Shared Situational Awareness & Spatial Information Dissertation

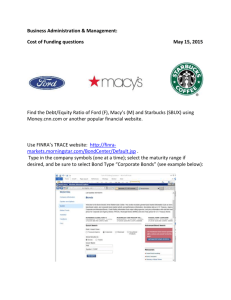

advertisement