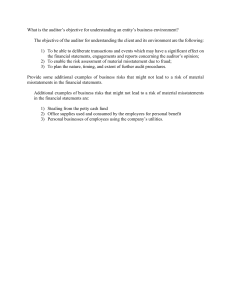

PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 2: A Guide for Financial Managers

advertisement