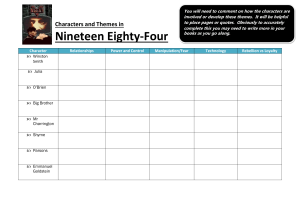

"Ingsoc in Relation to Chess": Reversible Opposites in Orwell's 1984 Author(s): Graham Good Source: NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction , Autumn, 1984, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Autumn, 1984), pp. 50-63 Published by: Duke University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1346017 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1346017?seq=1&cid=pdfreference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Duke University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "Ingsoc in Relation to Chess": Reversible Opposites in Orwell's 1984. GRAHAM GOOD The usual interpretation of 1984 is that it shows us a bold but doomed r of human values in the face of an inhuman tyranny. Among these valu sexual love, privacy, and memory of the personal and collective past: all are associated with the love affair between Winston and Julia. Althoug disturbing features in the book are often noted, such as Winston's rev for O'Brien even after the revelation that he is working for the Though and such as the "inhuman" oath Winston and Julia are willing to tak the supposed rebel conspiracy called the Brotherhood, the basic interpr remains in place, qualified by a certain uneasiness. My contention is that this basic or "manifest" reading is contradicted opposite but "latent" reading. The reversibility of opposites is a cardinal of Ingsoc, the reigning ideology of Oceania, and is announced by slo "War is Peace" and "Freedom is Slavery" (curiously, the third slogan, "I is Strength," is not exactly an opposition). My argument will be that this is not confined to Ingsoc, but applies to 1984 as a whole. The novel is s around a set of oppositions, like the Party vs. the Brotherhood, w symmetrical and interchangeable. Emotional and political allegiance switched instantaneously: from the start of the novel, Winston's loath Big Brother can change suddenly into adoration1 and he feels that it d matter whether O'Brien is a friend or enemy (p. 24). This principle in is shown in the reversible interpretations of the roles of the main cha Winston takes Julia to be a spy at first, then accepts her as a fellow reb O'Brien, he assumes unorthodoxy first and later has to reverse the assu and the same principle applies to Winston's own behavior. Thematic principle is shown in two related motifs: the game of chess, and the p black and white imagery which persists throughout. The interchangeab black and white, as sides in the game, as colors in the pattern and as sy of any pair of opposites, lies at the heart of Orwell's own thinking, no of the ideology of Ingsoc. I "Ingsoc in relation to chess" is the title of a lecture that Winston has to sit through at his Community Centre on the day when Julia passes him her "I love you" note; the lecture is frustrating for him, since he wants to be alone to think about this dramatic event. The title, of course, is a wry joke at the expense of an ideology like Marxism which claims to be universally applicable, but although Winston "writhed with boredom," the topic may have been better than many, 1 1984, (London: Penguin, 1973), p. 15. This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms GRAHAM GOOD INGSOC/CHESS 51 since chess does turn out to be one of Winston's interests. At any rate, the must have had some effect on him, because when he is finally alone, he from chess a metaphor to describe the situation he faces. He is preo with the urgency of his desire for Julia. "A kind of fever seized him thought that he might lose her, the white youthful body might slip away him... But the physical difficulty of meeting was enormous. It was like to make a move at chess when you were already mated" (90). In this image, sex and chess are closely interlinked, and we are remind the tradition of lovers as chess players which appears, for example, at the The Tempest when Ferdinand and Miranda are "discovered" at chess. But the image only makes sense if Julia is more a piece to be taken (as so of language of sport, like the word itself, is also sexual) rather than the op player, which is presumably the Thought Police or the Party. Her white is a pawn, perhaps offered as a sacrifice leading to a trap. Winston is tem into playing, but he is already "mated." Given the associations already cr this could be a sublimated pun: "mate" means simultaneously winning Ju losing the game. The actual phrase is passive ("already mated") and this c sponds well to Winston's sexual passivity (Julia initiates and essentially m the affair), as well as creating a strong association of desire and defeat. Ob even to think about the problem of responding to a checkmate, you believe that you are not mated while you try out the possible moves, and exactly what Winston does. He knows he is going to lose, in the sense th Thought Police will eventually capture and punish him, but he suspends, intellectually, the idea that he has already lost before he even starts. He i into a match right at the end when the outcome is a foregone conclusion moves are meaningless. At a deeper level, though, this image of being ma eventually, but already, stays with him and surfaces again in the last par book. Whether she is a pawn or a player, Julia's whiteness is repeatedly stressed: her white face, set off by dark hair and lips, is practically a leitmotif, and when she flings aside her overalls, "her body gleamed white in the sun" (103). This mythical gesture of self-exposure haunts Winston's imagination: to him it seems to symbolically annihilate the whole system of the Party's tyranny. Yet in the black and white pattern of the novel, white is very clearly the colour of the Party. After all, "White always mates" (232). Invariably, white means power, from the "glittering white concrete" (7) of the Ministry of Truth glimpsed at the beginning of the novel, to the "glittering white porcelain" (181) of the rooms in the Ministry of Love, "the place where there is no darkness," and where "men in white coats" supervise Winston's torture under the constant "white light." The final victory of Oceania is shown on the telescreens at the end of the novel as "the white arrow tearing across the tail of the black" (238). Thematically Julia is a creature of whiteness, light and exposure; her sexual power is associated with the political power of the Party, even though superficially the two seem opposed. Winston is equally strongly associated with darkness and blackness. As a This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 52 NOVELIFALL 1984 dissident, his survival depends on hiding: hiding his thoughts, his fac Symbolically, he is associated with private spaces such as the a apartment, or the room over the shop. Both these spaces are also dark and Winston's body reflects these qualities. Just as he fears being se police for political reasons, he fears being seen by Julia for sexual r the "Golden Country" meeting, "the May sunshine had made him and etiolated, a creature of indoors, with the sooty dust of London of his skin. It occurred to him that till now she had probably never in broad daylight in the open" (98). As the affair progresses, Winsto overcomes his physical shame and eventually gets used to being nak presence. Significantly, he is naked at the time of the arrest: sexual e become political. What follows now, still associated with white, is pu Finally Winston fantasizes "walking down the white-tiled corridor," shot, "but with everything forgiven, his soul as white as snow" (239 purity and death become one, all ways beyond the darkness of se the way to love of power. Winston moves through love of Julia, thro O'Brien, to love of Big Brother, like a novice moving from love of lo of higher things. Julia leads Winston from the darkness into the light, from hidin open, from filth to cleanliness. The room over the shop is usually t antithesis of Room 101, but actually it is an antechamber which pre Room 101: Winston's bed of love with Julia prepares for his bed of O'Brien. Whether deliberately or not, Julia's intervention in Wi objectively hastens his discovery, punishment and atonement. Julia on," through the experience of sex, towards reconciliation with the in religious terms, through sin to salvation. Winston himself at desires exposure and confession, despite his fear and his passive initiate. His desire for privacy with Julia is a counter-theme, but ult weaker. At times the lovers talk longingly of their need to be alone The room is meant as a hiding place i deux, and comes to symbol world of bourgeois domesticity.2 Winston even wishes once that have to make love each time they met, and could enjoy a marital sexual intimacy (114). But at a deeper level Winston wants to "go pu Julia. Does he, at that level, somehow "know" the police are listening lovemaking in the room? What attracts him to Julia is not her poten ness," but her "whorishness." Their first attempt at sex is a fail Winston only becomes aroused the second time by the assurance tha slept with Party members "scores of times." This actually gladdens as exciting him: he doesn't want a "private," exclusive, domestic rela much as a flagrantly "public" one. Impersonal sex is more potent polit personal love: "Not merely the love of one person but the animal ins simple undifferentiated desire: that was the force that would tear t pieces" (103). It is the "public" nature of Julia's body-the other 2 See David Kubal, "Freud, Orwell and the Bourgeois Interior," Yale Review, 67 (1978), 389-403 This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms GRAHAM GOOD IINGSOC/CHESS 53 glorious gesture with which she flings her overalls aside-which enthralls him. She is transformed from virgin into whore (and back again at the end of the book, where she is sexually frigid), but never approaches the wife which Winston's ideas about private domesticity ought to lead him to want. The Party has suppressed both marital and extra-marital sex, but it is the second kind Winston longs for: open, flagrant, promiscuous. It could be argued, in fact, that Julia's complicity with the Party is not merely symbolic.3 There is some evidence for Winston's original hypothesis about why she is following him: she is working for the Thought Police, or more appropriately, for the Ministry of Love. Winston dismisses too easily "the possibility that she might be laying some kind of trap for him" (83), which is one of his first reactions. She seems suspiciously familiar with his life story: "He began telling her the story of his married life, but curiously enough she appeared to know the essential parts of it already" (108). Like Charrington, she agrees "with unexpected readiness" (114) to the reckless idea of renting the room. Like O'Brien, she shows an immediate intimacy with Winston's secret thoughts and feelings, and, given the way she is associated with O'Brien in Winston's mind, it makes one suspect they are working together. She leads Winston directly to the exact landscape of his Golden Country dream, which can hardly be a coincidence-either Winston's dream is pre-cognitive or Julia knows that the image has somehow been implanted in him. The "scores" of Outer Party members she claims to have seduced may have been dissidents like Winston. It is hard to believe that she was so overwhelmed by desire for him that she followed him for miles into the distant quarter where the shop is, and having done so, did not communicate with him. Why, then, is she punished when the arrest comes? We see her punched in the stomach when the police enter the bedroom (though that could be to leave Winston his illusion about her), and at the end of the book she shows obvious signs of torture and brainwashing which support her account of them. Perhaps she became too involved with Winston and actually came to have divided loyalties. Perhaps the Party came to feel that she was deriving too much enjoyment from seducing dissidents, or had simply become, in that menacing Orwellian word, "unreliable." Julia's role, then, and even her body-image, are radically ambivalent. She is sexless or oversexed: the chastity girdle she wears, the scarlet sash of the Junior Anti-Sex League, actually increases her appeal to Winston by emphasizing her hips (12). Winston's affair with her is framed by his first impression of her as "young and pretty and sexless" (16) and his last impression of her "thickened, stiffened body" (235) which makes no response to his touch. During the affair she is seen as boyish or womanly: when she puts on makeup and scent, Winston finds her "far more feminine. Her short hair and boyish overalls merely added to the effect" (117). Here the 1940's show through the novel's 1980's in Julia's desire to stop being a wartime woman in "masculine" overalls and go for a "feminine" New Look: "I'm going to get hold of a real woman's S This suggestion is also made by Patrick Parrinder in "Updating Orwell?" Encounter, 56, (January 1981), 48. This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 54 NOVEL IFALL 1984 frock from somewhere and wear it instead of these bloody tr silk stockings and high-heeled shoes: In this room I'm goin not a Party comrade" (117). She is unorthodox or orthodox: sh propaganda, with the accent of a boarding school prefect b "bloody rubbish" or "bloody rot," and yet "she only questioned of the Party when they in some way touched upon her own lif joke that she is only a rebel from the waist down may be truer and her finding it "brilliantly witty" may concede this. She is Virgin, Rebel/Spy. She is the agent of Winston's sexual libe wittingly or unwittingly, of his exposure as a criminal. Winston have kept his thoughtcrime hidden for a while longer: it is the that brings about his discovery. II The same question now has to be raised about Winston's role as about Julia's: how deep, how genuine, how consistent is his rebellion against the Party? His conscious attitude towards the Party is usually defiant, and he has certain concrete acts of defiance to be proud of. Yet for the most part these have come about in response to promptings and suggestions that seem, often in mysterious ways, to come from outside himself. And there are hints, in his emotions mostly, that his rash defiance is simply a way to hasten the punishment and forgiveness he subconsciously desires. This "spatial" contradiction between surface (desire to rebel) and depth (desire for atonement) in Winston's psychology, corresponds to a temporal one in terms of the novel's plot between the prospect (as you read) of Winston's rebellion and the retrospect (as you look back later) not of its defeat merely, but of its invalidation. The "depth" reading underlies and reverses the "surface" one, but this reversal is only possible retroactively, and is not usually fully carried out: for most readers the "surface" interpretation continues to hide much of the depth. We should look at the turning point of the novel, where it begins potentially to reverse its "sense": the moment when Julia and Winston are surprised in the room above the shop, and the voice from the telescreen with grim playfulness completes the "Oranges and Lemons" rhyme with "Here comes the chopper to chop off your head." Up to the point of the arrest, Winston has grounds for a limited optimism about the opposition culture in Airstrip One. He believes in the existence of a widespread though decentralized conspiracy against the authorities, which has a leader (Goldstein), a sacred text (the leader's book), and a membership of which he has met a highly placed representative (O'Brien). He believes that this conspiracy will eventually be able to mobilize the proletariat and overthrow the Party. The sense of optimism does not extend to his own fate, however. He knows he is doomed to be caught, punished and killed. Even so, he has already to some extent validated his life and thereby authenticated the oppositional culture through certain personal experiences forbidden by the party. He has had This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms GRAHAM GOOD INGSOC/CHESS 55 a passionately sexual affair. He has eaten real food, and drunk real coffee and wine, instead of ersatz products for usual mass consumption. Thanks to M Charrington, the old shopkeeper, he has owned a real object (the glass pape weight), and written on real paper with a real pen. Even if only for sho periods, he has had a room of his own, in which to read, make love, and meals. Despite taking enormous risks, he has successfully evaded police detecti for several months. All of this is behind at the moment of arrest: memorable, undeniable experiences which defy Party ideology. Whatever happens after th arrest, this experience seems safely accomplished: it has happened, and this in itself constitutes a kind of victory. Then follows a series of shocks. The room, a symbol of a long-forgotte personal privacy, turns out to have been kept under telescreen observation all along. Everything Winston and Julia have said and done there has probably be heard and recorded. Mr. Charrington, the kindly old shopkeeper-a brillia feat of impersonation-is simply a 35-year-old member of the Thought Police. The whole episode of the shop, though Winston himself never fully reinterpre it in this light, must have been an elaborate trap, set especially for him, whic he first entered when he bought his diary there. Soon after, the conspiracy t turns out to be a sham: O'Brien is on the other side. Later, it is revealed that even Winston's diary has been read without his knowledge: the police carefull replaced the speck of dust which he put on the corner of the cover. Like all t other precautions taken by Winston and Julia, it was completely ineffectu their movements were followed the whole time. These surprises all have the same effect: to reveal to the reader and the hero that the Party has in fact immeasurably greater powers of control and surveillance than had previously been supposed. The putative freedom of Winston's experiences is retrospectively invalidated. The events are not what they seemed when they were taking place: they were all permitted, even supervised, by the police. Winston has actually been under police surveillance since 1977. 1984 is the culminating year in a seven year period; the figure is mentioned several times. "He knew now that for seven years the Thought Police had watched him like a beetle under a magnifying glass. There was no physical act, no word spoken aloud, that they had not noticed, no train of thought they had not been able to infer" (222). It is not clear whether or not Winston had attracted police attention prior to 1977, but he had certainly committed thoughtcrime before the beginning of the seven year programme: 1973, the year of his marriage and of his temptation to murder his wife, was also the year in which he briefly held in his hand the photograph of Jones, Aaronson and Rutherford: documentary evidence of the falsity of Party propaganda. Whether this was an accident or a police plant, the incident is a mere prelude to the full-scale programme which begins in 1977. Surveillance is only the outer part of the program. At its heart is thought control, exercised not at the rational, but at the imaginative and emotional level. The process begins with the insertion of a particular phrase into a dream. Winston muses in his first diary entry in 1984: This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 56 NOVELIFALL 1984 Years ago-how long was it? Seven years it must be-he had dr was walking through a pitch-dark room. And someone sitting t him had said as he passed: "We shall meet in the place wher darkness." (23) Later, when Winston tries to interpret the saying, he assumes it anticipates the time after the eventual overthrow of the Party (86). During the visit to O'Brien's flat, he quotes the phrase in this sense, and his host seems to understand and recognise the allusion (145). After his arrest, Winston realizes that the place referred to is the Ministry of Love, where there are no windows and the lights never go out (184). Finally the original voice speaks to him again: "Don't worry, Winston; you are in my keeping. For seven years I have watched over you. Now the turning point has come. I shall save you, I shall make you perfect." He was not sure whether it was O'Brien's voice; but it was the same voice that had said to him, "We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness," in that other dream, seven years ago. (196) This leitmotif moves through successive interpretations and successive states (dream and waking, obscurity and clarity of reference), and finally produces a sense of inevitability, even rightness. The phrase, with its religious and prophetic associations, gives Winston a feeling of not being alone, of being guided by some higher agency. His only surprise is that the voice of salvation comes from the Party and not the Brotherhood, but even this is soon replaced by a deeper sense of fulfilled expectation. Winston assents when O'Brien says to him, at the point when O'Brien's appearance in the Ministry of Love reveals him as a Party agent, "You knew this, Winston. Don't deceive yourself. You have always known it" (192). What is striking here is the backdating of the awareness. Winston has no new realizations, only clarifications of what he has dimly sensed all along. Underlying Winston's fear and suspense is a deeper sense of resignation, a sense of being embarked on a closed sequence of events, not one of which can be omitted or abbreviated. His rebellion, far from giving him a sense of freedom as one might expect, actually produces a heightened sense of destiny, of moving through a set series of experiences towards an appointed end. In the middle of the book, after receiving O'Brien's summons, Winston muses: What was happening was only the working out of a process that had started years ago. The first step had been a secret, involuntary thought, the second had been the opening of the diary. He had moved from thoughts to words, and now from words to actions. The last step was something that would happen in the Ministry of Love. He had accepted it. The end was contained in the beginning. (130) This passage is one of a series distributed throughout the book which emphasize This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms GRAHAM GOOD INGSOC/CHESS 57 Winston's foreknowledge of his punishment and death. During his first entry: He was already dead, he reflected. It seemed to him that it was only now, when he had begun to be able to formulate his thoughts, that he had taken the decisive step. The consequences of every act are included in the act itself. He wrote: Thoughtcrime does not entail death: thoughtcrime IS death. (26) At the end of the book also, O'Brien repeatedly reminds him of this idea. For instance when he has shown Winston the appalling condition of his body, O'Brien tells him, "It was all contained in that first act. Nothing has happened that you did not foresee" (219). At issue here is far more than the mere logistical certainty of being caught and executed in the end. The entire sequence of events is pre-experienced, so that on the emotional-intuitive level, the whole is virtually present at the beginning and at every subsequent stage. It has been painstakingly prepared for Winston, and he for it. O'Brien, presumably the planner of the operation, acts as a kind of Prospero, staging a series of scenes for an actor who is only subconsciously aware of being controlled. The fact that Winston's room in Victory Mansions has an alcove out of view of the telescreen-this peculiarity first gives him the idea of writing a diary-may be part of the design. Charrington and his shop are explicitly so: the scenario was, one might say, customized for Winston, and there are clear suggestions of thought control in the way he is led there absentmindedly, particularly the second time: It had been a sufficiently rash act to buy the book there in the beginning, and he had sworn never to come near the place again. And yet the instant that he allowed his thoughts to wander, his feet had brought him back here of their own accord. (78) Even in the rebellious gesture that opens the novel, Winston's starting his diary, he is not acting freely at all, as he soon intuits: "He was writing the diary to O'Brien, for O'Brien" (68). O'Brien's fascination for Winston is, again from the beginning, independent of what side O'Brien is on; the uncertainty does not affect Winston's desire to confide. Winston had never been able to feel sure-even after this morning's flash of the eyes it was impossible to be sure-whether O'Brien was a friend or an enemy. Nor did it even seem to matter greatly. There was a link of understanding between them, more important than affection or partisanship. (24) At the end, during the torture sequence, the degree of mental interpenetration between the two is such that O'Brien seems to know, immediately and without words, what Winston is thinking, and can articulate it for him. This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 58 NOVEL IFALL 1984 There was no idea that he had ever had, or could have, that O'Brien had n long ago known, examined, and rejected. His mind contained Winston's m (205) Winston's intellectual processes seem to be as foreknown as his experie Orwell makes O'Brien literally a master-mind, reversing the usual expectat that the rebel is more intelligent than the ruler, and thereby again giving eviden that Winston's mind is under thought control. Winston cannot produce anyt new, original, or unexpected; his rebellion seems to happen within O'Br mind. This realization invalidates Winston's rebellion: not only its realistic feasib (never great) but also its symbolic significance. Winston's goal, we m remember, is "not to stay alive, but to stay human" (136). As he puts Julia, "If you can feel that staying human is worth while, even when it ca have any result whatever, you've beaten them." In other words the actual l of the life and death game can nevertheless win a moral victory. Winston offers a tragic-humanist interpretation of his objective, which is to die w dignity, thus asserting human worth in a moral victory amidst an actual d and death. The affirmation of a human individuality, which death cannot des and in fact enhances, ceases to be possible when that individuality can be c pletely destroyed. For Orwell, that point had been reached in his own period, whi he saw as a Counter-Renaissance, moving back from individualism into a "t order" like that of medieval Christendom, only infinitely more power Orwell's original title for 1984 was "The Last Man in Europe"; perhap reason for the change was that Winston could not fully live up to this rol the novel is post-tragic, then in a sense Winston is already post-human, at beginning of the book, not just at the end. The struggle is already over: m already dead. "Staying human" is a delusion which the Thought Police foste only to destroy. According to O'Brien there will be endless "last men provide material for the Party's endless triumphs: Goldstein and his heresies will live forever. Every day, at every moment, will be defeated, discredited, ridiculed, spat upon-and yet they will al survive. This drama that I have played out with you during seven years be played out over and over again, generation after generation, alway subtler forms. (215) In the Christian universe God allows evil to exist, foreknowing but not fo ordaining it: the Party seems to take the further step of foreordaining it as "Humanity" is an illness which the Party causes and cures, a stain it t and wipes away. For Winston is denied the smallest vestige of even a symbolic victory, h ever far he pursues his fantasy of the "tiniest possible flaw": if perfection stake (and it is a favourite word of O'Brien's), it must be complete, both spa and temporally. The Party, Winston believes, has near-total control of This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms GRAHAM GOOD IINGSOC/CHESS 59 but there are safe, closed, private areas still available: the alcove in his flat, the room above the shop, the small clearing in the woods in the Golden Country. But more important is the inner space of the self, deep inside the body. "Nothing was your own except the few cubic centimetres inside your skull" (25). That space remains private, like the "mute protest in one's bones" (62), or the inner feelings of the heart. They are safe from exposure or invasion, Winston believes: "They could lay bare in the utmost detail everything you had done or said or thought; but the inner heart, whose workings were mysterious even to yourself, remained impregnable" (136). That "impregnable" fortress is taken when Winston, facing the rat-torture in Room 101, screams "Do it to Julia!" Thus the tiniest possible space of resistance is eliminated. The temporal equivalent is "the last possible moment." Winston's extraordinary fantasy after his brain-washing, when only the rat-torture still awaits him, is that for a few seconds just before he is shot he can revive his hatred of the Party. Then the smallest space (the inner self) for the shortest time (as the bullet is on its way) will defy the Party, and will always defy them, since they cannot reclaim that instant of freedom. For Winston, totality with the tiniest possible flaw is no longer totality. He believes he will be shot from behind, in the back of the head (interestingly, the only thing he feels to be inevitable that doesn't happen). The bang of the bullet and the bang of his explosion of hatred would be almost simultaneous. But those seconds of hatred would always exist: "They would have blown a hole in their own perfection. To die hating them, that was freedom" (226). But we never see this "ten seconds hate" in the novel, and in any case, the whole idea seems to be derived from the Two Minutes Hate, which is already part of the system. Winston is defeated both actually and morally-even the smallest possible space and the shortest possible time are conquered by the Party. Its victory is total, in symbol as well as reality.4 III In a sense, we can say that this is a "black and white" novel. Usually the phrase is used as a criticism, implying that the heroes and villains are too sharply distinguished, and that the moral pattern omits the shades of grey in real life. This is apparently true of 1984, where at least the evil is "totally" evil, utterly without redeeming features. But it is precisely this extremism, this "black and white" clarity, that makes for the symmetry and equivalence of opposites, and hence their reversibility. The pattern stays the same; only the values or alle- giances need change, as Oceania's enemy changes from Eastasia to Eurasia in mid-sentence, leaving the rest of the discourse unaltered. It is a black and white novel in which Black and White are instantaneously interchangeable, like the drawing discussed by Wittgenstein which can be "read" as a duck or a rabbit, depending on the interpretation uppermost in the viewer's mind.5 But you Daphne Patai, "Gamesmanship and Androcentrism in Orwell's 1984," PMLA, 97 (1982), 856-870, also suggests that Winston's dreams may have been implanted and the shop set up especially for him. This, and her discussion of the chess theme, are directed to a critique of the book as an example of gamesmanship, This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 60 NOVEL IFALL 1984 cannot read it both ways simultaneously: the two interpretations are possible but mutually exclusive. Orwell's novel, as a whole and in its features, is like this. Julia is a Virgin/Whore, O'Brien is a Friend/Enemy Winston is a Rebel/Penitent in the same way as Wittgenstein's fig Duck/Rabbit. The reversibility of opposites is in fact a cardinal principle of Ingsoc, as Goldstein explains in "The Book": The key word here is blackwhite. Like so many Newspeak words, this word has two mutually contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts. Applied to a Party member it means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this. But it also means the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary. (169) Which are the two meanings? Actually the phrase "it means" occurs three times. The first two, although they are probably the two intended, with the third as an afterthought, are different applications of the word, one disapproving and the other approving-the meaning is essentially the same in either case. The major shift is from saying (or applying the concept, favorably or unfavorably) to believing. The first two are contradictory uses of a contradictory concept: contradiction is bad (if an enemy is doing it) but contradiction is good (if a party member is doing it). Blackwhite is goodbad, we might say (Orwell, of course, coined the phrase "good bad poetry"). But the last sentence is the hardest, moving from saying to believing that black is white, and then to knowing that black is white, and forgetting that one ever believed the contrary. What is the contrary of Black=White? Here it must be Black=Black. Winston fails to believe through most of the book that Black is White. Instead he clings stubbornly to truisms like 2+2=4. He refuses the equation of opposites that is the central feature of Party propaganda ("Freedom is Slavery") and asserts counterequations in which the terms are the same instead of opposite: "Truisms are true" (68). But Winston does finally achieve blackwhite by shifting his allegiance from Black, the losing side in his game of chess, to White, the inevitable victor. And significantly, the chess theme recurs, focussing the black and white imagery into a final powerful image. Near the end of the book we see Winston in the Chestnut an "essentially masculine ideology (of dominance, violence and aggression)" (p. 868) which Orwell fails to transcend. 5 See Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, tr. G.E.M. Anscombe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953), p. 194, and E.H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), p. 5. The interchangeability of opposites is a random operation in Wittgenstein's Duck/Rabbit example but in Oceania the Party would decide between the two interpretations and then keep changing arbitrarily from one to the other, with no reason and no warning. The populace would be expected to change its view accordingly. Opposites are interchangeable, but the Party says which is correct and when. Black is White and White is Black, but Black always loses and White always mates. The "undecidability" of interchangeable opposites opens the way to the arbitrariness of the deciding power. This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms GRAHAM GOOD INGSOC/CHESS 61 Tree Caf6, where he had earlier seen Rutherford, Jones and Aaronson sitting by chessboard "with the pieces set out, but no game started" (65). Winston seated at his regular corner table, where "the chessboard was always waitin for him": He examined the chess problem and set out the pieces. It was a tricky ending, involving a couple of knights.'White to play and mate in two moves.' Winston looked up at the portrait of Big Brother. White always mates, he thought, with a sort of cloudy mysticism. Always, without exception, it is so arranged. In no chess problem since the beginning of the world has black ever won. Did it not symbolize the eternal, unvarying triumph of Good over Evil? The huge face gazed back at him, full of calm power. White always mates. (232) Our final image of Winston's drama is less like a game of chess, even one he has lost, than it is like a chess "problem." The "problem" differs from the game in several respects. First, its outcome is known in advance: the inventor of the puzzle has thought out all of the possible counter-moves; this corresponds to Winston's sense of inevitability. Second, the invented "game" is only a few moves away from checkmate: this corresponds to Winston's sense of being "already mated" at the outset. Thirdly, there is only one "player," unless we count the inventor of the problem. The "player" has to imagine the moves of both sides, and this Winston now does. Black is his old, evil, defeated self, White the new, victorious and pure. Thus when White wins, it is for Winston "a victory over himself." But all of this takes place within the overriding design of the inventor of the problem, whose mind foreknows all the possible moves and in a sense "contains" the player's in the same way as O'Brien's mind "contains" Winston's. We might define "Ingsoc in relation to chess" as precisely the law that "White always mates." The chess scene offers a final analogy: the novel itself appears in prospect to be a chess game in which, despite the tremendous unfairness of the odds, either side can win, at least symbolically. But in retrospect it is a chess problem: the design of the novel contains the mind of the reader, as the Thought Police do Winston's, and as the problem's inventor does the solver's. This shift from "open game" to "closed problem" is accompanied by the realization that black and white are equivalent, opposite, and interchangeable within a higher design. The novel, which is usually taken as "black and white" (i.e. manifestly antitotalitarian) is at a deeper level "blackwhite" (i.e. reversible). Reversed, the novel comes out as a religious poem, the struggle of the obdurate sinner to surrender to Omnipotence and Purity. This reading is as valid as the opposite one, and the two belong to each other like all the opposites within the novel. Orwell's Black/White is like Wittgenstein's Duck/Rabbit: each reading excludes the other but easily shifts into it. The very last sentence ("He loved Big Brother") has two meanings: the "black" meaning is the bitterest sarcasm, the "white" meaning is the deepest acceptance. There are parallels to this in Orwell's earlier fiction, especially Keep the This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 62 NOVELJFALL 1984 Aspidistra Flying, his last novel before 1984. Critics have complain complete ambiguity of the end, when Gordon gives up his poor existence as a would-be poet and goes back to his old job at an agency. As in 1984 the agent of the hero's reabsorption is a woman the way back into the system. Gordon feels he has to support the begotten and this leads him back into the service of the Money-Go Capitalism in this novel what Big Brother is to Ingsoc in 1984). Thi Julia's double redemption of Winston, first from his sexual i second from his political dissidence, even though in her case the re two aspects is superficially contradictory. The ending of the earlie Gordon throwing away his poem and buying an aspidistra, the the lower-middle-class respectability, can be interpreted equally w shameful capitulation (2) a reassertion of healthy normality. The difference between my interpretation of 1984 and the usual tially a move from "Winston and Julia rebel against but are def Party" to "Winston's rebellion as well as his defeat are engineered b through Julia." Traditionally the novel has been taken as validat rageous struggle of two isolated individuals against the horrifyi totalitarianism. Their defeat is read as an affirmation of humanistic values, as well as a warning against the type of society that destroys them: Irving Howe for example calls Winston's and Julia's affair "an experiment in the rediscovery of the human." 6 This interpretation must depend on the authenticity of Winston's original rebellion, in order to contrast the autonomy of his thoughts and actions before his arrest with their unfreedom afterwards. But this does not take account of the retrospective invalidation of Winston's imagined autonomy, of the fact that the love affair, the room over the shop, and all of the key experiences, are an experiment carried out by the Thought Police. The usual "tragic" interpretation cannot allow for this, since it must posit Winston's freedom as a reality in order to give meaning to its suppression. It must therefore suspend the textual evidence that Winston is under thought control from the beginning, and also underplay the love aspect of Winston's ambivalent love-hate relationship to O'Brien, Big Brother and the Party. In this way totalitarianism becomes less than total: it leaves room for forces that could change the system. But in the novel the idea that "no opposition is viable" overlays the even more radical thesis that "no opposition is meaningful" or even "no opposition, even symbolic, is possible." This "total" hopelessness underlies and is partly concealed by the more limited pessimism of the tragic-humanist reading which sees values affirmed in their defeat. The theme of freedom is on the surface level of narration, and depends on suspense and surprise; the theme of control is at a deeper level, and depends on anticipation and fulfillment through leitmotiv. The hero and the reader experience an apparently open series of events which in retrospect turns out to have been closed from the beginning. Yet because of suspense, the dread of what is coming, this task of revaluation is not fully performed, and in a Politics and the Novel, (New York: Fawcett, 1967), p. 241. This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms GRAHAM GOOD IINGSOC/CHESS 63 this way the text protects itself by inviting a partial, superficial reading of itself. The novel strategically covers its weariness with individualism, its deep emotional desire to give up the futile struggle and reach atonement, merge with the totality: a union whose accompanying sense of relief is only enhanced by a preceding resistance. We might describe Winston's consciousness as the temporary vehicle of the necessary self-negation of the Party Mind. And the reader's consciousness in the novel plays a similar role: it entertains the delusion of humanity as free agency in order to overcome the novelistic problem of demonstrating a totalitarian society. To have a plot at all there must be some kind of conflict or dissent to generate events. But if there is a conflict, then the totalitarianism is less than total. Orwell's solution is to show something that appears (both to the participants and to the novel readers) to be a rebellion at the time it is happening, but later turns out to have been under control all along. Thus Winston's illusion is the reader's illusion, and perhaps even partly the author's: the illusion that the Party's domination is less than total combines uneasily with the fear that it is total. In the novel, we might say, totality shows itself by creating and then abolishing the illusion of its own imperfection. Yet for many readers, and possibly for Orwell too, much of the illusion is left, at least on the surface. It is too hard to accept that the apparent "tragic humanism" of Winston's revolt is nothing but a cruel game played by the Thought Police. Plainly, Orwell is "against" totalitarianism: his works have been a symbol of this opposition for the entire post-war generation, and to suggest any ambigu- ity in this stance sounds like a perversion of his meaning. Yet Orwell was clearly intrigued and attracted by the notion of "totality" depicted through a pseudo-opposition which turns out to be part of the system. The reversibility of opposites is a central theme in the novel, and a similar reversal may be needed to complete the interpretation of the novel as a whole, as a tendentious text whose depth and greatness is created by "going back on itself" at a basic level. This content downloaded from 203.166.222.57 on Wed, 23 Feb 2022 03:05:04 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms