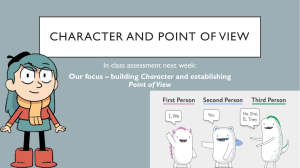

THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS CONTENT How This Guide Can Help You. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 I. Character . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 II. Plot . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 III. Dialogue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 IV. Language. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 V. Subtext . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 VI. Miscellaneous. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 The Checklist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 The Great Big Fat Exercise . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 The End . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17 i THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS HOW THIS GUIDE CAN HELP YOU It isn’t easy to evaluate something you have poured your very heart and soul into. Besides, creative writing is always a pretty personal matter! Nevertheless, this little guide should aid you in taking a clear and honest look at what you have produced. Don’t be the 400-pound (or 200-kilo) guy, stepping onto the freight scale telling himself that “it’s just not calibrated well”. Instead, be the lean guy who steps onto his bathroom scale only to read, “I wish I was like you!” displayed in front of him in crisp, blinking, digitized letters! When you have finished writing, the first thing to do is to pat yourself on the back and treat yourself to a nice lump of sugar, stack of clover, some eggshells and rotten apples or whatever may float your boat: You pulled it off! Next, store your text safely away for a while – it will be so much easier to judge objectively once some time has passed. Just relax and engage in some totally different endeavors like snail-training or jumping out of trash cans in the open street to give people a good scare. Even sleeping on your writings for just one single night makes a huge difference already, for while you are sleeping, your brain is out there in open space busily solving your problems. Now if you put your script aside for one or two full weeks, you will get an even clearer picture! Finally, when you are ready, take this very list and go over it point by point, taking a good, close look at your writing and putting this one question to yourself: Are you truly happy with the result? Be very honest there! The list below should help you to look at your writings from different angles by splitting the happy-question up into various parts. If you are not happy with some aspect of your writing, then what is it that you could do better? Think about it for a moment: Which approach would leave you more satisfied? You have one big advantage on your side, which is that you probably love reading and have, over time, developed a great intuition about storytelling – so just trust it and go along with it! At the very least, take some notes about how you could improve your story; after that, you obviously have two options: Rewriting your piece or letting it go and just incorporating what you have learned into the next one! In any case, you should definitely execute a couple of writing prompts in the area you want to improve. On www. ridethepen.com , you can find the very best writing exercises online and completely for free too, and you will soon have the opportunity to choose from a wide variety of exactly tailored topics. Take advantage! 1 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS If you are having trouble answering the questions on this list, ask for a second opinion of somebody you trust – but make sure it’s somebody who will not sugarcoat their advice and butter you up (sounds like a recipe!) just to protect your feelings. Your Uncle Albert has last read a novel in 1964 and would hate to depress you, so leave him out of the equation! Best are people who know about the value of honest critique and are avid writers themselves, or at least avid fiction readers. As an additional option, if you want to get an experienced, fee-based opinion, www. ridethepen.com will have a review service in place shortly (look out for details under “Products & Services”). The subsequent questions are divided into six sections, just like the categories on the blog. Now Look at Your Story and Answer The Following Questions: I. CHARACTER Examine your MAIN CHARACTERS one by one (for this purpose, consider your main characters the ones without whom you wouldn’t have a story): 2 1. Take a look at everything the character says and does: Does your figure show basic character traits like you would find in a living person? Does he display various characteristics that lend him a threedimensional feeling and fit together in a certain, one-of-a-kind pattern? Each person is unique! 2. Consider anything we learn about your character’s back story: Does your reader feel like there is a background apart from the story to the character? This is about a character’s personal history (upbringing, experiences, etc…) as well as his believe systems (attitudes, values, morals, expectations, etc…) – does it seem like he was there before the story started and will be there after it has ended? 3. Look at any small peculiarities and quirks your character displays: Does your character have little mannerisms that set him apart from the crowd? This is optional and not absolutely necessary, but it adds a little something like spices add to a dish. Be aware though that just like eating only black pepper with oregano on top doesn’t make for a very delicious meal, you shouldn’t overdo it – go overboard and you will have a cartoon character! THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS 4. Pay attention to any behavior that seems to not be completely in line with the characters’ basic traits: Can you detect an unexpected feature in your figure that seems to run completely against what the character stands for, but in its own way still fits in with who she is? You have to be careful that any contradiction makes sense, but this really has the potential to create one hell of a multi-dimensional character! If you need an example, you can probably even come up with one just thinking about your own personality (e.g. a person whose outlook is very materialistic, but who loves donating to charity, because he feels like it gives some meaning to his life). Now examine your MINOR CHARACTERS one by one (for this purpose, your minor characters are the ones without whom you would still have a story): 5. Look at everything the minor character says and does: Does your minor character have at least two or three recognizable basic features and a minimum of background? The more the merrier, but even a little dose will be okay here. How much you need depends on how prominently the character appears in your work and also on the length of your piece. See above for further explanations. 6. Consider any little tick the character displays: Does your minor character have one mannerism or quirk that sets him apart from the masses? Again, this is optional but helps. Don’t put him together completely out of mannerisms though. See above. For ALL CHARACTERS: 7. Put yourself into the shoes of a new reader for a moment: Is your character interesting enough for the audience to really care about? Friend or foe, clerk or freak, it’s all good, as long as inquiring minds want to know. 8. Compare the figures in your story: Are the characters in your story clearly distinguishable? You have a pool of ideas inside of your head – be careful not to draw all of your characters out of the same deep end of that pool! 9. Pay attention to what the characters are saying and how they are saying it: Does the personality of your character fully show through in her speech? What’s moving this person? What’s her temper, what does she respond to? This question might as well stand in the dialogue section. 10. Take into account by which means a figure’s characteristics are introduced: Do you mainly demonstrate your character’s traits instead of just listing them? It’s the old “Show, don’t tell!”. You are not just describing Wendy Wonderhoot as a courageous and animal-loving spirit, no, you get her right in there and show how she saves a little dog off the rails in front of an approaching train. 11. Look at the crabs and prawns that appear in your story: Are any of your shellfish wearing an 18th century masters-of-ceremonies-suit? If yes, make sure the suit got enough sleeve holes for the pincers and legs. Nevermind, that was a joke. 3 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS II. PLOT 12. Pay attention to which event or action leads to which other event or action: Does the plot seem logical? Is it quite comprehensible how this, that and the other thing occurs – or does it feel like it just happens because the author needs it to happen? 13. Look at the entire composition of your plot and if necessary, summarize it on a piece of paper: Does the structure of your plot make sense? This is about narrative threads, point of view, timelines and the like – it’s important it all fits together, in whichever way it’s supposed to. Is the structure rather simple and straightforward, or does it contain many serpentines, subplots, flashbacks, etc… (e.g. say there are a lot of flashbacks to the day before the story takes place; would it be a better strategy to just tell the first day and after that the second day, in chronological order)? 14. Picture yourself as the reader and think about what you would expect next at each turn of the story: Does your plot hold unexpected twists and turns in store? If it doesn’t, your reader might start playing Russian roulette out of sheer boredom by page fifteen! A surprising plot might at first glance seem opposed to a consistent and logical plot, but both aspects can actually complement each other very well. 15. Again, take a look at things from the reader’s perspective: Does your story, at any given time, leave open questions to tickle the reader’s curiosity? It should. Contrary to what most writing guides will tell you, those questions don’t have to be about plot (“What’s gonna happen next?”). They could also be about character (“Why is he so nervous?”), about exploring a condition/ relationship (“Is she his sister, his lover or both?”), or just about the overall atmosphere (“Gosh, that giant rabbit eating planet earth was fun, I wonder what’s in store next!?”). Do you keep your reader’s expectations oscillating at all times? 16. Compare the scenes to each other in regards to tension: Are some parts of the story way more exciting than others? I hope so, because that means you have a rhythm to your arc of suspense and, subsequently, to your story. Does suspense ebb and flow? 17. Evaluate the story scene by scene: Is the plot tight? Is every scene in there to advance the plot or at least to entertain? Or can you find redundant parts, duplications, loops and 4 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS empty pages that add nothing? Please let off any hot air immediately and pay attention to the neon-colored lines on the floor showing you the way to the emergency exits. 18. In the same fashion, look at each scene separately and ask yourself the very same question: Is each scene on its own (within the plot) tight? Can you find superfluous parts of scenes that neither drive the story, nor really entertain, nor add any other core element? Pure vanities, like ballet slippers on a warthog? Remove. 19. Try to anticipate what will happen next in the text: Can you get a notion of future events before they occur? Do events seem inevitable? Ideally, the reader won’t know in advance what’s going to happen, but will in hindsight say to himself: “I should have known!” Just like Uncle Albert after you have wrecked his car. 20. Assess the main turning points of the story: Does the plot bring fresh elements or is it just a cliché as seen a thousand times before? Does it not have more tricks up its sleeve than any given telenovela or does it stand on its own, bringing something original to the table? Then again, if you are actually writing a telenovela, go ahead and make it about Wendy Wonderhoot not being able to decide between the guy she admires and the guy who cares so much about her… III. DIALOGUE 21. Read the dialogue aloud and pay attention: Is your dialogue realistic? Do people really talk that way or does your dialogue sound too ponderous, stilted, restrained, exuberant, cheesy, bloodless, etc…? Does it sound like textbook-talk? 22. Think about the ways emotion flows back and forth in your dialogue: Does your dialogue make sure to follow emotion as opposed to following logic? Is it “illogical” enough? People most often respond in affects, not in logic, so most of your dialogue should not be too straightforward, but instead take twists and turns, circling its topic, bumping into it and wandering way past it. 23. Read your dialogue again: Can you easily distinguish the characters just by the way they are talking? Do your characters all have their own unique ways of expressing themselves? Consider their vocabulary, rhythm of speech and tone of voice. In case of doubt, as if I hadn’t mentioned it before – reading aloud always helps! 5 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS 24. Take a look at the content of your dialogue: Is the dialogue tight? Just like with plot and scenes, don’t leave any superfluous stuff in there! Everything has to serve some purpose at least and several purposes ideally. Make sure to throw out any meaningless platitude and empty cliché (“How are you?” – “Thanks, I’m fine, and you?” – “I’m fine too, thanks!”). This is even more important for screenplays, as time is scarce and movie audiences don’t show the slightest tolerance for any dead air. 25. Look at what the characters do while they are making conversation: Are your characters engaging with their surroundings as they speak? Yes, dialogue is a full-contact sport! This can mean making use of a prop or a setting; it can mean moving around, interacting with other characters on the side or even just a simple change of body posture. The characters don’t have to do that every single time, but it sure adds another dimension, as they are not talking in a vacuum anymore. Whether they are cleaning a stove or fumbling around with a Rubik’s cube – keep them occupied! 26. Ask yourself how much fun it is to read this: Does the dialogue entertain? In the midst of checking for all the rights and wrongs, don’t forget what you have probably, after all, written this for: To keep yourself and anybody reading entertained! Several of the questions about dialogue will be expanded on in depth in the series “The Seven Pillars of Dialogue” on the blog, so watch out for those articles! IV. LANGUAGE 27. Compare the various passages of the text: Does the text decide upon one coherent style? Whether you are employing a very pictorial language or are playing with words, whether your style is very austere or very emotional, you should generally stick with it. 28. Consider how easy it is to read your style: Is the writing as clear as seems fitting? This is what needs to go: Any expression that just sits there to make the passage sound more sophisticated, any pushy adverb, any overcomplicating passive voice. Did you omit any unnecessary subordinate clauses? Tell things as straightforwardly as your style permits! Let simplicity be your first and foremost choice. 29. Try to detect any figures of speech or catchphrases in your writing: Is the 6 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS language free of clichés? This means any language that doesn’t come straight out of yourself, but was handed down to you by common patterns of speech (e.g. she was sleeping like a baby; he had some skeletons in the closet, etc…). While you are sweeping your text, make sure to throw out any cheesy or melodramatic expression as well! 30. Examine the way you are describing things: Do you show the reader how things are and not just tell him by slapping a label on? Does the language use specific, concrete words when illustrating something? Specific language lets the reader enter much deeper into the world of your fiction. It’s not a “tasty dish,” but a “creamy banana sorbet with chocolatedipped cherries on top.” Wanna try? 31. Inspect any metaphor you can detect: Do the metaphors and other figurative language sound right? Common pitfalls include mental images that are not interesting, out of proportion, incongruous or just plain meaningless. 32. Look at the variety in the length of your phrases, length of your words and in punctuation: Does the language have a certain rhythm to it? Or is there just one phrase patched onto the next one with mental superglue to provide information? Take your pick from period, exclamation mark, question mark, colon, comma, hyphen, suspension mark, and semicolon! Rhythm is grace is poetry. V. SUBTEXT 33. Take a look at what you want to express: Is there a basic theme to your story? If you want to write something of quality, this matters. Your “theme” is not some great, mythical thing sitting on a mountaintop that needs to be worshipped; it’s just an angle you are coming from, a feeling your reader might get after reading the story. Does your tale evoke associations? Is there some meat to it? 34. Look at the various components your story is made up of: Do the elements of the story each represent an aspect of the overall theme? Take a close look at all parts of the story: This includes the characters, their looks, their hats, cars or offices; it includes actions and events, which is figure skating and fireworks; any animals or objects; any space the characters are inhabiting, whether it’s opera stages, flying saucers or landscapes; the weather; or any incorporeal meta-structure like ideas, plans, rules or morals; and basically anything else – you name it, it’s already a willing part of the structure! Now does each element play its role, contributing to the basic idea like a little piece of a mosaic? 7 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS 35. Consider any symbols the text employs: Do the symbols fit? That broken jockstrap standing for the hurt of mankind has to go! Remember that anything can be a symbol, from a character’s handbag or profession to a location or weather condition. 36. Note what your characters are saying, phrase by phrase: Is what the characters really mean well hidden under an additional level of conversation? Do the characters just plainly state what they mean, or is the dialogue multilayered? Again, people talk in emotions. Let the real meaning be submerged underneath the obvious (e.g.: A woman says, “What are you doing tonight?” and means, “Ask me out for dinner!”). This plays into the Dialogue section and might as well have been put there. VI. MISCELLANEOUS 37. Consider the perspective of your story: Does the point of view make sense and is it consistent? No matter if you have one or several narrators, and whether the storyteller is a person or a neutral entity – is it the best choice? Does the narrator only know as much as he is supposed to know, and does a neutral narrator refrain from injecting any opinion? 38. Take a look at how the story treats descriptions: Does the text include all five senses when describing something? Seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling and tasting make the text vivid and put the reader right into the front seat. Tickle your reader’s nose, make his eyes pop out, his ears flutter and his tongue roll down like it’s his red, furry-feeling tie! 39. Feel out what’s in the air: Is the atmosphere of each scene as tense/vivid/romantic/cool/ etc... as it should be? Is the spooky house as spooky as you had imagined it? Is the funny mirror maze funny, or does it feel like a sad ladies’ bathroom at a train station? Is there any additional element that could add to the atmosphere? 40. Put yourself into the shoes of a reader who knows nothing about the background of your story: Is the background information introduced unobtrusively? “Unobtrusively” means it’s brought in so naturally, the reader doesn’t even notice it’s brought in (and not in the hejust-said-it-so-I-know-it way). Also, make sure the info is spread out, not clustered. 8 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS 41. Take into account how the story transitions from one section to the next: Are the cuts from scene to scene smooth? Whether they are building on a common element or emphasizing a sharp contrast – bring them into a relation that adds to the story’s rhythm! 42. Compare the scenes of your script: Do the scenes offer a variation in length, setting, depth, pattern, dynamic, format and so on? Variety keeps your piece vibrant and alive. For instance, you could first have a dynamic, action-oriented scene in which your character is running after the mail-man, and then, as soon as he catches up to him, a static dialogue scene, finally to be followed by a short and distressed inner monologue. 43. Observe how powerfully the beginning draws you into the story: Do the very first sentences absorb the reader? It could be about the plot. It could be about the character. It could be about the atmosphere or any curious detail. It could be about a giraffe with a bowtie. Your start should be like a big “Welcome!” to the reader (it could also be a big “Fuck you!”). 44. Take a look at the words on your cover page: Does the title sound intriguing? “Intriguing” means walking the fine line between bloated and featureless, between try-hard and void of any meaning. Ideally, your title has a bit of mystery to it – but never in a forceful way! This is a matter of intuition, probably even more so than most other things in writing. On the next three pages you can find a complete checklist with all of the questions summarized, to print out for quick reference or in case you are short of napkins: 9 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS THE CHECKLIST I. CHARACTER: 1. Does your figure show basic character traits like you would find in a living person? 2. Does your reader feel like there is a background apart from the story to the character? 3. Does your character have little mannerisms that set him apart from the crowd? 4. Can you detect an unexpected feature in your figure that seems to run completely against what the character stands for, but in its own way still fits in with who she is? 5. Does your minor character have at least two or three recognizable basic features and a minimum of background? 6. Does your minor character have one mannerism or quirk that sets him apart from the masses? 7. Is your character interesting enough for the audience to really care about? 8. Are the characters in your story clearly distinguishable? 9. Does the personality of your character fully show through in her speech? 10. Do you mainly demonstrate your character’s traits instead of just listing them? 11. Are any of your shellfish wearing an 18th century masters-of-ceremonies-suit? II. PLOT: 10 12. Does the plot seem logical? 13. Does the structure of your plot make sense? 14. Does your plot hold unexpected twists and turns in store? 15. Does your story, at any given time, leave open questions to tickle the reader’s curiosity? THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS 16. Are some parts of the story way more exciting than others? 17. Is the plot tight? 18. Is each scene on its own (within the plot) tight? 19. Can you get a notion of future events before they occur? 20. Does the plot bring fresh elements or is it just a cliché as seen a thousand times before? III. DIALOGUE: 21. Is your dialogue realistic? 22. Does your dialogue make sure to follow emotion as opposed to following logic? 23. Can you easily distinguish the characters just by the way they are talking? 24. Is the dialogue tight? 25. Are your characters engaging with their surroundings as they speak? 26. Does the dialogue entertain? IV. LANGUAGE: 27. Does the text decide upon one coherent style? 28. Is the writing as clear as seems fitting? 29. Is the language free of clichés? 30. Do you show the reader how things are and not just tell him by slapping a label on? 31. Do the metaphors and other figurative language sound right? 32. Does the language have a certain rhythm to it? V. SUBTEXT: 11 33. Is there a basic theme to your story? 34. Do the elements of the story each represent an aspect of the overall theme? 35. Do the symbols fit? 36. Is what the characters really mean well hidden under an additional level of conversation? THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS VI. MISCELLANEOUS: 12 37. Does the point of view make sense and is it consistent? 38. Does the text include all five senses when describing something? 39. Is the atmosphere of each scene as tense/vivid/romantic/cool/etc... as it should be? 40. Is the background information introduced unobtrusively? 41. Are the cuts from scene to scene smooth? 42. Do the scenes offer a variation in length, setting, depth, pattern, dynamic, format and so on? 43. Do the very first sentences absorb the reader? 44. Does the title sound intriguing? THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS THE GREAT BIG FAT EXERCISE Now let’s get to practicing all of that good stuff. Here, I have a little story for you: Isabella is buying groceries at the supermarket. After paying, she notices she has been carrying a tube of toothpaste in her handbag and has forgotten to put it on the conveyor belt. So far, nobody has noticed. She decides that reporting it now could get her into even more trouble and keeps quiet. At the exit, a guy in a hat approaches her. She suspects it might be the store detective and becomes nervous, but in fact the guy is just hitting on her. At home, Isabella is still anxious about the episode. Her behavior gets her boyfriend Paul upset in turn and they get into an argument. For Isabella’s piece of mind, they decide to take the receipt and return to the supermarket to clear things up. When they talk to the cashier, they find out the toothpaste was in fact on a “2 for 1” promotion: As Isabella had officially bought a second one, she didn’t even steal it in the first place. Scary Toothpaste SHIT TO DO: Now based on the story outline above, try the following six writing prompts. There is one prompt for each section of this booklet. I suggest you really take your time with these exercises and reserve each one for a different day: 13 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS Exercise 1: Characterization ■ Write the story and breathe as much life into the main characters Isabella and Paul as possible! Provide them with some real depth, so your readers feel like they are people they actually know. Lend the two of them several character traits, think about where in their characters these traits could originate from and how they could complement each other. Then pick spots in your scenes to demonstrate (not tell!) these traits to your audience. Change the characters’ names, if it helps you. Forget about the subtleties of storyline, dialogue or anything else – except for where you feel like you need them for your characterization. Dynamics of plot, your style or else – it doesn’t matter! This will help you to concentrate exclusively on the characters. Then, go ahead and post your writing on www.ridethepen.com in the comments section of any article! Exercise 2: Plot ■ For this exercise, I want you to expand and/or remodel the storyline a bit. You could add some characters into the mix (policeman on street, friend on phone, etc…), add some twists and turns, and of course feel free to change or cut out events. While the story as it stands does include a climax, it’s not really a breathtaking tale and the whole plot looks more like a skeleton. So make it more interesting and turn it into something the audience would actually want to read by adding suspense and additional flavors; put some meat onto this skeleton’s ribs! As only plot matters in this exercise, you don’t have to write out the actual story. Just scribble down the storyline in notes, not even coherent phrases are needed. Concentrate on plot, forget about all the fancy stuff like dialogue or language, and if you roughly know the nature of your characters, you will be fine. Just know them like Uncle Albert, whom you have last seen about two years ago. Then post on blog! Exercise 3: Dialogue ■ The outline includes three different dialogues; of course, feel free to add additional ones! Think about what each character wants in his specific dialogue and how he feels – then let emotions take their course! Who needs any plot or language in between dialogues? Just leave them out and concentrate on what people are actually saying. A wise man once told you to disregard what people are speaking and to just pay attention to what they are doing? Today, throw that advice out the window and do it the other way around…! 14 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS Exercise 4: Language ■ Construct the plot like a 3rd grader, butcher the characters and use dialogue like window putty, BUT treat the language caring and affectionate like a baby kitten! You can experiment with this: Which style do you feel like using? Start with a plain, straightforward style, then you might want to try something different, like distorting language or making it extremely dynamic and expressive (or any other pen-handling you wish). The question is: From which angle, through which lens are you describing the world? If you are a beginner, this is a very demanding exercise and mainly there to give you the freedom to explore. Developing a new style within five lines is not possible anyway, so you really can’t go wrong here. Just try something out! After the fact – post it! Exercise 5: Subtext ■ This is not an easy one either, but nobody said you had to be perfect: Pick one single pivotal message for your story! This could be, “The truth is always worth speaking,” or, “You should not fight,” or any other angle you want to present the story’s events from. It’s like shining a spotlight on a certain aspect of the raw story elements I gave you above. Tell your story from that one single angle! Anything else, like characters, plot, dialogue, point of view, style, etc… has to fit into your overall concept. If it doesn’t fit, make it fit! For example, say you chose the general subtext of “The truth is always worth speaking”: Now, you could emphasize your point by letting the cashier at the end of the story state that it frequently happens that people take something with them accidentally, but that this should never ever be a problem as long as they speak out when they notice. You could also let Isabella have a little tortured philosophical self-talk on her way home; you could add a sub-plot in which Paul is also lying to her in an unnecessary way, because this would also accentuate the theme; or you could go as far as making Isabella a notorious liar. Choose a theme, then add any additional twist or layer that will highlight what this story is about! Again, you don’t have to write the actual full text – just put down a couple of notes on how you plan to convey your subtext. Use the full range of tools for getting your message across: Characters, plot, dialogue, style, etc… Like always, feel free to transform the story completely, so it better suits your needs! 15 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS Exercise 6: Miscellaneous ■ As a final exercise, you are going to completely turn around the point of view of the whole story: Tell the tale as Paul is experiencing it! Surely he is occupied by his very own, completely different set of problems and joys while Isabella is out there at the grocery store. Then this little theft issue enters his day – describe the argument from his perspective. What does he feel and think, how does it lead to the decision to return to the shop? Use the first person, really get into his head and keep in mind the limits of what Paul can be aware of. For this purpose though – just as you got comfy! – I want you to write out the whole story! Inject some life into the characters, especially into Paul’s, create realistic and intriguing dialogue, mind your language, and if you feel generous you can even sprinkle the story with some new plot elements! Then, put some sugar on top by giving this one, your very own Paul-story, an intriguing title! Go with a liiiittle bit of mystery and let it sound catchy, but no brain-jerk titles, please. Make it fit. Be imaginative. 16 THE 44 KEY QUESTIONS THE END And finally, by now, after six exercises, I bet you are really sick of that little story of mine… I have to inform you though that the fan shop will have coffee mugs and little magnets with images of toothpaste available soon! At the very end, let me encourage you to practice, seek out feedback, and practice some more. Writing is, as you may have already noticed from reading my blog, above all about relentless exercise! The way you get better is through practicing a ton, accepting setbacks, and getting up to try again. The good ones got good through falling flat on their noses, pulling themselves together, dusting themselves off and keeping on trying; so getting something not right should never be an issue. Perfectionism can be the enemy of your success (just ask me, I feel like I know from creating this blog…). As they say, you either win or you learn! And sometimes you do both. www.ridethepen.com provides you with the perfect platform for practice and feedback, so don’t hesitate to put any of your stuff online in any comments section! We are doing our best every month to bring out kick-ass articles about creative writing in which we cover all sorts of approaches, angles and tricks. I hope this little booklet will do its part in helping you to improve your skills. Good luck with your writing, check back with me on the blog to let me know how it goes – and ride the pen! PS: All rules exist to be broken... 17 IMPRINT: Unless otherwise noted, all content of this e-book © 2014 Alexander Limberg and Ridethepen.com. No part of this e-book may be reprinted, distributed or used without written permission of Ridethepen.com. Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure the completeness and accuracy of information contained in this book, we assume no responsibilities for errors or omissions herein. All Rights reserved. IMAGES: “Speech Bubble” © Gstudio Group/Fotolia.com; “Vintage Letter A” © Barbara Bergman; “Sphynx” © siloto/ Fotolia.com; “On the Road” © Jérôme Motte; all other images © Alexander Limberg