, it requires global rather than regional reconnaissance, communications and data transmission, and meteorological information and support. At this point, only space-based systems can provide this sort of information on a real-time basis. No other country is capable of leveraging space as the U.S. does, and that is a major advantage. However, this heavy reliance on space systems is also a key American vulnerability. China fields an array of space capabilities, including its own BeiDou/Compass system of navigation and timing satellites, and has claimed a capacity to refuel satellites.37 It has four satellite launch centers. China’s interest in space dominance includes not only accessing space, but also denying opponents the ability to do the same. As one Chinese assessment notes, space capabilities provided 70 percent of battlefield communications, more than 80 percent of battlefield reconnaissance and surveillance, and 100 percent of meteorological information for American operations in Kosovo. Moreover, 98 percent of precision munitions relied on space for guidance information. In fact, “[i]t may be said that America’s victory in the Kosovo War could not [have been] achieved without fully exploiting space.”38 To this end, the PLA has been developing a range of anti-satellite capabilities that include both hardkill and soft-kill systems. The former include direct-ascent kinetic-kill vehicles (DA-KKV) such as the system famously tested in 2007, but they also include more advanced systems that are believed to be capable of reaching targets in mid-Earth orbit and even geosynchronous orbit.39 The latter include anti-satellite lasers for either dazzling or blinding purposes.40 This is consistent with PLA doctrinal writings, which emphasize the need to control space in future conflicts. “Securing space dominance has already become the prerequisite for establishing information, air, and maritime dominance,” says one Chinese teaching manual, “and will directly affect the course and outcome of wars.”41 Soft-kill attacks need not come only from dedicated weapons, however. The case of Galaxy-15, a communications satellite owned by Intelsat Corporation, showed how a satellite could disrupt communications simply by always being in “switched on” China’s cyber espionage efforts are often aimed at economic targets, reflecting China’s much more holistic view of both security and information. Rather than creating an artificial dividing line between military security and civilian security, much less information, the PLA plays a role in supporting both aspects and seeks to obtain economic intellectual property as well as military electronic information. This is not to suggest that the PLA has not emphasized the military importance of cyber warfare. Chinese military writings since the 1990s have emphasized a fundamental transformation in global military affairs. Future wars will be conducted through joint operations involving multiple services, not through combined operations focused on multiple branches within a single service, and will span not only the traditional land, sea, and air domains, but also outer space and cyberspace. The latter two arenas will be of special importance because warfare has shifted from an effort to establish material dominance (characteristic of industrial age warfare) to establishing information dominance. This is due to the rise of the information age and the resulting introduction of information technology into all areas of military operations. Consequently, according to PLA analysis, future wars will most likely be “informationized local wars.” That is, they will be wars in which information and information technology will be both widely applied and a key basis of victory. The ability to gather, transmit, analyze, manage, and exploit information will be central to winning such wars: The side that is able to do these things more accurately and more quickly will be the side that wins. This means that future conflicts will no longer be determined by platform-versus-platform performance and not even by system against system: Conflicts are now clashes between rival systems of systems.45 Chinese military writings suggest that a great deal of attention has been focused on developing an integrated computer network and electronic warfare (INEW) capability. This would allow the PLA to reconnoiter a potential adversary’s computer systems in peacetime, influence opponent decision-makers by threatening those same systems in times of crisis, and disrupt or destroy information networks and systems by cyber and electronic warfare means in the event of conflict. INEW capabilities would complement psychological warfare and physical attack efforts to secure “information dominance,” which 208 Chinese military writings emphasize as essential for fighting and winning future wars. It is essential to recognize, however, that the PLA views computer network operations as part of information operations, or information combat. Information operations are specific operational activities that are associated with striving to establish information dominance. They are conducted in both peacetime and wartime with the peacetime focus on collecting information, improving its flow and application, influencing opposing decision-making, and effecting information deterrence. Information operations involve four mission areas: l l l l Command and Control Missions. An essential part of information operations is the ability of commanders to control joint operations by disparate forces. Command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance structures therefore constitute a key part of information operations by providing the means for collecting, transmitting, and managing information. Offensive Information Missions. These are intended to disrupt the enemy’s battlefield command and control systems and communications networks, as well as to strike the enemy’s psychological defenses. Defensive Information Missions. Such missions are aimed at ensuring the survival and continued operation of information systems. They include deterring an opponent from attacking one’s own information systems, concealing information, and combating attacks when they do occur. Information Support and Information-Safeguarding Missions. The ability to provide the myriad types of information necessary to support extensive joint operations and to do so on a continuous basis is essential to their success.46 Computer network operations are integral to all four of these overall mission areas. They can include both strategic and battlefield network operations and can incorporate both offensive and defensive 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength measures. They also include protection not only of Chinese fighters, along with airborne early data, but also of information hardware and operatwarning aircraft, have increased their exercises ing software. southwest of Taiwan, demonstrating a growing Finally, computer network operations will not ability to conduct flexible air operations and stand alone; they will be integrated with electronic reduced reliance on ground-based control.50 warfare operations as reflected in the phrase “network and electronics unified.” Electronic warfare For at least six months in 2021, the Chioperations are aimed at weakening or destroying ennese maintained a warship between Taiwan emy electronic facilities and systems while defendand the string of Japanese islands south47 ing one’s own. The combination of electronic and west of Kyushu.51 computer network attacks will produce synergies that affect everything from finding and assessing the The PLA has undertaken sustained joint adversary, to locating one’s own forces, to weapons exercises to simulate extended air operations, guidance, to logistical support and command and employing both air and naval forces including control. The creation of the PLASSF is intended to its aircraft carriers.52 integrate these forces and make them more complementary and effective in future “local wars under These activities continued unabated and, in some informationized conditions.” ways, even intensified in the wake of China’s struggle with COVID-19.53 Threat of Regional War Regardless of the state of the relationship at any Three issues, all involving China, threaten Amer- given time, Chinese leaders from Deng Xiaoping and ican interests and embody the “general threat of re- Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping have consistently emphagional war” noted at the outset of this section: the sized the importance of ultimately reclaiming Taistatus of Taiwan, the escalation of maritime and wan. The island—along with Tibet—is the clearest territorial disputes, and border conflict with India. example of a geographical “core interest” in Chinese Taiwan. China’s long-standing threat to end the policy. China has never renounced the use of force, de facto independence of Taiwan and ultimately to and it continues to employ political warfare against bring it under the authority of Beijing—by force if Taiwan’s political and military leadership. necessary—is both a threat to a major American seFor the Chinese leadership, the failure to effect curity partner and a threat to the American interest unification, whether peacefully or by using force, in peace and stability in the Western Pacific. would reflect fundamental political weakness. For After easing for eight years, tensions across the this reason, China’s leaders cannot back away from Taiwan Strait have worsened as a result of Beijing’s the stance of having to unify the island with the reaction to the outcome of Taiwan’s 2016 and 2020 mainland, and the island remains an essential part presidential elections. Beijing has suspended most of the PLA’s “new historic missions,” shaping its acdirect government-to-government discussions with quisitions and military planning. Taipei and is using a variety of aid and investment It is widely posited that China’s anti-access/ efforts to deprive Taiwan of its remaining diplo- area-denial (A2/AD) strategy—the deployment matic partners. of an array of overlapping capabilities, including Beijing has also undertaken significantly es- anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), submarines, calated military activities directed at Taiwan. and long-range cruise missiles, satellites, and cyber For example: weapons—is aimed largely at forestalling American intervention in support of friends and allies In 2021, China sent more than 150 aircraft into in the Western Pacific, including Taiwan. By holdTaiwan’s air defense identification zone.48 ing at risk key American platforms and systems (for example, aircraft carriers), the Chinese seek In 2022, 39 Chinese aircraft, including fightto delay or even deter American intervention in ers, bombers, and support aircraft, conducted support of key friends and allies, thereby allowing the largest single incursions into Taiwanthe PRC to achieve a fait accompli. The growth of ese airspace.49 China’s military capabilities is specifically oriented l l l l The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 209 l MAP 4 Maritime Boundaries in the Taiwan Strait Territorial baseline Contiguous zone Taipei CHINA TAIWAN Taiwan Strait M ed Lin ian e Philippine Sea SOURCE: “America and China Spar over the Taiwan Strait,” The Economist, June 23, 2022, https://www.economist.com/china/2022/06/23/ america-and-china-spar-over-the-taiwan-strait (accessed August 18, 2022). A heritage.org toward countering America’s ability to assist in the defense of Taiwan. Moreover, China’s efforts to reclaim Taiwan are not limited to overt military means. The “three warfares” highlight Chinese political warfare methods, including legal warfare/lawfare, public opinion warfare, and psychological warfare. The PRC employs such approaches to undermine both Taiwan’s will to resist and America’s willingness to support Taiwan. The Chinese goal would be to “win without fighting”—to take Taiwan without firing a shot or with only minimal resistance before the United States could organize an effective response. Escalation of Maritime and Territorial Disputes. The PRC and other countries in the region see active disputes over the East and South China Seas not as differences regarding the administration of international common spaces, but rather as matters of territorial sovereignty. As a result, there exists the threat of armed conflict between China and 210 American allies that are also claimants, particularly Japan and the Philippines. Because its economic center of gravity is now in the coastal region, China has had to emphasize maritime power to defend key assets and areas. This need is exacerbated by China’s status as the world’s foremost trading state. China increasingly depends on the seas for its economic well-being. Its factories are powered by imported oil, and its diets contain a growing percentage of imported food. China relies on the seas to move its products to markets. Consequently, it not only has steadily expanded its maritime power, including its merchant marine and maritime law enforcement capabilities, but also has acted to secure the “near seas” as a Chinese preserve. Beijing prefers to accomplish its objectives quietly and through nonmilitary means. In both the East China Sea and the South China Sea, China has sought to exploit “gray zones,” gaining control incrementally and deterring others without resorting to 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength confrontation. This volatile situation has led to a variety of confrontations between China and other claimants, as well as with Indonesia, which is not claiming territory or rights disputed by anyone except (occasionally) China. China–Vietnam tensions in the region, for example, were on display again in 2020 when CCG vessels twice rammed and sank Vietnamese fishing boats near the disputed Paracel islands.59 Vietnam has also protested China’s decision to create additional administrative regions for the South China Sea, one centered on the Paracels and the other centered on the Spratlys.60 This is part of Beijing’s “legal warfare” efforts, which employ legal and administrative measures to underscore China’s claimed control of the South China Sea region. For this reason, conflict often occurs around Chinese enforcement of unilaterally determined and announced fishing bans.61 Because of the relationship between the Philippines and the United States, tensions between Beijing and Manila are the most likely to lead to American involvement in these disputes. There have been several incidents going back to the 1990s. The most contentious occurred in 2012 when a Philippine naval ship operating on behalf of the country’s coast guard challenged private Chinese poachers in waters around Scarborough Shoal. The resulting escalation left Chinese government ships in control of the shoal, after which the Philippines successfully challenged Beijing in the Permanent Court of Arbitration regarding its rights under the U.N. ConIn June 2016, a Chinese fighter made an “unvention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). There is safe” pass near a U.S. RC-135 reconnaissance no indication that the Chinese have reclaimed land aircraft in the East China Sea area. around the shoal as they did in the Spratlys, but they continue to control access to the reef, and the presIn March 2017, Chinese authorities warned the ence of the Chinese Coast Guard remains a source crew of an American B-1B bomber operating of confrontation.62 in the area of the ADIZ that they were flying In March and April of 2021, a similar dispute illegally in PRC airspace. In response to the seemed to be simmering around Whitsun Reef in incident, the Chinese Foreign Ministry called the Spratlys. The presence of more than two hunfor the U.S. to respect the ADIZ.57 dred Chinese fishing boats, among them known assets of China’s maritime militia,63 sparked protests In May 2018, the Chinese intercepted an Amer- from Manila. After a stay of a few weeks—which ican WC-135, also over the East China Sea.58 Beijing claimed was necessary because of the poor weather—most of the ships departed. The unprecThere have been no publicly reported ADIZ-related edented gathering of fishing boats and maritime confrontations since then. militia could be an attempt to establish a basis In the South China Sea, overlapping Chi- within the Philippines exclusive economic zone nese, Bruneian, Philippine, Malaysian, Vietnam- (EEZ) for a subsequent return backed by the Chiese, and Taiwanese claims raise the prospect of nese Coast Guard. l l l The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 211 the lethal use of force. It uses military and economic threats, bombastic language, and enforcement through legal warfare (including the employment of Chinese maritime law enforcement vessels) as well as military bullying. Chinese paramilitary-implemented, military-backed encroachment in support of expansive extralegal claims could lead to an unplanned armed clash. The growing tensions between China and Japan and among a number of claimants in the South China Sea are especially risky. In the former case, the most proximate cause is the dispute over the Senkakus. China has intensified its efforts to assert claims of sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands of Japan in the East China Sea. Beijing asserts both exclusive economic rights within the disputed waters and recognition of “historic” rights to dominate and control those areas as part of its territory.54 Chinese fishing boats (often believed to be elements of the Chinese maritime militia) and Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) vessels have been encroaching steadily on the territorial waters within 12 nautical miles of the uninhabited islands. In 2020, CCG or other government vessels repeatedly entered the waters around the Senkakus.55 In the summer of 2016, China deployed a naval unit (as opposed to the CCG) into the area.56 Beijing’s 2013 ADIZ declaration was just part of a broader Chinese pattern of using intimidation and coercion to assert expansive extralegal claims of sovereignty and/or control incrementally. For example: MAP 5 The Scope of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) ■ Exclusive Economic Zone RUSSIA U.S. Pacific Ocean AFRICA SOUTH AMERICA As shown in the map above, EEZs and other waters under national jurisdiction account for 40 percent of the world’s oceans. U.S. freedom of navigation worldwide would be compromised if national governments were granted expansive authority to restrict foreign militaries from operating in their EEZs. The South China Sea, virtually all of which is covered by various EEZ claims (see map at right), has become a particular flashpoint as China has sought to restrict freedom of navigation for U.S. military vessels there. Pacific Ocean CHINA Atlantic Ocean Indian Ocean CHINA AUSTRALIA TAIWAN BURMA LAOS PHILLIPINES THAILAND CAMBODIA VIETNAM South China Sea MALAYSIA MALAYSIA INDONESIA SOURCE: Heritage Foundation research. 212 A 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength heritage.org MAP 6 Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) Claims in the South China Sea Vietnam Taipei CHINA Philippines TAIWAN BURMA Malaysia Hong Kong Hanoi Brunei Indonesia 20°N LAOS THAILAND Paracel Islands VIETNAM Itu Aba Island Gaven Reefs 130°E 110°E Singapore Swallow Reef BRUNEI MALAYSIA INDONESIA Natuna Islands PHILIPPINES Hughes Reef Fiery Cross Reef Cuarteron Reef Kuala Lumpur 10°N Mischief Reef Spratly Islands Ho Chi Minh City Philippine Sea 120°E CAMBODIA Phnom Penh 100°E Manila South Thitu Island ChinaSouthwest Subi Reef Sea Cay Bangkok MALAYSIA Scarborough Shoal Woody Island Duncan Island China’s “Nine-Dash Line” Reclamation work done by: China Taiwan Philippines Vietnam Malaysia Airstrip 0° SOURCE: “China Has Militarised the South China Sea and Got Away with It,” The Economist, June 23, 2018, https://www.economist.com/ asia/2018/06/21/china-has-militarised-the-south-china-sea-and-got-away-with-it (accessed July 23, 2021). Jakarta Surabaja A heritage.org 10°S In each of these cases, the situation is exacerbated by rising Chinese nationalism.64 In the face of persistent economic challenges, nationalist themes are becoming an increasingly strong undercurrent and affecting policymaking. Although the nationalist phenomenon is not new, it is gaining force and complicating efforts to maintain regional stability. Governments may choose to exploit nationalism for domestic political purposes, but they also run the risk of being unable to control the genie that they have released. Nationalist rhetoric is mutually reinforcing, which makes countries less likely to back down than they might have been in the past. The increasing power that the Internet and social media provide to the populace, largely outside of government control, adds elements of unpredictability to future clashes. China’s refusal to accept the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration findings, which overwhelmingly favored the Philippines, despite both Chinese and Philippine accession to UNCLOS is a partial reflection of such trends. 20°S In case of armed conflict between China and the Philippines or between China and Japan, either by intention or because of an accidental incident at sea, the U.S. could be required to exercise its treaty The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 213 MAP 7 Chinese Fault Lines KAZ. MONGOLIA RUSSIA SOUTH KOREA JAPAN CHINA China-India Border Paracel Islands PAK. BURMA INDIA Arabian Sea Bay of Bengal East China Sea East China Sea Taiwan Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands 30°N South China Sea Spratly Islands PHILIPPINES South China Sea Philippine Sea 0° China-India Border. The Line of Actual Control represents one of the world’s longest disputed borders and has been the site of several standoffs between the Chinese and Indian militaries in recent years, including a border crisis in 2020 that resulted in the first casualties from hostilities at the border in more than 40 years. East China Sea. China claims the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, which are currently administered by Japan. In recent years, Chinese aircraft 120°E 90°E Indian Ocean and naval vessels have entered the airspace and territorial sea around the islands with growing frequency. 30°S Taiwan. The sovereignty of Taiwan remains unsettled. The People’s Republic of China disputes this status and regularly conducts provocative military maneuvers near Taiwan. South China Sea. The South China Sea hosts several territorial disputes between China and Taiwan and its SOURCE: Heritage Foundation research. 214 Southeast Asian neighbors. China's unlawful claims in the sea and attempts to restrict freedom of navigation there have also produced tensions with the U.S., which has sent aircraft and naval vessels through the South China Sea to signal its objections to the nature of China's claims. This has resulted in a number of confrontations between Chinese and U.S. vessels. A 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength heritage.org MAP 8 Disputed Borders Between India and China TAJIKISTAN Xinjiang Line of Control Aksai Chin Islamabad Jammu and Kashmir PAKISTAN Ladakh CHINA Qinghai Western Sector Eastern Sector Himachal Pradesh Middle Sector Uttarakhand TIBET AUTONOMOUS REGION Lhasa New Delhi Uttar Pradesh Sichuan h des Pra l a h ac Arun NEPAL BHUTAN Sikkim INDIA Yunnan BANGLADESH Dhaka BURMA Disputed borders Disputed territories Middle Sector. The Middle Sector, where the Indian states of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh meet the Tibet Autonomous Region, is the least contentious of the three main disputed “sectors,” with the least amount of territory contested. It is also the only sector for which the Chinese and Indian governments have formally exchanged maps delineating their claims. Eastern Sector. China claims nearly the entire Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which Beijing calls South Tibet. The McMahon Line, which has served as the de facto Line of Actual Control since 1962, was established in 1914 by the British and Tibetan representatives and is not recognized by China. The U.S. recognizes Arunachal Pradesh as sovereign Indian territory. SOURCE: Heritage Foundation research. commitments.65 Escalation of a direct U.S.–China incident is also not unthinkable. Keeping an inadvertent incident from escalating into a broader military confrontation would be difficult. This is particularly true in the East and South China Seas, where naval as well as civilian law enforcement vessels from both China and the U.S. operate in what the U.S. considers to be international waters. Western Sector. Aksai Chin, a barren plateau that was part of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, has been administered by the Chinese since they seized control of the territory in the 1962 Sino–Indian border conflict. One of the main causes of that war was India’s discovery of a road China had built through the region, which India considered its territory. Bay of Bengal A heritage.org The most significant development in the South China Sea during the past three years has been Chinese reclamation and militarization of seven artificial islands or outposts. In 2015, President Xi promised President Obama that China had no intention of militarizing the islands. That pledge has never been honored.66 In fact, as described by Admiral John Aquilino, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 215 in his March 2022 posture statement to the Senate Committee on Armed Services: [T]he PLA has deployed anti-ship cruise missiles, surface-to-air missiles, and jamming equipment to its artificial Spratly Islands features since 2018 and flown aircraft from those locations since 2020. The PLA has emplaced expansive military infrastructure in the SCS by building aircraft hangars sufficient to accommodate multiple fighter brigades, protective shelters for surface-to-air and anti-ship missiles, and significant fuel storage facilities.67 territory on the Depsang Plains in Ladakh. A visit to India by Chinese President Xi Jinping in September 2014 was overshadowed by another flare-up in border tensions when hundreds of Chinese PLA forces reportedly set up camps in the mountainous regions of Ladakh, prompting Indian forces to deploy to forward positions in the region. This border standoff lasted three weeks until both sides agreed to pull their troops back to previous positions. In 2017, Chinese military engineers were building a road to the Doklam plateau, an area claimed by both Bhutan and China, and this led to a confrontation between Chinese and Indian forces, the latter requested by Bhutanese authorities to provide assistance. The crisis lasted 73 days; both sides pledged to pull back, but Chinese construction efforts in the area have continued.70 Improved Chinese infrastructure not only would give Beijing the diplomatic advantage over Bhutan, but also could make the Siliguri corridor that links the eastern Indian states with the rest of the country more vulnerable. In June 2020, the situation escalated even further. Clashes between Indian and Chinese troops using rocks, clubs, and fists led to at least 20 Indian dead and (as the Chinese authorities recently admitted) at least four Chinese killed in the Galwan Valley area of Ladakh.71 In September, reports of shots exchanged near the Pangong Lake region signaled further potential escalation.72 India claims that China occupies more than 14,000 square miles of Indian territory in the Aksai Chin along its northern border in Kashmir, and China lays claim to more than 34,000 square miles of India’s northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh. The issue is also closely related to China’s concern for its control of Tibet and the presence in India of the Tibetan government in exile and Tibet’s spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama. China is building up military infrastructure and expanding a network of road, rail, and air links in its southwestern border areas. To meet these challenges, the Indian government has committed to expanding infrastructure development along the disputed border, although China currently holds a decisive military edge. According to the DOD’s 2021 annual report on the Chinese military, “[n]o substantial land has been reclaimed at any of the outposts since the PRC completed its extensive artificial manipulation in the Spratly Islands in late 2015, after adding more than 3,200 acres of land to the seven features it occupies in the Spratlys.”68 This would seem to suggest that the process has been completed. There is the possibility that China will ultimately try to assert its authority over the entire area by declaring an ADIZ above the South China Sea.69 There also are concerns that under the right circumstances, China will move against vulnerable targets like Philippines-occupied Second Thomas Shoal or Reed Bank, where a Chinese fishing boat in 2019 rammed and sank a Philippine boat, causing a controversy in Manila. There is also consistent speculation in the Philippines about when the Chinese will start reclamation work at Scarborough. This development in particular would facilitate the physical assertion of Beijing’s claims and enforcement of an ADIZ, regardless of the UNCLOS award. Border Conflict with India. The possibility of armed conflict between India and China, while currently remote, poses an indirect threat to U.S. interests because it could disrupt the territorial status quo and raise nuclear tensions in the region. A border conflict between India and China could also prompt Pakistan to add to regional instability by trying to take advantage of the situation. Long-standing border disputes that led to a Sino– Indian war in 1962 have again become a flashpoint in recent years. In April 2013, the most serious border Conclusion incident between India and China in more than two China presents the United States with the redecades occurred when Chinese troops settled for gion’s most comprehensive security challenge. It three weeks several miles inside northern Indian poses various threat contingencies across all three 216 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength areas of vital American national interests: homeland; regional war, including potential attacks on overseas U.S. bases as well as against allies and friends; and international common spaces. China’s provocative behavior is well documented. It is challenging the U.S. and its allies such as Japan at sea, in the air, and in cyberspace; it has raised concerns on its border with India; and it is a standing threat to Taiwan. Despite a lack of official transparency, publicly available sources shed considerable light on China’s rapidly growing military capabilities. The Chinese launched their first homegrown aircraft carrier during the past year and are fielding large numbers of new platforms for their land, sea, air, and outer-space forces as well as in the electromagnetic domain. The PLA has been staging larger and more comprehensive exercises, including major exercises in the East China Sea near Taiwan, that are improving the ability of the Chinese to operate their abundance of new systems. It also has continued to conduct probes of both the South Korean and Japanese ADIZs, drawing rebukes from both Seoul and Tokyo. This Index assesses the overall threat from China, considering the range of contingencies, as “aggressive” for level of provocation of behavior and “formidable” for level of capability. Threats: China HOSTILE Behavior TESTING ASSERTIVE BENIGN CAPABLE ASPIRATIONAL MARGINAL % FORMIDABLE Capability AGGRESSIVE GATHERING % The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 217 Endnotes 1. President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” The White House, March 2021, p. 8, https://www.whitehouse.gov/ wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 2. The size of a country’s economy can be measured in nominal terms as adjusted for underlying differences in the cost to produce a good—an adjustment known as purchasing power parity (PPP). In nominal GDP, the U.S. economy is larger than China’s; adjusted for PPP, China’s economy is larger than that of the U.S. See Graham Allison, Nathalie Kiersznowski, and Charlotte Fitzek, “The Great Economic Rivalry: China vs the U.S.,” Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Avoiding Great Power War Project, March 23, 2022, https://www. belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/GreatEconomicRivalry_Final_2.pdf (accessed September 30, 2022). 3. Anastasia Lloyd-Damnjanovic, “Beijing’s Deadly Game: Consequences of Excluding Taiwan from the World Health Organization During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission Issue Brief, May 12, 2020, p. 2, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/ files/2020-05/Beijings_Deadly_Game_Excluding_Taiwan_from_WHO_during_COVID-19_Pandemic.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 4. Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C. Saunders, Chinese Military Reform in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications, National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, China Strategic Perspectives No. 10, March 2017, passim, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 5. U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power: Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win, 2019, pp. 58–60, https:// apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1066163.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 6. Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL33153, updated March 8, 2022, p. 2, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/ RL33153.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). See also Table 2, “Numbers of Chinese and U.S. Navy Battle Force Ships, 2000–2030,” in ibid., p. 9. 7. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 49, https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINA L.PDF (accessed May 23, 2022). 8. Dennis Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan, “A Potent Vector: Assessing Chinese Cruise Missile Developments,” Joint Force Quarterly No. 75 (4th Quarter 2014), pp. 98–105, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-75/jfq-75_98-105_Gormley-et-al.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 9. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, pp. 49. 10. Ibid., p. 52. 11. U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power: Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win, p. 70. 12. Section II, “National Defense Policy,” in People’s Republic of China, Ministry of National Defense, White Paper, China’s National Defense in 2010, March 2011, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/publications/2021-06/23/content_4887922.htm (accessed May 23, 2022). 13. Kristin Huang, “Shandong Aircraft Carrier Group Concludes South China Sea Exercise,” South China Morning Post, May 2, 2021, https://www.scmp. com/news/china/military/article/3131977/shandong-aircraft-carrier-group-concludes-south-china-sea (accessed May 23, 2022). 14. Franz-Stefan Gady, “China’s New Aircraft Carrier to Use Advanced Jet Launch System,” The Diplomat, November 6, 2017, https://thediplomat. com/2017/11/chinas-new-aircraft-carrier-to-use-advanced-jet-launch-system/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 15. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 61. 16. International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2022: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2022), pp. 260–261. 17. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 145. 18. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019, p. 58, https://media.defense.gov/2019/May/02/2002127082/-1/-1/1/2019_CHINA_MILITARY_POWER_REPORT. pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 19. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 55. 20. Franz-Stefan Gady, “Russia Delivers 1st S-400 Missile Defense Regiment to China,” The Diplomat, April 3, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/04/ russia-delivers-1st-s-400-missile-defense-regiment-to-china/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 21. Andrew S. Erickson and Michael S. Chase, “China’s SSBN Forces: Transitioning to the Next Generation,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief, Vol. 9, Issue 12 (June 12, 2009), http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=35120#.U5G0OSjb5NQ (accessed May 23, 2022). 218 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 22. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019, p. 45. 23. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 62. 24. Brad Lendon, “China Is Building a Sprawling Network of Missile Silos, Satellite Imagery Appears to Show,” CNN, updated July 2, 2021, https:// www.cnn.com/2021/07/02/asia/china-missile-silos-intl-hnk-ml/index.html (accessed May 23, 2022); Matt Korda and Hans Kristensen, “China Is Building a Second Nuclear Missile Silo Field,” Federation of American Scientists, Strategic Security Blog, July 26, 2021, https://fas.org/blogs/ security/2021/07/china-is-building-a-second-nuclear-missile-silo-field/ (accessed May 23, 2022); and Shannon Bugos and Julia Masterson, “New Chinese Missile Silo Fields Discovered,” Arms Control Today, September 2021, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2021-09/news/new-chinesemissile-silo-fields-discovered (accessed May 23, 2022). 25. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 49. 26. For more information on China’s cruise missile program, see Dennis M. Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan, A Low-Visibility Force Multiplier: Assessing China’s Cruise Missile Ambitions (Washington: National Defense University Press, 2014), http://ndupress.ndu.edu/ Portals/68/Documents/Books/force-multiplier.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). Published by the NDU Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, “established as an integral part of the National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies on March 1, 2000.” 27. U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, pp. 61 (DF-21) and 78 (DF-26). 28. Chandelis Duster, “Top Military Leader Says China’s Hypersonic Missile Test ‘Went Around the World,’” CNN, updated November 18, 2021, https:// www.cnn.com/2021/11/17/politics/john-hyten-china-hypersonic-weapons-test/index.html (accessed May 23, 2022). 29. Press release, “U.S. Charges Five Chinese Military Hackers for Cyber Espionage Against U.S. Corporations and a Labor Organization for Commercial Advantage,” U.S. Department of Justice, May 19, 2014, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-charges-five-chinese-military-hackerscyber-espionage-against-us-corporations-and-labor (accessed May 23, 2022). 30. BBC News, “Equifax: US Charges Four Chinese Military Officers over Huge Hack,” February 11, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-uscanada-51449778 (accessed May 23, 2022). 32. National Air and Space Intelligence Center, “Competing in Space,” December 2018, p. 21, https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jan/16/2002080386/1/-1/1/190115-F-NV711-0002.PDF (accessed May 23, 2022). 33. Gregory B. Poling, “The Conventional Wisdom on China’s Island Bases Is Dangerously Wrong,” War on the Rocks, January 10, 2020, https:// warontherocks.com/2020/01/the-conventional-wisdom-on-chinas-island-bases-is-dangerously-wrong/ (accessed May 23, 2022), and J. Michael Dahm, “Beyond ‘Conventional Wisdom’: Evaluating the PLA’s South China Sea Bases in Operational Context,” War on the Rocks, March 17, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/03/beyond-conventional-wisdom-evaluating-the-plas-south-china-sea-bases-in-operational-context/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 34. Associated Press, “U.S. Admiral Says China Has Fully Militarized Islands,” Politico, March 20, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/03/20/ china-islands-militarized-missiles-00018737 (accessed May 23, 2022). 35. “Building an Active, Layered Defense: Chinese Naval and Air Force Advancement,” interview with Andrew S. Erickson, U.S. Naval War College, by Greg Chaffin, National Bureau of Asian Research, September 10, 2012, https://www.nbr.org/publication/building-an-active-layered-defensechinese-naval-and-air-force-advancement/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 36. Patrick M. Cronin and Ryan D. Neuhard, “Countering China’s Laser Offensive,” The Diplomat, April 2, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/ countering-chinas-laser-offensive/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 37. Xinhua, “China Announces Success in Technology to Refuel Satellites in Orbit,” June 30, 2016, http://www.china.org.cn/china/Off_the_Wire/201606/30/content_38784419.htm (accessed May 23, 2022). 38. Mei Lianju, Space Operations Teaching Materials (Beijing, PRC: Academy of Military Sciences Publishing House, 2013), p. 65. 39. See, for example, Brian Weeden, Through a Glass, Darkly: Chinese, American, and Russian Anti-Satellite Testing in Space, Secure World Foundation, March 17, 2014, https://swfound.org/media/167224/through_a_glass_darkly_march2014.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 40. Ian Easton, “The Great Game in Space: China’s Evolving ASAT Weapons Programs and Their Implications for Future U.S. Strategy,” Project 2049 Institute, 2009, pp. 4–5, https://project2049.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/china_asat_weapons_the_great_game_in_space.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 41. Mei Lianju, Space Operations Teaching Materials, p. 69. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 219 31. Andrew Jones, “China’s Shijian-21 Towed Dead Satellite to a High Graveyard Orbit,” SpaceNews, January 27, 2022, https://spacenews.com/chinasshijian-21-spacecraft-docked-with-and-towed-a-dead-satellite/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 42. Peter B. de Selding, “Runaway Zombie Satellite Galaxy 15 Continues to Pose Interference Threat,” Space.com, October 15, 2010, http://www. space.com/9340-runaway-zombie-satellite-galaxy-15-continues-pose-interference-threat.html (accessed May 23, 2022). Article “provided by SpaceNews.” 43. Verizon, 2013 Data Breach Investigations Report, pp. 21–22, https://cybersecurity.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/87/2019/04/data-breachinvestigations-report-2013.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). See also Elise Ackerman, “New Verizon Security Report Finds a Growing Number of Attacks by China’s Hacker Army,” Forbes, April 23, 2013, https://www.forbes.com/sites/eliseackerman/2013/04/23/new-verizon-security-reportfinds-a-growing-number-of-attacks-by-chinas-hacker-army/#11429f622c49 (accessed May 23, 2022), and Lucian Constantin, “Verizon: One in Five Data Breaches Are the Result of Cyberespionage,” PC World, April 23, 2013, http://www.pcworld.com/article/2036177/one-in-five-databreaches-are-the-result-of-cyberespionage-verizon-says.html (accessed May 23, 2022). 44. Mike Lennon, “Unit in China’s PLA Behind Massive Cyber Espionage Units,” SecurityWeek, February 18, 2013, https://www.securityweek.com/ cyber-unit-chinas-pla-behind-massive-cyber-espionage-operation-report (accessed May 23, 2022). For the full report, see Mandiant, APT1: Exposing One of China’s Cyber Espionage Units, https://www.mandiant.com/sites/default/files/2021-09/mandiant-apt1-report.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 45. Bai Bangxi and Jiang Lijun, “‘Systems Combat’ Is Not the Same as ‘System Combat,’” China National Defense Newspaper, January 10, 2008, cited in Dean Cheng, “U.S.–China Competition in Space,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Space, Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, September 27, 2016, p. 2, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/SY/SY16/20160927/105387/HHRG-114SY16-Wstate-ChengD-20160927.pdf (accessed May 23, 2022). 46. Guo Ruobing, Theory of Military Information Security (Beijing, PRC: National Defense University Publishing House, 2013), pp. 12–21. 47. Tan Rukan, Building Operational Strength Course Materials (Beijing, PRC: Academy of Military Sciences Publishing House, 2012), p. 204. 48. Helen Davidson, “China Sends Largest Incursion of Warplanes into Taiwan Defence Zone Since October,” The Guardian, January 24, 2022, https:// www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/24/china-sends-largest-incursion-of-warplanes-into-taiwan-defence-zone-since-october (accessed May 23, 2022). 49. Reuters, “Taiwan Reports New Large-Scale Chinese Air Force Incursion,” January 24, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwanreports-new-large-scale-chinese-air-force-incursion-2022-01-23/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 50. Reuters, “Taiwan Air Force Scrambles Again to Warn off Chinese Jets,” Al Jazeera, March 16, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/ taiwan-airforce-scrambles-warn-chinese-jets-200317003712908.html (accessed May23, 2022). 51. Davidson, “China Sends Largest Incursion of Warplanes into Taiwan Defence Zone Since October.” 52. Kristin Huang, “Chinese Air Force’s Drill ‘Aimed at Signalling Deterrent Around Taiwan,’” South China Morning Post, April 2, 2020, https://www. scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3077997/chinese-air-forces-drill-aimed-signalling-deterrent-around (accessed May 23, 2022). 53. Erin Hale, “In Shadow of Coronavirus, China Steps up Manoeuvres Near Taiwan,” Al Jazeera, April 23, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/ news/2020/04/shadow-coronavirus-china-steps-manoeuvres-taiwan-200422011542456.html (accessed May 23, 2022), and Yew Lun Tian and Ben Blanchard, “China Rattles Sabres as World Battles Coronavirus Pandemic,” Reuters, April 21, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-chinasecurity/china-rattles-sabres-as-world-battles-coronavirus-pandemic-idUSKBN2230GC (accessed May 23, 2022). 54. See Chapter 10, “The South China Sea Tribunal,” in Tufts University, The Fletcher School, Law of the Sea: A Policy Primer, https://sites.tufts.edu/ lawofthesea/chapter-ten/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 55. Kyodo News, “Japan Lodges Protests Against Chinese Maritime Intrusions Near Senkakus,” The Japan Times, April 22, 2020, https://www. japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/04/22/national/japan-protest-chinese-intrusions-senkakus/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 56. Ankit Panda, “Japan Identifies Chinese Submarine in East China Sea: A Type 093 SSN,” The Diplomat, January 16, 2018, https://thediplomat. com/2018/01/japan-identifies-chinese-submarine-in-east-china-sea-a-type-093-ssn/ (accessed May 23, 2022); Howard Wang, “China vs. Japan: Is the East China Sea Showdown Back on?” The National Interest, The Buzz Blog, June 7, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/china-vsjapan-east-china-sea-showdown-back-61492 (accessed May 23, 2022); and Ankit Panda, “China Patrol Ships Sustain Presence Near Senkaku Islands: Report,” The Diplomat, June 10, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/06/china-patrol-ships-sustain-presence-near-senkaku-islandsreport/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 57. Jason Le Miere, “China Claims U.S. Military Plane ‘Illegally’ Entered Chinese Air Defense Zone,” Newsweek, March 24, 2017, http://www.newsweek. com/china-claims-us-military-plane-illegally-entered-chinese-air-defense-zone-573711 (accessed May 23, 2022). 58. Hans Nichols and Courtney Kube, “Two Chinese Fighter Jets Intercept U.S. Plane over East China Sea, Officials Say,” NBC News, updated May 18, 2017, http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/two-chinese-fighter-jets-intercept-u-s-plane-officials-say-n761931 (accessed May 23, 2022). 59. Khanh Vu, “Vietnam Protests Beijing’s Sinking of South China Sea Boat,” Reuters, April 4, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-vietnamchina-southchinasea/vietnam-protests-beijings-sinking-of-south-china-sea-boat-idUSKBN21M072 (accessed May 23, 2022), and “Chinese Vessel Rams Vietnamese Fishing Boat in S. China Sea,” The Maritime Executive, June 14, 2020, https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/reportchinese-vessel-rams-vietnamese-fishing-boat-in-s-china-sea (accessed May 23, 2022). 60. Reuters, “Vietnam Protests Beijing’s Expansion in Disputed South China Sea,” April 19, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-vietnam-chinasouthchinasea/vietnam-protests-beijings-expansion-in-disputed-south-china-sea-idUSKBN2210M7 (accessed May 23, 2022). 220 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength 61. Tam Anh, “Vietnam Rejects China’s Illegal Fishing Ban,” Vn Express International, April 29, 2021, https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnamrejects-china-s-illegal-fishing-ban-4270611.html (accessed May 23, 2022). 62. Andreo Calonzo, “Philippines Slams China’s ‘Dangerous’ Move in Disputed Sea,” Bloomberg, updated May 3, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/ news/articles/2021-05-03/philippines-dials-up-protest-on-china-s-dangerous-sea-maneuver?sref=InMWfBxD (accessed May 23, 2022), and Reuters and Bloomberg, “Philippines Foreign Minister Issues Expletive-Laced Tweet over South China Sea Dispute,” The Straits Times, updated May 4, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/philippines-slams-china-for-dangerous-manoeuvre-in-disputed-south-china-sea (accessed May 23, 2022). 63. Center for Strategic and International Studies, Asia Transparency Initiative, “Caught on Camera: Two Dozen Militia Boats at Whitsun Reef Identified,” April 21, 2021, https://amti.csis.org/caught-on-camera-two-dozen-militia-boats-at-whitsun-reef-identified/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 64. “Philippines Has Ulterior Motives to Suddenly Hype up the Matter over Niu’e Jiao,” Global Times, April 5, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/ page/202104/1220284.shtml (accessed May 23, 2022). 65. Although it has long been a matter of U.S. policy that Philippine territorial claims in the South China Sea lie outside the scope of American treaty commitments, the treaty does apply in the event of an attack on Philippine “armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific.” Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines, August 30, 1951, Article V, http://avalon.law.yale. edu/20th_century/phil001.asp (accessed May 23, 2022). In any event, Article IV of the treaty obligates the U.S. in case of such an attack to “meet the common dangers in accordance with its constitutional processes.” Regardless of formal treaty obligations, however, enduring U.S. interests in the region and perceptions of U.S. effectiveness and reliability as a check on growing Chinese ambitions would likely spur the U.S. to become involved. 66. See, for example, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, “An Accounting of China’s Deployments to the Spratly Islands,” May 9, 2018, https://amti.csis.org/accounting-chinas-deployments-spratly-islands/ (accessed May 23, 2022). 67. Admiral John C. Aquilino, U.S. Navy, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, statement on “U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Posture” before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, March 10, 2022, p. 7, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/INDOPACOM%20 Statement%20(ADM%20Aquilino)%20_SASC2.PDF (accessed May 23, 2022). 68. U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 104. 69. Kelvin Chen, “China to Set up ADIZ in South China Sea,” Taiwan News, May 5, 2020, https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3928503 (accessed May 23, 2022). 71. BBC News, “Ladakh: China Reveals Soldier Deaths in India Border Clash,” February 19, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-56121781 (accessed May 23, 2022). 72. BBC News, “China Says Indian Troops Fired ‘Provocative’ Shots in Border Dispute,” September 8, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asiachina-54067400 (accessed May 23, 2022). The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 221 70. Joel Wuthnow, Satu Limaye, and Nilanthi Samaranayake, “Doklam, One Year Later: China’s Long Game in the Himalayas,” War on the Rocks, June 7, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/doklam-one-year-later-chinas-long-game-in-the-himalayas/ (accessed May 23, 2022). Russia Alexis Mrachek O Military Capabilities. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS): l l Among the key weapons in Russia’s inventory are 339 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs); 2,927 main battle tanks; 5,180 armored infantry fighting vehicles; more than 6,050 armored personnel carriers; and more than 4,894 pieces of artillery. The navy has one aircraft carrier; 49 submarines (including 11 ballistic missile submarines); four cruisers; 11 destroyers; 16 frigates; and 129 patrol and coastal combatants. l The air force has 1,172 combat-capable aircraft. l The army has 280,000 soldiers. l There is a total reserve force of 2,000,000 for all armed forces.1 Russia has suffered significant losses of tanks and other military hardware as a result of its assault on Ukraine, but in the coming years, it will come back with a vengeance in rebuilding its military. It will be replacing the destroyed tanks and equipment with newly developed versions, not the old Soviet versions. In addition, Russian deep-sea research vessels include converted ballistic missile submarines, which hold smaller auxiliary submarines that can operate on the ocean floor.2 In recent years, Russia has increasingly deployed paid private volunteer troops trained at Special Forces bases and often under the command of Russian Special Forces in order to avoid political blowback from military deaths abroad. It has used such The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 223 n February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. Employing a force of nearly 200,000 troops replete with armor, rocket and conventional artillery, and combat aircraft, President Vladimir Putin ordered a “special military operation” to seize Ukraine, destabilize if not overthrow its government, and neutralize its military. In addition to the tremendous losses borne by both sides, the war has depleted the military inventories of countries providing material support to Ukraine. The assault on Ukraine is glaring proof that Putin’s Russia is a profound threat to the U.S., its interests, and the security and economic interests of its allies, particularly in Europe but also more broadly given the reach of Russia’s military and the destructive ripple effect its use is having and can have across countries and regions of special importance to the United States. From the Arctic to the Baltics, Ukraine, and the South Caucasus, and increasingly in the Mediterranean, Russia continues to foment instability in Europe. Despite its economic problems, Russia continues to prioritize the rebuilding of its military and funding for its military operations abroad. Russia remains antagonistic to the United States both militarily and politically, and its efforts to undermine U.S. institutions and the NATO alliance continue unabated. In Europe, Russia uses its energy position along with espionage, cyberattacks, and information warfare to exploit vulnerabilities in an effort to divide the transatlantic alliance and undermine faith in government and societal institutions. Overall, Russia possesses significant conventional and nuclear capabilities and remains the principal threat to European security. Its aggressive stance in a number of theaters, including Ukraine, Georgia, the Balkans, and Syria, continues to encourage destabilization and threaten U.S. interests. volunteers in Libya, Syria, and Ukraine because they help the Kremlin to “keep costs low and maintain a degree of deniability,” and “[a]ny personnel losses could be shrouded from unauthorized disclosure.”3 In January 2019, reports surfaced that 400 Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group were in Venezuela to prop up the regime of Nicolás Maduro.4 Russian propaganda in Venezuela has supported the regime and stoked fears of American imperialism. In March 2022, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov met with Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodriguez to discuss “their countries’ strategic alliance,”5 and after Russia invaded Ukraine, Maduro “assured Vladimir Putin of his ‘strong support.’”6 During the past few years, as the crisis has metastasized and protests against the Maduro regime have grown, Russia has begun to deploy troops and supplies to strengthen Maduro’s security forces.7 In March 2019, for example, Russia deployed approximately 100 troops and military staff to Caracas.8 Russia also exports billions in arms to Venezuela (and has loaned the regime money to purchase Russian arms) along with $70 million–$80 million yearly in nonmilitary goods.9 In July 2016, Putin signed a law creating a National Guard with a total strength (both civilian and military) of 340,000, controlled directly by him.10 He created this force, which is responsible for “enforcing emergency-situation regimes, combating terrorism, defending Russian territory, and protecting state facilities and assets,” by amalgamating “interior troops and various law-enforcement agencies.”11 In November 2020, the Russian National Guard (Rosgvardia) and the Belarusian Ministry of the Interior signed an official cooperation deal specifying that either side “may carry out law-enforcement-type operations on the other’s territory.”12 Rosgvardia also has been involved in the war in Ukraine. In March 2022, Rosgvardia Director Viktor Zolotov stated that “National Guard units are not only involved in the fight against [the so-called Ukrainian] nationalists, [but] also fight to ensure public order and security in liberated localities, guard important strategic facilities, [and] protect humanitarian aid convoys.” Specifically, Rosgvardia was sent to seize control of various Ukrainian cities.13 The Russian economy rebounded during the latter part of the COVID-19 pandemic,14 but after Moscow launched its second invasion of Ukraine in 224 February 2022, Western sanctions had a significant effect on the economy.15 In 2021, Russia spent $65.9 billion on its military—6.37 percent more than it spent in 2020—and remained one of the world’s top five nations in terms of defense spending.16 Much of Russia’s military expenditure has been directed toward modernization of its armed forces. The U.S. Intelligence Community “expect[s] Moscow to sustain military modernization and enhance its armed forces, enabling it to defend Russia’s national security while projecting influence globally and challenging the interests of the United States and its allies.”17 From 2010 to 2019 (the most recent year for which data are publicly available), close to 40 percent of Russia’s total military spending was on arms procurement.18 Taking into account total military expenditure, Russia spent 3.77 percent of its GDP on defense in 2021, a slight decrease from 2020.19 This will surely increase as combat losses and consumption of war materiel in Ukraine continue to mount. In early 2018, Russia introduced its new State Armament Program 2018–2027, a $306 billion investment in new equipment and force modernization. According to the IISS, the program continues its predecessor’s emphasis on modernization, but some of its aims are more modest than they were.20 The extent to which modernization efforts are affected by the Russo–Ukraine war cannot yet be known, but it seems reasonable to assume that Russia will not be content with a reduced and damaged military regardless of the outcome of the war. Consequently, general defense expenditures and investments in modernization programs are likely to increase, especially as they are enabled by historically high energy revenues. Russia has prioritized modernization of its nuclear capabilities and claims that its nuclear trifecta is more than 89 percent of the way through its modernization from the Soviet era.21 Russia has been planning to deploy the RS-28 (Satan 2) ICBM as a replacement for the RS-36, which is being phased out in the 2020s.22 In June 2022, Putin announced in a speech that the missile had been “successfully tested” and, “with nuclear capability, will be deployed by the end of 2022.” In a television interview, Alexei Zhuravlyov, a member of the Russian State Duma, boasted “that the [RS-28] would reduce the United States to ‘nuclear ashes’ if they ‘think Russia should not exist.’”23 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength April 2020, it was reported that Russia’s Severnoye Design Bureau had halted development of the frigates because of financial setbacks.37 In November 2018, Russia sold four Admiral Grigorovich–class frigates to India, which should take delivery of all four by 2026.38 The ships had been intended for the Black Sea Fleet, but Russia found itself unable to produce a replacement engine following the imposition of Ukraine-related sanctions. Of the planned 14 frigates, Russia had engines for only two, but in January 2021, India procured gas turbine engines from Ukraine “and handed [them] over to Russia to install them on the Admiral Grigorovich-class guided-missile stealth frigates that are being made for the Indian Navy by a Russian shipyard as part of $2.5 billion deal.”39 Russia’s naval modernization continues to prioritize submarines. In June 2020, the first Project 955A Borei-A ballistic-missile submarine, the Knyaz Vladimir, was delivered to the Russian Northern Fleet as an addition to the three original Project 955 Boreis.40 In December 2021, Russia launched Knyaz Oleg and Novosibirsk, part of the Borei-A and Yasen-M submarine classes, respectively,41 in addition to Generalissimo Suvorov, the third of the upgraded Borei-A class submarines.42 The Novosibirsk is equipped with Kalibr cruise missiles.43 Russia reportedly will construct a total of 10 Borei-A class submarines; so far, five have been delivered.44 The Laika-class submarines (previously called Khaski) are planned fifth-generation stealth nuclear-powered submarines. They are slated to begin construction in 2023 and to be armed with Zircon hypersonic missiles, which have a reported speed of from Mach 5 to Mach 6.45 According to a Russian vice admiral, these submarines will be two times quieter than current subs.46 Construction of the first Laika is scheduled for the end of 2030.47 Russia also continues to upgrade its diesel electric Kilo-class subs.48 It reportedly inducted the first improved Project 636.6 Kilo-class submarine into its Pacific Fleet in November 2019.49 Russia launched the third of six Project 06363 improved Kilo-class subs in March 2021, and all six are to be built by 2024.50 According to one assessment, the submarines’ improved noise reduction has caused them to be nicknamed “Black Holes,” but “the submarine class lacks a functioning air-independent propulsion system, which reduced the boats’ overall stealth capabilities.”51 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 225 In April 2020, the Kremlin stated that it had begun state trials for its T-14 Armata main battle tank in Syria.24 After a series of delays, Russian troops allegedly will receive more than 40 Armata tanks in 2023.25 Aside from the T-14 Armata, 10 new-build T-90M main battle tanks, contracted in 2017, were delivered to the 2nd Motor-Rifle Division in the Moscow region in 2020.26 At the Army-2021 Forum, according to TASS, the Russian Defense Ministry “signed a contract with the Uralvagonzavod plant (part of the Rostec state corporation) stipulating the delivery of another batch of T-90M Proryv tanks and modernization of T-90 tanks to T-90M level.”27 Russia’s fifth-generation Su-27 fighter has fallen short of expectations, particularly with regard to stealth capabilities. In May 2018, the government cancelled mass production of the Su-27 because of its high costs and limited capability advantages over upgraded fourth-generation fighters.28 Russia lost one of its Su-27 jets near the Crimean coast during a planned mission in March 2020.29 In July 2021, Russia premiered the prototype for its Su-75 LTS Checkmate, which will be “the world’s second single-engine fighter plane to incorporate the most sophisticated radar-evasion and command systems.”30 The only other plane in this category is the F-35. In December 2019, Russia’s sole aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, caught on fire during repair work.31 The carrier was scheduled to begin sea trials in 2022,32 but the addition of a propeller-rudder system, hull repairs, and an assortment of delays in other maintenance work have caused the trials to be delayed until 2024.33 In May 2019, reports surfaced that Russia is seeking to begin construction of a new nuclear-powered aircraft carrier in 2023 for delivery in the late 2030s, but the procurement’s financial and technological feasibility remains questionable.34 Following years of delays, the Admiral Gorshkov stealth guided missile frigate was commissioned in July 2018. According to one report, the Russian Navy is expected to add 10 new Gorshkov-class frigates and 14 Steregushchiy-class corvettes by 2027. Russia is also significantly upgrading its nuclear-powered battle cruiser Admiral Nakhimov, which is expected to become the “most powerful surface vessel in the Russian Navy” and be ready for sailing in 2023.35 Russia plans to procure eight Lider-class guided missile destroyers for its Northern and Pacific Fleets, but procurement has faced consistent delay.36 In Transport remains a nagging problem, and Rus- 2021, it was revealed that three Voronezh radars will sia’s defense minister has stressed the paucity of be modernized as part of Russia’s missile attack eartransport vessels. According to a RAND report: ly warning system by 2028.57 Military Exercises. Russian military exercises, In 1992, just after the collapse of the Soviet especially snap exercises, are a source of serious conUnion, the Russian Federation military had cern because they have masked real military operamore than 500 transport aircraft of all types, tions in the past. Their purpose is twofold: to project which were capable of lifting 29,630 metric strength and to improve command and control. In tons. By 2017, there were just over 100 available March 2022, Air Force General Tod D. Wolters, then transport aircraft in the inventory, capable of Commander, U.S. European Command (EUCOM), lifting 6,240 metric tons, or approximately onetestified that: fifth of the 1992 capacity.52 Russia maintains a large conventional force That number is even lower now. At least two Ruspresence along NATO’s borders and conducts sian transport aircraft were shot down right after snap exercises to increase instability. Russia Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine, which began employs unconventional tools, ranging from on February 24, 2022.53 disinformation campaigns, malicious cyber Although budget shortfalls have hampered modactivities, and the manipulation of energy ernization efforts overall, Russia continues to focus markets to support Moscow’s efforts at political on development of such high-end systems as the subversion and economic intimidation. These S-500 surface-to-air missile system. As of March tools and others are intended to coerce, weak2021, the Russian Ministry of Defense was consideren, and divide our Allies and Partners in the ing the most fitting ways to introduce its new S-500 European theater and beyond.58 Prometheus surface-to-air missile system, which can detect targets at up to 1,200 miles and uses a Concerns were heightened and eventually valimissile with a range of approximately 250 miles, dated when Russia used such exercises in the spring “as part of its wider air-defense modernization.” Ac- and fall of 2021 to position forces close to Ukraine’s cording to one report, the S-500 system will enter borders with Russia and Belarus—forces that it ulfull service by 2025.54 timately used to invade Ukraine. Russia’s counterspace and countersatellite capaExercises in the Baltic Sea in January 2022 amid bilities are formidable. According to the U.S. Intelli- heightened tensions between Moscow and the West gence Community: over Russia’s military buildup on the Ukrainian border were meant as a message. Twenty Russian navy Russia continues to train its military space vessels performed “exercises focused on naval and elements and field new antisatellite weapons anti-aircraft defence.”59 Right before the exercises to disrupt and degrade U.S. and allied space occurred, the U.S. announced that it might send excapabilities, and it is developing, testing, and tra troops to NATO’s eastern flank.60 It is possible fielding an array of nondestructive and dethat Moscow used this announcement as its reason structive counterspace weapons—including for initiating the exercises. jamming and cyberspace capabilities, directed Russia’s snap exercises are conducted with little energy weapons, on-orbit capabilities, and or no warning and often involve thousands of troops ground-based ASAT capabilities—to target U.S. and pieces of equipment.61 In April 2021, for exam55 and allied satellites. ple, between 150,000 and 300,000 Russian troops massed at the Ukrainian border and in Crimea to In November 2021, Russia conducted an anti-sat- conduct snap exercises that also involved approxellite missile test that reportedly “endangered the imately 35,000 combat vehicles, 900 aircraft, and crew aboard the International Space Station (ISS)” 190 navy ships.62 In February 2022, just before Mosbecause it created more than 1,500 pieces of track- cow’s second invasion of Ukraine, Russia and Belarable orbital debris and “hundreds of thousands of us held joint snap exercises reportedly with 30,000 pieces of smaller orbital debris.”56 In September combat troops and special operation forces, fighter 226 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength jets, Iskander dual-capable missiles, and S-400 air defense systems.63 Threats to the Homeland Russia is the only state adversary in the Europe region that possesses the capability to threaten the U.S. homeland with both conventional and nonconventional means. Although there does not currently appear to be a strong likelihood that Russia will use its nuclear capabilities against the United States directly, Putin “casts the war [in Ukraine] as an inevitable confrontation with the United States, which he accuses of threatening Russia by meddling in its backyard and enlarging the NATO military alliance,” and CIA Director William Burns has said that “none of us can take lightly the threat posed by a potential resort to tactical nuclear weapons or low-yield nuclear weapons” in Ukraine.64 Russia’s most recent National Security Strategy does not mention NATO directly, but it does assert that the U.S. is planning to deploy medium-range and short-range missiles in Europe—a possibility that NATO firmly denies. The same document also clearly states that Russia will use every means at its disposal to achieve its strategic goals. Among its “basic concepts” is “ensuring national security—the implementation by public authorities in cooperation with civil society institutions and organizations of political, legal, military, socio-economic, informational, organizational and other measures aimed at countering threats to national security.”65 Russia’s nuclear arsenal and strike capability The most recent Russian military doctrine, which remains an enduring, existential threat to the Putin signed in December 2014, specifically emphaUnited States, democracy, and our peaceful Alsizes the threat allegedly posed by NATO and global lies and Partners. A central concern is Russia’s strike systems.66 non-strategic nuclear weapons stockpile and Strategic Nuclear Threat. Russia possesses the Kremlin’s potential to use these weapons in the largest arsenal of nuclear weapons (including crisis or conflict. short-range nuclear weapons) among the nuclear powers.67 It is one of the few nations with the capaRussia pursues malign activities, including milibility to destroy many targets in the U.S. homeland tary aggression, aimed at undermining democraand in U.S.-allied nations as well as the capability to cy, the rules-based international order, and has a threaten and prevent free access to the commons willingness to use force to achieve its aims. Rusby other nations. sia pursues these activities despite widespread Russia has both intercontinental-range and international condemnation and economic short-range ballistic missiles and a varied arsenal sanctions. President Putin leverages coercive and of nuclear weapons that can be delivered by sea, land, aggressive policies to counter Western influence and air. It also is investing significant resources in and threaten peace and stability in Europe.72 modernizing its arsenal and maintaining the skills of its workforce, and “modernization of Russia’s straItem 19 in Putin’s June 2020 executive ortegic nuclear triad is expected to remain a priority” der, “Basic Principles of State Policy of the The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 227 under the new state armament program.68 Modern weapons and equipment allegedly now constitute 89 percent of Russia’s nuclear triad.69 Russia currently relies on its nuclear arsenal to ensure its invincibility against any enemy, intimidate European powers, and deter counters to its predatory behavior in its “near abroad,” primarily in Ukraine, where it uses the threat of nuclear attack to deter other countries from supporting Ukraine’s defense, but also in the Baltic States.70 This arsenal serves both as a deterrent to large-scale attack and as a protective umbrella under which Russia can modernize its conventional forces at a deliberate pace, but Russia also needs a modern and flexible military to fight local wars such as those against Georgia in 2008 and the renewed offensive against Ukraine that began in 2022. Under Russian military doctrine, the use of nuclear weapons in conventional local and regional wars would be de-escalatory because it would cause an enemy to concede defeat. In April 2022, for example, “Russia's Foreign Minister said…that if the U.S. and Ukraine's other Western allies continue to arm the country as it battles Moscow’s invading forces, the risk of the war escalating into a nuclear conflict ‘should not be underestimated.’”71 General Wolters discussed the risks presented by Russia’s possible use of tactical nuclear weapons in his 2022 EUCOM posture statement: Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence,” outlines four “conditions specifying the possibility of nuclear weapons use by the Russian Federation.” They include: fully deployed the SSC-8 cruise missile in violation of the INF Treaty early in 2017 and has deployed battalions with the missile at the Kapustin Yar missile test site in southern Russia; at Kamyshlov near the border with Kazakhstan; in Shuya east of Moscow; The “arrival of reliable data on a launch of and in Mozdok in occupied North Ossetia.77 U.S. ofballistic missiles attacking the territory of the ficials consider the banned SSC-8 cruise missiles to Russian Federation and/or its allies”; be fully operational.78 In December 2018, in response to Russian vioThe “use of nuclear weapons or other types lations, the U.S. declared Russia to be in material of weapons of mass destruction by an adverbreach of the INF Treaty, a position with which sary against the Russian Federation and/or NATO allies were in agreement.79 The U.S. providits allies”; ed its six-month notice of withdrawal from the INF treaty on February 2, 2019, and officially withdrew An “attack by [an] adversary against critical from the treaty on August 2.80 governmental or military sites of the Russian Russia’s sizable nuclear arsenal remains the only Federation, disruption of which would underthreat to the existence of the U.S. homeland emamine nuclear forces response actions”; and nating from Europe and Eurasia. While the potential for use of this arsenal remains low, the fact that “[A]ggression against the Russian Federation Moscow continues to threaten Europe with nuclear with the use of conventional weapons when the attack demonstrates that this substantial nuclear very existence of the state is in jeopardy.”73 capability will continue to play a central strategic role in shaping both Russian military and political Russia’s reliance on nuclear weapons is based thinking and the level of Russia’s aggressive behavior partly on their small cost relative to the cost of con- with respect to other countries. ventional weapons, especially in terms of their effect, and on Russia’s inability to attract sufficient num- Threat of Regional War bers of high-quality servicemembers. In other words, Many U.S. allies regard Russia as a genuine threat. Russia sees its nuclear weapons as a way to offset the At times, this threat is of a military nature, as seen lower quantity and quality of its conventional forces. in Russia’s war against Ukraine. At other times, it inJust as it is doing to deter Western support for volves less conventional tactics such as cyberattacks, Ukraine, Moscow has repeatedly threatened U.S. al- exploitation of Russia’s status as a source of energy, lies in Europe with nuclear deployments and even and propaganda. Today, as in the days of Imperial preemptive nuclear strikes.74 The Russians justify Russia, Moscow uses both the pen and the sword to their aggressive behavior by pointing to deploy- exert its influence. Organizations like the Collective ments of U.S. missile defense systems in Europe. In Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Eurthe past, these systems were not scaled or postured asian Economic Union (EEU), for example, embody to mitigate Russia’s advantage in ballistic missiles Russia’s attempt to bind regional capitals to Moscow and nuclear weapons to any significant degree, through a series of agreements and treaties. but Pentagon officials have said that laser-armed Russia also uses espionage in ways that are damStrykers are set to arrive by September 2022 and aging to U.S. interests. For example: that new Eastern European batteries and sea-based interceptors are set to arrive by 2023.75 In October 2019, the U.S. released and deported Russia continues to violate the Intermedito Russia Maria Butina, a convicted Russian ate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which operative who had infiltrated American conbans the testing, production, and possession of inservative political groups to interfere with the termediate-range missiles.76 Russia first violated the 2016 presidential election.81 treaty in 2008 and then systematically escalated its violations, moving from testing to producing to deIn February 2022, the U.S. expelled 12 officials ploying the prohibited missile into the field. Russia from Russia’s mission to the United Nations. l l l l l l 228 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength MAP 9 Russian Interference Zones UKRAINE RUSSIA KAZAKHSTAN Transnistria MOLDOVA Donbas ROMANIA Abkhazia and South Ossetia Crimea Black Sea Caspian Sea BULGARIA GEORGIA ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN NagornoKarabakh GREECE TURKEY IRAN Transnistria 1992 Nagorno-Karabakh 1994 Abkhazia and South Ossetia 2008 Crimea 2014 Donbas 2014 Ukraine 2022 1990 Transnistria. Russia has stationed troops in Transnistria since 1992 when a cease-fire ended the Moldovan civil war. Nagorno-Karabakh. In September 2020, major fighting broke out in the Nagorno–Karabakh region, which Armenia had been occupying since 1994. The fighting ended in November 2020 when Armenia and 1995 2000 2005 Azerbaijan signed a Russian-brokered cease-fire. Russian peacekeeping troops remain in Nagorno–Karabakh for now. Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russian troops have been stationed in both Abkhazia and South Ossetia since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia and the subsequent five-day war. 2010 2015 2020 Ukraine. In February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Early on, Russian forces attempted to capture Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv but failed. Russia maintains control of Crimea and parts of Donbas while fighting continues across Eastern Ukraine with a large contingent of Russia’s army engaged in the conflict. SOURCE: Heritage Foundation research. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military A heritage.org 229 According to the U.S. Mission to the U.N., the officials had “abused their privileges of residency in the U.S. by engaging in espionage activities that are adverse to our national security.”82 In 2019, the European External Action Service, diplomatic service of the European Union (EU), estimated that 200 Russian spies were operating in Brussels, which is the headquarters of NATO.83 In March 2022, Brussels expelled 21 Russian diplomats for “alleged threats and posing threats to security.”84 According to one report, Russian spies are becoming harder to track because they infiltrate companies, schools, and even the government.85 In addition, the expulsion of Russian spies is not a permanent solution for Western nations because “Russia tends to send back new spies to replace the ones who have left.”86 On March 4, 2018, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian GRU colonel who was convicted in 2006 of selling secrets to the United Kingdom and freed in a spy swap between the U.S. and Russia in 2010, and his daughter Yulia were poisoned with Novichok nerve agent by Russian security services in Salisbury, U.K. Hundreds of residents could have been contaminated, including a police officer who was exposed to the nerve agent after responding.87 It took a year and the work of about 190 U.K. Army and Royal Air Force personnel, supported by “specialist contractors,” to complete the physical cleanup of Salisbury.88 U.S. intelligence officials have reportedly linked Russia to the deaths of 14 people in the U.K. alone, many of them Russians who ran afoul of the Kremlin.89 Russian intelligence operatives are reportedly mapping U.S. telecommunications infrastructure around the United States, focusing especially on fiber-optic cables.90 l l In March 2022, U.S. intelligence analysts concluded that Russian military spy hackers were responsible for a multifaceted cyberattack on satellite broadband service, administered by U.S.-based Viasat, in Ukraine and Europe at the onset of Russia’s renewed offensive in Ukraine.91 In March 2017, the U.S. charged four people, including two Russian intelligence officials, with directing hacks of user data involving Yahoo and Google accounts.92 230 l Undersea cables in the United States are also at risk of being tapped for valuable intelligence. Fourteen Russian sailors who died aboard a submarine that caught fire in July 2019 were suspected of attempting to tap information flowing from American undersea cables.93 Russia has also used its relations with friendly nations—especially Nicaragua—for espionage purposes. In April 2017, Nicaragua began using a Russian-provided satellite station at Managua that, even though the Nicaraguan government denies it is intended for spying, is of concern to the U.S.94 In November 2017, the Russian-built “counter-drug” center at Las Colinas opened, its future purpose being to support “Russian security engagement with the entire region.”95 According to a Foreign Policy Research Institute report, “Aside from the center, Russian forces have participated in joint raids and operations against drug trafficking [in Nicaragua], capturing as many as 41 presumed traffickers in one particular operation” since 2017.96 Moscow also has an agreement with Nicaragua, signed in 2015, that “facilitate[s] Russian access to the ports of Corinto and Bluefields.”97 Pressure on Central and Eastern Europe. Moscow poses a security challenge to members of NATO that border Russia. Until recently, a conventional Russian attack against a NATO member was thought unlikely, but Russia’s assault on Ukraine and its threatening of NATO members that are supporting Ukraine raise the specter of a larger conflict involving NATO. Russia continues to use cyberattacks, espionage, its significant share of the European energy market, and propaganda to sow discord among NATO member states and undermine the alliance. The Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service’s International Security and Estonia 2019 report states clearly that “[t]he only serious threat to regional security, including the existence and sovereignty of Estonia and other Baltic Sea states, emanates from Russia. It involves not only asymmetrical, covert or political subversion, but also a potential military threat.”98 After decades of Russian domination, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe factor Russia into their military planning and foreign policy formulation in a way that is simply unimaginable in many Western European countries and North America. Estonia and Latvia have sizable ethnic Russian populations, and there is concern that Russia might 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength exploit this as a pretext for aggression—a view that is not without merit in view of Moscow’s irredentist rhetoric and Russia’s use of this technique to invade Ukraine in 2014 and 2022. According to Lithuania’s National Threat Assessment 2022: Russia is and will remain the greatest and potentially existential threat to Lithuania and other countries of the region. By threatening to invade Ukraine and spark a conflict in Europe, Russia seeks to force the West to acknowledge its right to determine political choices of other independent states to decide on the ways how to ensure national and regional security. Moscow is also taking advantage of instability generated by [Belarusian dictator Alexander] Lukashenka and together with Beijing further challenging the West…. In language that still applies today, Lithuania’s National Threat Assessment 2019 states that Russia “exploits democratic freedoms and rights for its subversive activity” and “actually promotes its aggressive foreign policy” while “pretending to develop cultural relations” in Lithuania.100 Latvian authorities describe the means used by Russia to claim that it is defending the rights of citizens or Russian “compatriots” in similar terms. “[O]ne of the priorities of Russian propaganda,” for example, “has been promoting the ‘correct’ interpretation of historical events [including the Second World War] in line with the interests of the Kremlin.” Other means include “spread[ing] lies at [the] international level about the Latvian government’s policies, which are allegedly aimed at restricting Russian-speakers’ rights,” as well as “a series of The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 231 Moscow attempts to persuade the country's population that the West is to blame for the economic and social problems and society’s discontent with the regime; however, it is clearly an outcome of ineffective political system and poor management of national resources and priorities. Therefore, the regime employs increasingly aggressive tactics in fighting against the perceived internal and external opponents, escalates military threats to neighbouring states and the West thus seeking to allegedly prevent threats to Russia.99 measures to attract new leaders for the ‘compatriot’ policy” and “expanded…efforts to consolidate young people who could potentially become the next promoters of the Kremlin’s worldview in Latvia.” The principal “directions of Russia’s ‘compatriot’ policy [are] consolidation of the Russian diaspora abroad, protection of the rights of ‘compatriots’, support for ‘compatriot’ youth organisations, [and] the protection of the Russian language and ‘ethnocultural identity.’”101 In March 2017, General Curtis Scaparrotti, then Commander, U.S. European Command, and NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe, testified that Russian propaganda and disinformation should be viewed as an extension of Russia’s military capabilities: “The Russians see this as part of that spectrum of warfare, it’s their asymmetric approach.”102 In 2020, for example, “Russian -sponsored actors released a forged letter online where Polish Brigadier General Ryszard Parafianowicz appeared to criticize openly the American presence in his country during the US-led exercise Defender-Europe 20.”103 Today, “[t]he threat of influence no longer exists only during deployment but also in garrison because of ‘the collapsed nature of communication…and…porous boundaries between war and everyday life,’ which means geography is no longer enough to act as a defense.”104 Russia also has sought to use disinformation to undermine NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in the Baltics. A disinformation campaign nicknamed “ghostwriter,” for example, has been ongoing since 2017. Russian hackers often have leveraged “website compromises or spoofed email accounts to disseminate fabricated content.”105 In one case in 2019, a fake message published on the Polish War Studies Academy website, purportedly from the organization’s commander, called for troops “to fight against ‘the American occupation.’”106 In 2020, hackers falsified an interview transcript, claiming that Lieutenant General Christopher Cavoli, then Commander of U.S. Army Europe, was criticizing the Baltic states’ militaries.107 U.S. troops stationed in Poland for NATO’s eFP have been the target of similar Russian disinformation campaigns.108 A fabricated interview with General Cavoli that was published online was meant to undermine NATO’s reputation among the public.109 One report summarized that “Russia’s state propaganda channels RT and Sputnik remain very keen to exploit to the maximum any incidents involving eFP personnel, and to repeat the Kremlin’s anti-NATO and anti-eFP narrative.”110 In particular, more recent Russian propaganda has focused on portraying eFP as an “occupying force.”111 In February 2022, the Baltics and Poland together urged the largest social media companies to restrict Russian disinformation about the war in Ukraine from “spreading across [their] platforms.” The Baltic states also banned a number of Russian and Belarusian channels that allegedly were disseminating propaganda to justify Moscow’s war.112 Russia has also demonstrated a willingness to use military force to change the borders of modern Europe. When Kremlin-backed Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych failed to sign an Association Agreement with the EU in 2013, months of street demonstrations led to his ouster early in 2014. Russia responded by sending troops, aided by pro-Russian local militia, to occupy the Crimean Peninsula under the pretext of “protecting Russian people.” This led to Russia’s eventual annexation of Crimea, the first such forcible annexation of territory in Europe since the Second World War.113 Then, in February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine a second time, presumably with the goal of bringing the entire nation under Putin’s control. At the time this book was being prepared, Russia occupied one-fifth of Ukraine, an area that includes most of Ukraine’s industrial sector, its port cities on the Black Sea, and the major transport corridors for grain exports. It is likely that Russia will not relinquish by negotiation what it has taken by force, preferring instead to formalize ownership of the area it controls by simply annexing it. Russia’s annexation of Crimea effectively cut Ukraine’s coastline in half, and Russia has claimed rights to underwater resources off the Crimean Peninsula.114 In May 2018, Russia inaugurated the first portion of a $7.5 billion, 11.8-mile bridge connecting Russia with Kerch in occupied Crimea.115 The effect on Ukraine’s regional economic interests can be seen in the fact that 30 percent of the cargo ships that served Mariupol could not clear the span.116 In December 2019, Russia completed a new rail bridge over the Kerch Strait that the EU condemned as “yet another step towards a forced integration of the illegally annexed peninsula.”117 Russia has deployed 30,000 troops to Crimea and has embarked on a major program to build housing, 232 restore airfields, and install new radars there.118 The Monolit-B radar system, for instance, has a passive range of 450 kilometers, and its deployment “provides the Russian military with an excellent real-time picture of the positions of foreign surface vessels operating in the Black Sea.”119 In addition, “Russian equipment there includes 40 main battle tanks, 680 armored personnel carriers and 174 artillery systems of various kinds” along with 113 combat aircraft.120 These numbers may well be different now given Russia’s renewed war in Ukraine and the losses of Russian personnel and equipment from Ukrainian defensive actions.121 Control of Crimea has allowed Russia to use the Black Sea as a platform to launch and support naval operations along the Ukrainian coastline as part of the renewed offensive against Ukraine.122 Russia also has been using the naval base at Sevastopol for operations in the Eastern Mediterranean, but Turkey’s closure of the Bosporus Strait to military traffic in response to Russia’s war against Ukraine has ended this option, at least temporarily.123 Before Turkey closed the Strait, the Black Sea fleet had received six Kilo diesel submarines and three Admiral Grigorovich–class frigates equipped with Kalibr-NK long-range cruise missiles.124 Russia was also planning to add 10 Gorshkov-class frigates and 14 Steregushchiy-class corvettes to its Black Sea fleet.125 Kalibrs have a range of at least 2,500 kilometers, placing cities from Rome to Vilnius within range of Black Sea–based cruise missiles.126 In April 2022, in a significant operational and symbolic loss for Russia, Ukrainian forces sank Russia’s Moskva guided missile cruiser, which had been the flagship of its Black Sea Fleet.127 Russia has deployed five S-400 air defense systems with a potential range of approximately 250 miles to Crimea.128 Russia’s new S-350 air defense systems also could be deployed to Crimea, but that is somewhat unlikely.129 In addition, “local capabilities [in Crimea] have been strengthened by the Pantsir-S1 (SA-22 Greyhound) short-to-mediumrange surface-to-air missile (SAM) and anti-aircraft artillery weapons system, which particularly complements the S-400.”130 Russia also deploys the Bastion P coastal defenses armed with the P-800 Oniks anti-ship cruise missile, which “has a range of up to 300 kilometers and travels at nearly Mach 2.5, making it extraordinarily difficult to defeat with kinetic means.”131 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength In Moldova, Russia supports the breakaway enclave of Transnistria, where yet another frozen conflict festers to Moscow’s liking. According to the Congressional Research Service: Russia stations about 1,500 soldiers in Transnistria, a few hundred of which Moldova accepts as peacekeepers. In 2017, Moldova’s Constitutional Court ruled that Russia’s non-peacekeeping troop presence was unconstitutional. In 2018, the U.N. General Assembly passed a resolution calling on Russia to withdraw its troops from Moldova “unconditionally and without further delay.” Russia continues to occupy 12 percent of Moldova’s territory. On January 22, 2019, in an effort to enhance its control of the breakaway region, Russia opened an office in Moscow for the Official Representation of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic in the Russian Federation.133 In February 2022, a few weeks before Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine, Russian armed forces staged military drills in Transnistria. The exercises followed a Ukrainian warning that “Russian special services could be preparing ‘false flag provocations’ against Russian troops stationed in [Transnistria] to justify a broader invasion of Ukraine.”134 Concerns that Russian troops stationed in Transnistria could be mobilized for the war in Ukraine persist.135 Russia’s permanent stationing of Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad in 2018 occurred a year to the day after NATO’s eFP deployed to Lithuania.136 Russia reportedly has deployed tactical nuclear weapons, the S-400 air defense system, and P-800 anti-ship cruise missiles to Kaliningrad.137 Additionally, Russia established a new tank regiment, comprised of approximately 93 tanks, after 2018.138 According to The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 233 A conflict resolution process operates in a “5+2” format under the chairpersonship of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), with the OSCE, Russia, and Ukraine as mediators and the EU and the United States as observers. The EU also supports conflict management through the EU Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine, which seeks to help the two countries combat transborder crime, facilitate trade, and resolve the conflict over Transnistria.132 the IISS, the majority of Russian air force pilot graduates in 2019 were sent to Kaliningrad “to improve staffing” in the air force units located there.139 Russia also has outfitted a missile brigade in Luga, Russia, just 74 miles from the Estonian city of Narva, with Iskander missiles.140 It also has deployed Iskanders to the Southern Military District at Mozdok near Georgia, and Russian military officials have reportedly asked manufacturers to increase the Iskander missiles’ range and improve their accuracy.141 In addition, Russia has been firing Iskanders with “mystery munitions,” described as “decoys meant to trick air-defense radars and heat-seeking missiles,” at targets in Ukraine.142 Nor is Russia deploying missiles only in Europe. In September 2019, Russia announced its plans to deploy additional missile systems on Paramushir and Matua, two islands in the northern portion of the Kuril Island chain claimed by Japan.143 In December 2020, Russia announced the deployment of S-300V4 air defense missile systems on Iturup.144 In December 2021, Russia deployed Bastion coastal defense missile systems to Matua.145 In March 2022, Russia conducted military drills on the Kuril Islands that involved more than 3,000 troops and hundreds of pieces of army equipment.146 Russia represents a real and potentially existential threat to NATO member countries in Eastern and Central Europe. In addition to its aggression in Georgia and Ukraine, Russia has threatened countries that provide support to Ukraine. It also has threatened Finland and Sweden for moving to join NATO. Given this pattern of aggressive behavior, the possibility of a conventional attack against a NATO member cannot be discounted. In all likelihood, however, Russia will continue to use nonlinear means in an effort to pressure and undermine the NATO alliance and any non-NATO country that opposes Moscow’s political objectives. Militarization of the High North. Russia has a long history in the Arctic and, as an Arctic nation, has interests there. However, Russia’s ongoing militarization of the region, coupled with its bellicose behavior toward its neighbors, makes the Arctic a security concern. Because nationalism is on the rise in Russia, Vladimir Putin’s Arctic strategy is popular among the population. For Putin, the Arctic is an area that allows Russia to flex its muscles without incurring any significant geopolitical risk. Russia is also eager to promote its economic interests in the region. Half of the world’s Arctic territory and half of the Arctic region’s population are located in Russia. It is well known that the Arctic is home to large stockpiles of proven but unexploited oil and gas reserves. Most of these reserves are thought to be located in Russia. In particular, Russia hopes that the Northern Sea Route (NSR) will become one of the world’s most important shipping lanes. Russia has invested heavily in the Arctic region, opening a series of Arctic bases and investing in cold-weather equipment, coastal defense systems, underground storage facilities, and specialized training. According to one report, “[t]he Kremlin’s dominance due to its unique topography and overwhelming military presence has made it impregnable in the Arctic.”147 Additionally, “Russian hardware in the High North area includes bombers and MiG31BM jets, and new radar systems close to the coast of Alaska.”148 Russia also has staged a series of statement activities in the Arctic. In 2007, Artur Chilingarov, then a member of the Russian Duma, led a submarine expedition to the North Pole and planted a Russian flag on the seabed. Later, he declared: “The Arctic is Russian.”149 In July 2017, Russia released a new naval doctrine citing the alleged “ambition of a range of states, and foremost the United States of America and its allies, to dominate the high seas, including in the Arctic, and to press for overwhelming superiority of their naval forces.”150 In May 2017, Russia announced that its buildup of the Northern Fleet’s nuclear capacity is intended “to phase ‘NATO out of [the] Arctic.’”151 In a March 2021 statement exercise, three Russian ballistic missile submarines punched through the Arctic ice near the North Pole.152 In June 2022, Russia withdrew from a nuclear safety program in the Arctic region, raising concerns in the West “about a new period of heightened nuclear risks.”153 Russia also has stationed a floating nuclear power plant on the northern coast of Siberia. “If the venture is successful,” according to one account, “it will represent another milestone in Moscow’s efforts to tame the melting Northern Sea Route, which…could become a direct trade route between Europe and Asia.”154 Although the Arctic region has been an area of low conflict among the Arctic powers, NATO should consider the implications of Russia’s recent 234 aggressive military behavior. NATO is a collective security organization that is designed to defend the territorial integrity of its members. Five NATO members (Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and the United States) are Arctic countries, and all five have territory above the Arctic Circle. Two closely allied nations, Finland and Sweden, are awaiting NATO membership and also have Arctic territory. NATO ambassadors signed the necessary Accession Protocols, the first step in ratification of both countries’ membership in the alliance, on July 5, 2022.155 In recent years, the U.S. has begun to pay increased attention to the Arctic theater in Europe. One way it has done this is by maintaining an enhanced presence in Norway. In April 2021, the two nations signed the Supplementary Defense Cooperation Agreement, which in part allows the U.S. to build additional infrastructure at Rygge and Sola air stations in southern Norway as well as Evenes air station and Ramsund naval station above the Arctic Circle.156 Construction at Evenes will support Norwegian and allied maritime patrol aircraft in their monitoring of Russian submarine activity. Because Russia is an Arctic power, its military presence in the region is to be expected, but it should be viewed with some caution because of Russia’s pattern of aggression. In the Arctic, sovereignty equals security. Respecting national sovereignty in the Arctic would ensure that the chances of armed conflict in the region remain low. Since NATO is an intergovernmental alliance of sovereign nation-states built on the consensus of all of its members, it has a role to play in Arctic security. In the words of NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg: Russia’s military build-up is the most serious challenge to stability and Allied security in the High North…. A strong, firm and predictable Allied presence is the best way to ensure stability and protect our interests. We cannot afford a security vacuum in the High North. It could fuel Russian ambitions, expose NATO, and risk miscalculation and misunderstandings.157 In March 2017, a decree signed by Putin gave the Federal Security Service (FSB), which controls law enforcement along the Northern Sea Route, an Arctic shipping route linking Asia and Europe as well as additional powers to confiscate land “in areas with special objects for land use, and in the 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Recently released photos and video show MiG-31BM Foxhound interceptors in action at Rogachevo Air Base in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago, above the Arctic Circle, an increasingly strategic region that’s home to a resurgent Russian military presence. Russia’s Ministry of Defense provided the imagery as a new rotation of MiG-31BMs arrived at the base, undertaking what the defense ministry describes as “experimental combat duty to protect the state border of the Russian Federation in the Arctic airspace.”171 In March 2019, Mayor General Igor Kozhin, head of the Russian Naval Air Force, claimed that Russia had successfully tested a new airstrip cover that is effective in “temperatures down to minus 30 centigrades.”172 Russia resumed regular fighter jet combat patrols in the Arctic in 2019.173 The Ministry of Defense, for example, announced that in January 2019, two Tu-160 bombers flew for 15 hours in international airspace over the Arctic.174 Over the course of one week in April 2019, Russian fighter and bomber jets flew near the coast of Norway twice. In one instance, two Tu-60 bombers and a MiG-31 flew 13 hours over the Barents, Norwegian, and North Seas. British and Danish jets scrambled to meet the Russian aircraft.175 In 2017, Russia activated a new radar complex on Wrangel Island.176 In 2019, it announced plans to lay a nearly 8,000-mile fiber-optic cable across its Arctic coast, linking military installations along the way from the Kola Peninsula through Vladivostok.177 Construction of the cable began in August 2021 and is due to be completed in 2026.178 In November 2019, Russia announced rocket firings in the Norwegian Sea 20 to 40 nautical miles from the Norwegian coast. The test firings, with little advance notice, were designed to send a message as they took place in an area through which NATO ships were sailing during the Trident Juncture exercise.179 In March 2021, Russia’s Admiral Gorshkov frigate successfully “launched an Oniks cruise missile and hit a coastal target on Novaya Zemlya, about 300 kilometers from launch position.”180 In September 2021, it was reported that “Russia’s Northern Fleet had begun preparations to deploy the air-launched ballistic missile Kh-47M2 Kinzhal on MiG-31K carriers.”181 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 235 border areas.”158 Russia’s Arctic territory is included within this FSB-controlled border zone. The FSB and its subordinate coast guard have added patrol vessels and have built up Arctic bases, including a coast guard base in Murmansk that was opened in December 2018.159 The Russian National Guard, which reports to Putin, is likewise taking on an increased role in the Arctic and is now charged with protecting infrastructure sites that are deemed to be of strategic importance, including a new liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminal at Sabetta that was opened in December 2017.160 In April 2021, shareholders of Novatek, Russia’s second-largest natural gas producer, “approved external financing of $11 billion for the Arctic LNG 2 project, which [was] expected to start production of [LNG] in 2023.”161 However, the imposition of Western sanctions against Russian banks because of the war in Ukraine could force Novatek to halt development of the Arctic LNG 2 terminal.162 In May 2018, Putin issued a presidential degree setting a target of 80 million tons shipped across the NSR by 2024.163 However, in October 2021, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Trutnev announced that Russia “plans to begin year-round shipping via the Northern Sea Route…in 2022 or 2023,”164 even earlier than previously planned. Russia also has been investing in military bases in the Arctic. Its Arctic Trefoil base on Alexandra Land Island, commissioned in 2017, can house 150 soldiers for up to 18 months.165 In addition, old Soviet-era facilities have been reopened. In September 2018, the Northern Fleet announced construction plans for a new military complex to house a 100-soldier garrison and anti-aircraft units at Tiksi. In January 2019, Russian authorities claimed that the base was 95 percent completed,166 But in March 2020, Russia appeared to be “significantly behind in its plans for Tiksi.”167 In 2018, Russia also opened an Arctic airfield at Nagurskoye that is equipped with a 2,500-meter landing strip and a fleet of MiG-31 or Su-34 Russian fighters.168 The landing strip “can handle all types of aircraft, including nuclear-capable strategic bombers.”169 Air power in the Arctic is increasingly important to Russia, which has 14 operational airfields in the region along with 16 deep-water ports, “a new command, and roughly 50 icebreakers…some of which are nuclear powered.”170 In February 2021, it was reported that: Russia’s ultimate goal is encapsulated in a June in the region mean that the posture of players will 2019 study published by the Royal Institute of In- continue to evolve. It is clear that Russia intends to ternational Affairs: exert a dominant influence. According to a U.S. Department of State official: Since the mid-2010s, the Kremlin has deployed substantive force and capabilities along the [The U.S. has] concerns about Russia’s milcoast of its northern border in the AZRF [Arctic itary buildup in the Arctic. Its presence has Zone of the Russian Federation]. Parts of the grown dramatically in recent years with the armed forces are now Arctic-capable, and have establishments of new Arctic commands, new developed concepts of operations tailored to Arctic brigades, refurbished airfields and other that environment. With the creation of OSK infrastructure, deep water ports, new miliSever [Joint Strategic Command North] in 2013, tary bases along its Arctic coastline, an effort the Russian armed forces have been slowly to establish air defense and coastal missile reshaping their Arctic command structure. The systems, early warning radars, and a variety of Arctic forces are primarily focused on air and other things along the Arctic coastline. We’ve naval operations, with the aim of creating an inseen an enhanced ops [operations] tempo of tegrated combined-arms force for the region.182 the Russian military in the Arctic, including last October one of the largest Russian military For a few years, Russia was developing three new exercises in the Arctic since the end of the Cold nuclear icebreakers, and in May 2019, it launched War. So there is some genuine and legitimate its third and final Arktika.183 The Arktika, currently concern there on the part of the United States the world’s largest and most powerful nuclear iceand our allies and partners about that behavior breaker, sailed straight to the North Pole in October in the Arctic.193 184 2020. In January 2022, the Arktika completed its first sail across the eastern part of the NSR.185 That Destabilization in the South Caucasus. The same month, Russia’s newest nuclear-powered ice- South Caucasus sits at a crucial geographical and breaker, the Sibir, the second of Project 22220, ar- cultural crossroads and has been strategically imrived at its home port of Murmansk.186 portant, both militarily and economically, for centuRussia’s Northern Fleet is also building newly ries. Although the countries in the region (Armenia, refitted submarines, including a newly convert- Georgia, and Azerbaijan) are not part of NATO and ed Belgorod nuclear-powered submarine that was therefore do not receive a security guarantee from launched in April 2019.187 The Belgorod is expected the United States, they have participated to varying to carry six Poseidon drones, also known as nuclear degrees in NATO and U.S.-led operations. This is estorpedoes, and will carry out “a series of special mis- pecially true of Georgia, which aspires to join NATO. sions.”188 The submarine will have a smaller miniRussia views the South Caucasus as part of its sub that will potentially be capable of tampering natural sphere of influence and stands ready to exwith or destroying undersea telecommunications ert its influence by force if necessary. In August 2008, cables.189 According to Russian media reports, the Russia invaded Georgia, coming as close as 15 miles Belgorod “will be engaged in studying the bottom of to the capital city of Tbilisi. A decade later, several the Russian Arctic shelf, searching for minerals at thousand Russian troops occupied the two Georgian great depths, and also laying underwater communi- regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. cations.”190 Two similar submarines, the Khabarovsk Russia has sought to deepen its relationship with and Ulyanovsk, which will also carry Poseidon the two occupied regions. In 2015, it signed so-called drones, are scheduled to be commissioned in 2024 integration treaties with South Ossetia and Abkhaand 2025, respectively.191 In addition, the Northern zia that, among other things, call for a coordinated Fleet received 13 new ships in 2021, adding to the foreign policy, creation of a common security and “more than four dozen already in service.”192 defense space, and implementation of a streamlined Russia continues to develop and increase its mil- process for Abkhazians and South Ossetians to reitary capabilities in the Arctic region. The likelihood ceive Russian citizenship.194 The Georgian Foreign of armed conflict remains low, but physical changes Ministry criticized the treaties as a step toward 236 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength Nagorno–Karabakh region and seven surrounding districts. A cease-fire agreement was signed in 1994, and the conflict has been described as frozen since then. In 2020, major fighting broke out along the front lines. After six weeks of fighting, Azerbaijan liberated its internationally recognized territory, “which had been under Armenian occupation since the early 1990s.”205 The conflict ended on November 9, 2020, when Armenia and Azerbaijan signed a Russian-brokered cease-fire agreement.206 As part of the nine-point cease-fire plan, nearly 2,000 Russian peacekeeping soldiers were deployed to certain parts of Nagorno– Karabakh that are populated largely by ethnic Armenians. In May 2021, tensions rose again in the region but for a different reason—the demarcation of the Armenian–Azerbaijani border.207 The Nagorno–Karabakh conflict offers another opportunity for Russia to exert malign influence and consolidate power in the region. Russia “has long been Azerbaijan’s main arms supplier” but “also provides military equipment to Armenia.” Additionally: In conjunction with controlling the negotiation process on the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict over Karabakh, Moscow exploits its role as a major supplier of weapons to Azerbaijan in order to maintain its influence over Baku. In this realm, Russia plays a unique role between Azerbaijan and Armenia. As a main arms supplier of both, Moscow is also the main power broker between the two South Caucasus rivals.208 “annexation of Georgia’s occupied territories,”195 both of which are still internationally recognized as part of Georgia. In January 2018, Russia ratified an agreement with the de facto leaders of South Ossetia to create a joint military force—an agreement that the U.S. condemned.196 South Ossetia’s former leader, Anatoli Bibilov, had planned to hold a referendum on whether the region should join Russia on July 17, 2022, but his successor, Alan Gagloev, has cancelled the plebiscite as “premature.”197 Russia’s “creeping annexation” of Georgia has left towns split in two and families separated by military occupation and the imposition of an internal border (known as “borderization”).198 In May 2020, the U.S. embassy in Tbilisi reported that Russian-led security forces were continuing to erect unauthorized fences and reinforcing existing illegal “borderization” efforts near a number of Georgian villages.199 Moscow continues to exploit ethnic divisions and tensions in the South Caucasus to advance pro-Russian policies that are often at odds with America’s or NATO’s goals in the region, but Russia’s influence is not restricted to soft power. In the South Caucasus, the coin of the realm is military might. It is a dangerous neighborhood surrounded by instability and insecurity that is reflected in terrorism, religious fanaticism, centuries-old sectarian divides, and competition for natural resources. Russia maintains a sizable military presence in Armenia based on an agreement that gives Moscow access to bases in that country at least until 2044.200 The bulk of Russia’s forces, consisting of 3,500 soldiers, dozens of fighter planes and attack helicopters, 74 T-72 tanks, and an S-300 air defense system, are based around the 102nd Military Base.201 Russia and Armenia have also signed a Combined Regional Air Defense System agreement. Despite the election of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in 2018 following the so-called Velvet Revolution, Armenia’s cozy relationship with Moscow remains unchanged.202 Armenian troops even deployed alongside Russian troops in Syria to the dismay of U.S. policymakers.203 Another source of regional instability is the Nagorno–Karabakh conflict, which began in 1988 when Armenia made territorial claims to Azerbaijan’s Nagorno–Karabakh Autonomous Oblast.204 By 1992, Armenian forces and Armenian-backed militias had occupied 20 percent of Azerbaijan, including the As noted by Eurasia expert Eduard Abrahamyan, “for years, Moscow has periodically sought to use the local authorities in Karabakh as a proxy tool of coercive diplomacy against both Baku and Yerevan.”209 The South Caucasus might seem distant to many American policymakers, but the spillover effect of ongoing conflict in the region can have a direct impact both on U.S. interests and on the security of America’s partners, as well as on Turkey and other countries that depend on oil and gas transiting the region. Russia views the South Caucasus as a vital theater and uses a multitude of tools that include military aggression, economic pressure, and the stoking of ethnic tensions to exert influence and control, usually to promote outcomes that are at odds with U.S. interests. The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 237 Increased Activity in the Mediterranean. Russia has had a military presence in Syria for decades, but in September 2015, it became the decisive actor in Syria’s ongoing civil war, having saved Bashar al-Assad from being overthrown and having strengthened his hand militarily, thus enabling government forces to retake territory lost during the war. Although conflicting strategic interests cause the relationship between Assad and Putin to be strained at times, Assad still needs Russian military support to take back Idlib province, a goal that he and Putin probably share.210 Russia’s Hmeymim Air Base is located close to Idlib, making it vulnerable to attacks from rebel fighters and terrorist groups, and Moscow instinctively desires to protect its assets. Assad’s only goal is to restore sovereignty over all of Syria; Russia generally is more focused on eliminating terrorism in the region and must manage its relationship with Turkey. In January 2017, Russia signed an agreement with the Assad regime to “expand the Tartus naval facility, Russia’s only naval foothold in the Mediterranean, and grant Russian warships access to Syrian waters and ports…. The agreement will last for 49 years and could be prolonged further.”211 According to a May 2020 report, Russia is reinforcing its naval group in the Mediterranean Sea with warships and submarines armed with Kalibr cruise missiles.212 In May 2021, the Voice of America reported that Russia is expanding its navy base at Tartus and “planning to construct a floating dock to boost the port’s ship repair facilities.”213 The agreement with Syria also includes upgrades to the Hmeymim air base at Latakia, including repairs to a second runway.214 Russia is extending one of its two runways by 1,000 feet, which would “allow the base to support more regular deployments of larger and more heavily-laden aircraft.”215 Russia deployed the S-400 anti-aircraft missile system to Hmeymim in late 2015.216 It also has deployed the Pantsir S1 system. “The two systems working in tandem provide a ‘layered defense,’” according to one account, “with the S-400 providing long-ranged protection against bombers, fighter jets, and ballistic missiles, and the Pantsir providing medium-ranged protection against cruise missiles, low-flying strike aircraft, and drones.”217 Russia currently operates out of Hmeymim air base on a 40-year agreement and continues to entrench its position there, as demonstrated by its recent building of reinforced 238 concrete aircraft shelters.218 In August 2020, Syria agreed to give Russia additional land and coastal waters to expand its Hmeymim air base.219 According to Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, former Commander, U.S. Army Europe, Russia has used its intervention in Syria as a “live-fire training opportunity.”220 The IISS similarly reports that Russia has used Syria as “a test bed for the development of joint operations and new weapons and tactics.”221 In fact, Russia has tested hundreds of pieces of new equipment in Syria. In December 2018: Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov detailed to local media…the various new weapons systems [that] have been introduced to the conflict. These included the Pantsir S1 anti-aircraft and Iskander-M ballistic missile systems on the ground, Tupolev Tu-160 supersonic strategic bombers, Tu-22M3 supersonic bombers and Tu-95 propeller-driven bombers, as well as Mikoyan MiG-29K fighters and Ka-52K Katran helicopters in the air.222 Overall, Russia reportedly sold $28 billion worth of weaponry to 45 countries, including Syria, between 2016 and 2020.223 Russian pilots have occasionally acted dangerously in the skies over Syria. In May 2017, for example, a Russian fighter jet intercepted a U.S. KC-10 tanker, performing a barrel roll over the top of the KC-10.224 That same month, Russia stated that U.S. and allied aircraft would be banned from flying over large areas of Syria because of a deal agreed to by Russia, Iran, and Turkey. The U.S. responded that the deal does not “preclude anyone from going after terrorists wherever they may be in Syria.”225 The U.S. and Russia have a deconfliction hotline to avoid midair collisions and incidents, but incidents have occurred on the ground as well as in the air. In November 2018, Ambassador James Jeffrey, U.S. Special Representative for Syria Engagement, told news media that “American and Russian forces have clashed a dozen times in Syria—sometimes with exchanges of fire.”226 In February 2022, U.S. F-16 fighter jets and other coalition aircraft escorted three Russian aircraft in eastern Syria when the Russians flew into coalition-restricted airspace.227 In October 2018, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi signed a strategic cooperation treaty with Russia.228 In November 2018, Russia sought to 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength based on religious and ethnic differences remains an ongoing possibility. These tensions are exacerbated by sluggish economies, high unemployment, and political corruption. Russia’s interests in the Western Balkans are at odds with the ongoing desire of the U.S. and its European allies to encourage closer ties between the region and the transatlantic community. Russia seeks to sever the transatlantic bond forged with the Western Balkans…by sowing instability. Chiefly Russia has sought to inflame preexisting ethnic, historic, and religious tensions. Russian propaganda magnifies this toxic ethnic and religious messaging, fans public disillusionment with the West, as well as institutions inside the Balkan nations, and misinforms the public about Russia’s intentions and interests in the region.242 Senior members of the Russian government have alleged that NATO enlargement in the Balkans is one of the biggest threats to Russia.243 NATO now includes four Balkan countries: Albania and Croatia, both of which became member states in April 2009; Montenegro, which became NATO’s 29th member state in June 2017; and North Macedonia, which became NATO’s 30th member state in March 2020. Russia stands accused of being behind a failed plot to break into Montenegro’s parliament on election day in 2016, assassinate its former prime minister, and install a pro-Russian government. In May 2019, two Russian nationals who were believed to be the masterminds behind the plot were convicted in absentia along with 12 other individuals for organizing and carrying out the failed coup. The presiding trial judge, Suzan Mugosa, said on May 9 that [Eduard] Shishmakov and [Vladimir] Popov “pursued a joint decision to make intentional attempts to contribute significantly to the carrying out of the planned criminal actions with the intention to seriously threaten the citizens of Montenegro, to attack the lives and bodies of others, and to seriously threaten and damage Montenegro's basic constitutional, political, and social structures in order to stop Montenegro from joining the NATO alliance.”244 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 239 solidify its relations with Egypt, approving a fiveyear agreement for the two countries to use each other’s air bases.229 Russia is a major exporter of arms to Egypt, which agreed to purchase 20 Su-35 fighter jets in 2018 for $2 billion.230 Production of the Su-35 jets began in May 2020.231 In August 2021, Russia and Egypt signed an additional bilateral strategic cooperation treaty.232 In Libya, Russia continues to support Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar with weapons and military advisers.233 According to the U.S. Department of Defense, Russia’s Wagner Group continues to be involved militarily in Libya.234 Despite its ties to Haftar, Russia has also focused on expanding business ties with the Libyan government in Tripoli.235 Russia has stepped up its military operations in the Mediterranean significantly, often harassing U.S. and allied vessels involved in operations against the Islamic State. In April 2020, for example, a Russian Su-35 jet intercepted a U.S. Navy aircraft flying over the Mediterranean Sea. It was the second time in four days that “Russian pilots [had] made unsafe maneuvers while intercepting US aircraft.”236 The Russian jet had taken off from Hmeymim air base in Syria. In April 2022, “three P-8A maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft ‘experienced unprofessional intercepts by Russian aircraft’ while ‘flying in international airspace over the Mediterranean Sea.’”237 From April–August 2017, the U.S. along with British, Dutch, and Spanish allies tracked the Krasnodar, a Kilo-class submarine, as it sailed from the Baltic Sea to a Russian base in occupied Crimea. The submarine stopped twice in the eastern Mediterranean to launch cruise missiles into Syria and conducted drills in the Baltic Sea and off the coast of Libya.238 In February 2020, General Wolters revealed that Russian submarines are becoming more active and harder for the United States to track.239 On February 24, 2022, the day Russia launched its second invasion of Ukraine, two Russian submarines were seen in the eastern Mediterranean.240 In March 2022, the Russian Navy allegedly “deployed an Akula-class nuclear submarine in the Mediterranean.”241 Russia’s position in Syria, including its expanded area-access/area-denial capabilities and increased warship and submarine presence, underscores the growing importance of the Mediterranean theater in ensuring Europe’s security. The Balkans. Security has improved dramatically in the Balkans since the 1990s, but violence After Russia annexed Crimea, the Montenegrin government backed European sanctions against Moscow and even implemented its own sanctions. Nevertheless, Russia has significant economic influence in Montenegro and in 2015 sought unsuccessfully to gain access to Montenegrin ports for the Russian navy to refuel and perform maintenance. Russia was the largest investor in Montenegro until October 2020 when it was surpassed by China.245 In March 2022, the Montenegrin government joined European sanctions on Russia, “without specifying what they were,” after Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine.246 In April 2022, Montenegro’s government suspended broadcasting by Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik in coordination with EU sanctions on Russia.247 North Macedonia’s accession to NATO was similarly targeted by Russia, which had warned the nation against joining the alliance and sought to derail the Prespa agreement that paved the way for membership by settling long-standing Greek objections to Macedonia’s name.248 In 2018, after North Macedonia was invited to join NATO, Russia’s ambassador to the EU stated that “there are errors that have consequences.”249 In July 2018, Greece expelled two Russian diplomats and banned entry by two Russian nationals because of their efforts to undermine the name agreement; Russian actions in Macedonia included disinformation surrounding the vote, websites and social media posts opposing the Prespa agreement, and payments to protestors as well as politicians and organizations that opposed the agreement.250 Serbia in particular has long served as Russia’s foothold in the Balkans. Russia’s influence in the Balkans centers on Serbia, a fellow religiously orthodox nation with whom it enjoys a close economic, political, and military relationship. Serbia and Russia have an agreement in place allowing Russian soldiers to be based at Niš airport in Serbia. The two countries signed a 15-year military cooperation agreement in 2013 that includes sharing of intelligence, officer exchanges, and joint military exercises. In October [2017], Russia gave Serbia six MiG-29 fighters (which while free, will require Serbia to spend $235 million to have them overhauled). Additionally, Russia plans to supply Serbia with helicopters, T-72 tanks, 240 armored vehicles, and potentially even surfaceto-air missile systems.251 The so-called Russian–Serbian Humanitarian Center at Niš is “widely believed to be a Russian spy base” and is located “only 58 miles from NATO’s Kosovo Force mission based in Pristina.”252 In February 2020, Serbia purchased the Pantsir S1 air-defense system from Russia despite objections and potential sanctions from the United States.253 Russia has used its cultural ties to increase its role in Serbia, positioning itself as the defender of orthodoxy and investing funds in the refurbishing of orthodox churches. It also has helped to establish more than 100 pro-Russian non-governmental organizations and media outlets in Macedonia.254 Serbia and Russia have signed a strategic partnership agreement that is focused on economic issues. Russia’s inward investment is focused on the transport and energy sectors. Except for those in the Commonwealth of Independent States, Serbia is the only country in Europe that has a free trade deal with Russia. In January 2019, Serbia and Russia signed 26 agreements relating to energy, railway construction, and strategic education cooperation.255 Further proof of Belgrade’s loyalty to Moscow is seen in Serbia’s unwillingness or inability to “take a firm stand against Russia’s war on Ukraine.”256 In a January 2019 state visit to Serbia, Vladimir Putin expressed a desire for a free trade agreement between Serbia and the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union. An agreement between the two countries was signed in October 2019 “following veiled warnings from the European Union.”257 Russia also has held out the possibility of $1.4 billion in infrastructure aid to Serbia aimed at building the TurkStream pipeline and increasing Russia’s energy leverage in the region. In May 2022, Serbia reached a three-year agreement with Russia for natural gas supplies at “the most favorable price in Europe.”258 However, Serbia still participates in military exercises far more often without Russia than with Russia. In 2017, for example, “Serbian forces participated in 2 joint exercises with Russia and Belarus but held 13 exercises with NATO members and 7 with U.S. units.”259 Like Russia, Serbia is a member of NATO’s Partnership for Peace program. Additionally, Serbia has partnered with the State of Ohio in the U.S. National Guard’s State Partnership Program since 2006. 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength base to defend the Serbian entity. It has been reported that “[s]ome of its members fought as mercenaries alongside the Kremlin’s proxy separatists in Ukraine.”267 Veterans organizations in Russia and Republika Srpska have developed close ties.268 Russia has cultivated strong ties with the security forces of Republika Srpska. Russian police take part in exchanges with the security forces, and Russian intelligence officers reportedly teach at the police academy and local university. On April 4, 2018, the Republika Srpska authorities opened a new $4 million training center “at the site of a former army barracks in Zaluzani, outside Banja Luka.” The site serves as the headquarters for “anti-terrorist units, logistics units, and a department to combat organized crime.”269 Russia also has continued to oppose the recognition of Kosovo as an independent sovereign country270 and has condemned Kosovo’s creation of its own army. Moscow does not want Kosovo to be seen as a successful nation pointed toward the West. Rather, it seeks to derail Kosovo’s efforts to integrate into the West, often by exploiting the Serbian minority’s grievances. In the most jarring example, a train traveling from Belgrade to Mitrovica, a heavily Serb town in Kosovo, in January 2017 was stopped at the Kosovar border. The Russian-made train was “painted in the colors of the Serbian flag and featured pictures of churches, monasteries, and medieval towns, as well as the words ‘Kosovo is Serbian’ in 21 languages.”271 The U.S. has invested heavily in the Balkans since the end of the Cold War. Tens of thousands of U.S. servicemembers have served in the Balkans, and the U.S. has spent billions of dollars in aid there, all in the hope of creating a secure and prosperous region that eventually will be part of the transatlantic community. The foremost external threat to the Balkans is Russia. Russia’s interests in the Balkans are at odds with the U.S. goal of encouraging the region to progress toward the transatlantic community. Russia seeks to sever the transatlantic bond forged with the Western Balkans by sowing instability and increasing its economic, political, and military footprint in the region. Threats to the Commons Other than cyberspace and (to some extent) airspace, the commons are relatively secure in the The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 241 Russia is also active in Bosnia and Herzegovina— specifically, the ethnically Serb Republika Srpska, one of two substate entities inside Bosnia and Herzegovina that emerged from that country’s civil war in the 1990s. Moscow knows that exploiting internal ethnic and religious divisions among the country’s Bosniak, Croat, and Serb populations is the easiest way to prevent Bosnia and Herzegovina from entering the transatlantic community. Republika Srpska’s current unofficial leader, Milorad Dodik, has long advocated independence for the region and has enjoyed a very close relationship with the Kremlin. President Željka Cvijanović also claims that Republika Srpska will continue to maintain its partnership with Russia.260 Events in Ukraine, especially the annexation of Crimea, have inspired more separatist rhetoric in Republika Srpska, but Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine allegedly has delayed Republika Srpska’s plans to withdraw from Bosnia and Herzegovina’s state institutions.261 In June 2022, in an interview with the public broadcaster of Republika Srpska, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov declared that Dodik is “a friend of Russia.”262 In many ways, Russia’s relationship with Republika Srpska is akin to its relationship with Georgia’s South Ossetia and Abkhazia occupied regions: more like a relationship with another sovereign state than a relationship with a semiautonomous region inside Bosnia and Herzegovina. When Putin visited Serbia in October 2014, Dodik was treated like a head of state and invited to Belgrade to meet with him. In September 2016, Dodik was treated like a head of state on a visit to Moscow just days before a referendum that chose January 9 as Republika Srpska’s “statehood day,” a date filled with religious and ethnic symbolism for the Serbs.263 In October 2018, just days before elections, Dodik was hosted by Putin as they watched the Russian Grand Prix in a VIP box.264 In December 2021, Dodik again visited Moscow. The Kremlin refrained from announcing this latest meeting ahead of time, but Russian presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov asserted that “this by no means belittle[d] the importance of the meeting.”265 Republika Srpska continues to host its “statehood day” in defiance of a ruling by Bosnia’s federal constitutional court that both the celebration and the referendum establishing it are illegal.266 Russia has reportedly trained a Republika Srpska paramilitary force in Russia at the nearby Niš air European region. Despite Russia’s periodic aggressive maneuvers near U.S. and NATO vessels—and with the significant exception of the Kerch Strait— this remains largely true with respect to the security of and free passage through shipping lanes. The maritime domain is heavily patrolled by the navies and coast guards of NATO and NATO partner countries, and except in remote areas in the Arctic Sea, search and rescue capabilities are readily available. Moreover, maritime-launched terrorism is not a significant problem, and piracy is virtually nonexistent. Sea. In May 2018, 17 Russian fighter jets buzzed the HMS Duncan, which was serving as the flagship of Standing NATO Maritime Group Two (SNMG2), operating in the Black Sea. Commodore Mike Utley, who was leading SNMG2, stated that the ship was “probably the only maritime asset that has seen a raid of that magnitude in the last 25 years,” and then-British Defense Minister Gavin Williamson described the pilots’ behavior as “brazen Russian hostility.”272 In June 2021, Russian fighter jets repeatedly harassed a Dutch frigate in the Black Sea.273 Russian threats to the maritime theater also include activity near undersea fiber-optic cables. In July 2019, a Russian submarine reportedly was trying to tap information flowing through undersea cables near Russia’s northern shore in the Barents Sea. The cables “carry 95 percent of daily worldwide communications” in addition to “financial transactions worth over $10 trillion a day.”274 Thus, any disruption would cause a catastrophic reduction in the flow of capital. The Yantar, a mother ship to two Russian mini submersibles, is often seen near undersea cables, which it is capable of tapping or cutting, and has been observed collecting intelligence near U.S. naval facilities including the submarine base at Kings Bay, Georgia.275 In September 2021, it was caught loitering in the English Channel.276 The Russian spy ship Viktor Leonov was spotted collecting intelligence within 30 miles of Groton, Connecticut, in February 2018 and off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia in December 2019.277 Airspace. Russia has continued its provocative military flights near U.S. and European airspace in recent years. In April 2021, Lieutenant General David Krumm from Joint Base Elmendorf–Richardson, Alaska, revealed that during the previous year, there was a large increase in Russian activity and that the U.S. had intercepted more than 60 Russian aircraft 242 in the “most action the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone—a region spanning 200 nautical miles that reaches past U.S. territory and into international airspace—ha[d] seen since the Soviet Union fell in 1991.”278 In October 2020, F-22 Raptor stealth fighter jets scrambled “to intercept Russian long-range bombers and fighters flying off Alaska’s coast” in “the 14th such incident off Alaska’s coast in 2020.”279 In March and April 2019, the Royal Air Force scrambled fighters twice in five days to intercept Russian bombers flying near U.K. airspace off the Scottish coast while the U.S., Australia, and 11 NATO allies were taking part in the Joint Warrior exercise in Scotland.280 In February 2022, U.S. fighter jets and Norwegian and British military planes intercepted Russian aircraft flying near NATO-allied airspace over the North Atlantic.281 Aggressive Russian flying has occurred near North American airspace as well. In January 2019, two U.S. F-22s and two Canadian CF-18 fighters scrambled when two Russian Tu-160 Blackjack bombers flew into Arctic airspace patrolled by the Royal Canadian Air Force.282 Russian flights have also targeted U.S. ally Japan. In March 2022, Japan scrambled a fighter jet to “warn off a helicopter believed to be Russian” that entered Japanese airspace.283 In May 2022, when the QUAD284 was meeting in Tokyo, Japan again scrambled jets to warn off Russian and Chinese warplanes as they neared Japanese airspace.285 Nor is it only maritime patrol aircraft that fly near Japan; Russian Su-24 attack aircraft, for example, were intercepted in December 2018 and January 2019 incidents.286 Between April 1, 2018, and March 31, 2019, Japan had to scramble jets 343 times to intercept Russian aircraft, although that was 47 times less than had been necessary in the preceding year.287 The main threat from Russian airspace incursions, however, remains near NATO territory in Eastern Europe, specifically in the Black Sea and Baltic regions. In March 2021, NATO fighter jets scrambled 10 times in one day “to shadow Russian bombers and fighters during an unusual peak of flights over the North Atlantic, North Sea, Black Sea and Baltic Sea.”288 In February 2022, near NATO allied airspace over the Baltic Sea, U.S. F-15Es scrambled and intercepted Russian fighter jets. That same day, “Norwegian and British aircraft intercepted Russian aircraft in flying from the Barents [Sea] into the North Sea.”289 In April 2022, around both the Baltic 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength impact is overwhelming and can paralyse all of the enemy state’s power structures.’”294 Russia continues to probe U.S. critical infrastructure. The U.S. Intelligence Community assesses that: Russia is particularly focused on improving its ability to target critical infrastructure, including underwater cables and industrial control systems, in the United States as well as in allied and partner countries, because compromising such infrastructure improves and demonstrates its ability to damage infrastructure during a crisis.295 Russia continued to conduct cyberattacks on government and private entities in 2020 and 2021. In 2020, Russian hackers “reportedly infiltrated several US government agencies,” including the Defense, Treasury, Commerce, State, Energy, and Homeland Security Departments and the National Nuclear Security Administration, as well as private-sector companies like Microsoft and Intel. SolarWinds, the company whose software was compromised, “told the [Securities and Exchange Commission] that up to 18,000 of its customers installed updates that left them vulnerable to hackers.” It was estimated that “it could take months to identify all [the hackers’] victims and remove whatever spyware they installed.”296 In April 2021, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned Russia for the SolarWinds hack. It also sanctioned 32 Russian “entities and individuals” that had carried out “Russian government-directed attempts to influence the 2020 U.S. presidential election, and other acts of disinformation and interference.”297 In May 2021, a Russia-based hacking group known as DarkSide launched a cyberattack against Colonial Pipeline, “the operator of one of the nation’s largest fuel pipelines.”298 The 5,500-mile pipeline, “responsible for carrying fuel from refineries along the Gulf Coast to New Jersey,” was down for six days.299 Colonial Pipeline paid DarkSide $90 million in Bitcoin as a ransom payment, but the Department of Justice was able to recover approximately $2.3 million of that amount a few weeks later.300 In June 2021, REvil, a Russian cybercriminal group, launched a ransomware attack on JBS, “the world’s largest meat processing company.”301 As a result of the cyberattack, JBS was forced to shut down all nine of its U.S. plants for a brief period.302 The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org/Military 243 and Black Seas, NATO fighter jets scrambled multiple times over the span of four days “to track and intercept Russian aircraft near Alliance airspace.”290 There have been several incidents involving Russian military aircraft flying in Europe without using their transponders. In April 2020, two maritime Tu-142 reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare planes flew over the Barents, Norwegian, and North Seas but had switched off their transponders. As a result, two Norwegian F-16s were scrambled to identify the planes.291 In September 2019, a Russian Air Force Sukhoi Su-34 fighter flew over Estonian airspace without filing a flight plan or maintaining radio contact with Estonian air navigation officials because the plane’s transponder had been switched off. This was the second violation of Estonia’s airspace by a Russian aircraft in 2019.292 In August 2019, two Russian Su-27 escort jets flew over the Baltic Sea without a flight plan and without turning on their transponders.293 Russia’s violation of the sovereign airspace of NATO member states is a probing and antagonistic policy that is designed both to test the defense of the alliance and as practice for potential future conflicts. Similarly, Russia’s antagonistic behavior in international waters is a threat to freedom of the seas. Russia’s reckless aerial activity in the region also remains a threat to civilian aircraft flying in European airspace. That the provocative and hazardous behavior of the Russian armed forces or Russian-sponsored groups poses a threat to civilian aircraft in Europe was amply demonstrated by the July 2014 downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17, killing all 283 passengers and 15 crewmembers, over the skies of southeastern Ukraine. Cyberspace. Russian cyber capabilities are sophisticated and active, regularly threatening economic, social, and political targets around the world. Moscow also appears to be increasingly aggressive in its use of digital techniques, often employing only the slightest veneer of deniability in an effort to intimidate targets and openly defy international norms and organizations. Russia clearly believes that these online operations will be essential to its domestic and foreign policy for the foreseeable future. As former Chief of the Russian General Staff General Yuri Baluyevsky has observed, “a victory in information warfare ‘can be much more important than victory in a classical military conflict, because it is bloodless, yet the However, the United States is not Russia’s only target. In February 2020, the U.S. and its key allies accused Russia’s main military intelligence agency, the GRU, of a broad cyberattack against the Republic of Georgia “that disrupted ‘several thousand Georgian government and privately-run websites and interrupted the broadcast of at least two major television stations.’”303 It was hoped that the accusation would help to deter Moscow from intervening in the 2020 presidential election. In February 2022, “[t]he European Union and its Member States, together with its international partners, strongly condemned the malicious cyber activity conducted by the Russian Federation against Ukraine, which targeted the satellite KASAT network, owned by Viasat.”304 The attack “interrupted service for tens of thousands of broadband customers across Europe,” including in Ukraine, and “reportedly disrupted service for thousands of European wind turbines.”305 In addition to official intelligence and military cyber assets, Russia employs allied criminal organizations (so-called patriotic hackers) to help it engage in cyber aggression. Using these hackers gives Russia greater resources and can help to shield its true capabilities. Patriotic hackers also give the Russian government deniability. In June 2017, for example, Putin stated that “[i]f they (hackers) are patriotically-minded, they start to make their own contribution to what they believe is the good fight against those who speak badly about Russia. Is that possible? Theoretically it is possible.”306 Russia’s cyber capabilities are advanced and of key importance in realizing the state’s strategic aims. Russia has used cyberattacks to further the reach and effectiveness of its propaganda and disinformation campaigns, and its ongoing cyberattacks against election processes in the U.S. and European countries are designed to undermine citizens’ belief in the veracity of electoral outcomes and erode support for democratic institutions in the longer term. Russia also has used cyberattacks to target physical infrastructure including electrical grids, air traffic control, and gas distribution systems. Russia’s increasingly bold use of cyber capabilities, coupled with the sophistication of those capabilities and Moscow’s willingness to use them aggressively, presents a serious challenge both to the U.S. and to its interests abroad. 244 Conclusion Overall, the threat to the U.S. homeland originating from Europe remains low, but the threat to America’s interests and allies in the region remains significant, especially given Russia’s war in Ukraine. Although Russia has the military capability to harm and (in the case of its nuclear arsenal) to pose an existential threat to the U.S., it has not conclusively demonstrated the intent to do so. The situation is different with respect to America’s allies in the region. Through NATO, the U.S. is obliged by treaty to come to the aid of the alliance’s European members. Russia continues its efforts to underm