Гудманян А.Г., Крилова Т.В. Граматика англійської та української мов: конспект лекцій .– К.: НАУ, 2009. – 64 с. (Англійською мовою)

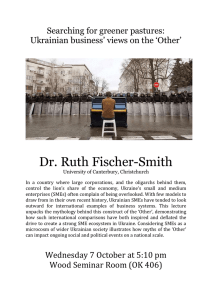

advertisement