Culture-and-Society -An-Introduction-to-Cultural-Studies-PDFDrive-

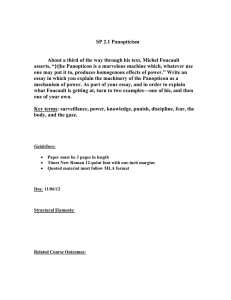

advertisement