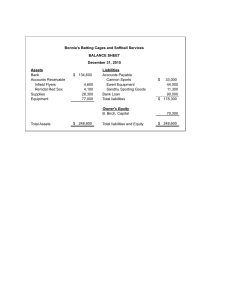

Module 2 Understanding the Balance Sheet Part 1 Learning Objective 1. Describe and construct the balance sheet and understand how it can be used for analysis. (p. 1) In Module 1, we introduced the four financial statements—the balance sheet, the income statement, the cash flow statement, and the statement of stockholders’ equity. In this module and the next, we turn our attention to how the balance sheet and income statement are prepared. Reporting Financial Condition The balance sheet reports on a company’s financial condition and is divided into three components: assets, liabilities, and stockholders’ equity. It provides us with information about the resources available to management and the claims against those resources by creditors and shareholders. At the end of August 2011, Walgreens reports total assets of $27,454 million, total liabilities of $12,607 million, and equity of $14,847 million. Drawing on the accounting equation, Walgreens’ balance sheet is summarized as follows ($ million). Assets = Liabilities + Equity $27,454 = $12,607 + $14,847 LO1 Describe and construct the balance sheet and understand how it can be used for analysis. The balance sheet is prepared at a point in time. It is a snapshot of the financial condition of the company at that instant. For Walgreens, the above balance sheet amounts were reported at the close of business on August 31, 2011. Balance sheet accounts carry over from one period to the next; that is, the ending balance from one period becomes the beginning balance for the next period. Walgreens’ 2011 and 2010 balance sheets are shown in Exhibit 2.1. These balance sheets report the assets and the liabilities and shareholders’ equity amounts as of August 31, the company’s fiscal year-end. Walgreens had $27,454 million in assets at the end of August 31, 2011, with the same amount reported in liabilities and shareholders’ equity. Companies report their audited financial results on a yearly basis.1 Many companies use the calendar year as their fiscal year. Other companies prefer to prepare their yearly report at a time when business activity is at a low level. Walgreens is an example of the latter reporting. Assets An asset is a resource that is expected to provide a company with future economic benefits. When a company incurs a cost to acquire future benefits, we say that cost is capitalized and an asset is recorded. An asset must possess two characteristics to be reported on the balance sheet: 1. It must be owned or controlled by the company. 2. It must possess expected future benefits that can be measured in monetary units. 1 Companies also report quarterly financial statements, and these are reviewed by the independent accountant, but not audited. 1 Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 1 3/13/15 4:42 PM Module 2: Part 1 | Understanding the Balance Sheet The first requirement, that the asset must be owned or controlled by the company, implies that the company has legal title to the asset or has the unrestricted right to use the asset. This requirement presumes that the cost to acquire the asset has been incurred, either by paying cash, by trading other assets, or by assuming an obligation to make future payments. The second requirement indicates that the company expects to receive some future benefit from ownership of the asset. Benefits can be the expected cash receipts from selling the asset or from selling products produced by the asset. Benefits can also refer to the receipt of other noncash assets, such as accounts receivable or the reduction of a liability (e.g. when assets are given up to settle debts). It also requires that a monetary value can be assigned to the asset. Companies acquire assets to yield a return for their shareholders. Assets are expected to produce revenues, either directly (e.g. inventory that is sold) or indirectly (e.g. a manufacturing plant that produces inventories for sale). To create shareholder value, assets must yield income that is in excess of the cost of the funds utilized to acquire the assets. EXHIBIT 2.1 Walgreens’ Balance Sheet Walgreen Co. and Subsidiaries Consolidated Balance Sheets at August 31, 2011 and 2010 ($ millions) Assets used up or converted to cash within one year Assets not used up or converted to cash in one year Liabilities requiring payment within one year Liabilities not requiring payment within one year Current Assets Noncurrent Assets Current Liabilities Noncurrent Liabilities Shareholders’ Equity Assets Cash and cash equivalents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Accounts receivable, net . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Inventories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Other current assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2011 2010 $ 1,556 2,497 8,044 225 $ 1,880 2,450 7,378 214 Total current assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Property and equipment at cost, less accumulated depreciation and amortization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Goodwill . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Other noncurrent assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12,322 11,922 11,526 11,184 2,017 1,589 1,887 1,282 Total noncurrent assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15,132 14,353 Total assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $27,454 $26,275 Liabilities and Shareholders’ Equity Short-term borrowings Trade accounts payable Accrued expenses and other liabilities Income taxes $ 13 4,810 3,075 185 $ 12 4,585 2,763 73 8,083 2,396 343 1,785 7,433 2,389 318 1,735 4,524 — 80 834 (34) 18,877 16 (4,926) 4,442 — 80 684 (87) 16,848 (24) (3,101) Total current liabilities Long-term debt Deferred income taxes Other noncurrent liabilities Total noncurrent liabilities Preferred stock; none issued Common stock Paid-in capital Employee stock loan receivable Retained earnings Accumulated other comprehensive income (loss) Treasury stock, at cost Total shareholders’ equity Total liabilities and shareholders’ equity 14,847 14,400 $27,454 $26,275 Current Assets In the United States, the assets section of a balance sheet is presented in order of liquidity, which refers to the ease of converting noncash assets into cash. The most liquid assets are called current assets. Current assets are assets expected to be converted into cash or used in 2 Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 2 3/13/15 4:42 PM Module 2: Part 1 | Understanding the Balance Sheet operations within the next year, or within the next operating cycle. Some typical examples of current assets include the following accounts, which are listed in order of their liquidity: ■ Cash—currency, bank deposits, certificates of deposit, and other cash equivalents; ■ Marketable securities—short-term investments that can be quickly sold to raise cash; ■ Accounts receivable—amounts due to the company from customers arising from the sale of products or services on credit; ■ Inventory—goods purchased or produced for sale to customers; ■ Prepaid expenses—costs paid in advance for rent, insurance, or other services. FYI Cash equivalents are shortterm, highly liquid investments that mature in three months or less and can be easily converted to cash. The amount of current assets is an important measure of liquidity. Companies require a degree of liquidity to effectively operate on a daily basis. However, current assets are expensive to hold—they must be insured, monitored, financed, and so forth—and they typically generate returns that are less than those from noncurrent assets. As a result, companies seek to maintain just enough current assets to cover liquidity needs, but not so much so as to reduce income unnecessarily. Noncurrent Assets The second section of the asset side of the balance sheet reports noncurrent (long-term) assets. Noncurrent assets include the following asset accounts: ■ ■ ■ Long-term financial investments—investments in debt securities or shares of other firms that management does not intend to sell in the near future; Property, plant, and equipment (PPE)—includes land, factory buildings, warehouses, office buildings, machinery, office equipment, and other items used in the operations of the company; Intangible and other assets—includes patents, trademarks, franchise rights, goodwill, and other items that provide future benefits, but do not possess physical substance. Noncurrent assets are listed after current assets because they are not expected to expire or be converted into cash within one year. Measuring Assets Assets that are intended to be used, such as inventory and property, plant, and equipment, are reported on the balance sheet at their historical cost (with adjustments for depreciation in some cases). Historical cost refers to the original acquisition cost. The use of historical cost to report asset values has the advantage of reliability. Historical costs are reliable because the acquisition cost (the amount of cash paid to purchase the asset) can be objectively determined and accurately measured. The disadvantage of historical costs is that some assets can be significantly undervalued on the balance sheet. For example, the land in Anaheim, California, on which Disneyland was built more than 50 years ago, was purchased for a mere fraction of its current market value. Some assets, such as marketable securities, are reported at current market value or fair value. The market value of these assets can be easily obtained from online price quotes or from reliable sources such as The Wall Street Journal. Reporting certain assets at fair value increases the relevance of the information presented in the balance sheet. Relevance refers to how useful the information is to those who use the financial statements for decision making. For example, marketable securities are intended to be sold for cash when cash is needed by the company to pay its obligations. Therefore, the most relevant value for marketable securities is the amount of cash that the company expects to receive when the securities are sold. Only those asset values that can be accurately measured are reported on the balance sheet. For this reason, some of a company’s most important assets are often not reflected among the reported assets of the company. For example, the well-recognized Walgreens logo does not appear as an asset on the company’s balance sheet. The image of Mickey Mouse and that of the Aflac Duck are also absent from The Walt Disney Company’s and Aflac Incorporated’s balance sheets. Each of these items is referred to as an unrecognized intangible asset. These intangible assets and the Coke FYI Excluded assets often relate to self-developed, knowledgebased assets, like organizational effectiveness and technology. This is one reason that knowledgebased industries are so difficult to analyze. Yet, excluded assets are presumably reflected in company market values. This fact can explain why the firm’s market capitalization (its share price multiplied by the number of shares) is often greater than the book value shown on the balance sheet. 3 Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 3 3/13/15 4:42 PM Module 2: Part 1 | Understanding the Balance Sheet bottle silhouette, the Kleenex name, an excellent management team, or a well-designed supply chain, are measured and reported on the balance sheet only when they are purchased from a third party. As a result, internally created intangible assets, such as the Mickey Mouse image, are not reported on a balance sheet, even though many of these internally created intangible assets are of enormous value. Liabilities and Equity Liabilities and equity represent the sources of capital to the company that are used to finance the acquisition of assets. Liabilities represent the firm’s obligations for borrowed funds from lenders or bond investors, as well as obligations to pay suppliers, employees, tax authorities, and other parties. These obligations can be interest-bearing or non-interest-bearing. Equity represents capital that has been invested by the shareholders, either directly via the purchase of stock, or indirectly in the form of earnings that are reinvested in the business and not paid out as dividends (retained earnings). We discuss liabilities and equity in this section. The liabilities and equity sections of Walgreens’ balance sheets for 2011 and 2010 are reproduced in the lower section of Exhibit 2.1. Walgreens reports $12,607 million of total liabilities and $14,847 million of equity as of its 2011 fiscal year-end. The total of liabilities and equity equals $27,454—the same as the total assets—because the shareholders have the residual claim on the company. A liability is a probable future economic sacrifice resulting from a current or past event. The economic sacrifice can be a future cash payment to a creditor, or it can be an obligation to deliver goods or services to a customer at a future date. A liability must be reported in the balance sheet when each of the following three conditions is met: 1. The future sacrifice is probable. 2. The amount of the obligation is known or can be reasonably estimated. 3. The transaction or event that caused the obligation has occurred. When conditions 1 and 2 are satisfied, but the transaction that caused the obligation has not occurred, the obligation is called an executory contract and no liability is reported. An example of such an obligation is a purchase order. When a company signs an agreement to purchase materials from a supplier, it commits to making a future cash payment of a known amount. However, the obligation to pay for the materials is not considered a liability until the materials are delivered. Therefore, even though the company is contractually obligated to make the cash payment to the supplier, a liability is not recorded on the balance sheet. However, information about purchase commitments and other executory contracts is useful to investors and creditors, and the obligations, if material, should be disclosed in the footnotes to the financial statements. In its annual report, Walgreens reports open inventory purchase orders of $1,736 million at the end of fiscal year 2011. Current Liabilities Liabilities on the balance sheet are listed according to maturity. Obligations that are due within one year or within one operating cycle are called current liabilities. Some examples of common current liabilities include: ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Accounts payable—amounts owed to suppliers for goods and services purchased on credit. Accrued liabilities—obligations for expenses that have been recorded but not yet paid. Examples include accrued compensation payable (wages earned by employees but not yet paid), accrued interest payable (interest on debt that has not been paid), and accrued taxes (taxes due). Short-term borrowings—short-term debt payable to banks or other creditors. Deferred (unearned) revenues—an obligation created when the company accepts payment in advance for goods or services it will deliver in the future. Sometimes also called advances from customers or customer deposits. Current maturities of long-term debt—the current portion of long-term debt that is due to be paid within one year. 4 Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 4 3/13/15 4:42 PM Module 2: Part 1 | Understanding the Balance Sheet Noncurrent Liabilities Noncurrent liabilities are obligations to be paid after one year. Examples of noncurrent liabilities include: ■ ■ Long-term debt—amounts borrowed from creditors that are scheduled to be repaid more than one year in the future. Any portion of long-term debt that is due within one year is reclassified as a current liability called current maturities of long-term debt. Other long-term liabilities—various obligations, such as warranty and deferred compensation liabilities and long-term tax liabilities, that will be satisfied at least a year in the future. Detailed information about a company’s noncurrent liabilities, such as payment schedules, interest rates, and restrictive covenants, are provided in the footnotes to the financial statements. FYI Borrowings are often titled Notes Payable. When a company borrows money it normally signs a promissory note agreeing to pay the money back—hence, the title notes payable. B U SIN ESS IN SIGH T How Much Debt Is Reasonable? In August 2011, Walgreens reports total assets of $27,454 million, liabilities of $12,607 ($8,083 current 1 $4,524 non-current) million, and equity of $14,847 million. This means that Walgreens finances 46% of its assets with borrowed funds and 54% with shareholder investment. Liabilities represent claims for fixed amounts, while shareholders’ equity represents a flexible claim (because shareholders have a residual claim). Companies must monitor their financing sources and amounts because borrowing too much increases risk, and investors must recognize that companies may have substantial obligations (like Walgreens’ inventory purchase commitment) that do not appear on the balance sheet. Stockholders’ Equity Equity reflects capital provided by the owners of the company. It is often referred to as a residual interest. That is, stockholders have a claim on any assets that are not needed to meet the company’s obligations to creditors. The following are examples of items that are typically included in stockholders’ equity: ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Common stock—the capital received from the primary owners of the company. Total common stock is divided into shares. One share of common stock represents the smallest fractional unit of ownership of a company.2 Additional paid-in capital—amounts received from the primary owners in addition to the par value or stated value of the common stock. Treasury stock—the amount paid for its own common stock that the company has reacquired, which reduces contributed capital. Retained earnings—the accumulated earnings that have not been distributed to stockholders as dividends. Accumulated other comprehensive income or loss—accumulated changes in equity that are not reported in the income statement. Contributed Capital Earned Capital The equity section of a balance sheet consists of two basic components: contributed capital and earned capital. Contributed capital is the net funding that a company has received from issuing and reacquiring its equity shares. That is, the funds received from issuing shares less any funds paid to repurchase such shares. In 2011, Walgreens’ equity section reports $14,847 million in equity. Its contributed capital is a negative $4,046 million ($80 million in common stock plus $834 million in [additional] paid-in capital minus $34 million in an employee stock loan receivable and minus $4,926 million in treasury stock). The negative balance indicates that Walgreens has returned more cash to its shareholders (by buying its own stock) than it has received in cash from its shareholder capital contributions. Earned capital is the cumulative net income (and losses) retained by the company (not paid out to shareholders as dividends). Earned capital typically includes retained earnings and accumulated 2 Many companies’ common shares have a par value, but that value has little economic significance. For instance, Walgreens’ shares have a par value of $.078125 per share, while the market price of the stock is about $35 at the time of this writing. In most cases, the sum of common stock (at par) and additional paid-in capital represents the value of stockholders’ contributions to the business in exchange for shares. 5 Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 5 3/13/15 4:42 PM Module 2: Part 1 | Understanding the Balance Sheet other comprehensive income or loss. Walgreens’ earned capital is $18,893 million ($18,877 million in retained earnings plus $16 million in accumulated other comprehensive income). Retained Earnings There is an important relation for retained earnings that reconciles its beginning and ending balances as follows: Beginning retained earnings 1 Net income (or Net loss) Dividends Ending retained earnings FYI This relation is useful to remember, even though there are other items that sometimes impact retained earnings. We revisit this relation after our discussion of the income statement and show how it links the balance sheet and income statement. Equity is a term used to describe owners’ claims on the company. For corporations, the terms shareholders’ equity and stockholders’ equity are also used to describe owners’ claims. We use all three terms interchangeably. Analyzing and Recording Transactions for the Balance Sheet The balance sheet is the foundation of the accounting system. Every event, or transaction, that is recorded in the accounting system must be recorded so that the following accounting equation is maintained: Assets 5 Liabilities 1 Equity We use this fundamental relation to help us assess the financial impact of transactions. This is our “step 1” when we encounter a transaction. Our “steps 2 and 3” are to journalize those financial impacts and then post them to individual accounts to emphasize the linkage from entries to accounts (steps 2 and 3 are explained later in this module). Balance Sheet Balance Sheet Statement of Equity Transaction Statement of Cash Flows Income Statement A N A L Y Z E Balance Sheet Balance Sheet Transaction Cash Asset Noncash Assets = Liabilities J O U R N A L I Z E Income Statement Contrib. Capital = Earned Capital Revenues - Expenses Cash Asset = Net Income = (2) Purchased $950 in supplies with $250 cash and $700 on account 1 (2) 250 Cash Noncash Assets 950 Supplies = = Liabilities Income Statement Contrib. Capital Earned Capital Revenues 700 - Accounts Payable Supplies ( A) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Cash ( A) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Accounts Payable ( L) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - Expenses = Cash Asset Transaction Net Income A N A L Y Z E = J O U R N A L I Z E 950 250 700 (2) Purchased $950 in supplies with $250 cash and $700 on account 1 (2) 250 Cash Noncash Assets 950 Supplies = = Liabilities Income Statement Contrib. Capital Earned Capital Revenues 700 - Expenses - Accounts Payable Supplies ( A) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Cash ( A) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Accounts Payable ( L) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . = Net Income = 950 250 700 Purchased supplies for $950. Terms: $250 down, remainder due in 60 days. Purchased supplies for $950. Terms: $250 down, remainder due in 60 days. P O S T Step 1: Analyze each transaction from source documents Supplies ( A) (2) Accounts Payable ( L) 950 Step 2: Journalize each transaction from the FSET analysis 700 (2) Cash ( A) 250 (2) Step 3: Post journal information to ledger accounts Financial Statement Effects Template To analyze the financial impacts of transactions, we employ the following financial statement effects template (FSET). Balance Sheet Transaction Cash Asset 1 Noncash Assets = = LiabilContrib. 1 1 ities Capital Income Statement Earned Capital Revenues - Expenses = Net Income = 6 Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 6 3/13/15 4:42 PM Module 2: Part 1 | Understanding the Balance Sheet The template accomplishes several things. First and foremost, it captures the transaction that must be recorded in the accounting system. But accounting is not just recording financial data; it is also the reporting of information that is useful to financial statement readers. So, the template also depicts the effects of the transaction on the four financial statements: balance sheet, income statement, statement of stockholders’ equity, and statement of cash flows. For the balance sheet, we differentiate between cash and noncash assets so as to identify the cash effects of transactions. Likewise, equity is separated into the contributed and earned capital components (the latter includes retained earnings as its major element). Finally, income statement effects are separated into revenues, expenses, and net income (the updating of retained earnings is denoted with an arrow line running from net income to earned capital). This template provides a convenient means to represent financial accounting transactions and events in a simple, concise manner for analyzing, journalizing, and posting. The Account An account is a mechanism for accumulating the effects of an organization’s transactions and events. For instance, an account labeled “Merchandise Inventory” allows a retailer’s accounting system to accumulate information about the receipts of inventory from suppliers and the delivery of inventory to customers. Before a transaction is recorded, we first analyze the effect of the transaction on the accounting equation by asking the following questions: ■ ■ What accounts are affected by the transaction? What is the direction and magnitude of each effect? To maintain the equality of the accounting equation, each transaction must affect (at least) two accounts. For example, a transaction might increase assets and increase equity by equal amounts. Another transaction might increase one asset and decrease another asset, while yet another might decrease an asset and decrease a liability. These dual effects are what constitute the double-entry accounting system. The account is a record of increases and decreases for each important asset, liability, equity, revenue, or expense item. The chart of accounts is a listing of the titles (and identification codes) of all accounts for a company.3 Account titles are commonly grouped into five categories: assets, liabilities, equity, revenues, and expenses. The accounts for Natural Beauty Supply, Inc. (introduced below), follow: Assets 110 Cash 120 Accounts Receivable 130 Other Receivables 140 Inventory 150 Prepaid Insurance 160 Security Deposit 170 Fixtures and Equipment 175 Accumulated Depreciation—Fixtures and Equipment liabilities 210 Accounts Payable 220 Interest Payable 230 Wages Payable 240 Taxes Payable 250 Unearned Revenue 260 Notes Payable equity 310 Common Stock 320 Retained Earnings revenues and income 410 Sales Revenue 420 Interest Revenue expenses 510 Cost of Goods Sold 520 Wages Expense 530 Rent Expense 540 Advertising Expense 550 Depreciation Expense—Fixtures and Equipment 560 Insurance Expense 570 Interest Expense 580 Tax Expense 3 Accounting systems at large organizations have much more detail in their account structures than we use here. The account structure’s detail allows management to accumulate information by responsibility center or by product line or by customer. Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 7 7 3/13/15 4:42 PM Module 2: Part 1 | Understanding the Balance Sheet Each transaction entered in the template must maintain the equality of the accounting equation, and the accounts cited must correspond to those in its chart of accounts. Summary Describe and construct the balance sheet and understand how it can be used for analysis. (p. 1) ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ LO1 Assets, which reflect investment activities, are reported (in order of their liquidity) as current assets (expected to be used typically within a year) and long-term (or plant) assets. Assets are reported at their historical cost and not at market values (with few exceptions) and are restricted to those that can be reliably measured. Not all assets are reported on the balance sheet; a company’s intellectual capital, often one of its more valuable assets, is one example. For an asset to be recorded, it must be owned or controlled by the company and carry future economic benefits. Liabilities and equity are the sources of company financing; ordered by maturity dates. 8 Copyright 2014 Cambridge Business Publishers 02_FABC_ch02.indd 8 3/13/15 4:42 PM