Mossad The Greatest Missions of the Israeli Secret Service ( PDFDrive )

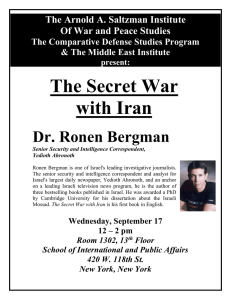

advertisement