A New Body for a New Tango: The Ergonomics of Bandoneon Performance in Astor

Piazzolla's Music

Author(s): GABRIELA MAURIÑO

Source: The Galpin Society Journal , April 2009, Vol. 62 (April 2009), pp. 263-271

Published by: Galpin Society

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20753637

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Galpin Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Galpin Society Journal

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GABRIELA M AURINO

A New Body for a New Tango:

The Ergonomics of Bandoneon Performance

in Astor Piazzolla's Music

The bandoneon is the signature instrument

during his early years, including Jazz and Art music.

of the Tango, a genre that originated more As a result, his music incorporated richer tonal

than a century ago and is still danced and harmonies, more rhythmic variety and improv

performed around the world in different styles isation techniques, compared with Traditional

and varieties. Since its origin, Tango has been Tango. For its instrumentation, he incorporated the

transformed choreographically and musically electric guitar and created a quintet (bandoneon,

by different artists who submitted it to different violin, piano, double bass and electric guitar) which

processes of hybridisation and fusion with different came to be the standard instrumentation for New

genres. One of the most important musicians who Tango groups. His innovations also included a change

contributed to the transformation of Tango was in the performance practice of his instrument, the

bandoneon player Astor Piazzolla, who is credited bandoneon, which is the focus of this article.

with creating the New Tango.

The term 'New Tango' presupposes the existence

of an 'Old (or Traditional) Tango' but the boundary

the terms suggested is sometimes artificial and does

BANDONEON CHARACTERISTICS

The bandoneon belongs to the category of

intermittent aerophones, specified as free reed

not represent the fact that both styles nurtured instruments with hand-operated bellows (Dunkel

and influenced each other. However, that should be

discussed on another occasion and this article will

use both terms in order to differentiate between

1993:19). The development of free reed technology in

the early 1800s created possibilities for the invention

of new musical instruments. In 1835 Carl Friedrich

some of the performance practices it describes. The Uhlig invented a bi-sonorous square headed bellow

term Traditional Tango has been widely used by instrument he named Konzertinal, which did not use

scholars (Taylor 1976; Asian 1990; Archetti 1999; predefined chords like Demian's accordion (Vienna,

Collier 2000; Kutnovsky 2002; Azzi 2002; Cannata 1829) but single notes. It was eventually called

2005) to describe the Tango developed in the Rio de

bandoneon, a name that derives from the Akkordion

la Plata area (Buenos Aires and Montevideo) from of Heinrich Band, a promoter of the instrument

its origin around the 1880s until 1955 when Astor who modified and extended the original keyboard

Piazzolla created the term New Tango (Nuevo Tango layout (Mensing 2004). The instrument was created

to replace the organ in religious celebrations in

the open air or in small churches but because of

in Spanish) to describe his music and to differentiate

it from Traditional Tango.1

Born in Argentina but brought up in New York,

its technical difficulties it did not became popular

Piazzolla was exposed to different music styles until it was taken to Buenos Aires around the 1890s.

1 The Spanish adjective nuevo (or nueva, in feminine) is also found in other Latin American genres that label the

renovation of traditional genres, such as nueva trova or nueva canci?n. However, there is no connection between

Nuevo Tango and these genres or the political contexts with which they are associated.

263

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

264

The Galpin Society Journal LXII (2009)

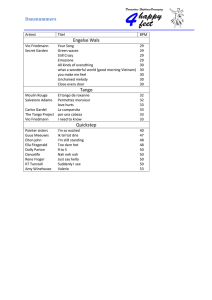

Figure 1. Rheinische Tonlage Bandoneon. All photographs by the author.

Eventually it became the signature timbre of Tango.2 tones) also called Rheinische Tonlage (see Figure 1),

with zonal distribution of buttons and bi-sonoric

The design was gradually modified and the number

of tones increased to 142 (some models have 152), operation. The most sought bandoneons are those

with 5 button rows for the left hand and 6 rows for

made by the Alfred Arnold factory, manufactured

before World War II under two brand names: Dohle

the right (Mensing 2004).

A ('Double A, meaning Alfred Arnold) and Premier.

Regarding the layout of the buttons in each box, the

Throughout his career, Astor Piazzolla played Doble

bandoneons can be:

A models. The reeds of these bandoneons are made of

a) Piano fingered: the disposition of the buttons

zinc which provides them with a great sound quality.

During the war, the manufacture of bandoneons

follow that of the piano, normally 44 buttons for

each hand, distributed in 4 rows.

stopped but it resumed after the war until the end

b) Zonal: the distribution of the buttons does notof the 1940s when Hohner bought the licence. The

conform to a scalar sequence of notes, though

other important brands are ELA (made by Ernest

some adjacent buttons form chords.

Louis Arnold, father of Alfred before leaving the

company to his son) and Germania (made by

On the basis of their bellows operation, there are two Hohner). Both these brands were usually made with

aluminium reeds. In addition, some German models

types of bandoneons:

a) Unisonoric: the same pitch sounds when opening

were imported to Argentina and renamed with the

importer brands like Casa America or Mariani.

and closing the bellows.

b) Bi-sonoric (also erroneously called diatonic): in The bandoneons used in Tango can be of various

colours: black, brown or dark red. The mother of

most voices (buttons) the pitch is different when

played opening or closing the bellows.

pearl that decorates the body of the instrument also

varies: nacarado (mother of pearl decorations in

all the bandoneon), medio-nacarado (more than 3

Most of the bandoneons that are used in Tango came

to Argentina from Germany between the 1920s

designs in mother of pearl but not in the full body),

and the 1950s in quantities estimated at between

?4 nac?r (only 3 decorations) and liso (plain with no

30-40,000.3 The models of bandoneons that are

decorations).

played there are called Teclado Argentino 142-144 The bandoneon register extends almost to five

(Argentine keyboard with 142 or 144 number of

octaves. The right hand plays the high register

2 Exactly when and how the bandoneon reached Argentina is not documented. Some Tango historians such as

Horacio Ferrer believe that it was introduced by immigrants who arrived in Argentina in great numbers at that time.

Tango scholars also believe that the bandoneon's darker sound (compared to the accordion used in the first Tango

ensembles) made it the perfect instrument to express the melancholy of the immigrants, a theme that permeated the

original Tango music.

3 Julian Hasse, personal communication (July 2008).

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

265

Maurino ? Bandoneon

vibra

vibra

vibra

Example 1. Piazzolla, Astor (1975) Suite Troileana. Transcription by Ricardo Fiorio.

Retrieved from http://www. inorg. chem.ethz. ch/tango/band/fiorio/escritura.html

(notated in treble clef) and the left hand the low

register (notated in bass clef). Two notes are linked

to each button, one sounding when the bellows are

compressed and the other sounding when they are

extended. (Dunkel 1993:14) This bi-sonor function

demands a complicated technique: the performer

has to learn four sets of fingerings, two for each

hand, one for closing and the other for opening the

bellows.

There are three basic body positions for Tango

bandoneon performance. The first two have been the

standard practice of bandoneonists since the 1940s;

Astor Piazzolla introduced the third in the 1960s.

a) Classical position: the player is seated with the

instrument resting on the thighs and parallel to

the floor. This allows good instrument control,

favouring a legato sound.

The use of the bandoneon for polyphonic music

rather than as a melodic instrument produced a

complex distribution of the buttons following a zonal

rather than linear structure in order to facilitate

the building of chords (Mensing 2004). However,

the small distances between the buttons make it

possible to play the highest notes simultaneously

with low ones (Dunkel 1993:33) allowing the

production of chords of widely separated notes

which recalls the sound of an organ. Piazzolla used

this feature frequently as it is evident in Example 1

from Bandoneon, the first movement of his Suite

Troileana (1975). The music is for the left hand; the

versatility of the bandoneon is used to build chords

of widely separated pitches.

ERGONOMICS OF PERFORMANCE

Each instrument affects the body shape of its

performer through the physical demands that emerge

from the interface between body and instrument,

which Clarke & Davidson call the ergonomics

of performance (1998:89). The nature of the

bandoneon and its technical and sonority demands

generate particular bodily responses. Its weight is

approximately 5.4 kg, necessitating some degree

of physical strength from the performer because

the weight is distributed unevenly at the extremes.

The greater the volume of air in the bellows, the

greater the force to open or close it (when closed,

the bellows measure approximately 13 cm and when

fully extended about 65 cm. which means a five-fold

increase in their air volume).4

Figure 2. Position (a) - Classical.

4 This information has been extracted from Dunkel (1993:21) and is based on an Alfred Arnold bandoneon

manufactured in Carsfeld, Germany c.1930s. Astor Piazzolla himself played Alfred Arnold models and wrote a piece

called Tristezas de un Doble A (Sadness of a Double A).

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

266 The Galpin Society Journal LXII (2009)

b) One leg support: the player is seated with the

central section of the bellows resting on either the

right or the left thigh. This allows more volume

and stressed accents. For example, the use of a

special articulation called golpe (impact) prod

uced by stamping the heel and transmitting the

impact from the leg directly into the instrument

(Dunkel 1993:26).

Figure 3. Position (b) - One leg support.

c) Standing position: previously used among folk

music bandoneonists, Piazzolla first introduced

this method to Tango music. The position

involves standing with one foot on the ground

Figure 4. Position (c) - Standing.

and the other on a stool with the thigh parallel

to the floor. This allows greater sound projection

and force of attack (Dunkel 1993:21-2).

dubbed as fuelle (bellows).5 As bandoneonist Rene

Marino Rivero affirms:

The first two positions can be combined by the

performer within the same piece. For example, if the

[The bellows] react to the player's slightest movement

bandoneonist is playing first legato and later stressed

and turn those movements into vibrations - in both

accents, he or she could switch from position a to b.

This is the standard practice among bandoneonists

the physical and spiritual sense. At the instant the

formed air stream is converted into sound, it leaves

the instrument in order to once more become air

playing Traditional Tango and was the technique

used by one of the most renowned Traditional

(Dunkel 1993:5).

Tango players, Anibal Troilo. Today bandoneonists

often play either standing or seated depending on

In addition, as bandoneon player Julian Hasse

the piece; they usually choose a seated position explained to me:

for traditional Tango and an upright position for

contemporary Tango.

The bellows are so vital to the distinctive form of

Astor used to say that by playing in upright position

sound production and identity of the bandoneon that

bandoneon player is closer to the source of sound

among Tango players the instrument is sometimes

emission and it seems the instrument gets a different

the sound seems to come from the player's guts, the

5 An additional spelling of the word is also found in Lunfardo (portenos' slang): fueye.

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maurino ? Bandoneon 267

Figure 5. Bellows operation - (i) Restricted.

Figure 7. Bellows operation - (Hi) Protean.

it in a kind of communion with his instrument. As

he said in an interview: 'the bellows is my other half

(Speratti 1969:30).7

There are three distinct ways of operating the

bellows:

(i) Restricted: the opening and closing phases are

very short;

Figure 6. Bellows operation - (ii) Extended.

timbre, as if the harmonic range of the bandoneon was

expanded.6

This proximity with the instrument allowed

Piazzolla to breathe with his bellows; speak through

(ii) Extended: the bellows is fully opened;

(iii) Protean: the central bellows section rests and

the two manuals move freely.

In the first two methods, the air stream is

homogeneous and the third one, (protean) works

with air turbulences (Dunkel 1993:23). The protean

operation is performed in the one leg position

6 'Astor soh'a decir que al tocar parado el sonido parece salir de las tripas, el bandoneonista est? m?s cerca de la

fuente de emisi?n del sonido y parece que el instrumento tuviera un timbre diferente, como si se expandiera el rango

arm?nico del bandone?n.' (author's translation). Personal communication (July 2008).

7 'El fueye es mi otra mitad.' (author's translation).

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

268 The Galpin Society Journal LXII (2009)

(position b above) and in the standing position (c),

both of which use the force of gravity to cause the

manuals to fall. This produces a larger air column

and hence more power and sound projection which

is more distinctive and violent than in the upright

position. In addition, this position enables the

performer to emphasise the accents more vigorously

(sforzato).

A NEW BODY FOR A NEW TANGO

In his memoirs Piazzolla explained the embodi

ment of his New Tango in relation to traditional

bandoneon performance practices, identifying why

he chose to play standing with his left foot on the

ground and placing his right foot on a stool while

supporting the bandoneon on his right thigh:

I played seated for many years, like most of my

colleagues, until I became a soloist. Then I felt the urge

of searching for another position that corresponds

more with my personality. When seated, I had the

sensation of being tied. So I stood up, I secured my left

leg on the ground and put my instrument on my right

leg (Gorin 1998:150).8

The study of the mechanics of the human movement

helps to show how Piazzolla shaped a New Tango

body for the bandoneon player, a completely different

ergonomics: a new body for a new music. The centre

of gravity of an object (including the human body)

is the point at which the whole weight of the object

is considered to act. Its position depends on the

distribution of the weight of the object (Watkins

1983:65). While the bandoneon player is seated, the

centre of gravity is at the hips; by playing in upright

position, the centre of gravity rises to near the

level of the player's navel. In addition, standing on

one foot reduces the size of the support base. With

Piazzolla's position for bandoneon performance the

base of support is smaller (only the left foot) and

the centre of gravity is higher (upright position). It

is therefore more difficult for the body to remain

stable since greater control must be exerted over the

centre of gravity. In addition, standing on one foot

(asymmetrical stance) requires much greater control

of the muscles of the grounded leg, especially in the

ankle joint (Watkins 1983:72).

Considering this performance posture, a search

Figure 8. Bellows operation - Balanceo.

for more physical comfort should be ruled out as a

cause of this significant change. What, then, are the

reasons for this posture adjustment? A clue can be

found in Piazzolla's discourse: 'When seated, I had

the sensation of being tied' (Gorin 1998:150). In

traditional bandoneon performance, with a seated

position, the initiation (the body part(s) with which

the movement is started) (Moore & Yamamoto

1988:192) remains in the upper body (arms, head,

chest), whereas in the upright position the initiation

can be located either in the upper or lower bodies.

The movement initiation can be located in the legs,

chest, pelvis, head or arms; opening a range of new

'choreographicar possibilities as is evident from

watching a Piazzolla performance. In performance,

Piazzolla's body seems to be in an unstable

equilibrium, he constantly redistributes his weight

in order to maintain stability. His body language is

therefore further in tune with his music: the New

8 'Durante muchos anos toque sentado, como la gran mayoria de mis colegas, hasta que me convert! en solista.

Ahl senti la necesidad de buscar otra posici?n que se adecuara m?s a mi personalidad. Sentado me daba la sensaci?n

de estar atado. Me pare, clave la pierna izquierda en el piso y acomode el instrumento sobre la derecha/ (author's

translation).

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maurino ? Bandoneon

1 vl?

13 V

teg

17 V [

V Close bellows using valve I I Opening phase

Example 2. Piazzolla, Astor (1969) Otoho porteno (bandoneon part). Buenos Aires: Editorial Lagos, bars 13-16.

Tango rhythm is constantly engaged in a kind of

Marconi, eventually incorporated this technique

unstable rhythmic equilibrium. In Traditional

when playing seated.9

Tango, where rhythmic variety is not as pervasive

as in New Tango, the patterns of movement when

seated are compatible with a music tailor-made for

dancing whereas in Piazzolla's music the upright

position, freeing the initiation of movement to more

body parts, adjusts perfectly to the new musical

concept. This is evident from the way that Piazzolla

used to play seated at the beginning of his career.

At that time he was still performing Traditional

Tango as bandoneon performer in Troilo's orchestra

and in his own first orchestras (1940s and 1950s)

during the period of the Traditional Tango. He only

changed his posture in the 1960s, when his music

started to change.

At this point, it is clear that Piazzolla's position

increases the technical difficulty of bandoneon

performance, as it is more comfortable to play

supporting the instrument on the lap while seated. In

addition, the weight of the bandoneon is distributed

unevenly to the extremes such that it needs extra

strength to keep it straight while playing in upright

position (Gorin 1998:237). There are two techniques

that try to solve these difficulties. When using the

protean position (see Figure 7) and playing with

one hand, Piazzolla placed the manual (keyboard

box) corresponding to the hand he was playing

on his thigh and open the bellows from the hand

he was not playing on. This was quite frequent in

Piazzolla's technique, but does not rule out the fact

that he could play with both hands while in protean

position. Other bandoneonists, such as Nestor

Additionally, the technique called balanceo

(balancing) was incorporated to facilitate the closing

of the bellows. It consists in changing the orientation

of the manuals from vertical to inclined (keyboard

facing up) while balancing the centre of the bellows'

folds on the supporting knee in order to be able to

close the bellows more easily (see Figure 8).

From the 1960s until his last performance in 1990,

Piazzolla used the upright position with protean

operation of the bellows in both his chamber groups

(such as the quintet) and with big orchestras; this

is the obvious way to operate the bellows because

when standing, only one leg is available to support

the instrument. The upright position emphasised the

idea of a bandoneon soloist in a context of chamber

Tango music (compared to the seated position of

the usually four bandoneons in a Traditional Tango

dance orchestra) and the fact that Piazzolla seemed

to enjoy?in his role of musical director ?a better

view of his musicians while playing.

In his memoirs, Piazzolla described the way he

liked to perform on the bandoneon: 'My fingers are

a machine gun ... I play with violence; my bandoneon

has to sing and shout' (Gorin 1998:152).10 In addition,

in this position it is easier to play when opening rather

than closing the bellows. Piazzolla very rarely played

closing: his performance of the musical phrases had

a limited extension (as much as he could or wanted

to expand the bellows).11 Most of the time he did not

expand the bellows to its limit of approximately 65

cm. and used the bellows' valve (the mechanism that

9 Julian Hasse, personal communication (November 2008).

10 'Yo toco con violencia, mi bandoneon tiene que cantar y gritar' (author's translation).

11 Some bandoneonists play only opening the bellows because they are limited technically and are not knowledgeable

of the fingering technique for closing. This was not the case of Piazzolla who was proficient in playing when both

opening and closing the bellows.

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

269

270 The Galpin Society Journal LXII (2009)

allows the bellows to close without sound emission)

the melancholic legato sound or steady rhythmic

to shut it for the next phrase. Even though he beats that were suitable for the social dancing of

occasionally used the balanceo technique in order the Traditional Tango. His innovations were more

to expand the phrases, in general he composed and consonant with the hectic pace of life in 1960s

interpreted the bandoneon parts to allow the use of Buenos Aires, a city that grew and transformed

the bellows' valve as a wind performer would allow radically during that decade.

time for breathing (and to force the comparison

even more, the circular breathing technique used to CONCLUSION

extend the phrases in some wind instruments could This article has described how Piazzolla's changes

equal the bandoneon's balanceo technique). But, to the performance technique affected the sound

unlike most wind instruments, where the sound output of the bandoneon and his compositional

emission is produced by blowing, the opening phase methods for the instrument. Were these a mere

of the bandoneon uses the suction of air, what can be

consequence of his decision of playing standing or

called suction phrasing. Example 2, Otono porteno

were they an aesthetic choice? Piazzolla explained

that playing standing gave him more freedom,

but other explanations are possible, such as more

emphasis on his role as a soloist, to highlight his

position as musical director or even for egotistic

reasons. Such reasons must remain speculative,

(1969), shows how Piazzolla's bandoneon phrases

were composed and played. In the audiovisual

recording of a performance (Lacombe 1984), it can

be seen that Piazzolla closed the bellows at every

quaver rest.

but it is evident from this study that the standing

SOUND COLOUR

position introduced new performance techniques

While playing with the instrument by opening, while restricting some others or making them more

the sound is brighter than when closing. The effort difficult. It created a new body of performance more

that Piazzolla chosen technique imposes on his

consonant with the unstable equilibrium of New

performance is also recognised as a source of musical Tango, liberating the music from the rigidity of

expression, it is Piazzolla's sound trademark and can the predictable rhythms that suited social dancing.

be summarised as follows:

Additionally, the standing position brought new

sonorities to the Tango soundscape that portrayed

more accurately the transforming city of Buenos

Aires and widened the choices for the bandoneonists

high sound projection

force of attack

who can now choose between standing or seated

bright sound

positions, depending on their repertoire or their

performing preferences. For these reasons, the new

suction phrasing

The sound characteristics that Piazzolla introduced

in his New Tango established a departure from

style of performance pioneered by Piazzolla has

been adopted by a significant proportion of the next

generation of bandoneon players.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archetti, E. (1999). Masculinities: Football, polo, and the Tango in Argentina. Oxford: Berg.

Asian, P. (1990). Tango: Stylistic evolution and innovation. Unpublished Master of Fine Arts In Music Thesis,

[Los Angeles]: University of California.

Azzi, M. S. (2002). 'The Tango, Astor Piazzolla, and Peronism (1940s-1955)'. In W. Clark (Ed.), From tejano

to Tango: Latin American popular music (pp. 25-40). London: Routledge.

Bartenieff, I. & Lewis, D. (1983). Body movement: coping with the environment. New York: Gordon and

Breach Science Publishers.

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maurino ? Bandoneon 271

Baily, J. (1977). 'Movement patterns in playing the herati dutar'. In J. Blacking (Ed.), The Anthropology of the

body (pp. 275-330). London: Academic Press.

Cannata, D. (2005). 'Making it there: Piazzolla's New York concerts', Latin American Music Review, 26(1)

57-87.

Clarke, E. & Davidson, J. (1998). 'The Body in Performance'. In W. Thomas (Ed.), Composition, performance,

reception. Studies in the Creative Process in Music (pp. 74-92). Aldershot: Ashgate Press.

Collier, S. & Azzi, M. S. (2000). Le Grand Tango: the life and music of Astor Piazzolla. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Dunkel, M. (1993). Bandoneon Pure. Dances of Uruguay. [CD Booklet] Washington, DC: Smithsonian

Folkways Recordings.

Dunkel, M. (1987). Bandonion und Konzertina. Ein Beitrag zur Darstellung des Instrumententyps. Munich:

Emil Katzbichler.

Frith, S. (1987). 'Towards an aesthetic of popular music'. In R. Leppert & S. McClary (Eds.), Music and

society: the politics of composition, performance and reception (pp. 133-49). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Frith, S. (1996). Performing rites: on the value of popular music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gorin, N. (1998). A manera de memorias. Buenos Aires: Ed. Perfil.

Kuri, C. (1997). Piazzolla, la m?sica Umite. Buenos Aires: Ed. Corregidor.

Kutnovsky, M. (2002). 'Instrumental rubato and phrase structure in Astor Piazzolla's music', Latin American

Music Review, 23(1), 106-113.

Lacombe, P. (Director). (1984). Astor Piazzolla. Live at the 1984 Montreal International Jazz Festival [DVD].

Spectel Video.

Leppert, R. (1993). The sight of sound: Music, representation and the history of the body. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

MacRae, D. (1975). 'The Body and Social Metaphor'. In J. Benthall and T. Polhemus (Eds.), The Body as a

Medium of Expression (pp. 55-73). London: Allen Lane.

Mensing, C. (2004). The Bandoneon Page: Introduction. The Bandoneon Page Web site: http://laue.ethz.ch/

cm/band/nodel.html

Moore, C. & Yamamoto, K. (1988). Beyond words: movement observation and analysis. New York: Gordon

and Breach.

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: the Meanings of Performing and Listening. Hanover: University Press of New

England.

Speratti, A. (1969). Con Piazzolla. Buenos Aires: Editorial Galerna.

Taylor, J. M. (1976). 'Tango: Theme of class and nation'. Ethnomusicology, 20(2), 273-291.

Watkins, J. (1983). An introduction to mechanics of human movement. Boston: MTP Press.

This content downloaded from

146.50.98.29 on Fri, 23 Sep 2022 12:37:07 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms